Abstract: From arrests and sentencing to post-conflict reintegration, mounting evidence suggests that men and women engaged in terrorism-related activity receive differential treatment from government institutions. Though myriad factors shape the result of any case, the evidence suggests gender has unjustly affected formal responses to individuals involved in crimes motivated by violent extremism, both inside and outside of judicial frameworks. By drawing from multiple sources, ranging from in-depth case studies to expansive datasets, this article shows that terrorism-related offenders who are women are less likely to be arrested, less likely to be convicted, and receive more lenient sentences compared to men; these findings are consistent with research on the unwarranted effects of gender on sentencing outcomes writ large.

“I am not an evil or malicious person,” Keonna Thomas reportedly explained to the judge at her sentencing hearing in September 2017, months after she pleaded guilty to attempting to provide material support to the Islamic State, “I was, I guess at one point, impressionable.”1 Though undoubtedly grounded in some truth, Thomas’ explanation mimics the language surrounding most women charged with Islamic State-related criminal offenses in the United States. From news media to defense attorneys, commentators regularly cast female terrorism offenders as naïve, gullible, susceptible targets of violent extremism, even when they admit their culpability by pleading guilty.2 While unsurprising, given that portrayals of women in terrorism tend to be misleading,3 it is crucial to examine the effects such rhetoric has on confronting women’s participation in the myriad manifestations of violent extremism. While the data suggests that women often receive differential treatment within the criminal justice system, this discussion explores the disparate treatment of terrorist offenders as it pertains to gender, both inside and outside of conventional legal frameworks.

Although defendants in terrorism cases are not immune to the broader effects of discrimination within the criminal justice system, discrepancies in the punishment of women compared to men in these cases appear consistent with differences in sentencing for non-terrorism-related criminal offenders. In the United States, formal sentencing guidelines are designed to achieve fair outcomes and prevent unnecessary disparities by keeping characteristics about a defendant, like gender, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, out of sentencing considerations.4 Despite this safeguard, evidence suggests that the federal court system in the United States is broadly more lenient on female defendants than their male counterparts, even when controlling for legal characteristics like criminal history.5 A 2015 study of felony cases found that women were 58 percent less likely to be sentenced to prison than men, and posits that judges were inclined to treat female defendants differently when they conformed to traditional gender roles.6 A few years earlier, a 2012 review of a swath of federal criminal cases discovered a considerable gender gap in sentence length distribution, which the author ascribes to a “winnowing” of defendants created by discretionary decisions at each procedural stage.7 Both patterns of judicial discretion and the process of sifting out women offenders at each encounter with the criminal justice process mirror the terrorism cases reviewed in this article. The following data and analysis indicate that women involved in crimes motivated by violent extremism are less likely to be arrested, less likely to be convicted, and finally sentenced at unequal rates. The abovementioned case of Keonna Thomas, among others, shows how gender dimensions become a part of legal proceedings.

Evidence presented in court filings shows that Thomas, a Philadelphia woman, was a vocal advocate for the Islamic State online for more than a year before her April 2015 arrest, using platforms like Twitter and Skype to advance its agenda.8 As early as August 2013, prior to the Islamic State’s official declaration of its caliphate, Thomas shared a picture of a child clad in camouflage wearing tactical gear and firearm magazine holsters with the caption, “Ask yourselves, while this young man is holding magazines for the Islamic state, what are you doing for it? #ISIS.”9 In private communications with three alleged separate co-conspirators, Thomas expressed her resounding support of the group and desire to travel to the region, as well as articulating her interest in becoming a martyr.10 An affidavit reveals authorities knew of Thomas’ electronic communications with a known “Somalia-based violent jihadi fighter originally from Minnesota,” a known “overseas [Islamic State] fighter,” and a “radical Islamic cleric located in Jamaica.”11 News reports and a legal document identified these co-conspirators as Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan (“Miski”), Abu Khalid Al-Amriki, and Sheikh Abdullah Faisal, respectively, three alleged established players in the Islamic State’s extensive virtual networks.12 As a testament to her support for the Islamic State and its fighters, Thomas married Abu Khalid al-Amriki online and arranged plans to meet the alleged Islamic State fighter Shawn Parson, who was believed to be a Trinidadian, in Syria.13 In electronic communications, after Parson said, “u probably want to do Istishadee (martyrdom operations) with me,” Thomas responded, “that would be amazing … a girl can only wish.”14

