Mark E. Mitchell is a highly decorated U.S. Army combat veteran in the Special Operations community with extensive experience in the Middle East and South Asia and national-level defense and counterterrorism policy experience. Mitchell was among the first U.S. soldiers on the ground in Afghanistan after 9/11 and advised the Northern Alliance prior to the fall of the Taliban regime. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions in the November 2001 Battle of Qala-I Jangi in Mazar-e Sharif.

Mitchell is currently the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low-Intensity Conflict. In 2014, Mitchell served as a Director for Counterterrorism on the National Security Council where he was intimately involved in significant hostage cases and recovery efforts. He was instrumental in establishing the framework for the landmark Presidential Policy Review of Hostage Policy. As a colonel, he commanded 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) and simultaneously commanded a nationwide, Joint Special Operations Task Force in Iraq in 2010-2011.

CTC: You’ve been involved in the SOF [Special Operations Forces] enterprise for more than 20 years, from the tactical level during the initial invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 to commanding a Special Forces group to now serving as the PDASD in SO/LIC. Broadly speaking, during that time, the role of SOF units in the CT fight has changed in a number of different ways. What are some of the most important changes that you’ve seen in the employment of SOF forces during the CT fight over the last 15-20 years?

Mitchell: I think the most obvious ones are that first of all, the SOF enterprise has, over the span of 17 years, almost doubled in size. We were around 40,000 total civilian and military across all of USSOCOM in 2001, with an annual budget then of about $2 billion. Today, the SOF enterprise stands at well over 70,000 people and an annual budget somewhere north of $13 billion. So there’s been a remarkable growth not only in the size but also the resources devoted to the SOF enterprise. And importantly, I think that’s a reflection of the role that SOF plays not just in counterterrorism but in all aspects of irregular warfare and conventional warfare. We’ve seen the SOF community and our forces become, instead of a peripheral player, a core element of many of our national security strategy and policy initiatives.

The downside, though, is what we refer to as the “SOF easy button.” There’s a tendency amongst some policy makers and some leaders—both civilian and military—to look to Special Operations to solve hard problems. And while we’re very good at doing that, not every hard problem has a good SOF solution. Special Operations, while they are an important part of achieving our national security objectives, can very rarely be the sole solution. Every DoD effort, including Special Operations, needs to be integrated with our other instruments of national power. I think as we move forward, particularly as our focus shifts from CT to great-power competition, we’re going to have to be mindful of that to ensure that we’re taking on the right missions.

CTC: What is the role of your office in managing those transitions? Where does ASD SO/LIC fit into this?

Mitchell: ASD SO/LIC was created contemporaneously with U.S. Special Operations Command and was always envisioned to be like SOCOM, a dual-purpose organization. You have two main aspects for SO/LIC: the policymaking side and a Service Secretary-like resourcing and oversight function focused on SOF-specific funding—known as MFP-11—provided by Congress. But for a variety of reasons, particularly in the aftermath of 9/11, ASD SO/LIC became much more focused at a tactical level and on operations overseas, while the resourcing and oversight functions dwindled. Congress took note of that and decided that we needed to re-energize our role in the resourcing and oversight.

The 2017 National Defense Authorization Act included provisions intended to ensure that ASD SO/LIC had a stronger role in the resourcing and oversight functions. So that has caused a kind of fundamental transformation of a portion of the SO/LIC portfolio. We have received authorization to add additional personnel and are becoming more directly involved in issues related to the manning, training, equipping, and organizing functions of USSOCOM. SO/LIC also retained a broad policy portfolio that includes not only Special Operations and combating terrorism but also all aspects of irregular warfare, hence the low-intensity conflict, which is really a legacy from the ‘80s and the creation of SO/LIC. We also have humanitarian assistance, peacekeeping, disaster relief, global health engagement, counternarcotics, counter transnational organized crime, all forms of illicit trafficking, and counter-threat finance. We also have detainee policy. So we have a very broad portfolio of tasks, all of them relating one way or another to either Special Operations directly or irregular warfare.

CTC: With the recent shift in strategic focus back to great-power competition, how do we maintain an appropriate level of focus on the CT fight?

Mitchell: It’s a great question. The good news, or bad news depending on how you want to look at it, is that our adversaries have a vote. The fact that they will continue to seek ways to attack our interests and people overseas and even here at home will force us to reckon with a continuing threat of terrorism. Within SO/LIC, within SOCOM, and even here within the Pentagon, everybody from the Secretary on down recognizes that the CT fight is not going away and that we need to remain engaged. The challenge is to find those opportunities where both the threat is sufficiently manageable and we have partners and allies that are willing to step up to contain that threat. Secretary Mattis has also challenged us to find more cost effective approaches to this problem and increase our overall readiness. The fundamental answer is we’re going to have to remain very vigilant with our intelligence community and be prepared to reallocate SOF between great-power competition and CT as necessary to keep the threat at a manageable level.

