Abstract: In a period of ongoing tensions between the United States and Iran, several practitioners have forecasted Iranian retaliation via proxy group. This article offers a high-level analysis of attack trends from 2008 to 2019 of Iranian proxies in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa, using several open-source datasets. This study separates trends for Lebanese Hezbollah (LH) from other Iranian proxies given LH’s unique partnership and organizational strength relative to other proxies. In a limited capacity, this study also compares and contrasts attacks and fatalities between LH, the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and other non-LH proxies in Iraq and Syria for a handful of years, 2013 to 2019. First, the analysis highlights that LH, other Iranian proxies, and the IRGC entered and exited the Iraqi and Syrian conflict theaters at different times from 2013 to 2019: in Syria, LH-linked attacks preceded those attributed to the IRGC; meanwhile, other proxies focused attacks on the conflict in Iraq more so than in Syria. Second, when looking at the Middle East writ large, LH’s annual attack and fatalities counts at times exceeded all other proxies’ combined, in some years more than four-fold, while proxies and the IRGC had the top annual count twice. Finally, by way of comparison, there are fewer non-LH proxies and attacks in South Asia and Africa, regions where Iranian involvement is less tactical and more strategic, and seemingly managed through LH, formal politics, or other legitimate means, such as religious, educational, or cultural programs.

The January 2020 strike against the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force (IRGC-QF) commander Major General Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi official Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, deputy chief of the Popular Mobilization Commission and Kata’ib Hezbollah commander, immediately raised questions about the implications for Iran’s relationships with its proxies in the region and around the globe. With the subsequent escalation after the strike, it is important to get a better sense of groups that Iran could leverage to retaliate against the United States. Toward that end, having a better sense of past attack trends is useful as they can indicate groups’ capabilities and resiliency and how Tehran may leverage them.

While there are dozens of rich case studies on Iran’s relationships with prominent proxies or their involvement in notable countries, what broad trends are known about their relationships writ large, and how does that inform an understanding of possible paths forward? Particularly, given the new IRGC-QF commander Brigadier General Esmail Qaani’s previous experience in Afghanistan,a a closer look at proxies in that country and other select South Asian countriesb could highlight potential avenues for the IRGC’s paths forward. Against that, this article asks: over the last decade, what were some trends in Iranian proxies’ attacks across different regions, and, where possible to evaluate, how do those compare with the IRGC’s?c

In an attempt to answer these questions, this article looks at recent historical trends in Iranian proxies’ attacksd and fatalities across different regions from 2008 to 2019.e Each section has a short description of past Iranian involvement in that specific region coupled with a short discussion of overarching attack trends. A look at this relatively recent time period provides contextualization for proxies’ activities and group capabilities and possible paths forward. For a more nuanced understanding of Iranian proxy trends, this study parses out Lebanese Hezbollah from other Iranian proxiesf given LH’s long-term partnership and considerable capabilities relative to other proxies. This article focuses on proxies in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africag for a couple of reasons. In Iraq and Syria, Iranian proxies were involved in the fight against the Islamic State for the last several years. With the arrival of Qaani and the drawdown of U.S. troops, there is speculation in the policy community that Iran will turn its gaze to Afghanistan and the broader South Asian region.1 Additionally, policymakers identified Africa as a potential theater for Iran threat network retaliation after the Soleimani strike and scrutinized Iran’s history of involvement on the African continent.2

Before proceeding further, it is pertinent to note this article’s and the datasets’ inclusion criteria and limitations for the attacks and fatalities discussed here.h First, data about groups’ attacks was collected, coded, and analyzed from three databases: the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), and Janes Terrorism and Insurgency Centre’s events database.3 i

Due to strict inclusion criteria,j attacks coded in various datasets are underrepresented due to accessibility to certain areas for journalists during ongoing conflict and violence.4 The author compiled data from multiple datasets in an effort to compensate for this underreporting. Despite this, the numbers presented in this article are likely underestimated, and yet they provide a baseline trend and initial analysis of underlying patterns in attacks.k Relatedly, a second caveat is that the data on the IRGC’s attacks in Iraq and Syria is limited to observed battlefield operations. This does not accurately capture the various dimensions of the IRGC’s involvement, which also operates in an advisory capacity for proxies and therefore may be indirectly involved in some attacks. To provide adequate context, there is discussion of indirect forms of IRGC activities in the background, including establishing, recruiting for, and advising proxies. Third, this study had to reckon with proxies that commit attacks in the context of a governmental security structure. For instance, some of the composite militias in the Hashd al-Shaabi, or the Popular Mobilization Forces that are part of the Iraqi government’s security structure, are Iranian-backed. Attacks from these militias were included in this study if data sources explicitly described them as being perpetrated by the militia outside of its governmental role. Attacks were not included in this study when sources described them as being perpetrated by a “Hashd militia” or with some other reference to their governmental role. For example, the description of a July 10, 2017, attack in Janes dataset states, “In Imam Gharbi, Ninawa province, the 50th Brigade al-Hashd al-Shaabi (Kataib Babylon) killed two Islamic State militants in fighting.” This attack was not included in this study as it was discussed in the context of the group’s official role in the Hashd. It is reasonable to think that the group’s activities in this instance were conducted as part of its role in the Iraqi government. While an artificial difference, this procedure provides consistency for data and hopefully protects from most conflation between group and governmental attacks.

This article proceeds as follows: in the first section, it looks at LH’s, other proxies’, and the IRGC’s attack trends in the Middle East. Next, it extends a view to proxies’ attack patterns in select countries in both South Asia, and the African continent, providing some context for Iran’s relationships with proxies in those regions and potential paths forward.

Regional Analysis of Trends

Middle East: Lebanese Hezbollah, Other Proxies, and the IRGCl

Tehran’s Middle East foreign policy touts long-standing proxy relationships and other activity in Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Iraq, and Syria, all which date back to the 1980s.5

Iran has a long history of supporting militant groups in Lebanon and the Palestinian territories. In Lebanon, Iran established Lebanese Hezbollah (LH) in 1985 and cultivated it into a popular political party and militant organization over time with substantive domestic reach. Supporting LH has provided Tehran with two-fold benefits: (1) an avenue to expand Iran’s regional reach and help build a land and air bridge from Tehran to the Mediterranean;m and (2) a buffer against Israel, a long-time target of its proxy and military strategy. Presently, LH has considerable political and social clout, including seats in the parliament, but the group is seemingly losing popularity.6 As in Lebanon, in the Palestinian territories, Iran also has a history of supporting various militant organizations for the purposes of targeting Israel. These include but are not limited to groups such as Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), and the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade.7 While it could be argued that many of the Palestinian groups operate more as partners than proxies, they are included in this study of proxies due to the extent and long-term nature of support that Iran provided to the groups during the years of this study. For example, Iran was a primary source of weapons and funding for Hamas for most of the years in this study, as well as the main funder of its military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades.8 Similarly, Iran was the main source of funding and training for the PIJ.9

In Iraq, after the 2003 U.S. invasion, Iran’s strategy focused on backing Iraqi politicians and militias as a buffer against a potentially hostile government in Baghdad, U.S. forces on its borders, and Saudi Arabia.10 In addition to politicians, Iran supported Shi`a militias in Iraq, a policy dating back to the Iran-Iraq war, and, over time, added more groups to its roster. Presently, Iran supports some of the most influential militia groups in the Hashd al-Shaabi, or the Popular Mobilization Forces, which are part of the Iraqi government’s security structure.11 As Michael Knights has noted in this publication, Iran’s proxies in Iraq reached “unprecedented size and influence” in late 2019.12 Iranian dominance in Baghdad was contested domestically in October 2019, and the Iran-backed militias’ repressive crackdown further eroded their support.13

Turning to Syria, Iran’s proxy network extended into the country prior to the civil war.14 Just before the conflict’s outbreak, Tehran launched a multi-pronged foreign policy to assist the Assad regime,15 such as sending in IRGC and Iranian army forces in an advisory capacity to train the Syrian military and transport supplies from Tehran.16 Another pillar included raising new and bolstering existing militias and other non-state violent organizations in the country. Toward the latter, Ariane Tabatabai wrote in this publication that the Fatemiyoun Brigade,n for example, was established under the guidance of the IRGC-QF in 2012 and was intended to serve as an affordable means of Iranian support to the Assad regime: “fighters would be paid a few hundred dollars per month and promised residency rights to essentially serve as cannon fodder for Iran’s efforts in Syria.”17

