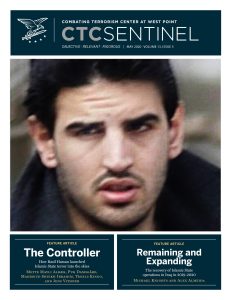

Abstract: After trying but failing to assassinate a critic of Islam in Denmark in 2013, Basil Hassan, a radicalized Danish engineering graduate of Lebanese descent, left Denmark for the final time and became one of the most dangerous international attack operatives within the Islamic State. As the key figure in a drone procurement network that stretched from Europe through Turkey to Syria, he was instrumental in furthering the Islamic State’s drone-warfare capabilities. As “the Controller” behind the 2017 Sydney airline plot, he pulled the strings from Syria in directing one of the most ambitious and innovative terrorist plots ever seen. Denmark’s police and security services have been on the trail of Hassan since soon after his assassination attempt. Despite a setback in 2014 when Turkey arrested Hassan but then let him go, Danish investigators were eventually able to shut down his drone procurement network and secure the conviction of his accomplices in Denmark. There are claims Hassan was killed in the second half of 2017, but his death has never been confirmed and he may remain a threat. Authors’ note: The case against the Danish drone terrorist network has been appealed to the High Court in Denmark.

One day in February 2013, the bell rang at the home of well-known historian and Islam critic Lars Hedegaard on a residential street in Copenhagen. It was a mailman delivering a parcel, and Hedegaard went down to the front door to receive it. According to the police, the mailman drew a gun and fired a shot at close range that barely missed Hedegaard’s right ear. They got into a scuffle, and the assailant fled on foot.1

Danish police believe Basil Hassan, a radicalized Danish-Lebanese engineering graduate, was the fake mailman. But by the time, weeks later, that they established he was a suspect (which they would keep secret as their investigations progressed),a Hassan had left the country to embark on the next stage of a terrorist career that would see him become one of the most dangerous Islamic State international attack operatives.

This article tells the story of Hassan’s path to terrorism, his role in building up the Islamic State’s drone-warfare program, and his orchestration of the Islamic State’s 2017 Sydney airline plot.2 It also tells the story of the multi-year investigation by Danish police and security services, which eventually shut down the drone procurement network and put several of Hassan’s accomplices behind bars. This article is based on a two-year investigative report by the authors for DR, the Danish public broadcaster, that included reporting inside Syria and Iraq, as well as in Turkey, Denmark, other European countries, and the United States. These efforts culminated in the broadcast of two documentaries, a 16-episode podcast series, and the publication of a series of news reports in 2019.3 The article draws on hundreds of pages of transcripts from the trial of Hassan’s drone procurement accomplices in Denmark, which was attended by the authors and resulted in three individuals—Fady Mohammed, Coskun Simsir, and Umut Olgun—being convicted in December 2019.b It also draws on dozens of interviews with close associates of Hassan as well as law enforcement and counterterrorism officials in Denmark, Europe, the Middle East, and the United States.4

The Making of an Assassin

On a summer’s day in 1987, in a housing project in the medium-sized provincial Danish town of Askeroed near Copenhagen, Basil Hassan—the youngest of three children—was born.5 As a child, Hassan played soccer in the yard and Donkey Kong on his Game Boy with the other boys. The Hassans were moderate Muslims, and their home seemed open and loving. When Basil Hassan was a teenager, the family moved to the multicultural district of Nørrebro in Copenhagen. Hassan did well in high school and was popular, however, he and one particular schoolmate drew attention. Hassan and his friend, Rawand Taher, sometimes dressed in Islamic clothing, and they eagerly discussed religion during breaks and warned their classmates against being non-believers.6

In their 2006 school yearbook, their classmates jokingly predicted that the two friends would end up as the leaders of “the new Islamic State” and that the Danish intelligence service should “watch out.”7 Ironically, Hassan and his friend would become top Islamic State terrorists less than a decade later. Taher became front-page news in Denmark when he was killed in 2015 in a targeted U.S. drone strike in Syria.8

In a 2006 class photo, Hassan and Taher are seen standing side by side, smiling. By that time, Hassan had started frequenting Islamist circles in the Greater Copenhagen area, and several of Hassan’s acquaintances had been arrested in the first Danish jihadi terrorism case after 9/11. In late 2005, Danish authorities charged four people in the Copenhagen suburb of Glostrup with terrorism offenses. Hassan was questioned as a witness, making it clear that he has been on the Danish Intelligence and Security Service’s (PET) radar since at least 2006. In fact, because of his close relations to several convicted Danish jihadis, PET tried to recruit Hassan as an informant in 2011, but he rejected them several times.9

In the Glostrup case, Abdul Basit Abu-Lifa, a 17-year-old friend of Basil Hassan, received a seven-year sentence for planning terrorism. The Glostrup case was connected to a group of Islamist extremists in Bosnia, which included several people from Scandinavia. One of them was a young Turkish man called Abdulkadir Cesur, who had befriended Hassan while living in Denmark. Cesur was arrested in Bosnia in October 2005 and in 2007 received a 13-year sentence for traveling “to Sarajevo to carry out a terrorist attack on the territory of Bosnia or another European country.”10 The sentence was later reduced to six years and four months.11 Danish investigators believe that years later, Cesur played a key role in Hassan’s Islamic State drone procurement network.12

While some of his friends went to prison for terrorism, Hassan got into engineering school. He was technically adept and loved gadgets, and people close to him in his teenage years recount how he tried to hack other people’s computer systems. He was also security conscious, taping over his laptop camera and avoiding speaking near telephones.13

In 2010, Basil Hassan received his engineering degree from the Technical University of Denmark, but he wanted to learn other skills. Among other things, he started training to become a pilot. The Danish intelligence agency PET believes that the skills Hassan was acquiring later helped propel him into his role for the Islamic State.14

Linking Up with the Islamic State

After the February 2013 assassination attempt, Basil Hassan fled by train to Germany and then took a flight to Turkey. In the years that followed, he alternately stayed there, in Lebanon, and in Syria.15

It is not clear how or when Hassan was recruited into the Islamic State, but five of the individuals convicted for their role in the Glostrup-Sarajevo network are believed to have become closely involved with the group. Danish investigators believe this helped pave the way for Hassan to join the group. The risk he took in attempting to kill Hedegaard likely not only gave him a certain cachet among jihadis but could have contributed to him being trusted by the Islamic State as well as helped him into a senior operational position.

