Abstract: A fragile U.N.-brokered ceasefire between the Houthis and their military opponents in Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) held from April to October 2022 but has now lapsed. The Houthis hold the key to an enduring ceasefire in Yemen, and can threaten the stability of Red Sea shipping lanes and the security of the United States and its partners in the Middle East. All these considerations necessitate a fuller understanding of the Houthi political-military leadership, its core motivations, and the nature and extent of Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah influence within the movement. This study argues that the Houthi movement is now more centralized and cohesive than ever, in part due to close mentoring from Lebanese Hezbollah and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The Houthi Jihad Council is emerging as a remarkable partner for Iran, and the Houthi-Iran relationship should no longer be viewed as a relationship of necessity, but rather a strong, deep-rooted alliance that is underpinned by tight ideological affinity and geopolitical alignment. The emergence of a ‘southern Hezbollah’ is arguably now a fact on the ground.

In September 2018, one of the authors of this article published an analysis of the military evolution of the Houthi movementa in CTC Sentinel, noting the group’s very rapid five-year development from an insurgent group fielding roadside bombs to a state-level actor using medium-range ballistic missiles.1 Since then, the Houthis have further consolidated their hold over the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, and the Red Sea coast port city of Hodeida, and nearly won the civil war with a sustained (but ultimately indecisive) military offensive against Yemen’s oil and gas hub at Ma’rib.2 On January 19, 2021, the outgoing Trump administration designated the Houthi organizational institution Ansar Allah as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO), a step that the Biden administration almost immediately revoked on February 16, 2021.3 Some Houthi leaders remained covered by older sanctions4 b (and additional Houthi military leaders continue to be added to U.S. sanctions lists) for posing a “threat to the peace, security, or stability of Yemen.”5

A fragile U.N.-brokered ceasefire between the Houthis and their military opponents in Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council (PLC)6 held from April to October 2022 but has (at the time of writing) lapsed,7 c and the path to long-term conflict resolution remains unclear. As a rebel force now in control of much of the Yemeni state, the Houthis will likely be required to give up some of their gains in return for an enduring peace, and such a peace may not be welcomed by the Houthis’ strongest backers in the war—namely Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah.d The Houthis continue to pose a military and counterterrorism threat to the United States and its partners in the region,e as well as a menace to global commerce in the Red Sea.f All these considerations necessitate a fuller understanding of the Houthi political-military leadership, its core motivations, and the nature and extent of Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah influence within the movement.

In this new article, an enlarged and strengthened team with extensive on-the-ground access in Houthi-held areasg will look in-depth at the structure and composition of Houthi military leadership. An excellent anthropological and socio-political literature already exists on the Houthis thanks to ground-breaking studies by RAND8 and the writings of academics such as Marieke Brandt.9 This article builds on this literature by updating the RAND study and focusing more attention on military aspects and on the proven roles of Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah in Houthi military affairs. In the opening section, the article reviews the genealogical, social, political-religious, and environmental (i.e., wartime) drivers for the emergence of the current generation of Houthi military and security leaders. It next examines command politics under the Houthis’ current leader Abdalmalik al-Huthi. It then looks in-depth at the Jihad Council established by the Houthis to centralize military and security decision-making using a mechanism adapted from Lebanese Hezbollah. Then the article looks at the role within the Houthi Jihad Council of the IRGC Jihad Assistant and his Lebanese Hezbollah Deputy. The next section explores the Houthi administrative takeover of Yemen’s military institutions and the gradual mobilization and indoctrination of a new generation of active service soldiers and reserves. In the penultimate part, the article looks at how the Houthis employ armed forces and which commanders have operational control of key geographic commands and praetorian or specialized forces. The article concludes with analytic findings concerning which segments of the Houthi war machine might support conflict termination and which elements are most likely to continue to threaten the peace, security, or stability of Yemen.

Generational Change in the Houthi Leadership

The composition of the Houthi movement has changed throughout its lifespan, demonstrating (in the view of the authors) both a remarkable openness to an ever-broadening general membership but also, under the surface, an obdurate refusal to share real power beyond a small set of male antecedents related to religious scholar Badr al-Din al-Huthi, a sadah10 (descendant of the Prophet) and influential Zaydih preacher until his death (by natural causes) in 2010.11 Of critical importance, Badr al-Din and his sons were members of the minority Jarudi sect of Zaydism,i the denomination of Zaydism closest to Shi`a Islam in political theology.j

Badr al-Din was thus the root of today’s Houthi movement, which is still dominated by his sons and other male relatives.12 The four marriages of Badr al-Din13 created the foundation of the Houthi movement in the Sa`ada province of northern Yemen. Badr al-Din had 13 sons who reached maturity.14 Of these 13, most married at least once. This created a baseline force consisting of circles of tribal protection for Badr al-Din and his sons. As noted by Marieke Brandt, the preeminent anthropologist of the Houthi area, the Khawlan tribal confederation of northern Yemen was “the first incubator of the Houthi movement.”15

Husayn Badr al-Din al-Huthi built upon this base to form the first generation of the Houthi paramilitary movement in the 1980s and 1990s.16 He had his father’s gift for oratory and religious studies, and he was highly political.k Born in either 1956 or 1959, Husayn was a young and politically receptive twenty-something when the Islamic Revolution unfolded in Iran. Far from reluctant or recent partners of Iran, Badr al-Din and Husayn’s family enthusiastically embraced Khomeinism and the example of the Islamic Revolution.l As Morteza Mohatwari, a senior Zaydi cleric, said in 2010, for Zaydis of Husayn’s generation the Iranian regime’s version of Twelver Shiism is the true Zaydism because it mobilizes the masses to confront foreign powers and unjust rulers.m His father Badr al-Din visited Iran (and Beirut) for intermittent stays between 1979 and Badr al-Din’s death in 2010,17 usually taking Husayn and later some of his other sons with him, notably his fifth son, Mohammed (born around 1965),18 and his ninth son, Abdalmalik (born around 1979),n both of whom were avid religious students produced by Badr al-Din’s unions with sadah families.o

By the early 1990s, Husayn had two main political influences: Iran’s first Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and Usama bin Ladin, both of whose speeches he followed with particular fascination due to their willingness to stand up to Israel and to American “arrogance.”p In 1994, Badr al-Din and Husayn began sending 40 religious students a year to Qomq—a flow that would eventually produce around 800 Qom-trained students,r some of whom are reported to have been groomed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) with paramilitary training.19 In 1999-2000, Husayn Badr al-Din spent a year undertaking religious studies in Khartoum20 at a time when Sudan was the most active IRGC and Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) outstation on the Red Sea.21 Husayn then went from Sudan to Iran, and when he returned from this retreat, he introduced the now infamous slogan that supercharged the Houthi movement, “the scream” (al-shi‘ar): “Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse upon the Jews, Victory to Islam.”22

Scholars disagree on the fundamental drivers of Husayn’s political ambitions: One theory is that Badr al-Din and Husayn were primarily pursuing a so-called hadawi23 agenda, a doctrine that held sadah (collectively the Ahl al-Bayt, the descendants of the Prophet) to be superior to other Yemenis and the only caste fit for leadership.24 In the hadawi theory, Badr al-Din and Husayn sought a return of some form of imamate or other system of governance under sadah leadership (which had been the long preeminent form of government in parts of northern Yemen from around 897 AD until 1962 AD).25 Others see a combination of social mobility and dynastic agendas,26 with Badr al-Din and Husayn outmaneuvering longer-established and richer Zaydi sadah families through the dynamic use of a Lebanese Hezbollah-type Zaydi-Shi`a revivalist movement (called “Believing/Faithful Youth” (Muntada al-Shahabal-Mu’min)) that employed summer camps, social programs, and a political party.27 Still others assess that Badr al-Din and Husayn were surreptitiously introducing Jarudi Zaydism and related Iranian Twelver aspects to the broader Zaydi practice of Islam28 s—what Oved Lobel characterized as “a neo-Twelver core carved out of the Zaydi revival.”29 All, some, or none of these motives for Badr al-Din and Husayn’s activism may have been operative at the same time, but what the authors of this study assess can be said with a higher degree of certainty is that Husayn and his father were intent on breaking the mold of northern Yemeni political Islam and that they looked to the Islamic Revolution in Iran and to Lebanese Hezbollah for inspiration, ideas, and support.t

All of the above factors shaped the composition of the Houthi leadership that emerged under Husayn and entered the first of the six wars that raged between the Yemeni government and the Houthi movement in 2004-2010.30 Husayn now commanded a sizable cohort of Khawlan bir Amir confederation tribesmen, including hundreds of religious students sent to Qom seminaries and well over 10,000 young men sent through Believing Youth summer camps and social or educational programs under his stewardship inside Yemen.31 u This initial Houthi cadre demonstrated some of the enduring characteristics of Houthi command and control.