Between February and March 2015, Thomas prepared for her journey to Syria: she obtained a passport, researched indirect routes to Syria by way of Spain and Turkey, acquired a Turkish visa, and purchased plane tickets to fly from Philadelphia International Airport to Barcelona, Spain, on March 29, 2015. A mix of court documents shows that authorities derailed Thomas’ travel plans by conducting a search warrant of her belongings two days before her scheduled departure, seizing her passport and other relevant possessions.15 Following her arrest, Thomas initially pleaded not guilty.16 Months later, however, she admitted her culpability with one count of attempting to provide material support to a terrorist organization.17 For this offense, Thomas faced up to 15 years in prison. At the time, one of her defense attorneys said Thomas “look[ed] forward to putting this behind her and being a mother to her two young children.”18 Their specific mention of her children is interesting given that a review of literature regarding the sentencing of federal offenders notes that “having dependents (more specifically, dependent children) creates leniency at sentencing, especially for women.”19

By September 2017, U.S. District Judge Michael Baylson sentenced her to eight years, crediting the time she served while the justice system processed her case. In media coverage of her hearing, it is easy to find instances where news producers ruminate over Thomas’ gender and contextualize her case with clichés about women in terrorism.20 Anecdotally, reports most often cast Thomas as naïve, misled, and out-of-touch with reality. They also suggest that her desire for love and romance drove her to extremism. While problematic, these framing patterns are not wholly surprising as gender-related biases in media coverage of women in terrorism is an established phenomenon.21

Arguably more concerning are instances where Thomas’ defense drew on similarly biased tropes about women in extremism to obtain a reduced sentence for their client. Specifically, one article quotes a sentencing memo to the U.S. District Judge by Thomas’ lawyers, Elizabeth Toplin and Kathleen Gaughan, who advocated for a reduced sentence by explaining, “Ms. Thomas was a lonely, depressed, anxiety-ridden mother who spent too much time on the internet … By attempting to relocate to [Islamic State]-held territory and marry an [Islamic State] fighter, she never gave [the Islamic State] anything of value – except her love.”22 While considering the job of defense attorneys and federal defenders—to fight for the best interests of their client—it is crucial to examine the extent to which gender-linked biases might intentionally or inadvertently seep into the logic and outcome of legal decisions for terrorism-related crimes. Although sentencing guidelines are designed to act as a safeguard against unwarranted considerations regarding a defendant’s personal characteristics, it is fair to question the efficacy of such measures when Thomas’ defense rhetorically instrumentalized her gender.

Examining Broader Trends in the United States

Realistically, the process of measuring the effects of potential gender biases on the judicial proceedings of terrorism cases is easier said than done. In the United States, a range of procedural and logistical considerations complicate the process for punishing terrorism-related offenses at the federal level. Aside from the obvious effects of two federal material support statutes,23 with guidelines that offer judges some latitude in sentencing, factors like going to trial, facing additional charges, entering plea agreements, and cooperating with authorities can undoubtedly influence the time an individual serves for their crimes. These conditions allow the justice system flexibility in its treatment of vastly different terrorism cases, but make it difficult to impose consistent punishments for each individual. Again, flawed applications of the law that unjustifiably weigh gender are not unique to terrorism cases, but a growing body of evidence, like the case of Thomas, suggests that a concerning relationship exists between the gender of a terrorist offender and the nature of their interactions with the legal system.

