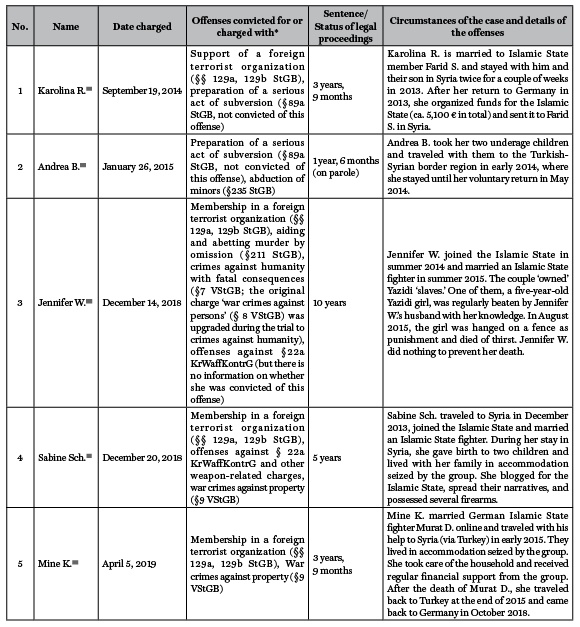

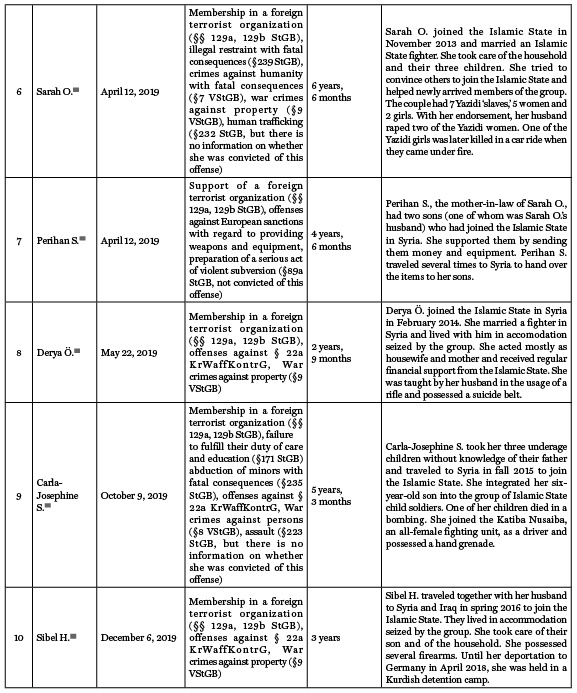

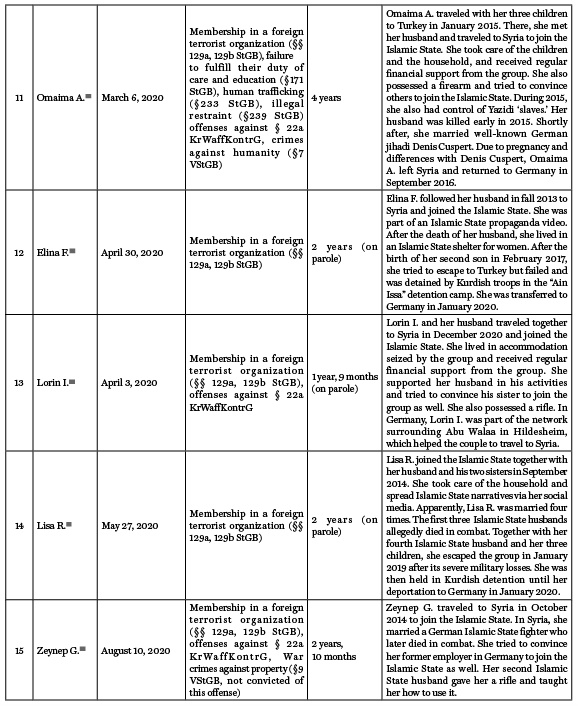

Abstract: This article examines the criminal justice approach to prosecuting women who left Germany during the last 10 years to join terrorist organizations in Syria and Iraq, including the Islamic State, and returned. In 2018, the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH) ruled that presence in Islamic State territory alone was not enough to constitute membership in a terrorist organization, complicating criminal prosecution of female returnees in Germany. In response, German prosecutors have been using both national and international law to charge and convict female returnees for carrying weapons or looting, which in turn supports their argument that women have indeed been members or supporters of a terrorist organization. This has helped them hold female returnees to Germany responsible for their crimes. Of the more than 80 German adult female returnees, 22 have been charged as of December 2021. A total of 20 have been convicted of, for example, membership in or support of a terrorist organization, weapons violations, war crimes against property, and/or crimes against humanity, with the average sentence for female returnees of three years and 10 months.

Three years and 10 months.a This is the average sentence that convicted women who traveled to Syria and Iraq to join jihadi organizations such as the Islamic State between 2011 and 2021 and returned (hereafter referred to as female returnees), have received in Germany as of December 2021. Since the military defeat of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, the German judiciary has been confronted with an increased number of foreign fightersb returning from the conflict zone. So far, authorities have had more experience dealing with male returning foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs).1 However, while at least 13 percent of all foreigners who joined the Islamic State were female, there is less experience with prosecution of female returnees.2 Women were often perceived as passive victims who were lured into joining a terrorist organization by men, as less ideological and less dangerous.3 With more information on the actual role of women within the Islamic State coming to light, this understanding is slowly changing.4 Jennifer W. is a case in point. On October 25, 2021, she was sentenced to 10 years in prison for membership in a foreign terrorist organization, aiding and abetting murder by omission, and crimes against humanity with fatal consequences. After joining the Islamic State in summer 2014, she did nothing to prevent the death of a Yazidi “slave” girl who her husband hanged on a fence as punishment.5

This article examines the criminal justice approach to prosecuting women such as Jennifer W. who left Germany between around 2011 and 2021 to join terrorist organizations in Syria and Iraq, including the Islamic State, and returned. Dealing with female returnees poses new challenges for practitioners in law enforcement, prosecution, prison, and probation as well as rehabilitation. A focus on the convictions of female returnees sheds light on the criminal justice approach to female terrorists in Germany and how it has developed in recent years.

