Abstract: The Islamic State has shown a penchant for obtaining and recording information about the members of its organization, although the scale of this effort is not entirely clear. This article relies on 27 captured personnel documents that demonstrate how extensive the breadth of information collected was in some cases. These forms also show that the Islamic State acquired information useful for understanding the radicalization process, encouraging accountability among its fighters, managing the talent in the organization, and vetting members for potential security concerns. Not only can this type of information uncover interesting insights regarding the composition of the Islamic State’s workforce, but it can also provide researchers and practitioners with a clearer view of the likely organizational practices the group will rely on moving forward.

In November 2007, Richard Oppel, Jr., a reporter for The New York Times, described a set of documents that had been recovered in a U.S. military raid in Sinjar, Iraq, as providing significant information regarding the individuals who were traveling into Iraq to fight against the Iraqi government and coalition forces.1 Shortly thereafter, the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) at West Point released the first detailed look at those documents, which provided in-depth analysis of the demographics and origins of al-Qa`ida in Iraq’s (AQI) foreign fighter population.2

Although the level of detail about the number and composition of fighters was valuable information, the actual breadth of information contained in these forms was relatively limited. Indeed, the documents themselves contained slightly more than a dozen possible entries about each fighter, to include the incoming fighter’s name, date of birth, previous occupation, and preferred duty. These forms told relatively little about how the organization viewed the opportunities and risks associated with these incoming fighters. Perhaps, however, this lack of information speaks somewhat to the reason for the group’s struggles in appropriately managing the talent of its members. Later examinations of internal Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) documents revealed critiques about wasted opportunities to fully leverage foreign fighters.3

As ISI continued to evolve and learn the lessons of its previous mistakes, one of the areas it improved in was the amount of information it solicited from incoming fighters. When the CTC obtained over 4,000 Islamic State personnel records (the successor organization to AQI and ISI), one major difference between those records and the earlier Sinjar records was the amount of detail contained in the forms.4 There were now 23 questions that included the same information sought by the Sinjar records, but probed further regarding each fighter’s travel history, knowledge of sharia, education level, and even blood type. As noted in the CTC’s report on those documents, the expanded form demonstrated organizational learning in an effort to vet and manage its incoming cadre of fighters.5

These first two examples of the Islamic State’s efforts to manage its fighters conveyed a certain level of bureaucracy and structure that clearly signaled the group’s desire to establish itself as a lasting organization and, ultimately, a state. That said, a fair critique of this perspective could be that these forms were simple efforts that did not go far beyond what one might expect of any organization. Such a criticism, however, ignores the organizational and security challenges that a terrorist group must overcome to implement such systems.6 Beyond managing and tracking individuals, a terrorist organization must guard against potential internal security risks that threaten to destroy the group, from spies to dissatisfied members looking to change the direction of the organization.a By collecting a large amount of information regarding an individual’s background, references, and interactions with the organization, these forms provide the group with a detailed look at who each individual was and, potentially, what risks they might pose.

Such a critique also assumes that the Islamic State did not collect more information beyond what was contained in these initial forms. Given all that is now known about the sprawling bureaucracy of the Islamic State, it seems likely that the group acquired more than what was contained in those forms.7 This article examines a recently declassified collection of 27 personnel records for Islamic State fighters, both local and foreign.b These records were acquired by the U.S. Department of Defense in Syria in 2016. Although they are a few years old, the authors believe that they provide important insight into how the Islamic State thought about managing its fighters and indicate that the group has a much wider organizational scope than previously assumed.c

