Abstract: In addition to losing control of Iraqi cities and oilfields, the Islamic State has clearly lost much of the capability it developed within Iraq from 2011-2014. Quantitative attack metrics paint a picture of an insurgent movement that has been ripped down to its roots, but qualitative and district-level analysis suggests the Islamic State is enthusiastically embracing the challenge of starting over within a more concentrated area of northern Iraq. The Iraqi government is arguably not adapting fast enough to the demands of counterinsurgency, suggesting the need for intensified and accelerated support from the U.S.-led coalition in order to prevent the Islamic State from mounting another successful recovery.

It has been a year since Iraq’s (then) Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi declared victory over the Islamic State on December 9, 2017.1 Yet the Islamic State did not disappear in Iraq. According to the author’s attack dataset,a in the first 10 months of 2018, the movement mounted 1,271 attacks (of which 762 were explosive events,b including 135 attempted mass-casualty attacksc and 270 effectived roadside bombings). As important, the Islamic State attempted to overrune 120 Iraqi security force checkpoints or outposts and executed 148 precise killings of specifically targeted individualsf such as village mukhtars, tribal heads, district council members, or security force leaders.

In an August 2017 CTC Sentinel review of the Islamic State’s transition to insurgency in Iraq,2 this author noted an almost automatic shift back to insurgent tactics in areas where the movement lost control of terrain in 2014-2017.3 As Hassan Hassan convincingly documented in his December 2017 study for this publication,4 as early as the summer of 2016, the Islamic State had readied “a calculated strategy by the group after the fall of Mosul to conserve manpower and pivot away from holding territory to pursuing an all-out insurgency.”5 In another September 2018 study,6 Hassan reiterated that the Islamic State sums up its strategy using three Arabic phrases: sahraa, or desert; sahwat, or Sunni opponents; and sawlat, or hit-and-run operations.7 Based on the precepts of the Islamic State’s own 2009 lessons-learned analysis—“Strategic Plan to Improve the Political Standing of the Islamic State of Iraq”—the plan is to return to the attritional struggle against the Iraqi state and Sunni communities that was executed so successfully by the Islamic State in 2011-2014.8

Metrics-Based Analysis of Islamic State in Iraq Attacks

So how is the plan working out thus far? This article is an update and an extension of the author’s aforementioned August 2017 metrics analysis of known Islamic State operations in Iraq. The objective of the research is to track how the Islamic State is performing as an insurgent movement in a variety of Iraqi provinces. One output of the research is the benchmarking of current Islamic State operational activity against the metrics of 2017 and the years prior to the movement’s 2014 seizure of territory. In August 2017, the author analyzed Islamic State attack metrics in liberated areas in Diyala, Baghdad’s rural “belts,”g Salah al-Din, and Anbar. This new analysis will return to the above provinces (including a fully liberated Anbar) and also consider the newly liberated provinces of Nineveh and Kirkuk.

To achieve this, the author has updated his dataset of Iraq attack metrics up to the end of October 2018. The dataset includes non-duplicative inputs from open source reporting, diplomatic security data, private security company incident data, Iraqi incident data, and U.S. government inputs. The dataset was scoured manually, including individual consideration of every Significant Action (SIGACT) in the set, with the intention of filtering out incidents that are probably not related to Islamic State activity. This process includes expansive weeding-out of “legacy IED” incidents (caused by explosive remnants of war) and exclusion of likely factional and criminal incidents, including most incidents in Baghdad city. The author adopted the same conservative standard as was used in prior attack metric studies9 to produce comparable results. As a result, readers should note that the presented attack numbers are not only a partial sample of Islamic State attacks (because some incidents are not reported) but are also a conservative underestimate of Islamic State incidents (because some urban criminal activity may, in fact, be Islamic State racketeering).

In the August 2017 CTC analysis of Iraq attack metrics, the author suggestedh that analysts should focus more attention on the qualitative aspects of Islamic State attacks (such as targeted assassinations) to create a richer assessment of the significance of lower-visibility events. In this study, the author takes his own advice and not only breaks down incidents into explosive or non-explosive events, but also created four categories of high-quality attacks (the aforementioned mass-casualty attacks, effective roadside bombings, overrun attacks, and person-specific targeted attacks10). Though still highly subjective, the above filtering and categorizing of SIGACTs results in a more precise sample of Islamic State activity from which to derive trends. Immersion in manually coding the detail of thousands of geospatially mapped SIGACTs creates vital opportunities for pattern recognition and relation of trends to key geographies.

National-Level Indicators of Islamic State Potency

There can be no doubt that the Islamic State remains a highly active and aggressive insurgent movement. By the author’s count, supported by “heat map” style visualization of Islamic State activity and historic operating patterns, the group maintains permanently operating attack cells in at least 27 areasi within Iraq. As a movement, it generated an average of 13.5 attempted mass-casualty attacks per month within Iraq in the first 10 months of 2018, as well as 27.0 effective IEDs per month, 14.8 targeted assassination attempts per month, and 12.0 attempted overruns of Iraqi security force checkpoints or positions per month.11 At the very least, the Islamic State remains active, trains its fighters in real-world operations, and does not allow the security environment to normalize.

All this being said, the Islamic State appears to be currently functioning at its lowest operational tempo (at the national aggregate level) since its nadir in late 2010. In 2018, combined totals of Islamic State attack metrics for six provinces (Anbar, Baghdad belts, Salah al-Din, Diyala, Nineveh, and Kirkuk) averaged 127.1 per month.12 In comparison, during 2017 combined totals of Islamic State attack metrics for just four provinces (Anbar, Baghdad belts, Salah al-Din, and Diyala) averaged 490.6 per month.13 This suggests the Islamic State attacks in 2018 averaged less than a third of their 2017 monthly totals, a huge reduction in operational tempo within Iraq. The 2018 monthly average of 127.1 attacks is also much lower than the six province averages (Anbar, Baghdad belts, Salah al-Din, Diyala, Nineveh, and Kirkuk) from 2013 (518 incidents per month), 2012 (320 incidents per month), and 2011 (317 incidents per month).14 Though SIGACT reporting could have declined somewhat since 2017, there are no indications of a blackout of reporting that would create a two-thirds reduction in reported incidents. To the contrary, ever-improving social media reporting by security force members and SIGACT or martyrdom aggregators has arguably led to a slight improvement in visibility.15

Assuming that greatly reduced attack metrics reflects reality, analysts are faced with a very consequential and tricky exam question: Is the Islamic State unable to mount more attacks in Iraq, or is it marshaling its remaining strength and striking more selectively? If the former, the drop in attack metrics might suggest that Islamic State attempts to hold terrain on multiple fronts in Iraq and Syria resulted in such heavy losses to leadership, personnel, and revenue generation that the Islamic State has emerged more damaged than it was after the Sahwa (Awakening) and the U.S. “Surge.”16

However, this does not satisfyingly explain how a fairly high number of attacks could continue in late 2017, only dropping off from the second quarter of 2018 onwards. (Overall attacks dropped by 19% between the first and third quarters of 2018, with “high-quality attacks” (mass casualty, overruns, effective roadside bombs, and targeted killings) dropping by 48% in the same comparison.)17 One explanation that might be consistent with Hassan’s description of the Islamic State’s “calculated strategy by the group after the fall of Mosul to conserve manpower”18 is that the group is focusing its efforts on a smaller set of geographies and a “quality over quantity” approach to operations. A tour around the six main provinces with a strong Islamic State presence provides a set of case studies to test the explanations of reduced Islamic State operational tempo.