Before embarking on this research, the authors hypothesized that the prosecution of female returnees in Germany was still based on a rather limited understanding of the roles of women in extremism and terrorism: If they were only considered naive “jihadi brides” without real agency within a terrorist organization such as the Islamic State, then this would be reflected in a lack of prosecution and conviction for terrorism offenses.6 But this article makes clear this assumption was incorrect by presenting new data on German female returnees who have been charged and convicted for terrorism-related crimes. It uses open-source material such as official press releases from the Chief Public Prosecutor’s Offices and news articles to provide insight into the publicly available information on the defendants, such as age, nationality, and charges as well as details of the conviction and the prison sentence.

After a short overview of the German foreign fighter phenomenon and existing research, this article introduces the existing German criminal justice framework to returning foreign fighters in general. It then outlines takeaways from the criminal proceedings against 22 German female returnees as of December 2021. In the final section, some preliminary conclusions are drawn and future research needs outlined. An appendix at the end of the article provides details about each of the 22 cases.

When Foreign Fighters Return

According to the German government, more than 1,150 persons have left Germany to join jihadi organizations, mostly the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, since 2011.7 Around 25 percent of those who are known to have departed Germany have since lost their lives, and many are still missing.8 In Kurdish-managed camps in northeastern Syria, roughly 30 men and 22 women who previously resided in Germany and around 150 childrenc are still said to be detained with thousands of other (former) Islamic State affiliates; nine German foreign recruits, six of them women, are said to be currently imprisoned in Iraq.9 Thirty-seven percent of the original travelers are estimated to have returned to Germany. The German government states that as of January 2021, they have information on 148 individuals who have at least temporarily joined the Islamic State and returned to Germany but the relevant statement does not differentiate between men and women.10 Based on an informal conversation between the authors and a representative of the German government in December 2021, there are more than 80 adult female returnees who have returned to Germany from the conflict zone in Syria and Iraq. Some women returned voluntarily quite early on, others in the last months of the caliphate. In addition, the German government has repatriated several women and children, most recently in October 2021.11 This is also a consequence of several court decisions obligating the government to locate and repatriate certain German minors and their mothers.

Extensive research has been done on the (European) foreign fighters who have joined terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State and those that have returned.12 Regarding Germany, researchers from the Bremen police have, for example, contributed an assessment of policies on returnees,13 and researchers at the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism have touched upon various issues such as the deprivation of nationality as a tool to deal with FTFs.14 In addition, the German Federal Criminal Police Office has conducted an extensive study on the profiles of German foreign fighters and is currently preparing one on returnees.15 Returnees present various challenges for their home countries, especially from a security perspective: While some are disillusioned, others might still adhere to extremist ideology and pose a security risk. Men and boys have often received military training and have combat experience, but women are also known to have handled weapons.16

As evidence is not always available or cannot be used in court, charging and convicting returnees is challenging. Those who are not convicted but are deemed potentially dangerous have to be monitored by security agencies, which is very resource intensive. Not all returnees are open to engage in deradicalization and disengagement programs. In addition, if convicted, they still pose a threat in prison because they can potentially radicalize other inmates. So far, Germany, like other European countries, has had little experience in dealing with this specific group of potentially radicalized female inmates.17

Regarding women and girls traveling to the caliphate, most of the research so far has looked into their background, radicalization process, or motivation to depart as well as role within the Islamic State.18 German court records are far from easily accessible, and therefore, there is no equivalent to the tracking data provided by George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, which tracks individual U.S. cases of Islamic State-related offenses since 2014.19 Even less research has been published on Germany’s returning female foreign fighters.20

In addition, there are few analyses of the prosecution of returning foreign fighters outside specialist journals, with one example of a non-specialist journal article being an article on gender stereotypes in trials of female returnees in Germany.21 One reason might be strict German data protection laws that make complete access to judicial court files quite challenging. The exact number of female foreign recruits and returnees is not publicly available. To the authors’ knowledge, there is also no public overview of charged and convicted female returnees in Germany so far, which demonstrates the relevance of the findings presented in this article.

The Criminal Justice Framework

In some European countries, such as Belgium and France, FTFs can be tried in absentia.22 This means that a person can be charged and convicted for a crime while not being present in court. The person would have to serve their sentence upon return. Germany has another approach to the prosecution of both male and female foreign fighters, however, as convictions in absentia are not allowed.

There are two main offenses that are relevant for the criminal prosecution of all returnees: “membership in a foreign terrorist organization” according to §§ 129a, 129b of the German criminal code (Strafgesetzbuch or StGB) and “preparation of a serious act of violent subversion” according to § 89a StGB. Relevant in the context of FTFs are also § 22a of the “War Weapons Control Act” (KrWaffKontrG) as well as several violations of international law (VStGB), for example, “crimes against humanity” (§ 7), “war crimes against people” (§ 8), or “war crimes against property,” such as looting (§ 9).

§§ 129a, 129b StGB covers membership in as well as support of a foreign terrorist organization. Membership is defined as an enduring participation in the organization combined with subordination to the group’s intention. The person must also perform a supporting task within the group, which can range from fighting to being a paramedic to running a Telegram channel with propaganda. The activity that constitutes membership must support the organization’s goals not just from the outside but from the inside.23 Being a supporter refers to a person who is not an actual member of the group but has a supporting role. This includes, for example, collecting money or information or sharing self-made or existing propaganda with the aim of recruiting new members or supporters. In addition to these factors, the Federal Ministry of Justice and Customer Protection has to “authorize the prosecution for acts committed for a foreign terrorist group.”24 For example, acts committed for the Islamic State could only be prosecuted with §§ 129a, 129b StGB after this authorization was issued in January 2014.

In 2015, in the wake of the rising number of jihadi travelers from Germany and other Western countries and the adoption of U.N. resolution 2178 in 2014, the German parliament passed a law to adjust the criminal code to introduce criminal liability for providing funds for terrorist organizations as well as extending §89a StGB so that it encompassed preparation of a serious act of violent subversion (for example, acts of terror or training for acts of terror) in foreign countries as well as Germany.25 This addition closed a liability gap: From this moment forward, traveling to Syria to join a terrorist group was punishable by law even if membership in a terrorist organization could not be proven.

In contrast to centralized approaches in countries such as the United Kingdom, the responsibility for nearly all terrorism investigations and prosecutions in Germany falls within the jurisdiction of the 16 German federal states. Only the prosecution of §§ 129a, 129b StGB offenses—and hence, prosecution of returnees—lies in the primary jurisdiction of the Federal Public Prosecutor General (Generalbundesanwalt or GBA).