In Syria, in addition to raising militias, Iran also directed LH’s and proxies’ fighters from Lebanon and Iraq, respectively. In 2012, both LH and Iraqi proxies began moving forces into Syria.18 Those from Iraq included Iranian-backed militias within the Hashd al-Shaabi, such as Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq19 and Harakat al-Nujaba.20 In addition to forming militias, Iran also worked with existing militias in Syria, such as Al-Ghaliboun, among several others.21 LH was also pivotal in training pro-regime militias22 and establishing several Iranian-supported militias in Syria, for example Quwat al-Ridha,23 one of the groups that is now part of the Syrian Hezbollah groups.24 The salary incentives and recruitment strategies used for the Fatemiyoun Brigade were also employed for other proxies operating in Syria, such as the Zeinabiyoun Brigade25 o and Kata’ib Aimmah al-Baqiyah (a Syrian Shi`a Iranian-backed militia).26 The IRGC-QF also incentivized recruitment for other Syrian proxies, paying directly from its coffers or through Iraqi proxy intermediaries.27

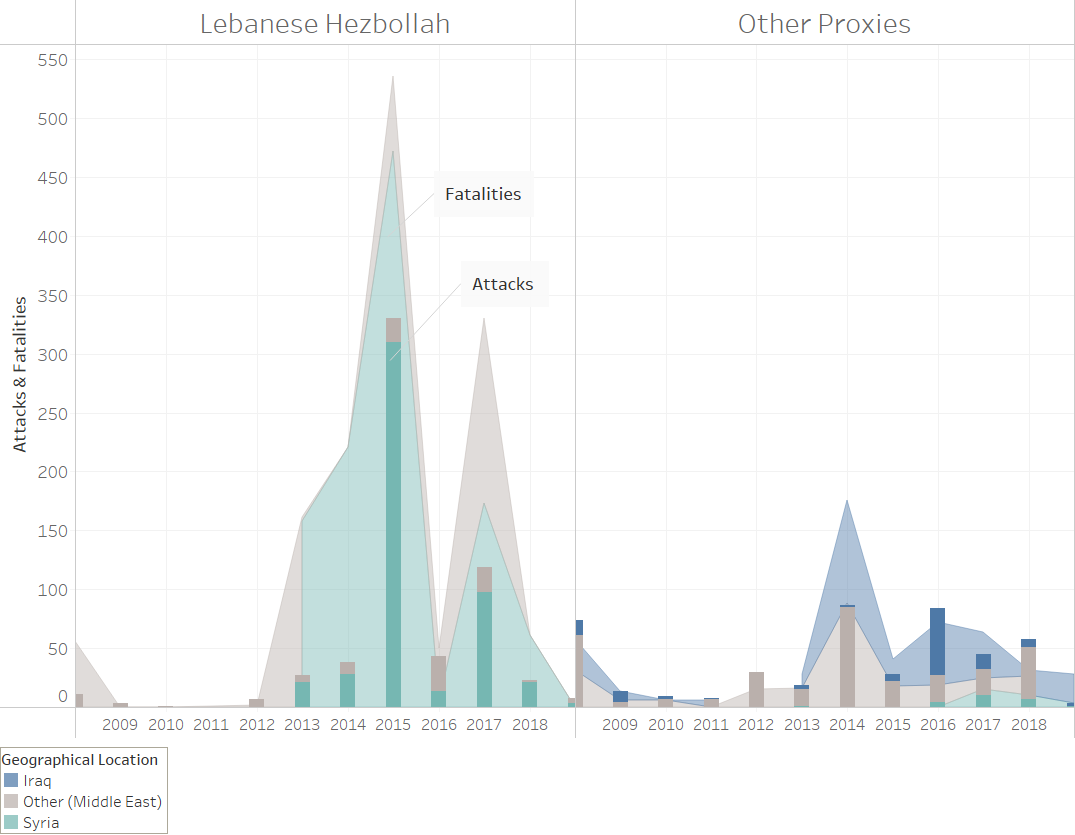

Figure 1 depicts LH’s and other proxies’ attacks in various Middle Eastern countries, as observed by the datasets used in this study. The countries are grouped into three categories: Iraq, Syria, and other Middle Eastern states, including Bahrain, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and Gaza Strip, and Yemen.p The bars reflect total attacks per year, parceled by different geographical category. (For example, in 2015, there were roughly 300 LH-linked attacks in Syria and about 20 in other Middle Eastern countries.) The shaded portions behind the bars are the total fatalities per year, categorized by geographical location. (For example, in 2015, of the approximately 525 LH-linked fatalities, about 450 were in Syria and the rest in other Middle Eastern countries).

An initial review of attacks and fatalities for LH and other Iranian proxies in the Middle East provides a not altogether surprising observation: there is a stark difference between LH’s and other proxies’ attacks patterns. A couple temporal trends are notable. After the civil war started, LH continued attacks outside of the Syrian theater, but to a lesser extent. Over the same period, proxies’ attacks are seemingly split between Iraq and other Middle Eastern countries, with some attacks in Syria at the end of the time period. The year 2014 is notable, as much of other proxies’ activity outside Iraq reflected the events of the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict and a series of Saraya al-Ashtar and Saraya al-Mukhtar bombings in Bahrain.28

The extent to which LH’s operational capacity outdoes the other proxies is consequential: in 2015 and 2017, LH-inflicted fatalities were more than quadruple that of the proxies in the same years. Relatedly, in 2013 and 2014, when LH had fewer attacks than the other proxies, it still was responsible for a considerable number of fatalities. Put differently, LH seems substantially more active than the proxies in some years, based on the volume of attacks, and relatively lethal in the years when it had fewer attacks. A similar trend holds when narrowing the scope to attacks and fatalities in only Iraq and Syria for 2013-2019.