First, in the authors’ assessment, the movement preferred the membership of fighters who were with Husayn since the start of the six wars in 2004. In the authors’ view, this cadre had advantages over all later joiners due to the longevity of their loyalty and their war service.32 Examples of these elevated early joiners include key sadah military commanders Yusuf al-Madani (who married a daughter of Husayn)v and Abdullah Yahya al-Hakim (Abu Ali),w who Houthi movement historiographer Marieke Brandt characterized as Abdalmalik’s military second-in-command in the years leading up to the Houthi takeover of the government in 2014. Non-sadah leaders of this status were rare, the exception being Husayn’s closest friend and ally prior to Husayn’s death in 2004, Abdullah Eida al-Razzami, a qabili politician of similar age who served as his right-hand man in the first Houthi-government war in 2004.33

In the authors’ assessment, the struggle to replace Husayn as the Houthi leader in 2005 spotlighted the second key characteristic of Houthi command and control arrangements—that is, Badr al-Din’s strong preference for sadah leadership drawn only from the ranks of his relatives.x As noted, northern Yemen has a deep-seated caste system, topped by the sadah, following by other castes—the tribal sheikhs and administrators (qadi), and the “third type” (ahl al-thuluth), such as artisans, shopkeepers, restaurateurs, and merchants.34 When Husayn was killed by the Yemeni government in 2004, Badr al-Din moved swiftly to personally hold the leadership of the Houthi movement35 in order to prevent leadership from passing outside his family, even to a longstanding qabili loyalist such as Abdullah Eida al-Razzami or a sadah in-law such as Yusuf al-Madani.36

The selection of Abdalmalik, then a young man in his early twenties, as the supreme military commander of the wartime Houthi movement shines light on a third trend in Houthi command and control—that is, the dominance of leaders with a special connection to Iran and Hezbollah. Setting aside the imprisoned Mohammedy and the exiled Yahya,37 Badr al-Din bypassed five eligible sons older than Abdalmalik when Husayn died: Abdalqader, Ahmad, Hamid, Amir al-Din, and Ibrahim.38 Indeed, in the authors’ reading of events, Badr al-Din did not hesitate to risk alienating the most senior tribes loyal to the Houthis and his elder sons at a critical moment in the movement’s struggle with the Yemeni government in 2005-2006. Badr al-Din threw his weight behind Abdalmalik, the oldest child of his second sadah bride and his ninth oldest son, who had joined him on more visits to Iran than any other son except Husayn and who was a gifted religious scholar and orator.39 In the authors’ assessment, this showed that the man entrusted with leadership of the Houthi movement had to share the same vision and experiences as Badr al-Din and Husayn—that is, pursuit of an Islamic Revolution modeled on Iran and Hezbollah.40

Command Politics under Abdalmalik

In the view of the authors, the Houthi movement’s current leader Abdalmalik al-Huthi has demonstrated personal leadership qualities that are without doubt impressive: He is ruthless, pragmatic, unemotional, charismatic, and effective at building networks of personal loyalty and control.41 In Abdalmalik’s style of public talking, it is clear that he models himself closely on Lebanese Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.z The second to sixth wars against the Yemeni government in 2005-2010 saw Abdalmalik progressively develop and perfect his grasp over the military command structure.42 He toured the expanding frontlines of the war, and he successively sidelined older Houthi leaders of Husayn’s generation and disowned involvement in their tribal feuds.aa Instead, Abdalmalik cultivated a clique of younger “field commanders” (qa’id maydan)43 closer to his own age but often (significantly) just younger than him and thus less senior than him in years as well as religious education.ab These commanders were typically students of Husayn who had known each other in the Believing Youth camps and shared the formative experience of fighting in the six wars.44

One of the better known field commanders was the aforementioned Abdullah Yahya al-Hakim (Abu Ali),45 Abdalmalik’s military second-in-command after the sidelining of the qabili commander Abdullah Eida al-Razzami by 2006.46 Even accounting for some hyperbole and Abu Ali’s active intimidation of the press (which may generate hagiographic treatment),47 Abu Ali was (in 2006-2014) an unequaled military-political player with a track record of battlefield success.48 Abu Ali gained in importance throughout the six warsac and then took on a pivotal role in the Houthi consolidation of powerad after the collapse of the Yemeni government in the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011.ae Abdalmalik also overcame Yusuf al-Madani’s rivalry49 and kept him and Yusuf’s capable brother Taha as key field commanders, and Abdalmalik also eventually thawed hard feelings with Abdallah Eida al-Razzami by supporting the ambitions of al-Razzami’s eldest son, Yahya.af

Thus, Abdalmalik built a cohesive and trusted command group by the end of the sixth war in 2010—almost all young men (like Abdalmalik) in their late twenties or early thirties, with very similar religious backgrounds cultivated in the Believing Youth movement, and with strong personal intra-group affinity within the sadah elite, forged from childhood and through war.50 Others drawn from this “war generation” are Abdalmalik’s full brother Abdalkhaliq, a few years younger than him,51 and Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, a close first cousin of Abdalmalik, born just after Abdalmalik, who also emerged as a key advisor to Abdalmalik on social and political matters.52

In the authors’ assessment, this command cadre—the war generation, molded in their twenties as the six wars raged—are today the heart of the Houthi military and regime security command and control structure. They did not have much memory of the Zaydi revivalist movement before Husayn, before the Believing Youth camps, before Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah military support, and before the “the scream” (al-shi‘ar).53 In that sense, they are exactly what Husayn named them: the “followers of the slogan” (Ashab al-Shi‘ar).54

Abdalmalik kept these men alongside him as the Houthi movement transitioned from insurgents in 2010 to co-equals in the post-Arab Spring National Dialogue Conference between March 2013 and January 2014,55 and finally to the rulers of northern Yemen after their September 2014 coup against the U.N.-backed government.ag Yet, Abdalmalik also kept three influential older men in his military and security decision-making circle, and these may be particularly influential. One was Ahmed Mohammed Yahya Hamid (known as Ahmed Hamid or Abu Mahfouz), a key follower of Husaynah who is the director of the President of the Supreme Political Council Mahdi al-Mashat’s office and the powerful Government Works Authority,56 and is a few years older than Abdalmalik.ai According to Gregory Johnsen’s research, it was Ahmed Hamid who lobbied for Badr al-Din to hold open the leadership role for Abdalmalik in his early years as the ‘prince regent’ of the Houthi movement in 2005-2010.57 The second older advisor with direct access to Abdalmalik is Ahsan al-Humran (detailed below), who is Abdalmalik’s Preventative Security (al-Amn al-Waqa’i) chief58 and oversees the Houthi intelligence agencies.59 A third older figure—and the only one drawn from outside Abdalmalik’s circle—is Abdalkarim Amir al-Din, a much younger brother of Badr al-Dinaj and thus an uncle to Abdalmalik who is about 14 years older than him.ak Abdalkarim is the Minister of Interior in the Houthi-controlled Sana’a government with close ties to the IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah.60 But even in this case, Abdalmalik’s people seem to be slowly taking over: The Ministry of Interior (MoI) has been brought under the supervision of Ahsan al-Humran, and one of Husayn’s own sons, Ali, is positioned to succeed Abdalkarim at the MoI.al

Abdalmalik’s Jihad Council

The first three years of Houthi control of Sana’a and northern and western Yemen in 2014-2017 represented an uneasy partnership between the Houthis and their co-conspirator in the 2014 takeover, ousted president Ali Abdullah Saleh.61 This changed in December 2017 when long-standing tensions boiled over between Saleh’s forces and the Houthis, with Saleh being killed by Houthi forces on December 4, 2017,62 allowing the Houthis full and unfettered control of the Sana’a-based government and military for the first time.63