However, due to the high number of cases, the GBA has delegated many of the cases to the chief public prosecutors of the federal states (Generalstaatsanwaltschaften or GenStA).26 This concentration of knowledge helps prosecutors run investigations more efficiently and helps to consider all different aspects of possible applicable crimes.

While, in principle, there is no discrimination between male and female prosecution, the reality is different for female returnees as the case of German citizen Sibel H. shows. She and her husband were investigated by law enforcement for traveling to Syria and Iraq, and she was investigated for membership in the Islamic State according to §§ 129a, 129b StGB. In October 2017, the GBA requested an arrest warrant for Sibel H., who had returned from Islamic State territory in Iraq; it argued that she had supported the cause of the Islamic State by joining the organization and moving to its territory, even though she did not participate in any terrorist activity. This argumentation seemed to follow the simplistic understanding that the only support women could bring to a terrorist organization was as housewives and mothers. However, the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH) did not follow the prosecutor’s line of argument and declined the request in 2018: Living within Islamic State territory was not synonymous with membership in the group.d Although it benefits the Islamic State that foreigners join their cause and travel and work in its territory, the BGH stated that as long as a person did not participate in any activity related to the terrorist organization, membership cannot be affirmed. Therefore, sympathizing with the Islamic State and living a life in the caliphate with their consent was not judged to equate to integration into the group nor membership in the terrorist organization.27

The BGH’s decision created a serious challenge for law enforcement and prosecuting authorities in how to handle returnees, especially females. From that moment onward, proving that a person had lived in Islamic State territory was no longer sufficient to secure a conviction for membership in or support of a terrorist organization.28 As a consequence, German law enforcement needed to gather more evidence on activities of suspected jihadi travelers related to the terrorist organization, such as creating propaganda. Due to difficulties in obtaining this kind of information, this posed a real problem.29

In addition, as Executive Director of the U.N. Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate (CTED) Michèle Coninsx stressed in 2018, it is especially important to “ensure that the collection, preservation, and sharing of evidence is done in accordance with all the conditions needed in front of court and for prosecutors and judges.”30 Information on the activities of female travelers is even more difficult to come by than for males.31 The result has been that arrest warrants are often not issued for female foreign fighters immediately upon their return to Germany. However, if the return of a female foreign fighter is known to law enforcement, she can be stopped, questioned, and searched on arrival at the airport.32 As they build cases against female returnees, law enforcement must often rely on information provided by the traveler’s family, statements by fellow travelers, her own social media posts, or confessions. In this context, an important source of information has been the working group on returnees within the German Federal Criminal Police Office. This unit is responsible for all questions regarding German foreign fighters detained in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey who have an intent to return to Germany and organizes their repatriation and questioning.33 Other important sources of information have been and continue to be official Islamic State documents, which provide not just an invaluable insight into the organization but also information on members of the group,34 and battlefield evidence gathered during Operation Gallant Phoenix.35 e

Takeaways from German Criminal Proceedings

In Germany, starting an investigation only requires initial suspicion of a crime, but charging and convicting someone for a crime requires far higher burdens of proof. As of December 2021, German prosecuting authorities had charged 22 women who qualify as returnees, meaning that they were either German citizens or residing in Germany before traveling to join the Islamic State and have returned to Germany. Of those 22 women, 20 have been convicted by a German court as of December 2021. Not all but most of the 22 charged women were either allegedly or proven to be part of the Islamic State; one had instead joined the terrorist organization Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria and another one allegedly joined Jund al-Aqsa before joining the Islamic State. When comparing the date of return to Germany and the filing of charges (as well as start of the trial) of female returnees, the data supports the claim that there were differences in the prosecution of female as opposed to male returnees. Law enforcement was often able to arrest male returnees shortly after their return and prosecutors were able to immediately prepare charges against them. Contrary to that course of action, even though the first woman returned in 2013, it was not before February 2015 that charges were filed against a female returnee for the first time—Andrea B.—and the trial started three weeks later.f Omaima A. was, for example, able to live several years in her hometown Hamburg after her return in 2016 before authorities arrested her and filed charges in March 2020.36

There were essentially two waves of female returnees. The first three women came back to Germany before 2014, while the second wave started in 2016 lasting until today. Due to the concentration of returnees in some federal states, the chief public prosecutors of the federal states (GenStA) with the most cases either completed or ongoing are Düsseldorf (8) and Hamburg (4). Almost all convictions according to §§ 129a, 129b StGB happened after the 2018 BGH decision. It is also worth noting that none of the convicted returnees were convicted for the updated and expanded version of §89a StGB, as they had all traveled before it came into effect.

Before looking at sentencing, it is useful to examine the cases according to the different statutes used by German prosecutors.

Support and/or membership in a terrorist organization (§§ 129a, 129b StGB)

Despite the difficulties mentioned above, since the beginning of the conflict in Syria in 2011, out of the 20 convictions, 19 female returnees were nevertheless convicted for support or membership in a terrorist organization according to §§ 129a, 129b StGB.g The first conviction according to §§ 129a, 129b StGB was that of Karolina R., who was sentenced in June 2015 to three years and nine months for supporting a terrorist organization abroad; she had traveled to Syria to transport cash and cameras.37 In the course of 2013, Karolina R. had stayed in Syria with her husband (according to ‘Islamic’ law) and son twice for several weeks but had never actually lived there.38

Since the mere presence—assumed to be limited to the role of housewife and/or mother—does not, according to the 2018 BGH ruling, qualify as membership in a terrorist organization, law enforcement, prosecutors, and courts have had since then to use a different approach to be able to prosecute and convict female returnees according to the §§ 129a, 129b StGB statute.39

Since 2018, this has included two options. One option is a new dogmatic understanding that has allowed prosecutors to argue that legal activities can still constitute membership in a terrorist organization when they are considered within a broader context, such as the intentional travel to Islamic State territory and marriage to an Islamic State member, taking children to the caliphate, or even following orders from someone with commanding authority within the Islamic State—for example, a husband or other local Islamic State commanders.40

The other option has been to use statutes under both national and international law as a ‘backdoor’ for prosecutors to argue that the accused female returnee was indeed a member of a terrorist organization.41

War Weapons Control Act (§22a KrWaffKontrG)

Female Islamic State affiliates often carried weapons, making them liable under the War Weapons Control Act (KrWaffKontrG).42 Carrying a weapon may also indicate weapons training or the provision of the weapon from the terrorist organization, which prosecutors can argue then constitutes membership in this terrorist organization.

