Abstract: Russia has done what many thought was impossible in Syria. It has helped Syrian President Bashar al-Assad reconquer most of the country’s major cities and nearly two-thirds of its population. Moscow adopted a military approach that combined well-directed fires and ground maneuver to overwhelm a divided enemy. But it also used extraordinary violence against civilians and provided diplomatic cover when Syrian forces used chemical weapons. Moving forward, Russia faces considerable challenges ahead. Syria is a fractured country with an unpopular regime and massive economic problems; terrorist groups like the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida persist; and Israel and Iran remain locked in a proxy war in Syria.

Just four years after directly entering the Syrian war, Russia has done the unthinkable. It has helped Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s retake much of the country from rebel control.1 Moscow’s air campaign in Syria was its largest outside of Russian territory since the end of the Cold War.a To be sure, there are still areas of resistance like Idlib, and Turkish and Kurdish forces control terrain in northern and eastern Syria. But the battlefield victories in Syria have been undeniable. With Russian assistance, Syrian- and Iranian-supported ground forces retook Deir ez-Zor in the east and Aleppo, Homs, Damascus, and other cities across the country. None of this looked possible in late 2015, when Russian policymakers assessed that the Syrian regime might collapse without rapid and decisive assistance. As Russian leader Vladimir Putin remarked in October 2015, “The collapse of Syria’s official authorities will only mobilize terrorists. Right now, instead of undermining them, we must revive them, strengthening state institutions in the conflict zone.”2

To retake territory, Moscow adopted a military approach that combined well-directed fires and ground maneuver to overwhelm a divided enemy. Instead of deploying large numbers of Russian Army forces to engage in ground combat in Syria—as the Soviet Union did in Afghanistan in the 1980s—Moscow relied on Syrian Army forces, Lebanese Hezbollah, other militias, and private military companies as the main ground maneuver elements. The Russian Air Force and Navy supported these forces by conducting strikes from fixed-wing aircraft and ships in the Mediterranean and Caspian Seas.

Moscow has used its battlefield successes in Syria to resurrect its great power status in the Middle East. Russia now has power projection capabilities in the region with access to air bases like Hmeimim and ports like Tartus. Russian diplomats are leading negotiations on regional issues like a Syrian peace deal and refugee returns, and every major country in the region—such as Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran—works with Moscow on foreign policy issues. As one Middle East leader recently told the author: “The Russians are now a dominant—perhaps the dominant—power in the Middle East.”3 Russia’s resurgence in the Middle East has been facilitated by the confused picture over the drawdown of U.S. military forces inside Syria.

The Syrian war has also provided Russia’s military with an unparalleled opportunity to improve its strike, intelligence, and combined arms capabilities. After a period of military reforms from 2008 to 2012 and a large modernization program, Moscow has been able to test its forces in combat. Over the course of the war, thousands of officers rotated through the campaign to gain combat experience and secure promotions.4 Russia also hopes to expand its arms sales with weapons and systems tested in the Syrian war.5 The experience will shape Russian military thinking, drive procurement decisions, increase arms sales, and influence personnel decisions for years to come.

Despite these battlefield successes, however, Russia used extraordinary violence against civilians, targeted hospitals, and provided diplomatic cover when Syrian forces used chemical weapons against their own population.6 In addition, Moscow and its partners face significant challenges ahead in Syria. The Islamic State and al-Qa`ida-linked groups such as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and Tanzim Hurras al-Din still have a presence in Syria and neighboring countries like Iraq and Turkey. Syrian government reconstruction has been slow and inefficient, adding to the litany of political and economic grievances with the Assad regime. And Israel and Iran are engaged in a proxy war in Syria.

Fears of a Libya Redux

Moscow’s decision to become directly involved in the Syrian war in 2015 was motivated by several issues. First, Russian leaders were concerned that Washington would overthrow the Assad regime and replace it with a friendly government. Syria had long been an important ally of Russia. In 1946, the Soviet Union supported Syrian independence and agreed to provide military help to the newly formed Syrian Arab Army. This cooperation continued throughout the Cold War and under Russian President Vladimir Putin.7 Russian military leaders also wanted to maintain access to the warm water port at Tartus, used by the Russian navy for power projection into the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean.

Russian leaders like General Valery Gerasimov, the chief of the General Staff of Russian Armed Forces, worried about U.S. regime change in Syria based, in part, on the United States’ role in overthrowing regimes in Afghanistan in 2001, Iraq in 2003, and Libya in 2011.8 Gerasimov viewed the Libyan war as a textbook example of the United States’ new way of warfare, combining precision-strike operations using special forces and intelligence support to non-state groups—what Gerasimov referred to as the “concealed use of force.”9 As Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov also remarked, Moscow was alarmed “that foreign players [like the United States] will get imbued with this problem and will not only condemn the violence [in Syria], but subsequently repeat the Libyan scenario, including the use of force.”10

Losing Syria—or, at the very least, watching Syria further deteriorate into a bloody civil war—was particularly worrisome because Moscow had just lost its ally in Ukraine. The 2014 revolution there had ushered in a pro-Western government in Kiev, further fueling Russian fears of U.S. activism. As General Gerasimov remarked, “The experience of military conflicts—including those connected with the so-called color revolutions in North Africa and the Middle East—confirms that a perfectly thriving state can, in a matter of months and even days, be transformed into an arena of fierce armed conflict, become a victim of foreign intervention, and sink into a web of chaos, humanitarian catastrophe, and civil war.”11 According to Russian officials like Gerasimov, the primary culprit in most of these campaigns was the United States.12

Moscow’s fears of a U.S. military intervention were seemingly confirmed when U.S. President Barack Obama called for Assad to step down in February 2015 and vowed to aid rebel groups. “We’ll continue to support the moderate opposition there and continue to believe that it will not be possible to fully stabilize that country until Mr. Assad, who has lost legitimacy in the country, is transitioned out,” Obama remarked.13 Throughout 2015, U.S. policymakers debated greater involvement in Syria by aiding rebel groups. In early 2015, for example, a delegation of U.S. senators led by John McCain visited Saudi Arabia and Qatar to discuss increasing support to Syrian rebels.14 McCain had also secretly visited rebel leaders inside Syria about the possibility of providing heavy weapons to them and establishing a no-fly zone in Syria to help topple Assad.15 Near the end of 2015, McCain and U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham publicly supported the deployment of 10,000 troops to Syria.16