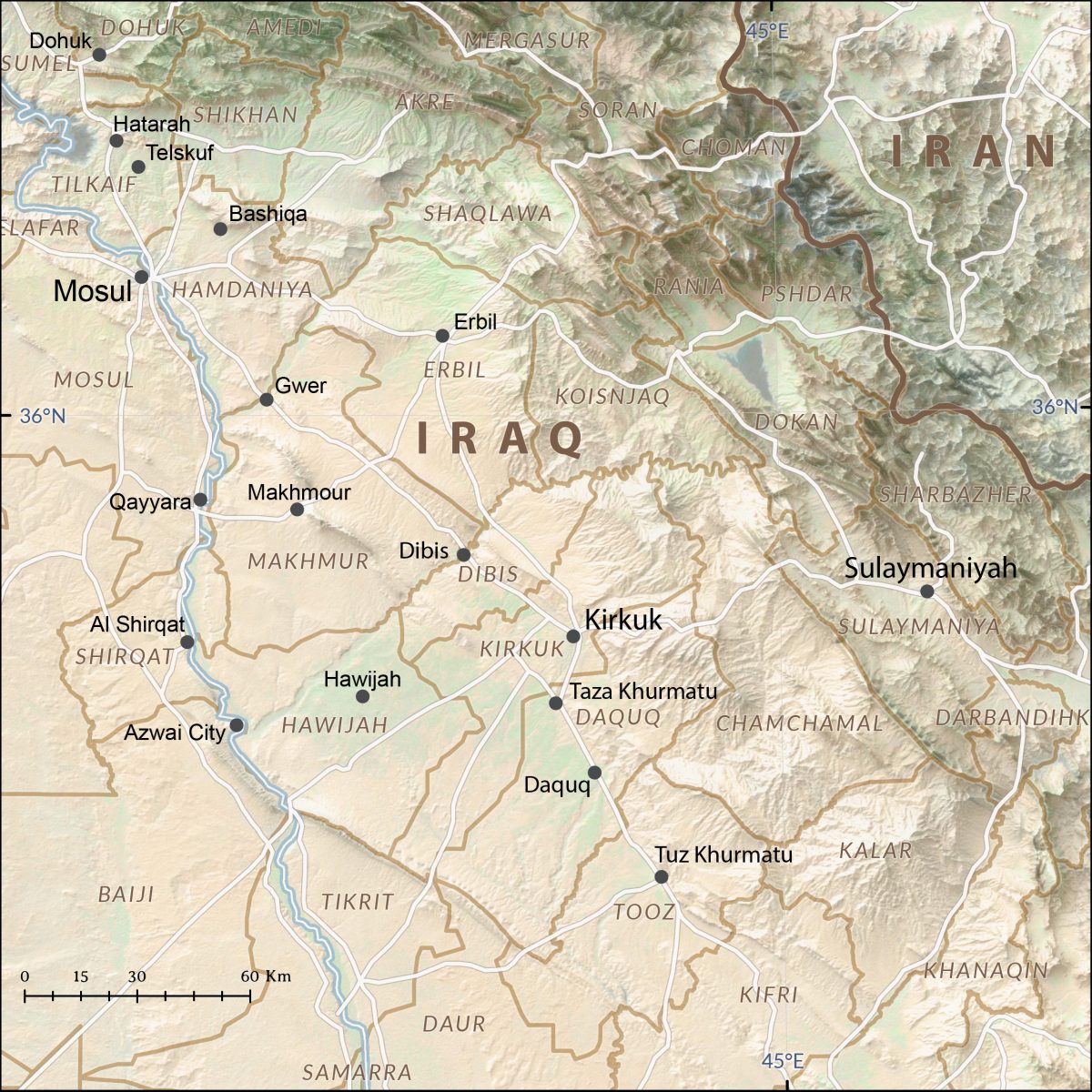

Northeastern Iraq (Rowan Technology)

Weak Insurgencies in Anbar and Salah al-Din

The author’s August 2017 CTC Sentinel article noted that Anbar and Salah al-Din were the scene of weak insurgencies in 2017 that were characterized predominately by low-quality harassment attacks, such as mortar or rocket attacks or victim-operated IEDs not focused on specific targets.19 Attacks metrics from 2018 suggest that the Islamic State is still not generating powerful campaigns of attacks in these provinces and has even weakened in both areas.

In predominately Sunni Anbar, the Islamic State averaged just 9.1 attacks per month in 2018, versus 60.6 attacks per month in 2017 (when Al-Qaim district was excluded from statistics as it was still under the Islamic State) or versus 66.0 attacks per month in 2013 (counting attacks in all of Anbar).20 Forty-nine percent of attacks in 2018 were “high-quality” types, an increase against the 30% of high-quality attacks in 2017.21 Nevertheless, the small scale of the insurgency’s attack activities in Anbar means that better quality attacks were limited to an average each month of one overrun of an outpost plus one targeted killing and a pair of effective IEDs.22 Almost no tribal or local community leaders were killed in Anbar (four in 10 months in 2018), and only three mass-casualty attacks were attempted.23 These are very low figures, both historically and considering that Anbar is Iraq’s largest province, perhaps pointing to a de-prioritization of Anbar by the Islamic State as an attack location at this stage of the war. As in 2017, there is very little evidence of attack activity in Anbar cities like Ramadi and Fallujah.24

