Abstract: The Islamic State has built up an external operations network with a hub on Libyan soil and spokes connecting it to nodes of Islamic State supporters within the Libyan and Tunisian diaspora in Europe. While much is still unknown about the reach of the network, the group has been linked to a series of major terrorist attacks and plots against Westerners in Europe and Tunisia. Despite setbacks for the Islamic State in Libya, international attack planners on Libyan soil continue to pose a threat on both sides of the Mediterranean.

On May 22, 2017, Salman Abedi, a dual British-Libyan national, killed 22 concert-goers and injured more than 100 others during an Ariana Grande concert at Manchester Arena in the United Kingdom. Abedi detonated a bag filled with acetone peroxide (TATP) and shrapnel—the same explosive used in the Brussels attacks the previous year. His travel to Libya before the attack quickly led investigators to focus on possible links to the Islamic State’s Libyan branch. Following the Berlin Christmas market attack by Anis Amri in December 2016, investigators suspect the Manchester bomber may be the second most recent jihadi attacker in Europe to receive directions or support from the Islamic State in Libya.1

Jihadi groups, and particularly those close to the Islamic State, gained a foothold in Libya in the aftermath of the revolution there against Muammar Qaddafi in 2011. The Tunisian government’s ban of Ansar al-Sharia two years later boosted the influx of jihadis from the neighboring country. An estimated 3,000 Tunisians traveled to Syria and Iraq as foreign fighters.2 A significant number of them joined the ranks of Jabhat al-Nusra or the Islamic State in Syria after receiving military training in Libyaa and using contacts to local jihadi groups as gatekeepers.3

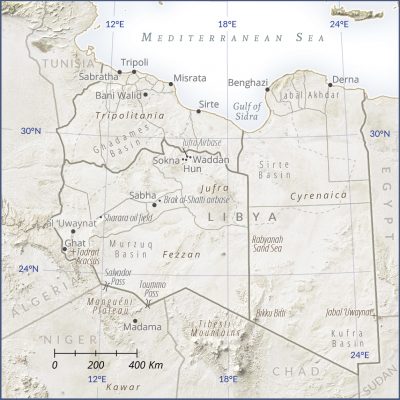

Libyans also traveled to Syria and joined groups like the Islamic State-affiliated Katibat al-Battar al-Libi (KBL), which was founded by jihadis from Libya. The group recruited a large contingent of Libyan and Tunisian fighters in the early stage of the Syrian civil war. When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared himself the leader of a new ‘caliphate’ in Mosul in July 2014, KBL pledged its allegiance, and soon many local KBL fighters were involved in founding the first Libyan Islamic State wilaya in Derna (Barqa). A year later, the Islamic State captured Sirte, where it set up training camps in the vicinity.4 It also established training camps near Sabratha to the west of Tripoli,5 a town that serves as a major smuggling hub for refugees on their way to Europe.6

These camps and localities have been linked to a series of terrorist attacks and plots in Europe and North Africa, including, as this article will outline, the Bardo, Sousse, Berlin, and Manchester attacks. The open source evidence that has surfaced so far suggests an Islamic State external operations network has been built up with a hub on Libyan soil and spokes connecting it to nodes of Islamic State supporters within North African, and specifically Libyan and Tunisian, diasporas in France, Belgium, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, and other European countries.

This article makes some preliminary observations about this network. The picture is blurry because information is still fragmentary and because of difficulties in assessing the reliability of information that has surfaced in the open source. Moreover, media reports sometimes contain assumptions about the nature of the linkages between terrorist actors that are speculative. But despite these limitations, the picture has enough resolution to bring into focus the terrorist threat emanating from Libya.

The Libya Nexus to Tunisia Terror

The first observation is that the Islamic State built up an external operations attack hub in Sabratha (near the Tunisian border) to facilitate attacks in Tunisia staffed in part by Tunisians with deep connections to extremists in Europe. In March 2015, the Tunisians Yassine Labidi, Saber Khachnaoui, and a third unknown person shot 22 people—mainly Western tourists—at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis. Three months later, 38 people, including 30 British tourists,7 were shot dead on a beach in Sousse. Investigations of Seifiddine Rezgui, the Tunisian gunman responsible for the attack, revealed he was closely linked to the Islamic State cell responsible for the Bardo attack. Rezgui trained together with one of the Bardo perpetrators in a camp in the vicinity of Sabratha.8