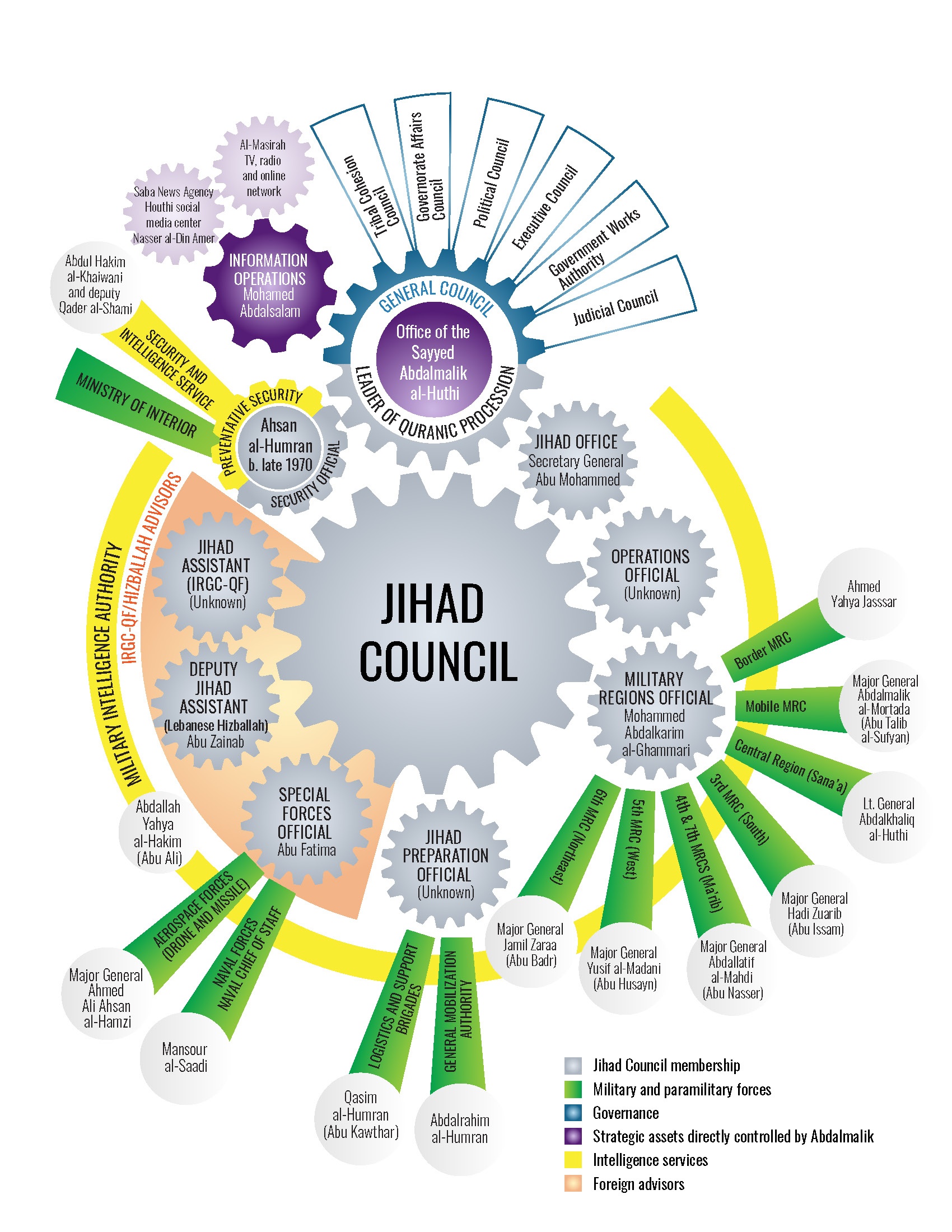

In the reorganization that followed, the Houthis’ Jihad Council, the movement’s supreme command authority, became more visible.64 This body had existed since 2010 or 2011, coincident with the sixth Sa`da war (and growing IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah involvement).65 It was a well-kept secret until around 2018, when testimony of its existence started to slip out with Saleh loyalist defectors and enhanced scrutiny of the Houthi leadership.66 With Saleh dead, the Jihad Council, consisting of approximately nine members, now exercised its authority without disturbance by its former ally. The Houthi Jihad Council bears an unmistakable similarity to Lebanese Hezbollah’s own Jihad Council,67 including the centralization of intelligence and counter-intelligence functions at Jihad Council level.68 Like Hezbollah’s Jihad Council (which is loosely overseen by Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah),69 the Houthi Jihad Council is formally led by the overall movement’s leader, in this case Abdalmalik al-Huthi, who has been styled “the Leader of the Quranic Procession.”70 In the authors’ assessment, there is a lot of anecdotal evidence that Abdalmalik rarely—if ever—physically meets with all the Jihad Council due to the stringent security precautions he takes, in which the leader remains distant and meets almost no other Houthi leadersam except perhaps Ahmed Hamid and Ahsan al-Humran.71

The Houthi Jihad Council has a small secretariat, the Jihad Office, which is led by an Abdalmalik loyalist known as (secretary general or rapporteur) Abu Mohammed.an Aside from an Iranian and Lebanese representative (see below), the remaining full members of the Jihad Council include an observer from the General Council (who also represents the Executive Council); the Operations Official; the Military Regions Official; the Jihad Preparation Official; the Special Forces Official; and the Security Official.72 As later sections will detail, the Operations and Military Regions officials assist with operational coordination functions across the different geographic military zones.73 Also discussed in following sections below, the Jihad Preparation Official focuses on recruitment, indoctrination, and force generation issues.74

Mohammed Abdal Salam,ao a close contact of Abdalmalik al-Huthi, sometimes attends the Jihad Council, seemingly in his non-public role as the head of Houthi media operations.75 Known best as the primary (Oman-based) point of contact between the Houthi movement and foreign journalists and think-tanks,76 Abdal Salam is the founding father of Houthi propaganda and disinformation capabilities.77 Working closely with the Iran-established Islamic Radio and Television Union (IRTVU)78 and Lebanese Hezbollah media organs,79 Abdal Salam and Houthi Information Minister Dhaif Allah al-Shami80 have built out what the authors’ assess to be one of the most powerful Houthi strategic attack capabilities, namely its raft of television, radio, and social media broadcasters.81 As well as controlling and censoring landline and cellular mobile internet inside Houthi-controlled Yemen,ap the Houthis have developed a powerful offensive capability aimed at controlling the international narrative surrounding the conflict in Yemen, which has sometimes achieved decisive strategic results.aq In addition to strong support from most of IRTVU’s members in television and radio,ar the Houthis directly control their own Beirut-based Al-Masirah satellite television station and the Sana’a headquarters of Yemen’s SABA News agency.82 Abdal Salam has a deputy, SABA News director Nasser al-Din Amer,as who heads up social media operations via a dedicated social media center.at This operation includes the centralized creation of messaging and hashtag campaigns, with well-managed “Twitter banks” of prepared content for crowds of supporters to draw upon and amplify, including with instructions of how to avoid being detected as bots by Twitter content algorithms.83 As is the case in Iraq,84 Lebanese Hezbollah’s Arabic-fluent media advisors seem to have played a long-standing role in building out Houthi information operation capabilities.au

The Special Forces Official represents the so-called “qualitative forces” such as missile and drone forces, naval capabilities, and technical training programs.85 These are strategic capabilities that are commanded directly by the Jihad Council.86 Historically, these Special Forces Officials are only usually identified after their death: One was Hamud al-Ghumran, who died in combat around 2017;87 the next was Hasan al-Jaradi88 (Abu Shahidav), a combat veteran from the very heart of Sa`da who was killed in Hodeida in 2018;aw and a final official called Mohammed Abdalkarim al-Humran was killed on the Marib frontline (at Sirwah) in 2020.89 The current Special Forces Official appears to be known only as Abu Fatima.90

The aforementioned Security Official (Ahsan al-Humran)91 appears to be dual-hatted as the head of the Preventative Security body, which oversees all the other intelligence agenciesax (with the possible exception of Military Intelligenceay). Preventative Security serves the same specialized leadership protection and regime security role as the Protective Security in Lebanese Hezbollah’s Jihad Council.az Ahsan al-Humran was a young loyalist to Husayn Badr al-Din who is just a few years older than Abdalmalik.ba He is one of many Humran family members in Husayn and Abdalmalik’s inner circles.92 (The Humran are a sadah family that traces descent to the Prophet.93) Ahsan al-Humran, one of the earliest Houthi commanders, replaced Abdalmalik’s long-term Preventative Security chief Abu Tahabb when the latter was removed during the intelligence reorganization in September 2019.bc

© The Washington Institute for Near East Policy (2022)

The IRGC Jihad Assistant and his Lebanese Hezbollah Deputy

It is no secret that the IRGC-QF (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force) and Lebanese Hezbollah supported Houthi territorial expansionism and military operations: In addition to U.N.bd and U.S.be statements to this effect, the IRGC-QF itself admits to its support.bf Alongside Abdalmalik, the IRGC-QF “Jihad Assistant” and his Lebanese Hezbollah deputy make up a triad at the heart of the Houthi war machine.94 IRGC-QF uses the same moniker—“Jihad Assistant”bg—in Iraq to describe its senior liaison officer with the top-tier Iraqi Shi`a terrorist group Kata’ib Hezbollah.95 Also similar to the Houthi case, the Jihad Assistant in Iraq has a Lebanese Hezbollah deputy, suggesting a kind of rough template in IRGC-QF interactions with partners and proxies.96 (In Lebanon, the Jihad Assistant is Lebanesebh and the title of the IRGC-QF senior advisor is unclear.) The key point is that the Jihad Assistant is always the senior military advisor to the leader,bi and in the case of Abdalmalik al-Huthi, this is an Iranian IRGC-QF officer with a Lebanese Hezbollah deputy.97

The exact nature of the relationship between Abdalmalik and the Jihad Assistant is obviously a well-guarded secret, but careful interviewing with persons at the edges of the Houthi security establishment can begin to build an intriguing picture.98 Though the exact identity of the current Jihad Assistant is not yet publicly known, a previous IRGC-QF official to play the role was IRGC-QF Brigadier General Abdalreza Shahla’i.bj As in Iraq, the Jihad Assistant is a brigadier general. His role is to advise the Houthi leader in “the path of strategic jihadist and military actions” and to “be a partner in making military decisions.”99 In terms of Iranian influence over key Houthi strategic decisions—such as entering or leaving ceasefires, or undertaking strategic attacks on Gulf States—there is no reliable data. In the authors’ assessment, Iran’s Jihad Assistant and Abdalmalik’s inner circle have strong incentives to conceal any evidence of Iranian influence in order to avoid damaging Abdalmalik’s credibility as a free-standing Yemeni leader.100 Where Iran uses its influence, it may often be to preach caution and the avoidance of over-reach and anecdotal evidence suggests Iran does tend to look nervously on major Houthi offensive actions.bk

The Jihad Council format was developed by Lebanese Hezbollah in order to communicate lessons learned across the group,101 and it might reasonably be expected to play this role in Yemen as well.102 The council might also logically provide a safe, economical, and unobtrusive way for the IRGC-QF to advise the Houthi movement.bl The Jihad Assistant also decides what kind of Iranian and Hezbollah technical assistance and hardware to provide, both using in-country training teams and stores, or by requesting new specialists or materiel from Iran and Lebanon.103 A small IRGC-QF and Lebanese Hezbollah staff, now reportedly numbering in the tens, not the hundreds,104 manages the practical arrangements, including advising on the operation of a small set of military industries.105

Lebanese Hezbollah’s deputy Jihad Assistant on the Houthi Jihad Council—currently an officer known as Abu Zainab106—has a more prominent role in practical training and equipping tasks.107 As noted by one of the authors (Knights) in a 2018 CTC Sentinel article on Houthi military operations,108 Lebanese Hezbollah advisors have long had more freedom of movement in Houthi areas of Yemen than Iranians.109 The Houthis appear less sensitive about Hezbollah involvement than about Iranian presence, possibly because Hezbollah is seen as an (elder) sister organization to Ansar Allah, while Iran is a foreign nation.110 Hezbollah’s Arabs (as opposed to Iranian Persians) can also blend in more easily with Houthi hosts and seem to have fewer operational security restrictions, allowing their advisors to visit the frontlines and move around the military zones.111