Salah al-Din also saw a steep year-on-year reduction in attacks, with a monthly average of 14.2 in 2018 versus 84.0 in 2017.25 (The 2018 average for Salah al-Din is just below the 19.0 and 15.0 per month averages for the province in 2012 and 2011, respectively.26) Sixty percent of attacks in 2018 were ‘high-quality’ types, an increase against the 42% of high-quality attacks in 2017.27 Again, due to the small overall scale of the local insurgency, the raw numbers of quality attacks were low: just six targeted killings in 10 months, an average of 2.1 overrun attacks on outposts each month and 3.6 effective roadside IEDs per month.28 For a province that contains Iraq’s north-south military supply corridor, the scene of an average of 90 roadside bombings per month during the U.S. military presence, current Islamic State attack activities in Salah al-Din stand out as anemic. With the exception of the ruined refinery town of Baiji and the adjacent Sharqat, the Islamic State is only slowly starting to attack Salah al-Din cities like Samarra, Tikrit, Dour, Balad, and Tuz Khurmatu.29

Islamic State inactivity in Anbar could be explained by a number of factors, including the temporary disruptive effect of the full recapture of the province in late 2018, but it is harder to rationalize why Salah al-Din has become even quieter than during 2017. Perhaps the Islamic State invested its resources elsewhere due to overwhelming pressure from ‘outsider’ (mainly Shi`a) Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) working closely with predominately Sunni, locally recruited PMF brigades 51 and 88.30 In 2017, this author assessed that predominately Sunni Anbar and the predominately Sunni parts of Salah al-Din might resist a strong resurgence of the Islamic State if they became a “partnership zone” where Sunnis felt demographically secure and Sunni communities actively partnered with the Iraqi security forces.31 A key question for analysts is whether depressed Islamic State attacks in Salah al-Din mark the success of an unlikely partnership between Shi`a PMF factions and Sunni tribes, and, if so, whether such arrangements are sustainable.

Islamic State Setbacks in the Baghdad Belts

The author’s August 2017 CTC Sentinel article sounded a note of alarm about large numbers of Islamic State IED attacks on markets and shops in Baghdad’s rural belts and outer urban sprawl.32 This trend continued throughout the first quarter of 2018, when there were 65 attempted mass-casualty incidents in the Baghdad belts or projected into Baghdad via the rural districts.33 Thereafter, the bombings dropped off sharply, with just 16 in the second quarter and 15 in the third.34 Overall, attacks in 2018 dropped to an average of 29.3 per month versus 67.3 in 2017 and 60.0 in 2013, dropping to about the 2011 average of 35.0 attacks per month.35 Confirming the anecdotal impression of many Baghdad residents and visitors, in the years since 2003, Baghdad has never witnessed fewer reported salafi jihadi terrorist attacks than it did in 2018.j Total attacks halved from an average of 45.3 per month in the first quarter of 2018 to 20.3 in the third quarter, with quality attacks dropping from 65% of all attacks in the first quarter to 46% of all attacks in the third.36 The monthly average of 3.6 effective roadside IED attacks in 2018 is still remarkably low for an area of Baghdad’s size, with such a concentration of security force patrols.37 (The comparative figure in 2013 was 23.0 effective roadside bombs per month.38) Though some of the 2.3 monthly assassinations in the Baghdad belt include political figures, the area has witnessed almost no reported targeted assassinations of local Sunni leaders in 2018, in stark contrast to other areas like Kirkuk and Nineveh.39

A likely factor in the reduction of Islamic State attacks in Baghdad is the disruptive counterinsurgency operations and perimeter security improvements40 launched by the Baghdad Operations Command, in cooperation with neighboring commands and with intense intelligence support from the coalition.41 These have been focused on the northern and southern belts, which are the most intensely attacked. The northern arc, including hotspots like Tarmiyah, Rashidiyah, and Taji, witnessed 9.7 attacks each month on average in 2018 (i.e., more than Iraq’s largest province, Anbar), including 72% quality attacks.42 The southern belt, centered on the former insurgent stronghold of Jurf as-Sakr and adjacent Latifiyah and Iskandariyah, suffered an average of 8.3 attacks per month in 2018 (almost equaling the whole of Anbar), but a lower proportion (56%) of quality attacks.43 The western and eastern belts witnessed exactly the same average in 2018—5.7 attacks per month, half of which were high quality.44

Deadlock in Diyala

Diyala was the first place where the Islamic State mounted a strong insurgency after it moved to a terrain-holding model in 2014, and in some respects, this is because Diyala was never decisively overrun by the Islamic State in 2014 and thus the local militant cells never ceased being insurgents.45 In the author’s 2016 and 2017 analyses, Diyala and adjacent parts of Salah al-Din were identified as the most fertile ground, at the time, for an Islamic State sanctuary.46 Yet the 2018 attack metrics indicate that either the Islamic State shifted its weight elsewhere (i.e., to nearby rural Kirkuk and southern Nineveh) or the Islamic State has been fought to a standstill and reduced in capability within Diyala, perhaps temporarily.

As in Anbar, Salah al-Din, and the Baghdad belts, the raw numbers of reported Islamic State attacks in Diyala have greatly reduced in 2018, despite no concomitant loss of reporting or social media coverage of operations and casualties. The average number of Islamic State attacks in Diyala in 2018 was 26.2 per month, versus 79.6 per month in 2017 and 50.3 per month in 2013.47 The Islamic State’s war in Diyala is an interesting 50-50% weave of high-quality attacks and broader harassment of civilians. In 2018 in Diyala, there were 31 targeted killings48 of district council members, mukhtars (village headman), tribal leaders, and Sunni PMF commanders. Among the half of attacks in Diyala not categorized as high-quality was a preponderance of terrorization attacks on ‘enemy civilians’ (Shi`a or Sunni), including kidnap-murders, mortar attacks, destruction of rural farming infrastructure, and other efforts to overawe or displace potential civilian opponents.49 k

Diyala province, Iraq (Rowan Technology)

It may be that Islamic State brutality is driving predominately local Sunni tribes into partnership with Shi`a PMF and Iraqi military forces, though such tribes have to cooperate with PMF in order to be allowed to resettle in their towns in any case.50 In Diyala, as in Salah al-Din, there is a case for taking a closer look at whether PMF actors and allied Iraqi Army units are undertaking more effective operations and coordination with local Sunnis than expected, or whether a different causal factor has depressed Islamic States attacks in 2018 down to a third of the levels reported in 2017.51

Focus on Southern Nineveh

Nineveh was not included in the August 2017 CTC Sentinel article because it was only liberated as the analysis went to press. But now—15 months after the liberation of Mosul and 14 months after Tal Afar was recaptured—there is a sufficient dataset to compare to other provinces and to the pre-2014 Islamic State insurgency in Nineveh.

