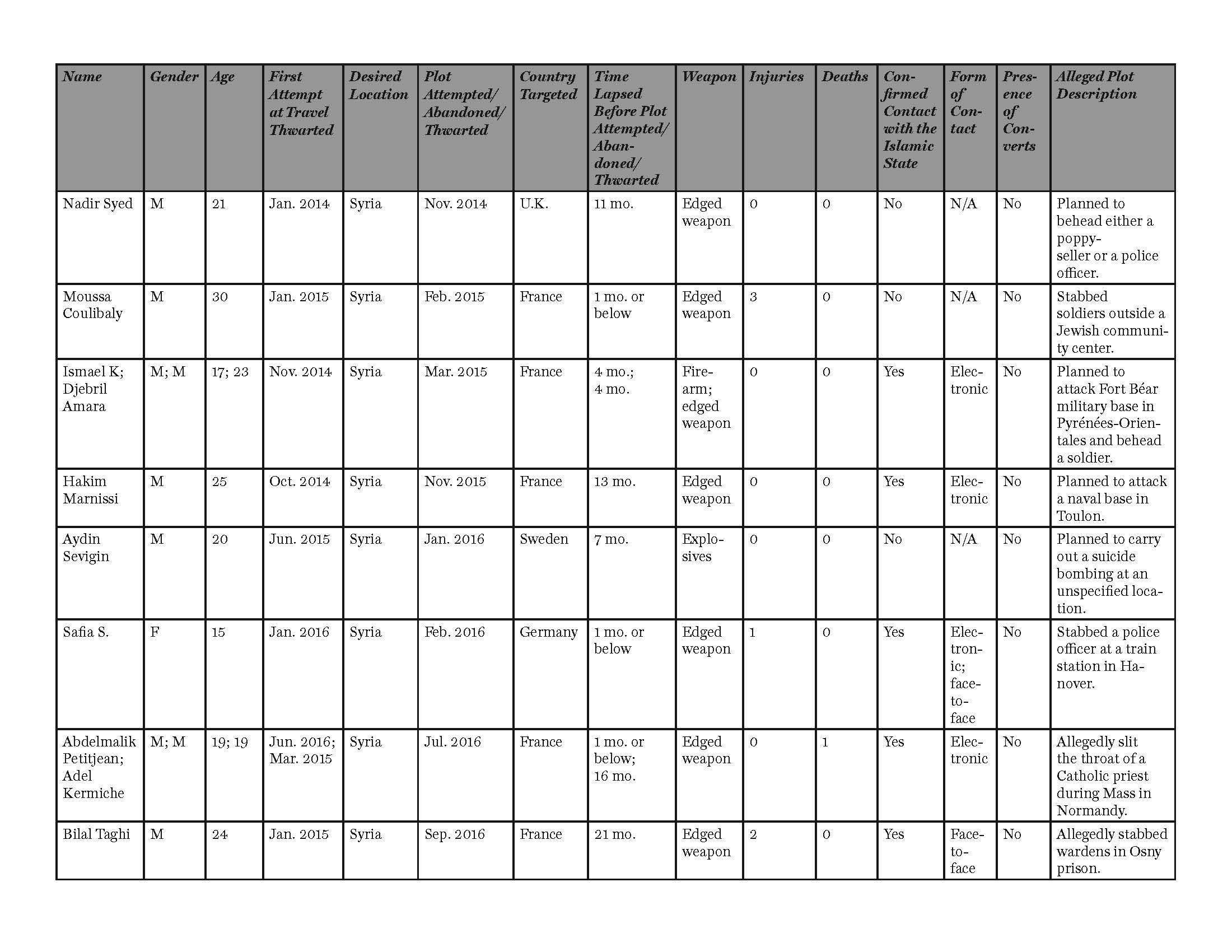

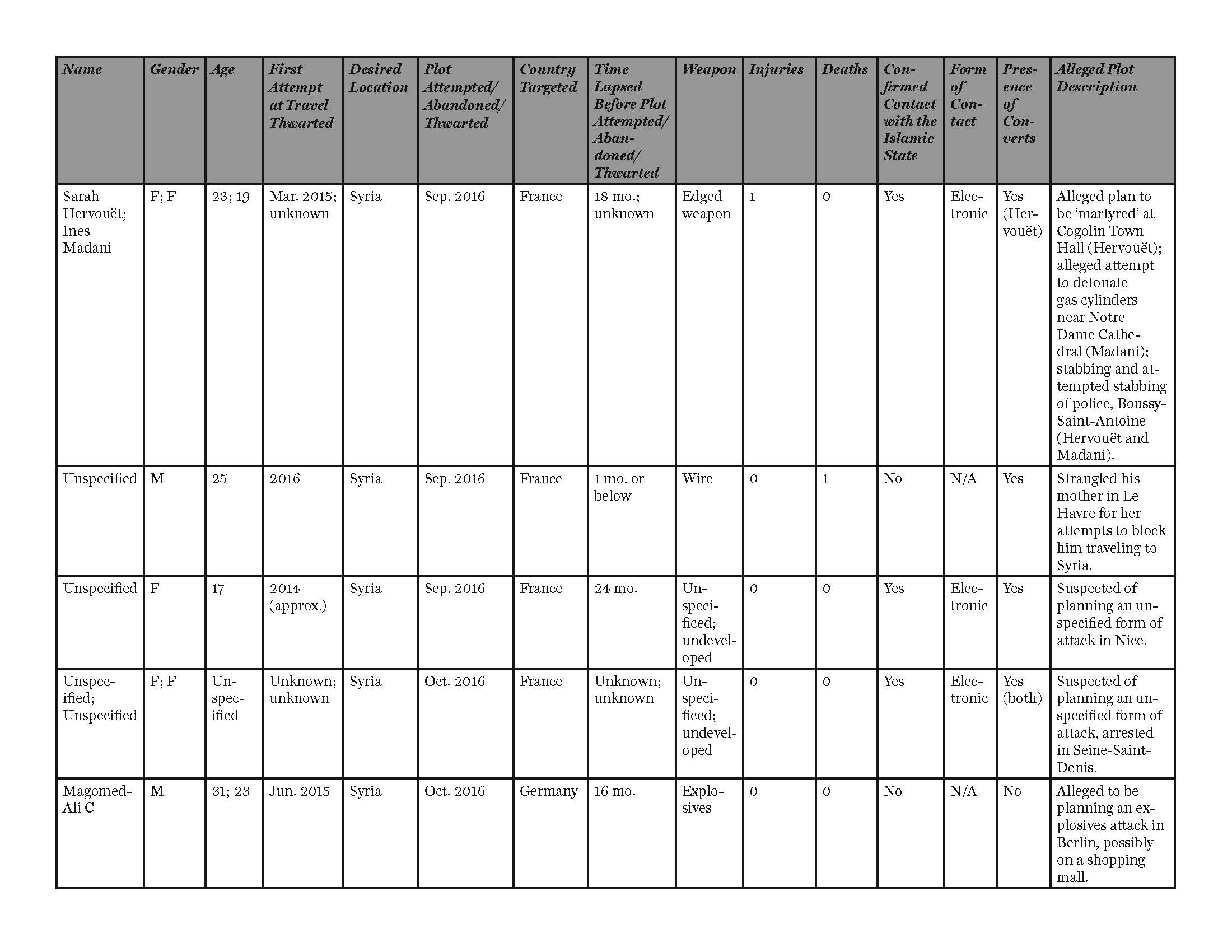

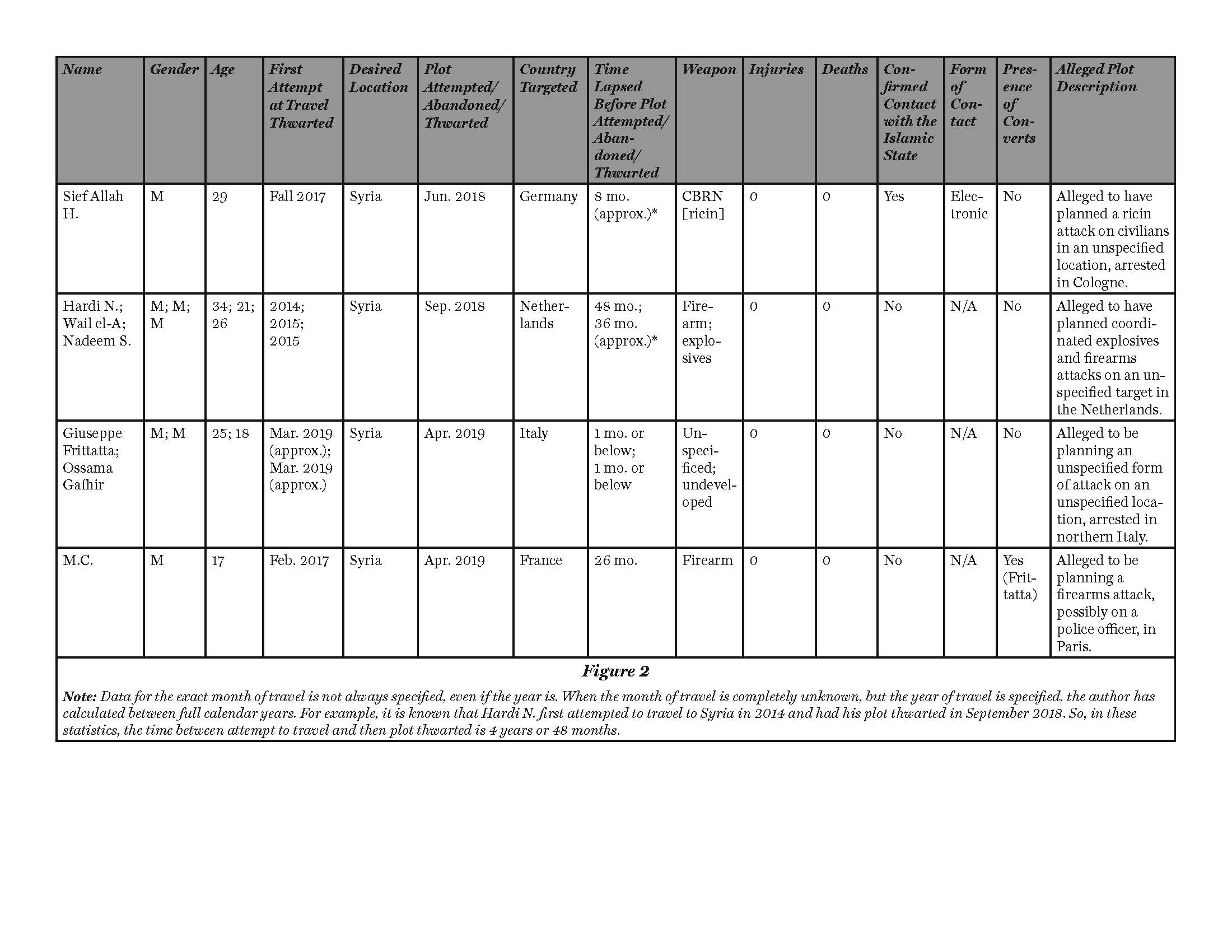

Abstract: For several years, ‘frustrated travelers’ unable to make it to Syria have responded with plots targeting the countries in which they reside. In Europe, most individuals attempted to travel between 2014 and 2016, when the Islamic State was at the peak of its power. Thwarted in these attempts, frustrated travelers sometimes launched rapid, unsophisticated attacks, rather than meticulously planned ones, in order to contribute to the Islamic State’s cause from their country of residence. In total, the 25 frustrated traveler plots that were set in motion in Europe between January 2014 and June 2019 resulted in eight attacks and led to 18 injuries and seven deaths. These plots involved a disproportionate number of females and minors, and more often than not, perpetrators were in contact with the Islamic State.