CTC: Speaking more operationally then, have Special Operations Forces been appropriately applied in the CT fight? Or do you think more change is needed to balance the roles of SOF versus conventional forces versus other instruments of national power?

Mitchell: I think our role in CT has been very appropriate. We have two major roles: training and advising host nation forces in terms of developing their CT capabilities, and then being prepared when required to conduct our own unilateral operations to address the threat. I know there’s been a lot of criticism over the years that Special Operations teams “do too much direct action,” that they’re supposed to be simply training host nation forces. What I think a lot of the critics fail to realize is that part of that training is actually going out with them and advising, assisting, and accompanying them as they conduct those operations. This allows us to coach, teach, mentor, and monitor their operations. Our presence also reassures them and reinforces our partnership. It’s both necessary and appropriate.

One of the areas where I think we as the United States, as the Department of Defense have not been as successful as we could potentially be is in developing the institutions that support those CT forces. I remind people all the time that the CT forces—the tactical portion, the guys that are going to do the raids, kick down the doors—are the tip of the CT iceberg. In many of the countries where there is a significant threat, the rest of that iceberg is below the waterline. This includes the legal foundation for criminalizing terrorist activities, the police function for maintaining control and policing communities, the justice system for trying and incarcerating terrorists and keeping them in jail with a robust correctional facility, the intelligence that supports the military operations, and various other forms of support, as well as broader institution-building in those countries to help address some of the problems that contribute to terrorist recruitment—whether it’s poor governance, corruption, ethnic rivalries, etc. And those generally fall well outside the purview of the Department of Defense and all contribute to keeping the CT threat at a manageable level. It’s not going away anytime soon. But we have lots of tools outside Special Operations Forces to combat terrorism, and we need to make sure they’re fully engaged, particularly in the highest-priority areas.

Another key way that we can balance our commitment to the CT fight, and both Secretary Mattis and President Trump have put great emphasis on it, is getting our other partners and allies that have a vested interest in this CT threat, particularly our European allies, to step up and take a greater role and more responsibilities in these efforts.

CTC: For the general public, to use your analogy of the iceberg, the tip of the iceberg would be those very visual, kinetic aspects of what SOF does. But you’re also responsible for a range of other activities in the CT fight, such as civil affairs and information operations. Are you able to comment on the role of these missions in the CT fight and your assessment of how effective we’ve been in those domains, especially given the priority our adversaries place on the information battleground?

Mitchell: I think it’s fair to say that we’ve had limited success, at least in the CT fight, with our civil affairs efforts. It’s not through a lack of effort. But our civil affairs capabilities, while very useful, are limited in value in the CT fight, mainly because a lot of the larger-scale efforts are done under the State Department and USAID. And at a tactical level, we can assist, and they can and do make a difference. But the types of efforts that are going to make lasting, long-term change are really outside the Department of Defense roles.

Now on the information side, I think we have done a much better job than many people realize, and I also think we could still do a lot better. We have been very effective at utilizing information at the tactical fight. I wish I could say a lot more about it publicly, but the nature of information operations is such that much of it remains classified. In terms of the public efforts, though, that we can talk about, I think our Special Operations Forces and our MISO/PSYOPa folks have been leading the way and helping not just on the actual CT fight but on the counter-radicalization efforts and giving alternative perspectives, and again, competing against the narratives that are put out there by the Islamic State and, to a lesser extent, al-Qa`ida, and working with our partners at the State Department. I think we’ve done a fairly decent job. But we can do so much more.

So we’re looking at doing some different efforts. SOCOM will host a joint web ops center that will allow combatant commanders to conduct some of those influence campaigns. We at the Department of Defense and SO/LIC in particular are working with the State Department’s Global Engagement Center on a variety of efforts—not just in the CT realm but also in the great-power domain—and we are using the expertise from both our civil affairs and our PSYOP communities to support those efforts.

CTC: Before we switch gears, I wanted to ask you about the expanding role of women in combat. What is the vision for female roles in the SOF enterprise?