The Islamic State mounted an average of 17.1 attacks per month in Nineveh in the first 10 months of 2018.52 This is minuscule compared to the average of 278 attacks per month in 2013, the 77.0 per month in 2012, or the 60.3 per month in 2011.53 The key reason for the dramatic comparative reduction is the almost complete cessation of Islamic State attacks in Mosul city, which was always the engine room of insurgent attacks in Nineveh.54 At the nadir of Islamic State operations in 2010, the number of Mosul city attacks still averaged 56 per month.55 This increased to 218.5 average monthly attacks in 2013 and 347.0 monthly attacks in the first half of 2014.56 In comparison, Mosul city averaged 3.0 Islamic State attacks per month in 2018, a remarkably low level of activity in the largest Sunni-majority city in Iraq.57 Equally stunning is the manner in which Tal Afar—a long-time Islamic State base—now witnesses practically no visible insurgent activity at all,58 l denying the movement of its second historic hub in Nineveh.

The Islamic State has instead focused on rural insurgency in Nineveh in the year since it lost Mosul. Focus areas include the desert districts south of Mosul such as Qayyarah, Hatra, Ash Shura, the southwestern outer urban sprawl of Mosul city (Atshana, Sahaji, and Tall Zallat), and the desert located between the Baghdad-Mosul highway and the Iraq-Turkey Pipeline—the so-called “Jurn Corridor” (named after two notorious villages in the area).m Though small in scale at this point, the Islamic State rural insurgency is marked by the very high quality of the effort, with 62% of attacks in 2018 coded as quality attacks.59 In particular, 37 targeted assassinations of local leaders60 were undertaken in the first 10 months of 2018 within these various focus zones, which make up a 40 by 40-mile area, including 17 village mukhtars61 and the publicized beheading of a Tribal Resistance Force leader.n Twenty-eight attempted overrun attacks on Iraqi outposts were undertaken in the same area in 2018 as well as 32 effective roadside bombings of security force vehicles.62 At the time of writing in the last quarter of 2018, the Islamic State is beginning to employ heavily armed, technical-mounted raiding groups in southern Nineveh, akin to special forces, capable of out-gunning isolated outposts and making highways and village access roads too dangerous to use.63

Vehicles used for suicide car bombings, made by Islamic State militants, are seen at Federal Police Headquarters after being confiscated in Mosul, Iraq, on July 13, 2017. (Reuters/ Thaier Al-Sudani)

Kirkuk: The Strongest Wilayat

The Islamic State still physically controlled the rural Kirkuk farmbelts when the August 2017 study was written, but now—one year after Iraqi security forces reentered the area—attack data has accumulated to allow an early analysis of the insurgency in Kirkuk. The most obvious trend is that Kirkuk was the Islamic State’s most prolific attack location in Iraq in the first 10 months of 2018. Kirkuk saw an average of 33.0 attacks per month, versus 29.3 in Baghdad, 26.2 in Diyala, 17.1 in Nineveh, 14.2 in Salah al-Din, and 7.3 in Anbar.64 (In comparison, Kirkuk saw an average of 59 monthly attacks in 2013, 44 monthly attacks in 2012, and 26 monthly attacks in 2011.65) With 45 attacks in October 2018 and indications of higher levels in November,66 the Islamic State insurgency in Kirkuk has quickly rebooted to 2013 levels.

The strong insurgency was apparent from the very beginning of the year (first quarter average monthly attacks were 38.0),67 underlining the running start that the Islamic State achieved as soon as Iraqi forces entered Kirkuk. During the first 10 months of 2018, there were 85 effective roadside bomb attacks and 41 overruns on Iraqi outposts68—nearly doubling the numbers in adjacent Nineveh. In one notorious and widely publicized example in February 2018, Islamic State fighters dressed as PMF troops established a fake vehicle checkpoint at Shariah bridge, near Hawijah, and executed 27 PMF volunteers.69

As in Diyala and southern Nineveh, the Islamic State is also trying to make life as miserable and dangerous as possible for ‘enemy civilians’o and pro-government Sunni militias in rural Kirkuk. The Islamic State undertook 35 targeted assassinations of local leaders in the first 10 months of 2018,70 spread across the 80 by 40-mile Kirkuk farmbelts. As important, Islamic State fighters roam at will at night through the farms, killing farmers, burning houses and crops, destroying irrigation systems, and blowing up tractors and electrical towers.71 p The effort appears to be intended to drive pro-government tribal leaders out and to depopulate key areas where the Islamic State wants to increase its operational security and take over farming enterprises.q Christoph Reuter, a rare journalist to visit communities in the Kirkuk farmbelts, painted a vivid picture of the deadly dilemma facing civilians in a Der Spiegel Online report released in March 2018.72

Anecdotal reportingr from Iraqi military contacts, Iraqi civilian contacts, and journalists with local access to the Kirkuk farmbelts suggests that the predominately Shi`a Federal Police garrison of rural Kirkuk is failing to protect civilians. This is in part because the Islamic State is successfully intimidating the security forces to remain within their bases at night and to only operate en masse in large, easily avoided daytime clearance operations.73 Local Sunnis tend not to trust the Federal Police, who are largely recruited from the Shi`a populations in Baghdad, southern Iraq, and southern Salah al-Din.74 When Federal Police come to the aid of attacked villages, they are often too late to help civilians and then arrest or disarm the wrong people.75 Despite these failings, the heavy concentration of Federal Police brigades in Kirkuk may have complicated the operational environment for the Islamic State. In the first quarter of 2018, there were 39 average monthly attacks in Kirkuk (including 21 quality attacks), dropping to 30.6 attacks (including 15.3 quality) per month in the second quarter and 25.3 attacks (including 13.3 quality) per month in the third quarter.76

The question is whether this downturn is sustainable: there were 45 attacks in Kirkuk in October 2018, nearly double the monthly average of the third quarter.77 Similar steep month-on-month increases were also visible in Nineveh, Baghdad, and Anbar in October.78 s As weather and visibility deteriorate in Iraq during the winter months, Islamic State attacks tend to become more numerous and more ambitious, with the militants suffering less from aerial surveillance and airstrikes.79 Attack metrics are likely to rise in the final quarter of 2018, raising annual averages across the board.

Tactical Trends

Out of 1,271 Islamic State attacks in the first 10 months of 2018, 54% were quality attacks (mass casualty, overruns, effective roadside IEDs, or targeted killings), leaving 46% as less lethal or less carefully targeted harassment-type attacks.80 Thus, the movement still spends a good deal of its time mounting ineffective attacks for show, or to keep up momentum, or to practice skills and tactics.

