Abstract: The border region between Iraq and Syria divided by the Euphrates River was long expected to be the Islamic State’s last stand, but many of its fighters there melted away instead. The available evidence suggests the withdrawals were part of a calculated strategy by the group after the fall of Mosul to conserve manpower and pivot away from holding territory to pursuing an all-out insurgency. In the border region and beyond, the Islamic State now seeks to mimic the strategy of attrition it so successfully adopted between its near-defeat in the late 2000s and its territorial conquest of Syria and Iraq in 2014.

In the fall of 2016, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi called on Islamic State fighters in Mosul to fight to the death to defend the city.1 They largely heeded his call. Thousands of fighters were killed, and when Mosul was liberated in July 2017, much of the city lay in ruins. Although the battle in the Islamic State’s second center of Raqqa was deadly and grinded on for four months, the group made comparably less effort to defend it. The reality is that since losing Mosul, its most sizeable and symbolic territorial possession, the Islamic State has not fought to the last man to maintain control of any other population center.

In August 2017, the group melted away from Tal Afar rather than mount an all-out resistance against advancing Iraqi forces and Shi`a militias.2 In Raqqa, while foreign fighters fought fiercely against the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), hundreds of Syrian Islamic State fighters ultimately struck a deal in October to be evacuated from the city.3 In Hawija, hundreds surrendered to nearby Kurdish forces after fleeing advancing pro-government forces.4

Even more surprisingly, there was meek resistance in the Euphrates River Valley stretching between towns such as Deir ez-Zor and Mayedin to the border town of al-Qaim and into Anbar Province, which had become an increasingly important base of operations for the group. As it lost territory elsewhere, the organization had built up a significant presence along this stretch of the Euphrates,5 and many analysts and officials had expected it to dig in and strongly defend towns there under its control.6 But in recent months, Islamic State forces largely melted away from towns and villages in the area rather than confront advancing Iraqi and Syrian forces.

While a loss of morale after the fall of Mosul, the desire by less ideologically driven fighters to save themselves, and the degradation of command and control structures all contributed to some Islamic State fighters fleeing on certain fronts,7 the available evidence suggests the withdrawals were part of calculated strategy by the group to conserve its forces and pivot away from holding territory to pursuing an all-out insurgency. Islamic State leaders were predicting the need for this shift as early as May 2016,8 and just weeks after the group lost Mosul, it called for this change of approach in its official newspaper.

This article is divided into three sections. The first looks at the Islamic State’s strategic retreat since the loss of Mosul. The second examines the group’s pivot back to insurgency. The third looks at the group’s likely strategy moving forward.

The Islamic State’s Strategic Retreat

In July 2017, the Iraqi government formally announced the liberation of Mosul after nine months of fierce fighting.9 By then, the battle to expel the militants from the group’s second center, Raqqa, was already underway. A month later, the Islamic State lost Tal Afar, an iconic stronghold for the group from which several of the group’s top leaders hailed.10 By mid-October, the militants withdrew from Hawijah, their last stronghold in Kirkuk, and were expelled from Raqqa by the U.S.-backed SDF.

The vast area that the Islamic State had controlled in 2014 had been lost and, with it, the caliphate it created. The Islamic State’s continuous territorial presence was now limited to the predominantly rural areas stretching from Haditha to the city of Deir ez-Zor. And even there, both Iraqi and Syrian forces had already begun campaigns to recapture those areas.

On September 9, 2017, the SDF announced the beginning of an offensive to expel the group from Deir ez-Zor Governorate in Syria.11 The timing of this push was in all likelihood accelerated because Russia-backed Syrian regime forces also started to advance into the governorate and then on September 5 announced the breaking of a three-year siege around Deir ez-Zor’s provincial capital.12 One of the United States’ concerns was that Iranian-backed forces could advance toward the Iraqi border,13 close off the area, and potentially disrupt the SDF’s ability to move south, as Iranian-backed groups did near the Iraqi-Jordanian border in May 2017.14

Neither of the sides racing to take Deir ez-Zor seemed adequately prepared for the battle. This was evident, for example, in the counteroffensive that the Islamic State conducted shortly after Russia announced both an incursion into the city of Deir ez-Zor15 and an intention to cross the Euphrates River running up the eastern edge of the city in an apparent effort to forestall any prospective advances by the SDF to control the eastern side of the river.16 Within hours of the Islamic State’s counterattack, several of the areas the Assad regime had secured since March 2017 temporarily fell to the group.17

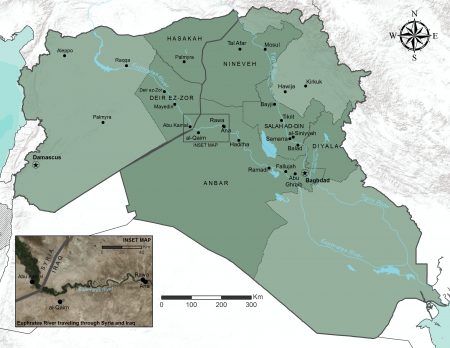

Syria and Iraq (Brandon Mohr; service layers from Esri, USGS, DigitalGlobe, and NOAA)

In the months leading up to the September 2017 “race for Deir ez-Zor,” a division of labor between Russia and Iran enabled Syrian forces to open a supply line into the city of Deir ez-Zor, which had been under siege since 2014 by the rebels and Jabhat al-Nusra and then the Islamic State.18 In the spring of 2017, Iran expanded its support for the ground campaign to seize outposts in the road networks along the way from the Syrian desert near Palmyra.19 Russia and Iran established a sprawling corridor throughout the Syrian desert to enable the expansion of regime loyalist forces inside Deir ez-Zor and to open up the possibility of moving on the Islamic State-held town of Mayedin 30 miles southeastward along the Euphrates River and the oil-rich countryside on the eastern side of the river.