Mitchell: We’re still struggling to attract women to the Special Forces and SEALS. In the three years since all Special Operations career fields were opened to women, we’ve had a total of nine women volunteer to go through Special Forces Assessment and Selection. Only one has successfully completed SFAS. These small numbers are a byproduct, I believe, of the current paradigm for integrating women in the SOF enterprise at the tactical level. As a former Special Forces Group commander, I think our current paradigm of only allowing women to be a one-for-one replacement for male soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines is not the most effective use of the talents, skills, and interests that those women can bring to the Special Operations community. I think we need to fundamentally relook at how we are integrating women into SOF. There are numerous historical models like the OSS and British Special Operations Executive in World War II. We need to do this in a way that allows women to come into the force to fill roles that are genuinely complementary and expand our capabilities rather than a role that is simply additive. I believe we should reconsider the roles we expect women to play and the assessment and selection standards we apply to candidates. We also need to create career paths where women can come in, and not only gain experience but also build on that and have opportunities for long-term service in the Special Operations community with added responsibility and rank. If we really want to reach our full potential and help these great American patriots reach their full potential in SOF, we’ve got to offer a better opportunity to them.

CTC: To switch topics slightly, in 2014 you served as a director for counterterrorism at the NSC where you were directly involved in significant hostage cases and recovery efforts in a variety of countries around the world. Can you describe some of the challenges that the U.S. government faced in those efforts while you were there?

Mitchell: Sure. First, organizationally and from a policy perspective, the governing policy was outdated. It had been written in 2002 and was largely based off of the hostage experience in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. And it didn’t create the right type of organization to address the incredibly complex hostage situations that we encountered in 2014. They were multinational, particularly in Syria where we had hostages from probably a dozen different nationalities being held by the Islamic State, which adds a very complex dynamic to any policy decisions that we make as the United States. Second, there was nothing that was public about the policy, and so there was a great deal of misinformation about what it permitted and didn’t permit. And because it was classified, we weren’t in a position to share it with the families.

That caused a lot of consternation on their part because they didn’t have a firm grasp on the policy. Moreover, we didn’t have an organization in the United States government that was dedicated to providing them with the support that they needed. The FBI has their victims’ assistance, and they are absolutely fabulous. But there was also a lot of other aspects of being a relative of somebody held hostage that even the FBI couldn’t help with—for example, social media accounts or a bank account. Unless the hostages had left a power of attorney, their family members were unable to access their bank accounts or social media accounts to see if there had been withdrawals or postings. So there were a lot of challenges, and again, there was no organization that was dedicated to, first, meeting with the families and helping set their expectations and, second, guiding them through the byzantine nature of the U.S. government, especially as somebody who has not served in government, trying to understand the various roles and responsibilities.

And at that point, too, it was very difficult, particularly in Syria. It was a confluence of so many different factors that made it a hostage situation unlike any we had ever encountered before. First of all, we had no diplomatic relations with the host nation. We had closed our embassy I think in 2012. And the nation, Syria, was obviously in the midst of a civil war. That had a tremendous impact on our ability both to work with the host nation and to gather intelligence within Syria. Prior to 2014 and the initiation of airstrikes, we weren’t employing any of our ISR assets in the airspace over Syria, and on top of that, the Islamic State (and other terrorist organizations) had adopted technologies and communications procedures in the wake of the Snowden disclosures that neutralized some of our most effective intelligence-gathering tools against them.

So it presented a really difficult situation, and typically in a hostage situation, the ambassador and the country team has the lead. But in a country where we have no ambassador and no country team and there’s a civil war raging, who’s the right department to be in charge? Is it the State Department? Is it the FBI? Is it a foreign relations issue? Or is this a criminal conduct issue? And so frankly, we had a lot of tension in the interagency over roles and responsibilities and that was exacerbated, frankly, by the absence of a single point of contact for the families. Some families went from agency to agency seeking answers to their questions. They encountered well intentioned officials but some of the agencies were not willing to say, “The answer to that question is appropriately answered by another agency, and we can’t help you.” And again, it wasn’t done out of malice. It was done out of truly a spirit of wanting to help the families, but it created confusion.

We also had a tremendous intelligence gaps about what was really happening on the ground, only sporadic communication from the hostage-takers, and a lack of transparency on our overall efforts. And so again, it made it incredibly difficult. And the hostage situations in Afghanistan, Yemen, and Somalia all encountered similar issues that made it an unprecedented situation.

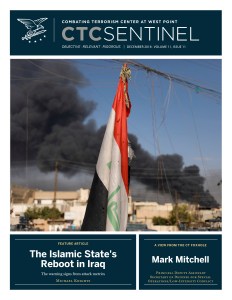

Colonel Mark Mitchell, then CJSOTF-AP Commander, with General Ray Odierno at Balad Air Base in Iraq in March 2010 (U.S. Department of Defense)

CTC: As you were looking to address some of these issues, the President ordered a review of these policies and the structure. You were involved in that process. What were the most important changes that were made, and have you been able to see tangible impacts of those changes?

