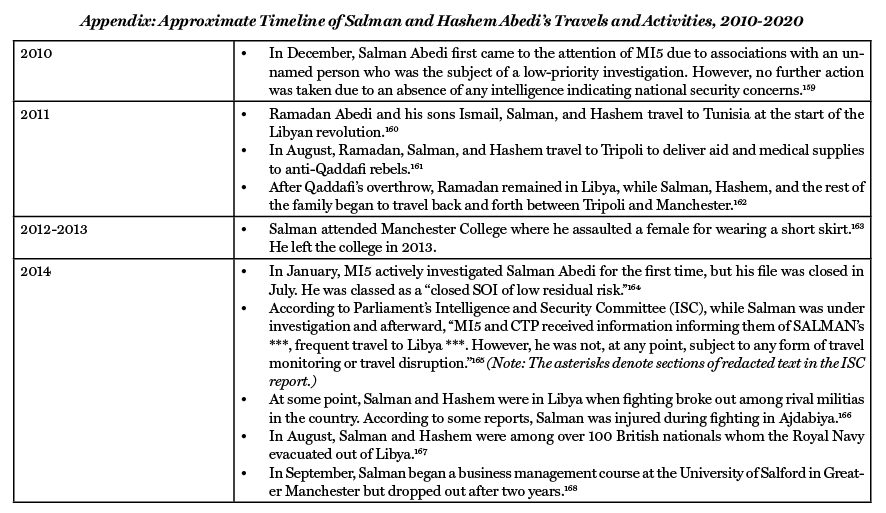

Abstract: May 2020 marks the third anniversary of the suicide bombing attack at the Manchester Arena in the United Kingdom. The attack was carried out by Salman Abedi, a 22-year-old of Libyan descent born in the city of Manchester. While it is still not clear, as a matter of public record, whether the Islamic State played a direct role in the attack, Abedi knew several British extremists who joined the group. He was close friends with a key U.K.-based recruiter for the group and reportedly met with Islamic State fighters in Libya. Three years after the attack, his younger brother, Hashem, was tried and convicted in the United Kingdom of assisting and encouraging him to carry out the atrocity. The operational phase of the attack took place over a period of at least five months. The road to Salman and Hashem Abedi’s attack, however, did not emerge in a vacuum. No one else has been charged in connection to the plot, but there were clusters of British-Libyan Islamists in Manchester and Libya, some of whom had connections to al-Qa`ida, the Islamic State, and other extremist groups, over two generations. The two brothers were raised within this Islamist milieu. From a young age, they had close family links to significant extremist figures in their community and later developed their own friendships with local jihadis. This context may have indirectly contributed to a culture in which the two brothers hatched their plan.

On May 22, 2017, Salman Abedi, a 22-year-old of Libyan descent born in the city of Manchester, detonated a large improvised explosive device in the foyer of the Manchester Arena as an Ariana Grande pop concert was drawing to a close. The resulting explosion was so powerful that it killed 22, physically injured 237, and traumatized hundreds more. The Manchester Arena attack came as a local and national shock. The ferocity of the bomb and the targeting of concert-goers, mainly teenagers and youngsters, horrified the country. What paths led brothers Salman and Hashem Abedi to commit an atrocity in their home city? Haras Rafiq, the chief executive of the Quilliam Foundation, has suggested that Salman Abedi’s radicalization was the result of the salafi ideology and theology that he had absorbed in Manchester from a young age.1 The two brothers were also influenced by their interactions with peer networks within Manchester’s Libyan community and in Libya itself, although no evidence has come to light suggesting that anyone else is implicated in their attack. Yet, rather than the Islamic State radicalizing Salman, Rafiq contends, the group “cherrypicked” him.2 If this is true, then it is possible that Hashem was influenced or mobilized in a similar way.

During Hashem Abedi’s trial, the prosecution described the two brothers as follows:

“In the years leading up to the bombing, the brothers had begun to display to [sic] some signs of radicalisation: Salman more so than Hashem. They changed in appearance, becoming more religious and devout. They talked about Libya, the conflict there and expressed support for ISIS.”3

In 2018, moreover, the report by the U.K. Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) into the 2017 terrorist attacks in Britain included sections about the Manchester bombing and the Abedi family. While the report is heavily redacted throughout due to national security concerns, it quoted an excerpt of oral evidence from the U.K. Security Service (MI5) that stated:

“So we cannot even now look at the Abedi case and say it is obvious because of the father’s activities over the years that two or three of the sons would become extremists, but it is relevant to the story, clearly.”4

In the paragraph immediately after, however, the ISC provided its own view on the nature of extremism within the family:

“Nevertheless, post-attack it appears highly likely that SALMAN and HASHEM’s extremist views were influenced by their father RAMADAN Abedi and fostered by other members of their immediate family.”5

Drawing on the text of the prosecution’s opening arguments in the trial of Hashem Abedi, along with relevant official U.K. documents and investigative reports, this article explores the connectivity of Salman and Hashem to networks in Manchester and Libya. The article first describes some of the operational aspects of the bombing, Hashem’s extradition to the United Kingdom from Libya and his subsequent trial and conviction. The article then places the brothers in the context of longstanding extremism within the milieu of the United Kingdom’s Libyan Islamist diaspora, looking at family and community connections over at least two decades. While the article briefly discusses some of Salman and Hashem’s links in Germany, the final sections concentrate on their jihadi connections in Libya and the nexus of their peer networks in Manchester to Libya and Syria.

Unfortunately, the potential threat posed by the Manchester-Libya extremist nexus may not have been sufficiently appreciated, as Assistant Commissioner Neil Basu, the United Kingdom’s Senior National Coordinator for Counterterrorism Policing, described in a CTC Sentinel interview:

“Libya is very close to home for Europe and our allies, but for a long time, it was not the focus for our attention. For us in the U.K., what happened in Manchester was a big wake-up call to the fact that there were people who had traveled back and forth to Libya doing much the same thing we were preventing people from doing in Iraq and Syria and who had a similar hatred for this country.”6

Pre-Attack Reconnaissance, the Attack, and the Trial

At 10:31 PM on May 22, 2017, Salman Abedi detonated his large improvised explosive device (IED) hidden in the 65-liter backpack he was carrying. He was standing among the crowds departing the Ariana Grande concert in the Manchester Arena, one of the largest indoor venues in Europe. The explosion killed 22 and physically injured 237 others, 91 of whom were classed as being either “very seriously” or “seriously” injured. Of the fatalities, the youngest was an eight-year-old girl, and nine were teenagers.7

Abedi arrived via Metrolink at Victoria Station at 8:30 PM. He spent his final two hours wandering around the station and the shared spaced adjacent to the Arena, including the City Room that is often described as the Arena’s foyer. According to the official account, Abedi appeared to be “awaiting the conclusion of the performance and the then expected departure of concert goers from the building.”8 His device was packed with TATP explosive and a large quantity of shrapnel of screws, nuts, and cross dowels. Police later recovered from the blast scene shrapnel and metal fragments weighing over 30 kilos, including 3,000 nuts.9 With the explosion forcing the shrapnel in all directions, it caused most of the injuries and fatalities.10 Weighing around 36 kilos, the IED was heavy and powerful.11 So powerful, in fact, that the explosion dismembered Salman Abedi,12 propelling his head and upper torso to Victoria Station’s ticket hall, which is about 160-200 feet away from the blast scene.13

