Abstract: This article examines the historical trajectory of “foreign terrorist fighters” associated with the Islamic State and its antecedents, al-Qa`ida and the Arab Afghans. The article argues that the threat of foreign fighters today is best understood as being in stasis. Foreign fighters continue to pursue external operations against the West. They also transfer new tactics, techniques, and procedures between conflict zones. These patterns are not new. Beyond these historical patterns, foreign terrorist fighters have become increasingly adept at reaching out to new sympathizers and serving as interlocutors between Islamic State affiliates in conflict zones and their sympathizers. FTFs also have utilized end-to-end encryption technologies, generative artificial intelligence, and cryptocurrencies to magnify their impact. Nevertheless, it is not yet time for alarm. Countries have strengthened their laws, intelligence-sharing, and law enforcement coordination over the past decade. If governments continue to build on this collective effort and devote resources toward mitigating foreign fighter flows, the threat should remain in stasis.

On February 27, 2025, Abdisatar Ahmed Hassan was arrested in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and charged with providing material support to the Somalia branch of the Islamic State.1 According to the U.S. government, Hassan aspired to become a foreign terrorist fighter (FTF).a He attempted to travel from Minneapolis to Garowe, Somalia, on two occasions—December 13 and December 29, 2024—to join Islamic State-Somalia.2 Yet, Hassan failed both times. These failures apparently prompted Hassan to shift his efforts to attacking the United States. He failed again. Hassan was arrested after he reposted Islamic State videos encouraging followers to “kill them where you find them”b as well as his own video clips depicting hands holding a knife and an Islamic State flag.3

The story of Abdisatar Ahmed Hassan illustrates the dilemma countries face when responding to FTF travel. Hassan was 22 years old at the time of his arrest. He was born in Kenya but became a naturalized U.S. citizen.4 Upon learning of Hassan’s intention to join Islamic State-Somalia, U.S. authorities had several options: allow him to depart for Somalia, prevent Hassan’s departure and monitor him, or arrest him on somewhat minor terrorism charges. Each option has inherent risks. Historically, until late 2015, most countries opted to allow FTFs to depart for conflict zones abroad in the hopes that they would not return.5 Yet, this approach had unforeseen consequences: It caused the tactics, techniques, and ideologies of terrorist groups to metastasize globally.6

The November 2015 attacks by the Islamic State against the Bataclan concert hall, restaurants in Paris’ 11th District, as well as the Stade de France prompted a new global response to FTF travel. Western governments, in particular, reinterpreted FTFs as a threat not only to conflict zones, but also to countries of origin and transit.7 Seven of the nine individuals responsible for executing the Paris attacks were FTF returnees. They had traveled from Belgium and France to fight in the Middle East. Led by Abdelhamid Abaaoud, they subsequently returned home to recruit others and build a network of approximately 30 individuals to support terrorist attacks in Paris and Brussels.8 The Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS responded to this new understanding of the FTF threat with a collective effort to eliminate their recruitment, financing, and travel.9 These efforts, combined with the territorial defeat of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, reduced FTF flows into those countries meaningfully: from 2,000 per month in 2014 to 500 per month in 2016 and to less than a dozen by 2020.10

Despite these successes, this article argues that the threat posed by foreign terrorist fighters has not disappeared, but is best described as being in stasis. Governments have passed new laws, improved coordination, and devoted resources toward minimizing FTF travel. The Islamic State no longer retains territorial control over large swathes of Syria and Iraq. Nevertheless, the Islamic State, al-Qa`ida, and likeminded terrorist groups still have access to safe havens in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa. They continue their global outreach to sympathizers. FTF facilitators also have adjusted their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and adopted new technologies. Security authorities, therefore, must likewise continue to adapt if they hope to prevent a flare-up in the future.

The following paragraphs address the evolution and impact of foreign terrorist fighters associated with Arab Afghans, al-Qa`ida, and the Islamic State. To do so, the paragraphs trace the past, examine the present, and project into the future. The article builds on prior research, including studies conducted by the author at the RAND Corporation, the National Defense University (NDU), as well as other studies by authors resident at West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center.

A Recent History of Foreign Fighters

The modern history of foreign terrorist fightersc begins with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979.11 Approximately 20,000 so-called “Arab Afghans” traveled abroad to support the mujahideen in their fight against Soviet forces.12 Proponents argued that it was an individual religious duty (fard ayn) for Muslims to assist the Afghan mujahideen as they fought against Soviet occupation.13 They spread their message with underground pamphlets. They also regularly spoke at private gatherings in homes and mosques throughout the Muslim world.14 Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), the “Office of Services,” facilitated much but not all of the Arab Afghans’ recruitment, fundraising, and travel.15 Usama bin Ladin, the founder of al-Qa`ida, helped finance MAK soon after its inception.16