Fragmentary information has emerged on the ringleaders behind these attacks. According to confessions by suspects and witness accounts, the cell’s “mastermind,” Chamseddine al-Sandi, recruited all the attackers, paid them to go to Libya for military training, and gave them orders for the attacks.9 Authorities allege another senior figure in the external operations cell behind the Sousse and Bardo attacks was the Tunisian Moez Ben Abdelkader Fezzani (jihadi kunya: Abu Nassim), who once lived in Milan and waged jihad in Bosnia and Afghanistan before taking up a leadership role in Sabratha.10 In March 2016, Fezzani also reportedly oversaw an Islamic State attack on Tunisian security services in the border town of Ben Gardane, killing 17.11 Investigators have also focused on another Italian-Tunisian, Noureddine Chouchane, who was a KBL emir in Sabratha before his death in a U.S. airstrike in February 2016.12 Chouchane, originally from Sousse, lived in Novara, Italy, until 2011, and cultivated contacts with Italian foreign fighters in Syria.13

The Libya Nexus to France-Belgium Terror

The second observation is that the network behind the worst attacks carried out so far in Europe had deep connections to the Libyan and Tunisian contingent of Islamic State fighters in Syria. Pieter Van Ostaeyen, in this publication, raised the possibility that figures inside KBL possibly encouraged Paris attack ringleader Abelhamid Abaaoud to set in motion a campaign of terror in Europe. Abaaoud joined KBL in the summer 2013, and he presumably became familiar with the group’s inghimasi operations—suicidal assaults involving gunmen wearing suicide vests.

Van Ostaeyen also noted that Bilal Hadfi, another of the Paris attackers, communicated with KBL members online,14 and Verviers plotters Soufiane Amghar and Khalid Ben Larbi trained and fought in the ranks of KBL.15 During the time Abaaoud coordinated the Verviers plot, he reported up to a senior Islamic State operative called ‘Padre,’ according to court documents. According to social media analysis undertaken by Guy Van Vlierden, there are strong indications ‘Padre’ was one and the same as a Belgian KBL member from Molenbeek called Dniel Mahi.16 It should be noted that the KBL-recruited Islamic State fighter Abaaoud was also linked to the March 2014 attack on the Jewish Museum in Brussels by Mehdi Nemmouche, the August 2015 Thalys train attack by Ayoub el-Khazzani, as well as other plots directed against France.17

The Libya Nexus to U.K. Terror

A third observation is Manchester attacker Salman Abedi built up connections to the Islamic State, including in Sabratha where the Bardo and Sousse attacks were staged. Subsequent to Abedi’s suicide bombing at Manchester Arena, the Special Deterrence Force, a Tripoli-based militia that reports to the Interior Ministry, arrested his younger brother Hashem in the Libyan capital. According to his purported confession, Hashem Abedi stated that he and Salman were members of the Islamic State, that he was aware of his brother’s plot, and that he himself had planned the assassination of a German U.N. envoy in Libya.18 According to The New York Times, Salman Abedi met with Islamic State KBL members in Tripoli and Sabratha several times and kept up the contact when he returned to Manchester.19

In 1993, Salman and Hashem’s father, Ramadan Abedi, who denies allegations he was a one-time member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), fled the country to settle in Manchester.20 As Libyan revolutionaries put pressure on Qaddafi in 2011, Ramadan Abedi took his three sons to Tunisia, where he worked providing logistics for rebels in western Libya, and soon relocated to Libya. The senior Abedi joined the Tripoli Revolutionary Brigadeb under the command of Irish-Libyan (and later mayor of Tripoli) Mahdi al-Harati. Salman and Hashem appear to have received some training by the militia forces and to have fallen in with a contingent known as the “Manchester fighters.”21

At some point, Salman Abedi allegedly developed links to the radical preacher Abdu Albasset Egwilla, who had previously been based in Ottawa, Canada, but it is unclear what impact the preacher had on him.22 As part of its investigations following the Manchester attack, the Libyan Special Deterrence Force Rada also reportedly focused on an associate of Egwilla named Abdel-Razzaq Mushaireb, who was arrested in September 2017. The imam of the Ben Nabi mosque in Tripoli’s Mansoura district allegedly recruited fighters for the Islamic State in Sirte and Benghazi. Mushaireb was involved with the Islamist youth movement Qudwati, of which Abedi was also reportedly a part. The group is accused of being a recruitment conduit to the Islamic State.23 Without giving any reason, Rada released Mushaireb earlier this month.24