At the time of the attack, Salman was not under investigation, though he had twice been an MI5 “Subject of Interest” (SOI) whose cases were closed.14 His prior criminal record related to theft, receiving stolen goods, and assaulting a female at college for wearing a short skirt.15 Crime scene evidence, however, implicated Salman within hours. He had carried out at least three pre-attack hostile reconnaissance visits to the Arena.16 Salman’s first visit—four days before the attack—was in the early evening of May 18; his return flight to Manchester from Libya (via Düsseldorf) landed earlier the same morning.17 Salman visited the Manchester Arena and the City Room, the precise location of his imminent attack.18 CCTV footage showed Salman scouting the area during a Take That concert, while observing the crowds before the concert and the long lines at the box office.19 Salman visited the venue again on May 21, the day before the attack, and a third and final time earlier in the evening on May 22 itself.20

The day after the bombing, Salman’s elder brother, Ismail, was arrested in Manchester on suspicion of involvement but was released without charge.21 On May 24, 2017, Libya’s Special Deterrence Force (RADA), a militia acting as the police force of the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA), arrested Salman’s younger brother, Hashem, and their father, Ramadan, at the family home in Tripoli.22 Ramadan was released shortly after without charge. He categorically condemned the attack: “We don’t believe in killing innocents. This is not us … We aren’t the ones who blow up ourselves among innocents. We go to mosques. We recite Quran, but not that.”23

Meanwhile, RADA claimed that Hashem had confessed to knowing all the details of the Manchester Arena bombing and also confessed that both he and Salman belonged to the Islamic State.24 RADA also claimed that Hashem was a “significant player” in a jihadi cell that had been plotting to attack the United Nations’ special envoy to Libya during a visit to Tripoli earlier that year.25

Hashem had left the United Kingdom for Libya on April 15, 2017, around a month before the attack.26 After a two-year extradition process, he was returned to the United Kingdom in July 2019 and was formally arrested and charged. His trial commenced in February 2020, and he pleaded not guilty to all charges. But while the trial was slated to last two months, it concluded several weeks early in a dramatic turn of events after Hashem dismissed his counsel and decided against mounting a defense. On March 17, after deliberating for four and a half hours, the jury found him guilty of 22 counts of murder, one count of attempted murder, and one count of conspiracy to cause an explosion likely to endanger life in connection to his brother’s attack.27 a

Hashem’s trial revealed important details on how he and his brother plotted the attack.28 Together with Salman, Hashem had persuaded individuals (who were unaware of the two brothers’ intentions) to purchase chemicals on their behalf;b they obtained metal containers and experimented with prototypes;29 and they bought a car in April 2017 that was used to store their bomb-making equipment.30 Hashem’s fingerprints and a matching DNA profile, along with traces of TATP, were found in an apartment the brothers used in Blackley, north Manchester.31 Hashem’s fingerprints were also found on the pieces of cans that were modified for use as detonator casings,32 as well as on the nails and screws that, in the words of the prosecution, the two brothers bought “with a view to deployment in a lethal explosion.”33

The prosecution’s case against Hashem focused on the evidence demonstrating his joint culpability, detailing how the two brothers prepared for their attack. The prosecution stated that they “expressed support for ISIS” and noted Salman’s friendship with a convicted terrorist from Manchester;34 however, the trial did not reveal the extent of guidance or direction, if any, the Islamic State may have provided for the Manchester attack. During the trial, the jury was shown footage of a jihadi bomb-making video, which the brothers may have watched and which provided instructions on how to produce an explosive device using TATP.35 An expert witness described the similarities and differences between the two brothers’ IED and the one demonstrated in the video.36 In a summary of the trial after its conclusion, the BBC wrote that Salman and Hashem “are believed to have followed instructions from an IS video, then accessible online, although they might also have gained relevant expertise in Libya.”37

Disturbingly, the two brothers had used an email address to purchase chemicals for their explosive that was an English transliteration of an Arabic phrase meaning “to slaughter we have come” or “we have come to slaughter.”38 This slogan, popular at the time among jihadi militants, encapsulates the two brothers’ malevolent intentions. Indeed, this is an important point to which this article will return later.

Manchester’s Libyan Islamist Milieu: Family and Community

The city of Manchester, United Kingdom, is home to the largest community of Libyans outside Libya. Estimates put its numbers at 5,000 or higher, with most living in the suburbs of Cheetham Hill, Chorlton, Whalley Range, and Fallowfield.39 Many in the community came to Manchester in the 1980s and 1990s, having left Libya due to their opposition to Muammar Qaddafi’s regime. Among these refugees were Islamists, including numerous members and leaders of what became the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG).40 In the aftermath of the attack, some Libyans in the city spoke openly to the media about their long-held concerns regarding radicalization, extremism, and anti-Semitism within sections of their community.41

Salman and Hashem’s father, Ramadan Abedi (also known as Abu Ismail), is a Libyan national who left Libya for Saudi Arabia in 1991 after being accused of using his position as a government security official to leak information to anti-Qaddafi Islamists.42 He and his wife subsequently sought asylum in the United Kingdom. After first living in London, they settled in 1992 in the Fallowfield area of Manchester, before moving again to nearby Whalley Range, both of them suburbs already home to a tight-knit community of Libyan Islamist dissidents many of who were part of the LIFG.43 Ramadan is reported to have been associated with prominent jihadi figures who had associations with al-Qa`ida, such as Abu Anas al-Libi and Abd al-Baset Azzouz.44 Additionally, a Libyan businessman informed BBC Arabic that “Abedi’s father supported the radical cleric, Abu Qatada, and used to meet him in London.”45 Ramadan, however, has denied having any ties to any of Libya’s militias, including LIFG, and he has never been charged in the United Kingdom with any offense.46

Abu Anas Al-Libi took part in the Afghan war against the Soviet Union and became a member of al-Qa`ida.47 In 1992, al-Libi was among the al-Qa`ida operatives who relocated with Usama bin Ladin to Sudan; however, in 1995, he was among a cohort of Libyans expelled from the country after pressure from Qaddafi.48 Al-Libi was also a longstanding senior member of the LIFG from its origins.49 He was granted asylum in the United Kingdom in 1995, and in 1998, he settled, like the Abedi family, among the Libyan community in Manchester.50 Al-Libi’s lawyer Bernard Kleinman has stated that al-Libi was no longer an al-Qa`ida member after the early 1990s and never swore bay`a (allegiance) to bin Ladin. Yet according to Kleinman, al-Libi “had been really close to bin Ladin and knew him in the Sudan, and they remained very close on a friendship level.”51

In 2000, British police had discovered in al-Libi’s home in Manchester the 180-page terrorist training manual titled “Military Studies in the Jihad Against Tyrants,” better known as the “Manchester Manual.”52 In December 2000, a New York grand jury indicted al-Libi in absentia for his alleged involvement in activities that culminated in al-Qa`ida’s 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.c