During the course of September 2017, however, the rhythm of the Russia-backed offensive was initially disrupted by the Islamic State’s counterattacks in the desert areas stretching from Palmyra to the Iraqi border, thus demonstrating the fragility of months-long advances. However, the Syrian forces regained control of the areas they lost and began, within three weeks,20 to advance into Deir ez-Zor and Mayedin from the west side of the Euphrates.

On the opposite side of the river, the SDF, which launched its campaign in Deir ez-Zor in a push southward from Shaddadi in southern Hasakah, continued to march south along the areas east of the river. By the end of October 2017, the Islamic State had ceded control of the cities of Mayedin and Deir ez-Zor to the regime and its allies.21 The SDF, for its part, announced its control of oil and gas facilities east of Mayedin.22

Russia lost the race to cross the river before the SDF arrived, thus failing to reach the Iraqi borders through Mayedin, which initially seemed to be an Iranian objective. Similarly, the U.S.-backed forces lost the race to control the city of Mayedin, which officials had indicated was coveted by the international coalition as a potential source of valuable intelligence given the perceived status then of the city as a center for the Islamic State.23

In the meantime, Iraqi forces had conducted a series of shaping operations since July to expel the Islamic State from its remaining strongholds in Anbar. An offensive to liberate the border town of al-Qa’im and adjacent towns was formally announced in mid-September, starting from ’Ana in September24 and ending with the capture of Rawa and al-Qa’im in November 2017.25 On the Syrian side of the border, Iranian-backed militias also announced the expulsion of the Islamic State from the border town of Abu Kamal at the same time, on November 8, 2017.26

By this point, there were signs of a change of strategy by the Islamic State. The change was evident in areas previously thought to be key strongholds for the group, such as Mayedin, Abu Kamal, and al-Qa’im. Mayedin, specifically, had for months been regarded as having replaced Raqqa as the group’s administrative center in Syria. In April 2017, the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism published a report indicating that the Islamic State’s administrative cadres in Raqqa had left the city and relocated to Mayedin. The report, citing local sources, claimed that financial revenues in Raqqa were transported to Mayedin.27 a The Financial Times ran a similar report28 suggesting that locals in Raqqa noticed that militants suddenly vanished from the city. A month earlier, U.S. officials told The New York Times that the group’s top commanders and administrative personnel fled Raqqa and gathered in the borderlands in Iraq and Syria.29 In another report in July 2017, The New York Times reported:

“Many have relocated to Mayadeen, a town 110 miles southeast of Raqqa near oil facilities and with supply lines through the surrounding desert. They have taken with them the group’s most important recruiting, financing, propaganda and external operations functions, American officials said. Other leaders have been spirited out of Raqqa by a trusted network of aides to a string of towns from Deir al-Zour to Abu Kamal.”30

It was just not Mayedin that had emerged as a key town for the group. A few dozen miles along the Euphrates River, Abu Kamal and al-Qa’im had also long been the center of some of the group’s administrative work, even before Mosul and Raqqa came under attack. In these two towns, the Islamic State had created the only wilayat (province) that was formed by combining two Iraqi and Syrian cities, dubbed Wilayat al-Furat, or the Euphrates Province.

In this wilayat, propaganda content appeared to have been handled more centrally than anywhere else in the fading caliphate. Videos often addressed themes related to the general state of the caliphate, including the first of nearly 20 coordinated videos to show solidarity to Wilayat Sinai in Egypt in May 201631 and one featuring Uighur fighters taking a jab at the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), a Uighur jihadi group in Syria aligned with al-Qa`ida.32 Attesting to its importance to the Islamic State, Wilayat al-Furat was also where the United States and Iraq frequently report airstrikes, which kill senior members.33

The Islamic State’s presence in that region, combined with aforementioned assertions by local sources and U.S. officials, underscored the significance of these borderlands to the group as hideouts and a potential base for future operations. These areas had become the center of the Islamic State’s remaining concentration of forces, including die-hard foreign and local fighters and key commanders preserved from previous battles.34 By the late summer of 2017, they also featured at least 550 confirmed fighters who were given a free passage and had traveled from Lebanon and Raqqa in deals with Hezbollah35 and the SDF,36 respectively.

But despite its supposed significance, Mayedin fell almost abruptly and with little fighting in October 2017. Local sources speaking to Deirezzor24,37 a grassroots organization specializing in documenting violations by both the regime and jihadis, denied the city was retaken by forces loyal to Assad. The regime, uncharacteristically, produced little footage to prove it recaptured a key city. The local skepticism was an indication that the sudden withdrawal from the city was surprising to locals,38 who, along with U.S. officials, had reported that the city had become a center for the group after it came under attack in Raqqa.

