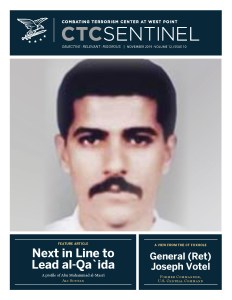

General Joseph L. Votel is a retired U.S. Army Four-Star officer and most recently the Commander of the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM)—responsible for U.S. and coalition military operations in the Middle East, Levant, and Central and South Asia. During his 39 years in the military, Votel commanded special operations and conventional military forces at every level. His career included combat in Panama, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Notably, he led a 79-member coalition that successfully liberated Iraq and Syria from the Islamic State caliphate. He preceded his assignment at CENTCOM with service as the Commander of U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).

Votel is the Class of 1987 Senior Fellow at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. He is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C., and the Belfer Center at the John F. Kennedy School of Government in Cambridge, MA and a member of the Council of Foreign Relations. Votel is a member of the Board of Directors for Service to School, a non-profit organization that helps military veterans transition and win admission to the Nation’s best graduate and undergraduate schools. In January 2020, Votel will become the President and CEO of Business Executives for National Security (BENS). He is a 1980 graduate of the United States Military Academy and earned master’s degrees from the U.S. Army Command and Staff College and the Army War College.

CTC: We wanted to start off with Syria and Iraq and to ask you to reflect on the lessons learned that you have from a military perspective on the territorial defeat of the Islamic State. What were the advantages and drawbacks of a strategy that relied heavily on Iraqi forces and SDF forces on the ground?

Votel: I think one of the things we did really well, in both Iraq and Syria, was applying the ‘by, with, and through’ approach.a I think we were able to strike the balance between the enabling activities that we needed to do for them—whether it was intelligence support, whether it was a certain amount of equipping, whether it was training, whether it was advising—I think we were able to do that without overdoing it. There’d have perhaps been great interest in the past in trying to get in and muck around with the Kurdish organizations or even the Iraqi forces and try to change them. We didn’t get too far into that. We took them as they were. And we tried to leverage them and enable them from that point. And I think that helped us move quicker frankly. But there’s some inherent challenges in that. They weren’t as efficient as they needed to be. On the Iraqi side, you had these different pillars of security, you had Ministry of Defense, you had Ministry of Interior, you had the federal police, you had Popular Mobilization Forces. We didn’t try to do something more with that. We worked with what he had. So I think that was a first key to success in this. The downside is there’s some inefficiencies that come along with that.

The second piece is we tried to focus on building really strong and trustful relationships with the key leaders. One example in Iraq was Abdul Amir [Yarallah], the Army three-star [general] who became their joint force commander. We focused on making sure that he was successful, and we had really strong relationships with him at all levels—including my level and then all the way down well into the organization. Same thing across the border with [General] Mazloum [Kobani Abdi], the Syrian Democratic Force leader. I made sure we had really good relationships, trusting relationships with him. And we were very clear with both of those partners about what we would do and what we would not do. And particularly with the Kurdish part of the SDF, I made sure he understood what our redlines were, things that we weren’t going to do. We were never going to go to Afrin. We were never going to do anything that would connect the cantons. If we ever saw something that looked like YPG or SDF attacks against the Turks, this would immediately be a deal breaker for us. We made these kinds of things really, really clear to him through our normal, routine interaction. And I think that developed a fairly trustful relationship in terms of them knowing what they were getting with us. Mazloum I know talked to a variety of other people; he talked to everybody. But he kept coming back to us, despite every opportunity we gave him by policy decision or things we said in the news or anything else, to walk away. He continued to come back to us because I think he viewed us as the preferred partner.

The last thing I would just say with regard to this was that in the orchestration of the campaign, we recognized there was a real urgency in the 2015-2016 timeframe to “get going, get to Mosul, come on, let’s get on with this.” We recognized there was a Kasserine momentb in the early days when the Iraqis faltered and ran away, and they had to be built back up. And so we had to take a more incremental approach to this and build confidence and build capacity and kind of set the scene for the campaign that followed. And we had to do better integration of our campaign plan with the humanitarian side and the government side. And I think we became proficient with that.

Same thing in Syria. We had a very incremental, clear way in which we were going to try to get down the Middle Euphrates Valley, and I think that worked for us. It was predictable. They understood where we were going. We knew where we were going. We were able to communicate it fairly effectively.

CTC: You were able to build these partnerships, and they proved, at the end of the day, effective in removing the Islamic State from territory both in Syria and Iraq. However, if you look at places like Raqqa, given the coalition’s need to rely on air power and work through non-U.S. forces on the ground, there was clearly a significant civilian toll, especially because the Islamic State was present in population centers and using human shields.1 Now that lessons are being drawn from this conflict, what needs to be the debate about whether more or fewer U.S. troops should have been used on the ground?