In a high-profile case, 36-year-old German national and widow of infamous German jihadi Denis Cuspert, Omaima A. was sentenced in two separate criminal proceedings in October 2020 and July 2021 to a total of four years in prison for membership in a terrorist organization, weapons violations, failing to properly care for her children as well as aiding and abetting in crimes against humanity.43 The German attorney general had initially demanded a prison sentence of five years for Omaima A., which would have been the highest prison sentence for a female returnee at that time.44

Eleven of the 20 convicted female returnees were convicted for possession of a weapon of war, making this offense the second-most frequent crime for which female returnees were convicted.

War crimes against property (§9 VStGB)

Another circumstance that has repeatedly been used by prosecutors seeking convictions of female returnees is that foreign fighters and their families often received a house or apartment from the Islamic State. Prosecutors have argued this should be considered a case of occupation of residential properties or ‘looting by residing,’ a crime against international law and thus the German Code of Crimes against International Law (§9 VStGB). Prosecutors argue that getting a residential property from the Islamic State or other terrorist group constitutes membership in the terrorist group.45 This argument was first successfully used in the trial against Sabine Sch. in 2019, and she was sentenced for five years under §9 VStGB in conjunction with §§ 129a, b StGB.46 The BGH has since usually followed (i.e., accepted) the prosecutor’s argumentation. In total, eight of the 20 convicted female returnees were convicted for ‘looting by residing.’ All eight of these convictions happened after the 2018 BGH decision which supports the argument that German prosecutors are creatively turning to using other statues to prove membership in a terrorist group.

Crimes against humanity or war crimes (§ 7 or § 8 VStGB)

Beside ‘looting by residing,’ other violations against international law can be applied by prosecutors to female returnees, such as crimes against humanity or war crimes against persons. These convictions are mostly linked to the enslavement, torture, and killings of Yazidis by the Islamic State and its members. As of December 2021, Sarah O., Omaima A., Jennifer W., Nurten J., and Carla-Josephine S. were convicted according to § 7 VStGB (crimes against humanity) or § 8 VStGB (war crimes). The highly publicized case of Jennifer W., who allowed a Yazidi girl to die of thirst, ended with the highest prison sentence of 10 years. The court decided that Jennifer W.’s Islamic State membership had indeed supported the “annihilation of the Yazidi religion” as well as the “enslavement of the Yazidi people.”47 She was the first Islamic State member (male or female) to be charged anywhere in the world for crimes against the religious Yazidi minority.h

Sentences

The 20 convicted female returnees received an average prison sentence of three years and 10 months (including those sentenced to probation). Only four sentences involved probation rather than prison time. While every sentence must be seen as result of each of the returnees’ individual guilt, some aspects stand out. The heaviest sentence of 10 years was handed to Jennifer W. (see above), and the lightest sentence was handed to Andrea B. (one year and six months on probation for the abduction of minors and not for membership in a terrorist organization). Another interesting point is that violations of international law can enhance the sentence length due to the severity of these crimes, such as the “enslavement” of Yazidi women and girls.

But it should be noted that time in Kurdish prisons or camps can in some cases be deducted from the prison sentence, reducing the actual time in prison in Germany. A stay in a bona fide prison in Syria, Iraq, or Turkey, either as pre-trial confinement or serving a sentence, is taken account with a specific factor—for example, one year in an Iraqi prison equals three years in a German one. The time in one of the many detention camps, such as Al-Hol, is not automatically credited to the prison sentence. When assessing the returnee’s sentence, time in these detention camps is considered according to § 46 of the German criminal code (StGB), which refers to “Principles for Determining Punishment.” The time in the camps is thus used as a factor to determine the final sentence, comparable to the returnee showing remorse or confessing.

Conclusion

More than 15 percent of Western Europeans who joined the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq were women.48 As many have returned or will return in the future, countries such as Germany are facing several challenges when aiming to charge and prosecute returnees, for example due to a lack of evidence. As outlined in this article, a 2018 decision of the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH) complicated the prosecution of female returnees even further: mere presence in Islamic State territory was not considered enough to convict women of membership or support of a terrorist organization according to §§ 129a, 129b StGB. As a result of this ruling, law enforcement has had to find evidence of crimes beyond female returnees participating in daily life within the Islamic State. To affirm §§ 129a, 129b StGB offenses, prosecutors have been using evidence of several other crimes, such as breaches of the War Weapons Control Act or crimes liable under international law, such as looting.

While the BGH ruling has made filing charges and convicting female returnees more challenging, it has encouraged prosecutors to hold them accountable for other crimes under German and international law, including war crimes that they have committed. Indeed, Germany’s federal prosecutor Dr. Peter Frank had already stated in 2017: “We [the federal prosecutor] think that the membership in a foreign terrorist organization can also be confirmed when it comes to these women, since these women have strengthened the internal structures of the so-called Islamic State and thus this terror organization.”49 The results of this article demonstrate that German law enforcement and public prosecution has so far successfully adapted to the challenges caused by the 2018 BGH decision. They have been using a new approach to support their argument that female returnees were not just “jihadi brides” but full members of a terrorist organization. An analysis of various public prosecutors’ press releases demonstrates that of the more than 80 adult female returnees, 22 have been charged, 20 have successfully been convicted, and 19 for support of or membership in a terrorist organization according to §§ 129a, 129b StGB. These convictions also confirm the diversity of women’s roles beyond childcare, for example carrying and using weapons, looting, as well as aiding and abetting slavery of members of the Yazidi community. While the average sentence is three years and 10 months, the convicted women rarely serve their full prison sentences, including because long pre-trial detention as well as stays in camps or prisons abroad can be credited.50

Few publications are discussing the criminal prosecution of female returnees, and even fewer have been published on women from Germany.51 This article had the objective to bring a data-driven analysis to the debate on criminal justice approaches to female affiliates of terrorist organizations. The findings of how Germany has prosecuted female returnees have important implications for Germany as well as other (European) countries.