Islamic State fighters also appear to have melted away in Abu Kamal and al-Qa’im, the border towns facing each other in Syria and Iraq, respectively. After earlier shaping operations by Iraqi forces, the push onto the city of al-Qa’im39 was relatively swift. Similarly, the Syrian regime and Iranian-backed militias announced they had recaptured Abu Kamal shortly after a campaign to fight the group there was launched.40

Finally, after the supposed defeat of the militants in Abu Kamal, which the Islamic State denied, the regime and its allies declared the end of the group in Syria on November 9, 2017.41

The Islamic State’s Pivot to All-Out Insurgency

With the fall of Mosul in the summer of 2017, the writing was on the wall for the Islamic State’s caliphate. Despite the weakness of the Islamic State, however, many analysts were surprised by the speed of its sudden subsequent retreats in such places as Tal Afar, Hawija, and even Raqqa, despite fierce initial resistance there. Even more surprising was its retreat in areas long perceived to be its strategic base—the borderlands and the Euphrates River Valley, where it had experience fighting or operating in for around a decade and where it reemerged in 2014.

The expectation, even in U.S. government circles, was that it would take another year to expel the Islamic State from areas it still controlled such as Deir ez-Zor and Anbar since the militants were regrouping there. Also, the group had fought fiercely in recent battles such as in Raqqa before it began to withdraw swiftly and almost suddenly from various strongholds with little fighting.

One possible explanation could be found in the Islamic State’s own publications. Al-Naba, the weekly newsletter issued by the Islamic State’s Central Media Department, hinted at a major change of strategy in a series of articles published between September and October 2017 on the topic of dealing with the U.S. air campaign. In a series of two reports in September 2017,42 the newsletter explained that Islamic State militants, having suffered heavy losses, especially in Kobane, were debating how to evade the “precision” of U.S. air forces in the face of ground assaults on multiple fronts. These fronts included the disguising of weaponry and engaging in military deception. The article concluded that it would be a mistake for the Islamic State to continue engaging forces that enjoy air support from the United States or Russia because the function of these forces was not to serve as conventional fighting forces, but mainly to provoke the militants and expose their whereabouts and capabilities for drones and aircraft to strike them. In order to prevent the depletion of its forces by air power, the article pushed for the Islamic State to adopt a counter-strategy in which it would refrain from sustained clashes in urban centers with its enemies as it did formerly. Given that the Islamic State quickly retreated from urban areas in places such as Tal Afar and Hawija in the weeks following the liberation of Mosul, it is likely the article reflected a change in strategy by the Islamic State’s leadership after the loss of Iraq’s second largest city in July 2017.

This change of tactics was also reflected in the early stages of the battle of Raqqa, where, as Al-Naba revealed, the city was divided by the Islamic State into small, self-sustained, and autonomous localities to enable militants to defend their areas with minimal movement and without the need for resupply from other districts.43 The Islamic State allowed these small groups of fighters in Raqqa to make autonomous decisions dictated by their own circumstances and needs. According to the Al-Naba article,44 another precaution in Raqqa and more generally was to avoid gathering in large numbers at the entry points of a battlefield, which would be typically bombed to pave the way for ground forces to advance and position themselves in an urban environment. “In modern wars, with precision weapons, everyone tries to avoid direct engagement with his enemy to minimize losses,” stated the article.

In another report, issued in Al-Naba on October 12, 2017,45 the Islamic State suggested that it had again been forced to switch to insurgency tactics like in the spring of 2008 under the leadership of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and his war minister Abu Hamza al-Muhajir. The article related how the group’s predecessor, the Islamic State of Iraq, had been forced to dismantle its fighting units in March 2008 and pursue a different strategy to preserve what was left of its manpower. Providing details never before disclosed, it described how the Islamic State of Iraq had become exhausted and depleted after two years of fierce fighting against U.S. and Iraqi troops to the point that it was no longer able to stand and fight for long. “In early 2008, it became clear that it was impossible to continue to engage in conventional fighting. That was when Abu Omar Al Baghdadi said: ‘We now have no place where we could stand for a quarter of an hour.’”46 The article argued the situation was now comparable and that this justified a switch of approach.

In fact, in its new iteration, well before it lost Mosul, the Islamic State had increasingly transitioned to insurgency tactics. General Joseph Votel, commander of U.S. Central Command, told reporters in May 2016 that the Islamic State “may be reverting in some regards back to their terrorist roots.”47 As noted at the time by this author, in the early months of 2016, the group stepped up hit-and-run attacks in towns it had lost, without indications that the limited number of militants involved in these operations sought to regain control of the towns.b The tactic diverged from the group’s tendency at the height of its expansion in 2014 to engage in conventional attacks, including attacks via convoys and artillery barrage. The new tactics tended to involve small units attacking from behind enemy lines or through hasty raids.48 The Islamic State at the time could be described as pursuing a hybrid strategy of territorial control and insurgency tactics.