A thorough review of Thomas’ case, paired with a comparative analysis of broader trends regarding the nexus of gender and terrorism-related crimes, offers a lens to identify vulnerabilities and refine the legal responses to violent extremism in America. While Thomas pleaded guilty and received an eight-year sentence as punishment, male Islamic State supporters in the United States traditionally face longer sentences for their crimes. According to the Extremism Tracker, a monthly infographic produced by the George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, the average duration for sentenced cases (male and female) in the “Islamic State in America” dataset was 13 years as of summer 2018.24

Although inferences are limited due to the size of the dataset, which includes 87 male cases and just nine female cases of sentenced individuals, further analysis reveals that Thomas was hardly unique in acquiring a shorter-than-average punishment: every woman sentenced in the Program on Extremism’s dataset received less than 13 years. While the average punishment for men amounted to 13.8 years,a the average period of incarceration for women was only 5.8 years.b c

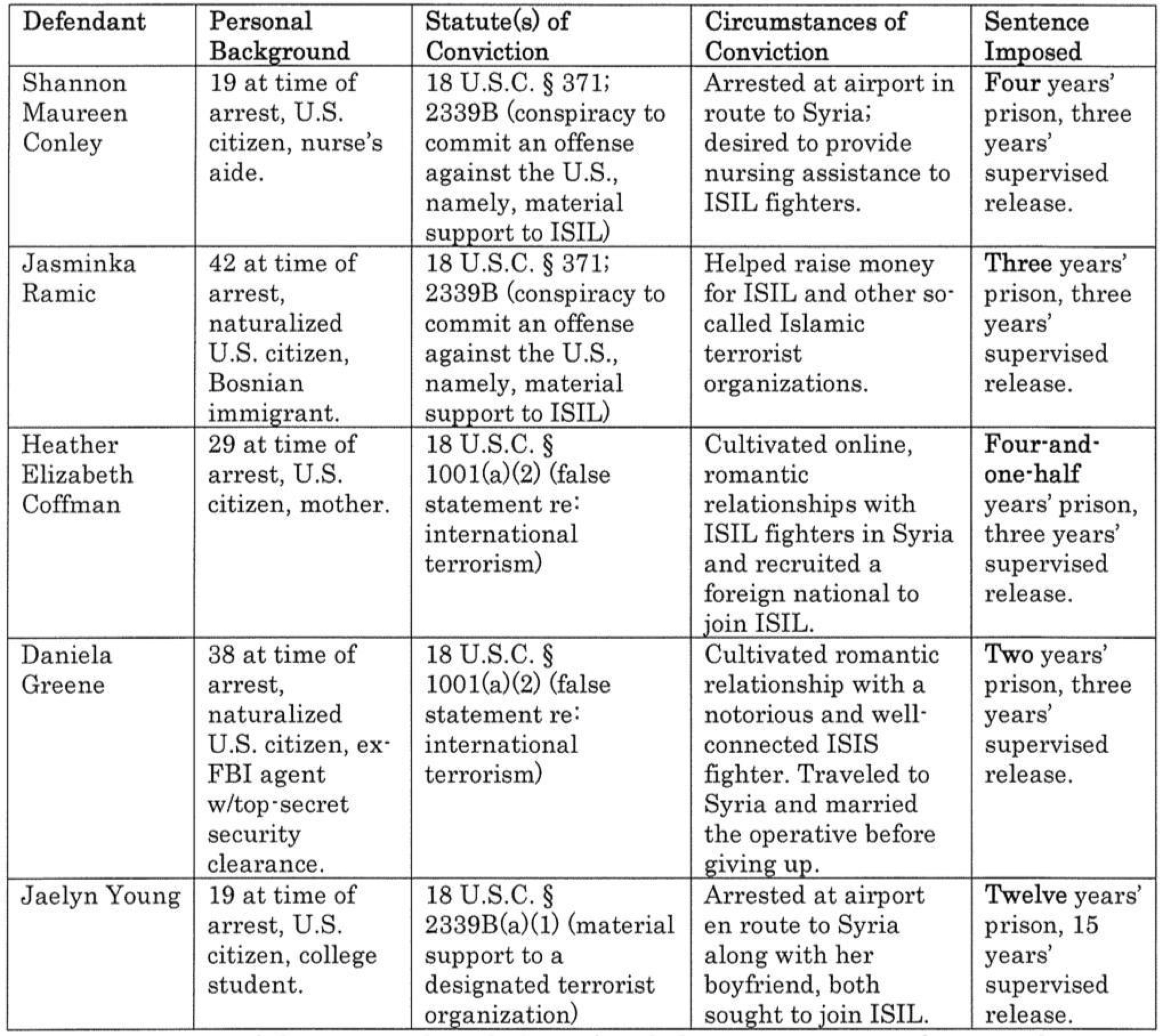

Returning to Thomas’ case and her corresponding court filings, it is crucial to note that her defense attorneys explicitly urged the court to issue a shorter punishment, asking for a sentence between two and four-and-a-half years to “avoid an unwarranted sentence disparity between Ms. Thomas and other women convicted of [Islamic State]-related offenses.”25 In the same sentencing memo, which the defense filed in August 2017, her attorneys say, “Ms. Thomas is among a handful of women who have been prosecuted (and sentenced) for [Islamic State]-related crimes between March 1, 2014 and May 8, 2017. These sentences range from two to twelve years’ incarceration, the median sentence being four years.”26 The memo presents the five relevant cases in a table (pictured below) and argues, “Only two of the women above faced charges stemming from conduct similar to that underlying Ms. Thomas’s conviction: Heather Elizabeth Coffman and Daniela Greene. Their sentences must serve as the benchmark for Ms. Thomas’s sentence.”27

Table presented by Thomas’ defense attorneys in the defendant’s sentencing memorandum and request for downward variance

In response to the argument made by Thomas’ defense, the U.S. Attorneys prosecuting Thomas pushed back on the defense’s logic for a shorter sentence, noting that the cases the defense cited as similar to Thomas’ case did not involve convictions under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B, the statute regarding material support to foreign terrorist organizations. Rather than comparing Thomas to other female defendants with terrorism-related cases, the government explains, “well-rounded analysis of convictions and sentences under 18 U.S.C. § 2339B reveals that terrorism defendants in Thomas’s position do generally receive lengthy sentences of incarceration.”28

