Abstract: Drawing in part on internal Islamic State documents, this article aims to provide a new and more nuanced understanding of how the Islamic State has dealt with Kurds. Though the Islamic State is often characterized as being inherently anti-Kurdish, the organization has recruited Kurds and directed messaging toward Kurdish audiences. At the same time, internal documents in particular show the tensions between realities on the ground for Kurdish communities that lived under Islamic State control and the organization’s ideology that is, in theory, blind to ethnicity.

The controversy over how the Islamic State has treated Kurds is often colored with sensationalist language, with the suggestion that the Islamic State, an entity whose ranks consist primarily of Sunni Arabs, maltreats Kurds simply on the basis of their ethnicity. This narrative stems partly from conflating Kurdish experiences with the Islamic State with the organization’s genocide against the Yazidi religious minority in Iraq, which does not necessarily identify as ethnically Kurdish but speaks the Kurdish language. For example, one article in The National Interest claims that with the rise of the Islamic State, “the Kurds also began to make headlines, first as the victims of the barbaric hordes of the self-proclaimed caliphate, then as its most capable and willing adversaries.”1 Similarly, an October 2014 article in Financial Times spoke of the Islamic State’s “targeting of the Kurds.”2 Ranj Alaaldin, in an opinion piece for The Guardian, goes even further in generalization, asserting that “jihadi groups such as ISIS view Kurds … and other minorities as heretics.”3

The immediate counterpoint to these claims of Islamic State persecution of Kurds merely for being Kurds is that such behavior conflicts with the organization’s ideology. While the Islamic State’s main means of functioning and communicating is the Arabic language, the Islamic State’s worldview is, in theory, based on the dichotomy of Muslims and non-Muslims. Thus, when it comes to those identified as Muslim, their ethnicity should not matter. This line of thought has been expressed with consistency. For instance, in a speech announcing the establishment of the caliphate, the organization’s then spokesman, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, drew attention to the precedent of the acceptance of Islam by the Arabs that supposedly resulted in eliminating distinctions based on ethnicity. “By God’s blessing, they became brothers … and they united in faith … not distinguishing between non-Arab and Arab, or between eastern and western, or between white and black.”4

This article seeks to provide a more nuanced understanding between the narrative of Islamic State persecution of Kurds simply for being Kurdish and the theoretical ideal of no discrimination among Muslims on the basis of ethnicity. This subject will be explored primarily through internal Islamic State documents, though some of the organization’s external propaganda will be taken into account as well. As part of the investigation, this article will particularly focus on Islamic State recruitment of Kurds and the policies toward Kurdish communities and Kurds living in its areas.

Islamic State Recruitment of Kurds

The presence of Kurds in jihadi groups is by no means a new phenomenon. Most notably, prior to 2003, the history and background of the jihadi group Ansar al-Islam (Partisans of Islam), which was led by Mullah Krekar, illustrate Kurdish involvement in salafi and jihadi trends in the Iraqi Kurdistan area for decades.5 Beyond Iraqi Kurdistan, Brian Fishman has highlighted the case of Abu al-Hadi al-Iraqi, a Kurd from Mosul who was a veteran of the Iran-Iraq War.6 Abu al-Hadi al-Iraqi migrated to the Afghanistan-Pakistan area and became a leading figure in al-Qa`ida by the end of the 1990s. Among the training camps for residents of the al-Qa`ida guesthouse run by Abu al-Hadi al-Iraqi was a ‘Kurds Camp,’ which, as its name suggests, was intended to train Kurdish jihadi operatives.7

Given these precedents, it should not be surprising that the Islamic State would recruit Kurds who are ideologically committed to its cause. In this regard, there have been multiple propaganda items from the Islamic State featuring Kurds in the organization’s ranks. Prior to the caliphate announcement, one such item was the 26th video in the series “A Window Upon the Land of Epic Battles,” released in November 2013 by what was then the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham’s al-Itisam media. The video, entitled “A Message to the Kurds and a Martyrdom Operation,” features a Kurdish speaker threatening the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq, vowing that “by God’s permission, we will return to Kurdistan with the arms we have placed on our shoulders.”8 The speaker continues, “By God’s permission we will defeat you just as we have defeated the apostates of the PKK and the shabiha of Bashar…despite the force of their arms and their large numbers.”9 The speaker is thus making a clear distinction between fighting Kurds merely for being Kurdish and fighting Kurdish political entities that are deemed apostate (i.e., Muslim by origin but having left the fold of Islam) for espousing a heretical, nationalistic outlook.