Significantly, not all of the Arab Afghans traveled to Afghanistan willingly or enthusiastically. Some were fleeing arrest, prosecution, and/or detention at home. Many of the Egyptians, for example, were forced to leave their country after Gama’a al-Islamiyya assassinated President Anwar Sadat in October 1981.17 Other Arab Afghans traveled abroad with the implicit support of their governments.d Many brought their families. They took up residence in approximately 100 safe houses or training camps along the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. This yielded a mix of expectations on the part of the Arab Afghans: Some hoped to remain, others planned to return home to their families, while still others expected to take their battlefield experiences home (or elsewhere) and continue the fight.18 In the end, once Soviet forces withdrew from Afghanistan, an estimated 80 percent of the Arab Afghans returned home, 10 percent remained in the region, and the final 10 percent scattered, relocating to Bosnia, Sudan, Yemen, Tajikistan, Chechnya, the Philippines, and other locations.19

The Arab Afghans’ dispersal led policymakers and experts to conclude that their impact would be localized.20 In many ways, this assessment was correct. Arab Afghans from Saudi Arabia and Yemen, for example, were perceived as heroes and initially reintegrated peacefully.21 In contrast, Algerian FTF returnees played an active role in that country’s civil war between 1991 and 1998, even commanding the Armed Islamic Group (GIA).22 The experiences of Arab Afghans in both Saudi Arabia and Algeria, therefore, reinforced experts’ conclusion that FTF returnees’ impact would be localized. They were mistaken. This first generation of foreign fighters retained their global relationships, newly learned skills, and well-established smuggling networks. These networks would eventually be turned against the West with attacks against military forces abroad, diplomatic facilities, and eventually homelands.

The most notable examples of Arab Afghans’ global impact can be found in external operations against multiple U.S. and French targets. Ramzi Ahmed Yousef, for example, was responsible for an attack against New York City’s World Trade Center in 1993.23 Arab Afghans also played instrumental roles in the terrorist attacks against the Paris subway (July 1995) and Arc de Triomphe (August 1995).24 They orchestrated the twin suicide attacks against U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in November 1998.25 Likewise, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri was a member of al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula. He fought against Soviet forces in Afghanistan and initially relocated to Tajikistan in the early 1990s. Al-Nashiri was the lead planner for attacks against the USS Cole on October 12, 2000, as well as the French MV Limburg, on October 6, 2002.26 Finally, perhaps most well-known, Khalid Sheikh Mohammad orchestrated al-Qa`ida’s attacks against New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia on September 11, 2001.27 In hindsight, these attacks reflect the global and long-enduring impact of the Arab Afghans.

If the first generation of foreign fighters fought in Afghanistan during the 1980s, the United States’ invasion of Iraq on March 20, 2003, referred to as Operation Iraqi Freedom, ushered in a second generation. These individuals traveled to Iraq to fight for the terrorist group that would eventually be known as al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI). AQI was led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian, who traveled to Afghanistan in the late 1980s but arrived too late to fight against Soviet forces. Instead, al-Zarqawi gathered testimony from the Arab Afghans and recorded the stories for Al-Bunyan Al-Marsus.28 He eventually established his own training camp in Herat, Afghanistan, and built a terrorist network that complemented al-Qa`ida. Al-Zarqawi fled Afghanistan after the U.S. invasion and relocated to Iraq in September 2002.29 Al-Zarqawi’s network drew over 5,000 foreign terrorist fighters between March 2003 and December 2009.30 Interestingly, approximately 60 percent of AQI’s foreign fighters reportedly came from Saudi Arabia or Libya.31 These and other FTFs conducted a vast majority—at one point, over 90 percent—of the suicide bombings against U.S. military and civilian targets during Operation Iraqi Freedom.32

More recently, on June 29, 2014, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani announced the creation of an Islamic caliphate in Syria and Iraq with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as its leader.33 This sparked a third generation of foreign terrorist fighters and the largest influx in modern history. According to the U.S. government, an estimated 35,000-40,000 FTFs traveled to Syria and Iraq, with approximately 2,000 entering per month at its peak: twice the number of Arab Afghans and four times al-Qa`ida in Iraq. 34 FTFs played a prominent role in the Islamic State’s outreach to global audiences35 and, as part of this outreach, were responsible for many of its well-known atrocities. For example, the Islamic State cell sometimes referred to as “The Beatles” was responsible for the public execution of James Foley, as well as Steven Sotloff, David Haines, Alan Henning, and others.36 Its members were called The Beatles because they had British accents. Mohammed Emwazi (aka “Jihadi John”) became the most widely recognized. He was born in Kuwait and grew up in west London. Emwazi attempted to travel to Somalia and join al-Shabaab in 2009, but he was arrested in Tanzania and sent home. Three years later, Emwazi made it to Syria: Several Islamic State videos featured Jihadi John beheading his victims.37

Amniyat al-Kharji—the team responsible for the Islamic State’s external operations—often sent foreign terrorist fighters home to execute attacks.38 The most notable was the aforementioned November 2015 attacks in Paris. FTFs functioned as “virtual planners” for Amniyat al-Kharji, providing guidance and resources to sympathizers back home as they planned attacks in the name of the Islamic State.39 Led by Abu Muhammad al-Adnani until August 2015, when he was killed by U.S. security forces, Amniyat al-Kharji conducted 132 external operations in its first two years. Fifty-two percent of these involved foreign terrorist fighters.40 While some of Amniyat al-Khariji’s early external operations were successful, others were not. In March 2017, for example, an Islamic State cell in Italy planned an attack against the famous Rialto Bridge in Venice. At least three individuals were part of this plot—Fisnik Bekaj, Dake Haziraj, Arjan Babaj—and one was a FTF returnee, having traveled previously to Syria. But this external operation was unsuccessful. Italian authorities discovered and disrupted the plot.41