Another potential connection Abedi had to the Islamic State was through the Manchester Libyan Islamic State recruit Mohammed Abdallah. Abdallah, who was arrested after returning to the United Kingdom in September 2016 and convicted of fighting for the Islamic State earlier this month, traveled to Syria in 2014 with the help of his brother who was close friends with Salman Abedi.25

The Libya Nexus to Germany Terror

A fourth observation is there is a strong Libya nexus to attacks and plots by Tunisian Islamic State-aligned jihadis in Germany. According to a study of the December 2016 Berlin truck attack by Georg Heil for this publication, its perpetrator, Anis Amri, was communicating via the messaging app Telegram with two persons using Libyan phone numbers linked to the Islamic State at least until February 2016.26 German journalist Florian Flade reported that according to German security agencies monitoring these conversations, there was a “high probability” that Amri’s interlocutors using the Libyan cell phones were Tunisians who had joined the Islamic State in Libya and that he asked them for help in the course of their conversations with a suicide bombing in Germany.27 While these conversations, as reported, did not specifically relate to the subsequent Berlin truck attack, they illustrated that Amri was operationally in touch with Islamic State figures in Libya. In January 2017, two U.S. Air Force B-2 bombers struck two Islamic State camps southwest of Sirte after intelligence reportedly indicated the possible presence of external attack plotters there with suspected links to the Berlin attack. Then U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter said the strikes were “directed against some of ISIL’s external plotters who were actively planning operations against our allies in Europe … and may also have been connected with some attacks that have already occurred in Europe.”28

Anis Amri in his video claiming allegiance to the Islamic State (Amaq)

The Berlin attacker was connected to a number of Tunisian jihadis inside Germany. Although only fragmentary information has surfaced in the open source on these cases, other investigations have revealed a web of ties between Tunisians jihadis inside Germany and the Islamic State’s external operations outfit in Libya.29 A case in point was an alleged Islamic State recruiter, Haikel S., wanted by Tunisian authorities for his suspected involvement in the Bardo and Ben Gardane attacks who was arrested in Frankfurt earlier this year. In February 2017, police raided several locations in Frankfurt, Offenbach, and Darmstadt, in the state of Hessen, and arrested 16 suspects. Haikel S., the alleged head of the cell, regularly visited the Bilal mosque where Abu Walaa, an alleged Islamic State recruiter linked to Amri, occasionally held sermons as a guest preacher, but there is no evidence Haikel S. knew Abu Walaa.30 Investigators believe Haikel S. plotted terrorist attacks in Germany on behalf of the Islamic State.31

The Libya Nexus to Italian Terror

A fifth observation is there is a significant nexus between terrorist activity in Italy and the Islamic State’s branch in Libya. Several individuals implicated in plots by the group’s external operations branch in Libya have had strong links to extremist networks in Italy.

Ever since Anis Amri was shot by Italian police at the train station of the Milanese suburban town of Sesto San Giovanni on December 23, 2016, it has remained unknown whether he arrived in Milan accidentally or intentionally chose the northern Italian city as the waypoint of his escape route southward because he knew extremists who could help in the city. It was in Italy where Amri firstly set foot on European soil and eventually radicalized. He lived shortly in Aprilia, as did the Tunisian Ahmed Hannachi who stabbed two women to death in front of the Marseille train station on October 1, 2017, raising the possibility, which has not been confirmed, of a link between the two men.32

Moez Fezzani, one of the alleged planners in the cell behind the Bardo and Sousse attacks, grew up in Milan and attended the Islamic Cultural Institute (ICI), a mosque led by the radical preacher and Bosnia jihad recruiter Anwar Shabaan. This “Bosnian network” was linked to a series of plots in Europe.33 Fezzani eventually traveled to Afghanistan and in 2002 was arrested in Peshawar and imprisoned in Bagram.34

He was placed under investigation on his return to Italy and deported to Tunisia in 2012. Like other prominent Tunisian jihadis from Italy, he is said to have immediately joined the Tunisian branch of Ansar al-Sharia.35 After fighting with Jabhat al-Nusra and later with the Islamic State in Syria, Fezzani relocated to Libya again. As a KBL leader in Sabratha, he continued to exercise influence on Italian jihadis, especially in the Lombardy region.36

After the Islamic State lost ground in Libya, Fezzani was detained in Sudan under mysterious circumstances in November 2016 and deported to Tunisia to face trial for sponsoring the Bardo attack.37 After recapturing Sirte from the Islamic State in August 2016, Libyan agents found documents revealing the existence of an Islamic State-affiliated cell in Milan associated with Fezzani. Italian investigators suspected he had reactivated his network in the area to recruit fighters for the Islamic State.38

There have also been terrorism arrests in Italy that appear to have links to the Islamic State’s external operations hub in Libya. In May 2015, Italian police arrested Moroccan Abdel Majid Touil in the Milanese suburb Gaggiano on an international warrant issued by Tunisia over his possible logistical support for the Bardo attack. Authorities stated that Touil entered Italy from Libya illegally by boat only one month before the attack.39 Due to lack of evidence, however, Touil was released in October of the same year.