After the declaration of the caliphate, propaganda appeals to Kurds emerged in productions such as “The Kurds – Between Monotheism and Atheism” from the Raqqa province media office. The video, which has Kurdish subtitles where necessary, features Kurdish fighters for the Islamic State while highlighting a contrast between Kurdish forbears portrayed as having performed great services for the Islamic cause—such as Salah al-Din, who fought the Crusaders and brought about the end of the Shi’i Fatimid Caliphate—and modern-day Kurdish nationalist causes, such as Mustafa Barzani and the Kurdistan Democratic Party, portrayed as allies of Israel.10

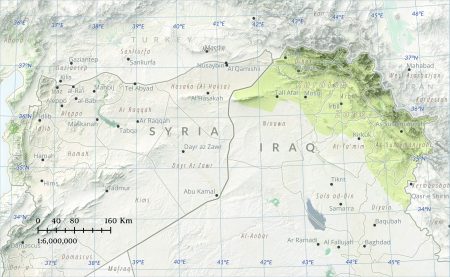

Syria and Northern Iraq (Rowan Technology) (Editor’s note: The part of the map shaded in green shows the approximate geographic area of Iraq in which there are significant populations of Kurds. These include Kurdish majority areas and areas in which there is a mix between Kurds and Arabs and other ethnicities. It does not denote the borders of the Iraqi region of Kurdistan. Several areas in the shaded area, including Mosul, have majority Arab populations and a significant number of Kurds live outside the shaded area.)

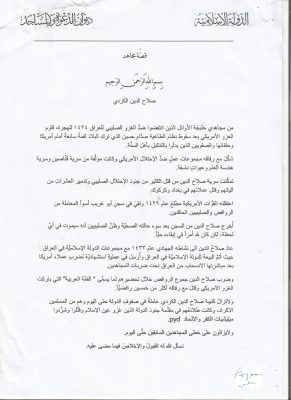

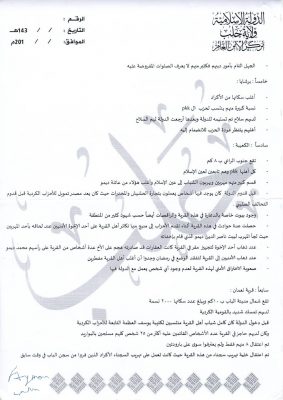

An item from the internal propaganda series Qisas al-Mujahideena and some external media reporting point to the existence of a Kurdish-speaking unit within the Islamic State’s fighting forces known as the Salah al-Din Battalion.11 According to Qisas al-Mujahideen,12 the battalion takes its name from a certain Salah al-Din al-Kurdi, who was originally from Halabja and took up arms against the U.S. occupation, forming his own contingents of operatives. Arrested by U.S. forces in 2008, he supposedly spent time in Abu Ghraib prison, but was then released on grounds of ill health. By late 2011 or early 2012, Salah al-Din al-Kurdi had returned to jihadi activity, joining the Islamic State of Iraq and then sent to conduct a suicide operation in the run-up to the Arab League Summit in Baghdad at the end of March 2012. (See Exhibit 1.)

Finally, there is evidence of significant Islamic State recruitment in Turkey among the Kurdish minority. As Metin Gurcan notes, the recruitment “reflects the fact that many Kurds live in southeast Turkey, the most religious part of the country.”13 Many of these Kurdish jihadis, coming from a historically marginalized minority in Turkey, appear to believe that the Islamic State would grant them equal rights.14

Thus, so far as recruitment is concerned, the evidence is clear that the Islamic State willingly accepts fighters and members of Kurdish origin. The criterion of acceptance that matters here is the ideological commitment to the Islamic State.