The United Nations Security Council and the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS galvanized a concerted, global effort to disrupt FTF recruitment, financing, and travel. These efforts were combined with the U.S.-led Operation Inherent Resolve, which eventually wrested territorial control away from the Islamic State. While 2019 saw the territorial defeat of the group, the Global Coalition’s efforts against FTF travel continue over a decade later. In June 2024, for example, security authorities in the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, and Iceland cooperated to dismantle the I’lam Foundation’s communication infrastructure in Europe. The I’lam Foundation had taken over from al-Hayat Media Center in 2018 as the key hub for Islamic State global propaganda.42 Authorities found ties between I’lam Foundation and foreign fighter travel as well as plots against sports teams, stadiums, and events.

The Current State of Foreign Fighters

The current state of foreign terrorist fighters parallels, most closely, the period between the Arab Afghans departure from Afghanistan and Pakistan (1993) and the advent of Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003). Like this in-between period, the threat can be understood as falling into two historical categories: (1) metastasis of capabilities between conflicts abroad and (2) execution of external operations. In this sense, the present FTF threat remains consistent with historical precedent. FTFs’ impact has been reduced, however, due to continued intelligence activities, law enforcement, and international cooperation against their networks.

FTFs today plan, resource, and conduct external operations. They recruit new sympathizers back home. They also bring new tactics, techniques, and procedures into conflict zones. New technologies, such as end-to-end encryption, also make FTF facilitation easier. These technologies allow terrorist recruiters to reach new audiences and planners to improve the efficacy of their “kill them where you find them” campaigns. The following paragraphs address these trends, emphasizing the need for consistent attention and action against FTF networks globally.

Conflicts Abroad

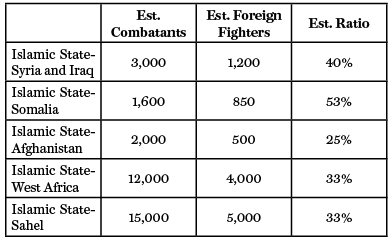

FTF recruits continue to travel abroad to join foreign terrorist groups, most notably in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa.43 Table 1 (below) estimates the number and ratio of foreign terrorist fighters for five Islamic State-affiliated terrorist groups as of September 2025.e The overall numbers of foreign terrorist fighters are more dispersed and fall well below what existed in Syria and Iraq during the height of the group’s so-called caliphate. By spring 2017, the Islamic State claimed to have over 100,000 fighters in Syria and Iraq, 40,000 (or 40 percent) of which were foreign terrorist fighters.44 Comparatively, at present, there are approximately 11,550 Islamic State-linked foreign terrorist fighters across five conflict zones.

Table 1: Number and Ratio of Islamic State Foreign Terrorist Fighters, Present

That said, the expansion and ratio of foreign to local fighters in some conflict zones—namely Somalia—are worrisome. According to the U.S. Africa Command, for example, Islamic State-Somalia increased in size from 300 fighters in 2023 to 1,600 by early 2025 with a complementary influx of foreign terrorist fighters.45 The United Nations Sanctions Monitoring Group further delineated FTFs in Islamic State-Somalia as arriving from Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia, Sudan, Morocco, and Tanzania.46

Islamic State-Somalia’s largest population of foreign fighters reportedly comes from Ethiopia.47 This makes sense given the relative proximity of these two countries. But FTFs from other neighboring countries also have played prominent roles in the group. Most notably, Bilal al-Sudani was Islamic State-Somalia’s primary facilitator and financier until he was killed in a U.S. military raid in January 2023.48 Al-Sudani originally joined al-Shabaab, a competitor terrorist group in Somalia, but defected to the Islamic State in 2015, bringing his networks with him. Until his death, al-Sudani orchestrated the transfer of funds to Islamic State affiliates regionally, including Islamic State-Mozambique, Islamic State-Central Africa, as well as Islamic State cells in South Africa.49 Islamic State-Somalia also sent funds to Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) in Afghanistan. In February 2023, the U.N. Security Council issued a report on the Islamic State’s global network. It stated that Islamic State-Somalia had sent $25,000 in cryptocurrency per month to ISK in the year prior.50

Beyond Somalia, other regional conflicts also continue to draw foreign terrorist fighters. These include ongoing fighting in Afghanistan, Nigeria, Mozambique, and Mali. The estimated ratios of foreign to local fighters for these conflicts is not as high as for Somalia (see Table 1), but the FTFs arguably have had an outsized impact on the nature of these conflicts. For example, in the summer of 2024, 13 Islamic State fighters reportedly traveled from the Middle East to the Chad River Basin to provide Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP) with the capabilities to acquire, assemble, and deploy armed drones.51 ISWAP used this newly acquired knowledge to successfully launch a drone attack against Nigerian military installations in December 2024. It was the first time that ISWAP had used armed drones in a guerrilla attack.52