The group also mounted attacks in areas it previously failed to enter as an army, such as in Abu Ghraib49 just to the west of Baghdad and in the coastal region in western Syria.50 Reverting back to the old insurgency and terror tactics enabled the Islamic State to penetrate otherwise well-secured areas. Previous attempts to attack them through conventional fighting units had failed, even while the group was at the height of its power.

By the spring of 2017, these new tactics, combined with its continued control of territory, raised questions among U.S. officials about the versatility and adaptability of allied Iraqi and Syrian forces51 and the kind of training they received relative to that of the Islamic State. As one senior U.S. official conceded to the author in May 2017, it was not yet possible to focus on dealing with insurgency tactics as the group still controlled significant sanctuaries.52

The Islamic State’s reversion to insurgency tactics increased as it lost more territory. Hit-and-run attacks and notable assassinations returned to newly liberated areas, such as in Salah ad-Din, Diyala, Anbar, and Raqqa,53 although such attacks were rarely accounted for in official and public statements related to progress against the group.

In Iraq, the return of the Islamic State’s activities to liberated areas was recognized long before the group lost Mosul. In October 2016, as Iraqi troops prepared for the battle in Mosul, Iraqi officials told Al Sumaria TV that the group had already begun to recruit new members among displaced civilians in areas secured since late 2014 in Samarra, in Salah ad-Din Province.54 Officials’ fears were triggered by new findings by local intelligence and a series of suicide attacks in areas between the Balad District and Samaraa,55 which officials attributed to the inability of security forces to hold and secure the liberated areas, especially near the Tigris River. “We use ambushes, but it is not enough because that requires the support of a whole brigade,” Muhammad Abbas, the commander of the Sixth Brigade of Hashd al-Shaabi, or the Popular Mobilization Units (PMUs), told Al Sumaria. Another official, Hayder Abdulsattar of the Iraqi government’s military intelligence, told the channel that the group’s numbers and activities were growing again and, along with sleeper cells, facilitating the movement of its operatives across the river.

The return of Islamic State’s activities in such areas was also reflected in multiple videos released by the group, focusing on hit-and-run attacks as well as assassinations of key security cadres. For example, Wilayat Salah ad-Din released a video in May 2016 entitled “Craft of War,” in which, seeking to replicate its previous comeback, it addressed how much the group’s new leadership had absorbed skills obtained from founding leaders like Abu Abdulrahman al-Bilawi, who planned the Mosul takeover before he was killed in June 2014.56 The 30-minute video showed operations targeting “the enemy’s rear lines” in the province, on the Bayji-Haditha road, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, as well as inside the city of Tikrit.

As in other combat videos posted by the Islamic State in recent months, the video details various attacks, the dispersing of the enemy, and the seizure of arms and vehicles from the bases of enemy forces before withdrawal. The video featured the killing of the Tikrit’s counterterrorism chief along with 31 people, including 14 policeman, after seven Islamic State fighters entered the city’s central Zuhur District wearing suicide vests and police uniforms and riding a police car, before storming the counterterrorism chief’s house.57 The commentator in the video then claimed the attacks demonstrated the current leadership’s ability to plan and execute attacks as the old guard had done years previously when it brought the group to life after it was thought to be finished.

“These operations brought to mind the planning of the Islamic State’s early leaders. The qualitative operations in Tikrit, Bayji, al-Siniyyah, Samaraa, and others … are an extension of the methodology of the commanders and leaders who had previously led the war of attrition and kept the enemy occupied, and who laid the groundwork for a long war. Men of honesty carried the banner after them to destroy their enemy, and the first sign of glad tidings appeared at their hands (showing) that Salah Ad Din was and remains a deterring place for the apostates.”

As noted earlier this year by Michael Knights in this publication, the Islamic State was already involved in intense insurgent operations in several parts of the country a year after it declared a caliphate, and especially in Diyala Province, with a level of violence in June 2017 around the same level as in 2013. In fact, in Diyala, which was never overrun by the Islamic State, an insurgency against Shi`a militia forces had been gathering pace since 2015.58 Knights’ research pointed to a full-fledged insurgency in the province led from the adjacent ungoverned space of the Islamic State pocket north of the Diyala River. “The insurgency has attained a steady, consistent operational tempo of roadside IED attacks, mortar strikes and raids on PMF outposts, and attacks on electrical and pipeline infrastructure,” Knights wrote. He added, “In Diyala, the Islamic State is already engaged in the kind of intimate violence that was seen across northern Iraq in 2013: granular, high-quality targeting of Sunni leaders and tribes working alongside the PMF.”59

There have been similar patterns of insurgent operations over the past two years in the borderlands straddling Iraq and Syria, where the group benefits from a geographic and social terrain that is difficult for counterinsurgents. In recent months, Islamic State fighters have carried out several hit-and-run attacks on military bases in the area as well as killed several high-ranking Iranian60 and Russian officers.61

The Islamic State’s Post-Caliphate Strategy

The Islamic State’s apparent decision to conserve forces for insurgency in the region stretching from Deir ez-Zor Governorate in Syria to Anbar Province in Iraq makes strategic sense given it has frequently highlighted the area as key to its survival and best suited for the base of a guerrilla war. For the Islamic State, rural- and desert-based insurgency is no less important than urban warfare to deplete its enemies, recruit members, and lay the groundwork for a comeback. The geographic and human terrain of the region provides the jihadis with an area in which they can regroup, run sleeper cells, rebuild finances through extortion, and plot attacks.