Kurdish Communities Living under the Islamic State

While the Islamic State has no problem in recruiting Kurds willing to serve and fight for the organization, most people in the various cities, towns, and villages that have fallen under Islamic State control do not become members of the Islamic State. Rather, they remain as civilians. Many of these civilians might have ended up working in various administrative offices and aspects of governance co-opted by the Islamic State (e.g., teachers in schools), but that does not mean that they became members of the Islamic State.

Kurdish communities and populations are known to have existed in many areas that were seized by the Islamic State, including villages in north and east Aleppo countryside, the cities of Raqqa and Tabqa along the Euphrates in central northern Syria, and the city of Mosul. According to Islamic State maxims, the theory is that the group should deal with these Kurdish communities solely on the basis of their religion. If they are Muslims who outwardly follow the rules and rituals of Islam, then there is no reason to treat them any differently than Sunni Arabs abiding by the dictates of the religion and living under Islamic State control. The principle is well illustrated in a statement distributed by the Islamic State’s Ninawa province media office in Mosul in late July 2014, denying the rumors of forcible displacement of Kurds from the province. The statement affirms, “The Sunni Kurds are our brothers in God. What is for them is for us, and what is upon them is upon us. And we will not allow any one of them to be harmed so long as they remain on the principle of Islam.”15 In practice, however, the widespread suspicions and associations of Kurdish communities with Kurdish nationalist parties have led to discriminatory treatment in many areas under Islamic State control.

The evidence for discriminatory treatment of Kurdish communities primarily comes from internal documents from Syria. Close cooperation between the U.S.-led coalition and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which includes the Syrian offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—the Democratic Union Party and its armed wing the Popular Protection Units (YPG)—has been vital in pushing back the Islamic State in the north and northeast of the country. In June 2015, the Islamic State issued a notification in Raqqa province requiring Kurdish inhabitants to leave for the Palmyra area in Homs province.16 The decision was justified on the grounds of the “alliance of the Kurdish parties” with the U.S.-led coalition and that there were some among the Kurdish inhabitants under the Islamic State who had “cooperated with the Crusader alliance.” Thus, on the grounds of alleviating tension, the stipulation to leave Raqqa province was imposed. At the same time, the Islamic State was careful to emphasize that the properties of those Kurds required to leave but considered to be Muslims would not be confiscated, and the group made arrangements for their property to be registered with the real estate bureaucracy. A subsequent statement was issued by the emir of Raqqa city, warning Islamic State fighters that they could not infringe on those properties.17 This prohibition was reaffirmed the following month,18 suggesting that violations had taken place. It is not clear, in the end, how far these stipulations against seizing Kurdish properties were enforced.

The documentary evidence suggests that not all Kurds who were living in Raqqa province under the Islamic State ultimately left these areas. It appears that it subsequently became possible to obtain an exception to the requirement to leave. From the Raqqa province city of Tabqa, a document dated December 2015 emerged from the ruins of the aftermath of the Islamic State’s defeat there by the U.S.-backed SDF. The document noted that those Kurds who still wished to reside in Raqqa province had to go to the office of Kurdish affairs.19 Many Kurds, of course, would have fled Islamic State territory entirely, and the Delegated Committee (a general governing body for the Islamic State) issued a directive in mid-August/mid-September 2015 requiring confiscation of property of Kurds who fled to “the land of kufr” (land governed by those deemed to be non-Muslims).20 It should be noted, however, that confiscation of property of those who fled the Islamic State was not unique to the Kurds and other ethnic minorities. A similar fate befell the properties of medical professionals who fled the Islamic State,21 as well as those accused of working with other factions opposed to the Islamic State like the Free Syrian Army.