In sum, the overall pattern of FTFs in conflicts abroad remains consistent today with historical trends from the period between 1993 and 1998. Small numbers of FTFs continue to travel abroad to join the Islamic State or likeminded groups. These FTFs predominantly come from neighboring countries with some limited numbers traveling far distances. FTFs bring new tactics, techniques, and capabilities with them, as well as ties to well-established global networks. As such, FTFs enable the spread of new TTPs, resources, and technologies, as well as cooperation across terrorist networks. The most worrisome new TTPs for conflict zones appear to be the rapid spread and use of commercial drone technologies and cryptocurrencies.

External Operations

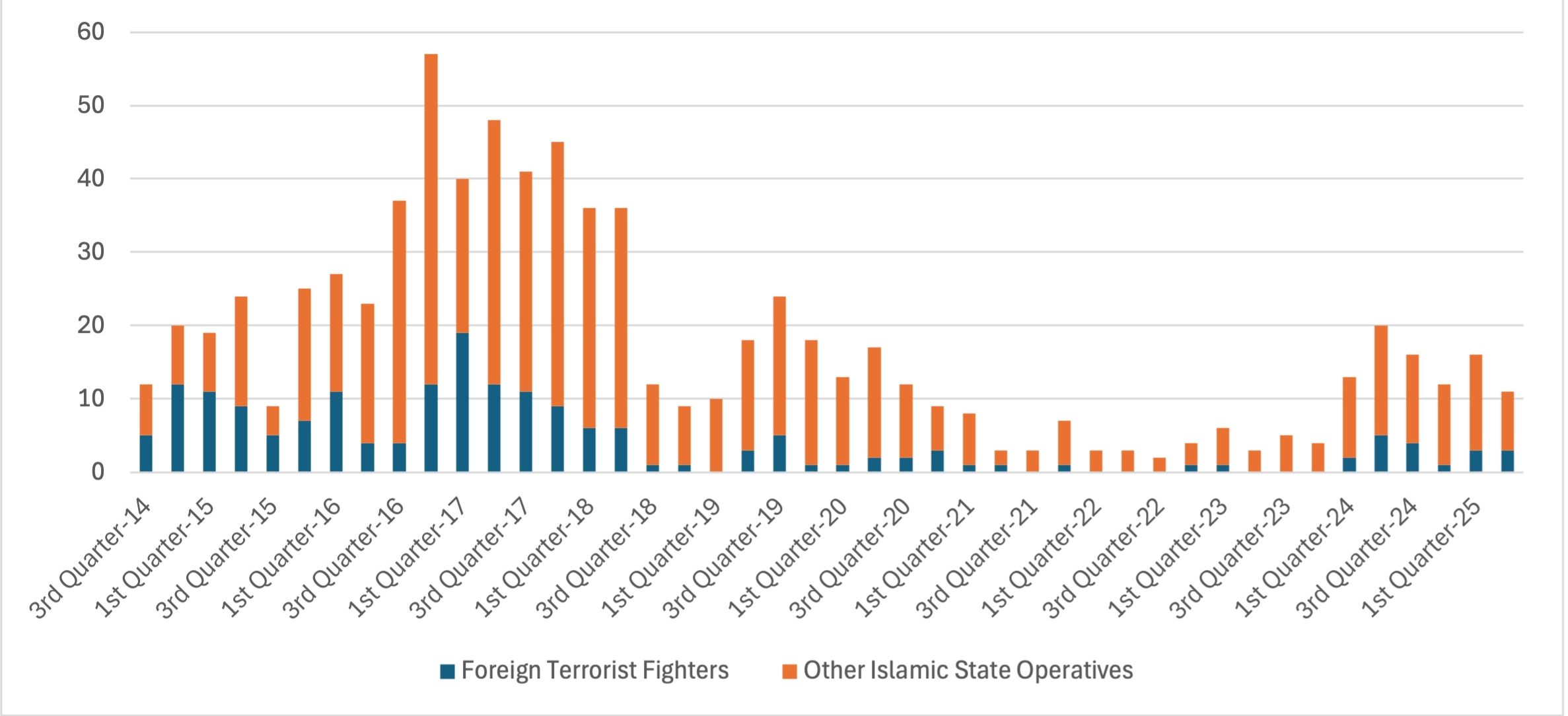

Foreign fighters are somewhat less of an immediate threat to their countries of origin or transit than conflict zones. Figure 1 illustrates this observation.f It identifies both successful and disrupted Islamic State external operations over time. Figure 1 further delineates the extent to which foreign fighters were reported to have been directly involved in the external operation. It shows a decreasing number of external operations attributable to FTF operatives. A few limited cases exist. In May 2025, for example, authorities arrested an individual in Guadalajara, Spain, on terrorist charges. He had previously fought for the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq.53 Nevertheless, Figure 1 suggests that the current threat posed by FTF returnees to their countries of origin is fairly limited.