The Islamic State has repeatedly stressed the need for a desert strategy in the case of the demise of its territorial caliphate.62 This desert campaign will likely be concentrated in an area extending from Nineveh to Anbar provinces in Iraq to the city of Palmyra in Syria. The group began to articulate its post-caliphate strategy publicly and in earnest in May 201663 when its former spokesman, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, gave his last speech before he was killed in Syria in late August. In his remarks, al-Adnani prepared followers for the fall of “all the cities” under the group’s control.64 Throughout the speech, he depicted the rise and fall of his group as part of a historical flow, continuing—as a deliberate process—from the early days of the Iraq War until now.65 Territorial demise, he made clear, was merely the beginning of a new chapter in which the process of depleting the enemy does not get disrupted but persists in different forms. If and when a new opportunity for another rise presented itself, his logic went, the process of depletion will have laid the groundwork for a deeper influence than the previous round.

“Do you think, O America, that victory is achieved by the killing of one commander or more? It is then a false victory … victory is when the enemy is defeated. Do you think, O America, that defeat is the loss of a city or a land? Were we defeated when we lost cities in Iraq and were left in the desert without a city or a territory? Will we be defeated and you will be victorious if you took Mosul or Sirte or Raqqa or all the cities, and we returned where we were in the first stage? No, defeat is the loss of willpower and desire to fight.”66

In the months after the speech, the Islamic State began to talk about the desert as a viable place to launch its post-caliphate insurgency. Its propaganda has since prominently featured desert combat. Through such messages, the group hopes to show it can still inflict damage on government forces in remote areas and on critical highways linking Syria and Jordan to Iraq and to draw parallels to the fact that the last time the organization was deemed defeated in Iraq, in the late 2000s, it came back stronger than ever.

In August 2016, an editorial published in Al-Naba echoed the former spokesman’s statements about how the group understands its history. In the editorial, the authors summed up the group’s strategy after its expulsion from former strongholds in Iraq in the wake of the U.S. troop surge with the support of Sunni tribesman:

“In the years that followed the rise of Sahwa67 [Sunni collaborators] in Iraq, the mujahideen retreated into the desert after leaving behind tens of concealed mujahideen from among the security squads [i.e., sleeper cells], which killed, inflicted pain, drained, and tormented them, and confused their ranks, and exhausted their army, police, and their security apparatus, until God willed that the Knights of the Desert return to storm the apostates inside their fortresses after they had worn them out through kawatim [gun silencers], lawasiq [sticky bombs], and martyrdom operations.”

It appears that a key target for the Islamic State as it reembraces insurgency are Sunnis opposing its worldview. In its recent propaganda, the Islamic State has focused on the role of fellow Sunni collaborators in its demise in the late 2000s and has vowed to keep up the pressure against emerging ones. It is interesting that “Sahwat” was originally restricted to the tribal Awakening Councils68 established in Iraq to fight al-Qa`ida during the 2007 troop surge,69 but the group has since broadened the reference to mean opponents and collaborators from within Sunni communities writ large. As the group retreats from its strongholds, its propaganda focuses on targeting Sunni collaborators to prevent the establishment of alternative local structures that appeal to local communities in predominantly tribal and rural areas.

This fear of a Sunni or local alternative shows clearly in the group’s rhetoric. “America was defeated and its army fell in ruins, and began to collapse had it not been salvaged by the Sahwa of treason and shame,” al-Adnani stated in his May 2016 speech. One article in Al-Naba warned fellow Sunnis that the Islamic State’s mafariz amniyah, or secret security units, had since become even more skillful in “the methods of deceiving the enemy and thwarting its security plans.”70

The group’s recent rhetoric echoes a strategy it expressed in a 2010 document entitled the “Strategic Plan for the Consolidation of the Political Standing of the Islamic State of Iraq,”71 a key attempt at “lessons learned” from its near defeat and how to recover. The analysis and prescription in the document defined the group’s strategy, and the success of that strategy subsequently has come to define how the group perceives its chances of recovery today.

It is worth, therefore, examining the 2010 document in some detail, as it appears the group believes what worked before will work again. It suggested three courses of action for the group’s clandestine campaign. The first focused on targeting Iraqis enrolling in the military and police forces, especially Sunnis, and proposed “nine bullets for the apostates and one bullet for the crusaders,” accompanied by “soft” propaganda to portray enrollment in state agencies as both socially shameful and religiously sinful. The second proposed tactic was to target security bases and gatherings, deplete the government forces, divert their attention, and increase the group’s influence and mobility in as many areas as possible to launch stronger attacks in a wider area. In this context, the authors cited Sun Tzu’s maxim “reduce the hostile chiefs by inflicting damage on them; and make trouble for them, and keep them constantly engaged.” The third proposed course of action was to focus assassination attacks on critical cadres within the security forces, including operationally effective officers, engineers, and trainers. These cadres were critical to Iraqi security forces’ efforts and difficult to replace, the document explained, because of their high skills.