Second, Russian leaders were concerned that the Islamic State, al-Qa`ida, and other terrorists could use territory in Syria and Iraq to attract more fighters, improve their capabilities, and spread terrorism in and around Russia. After all, an estimated 9,000 fighters from Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia had traveled to Syria and Iraq to fight with groups like the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida.17 Russia had also suffered several terrorist attacks from Islamist extremists linked to—or inspired by—the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida, which put its security agencies on high alert. In 2011, a suicide bomber detonated at Domodedovo International Airport in Moscow, killing 37 people. In 2013, there were two suicide bombings in the city of Volgograd perpetrated by jihadis from the Caucasus Emirate. In 2015, Islamic State operatives in Egypt exploded a bomb on Russian Metrojet Flight 9268, killing all 217 passengers and seven crew members.18 In late 2015, Alexander Bortnikov, the head of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), expressed grave concern about the evolving threat and warned that terrorists in Syria were plotting to conduct attacks in Russia.19

Russian leaders were understandably concerned about the situation in Syria. Al-Qa`ida’s affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra, had driven back Syrian government forces in the northwest and threatened major population centers in southern Syria in 2015. Islamic State forces also controlled significant amounts of territory in eastern and northern Syria, and they were conducting attacks in central and western parts of the country.20 For Moscow, the stakes in Syria were high.

Russia’s Grand Entrance

In late 2015, Putin finally put his foot down. In a speech at the United Nations in September 2015, Putin vowed to support the Assad regime. “We think it is an enormous mistake to refuse to cooperate with the Syrian government and its Armed Forces who are valiantly fighting terrorism face-to-face,” he said.21 Over the summer of 2015, Russian, Iranian, and Syrian leaders discussed ramping up military operations. Syrian officials and the head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force (IRGC-QF), Qassem Soleimani, flew to Moscow to coordinate direct military engagement in Syria.22 To facilitate operations, Russia and Syria also signed a treaty stipulating the terms and conditions for Russia’s use of Hmeimim Air Base, southeast of the city of Latakia.23 Russia then began to pre-position air, naval, and ground forces in and near Syria in preparation for military operations.24

At the end of September 2015, Russia conducted its first airstrikes in support of Syrian forces around the cities of Homs and Hama. While Russia had conducted some air operations during the First and Second Chechen Wars in the 1990s and 2000s, as well as in Georgia in 2008, Russian pilots had flown few combat sorties since then.25 Despite limited recent activity, Moscow conducted 1,292 combat missions against 1,623 targets in October 2015 alone from its fleet of 32 combat aircraft.26 Many of these strikes were of low accuracy, and Russian aircraft used unguided weapons to hit targets in urban areas, causing substantial collateral damage. Russian aircraft lacked targeting pods and high-precision weapons to conduct accurate strikes early in the conflict, though Russian capabilities and precision-strike improved over the course of the war.27 Russia also benefited from forward air controllers deployed with Syrian and other ground units, who helped call in airstrikes.28

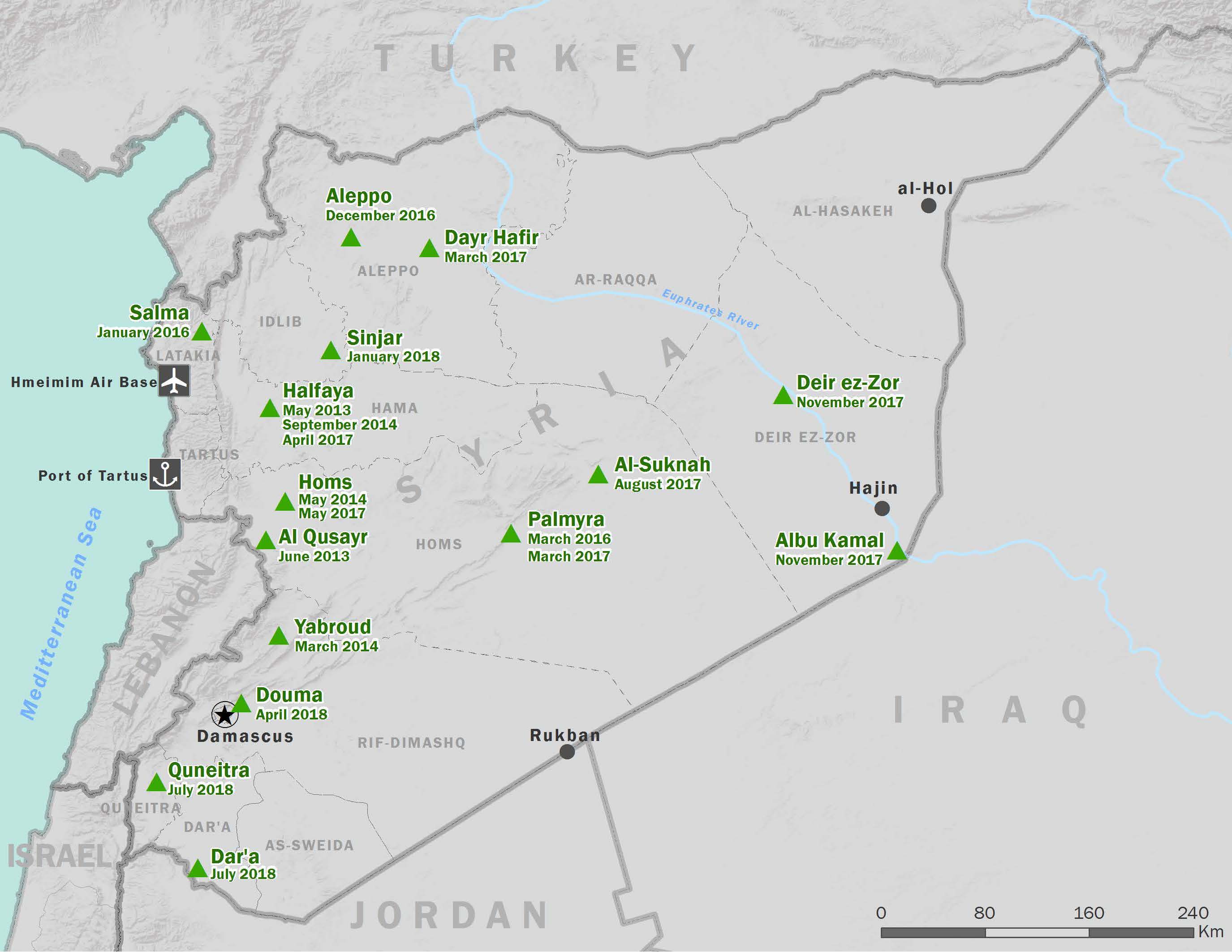

Over the next three years, Syrian Army and allied forces retook successive Syrian cities. As Figure 1 highlights, examples included Aleppo, Homs, Palmyra, and Deir ez-Zor. By the end of 2018, the Syrian government had reconquered most of the east, south, and west up to the Euphrates River. In northern Syria, the Russians remained in close cooperation with Turkey, which controlled territory north of Aleppo. By 2019, the Syrian government—with Russian and Iranian support—controlled most of Syria’s major cities.