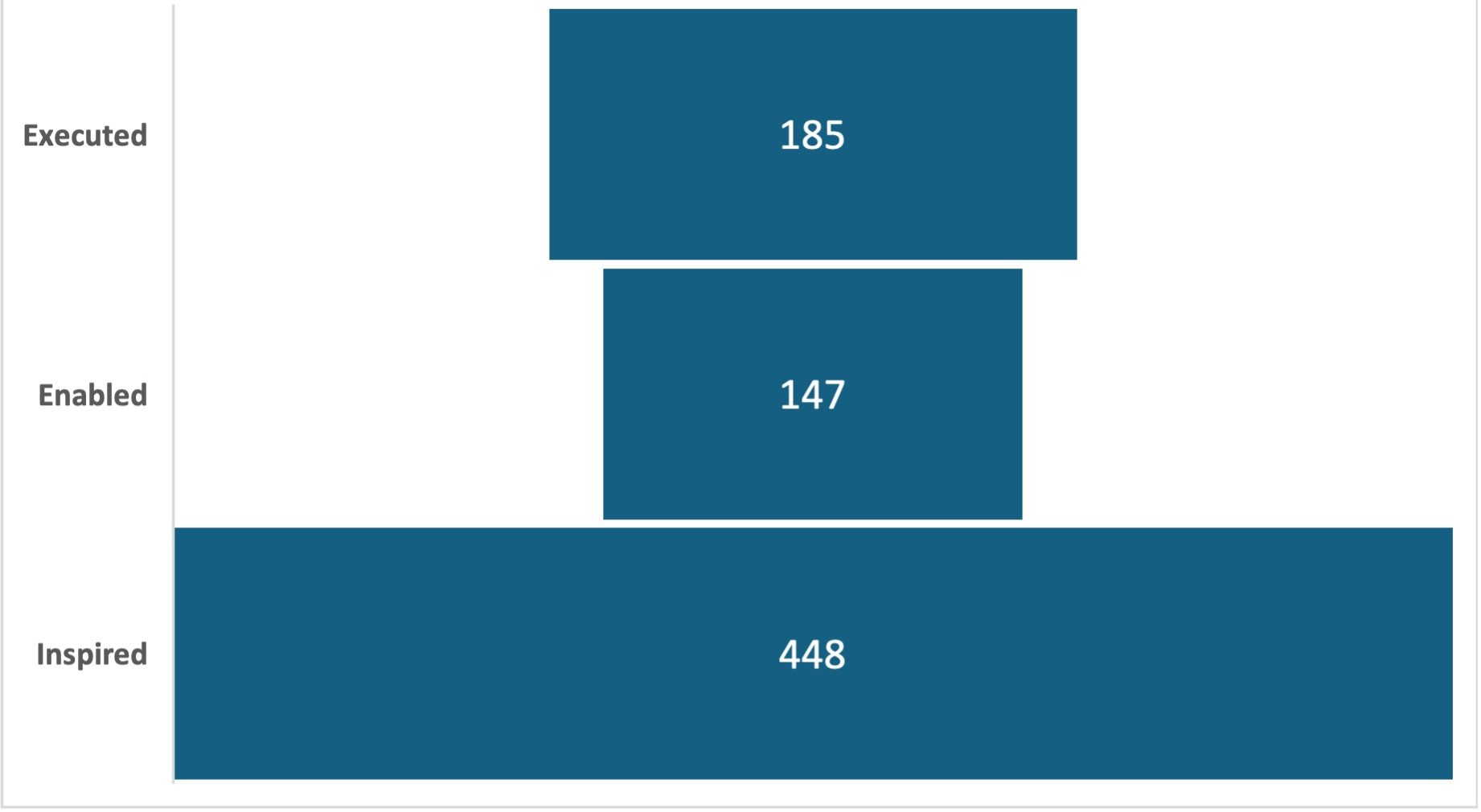

Of course, as noted previously, Islamic State affiliates also have encouraged their sympathizers to “kill them where you find them” over the years. Experts tend to refer to these external operations as being inspired rather than planned and executed by known Islamic State members and returnees. Some inspired attacks, however, are instigated, planned, and financed by foreign fighters. Indeed, FTFs continue to play a role in facilitating recruitment of sympathizers, providing them with guidance, as well as resources for external operations. Figure 2 (below) illustrates this observation. It shows the proportion of external operations executed by foreign fighters as compared to those enabled remotely by FTFs planners and financiers and those fully inspired with no foreign fighter involvement.