What is Known and Unknown

The post-Qadaffi era has seen a growth and consolidation in jihadi networks in Libya. After civil war broke out in Syria, Libya became a facilitation hub for Tunisian foreign fighters and others on their way to Syria. Many of them were provided paramilitary training in various camps there.

The open source analysis strongly indicates that the Islamic State built up a base in Sabratha for external operations focused on Tunisia. Consisting of a considerable proportion of Tunisian jihadis, this network was responsible for the Ben Gardane raid and the Bardo and Sousse attacks.

Likewise, terrorist activities in Europe were linked to Libyan and Tunisian Islamic State operatives. Firstly, the network behind the Paris and Brussels attack had close connections to the Libyan and Tunisian contingent in Syria. Secondly, Manchester attacker Salman Abedi reportedly built ties to Islamic State members in Libya, including in Sabratha. Thirdly, there exists a strong Libyan nexus to attacks and plots by Tunisian Islamic State-aligned jihadis in Germany. And, finally, several of those involved in plots by the external operations branch in Libya have had strong links to extremist networks in Italy.

However, these are only initial observations and conclusions. The available open source data leaves several important questions unanswered. The specific nature of many of these connections are not yet clear. While apparently significant players such as Moez Fezzani have been identified, there is still only a very thin information in the open source on the identity and role of senior figures in the Islamic State external operations efforts in Libya. The degree of direction by the Islamic State in plots like the Berlin and Manchester attack are not yet clear. And a great deal remains unknown about the connectivity between the Islamic State’s external operations branches in Libya and Syria.

What is clear, however, is there is a significant terrorist threat emanating from Libya. It is hard to forecast trends based on the available data. The Islamic State’s loss of territory in Syria and Iraq will likely result in the decentralization and fragmentation of the Islamic State’s external operations efforts and a greater reliance on terrorist attacks “remote-controlled”40 by Islamic State cyber-coaches in places where Islamic State operatives can still operate without facing arrest like Libya. One continued concern is the group may try to exploit migrant flows to smuggle operatives from Libya to Europe like the Islamic State did from Syria through Turkey for the Paris and Brussels attacks. Migrant flows to Europe from Libya remain high. Between August 1, and December 1, 2017, over 21,000 migrants arrived in Italy by sea from North Africa.41

It should also be noted that the Islamic State has experienced serious setbacks in Libya, which may constrain the group’s ability to recruit, train, and dispatch terrorists for international operations, as well as the group’s ability to communicate with and guide operatives overseas. The group’s 2015 takeover of Sirte, with hindsight, represented the high-water mark of its expansion in Libya.c Since 2015, the Islamic State has been forced out of Derna, Benghazi, Sirte, and Sabratha.42 Under the Obama administration, the U.S. military carried out airstrikes against Islamic State militants, including several training camps near Sabratha, Sirte, and other areas of Libya.43 U.S. pressure has continued under the Trump administration. In February 2017, Noureddine Chouchane was “likely” killed in a U.S. airstrike in the vicinity of Sabratha.44 In September 2017, the United States launched airstrikes against an Islamic State desert camp 150 miles southeast of Sirte.45 These operations appear to have pushed Islamic State operatives deeper into Libya’s southern interior.46

However, given that there is no end in sight to the political turmoil in Libya, the continued presence of external plotters in Libya with networks of contacts in Tunisia and Europe, the Libya-Tunisia-European attack networks are likely to pose a threat for some time to come. CTC

Johannes Saal is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Lucerne. He primarily researches jihadi networks in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Follow @johannes_saal

Substantive Notes

[a] A 2016 study by the Tunisian Center for Research and Studies on Terrorism examined the records of over 1,000 incarcerated jihadis involved in court cases between 2011 and 2015 and found that 69 percent of the sample underwent military training in Libya. Eighty percent of these trainees traveled to Syria afterward. Ahmed Nadhif, “New Study Explores Tunisia’s Jihadi Movement in Numbers,” Al-Monitor, November 8, 2016.