Hassan had kept in touch with the Sarajevo terrorist plotter Cesur since 2010 and visited him in prison in Bosnia, and when Cesur was released early and moved to Turkey, their friendship continued. While Basil Hassan was being hunted by the Danish police, he stayed with Cesur in Turkey, among other places. The Danish intelligence services believe they can link Cesur to the Islamic State through the terrorist organization’s internal documents that were found in the possession of Hassan’s Danish terrorist network. Some of these documents were discovered on a USB flash drive and others on several hard drives.16

Another of Hassan’s friends from the Glostrup-Sarajevo case, Abu Lifa, joined the Islamic State after being released from prison in 2010, according to Danish authorities.17 c

According to Bosnian authorities, two Bosnians who were convicted for their role in the Sarajevo group—Bajro Ikanovic18 and Senad Hasanovic—went to Syria in 2013,19 and there are many photos online of the two posing with weapons alongside the Islamic State.20 The Atlantic reported that prior to his death in the spring of 2016, Ikanovic was the leader of the biggest Islamic State military training camp in northern Syria.21 He is also believed to have been close to the Georgian Islamic State senior leader Omar al-Shishani.22

Mirsad Bektasevic, a Swedish national who was convicted for his role in the Sarajevo group, also developed ties to the Islamic State. In 2017, he was convicted in Greece of having joined the Islamic State and intending to go to Syria with weapons.23

The Spreadsheet of Drone Purchases

Within months of Hassan becoming a suspect, Danish police began monitoring Basil Hassan’s travel pattern in the Middle East, his bank accounts, and his friends in Denmark. In the fall of 2013, the police were alerted when Hassan purchased numerous parts for model planes and gadgets for simple drones through various Danish and non-Danish websites. Investigations eventually established that Hassan was the one setting up the network and pulling the strings. He had the equipment delivered to various Danish addresses, and then his friends went to the post office and sent it on to Basil Hassan in Turkey or Lebanon, often packed with chocolate, children’s clothes, or potato chips.24 According to court documents filed by Danish prosecutors, Basil Hassan made sure the equipment ended up with the Islamic State.25 At the time, police were not sure of the intended purpose of the equipment. Only later did it become apparent that he was making purchases for what would evolve into the Islamic State’s drone program.26

The purchases were meticulously recorded in an electronic spreadsheet that the Danish investigators believe was created by Hassan and named “Expenses and tracking”—a document that the Danish police later found during an April 2014 search in Copenhagen targeted against what would later turn out to be accomplices in Hassan’s drone network. In the document, Basil Hassan had recorded the parcel tracking numbers, purchase invoices, and prices of the drone parts, and the accounts show that Hassan from the fall of 2013 until his arrest in the spring of 2014 was responsible for purchasing model plane parts amounting to more than $120,000.27 d

According to testimony provided by military drone experts at the 2019 trial, the purchases show that Basil Hassan and the people around him were experimenting with and developing an advanced and professional drone program. They were buying individual parts for building drones such as remote controls, propellers, current regulators, and speed controllers.28

According to the analysis of Danish investigators, the accounts tie Basil Hassan directly to the Islamic State (or the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, as it was then known) at a very early stage—in the fall of 2013. The spreadsheet states that the accounts belong to “Katibet al baraa bin malik,” which several intelligence services have established was the Islamic State brigade in charge of developing drones and chemical weapons. Furthermore, Hassan’s jihadi kunya (fighting name) Abu Hani al-Lubnani is noted in the account documents.29

The Islamic State Drone Footage

In the winter of 2013/2014, Basil Hassan was busy communicating with his network in Denmark through various channels. He communicated via Skype, a designated burner phone bought in Denmark, and draft emails. The email accounts were created in the names of fictitious individuals such as “Peter Sam” and “Peter Roses.”30 To communicate with his network, Hassan created draft emails in the accounts, having shared log-in and password details with his accomplices.31 The network’s communication was documented during the October to December 2019 trial of Hassan’s drone procurement accomplices in Denmark, which, as already noted, resulted in the conviction of three individuals for procuring equipment for the Islamic State.32 e

The trial also documented that in December 2013, Hassan got two of his subsequently convicted friends in Denmark to buy GoPro cameras. Years later, as will be outlined later in the piece, Danish investigators, working in collaboration with the FBI, established that at least one camera bought by Hassan’s Danish terrorism network was used to record footage published by the Islamic State in its film documenting its August 7, 2014, attack on the Syrian regime military base in Ain Issa.33 The footage consists of an overhead video view of what is the Ain Issa base according to the trial testimony of an official from Denmark’s military intelligence service. The trial established that it was a reconnaissance flight before the attack.34

During the April 2014 search in Copenhagen targeting Hassan’s friends, one of the videos that was found showed what the police believe to be a known Danish Islamic State fighter operating a reconnaissance drone near the Ain Issa base. The video included raw aerial footage that matches footage from a 13-minute long propaganda video published by the Islamic State in connection with the Ain Issa attack.35

The propaganda video the group posted shows a group of Islamic State members sitting on the ground, studying a large map. They can be seen pointing at it and seem to be planning how to carry out an attack in a certain area. The video the Islamic State posted cuts to drone footage of the Ain Issa military base found during the search in Denmark. Onscreen it says, “from the lens of a drone belonging to the Islamic State’s army.” It then shows a man in an armored vehicle filled with explosives. Several vehicles approach in the cover of darkness, and suddenly there is a huge flash of light from three suicide bombers’ explosions followed by Islamic State fighters on the ground attacking with automatic weapons. In another scene, Syrian regime soldiers with their hands tied behind their backs are shot at close range.