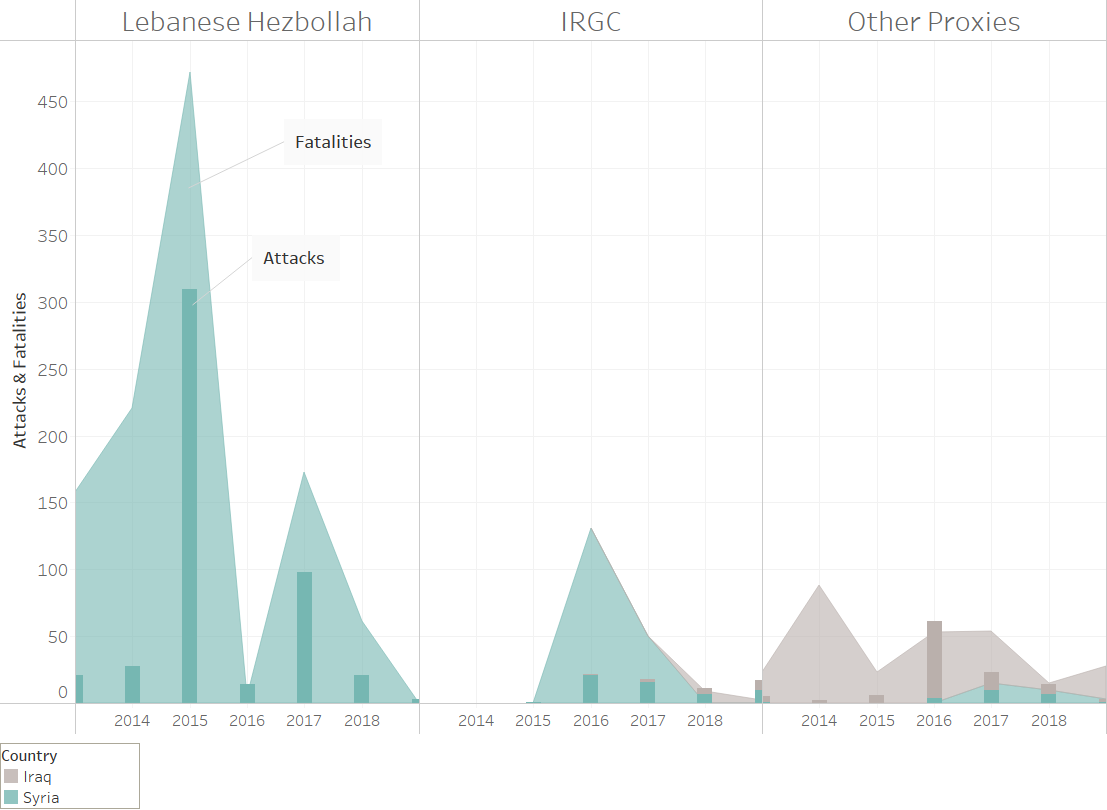

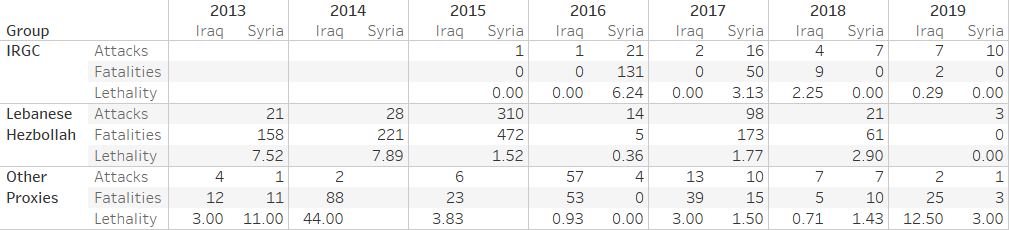

Figure 2 juxtaposes annual attacks and fatalities for LH, the IRGC, and other proxies from 2013 to 2019 in Syria and Iraq, and Table 1 provides specific counts for these measures as well as one for overall annual lethality, calculated by the total number of fatalities divided by the total number of attacks.

From this data, it is apparent how entities differ in operational activities. The timing and location of operations for each entity is noteworthy. First, both Lebanese Hezbollah and other Iranian proxies had identifiable attacks ahead of the IRGC in Syria and Iraq, respectively. Turning first to Syria, given what is known about the IRGC’s involvement in the country prior to the civil war, it seems likely that the Revolutionary Guards were operational before 2015, the first year it had an observed attack. Furthermore, over the entire period, LH and the IRGC’s identified attack activity seem constrained to Syria almost exclusively. IRGC attacks’ lethality in Syria peaked in 2016, as Iran committed more personnel to the conflict and transitioned from a training role to a tactical one.29 Non-LH proxies began launching attacks in Syria from 2016 onward. Conversely, in Iraq, non-LH proxies were active since 2013 and overlapped with IRGC from 2016 onward. The proxies’ attack counts often surpassed the IRGC’s, except in 2019 when the Revolutionary Guards had the top count. The first IRGC attack in the dataset is registered in 2016, but IRGC forces were operational in Iraq since 2014, in response to the Islamic State threat.30

LH and the other proxies were operational in different contexts when looking at Iraq and Syria more closely. From 2014 to 2016, LH almost exclusively focused on Syria while other Iranian-backed proxies did so in Iraq. While it may be that the two entities were acting accordingly due to their primary locations of operations, some Iranian direction is likely given Soleimani’s role in cultivating the proxy network and hands-on approach in conflict theaters in Iraq and Syria, among other Middle Eastern countries.31

Each entity had points of heightened lethality but at somewhat diverging time periods and locations. In 2013 and 2014, both LH and the other proxies had a spike in the fatalities they inflicted in Syria and Iraq, respectively. (See Figure 2 and Table 1.) From 2017 onward in Syria, Lebanese Hezbollah and the other proxies, to a lesser extent, resumed predominance in attacks. LH’s operations also levied substantial fatalities in 2017 but had a downturn in 2018.32

When LH-inflicted fatalities dipped in 2016 in Syria, IRGC forces peaked in fatalities for a relatively low number of attacks. There may be a couple potential explanations for the surge of IRGC-linked fatalities in 2016. The IRGC participated in various campaigns in the Aleppo governorate and the Battle of Aleppo alongside LH, Harakat al-Nujaba (an Iraqi Iranian-backed militia), and other pro-Assad forces to retake the city.33 Relatedly, IRGC forces shifted tactics the previous year, the effects of which may have been felt in 2016. In part informed by Russian military campaigns, starting in late 2015, IRGC ground forces and Quds Force fighters “began launching simultaneous and successive operations against opposition-held districts in and around Aleppo.”34 The uptick in the number of campaigns could entail higher casualties for both the Revolutionary Guard forces and those targeted, and both indicators are included in the fatalities counts for this study.35

From 2016 to 2019, all three entities—LH, the IRGC, and the non-LH proxies—overlapped operations in Syria. IRGC forces often fought alongside Iranian-sponsored proxies in Iraq and Syria. There were a series of co-operational attacks leading up to the Battle for Aleppo.36 Relatedly, there are several instances of joint operational bases shared by the IRGC and proxies’ forces. According to the data collected for this study, between 2016 and 2019, there were approximately 20 cases, or observations, of such joint base of operations between the IRGC, LH, and the Fatemiyoun Brigade.q

The data trends fit with open-source reporting. Iranian involvement in Syria—through the IRGC, Quds Force, and the Iranian army—was primarily in an advisory capacity, which correlates with the relatively low-level number of attacks and fatalities inflicted by the IRGC in Syria throughout the time period.37 Similarly, IRGC forces were active in a training and advisory capacity with Iraqi proxies,38 which is consistent with the Revolutionary Guards’ identifiable attacks only gathering pace from around that point. (See Table 1.) The data suggests the IRGC had an operational shift in Syria between 2015 and 2016: it went from one attack in 2015 to about 20 attacks and over 100 fatalities in the next year.r The trends in Table 1 match with open-source reports about the IRGC moving forces from various branches, including some from the domestic-facing Basij, into Syria between 2014 and 2015 to fight alongside LH and other proxies.39 Consequently, Revolutionary Guard forces faced devastating losses in May 2016 in Syria and afterwards seemingly reduced troop deployments to Damascus.40 Despite these reductions, there continued to be rising IRGC-related attacks and fatalities in both Syria and Iraq.

These trends have some implications for those concerned by Iran’s threat network. First, it may be that Iran continues to leverage LH’s operational strength in Syria in the future. Particularly with the drawdown of the Syrian civil war and the Islamic State’s contraction, Iran may shift away from active operational support and once again inhabit a strictly advisory role with the Assad government, much like it did at the onset of the conflict, maintaining forces at Syrian bases for training and logistics. On many occasions, LH has acted as a broker for Tehran in Syria: it established proxies, provided them with various forms of tactical support, and recruited with and for them.41 In the post-Soleimani era, as far as has been reported in open-source research, it seems IRGC-QF Commander Brigadier General Esmail Qaani travels abroad to meet with operational partners to a lesser extent than his predecessor, with, as far as is known from open source reporting, the most recent travel to Iraq and Syria in March 2020.s While it may be too soon to tell, this could signal a change in operational security for the Quds Force. If so, LH would be a natural intermediary in Syria or Iraq.42

Yet, this possibility comes with some drawbacks. LH may at times be disinclined to be considered Iran’s lackey. The group continues to face growing public discontent in Lebanon, tensions that have been somewhat exacerbated by Hezbollah’s public services shortcomings during the COVID-19 pandemic.43 Additionally, Iran’s economic hardships because of the pandemic could also have implications for Hezbollah’s budget,44 though there is not yet evidence to suggest this is the case. Yet, put together, these factors may contribute to contention between LH and Tehran.

Proxies in South Asia

Having reviewed overarching trends in Hezbollah’s and other proxies’ activities in the preceding section, there are some similarities and differences with Iran’s proxy policy and proxies’ operations in select South Asian countries, namely Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Much of Iran’s involvement in the region is directed toward and in Afghanistan.

Iran’s involvement in South Asia is of importance given its shared border with Afghanistan. It may have an opportunity to strengthen its position in Afghanistan because of several factors. First, the initial drawdown of U.S. troops to 8,600 in Afghanistan47 and the peace process with the Taliban create an opportunity upon which Iran can capitalize. Second, Soleimani’s replacement, Brigadier General Esmail Qaani, has about two decades of experience overseeing the IRGC-QF’s operations in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia more broadly.48 Additionally, Qaani’s second-in-command, Brigadier General Seyyed Mohammad Hejazi, has decades of experience in several IRGC organizations: directing the forces in Lebanon, research and development of weapons, and commander of the IRGC’s domestic-facing organization, the Basij.49 Taken together, Qaani’s network coupled with Hejazi’s versatility creates opportunities for Iran to expand its influence in Afghanistan and its neighboring countries.