Votel: I think part of the challenge in places like this was that we didn’t have a lot of people on the ground who could go in and make evaluations afterward and confirm facts and do the investigation on things like that. I take that point, but it was where we were policy-wise. So I think in the future, a lesson learned out of this is that we have to plan for that aspect of it. It should not have been a surprise to anybody that there was going to be a lot of damage in the urban areas and that there were going to be civilian casualties. This was the nature of the fight. To accomplish the mission assigned, this is what was going to have to happen. And so, we certainly have to communicate that, but we also have to highlight the risk associated with that and that there may be some things we can do better.

It was very instructive to me in the closing months of the fight in Syria, especially as we got deeper into the Middle Euphrates Valley, which was very clearly Arab territory. We were using Kurdish forces along with our Arab militias, and we actually saw local tribal elders interacting in the campaign. At first, we thought it was really frustrating, but then we began to understand it provided a mechanism for us to try to control the violence and try to minimize the opportunities for civilian casualties. So several times in Raqqa and that last fight in the Middle Euphrates Valley, when for months we said, “we’re at 98 percent,” this was the reason why. It was because we kept starting and stopping because of the interaction of the tribal elders, the Arab tribal elders, trying to get people out, and trying to actually negotiate with ISIS. The tribal elders said to us, “We’re going to do it. We know you Americans don’t want to do it, we’re going to negotiate with them because we want them out of there, we want something left of our villages, we don’t want to kill a bunch of people on this thing,” and we supported that because that was what our partners were doing.

There’s a certain amount of flak that comes along when you are told “our partners are talking to ISIS right now.” I was like, “What? What are you doing?” Well, this is what had to be done. So you have to accept it. This is part of the ‘by, with, and through’ operational approach. When you rely on partners to do things, they’re going to do it in a partner way. We’re not going to like everything they do. It won’t be exactly the way we’d do it, but that was the trade-off. And frankly, even as horrendous as that fight was, I think we probably saved lives allowing them to operate that way.

CTC: Many believe that far too little is being done by the international community when it comes to fostering reconciliation in Syria and Iraq. As you think it through, what are the key steps that need to be taken to better foster that political reconciliation in a place that’s so difficult?

Votel: I think the key steps are there has to be a recognition that there’s going to have to be some compromise and there has to be an understanding of the facts on the ground. We can say that we don’t want to deal with the Assad regime because of the horrendous things they’ve perpetrated on their own people, but the fact is the Assad regime is in place here. To move forward we have to, I think, figure out some ways to accommodate the facts on the ground that might be very bitter pills to swallow. The same thing applies to Afghanistan. We’re going to have to talk to the Taliban. If we want to achieve the President’s objective in Afghanistan of reconciliation and using that as a platform to reduce our own presence and focus on our enduring interests there, there’s going to have to be some compromise here. Not everybody’s going to be happy with this. And so when we come in with very hard policy lines on these kinds of things, it’s going to take time, or we’re going to miss opportunities. And it’s going to make it harder for us to achieve what we need to down the line. We were basically in northeastern Syria to hold the ground, keep it stable while we worked through whatever comes next politically. This was slow in developing. With the President’s recent decision to pull back from the border, we are essentially trying to do the same thing but with less terrain, forces, and importantly less strategic influence and a more complex partnership relationship.

CTC: What do you think are the main lessons learned about what makes a good partner and how to transform partnerships that exist initially in principle into ones that result in real tangible effects on the ground?

Votel: Let me just start with the coalition. It was really important to have an effective way of communicating and interacting with our coalition partners so that they really felt integrated into the things that we were doing. And so, one of the things we put in place—my predecessor did and then we continued to refine it—was to make sure that we had forums and activities planned on a regular basis that brought the international military leaders together to make sure everybody was aligned with the campaign plan. That became very, very important. We essentially brought together what I refer to as the “framework nations” on a fairly regular basis, about every quarter. And we’d bring them to Tampa [location of U.S. Central Command Headquarters], or we’d go somewhere else. And these are the 12, 13 nations that were providing the majority of the military capability on the ground and in the air, and it was most important to align them. So we had to have a mechanism to talk among ourselves. So my first point is how important the communication aspect was to our effectiveness.

And then I think what allowed us to develop an effective relationship with the Iraqis and with the Syrian Democratic Forces was really this idea of trust-building with them at multiple levels. Again, making sure that we were talking clearly with them so that it was very clear to them the things we would do, and would not do. That was very, very important in this. This meant being first with the news—good and bad. For example, it was critical for me on December 19th last year after the President made his announcement [signaling that U.S. troops would withdraw from Syria]2 that the first person after talking to the Chairman [of the Joints Chief of Staff] that I went to was General Mazloum. So he heard this from me. And while I believe they were disappointed, I think the fact that we were able to very quickly explain to him what we knew, what we didn’t know, and then where we were going to go with this helped us move forward in a better way than might have been the case if we hadn’t had a very robust, trustful relationship. So all the work to build that up paid off on that afternoon when we really had a crisis and we were really putting the partnership to a test.