The goal of the proposed strategy was to deplete the enemy and preempt any effort to create security or social structures capable of entrenching the political order established in Baghdad and challenging the presence of jihadis. The campaign of incessant attacks to debilitate the enemy, which Islamic State of Iraq fighters launched inside Iraq, is a process jihadis refer to as nikayah, or war of attrition. This has again emerged as the organizing principle of the Islamic State’s insurgent campaign.

In its publications about operations in Anbar and other areas, the Islamic State often makes a reference to the “brittleness” of the defenses inside towns the group previously controlled, as it did in the Salah ad-Din video. In November 2016, Al-Naba ran an article72 about a hit-and-run attack it had conducted the month before in Rutbah,73 a strategically located town in western Iraq on the road that connects Baghdad to Amman, Jordan. According to Al-Naba, the militants stormed the city from three sides, with 20 to 30 fighters attacking from each. More than 100 local militiamen and army soldiers were claimed to have been killed after the attackers temporarily took control of the town and seized weaponry and vehicles before they withdrew. The authors wrote, “The operation to control Rutbah showed the brittle state of the areas from which the Islamic State has withdrawn, and the ability of the soldiers of the caliphate to recapture them with ease and with small groups of mujahideen.”

The newsletter claimed that the city’s defenses were concentrated on the outer parts and that most of the town fell after these were overrun, within four hours of clashes. A series of attacks in the previous months had made it easier for the Islamic State to recapture the town temporarily. Al-Naba explained the efforts at depleting the enemy in the following terms:

“Whole convoys were destroyed in more than one occasion, which caused great depletion of the apostates, the killing of hundreds of their members, the destruction of tens of their vehicles and bases, and disturbed the military presence of the Rafidah in the area, and caused a state of confusion within their ranks, factors that paved the way for the storming and recapturing of the city.”74

Syraq as the New AfPak

Even though the Islamic State has suggested it could withdraw to the desert, its attacks will still focus on urban centers, with rural areas as pathways allowing mobility between the two terrains. Headquartered in the desert or hidden in populated areas, the Islamic State aims to run a far-reaching and ceaseless insurgency in rural areas and urban centers to deter and stretch thin its opponents and to abrade any emerging governance and security structures in areas it previously controlled. Hit-and-run attacks aim to demonstrate that nothing is out of reach for the militants, even if their ability to control territory plummets.

The border region between Iraq and Syria will likely be central to this strategy. In this region—an archipelago of desert areas, river valleys, rural towns, and small urban centers—jihadis could exploit favorable socio-political conditions that once enabled the Islamic State and its predecessors to take root and reemerge from defeat. It is in this region that recent security gains are most tenuous because Iranian-backed militias were allowed to roll into Sunni heartlands75 and Shi`a and Kurdish militias were used to push out the Islamic State.

The Islamic State itself, in a number of recent videos, highlighted the centrality of this area to its resurgence in 2014. One video, for example, relayed the story of two local commanders from Anbar who, having learned from founding commanders such as Abdulrahman al-Bilawi, descended from desert camps where they had been based for years to lead operations in Anbar and Nineveh, which led to the capture of several cities and large tracts of territory in the summer of 2014.

In its new insurgent campaign, the Islamic State has both headwinds and tailwinds. The headwinds include the fact that its brutal occupation of large parts of Syria and Iraq will not soon be forgotten by much of the local population. But it still has the tailwind of the continuing Syrian civil war, which provides a broader theater in which it can operate than it had in 2010 when its leaders were mapping out their road to recovery. In Syria today, the group has continued to benefit from political grievances and the anger caused by raging violence. And it still can take advantage of rough terrain extending from the Syrian desert to the deserts near Anbar and Nineveh in its now full pivot to a campaign of terrorism and insurgency.

This contiguous terrain in Iraq and Syria is akin to the region along the Afghan-Pakistani border that previous U.S. administrations dubbed “AfPak” and treated as a single theater requiring an integrated approach. The “Syraq” space, which stretches from the areas near the Euphrates and Tigris river valleys in northern and western Iraq to Raqqa and Palmyra, looks set to be to the Islamic State what AfPak has been to the al-Qa`ida and Taliban factions, providing a hospitable environment and strategic sanctuaries. And by conserving fighters rather than fighting to the death in the battles that followed Mosul, the Islamic State still has significant manpower to sustain a campaign of terrorism and insurgency in the area. Whether the United States and the coalition that took away the Islamic State’s territorial caliphate have a counter strategy that takes into account the local reality in that region will be the difference between success and failure in truly defeating this organization. CTC

Hassan Hassan is a senior fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, focusing on militant Islam, Syria, and Iraq. He is the co-author of ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror, a New York Times bestseller chosen as one of The Times of London’s Best Books of 2015 and The Wall Street Journal’s top 10 books on terrorism. Hassan is from eastern Syria. Follow @hxhassan

Substantive Notes

[a] U.S. officials told CNN in May 2017 that they believed the Islamic State had moved all of its chemical weapons experts to the area between Mayedin and al-Qaim and that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and thousands of Islamic State operatives and supporters might be in the area. Ryan Browne and Barbara Starr, “ISIS creating chemical weapons cell in new de facto capital, US official says, CNN, May 17, 2017.