Cases like Heather Coffman, a Virginia resident who pleaded guilty to making a false statement involving international terrorism,29 demonstrate similar trends regarding the strategic use of gendered framing in terrorism cases. In essence, Coffman shared her support for the Islamic State online and encouraged others to fight for the group, then provided false information to federal agents investigating her behavior.30 In a sentencing memo produced by Coffman’s defense,31 which asked for a lesser sentence, her attorney noted that her criminal activity “reflects a young, naïve woman who got caught up in a cause.” In discussing her relationship with fellow Islamic State sympathizers online, the memo noted that Coffman had “always been attracted to ‘bad boys.’” The defense also explained that Coffman was drawn to the Islamic State “like the forbidden fruit” and said that she “became obsessed with [the Islamic State] like she had become obsessed with the preppy and goth trends.”

By way of contrast, it is interesting to note that the government’s corresponding document about sentencing,32 which was authored by the prosecuting attorneys, addressed the mobilization of women in a completely different manner. The prosecutors argue, “this is an extremely serious offense where the defendant aligned herself with an extremely violent terrorist organization and tried to facilitate others’ attempts to join” the Islamic State in Syria. In a concluding paragraph, the document quoted Jayne Huckerby, a subject-matter expert, who said, “[the Islamic State] has been on a very strong female recruitment drive, and women are joining [the Islamic State] for a variety of reasons, many of which are the same as men.” The attorneys go on to explain that “Coffman is not an outlier. Other women must be deterred from helping terrorist groups via the internet.”

The differing appraisals of Coffman’s contributions to the Islamic State, which were supportive and facilitative in nature, exemplify the difficulty in discerning reality and responding proportionally to the participation of women in terrorism. One analysis of female jihadis in the United States finds that women can make meaningful contributions to the efforts of violent extremist groups without engaging in violence.33 In this capacity, functions such as cooking, smuggling, teaching, fundraising, childbearing, and proselytizing contribute to the morale, strength, and survival of an organization. In the limited purview of the Islamic State in U.S. cases, the gender of a defendant factors into some legal assessments about the severity of an individual’s crime and even discussions regarding sufficient punishment for terrorism-related offenses. In order to examine the extent to which this sliver of evidence reflects broader trends, it is useful to draw from a larger dataset.