With the help of the FBI, the Danish police traced some of the drone footage found in the USB flash drive found in Denmark to a specific GoPro camera, in part through the serial number from the American manufacturer, and sales tracking and invoices belonging to this particular camera show that it was sold in Denmark in December 2013. The court in Denmark was satisfied that the camera was bought by individuals in Basil Hassan’s network.36

There is one piece of evidence that suggests the possibility Hassan himself spent time in the Ain Issa area months before the attack. In the spreadsheet recovered in the April 2014 search in Copenhagen recording spending on drone parts and other items by the Islamic State brigade “Katibet al baraa bin malik,” Danish police found an item of spending that stated: “petrol 10-50 liters, two months of pay, petrol car Abu Hani Ain Issa, January 2014.” As mentioned earlier, Abu Hani is Basil Hassan’s jihadi fighting name.37

Further Information From the USB Flash Drive

While the Danish police in the spring of 2014 were hot on the trail of Basil Hassan, whom they secretly suspected of being behind the assassination attempt on Islam critic Lars Hedegaard, they started collaborating with the Turkish police. On April 25, 2014, Basil Hassan was arrested in Turkey.f Despite the security consciousness he had previously exhibited, Hassan carelessly arranged a meeting with his parents who were to visit him in Turkey, and when Hassan arrived at Istanbul’s Atatürk airport to pick up his parents, he was arrested by the Turkish police.38

This was a significant breakthrough for the Danish police, who announced to Hedegaard and the Danish public that they had identified a suspect and that he was behind bars abroad.39 While Danish authorities awaited a simple and routine extradition from Turkey, the Danish police could proceed more assertively with their investigation now that it was no longer confidential. Accordingly, police searched several addresses belonging to Hassan’s friends and acquaintances, and several figures from militant Islamist circles in Copenhagen received a visit from the police.40 It was during these searches that Danish police retrieved both the drone procurement network’s spreadsheet “Expenses and tracking” and the drone footage that matched the Islamic State’ film documenting the Ain Issa attack.41

Among the addresses searched in April 2014 were two belonging to Hassan’s friends, Fady Mohammed and Coskun Simsir, who were both subsequently convicted in December 2019 of having sent drone equipment to the Islamic State.42

At the time of the searches, Mohammed was a newly graduated engineer in his mid-20s and a well-known figure in Islamist circles in Denmark, well-spoken, educated and with a large circle of acquaintances that included several Danish jihadi fighters in Syria and convicted terrorists.43

Neither Fady Mohammed nor Coskun Simsir was arrested after the searches in 2014. It was not until September 26, 2018—four years later—that Danish police arrested them and charged them with sending drone equipment to the Islamic State.44 During the trial, Mohammed testified that he met Hassan in engineering school and they became close friends; and so it was perfectly natural for Mohammed to help Hassan with various things in 2013. For example, Mohammad let Hassan use his Copenhagen address to get social benefits, even though Hassan had not been in the country since the assassination attempt early that year on Hedegaard.45

Both Mohammed and Hassan were acquaintances of Abdulkadir Cesur, the Turkish terrorist plotter who spent several years in prison in Bosnia. Mohammed testified during his 2019 trial that in 2013 and 2014, he had regularly met with Cesur in Turkey because Cesur was helping Mohammed’s family buy an apartment under warmer skies than cold Denmark.46

Mohammed landed back in Denmark from one of those trips to see Cesur in Turkey, just days before his residence was searched by plain-clothes officers in April 2014. In his wallet, Fady Mohammed had the aforementioned USB flash drive that the police seized and spent years examining and analyzing and that also contained Ain Issa drone footage and the “Expenses and Tracking” drone purchase spreadsheet. After several failed attempts, the forensic team managed to recover 2,400 documents from the USB flash drive, of which several were shown on a large screen during the trial of the Danish terror network in late 2019.47

The USB flash drive was a treasure trove for the Danish intelligence services. Among other things, it contained several photos of a man believed by the police to be Basil Hassan. The series of images shows the man wearing blue gloves making a simple bomb, step by step. In the images, the bomb maker is wearing a special watch on his right arm. Hassan’s Lebanese ex-wife testified to the Danish police that Hassan had a similar wristwatch.48 Furthermore, the police forensic team examined the sequence by comparing a tabletop seen on the photos with a tabletop seen in a picture of Basil Hassan’s public services login cardg also found on the USB flash drive. They concluded that in all probability, the tabletops were the same. The police also had experts compare the arm and veins from the man on the bomb-making photos with Hassan’s arm and veins as seen on private photos from his high school days and a photo of Hassan taking a bath. Their conclusion was that nothing ruled out that the arm and the veins belong to the same person.49

The bomb-making photo sequence matched internal Islamic State material that the Danish security and intelligence service PET obtained through a foreign collaborator in late summer 2019. In the Islamic State materials provided by the collaborator, the bomb-making photos appear in the form of a bomb recipe. This led Danish intelligence services to believe that Basil Hassan was one of the people used by the Islamic State to show how to make explosives. It was not until years after finding the USB flash drive that the Danish police learned that the man on the video was Basil Hassan.50

When Fady Mohammed’s house was searched in April 2014, uncovering the USB flash drive among other things, he told the police that the USB flash drive belonged to him. He changed his explanation during his trial in 2019 claiming that he had received the USB flash drive from Cesur, who in turn got it from Hassan. Mohammed also claimed that the USB flash drive was intended for a fourth man in Denmark.51

In October 2014, Danish authorities were busy investigating Hassan’s network when they learned that Turkish authorities, without informing them, had decided to release Hassan from custody. Denmark immediately sent representatives from the Ministry of Justice and the PET to Ankara, but failed to get an answer from Turkey as to why Basil Hassan was no longer detained, even though Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt was also disgruntled and called the case totally unacceptable.52 It has since come to light that Hassan was one of Islamic State jihadis who were part of a prisoner exchange in September 2014 between Turkey and the Islamic State.h Turkey has never officially commented on the controversial exchange.i

Building Up the Islamic State’s Drone Program

What happened to Basil Hassan after the prisoner exchange only came to light years later as part of a jigsaw puzzle of information from the police investigation that was made public bit by bit during the trial of Hassan’s drone procurement accomplices in Denmark in late 2019 as well as the authors’ own two-year-long investigative reporting and their interviews with a significant number of sources in Islamist circles and intelligence services in Denmark and other parts of the world, including the Middle East.53