This strong relationship was also helpful when in December 2018 Turkey threatened an incursion into Syria.3 We made it very clear to the Kurds that this was a NATO ally and we aren’t going to take military action against Turkey, and that allowed us to help them work through this and get back into the fight against ISIS. We stopped the campaign two or three times because of what was happening on the Turkish border. Yet we were able to get the SDF back in the fight. It took time, but it was about having a good, solid relationship and convincing them “it’s better for you to stay with us and continue to finish the campaign, and that will put you in a position where there will be an advantage for you long term.”

CTC: This issue of Turkey and northern Syria is a very thorny issue for U.S. policymakers for all the reasons you’ve described. What needs to guide U.S. policymakers moving forward managing this problem set?

Votel: I think, first of all, the interests of all the parties need to be well understood, and our position ought to be that we are going to try to devise a solution that does the very best job of addressing everybody’s interests in this. Not everybody is going to be 100-percent satisfied with this. But if we can’t achieve everyone’s interests, if we can achieve some compromises in this, and this is kind of in the approach: it’s this idea of a security mechanism—not necessarily a safe zone, I think that’s an inaccurate term for what we’re trying to do here; unfortunately, that’s out there and people use it; it’s not really the approach when you look at what safe zones do—but there is a way to put in place certain communication, security, surveillance, other things that allow us to basically address the interests of all the parties.

Turkey’s got interests. They don’t want to be attacked. They want to be secure along the border. Got it. That’s very valid. The peoples of northeast Syria want to be safe, want to be safe from attack, they want to have an opportunity to recover and be in their communities and not move back into camps. That’s a legitimate concern. We have an interest in preventing ISIS from resurging and keeping the area stable. I think all of those can be accommodated, but it isn’t going to be by just collapsing to somebody’s, to one party’s desire for a 30-kilometer-deep zone in this area. That’s only going to address one of the parties’ interests. Our view needs to be, our approach, our strategic approach is balancing these interests. And that’s what we’re doing here. So it’s unacceptable to continue to talk about this because you know that that doesn’t fit into the overall framework here.

As we now know, our decision in October to pull back from the border made a Turkish incursion inevitable. What I learned out [of] this was the importance of clear and direct communication. It is important to not only be direct but also to make clear what is acceptable and not acceptable. In my view, we should have used our moral authority as the leader of the coalition to compel Turkey to stay engaged in the security mechanism process that was underway. If we did not think this was going to work, we owed it to our partners on the ground, the SDF, to make different arrangements.

CTC: In the September 2019 issue of CTC Sentinel, Acting Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire warned the Islamic State “had all the recipes” for a resurgence and noted that “tens of thousands” of fighters “remain unaccounted for in Syria and Iraq.”4 Given all that we’ve seen and know about the evolution of the Islamic State, how can this resurgence be prevented? Or is it an inevitability?

Votel: I think it’s an inevitability that there is always going to be an element of resurgence out there. I think what we were trying to do is work with our partners—whether the Syrian Democratic Forces or the Iraqi forces—to make sure that they could keep that threat controlled and bounded within a framework that is manageable and sustainable from their standpoint. This became more difficult with our decision to pull back in Syria, but as we have seen, we retain access and opportunities to prosecute operations against ISIS—the raid to get Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is a good example.

I think it’s unreasonable to think we can completely eliminate all of this in the near term. Maybe over time you can begin to address that, but I think we have to recognize there is going to be a certain amount of instability, there is going to be a certain amount of ISIS that is left behind. And we have to plan for it, resource that, and make sure that our partners are ready to handle it. That should be the object of our security activities right now from a U.S. standpoint, a coalition standpoint.

I don’t know what form ISIS will take next. They’ve gone to ground. You’ve got still very radicalized populations in terms of women and children in these camps. We don’t have a good disposition for them. We still don’t have a good disposition for the 2,500-plus foreign fighters that are being controlled by the SDF. So I don’t know what direction this takes. Maybe ISIS’ next iteration is them being more patient and allowing for the situation to return to the way that it was, to become more polarized so they can take advantage of that opportunity again. Maybe they’ve learned their lesson: “We can’t govern. We can’t control terrain. But we can certainly make life very, very difficult, and to try to achieve our objectives through a different tactical, operational approach.”

CTC: It took years to track down Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. How big a priority was finding him, and what difficulties did the United States face in trying to do so over the years? What impact do you assess his death will have on the Islamic State’s ability to sustain its operations and inspire terrorism around the world?

Votel: Tracking down al-Baghdadi was an important milestone. Leadership in these organizations matters, and while he had been under great pressure as a result of the campaign, his death was an important psychological blow for his fighters and it sent a strong message to his victims. We have learned over time that these organizations are very resilient, and they plan for leadership losses. So I do expect we will see emergent leadership try to take over and continue the ISIS mission. This is why we take a long-term view as we keep pressure on these groups.