Overall, analysts might profitably reassess the longevity of Hezbollah military support to the Houthis, looking further back prior to 2010. Hezbollah itself has spoken of providing military advice to the Houthis as far back as 1992,bm but the major intensification might logically have occurred after the Hezbollah tactical victories over Israel in the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war and the skyrocketing of Hezbollah’s regional reputation.112 IRGC-QF appears to have based its earliest military assistance efforts to the Houthis out of Lebanon under the leadership of an IRGC-QF representative known as Abu Hadi113 and in partnership with Lebanese Hezbollah senior operative Khalil Yusif Harb.114 bn There are scattered but growing indicators of Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah sponsorship of the Houthis in the fourth, fifth, and sixth wars against the Yemeni government in 2008-2010.bo These appear to be the leading edge of Hezbollah advisingbp and IRGC-QF equippingbq of Houthi fighting units. Indeed, upon taking over Sana’a in September 2014, an early Houthi priority was the release of Hezbollah captives from government prisons, as well as Iranian nationals seized while delivering arms to the Houthis in 2013.br

Administration of the Houthi-controlled Military

When the September 21, 2014, Peace and National Partnership Agreement was signed on the day the Houthis seized Sana’a as a last ditch effort to save the post-Arab Spring peace process,115 the Houthis sought the integration of around 40,000 Houthi fighters into the state security forces, and the emplacement of a Houthi with familial links to the army, Zakaria al-Shami, as the deputy chief of staff of the Yemeni Ministry of Defense (MoD).116 After overrunning Sana’a in the coup of September 2014, the Houthis went further, directly controlling the MoD and MoI for the first time.bs In the latter, a slow-burning struggle for control of the police forces began between loyalists of Ali Abdallah Saleh, eventually ending with Saleh’s death at the hands of the Houthis in December 2017 and the appointment of Abdalkarim al-Houthi as Minister of Interior in 2019.117 In the MoD, the Houthis progressively co-opted Saleh-era generalsbt to serve alongside (and quickly under) senior Houthis. The most famous turncoat was the Houthi-installed Minister of Defense (at the time of publication) Staff Major General Mohammed Nasser al-Atifi,bu who attended Houthi ideological re-education, swore an oath of allegiance on the Qur’an, and plays an active part in Houthi propaganda operations.bv Of interest, the Houthis have not made sudden or sweeping changes to the Yemeni military and go to some lengths to portray this national institution as unchanged,bw an effort of uncertain success to hide the influence of the Jihad Council and minimize negative reaction from the military classes and other nationalists.118

The power behind the minister’s throne at MoD appears to be Staff Lieutenant Generalbx Mohammed Abdalkarim al-Ghammari (informally known as Hashim al-Ghammari),119 who was designated by the United States and the United Nations in 2021 for threatening the peace and stability of Yemen through his role in procuring and deploying explosives, drones, and missiles against targets inside and outside of Yemen.by Born in 1981,bz al-Ghammari is one of Abdalmalik’s generation, who was born in Al-Ahnum (then in Hajja governorate, but now in Amran) but grew up in Sa`da and received subsidized tuition from Husayn Badr al-Din al-Huthi at the Believing Youth camps.ca Interestingly, al-Ghammari had long been a beneficiary of the MoD as his father had died (accidentally, in a fire)120 while serving as a civilian in the MoD, meaning that he held an honorary rank simply to continue drawing his father’s income for the family.121 At the same time, in actuality, al-Ghammari was serving with the Houthi forces throughout the six wars, specializing in the production of landmines and improvised explosive devices in Sa`da, and having received Iranian training in explosives-handling.122 From 2014 onward, he worked at senior levels in MoD and became the senior Houthi in the ministry, working with a team of deputies led by Major General Ali Hamud al-Moshaki, a Houthi from a sadah family in Dhamar governorate.123

Yemen’s MoD was hardly a model of efficiency in the best of times,124 let alone under post-2014 conditions of blockade and with the ministry’s functions bifurcated between Houthi-held and government-held areas.125 Nevertheless, the ministry still has utility as a cover for the Jihad Council and is allowed to claim public credit for some enabling functions: personnel, training, and equipping and sustaining armed forces. In the authors’ collective view, the most important of these is the illicit procurement of military materiel from abroad, in violation of the U.N. arms embargo.126 By combining the pioneering research undertaken by Al Masdar Online127 with new interviews,128 a quite full picture can be constructed regarding the leadership of Houthi procurement and smuggling activities. Working directly with Mohammed Abdalkarim al-Ghammari is his assistant for military logistics, Major General Saleh Mesfer Farhan al-Shaer (Abu Yaser),129 a U.N. and U.S.-sanctioned Houthi official130 from Al-Safra district in the east of Sa`da.131 Al-Shaer not only heads up MoD logistics, including smuggling operations, but also plays the role of “Judicial Custodian” of an estimated $100 million worth of confiscated assets,cb some of which are made available for military use.cc

Under al-Shaer operates what appears to the authors to be a remarkably effective system for smuggling donated Iranian arms, technology, and fuel into Yemen,132 as well as providing the Houthis with a mechanism to control the profitable smuggling of civilian items like medicine, food, cigarettes, spare parts, consumer goods, fertilizers, and pesticides.133 Al Masdar Online134 and various U.S. and U.N. reports135 have done a perfectly good job of describing these operations in detail, so here, the authors will instead focus on command and control. Under al-Shaer is his deputy for procurement, Major General Mohammed Ahmed al-Talbi (Abu Jafar).136 At the Iran end, two Houthi liaison officers play a major role in procurement: An enigmatic figure known only as “M. S. al-Moayad” was described in the Al Masdar Online research as “the top coordinator of the smuggling operations based outside of Yemen.”137 Said al-Jamal, another Yemeni residing in Iran, was sanctioned by the United States on June 10, 2021, for running a sanctions-evasion network involving shipping and money exchange companies.138 A Yemen-based Houthi official Akram al-Jilani appears to coordinate a network of smuggling chiefs for the Red Sea (Ahmed Hels), the Gulf of Aden (Abdallah Mahrous), and the Gulf of Oman (Ibrahim Helwan and Ali al-Halhali).139

Onshore, al-Talbi has a transshipment network that handles trucking of smuggled goods to their storage locations. This network appears to be led by Akram al-Jilani, plus an Iranian-trained Yemeni logistician Mansour Ahmed al-Saadi,140 cd and (until his reassignment in September 2020)ce an Iranian-trained former bodyguard of Abdalmalik’s called Major General Hadi Mohammed al-Khawlani (Abu Ali).cf Little is known in the unclassified realm about the exact laydown of the Houthi warehousing and transshipment system, but judging by numerous Saudi airstrikes on such locations, the system is extensive.cg Iran, Lebanese Hezbollah, and the Houthis seem to have optimized the system to minimize the number of critical components that must be smuggled from Iran (complete weapons systems, ballistic missile fuel, guidance units, and quality high-explosives)141 and maximize local sourcing of military and dual-use materials.142 As noted in CTC Sentinel in September 2018, the military industries are likely limited to a few dozen warehouses, drone and missile workshops, landmine and sea mine production facilities, and training sites.143

A final interesting aspect of MoD’s role under the Houthis is its growing involvement in mass mobilization.144 Somewhat akin to the state adoption of militias under Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces,145 the Houthis have folded a number of their militias into the MoD administrative structure in order to provide them with legitimacy, payment, and support.146 Some of these so-called “Popular Committees’’ existed before 2014,ch and others are newer militias raised to give paid fighting jobs to Houthi-aligned tribes.ci Houthi sub-units are also nested within surviving Houthi-run Yemeni Army brigades, typically small cadres that stick with a Houthi commander as he is transferred between MoD postings.147 Since 2014—and particularly since the 2017 break with Ali Abdallah Saleh and his generals—the Houthi-run MoD has encouraged professional officers and personnel to take extended, partially paid home leave.148 The large resultant gaps in manpower have then been filled by a new General Mobilization Authority within MoD with an estimated 130,000 recruits from the poorer segments of society,149 for whom even a minimal payment (around $30 per month) is preferable to unemployment and complete poverty.150

The (unnamed) Houthi Jihad Preparation Official (also known as the Official of the Central Committee for Recruitment and Mobilization) is deputized by Abdalrahim al-Humran,151 who runs the General Mobilization Authority, which instructs local Houthi governorate supervisors, “neighborhood affairs managers,” and “neighborhood sheikhs”cj to comb households for military-age males.152 Jihad Preparation operates a basic three-tier military human resources system that recommends recruits for either special forces, technical specialist roles, or general military training.153 The entire MoD force is subjected to varying degrees of ideological indoctrination that was not common before 2014ck—and indeed a narrowing band of soldiers even remember the pre-2014 military.cl Thus, in the authors’ assessment, the Houthis truly do now control a military that is largely of their own crafting after just a few years of uncontested dominance.154

Most recently, the Jihad Preparation Official is also developing what appears to be a parallel mobilization reserve akin to Iran’s Basij forces.155 So-called Logistics and Support Brigades156 are being filled out and publicly paraded,157 and these appear to be reservist formations that include older or less capable recruits, often men who already have a civilian government or academic job.158 These brigades are being developed by Qasim al-Humran (Abu Kawthar),159 who previously oversaw the Ministry of Youth and Sports and worked under Yahya Badr al-Din, a full brother of Husayn, when Yahya was Yemen’s Minister of Education.160 When placed alongside each other, the various actions of the Jihad Preparation Official look, in the view of the authors, very much like similar IRGC or Lebanese Hezbollah efforts to militarize society and create the infrastructure for permanent mobilization.161