Danish intelligence services subsequently established that Hassan quickly rose through the ranks of the Islamic State in the fall of 2014 and that he also became much more security conscious, which was understandable given the error that had led to his arrest in Turkey.54 According to a foreign fighter from Bangladesh who testified in the Copenhagen trial of Hassan’s drone procurement accomplices in late 2019, Hassan made sure after the prisoner exchange never to talk directly with friends or other connections in Europe.55 Still, the United States kept tabs on what Hassan’s role was in Raqqa, Syria, and in late 2016 designated Hassan a global terrorist.56 Jason Blazakis, the director of the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Counterterrorism at the time of the designation, has since said that Basil Hassan was added to the list because he played a vital part in developing the Islamic State’s drone program and that he was authorized by the group’s top leaders to develop the technology. “Basil Hassan is one of the most dangerous people we have ever added to the terrorism list. We added him because of his role in ISIS’s drone program and his extensive European network,” Blazakis explained.57

This is corroborated by information the authors received in 2018 in Kobane, Syria, when they met with a high-ranking Kurdish intelligence official. The official said that the Kurdish forces had been monitoring the Islamic State’s use of drones for several years, and in Raqqa alone, after liberating the city, had collected more than 200 drones used by the Islamic State. The intelligence officer showed the authors examples of collected drones, some of which were homemade models made from Styrofoam with a cut-out hole for a bomb. Just such a drone was found in one of the warehouses in Raqqa where, according to the Kurdish intelligence official, Hassan in all probability had been, and the intelligence official said the Kurdish forces had information that Hassan was in charge of training new drone pilots, of keeping the group updated on drone technology, and that he also played a significant role in the logistics/transport system that brought the drones into Raqqa. The intelligence official also told the authors that Hassan was on the list of Islamic State fighters who were priority targets for the coalition when it launched its campaign on Raqqa.58

The court proceedings against Basil Hassan’s Danish network provided significant insight into the development of the Islamic State’s drone program. Basil Hassan’s purchases of model planes and drone parts in 2013 may have seemed hobby-like and experimental, but in later years, the Islamic State’s drone army was filled with advanced, professional, and expensive equipment.59

Despite the April 2014 searches targeting Basil Hassan’s friends/drone procurement accomplices, Hassan continued to source drone components from Denmark as he worked to develop the Islamic State’s drone program.60 j Umut Olgun, a Copenhagen Uber driver who was one of the three men convicted in the 2019 trial of Hassan’s accomplices, worked with Hassan to supply the Islamic State drone components between 2016 and his arrest in September 2017. Police had begun monitoring Olgun in 2016 because of source information. In the months that followed, the police and PET would have a front-row seat to his drone purchases. The police wiretapped his Uber car and his apartment and secured the cooperation of two salespeople in a Copenhagen drone store at which Olgun came to buy drone parts. Investigators were therefore able to document that Olgun bought drone computers and other components in the amount of around USD $30,000, and the court in Copenhagen was satisfied that the parts were intended for Hassan and the Islamic State through a middleman in Turkey, the aforementioned Abdulkadir Cesur.61

Voice recordings back and forth between Olgun and Cesur were among the evidence introduced during the trial. The trial revealed how Danish investigators were able to pick this up despite the fact that Olgun and Cesur were using the encrypted messaging app Telegram. This was because Olgun recorded the audio messages in his car and residence, which had been bugged by Danish investigators. He also played out loud the audio messages he received via Telegram from Cesur, allowing those audio messages to be picked up as well.62

provided to the authors

Hassan and Cesur were not on trial in Denmark.63 After serving his sentence for terrorism in Bosnia and moving to Turkey, Cesur has been banned from entering Denmark and has been the subject of an international arrest warrant since Olgun’s arrest. In the winter of 2018/2019, the authors managed to track down Cesur in a small Turkish town. One of the authors, having identified themselves as a journalist for DR, recorded their conversation with him using a concealed camera.64 During the conversation, Cesur revealed that he was a close friend of Basil Hassan and that he had been helping him while he was on the run after the assassination attempt in Denmark. When asked about his involvement in smuggling drones into the Islamic State in Syria, he merely concluded that he did not understand why he would use couriers from Denmark when he could simply buy drones in Turkey. He also admitted to knowing two of the three people convicted in 2019 for being part of the Danish drone terror network.65 k

Basil Hassan’s Life Within the Islamic State

The DR reporting team were able to develop a clearer picture of the role Hassan played for the Islamic State by interviewing women who had met and lived with him in the caliphate. One is Layla Talou, who was one of thousands of Yazidi women and children captured by the Islamic State when the group stormed the northern Iraqi town and region of Sinjar in August 2014. The terrorist group killed Talou’s husband and abducted her and her two young children to the Iraqi town of Tal Afar. For two years, she lived as a hostage and was sold as a slave to Iraqi and Saudi Islamic State men who regularly beat and raped her.66

By her own account, Talou was bought and sold eight times before her family succeeded in purchasing her freedom from slavery in January 2017. The family paid more than USD $7,000 to a Saudi Islamic State member in a transaction kept secret from the rest of the terrorist group, and as a result the Islamic State court signed a document ending her status as a slave. She was not free to leave Islamic State territory, however.67

Talou told one of the authors that she had a secret agenda: If she could fool the Islamic State into thinking she was a good ‘Muslim’ by converting and marrying an Islamic State fighter, she might be able to escape one day. In a living room in Raqqa, Talou waited to meet the man who had been selected for her. A man with shoulder-length hair entered and introduced himself by his warrior name Abu Hani al-Lubnani. Layla Talou did not learn his real name was Basil Hassan until after her escape, when she was interrogated by U.S. soldiers.68

The wedding was held at the special sharia court in Raqqa, and Basil Hassan was ordered to pay a dowry of one dinar in the Islamic State’s own currency for his new bride. Once they were married, Talou moved into a corner apartment in Raqqa’s Bedouin district with her two children, her sister-in-law, and new husband.69 At the time, she did not know that Basil Hassan was wanted by the United States, who considered him extremely dangerous.70

Special rules applied in Basil Hassan’s home, and Talou was quick to learn them. At first, Hassan denied her a cellphone, and when he came home, he rang the doorbell twice. That was the code allowing Talou to unlock the front door. There were also rules for how Talou was to answer a call to the apartment’s landline phone. “This was normal procedure among ISIS people. The person at the other end would then give me a message, and then I pressed the button again to indicate that I understood, and then the call ended,” Talou told one of the authors.71