Russia’s battlefield campaign was successful for three main reasons. First, Moscow adopted a light footprint approach, which combined fire and maneuver elements. Second, Syrian Army forces and their partners were effective at clearing and holding territory. Third, the Syrian insurgency was decentralized and fractured, severely weakening its combat effectiveness.

Light Footprint Strategy

Russian leaders adopted a light footprint strategy that included a mix of fire and maneuver elements. Unlike Moscow’s approach in Afghanistan in the 1980s, which involved a heavy footprint of 115,000 Soviet forces to fight the Afghan mujahideen, Russian political and military leaders adopted a vastly different approach in Syria beginning in 2015.29 Syrian Army forces served as the main maneuver element to take back territory, not the Russian Army. Syrian forces were supported by militia forces like Lebanese Hezbollah (which received support from Iran’s IRGC-QF), and private military contractors like the Wagner Group (which received training and other aid from the Russian military).30 These forces did most of the fighting and held territory once it was cleared, with help from Russian special operations forces on the ground.31

Russia used well-directed fires to aid these ground forces and overwhelm rebel positions. Beginning in September 2015, Russian ships and submarines fired Kalibr land-attack cruise missiles from the Caspian and Mediterranean Seas at rebel positions. Russia’s inventory of aircraft included Su-24M2 bombers, Su-25SM/UB attack aircraft, Su-35S fighters, Su-34 fighter-bombers, Su-30SM heavy multirole fighters, and Mi-24P and Mi-35M attack helicopters. Tu-95MS and Tu-160 strategic bombers deployed Kh-555 and newer Kh-101 air-launched cruise missiles against targets in Syria. Moscow also fielded Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile systems, Bastion-P anti-ship missiles, and other advanced weapons. Effective close air support was critical to the Syrian Army’s offensives in Aleppo, Homs, Deir ez-Zor, Daraa, Damascus, Palmyra, and other locations.32

To coordinate its air-ground campaign, Russia integrated military operations with the Syrian and Iranian governments, including setting up a Coordination Center for Reconciliation of Opposing Sides (CCROS) headquartered at Hmeimim Air Base.33 Russia also helped establish a coordination center in Baghdad, which included liaisons from Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Israel. The center facilitated intelligence sharing and deconflicted air operations.34

While Russia’s mix of fire and maneuver was similar in some ways to the U.S. model in Kosovo in 1999, Afghanistan in 2001, and Libya in 2011, it was different in one critical respect.35 Russia adopted a punishment strategy, not a population-centric one characterized by winning local hearts and minds.36 Russian and allied military forces inflicted civilian harm on opposition-controlled areas using artillery and indiscriminate area weapons, such as thermobaric, incendiary, and cluster munitions.37 As the Russians demonstrated in Grozny during the Second Chechen War, a punishment strategy is designed to raise the societal costs of continued resistance and coerce rebels to give up.38 The Russian and Syrian militaries used extraordinary violence against civilians. Russia committed human rights abuses, triggered the displacement of millions of refugees and internally displaced persons, caused large-scale destruction of infrastructure, and conducted wanton killings of civilians. As one Human Rights Watch report concluded:

Russia continued to play a key military role alongside the Syrian government in offensives on anti-government-held areas, indiscriminately attacking schools, hospitals, and civilian infrastructure. The Syrian-Russian military campaign to retake Eastern Ghouta in February [2018] involved the use of internationally banned cluster munitions as well as incendiary weapons, whose use in populated areas is restricted by international law.39

Moscow also provided diplomatic cover when Syrian forces used chemical weapons against its own population. In August 2013, the Syrian government used sarin against rebel positions around Ghouta, killing more than 1,400 people.40 In April 2017, Syrian aircraft operating in rebel-held Idlib province conducted several airstrikes using sarin. The strikes, which occurred in the town of Khan Sheikhoun, killed an estimated 80 to 100 people.41 In April 2018, Syrian government forces launched a chlorine attack in the southwestern city of Douma. As a declassified French intelligence report concluded, “Reliable intelligence indicates that Syrian military officials have coordinated what appears to be the use of chemical weapons containing chlorine on Douma, on April 7.” The report also blamed Russia for creating a conducive environment for these types of attacks: “Russian military forces active in Syria enable the regime to enjoy unquestionable air superiority, giving it the total freedom of action it needs for its indiscriminate offensives on urban areas.”42

While Russia’s light footprint strategy was ultimately successful in retaking territory, its punishment campaign caused significant civilian casualties and human rights abuses.

Better Than Expected Maneuver Forces

As Russian leaders realized, air power alone does not win wars since ground forces are generally needed to retake territory.43 Russia’s light footprint strategy hinged on an effective ground component. As the U.S. military discovered in Afghanistan and Iraq, local forces can be organizationally inept, deeply corrupt, politically divided, and poorly educated.44 An ineffective partner can undermine even the most well-intentioned counterinsurgency or counterterrorism campaign, regardless of how much money, equipment, and training is provided.45

The Syrian Army was better than some analysts predicted, especially when aided by air and naval strikes.b The Russian military deployed forward air controllers, embedded with ground units, to call in strikes and coordinate air-ground operations.46 One example of the integration of air power and maneuver forces was in Syria’s industrial capital, Aleppo, which Syrian government and allied forces recaptured in December 2016 after a bloody struggle. Dubbed “Operation Dawn of Victory,” Russia conducted intelligence collection from human sources, signals intelligence, and satellite imagery throughout 2016. Moscow then used intelligence derived from those assets and platforms to identify targets and orchestrate an extensive bombing campaign in and around the city to weaken rebel positions.47 In August 2016 alone, Russian aircraft flew an average of 70 sorties per day against targets in Aleppo, using aircraft like Tu-22M3s and Su-34s.48 Russia also leveraged a naval task force in the eastern Mediterranean, which included the aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov.49 In addition, Syrian Air Force fighters conducted hundreds of strikes against fixed rebel positions.50