The Islamic State is not running out of explosives yet. Fifty-nine percent of attacks were explosive events, with this 10-month average dropping to 48% in the third quarter.81 High-explosive main charges using military munitions are still widely available and turn up in large numbers in cleared caches.82 Islamic State cells spent considerable time creating and hiding high-explosive caches, yet military explosive use in IEDs has declined and homemade explosive production has increased across the different Islamic State cells in Iraq.83 This may suggest that insurgents cannot readily access their caches or cannot transport munitions, possibly due to patrols and checkpoints, and instead prefer to make new homemade explosives at their hide sites using readily available farming materials.

Suicide vests are found with great regularity,84 but suicide vest attacks are still rare (2.3 per month on average in the first 10 months of 2018 versus 10.3 per month in 2017).85 This suggests either a lack of suicide bombers or a deliberate withholding of the tactic and valuable suicide bombers. The Islamic State appears to make up for the small explosive yield of many attempted mass-casualty attacks by ‘boosting’ them in some manner: detonating at a gas station or in a less-secure crowded area such as a rural market or mechanic’s garage.86

Penetration of hardened facilities such as police stations or military headquarters is very rarely attempted at this stage of the Islamic State insurgency.87 Instead, the Islamic State seems to recognize the vulnerability of linear infrastructure like highways, electricity transmission lines, and pipelines.88 Fake vehicle checkpoints and roadside ambushes allow the Islamic State to be unpredictable and utilize mobility to reduce its casualties. Attacking roads provides a fruitful means of finance for the Islamic State via carjacking and boosting cargoes,89 t and has proved effective in terms of catching and killing what the Islamic State see as high-value targets such as militia commanders and tribal leaders while they are lightly protected.u

The nocturnal assassination of local community leaders has proved another extraordinarily effective tactic, killing one man in order to intimidate thousands. As in 2011-2014, murder remains the Islamic State’s most effective and efficient tactic, and it has focused its murder campaign like a laser on the terrain where it has consolidated its presence.90 In southern Nineveh, rural Kirkuk, and northern Diyala, there were 103 targeted assassinations in the first 10 months of 2018 (75% of all Islamic State assassinations during that period).91 Using a basic calculation of Islamic State attack locations in 2018, the movement concentrated 75% of its assassinations in an area representing 10% of the terrain it routinely operates within.v

The roadside IED is also making a comeback, though not yet in great numbers and rarely involving advanced devices attended by IED triggermen or media teams.92 Most explosive devices encountered thus far in 2018 are built around five-gallon jerry cans or cooking gas cylinders loaded with homemade explosive slurry.93 Most devices are victim-initiated via pressure plate triggers, though command wire is also found in many caches, suggesting the potential for command detonation.94 More advanced explosive designs and initiation methods may not be viewed as necessary due to the paucity of Iraqi route clearance efforts and the use of unarmored pick-ups and buses by many Iraqi forces.95 In every province, the Islamic State seems to retain some residual expertise in roadside bombing tactics. One widely distributed tactic is a ‘come-on’ wherein the militants draw in the security forces with an action (an attack on civilians or security forces, or even the theft of property and livestock), then initiate one or more follow-up roadside IED attacks and ambushes.96 w

Implications for Counterinsurgents

SIGACT metrics are only ever a partial sample, often representing a more complete sample of high-visibility types of attack behavior (like explosive events and high-quality attacks), while often representing a less complete sample of low-visibility attacks such as racketeering, kidnap and shooting, or indirect fire incidents in rural areas. Nevertheless, the basic trends observed in the author’s dataset give a strong indication of Islamic State retrenchment and rationalization of its insurgency in 2018. There were 490.6 Islamic State attacks per month in Iraq in 2017, counting only Anbar, Baghdad, Salah al-Din, and Diyala. In the first 10 months of 2018, now including Nineveh and Kirkuk as well, there were 127.1 attacks per month. The insurgency in 2018 was thus in these combined areas less than a third of the size it was previously in 2017. In certain areas—Anbar, Baghdad, and Salah al-Din—the insurgency seemed to stagnate, significantly deteriorate, or even be abandoned for the present. In Diyala, the Islamic State fought hard to survive. In Nineveh and Kirkuk, the post-liberation insurgency started strongly.

The exam question posed in this paper concerned whether the Islamic State is incapable of raising its operational tempo or has chosen to rationalize its operations, as Hassan’s observations of Islamic State communiques suggests.97 SIGACT metrics seem to support the theory mentioned earlier that the Islamic State is deliberately focusing its efforts on a smaller set of geographies and a “quality over quantity” approach to operations. The Islamic State seems to have denuded or failed to reinforce areas such as Anbar, the Baghdad belts, southern Salah al-Din, and southern Diyala, and has instead concentrated its operations in the best human and physical terrain it can defend: southern Nineveh, rural Kirkuk, and the Hamrin Mountains on the Diyala/Salah al-Din border. As this author noted in August 2017:

“The coalition [has] been clearing outward toward the north and the west, but in the coming year Iraq must turn inward to remove the internal ungoverned spaces in Hawijah, Hamrin, Jallam, Anbar, and eastern Diyala. This will mean learning how to rewire command and control of operations to allow the Iraqi security forces, PMF, Kurds, and [Combined Joint Task Force Operation Inherent Resolve] to work together in a shared battlespace.”98

This inward clearing of Iraq has begun, but with more determination than skill. The clash between Baghdad and the Kurds over the independence referendum and Kirkuk has been a damaging distraction since September 2017.99 Iraqi forces have complicated the Islamic State’s efforts at recovery and some progress has been made to draw Sunni militiamen into the security campaign.100 Now, there are strong arguments for more locally led and locally recruited forces to be developed, and full cooperation restored between all the anti-Islamic State factions.101 There may now be new openness by Diyala’s key Shi`a political bloc Badr toward the involvement of the U.S.-led coalition102 in areas previously off-limits due to the profusion of Iranian-leaning PMF units, including locations such as northern Diyala. Likewise, the counterinsurgency would be aided by the reintegration into the fight of Kurdish intelligence capabilities in Nineveh, Kirkuk, and Diyala.

Iraq also needs to reequip for counterinsurgency. Without increasing force protection capabilities (i.e., fortified bases, mine-resistant vehicles, route clearance, quick reaction forces, and intelligence), the Iraqi counterinsurgency force is far too vulnerable to patrol effectively in rural areas or maintain defensive outposts.x In areas like rural Kirkuk, southern Nineveh, Diyala, and even areas near Baghdad like Tarmiyah, the reality is that the Islamic State still rules the night, meaning that key parts of the country have only really been liberated for portions of each day.103 This places stress on the need for night-fighting capabilities and training. It may only be with these steps that key provinces like Diyala, Nineveh, and Kirkuk can begin to resemble a “partnership zone,”104 where Sunnis can attain command of local police and paramilitary forces, and where U.S.-supported Iraqi forces have the resilience and back-up to disrupt Islamic State insurgents.