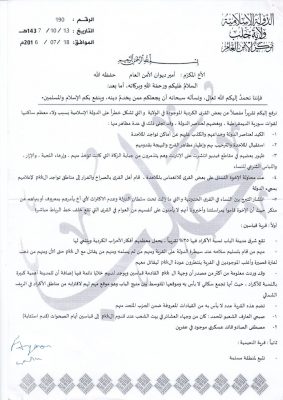

The suspicion of Kurdish communities in Syria was not limited to Raqqa province. In Aleppo province, a number of villages with Kurdish communities came under the control of the Islamic State. Internal documents obtained by this author reveal a security report issued by the al-Bab office of the public security department in July 2016 and addressed to the higher public security ministry.b (See Exhibit 2.) The report gives a detailed description of “some of the Kurdish villages in the province that represent a danger to the Islamic State because of the loyalty of the majority of their inhabitants to the Syrian Democratic Forces, and their hatred of members of the Dawla [Islamic State].” Among the charges leveled in the al-Bab report are that the Kurdish communities have been deceiving members of the Islamic State about “places of the presence of the atheists” (referring to the Syrian Democratic Forces); “receiving and welcoming the atheists;” videos disseminated on the Internet featuring complaints about impositions of Islamic norms such as payment of zakat taxation and the dress code for women; and informing Kurdish forces in advance of Islamic State raids into their territory. For context, the reference to welcoming the SDF and the displays of rejecting “Islamic” morality are amply attested in reports at the time of the sense of liberation felt by many locals (not necessarily just Kurds) as the Syrian Democratic Forces were capturing the Manbij area in east Aleppo countryside from the Islamic State.22

The al-Bab report proceeds to give some specific cases, such as the village of Qibat al-Shih to the north of al-Bab town. According to the report, 99% of the village is Kurdish, with 70% having been with “the atheist party” (presumably referring to the Democratic Union Party/PKK). The Islamic State, the report claims, “killed many of the sons of this village for their loyalty to their Kurdish nationalism, as in the battle of Ayn al-Islam [Kobani], they were going to Turkey and from there to Ayn al-Islam to fight with the PKK.” In another case, about a village called Haymar Labadah on the route between Manbij and al-Khafsa with a population of 5,000, the report claims that “the majority of them are from those who hate the Islamic State.” More specifically, the report alleges, for example, that by night the people of the village attacked the Hisba [Islamic morality enforcement] base in the village 10 days after it had been opened, stealing 50,000 Syrian pounds ($90-100), a laptop, and some confiscated cigarettes. Moreover, the report says that there are people from the village who have been participating in the SDF campaign to capture Manbij.

On the basis of the various cases presented, the report concludes with the suggestion to “displace the people of these villages in the present time to avoid the cases of treachery that happened in the similar villages that have now fallen under the control of the PKK.”

Conclusion

Despite the recommendations of the security report, it is not clear whether the suggested policy of displacement was actually implemented, as opposed to the documents from Raqqa province where the evidence of implementation of forced displacement is unambiguous. At least some Kurdish communities continue to reside in areas of north Aleppo countryside retaken from the Islamic State by Turkish-backed Syrian rebels.23 However, the fact that recommendations for displacement were put forward at all, taken in combination with the displacement that took place in Raqqa province, illustrates that Islamic State policies toward many Kurdish communities in areas under its control were tainted with suspicion and hostility. As one anti-PKK Kurdish activist currently based in the north Aleppo countryside area of Akhtarin explained to this author, more fieldwork will be required to track specific village and town cases of displacement, but in the general sense, the “proportion of [Islamic State] oppression on the Kurds was more” than that on the Sunni Arab communities.24

From a counterterrorism perspective, highlighting the internal documentary evidence of Islamic State suspicion and hostility toward many Kurdish communities, despite the theoretical ideal of only discriminating among people on the basis of their religion, may be worthwhile in an attempt to split Kurdish fighters from the ranks of the Islamic State, who may have joined the group believing that the Islamic State treats Kurdish Muslims fairly. CTC

Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi is the Jihad-Intel Research Fellow at the Middle East Forum, a U.S.-based think-tank, and an associate fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence at King’s College, London. He has testified on the Islamic State before British parliamentary committees. Follow @ajaltamimi

Appendix: Previously Unpublished Internal Documents Referenced in This Article

Exhibit 1: Biography of Salah al-Din al-Kurdi from the series Qisas al-Mujahideen