To complement air and naval attacks, ground forces from Syria’s 15th Special Forces Division, 800th Republican Guard Regiment, 102nd and 106th Republic Guard Brigades, elite Tiger Forces (or Qawat Al-Nimr) and Desert Hawks, and Iranian-backed militia forces conducted ground operations to retake Aleppo from September through December 2016. They focused on encircling rebel positions in eastern parts of the city.51 In addition to air and naval strikes, the Russians supported ground forces with Orlan unmanned aerial vehicles, electronic warfare capabilities, forward air controllers, and soldiers from the 120th Russian Guards Artillery Regiment. By December 2016, ground forces had effectively encircled and crushed rebel groups operating in the city.52 The International Committee of the Red Cross helped oversee the evacuation of civilians and fighters by bus and car out of eastern Aleppo to areas in western Aleppo and in neighboring Idlib.53

There were other battles that highlighted the combination of directed fires and ground maneuver. In May 2017, for example, Syrian Army and allied ground forces retook the city of Homs, once dubbed the capital of the rebellion, with extensive Russian and Syrian air support. In addition, during the 2017 offensive against Islamic State forces in southeastern parts of the country, Syrian Army forces were again effective in retaking territory. Russian Tu-23M3 aircraft made more than 30 sorties on large targets around Deir ez-Zor, and Russian helicopters targeted Islamic State positions.54 Mobile groups of well-trained Syrian Army forces, aided by Russian advisers, took Palmyra by March 2017. In November 2017, the Syrian Army and local militias retook control of Deir ez-Zor city from the Islamic State, which the insurgent group had held since 2014. In July 2018 during Operation Basalt, Syrian Army forces and local allies recaptured the southern city of Daraa, completing the Syrian government’s conquest of the south.55

Among the most effective Syrian Army units was the Qawat Al-Nimr, an elite special forces unit established in 2013. With help from Russian airstrikes and militias like the Al-Ba’ath Battalion, Qawat Al-Nimr units launched an offensive operation in September 2015 to lift the Islamic State siege of Kuweires Airbase in Aleppo province. By mid-November, Syrian Army forces retook the base. In April 2018, Qawat Al-Nimr units and militias conducted successful operations in southern Damascus to clear out Islamic State fighters. The Russian Air Force—including MiG-31 attack aircraft, Su-25 fighters, and Tu-22 long-range bombers—provided heavy support to the offensive.56

Other units were also involved in ground operations. Iran provided substantial assistance to the Assad regime by helping organize, train, and fund over 100,000 Shi`a fighters.57 Up to 3,000 IRGC-QF helped plan and execute campaigns such as the 2016 Operation Dawn of Victory in Aleppo.58 Lebanese Hezbollah deployed up to 8,000 fighters to Syria and amassed a substantial arsenal of rockets and missiles.59 Hezbollah also trained, advised, and assisted Shi`a militias in areas like southwestern Syria.60

Fractured Insurgency

Finally, Russian, Syrian, and allied air-ground operations benefited from a highly fragmented and disorganized insurgency. The United States provided limited assistance to some Syrian rebel groups through the CIA and Department of Defense. But Washington failed to effectively coordinate with Jordan, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Turkey, European countries, and other outside powers. The U.S. military’s train-and-equip program was particularly problematic. Obama Administration officials never agreed on a desired end state in Syria, and U.S. soldiers trained Syrian rebels to counter the Islamic State rather than to do what many rebels wanted: to fight the Assad regime. The Obama administration also prohibited U.S. advisors from deploying into Syria with rebels.61 U.S. military efforts from 2015 were more successful in training, advising, and assisting Syrian Democratic Forces to help retake territory in eastern Syria from the Islamic State.62

To be successful, insurgent groups generally need to establish a centralized organizational structure. Centralized groups are more effective than decentralized ones in identifying and punishing members that defect from the organization or engage in “shirking.”c Shirking occurs when members take actions that fail to contribute to the maximum efficiency of the organization, like taking a nap instead of setting up a roadside bomb to attack a government convoy. Centralized structures are also more effective in helping insurgent leaders govern territory once they control it.63

In Syria, the absence of a cohesive umbrella structure was a major problem for rebel groups—though a blessing for the Russians, Syrians, and Iranians. Instead of an organized insurgency, Syria became a hodgepodge of groups who fought each other rather than consolidating power and territorial gains. The lack of coordination among these groups meant that Russian, Syrian, Iranian, and allied militias were able to exploit their divisions and vulnerabilities, and ultimately wear them down during offensives in Deir ez-Zor, Aleppo, Homs, Damascus, and other locations.

Syria’s Lingering Problems

As the United States discovered in Afghanistan and Iraq, winning a war is not the same as winning the peace afterward. Russian long-term success in Syria may be challenging for several reasons.64

First, Syria is a fractured country with an unpopular regime, herculean economic problems, large-scale infrastructure destruction, lingering animosities, and little or no control of territory in parts of the north, east, and south. Electricity and running water are sparse in many places; infrastructure has been decimated. Medication is often unaffordable, and unemployment is rampant. There is little reconstruction aid coming from international donors, and the Assad regime’s limited reconstruction efforts are focused on consolidating power and rewarding loyalty to the government.65 Three New York Times journalists conducted an eight-day visit through Syria in the summer of 2019 and painted a grim picture of the destruction. “What does victory look like? At least half a million dead, more than 11 million severed from their homes. Rubble for cities, ghosts for neighbors.” Traveling northeast from Damascus to the town of Douma, they provided a chilling account of a country still in ruins: “It seemed to go on for miles, the cigarette ash of the war: apartment buildings that resembled open-air parking garages, doorways spewing gray dust, minarets sticking askew out of the wreckage like half-melted candles in a cake.”66 The United Nations estimates that 83 percent of Syrians live below the poverty line.67

These challenges will continue to plague the Assad regime and its Russian backers. World Bank data places Syria in the bottom one percent of countries worldwide in political stability, bottom two percent in government effectiveness, bottom three percent in regulatory quality, and bottom two percent in control of corruption.68 These numbers should not be reassuring to Russian leaders if they want to establish a modicum of stability in the country.