In September 2018, Dutch authorities thwarted an alleged major Islamic State-inspired plot that was being planned in the Netherlands. As part of their raids, police discovered 100 kilograms of fertilizer and several firearms.1 Three of the individuals arrested in this cell had allegedly previously made unsuccessful attempts to travel to Syria and, according to a United Nations Security Council report, this plot “demonstrated that ‘frustrated travelers’ remain a problem.”2

Six months later, two individuals who met online were arrested in Italy for allegedly planning attacks in the Islamic State’s name. Their plans to travel to the ‘caliphate’ were redundant, as there was no longer a viable caliphate for them to travel to; the last remaining towns controlled by the Islamic State in Syria had been liberated the previous month. So, instead, they allegedly sought to strike in Italy.3

One cell plotted because the caliphate no longer existed; the other because they were not able to reach it even when it did. This helps demonstrate why there has been a persistent risk posed by frustrated travelers. With this in mind, this article assesses whether the problem is on the rise or decline in Europe. It also studies which trends have emerged from previous frustrated traveler plots in Europe over the past five and a half years.

Criteria

The author’s dataset on plots includes successful attacks carried out by frustrated travelers (defined as a terrorist attack leading to injuries and/or deaths). It also includes failed plots carried out by frustrated travelers (defined as those that were thwarted by authorities, or abandoned by the perpetrators, and led to zero injuries and deaths).

To be included in this study, an individual needed to both live in Europe and to have physically made an attempt to leave his/her country of residence in Europe in order to connect with terrorists overseas; been legally barred from doing so; or been reported to the authorities for intending to do so. Expressing a vague willingness to travel was deemed not suitable for inclusion.