The Documents

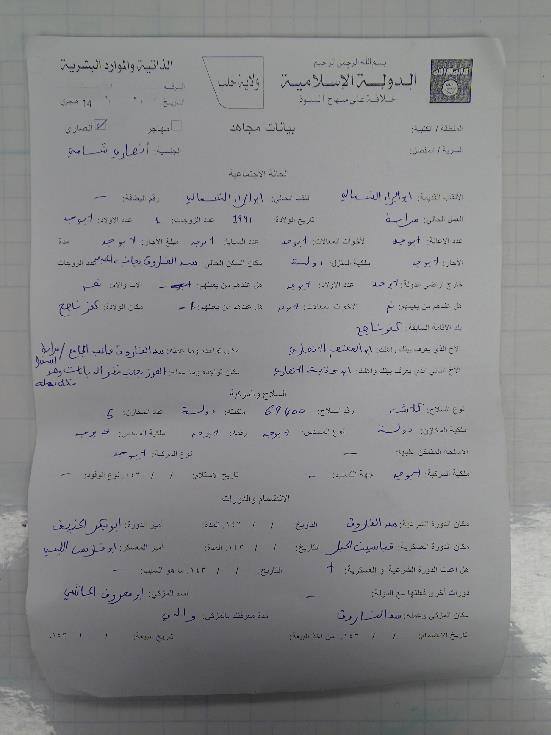

The original documents appear to have as their base a standard template printed on letter-sized paper. (See Figure 1.) The upper right-hand corner contains a printed image of the Islamic State’s flag, and other markings across the top of the page suggest that the document either covers or pertains to an office called “Personnel Affairs and Human Resources.” The information in the forms is written in ink. It is not entirely clear whether each fighter himself filled out the forms or whether it was someone else on his behalf. Nor is it clear whether the handwritten information was later entered into a database, although previous caches of captured documents suggest this as a strong possibility.

One important caveat is that all 27 forms acquired by the CTC indicate that they are from the Islamic State’s Aleppo province. There are at least two possible reasons for this. One is that Aleppo was the only province to develop their own detailed personnel tracking forms. The other is that these forms (or at the very least the collection of such detailed information) were standard across the Islamic State’s provinces, but that this particular batch of material obtained by the Department of Defense only contained information from the Aleppo province. Based on previous examinations of internal Islamic State documents that have displayed the group’s increasing bureaucratic sophistication, the authors believe the latter explanation is more likely.8

Although they share similarities with the foreign fighter intake forms discussed earlier, it is clear from the information they contain that these forms were not just filled out on one occasion. Instead, they seem to track an individual’s timeline and progress within the organization. For example, these forms contain information about the training and equipment the individual received from the Islamic State. These training fields, combined with the provincial markings discussed above, indicate that these forms were functionally different from the previously released Islamic State documents, which served mainly as initial intake questionnaires to be used when individuals either entered Islamic State territory or joined the organization locally.d These 27 forms likely served as the basis for provincial-level personnel files that tracked, to a certain extent, an individual fighter’s time in the organization. Some also included notations about unit transfers within the province or leave documents authorizing travel into or out of the Islamic State’s territory.

While there are some minor variations among them, the fighter forms analyzed in this article have slightly over 100 fields that track information across a range of categories—from the fighter’s early life to their realization of the necessity of jihad, and on to their current assignment within the Islamic State. The forms also include the usual demographic information related to age, marital status, previous and current place of residence, and educational achievements. It is important to note that each of the fields is filled out to varying degrees, such that some fields have nearly complete coverage while others have significantly less. In what follows, the authors explore these documents in two ways. First, they examine the summary statistics of various fields within the spreadsheets to give a sense of what the documents show. Second, the authors discuss how some fields illustrate the ways in which the Islamic State sought to manage its fighters, in terms of both risk and opportunity.

Selected Descriptive Statistics

It is difficult to construct an ‘average’ Islamic State fighter from the 27 profiles. As noted, there is a split population in terms of origin, as checkboxes indicated that 19 of the fighters were local (from Syria) and seven were foreigners. Of the foreigners, Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia (3), and Tunisia were represented. One of the kunyas employed by another fighter suggested he might be from the Arabian Peninsula, but did not offer specifics beyond that. Using 2016 as the base year, the fighters ranged in age from 17 to 41, with 28 being the average. The foreigners tended to be about four years older than the locals, although the small sample of foreigners may skew that estimate.

When it comes to the family status of these fighters, just over 50 percent were married (with one fighter listed as having two wives) and 46 percent have at least one child. Several fighters are listed as supporting others as dependents. Although there is a column in which female slaves can be listed, none of the forms in this batch had any information in that field. It is interesting to note that the form contained fields for fighters to indicate whether and how many individuals they supported outside of the Islamic State’s territory. This demonstrates the organization’s awareness about the potential needs and challenges facing its fighters who have responsibilities outside of the caliphate.

The documents also capture two different types of training or education: that which an individual obtained before joining the organization and that which was obtained after joining it. On the former, the form contained information about formal schooling as well as vocational training. At least eight of the fighters (about 30 percent) have some university experience or graduated from college, while at least 10 (about 37 percent) appear to have not completed their secondary education (i.e., 12th grade in the United States).