Second, al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State still have a significant presence in Syria and neighboring countries. The Islamic State lost control of virtually all of the territory it once held in Syria and suffered significant casualties during the final months of its defense along the Hajin-Baghuz corridor. But it is attempting to rebuild its networks east and west of the Euphrates River as part of its desert (or sahraa) strategy.69 Islamic State fighters have taken refuge in areas like the Badiya desert and the Jazira region in Syria, stockpiled weapons and material, kept a low profile (including wearing Bedouin-style clothes), and conducted limited attacks against Syrian government and Syrian Democratic Force targets.70 The Islamic State is particularly strong in Deir ez-Zor province, parts of Raqqah province, and Homs province nearly Palmyra.71

Islamic State strategy and tactics in Syria appear to mirror the guidelines laid out in the four-part series titled “The Temporary Fall of Cities as a Working Method for the Mujahideen,” published in the Islamic State newsletter Al Naba.72 The guidance urged Islamic State fighters to avoid pitched battles and face-to-face clashes, conduct hit-and-run attacks, and seize weapons from victims to build up their arsenal. The instructions were similar to the classic guerrilla warfare campaign promulgated by Mao Tse-Tung and Ernesto “Che” Guevara against stronger adversaries.73 The Islamic State has also attempted to rebuild its intelligence networks across Syria. As one United Nations assessment concluded, “The ISIL covert network in the Syria Arab Republic is spreading, and cells are being established at the provincial level, mirroring that which has been happening since 2017 in Iraq.”74

There are still between 15,000 and 30,000 Islamic State fighters in Syria and Iraq, including up to 3,000 foreigners (from outside Iraq and Syria).75 The Iraqi-Syrian border is porous, allowing Islamic State fighters to move across it with relative ease. In addition, the Islamic State is recruiting individuals at locations like al-Hol camp in northeastern Syria (which has approximately 70,000 internally displaced persons, or IDPs), and Rukban camp in southern Syria near the Jordanian border (which has approximately 30,000 IDPs).76 Though there are approximately 10,000 Islamic State fighters housed at al-Hol—including roughly 2,000 foreign fighters (not from Iraq or Syria)—there has been little progress on what to do with them, since many of their home countries do not want them back.77 Nearly 50,000 of the IDPs at al-Hol are under the age of 18, which has raised concerns about youth radicalization.78 In addition, the Islamic State still boasts financial reserves of roughly $50 million to $300 million, sufficient for long-term operations.79

Al-Qa`ida also presents a significant threat and has relations with jihadi networks in areas like Idlib. There are between 12,000 and 15,000 fighters from Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in Idlib, as well as another 1,500 to 2,000 fighters from Tanzim Hurras al-Din.80 While HTS members like Abu Muhammad al-Julani have experienced testy relations with Ayman al-Zawahiri and other al-Qa`ida leaders, HTS maintains strong connections with jihadi networks.81 Tanzim Hurras al-Din has strong connections with al-Qa`ida and is led by Mustafa al-Aruri (also known as Abu al-Qassam), an al-Qa`ida veteran. The organization also boasts a number of other al-Qa`ida veterans, such as Iyad Nazmi Salih Khalil, Sami al-Aridi, Bilal Khrisat, and Faraj Ahmad Nana’a.82

The presence of up to 40,000 to 50,000 jihadi fighters suggests that terrorism will remain a serious problem in Syria for the foreseeable future. In addition, Moscow’s brutality against civilian populations in Syria and close relationship with the Assad regime could make Russia a more significant target of terrorist attacks in the future.