Exhibit 2: Security report on Kurdish communities issued by the al-Bab office of the public security department, July 2016

Exhibit 2 (cont.): Security report on Kurdish communities issued by the al-Bab office of the public security department, July 2016

Exhibit 2 (cont.): Security report on Kurdish communities issued by the al-Bab office of the public security department, July 2016

Exhibit 2 (cont.): Security report on Kurdish communities issued by the al-Bab office of the public security department, July 2016

Substantive Notes

[a] As a source for information, the series needs to be treated with a degree of caution. The stories related are designed to boost the morale of Islamic State fighters, and as such they are open to considerable embellishment and perhaps even total fabrication.

[b] These documents were obtained through an intermediary via the Syrian rebel group Ahrar al-Sharqiya, which is based in the north Aleppo countryside. Its members, who originate in the eastern Deir ez-Zor province, participated in battles against the Islamic State in Aleppo province and have taken Islamic State members as prisoners. In addition, they continue to maintain connections with contacts in eastern Syria and thus, have multiple avenues for obtaining Islamic State documents. The study obtained reflects a typical function of the Islamic State’s security department in the provinces—that is, to investigate anything that may be considered a security threat to the Islamic State.

Citations

[1] Burak Kadercan, “This is what ISIS’ Rise Means for the ‘Kurdish Question,’” National Interest, September 9, 2015.

[2] Thomas Hale, “A short history of the Kurds,” Financial Times, October 17, 2014.

[3] Ranj Alaaldin, “The ISIS campaign against Iraq’s Shia Muslims is not politics. It’s genocide,” Guardian, January 5, 2017.

[4] Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, “This is the promise of God,” Al-Furqan Media, June 29, 2014.

[5] Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “A Complete History of Jama’at Ansar al-Islam,” aymennjawad.org, December 15, 2015.

[6] Brian Fishman, “The Man Who Could Have Stopped The Islamic State,” Foreign Policy, November 23, 2016.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Al-Itisam Media presents a new video message from the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham: ‘A Window Upon the Land of Epic Battles #26,’” Jihadology, November 15, 2013.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “New video message from the Islamic State: ‘The Kurds: Between Monotheism and Atheism, Wilayat al-Raqqah,’” Jihadology, August 2, 2016.

[11] For example, “Who is leading the Da’esh forces on the right side in Mosul…and why?” Qoraish, January 19, 2017.

[12] Story of Salah al-Din al-Kurdi, Qisas al-Mujahideen (see Exhibit 1). This was obtained by the author (via an intermediary) from an individual who worked in the Islamic State administration in Manbij and left for the Azaz area in the north Aleppo countryside.

[13] Metin Guran, “The Ankara Bombings and the Islamic State’s Turkey Strategy,” CTC Sentinel 8:10 (2015).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Specimen 8Y in Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents,” aymennjawad.org, January 27, 2015. This archive of Islamic State administrative documents is housed on the author’s website and reflects an ongoing project that began in January 2015 to collect and translate Islamic State documents, which total more than 1,000 in number. This archive includes gathering of documents available in the open-source realm and documents collected privately from contacts, with determinations made as to their authenticity based on a number of criteria (e.g., use of stamps, absence of red flag motifs. etc.).

[16] Specimen 5M in “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents.”

[17] Specimen 6B in “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents.”

[18] Specimen 9Z in “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents.”

[19] Specimen 37R in Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents (continued … again),” aymennjawad.org, September 17, 2016.

[20] Specimen 25J in “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents (continued … again).”

[21] Specimen 5I in “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents.”

[22] For example, Wladimir Van Wilgenburg, “Syrian Arabs around Manbij overjoyed IS vanquished, welcome SDF, Kurds,” Middle East Eye, June 12, 2016.

[23] Aymenn al-Tamimi, “#Syria: Shami Front and Ahrar al-Sham visit Kurdish village of Susenbat in north Aleppo countryside: outreach to Kurdish tribal figures,” Twitter, May 1, 2017.

[24] Author interview, Ahmad Masto, anti-PKK Kurdish activist in Syria, September 2017.

Skip to content

Skip to content