Included in the dataset was one Islamism-inspired act of violence, rather than what might traditionally be regarded as terrorism: in September 2016, a 25-year-old convert to Islam strangled his own mother to death in France after she prevented him from leaving for Syria.4

Also of note, in the late summer/early fall of September 2016, Sarah Hervouét and Ines Madani were allegedly involved in a series of separate plots targeting France. Both have been charged with terrorism offenses in France related to this plotting,5 with Madani having already been found guilty of using the encrypted messaging app Telegram to encourage others to carry out attacks in France and to travel to Syria.6 Madani and Hervouét allegedly plotted once alongside each other and sometimes with others who did not try to travel to Syria. However, in this study, their plots from this timeframe are categorized as a single unit.7

Destination: Syria

Based on these criteria, between January 2014 and through June 30, 2019, there were 25 plots involving frustrated travelers attempting to depart from Europe.* Eight of the plots resulted in attacks and 17 of the plots failed. The 25 plots pertained to 32 separate individuals. Thirty-one of these 32 (97 percent) intended to travel to Syria.

The only exception was Lewis Ludlow, a British citizen who was jailed for life (having to serve a minimum of 15 years) for planning a vehicular attack against civilians on Oxford Street in central London. Ludlow had tried to fly to the Philippines two months before his eventual arrest, yet had been prevented from doing so at the airport and had his passport confiscated.8 Ludlow was attempting to travel to the city of Zamboanga on the Zamboanga Peninsula, a distance 160 kilometers to the west of Marawi, the city controlled by the Islamic State for a period of five months in 2017.9

Four months after Philippine forces regained control of Marawi, Ludlow made his attempt to travel to that country. British authorities suspected Ludlow was going to Zamboanga to participate in acts of terrorism.10 In April 2019, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte warned against travel to Zamboanga as it was a stronghold for Abu Sayyaf,11 a Philippines-based jihadi group closely tied to the Islamic State.a

Of those who attempted to travel to Syria, only one was known to have attempted to do so before the Islamic State’s June 2014 declaration of a caliphate. Nadir Syed tried unsuccessfully to travel to Syria from the United Kingdom in January 2014, with his application for a passport being rejected. He instead planned to behead a poppy-seller or police officer, leading to his November 2014 arrest. Syed was subsequently jailed for life, having to serve a minimum of 15 years.12

Whether an Iraqi Kurd known as Hardi N. tried to journey to Syria before the announcement of a caliphate has not been publicly disclosed. He had attempted to travel to Syria from the Netherlands on an unspecified date in 2014 to join the al-Qa`ida affiliate there, Jabhat al-Nusra.b Hardi N. spent three months in jail in the Netherlands as a result, having been convicted for planning to travel abroad for terrorist purposes.13 In September 2018, he was arrested as the suspected ringleader of the aforementioned cell planning a major attack in the Netherlands. It is alleged two other individuals who had tried and failed to get to Syria in 2015 (i.e., after the declaration of the caliphate) were part of the same cell.14 At the time of writing (July 2019), no additional information has been publicly disclosed about the status of the case against them.

The timing of most of the attempts to travel means frustrated travelers would struggle to credibly claim they were trying to go to Syria for aid work or to join non-Islamist rebel groups. Almost all were traveling with the knowledge that a caliphate had been declared there.

Year of Travel and Year of Plot

The years between 2014 and 2016, when the Islamic State was at the apex of its power and influence, were when most individuals attempted to travel. Of the 32 individuals, 21 (66 percent) attempted to travel between 2014 and 2016. Six had attempted travel in 2014, 10 in 2015, and five in 2016. The contrast as the Islamic State began to suffer military reversals and lose territory is stark: only two individuals tried to travel in 2017; just one in 2018; and two in 2019.

There were six individuals whose initial date of travel was unknown. However, by looking at the dates when their plots were thwarted, it can be surmised that most of their initial attempts to travel were also likely to be roughly when the Islamic State was thriving. Of the six, three had their plots foiled in the fall of 2016 and three between May to September 2017.

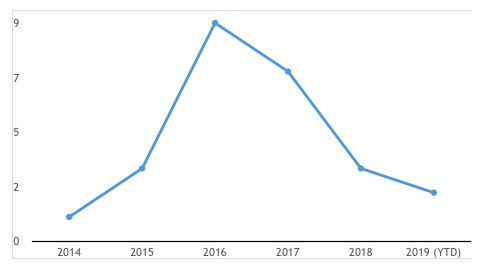

While there were several people blocked from heading to Syria in 2014, there was only one frustrated traveler failed plot that year: Nadir Syed’s. There was a slight increase in plots in 2015, to three, before a jump in 2016, when there was nine frustrated traveler plots. There was then a slow decline from that point: seven in 2017 and three in 2018. However, at time of writing (July 2019), there have already been two frustrated traveler plots in 2019. One was the aforementioned plot in Italy, with the two alleged perpetrators being arrested in April 2019.15 The other was in France, where it is alleged a 17-year-old frustrated traveler was part of a broader cell suspected of likely targeting the police in a firearms attack. This individual was arrested in February 2017, aged 15, while trying to travel to Syria and was jailed for three years (with two years suspended).16

If that ratio was replicated over the next six months, this year would see a slight increase in frustrated travelers compared to 2018.