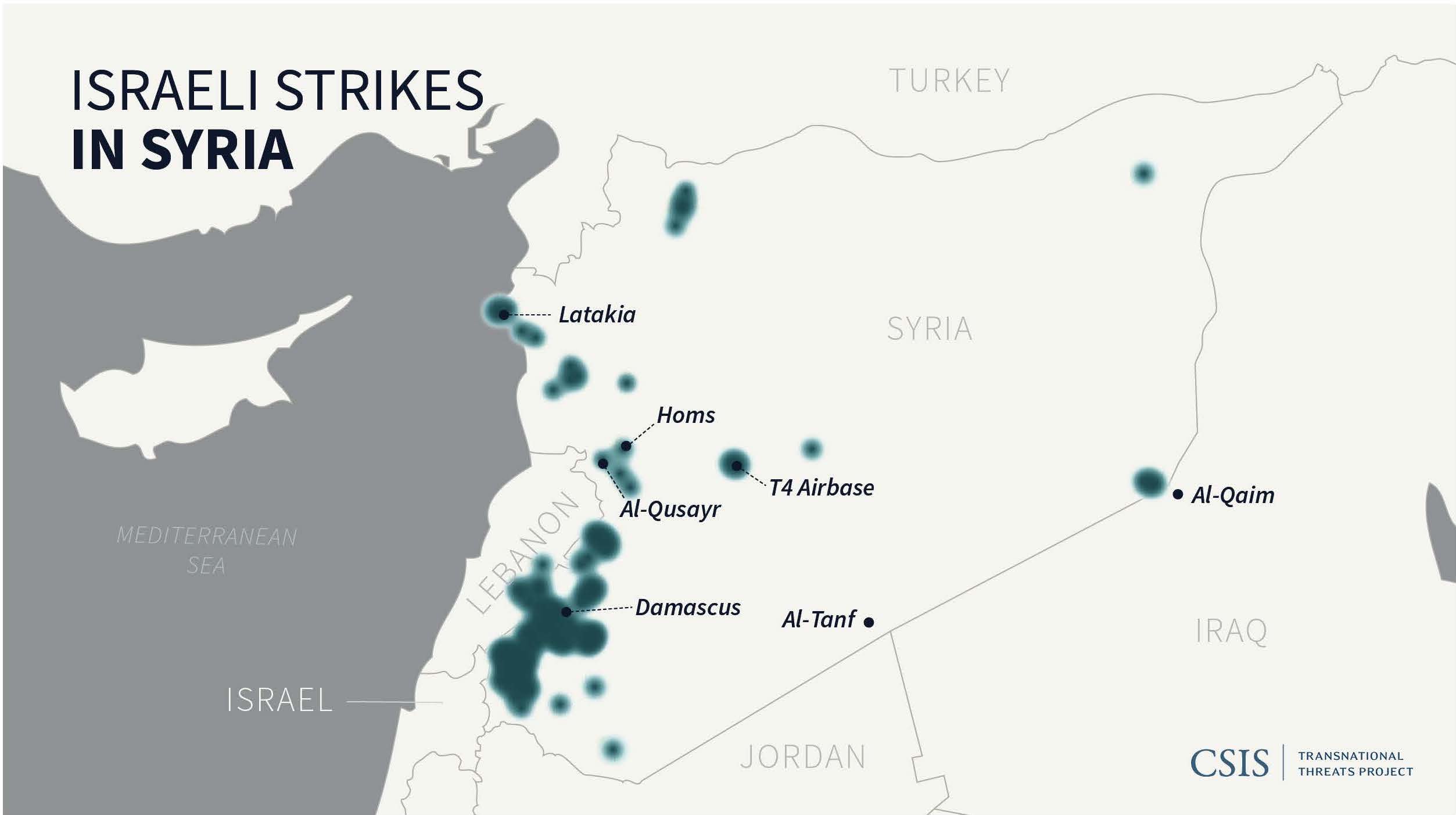

Third, Syria is a proxy battlefield between Iran and Israel, which could trigger further war and put growing pressure on Russia to manage escalation. Israel has conducted hundreds of strikes in Syria against Iranian-linked targets since the beginning of the war, as highlighted in Figure 2. These strikes primarily came from Israeli combat aircraft. Many of these strikes have hit missile-related targets, such as storage warehouses, transportation convoys, and missile batteries.84 As a senior Israeli Air Force officer remarked, “We are continuing with our operational mission against the arming of Hezbollah and Iranian moves to establish themselves in Syria. As far as we are concerned, anywhere we identify consolidation [of Iranian or Hezbollah forces] or the introduction of weapons, we act.”85 Most of Israel’s attacks have been in southwestern Syria, near the Israeli border. The Israelis have hit other targets, such as T-4 Tiyas Airbase in Homs, the airbase north of al-Qusayr, Damascus International Airport, and even Iraq and Lebanon.86

These issues—poor governance, continuing terrorism, and persistent Israeli-Iranian conflict—suggest that Russia faces significant challenges in turning battlefield victories into domestic stability. Before the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, Secretary of State Colin Powell warned President George W. Bush about the downsides of military action. “Once you break it,” Powell said, “you are going to own it.”87 New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman referred to this as the “Pottery Barn rule” after the policy put in place by the U.S.-based retail store.88 Russia now has the unenviable task of trying to pick up the pieces in Syria. Despite Russian battlefield successes thus far, ensuring that Syria is a Russian “victory” in five or 10 years will be a major challenge. And if Moscow fails, war and terrorism may continue to ravage Syria. CTC

Seth G. Jones is the Harold Brown Chair and Director of the Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, as well as the author of Waging Insurgent Warfare: Lessons from the Viet Cong to the Islamic State (Oxford University Press).

Substantive Notes

[a] Since the end of the Cold War, Russia has also conducted air operations in Georgia, Ukraine, and Chechnya. During the Cold War, one of the largest air campaigns was in Afghanistan in the late 1970s and 1980s. See, for example, Lester W. Grau, ed., The Bear Went Over the Mountain: Soviet Combat Tactics in Afghanistan (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1996), and Edward B. Westermann, “The Limits of Soviet Airpower: The Failure of Military Coercion in Afghanistan, 1979-89,” Journal of Conflict Studies 19:2 (1999): pp. 39-71.

[b] There was significant criticism of the Syrian army for a range of issues, from poor training and significant corruption to low morale. See, for example, Tobias Schneider, “The Decay of the Syrian Regime Is Much Worse Than You Think,” War on the Rocks, August 31, 2016.

[c] An organization’s success depends on its ability to motivate members and encourage them to behave in ways consistent with its broader goals and objectives. A lack of discipline among lower-ranking members can waste resources, alienate potential supporters, and undermine military and political efforts. See, for example, Jeremy Weinstein, Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Citations

[1] On control of territory, see, for example, Jonathan Spyer, “Syria’s Civil War Is Now 3 Civil Wars,” Foreign Policy, March 18, 2019, and Charles Lister, “Assad Hasn’t Won Anything,” Foreign Policy, July 11, 2019.

[2] Vladimir Putin, “Remarks at the Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club,” October 22, 2015.

[3] Author interview, senior Middle East leader, July 2019.

[4] Valery Gerasimov, “We Broke the Back of Terrorists,” interview by Victor Baranets, Komsomolskaya Pravda, December 26, 2017.

[5] Michael Kofman and Matthew Rojansky, “What Kind of Victory for Russia in Syria?” Military Review 98:2 (2018): p. 19.

[6] See, for example, Louisa Brooke-Holland and Ben Smith, Chemical Weapons and Syria—In Brief (London: House of Commons, August 2018); Robert J. Bunker, The Assad Regime and Chemical Weapons (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, May 18, 2018); Yasmin Naqvi, “Crossing the Red Line: The Use of Chemical Weapons in Syria and What Should Happen Now,” International Review of the Red Cross 99:3 (2017): pp. 959-993; Zakaria Zakaria and Tamer El-Ghobashy, “Escalating Syrian and Russian Airstrikes in Rebel-Held Idlib Stoke Fears of a Final Showdown,” Washington Post, May 6, 2019.

[8] See, for example, Gerasimov’s speech: [“The Value of Science Is In the Foresight”], Military Industrial Courier, February 26, 2013. The speech was translated into English by Robert Coalson and published in Valery Gerasimov, “The Value of Science Is in the Foresight: New Challenges Demand Rethinking the Forms and Methods of Carrying Out Combat Operations,” Military Review, January-February 2016, pp. 23-29. Also see later statements, such as Valery Gerasimov, “Speech at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Military Sciences,” March 2, 2019. The speech was published in English at “Russian First Deputy Defense Minister Gerasimov,” MEMRI, Special Dispatch No. 7943, March 14, 2019.

[9] Valery Gerasimov, PowerPoint slides, Moscow Conference on International Security, May 23, 2014. The slides were published in Anthony H. Cordesman, Russia and the ‘Color Revolution’: A Russian Military View of a World Destabilized by the U.S. and the West (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 28, 2014).

[10] Sergei Lavrov, “On Syria and Libya,” Monthly Review, May 17, 2011. The text is an excerpt from “Transcript of Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s Interview to Russian Media Following Attendance at Arctic Council Meeting, Nuuk, May 12, 2011,” published on the Russian Foreign Ministry website, May 13, 2011.

[11] Gerasimov.

[12] See, for example, Gerasimov, PowerPoint slides, May 23, 2014.

[13] Byron Tau, “Obama Renews Call for Assad to Step Down,” Wall Street Journal, February 24, 2015.

[15] See, for example, John McCain, “Important visit with brave fighters in #Syria who are risking their lives for freedom and need our help,” Twitter, May 28, 2013.