Moreover, in December 2014, The New York Times reported about a series of letters involving al-Libi that were captured in bin Ladin’s Abbottabad compound during the U.S. raid in May 2011.53 The documents included a letter from al-Libi to bin Ladin, as well as correspondence about al-Libi between bin Ladin and his deputy, Atiyah Abd al-Rahman.54 Because the U.S. government had only declassified 17 documents from a much larger trove of files, U.S. prosecutors sought judicial permission to unseal the documents involving al-Libi to use during his trial. According to the New York Times report, the prosecutors’ court filing quoted translated excerpts from some of the documents pertaining to al-Libi. In October 2010, for example, al-Libi reportedly wrote to bin Ladin describing that, “You may know the place you hold in my heart, and so I ask Allah to bring us together.”55 Additionally, Atiyah himself wrote to bin Ladin that he had assigned al-Libi to be on al-Qa`ida’s security committee, although it is not clear whether al-Libi assumed the position. And in March 2011, al-Libi had reportedly asked permission to return to Libya with others to join the anti-Qaddafi rebellion.56

The ties between the Abedi and al-Libi families appear to have been particularly close.57 Ramadan’s wife had been a friend of Anas al-Libi’s wife since their time at college in Tripoli, and the two women had lived together in Manchester.58 When U.S. forces eventually captured al-Libi at his Libyan home in Tripoli in October 2013, Ramadan Abedi knew of the arrest within hours and posted an image of al-Libi on his Facebook page along with the words: “Prophet we know how many people have put the picture of this lion in their profiles …”59 d

After the Manchester Arena bombing, one of Salman and Hashem’s cousins, who expressed his horror over the attack, told the British newspaper The Sunday Times that he felt Salman was radicalized through close contact in Manchester and Tripoli with the al-Libi family: “Al-Liby and his family lived here in Manchester once … I remember them from when I was young. He was a terrorist wanted by the Americans. I think it was his family who radicalised him [Abedi].”60 But it should be noted that according to al-Libi’s lawyer Kleinman, when al-Libi returned to Libya (from Iran) at the early stages of the Libyan revolution, he came to consider the West as allies of the LIFG in the fight against Qaddafi. Moreover, as Kleinman explained, al-Libi, “along with most of the other Libyans, was much, much more committed to ridding Libya of Qaddafi than in the political/religious goals of bin Ladin.”61

Similarly, Abd al-Baset Azzouz and his family also settled among the Libyan Islamist community in the suburbs of Manchester.62 In around 2000, Azzouz and his family lived in the same street as the Abedi family and, following that, in homes that were never more than about a mile from each other.63 In May 2006, Azzouz and several other Libyan nationals in Manchester were arrested as part of a counterterrorism operation, but he was later released without charge and left the United Kingdom in 2009. In 2008, Azzouz gave an interview to the U.K.-based Cageprisoners organization (known currently as CAGE) in which he described his arrest and attempted deportation, denying any connections to terrorism.64

In 2014, however, the U.S. State Department designated Azzouz as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT), describing him as “a key operative capable of training al-Qa’ida recruits in a variety of skills, such as IED construction.”e Two days after Abedi’s suicide bombing, the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph reported that U.K. authorities were investigating whether Azzouz had taught Salman Abedi how to make an explosive device, given that Azzouz had set up training camps in Libya.65 No further information confirms this, and it is unclear whether Salman Abedi himself had been to Derna, Libya (where Azzouz was based66) or ever had personal interactions with Azzouz in Libya. However, a Financial Times report in May 2017 quoted a Libyan student and activist in the 2011 revolution who described that Libyans from Manchester were influential among the foreign fighters, including in Derna.67

Many of the Libyan dissidents who settled in Manchester, including those linked with the LIFG, attended the Manchester Islamic Centre, known locally as Didsbury mosque. Described as being a strict Muslim and, like his wife, deeply religious, Ramadan Abedi attended the mosque and was given a job there as a muezzin performing the call to prayers.68 According to the chief executive of Quilliam, Haras Rafiq, the mosque is believed to have an Ikhwani (Muslim Brotherhood) affiliation, but it is also reported that many of the attendees of the congregation were, like the Abedi family, followers of the salafi branch of Islam.69

Neither of these is an indication that the mosque or its congregants supported terrorism, and there is no suggestion of any connection between the mosque and the Arena attack. Indeed, two days after the Arena bombing, mosque leaders issued a statement condemning the attack and calling it a “horrific atrocity.”70 In a separate statement, the mosque reiterated this point and categorically denied any connection to the attack:

“Dealing specifically with Salman Abed, there is no nexus between [Salman Abedi’s] criminal conduct or anything said or done at Didsbury Mosque. The Mosque unconditionally condemns Salman Abedi’s barbaric criminal conduct as being offensive to all civilised norms and the spirit and letter of Islam.”71

Nevertheless, Didsbury mosque came under immense media scrutiny afterward. Salman Abedi had attended the mosque regularly until 2015, when, according to one of its imams, Salman objected to a sermon the imam gave criticizing the Islamic State and the salafi militia Ansar al-Sharia in Libya.72 It also emerged that Salman’s friend from Manchester, Mohammed Abdallah, had attended Didsbury mosque and that Mohammed Abdallah himself claimed to have known a man named Raphael Hostey through there, too.73 Mohammed Abdallah and Hostey were part of a local network of Islamic State supporters and fighters, as will be described later in the section on peer networks.74

In August 2018, the BBC revealed a recording of a sermon given at the mosque in December 2016 in which one of its imams, Mustafa Graf, a dual Libyan-British national, appeared to call for the support of armed jihadi fighters in Syria.75 The sermon had been given at a time when the Syrian city of Aleppo was being bombed. Graf denied that his sermon called for armed jihad, although two Muslim scholars consulted by the BBC assessed that the sermon referred to “military jihad.”76 The mosque’s trustees issued a statement insisting that the sermon was highlighting the plight of Syrians and clarifying that jihad “was used in its wider meaning ‘to strive and struggle.’”77 The mosque said that the sermon had been referring to the need to provide “aid to those being oppressed” and was not “a call for any military action.”78 The United Kingdom’s North West Counter Terrorism Unit later determined that no offense had been committed.79 In any event, the BBC reported that there was no evidence to suggest that either Salman or any other Abedi family member were present during the sermon.80

Germany Connections: Information Gaps

Since the attack, reports have emerged about Salman and Hashem’s travels to, and through, Germany. The extent to which this was relevant to their plot, however, remains unclear. Four days before the bombing, Salman transited through Düsseldorf airport on his way home from Libya to Manchester, via Istanbul.81 German security services were attempting to establish what contacts he may have had there, but he reportedly had remained inside a secure zone.82

In the summer of 2016, Hashem Abedi had moved from Manchester to Weissenfels, a German city home to a Libyan community of over 500.83 Initial reports claimed that he met Libyan real estate agents, which security agencies later accused of being money launderers. Deutsche Welle also reported that “agencies believe Hashem’s journeys in Germany could point to a terrorist financing cell in the country,”84 but no evidence of this was put forward at his trial. While in Germany, Hashem worked at a property business owned by Mohammed Benhammedi, an individual who had been listed as a member of the LIFG in 2006 (by the U.S. Treasury Department) and in 2008 (by the European Union) but whom the United Nations Security Council de-listed in 2011.85 f

During Hashem Abedi’s trial, the prosecution noted that Hashem had booked a flight in October 2016 from Manchester to Germany for travel on January 6, 2017, though he never took the flight.86 Later, on January 17, 2017, the day before he and Salman started to acquire chemicals for their IED, Hashem wired a small sum of money to an unidentified man in Germany.87 And later the same month, he was in contact with another man in Germany about why he had decided against returning to the country, explaining to him that due to having “some problems,” he was unable to leave Manchester.88 Nevertheless, little more was revealed during the trial about how significant (if at all) the two brothers’ links in Germany were to their plot.