CTC: One way the Islamic State has sought to sustain its global reach is by continuing to spread its ideology through its media and propaganda apparatus. How would you assess the United States’ performance in the war of ideas? And where can the United States improve preparedness to better counter the messaging of its adversaries in the future?

Votel: I think we had difficulty in the beginning getting our arms around publicly available information and trying to understand that and then interact in that space to have an impact on ISIS. I think we became more effective with it over time. We drove them off Twitter. We drove them off certain forums like that. We made it much more difficult for them when we were able to actually begin effectively integrating cyber activities into our normal military operations. We also became much more effective when we shut down sources for people to get information out; we were kinetically striking them, putting pressure on those areas. That became a much more effective approach overtime.

So I think we’ve improved our abilities in this regard, but the challenge is that many of the underlying issues that gave rise to this organization still remain—disenfranchised populations, corrupt governance, the divide between haves and have-nots, the economic disparity that is playing out. When you look at why fighters came to ISIS, it was because they gave them an identity, they gave them a job that they were paid for, and it gave them a family. These are basic things that everybody aspires to, and ISIS fulfilled that. I think somehow our efforts have got to nullify that effect as we go forward so they can’t use that, and I’m not sure we’re effectively doing that.

CTC: Shifting the discussion to Afghanistan, the United States has been there for 18 years now. The talks between the United States and the Taliban broke down in September. What are some of the lessons learned about what can be achieved in Afghanistan by military means? The Taliban seem to believe that time is on their side. Is it? Can the United States prove that wrong?

Votel: I don’t know that we can prove it wrong. I mean, I think to some extent, that’s true. Obviously, we’ve had a variety of different strategic approaches here that we’ve attempted to apply. And we’ve tried to do it, many times, within a time constraint. And I think that has limited us. My personal belief is that the latest strategy that was announced, whether you agree with this approach or not, was very clear and it gave us something to rally around.

The rationale behind the most recent South Asia strategy was, “Ok, the end state here is trying to bring the Taliban and the government of Afghanistan together to some level of reconciliation. And if we can do that, then that gives us a chance to withdraw some of our forces, making sure that we can protect our enduring interests, making sure it doesn’t become a terrorist safe haven or platform, and to do all that in a much more sustainable, long-term way.” Ok, so some people would agree with that. Some people wouldn’t agree with that. But nonetheless, that’s what the President decided our strategy was going to be, and that’s what we had to get behind.

So, to me, I think that was an approach that we could make some progress on. And my belief was Ambassador Khalilzad was doing his best to do that. We tried to align our military activities to support him as much as we could—whether it was my interaction with the Pakistanis or whether it was with specific things that General Miller [the Commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan] was being asked to do on the ground to create leverage points that were useful to Ambassador Khalilzad. Again, like most of the things we’ve been talking about, this is not going to be perfect. We’re not going to satisfy the government of Afghanistan to begin with. But there needed to be, in my view, more interaction with President Ghani to reassure him that, “Hey, here’s what we’ve gotta do. We’ve gotta create some kind of platform over here. We’ve gotta create some kind of enclave of trust, of agreement with the Taliban so we can bring them over to you here.” We were ineffective in doing that. That’s not something the military can do, frankly. That requires our diplomatic and political leadership to help us with that.

My view here is that the President’s strategy was very, very clear. We identified a strong envoy in the form of Khalilzad. I think we tried our very best to get the military aligned with what he was doing. I sometimes wonder if the rest of the government got aligned behind that as well. And I do think if we could have done that and held the line, we could have perhaps been more successful in getting him to a point where we could have an opportunity for reconciliation.

CTC: During that dialogue, in March 2019, a Taliban spokesman said that “a core issue for the American side is that the soil of Afghanistan should not be used against the Americans and against its allies.”5 The following month, U.N. Monitoring Team Coordinator Edmund Fitton-Brown noted that there were at least “grounds for hope” because “the Taliban has shown an iron self-discipline in recent years in not allowing a threat to be projected outside the borders of Afghanistan by their own members or by groups who are operating in areas they control.”6 The problem, of course, is al-Qa`ida has re-pledged loyalty to the Taliban.7 And you’ve got Sirajuddin Haqqani, who’s a deputy leader of the Taliban but has close ties to al-Qa`ida.8 In working toward this political settlement, if that’s where the end destination needs to be, how difficult is it going to be to ensure that Afghanistan does not again become the launching pad for international terrorism?

Votel: I think that that’s an enduring interest for us, and so I think as part of the discussions, we have to address that. And while I get it that we haven’t in recent years had more of that kind of international attack plotting come from this area, I certainly would not suggest that we outsource our national security interests to the Taliban or the government of Afghanistan after some of the experiences that we’ve had.