[17] Richard Barrett, Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees (New York: The Soufan Center, October 2017). Also see Thomas Sanderson et al., Russian-Speaking Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria: Assessing the Threat from (and to) Russia and Central Asia (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2017), p. 2.

[18] On terrorist attacks in Russia leading up to the Russian intervention, see the Global Terrorism Database at the University of Maryland (https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/).

[19] Arsen Mollayev and Vladimir Isachenkov, “Russia Is Feeding Hundreds of Fighters to ISIS — and Some Are Starting to Return,” Associated Press, October 28, 2015. Also see GRU head Igor Korobov’s later comments in A.A. Bartosh, “Trenie’ i ‘iznos’ gibridnoj vojny” [“Friction” and “wear” of hybrid war], Voennaia Mysl 1 (2018).

[20] See, for example, the U.S. government map of “Areas of Influence, August 2014-2015,” published in Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations, Operation Inherent Resolve, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of State, and U.S. Agency for International Development, September 30, 2015, p. 26.

[21] “Statement by H.E. Mr. Vladimir V. Putin, President of the Russian Federation, at the 70th Session of the UN General Assembly,” September 28, 2015.

[23] [“Agreement Between the Russian Federation and the Syrian Arab Republic on the Deployment of an Aviation Group of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation on the Territory of the Syrian Arab Republic,” August 26, 2015]. The text of the agreement can be found at http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201601140019

[24] On Russian military preparations in Syria, see Valery Polovkin ed., Rossikoe Oruzhiye v Siriskom Konflikt (Moscow: STATUS, 2016).

[25] Kofman and Rojansky, pp. 6-23.

[27] See, for example, Ralph Shield, “Russian Airpower’s Success in Syria: Assessing Evolution in Kinetic Counterinsurgency,” Journal of Slavic Military Studies 31:2 (2018): pp. 214-239; Kofman and Rojansky; Lavrov, The Russian Air Campaign in Syria.

[28] On Russian forward air controllers, see, for example, Shield. See also Lavrov, The Russian Air Campaign in Syria.

[29] Stephen Tanner, Afghanistan: A Military History from Alexander the Great to the Fall of the Taliban (New York: Da Capo Press, 2002), p. 266.

[30] On Russian support to organizations like the Wagner Group, see James Bingham and Konrad Muzyka, “Private Companies Engage in Russia’s Non-Linear Warfare,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, January 29, 2018. On Lebanese Hezbollah and IRGC-QF activity, see Nader Uskowi, Temperature Rising: Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and Wars in the Middle East (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2019), pp. 77-96.

[31] On Russian special operations in Syria, see Michael Kofman, “Russian Spetsnaz: Learning from Experience,” Cipher Brief, March 15, 2017; Christopher Marsh, Developments in Russian Special Operations: Russia’s Spetznaz, SOF and Special Operations Forces Command (Ottawa: Canadian Special Operations Forces Command, 2017).

[32] See, for example, Polovkin; Lavrov, The Russian Air Campaign in Syria; Kofman and Rojansky; Sanu Kainikara, In the Bear’s Shadow: Russian Intervention in Syria (Canberra, Australia: Air Power Development Centre, Australian Department of Defence, 2018); Shield.

[33] “Russia Learns Military Lessons in Syria,” Jane’s IHS, 2017.

[34] Kofman and Rojansky, p. 14.

[36] On punishment campaigns, see Seth G. Jones, Waging Insurgent Warfare: Lessons from the Vietcong to the Islamic State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 47-52; Ivan Arreguín-Toft, How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 31-32; Robert B. Asprey, War in the Shadows: The Classic History of Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Persia to the Present (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1994), pp. 108; Nathan Leites and Charles Wolf, Jr., Rebellion and Authority: An Analytic Essay on Insurgent Conflicts (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, February 1970), pp. 90-131.

[37] “World Report 2019,” Human Rights Watch, 2019; “Indiscriminate Bombing of Syria’s Idlib Could Be War Crime, Says France,” Reuters, September 12, 2018; Kainikara, p. 90; Brian Glyn Williams and Robert Souza, “Operation ‘Retribution’: Putin’s Military Campaign in Syria, 2015-2016,” Middle East Policy 23:4 (2016): pp. 42-60.

[39] “World Report 2019,” p. 487.

[40] “Government Assessment of the Syrian Government’s Use of Chemical Weapons on August 21, 2013,” U.S. Intelligence Community, released by the White House, Office of the Press Secretary, August 30, 2013; “Attacks on Ghouta: Analysis of Alleged Use of Chemical Weapons in Syria,” Human Rights Watch, September 10, 2013; Joby Warrick, “More Than 1,400 Killed in Syrian Chemical Weapons Attack, U.S. Says,” Washington Post, August 30, 2013.

[41] “Seventh Report of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism,” United Nations Security Council, October 26, 2017; “Both ISIL and Syrian Government Responsible for Use of Chemical Weapons, UN Security Council Told,” UN News, November 7, 2017; Rodrigo Campos, “Syrian Government to Blame for April Sarin Attack: UN Report,” Reuters, October 26, 2017; Stephanie Nebehay, “Syrian Government Was Behind April Sarin Gas Attack, UN Says,” Independent, September 6, 2017.

[42] “French Declassified Intelligence Report on Syria Gas Attacks,” Reuters, April 14, 2018.

[43] On the limits of air power alone, see, for example, Robert A. Pape, Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War (New York: Cornell University Press, 1996); Daniel L. Byman and Matthew C. Waxman, “Kosovo and the Great Air Power Debate,” International Security 24:4 (2000): pp. 5-38.

[44] See the various inspector general reports, such as Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), Quarterly Report to the United States Congress (Arlington, VA: SIGAR, July 30, 2019), pp. 73-99.

[45] Daniel L. Byman, “Friends Like These: Counterinsurgency and the War on Terrorism,” International Security 31:2 (2006): pp. 79-115; Daniel L. Byman, Going to War with the Allies You Have: Allies, Counterinsurgency, and the War on Terrorism (Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army War College, November 2005).

[46] On Russian forward air controllers, see, for example, Shield. See also Lavrov, The Russian Air Campaign in Syria.

[47] On overall Russian intelligence collection and the bombing campaign, see Roger N. McDermott and Tor Bukkvoll, “Tools of Future Warfare—Russia Is Entering the Precision-Strike Regime,” Journal of Slavic Military Studies 31:2 (2018): pp. 191-213; Shield; Lavrov, The Russian Air Campaign in Syria.