Though the Islamic State has gone ‘back to the desert’ (or at least rural strongholds), this is not out of choice but rather because cities such as Mosul, Ramadi, Fallujah, and Tikrit—all ruinously affected by the Islamic State—are currently inhospitable operating locations for the movement. In 2008, Islamic State of Iraq Emir Abu Omar al-Baghdadi succinctly noted, “We now have no place where we could stand for a quarter of an hour.”105 This is true once again in urban areas, but the Islamic State can now stand for much longer than that in rural areas, especially at night, and indeed held four hamlets near Tall Abtah (in south Nineveh) for a whole night on November 19-20, 2018.106 Yet while the Islamic State needs rural sanctuaries, such areas may not satisfy the movement for long. An exclusively rural insurgent movement in Iraq risks fading into irrelevance and losing support. The Islamic State is likely to seek to return to regular high-profile bombings in locations that have international prominence, most obviously Baghdad, quite probably via the relatively unprotected eastern flank of the city and its adjacent Shi`a neighborhoods.

Being out of the cities also means being poor or having to work much harder to make money. As RAND’s 2016 study of Islamic State finances noted,107 rural areas such as Diyala and Kirkuk were among the poorest income generators for the movement, requiring an external cash cow (principally Mosul city) to generate economic surpluses that might be spent in cash-poor wilayat. Today, there is no urban cash cow. This may drive the Islamic State to try to quietly return to Mafiosi-type protection rackets in the cities and towns108 and/or to focus a greater proportion of its operational activity on rural money-making ventures. Identifying the Islamic State’s ’soft reentry’ into cities is a priority intelligence requirement but a difficult challenge. In this vein, it may be worth looking at the metrics for Islamic State attacks on markets and garages with a critical eye, as these may partially represent protection racketeering or might evolve into such schemes, particularly in the Baghdad belts.y Outside the cities, the Islamic State may turn to traditional ventures such as encouraging and taxing trade flows and running trucking ventures, as opposed to the practice seen in 2017 and 2018 of killing truckers on the Baghdad-Kirkuk road109 and thus depressing trade. New money-making ventures may also emerge: commandeering larger agricultural ventures in Diyala and Kirkuk, for instance.

In the longer-term, the Islamic State’s expansion back toward a terrain-holding force may not be the movement’s preference and is restrained by the absence of a number of drivers that aided its rise in 2011-2014 but which are presently lacking. First, the Syrian civil war gave the Islamic State an expanding sanctuary and access to military equipment, high explosives, manpower, and finances.110 Today, the Islamic State is under severe pressure in Syria and has lost most of its territory.111 Second, the Iraqi security forces were decimated by corruption and poor leadership in 2011-2014, while today they are well-led and recovering their capabilities, even factoring in the strain of continuous operations year after year.112 Third, U.S. forces were absent from Iraq from November 2011 to August 2014, whereas today the partner nations of Combined Joint Task Force Operation Inherent Resolve continue to pursue the enduring defeat of the Islamic State,113 and the coalition continues to enjoy the consent of the Iraqi government to operate on Iraqi soil. If any of these three factors change, however, the long-term outlook for the Islamic State in Iraq might brighten considerably, making them key strategic signposts to watch. CTC

Dr. Michael Knights is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He has worked in all of Iraq’s provinces, including periods embedded with the Iraqi security forces. Dr. Knights has briefed U.S. officials and outbound military units on the resurgence of al-Qa`ida in Iraq since 2012 and regularly visits Iraq. He has written on militancy in Iraq for the CTC Sentinel since 2008. Follow @mikeknightsiraq

Substantive Notes

[a] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset. The dataset brings together declassified coalition SIGACT data plus private security company and open-source SIGACT data used to supplement and extend the dataset as coalition incident collection degraded in 2009-2011 and was absent in 2012-2014. New data since 2014 has been added to the dataset to bring it up to date (as of the end of October 2018).

[b] Explosive events include SIGACT categories such as Improvised Explosive Device (IED), Under-Vehicle IED (UVIED), vehicle-carried or concealed IEDs, all categories of suicide bombing, indirect fire, hand grenade and rocket-propelled grenade attacks, guided missile attacks, plus recoilless rifle and improvised rockets.

[c] Defined in the author’s dataset as IED attacks on static locations that are assessed as being intended to cause multiple civilian or security force casualties.

[d] Defined in the author’s dataset as IED attacks on vehicles that are assessed to have struck the specific type of target preferred by the attacker, and to have initiated effectively.

[e] Defined in the author’s dataset as attacks that successfully seized an Iraqi security force location for a temporary period, or which killed or wounded the majority of the personnel likely to have been present at the site.

[f] Inferred in the author’s dataset by connecting the target type with circumstantial details of the attack to eliminate the likelihood that the individual was not the intended victim of the attack.

[g] The rural districts bordering Baghdad but not within the city limits (amanat) include places like Taji, Mushahada, Tarimiyah, Husseiniyah, Rashidiyah, Nahrawan, Salman Pak, Suwayrah, Arab Jabour, Yusufiyah, Latifiyah, Iskandariyah, and Abu Ghraib.

[h] The author noted that “analysts of insurgency in Iraq should … look beyond quantitative trends to spot qualitative shifts that may be of far greater consequence” such as “high-impact, low-visibility violence.” The author underlined the disproportionate value of “rich on-the-ground data that allows analysts to understand whether a shooting is a criminal drive-by versus a carefully planned intimidation attack on a key sheikh, for example.” See Michael Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” CTC Sentinel 10:7 (2017), p. 21.

[i] In the author’s view, these are in the following areas: Al-Qaim, Wadi Horan/Rutbah and Lake Tharthar/Hit/Ramadi in Anbar province; the southern Jallam Desert (southern of Samarra), Baiji, Sharqat, Pulkhana (near Tuz), and Mutabijah/Udaim in Salah al-Din province; Tarmiyah, Taji, Rashidiyah, Jurf as-Sakr/Latifiyah/Yusufiyah, Jisr Diyala/Madain, and Radwaniyah/Abu Ghraib in the Baghdad belts; Hawijah, Rashad, Zab, Dibis, Makhmour, and Ghaeda in or near Kirkuk province; Muqdadiyah, Jawlawla/Saadiyah/Qara Tapa, and Mandali in Diyala; and Mosul city, Qayyarah, Hatra, and the Iraq-Turkey Pipeline corridor southwest of Mosul, Badush, and Sinjar/Syrian border in Nineveh.