Presently, as in Iraq and Syria, Tehran’s involvement in Afghanistan is multidimensional: (1) it did and continues to support local organizations to compete with foreign influence in its eastern neighbor, whether Soviet/Russian, Saudi, or American; and (2) it recruited fighters from Afghanistan and the region for operations elsewhere.50 With regard to the first dimension, like in Iraq, the Islamic Republic’s involvement in Afghanistan dates to the 1980s.51 At the time, Iran cultivated and supported a contingent of mostly Hazara, a marginalized Shi`a minority, political-militant organizations, commonly referred to as the “Tehran Eight.”52 It continues to support some of those groups, like Hezb-e Wahdat to the present, but not all Hazara politicians are eager to work with Iran.53 Additionally, much like its motivations in working with Palestinian organizations, Iran leveraged overlapping goals with Sunni-Islamist militant organizations in Afghanistan. It supported al-Qa`ida and the Taliban intermittently after 2008.54

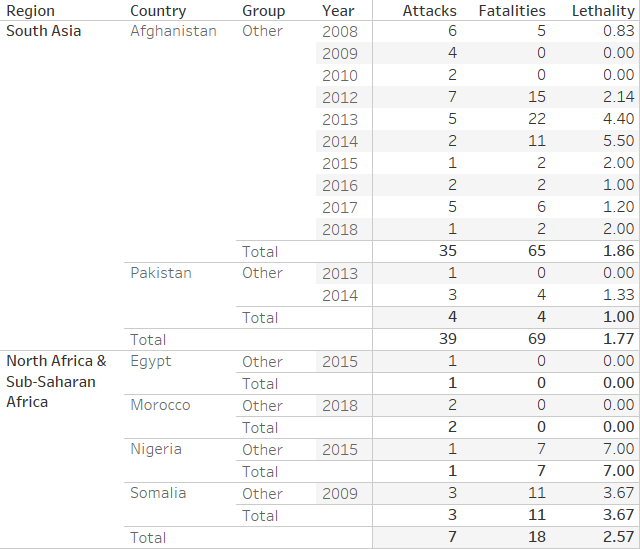

With regard to the second dimension, in addition to working with local organizations, Iran has also used Afghanistan as a recruitment ground for various militant organizations. In the early days of the Iran-Iraq War, Iran recruited Afghan Hazara fighters, to the Abuzar Brigade, to fight on the side of the Iranians.t More recently, Iran recruits Afghan fighters to the Fatemiyoun Brigade and other Syrian-based militias out of centers in Herat and Kabul, as well as through IRGC-Basij offices in Iran, offering a salary and Iranian citizenship in exchange for several months of fighting in Syria.55 Overall, Iran seemingly tends toward more operational partners in Afghanistan than in Pakistan. Iranian proxy attacks in South Asia have almost exclusively been in Afghanistan, with a handful in Pakistan. (See Table 2.) The data implies that Iranian proxies in Afghanistan are steadily active when it comes to launching attacks in the last decade. In some years, these groups were as active as proxies in Iraq. (See Tables 1 and 2.)

In contrast to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, Iran’s involvement in Pakistan is abstruse but governed by two pillars: one part focuses on soft-power involvement in the Shi`a religious establishment in Pakistan while a second part focuses on recruitment to the Zeinabiyoun Brigade. Toward the first part, Tehran set up religious schools for Shi`a in the country after the Iranian Revolution to garner support among sectarian kin.56 Pakistan has one of the largest Shi`a populations outside Iran.57 Regarding the second part, the IRGC used recruitment programs in Urdu to enlist fighters in the Zeinabiyoun Brigade.58 It also solicited the support of Pakistani Shi`a clerics to legitimize its activities,59 and offered recruits a substantial salary in exchange for several months of commitment to fighting on Iran’s behalf.60

Like in Pakistan, Iran’s involvement with proxies in India is equally obscure. Iran has worked with partners on the ground in India, but does not have proxies, such as in the sense of the Fatemiyoun Brigade. Through Anjuman-e Haidari in New Delhi, thousands of India Shi`a have signed up to fight against the Islamic State and in defense of Shi`a holy sites,61 though is not clear how many went on to fight.62 Separately, Iranian propaganda lines some streets of Central Kashmir, including billboards of Ayatollah Khomeini and martyred IRGC officers.63 Some attest that Iranian propaganda is geared toward pushing Shi`a in Kashmir to be pro-separation to leverage pressure on New Delhi.64 While the IRGC’s direct involvement in India is seemingly limited, there have been allegations of the Revolutionary Guards’ culpability in attacks in the country. In February 2012, a motorcyclist placed a magnetic “sticky bomb” on the side of an Israeli diplomatic vehicle in New Delhi, and the explosion severely injured the car’s occupants, including the Israeli defense attaché’s wife.65 The subsequent investigation of this 2012 attack revealed potential connections to the IRGC, which Tehran denied.66

Proxies in Africa

Policymakers and researchers have also considered an Iranian retaliation on the African continent.67 Iran’s proxy activity in Africa is difficult to track as much of it is completed covertly through Hezbollah or the IRGC-QF. The Quds Force has directorates on the continent,68 and like in India, many Iranian-linked activities in Africa have been navigated through Hezbollah. Its influence is notable in Nigeria, Morocco, and the Central African Republic but visible in other countries as well.

Iran has a storied involvement with Shi`a in Nigeria, dating back to the Iranian Revolution.69 More recently, Iran developed a relationship with the Islamic Movement in Nigeria (IMN).70 Like LH, in addition to launching attacks, IMN also had a number of educational and communications outreach programs.71 Both the IRGC and Hezbollah are involved in activities in Nigeria, of varying overtness and legality.72 Hezbollah operatives have been suspected of money laundering, drug trafficking, and weapons smuggling in Nigeria through corporations and car dealerships.73 More recently, Iran directed Hezbollah to train more Nigerians in the hope of eventually utilizing Nigeria as a base to launch attacks against Western and Israeli targets.74

Iran’s involvement on the African continent extends beyond Nigeria. There are several reports of Hezbollah and the IRGC smuggling weapons and drugs across the African continent into nearby regions, like Europe.75 The IRGC’s alleged funding, training, and weapons support for the Polisario Front76 in Morocco through the Iranian embassy in Algeria resulted in Rabat severing ties with Tehran.77 u Many instances of Iranian support in Africa are clandestine. Last year, the Quds Force supported the establishment of Saraya Zahara in the Central African Republic to attack U.S. interests in Chad, Sudan, and Eritrea.78 Conversely, toward more legitimate activities, Iran also has cultural centers in some African countries, such as Sierra Leone and Tanzania.79

When reviewing Table 2, Iranian proxies’ attacks in Africa are few and far between in terms of location and volume. In this region, while attacks can serve as a useful metric, they provide a limited view of Iranian proxy activity in Africa. The low number of proxy attacks on the continent does not necessarily equate with little Iranian-linked activity. As demonstrated in other theaters, such as Syria, Iran has worked with local partners, such as non-profits and businesses, toward soft power initiatives, a pattern that holds some credence in Africa.80 Together, these factors indicate a need to potentially adjust the metrics used to study Tehran’s involvement on the continent, which will be discussed further in the concluding remarks.

Conclusion

This piece is an exploratory endeavor in studying high-level trends in Iranian proxies’ and Lebanese Hezbollah’s attacks over the last decade. Using several open-source dataset sources, this article reviews attack and fatalities patterns for Iranian proxies and Lebanese Hezbollah from 2008 to 2019 in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa. This study also compiles data related to IRGC attacks to compare trends against LH and other non-LH proxies in Iraq and Syria for several years (2013 to 2019). While the potential for underreporting is prevalent for open-source datasets, there are a few trends that are notable. First, LH, Iranian proxies, and the IRGC conducted attacks in the Iraqi and Syrian conflict theaters at different points between 2013 to 2019: LH attacks preceding the IRGC’s observed attacks in Syria while proxies focused on the conflict in Iraq more so than in Syria. Second, when looking at the Middle East overall, Hezbollah’s annual attack and fatalities counts often exceeded all other proxies’ combined—in a couple years, more than four-fold. Finally, Iranian involvement is seemingly managed through Hezbollah and the IRGC, or through legitimate means such as formal politics or cultural programs in parts of South Asia and the African continent, regions with fewer overall proxies.