Hassan allowed her a modicum of liberty—for example, letting her sit, veiled, behind him on his motorbike when they went shopping. She was also allowed to leave the home alone to shop at a small store nearby. But if she rejected Basil Hassan in bed, he forced himself on her. “When I didn’t want him to touch me, he didn’t accept it. He told me I couldn’t reject him because I was his wife,” Talou told one of the authors.72

Hassan was influential in the Islamic State, and according to several individuals who met him in the caliphate and were interviewed by the authors, he regularly wore a suicide belt and communicated on a scratchy radio, the Islamic State’s internal radio communication. Talou also says that Hassan told her that the white drone in his bag was used to provide aerial footage of suicide bombings carried out by the Islamic State. Talou said her relationship with Hassan was different to when she had been kept as a slave. He accepted her children living with them and told them that the children were not supposed to play with the drone he kept in the living room. After a bit more than a month living with Hassan in Raqqa, Talou said she managed to escape through a secret network helping Yazidi women get out of Islamic State hands, while Hassan was busy at the frontline. During their time together in Raqqa, Hassan had told her that he had been arrested by the Turkish police and later released as part of a prisoner swap.73

Talou’s depiction of Hassan is corroborated by two other women that the authors located and interviewed. One of them, a Moroccan woman by the name of Islam Mitat, traveled to the Islamic State in the spring of 2015 and married Faisal Sahib, an Australian Islamic State fighter. Two years later, Mitat fled from the terrorist organization. She told one of the authors that during her time with the group, she met Basil Hassan, who her husband told her made bombs and was wanted by the Americans.74

The other woman, a Yazidi by the name of Nidal Ali Ismael, was only 16 when she was captured by the Islamic State. She told one of the authorsl that upon Hassan’s release in Turkey and return to Syria, he took her as his slave, and for two years she traveled around with him in large parts of the Islamic State’s territory, in towns such as Deir ez-Zor, Aleppo, and Raqqa as well as Tal Afar and Mosul in Iraq. In many of the places, Nidal Ali Ismael had to help Hassan attach explosives to model planes and drones, she said. “Abu Hani made explosive charges and bombs for use against the enemy,” she said.75

According to Layla Talou, when Basil Hassan spoke on the phone or held meetings at the apartment in Raqqa, he spoke English primarily, but on two occasions, she overheard conversations in Arabic, which she was better able to follow.

“He spoke to someone on the landline phone. They were planning to send someone to another country to carry out an attack, but I didn’t know which country. I got the feeling that it was in Europe or another place in the West,” Talou told one of the authors.76

Her suspicion that Basil Hassan was planning attacks in the West was correct.77

Controlling the 2017 Sydney Plane Plot

Around the time Layla Talou managed to escape from the Islamic State in 2017, Basil Hassan was busy planning such an attack in the West. Several intelligence sources told the authors that Basil Hassan was part of a group in Raqqa who in 2016 and 2017 tested aviation security in several countries. From Raqqa, Basil Hassan and others had parcels airmailed from Turkey and the Maldives among other countries. The group was testing aviation security vulnerabilities. Basil Hassan collaborated on airmailing test parcels to Qatar, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States, among other countries.78

This set the stage for a 2017 plot to blow up a passenger aircraft leaving from Sydney international airport in Australia that Basil Hassan and his group came close to carrying out.79 A detailed description of the plot was presented at the trial against Australian brothers Khaled and Mahmoud Khayat who in December 2019 were sentenced to 40 and 36 years of prison, respectively, for the failed terrorism attack.80 In April 2020, CTC Sentinel published an article by Andrew Zammit outlining in detail Basil Hassan’s role orchestrating the terrorist plot, which drew on these court documents and the authors’ DR reporting.81 Sources made clear to DR that Basil Hassan was the Islamic State operative described by Australian authorities as “the Controller” in the plot.82 During the course of the plot, he provided guidance and instructions via the Telegram messaging app to the Khayat brothers in Sydney.83 They had been connected to Hassan by a third brother, Tarek Khayat, who had joined the Islamic State and, like Hassan, was based in Raqqa, Syria.84

In April 2017, Basil Hassan’s Islamic State group airmailed a parcel from Turkey by DHL to Australia that contained an almost-functioning bomb requiring final assembly. As Zammit noted, “Completing construction of the bomb nonetheless required close tutelage. On April 22, 2017, Basil Hassan sent Khaled Khayat an audio message through Telegram with instructions for how to wire the bomb.”85

The group planned to place the bomb in a meat grinder, pack the grinder in a bag, and get the bag aboard a flight from Sydney to Abu Dhabi.86 A fourth Khayat brother, who had no knowledge of the plot, was booked on a flight to Abu Dhabi on July 15, 2017, offering the group an opportunity to get the explosives onboard by giving him luggage as gifts to take to family members. As outlined by Zammit, “On July 14, 2017, the day before the planned flight, Basil Hassan advised Khaled on how to set the timer to ensure that the bomb would explode mid-flight. Hassan instructed Khaled to write down the calculations and to send a picture of his work.”87

The trial established that a commonplace incident at Sydney airport on July 15, 2017, foiled the attempt. Without the traveling brother’s knowledge, his hand luggage now contained the bomb. But when he checked in, a passenger service agent said the carry-on bags would weigh too much and, as outlined by Zammit, “that he would have to either pay to check in some of these bags as cabin baggage or would need to repack his hand luggage.”88

Worried that the exchange with the passenger service agent had increased the risk of the device being discovered, the plotters took the device out of their brother’s hand luggage and disassembled the bomb at home.89 According to the authors’ information, the Danish intelligence services believe the exceeding of the weight limit was a stroke of luck.

The trial established that the Australian brothers were also planning a poison gas attack inside Australia and that they intensified efforts after they aborted the passenger plane plot. As outlined by Zammit, “On July 24, 2017, Hassan sent instructions to prepare and test the gas within a week. He also provided instructions on how much of the gas would be needed to create a lethal effect in the sorts of public spaces where they were planning to use it.” On July 27, 2017, Hassan made clear to the Sydney plotters that the poison gas plot was the top priority.90

However, the poison gas attack plot failed, because 11 days after the flight from Sydney bound for Abu Dhabi, Australia was warned by a foreign intelligence service. Three days later, on July 29, 2017, the two brothers in Sydney were arrested.91 According to several of the authors’ sources inside and outside Denmark, it was in part intelligence from the Danish Defence Intelligence Service (FE) that led to the Australian arrests.