Analysis of data assembled by the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) adds meaningful, quantitative insights that further contextualize the discussion of gender and violent extremism.34 Specifically, the Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) dataset “contains deidentified individual-level information on the backgrounds, attributes, and radicalization process of over 1,800 violent and non-violent extremists who adhere to far right, far left, Islamist, or single issue ideologies in the United States” from 1948-2016.35 The sample includes cases of people who radicalized to the point of committing ideologically motivated illegal acts, joining a designated terrorist organization, or associating with an extremist organization.

The PIRUS dataset, comprised of 1,685 male profiles and 182 female profiles, categorizes and documents case-specific details such as the severity of an individual’s criminal activity, as well as their role in and membership to a group. Although men and women differ in their numerical rates of participation, the precise nature of their respective activities share some critical features. A side-by-side comparison of the results for radicalized men and women, proportional to their genders, allow researchers to identify relevant similarities and flag instances where the experiences of extremists diverge. Relative to their genders, men and women striving to conduct plots demonstrate similar rates in their acquisition and possession of related materials, and attempts to carry out a plan. In fact, the data shows that 26 percent of men in the dataset and 26 percent of women successfully executed plots. Both demographics were equally prone to hide or conceal plot-related information, and the same proportion of men and women shared a connection with extremist groups prior to engaging in ideologically motivated radical behaviors.

Although men conspired or conducted violence against others at slightly higher rates, including armed robbery and assault with a deadly weapon, women participated in violence against property, including arson, and acts like illegal protesting and criminal trespassing proportionally more than their male counterparts. A similar percentage of men and women sought training experience or offered material support to a violent extremist organization. Both showed similar rates for other actions including white-collar crimes, threatening others, and recruiting others for violent groups, and even non-criminal activity. Even with marginal, gender-linked caveats in mind, the evidence broadly suggests that radicalized men and women are not so different in the severity of their crimes.

Despite some striking parallels between radicalized American men and women, evidence indicates that these demographics receive different treatment by authorities. For example, authorities arrested and indicted approximately 73 percent of men in the PIRUS dataset, compared to 66 percent of women, for ideologically motivated crimes. This factor likely adds to the disparity in conviction rates between the genders, as courts convict about 38 percent of men compared to 29 percent of women. Although the precise causes require further examination, the PIRUS dataset suggests that the average rate for arrest, indictment, and conviction differs between males and females. Though myriad factors likely contribute to these results, not exclusively gender, the phenomenon requires further discussion beyond legal responses to radicalized individuals in the United States.

Transcending Borders and Conflicts

First and foremost, assumptions that women are naïve or duped into supporting political violence are not confined to the United States. A policy brief by the PRIO Centre on Gender, Peace, and Security notes that high-profile court cases in Western Europe show a similar pattern where female defendants received lesser punishments than the average sentences in their respective countries.36 “This seems to indicate a potential tendency towards women not being prosecuted for membership in [the Islamic State] to the same extent that men are.” Moreover, the brief argues that the effects of this inclination to make light of women’s involvement is vital to recognize, as preconceived notions about gender and conflict inform political and judicial responses to terrorism, potentially creating vulnerable security gaps.

Sensationalized misnomers like “Nazi bride,” “black-widow,” and “jihadi bride” flow across media reports and skew perceptions as they enter discourse surrounding women’s participation in extremism.37 In both public opinion and a court of law, this vocabulary may paint women as mere accessories to, rather than perpetrators, facilitators, and supporters of violent extremism, reinforcing narratives that diminish the culpability of an offender. In Germany, the case of Beate Zschäpe, a member of the Nationalist Socialist Underground, serves as one illustrative example. On trial for plotting 10 murders, two bombings, and 15 robberies in a grisly series of racially motivated attacks, Zschäpe’s defense attorneys portrayed her as “merely the submissive lover of two murderous men.”38 In a separate case in the United Kingdom, Farhana Ahmed pleaded guilty to four counts of encouraging terrorism and disseminating terrorist publications but was spared jail time after her lawyer argued she was a “good mother” who was led astray. After handing down a suspended sentence, the judge told Ahmed, “the sooner you are returned to your children, the better for all concerned.”39