FTFs have taken advantage of new technologies in pursuit of external operations. I’lam Foundation, discussed above, utilized generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) to create and translate propaganda as part of its outreach to sympathizers.54 FTF facilitators also have reportedly used a Monero wallet to send and receive cryptocurrency between Islamic State affiliates and their sympathizers. In May 2025, Turkish intelligence discovered that Özgr Altun, also known as Abu Yasser al-Turki, planned to travel from Afghanistan into Pakistan. Al-Turki was the senior-most foreign fighter in Afghanistan from Turkey. He functioned as a propagandist, fundraiser, and facilitator and, as such, contributed to travel into and out of Europe, including in support of Islamic State external operations.55 Turkish intelligence notified their counterparts in Pakistan and al-Turki was arrested. Soon after his arrest, pro-Islamic State channels on Rocket.Chat noted al-Turki’s absence, and a new Monero wallet address was distributed with the notation that the old address was compromised.56

Finally, some individuals have attempted both. That is, they aspire to fight for the Islamic State abroad, encourage others to do so, but also cannot overcome the hurdles to get into a conflict zone. These individuals often turn their attention inward. Abdisatar Ahmed Hassan, the individual from Minnesota who aspired to fight for Islamic State-Somalia, illustrates this growing trend in foreign terrorist fighters. Indeed, approximately 10 percent of all “inspired” attacks since July 1, 2014, have been conducted by individuals who tried to get to conflict zones, but were halted along the way and sent home or could otherwise not overcome the hurdles. It is not new per se. The number and percentage also arguably are indicative of “success” in global counterterrorism. However, it requires constant attention by local and international law enforcement to maintain these low numbers.

Conclusion

Foreign terrorist fighters remain a threat. They continue to travel abroad and, in doing so, transfer new tactics, techniques, and procedures between conflict zones. Foreign terrorist fighters also continue to be interested in executing external operations back home. These patterns are not new. Beyond these historical patterns, foreign terrorist fighters have become increasingly adept at reaching out to new sympathizers and serving as interlocutors between Islamic State affiliates in conflict zones and their sympathizers. FTFs also have utilized end-to-end encryption technologies, GenAI, and cryptocurrencies to magnify their impact.

Nevertheless, while foreign fighters remain a threat, current trends are worrisome but not alarming. They simply mean that security authorities cannot dismiss the threat of foreign terrorist fighters as something that may, potentially, rise in the future. It must be managed on an ongoing basis. It requires sustained resources devoted to intelligence collection on foreign fighter flows. Intelligence agencies also need to share this intelligence with their counterparts in other countries to effectively mitigate FTF travel. Law enforcement agencies must continue to investigate and arrest individuals who not only plan, finance, or execute attacks within their borders, but also those enabling attacks abroad. Immigration and border security officials, likewise, should share information on possible foreign fighter recruitment, facilitation, and travel.

Most importantly, as governments monitor and coordinate their efforts, special attention should be given to how foreign fighters adapt and change their tactics, techniques and procedures. Officials should expect FTFs to adapt under pressure, especially if they are attempting to mobilize support in response to a particularly resonate conflict. Intelligence, military, and law enforcement agencies will need to be equally adaptive. Further, rapid influxes of people, money, and weapons into and out of conflict zones should trigger warnings. These influxes could be an indicator of a potential increase in the threat of external operations. Finally, intelligence and law enforcement agencies should be wary of falling into the trap of believing that FTFs’ departure makes their own country safe. Foreign fighters inevitably turn their attention back home. CTC

Kim Cragin, PhD, is director of the Center for Strategy and Military Power within the National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies. She is a widely published expert on counterterrorism, foreign fighters, and terrorist group adaptation. The opinions expressed here are her own and not those of the National Defense University, the Department of War, or the U.S. government.

© 2025 Kim Cragin

Substantive Notes

[a] The United Nations Security Council defines foreign terrorist fighters as individuals “who travel or attempt to travel to a State other than their States of residence or nationality … for the purpose of the perpetration, planning, or preparation of, or participation in, terrorist acts, or the providing or receiving of terrorist training.” This definition can be found in “United Nations Security Council Resolution 2178,” United Nations, September 24, 2014.

[b] In January 2016, the Islamic State released a video that featured its November 2015 attacks in Paris, France, and encouraged its followers to “kill them where you find them.” This directive was presented as an alternative to attempting to become foreign terrorist fighters. Subsequent Islamic State releases have echoed this call. Most recently, beginning in January 2024, the group announced a “kill them where you find them” campaign in solidarity with Palestinian residents of the Gaza Strip. For more information, see Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Results of the Islamic State’s ‘And Kill Them Wherever You Find Them’ Expedition,” Middle East Forum, January 12, 2024.

[c] This article only examined foreign terrorist fighters associated with the Arab mujahideen in Afghanistan, al-Qa`ida, the Islamic State, and likeminded terrorist or insurgent groups.

[d] In his book, Jihad in Saudi Arabia, Thomas Hegghammer argues that the flow of volunteers from Saudi Arabia increased in 1987 after the Saudi mainstream media began to report on the activities of FTFs in Afghanistan and implicitly encourage their audiences to join them. See Thomas Hegghammer, Jihad in Saudi Arabia: Violence and Pan-Islamism since 1979 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[e] The numbers in this table on the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq only include those not in detention facilities or camps. The numbers are estimates, derived from multiple sources, including “United Nations Sanctions Monitoring Team Report, S/2025/482,” United Nations, July 24, 2025; “United Nations Sanctions Monitoring Team Report, S/23/95,” United Nations, February 13, 2023; “Foreign Terrorist Fighters in the Sahel-Sahara Region of Africa,” African Center for the Study of Terrorism (African Union), Policy Paper, April 2022; and Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “How Many Fighters Does the Islamic State Really Have?” War on the Rocks, February 9, 2015.