Nevertheless, the terrorist conspiracy was one of the most ambitious and innovative terrorist plots ever seen.92 The emphasis Hassan placed on operational security doubtlessly contributed to the plot not being detected until after the aborted attempt to get the bomb on the plane. According to Zammit, Hassan’s “direct provision of materials over a long distance, combined with the instructions necessary to use them, represented a key innovation in Islamic State cybercoaching.”93 His role orchestrating the plot also underlined how dangerous one single capable international attack planner can be, and had similarities to the coordination the Pakistan-based British al-Qa`ida operative Rashid Rauf provided to U.K.-based plotters in al-Qa`ida’s 2006 transatlantic airline plot.94 Danish terrorism studies scholar Tore Hamming observed that “The Sydney aviation plot … illustrates the role of Basil Hassan. Hassan can to some extent be labelled the Khalid Sheikh Muhammad of the Islamic State due to his alleged role in ExOps and his ambition to innovate.”95

After the sentencing of the Khayat brothers, court documents were released that suggested Basil Hassan might have played a role in a terrorist attack in Egypt that killed 224 passengers on an airplane. In October 2015, Russian Metrojet 9268 took off from Sharm el-Sheik but exploded over the Sinai desert. The Islamic State claimed it placed an IED inside a soda can, which detonated mid-air.96

Police notes paraphrasing Khaled Khayat’s comments during a police interrogation after his arrest stated that he claimed, “there was a plane blown up over Egypt” and that “it was done by these same people offshore, using the same methodology.”97

Based on interviews with intelligence sources, in November 2019 the authors reported that investigators believed that Khaled Khayat appeared to be referring to Basil Hassan and his own brother (Tarek Khayat, the Islamic State operative in Raqqa, Syria).m After this was reported, other intelligence sources who spoke to the authors disputed this interpretation. One intelligence source told the authors that the investigation so far into the Metrojet bombing has not found any evidence that Basil Hassan was linked to the attack.98

Dead or Alive?

In the summer of 2017, one of Basil Hassan’s closest relatives in Denmark got a text message saying that Hassan was dead. The messenger was a Dutch-African woman by the name of Umm Baraa, who voluntarily went to Syria around 2014. In Mosul, Umm Baraa married Hassan, and in the spring of 2017, she gave birth to their daughter.99

Umm Baraa and her two-year-old daughter arrived at the Al-Hol camp in 2019, having been among the very last Islamic State sympathizers to surrender at the group’s last stronghold in eastern Syria. A member of the DR reporting team met with her in Al-Hol, and she insisted that Hassan was dead. “I was told of his death by text message but also by someone in person.” According to Umm Baraa, Basil Hassan had left Raqqa with her when the war against the Islamic State neared the town. According to her account, the couple then went to the town of Mayadeen in the province of Deir ez-Zor in eastern Syria, but Hassan later went back to Raqqa and then Umm Baraa was told that he had been killed in Raqqa. “I have heard that some people don’t believe he is dead. But I am sure of it and I don’t understand why anyone would doubt it. He died on July 9 or 10, 2017.”100

This timing appears to contradict information introduced at the trial of the 2017 Sydney plane plotters. As already outlined, the “Controller” (who the authors’ reporting has established was Hassan) was still communicating with the Sydney-based plotters until very shortly before their arrest on July 29, 2017, sending one communication to the plotters in Australia, for example, on July 27, 2017.

However, in August 2017, a report in the Lebanese media outlet al-Diyar pointed to Hassan being killed in different circumstances. The outlet reported that an Islamic State commander by the name of “Basil H.H.,” nicknamed al-Danmarki (the Dane) because of his Danish nationality, had been killed in the vicinity of the Lebanese town of Aarsal, near the border with Syria on August 21, 2017.101

The death of Basil Hassan has never been officially confirmed.

“We are in a situation today where we can’t confirm it with 100% accuracy. We can’t rule out that he hasn’t been tempted to play dead,” Lars Findsen, the director of Denmark’s Defence Intelligence Service, said in 2017.102

Danish counterterrorism officials are still not certain that he is dead.103 CTC

Mette Mayli Albæk is a journalist and crime analyst at the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR) who has focused on several Danish terror cases. She is the author of the book The Terrorist from Nørrebro about Omar Hussein who carried out a terror attack in Denmark in 2015. Follow @mettealbaek

Puk Damsgård is DR’s Middle East correspondent and the award-winning author of several bestsellers about Syria, the war against the Islamic State, and the book The ISIS Hostage for which she received the prestigious Cavling Award. Follow @pukdamsgaard

Mahmoud Shiekh Ibrahim is a researcher and producer in the Middle East.

Troels Kingo is a former investigative journalist at DR having worked on documentaries about terrorism financing. He is currently the editor for non-fiction at the publishing house People’s Press. Follow @TroelsKingo

Jens Vithner is currently editor of the radio documentary department at DR. He was previously the editor at a leading Danish fact-checking program and an investigative journalist having reported on various stories, including Vietnamese “skunk” mafias. Follow @vithner

Substantive Notes

[a] The police found a dark blue Volkswagen Transporter close to Hedegaard’s house. They did not find it interesting at first because it was registered in a woman’s name. But six weeks after the assassination attempt, the car was still parked on Hedegaard’s street. The police discovered that it was sold three days prior to the attack to a man who signed the contract with a fake address and the fake name of a well-known Palestinian terrorist. Information from the sale of the car led the police to suspect that Basil Hassan was behind the attack. Lotte Scharff, “Sådan kom politiet på sporet af Hedegaards attentatmand,” B.T., April 27, 2014.

[b] All three of those convicted denied guilt. They claimed in court that they did not know that the equipment they bought was supposed to end up with the Islamic State. Trial Information.

[c] The authors were not able to find reliable information on Abu Lifa’s current status or whereabouts.