[b] In an article on the purpose of hit-and-run attacks a year later, the Islamic State explained such attacks aim to keep the enemy weak and preoccupied as the enemy has to maintain reinforcements along territories to prevent infiltration by the militants. The article further explained that militants involved in hit-and-run attacks, which the group refers to as sawlat, typically numbering anywhere between five and 15, should withdraw quickly before airstrikes are called in. “It is a method of attrition, not aimed at winning or holding territory,” the article stated. Al-Naba, edition 100, “Military Sawlat: their conditions and effect on the enemy,” July 31, 2017, p. 14.

Citations

[1] Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, “This is what Allah and His Messenger had Promised Us,” November 2, 2016.

[2] Tamer El-Ghobashy and Mustafa Salim, “Little resistance as Iraq wins battle for Tal Afar,” Washington Post, August 27, 2017.

[3] “Raqqa’s dirty secret,” BBC, November 13, 2017.

[4] “Hundreds of suspected Islamic State militants surrender in Iraq: source,” Reuters, October 10, 2017.

[5] Michael R. Gordon and Eric Schmitt, “Officials Eye Euphrates River Valley as Last Stand for ISIS,” New York Times, August 31, 2017.

[6] Author interview, anti-Islamic State coalition’s senior official, July 2017.

[7] Martin Chulov, “Losing ground, fighters and morale – is it all over for Isis?” Guardian, September 7, 2016.

[8] Hassan Hassan, “The Islamic State After Mosul,” New York Times, October 24, 2016.

[9] “Battle for Mosul: Iraqi PM Abadi formally declares victory,” BBC, July 10, 2017.

[10] Hamdi Alkhshali, Laura Smith-Spark, and Mohammed Tawfeeq, “Iraq prime minister: Tal Afar ‘liberated’ from ISIS,” CNN, August 31, 2017.

[11] “U.S.-backed forces, Syrian army advance separately on Islamic State in Deir al-Zor,” Reuters, September 8, 2017; “US-backed SDF launches offensive in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor,” Rudaw, September 9, 2017.

[12] Author interview, U.S. Department of Defense official, September 2017; Hilary Clarke and Tamara Qiblawi, “Syrian forces break ISIS’ siege of Deir Ezzor,” CNN, September 5, 2017.

[13] Fabrice Balanche, “The Race for Deir al-Zour Province,” Washington Institute, August 17, 2017.

[14] “Iran changes course of road to Mediterranean coast to avoid US forces,” Guardian, May 16, 2017.

[15] Bethan McKernan, “Isis kills 128 civilians in ‘revenge’ surprise counter attack on Syrian town,” Independent, October 23, 2017.

[16] “Russian pontoon bridges to help Syrian Army cross the Euphrates,” Almasdar News, September 13, 2017.

[17] Bethan McKernan, “Isis retakes town 200 miles into Syrian government territory in surprise counter attack,” Independent, October 2, 2017.

[18] “ISIS siege of Deir ez-Zor lifted thanks to Russian cruise missile strike – Defense Ministry,” Russia Today, September 5, 2017.

[19] “Iran attempts to expand control through Syria as ISIS nears defeat,” USA Today, June 13, 2017.

[20] “ISIS militants came with a hit list, left Syrian town in a trail of blood,” CBC News, October 23, 2017.

[21] “Syrian army captures Mayadin from ISIS near Deir ez-Zor,” Rudaw, October 14, 2017.

[22] James Masters, “Syria’s largest oil field captured by US-backed forces,” CNN, October 23, 2017.

[23] Author interview, U.S. Department of Defense and U.S. State Department officials, August 2017.

[24] “Iraqi forces ‘attack last IS bastion on Syria border,’” BBC, September 19, 2017.

[25] “Iraqi security forces retake al-Qaim from Islamic State: PM,” Reuters, November 3, 2017.

[26] “Syrian army ousts ‘IS’ from Albu Kamal, last urban stronghold in country,” Deutsche Welle, November 8, 2017.

[27] Asaad H. Almohammad and Anne Speckhard, “Is ISIS Moving its Capital from Raqqa to Mayadin in Deir ez-Zor?” International Center for the Study of Violent Radicalization, April 3, 2017.

[28] “Syria conflict: Raqqa’s civilians foresee last days of Isis,” Financial Times, April 3, 2017.

[29] Michael R. Gordon, “ISIS Leaders Are Fleeing Raqqa, U.S. Military Says,” New York Times, March 8, 2017.

[30] Ben Hubbard and Eric Schmitt, “ISIS, Despite Heavy Losses, Still Inspires Global Attacks,” New York Times, July 8, 2017.

[31] Nancy Okail, “ISIS’s Unprecedented Campaign Promoting Sinai,” Huffington Post, May 13, 2017.

[32] Caleb Weiss, “Turkistan Islamic Party parades in northwestern Syria,” FDD’s Long War Journal, November 5, 2017.

[33] Mohamed Mostafa, “Islamic State second-in-command killed in airstrike, Iraqi intelligence says,” Iraqi News, April 2, 2017.