[f] The data presented here was derived from a database developed and maintained by the author at the National Defense University. It includes all successful external operations conducted by Islamic State operatives and sympathizers from its inception. The database also includes all publicly reported disrupted plots, defined as the arrest of perpetrators who have identified the target, purchased the weapons, and made plans (e.g., logistics) to conduct the attack. The disrupted plots incorporate those halted by the U.S. military and its allies through airstrikes or raids on Islamic State external operations planners. The data was derived from multiple sources, including media reports, reports released by the United Nations, Europol, and the African Union. The author also attempts to validate the data through interviews with academics, experts, and officials in countries with the highest level of external operations. Finally, U.S. Central Command also regularly provides updates on its strikes and often names the operative targeted. If basic research through media reports and/or Islamic State propaganda confirms that these individuals helped plan a previous external operation, then this strike is counted as “disrupting” a future plot.

Citations

[1] United States of America vs Abdisatar Ahmed Hassan, 25-mj-104 (DLM) United States District Court for the District of Minnesota, February 27, 2025.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] R. Kim Cragin, “Preventing the Next Wave of Foreign Terrorist Fighters: Lessons Learned from the Experiences of Algeria and Tunisia,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 44:7 (2019).

[6] R. Kim Cragin and Susan Stipanovich, “Metastasis: Exploring the Impact of Foreign Fighters in Conflicts Abroad,” Journal of Strategic Studies 42:1 (2017).

[7] “United Nations Security Council Resolution 2396,” United Nations, December 21, 2017.

[8] R. Kim Cragin, “The November 2015 Paris Attacks: The Impact of Foreign Fighter Returnees,” Orbis 61:2 (2017).

[9] “United Nations Security Council Resolution 2396.”

[10] Cragin, “Preventing the Next Wave of Foreign Terrorist Fighters;” “U.S. military softens claims on drop in Islamic State’s foreign fighters,” Reuters, April 29, 2016.

[11] Lawrence Wright, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 (New York: Vintage Books, 2006); Abdel Bari Atwan, The Secret History of al-Qa’ida (London: Saqi Books, 2006).

[12] Thomas Hegghammer, “The Rise of Muslim Foreign Fighters,” International Security 235:3 (2010/2011): pp. 53-94.

[13] Kim Cragin, “Early History of al-Qa’ida,” Historical Journal 51:4 (2008): pp. 1,047-1,067.

[14] Montasser al-Zayat, The Road to al-Qaeda: The Story of Bin Laden’s Right-Hand Man (edited by Sara Nimis, translated by Ahmed Fekry) (London: Pluto Press, 2002).

[15] Ibid.; Abdullah Anas, To the Mountains: My Life in Jihad from Algeria to Afghanistan (translated by Tam Hussein) (London: Hurst Publishers, 2019).

[16] Cragin, “Early History of al-Qa’ida.”

[17] Al-Zayat.

[18] S. Gharib, “Abu Hamzah on Life, Islam, Islamic Groups,” al-Mujalla, March 21, 1999; R. Kim Cragin, “The Challenge of Foreign Fighter Returnees,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 33:2 (2017).

[19] Cragin, “The Challenge of Foreign Fighter Returnees.”

[20] Thomas Hegghammer, Jihad in Saudi Arabia: Violence and Pan-Islamism since 1979 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Abdel Bari Atwan, After Bin Laden: Al Qaeda, The Next Generation (London: The New Press, 2012); Kenneth Conboy, The Second Front: Inside Asia’s Most Dangerous Terrorist Network (Jakarta: Equinox, 2006).

[21] Atwan, After Bin Laden.

[22] Cragin, “The Challenge of Foreign Fighter Returnees;” Omar Ashour, The De-Radicalization of Jihadists: Transforming Armed Islamist Movements (London: Routledge, 2009); Jean-Pierre Filiu, “The Local and the Global Jihad of al-Qa’ida in the Islamic Maghrib,” Middle East Journal 63:2 (2008): pp. 213-226.

[23] Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, From the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (New York: Penguin Books, 2004).

[24] “The ‘A-Team’ of Islamic Extremists,” Ottawa Citizen, December 31, 1999; “Islamic extremists use Europe as support base,” Calgary Herald, July 30, 1995.

[25] “FactSheet: Steps Taken To Serve Justice in the Bombings of U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania,” U.S. Department of State, August 4, 1999.

[26] United States vs Al Nashiri, CMCR 23-005, United States Court of Military Commission Review, January 30, 2025; Carol Rosenberg, “Alleged al Qaida bomber emerges from CIA shadows, waves,” Miami Herald, March 25, 2016.

[27] Terry McDermott, Josh Meyer, and Patrick J. McDonnell, “The Plots and Designs of al-Qaeda’s Engineer,” Los Angeles Times, December 22, 2002.