Looking beyond the trends noted in this article, there is a need to consider potential consequences of the shifting conflict with the Islamic State. It is important to consider the future of the forces Iran propped up in Syria, namely the Fatemiyoun and Zeinabiyoun. Some analysts warn of the potential for the Fatemiyoun to be deployed to Afghanistan to secure Iranian interests, potentially from adversaries such as the Islamic State Khorasan affiliate, which operates in Afghanistan and Pakistan.81 In the past few years, many former Fatemiyoun fighters have resettled in Herat province, but Kabul has asked Tehran to keep former fighters from the group in Iran.82 Yet, as previously discussed in this study, the drawdown of U.S. troops coupled with Qaani’s previous experience in the country could potentially create an opportunity for Iran to utilize the Fatemiyoun in Afghanistan. It does not seem likely that the Zeinabiyoun will be employed in a similar way in Pakistan. Differences in foreign policy history may account for this: while Iran has a long-standing policy of direct involvement in Afghanistan, its involvement in Pakistan is less clear.83

While the trends outlined in this piece are interesting, they have limitations, and there are several avenues for improvement and further exploration. First, there are some data limitations in understanding Iranian proxies’ operations in different regions. This is rooted in fundamental differences in Iranian proxy policy across regions. In addition to open-source datasets, Iranian proxy trends in parts of South Asia and on the African continent should be studied using different metrics. One avenue would be to track proxies’, LH’s, and the IRGC’s plots, arrests, and possibly open criminal investigations (e.g., through court cases and documents) to provide a more nuanced understanding of Iranian involvement in different regions, and it would provide a baseline to understand upsets in the Iranian threat network. In a similar vein, tracking proxies’ non-violent activities, such as construction projects, schools, and social service provisions, among others, could provide a better understanding of Iranian soft power in the South Asian and African regions reviewed in this study. A separate but related approach could be to expand the understanding of what constitutes an Iranian “proxy” to include local businesses, non-profits, and other legitimate entities that cooperate with various elements of the Iranian state. Each of these indicators can be studied through open-source research, though may be prone to under- or over-reporting based on newsworthiness and/or observability. Relatedly, these metrics could similarly be applied to understand LH’s activities in other regions. During the time period of this study, the group launched an attack in Bulgaria and attempted one in Thailand, among other countries, some of which also had potential IRGC involvement. 84

Relatedly, this article does not study South America or Central Asia, two regions with a nebulous history of Iranian involvement. Toward the former, in parts of the South American region, Tehran’s influence is often outsourced through Lebanese Hezbollah, fueled by the narcotics trade, and propped up by local governments, such as Venezuela.85 More specifically, in the tri-border area, between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, some scholarship has demonstrated clear indications of operational activity through IRGC and LH as well as violent and non-violent non-state entities.86 By extending the study to Hezbollah-related plots or arrests or to non-violent proxies, it would provide a gradation of understanding Iranian influence in both South America and Central Asia. Toward the latter, the IRGC-QF also has a directorate dedicated to the region.87 Tehran has some economic and cultural ties to Central Asia, more recently around the Chabahar transit corridor.88 CTC

Nakissa Jahanbani is an instructor and researcher at the Combating Terrorism Center. Her current project studies the evolution of Iran’s relationship with its proxies in Syria and Iraq. A separate vein of her research studies states’ support of terrorist and insurgent organizations. Follow @nakissapjahan

Substantive Notes

[a] Qaani is also said to have had considerable engagement in Afghanistan and previous experience in Pakistan and some of Central Asia. For more information, see Ali Alfoneh, “Esmail Qaani: the next Revolutionary Guards Quds Force commander?” American Enterprise Institute, January 11, 2012; Ali Alfoneh, “Who Is Esmail Qaani, the New Chief Commander of Iran’s Qods Force?” Washington Institute, January 7, 2020.

[b] For the purposes of this study, Afghanistan is considered part of South Asia.

[c] Data about the IRGC was only available in the ACLED and Janes datasets from 2016-2019. (See subsequent footnotes for datasets’ specifics.) Due to the limitations of available quantitative data about the IRGC’s activities, it was challenging to parse out IRGC-QF attacks from those in other branches of the Revolutionary Guards. Sometimes data sources would not distinguish between which IRGC forces were involved in the attacks. Some of the data used in this article concerns IRGC-QF attacks, but it includes those from other IRGC armed forces as well. Therefore, for accuracy, this data in this piece concerns IRGC forces broadly, which can include the IRGC-QF, IRGC military, or, in very limited instances, the IRGC’s Basij militia. This does not, however, include forces from the Iranian military (artesh) that are also found in Syria. For more information, see “Chapter One: Tehran’s Strategic Intent,” in “Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019.

[d] This article defines a terrorist attack as an event in which “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.” From “Global Terrorism Database Codebook,” p. 10. Attacks used in this dataset include both completed and not completed attacks. For more information, see “Global Terrorism Database Codebook.”

[e] For the purposes of this article, proxies are groups that receive operational, tangible support from any aspect of the Iranian government. Inclusion criteria for Iranian proxies in this article comes from several sources. First, inclusion is based on the author’s ongoing project at the Combating Terrorism Center regarding Iranian proxies in Iraq and Syria. Second, it includes Iran’s sponsorship relationships delineated in the Big Allied and Dangerous (BAAD) Project. See the following versions for more information: Victor Asal, R. Karl Rethemeyer, and Eric W. Schoon, “Crime, Conflict, and Legitimacy Trade-Off: Explaining Variation in Insurgents’ Participation in Crime,” Journal of Politics 81:2 (2019); Victor H. Asal and R. Karl Rethemeyer, “Big Allied and Dangerous Dataset Version 2,” START, 2015. Additional proxies were included on a case-by-case basis with information collected from open sources. In evaluating proxies’ attacks patterns, it is important to evaluate which groups are proxies versus non-state partners. For the purposes of this study, proxies are groups that have some level of dependence on Iranian support or direction. It could be argued that some groups commonly referred to as Iranian proxies would be better described as partners based on the extent and nature of their relationship with Iran and the groups’ relative autonomy and strength. For this reason, groups like the Taliban and al-Qa`ida are not included in this study. First, Iran’s relationship with the Taliban is strategically leveraged at certain times and not consistent across the time period. For more information on the nature of Iran’s relationship with the Taliban during this time period, see Scott Worden, “Iran and Afghanistan’s Long, Complicated History,” United States Institute of Peace, June 14, 2018; Alireza Nader, Ali G. Scotten, Ahmad Idrees Rahmani, Robert Stewart, and Leila Mahnad, “Iran’s Influence in Afghanistan,” RAND, 2014; “Chapter 3: State Sponsors of Terrorism,” Country Reports on Terrorism, U.S. Department of State, 2012. Second, Iran’s relationship with al-Qa`ida is similarly inconsistent across the time period and ranges from tactical to operational support. For more information on Iran’s relationship with al-Qa`ida, see Assaf Moghadam, “Marriage of Convenience: The Evolution of Iran and al-Qa`ida’s Tactical Cooperation,” CTC Sentinel 10:4 (2017); Nelly Lahoud, “Al-Qa’ida’s Contested Relationship with Iran: A View from Abbottabad,” New America, September 7, 2018.

The data was compiled from 2008 to 2019 for a couple of reasons. When this research project started in February 2020, and there was concern about incomplete attack data for the last quarter of 2019. As the project sought to review an entire decade, 2008 to 2018 was selected as a time period. Later, as datasets were updated, data on attacks in last quarter of 2019 were collected in April 2020 and subsequently included in this study.