Jihadi Connections in Libya

Among the starkest pieces of evidence of Salman and Hashem’s connections to, and affinity for, jihadis in Libya is their use of the email address bedab7jeana [at] gmail [dot] com.89 Created on March 20, 2017, two months before the attack, they used it to purchase hydrogen peroxide for the manufacture of the TATP explosive used in Salman’s IED.90 As the prosecutor explained in court during Hashem’s trial, the email represents an English transliteration of an Arabic phrase meaning “we have come to slaughter” or “to slaughter we have come.”91 The jury also heard that the phrase had become a widely used slogan in certain jihadi circles as a threat to potential opponents. Significantly, the Katibat al-Battar al-Libi (KBL), a core Islamic State unit linked to the 2015-2016 attacks in France and Belgium, chose these words as its slogan when it formed in 2012.92 Salman Abedi, as discussed below, had reported links to KBL.

The path back to Libya, however, began at the start of the 2011 civil war, when Ramadan, Salman, Hashem, and elder brother Ismail Abedi traveled to Tunisia where Ramadan reportedly “worked on logistics for the rebels in western Libya.”93 Later in 2011, Ramadan relocated to Libya. He and others from Manchester’s Libyan community reportedly joined the Manchester Fighters, a unit of the 17 February Martyrs Brigade that fought against the Qaddafi regime; however, as stated previously, Ramadan has denied being linked to any militant groups.94

In September 2012, Ramadan posted a Facebook image of Hashem, then aged 15, posing with a semi-automatic weapon under the caption, “Hashem the lion … in training.”95 Ramadan’s Facebook page is known to have contained images of Islamist fighters and a posting in which he praised the al-Qa`ida-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra.96 After Qaddafi’s overthrow, Ramadan remained in Libya and became an administrative manager of Tripoli’s Central Security Force, which was responsible for policing in the city.97 Reports are unclear as to whether Salman (then aged 16) and Hashem (then aged 15) also fought alongside their father.98 Salman and Hashem, meanwhile, traveled back and forth between Tripoli and Manchester.99 After fighting erupted among rival Libyan factions and militias in 2014, Salman reportedly returned to the country and was injured in 2014 while fighting in Ajdabiya alongside a jihadi faction.100

Salman Abedi was also reportedly involved in the Qudwati youth movement, which was “accused [sic] being a covert conduit providing IS with fighters.”101 One of Qudwati’s founding members is Abdul-Baset Ghwela (Egwilla), a Canadian-Libyan salafi preacher with whom Ramadan Abedi reportedly used to associate during Friday prayers at a mosque in Tripoli.102 U.S. officials claimed that Ghwela, who is believed to have returned to Libya after the fall of Qaddafi in 2011, recruited men to wage jihad in Benghazi. In March 2016, Ghwela’s 20-year-old son, Awais, was killed while fighting with the Omar Mukhtar Brigade in Libya.103 He too was a member of the Qudwati.104

In a previous issue of CTC Sentinel, Johannes Saal offered important insight into the Islamic State’s Libyan operations, highlighting the Libyan nexus to Islamic State-aligned individuals in the United Kingdom and Germany.105 Evidence points to the connectivity of Salman within these networks. During periods Salman spent in Libya, at some stage he met members of the KBL, according to The New York Times. The newspaper reported that after returning to Manchester, Salman remained in communication with KBL, at times via an intermediary who was living either in Germany or Belgium, according to an anonymous former “European intelligence chief.”106

In October 2015, MI5 classified Salman as a Subject of Interest (SOI) for the second time due to his contact with an unidentified Islamic State figure in Libya, according to an independent assessment of the terrorist attacks in the United Kingdom in 2017. However, his file was closed on the same day it was opened “when it transpired that any contact was not direct.”107 g Following the 2017 Manchester attack, it was reported that around 65 previously U.K.-based KBL jihadis may have returned home to the United Kingdom from Libya over a period of time.108

In the days following the attack, The Daily Telegraph interviewed an unnamed Libyan security source who claimed that Salman made five calls to Libya from his cell phone before detonating his IED on May 22, 2017. The first two calls were reportedly to each of his parents, after which he called Hashem. Finally, according to this reporting, Salman called two cell phone numbers reportedly linked to Libyan men suspected of being members of KBL.109 The Libyan source claimed that “the suspicion is that these guys were also part of the plot and either knew about it beforehand or were actively encouraging Abedi to carry out the attack.”110

During Hashem Abedi’s trial, the prosecution explained that Salman had made a series of calls to Libya in the days and hours before the attack.111 The prosecution’s opening statement stated that Salman was in contact with a Libyan telephone number earlier in the day on May 22 and that he had arranged for a transfer of funds to his family in Libya.112 At 8:23 PM, while en route to the Manchester Arena and just over two hours before the bombing, he again phoned the Libyan number connected to his family in Libya.113 No further information emerged at trial on whether or not Salman called other individuals just before the attack as The Daily Telegraph reported. There is no suggestion that members of his family, other than Hashem, had any knowledge of his planned attack beforehand.

Manchester-Libya-Syria Jihadi Nexus: Peer Networks and Friendships

Peer networks and personal friendships constituted a significant component of Salman and Hashem Abedi’s links to jihadis in Manchester, Libya, and Syria. This includes a local cohort who were part of the Manchester network of Islamic State supporters and fighters. Most of these individuals were either jailed in the United Kingdom or killed on jihadi battlegrounds prior to Salman carrying out the Manchester Arena attack.114 In particular, a pair of brothers, Mohammed and Abdalraouf Abdallah, were close friends of Salman and Hashem. Abdalraouf would go onto become one of the Islamic State’s most prolific recruiters in the United Kingdom.