And so I think if we can get an agreement, that this is in our interest and that can be leveraged, then I think we can begin to look at what residual capability we need to leave on the ground or in the region to protect our interests. This could be U.S.-only strike forces, ISR, or partnering capabilities with Afghan Special Operations Forces using a ‘by, with, through’ approach. Perhaps this posture changes over time as you gain confidence or the threat is decreased or the situation changes. This residual capability can only operate with a reconciliation in place between the government and the Taliban. We have an enduring interest to ensure this country and this region cannot be used as a platform to attack our homeland, our citizens or those of our friends and allies.

CTC: Turning now to Iran, pro-Tehran so-called Special Groups have expanded their personnel in Iraq.9 The Houthis have claimed, though not always convincingly, they carried out drone strikes in UAE and Saudi Arabia.10 Hezbollah has stockpiled weapons and played a key role in buttressing the Assad regime in the Syrian war. What level of threat do you believe Iranian proxy groups pose to U.S. interests in the region?

Votel: The threat that they pose is they could perpetrate attacks against Americans or American interests in any of the areas where we happen to be co-located. I think that’s the big concern. I think as we looked at other things that were happening in the Gulf, it became clear to me we needed to look at the threat through the lens of everything that Iran can bring to bear against us. And the fact that they have these proxy surrogates/groups that are aligned to them is a serious challenge. These proxy groups can cause casualties. They can kill troops. But I don’t consider them to be an existential threat.

CTC: The September attacks at Abqaiq and Khurais oil fields with drones and cruise missiles were claimed by the Houthis. Western governments have pointed the finger more toward Iran, although the picture remains murky on where these strikes were launched from based on publicly available information.11 How dangerous an escalation do you see this attack?

Votel: I think it is pretty dangerous, and I think there’s two ways that I look at it. One is first through the maturation of the technologies. We’ve been watching this for a while, with both these drones and with missiles and other things that can actually penetrate defense systems and get in and hit these vulnerable targets. We’ve watched the Houthis with Iranian support kind of move from quad-copters to bigger, medium-sized UAVs to now larger sizes that can penetrate much further and put infrastructure at risk. And then, of course, there is the development of missile technology that we watched over a long period of time.

I don’t know how this attack was actually perpetrated, but Iran certainly has used their access and their partners and their know-how to provide them with better weaponry including surface-to-air and surface-to-surface missiles. And so I think about it from the concern of just a maturation of these systems and how quick they are learning on this drone side. When you look at our long learning curve here, theirs is much sharper. They’re taking advantage of what we have learned on this.

And then the second thing is, whether Iran were directly or indirectly involved in this, I think they’re doing it for the same purpose and that is they’re trying to figure out what our redlines are. They’re trying to push up against this so that we can get to a point where we are talking with them.

I think one of the challenges we have here, and this is an anathema to some people, is our inability to communicate with Iran about anything we’re doing in the region. This is a hinderance to us right now. We really don’t know what they’re thinking. We don’t know how they assess the things we’re doing, and vice versa, and really what we’re after. And so, we have to be clear in terms of what our strategy is. We say we don’t want to go to war, but sometimes our rhetoric is much different than that. We have to achieve some kind of alignment with that. And we have to figure out a way that we are talking to them and have a way of communicating with them. I am deeply influenced by our ability to talk with Russia in Syria. I believe this was a factor in our success. It kept us safe; it kept them safe. It gave a professional military-to-military mechanism for us to communicate with them. This was extraordinarily important. And it just reinforced the notion that you’ve got to find a way to communicate to people, and it helps reduce the opportunities for miscalculation. When you don’t have a way to talk to people and something is happening out there, people are going to react with what they have. And that’s usually going to be a weapon or something else. So it would be great if our maritime commander could talk to their maritime commander. You’re not trying to synchronize things. You’re not trying to be friends with them, but a professional military-to-military communication link would be very helpful.

CTC: Last year, CTC Sentinel published a major profile of the long-serving head of Iran’s Quds Force, Qassem Soleimani, the driving force behind much of the Iranian strategy.12 What’s your assessment of him as an adversary?

Votel: You have to respect all your enemies. When you stop respecting your enemies is the time that you become extraordinarily vulnerable. So we have to respect what their capabilities are, what they’re attempting to do, and their ability to execute it. He has demonstrated he’s a dangerous person, and he is able to orchestrate things. So we have to respect that, understand that, and plan for that type of stuff. His role is different than any other military commander that anybody in a Western nation would have because he has both this military capability but he also has this kind of quasi-diplomatic, political, policy, strategy kind of role that he plays, and the access that he has, I think, gives him the opportunity to have an outsized role and to connect these policy decisions to the action arms that can carry them out, so I think he’s an extraordinarily dangerous person. I think there’s very little chance that he will change. So, the sooner he can be removed from that aspect, the more our chances may get better for some kind of peace. Because it is this very revolutionary leadership that I think continues to perpetuate the conflict between our countries.