The other type of training discussed in these forms is training provided by the Islamic State after the individual joined the organization, which was separated into three categories: sharia, military, and other. For the first two types of training, the duration and name of the person in charge of the training was included. The sharia training lasted 29 days on average, while the military training averaged only 25 days in length. There was an interesting notation for the four individuals who had to repeat their sharia training.e The reason for the repetition was also indicated, with two of the individuals attending as a “repentance” course and one because of “discord with Emir.”

Analytic Insights from the Forms

Having described some of the basic demographic statistics that the authors compiled by tabulating the data in the forms, and in lieu of presenting detailed breakdowns for all 100 fields, the article now transitions into a discussion of four key analytic insights that emerge from these forms.

1. The Islamic State cared about radicalization.

The components, duration, and mechanics of the radicalization process have been widely debated in academic and policy circles for many years.9 Just as is the case for the definition of terrorism itself, this debate has yielded very little consensus. What has been absent, on some level, from these discussions is the extent to which terrorist groups themselves think about the radicalization process.

It is important to recognize that although we refer to the “radicalization” process here, the Islamic State (or any terrorist organization) probably would not recognize or employ such terminology to describe the process whereby one becomes more committed to the group’s violent ideology, especially given the negative connotation associated with the “radicalization” phraseology. Regardless of which semantics one adapts, the general idea of either approach is that it is important to acquire information and understanding about the timing of an individual’s commitment to a way of life and to an ideology. Such information is merely one way to get at the question of radicalization or commitment. In these forms, the inclusion of questions regarding the timeline of an individual’s commitment to both Islam and jihad speaks directly to that purpose.

This is not to say that these groups have not thought about recruitment or propaganda. They have clearly invested significant organizational energy into such enterprises. However, in these forms, there was a fair amount of energy dedicated to the actual collection of information that could inform various aspects of the radicalization process.

For example, one key question that is continually debated in the policy community has to do with the timing of the various stages of an individual’s journey from mainstream to extreme. Two questions in the form seem to be trying to get at the very same issue. The first asks the individual to list the date that they became “religiously committed.”f Immediately following, the second question asks the individual to identify when they became committed to the jihadi methodology or ideology. It does not specify if this is viewed as the date of commitment to the Islamic State.

Of the 27 forms in the dataset, only 18 filled these two questions in with sufficient detail to assess a general timeframe between religious commitment and commitment to the jihadi methodology. The results were a bit surprising. On average, the time between religious commitment and jihadi commitment was about six years.g Although breaking the sample down even further can only offer tentative insight, the distinction of this timeline for the 11 locals and four foreigners for whom there is data is interesting. For the locals, the time between religious and jihadi commitment averaged 7.5 years, whereas for the foreigners it was 3.25 years. It is hard to say, however, what the cause of the commitment to jihad was. While the forms of some of the individuals indicated that they were committed to jihad long before the Syrian civil war broke out, the majority of them only became committed after 2011. While there is not enough information in the forms to suggest why this is the case, one simple possibility could be the age of the individual. Perhaps those who committed to jihad after 2011 were too young to do so beforehand. While it does generally appear that younger individuals were likely to have a shorter timeline between their self-professed religious commitment and their ultimate commitment to the jihadi cause, there were still examples in the data of both young and old individuals who radicalized after 2011, suggesting that more complex factors are at play.

Of course, with such a small sample, any results need to be taken with extreme caution. To be clear, the authors are certainly not suggesting that these individuals are broadly representative of a larger population. Furthermore, whether or not the Islamic State entity that collected this information made any policy decisions with it is unknown, but the fact remains that these types of questions were being asked. The fact that these questions exist presumes that the Islamic State was willing to learn about the radicalization process in order to better their recruitment process.

2. The Islamic State placed an emphasis on accountability.

These documents also provide another insight into the group: its meticulous record-keeping not only applied to its personnel, but also to its equipment. In one section of the form, the group created a series of questions to keep track of the weapons and vehicles assigned to its fighters. There were separate categories for different types of weapons. One category seemed designed to capture information on assault rifles and heavier weapons such as grenade launchers, while the other was specifically for pistols. In some cases, the forms also include the serial numbers of the weapons; in some cases, the number of magazines in each fighter’s possession was recorded for the larger weapons.

There was also a field next to the entry of each weapon, magazine, and vehicle to indicate ownership of the item. Two responses were listed across the various forms: state (referring to the Islamic State) or personal. Although this detail may seem trivial, the fact that the group did not simply confiscate all weapons and consider them property of the organization reveals at least an attempt by the group to respect some level of ownership on the part of its fighters.