The Abdallahs, just like the Abedis, are British-Libyans from the same area of Manchester. Abdallah family arrived in the United Kingdom as refugees from Libya in 1993.115 In 2011, Mohammed Abdallah traveled to Libya with friends of his father after the start of the anti-Qaddafi uprising.116 Mohammed told jurors during his trial that he joined the Tripoli Brigade, which was known to be an Islamist militia associated with the LIFG.117 Abdalraouf traveled there the same year and joined the 17 February Martyrs Brigade—the same unit that Ramadan Abedi reportedly joined.118

Sometime in 2011, Abdalraouf was shot in the spine during fighting, rendering him paraplegic and wheelchair bound. While receiving treatment in hospital in Tripoli, an Abedi family member reportedly spent time at Abdalraouf’s bedside.119 Ramadan Abedi asked friends on Facebook to pray for Abdalraouf.120 Later that year, Abdalraouf returned to Britain for treatment and lived with his family in the Manchester suburb of Moss Side.121 After Salman himself returned to Manchester following Qaddafi’s overthrow, he was seen regularly pushing Abdalraouf in his wheelchair to and from Friday prayers at a mosque close to the Abdallah family’s home.122

Back in the United Kingdom, Abdalraouf eventually became a key figure among Islamic State supporters and fighters from Manchester. With his injury preventing him from fighting for the Islamic State, Abdalraouf’s fanatical support for the organization led to him becoming a recruiter for it. In July 2014, he used the family home as a hub to facilitate travels to join the Islamic State in Syria. According to the prosecution at his trial, Abdalraouf was “directing operations on a daily basis” using contacts in Brussels, Jordan, and Syria.123 Specifically, the Crown Prosecution Service demonstrated that he assisted his older brother, Mohammed, who had returned to the United Kingdom from Libya in 2012, and three others from Manchester (Nezar Khalifa (also of Libyan descent), Raymond Matimba, and Stephan Gray) to travel to Syria and join the Islamic State.124 Indeed, that same month, Mohammed traveled to Syria, via Turkey, with Khalifa.h The pair planned to join the Islamic State with Grayi and Matimba,j both converts to Islam from the Moss Side area of Manchester.125

Before Mohammed Abdallah had crossed the Turkish border into Syria, Abdalraouf Abdallah arranged for him to receive £2,000 and an assault rifle. The cash, which British police believe was for the purchase of guns, was wired to him at a hotel in Istanbul by their father in Manchester.126 There is no suggestion that their father knew of his sons’ involvement or that he knew for what purpose the money was intended. Although Gray was turned back at the Turkish border and returned to Manchester, Mohammed Abdallah, Khalifa, and Matimba entered Syria and were met by Islamic State fighters who took them to a training camp.127

At some point in July 2014, Mohammed Abdallah filled out an official Islamic State application form and was permitted to leave Syria for Libya less than a month later.128 Interestingly, only trusted Islamic State fighters were ever permitted to do this.129 Having reached Libya again, Mohammed joined a government militia and remained in the country until 2016.130

In March 2016, Sky News received files from an Islamic State defector that included Mohammed Abdallah’s completed registration form.131 He had listed himself as being a specialist sniper with fighting experience in Libya. At the time, volunteer fighters could only join the Islamic State by providing the name of a referee already known to commanders. Mohammed Abdallah provided two names: Raphael Hostey (aka Abu Qa’qa al-Britani) and Salem Musa Youssef Elkhafaifi (aka Abu Othman al-Libi), both of whom had previously lived in Manchester.132

Mohammed Abdallah and Hostey, as mentioned, knew each other through Didsbury mosque in Manchester.133 After leaving Manchester for Syria in 2013, Hostey became one of the Islamic State’s most important Syria-based British recruiters; he was killed in an airstrike in Syria in 2016.134 Furthermore, Mohammed Abdallah described Elkhafaifi on the application form as a “family friend.”135 Like Mohammed Abdallah, Elkhafaifi had left Manchester in 2011 to fight in the Libyan conflict. From there, he joined the Islamic State in Syria and featured in a 2014 propaganda video released when the organization claimed to have formed a new state.136 According to one report, Elkhafaifi was killed in a coalition airstrike in Syria in October 2015.137

Eventually, in September 2016, Mohammed Abdallah voluntarily returned to the United Kingdom, where he was arrested and charged with membership of the Islamic State, possessing an AK-47 assault rifle and receiving £2,000 for the purposes of terrorism. He stood trial in November 2017 and, the following month, was found guilty on all charges.138 Meanwhile, his younger brother Abdalraoufk and their mutual friend Stephan Gray had been arrested two years earlier in Manchester and, in May 2016, were convicted for a number of terrorism offenses.139

Salman Abedi featured prominently in these circles. He was an associate of Manchester extremists turned Islamic State fighters Raphael Hostey and Raymond Matimba (aka Abu Qaqa al-Britani al-Afro).140 All three men are reported to have visited the same (unidentified) Manchester mosque, in addition to Hostey and Mohammed Abdallah having known each other from Didsbury mosque, as noted earlier.141 l

In Raqqa, Syria, Matimba had joined an Islamic State cell that included numerous British jihadis. He reportedly remained in contact with Salman Abedi up to May 2017.142 In September 2017, The Daily Telegraph obtained exclusive footage, which was filmed in November 2014, showing British members of the cell in conversation in a Syrian café. According to the newspaper’s source, a Syrian man who smuggled the footage out of the country, Matimba hated his home city of Manchester and wanted the cell to plot a bomb attack against it.143 Note, as well, that Reyaad Khan from Cardiff, Wales, was another member of the same Islamic State cell.144 In June 2014, a Facebook user named Afzul Ali posted the image of a frontpage newspaper report regarding Khan’s appearance in an Islamic State recruitment video. In a Facebook reply to the posting, Hashem Abedi appeared to praise Khan and appeared to suggest to Ali that they both join him in Syria.145

Additionally, Salman Abedi visited Abdalraouf Abdallah in jail while Abdalraouf was being held on remand awaiting trial, as well as after he was convicted.146 In fact, Abdalraouf maintained contact with Salman using a cell phone that he was holding illegally in jail.147 During Hashem Abedi’s trial, it emerged that Salman and two associates visited Abdalraouf in prison on January 18, 2017.148 This coincided with the same date that Salman and Hashem arranged their first purchase of some of the chemicals needed for their planned attack,149 though no evidence implicates Abdalraouf or anyone else for taking part in their plot.

Conclusion

Salman and Hashem Abedi are responsible for murdering 22 innocent people, physically injuring over 200, and psychologically traumatizing over 600 victims in the Manchester Arena. They planned and organized the bombing together. No one else has been charged in connection to the plot. But there have been networks of British-Libyan Islamists in Manchester and Libya, some of whom had connections to global jihadi groups, over two generations. This context may have indirectly contributed to a culture in which the two brothers devised their plan.