Operational Control of Combatant Units

As the Houthi movement progressively swallowed up many of the military forces in Yemen in 2014-2017, it began to improvise operational control and tactical control systems for employing much larger forces on an unprecedented number of frontlines.cm To some extent, the Houthi movement was used to fighting on multiple geographically separated fronts at the same time from the six Sa`da wars but not at the scale, expanse, complexity, or intensity of the fighting against the Saudi-led coalition from 2015 to the time of publication.162 Nor was the movement used to holding an operational reserve or allocating specialized enabler units from one widely separated front to another as needed.cn RAND’s excellent early study of the Houthi military organization rightly stresses the concept of qabyala, or “group and individual autonomy over stringent group solidarity,” meaning a highly decentralized fighting system.163 As the six Sa`da wars blended into state capture and the intense multi-front war against the Saudi-led coalition, the authors of this paper assess that a more professional and centrally coordinated system of operational control emerged, partly due to the assimilation of Saleh-era officers as well as due to IRGC-QF and Lebanese Hezbollah advice.164

On the Jihad Council, there is both an Operations Official and a Military Regions Official,165 and these closely linked roles are critical to operational control and coordination of the multi-front war.166 The Operations Official is nominally a Houthi commander called Brigadier General Ismail Awadh167 and his deputy Ibrahim al-Mutawakkil,co who are more important than the official MoD head of operations (G-3), former Saleh loyalist Major General Mohammed al-Miqdad.168 On a regular basis, Ibrahim al-Mutawakkil relocates an operations room169 that tracks the frontlines and movements of Houthi and enemy forces.170

Alongside the Operations Official is the Military Regions Official who engages directly with the major geographic commands—the Military Region Commands (MRCs)—to track their needs and the allocation of “enablers’’ to each MRC, such as drones, missiles, intelligence capabilities, armor, and artillery.171 At the time of publication, the preponderance of evidence suggests that the current Military Regions Commander is the dual-hatted MoD chief of staff, Mohammed Abdalkarim al-Ghammari, supported by a well-hidden assistant known only as “Sajjad.”172 The primary focus of this operations staff in the last two years has been coordinating the multi-axis campaign by MRCs 3, 4, and 6 (and the Central Region) to take Ma’rib city and its adjacent energy sites, with the close supervision (and sometimes over-involvementcp) of Abdalkhaliq al-Huthi, Yusif al-Madani, and Mohammed Abdalkarim al-Ghammari.173

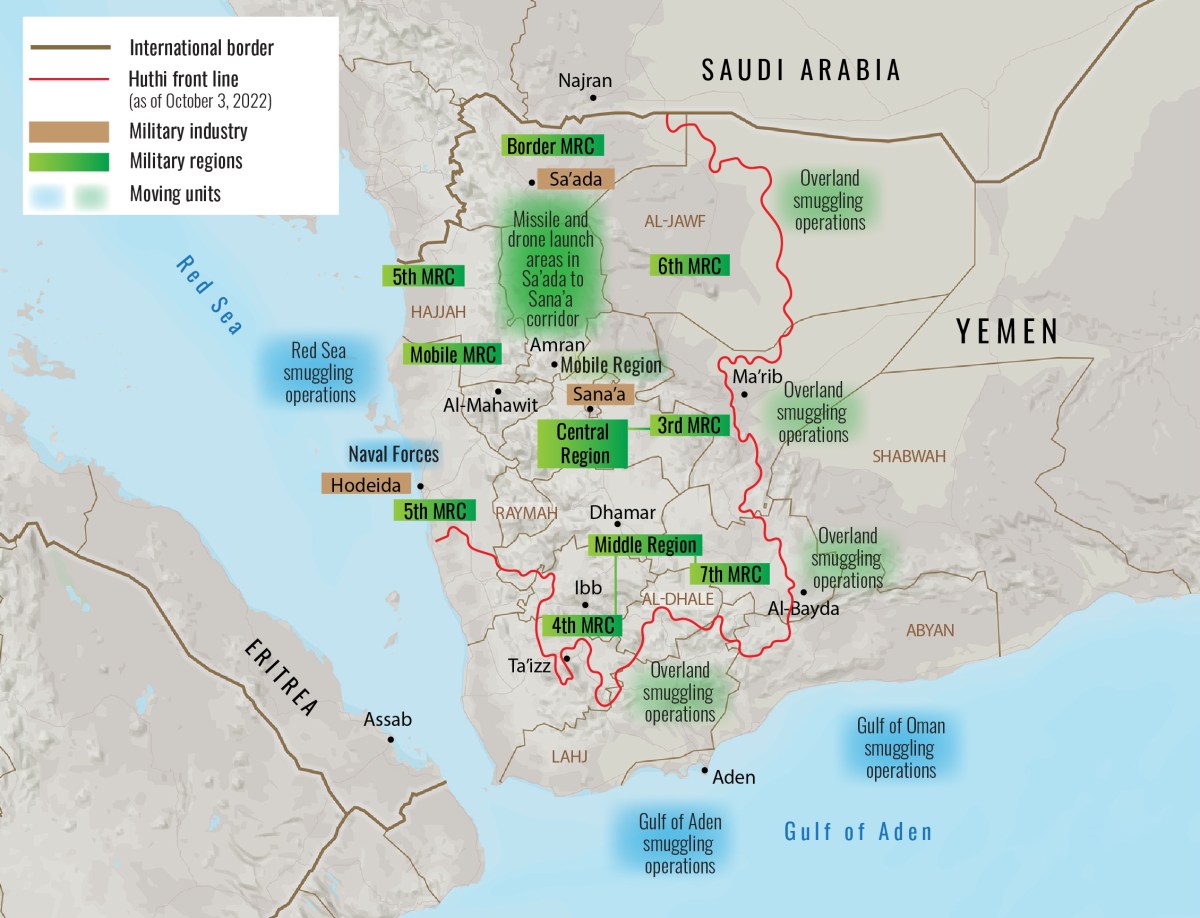

The MRCs are a system created by the U.N.-backed government after the fall of the Saleh government in 2012, a slight adjustment of the Saleh-era Military Districts.174 cq By the end of 2016, the Houthis had attained complete control of all the MRC headquarters and retained their basic structure as an organizing principle for the military.cr At the time of publication, the Houthi MRCs are led by the following officers:

Third MRC (Ma’rib) is led by Major General Hadi Zuraib (Abu Issam)cs and his influential aide, Brigadier General Naji Rabid.175 This MRC appears to be a very small command that operates under the overarching authority of the Central Region headquarters (see below) headed by Abdalkhaliq al-Huthi.176 The MRC often uses attached reinforcements when it is called upon to attack Ma’rib and its standing forces are reputedly smaller than other MRCs due to the small amount of terrain currently held by the Houthis in Ma’rib.177

The “Middle Region,” Saleh-era nomenclature that is used by the Houthis to cover the post-2012 Fourth and Seventh MRCs (the south, headquartered in Dhammar), covers the southern arc of governorates of Al-Bayda, Ibb, Ta’izz, Dhammar, Al-Dhale, Lahj, Shabwa, and Abyan.178 The overarching Middle Region comes under the control of Fourth MRC commander Major General Abdallatif Hamud al-Mahdi (Abu Nasser).ct Under al-Mahdi is the Seventh MRC (a sub-command covering Dhammar, Ibb, and Al-Bayda) commanded by Major General Nasser al-Mohammadi (Abu Murtadha al-Munabbahi).cu The southern front is largely a political and tribal engagement front,cv with active military operations in Ta’izz and Al-Bayda, at the western and eastern ends of the command’s frontage.179

Fifth MRC (the west, headquartered in Hodeida) covers Hodeida, Hajjar, Al Mahawit, and Raymah governorates, and was (until recently) actively led by veteran combat leader Major General Yusif al-Madani (Abu Husayncw). The command now appears to be led in an acting or transitional capacity by Madani’s former MRC deputy commander Hamza Abu Talib, a low-profile fighter who seems to have been groomed to hold the role.180 Like the southern front, the Red Sea coast is now mainly a tribal engagement and holding action by local auxiliary units raised by the Houthis to spread patronage among the tribes and coastal communities.cx

Sixth MRC (the northeast) covers Al-Jawf, Amran, and Sa`da, and is led by Major General Jamil Yahya Mohammed Zaraa (Abu Badr).cy

Border Region covers northern Sa’da, and is led by Ahmed Yahya Jassar, a Houthi official who formerly worked in the Jihad Office.181 Facing Saudi Arabia, the border region seems to have a special sub-regional command and to employ a number of long-establishedcz and new tribal auxiliary units.da

Praetorian Units in the Sana’a Area

There are two geographic commands in the vital Sana’a area. One is the so-called Central Region, which is again recycled Saleh-era nomenclature for the capital Sana’a and Sana’a governorate (plus parts of western Ma’rib), and is commanded by Abdalkhaliq al-Huthi (Abu Yunis),db the full brother of Abdalmalik.dc In the authors’ collective view, Abdalkhaliq exercises tactical control182 over all military forces in Sana’a, most importantly the Reserve Forces (four Presidential Protection Brigades and the Missile Brigades Group).183 Abdalkhaliq is not necessarily a skilled commander,dd but he leans on a number of capable subordinates, including the Central Region deputy commander Mohammed Abdallah (Abu Mahdi), who has held day-to-day command authority for Central Region forces since the removal of Saleh loyalists in December 2017.de