The group’s penchant for accountability has a potential counterterrorism application. All of this data collection creates opportunities for analysis that shows, using the group’s own documentation, the existence of trends within the organization that could be exploited to undermine the group. For example, it has long been noted by scholars that there is a very large divide between foreigners and locals within militant organizations.10 Many of these claims are based on interviews with a variety of participants, where the interviewee may have incentives to misrepresent the group’s internal dynamics. However, captured material such as this can provide another window into the world of foreigners versus locals in militant movements. Specifically, it is interesting to note that of the six vehicles listed across all of the forms, the four that belonged to foreigners were marked as “personal,” while of the two seemingly in the possession of locals, one was marked “State” and the other was inexplicably marked “Yes.” While the amount of data here is far too small to make any firm conclusions, information such as this on a larger scale that reveals a difference in a group’s treatment of foreign fighters, or simply in the overall status and conduct of foreign fighters, could potentially be used in a strategic messaging campaign to create friction between foreigners and locals in said group.

3. The Islamic State’s capacity for talent management was extensive.

One of the initial conclusions of the CTC’s report on the initial batch of Islamic State foreign fighter records was that those forms, which contained 23 fields, demonstrated the group’s attempt to learn from past mistakes and collect information that would allow them to fully exploit the talents of those within its organization.11 Thus, while finding that the group had information useful for the purpose of talent management is not novel, these forms demonstrate the detailed and dedicated manner in which they could have engaged in this practice using the information they collected on each fighter.

Not only is standard demographic background information collected, but so too is information about specific proficiencies that individuals brought to the organization. For example, in the portion of the form that contains information on weapons ownership, there is a question to collect details on the types of weapons on which each individual is proficient. The list contains a far greater number of weapons systems than those the individuals actually own. This information would allow the group to create special weapons groups or identify the best individuals to serve as instructors in training camps.

Also collected was information pertaining to an individual’s completion of compulsory military service in their country of origin. While this may be an added security precaution to make note of previous military affiliations and relationships, it may also be used as a mechanism to manage talent. Those with previous military experience have pre-existing knowledge regarding war fighting, which may provide an advantage on the battlefield, especially compared to younger individuals with limited experience. Though the Islamic State provided military training (as has been widely documented and as was indicated in the forms), identifying individuals with prior military experience would be advantageous for the creation of an organized fighting force.

The forms also go well beyond capturing individual fighting proficiencies. There were also efforts to take note of other skills that might prove useful to the organization. The ability to speak languages was documented, with Arabic being the leading language recorded, but with other forms indicating proficiency in English, Turkish, French, Somali, Swedish, and Danish. Oddly enough, whereas the Islamic State forms studied in the CTC’s previous work on over 4,000 entry records asked individuals to identify prior foreign travel, no such question exists on these forms. The only travel-related question is whether an individual had traveled to Turkey.

The forms also ask individuals to indicate past employment. Because the Islamic State was ultimately focused on the construction of a state, it would be beneficial to have individuals with backgrounds that can contribute to state-building. For example, one individual noted he previously practiced law, and he and several others indicated they hoped to work in a sharia court. Although it is unknown whether the Islamic State placed those individuals in its court system, it indicates that the group was likely focused on more than just producing fighters.

Also very noteworthy was a specific field that identified computer skills by asking for the specific programs with which individuals were familiar. There were fewer entries here, indicating proficiency with programs such as Microsoft Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. It is also clear that some individuals read this question differently and responded with assessments of their computer efficiency in general with words such as “mediocre” or “general.” This specific field calling for identification of computer talents provides additional evidence of the importance that terrorist organizations place on computer-related skills, which can be useful for managing the bureaucracy itself, publishing propaganda, and creating visual images that speak to the group’s overall message.

4. The Islamic State collected information useful for internal security purposes.

In the past several years, a number of stories have emerged regarding the Islamic State’s efforts to maintain internal order.12 One interesting question related to this internal security effort is how the group was able to identify individuals who potentially posed a security threat. These forms reveal that one possible answer is that it was due to the collection of detailed information regarding allegiances, weaknesses, and external connections.