[b] The brigade was initially considered to be nationalist. However, soon after it liberated Tripoli from the Qaddafi regime, al-Harati and other Western brigade leaders met with Abdelhakim Belhadj, a former LIFG emir, and made him chief of the Tripoli Military Council. Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Abdelhakim Belhadj and Ansar Al-Sharia in Tunisia,” Foundation for Defense of Democracy, October 8, 2013; Matthieu Mabin, “The Tripoli Brigade,” France 24, September 1, 2011.

[c] By 2016, the Islamic State’s limited capacity to capture and hold territory in Libya had become clear. See Geoff Porter, “How Realistic is Libya as an Islamic State ‘Fallback’?” CTC Sentinel 9:3 (2016).

Citations

[1] Rukmini Callimachi and Eric Schmitt, “Manchester Bomber Met with ISIS Unit in Libya, Officials Say,” New York Times, June 3, 2017; Georg Heil, “The Berlin Attack and the ‘Abu Walaa’ Islamic State Recruitment Network,” CTC Sentinel 10:2 (2017); Florian Flade, “IS-Kontakte in Libyen: Was das LKA bei Amris Terror-Chat mitlas,” Die Welt, March 27, 2017.

[2] Richard Barrett, “Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees,” The Soufan Center, October 2017; Reid Standish, “Shadow Boxing With the Islamic State in Central Asia,” Foreign Policy, February 6, 2015.

[3] Haim Malka and Margo Balboni, “Tunisia: Radicalism Abroad and at Home,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2016.

[4] Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Dan Lamothe, “The U.S. flew stealth bombers across the globe to strike ISIS camps in Libya,“ Washington Post, January 19, 2017.

[5] Chris Stephen, “Tunisia gunman trained in Libya at same time as Bardo museum attackers,” Guardian, June 30, 2015.

[6] Aidan Lewis and Ahmed Elumami, “U.N. assisting thousands of migrants in Libyan smuggling hub,” Reuters, October 9, 2017.

[7] Carly Lovett, “Tunisia attack: The British victims,“ BBC News, February 29, 2016.

[8] Stephen.

[9] “Tunisia Beach Attack: ‘Mastermind’ Named,” BBC News, January 9, 2017.

[10] Marta Serafini, “Il Regista Del Video Di Isis Su Bruxelles Scarcerato dall’Italia Nel 2012,” Corriere della Sera, March 31, 2016; Andrea Galli, “Arrestato il tunisino Fezzani, leader di Isis reclutatore in Italia,” Corriere della Sera, November 14, 2016; Alessandro Bartolini, “Reclutatori Isis, Combattenti E Aspiranti Kamikaze: Il Grande Romanzo Nero Del Jihad È in Lombardia,” Fatto Quotidiano, January 4, 2017.

[11] Ajnadin Mustafa, “Top Tunisian terrorist reported captured by Zintanis,” Libya Herald, August 17, 2016.

[12] Jim Miklaszewski, Ram Baghdadi, Abigail Williams, Courtney Kube, Sarah Burke, and Alastair Jamieson, “U.S. Fighter Jets Target ISIS in Libya’s Sabratha; Dozens Killed,” NBC News, February 20, 2016.

[13] Fausto Biloslavo, “La Carriera Di Chouchane: Prima Al Qaida, Poi Da Noi,” Giornale, September 3, 2016.

[14] Pieter Van Ostaeyen, “Belgian Radical Networks and the Road to the Brussels Attacks,” CTC Sentinel 9:6 (2016).

[15] Pieter Van Ostaeyen, “Katibat Al-Battar and the Belgian Fighters in Syria,” pietervanostaeyen.com, January 21, 2015; Van Ostaeyen, “Belgian Radical Networks and the Road to the Brussels Attacks.”

[16] Guy Van Vlierden, “Terror Chief Who Commanded Abaaoud Also Came from Molenbeek,” Emmejihad, January 18, 2017.

[17] Cameron Colquhoun, “Tip of the Spear? Meet ISIS’ Special Operations Unit, Katibat Al-Battar,” Bellingcat, February 16, 2016; Jean-Charles Brisard and Kévin Jackson, “The Islamic State’s External Operations and the French-Belgian Nexus,” CTC Sentinel 9:11 (2016).