[34] “Final military defeat of ISIS will come in Euphrates River valley: coalition,” Rudaw, August 24, 2017.

[35] “Syria war: Stranded IS convoy reaches Deir al-Zour,” BBC, September 14, 2017; “Daesh release Hezbollah fighter as convoy arrives in Deir al-Zor,” Reuters, September 14, 2017; Rob Nordland and Eric Schmitt, “Why the U.S. Allowed a Convoy of ISIS Fighters to Go Free,” New York Times, September 15, 2017.

[36] Jack Moore, “U.S. coalition allows ISIS convoy free passage to eastern Syria,” Newsweek, September 14, 2017.

[37] Author interview, Ali Alleile, executive director of DeirEzzor24, October 2017.

[38] Author interviews, local sources, October 2017.

[39] Mohamed Mostafa, “Iraqi army recaptures first area in push for ISIS havens in Anbar,” Iraqi News, September 19, 2017.

[40] “Syrian army ousts ‘IS’ from Albu Kamal, last urban stronghold in country.”

[41] “Last ISIS stronghold in Syria, Abu Kamal, totally liberated – Syrian Army,” Russia Today, November 9, 2017.

[42] Al-Naba, editions 97 and 98, series entitled “Ways to evade crusader airstrikes,” September 14 and September 21, 2017, respectively.

[43] Al- Naba, edition 94, “Aan interview with the military commander of Raqqa,”, pages 8-9, August 7, 2017, pp. 8-9.Hassan, “The Battle for Raqqa and the challenges after liberation,” CTC Sentinel 10:6 (2017).

[44] Al-Naba, edition 94, “An interview with the military commander of Raqqa,” August 7, 2017, pp. 8-9.

[45] Al-Naba, edition 101, “Explosive Devices,” October 12, 2017, pp. 8-9.

[46] Ibid.

[47] “US commander: Islamic State trying to regain initiative,” Associated Press, May 18, 2016.

[48] Hassan Hassan, “Decoding the changing nature of ISIL’s insurgency,” National, March 6, 2016.

[49] Patrick Cockburn, “Isis fights back in Iraq: Raid on Abu Ghraib punctures hopes of the jihadist group is in retreat,” Independent, February 28, 2016.

[50] “Bombs kill nearly 150 in Syrian government-held cities: monitor,” Reuters, May 23, 2016.

[51] Author interview, U.S. Department of State official, May 2017.

[52] Ibid.

[53] “Islamic State attacks Kurdish-held town on Turkish border,” Reuters, February 27, 2016.

[54] “New fears about the return of liberated areas to the control of ISIS,” Al Sumaria TV, October 18, 2016.

[55] Martin Chulov, “Iraq says Balad suicide blast is Isis attempt to stir up sectarian war,” Guardian, July 8, 2016.

[56] Kyle Orton, “The Man Who Planned the Islamic State’s Takeover of Mosul,” Syrian Intifada, January 31, 2017.

[57] “Islamic State kills 31 in Iraq’s Tikrit: security sources, medics,” Reuters, April 5, 2017.

[58] Michael Knights and Alexander Mello, “Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala: How the Islamic State could exploit Iraq’s Sectarian Tinderbox,” CTC Sentinel 9:10 (2017).

[59] Michael Knights, “Predicting the shape of Iraq’s next Sunni insurgents,” CTC Sentinel 10:7 (2017).

[60] “Senior Iranian Commander Reportedly Killed Battling ISIS in Syria,” Haaretz, November 19, 2017.

[61] “Russia says general killed in Syria held senior post in Assad’s army,” Reuters, September 27, 2017.

[62] Hassan, “The Islamic State After Mosul.”

[63] Joby Warrick and Souad Mekhennet, “Inside ISIS: Quietly preparing for the loss of the ‘caliphate,’” Washington Post, July 12, 2016.

[64] Tim Lister, “Death of senior leader at al-Adnani caps bad month for ISIS,” CNN, September 1, 2016.

[65] “ISIS spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani Calls on Supporters to Carry Out Terror Attacks in Europe, U.S.,” Middle East Media Research Institute, May 20, 2016.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Myriam Benraad, “Iraq’s Tribal ‘Sahwa’: Its Rise and Fall,” Middle East Policy Council, March 2016.

[68] Alissa J. Rubin and Stephen Farrell, “Awakening Councils by Region,” New York Times, December 22, 2007.

[69] “Bush will add more than 20,000 troops to Iraq,” CNN, January 11, 2007.

[70] Al-Naba, edition 43, “And lie in wait for them at every place of ambush,” August 18, 2016, p. 3.

[71] Murad Batal al-Shishani, “The Islamic State’s Strategic and Tactical Plan for Iraq,” Jamestown Foundation, August 8, 2014.

[72] Al-Naba, edition 53, “The Rutbah raid, how the city was conquered in a few hours,” November 3, 2016, p. 3.

[73] Loveday Morris and Mustafa Salim, “Iraqi forces retake Rutbah from ISIS and eye Fallujah for next battle,” Washington Post, May 19, 2016.

[74] Al-Naba, edition 53.

[75] Author interview, U.S. Department of Defense official, December 2017.

Skip to content

Skip to content