[48] Lavrov, The Russian Air Campaign in Syria, p. 13.

[49] On the role of the Russian navy in Syria, see the naval chapter in Polovkin.

[50] Kainikara, pp. 90-94.

[51] John W. Parker, Putin’s Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Sticker Wicket (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University, July 2017), pp. 44-45.

[52] See, for example, Tim Ripley, Operation Aleppo: Russia’s War in Syria (Lancaster, UK: Telic-Herrick Publications, 2018).

[53] “Syria Conflict: Aleppo Evacuation Operation Nears End,” BBC, December 22, 2016.

[54] Lavrov, The Russian Air Campaign in Syria, p. 15.

[56] On the Tiger Forces, see, for example, Gregory Waters, The Tiger Forces: Pro-Assad Fighters Backed by Russia (Washington, D.C.: Middle East Institute, October 2018).

[57] “Iran’s Priorities in a Turbulent Middle East,” International Crisis Group, April 13, 2018.

[58] On the number of IRGC-QF in Syria, see, for example, the data from Gadi Eisenkot, former chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces, in Bret Stephens, “The Man Who Humbled Qassim Suleimani,” New York Times, January 11, 2019. On IRGC-QF support to combat operations in Syria, see Uskowi, pp. 77-96; Afshon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 204-229.

[59] Uskowi, p. 82.

[60] Author interview, senior Jordanian and U.S. officials, July 2019. See also Phillip Smyth, Lebanese Hezbollah’s Islamic Resistance in Syria (Washington, D.C.: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, April 26, 2018).

[61] On some of the challenges with the train-and-equip program, see “Foreign Fighter Fallout: A Conversation with Lt. Gen. Michael K. Nagata,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 5, 2017; Paul McLeary, “The Pentagon Wasted $500 Million Training Syrian Rebels,” Foreign Policy, March 18, 2016; and Seth G. Jones, Historical Lessons for the Wars in Iraq and Syria (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, April 2015).

[62] On U.S. partnering efforts in Syria with the SDF, see the various U.S. inspector general reports, such as Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, Operation Inherent Resolve and Other Overseas Contingency Operations, U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of Defense, and U.S. Agency for International Development, October 1, 2018-December 31, 2018; John Walcott, “Trump ends CIA arms support for anti-Assad Syria rebels: U.S. officials,” Reuters, July 19, 2017.

[63] Jeremy Shapiro, The Terrorist’s Dilemma: Managing Violent Covert Organizations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 1-25; Weinstein.

[64] On the challenges in Syria, see, for example, Lister, “Assad Hasn’t Won Anything.”

[68] World Bank Governance Indicators data set, 2019. Available at: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#reports. On the definitions of these categories, see Daniel Kaufman, Aart Kray, and Massimo Mastruzzi, The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues (Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, September 2010).

[69] On the Islamic State’s desert strategy, see Michael Knights, “The Islamic State Inside Iraq: Losing Power or Preserving Strength?” CTC Sentinel 11:11 (2018): pp. 1-10; Hassan Hassan, “Insurgents Again: The Islamic State’s Calculated Reversion to Attrition in the Syria-Iraq Border Region and Beyond,” CTC Sentinel 10:11 (2017): pp. 1-8.

[70] Author interview, senior Jordanian and U.S. officials, July 2019.

[71] Author interview, senior Jordanian and U.S. officials, July 2019; Operation Inherent Resolve: Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, April 1, 2019-June 30, 2019, U.S. Department of Defense, 2019, p. 20; Hassan Hassan, “A Hollow Victory over the Islamic State in Syria? The High Risk of Jihadi Revival in Deir ez-Zor’s Euphrates River Valley,” CTC Sentinel 12:2 (2019): pp. 1-6.

[72] “The Temporary Fall of Cities as a Working Method for the Mujahideen,” Al Naba, April 2019. Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi translated the articles into English and published them. See, for example, Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Islamic State Insurgent Tactics: Translation and Analysis,” aymennjawad.org, April 26, 2019.

[73] Mao Tse-Tung, On Guerrilla Warfare (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000); Ernesto “Che” Guevara, Guerrilla Warfare (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998).

[75] Operation Inherent Resolve: Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, April 1, 2019-June 30, 2019, p. 15; “Twenty-Fourth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” p. 20.

[76] Author interview, senior U.S. and Jordanian officials, July 2019; “UNHCR Update on Syria,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, April 30-May 6, 2019; Operation Inherent Resolve: Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress, April 1, 2019-June 30, 2019, p. 8.

[78] Ibid., p. 8.

[79] “Twenty-Fourth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” p. 17.

[80] Ibid., p. 7.

[81] Author interview, senior U.S. and Jordanian officials, July 2019. On HTS relations with al-Qa`ida, see Seth G. Jones, “Al-Qaeda’s Quagmire in Syria,” Survival 60:5 (2018): pp. 181-198; Charles Lister, “How al-Qa’ida Lost Control of its Syrian Affiliate: The Inside Story,” CTC Sentinel 11:2 (2018): pp. 1-9.

[82] “Twenty-Fourth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” p. 8.

[83] Data is from the Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. An earlier iteration of this map was previously published in Seth G. Jones, Nicholas Harrington, and Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., Dangerous Liaisons: Russian Cooperation with Iran in Syria (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2019); Seth G. Jones, War By Proxy: Iran’s Growing Footprint in the Middle East (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 2019); Seth G. Jones and Maxwell B. Markusen, The Escalating Conflict with Hezbollah in Syria (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2018).

[84] On Israeli strikes in Syria, see the analysis using satellite imagery and other data in Jones, Harrington, and Bermudez, Jr.; Jones, War By Proxy; and Jones and Markusen.

[85] Yaniv Kubovich, “Israel Launched World’s First Air Strike Using F-35 Stealth Fighters, Air Force Chief Says,” Haaretz, May 24, 2018.

[86] “Iraq Accuses Israel of String of Attacks on Paramilitary Bases,” Times of Israel, August 29, 2019; Amos Yadlin and Ari Heistein, “Is Iraq the New Front Line in Israel’s Conflict with Iran?” Foreign Policy, August 27, 2019.

[87] See Colin Powell’s comments at the Aspen Institute’s “Aspen Ideas Festival” in 2007 at “Colin Powell on the Decision to Go to War,” Atlantic, October 2007.

[88] See the discussion in William Safire, “If You Break It…,” New York Times, October 17, 2004.

Skip to content

Skip to content