[d] Basil Hassan’s network was one just of several drone supply networks providing the Islamic State with drone components. Another network was centered around Siful Sujan, a Bangladeshi Islamic State operative who had previously been based in Wales and was killed in a drone strike near Raqqa, Syria, in late 2015. The authors have not been able to conclusively link the two networks. For more on the Sujan network, see Don Rassler, The Islamic State and Drones: Supply, Scale, and Future Threats (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2018).

[e] In total, around 18,000 pages of evidence was shared by prosecutors with the defense during the trial. The authors attended the trial, took notes, and obtained hundreds of pages of trial transcripts.

[f] Danish investigators believe that Hassan spent time in Syria before his arrest in Turkey. Niels Brandt Petersen, “Mistænkt for drabsforsøg rejste ud af landet på gerningsdag,” Berlingske, April 27, 2014.

[g] Most Danes have a personal public log-in card to access their public records.

[h] The hostages—46 Turks and three Iraqis—were seized during the Islamic State takeover of Mosul, Iraq, in June 2014. On September 20, 2014, they returned to Turkey with many questions unanswered about what led to their release. “There are things we cannot talk about. To run the state is not like running a grocery store. We have to protect sensitive issues, if you don’t there would be a price to pay,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was quoted telling some of the released hostages and their families. One report stated the number of fighters freed by Turkey in the exchange was as high as 180. “Turkey remains cagey about hostages freed by ISIS,” CBS News, September 21, 2014; John Simpson and Alex Christie-Miller, “UK jihadists were traded by Turkey for hostages,” Times, October 6, 2014; “UK jihadist prisoner swap reports ‘credible,’” BBC, October 6, 2014.

[i] According to the U.S. government, “After being arrested in Turkey in 2014, [Hassan] was released as part of an alleged exchange for 49 hostages held by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).” See “State Department Terrorist Designations of Abdullah Ahmed al-Meshedani, Basil Hassan, and Abdelilah Himich,” U.S. Department of State, November 22, 2016. Additionally, the interesting following details were reported in a monthly newspaper produced by Iraq’s Supreme Judicial Council. According to testimony shared by Moroccan Islamic State member Abu Mansour, who was involved in the September 2014 prisoner exchange between the Islamic State and Turkey, a Danish-Lebanese individual called Abu Hani (which as has been noted was the jihadi fighting name of Basil Hassan) was among the Islamic State members the organization wanted released from Turkish prisons. Abu Mansour was quoted telling Iraqi authorities, “The exchanges took place by handing over the Turkish consul and diplomats in exchange for the release of 450 members of the organization who were detained by the Turkish authorities. The most prominent of those released was Abu Hani, a Danish [man] of Lebanese origin, who is in charge of the Manufacturing and Development Committee and others.” Haidar Zuwayir, “Irhabi Maghribi li ‘al-Qadaa’: Sa’aina li-Jalib al-Aslihah al-Kimyaiyyah min Korea al-Shimaliyyah”(A Moroccan Terrorist to ‘al-Qadaa’: We sought to acquire chemical weapons from North Korea), al-Qadaa, Issue 34, August 2018.

[j] The involvement of the two friends who initially helped Hassan—Fady Mohammed and Coskun Simsir—seemed to stop when their homes were searched in April 2014.

[k] Cesur will probably never be put on trial in Denmark because he is a Turkish national and as such cannot be extradited from Turkey.

[l] She spoke from Canada in a phone interview. Canada granted her and her family asylum in 2017 after she escaped from the Islamic State. The interview was made with translation help from her father because Nidal has an epileptic condition that causes her to have speech and sensory difficulties.

[m] As already noted, Tarek Khayat had connected his two Sydney-based brothers Khaled and Mahmoud Khayat to Hassan. For more on Tarek Khayat’s role in the 2017 Sydney airline plot, see Andrew Zammit, “New Developments in the Islamic State’s External Operations: The 2017 Sydney Plane Plot,” CTC Sentinel 10:9 (2017) and Andrew Zammit, “Operation Silves: Inside the 2017 Islamic State Sydney Plane Plot,” CTC Sentinel 13:4 (2020).

Citations

[1] Theis Lange Olsen, “OVERBLIK Sådan forløb attentatforsøget mod Lars Hedegaard,” DR, April 27, 2014.

[2] For an authoritative account, see Andrew Zammit, “Operation Silves: Inside the 2017 Islamic State Sydney Plane Plot,” CTC Sentinel 13:4 (2020).

[3] A 16-episode DR podcast series on Basil Hassan’s drone network, which aired between April and December 2019, can be found at https://www.dr.dk/radio/p1/dronekrigeren

[4] Much of information in this article is drawn from two documentaries and a series of news reports by the Danish public broadcaster DR in late 2019. These are individually cited throughout the article. In general, the authors only provide other materials (for example, trial testimony or the authors’ interviews) for information not fully presented in these DR reports. DR’s comprehensive coverage of Basil Hassan and his drone network can be found at https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/tema/drone-sagen

[5] “Hvem er den danske topterrorist Basil Hassan?” DR.

[6] Ibid.

[8] “Military Operations in Iraq and Syria,” U.S. Department of Defense briefing, December 29, 2015, from timecode 07:50.

[9] Morten Skjoldager and Bo Maltesen, “PET kendte til mistænkt i Lars Hedegaard-sagen,” Politiken, May 3, 2014; authors’ information from sources.

[10] Maja Zuvela, “Three jailed in Bosnia for planning suicide attack,” Reuters, January 21, 2007.

[11] “Terrordømt danskers fængselsstraf halveret,” DR, June 18, 2007.

[12] Trial of Fady Mohammad, Coskun Simsir, and Umut Olgun in the Copenhagen Court, October 2019 to December 2019. This is subsequently cited as “Trial information.”

[13] “Hvem er Den Danske Topterrorist Basil Hassan?”

[14] Ibid.

[15] Authors’ information from sources.

[16] Trial information.

[17] Thomas Klose Jensen, “Terrordømt dansker kæmper for Islamisk Stat,” DR, November 19, 2014.

[18] For more on Ikanovic in this publication, see Timothy Holman, “Foreign Fighters from the Western Balkans in Syria,” CTC Sentinel 7:6 (2014).

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ikanovic’s role in the Islamic State is described in Seamus Hughes and Bennett Clifford, “First he became an American – Then he joined ISIS,” Atlantic, May 25, 2017.