The post-attack investigation was on a vast scale. Police took thousands of witness statements, analyzed thousands of hours of CCTV footage, sifted through at least 16 terabytes of data from hundreds of devices and collected extensive forensic evidence at the scene of the attack and across the locations in Manchester that Salman and Hashem Abedi used to prepare for the bombing.150 In 2018, the United Kingdom’s then independent reviewer of terrorism legislation (IRTL) praised the police operation, stating that “[f]ew terrorist investigations reach the scale of Operation Manteline” and noting that it constituted “a good example of interoperability on the part of CT Policing.”151

The same year, the U.K. government also commissioned David Anderson QC, himself a former IRTL, to write an independent assessment of police and MI5 internal reviews into the 2017 terrorist attacks in the United Kingdom, including at the Manchester Arena. Although Salman Abedi’s intelligence file was closed and thus not under active investigation at the time of his attack, the review noted that MI5 had intelligence in the months beforehand, “which, had its true significance been properly understood, would have caused an investigation into him to be opened.”152

MI5 assessed that this would not have led to “Abedi’s plans to be pre-empted and thwarted”153 and that the intelligence decision not to reopen his case was “finely-balanced.”154 In fact, an MI5 “data-washing exercise” identified Salman Abedi as one of a small number of individuals—within a pool of more than 20,000 closed subjects of interest—who warranted closer scrutiny.155 And a meeting to discuss his case, which was scheduled before the attack, was arranged for May 31, 2017—tragically, nine days after the attack took place.156

Anderson’s assessment stated that, although Salman Abedi was a closed SOI, “an opportunity was missed by MI5 to place Salman Abedi on ports action following his travel to Libya in April 2017.”157 Such a step would have acted as an alert when Salman flew back to the United Kingdom on May 18, 2017—four days before his attack. Additionally, the forthcoming coroner’s inquest into the May 22 bombing is expected to include more evidence from authorities about the Abedis, though this has been postponed until September 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is not in doubt is Salman and Hashem’s extremist mindset and the premediated steps they took to plan and execute a deadly attack. Speaking after Hashem’s conviction, Detective Chief Superintendent Simon Barraclough, the case’s senior investigating officer, best encapsulated the pair’s culpability:

“If you look at these two brothers, they are not kids caught in the headlights of something they don’t understand. … These two men are the real deal, these are proper jihadis – you do not walk into a space like the Manchester Arena and kill yourself with an enormous bomb like that, taking 22 innocent lives with you, if you are not a proper jihadist.”158 CTC

Eran Benedek and Neil Simon are senior analysts at CST (Community Security Trust) and specialize in monitoring and assessing threats from extremism and terrorism. CST is a British charity that works to protect the U.K. Jewish community from anti-Semitism and related threats. CST is recognized by the U.K. police and the U.K. government as a unique model of best practice. Follow CST @cst_uk

Substantive Notes

[a] Hashem was due to be sentenced in late April 2020, but this has been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

[b] During Hashem’s trial, the court heard details about Salman and Hashem’s friends and associates who unknowingly assisted the brothers in various aspects of their plot, though they themselves have not been charged with any crime relating to the attack. See Daniel De Simone, “The road to the Manchester Arena bombing,” BBC, March 17, 2020.

[c] As a senior member of LIFG, Nazih Abdul Hamed Al-Ruqai (also known as Abu Anas Al-Libi) had responsibility for running the Afghanistan end of the Sanabel Relief Agency, a U.K.-registered charity accused of raising money for the LIFG. Two of the charity’s five U.K. addresses were in Manchester. In 1999, al-Libi was arrested in Manchester but was released without charge due to lack of evidence. After leaving the United Kingdom, he relocated to Afghanistan but was among a group of Libyans and al-Qa`ida members who relocated to Iran after the Taliban’s overthrow. He remained in Iran for nearly 10 years before moving to Libya at the early stages of the Libyan revolution. The U.S. indictment against al-Libi included allegations that he conducted surveillance of the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi in 1993 and that in 1994 he had reviewed files about possible terrorist attacks against the same location as well as the USAID facility in Nairobi and Israeli, British, and French targets in Nairobi. After his October 2013 capture, al-Libi pleaded not guilty to terrorism charges. See Jamie Doward, Ian Cobain, Chris Stephen, and Ben Quinn, “How Manchester bomber Salman Abedi was radicalised by his links to Libya,” Guardian, May 28, 2017; “Profile: Anas al-Liby,” BBC, January 3, 2015; Paul Cruickshank, “A View from the CT Foxhole: Bernard Kleinman, Defense Attorney,” CTC Sentinel 10:4 (2017): pp. 10-11; Assaf Moghadam, “Marriage of Convenience: The Evolution of Iran and al-Qa`ida’s Tactical Cooperation,” CTC Sentinel 10:4 (2017): pp. 14-15; Tim Lister and Paul Cruickshank, “Senior al Qaeda figure ‘living in Libyan capital,’” CNN, September 27, 2012; United States of America v Usama Bin Laden et al., S(9) 98 Cr. 1023 (LBS).

[d] On January 2, 2015, al-Libi died in a New York hospital following a deterioration in an underlying health condition. His trial was due to start on January 12, 2015. Jomana Karadsheh, “Alleged al Qaeda operative Abu Anas al Libi dies in U.S. hospital, family says,” CNN, January 3, 2015; “Profile: Anas al-Liby.”

[e] The U.S. State Department described Azzouz as follows: “Abd al-Baset Azzouz has had a presence in Afghanistan, the United Kingdom, and Libya. He was sent to Libya in 2011 by al-Qa’ida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri to build a fighting force there, and mobilized approximately 200 fighters. He is considered a key operative capable of training al-Qa’ida recruits in a variety of skills, such as IED construction.” See “Designations of Foreign Terrorist Fighters,” U.S. State Department, September 24, 2014. After leaving the United Kingdom in 2009, Azzouz first traveled to Pakistan and became a lieutenant of al-Qa`ida’s leader Ayman Al-Zawahiri who, in May 2011, appointed him head of the group’s operations in Libya. Azzouz was suspected of involvement in the 2012 attack on the U.S. State Department Special Mission Compound in Benghazi and was reportedly arrested in Turkey in 2014. He was reportedly sent to Jordan before his expected deportation to the United States to face charges, but no public information on his current whereabouts and status appears to be available. “Designations of Foreign Terrorist Fighters,” U.S. State Department, September 24, 2014; “Turkish security forces capture Benghazi attack suspect,” Daily Sabah, December 4, 2014; Robert Mendick, “Freed UK prisoner is al-Qaeda ringleader,” Telegraph, September 27, 2014.

[f] In February 2006, Benhammedi was among five U.K.-based individuals and four U.K.-based entities that the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated for their alleged role in financing LIFG. In 2008, an E.U. regulation described Benhammedi as being a member of LIFG, though this lapsed following the United Nations Security Council’s de-listing. However, note that at least one of the individuals designated in both the Treasury and E.U. lists, Tahir Nasuf, denied that he was a member of or had links to the LIFG. See “Treasury Designates UK-Based Individuals, Entities Financing Al Qaida-Affiliated LIFG,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, JS-4016, February 8, 2006; Commission Regulation (EC) No 1330/2008, Legisilation.gov.uk; Rosie Cowan, “Man denies terror link after assets freeze,” Guardian, February 9, 2006.

[g] MI5 classified Salman Abedi as a SOI for the first time in January 2014, following an investigation in which he was believed to have been in contact with another (unidentified) SOI. His file was closed, however, in July 2014 after Abedi “was classed as a closed SOI of low residual risk, given his limited engagement with persons of national security concern.” See David Anderson Q.C., “Attacks in London and Manchester March-June 2017: Independent Assessment of MI5 and Police Internal Reviews – Unclassified,” December 2017, pp. 15-16.