Problematic and inconsistent approaches to women fighters and supporters spread beyond the realm of domestic terrorism cases, extending to full-blown insurgencies and civil wars. Some of the starkest examples of differential treatment of men and women in violent political groups come from Disarmament, Demobilization and Rehabilitation (DDR) programs, which are conventionally designed to separate people from extreme networks. In Sierra Leone, for example, eligibility for entry into the DDR program was contingent on presenting a weapon to exchange, effectively barring women who served as spies, logisticians, or care workers whose operational responsibilities did not include wielding guns.40 DDR program language referred to Sierra Leonean women soldiers as “wives” or “camp followers,” ignoring the broader operational roles they played in the war.41

Just as it is difficult to draw a line between support roles and operational roles, the division between victims and perpetrators is not always clear-cut. In some cases, women forced into a group come to embrace their position as supporters or violent actors. In Women and the War on Boko Haram, Hilary Matfess, reflecting on interviews with female affiliates of the group, notes that female members of the sect often claimed to be ignorant of the organization’s use of violence to deflect accountability.42 Regardless, political, military, and humanitarian responses to Boko Haram fail to acknowledge gender-linked complexities in a serious manner. Matfess explains that “this oversight not only prevents effective counter-insurgency strategy, but also puts women at a disadvantage in the post-conflict era of demobilisation and reintegration.” 43

Numerous studies and analyses show that similar interlocking factors draw men and women to terrorism, including ideology, personal ties, discrimination, and a desire for belonging.44 Overarching discrepancies in the responses to men and women’s participation in violent extremism point to a worrying pattern that indicates that political and legal systems are not applied equally, even when individual paths to radicalization and actions in support of extremist groups are either comparable or complementary.45 Ultimately, noting the existence and prevalence of this broader phenomenon is not to say that all women with alleged ties to extremist groups are guilty of grave offenses and deserve harsh prosecution or robust deradicalization programming. In the case of the Islamic State, many women connected with the movement are indeed victims of coercion and force as a result of a strategic and systematic campaign of sexual violence.46 These experiences warrant responses that make appropriate considerations for the conditions of an individual’s membership. However, blanketly perpetuating a narrative of female victimhood ignores the agency of women like Keonna Thomas, the Philadelphia woman who expressly and repeatedly proclaimed her intent to advance the Islamic State agenda and planned to travel to Islamic State-controlled territory.47

Those advocating for more just responses to participation in violent extremist groups must weigh the implications of such findings in recommendations for enduring challenges, namely the processing of alleged Islamic State members on trial in Iraq. At present, it is unclear how gender disparities are playing out on the ground. A recent news article about the notoriously short Iraqi terrorism trials notes that “in rare cases, individuals have been returned to their home countries, such as a group of four Russian women … after Iraqi authorities concluded they had been tricked into coming to Islamic State territory.”48 Without in-depth knowledge of the cases, it is impossible to discern the authenticity of each woman’s claims, but the narrative is consistent with the overarching argument that female supporters are treated as less responsible for their involvement in terrorist groups.

There are serious concerns about Iraq’s legal response, such as lack of due process and harsh sentencing for men and women.49 At the same time, recommendations from human rights organizations that sidestep the roles and motivations of female supporters can create counterproductive practices for dealing with women in the group. One Human Rights Watch researcher makes the case that Islamic State trials are unjustly harsh in their treatment of women and implores Iraqi authorities “to prioritize the prosecution of those who committed the most serious crimes.”50 The article suggests, “for those suspected only of membership in [the Islamic State] without evidence of any other serious crime, the authorities should consider alternatives to prosecution,” pointing to women who receive harsh sentences “for what appears to be marriage to an [Islamic State] member or a coerced border crossing” as instances where Iraqi courts should focus on other priorities.51 While likely well-meaning and pragmatic in processing the deluge of cases facing the Iraqi government, this recommendation will be unlikely to address entrenched problems at the nexus of gender and prosecution for terrorism-related offenses.