With their own unique legal system guiding their approach to terrorism-related cases, all countries with a significant number of foreign recruits to terrorist organizations had to develop an approach to the prosecution of returnees. For example, France had decided to criminalize the mere stay in the territory of the Islamic State and was able to systematically convict both male and female returnees accordingly since around 2016; it has also established a specific national prosecutor’s office for counterterrorism (PNAT) in 2019 as a reaction to the terrorist attacks in November 2015.52 Due to the large number of returnees, Belgium has had to treat these cases in a lower court, which means that the normal sentence for membership in a terrorist organization (which is 10 years) is divided by two.53 This leaves judges little leeway for higher sentences than five years.

Germany is one of the only countries that has successfully utilized aspects of international law to legally prove membership in a terrorist organization, especially in the case of returned women. It might provide a useful model for other countries in developing more effective prosecution of returnee cases in their respective legal systems. It is thus worth comparing the prosecution of returning foreign recruits in different countries and develop recommendations on how to leverage international law. The successful conviction of Jennifer W. for, inter alia, crimes against humanity with a prison sentence of 10 years might also serve as an example to strengthen the prosecution in other countries of crimes against the Yazidi community.

The importance of finding admissible evidence beyond just membership in the Islamic State or another terrorist organization points to the significance of international cooperation and the provision and sharing of battlefield evidence (including by the Operation Gallant Phoenix coalition) against both male and female returnees.54 Establishing and using international standards for collecting and handling battlefield evidence, which are similar to the standards in Western judicial systems, could help to make this evidence more accessible in German criminal investigations. In addition, the possibility of an international tribunal, comparable with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, to prosecute and convict former Islamic State terrorists in Syria and Iraq is subject of current debates among experts.55

The authors’ findings also have several important implications for how Germany and other countries should address the challenge of rehabilitation and reintegration of female returnees. First, every day in a camp or prison abroad might reduce the time in prison spent by a female returnee. This is potentially problematic because it can be easier for prevention counselors to establish contact with radicalized individuals in prison as opposed to individuals who are being held in a foreign prison, detention facility, or camp abroad or those who do not receive a prison sentence upon their return. In addition, while deradicalization and disengagement programs are not mandatory in Germany, prison structures can encourage inmates to accept a first talk with a prevention counselor or social worker.

Second, as risk assessment toolsi such as the Dutch VERA-2R, the German RADAR-iTE, or the Canadian HCR 20 have been developed on the basis of male cases, their results on women will likely be distorted. They should thus include additional gender-sensitive features to provide more accurate analysis of the risk that women pose.56

Third, many convicted women bring back with them (young) children, which leads to difficult questions of custody, child and youth welfare, and the reintegration of children into the education system and society. Practitioners from several European countries have pointed out the need to “improve facilities in penitentiary institutions to allow regular contacts between parents and their children, which will help rehabilitation and reintegration efforts.”57

Fourth, returnee cases are often being dealt with by various actors from the social, educational, justice, and public health sector as well as civil society. Especially in the case of Germany with its federal system, these actors need to be able to exchange good practices. In addition, greater knowledge exchange between practitioners, but also with academia and policy makers would help improve understanding of the foreign fighter returnee phenomenon and develop effective responses.

The authors’ research also points to other future research needs: for example, the need to analyze complete court files and decision-making processes (such as potential differences between sentences demanded by the prosecution and sentences handed down by the court), the need to compare the rehabilitation approaches in different (European) countries, and the need to look into the reintegration and recidivism of female returnees.

This survey of criminal proceedings against women who were proven—or alleged—to have joined jihadi organizations since 2011 and returned to Germany adds to the corpus of research making clear that women can not only be seriously involved in terrorism but have in some cases taken on active roles in violent jihadi groups and committed serious crimes. CTC

Sofia Koller has been a research fellow for counterterrorism and the prevention of violent extremism at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) in Berlin since 2018, where she also leads the project International Expert Exchange on Countering Islamist Extremism (InFoEx). Previously, she has worked as a project consultant in Lebanon and France. She holds a MA in International Conflict Studies from King’s College London. Her work focuses on deradicalization and disengagement as well as (returning) foreign fighters. Twitter: @sofia_koller

Alexander Schiele is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Essex and a lecturer at the Berlin School of Economics and Law. His research focuses on policing terrorism, social network analysis, and the crime-terror nexus. Twitter: @schielonimus

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support with this article by Tanya Mehra, Dr. Gerwin Moldenhauer, Maximilian Tkocz, Antonia Trede, Julika Enslin, Sören Hellmonds, and Tania Muscio Blanco.

© 2021 Sofia Koller, Alexander Schiele

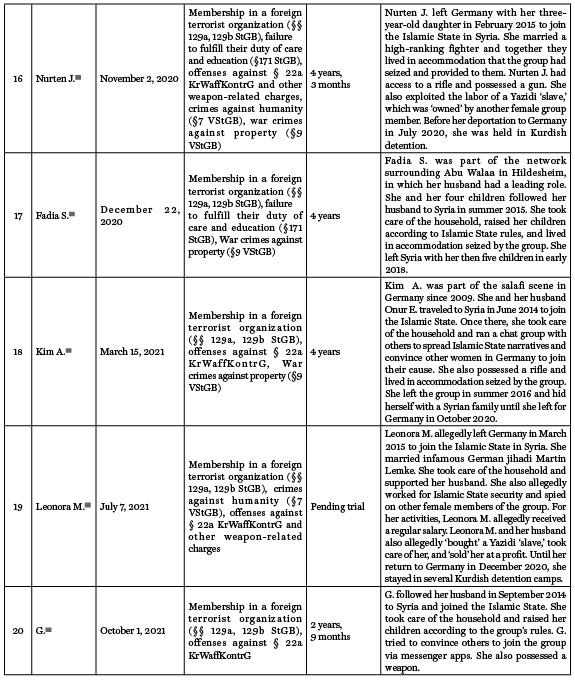

Appendix:

Substantive Notes

[a] Calculation by the authors, based on press statements of the responsible prosecutors‘ offices and courts as well as some media articles. See appendix.

[b] United Nations Security Council Resolution 2178 (2014) defines “foreign fighters” as “individuals who travel to a State other than their States of residence or nationality for the purpose of the perpetration, planning, or preparation of, or participation in, terrorist acts or the providing or receiving of terrorist training, including in connection with armed conflict.” Technically, this could also include women, but it appears that most women did not take part in these activities. “United Nations Security Council: Resolution 2178 (2014),” adopted by the Security Council at its 7272nd meeting, on September 24, 2014, U.N. Doc. S/RES/2178 (2014), p. 2.