CTC: To bring this discussion back around to Iraq, the role of Iran there has been a major challenge, and has fluctuated over time, but seems to be at a significant inflection point. What should guide U.S. policy in Iraq moving forward?

Votel: I think the biggest opportunity is continuing to demonstrate our value to Iraq, in terms of being good partners to help them keep moving in the right direction. If we can maintain it, then I think it’s worth the investment to stay linked with them. I think they’re a lynchpin country. They sit at an important location geographically, and they’re at a pretty key nexus with us. So I think we have to continue to stay engaged with them and continue to be seen as value-added by them. It’s very instructive to me that, you know, the one entity that we did stay with after 2011 was their counterterrorism service (CTS). Just with two ODAs,c that’s it, two ODAs. Ultimately, the Iraqi security forces were essentially rebuilt around the CTS. They became the core of all this. They never lost their level of professionalism, their capabilities, their apoliticalness, and their focus on state security as the Iraqi Army drifted away because we broke our relationships off. So I think the opportunity for us is to continue to be seen as value-added. So that’s the greatest opportunity. I think the Iraqi Army can really be something the nation can rally around. I think it’s good to try to provide that for them. We should support them.

CTC: Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has drawn attention to a suicide bomb attack on May 31 in Kabul, which injured four American servicemen and which the U.S. government believes was instigated by Iran.13 What concerns, if any, do you have about what they are trying to do in Afghanistan? How does that impact what the United States is trying to do?

Votel: I think Iran has concerns for their own security with respect to Afghanistan. They certainly have along their eastern border, the western border of Afghanistan, so they have influence in that area and interest in making sure the western part of Afghanistan remains stable. You can’t deny that. I think it’s in everyone’s interest to have a stable Afghanistan here, so this is an opportunity for convergence if we can get to a point where we can begin to discuss those kinds of things.

Frankly, I never really thought of Iran as necessarily a security risk in Afghanistan. I viewed them much more as a political risk, influence risk against some of the things that we were doing. That being said, their ability to influence Afghan units or their perhaps support to Taliban or other organizations as they try to stabilize the situation, I think, are the things we should be concerned about. But in terms of them directly doing something, that was not really our concern. I think it was more the influence that they were able to achieve as they pursued their own interests.

CTC: There’s been a lot of discussion of late on a shift toward a focus on near-peer competition and potentially a resulting shift away from counterterrorism. What’s your perspective on balancing across what is probably a logical refocusing, to a certain extent, but also mitigating against the risk of complacency in the terrorism fight and ensuring that the United States is able to consolidate the gains made in the fight over the last couple decades against the terrorism threat?

Votel: First and foremost, I am on the record as supporting the National Defense Strategy and making sure that we maintain our competitive advantage against great powers out there, states that could have an existential impact on the United States. I don’t think that anyone can argue with that. I think that’s pretty clear, and I support that. That said, I think there are going to be other threats out there and there are going to be interests that we have, and so I was very supportive of the integrated campaign plan approach that the Department of Defense, the Joint Staff was pursuing with the combatant commands, that began to look at the threats we had and looked at the intersection between all the different areas where that played out. I recognize that in CENTCOM, we had certain responsibilities with Russian influence or maybe some Chinese activities in that particular region, and that’s the way we ought to look at it. So I think the first piece is continuing to follow through with the integrated planning effort that has been undertaken by the Joint Staff. It is a really important aspect.

Secondly, this ultimately gets down to resources. We have to figure out what the sustainable level of resources are that the CENTCOM commander in that region can count on to address the threats and the interests that exist in that particular area. And that will probably be less than he wants it to be, so then I think that moves us into a third area and that is this idea of what are we going to ask our partners to do and how are we going to help them do that. And so it’s given that we’re going to focus on other areas and given that resources are going to flow to these areas and we’re going to have less than we need to address our threats and interests in areas like CENTCOM. So then what are we going to do more with our partners to help offset that? So we have to look at our security cooperation plan. We have to look at our FMF and FMS [Foreign Military Financing and Foreign Military Sales] programs and make sure that they are geared to the objectives that we want to truly achieve in this area. And that’s going to be heavily focused on making them more resilient, more capable—not just having stuff but having stuff and actually being able to use it for their own collective defense. I think we have to have some hard discussions about that. And so, linking that whole system to the overall strategy is really important in those three areas: planning, resourcing to a sustainable level, and then making sure that we are developing our partners who help mitigate those situations where we have to take some risks.

CTC: Over the past couple decades, there’s been considerable and significant amount of change across how the United States conducts Special Operations and counterterrorism activity. In the various roles and various commands you’ve had, you’ve had an integral role in shaping a lot of those changes. When you look back over that time period, what stands out to you as the most interesting aspects of how U.S. Special Operations Forces and CT capabilities have evolved?