Target

Thirteen (52 percent) of the 25 frustrated traveler plots were targeting France. Four (16 percent) were targeting the United Kingdom and three (12 percent) were targeting Germany. The remaining five plots were against Sweden (twice), Italy, the Netherlands, and Romania (one each).

France, the United Kingdom, and Germany are the European countries17 most frequently targeted by Islamist terrorists, so it is normal to also see them highly represented in plots by frustrated travelers. What is perhaps most surprising is that another country that has been targeted frequently by Islamist terrorists—Belgium—is not represented at all.**18 Why this may be is unclear. While, according to International Center for Counter-Terrorism data, 584 individuals successfully traveled from Belgium to Syria, there was another 99 who were prevented from doing so.19 None, however, are known to have then planned an attack in retaliation.**

Profile

Of the 32 frustrated travel plotters, 23 were male (72 percent) and nine were female (28 percent). This is a disproportionately high number of women. By comparison, one study of all “Islamism-related offenses” in the United Kingdom between 1998 and 2015 found that only seven percent were committed by women.20 In that entire time period, only three women had attempted to carry out a terrorist attack, with most convictions related to support roles (assisting an offender or fundraising, for example).21 The presence of so many females among frustrated travel plotters is stark.

Converts were involved in eight plots overall. Six of these convert plots pertained to France, one to Italy, and one to the United Kingdom. One plot, from France in October 2016, saw two converts plan together.22 Therefore, in total, nine of the 32 individuals (28 percent) were converts to Islam. By way of comparison, the aforementioned study of all “Islamism-related offenses”c in the United Kingdom between 1998 and 2015 found that 16 percent were converts. A study of all al-Qa`ida-related offenses in the United States between 1997 and 2011 found that 23 percent were converts.23 Four of the nine converts in frustrated traveler plots were females.

Seven of the total plots (28 percent) involved minors. Five related to France, one to Germany, and one the United Kingdom. In one plot—the one involving two converts in France in October 2016—two minors allegedly planned together. Therefore, eight of the 32 individual frustrated travelers were minors (25 percent).

The youngest individual to be implicated was a 15-year-old female—Safia S.—who made it from Germany to Turkey before being collected by her mother. While in Turkey, German prosecutors alleged that members of the Islamic State encouraged her to carry out an attack in Germany—which she did in February 2016, stabbing and injuring a policeman in Hanover.24 Safia S. was subsequently jailed for six years, having been convicted of attempted murder, grievous bodily harm, and supporting a foreign terrorist organization (the Islamic State).25

Lethality of Attacks

Eight of the 25 plots (32 percent) led to injuries or deaths. Six took place in France, one in Germany, and one in Sweden. One occurred in 2015; five occurred in 2016; and two in 2017. In total, frustrated traveler attacks led to 18 injuries and seven deaths over these eight plots.

The most lethal frustrated traveler attack was that carried out by Rakhmat Akilov in Stockholm in April 2017. He injured 10 and killed five when he drove a hijacked truck into civilians on the busy shopping street of Drottninggatan. However, this attack could have been even more deadly; an explosive device comprised of gas canisters and nails that was stowed in the back of his truck failed to detonate properly.26 Akilov was subsequently tried in Sweden, where he was found guilty of murder and attempted murder and jailed for life in June 2018.27

Rapidity of Planning

Fourteen of the 32 individuals (44 percent) profiled either had their plot thwarted or successfully carried it out within one year of their initial attempt to get to Syria failing. This suggests that failed attempts at travel are a possible indicator of potential, future attack planning occurring within a relatively short time period.