[c] These children were either born in Germany and taken to Islamic State territory by their parents, or born abroad.

[d] This ruling applied to both support as well as membership in a terrorist organization.

[e] “Operation Gallant Phoenix is an intelligence fusion centre established in 2013 near Amman, Jordan. It comprises a large number of countries and includes a variety of agencies, including law enforcement, military and civilian personnel. It enhances the ability of member nations’ to understand and respond to current, evolving and future violent extremist threats – regardless of threat ideology.” New Zealand Ministry of Defence website.

[f] This gap at the time between date of return and indictment as well as start of the trial is probably linked to the above mentioned lack of or difficulty of compiling evidence against female returnees in general, evidence surfacing during trials against male returnees, a lack of experience with the prosecution of women for terrorism charges as well as a general perception that women had either been fulfilling domestic roles such as stay at home wife and mother of fighters’ children or naive victims of their husband who had lured or forced them to travel with them. However, a thorough analysis of the difference in prosecution between male and female returnees is still needed.

[g] Only one of the 20 female returnee convicts, Andrea B., was not convicted according to §§ 129a, 129b StGB. She was convicted only for the abduction of minors. The charge of “preparing a serious act of violent subversion” could not be proven, and she was not even charged with the possible membership in Jabhat Al-Nusra. Andrea B. was the first female returnee to be convicted in the period considered in this article, her verdict was pronounced in 2015—three years before the 2018 BGH decision. Her conviction on only non-terrorism charges might have been the consequence of a lack of evidence, experience, or determination to prosecute women who returned from jihadi organizations for terrorism charges at that time. Oberlandesgericht München, “Strafverfahren gegen Andrea B. wegen Vorbereitung einer schweren staatsgefährdenden Gewalttat u.a. (Beteiligung einer deutschen Islamistin am syrischen Bürgerkrieg),” Pressemitteilung 7 (February 2015).

[h] On November 30, 2021, Jennifer W.’s husband according to ‘Islamic’ law, Taha Al-J., was found guilty of genocide in combination with a crime against humanity resulting in death, a war crime against persons resulting in death, aiding and abetting a war crime against persons in two cases, and bodily harm resulting in death. He was sentenced to lifelong imprisonment and must pay €50,000 as compensation to the joint plaintiff. “Main sentences Taha Al-J. to lifelong imprisonment for genocide and other criminal offences,” Higher Regional Court Frankfurt, Press Center OLG Frankfurt am Main, November 30, 2021.

[i] Risk assessment tools such as RADAR-iTE (Germany) or VERA-2R (Netherlands) have been developed in the past years and are used to assess the risk of radicalized individuals and plan further steps in handling those individuals (for example, in a law enforcement or prison context). See Sofia Koller, “Good Practices in Risk Assessment for Terrorist Offenders,” DGAP Report, February 2021.

[3] See, for example, Ester E.J. Strømmen, “Jihadi Brides or Female Foreign Fighters? Women in Da’esh – from Recruitment to Sentencing,” PRIO GPS Policy Brief, 2017.

[4] See, for example, Elizabeth Pearson and Emily Winterbotham, “Women, Gender and Daesh Radicalisation: A Milieu Approach,” RUSI Journal, August 2, 2017; Erin Marie Saltman and Melanie Smith, “‘Till Martyrdom Do Us Part’: Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon,” Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2015; and Joana Cook and Gina Vale, From Daesh to diaspora. Tracing the women and minors of Islamic State (London: International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, 2018).

[5] “Strafverfahren gegen Jennifer W. wegen Verdachts der mitgliedschaftlichen Beteiligung an einer terroristischen Vereinigung im Ausland u.a.,” Oberlandesgericht München, October 25, 2021.

[6] As has already been discussed by Audrey Alexander and Rebecca Turkington in “Treatment of Terrorists: How Does Gender Affect Justice?” CTC Sentinel 11:8 (2018).

[7] “Rund 450 Dschihadisten aus Deutschland noch im Ausland,” Spiegel, December 3, 2021.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Rik Coolsaet and Thomas Renard, “From bad to worse: The fate of European foreign fighters and families detained in Syria, one year after the Turkish offensive,” Security Policy Briefs, Egmont Institute, October 2020; author interview, German expert, November 2021.

[10] See also Joseph Röhmel, “Deutsche IS-Frauen zurück in der Heimat. ‘Ich bezeichne mich nicht als radikal,’” Deutschlandfunk Kultur, July 25, 2021; German Parliament, “Antwort der Bundesregierung. Stand der Rückholung deutscher Staatsbürgerinnen und Staatsbürger und insbesondere ihrer Kinder aus den ehemaligen IS-Gebieten,” Drucksache 19/26668, February 12, 2021.

[11] Volkmar Kabisch, “Deutschland holt IS-Anhängerinnen zurück,” Tagesschau, October 6, 2021.

[12] See, for example, David Malet, Foreign Fighters: Transnational Identity in Civil Conflicts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017, 2nd edition); Hugo Micheron, Le jihadisme français: Quartiers, Syrie, prisons (Gallimard, 2020); Rekawek, Szucs, Babikova, and Lozka.

[13] Jan Raudszus, “The Strategy of Germany for Handling Foreign Fighters,” Commentary ISPI, 2020; Thomas Renard and Rik Coolsaet eds., “Returnees: Who Are They, Why Are They (Not) Coming Back And How Should We Deal With Them? Assessing Policies On Returning Foreign Terrorist Fighters In Belgium, Germany And The Netherlands,” Egmont Paper 101 (2018).

[14] See, for example, Kilian Roithmaier, “Germany and its Returning Foreign Terrorist Fighters: New Loss of Citizenship Law and the Broader German Repatriation Landscape,” ICCT, April 2019.

[15] Bundeskriminalamt, Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz and Hessisches Informations- und Kompetenzzentrum gegen Extremismus, “Analyse der Radikalisierungshintergründe und -verläufe der Personen, die aus islamistischer Motivation aus Deutschland in Richtung Syrien oder Irak ausgereist sind,” Zweite Fortschreibung, 2016.