Votel: I think the most interesting and the most satisfying thing is the integration between Special Operations Forces and our conventional forces. I think we’ve reached an apex of this in Iraq and Syria, and I think it was very, very evident in our performance on the ground and just in the relationships that you saw there. Our ability to move people from the Special Operations community back out to the conventional forces and draw on that experience, and then bring them back to the Special Operations community, and much more integrated command and control arrangements that we’ve had in place that actually put the Special Operations formations under the command of conventional JTF commanders, I think, represents a level of trust and integration that we haven’t enjoyed before and that we’ve always strived to realize and known that we could achieve, but it took a lot to do it. I think that’s the thing I’m most satisfied with. And as we look towards things like great power competition, I think that experience is now rightfully driving this discussion of “ok, well, what is the role of Special Operations in great power competition?”

And so you see much more intellectual discussion about these and much more work on the ground and debate about what that is. And I think you see organizations like SOCOM and JSOC and others who have played this key role in the CT fight now looking at “what do we do to be relevant, to be value-added to this coming challenge?” I think that’s really healthy for the force.

CTC: So to build on that a bit, some have suggested that the heavy emphasis placed on the SOF role in the CT fight and perhaps the heavy cost paid by that community and the level of effort they had put into it potentially took away from the SOF community’s ability to address the near-peer threat. It sounds like you’re saying that their role in that fight set them up to learn lessons and to build upon that experience to actually make it a better force to fight in the near-peer world.

Votel: Through relationships, through experience, through systems that we put in place, we’re a much smarter force. Conventional force commanders are much—I’m not sure if comfortable is the right word, but it’s the right sentiment here—are much more confident in an ability to integrate Special Operations activities and formations into the broader campaign, perhaps much more than we were. And vice versa. The SOF community is much more comfortable with the sentiment and much more comfortable with doing that, and so I think that gives us a really good basis to begin to move forward. I do think, though, perhaps there ought to be more discussion on who really is involved in the CT fight. When I look at a place like Syria, we definitely had SOF organizations on the ground who were advising and who were working with our partners. But as I look back a little bit deeper from that pointy end of the stick there, we had logistics formations from the Army and the Air Force running air fields, we had Marine artillery that was in there, we had Army aviation that was in there supporting that, we had Army HIMARS [High Mobility Artillery Rocket System] that were in there providing precision fires, so there’s an awful lot of the CT fight that is being done by our conventional forces.

So I sometimes think we overemphasize that the CT fight is really about just SOF skills when, frankly, the SOF community has always been extraordinarily dependent upon conventional force enablers and capabilities and backstopping to be successful with this. Or put another way, this isn’t just about these snake eaters over here, this is about bringing everything to bear to get after the problem.

CTC: What are your thoughts on the national security dimensions of technology and innovation? One example has been the use of drones by a terrorist organization, but more broadly, what are your thoughts on how the United States competes in that space?ハ

Votel: I think this is an area to really focus on. I think we have to have, one, a strategy for where we’re going technology-wise. I think we have an advantage but we also have a disadvantage because the Chinese are very centralized in terms of how they’re approaching their technology development and cutting-edge capabilities. It all comes out of a centralized government approach. We have a much more bottom-up approach. I think there’s some really great advantages for that, but there’s also I think a much bigger integration challenge. Connecting those people that are in development with the people that are using it I think is really important for us. The learning curve is moving so quickly right now.

CTC: You’ve spoken to cadets here at West Point about what it takes to be a good leader. And the things you laid out were: trust your instincts, use your position for good, take care of yourself and your family, and be a happy leader. It was striking that what you laid out could really be applied to leadership in any organization, at work, in politics, even in your own home, in your own family. Why did you see those particular qualities as important?

Votel: I think because my observation about leadership over time is that the basics really matter. If you look at business literature, there’s tons and tons of books about different techniques and everything else. But in my view, it really does come down to pretty basic things about being a good person and drawing on your own experience to understand what’s right and what’s wrong and then modeling that for people. Just being a decent human being and taking care of yourself. The thing that I was always concerned about were tired leaders, people that just work themselves into a lather and as a result, their organizations as well. You could just see that permeate through an organization. So taking care of yourself and maintaining some of the balance in your life was really important.

It’s really heartbreaking to see a man or woman get to the end of their career and they’ve been very successful, but the price they paid was they lost their family. When I was at a battalion commander course at Ft. Leavenworth, we had a senior officer, a three-star [general], get up and talk about that. I was like “Oh my god.” It was emotional for him, the price that he had paid in trying to balance that.

People really have an option. They don’t have to come to the military. They can go do other things. But wouldn’t it be great if they came in, had this great experience, did a tour, then went back out to business or to be school teachers, and they’d always say, “yeah, I was in the Army, I had this great experience, I had these officers, these NCOs, they took really good care of me, and it was really a sense of team work,” and they became coaches and other things out in their communities and made them better. I agree with you. I don’t just use that for military audiences. I use it for virtually every audience that I have an opportunity to talk to. It’s about the basics.