Of these 14, seven acted within three months, a particularly rapid response to being prevented from traveling for terrorist purposes. Another two acted within six months, and five between six to 12 months. This speed of action partially speaks to these individuals’ desire to act rapidly rather than meticulously. For example, French citizen Moussa Coulibaly was stopped in Turkey on his way to Syria on January 29, 2015; he stabbed and injured three soldiers in Nice just five days later.28

Eight other individuals either had their plot thwarted or successfully carried it out between one to two years after their first failed travel attempt. Another three either had their plot thwarted or successfully carried it out within two to three years. With one individual—Hardi N. in the Netherlands—it was even longer from his first attempt to travel to being arrested on suspicion of planning an attack. He first attempted to travel in 2014 and his alleged plot was thwarted in September 2018. Hardi N. had spent part of this time—three months—in jail, having been convicted in the Netherlands for attempting to travel to Syria in the first place.29

With six individuals, their initial date of attempted travel was unknown.

Plot Sophistication

The attacks planned by frustrated travelers were relatively unsophisticated. The largest amount—nine of the 25 plots (36 percent)—involved solely the use of an edged weapon. There was no discernible trend among the remaining 16. Two plots involved just explosives, two involved just firearms, and two involved both. There was one example of a vehicular plot; an explosives plot; a firearm with an edged weapon plot; and a combined vehicular and explosives attack. As earlier referenced, one attack simply involved strangling. On four occasions, the type of weapon to be used was unspecified or the plot was insufficiently developed for authorities to discern.

The most sophisticated plot by a frustrated traveler was thwarted in Germany in June 2018. Sief Allah H., a Tunisian asylum seeker believed to be in contact with the Islamic State, had been prevented from getting to Syria on two occasions in the fall of 2017. Both times, he was prevented from crossing the border in Turkey.30 With these plans thwarted, he is then alleged to have successfully produced ricin before being arrested in Cologne prior to being able to execute his attack on an unspecified target. This was the first time that ricin was successfully produced as part of an alleged Islamist plot in Europe.

Lone Plotters vs. Frustrated Traveler Cells

The fact that there was 25 plots involving frustrated travelers but 32 separate individual plotters shows that they sometimes planned and plotted together.

One example of this comes from France. Ismael K., Djebril Amara, and Antoine Frérejean were based in the south of France, met online, and often communicated that way. All were interested in traveling to Syria. Yet Ismael K.’s mother had reported him to the authorities (he was only 17), leading to him being questioned by authorities in November 2014 and deciding it was impossible to make the journey to the caliphate.31 Ismael K. was in contact with an Islamic State member online, ‘Abu Hussain el-Britani’, who encouraged him to carry out an attack in France instead.32 While the author has not been able to definitively establish it is the same person, ‘Abu Hussain el-Britani’ was also a nom de guerre adopted by Junaid Hussain, a British citizen based in Syria who British intelligence concluded had used social media to plan attacks in the West “on an unprecedented scale.”33 Hussain was killed in a U.S. airstrike in Raqqa, Syria, in August 2015.34

For his part, Amara later told investigators he did not feel “able” to make the trip.35 However, inspired by the Charlie Hebdo attacks of January 2015, Amara began to subsequently plan an attack on Fort Béar military base in the Pyrénées-Orientales.36 Yet with Ismael K. expressing willingness but his enthusiasm only tepid, Amara says he shelved the plot by March 2015.d The cell was arrested four months later. In April 2018, all three were found guilty of committing criminal conspiracy. They were jailed for nine years each.37

It was not always the case that the members of a frustrated traveler cell knew each other well. Another example from France involved Adel Kermiche and Abdelmalik Petitjean. Both had allegedly tried to go to Syria—Adel Kermiche on two occasions, in March 2015 and May 2015,38 and Petitjean in June 2016.39 With their plans thwarted, it is alleged they decided to storm a church in Normandy, slitting the throat of a priest, Jacques Hamel, in July 2016. Both declared their allegiance to the Islamic State.40 However, they had only allegedly been in contact with each other for the first time four days before the attack, via the encrypted messaging app Chatogram.41 Kermiche and Petitjean are yet to face trial for their alleged role in Hamel’s murder.

Role of the Islamic State

In 13 of the 25 plots (52 percent), it is known that one or more cell member was in contact with the Islamic State. In 11 of these 13 plots, the contact was solely electronic, as opposed to face-to-face. One exception to this was Bilal Taghi, as two of his brothers had successfully joined the Islamic State and were killed fighting on its behalf.42 In September 2016, Taghi stabbed two guards in the prison he was incarcerated in for having attempted travel to Syria. He is due to be tried in 2019 for the attempted murder of the guards and faces life in prison if convicted.43

The other plotter who had face-to-face contact with the Islamic State was Safia S. from Germany, who met Islamic State members while in Turkey.