Implications

In the United States, authorities have already released some of the women serving short sentences for Islamic State-related crimes while others are nearing the end of their time in prison. This is worrisome given the lack of infrastructure to support these individuals, as few formal deradicalization and reintegration initiatives exist. Furthermore, if the criminal justice system struggles to recognize instances where extremist women pose credible threats and fails to facilitate meaningful interventions and rehabilitation for such offenders, it is hard to know if efforts to provide an alternative to legal recourse will prove fruitful. A powerful illustration of this problem is the abovementioned case of Heather Coffman, whose defense attorney once compared her commitment to the Islamic State to past interest in “preppy and goth trends.” After serving a four-and-a-half year sentence, authorities released Coffman from prison. According to a news report, Coffman’s views “had scarcely moderated” during her incarceration, and she resumed posting pro-Islamic State materials and ultra-conservative content online.52 As the cases of female jihadis in the United States suggest, differential treatment sets a counterproductive precedent for gender and extremism; this response could allow women to face fewer consequences for their contributions to terrorist groups or slip through the cracks when they need support.

While inconsistencies are most apparent in the legal system’s treatment of female terrorists, the roots of this problem extends far beyond defense attorneys, prosecutors, and judges. News media that sensationalize women in terrorism, or exoticize them as transgressive or misled enigmas, misguide public opinion. Academics who ignore gender in their studies of radicalization and recruitment dynamics produce incomplete analyses of current trends. Policymakers who exclusively cast women as victims of conflict create blind-spots in strategies to counter terrorism and violent extremism. Concurrently, the efforts of humanitarian and human rights groups struggle to grapple with situations where women are both perpetrators and victims of violence. Consequently, the responsibility for creating more equitable and practical approaches to address violent extremism lies with every sector. By comprehending how gender dynamics weave into the fabric of different organizations, including those that relegate women to support functions, entities tasked with preventing terrorism can more adeptly and sustainably confront violent extremist networks in their entirety.

From arrest to sentencing to post-conflict reintegration and disarmament programming, evidence suggests that governments tend to be less responsive to women in terrorism compared to their male counterparts. Such disparities in treatment have numerous consequences for justice, security, and the prevention of violent extremism and subsequent conflict. Equal and proportional applications of the law require courts to confront stereotypes regarding gender, race, religion, and citizenship, among other factors. In the processing of alleged extremists, the criminal justice system must transcend facile gender stereotypes and come to a better understanding of how both men and women engage with violent extremism. Falling back on tropes of female victimhood, rather than applying the law on a case-by-case basis, has real implications for processing potentially threatening actors. When it comes to terrorism cases, bias in the judgment of women offenders undermines the promise of uniform treatment under the law and poses potential threats to national security. Regardless of gender, disparate treatment of terrorist offenders is a disservice to defendants, their communities, the criminal justice system, and broader efforts to confront violent extremism in the United States and abroad. CTC

Audrey Alexander is a Research Fellow at the George Washington University’s Program on Extremism. She specializes in the role of digital communications technologies in terrorism and studies the radicalization of women.

Rebecca Turkington is the Assistant Director of the Women and Foreign Policy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). Prior to joining CFR, she was a program manager at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace & Security where she researched women’s participation in peace processes, transitional justice, and countering violence extremism.

The authors would like to thank the staff at the Program on Extremism and Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace & Security, as well as Shaina Mitchell, for their contributions to this report.

Substantive Notes

[a] The five number summary, plus mean, for women’s sentences in the dataset by months: Minimum: 24, Quartile 1: 26, Quartile 2: 54, Quartile 3: 96, Max: 144, Mean: 70. The five number summary, plus mean, for men’s sentences in the dataset by months: Minimum: 0, Quartile 1: 66, Quartile 2: 120, Quartile 3: 240, Max: 582, Mean: 166.

[b] Researchers used the Wilcoxon Sign-Rank test after separate histograms of sentence length (in months) by gender revealed that the distributions for men and women were not symmetric. The Wilcoxon Sign-Rank test produced the following results: Test Statistic=191.5, p-value= 0.01198. This outcome suggests a statistically significant difference exists between the sentence lengths of women compared to the sentence lengths of men.

[c] Compared to individuals (both men and women) that were exclusively guilty of attempting to provide material support to a foreign terrorist organization, and not guilty of any other charges, Thomas received about two years less than the average sentence of approximately 10.3 years (as of summer 2018). The sample size in this category makes it difficult to assess whether this is a statistically significant difference.