[16] See, for example, Gina Vale, “Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps,” ICCT Policy Brief, October 2019.

[18] See, for example, Pearson and Winterbotham; Jessica Davis, “The future of the Islamic State’s Women: assessing their potential threat,” ICCT Policy Brief, June 2020.

[19] “GW Extremism Tracker: ISIS in America,” George Washington University’s Program on Extremism.

[20] Some civil society organizations, for example Hayat-Deutschland and DNE-Deutschland, working in deradicalization have published reports on needs regarding female and male returnees from a prevention perspective. See Claudia Dantschke, Michail Logvinov, Julia Berczyk, Alma Fathi, and Tabea Fischer, “Zurück aus dem ‘Kalifat:’ Anforderungen an den Umgang mit Rückkehrern und Rückkehrerinnen, die sich einer jihadistisch-terroristischen Organisation angeschlossen haben, und ihren Kindern unter dem Aspekt des Kindeswohles und der Kindeswohlgefährdung,” Journal EXIT-Deutschland, Zeitschrift für Deradikalisierung und demokratische Kultur, Sonderausgabe [Special Edition] 2018; Julia Handle, Judy Korn, Thomas Mücke, and Dennis Walkenhorst, “Rückkehrer*innen aus den Kriegsgebieten in Syrien und im Irak,” Violence Prevention Network Schriftenreihe Heft 1 (2019). In addition, there have been some publications from a legal perspective.

[23] Jan Gericke and Gerwin Moldenhauer, “Aus der Rechtssprechung des BGH zum Staatsschutzstrafrecht – Materielles Recht, 1.Teil,“ NStZ-Rechtssprechungs-Report 25:11 (2020).

[24] Gerwin Moldenhauer, “Rückkehrerinnen und Rückkehrer aus der Perspektive der Strafjustiz,” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2018; German Parliament, “Antwort der Bundesregierung. Verfolgungsermächtigungen nach § 129b des Strafgesetzbuches,” Drucksache 18/9779, September 27, 2016.

[25] German Parliament, “Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD. Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Änderung der Verfolgung der Vorbereitung von schweren staatsgefährdenden Gewalttaten (GVVG-Änderungsgesetz – GVVG-ÄndG),” Drucksache 18/4087, February 24, 2016.

[26] Moldenhauer.

[27] “Beschluss vom 22.3.2018. Az. StB 32/17,” German Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof), March 22, 2018; Gericke and Moldenhauer.

[28] Georg Mascolo, “BGH erschwert Strafverfolgung von IS-Heimkehrerinnen,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, May 24, 2018.

[31] Röhmel.

[32] Frank Bachner, “Wie sich Berlin auf die Kinder aus dem Terrorstaat vorbereitet,“ Tagesspiegel, October 31, 2019; Peter Hille and Oliver Pieper, “Was passiert mit den IS-Rückkehrern in Deutschland?” Deutsche Welle, November 15, 2019.

[33] Hamburg State Parliament, “Antwort des Senats. IS-Rückkehrer – Wie ist der Senat vorbereitet?” Drucksache 21/18968, November 19, 2019.

[34] Rukmini Callimachi, “The ISIS Files. We unearthed thousands of internal documents that help explain how the Islamic State stayed in power so long,” New York Times, April 4, 2018; Daniel Milton, Julia Lodoen, Ryan O’Farrell, and Seth Loertscher, “Newly Released ISIS Files: Learning from the Islamic State’s Long-Version Personnel Form,” CTC Sentinel 12:9 (2019).

[35] Georg Mascolo, “BKA auf geheimer Mission in Jordanien,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, December 2, 2019.

[36] Daniel Wüstenberg, “IS-Witwe posierte in Syrien mit Waffen. Jetzt lebt sie wieder in Hamburg, als wäre nichts gewesen,” Stern, April 15, 2019.

[37] “Haftstrafen im Verfahren gegen ‘Karolina R. u. a.’ wegen Unterstützung der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat Irak und Großsyrien (ISIG),’” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, June 24, 2015.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Lasse Gundelach, “Ehefrauen von IS-Kämpfern in der Rechtsprechung des BGH. Mitgliedschaft oder Unterstützung einer ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung durch Leben im Kalifat?” HRRS 20:11 (2019).

[40] Gericke and Moldenhauer.

[42] Gundelach.

[43] “IS-Prozess. Dreieinhalb Jahre Haft für Cuspert-Witwe,” NDR, October 2, 2020.

[44] “IS-Prozess. Fast fünf Jahre Haft für Cuspert-Witwe gefordert,” Hamburger Abendblatt, September 7, 2020.

[45] Gundelach.

[46] “Urteil in einem Staatsschutzverfahren wegen des Vorwurfs der Mitgliedschaft in der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ u. a.,” Oberlandesgericht Stuttgart, July 5, 2019.

[47] “Zehn Jahre Haft für IS-Rückkehrerin Jennifer W.,” Tagesschau, October 25, 2021.

[48] Cook and Vale, “From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’ II,” p. 36.

[49] “Schärfere Strafverfolgung für IS-Rückkehrerinnen,” NDR/Das Erste, Presseportal, December 14, 2017.

[50] “Frühere IS-Anhängerin Leonora M. könnte bald freikommen,” Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk, December 23, 2020.

[51] Some civil society organizations, for example Hayat-Deutschland and DNE-Deutschland, working in deradicalization have published reports on needs regarding female and male returnees from a prevention perspective. See Dantschke, Logvinov, Berczyk, Fathi, and Fischer; and Handle, Korn, Mücke, and Walkenhorst. In addition, there have been some publications from a legal perspective.

[52] PDB & France 3 PIDF, “Le parquet national antiterroriste, une force de frappe judiciaire,” France 3, Region Paris Ile-de-France, October 6, 2020.

[53] Authors’ interview, Dr. Thomas Renard, International Centre for Counter Terrorism (ICCT) in the Hague, December 2021.

[55] See, for example, Martin Chulov, “Iraqi Kurds plan special court to try suspected Islamic State fighters,” Guardian, April 30, 2021, and Ayesha Ray, “Prosecuting Western and Non-Western Islamic State Fighters,” War on the Rocks, September 22, 2021.

[56] Celina Sonka, Hamta Meier, Astrid Rossegger, Jérôme Endrass, Valerie Profes, Rainer Witt, and Friederike Sadowski, “RADAR-iTE 2.0: Ein Instrument des polizeilichen Staatsschutzes. Aufbau, Entwicklung und Stand der Evaluation,” Kriminalistik 74:6 (2020).