The Presidential Protection Brigades were the post-2012 renaming of the Saleh-era Republican Guards, who continued to serve under Saleh and his nephew Tareq Saleh until the Houthi-Saleh showdown in December 2017.184 In the months leading up to and immediately after Saleh’s death, the Presidential Protection Brigades were purged of Saleh loyalists and bolstered with Houthi recruits.185 The Presidential Protection Brigades are led by Houthi fighter Abdallah Yahya al-Hasani (Abu Mohammed al-Razehi), a veteran of the six wars who is similar in age to Abdullah al-Hakim (Abu Ali).186 The backgrounds of the four unit commanders of the Presidential Protection Brigades largely remain obscure, but at least one of the four commanders is a Houthi and has been in place as far back as 2014.df After seven years of re-staffing and indoctrination under overall Houthi control, the authors assess that the Presidential Protection Brigades today likely represent a fusion of Saleh-era elite materiel,dg select Republican Guard officers, Houthi supervisors and fighters, and Houthi-recruited troops who can only dimly remember a pre-Houthi era.187

A final elite reserve that appears to be cantoned in the northern Sana’a area188 is the so-called Mobile Region (also variously known as the Mobile Zone, the Mobile Forces, and the Central Intervention Forces).189 This is led by a Houthi commander called Abdalmalik al-Mortada (Abu Talib al-Sufyan), a veteran combat commander from the six wars.dh The Mobile Forces—a reputedly large strike forcedi—is centrally located and appears (in the authors’ assessment) to be postured to intervene against local uprisings, almost in the manner of a national (paramilitary) police force.190

Other elite forces are under the supervision of the aforementioned Special Forces Official (SFO) who is only known by the kunya Abu Fatima.dj The Special Forces Official’s area of responsibility seems to be the Houthi units that directly draw upon Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah support,191 and the SFO role is closely associated with the IRGC-QF Jihad Assistant and his Hezbollah deputy and seems to work directly to the Jihad Council.192 The Special Forces Official manages a network of safe houses, stores, and workshops in the Sana’a and Sa`da areas at which imported weapons are made ready or where smuggled components are integrated with in-country materials.193 There are indications that Abdallah al-Hakim (Abu Ali) and his Military Intelligence Authority have special responsibilities for the movement and security of Iranian and Lebanese advisors.dk One IRGC-QF unit associated with the Houthi qualitative forces is Unit 340,194 whose remit is to enable the transfer of military capabilities to partner forces.dl

The two main classes of elite forces that have been identified are “qualitative forces” and “special forces.”195 The so-called “qualitative forces” are split into two main sections:

Aerospace forces (drone and missile) are led by Yemen Air Force and Air Defense commander Major General Ahmed Ali Ahsan al-Hamzi, a Houthi from a sadah family who received military training in Iran according to the U.S. Treasury.196 Al-Hamzi is supported by a fast-rising young Houthi known as Zakaria Abdullah Yahya Hajjar,197 another Iranian-trained drone and missile specialist who is drawn from a sadah family from the Bani al-Harith area of Sana’a.dm The Houthi chief of staff Major General Mohammed Abdalkarim al-Ghammari and Minister of Defense Staff Major General Mohammed Nasser al-Atifi, the former head of the Missiles Brigade Group, work alongside the Special Forces Official to support the aerospace units.198

Naval forces (mines, missiles and boats) are led by the Naval Forces chief of staff Mansour al-Saadi, a long-standing Houthi commander on the Red Sea coast since 2015.199 According to the U.S. Treasury, al-Saadi “masterminded lethal attacks against international shipping in the Red Sea” and received military training in Iran.200

Perhaps surprisingly, the grouping and organization of light-infantry-type ground “special forces” in the Houthi order of battle is more of a mystery. Since at least the sixth Sa`da war, there has been a noted similarity between Houthi commando operations and Hezbollah border-raiding tactics against Israel.201 As noted in the September 2018 CTC Sentinel article by one of the authors (Knights), “Houthi forces have achieved great tactical success against Saudi border posts through offensive mine-layingdn on supply routes and ATGM [anti-tank guided missile] strikes on armored vehicles and outposts.”202 Yet, it is less clear how elite light infantry forces are organized and grouped. Certain Houthi ground forces units have been framed as elite light infantrydo and land special forces commanders appear to have been identified in the past after being killed.203 dp Though most accounts of specifically named Houthi “special forces units” appear apocryphal,dq there does seem to be a training program to enhance the capabilities of land forces commanders, staff officers, and tactical operators in light infantry fighting and to reinforce ideological fervor.204 One example of units that appear to have received such strengthening are the Nasser brigades on the Red Sea coast, which attained a kind of honorific status (nukhba, meaning elites) after receiving such training. The aforementioned Mobile Region could be another example of an effort to develop elite light infantry strike forces.205

Analytic Conclusions

The Houthi movement is an evolving subject, and the trendline, in the authors’ view, is toward a centralization of command and control, and greater coercive power in the hands of the top leadership.206 When RAND undertook its pioneering study of the Houthis in 2010,207 based on evidence available then, it was absolutely right to describe the Houthi movement as a “heterogeneous” organism that appeared decentralized and non-cohesive, with its leaders cloistered in rural redoubts and unable or unwilling to take authoritarian control of the movement.208 The RAND authors Barak Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells presciently anticipated that the movement might move beyond a fighting style of “unconnected fighting groups” to form “a coordinated, synchronized fighting force.”209 Likewise, anthropologist Marieke Brandt correctly portrayed the traditional role of the sadah as dependent on tribal protection, turning their weakness (versus tribal groups) into a strength by playing the historic role of mediator and arbiter of tribal law and social peace.210

The situation described above has arguably changed. Abdalmalik al-Huthi and his inner circle of sadah followers are now anything but weak mediators, bolstered now by over a decade of internal security advice and procedures provided by Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah.211 Whereas RAND rightfully doubted (based on data available in 2010) that the Houthi leaders could rule by “authoritarian control of physical coercion,”212 dr the coercive machine that is available today is far more capable of suppressing dissent.213 As Adel Dashela noted in a 2022 study on tribal dynamics in Houthi-controlled northern Yemen,214 ds the Houthi movement now employs “a totalitarian mindset, applying a logic of oppression and dominance towards the northern tribes” that has allowed the temporary subjugation of tribal power.215 Even skeptics of Iranian involvement such as Marieke Transfield draw attention to strong “parallels in the Hizballah takeover of West Beirut in 2008 and the Houthi grab of power in 2014 [that] also suggest some exchange on military strategy.”216

Likewise, previous scholarship was absolutely right to point to a lack of strong public evidence of Iranian mentorship in the Houthi movement,217 but this has been rendered moot by subsequent events and outpaced by the gradual release of materials on the growing role of the IRGC-QF and Lebanese Hezbollah during the years in which the Houthi movement became extraordinarily successful on the battlefield, namely from the fourth Sa’da war in 2007 to the present day.218 Badr al-Din, Husayn, and Abdalmalik, as well as many other Houthi commanders, drew heavily on the examples and the political and military models of the Islamic Republic of Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah. In the formation of the Jihad Council, the Houthis deliberately adopted Hezbollah’s organization model, and in the acceptance of an IRGC-QF Jihad Assistant at the heart of Houthi military strategy, the Houthis adopted the same mentoring model as Iraqi terrorist group Kata’ib Hezbollah. The Houthi military has adopted many features of IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah counterparts, including top-level command and control architecture, preventative security arrangements, information operations, training, covert procurement, military industrialization, drone and missile forces, and guerrilla naval operations, to name a few.219 Indeed, the process is not yet finished: The Houthi-controlled military is still in chrysalis form—part way through its metamorphosis into what the authors assess to be a very close clone of the IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah military and security systems, with the birth of a Basij-type mobilization and internal security system already coming into view.dt

Is it possible that IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah provided this transformative support but sought no influence over the Houthi decision-making system? Based on the authors’ collective investigation, Iranian leaders do utilize a very soft touch, but this is precisely because their alignment of ideology and goals is already so close to Abdalmalik and his inner circle.220 As noted earlier in this piece, conflict and terrorism analysts may find it profitable to look harder and further back for the beginnings of IRGC-QF and Lebanese Hezbollah interactions with the Houthi leaders. It may also be worth re-examining the drivers of the Houthi-IRGC and Houthi-Hezbollah relationships. Were these mainly relationships of necessity, driven to unintended levels by the wars in Yemen, or were they highly intentional relationships of choice from the outset, based on a common worldview?

Whenever and however the Houthi relationships started with IRGC-QF and Hezbollah, these relationships now appear to be exceedingly strong and stable.221 In the assessment of the authors, Iran sees the Houthis as a remarkable asset, on par with Lebanese Hezbollah, albeit at an earlier stage of development.du In the authors’ assessment, based on investigative work in both Iraq and Yemen, the Houthis are respected by IRGC-QF to a greater extent than Iraqi militias because the Houthis have proven themselves to be more capable, cohesive, and disciplined.222 The Jihad Assistant oversees a relationship with the Houthis that is reputedly warm, discreet, respectful, and highly valued by both sides.223 According to the authors’ collective research, Lebanese Hezbollah’s relations with the group appear similarly respectful, egalitarian, and brotherly, which (again) is often not the case between Lebanese and Iraqi groups.224 dv Neither Iran nor Hezbollah appear to play in the internal politics of the Houthis to a measurable extent, in part because the movement—unlike Iraqi militias—has a unity and discipline that both Iran and Hezbollah appreciate in a partner.225

Iranian and Lebanese interaction with the Houthi leadership is so narrowly focused on Abdalmalik and the Jihad Council that it is, in the authors’ collective assessment, probably invisible to most Houthis and to Yemenis and the world at large.226 Though it is not possible to identify any Houthi command decisions in which IRGC-QF or Hezbollah forced the Houthis to decide differently than they might independently have, it is assessed as probable that Iran has built up sufficient goodwill and credit with the Houthi leadership that it can selectively call on the Houthis to serve Iranian interests in ways that may incur new costs or difficulties for the Houthis.227 If Abdalmalik and his inner circle decide to cede certain strategic decisions to Iran, almost no one would know it had happened and no one would be in a position to protest within the centralized totalitarian structure of today’s Houthi movement.