[h] Nezar Khalifa’s current status and whereabouts are unknown. At some stage, he and Mohammed Abdallah were thrown out of Syria but later returned to the country. See Dominic Casciani, “Mohammed Abdallah: Leaked IS document helps convict Manchester man,” BBC, December 7, 2017.

[i] In July 2016, Stephan Gray was jailed, having been sentenced to an extended determinate term of nine years: five years in custody and four years “on licence” (supervision under parole). He had pleaded guilty to committing acts of terrorism, being engaged in preparation of these acts, assisting acts of terrorism, and funding terrorism. See “Press statement,” Greater Manchester Police, Facebook, July 15, 2016; “Regina v Mohammed Abdallah, Sentencing Remarks of Mrs Justice McGowan,” Judiciary of England and Wales, December 8, 2017, p. 3.

[j] Raymond Matimba’s fate and whereabouts remain unconfirmed, but he is believed to have been killed while fighting for the Islamic State. See Andy Hughes, “The IS Files: Unmasking Britain’s terrorists,” Sky News, December 7, 2017.

[k] In July 2016, Abdalraouf was jailed, having been sentenced to an extended determinate sentence of 9.5 years: 5.5 years in custody and four years on an extended “licence” (supervision under parole) period. See “Press statement,” Greater Manchester Police, Facebook, July 15, 2016; “Regina v Mohammed Abdallah, Sentencing Remarks of Mrs Justice McGowan,” Judiciary of England and Wales, December 8, 2017, p. 3.

[l] Hashem Abedi’s Facebook account, moreover, showed that he had been in regular contact with Hostey’s younger brother. See Josie Ensor, “Manchester bomber’s brother was ‘plotting attack on UN envoy in Libya,’” Telegraph, May 27, 2017.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), T20197240, February 3, 2020, p. 5.

[5] Ibid., p. 92.

[7] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening.

[8] Ibid., p. 60.

[9] Ibid., p. 65.

[10] Ibid., p. 65.

[11] Ibid., p. 59.

[12] Ibid., p. 4.

[15] Max Hill Q.C., “The Terrorism Acts 2017: Report of the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation on the Operation of the Terrorism Acts 2000 and 2006, the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011, and the Terrorist Asset Freezing Etc Act 2010,” October 2018, p. 122; Joan Smith, “If we start to link terrorism and domestic violence, we might just stop the next attack,” Telegraph, May 23, 2019.

[17] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, pp. 51-52.

[18] Ibid., p. 52.

[19] “Jury shown footage of Manchester Arena bomber visiting venue,” Guardian, February 24, 2020; “Manchester Arena bomber Salman Abedi captured on CCTV days before attack,” BBC, February 24, 2020.

[20] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, pp. 57-60.

[21] “Abedi’s brother released without charge,” BBC, June 5, 2017.

[22] “Libyan official says Abedi’s brother under surveillance for six weeks,” Libya’s Channel TV in Arabic 20:44 GMT May 25, 2017, BBC Monitoring translation, May 26, 2017; “Name in the News: Libya’s Special Deterrence Force,” BBC Monitoring, May 26, 2017; Josie Ensor, “Manchester bomber’s brother was ‘plotting attack on UN envoy in Libya,’” Telegraph, May 27, 2017.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Brother of Manchester Arena bomber guilty of murder,” Crown Prosecution Service, March 17, 2020.

[27] Ibid.

[28] For a succinct overview of the key evidence and how the two brothers planned the attack, see the official press statement of Greater Manchester Police: “A man who conspired with his brother to carry out a terror attack that killed 22 people at the Manchester Arena has been convicted,” Greater Manchester Police, March 17, 2020.

[29] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, pp. 2, 5.

[30] Ibid., pp. 2, 34, and 45.

[31] Ibid., p. 15.

[32] Ibid., pp. 7-8 and 56.

[33] Ibid., p. 55.

[34] Ibid., p. 5.

[35] “Manchester Arena attack: Jurors shown bomb-making video,” BBC, February 28, 2020.

[37] Daniel De Simone, “The road to the Manchester Arena bombing,” BBC, March 17, 2020.

[38] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, p. 29.

[39] Doward, Cobain, Stephen, and Quinn; Rory Smith and Ceylan Yeginsu, “For Manchester, as for Its Libyans, a Test of Faith,” New York Times, May 25, 2017.

[40] Doward, Cobain, Stephen, and Quinn.

[42] Michael.

[43] Doward, Cobain, Stephen, and Quinn.

[44] Ibid.; Andrew McGregor, “Qatar’s Role in the Libyan Conflict: Who’s on the Lists of Terrorists and Why,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor 15:14 (2017); Bel Trew, “Manchester is a haven for Libya’s opposition,” Times, May 26, 2017.

[45] “Manchester attack: Who was Salman Abedi?” BBC, June 12, 2017; “Omar Othman (a.k.a., Abu Qatada) and Secretary of State for the Home Department,” Appeal No. SC/15/2005, Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC), February 26, 2007.

[46] Michael.

[48] Tim Lister and Paul Cruickshank, “Senior al Qaeda figure ‘living in Libyan capital,’” CNN, September 27, 2012; Daniel Byman, “Libya’s Al Qaeda Problem,” Brookings Institution, February 25, 2011.

[49] Cruickshank, p. 11.

[51] Cruickshank, p. 11.

[54] Ibid.; Thomas Jocelyn, “Analysis: Osama bin Laden’s Documents Pertaining to Abu Anas al Libi Should be Released,” FDD’s Long War Journal, January 3, 2015.

[55] Weiser.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Osuh.

[58] Michael.

[59] Osuh. Colleagues of the authors provided a translation of the posting.

[61] Cruickshank, p. 11.

[62] Martin Evans, Victoria Ward, and Robert Mendick et al., “Everything we know about Manchester suicide bomber Salman Abedi,” Telegraph, May 26, 2017; “Al-Qaeda In Libya: A Profile,” Library of Congress – Federal Research Division, August 2012, pp. 11-24.

[63] Gordon Rayner and Robert Mendick, “Pictures leaked ‘after being shared with US intelligence’ show bomb used in Manchester attack,” Telegraph, May 24, 2017.

[64] Asim Qureshi, “Interview with Abdul Baset Azzouz,” Cageprisoners, April 23, 2008.

[65] Rayner and Mendick.

[66] Alfred Hackensberger, “The Islamists Are Worse Than Al-Asad,” Welt Am Sonntag, December 15, 2013 (translated by BBC Monitoring under the title “German report: Libyan fighter explains decision to abandon jihadists in Syria,” December 17, 2013).

[67] Sam Jones, “Terrorism: Libya’s civil war comes home to Manchester,” Financial Times, May 26, 2017.

[68] Nazia Parveen, “Bomber’s father fought against Gaddafi regime with ‘terrorist’ group,” Guardian, May 24, 2017; John Scheerhout, “Brothers in evil,” Manchester Evening News, March 17, 2020.

[69] Doward, Cobain, Stephen, and Quinn; Osuh; “Didsbury Mosque and Islamic Centre,” Muslims in Britain, UK Mosque/Masjid Directory.