[f] The non-LH proxies included in this study are: Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, Al-Shabaab al-Mu’minin, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, Badr Brigades, Brigade of al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi, Fatemiyoun Brigade, Hamas (Islamic Resistance Movement), Harakat al-Nujaba, Harakat-e Islami, Hezbi Islami, Hezbollah, Hizb-e Wahdat-e Islami, Islamic Court Union, Islamic Movement in Nigeria, Kata’ib al-Imam Ali, Kata’ib Hezbollah, Kata’ib Jund al-Imam, Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada, Mahdi Army, Mukhtar Army, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), Polisario Front, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Gen Cmd (PFLP-GC),Saraya al-Ashtar Saraya al-Mukhtar, Saraya Al-Muqawama al-Shabeea, Saraya Waad Allah, Sipah-I-Mohammed, and Waad Allah Brigade.

[g] It is important to delineate regional categories of the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa for this study. Below is a list of the countries in each region. This is not an exhaustive list of countries in each of these regions: for succinctness, only those countries that have at least one attack in the dataset are listed here. The Middle East consists of Bahrain, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and Gaza Strip, and Yemen; South Asia consists of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India; Africa consists of Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria, and Somalia.

[h] Fatalities counts are compiled from the three data sources mentioned in this study. They include the total number of reported fatalities in each attack, whether civilian, security forces, or perpetrator.

[i] Data for this article was only gathered from the aforementioned datasets. Additional open-source research and coding was not completed to verify what was collected from the three datasets. This likely contributes to underreporting attacks as well. Attacks information was gathered from 2008-2018 (and, where available, 2019) for groups that received Iranian sponsorship at any point for any duration during that time period, with two exceptions: Taliban and al-Qa`ida (discussed in footnote E). Data from the GTD is from 2008-2018, and data from ACLED and Janes is collected from the year available until 2019. Data on the specific entities was first pulled from the GTD and ACLED. Months in which there was a gap in data in those sources were then searched in Janes. Data from ACLED and Janes was then coded according to GTD’s attack coding scheme. (See the GTD Codebook for specifics.) After compiling from different datasets, observations were reviewed to ensure duplicate events across databases were not included.

[j] All three datasets collect from secondary sources. There is a potential selection effect in the data compiled for this study since these datasets have already denoted the attacks’ importance. Attacks coded in the GTD must meet two sets of criteria. First, attacks must (a) be perpetrated by sub-state actors, (b) demonstrate intentionality on part of the group, and (c) have a level of violence or immediate threat of it. Second, two of three of the following criteria should be met for inclusion: (a) the goal of the event is for political, economic, religious, or social reasons, (b) the event must have evidence of signaling a message, coercion, or intimidation of a larger audience, or (c) the event must be outside the realm of legitimate warfare activities. See “GTD Codebook, p. 10.” ACLED collects data from media; research and investigative reports; local partners; and specific social media accounts and channels. For more information, see “Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Codebook,” ACLED, 2019. Examples of violent event types included from ACLED are: battles, armed clashes, use of force against civilians, and abductions. There is a potential selection effect in the data compiled for this study: these sources have already denoted events’ importance. This dataset adds gradations of violent events to the present study, including but not limited to battles, armed clashes, use of force against civilians, and abductions. Attacks from Janes Terrorism and Insurgency Centre’s Events dataset are coded from open sources. For more information, see “Terrorism and insurgency” on the Janes website.

[k] Events from ACLED and Janes also covered “clashes” or “battles” that were ongoing. For multi-day clashes, the author coded a new attack for each day of the clash if the attacks took place in different locations (at the city level). For these types of events, the lowest fatalities count found was coded.

Data was extracted for the groups’ names from ACLED’s “actor1” category and GTD’s “gname.” From Janes, the primary targeting force was coded from attack descriptions. These categories reflect that the group in question was the primary targeting force. For standardization purposes, co-operational attacks were coded under the primary targeting group. While this may also contribute to some underreporting, this standardization hopefully protects from most data conflation issues.

[l] The Houthis, or Ansar Allah, are not included in this study. Given their focus and position in Yemen, the Houthis have considerable strength and autonomy. Iran and the Houthis coordinate an overall tactical and target strategy with the Houthis, per Nader Uskowi, Temperature Rising: Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and Wars in the Middle East (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield), p. 28. With this, it may be more appropriate to consider the group an Iranian non-state partner as opposed to a proxy. As the Houthis are not included in this study, Iranian involvement in Yemen is also not discussed. This is not to dismiss the importance of Iran’s policies and involvement in Yemen. For more information about this relationship and history, see Michael Knights, “The Houthi War Machine,” CTC Sentinel 11:8 (2018); Marieke Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen: A History of the Houthi Conflict (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); and Gerald M. Feierstein, “Iran’s Role in Yemen and Prospects for Peace,” Middle East Institute, December 6, 2018.

[m] The land and air bridge generally refers to various routes potentially connecting Tehran to the Mediterranean, which run through various points in Iraq, Syria, and, in some routes, Lebanon. Through these routes, Iran can equip proxies throughout Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, and exert other forms of influence, such as various soft-power initiatives in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor province. For an excellent background and analysis about the land and air bridge, see David Adesnik and Behnam Ben Taleblu, “Burning Bridge: The Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean,” Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, June 2019. For more information about Iranian soft power influence in the Syrian Deir ez-Zor province, see Oula A. Alrifai, “What Is Iran Up To in Deir al-Zour?” Washington Institute, October 10, 2019.

[n] The Fatemiyoun Brigade recruits from and is largely populated by an Afghan Shi`a minority, the Hazara. For more information about this group and its history, see Tobias Schneider, “The Fatemiyoun Division: Afghan Fighters in the Syrian Civil War,” Middle East Institute, October 2018.

[o] The Zeinabiyoun Brigade is a Pakistani Shi`a militant organization operating in Syria. The IRGC supports the group in recruitment and training in Pakistan and Iran and subsequent transportation to Syria. For more information, see Antonio Giustozzi, “The resurgence of Shia Muslim militancy in Pakistan,” Janes Terrorism & Insurgency Monitor, October 27, 2016.

[p] Data on Houthi attacks is not included in this figure. Please refer to footnote L for a description of why the Houthis were excluded in this study.

[q] The data on joint bases of operation was collected from the ACLED dataset primarily and is coded from its “strategic developments” category. This data was also supplemented from the Janes dataset used in this study.

[r] IRGC attacks were first captured in the database in 2016. Per footnote J, attacks can include armed clashes, violence against civilians, and abductions.

[s] Qaani met with Iraqi militia group leaders and Hamas leadership in the days after Soleimani’s death in Iran. Adam Rasgon, “Hamas chief meets slain Iranian general’s successor in Tehran,” Times of Israel, January 6, 2020; Crispin Smith, “After Soleimani Killing, Iran and Its Proxies Recalibrate in Iraq,” Just Security, February 27, 2020. In March 2020, Qaani traveled to Baghdad. For more information, see Qassim Abdul-Zahra and Samya Kullab, “Iran general visits Baghdad, tries to forge political unity,” Associated Press, April 1, 2020, and Sina Farhadi, “Qaani visits Syria frontlines as Iran-backed militias continue to lose fighters,” Al-Mashareq, March 27, 2020.

[t] Former fighters of this group went on to compose the leadership of the present-day Fatemiyoun Brigade. See the following sources for more information: Ariane Tabatabai, “After Soleimani: What’s Next for Iran’s Quds Force?” CTC Sentinel 13:1 (2020); Farzin Nadimi, “Iran’s Afghan and Pakistan Proxies: In Syria and Beyond?” Washington Institute, August 22, 2016; Mahtab Divsalar, “Fatemiyoun’s Future Home: Syria, Iran or Afghanistan?” Radio Zamaneh, April 20, 2019.

[u] According to some sources, Hezbollah may also be providing support to the Polisario Front. For more information, see “Iran denies supporting Polisario after Morocco severs ties,” Associated Press, May 2, 2018.

Citations

[1] Ariane Tabatabai, “After Soleimani: What’s Next for Iran’s Quds Force?” CTC Sentinel 13:1 (2020); Arwa Ibrahim, “Esmail Qaani: New ‘shadow commander’ of Iran Quds Force,” Al Jazeera, January 20, 2020; Kenneth Katzman, “Iran’s Foreign and Defense Policies,” Congressional Research Service, April 29, 2020; Aveek Sen, “Iran looks to Chabahar and a new transit corridor to survive US sanctions,” Atlantic Council, June 19, 2019.