Therefore, even if the Houthi relationship with Iran and Hezbollah is not that of a proxy, this article argues that the connection is arguably that of a strong, deep-rooted alliance that is underpinned by tight ideological affinity and geopolitical alignment.228 This suggests that the relationship will only grow closer, regardless of whether fighting in Yemen waxes or wanes, and that the Houthis may play an integrated role in future Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah military campaigns.dw If a key Houthi supporter of close relations with Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah, such as Abdalmalik, were to die or be otherwise replaced, there is now a broad-based set of leaders whose whole ideological and political upbringing will predispose them to continue this beneficial and warm relationship.229 In the authors’ view, the risk that a ‘southern Hezbollah’ might emerge is arguably now a fact on the ground. CTC

Dr. Michael Knights is the Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow with the Military and Security Program at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He has traveled extensively in Yemen since 2006. Twitter: @mikeknightsiraq

Adnan al-Gabarni is a Yemeni journalist specializing in military and security affairs. He previously worked for Al Masdar Online. Twitter: @Aljbrnyadnan

Casey Coombs is a researcher at the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. He was based in Yemen in 2012-2015 as a freelance journalist. Twitter: @Macoombs

© 2022 Michael Knights, Adnan al-Gabarni, Casey Coombs

Substantive Notes

[a] Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells noted that the Houthis are known by a variety of names: “the ‘Huthis’ (al-Huthiyin), the ‘Huthi movement’ (al-Haraka al-Huthiya), ‘Huthist elements’ (al-‘anasir al-Huthiya), ‘Huthi supporters’ (Ansar al-Huthi), or ‘Believing Youth Elements’ (‘Anasir al-Shabab al-Mu’min).” Barak Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells, Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen: The Huthi Phenomenon (Santa Monica: RAND, 2010), p. 189.

[b] The U.S. government noted: “Ansarallah leaders Abdul Malik al-Houthi, Abd al-Khaliq Badr al-Din al-Houthi, and Abdullah Yahya al-Hakim remain sanctioned under E.O. 13611 related to acts that threaten the peace, security, or stability of Yemen.” “Revocation of the Terrorist Designations of Ansarallah,” U.S. Department of State, February 12, 2021.

[c] The truce was up for renewal on October 2 but had not (at the time of publication) been renewed immediately and thus lapsed, perhaps temporarily.

[d] The Saudi and Gulf military commitment in Yemen gives a competitive advantage to Iran, forcing Gulf missile defenses and other resources to be deployed away from the Gulf littoral shared with Iran and toward a new western and southern front. The Yemen war is a geopolitical lever on the Saudis that Iran, through its support to the Houthis, may be in a position to manipulate. See Gerald M. Feierstein, “Iran’s Role in Yemen and Prospects for Peace,” Middle East Institute, December 6, 2018, and Thomas Juneau, “How Iran Helped Houthis Expand Their Reach,” War on the Rocks, August 23, 2021.

[e] As earlier footnotes detail, the Houthis have been designated as a threat to the peace and stability of Yemen. They have also fired anti-shipping missiles at U.S. naval vessels, kidnapped American citizens, fired missiles and drones at Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and threatened Israel. For a review of the case for designating the Houthis as terrorists, see Lucy van der Kroft, “Yemen’s Houthis and the Terrorist Designation System,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT), June 2021, pp. 11-16.

[f] For instance, then president of the Houthi Supreme Political Council Saleh al-Samad, said the Houthis would “cut international navigation,” and the Houthi television channel Al-Masirah added that al-Samad threatened to “block the Red Sea and target international navigation.” See Ali Mahmood, “Houthis threaten to block shipping traffic in Red Sea,” National, January 9, 2018.

[g] Al Masdar Online and the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies both operate extensive contact networks and research capabilities focused on (and present in) Houthi-held northern Yemen.

[h] The Zaydi branch as a whole cannot be clearly defined as Sunni or Shi`a. Qom-trained theologian Mehdi Khalaji reflects a mainstream view that Zaydi jurisprudence is most similar to the Hanafi and Shafei (Sunni) schools of Islamic law. Like Sunni branches of Islam, most Zaydis do not reject Abu Bakr, Omar, and Uthman as the Prophet Mohammad’s rightful successors. Yemeni Zaydism differs from prevalent “Twelver” Shi`a Muslims dominant in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon because Twelvers see the proper line of descent from Prophet Mohammad running via one descendent (the fifth imam, Mohammed al-Baqir) to a messianic 12th imam, while the “Fiver” Zaydis believe in a different line of descent and method of succession branching from their preferred fifth imam, Zayd. See Mehdi Khalaji, “Yemen’s Zaydis: A Window for Iranian Influence,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, February 2, 2015. See also “Appendix B: Zaydism” in Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 290-294. See also “From Insurgents to Hybrid Sector Actors? Deconstructing Yemen’s Huthi Movement,” Instituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale, April 2017.

[i] Badr al-Din’s family are adherents to the Jarudi sect of the Zaydi branch of Islam (with the other contemporaneous sects being Sulaymaniya, Jaririya, Butriya, and Salihiya). Houthi news sources tend to downplay this fact, but even their own leaders occasionally reference it. Mohammed Azzan, a co-founder of Believing Youth and a leading mainstream Zaydi revivalist, identifies the Houthi movement as “a political movement with a religious background belonging to the Zaydi sect, especially the Jarudi current.” See Mohammed Azzan, “The Houthis directed the path of ‘believing youth’ to an extremist project,” Alameenpress.net, accessed on October 11, 2022. For broader studies on the Jarudi aspect of the Houthi movement, see Nasser Abdullah Al-Qafari, “Zaydi Innocence from the Houthis,” Al Bayan Magazine 337 (2015) and also the following two Arabic books: Ahmed Mohammed al-Daghshi, “The Houthis: A Comprehensive Methodological Study,” Arab House of Sciences, December 2009 and Suleiman al-Saleh al-Ghosn and Suleiman Bin Saleh Bin Abdulaziz, “The Truth About the Houthis,” King Fahd National Library, 2010.

[j] The Jarudi are the closest of any Zaydi sect to mainstream “Twelver” Shiism practiced in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon. Unlike other Zaydis, and in keeping with mainstream Shiism, the Jarudis reject Abu Bakr, Omar, and Uthman as usurpers of Ali’s right to be Prophet Mohammad’s rightful successor. On Jarudi beliefs, see the excellent tables and discussion in “Appendix B: Zaydism” in Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 290-294. See also Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “The Houthis’ endgame in Yemen,” Al Jazeera Opinion, December 21, 2017, and Noman Ahmed and Mahmoud Shamsan, “Analysis: Origins of the Houthi supremacist ideology,” Commonspace, August 23, 2022.

[k] Husayn embraced all forms of political Islamic activity. He was briefly a member of Yemen’s parliament for a year. He broke with mainstream Zaydism by proselytizing and propagating his political beliefs in a manner that was unusual for Zaydis. Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 290. See also Marieke Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen: A History of the Houthi Conflict (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 150.

[l] Qom-trained theologian Mahdi Khalaji noted that “Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, led by a Twelver Shiite jurist, was a theological surprise for Zaidis in Yemen because they had believed that such uprisings were what differentiated them from Twelvers. Subsequently, the Twelver branch became so appealing to Yemeni Shiites that many of them traveled to Iran to learn more about it.” See Khalaji.

[m] Khalaji quotes Hassan Zaid, the leader of the Houthi political party Al-Haq, as telling him: “We believe that Khomeini was a true Zaidi. Theologically our differences with Hezbollah and the Iranian government are minor, but politically we are identical.” Khalaji.

[n] Abdalmalik’s birthdate is variously given as between 1979 and 1982, depending on the source. The authors assess, based on the preponderance of anecdotal reporting, that Abdalmalik’s birthdate is closer to 1979. Drawn from details from interviews for this study. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request. See also “Yemen designations,” U.S. Department of Treasury, April 14, 2015.

[o] For years after the war, Husayn berated Yemen’s government for fighting the Islamic Republic of Iran. See this audio recording: Husayn Badr al-Din, “A rare clip of the founder of the Houthi movement, Hussein al-Houthi, in which he threatens to punish the Yemeni army for its participation against Iran,” YouTube, May 8, 2017, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UZZt810mvFE

[p] Husayn used to repeat the phrase that “the nation will not defeat America and Israel without the leadership of Ahl al-Bayt,” meaning the sadah, seeing himself as a Hashemite version of Usama bin Ladin. For instance: “On the day [Osama] appeared, and we saw many people thinking that he would be the savior of the nation, we would say: ‘No, that will never be achieved through his hands … The nation’s salvation from the mid guidance it is experiencing will only be at the hands of the family of the Messenger of God.’” See Husayn Badr al-Din al-Houthi, “Lessons from the guidance of the holy Quran: The responsibility of Ahl al-Bayt, peace be upon them,” Huda.live.com, December 21, 2002.

[q] Forty students per year were paid for by the Iranian authorities, a flow that continued from 1994 to the blockade of Yemen after the Houthi coup in September 2014. Drawn from an interview for this study. Names of interviewee, and date and place of interview withheld at interviewee’s request.

[r] Forty students per year in the 20 years between 1994 and 2014 equals 800 individual students.