[j] The 2013 monthly average of 60 Islamic State attacks per month was the lowest recorded aggregate of Baghdad attacks prior to 2018. In 2011, as the insurgency reached its nadir, the monthly average was still 101. In 2006, the worst year of the war, Baghdad attacks regularly topped 1,500 per month. All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[k] A close reading of all the 262 Islamic State attacks in Diyala in 2018 paints a vivid picture of no-holds-barred warfare between the Islamic State and all other actors. Even filtering out likely Sunni-on-Sunni and Sunni-Shi`a tribal incidents, there are regular murders of shepherds and farmers on agricultural land, booby-trapping of farm roads and canal crossings, mortar attacks on farms, destruction of irrigation and power lines, plus the assassination of local leaders. All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[l] There were 0.3 Islamic State attacks in Tal Afar per month on average in the first 10 months of 2018: two roadside IEDs and one attempted suicide vest attack on a Shi`a procession.

[m] The author worked episodically in Nineveh during 2006-2012, during which time the villages of the Jurn corridor were viewed by U.S. and Iraqi forces as notorious al-Qa`ida in Iraq and Islamic State of Iraq launchpads. The villages—Jurn 1 and 2—are located 15 miles southwest of Mosul city and just five miles west of the highway.

[n] On March 20, 2018, the Islamic State undertook a surge of targeted killings in Mosul city, killing four mukhtars and kidnapping and beheading pro-government Sunni militia leader Udwan Adnan Muhammad in the Rajim al-Hadid area in western Mosul. All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[o] The author refers here to tribes that the Islamic State views as enemies, either due to their sector (in the case of Sunnis) or their opposition to the Islamic State.

[p] Attacks on electrical towers have been prolific in 2018, and seemingly largely to discomfort locals as opposed to theft of copper wiring (as most images show lines left in place). For an open-source reference, see Mohammed Ebraheem, “Iraq’s Hawija turns dark as Islamic State continues to target electricity pylons,” Iraqi News, October 1, 2018.

[q] These kinds of incidents are thickly strewn throughout the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset. Sunni villages are being evacuated as close as 10 miles from urban Kirkuk due to repeated intimidation attacks. For an open-source reference, see “Residents Of A Village In Hawija Displaced Due To Threats Received From Daesh,” National Iraqi News Agency, August 9, 2018.

[r] The author regularly pre-briefs journalists moving through Iraq, and then debriefs them afterwards. This generates rich detailed reporting that often fails to make it into news coverage of Iraq because it is considered by editors to be too niche for the general reader to appreciate.

[s] In Nineveh, attacks jumped from 21 in September 2018 to 30 in October 2018. Baghdad attacks increased from 20 in September to 35 in October. Anbar saw a month-on-month increase from three attacks in September to 10 in October.

[t] The seizure of trucks and their cargo appears to be a key source of gaining access to money (threat finance). East of Tuz Khurmatu, for instance, truckers were repeatedly stopped, killed, and buried in mass graves before the disappearances were recognized as a trend. For an open-source reference, see “Mass grave containing the remains of 20 truckers discovered,” Baghdad Today, February 7, 2018.

[u] One example of this is Highway 82, which links Diyala’s governorate center at Baquba to the Mandali district on the Iran-Iraq border. Among seven attacks on the road in the first 10 months of 2018, three targeted high-value targets such as tribal leaders and Iraqi MPs. All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[v] The author used heat-mapping of SIGACTs and then made a rough square mile calculation: 75% of assassinations happened in a 6,640 square mile area, while all Islamic State attacks were spread out across a 60,636 square mile area in Iraq in 2018.

[w] In all the provinces covered in this study, the Islamic State mounted occasional ‘double tap’ IED attacks (one initial attack, plus a follow-up on first responders and security reinforcements), and in Kirkuk and Nineveh, there were even some ‘triple tap’ attacks with multiple layers of follow-on attacks.

[x] These impressions were formed from a synthesis of the author’s dataset and review of many hundreds of images of ISF, PMF, and Kurdish troops moving and operating.

[y] Kidnap for ransom is a phenomenon that analysts need to monitor and where intelligence collection needs to differentiate pure criminal activity from Islamic State fundraising. However, kidnap for ransom is risky and manpower-intensive. It is useful for small groups in chaotic environments, but it cannot fund major insurgent groups or replace the rent that can be drawn from urban intimidation or road taxation networks.

Citations

[1] Margaret Coker and Falih Hassan, “Iraq Prime Minister Declares Victory Over ISIS,” New York Times, December 9, 2017.

[2] See Michael Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” CTC Sentinel 10:7 (2017).

[3] Ibid. See also Michael Knights and Alexander Mello, “Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala: How the Islamic State Could Exploit Iraq’s Sectarian Tinderbox,” CTC Sentinel 9:10 (2016).

[4] See the excellent piece: Hassan Hassan, “Insurgents Again: The Islamic State’s Calculated Reversion to Attrition in the Syria-Iraq Border Region and Beyond,” CTC Sentinel 10:11 (2017).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., p. 1.

[7] Ibid., p. 2.

[8] Ibid., pp. 4-6.

[9] See Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” and Knights and Mello, “Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala.”

[10] See footnotes c-f.

[11] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] For an example of a very capable SIGACT and martyrdom aggregator, see the Twitter account @TomtheBasedCat

[16] On the Sahwa and “Surge” phenomena, see Stephen Biddle, Jeffrey Friedman, and Jacob Shapiro, “Testing the Surge – Why Did Violence Decline in Iraq in 2007?” International Security 37:1 (2012): pp. 7-40. See also Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Assessing the Surge in Iraq,” Middle East Review of International Affairs (MERIA) Journal 15:4 (2011): pp. 1-14, and Ed Judd, “Counterinsurgency efforts in Iraq and the wider causes of pacification,” Australian Defence Force Journal 185 (2011): pp. 5-14.

[17] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[18] Hassan, p. 1.

[19] See Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” p. 17.

[20] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] For a breakdown of Sunni PMF units, see “Iraqi Security Forces and Popular Mobilization Forces: Order of Battle,” Institute for the Study of War, December 2017, p. 46.

[31] See Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” p. 17.

[32] Ibid., p. 20.