[2] Salem Solomon, “As Iran Looks to Hit US Interests, it May Turn to Africa,” Voice of America, January 4, 2020; General Stephen J. Townsend, “United States Africa Command and United States Southern Command,” Testimony, Senate Armed Services Committee, January 30, 2020, pp. 79-80.

[3] National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), University of Maryland, 2019, The Global Terrorism Database; Clionadh Raleigh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen, “Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data,” Journal of Peace Research 47:5 (2010): pp. 651-660; Janes Terrorism and Insurgency Centre’s events dataset.

[4] For a good discussion of underreporting in terrorism research, see Joseph K. Young, “Measuring Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 31:2 (2016): p. 328.

[5] Nakissa Jahanbani, “Beyond Soleimani: Implications for Iran’s Proxy Network in Iraq and Syria,” CTC Perspectives, January 10, 2020; Phillip Smyth, “The Shiite Jihad in Syria and Its Regional Effects,” Washington Institute, February 2015; Claire Parker and Rick Noack, “Iran has invested in allies and proxies across the Middle East. Here’s where they stand after Soleimani’s death,” Washington Post, January 3, 2020; Ali Soufan, “Qassem Soleimani and Iran’s Unique Regional Strategy,” CTC Sentinel 11:10 (2018).

[6] Vivian Yee and Hwaida Saad, “For Lebanon’s Shiites, a Dilemma: Stay Loyal to Hezbollah or Keep Protesting?” New York Times, February 4, 2020; Ben Hubbard and Hwaida Saad, “Lebanon Elections Boost Hezbollah’s Clout,” New York Times, May 7, 2018; “Hezbollah head says gov’t fall could push Lebanon into ‘chaos,’” Al Jazeera, October 25, 2019.

[7] Nader Uskowi, Temperature Rising: Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and Wars in the Middle East (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), p. 30; Matt Henman, “Iranian non-state proxy threat,” Janes Terrorism and Insurgency Centre, February 20, 2020.

[8] Uskowi, p. 30; Anna Ahronheim, “Hamas’s new leader radically shifts military strategy,” Jerusalem Post, September 27, 2017.

[9] For more information on the history of Iranian strategy in the Palestinian territories, see Uskowi.

[10] Joseph Felter and Brian Fishman, Iranian Strategy in Iraq: Politics and ‘Other Means’ (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2008); Jahanbani.

[11] Nancy Ezzeddine, Matthias Sulz, and Erwin van Veen, “The Hashd is dead, long live the Hashd!” Clingendael Institute, July 2019; Renad Mansour and Faleh A. Jabar, “The Popular Mobilization Forces and Iraq’s Future,” Carnegie Endowment, April 2017; Michael Knights, “Iran’s Expanding Militia Army in Iraq: The New Special Groups,” CTC Sentinel 12:7 (2019).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Karim Sajadpour, “Iran’s Unwavering Support to Assad’s Syria,” CTC Sentinel 6:8 (2013); “Chapter Three: Syria,” in “Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019.

[15] Smyth, “The Shiite Jihad in Syria and Its Regional Effects;” Parker and Noack; Soufan.

[16] “Chapter One: Tehran’s Strategic Intent,” in “Iran’s Networks of Influence in the Middle East,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019; Afshon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 205-213; Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi and Raffaello Pantucci eds., “Understanding Iran’s Role in the Syrian Conflict,” Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, August 2016.

[17] Tabatabai.

[18] Ostovar, pp. 216-218.

[19] For more information about Asa’ib ahl al-Haq, see Bryce Loidolt, “Iranian Resources and Shi`a Militant Cohesion: Insights from the Khazali Papers,” CTC Sentinel 12:1 (2019).

[20] For more information about Harakat al-Nujaba, see Knights, “Iran’s Expanding Militia Army in Iraq.”

[21] Philip Smyth, “Lebanese Hezbollah’s Islamic Resistance in Syria,” Washington Institute, April 26, 2018; Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Al-Ghalibun: Inside Story of a Syrian Hezbollah Group,” Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi’s blog, April 16, 2017.

[22] “Shia militias, the Syrian state, and the battle for Aleppo,” Janes Terrorism & Insurgency Monitor, November 24, 2016; Tabrizi and Pantucci.

[23] For more information about Quwat al-Ridha, see Philip Smyth, “How Iran is Building Its Syrian Hezbollah,” Washington Institute, March 8, 2016.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Tabatabai.

[26] Babak Dehghanpisheh, “Iran recruits Pakistan Shi’ites for combat in Syria,” Reuters, December 10, 2015; Raed al-Hamid, “Iranian Revolutionary Guard forms a corps called ‘Baqi’ to spread chaos in Gulf States,” Al Quds, June 27, 2016; Philip Smyth, “Iran’s Iraqi Shiite Proxies Increase Their Deployment to Syria,” Washington Institute, October 2, 2015. There is some discussion that Kata’ib Aimmah al-Baqiyah has tangential ties to Iran. For more information, see Jessa Rose Dury-Agri, Omer Kassim, and Patrick Martin, “Iraqi Security Forces and Popular Mobilization Forces: Orders of Battle,” Institute for the Study of War, December 2017.

[27] Oula A. Alrifai, “What Is Iran Up To in Deir al-Zour?” Washington Institute, October 10, 2019.

[28] “Palestinian Islamic Jihad,” Counter-Extremism Project; Michael Knights and Matthew Levitt, “The Evolution of Shi`a Insurgency in Bahrain,” CTC Sentinel 11:1 (2018); “Chapter 5: Foreign Terrorist Organizations,” Country Reports on Terrorism, U.S. Department of State, 2019.

[29] “Chapter One: Tehran’s Strategic Intent;” Nicholas Hargreaves-Heald, “Proving Ground: Iran’s Operational Strategy in Syria,” Small Wars Journal, May 27, 2018.

[30] Ostovar, pp. 220-229.

[33] “Shia militias, the Syrian state, and the battle for Aleppo,” Janes Terrorism & Insurgency Monitor, November 24, 2016.

[35] For a few counts of IRGC forces in Syria in this year, see “Shia militias, the Syrian state, and the battle for Aleppo,” Janes Terrorism & Insurgency Monitor, November 24, 2016; Marie Donovan, Nicholas Carl, and Frederick W. Kagan, “Iran’s Reserve of Last Resort,” American Enterprise Institute, January 2020; Tabrizi and Pantucci.

[38] Seth Jones, “War by Proxy: Iran’s Growing Footprint in the Middle East,” CSIS, March 11, 2019; Ostovar, pp. 222-229.

[39] Frederick W. Kagan and Paul Bucala, “Iran’s evolving way of war: How the IRGC fights in Syria,” American Enterprise Institute, March 2016; Donovan, Carl, and Kagan; Kristin Dailey, “Iran Has More Volunteers for the Syrian War Than It Knows What to Do With,” Foreign Policy, May 12, 2016; Ostovar, pp. 210-213.

[40] Donovan, Carl, and Kagan, p. 4.

[41] Jahanbani.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Boukje Kistemaker and Mitch Prothero, “Covid-19: Infection impacts Hizbullah’s domestic reputation and regional operations,” Janes Terrorism & Insurgency Monitor, April 28, 2020.

[45] Matthew Levitt, “‘Fighters Without Borders’ – Forecasting New Trends in Iran Threat Network Foreign Operations Tradecraft,” CTC Sentinel 13:2 (2020); Suadad al-Salhy, “Exclusive: Iran tasked Nasrallah with uniting Iraqi proxies after Soleimani’s death,” Middle East Eye, January 14, 2020.

[48] Ali Alfoneh, “Esmail Qaani: the next Revolutionary Guards Quds Force commander?” American Enterprise Institute, January 11, 2012; Ali Alfoneh, “Who Is Esmail Qaani, the New Chief Commander of Iran’s Qods Force?” Washington Institute, January 7, 2020; Tabatabai; Laura Kelly, “Soleimani’s enigmatic successor vows revenge on US,” Hill, February 2, 2020; “Report: Commander Qaani – Commander Operating Under The Shadow/Rushing To Catch Up To Haj Qassem,” Tasnim News Agency, January 4, 2020.

[49] “Report: Learn About the Past Experiences of the New Quds Force Commander,” Tasnim News Agency, January 20, 2020; Maysam Behravesh, “Mohammad Hejazi: The New Strategic Mastermind of Iran’s Quds Force,” Inside Arabia, February 10, 2020; “Brigadier General Mohammad Hejazi,” Iran Watch, October 31, 2008.