[28] Jean-Charles Brisard, Zarqawi: The New Face of Al-Qaeda (New York: Other Press, 2005), pp. 14-26.

[29] Ibid., p. 87.

[30] Cragin, “The Challenge of Foreign Fighter Returnees.” See also Arie Perliger and Daniel Milton, From Cradle to Grave: The Lifecycle of Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2016).

[31] Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler, Then and Now: Comparing the Flow of Foreign Fighters to AQI and the Islamic State (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2016).

[32] “Most suicide bombers in Iraq are foreigners,” Associated Press, June 30, 2005.

[33] For further background on the Islamic State and its origins, see Michael Weiss and Hassan Hassan, ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror (New York: Regan Arts, 2015) and Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, “This is the Promise of Allah,” statement released by al-Hayat Media Center, June 30, 2015.

[34] Karen Parrish, “Stopping flow of foreign fighters to ISIS ‘will take years,’ Army official says,” DoD News, April 6, 2017.

[35] Jyette Klausen, “Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38 (2014): pp. 1-22; J.M. Berger and Jonathan Morgan, “The ISIS Twitter Census: Defining and Describing the Population of ISIS Supporters on Twitter,” Brookings Institution Analysis Paper, No. 20, March 2015; Ali Fisher, “Swarmcast: how jihadist networks maintain a persistent online presence,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9:3 (2015).

[36] For more information, see James Harkin, Hunting Season: James Foley, ISIS and the Kidnapping Campaign that Started a War (New York: Hachette Books, 2015); Seth Loertscher and Daniel Milton, Held Hostage: Analyses of Kidnapping Across Time and Among Jihadist Organizations (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2015); and R. Kim Cragin and Phillip Padilla, “Old Becomes New Again: Kidnappings by Daesh and Other Salafi-Jihadists in the Twenty-First Century,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, September 20, 2016.

[37] Ibid. See also Tucker Reals, “How did ‘Jihadi John’ slip through the cracks?” CBS News, February 27, 2015.

[38] Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Nathaniel Barr, “Recent Attacks Illuminate the Islamic States’ Europe Network,” Hot Issues, Jamestown Foundation, April 27, 2016; Anne Speckhard and Ahmet S. Yayla, “The ISIS Emni: Origins and Inner Workings of ISIS’s Intelligence Apparatus,” Perspectives on Terrorism 11:1 (2017): pp. 2-16.

[39] Ibid.

[40] R. Kim Cragin and Ari Weil, “’Virtual Planners’ in the Arsenal of Islamic State External Operations,” Orbis, February 17, 2018.

[41] “Italy foils IS-inspired plot to blow up Rialto Bridge in Venice,” Times of Israel, March 30, 2017.

[42] “Major Takedown of Critical Online Infrastructure to Disrupt Terrorist Communications and Propaganda,” EUROPOL, June 14, 2024.

[43] Benjamin R. Farley, “The Syrian Democratic Forces, Detained Foreign Fighters, and International Security Vulnerabilities,” Articles of War, Lieber Institute, October 24, 2022.

[44] Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “How Many Fighters Does the Islamic State Really Have?” War on the Rocks, February 9, 2015; Parrish.

[45] Carla Babb, “VOA Exclusive: AFRICOM Chief on threats, way forward for US military in Africa,” VOA News, October 2, 2014; Jeff Seldin, “Key Islamic State planner killed in airstrike, US says,” VOA News, February 11, 2025.

[46] Jeff Seldin, “Foreign fighters flocking to Islamic State in Somalia,” VOA News, November 20, 2024.

[47] Caleb Weiss and Lucas Webber, “Islamic State-Somalia: A Growing Global Terror Concern,” CTC Sentinel 17:8 (2024).

[48] Cecilia Macaulay, “Bilal al-Sudani: US forces kill Islamic State Somalia leader in cave complex,” BBC, January 27, 2023.

[49] Weiss and Webber.

[50] “United Nations Sanctions Monitoring Team Report, S/23/95,” United Nations, February 13, 2023.

[51] “United Nations Sanctions Monitoring Team Report, S/2025/482,” United Nations, July 24, 2025.

[52] Taiwo Adebayo, “Lake Chad Basin insurgents raise the stakes with weaponised drones,” ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies, South Africa, March 17, 2025.

[53] Juana Viúdez, “Detenido en Guadalajara un ‘combatiente terrorista extranjero’ del ISIS reclamado por Marruecos,” Pais, May 16, 2025.

[54] “Major Takedown of Critical Online Infrastructure.” See also Tim O’Connor, “Generating Jihad: How ISIS Could Use AI to Plan Its Next Attack,” Newsweek, September 19, 2025.

[55] “A Prominent Leader Of ISIS, Holds Turkish Citizenship, Arrested In A Joint Turkish-Pakistani Security Operation,” Iraq News Gazette, June 1, 2025.

[56] Ibid. See also “Pro-ISIS Channel Releases New Monero Wallet Address Following Arrest of Alleged Propagandist,” Counter Extremism Project, released by the Targeted News Service, June 10, 2025.

Skip to content

Skip to content