[s] Brandt notes: “To many Zaydis, the new dynamic, self-assertive Zaydi activism, which had emerged from the confrontation with Sunni extremism, was quite unfamiliar; some suspected that the Houthi movement was in fact not a revival of Yemeni Zaydism, but rather an externally operated movement influenced by Iranian Twelver Shiism.” Brandt, p. 146. Jarudism and Twelver rituals were hidden in the 1980s as the Yemeni government persecuted Jarudis and Twelvers for their connection to Iran, which Yemen fought in the Iran-Iraq War as an ally to Iraq. See Khalaji. Today in Houthi-controlled areas, Twelver religious practices such as the public commemoration of Ashura are becoming widespread in a way that is foreign to mainstream Yemeni Zaydism. See Cameron Glenn, Garrett Nada, and Mattisan Rowan, “Who are Yemen’s Houthis?” Wilson Center, July 7, 2022.

[t] The 2010 RAND study took a muted view of Iran’s influence on the Houthis. See Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 120-123, 170-171. Over time, more evidence has emerged showing the longevity of Iran’s covert operations in Yemen, including through leaked documents. For instance, see the interesting document archive stretching back to the 1980s at “Houthis in special documents( 2): Comprehensive intelligence report on Iranian efforts to find a foothold in Yemen since the 1980s,” Al Masdar Online, April 16, 2020. See also the detailed revisionist text: Oved Lobel, “Becoming Ansar Allah: How the Islamic Revolution Conquered Yemen,” Report No. 20, European Eye on Radicalization, March 2021.

[u] The RAND study notes that “around 15,000 boys and young men had passed through Believing Youth camps each year,” adding that the Believing Youth were an ideal mechanism to groom a fighting cadre, noting: “that demographic base—or their younger siblings—went on to provide a recruitable hard core, susceptible (or vulnerable) to the masculine assertion furnished by resistance and armed activity … the rituals or gatherings appropriated by the Houthis—where adolescents and young adults congregate together with ‘adult’ fighters—make ideal environments for socialization and recruitment of youth.” Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 254.

[v] Al-Madani was born in 1977 in Muhatta, in Hajjar governorate, but he spent his youth as one of the most promising students of Husayn Badr al-Din al-Huthi in Sa`ada. He married one of Husayn’s daughters (a sharifa, or daughter of a sadah) and gained a powerful reputation as a commander in all the six wars and the fighting since then. His brother Taha al-Madani, another very senior Houthi field commander, was killed in 2016, seemingly in Lahj. On May 20, 2021, al-Madani was sanctioned by the United States for threatening the peace, security, and stability of Yemen, followed by the United Nations on November 9, 2021. See “Treasury Sanctions Senior Houthi Military Official Overseeing Group’s Offensive Operations,” U.S. Department of Treasury, May 20, 2021, and “Yusuf al-Madani,” United Nations Security Council, November 9, 2021. Details gathered from interviews for this study. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[w] Abu Ali is believed to have been born in 1984-1986 to a sadah family (al-Moayyed) from Dahyan, Sa`ada. His early arrest by the Saleh government in May 2005 for undertaking assassination and roadside bomb attacks in Sana’a suggests that (even in the early years of the war against the government) he had received covert operations training of a kind different from most Houthi tactical commanders. See “Houthis in Special Documents( 6) .. Report from the Counter-Terrorism Center on the crime for which Abu Ali al-Hakim, Fouad, Mohammed al-Imad and others were imprisoned,” Al Masdar Online, May 9, 2020. See also his U.N. and U.S. government sanctions designations at “Abdullah Yahya al-Hakim,” U.N. Security Council, November 7, 2014, and “Yemen-related designations,” U.S. Department of Treasury, November 10, 2014.

[x] Sadah leadership (through religious authority) of qabili social groupings is an old and tested formula in northern Yemen. Adel Dashela, “Northern Yemeni Tribes during the Eras of Ali Abdullah Saleh and the Houthi Movement: A Comparative Study,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, February 16, 2022, pp. 3, 12, 13.

[y] Mohammed was only released in 2006. Brandt, p. 172. Omar al-Amqi related from his interview with Mohammed Badr al-Din: “When I asked Mohammed why he didn’t take over the leadership of the organization, he replied smiling: ‘I was in prison, and my brother Abdulmalik was a lieutenant of my father and close to him, and I was not released from prison until the situation is like this as you can see.’” See Omar al-Amqi, “Why didn’t the Houthi leadership devolve to Mohammed Badreddine?” Al Masdar Online, April 11, 2010.

[z] In the authors’ assessment, Abdalmalik deliberately uses the same calm tone as Nasrallah, inflecting and raising his voice only in specific phrases to fire up the audience in a way that mimics the Hezbollah leader. In addition to rhetorical similarities, they both wear a ring on the little finger of their right hands, often appear in front of the same blue background, and constantly praise each other in letters. For an example of similar rhetorical styles, see “Hezbollah and Ansar Allah, the Soldiers of God that strike in the ground,” YouTube, October 12, 2016. Qom-trained theologian Mehdi Khalaji has also noted Abdalmalik’s apparent fascination with Nasrallah. See Khalaji.

[aa] For instance, in March 2005-June 2007 (2nd to 4th war) feuding between al-Razzami and the Al Mahdi clans, Abdalmalik distanced himself and explicitly did not support his father’s friend, al-Razzami. Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, pp. 185, 309. See also Brandt, pp. 122, 129-130.

[ab] In the authors’ collective view, this is significant. Age is important in the Arab world. Even a few years’ seniority in age between men gives a kind of precedence that can be exploited by the elder man.

[ac] Abu Ali was in prison in 2005, before breaking out on January 27, 2006. See Brandt, p. 189. Thereafter, Abu Ali was critical in many fronts, especially late-war fighting in 2009-2010 in Manabbih. See Brandt, pp., 297, 304-305.

[ad] Abu Ali is also believed to have played a major role in establishing the Houthi tactic of setting up local supervisors (mushrifeen) across all districts in Yemen and within all ministries and major military units, akin to a political commissar system of surveillance and parallel authority. See Adnan al- Gabarni, “Who are the Houthis? The hidden structures and key leaders who actually run the organization,” Al Masdar Online English, March 14, 2022.

[ae] Abu Ali was described by Brandt as the key military player in post-2010 Houthi takeovers and tribal fighting in Dammaj, Amran, and Sana’a. See Brandt, pp. 279-280, 334-335.

[af] Yahya appears to have been born in 1987, making him in his mid-thirties now, while his father Abdullah Eida al-Razzami is in his mid-sixties. See Gregory D. Johnsen, “The Kingpin of Sana’a – A Profile of Ahmed Hamed,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, May 18, 2021. In May 2022, Yahya was appointed head of a Houthi delegation sent to Amman, Jordan, to negotiate with the internationally recognized government over the reopening of roads in Taiz, as part of the U.N.-brokered truce that started in April 2022 (and which has lapsed since October 2, 2022, at the time of writing). Adnan al-Gabarni, “Why did al-Houthi choose Yahya al-Razami as a representative in the negotiations to lift the siege of Taiz?” Al Masdar Online, May 27, 2022.

[ag] As Al Masdar Online has chronicled in great detail, the Houthi shadow government represents a parallel system of supervisory bodies in which real policy-making authority is vested, under which the formal Yemeni government architecture exists to execute Houthi orders. Under Abdalmalik’s Office of the Sayyed, there is the General Council, Executive Council Supreme Political Council, Government Work Authority, Governorate Affairs Council, Judicial Council, and Tribal Cohesion Council. These are almost all run by Abdalmalik’s hand-picked cadre of thirty-somethings: for instance, a close confidante Safar al-Sufi at the General Council; groomed Abdalmalik loyalist Qassem al Humran at the Executive Council; Abdalmalik’s friend Mahdi al-Mashat at the Supreme Political Council; Mahmoud al Junaid at the Government Works Authority; plus Mohammed Abdalsalam and Abdalmalik al-Ajri as his foreign representatives and spokesmen. As with any rule, there are exceptions—one being the involvement of Husayn-era leaders like Mohsen al-Hamzi (Judicial Council head) and Saleh Mesfir Farhan al-Shaer (judicial guardian of confiscated properties) under Abdalmalik. See al-Gabarni, “Who are the Houthis?” Details also topped up with interviews for this study. Names of interviewees, and dates and places of interviews withheld at interviewees’ request.

[ah] Greg Johnsen says Ahmed Hamid was born in 1972 and was the key backer of Abdalmalik as the successor to Husayn, energizing others to push Abdalmalik’s takeover. See Johnsen.

[ai] The United Nations reported in 2021 that Ahmed Hamid leads the Supreme Political Committee of the Houthi movement (its politburo, in effect) and the Houthi-controlled Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA), where he oversees “intimidation of opponents, corruption activities including the diversion of humanitarian aid.” See “Letter dated 22 January 2021 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, January 25, 2021, p. 17. See also Johnsen.

[aj] Badr al-Din al-Huthi was born in the early 1920s while his brother Abdalkarim was born around 1965, making him slightly younger than (his nephew) Husayn Badr al-Din (born in 1956 or 1959). Brandt, p. 172; Salmoni, Loidolt, and Wells, p. 106.

[ak] Abdalkarim is regularly mentioned as one of the top three power blocs within the Houthi movement. See Johnsen. See also Abdalkarim’s involvement with the mushrifeen system in “The Houthi Supervisory System,” Yemen Analysis Hub, ACAPS, June 17, 2020, p. 3. One report places Abdalkarim as Abdalmalik’s designated successor. See “Abdel Malik al-Houthi Chooses His Uncle to Succeed Him,” Asharq Al-Awsat, September 16, 2018.