[2] Dominic Casciani, “Derby Terror Plot: The Online Casanova and His Lover,” BBC, January 8, 2018; “Would-be ‘jihadi bride’ Angela Shafiq ‘a loner,’” BBC, September 8, 2015; Meghan Keneally, “Teen ‘In Love With ISIS Fighter’ Met With Authorities 8 Times Before Being Arrested,” ABC News, July 3, 2014; “Denver Teens Encourages to Join ISIS by ‘Online Predator,’ Friends Stay,” Guardian, October 23, 2014.

[5] Ibid.

[8] “Criminal Complaint and Affidavit,” USA v. Keonna Thomas, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 2015.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[13] “Government Sentencing Memorandum,” USA v. Keonna Thomas, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 2017, p. 2.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid. See also “Search and Seizure,” USA v. Keonna Thomas, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 2015.

[16] “Not Guilty Plea From Philly Mom Who Wanted to Die for ISIS: Feds,” NBC Philadelphia, May 7, 2015.

[17] “Transcript of Plea Hearing,” USA v. Keonna Thomas, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 2016.

[18] “Philly Woman Pleads Guilty to Trying to Join ISIS,” NBC 10 Philadelphia, September 20, 2016.

[19] Doerner and Demuth, pp. 242-269.

[20] For background on these clichés, see Brigitte L. Nacos, “The Portrayal of Female Terrorists in the Media: Similar Framing Patterns in the News Coverage of Women in Politics and in Terrorism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 28:5 (2015): pp. 435-51.

[21] Eileen MacDonald, Shoot The Women First (New York: Random House, 1991); Alisa Stack, “Zombies versus Black Widows: Women as Propaganda in the Chechen Conflict,” in Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry eds., Women, Gender, and Terrorism (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011), pp. 83-95; Ashleigh McFeeters, “Gender and Terror – Woman First, Fighter Second?” Womenareboring (blog), January 13, 2017.

[24] These calculations are based on the authors’ access to the GW Program on Extremism’s “ISIS in America” dataset as of July 31, 2018. For more information, visit https://extremism.gwu.edu/isis-america, and see the “GW Extremism Tracker” infographic for July 2018. That infographic and corresponding dataset, including average sentence, encapsulates the data that is further disaggregated in this analysis.

[25] “Defendant’s Sentencing Memorandum and Request for Downward Variance,” USA v. Keonna Thomas, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 2017.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Government Sentencing Memorandum.”

[29] “Judgement in a Criminal Case,” USA v. Heather Elizabeth Coffman, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division, 2015.

[30] “Criminal Complaint and Affidavit,” USA v. Heather Elizabeth Coffman, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division, 2014.

[31] “Defendant’s Position on Sentencing,” USA v. Heather Elizabeth Coffman, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division, 2015.

[32] “Position of the United States on Sentencing,” USA v. Heather Elizabeth Coffman, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division, 2015.

[34] “START Homepage,” National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism.

[37] Stack, pp. 83-95; Mia Bloom, “Bombshells: Women and Terrorism,” Gender Issues 28 (2011): pp.1-21; Maura Conway and Lisa McInerney, “What’s love got to do with it? Framing ‘JihadJane’ in the US press,” Media, War & Conflict 5:1 (2012): pp. 6-21.

[38] Jacob Kushner, “10 Murders, 3 Nazis, and Germany’s Moment of Reckoning,” Foreign Policy, 2017.

[42] Hilary Matfess, Women and the War on Boko Haram: Wives, Weapons, Witnesses (London: Zed Books, 2017).

[43] Ibid.

[44] Loken and Zelenz, pp. 45-68; Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry, Women, Gender, and Terrorism (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

[47] “Transcript of Plea Hearing,” USA v. Keonna Thomas, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 2016; “Criminal Complaint and Affidavit,” USA v. Keonna Thomas, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 2015.

[49] “UN Rights Wing ‘Appalled’ at Mass Execution in Iraq,” UN News, December 15, 2017.

[51] Ibid.

Skip to content

Skip to content