As noted, far more numerous were the examples of Islamic State fighters providing encouragement or guidance solely electronically. An example from France involved Hakim Marnissi, who tried to travel to Syria twice, in October and December 2014.44 With both attempts unsuccessful (for uncertain reasons), he was barred from leaving France in February 2015. However, Marnissi was in contact with a French citizen called Mustapha Mokeddem who had made it to Syria in December 2014 and joined the Islamic State. It was Mokeddem who was responsible for radicalizing Marnissi prior to his first attempt to travel to Syria.45 When Marnissi was banned from leaving France in February 2015, Mokeddem encouraged him to strike in France instead. Marnissi subsequently acquired knives in preparation for an attack on soldiers at a French naval base, during which he hoped to be ‘martyred.’ He was arrested in November 2015 and eventually jailed for 10 years for criminal conspiracy.46

However, a lack of hands-on and personal, operational guidance from the Islamic State was not an impediment for several others, who proved to be self-starters. One example saw Aydin Sevigin fail in two attempts to travel from Sweden to Syria in the summer of 2015, being stopped first in Greece and then in Turkey. He decided to carry out a suicide bombing in Sweden instead. Sevigin was arrested in January 2016 and sentenced to five years in jail six months later, having been charged with preparation for a terrorist crime.47

Conclusion

The frequency of frustrated travelers planning attacks in Europe has dipped from its 2016 peak. These plots are sometimes unsophisticated and over two-thirds of the time (68 percent) were thwarted by the authorities. This is possibly because these individuals are already on the security radar for attempting to travel to a conflict zone in the first place.

Furthermore, the destruction of the caliphate in Iraq and Syria should theoretically lead to a further reduction in frustrated travelers, as there is no longer a ‘state’ governed by terrorists to travel to. There is some reason to be optimistic that this will prove to be the case: the trend lines point to frustrated traveler plots in Europe decreasing in rate from their 2016 peak.

However, frustrated traveler plots have outlived the existence of the caliphate. In current form, there is a possibility there may even be a very small uptick in Europe in 2019 when compared to the previous year.

It should also be noted that any wane in this phenomenon is dependent on a new conflict zone failing to emerge that can draw foreign fighters on anything approaching the scale that Syria did. The likelihood of this remains to be seen, but while the nucleus of the Islamic State’s caliphate has been removed, the Islamic State retains a presence across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. In the April 2019 video of Abu Bakr-al Baghdadi that was released by the Islamic State’s media arm, he emphasized that despite recent military reverses, the Islamic State had carried out attacks in eight different countries. The group is long known to have had a presence in Yemen, Libya, and Afghanistan. However, al-Baghdadi also specifically referred to the April 2019 attacks in Sri Lanka, pledges of allegiance received by Islamist groups in Burkina Faso and Mali, as well as protests taking place in Sudan and Algeria.48

Therefore, the Islamic State has potential options in terms of areas in which it can once more seek to try and control territory. These factors mean that while frustrated traveler plots may not be the most numerous kind of plot Europe faces, they are certainly not a phenomenon about which policymakers should be complacent. CTC

Robin Simcox is the Margaret Thatcher Fellow at The Heritage Foundation, where he specializes in counterterrorism and national security policy. Follow @RobinSimcox

* July 22, 2019 update: This number reflected the author’s best efforts to create a comprehensive database of frustrated traveler plots from open source information, which is a difficult task for two main reasons. The first is the large volume of open source reports in different countries and different languages. The second is that media reports on terrorist plots may not always mention the frustrated traveler dimension. After this article was published, the author was made aware of a number of frustrated traveler plots in Belgium and France not included in his dataset and will include these, and any other additional cases he is made aware of, in expanding his database in the future. He thanks Guy Van Vlierden and Jean-Charles Brisard, respectively, for highlighting the additional cases.

** July 22, 2019 update: This finding requires revision. After the publication of this study, the Belgian journalist Guy Van Vlierden drew attention to two frustrated traveler plots in Belgium not included in the author’s database published in this article. See Guy Van Vlierden, “In Belgium, at least two plots by ‘frustrated travelers’ have been thwarted actually …,” Twitter, July 19, 2019.

Substantive Notes

[a] In July 2014, Abu Sayyaf’s emir, Isnilon Hapilon, pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. (See Maria A. Ressa, “Senior Abu Sayyaf leader swears oath to ISIS,” Rappler, August 4, 2014.) Abu Sayyaf’s current relationship with the Islamic State, following Hapolin’s death at the hands of the Philippines government’s army in October 2017, is ambiguous. However, the Islamic State has claimed credit for terrorist attacks that occur in traditional Abu Sayyaf territory. (See Thomas Joscelyn, “Islamic State claims suicide bombings at Catholic cathedral in the Philippines,” FDD’s Long War Journal, January 27, 2019.)