[57] Koller, “Women and Minors in Tertiary Prevention of Islamist Extremism.”

[58] “Anklage gegen drei mutmaßliche Unterstützer der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat Irak und Großsyrien,’” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, September 19, 2014; “Haftstrafen im Verfahren gegen ‘Karolina R. u. a.’ wegen Unterstützung der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat Irak und Großsyrien (ISIG),’” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, June 24, 2015.

[59] “Anklageerhebung gegen deutsche Islamistin wegen Beteiligung am syrischen Bürgerkrieg,” Staatsanwaltschaft München I, February 4, 2015; “Strafverfahren gegen Andrea B. wegen Vorbereitung einer schweren staatsgefährdenden Gewalttat u.a. (Beteiligung einer deutschen Islamistin am syrischen Bürgerkrieg),” Oberlandesgericht München, February 25, 2015.

[60] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat (IS)’ wegen Mordes und der Begehung eines Kriegsverbrechens erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, December 28, 2018; “Strafverfahren gegen Jennifer W. wegen Verdachts der mitgliedschaftlichen Beteiligung an einer terroristischen Vereinigung im Ausland u.a.,” Oberlandesgericht München, October 25, 2021.

[61] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ (IS) erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, January 16, 2019; “Urteil in einem Staatsschutzverfahren wegen des Vorwurfs der Mitgliedschaft in der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ u. a.,” Oberlandesgericht Stuttgart, July 5, 2019.

[62] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat‘ (IS) erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, April 17, 2019; “Urteil in dem Verfahren gegen Mine K. aus Köln wegen Mitgliedschaft in der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat,’” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, December 12, 2019.

[63] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied sowie zwei mutmaßliche Unterstützer der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat (IS)’ erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, April 24, 2019; “Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf: Versklavung von sieben Jesidinnen: Urteil in dem Verfahren gegen Sarah O. u. a.,” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, June 26, 2021; “IS-Terroristin muss ins Gefängnis,” taz, April, 21, 2021.

[64] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied sowie zwei mutmaßliche Unterstützer der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat (IS)’ erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, April 24, 2019; “Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf: Versklavung von sieben Jesidinnen: Urteil in dem Verfahren gegen Sarah O. u. a.,” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, June 26, 2021.

[65] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ (IS) erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, May 22, 2019; “Urteil des 5. Strafsenats des Oberlandesgerichts Düsseldorf Az. 5 StS 2/19,” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, December 17, 2019.

[66] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ (IS) erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, October 21, 2019; “Urteil in dem Staatsschutzverfahren gegen Carla-Josephine S.,” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, April 30, 2020.

[67] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ (IS) erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, December 23, 2019; “Freiheitsstrafe für IS-Rückkehrerin aus Unterfranken.,” br24, April 29, 2020.

[68] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ (IS) wegen Verbrechens gegen die Menschlichkeit u.a. erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, March 16, 2020; “Urteil im IS-Prozess: Cuspert-Witwe erneut schuldig gesprochen,” ndr, July 22, 2021.

[69] “Staatsschutzverfahren gegen 30-jährige Hamburgerin wegen mutmaßlicher IS-Mitgliedschaft,” Generalstaatsanwaltschaft Hamburg, June 30, 2020; “Radikal ehrlich – Ehefrau von IS-Kämpfer,” Zeit Online, September 10, 2020.

[70] “Anklage gegen mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat (IS),’” Generalstaatsanwaltschaft Celle, April 27, 2020; “Verurteilung wegen Mitgliedschaft in der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat,’” Oberlandesgericht Celle, August 21, 2020.

[71] “Anklage wegen mutmaßlicher Mitgliedschaft in einer ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung (‘Islamischer Staat’) zugelassen,’” Oberlandesgericht Koblenz, August 24, 2020; “Verurteilung wegen Mitgliedschaft in einer ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung (‘Islamischer Staat’),” Oberlandesgericht Koblenz, March 4, 2021.

[72] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat’ (IS) erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, August 20, 2020; “Kammergericht verurteilt Syrien-Rückkehrerin wegen Mitgliedschaft in der Terrorvereinigung IS und wegen Verstoßes gegen das Kriegswaffenkontrollgesetz zu einer Freiheitsstrafe,” Kammergericht Berlin, April 23, 2021.

[73] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat (IS)’ wegen Verbrechens gegen die Menschlichkeit u.a. erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, November 11, 2020; “Urteil wegen Beihilfe zu Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit,” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, April 21, 2021.

[74] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Islamischer Staat (IS)’ erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, January 7, 2021; “Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf: Mutter von fünf Kindern wegen mitgliedschaftlicher Beteiligung an der Terrororganisation ‘IS’ verurteilt,” Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, July 1, 2021.

[75] “Eröffnung des Hauptverfahrens gegen Kim Teresa A. u.a. wegen des Verdachts der Mitgliedschaft im ‘IS,’” Oberlandesgericht Frankfurt am Main, May 6, 2021; “Kim Teresa A. u.a. wegen Mitgliedschaft in einer ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung (‘IS’) zu Gesamtfreiheitsstrafe von vier Jahren verurteilt,” Oberlandesgericht Frankfurt am Main, October 29, 2021.

[76] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied des ‘Islamischer Staates’ erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, July 28, 2021.

[77] “Anklage gegen 24-Jährige wegen Mitgliedschaft im ‘IS,’” Generalstaatsanwaltschaft Hamburg, October 1, 2021; “IS-Rückkehrerin in Hamburg zu Haftstrafe verurteilt,” ndr, December 7, 2021.

[78] “Anklage gegen ein mutmaßliches Mitglied der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigungen ‘Islamischer Staat (IS)’ sowie ‘Jund al-Aqsa’ erhoben,” Generalbundesanwalt beim Bundesgerichtshof, November 2, 2021.

[79] “Kammergericht verurteilt deutsche Syrien-Rückkehrerin u.a. wegen IS-Mitgliedschaft und grober Vernachlässigung ihrer Fürsorgepflichten gegenüber ihrer Tochter zu einer Freiheitsstrafe von über drei Jahren,” Kammergericht Berlin, July 16, 2021.

Skip to content

Skip to content