CTC: You’re now a senior fellow at the Combating Terrorism Center. What is your perspective on the value of academic and scholarly research in the counterterrorism space? Also, what is the value of, where appropriate, declassifying captured enemy material and getting it to scholars in the open source domain?

Votel: I think you’re on to something right here. I always viewed visits to the CTC and other academic institutions that I went to, as a way to help me do my thinking. So, you know, whether it was engaging a guy like Graham Allison at the Belfer Center or Dick Shultz at Tufts or your predecessor in theハorganization here at CTC, these were always opportunities to come up and have a conversation with people and do your thinking without the burden of having to make a decision about something. And in the busy military, in the busy Department of Defense, our senior leaders are often a mile wide and an inch deep, and there needs to be a mechanism in your rhythm that allows you to do thinking. And that’s what the academic engagement, to me, does. Routine visits here annually, maybe even a little bit more, to here, places like Tufts, Belfer Center, other places we have out there, I think is really invaluable in helping you think through problems and look at things from a different perspective. Use it as a bit of a sounding board. So that was very valuable to me. And I think it is valuable to my colleagues.

To your other point about releasing information to the organizations, again, I see the value of that. This organization [the CTC] does remarkable work with a little bit of information. I’m always amazed when you come up and go, “hey, we’ve got these couple documents right here, but we were able to learn this out of it.” Your recent report on children in ISIS territory [based on a captured Islamic State spreadsheet] and the implications of your findings regarding how children transition from being dependents to being fighters at a certain age, that was fascinating to me. I would not have even thought about that. So, I think, again, this adds another dimension to the way we look at the data here. I think it’s extraordinarily important … absolutely essential.

CTC: Any final takeaways for our readers?

Votel: The only one I would add is that when it comes to national security, I think it’s really important to figure out how we balance policy and process. I’ve come to the observation that if you have policy without process, that’s foolish and dangerous, and if you have process without policy, that’s meaningless. There has to be a balance between this. And we really have to look at how we align people with the things we’re doing, all the way up and all the way down, left and right. And that has to happen through this policy and process framework. I think that sometimes works against us, and we’ve seen, I think, the extremes of that over the last several years, where we had a lot of process and at the end of that, the good thing is that everybody’s aligned. But the bad part of that is it takes a lot of time and we miss opportunities. At the other end of this, we take advantage of opportunities but we’ve got people rolling on their own and not everybody is completely aligned. So, what we have to do is figure out a way to balance that. I think that’s a really important aspect of keeping people aligned. CTC

Substantive Notes

[a] ‘By, with, and through’ is a key term and concept that was born out of the special operations community but whose use has been expanded to describe a broader approach to military operations that relies on partners to pursue U.S. interests. See Joseph L. Votel and Eero R. Keravuori, “The By-With-Through Operational Approach,” Joint Force Quarterly 89 (2nd Quarter 2018).

[b] “The battles in and around the Kasserine Pass [in Tunisia] between Feb. 14 and Feb. 22, 1943, were the first clashes between the Americans and the Germans. It was a disastrous debut. Of the 30,000 Americans engaged under II Corps, nearly one of four were casualties … The Americans were pushed back more than 50 miles, although they took back their original positions four days after the German blitz ran out of steam.” Robert Dvorchak, “Kasserine Pass a Baptism of Fire for U.S. Army in World War II,” Associated Press, February 6, 1993.

[c] In the U.S. Army, “Special Forces are organized into small, versatile teams, called Operational Detachment Alphas (ODA).” “Special Forces Team Members,” U.S. Army.

Citations

[1] “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic,” United Nations General Assembly Human Rights Council, February 1, 2018, pp. 9-11.

[2] Barbara Starr, Ryan Browne, and Nicole Gaouette, “Trump orders rapid withdrawal from Syria in apparent reversal,” CNN, December 19, 2018.

[5] “US-Taliban negotiations in Qatar enter fifth day,” Al Jazeera, March 3, 2019.

[7] “Al-Qaida Chief Pledges Support for New Afghan Taliban Leader,” Voice of America, June 11, 2016.

[10] Caleb Weiss, “Houthis claim major drone operation near the UAE,” FDD’s Long War Journal, August 17, 2019; Ben Hubbard, Palko Karasz, and Stanley Reed, “Two Major Saudi Oil Installations Hit by Drone Strike, and U.S. Blames Iran,” New York Times, September 15, 2019.

[11] Hubbard, Karasz, and Reed.

[12] Ali Soufan, “Qassem Soleimani and Iran’s Unique Regional Strategy,” CTC Sentinel 11:10 (2018).

[13] Siobhán O’Grady, “The Taliban claimed an attack on U.S. forces. Pompeo blamed Iran,” Washington Post, June 16, 2019. See also “Transcript: Russ Travers talks with Michael Morell on ‘Intelligence Matters,’” CBS News, July 3, 2019.

Skip to content

Skip to content