[33] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] For a description of Baghdad’s perimeter security requirements, see Sajad Jiyad and Michael Knights, “How to prevent sectarian backlash from Baghdad bombings,” Al Jazeera English, May 26, 2017.

[41] Based on the author’s conversations with U.S. intelligence officers working on Iraq, second and third quarters of 2018. Names and places of interviews withheld at request of interviewees.

[42] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] The 2014-2016 history of the insurgency in Diyala is described in detail in Knights and Mello, “Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala.”

[46] See Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” and Knights and Mello, “Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala.”

[47] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Knights and Mello, “Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala,” p. 6.

[51] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] See the author’s urban Mosul SIGACT coding in Michael Knights, “How to Secure Mosul: Lessons from 2008—2014,” Research Note 38 (2016): p. 10.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid.

[69] For an open-source reference, see “27 Hashd killed after clashes with ISIS in Hawija pocket,” Rudaw, February 19, 2018.

[70] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[71] Ibid.

[72] This report is well worth reading. See Christoph Reuter, “The Ghosts of Islamic State: ‘Liberated’ Areas of Iraq Still Terrorized by Violence,” Der Spiegel Online, March 21, 2018.

[73] Author’s interviews, multiple journalists and Kirkuk residents, first and second questions of 2018. Names and places of interviews withheld at request of interviewees.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset. The author is indebted to Iraq security expert Alex Mello for cleverly matching the sharp (but temporary) month-on-month declines with the arrival of each tranche of Federal Police reinforcements to rural Kirkuk.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Ibid.

[79] See Peter Schwartzenstein’s excellent report on the Islamic State’s use of weather: “‘ISIS Weather’ Brings Battles and Bloodshed in Iraq,” Outside, October 6, 2016.

[80] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Ibid. The author’s dataset includes large numbers of described cache contents.

[83] Based on the author’s conversations with U.S. intelligence officers working on Iraq, second and third quarters of 2018. Names and places of interviews withheld at request of interviewees. Almost every cache is reported as including one or more suicide vest, suggesting they were provided to most fighters for potential use during operations or to avoid capture.

[84] The author’s dataset includes huge numbers of described cache contents.

[85] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[86] Ibid. Qualitative observations drawn from the dataset.

[87] Ibid. Qualitative observations drawn from the dataset. In Anbar, for instance, there were only two known efforts by suicide vest attackers to penetrate guarded government buildings in the first 10 months of 2018, one of which was a hospital.

[88] Ibid. Qualitative observations drawn from the dataset.

[89] Ibid. Qualitative observations drawn from the dataset.

[90] This is a theme the author has stressed since 2012. See Michael Knights, “Blind in Baghdad,” Foreign Policy, July 5, 2012. See also Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” p. 21.

[91] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[92] Ibid. Qualitative observations drawn from the dataset. Almost all IED descriptions and finds describe fairly standard pressure-plate initiated devices. No references have been found to radio control arming or firing switches, passive-infrared triggers, or triggermen caught during IED incidents. This suggests to the author that the Islamic State today favors simplified IED tactics, perhaps a result of having moved to a more standardized, less inventive model of mass IED emplacement from 2014-2017.

[93] Based on the author’s conversations with U.S. intelligence officers working on Iraq, second and third quarters of 2018. Names and places of interviews withheld at request of interviewees. Almost every cache is reported as including multiple five-gallon (20-liter) jerry cans, plastic jugs, gas cylinders, or fire extinguishers.

[94] Ibid. Drawn from conversations with U.S. intelligence officers and observation of the dataset. The author wishes to thank Iraq security expert Alex Mello for pointing to the presence of command wire in many caches.

[95] Ibid. Drawn from conversations with U.S. intelligence officers and observation of the dataset.

[96] Ibid. Qualitative observations drawn from the dataset.

[97] Hassan, p. 1.

[98] Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” p. 20.

[99] For an open-source reference, see Maher Chmaytelli and Raya Jalabi, “Iraqi forces complete Kirkuk province takeover after clashes with Kurds,” Reuters, October 20, 2017.

[100] For a discussion of Sunni PMF units, see “PMF Order of Battle,” Institute for the Study of War, 2018, p. 46.

[101] For very specific recommendations on the evolution of CJTF-OIR security cooperation with Iraq, see Michael Knights, “The ‘End of the Beginning’: The Stabilization of Mosul and Future U.S. Strategic Objectives in Iraq,” Testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, February 28, 2017, and Michael Knights, “The Future of Iraq’s Armed Forces,” Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies, March 2016.

[102] Based on the author’s conversations with U.S. intelligence officers working on Iraq, second and third quarters of 2018. Names and places of interviews withheld at request of interviewees. The advise and assist efforts in Kirkuk, Diyala, and Nineveh will receive more focus and more intelligence, aerial, and special forces support in 2019.

[103] Based on the author’s conversations with U.S. intelligence officers working on Iraq, second and third quarters of 2018. Names and places of interviews withheld at request of interviewees. See also citations 72 and 73 (relating to journalist accounts and reporting from the Kirkuk farmbelts).

[104] Knights, “Predicting the Shape of Iraq’s Next Sunni Insurgencies,” pp. 17-18. See the author’s definition of the partnership zone. The piece suggested that the partnership zone set up in Anbar would prevent recurrence of a strong insurgency, foreshadowing the flaccid Islamic State performance in Anbar in 2018, which is described in this current December 2018 piece.

[105] Quoted in Al Naba, Edition 101, “Explosive Devices,” Oct. 12, 2017, pp. 8-9.

[106] All incident data is drawn from the author’s geolocated Significant Action (SIGACT) dataset.

[107] Patrick B. Johnston, Jacob N. Shapiro, Howard J. Shatz, Benjamin Bahney, Danielle F. Jung, Patrick Ryan, and Jonathan Wallace, Foundations of the Islamic State: Management, Money, and Terror in Iraq, 2005–2010 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016), pp. 20-22.

[108] Ibid., pp. 225-230. For a detailed description of the major Islamic State money-making operations in Mosul in 2011-2014, see Knights, “How to Secure Mosul,” pp. 2, 9, 15.

[109] For example, see “Mass grave containing the remains of 20 truckers discovered,” Baghdad Today, February 7, 2018.

[110] For a background read on the role of the Syrian civil war in the Islamic State’s rise, see Charles Lister, The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[111] For a background read on remaining Islamic State territory in Syria, see Rukmini Callimachi, “Fight to Retake Last ISIS Territory Begins,” New York Times, September 11, 2018.

[112] For a review of the rise and recovery of the Iraqi security forces, see Knights, “The Future of Iraq’s Armed Forces.”

Skip to content

Skip to content