For example, these forms show an effort to collect information about the connections that individuals had with others who could help verify the fidelity of the person on the form. Asking for people who knew the individual’s family or the name of their sponsor have become standard fare on these types of forms, but it is important to note the dual purpose that these questions could serve. While they certainly can help provide a character reference for a particular individual, this information could also have been used to identify relationships between individuals. With this information, the organization could potentially identify where internal threats to the organization may lie, especially as allegiances change. If an individual’s character reference turns out to be a defector from the group or a spy, perhaps additional scrutiny needs to be given to those they referred.

Beyond personal relationships, these forms also solicited information regarding an individual’s organizational relationships and history as well. For example, what other groups did the individual work with and for how long? Of course, this type of information can be used for a variety of purposes. It could be useful in building alliances and figuring out who can help mediate inter-organizational disputes, but it can also be a sign of potential risk. If someone had a long-standing relationship with another organization, then they may need to be watched especially closely during their initial time with a new organization.

This same logic may apply to questions that ask if someone was ever imprisoned by an awakening council (Sahwat) or the tyrants (taghut).h The Islamic State, especially as its time in control of territory grew and the number of airstrikes directed against it rose, likely felt paranoia over who might be working with its enemies. One way of identifying those potential threats within the organization would be to rely on records that offer information into an individual’s work history. In many governments around the world, questions similar in content to those listed above are asked on standard background or security clearance forms, and it seems that the Islamic State was at the very least collecting similar information that could have proven useful for the purposes of assessing whether someone in the organization could pose a security risk.

One other interesting aspect of these forms comes through comparing them with previous forms to see if there has been an increase in the number of vetting questions.i The Sinjar documents actually consisted of records from the period the group was known as the Mujahideen Shura Council (MSC) and the ISI. The MSC questionnaires contained only two questions focused on vetting incoming fighters by asking who coordinated the incoming fighter’s travel and the incoming fighter’s method of entry.j When the group became the ISI, that number increased to nine questions, gathering increased details about how the individual met their coordinator, their travel into Iraq and Syria, other people they met in Syria (including their descriptions), and their relationships with other mujahideen supporters, including phone numbers.

In the 4,000-plus Islamic State foreign fighter intake documents examined by the CTC, the forms asked five questions having to do with vetting and confirming recommenders. More specifically, those documents asked fewer questions about travel coordinators, instead focusing on whomever recommended the individual to the Islamic State. Those documents also added a new field to collect information, asking a question about other countries the individual had visited.

The documents being presented with this article contain 15 vetting-related questions addressing the individual’s place of immigration, their relationship with their recommender, specifics about their recommender, and about the Shaykh who incited the individual to undertake jihad. The forms also include specific questions about their imprisonment by an awakening council and or the tyrants in addition to their travel to Turkey. That the Islamic State’s provinces are concerned with gathering potential vetting data beyond that which was gathered (in the case of the foreign recruits) at the border of the Islamic State’s territory is indicative of the organization’s concern with counterintelligence in the face of so many adversaries. One important caution is that the forms presented in this article appear to be slightly more expansive than the intake forms used in previous studies. The authors also do not know whether such forms existed or not under any of the predecessor organizations to the Islamic State. One must be cautious in assuming that lack of current evidence equals lack of existence. This makes the comparison made here a bit uneven. Nevertheless, the authors believe that the increased number of vetting fields in these forms is a clear indication of the Islamic State’s desire to keep better track of who was in its organization and the potential risks they might pose.

Conclusion

This article has examined 27 forms acquired from the Syrian battlefield. These forms appear to be personnel records that, on some level, track an individual’s history within the Islamic State. While including standard biographic information, these forms also include information regarding training, disciplinary actions, and individual equipment. The authors argue that while the individual fields contained within the forms are interesting, taken together these forms provide additional insight into how the Islamic State sought to collect information, manage the talent within the organization, encourage accountability among its personnel, and assess potential security risks. More broadly, the authors believe that this article has also shown the importance of continuing to acquire and examine primary source documents created by terrorist organizations.

As the Islamic State continues to fight and attempt to embed itself in Iraq, Syria, and a number of other countries around the world, it will be important for counterterrorism efforts to recognize how the organization collects and uses information. Such information, if captured, can not only provide insight into the individuals that make up the organization, but also help illuminate organizational trends and tendencies. CTC

Daniel Milton, Ph.D., is Director of Research at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. His research focuses on the Islamic State, propaganda, foreign fighters, security policy, and primary source data produced by terrorist organizations. Follow @Dr_DMilton

Julia Lodoen is a M.A. student in international relations at the University of Chicago. Follow @JuliaLodoen

Ryan O’Farrell is a Master’s student concentrating in Conflict Management at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. Follow @ryanmofarrell

Seth Loertscher is a Research Associate at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. A former active duty Army officer, he served in a variety of operational and support roles while on active duty, deploying to both Iraq and Afghanistan. His research focuses on assessing the effectiveness of CT policy tools and trends in terrorist kidnapping and hostage-taking.