[b] A conflicting report states that he was going to join the Islamic State. See “Police round off terror raids, more details emerge about suspects,” Dutch News, September 28, 2018.

[c] According to that study, the criteria for what constitutes an “Islamism-related offense” was “a self-proclaimed Islamism-inspired motive (i.e. a suicide video or letter claiming affiliation to a proscribed Islamist organisation or discussing key jihadist concepts, such as martyrdom and jihad); An Islamism-inspired motive identified and proven as such during trial; Membership of a proscribed Islamist organisation or links to members or associates for purposes that demonstrably, and knowingly, furthered an Islamism-inspired terrorist-cause; Provision of material or financial support to a member or an associate of a proscribed Islamist organisation knowing that it may be used for terrorist purposes; Frequent contact with a member or an associate of a proscribed Islamist organisation as part of the offence; Evidence of foreign travel to join and fight for or receive terrorist training from a militant Islamist organisation; Possession (at time of arrest) of jihadist material (including, but not limited to, teachings from prominent jihadist ideologues as well as documents, audio recordings and videos that provide instructional material for Islamism inspired purposes and/or encourage or glorify acts of jihadist terrorism).” See Hannah Stuart, “Islamist Terrorism Analysis of Offences and Attacks in the UK (1998-2015),” Henry Jackson Society, March 2017, pp. xiv-xv.

[d] Djebril Amara has stated that Antoine Frérejean refused to take part in the plot, so he is excluded from the dataset. Marianne Enault, “Projet d’attentat de Fort Béar: le récit rare de la radicalization,” Journal Du Dimanche, April 9, 2018.

Citations

[1] “Dutch arrests: Bomb-making materials seized by police,” BBC, September 28, 2018.

[2] “Eighth report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh) to international peace and security and the range of United Nations efforts in support of Member States in countering the threat,” United Nations Security Council, February 1, 2019.

[3] “Italy Arrests Italian, Moroccan for Planning ISIS Attacks,” Asharq al-Aswat, April 17, 2019.

[6] “France jails ‘jihadist’ woman accused over foiled terror attack,” France 24, April 12, 2019.

[7] For more information on this cell, see Robin Simcox, “The 2016 French Female Attack Cell: A Case Study,” CTC Sentinel 11:6 (2018): pp. 21-25.

[9] “Philippine conflict: Duterte says Marawi is militant-free,” BBC, October 17, 2017.

[11] Vivienne Gulla, “Duterte warns tourists against visiting Zamboanga,” ABS-CBN News, April 23, 2019.

[12] Jamie Grierson, “Man jailed for planning Isis-inspired beheading,” Guardian, June 23, 2016.

[13] “Police round off terror raids, more details emerge about suspects,” Dutch News, September 28, 2018.

[14] “Dutch arrests: Bomb-making materials seized by police.”

[15] “Italy arrests 2 terror suspects training for combat in Syria,” Associated Press, April 17, 2019.

[16] “Attentat déjoué contre l’Elysée : un cinquième suspect arrêté à Strasbourg,” Parisien, May 7, 2019.

[18] For context on Islamic State-linked plots in Belgium during the 2014-2017 time period, see Guy Van Vlierden, Jon Lewis, and Don Rassler, Beyond the Caliphate: Islamic State Activity Outside the Group’s Defined Wilayat – Belgium (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2018).

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Stockholm lorry attacker Rakhmat Akilov jailed for life,” BBC, June 7, 2018.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Nice : en 2015, un terroriste attaquait trois soldats au couteau,” Figaro, July 15, 2016.

[29] “Dutch arrests: Bomb-making materials seized by police.”

[35] Ibid.

[36] Marianne Enault, “Projet d’attentat de Fort Béar : le récit rare de la radicalization,” Journal Du Dimanche, April 9, 2018.

[39] “France church attack: ‘Gentle’ boy who became a killer,” BBC, July 28, 2016.

[40] “Priest Killers ‘Pledge IS Allegiance In Video,’” Sky News, July 28, 2016.

[41] Elise Vincent, “Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray, histoire d’une haine fulgurante,” Monde, November 8, 2016.

[44] Soren Seelow, “Un projet d’attaque contre des militaires déjoué à Toulon,” Monde, November 11, 2015.

[47] “Teaching student jailed over Sweden terror plot,” Local, June 2, 2016.

[48] Robin Wright, “Baghdadi Is Back – And Vows That ISIS Will Be, Too,” New Yorker, April 29, 2019.

Skip to content

Skip to content