Mitchell: I actually wrote the charter for the hostage policy review that outlined its objectives and the goals. And I think it did make some very important changes. First and foremost, one of my main recommendations was that the hostage policy, PPD-30, that emerged from this be an unclassified document so that both our families and our adversaries would know exactly what our hostage policy was. We had a number of public documents from U.N. Security Council resolutions, G8 communiques, etc. that talked about hostage policy, but again, the 2002 policy was classified. And so the new policy was issued as an unclassified document with a classified annex. That went a long way towards helping alleviate confusion about what our policy actually said.

Secondly, the creation of the Hostage Recovery Fusion Cell, hosted by the FBI, was an amazing step forward that has yielded tremendous results and allowed the interagency to have a single organization that was chartered specifically for hostage recovery and to bring all of the intelligence together in one place and ensure that it was shared and shared appropriately.

The third piece was to create an organization associated with the recovery cell that was dedicated to interfacing with the families and to provide a single point of contact for the families to make sure that they were getting a consistent message and the support that they needed and didn’t feel like they were being bounced around. There was that one person who could serve as an ombudsman for them and with whom they could develop a relationship. It also created a special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, known as the SPEHA, which I think has been an important step forward in terms of our international relations with other countries in terms of hostage affairs.

CTC: Going back to your roots a little bit, and your time in Afghanistan in 2001: the use of unconventional warfare to depose the Taliban, which you were directly involved in, was highly successful. But the transition to the next phase was arguably less successful, given that we’re still doing this today. Is supporting and stabilizing a regime inherently more difficult than overthrowing one? Or were there unique challenges in Afghanistan that might explain why we’re still struggling to find a solution there?

Mitchell: I think at a fundamental level, having participated in the initial phases of both the Afghanistan campaign and the Iraq campaign, I can say it is much easier to topple a regime than it is to stand up a government in its wake. There are just so many aspects of creating an effective governance structure. By its nature, it is more difficult and takes a lot more time. I think we made a mistake in Afghanistan by attempting to create a strong central government in a country that really never had a strong central government. Given its ethnic and religious fragmentation, the involvement of its neighbors, and a whole host of historical, cultural dynamics, Afghanistan is just very ill-suited to a strong central government.

There’s a reason why President Karzai was derided by some Afghans as the “Mayor of Kabul”: his authority didn’t extend much beyond the city limits. And so I think that’s the first thing that I would point out. We rushed to create a central government that was really never set up for success.

Secondly, I think that we grossly underestimated the resilience of the Taliban and the depth of their commitment to reestablishing their emirate. I think today we still struggle with that. Another challenge of the Taliban is they aren’t a monolith; there are a number of factions, and they all have slightly different goals and objectives and motivations. It makes it very difficult to come to any nation-level solutions. I also think that we simply did not invest enough in a political reconciliation with the Taliban. Granted, I have my doubts that the Taliban themselves could be effectively integrated into a democratic state. But there are other alternatives, and I don’t think they were fully explored. For example, some sort of partition or federal system that would allow a semi-autonomous Taliban-run area.

But that seems to be their number one goal, the reestablishment of that caliphate, and, until this year, I don’t think that we’ve invested enough in those political reconciliation talks. There’s no guarantee they’re going to work but it seems pretty clear to me that the situation in Afghanistan today does not have a strictly military solution, and our military efforts have to be in service of a larger, sustainable political solution–not just at the national level in Afghanistan, but all the way down to the local level. And that’s where this type of conflict is won and lost, at that local level, which also happens to be where the Taliban have arguably enjoyed their greatest success.

Mitchell in Afghanistan in 2001

CTC: This question of goals is an interesting one to conclude on. When you went in back in 2001, did you and your team have an image in your head of what a victory would look like? What was the goal at that time? How would you answer that question today? What does an acceptable end-state look like in Afghanistan?

Mitchell: For us, I think, when we first went in, especially given the numbers that we had, a successful end-state looked like us getting out of there alive. But really, overthrowing the Taliban regime and hunting down Usama bin Ladin and al-Qa`ida was our initial end-state. We hadn’t given a whole lot of thought, at least from our level, on what came next. Now, 17 years later, looking back, the right end-state has got to be a political accommodation that is sustainable, that brings an end to the fighting. An end-state that allows not only our Afghan partners but the Americans that have fought and died over there to look back and say it was worth it in the end. It has got to provide Afghans an opportunity to live their lives productively without being a threat to their neighbors, without hosting terrorist organizations, and that is sustainable over the long-term. The current environment is not sustainable.

At some point, the American people and our leadership are going to tire of making that commitment there. We’ve got to get to something that we can sustain with a much smaller footprint. And again, I think it’s got to be a political solution, not a military solution. CTC

Substantive Notes

[a] Military Information Support Operations/Psychological Operations

Skip to content

Skip to content