[50] Sajjan M. Gohel, “Iran’s Ambiguous Role in Afghanistan,” CTC Sentinel 3:3 (2010); Alireza Nader, Ali G. Scotten, Ahmad Idrees Rahmani, Robert Stewart, and Leila Mahnad, “Iran’s Influence in Afghanistan,” RAND, 2014, pp. 16-17; Brian Glyn Williams, “Afghanistan,” in Assaf Moghadam ed. Militancy and Political Violence in Shiism (New York: Routledge, 2012); Mahtab Divsalar, “Fatemiyoun’s Future Home: Syria, Iran or Afghanistan?” Radio Zamaneh, April 20, 2019; “Blood-Stained Hands: Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan’s Legacy of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, July 6, 2005.

[51] Brian Glyn Williams, “Afghanistan,” in Assaf Moghadam ed. Militancy and Political Violence in Shiism (New York: Routledge, 2012).

[53] Nader, Scotten, Rahmani, Stewart, and Mahnad, pp. 6-8; Maija Liuhto, “Analysis: Iran’s great game antagonizes natural Afghan allies,” Middle East Eye, May 3, 2016.

[54] For more information on the nature of Iran’s relationships with the Taliban, see Scott Worden, “Iran and Afghanistan’s Long, Complicated History,” United States Institute of Peace, June 14, 2018; Nader, Scotten, Rahmani, Stewart, and Mahnad; “Chapter 3: State Sponsors of Terrorism,” Country Reports on Terrorism, U.S. Department of State, 2012. For more information on the nature of Iran’s relationship with al-Qa`ida, see Assaf Moghadam, “Marriage of Convenience: The Evolution of Iran and al-Qa`ida’s Tactical Cooperation,” CTC Sentinel 10:4 (2017) and Nelly Lahoud, “Al-Qa’ida’s Contested Relationship with Iran: A View from Abbottabad,” New America, September 7, 2018.

[55] Ahmad Majidyar, “Iran Recruits and Trains Large Numbers of Afghan and Pakistani Shiites,” Middle East Institute, January 18, 2017; “Iran: Afghan Children Recruited to Fight in Syria,” Human Rights Watch, October 1, 2017; Mohsen Hamidi, “The Two Faces of the Fatemiyun (I): Revisiting the male fighters,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, July 8, 2019.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Louise Loveluck, “Iran promises to back Assad ‘until the end of the road,’” Telegraph, June 2, 2015; “Iran’s Zainabiyoun Brigade steps up recruiting in Pakistan,” Pakistan Forward, October 5, 2018.

[59] Loveluck; “Iran’s Zainabiyoun Brigade steps up recruiting in Pakistan.”

[60] Majidyar.

[61] Ishaan Tharoor, “Shiites in India want to join the fight against the Islamic State in Iraq,” Washington Post, August 4, 2014; Rakhi Chakrabarty, “Govt fears Shia-Sunni tension, issues alert,” Times of India, June 21, 2014; Smyth, “The Shiite Jihad in Syria and Its Regional Effects,” p. 44; Zachary Keck, “Can India Avoid Iraq’s Sectarian Conflict?” Diplomat, June 26, 2014.

[62] Keck.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ostovar, pp. 201-203; IANS, “Trump says Soleimani responsible for terrorist plots in Delhi,” Economic Times, January 4, 2020.

[66] Ostovar, pp. 201-202; Harmeet Shah Singh, “India names Iranian suspects in Israeli car bombing,” CNN, March 15, 2012; “Attack on Israeli diplomat’s wife: Case pending in court,” Outlook, January 4, 2020.

[67] Solomon.

[68] “Sepah: Infographic,” IranWire; “The IRGC Quds Force,” IranWire, April 9, 2019; “Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC),” Counter Extremism Project, January 3, 2020.

[69] Mona Alami, “Hezbollah allegedly training Nigerian Shiites to expand influence in West Africa,” Middle East Institute, July 5, 2018; Maysam Behravesh, “Iran’s Unconventional Alliance Network in the Middle East and Beyond,” Middle East Institute, April 7, 2020.

[70] Alami; Behravesh, “Iran’s Unconventional Alliance Network in the Middle East and Beyond,” pp. 14-15.

[71] Alami; Soli Shahvar, “Iran’s global reach: The Islamic Republic of Iran’s policy, involvement, and activity in Africa,” Digest of Middle East Studies, March 26, 2020.

[72] Jacob Zenn, “The Islamic Movement and Iranian Intelligence Activities in Nigeria,” CTC Sentinel 6:10 (2013); Eric Halliday, “Iran and Hezbollah’s Presence Around the World,” Lawfare, January 8, 2020.

[75] Emanuele Ottolenghi, “State Sponsors of Terrorism: An Examination of Iran’s Global Terrorism Network,” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, April 17, 2018; David Asher, “Attacking Hezbollah’s Financial Network: Policy Options,” Testimony, House Foreign Affairs Committee, June 8, 2017; Josh Meyer, “The secret backstory of how Obama let Hezbollah off the hook,” Politico, December 2017; Daniel Byman, “Hezbollah, Drugs, and the Obama Administration: A Closer Look at a Damning Politico Piece,” Lawfare, January 30, 2018.

[76] For some background on the Polisario Front, review Edith M. Lederer, “Morocco and Polisario at odds over disputed Western Sahara,” Associated Press, October 30, 2019, and Nicholas Niarchos, “Is One of Africa’s Oldest Conflicts Finally Nearing Its End?” New Yorker, December 29, 2018.

[77] “Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC),” Counter Extremism Project, January 3, 2020.

[78] Levitt, “Fighters Without Borders;” Jack Losh, “Revealed: How Iran tried to set up terror cells in Central Africa,” Telegraph, January 11, 2020.

[79] Jacob Zenn, “The Islamic Movement and Iranian Intelligence Activities in Nigeria,” CTC Sentinel 6:10 (2013); Matthew Levitt, Hezbollah: Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2013), pp. 246-284.

[81] Ali Alfoneh, “Afghans fear IRGC may deploy Fatemiyoun fighters to Afghanistan,” Middle East Institute, March 5, 2018; Levitt, “‘Fighters Without Borders;’” Colin P. Clarke and Ariane Tabatabai, “What Will Iran Do As the US Negotiates a Withdrawal from Afghanistan?” Defense One, April 6, 2020; Giorgio Cafiero and Maysam Behravesh, “Iran’s Fatemiyoun Forces: A Challenge to the US Mission in Afghanistan?” Inside Arabia, October 7, 2019; Uskowi, p. 27. For an in-depth study of the Islamic State Khorasan affiliate, see Amira Jadoon, Allied and Lethal: Islamic State Khorasan’s Network and Organizational Capacity in Afghanistan and Pakistan (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2018).

[83] Behravesh, “Iran’s Unconventional Alliance Network in the Middle East and Beyond.”

[84] “Hezbollah linked to Burgas bus bombing in Bulgaria,” BBC, February 5, 2013; Barak Ravid, “Hezbollah Members Arrested in Thailand Admit to Planning Attack on Israeli Tourists,” Haaretz, April 18, 2014; Ostovar, pp. 201-203; Matt Henman, “Iranian non-state proxy threat,” Janes Terrorism and Insurgency Centre, February 20, 2020.

[85] Ryan C. Berg and Colin P. Clarke, “Iran May Be Eyeing the United States’ Soft Underbelly,” Foreign Policy, March 6, 2020; Joseph M. Humire, “After Nisman: How the Death of a Prosecutor Revealed Iran’s Growing Influence in the Americas,” Center for a Secure Free Society, June 21, 2016; Behravesh, “Iran’s Unconventional Alliance Network in the Middle East and Beyond;” Asher; Matthew Levitt, “Iranian and Hezbollah Operations in South America: Then and Now,” PRISM 5:4 (2016).

[86] Humire; Berg and Clarke; Halliday; Levitt, “Iranian and Hezbollah Operations in South America.”

[87] Katzman.

[88] Ibid., pp. 40-41; Sen; Edward Lemon and Omid Rahimi, “A Thaw Between Tajikistan and Iran, But Challenges Remain,” Eurasia Daily Monitor 16:98 (2019).

Skip to content

Skip to content