[22] The relationship between Ikanovic and al-Shishani is described in “U Siriji poginuo Midhat Duno Mitke is Hadzica,” saft.ba, June 2, 2014.

[23] Anthee Carassava, “Jihadist terror plotter held in Greece,” Times, February 1, 2016.

[24] Trial information.

[25] Trial information.

[26] Trial information.

[27] Trial information.

[28] Trial Information and podcast episode 10-12.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Trial Information.

[33] The attack on the Ain Issa base was documented in these news reports and articles: “‘The Islamic State’ Takes Over the Headquarter of the Syrian 93rd Brigade in Raqqah,” BBC Arabic, August 8, 2015; Jeffrey White, “Military Implications of the Syrian Regime’s Defeat in Raqqa,” Washington Institute PolicyWatch 2310, August 27, 2014; “Kidnapped by ISIS: Failure to Uncover the Fate of Syria’s Missing,” Human Rights Watch, February 11, 2020.

[34] Trial information.

[35] Trial information. The matching footage can be seen at timecode 1:54 in the Islamic State video on the Ain Issa attack. “Disperse Those Who Are Behind Them,” the Islamic State’s al-I’tisam Foundation for Media Production, August 13, 2014. A Channel 4 news report about the Islamic State’s Ain Issa attack video shows a screen grab of the aerial view drone footage of the Ain Issa base in question. See David Doyle, “Islamic State video shows Assad army base massacre,” Channel 4, September 9, 2014.

[36] Trial information.

[37] Trial information.

[38] Sune Gudmann Christiani, “Lars Hedegaard ser nu frem til udlevering af mistænkt,” DR, May 22, 2014.

[40] Jens Arvid Spærhage Hansen and Jonas H. Bruun, “Politiet: Vi har anholdt Hedegaards formodede attentatmand,” Jyllands-Posten, April 27, 2014.

[41] Trial information.

[42] Trial information.

[43] Trial information.

[45] Trial information.

[46] Trial information.

[47] Trial information.

[49] Trial information.

[50] Trial information.

[52] Morten Skærbæk, “Thorning til Tyrkiet: ‘Den her sag er ikke slut,’” Politiken, October 20, 2014.

[56] “State Department Terrorist Designations of Abdullah Ahmed al-Meshedani, Basil Hassan, and Abdelilah Himich,” U.S. Department of State, November 22, 2016.

[58] “Dronekrigeren 4:9 – Bombemålet Basil Hassan,” DR, April 3, 2019.

[59] Mette Mayli Albæk, Jens Vithner, Troels Kingo, Puk Damsgård, and Louise Dalsgaard, “Politiet har været på sporet af dansk terrornetværk siden 2013,” DR, April 4, 2019. For more on the Islamic State’s drone program, see Don Rassler, The Islamic State and Drones: Supply, Scale, and Future Threats (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2018).

[60] Trial information.

[62] Trial information.

[64] Mette Mayli Albæk, Troels Kingo, Jens Vithner Hansen, Louise Dalsgaard, and Puk Damsgård, “Terrormistænkt på fri fod: DR finder ham i Tyrkiet,” DR, April 14, 2019; Mette Mayli Albæk, Louise Dalsgaard, and Jakob Skaaning, “Politikere om terrorsigtet på fri fod i Tyrkiet: Udenrigsministeren må ind i sagen,” DR, April 15, 2019.

[65] “Dronekrigeren 8:9 – Bilvaskeren i Bursa,” DR, June 13, 2019.

[66] “Dronekrigeren 5:9 – Krigsfangerne i Basils hus,” DR, April 6, 2019.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Zammit, “Operation Silves.”

[81] Ibid.

[82] Authors’ information from sources. See also Albæk, Aabenhus, Kingo, Damsgård, and Vithner; and “Dronekrigeren 9:9 – Bomben i kødhakkeren,” DR, April 15, 2019.

[83] Zammit, “Operation Silves.”

[84] Ibid.; Andrew Zammit, “New Developments in the Islamic State’s External Operations: The 2017 Sydney Plane Plot,” CTC Sentinel 10:9 (2017).

[85] Zammit, “Operation Silves.”

[86] Ibid. This information was confirmed to the authors by Danish intelligence sources. See also Albæk, Aabenhus, Kingo, Damsgård, and Vithner.

[87] Zammit, “Operation Silves.”

[88] Ibid.

[89] Ibid.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Zammit, “New Developments;” Zammit, “Operation Silves.”

[92] Ibid.

[93] Zammit, “Operation Silves.”

[94] For more on Rauf, see Raffaello Pantucci, “A Biography of Rashid Rauf: Al-Qa`ida’s British Operative,” CTC Sentinel 5:7 (2012). See also Paul Cruickshank’s chapter on the 2006 airline plot In Bruce Hoffman and Fernando Reinares eds., The Evolution of the Global Terrorist Threat From 9/11 to Osama bin Laden’s Death (New York: Columbia University Press, October 2014), chapter 9.

[96] Nash Jenkins, “Egypt Concedes That Terrorists Caused Sinai Plane Crash,” Time, February 25, 2016; “Metrojet Flight 9268: ISIS photo purports to show bomb that brought down Russian aircraft,” Associated Press via CBC, November 19, 2015.

[97] Zammit, “Operation Silves.”

[98] For the authors’ DR reporting on this, see Mette Mayli Abæk, Jens Vithner, and Troels Kingo, “Dømt australsk terrorist: Basil Hassan bag bombe på russisk fly,” DR, November 6, 2019.

[100] Ibid.

[101] Hussein Darwish and Al-Yawm al-Rabi` li, “Fajr al-Jurud” “wa-in ‘Udtum ‘Udna” …Sa’at li-Nihayat Da’ish (The Fourth Day of “The Dawn of Jurud” “And If You Return, We Shall Return” … Hours Before the End of ISIS),” al-Diyar, August 23, 2017.

[103] Authors’ interview with Danish counterterrorism official, late 2019. At the time of writing in May 2020, none of the authors’ intelligence sources have suggested they are now certain Hassan is dead. See also Mette Mayli Albæk, “Analyse: Jagten på Basil Hassan viser, hvad en efterretningstjeneste kan. Og ikke kan,” DR, April 16, 2019.

Skip to content

Skip to content