[18] Josie Ensor, “Manchester Bomber’s Brother Was ‘Plotting Attack on UN Envoy in Libya,’” Telegraph, May 27, 2017; “Manchester bomber’s brother and father arrested in Tripoli,” Libya Herald, May 24, 2017; Laura Smith-Spark and Hala Gorani, “Manchester suicide bomber spoke with brother 15 minutes before attack,” CNN, May 26, 2017.

[19] Callimachi and Schmitt.

[20] Hani Amara and Ahmed Elumami, “Manchester bomber’s father says he did not expect attack,” Reuters, May 24, 2017; Maggie Michael, “Father and brother of alleged bomber detained in Libya,” Associated Press, May 24, 2017.

[21] Katrin Bennhold, Stephen Castle, and Declan Walsh, “‘Forgive Me’: Manchester Bomber’s Tangled Path of Conflict and Rebellion,” New York Times, May 27, 2017.

[22] Stewart Bell, “Manchester Bombing Suspect Salman Abedi Reportedly Linked to Former Ottawa Extremist Imam,” National Post, May 25, 2017; Katrin Bennhold, Stephen Castle, and Suliman Ali Zway, “Hunt for the Manchester Bomber Accomplices Extends to Libya,” New York Times, May 24, 2017.

[23] “Tripoli Imam Arrested, Accused of Promoting Terrorism,” Libya Herald, November 9, 2017.

[24] “Imam Accused of Terrorist Links Released by Rada,” Libya Herald, December 4, 2017.

[25] Josh Halliday, “Jihadist with links to Manchester bomber is guilty of fighting for Isis,” Guardian, December 7, 2017.

[26] Heil.

[27] Flade.

[28] Paul Cruickshank and Nic Robertson, “US Bombing in Libya Was Linked to Berlin Truck Attack,” CNN, January 24, 2017.

[29] For a detailed account on Amri’s German network, see Heil.

[30] Katharina Iskandar, “Im Gebetshaus des Drahtziehers,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, February 1, 2017; Nicolas Barotte, “Un terroriste tunisien arrêté en Allemagne,” Figaro, February 1, 2017.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Marco Menduni, “I Killer Di Berlino E Marsiglia Sono Passati Da Aprilia,” Stampa, October 3, 2017.

[33] Evan Kohlmann, Al-Qaida’s Jihad in Europe: The Afghan-Bosnian Network (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2004); Lorenzo Vidino, Al Qaeda in Europe: The New Battleground of International Jihad (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2006).

[34] Serafini; “Top ISIS Recruiter in Italy Arrested,” ANSA, November 14, 2016.

[35] Galli; Mustafa.

[36] Nadia Francalacci, “Isis: Arrestato Moez Fezzani, Il Reclutatore Di Jihadisti Italiani,” Panorama, November 14, 2016.

[37] “Bardo museum attack suspect extradited to Tunisia,” AFP, December 23, 2016.

[38] Lorenzo Cremonesi, “Uomini ISIS Nel Milanese,” Corriere della Sera, August 13, 2014; Cesare Giuzzi, “ISIS, caccia alla rete di Milano,” Corriere della Sera, August 14, 2016; “Libya Warns Italy about an Islamic State Cell in Milan,” International Business Times, August 14, 2016.

[39] Sandro De Riccardis, “Strage Al Bardo, I Giudici Scarcerano Touil Ma La Questura Lo Espelle. I pm: ‘Accuse Da Archiviare,’” Repubblica, October 28, 2015.

[40] Stefan Heissner, Peter R. Neumann, John Holland-McCowan, and Rajan Basra, “Caliphate in Decline: An Estimate of Islamic State’s Financial Fortunes,” International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, February 2017.

[41] “Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals Reach 164,654 in 2017; Deaths Reach 3,038,” International Organization for Migration, December 1, 2017.

[42] Geoff Porter, “How Realistic is Libya as an Islamic State Fallback,” CTC Sentinel 9:3 (2016); Patrick Wintour, Libyan forces claim to have ousted Isis from final stronghold,” Guardian, June 9, 2016.

[43] “Islamic State camp in Libya attacked by US planes,” BBC News, February 19, 2017,

[44 Miklaszewski, Baghdadi, Williams, Kube, Burke, and Jamieson.

[45] Ryan Browne, “US strikes Libya for first time under Trump,” CNN, September 24, 2017.

[46] Andrew McGregor, “Europe’s True Southern Frontier: The General, the Jihadis, and the High-Stakes Contest for Libya’s Fezzan Region,” CTC Sentinel 10:10 (2017).

Skip to content

Skip to content