All 27 documents described in this article are accessible on the Harmony Program’s page here.

Click below for a compilation of the original language documents and the English language documents:

Substantive Notes

[a] Interestingly, the more than 4,000 records used in the CTC’s Global Caliphate report had been reportedly stolen by an Islamic State defector and leaked to the press. This highlights the security risks being discussed here.

[b] The 27 declassified documents are available on the CTC’s website. See this article’s online page, available at ctc.usma.edu/october-2019

[c] Ascertaining the exact time in which these forms were completed is difficult. However, the authors know that they came into possession of the Department of Defense in 2016, and there is indication on at least one of the forms that they were last updated early in 2015.

[d] The more than 4,000 intake forms did include questions that indicated the creator of the form may have intended for them to be updated over time and function as a personnel file to some extent. These questions included references to a recruit’s level of obedience, work assignment, and date of death. However, only a very small number of the 4,000 forms contained any information in those fields.

[e] Only three individuals had this specific column marked, although it seems clear from the information in the other fields that at least one other individual should have been marked in this column as well.

[f] There is no guide in the forms regarding what is meant by the phrase “religiously committed.” However, it is listed as a distinct question from an individual’s commitment to the jihadi methodology, suggesting that it refers to an increased level of piety and practice regarding the generally accepted tenants of Islam.

[g] In order to calculate the average time, it was necessary to assign a specific value to some individuals for whom a precise number of years was not available. For example, if the time between religious and jihadi commitment was less than a year, the individual’s time was given a value of 0.5. Additionally, the one fighter for whom the time value was “several years” was not included in this calculation.

[h] Seven fighters responded that they had been imprisoned by one of these organizations, and one fighter said that he had been imprisoned by both.

[i] Questions useful in vetting individuals with security risks include the location and method of entry into the Islamic State’s territory, details about those who recommended the individuals to the group, their sponsors, travel outside the Islamic State’s territory, and details about any time the individual spent in prison.

[j] All the individuals in the batch of documents examined identified an individual in the “Method of Entry” field, presumably the person who helped them enter the AQI territory. Joseph Felter and Brian Fishman, Al-Qa’ida’s Foreign Fighters in Iraq: A First Look at the Sinjar Records (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2008).

Citations

[1] Richard A. Oppel, Jr., “Foreign Fighters in Iraq Are Tied to Allies of U.S.,” New York Times, November 22, 2007.

[3] Unknown, “Analysis of the State of ISI,” CTC Harmony Program.

[5] Ibid., p. IV.

[6] Jacob N. Shapiro, The Terrorist’s Dilemma: Managing Violent Covert Organizations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013).

[7] Rukmini Callimachi, “The ISIS Files,” New York Times, April 4, 2018.

[8] Daniel Milton, Pulling Back the Curtain: An Inside Look at the Islamic State’s Media Organization (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2018); Aymenn al-Tamimi, “The Evolution in Islamic State Administration: The Documentary Evidence,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9:4 (2015): pp. 117-129.

[9] The radicalization literature is far more voluminous than can be cited here. For a few examples, see John Horgan, “From Profiles to Pathways and Roots to Routes: Perspectives from Psychology on Radicalization into Terrorism,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618:1 (2008): pp. 80-94 and Randy Borum, “Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories,” Journal of Strategic Security 4:4 (2011): pp. 7-36.

[10] Kristin M. Bakke, “Help Wanted? The Mixed Record of Foreign Fighters in Domestic Insurgencies,” International Security 38:4 (2014): pp. 150-187; Daniel L. Byman, “Foreign fighters are dangerous—for the groups they join,” Brookings, May 29, 2019.

[11] Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler.

[12] Nadette de Visser, “ISIS Eats Its Own, Torturing and Executing Dutch Jihadists. Or Did It?” Daily Beast, April 13, 2017; Cole Bunzel, “The Islamic State’s Mufti on Trial: The Saga of the ‘Silsila ‘Ilmiyya,’” CTC Sentinel 11:9 (2018): pp. 14-17.

Skip to content

Skip to content