[70] “Statement outside Didsbury Mosque which Manchester attacker allegedly attended,” Ruptly, March 24, 2017 (beginning from 54:00 minutes); Steven Morris, “Didsbury mosque distances itself from Manchester bomber,” Guardian, May 24, 2017.

[71] Didsbury Masjid statement, Facebook, August 16, 2018.

[72] Morris; David Brown, Fiona Hamilton, and Georgie Keate et al., “Salman Abedi was just a regular kid who liked cricket, then it all changed,” Times, May 24, 2017.

[73] “Mohammed Abdallah guilty of joining Islamic State,” BBC, December 7, 2017.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ed Thomas and Noel Titheradge, “Manchester mosque sermon ‘called for armed jihad’, say scholars,” BBC, August 16, 2018; “Manchester mosque denies ‘military jihad’ support,” BBC, August 17, 2018.

[76] “Manchester mosque denies ‘military jihad’ support.”

[77] Didsbury Masjid statement.

[78] Ibid.

[79] “Didsbury Mosque ‘military jihad’ sermon probe ends,” BBC, January 29, 2019.

[80] “Manchester mosque denies ‘military jihad’ support.”

[82] “Manchester: UK resumes intelligence-sharing after US leak,” Deutsche Welle, May 26, 2017.

[83] De Simone; Axel Spilcker, “Spur des Manchester-Attentats führt auch nach Deutschland,” Focus, October 6, 2017.

[84] Alistair Walsh, “Manchester bombing: Salman Abedi’s links to Germany probed by police,” Deutsche Welle, October 7, 2017; Spilcker.

[86] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, p. 12.

[87] Ibid., p. 35.

[88] Ibid., p. 12.

[89] De Simone.

[90] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, p. 29.

[91] Ibid., p. 29.

[92] Scheerhout, “Manchester Arena bombing trial live.”

[94] Parveen.

[95] Osuh.

[96] Ibid.

[98] Bennhold, Castle, and Walsh.

[99] Ibid.; Tom Batchelor, “Salman Abedi: Alleged Manchester attacker’s father says son is innocent,” Independent, May 24, 2017.

[100] Doward, Cobain, Stephen, and Quinn.

[101] “Tripoli imam arrested, accused of promoting terrorism,” Libya Herald, September 11, 2017; Johannes Saal, “The Islamic State’s Libyan External Operations Hub: The Picture So Far,” CTC Sentinel 10:11 (2017): p. 20.

[102] Bel Trew, “Salman Abedi was radicalised by Canadian …,” Times, May 27, 2017.

[103] “Libyan scholars blast reports linking Abdulbaset Ghwaila with Manchester bomber,” Libya Herald, June 6, 2017; “Tripoli imam arrested, accused of promoting terrorism.”

[104] “Libyan scholars blast reports linking Abdulbaset Ghwaila with Manchester bomber.”

[105] Saal, p. 20.

[107] Anderson, p. 16.

[109] Ibid.

[110] Ibid.

[112] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, p. 57.

[113] Ibid., p. 59.

[114] “Ten Years for Isis Sniper Linked to Manchester Bomber,” Court News UK, December 8, 2017.

[115] Josh Halliday, “Jihadist with links to Manchester bomber is guilty of fighting for Isis,” Guardian, December 7, 2017; Andy Hughes, “The IS Files: Unmasking Britain’s terrorists,” Sky News, December 7, 2017.

[116] “Libyan Terrorist with Links to Manchester Arena Bomber Facing Jail,” Court News UK, December 7, 2017.

[117] Halliday.

[118] Ibid.

[119] Jones.

[121] “Accused Terrorist Came to Britain for NHS Treatment,” Court News UK, November 15, 2017.

[122] Halliday; Jamie Roberts, “Manchester: The Night of the Bomb — My search for Salman Abedi,” Times, May 16, 2018.

[123] “R v Mohammed Abdallah,” Crown Prosecution Service, 2017; Duncan Gardham, “Wheelchair-bound man ‘at centre of jihad network,’” Times, April 28, 2016.

[124] “Libyan Terrorist with Links to Manchester Arena Bomber Facing Jail;” “R v Abdallah & Ors,” [2016] EWCA Crim 1868 (8 December 2016).

[125] “Accused Terrorist Came to Britain for NHS Treatment.”

[127] Ibid.

[128] Ibid.

[130] Casciani.

[131] Ibid.

[132] Ibid.

[133] Ibid.

[134] Ibid.

[135] Ibid.

[136] Ibid.

[138] Fiona Hamilton, “Mohammed Abdallah, friend of Manchester bomber Salman Abedi, jailed for ten years,” Times, December 8, 2017; “R v Mohammed Abdallah,” Crown Prosecution Service, 2017.

[139] “Press statement,” Greater Manchester Police, Facebook, July 15, 2016; “Ten Years for Isis Sniper Linked to Manchester Bomber.”

[142] Ibid.

[143] Ibid.

[144] Ibid.

[146] Scheerhout, “Brothers in evil;” John Scheerhout, “Salman Abedi visited convicted terrorist in prison four months before Manchester Arena bombing, trial hears,” Manchester Evening News, February 10, 2020.

[147] De Simone.

[148] Ibid.; Scheerhout, “Brothers in evil.”

[149] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, p. 12.

[150] “Manchester Arena Investigation Update,” U.K. Counter Terrorism Policing, May 16, 2018; Hill, p. 46; “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, collection of forensic evidence described throughout.

[151] Hill, p. 46.

[152] Anderson, p. 15.

[153] Ibid., p. 15.

[154] Ibid., p. 27.

[155] Ibid., pp. 15-16.

[156] Ibid., p. 16.

[157] Ibid., p. 27.

[158]Lizzie Dearden, “Hashem Abedi trial: Manchester attacker’s brother found guilty of murdering bomb victims,” Independent, March 17, 2020; Georgina Morris, “Manchester Arena bomber’s brother found guilty of plot that killed 22 people,” Yorkshire Post, March 12, 2020.

[159] “The 2017 Attacks: What needs to change?” pp. 65-66.

[160] Bennhold, Castle, and Walsh.

[161] “The 2017 Attacks: What needs to change?” p. 66.

[162] Bennhold, Castle, and Walsh; Batchelor.

[163] Hill, p. 122; Smith.

[164] Anderson, p. 15; “The 2017 Attacks: What needs to change?” p. 74.

[165] “The 2017 Attacks: What needs to change?” p. 74.

[166] Doward, Cobain, Stephen, and Quinn.

[167] “Manchester Arena bomber was rescued from Libya by Royal Navy,” Guardian, July 31, 2018.

[168] Evans, Ward, and Mendick et al.

[169] “Tripoli imam arrested, accused of promoting terrorism;” Saal, p. 20.

[170] Ensor.

[171] Patrick Sawer and Jamie Johnson, “‘Jihad’ imam linked to Manchester bomber denies his sermon was a call to arms as police investigate him,” Telegraph, August 12, 2018; “A report states gathering of 17 February in front of the UAE Embassy,” Libyan 17 February Forum, YouTube, September 10, 2015.

[172] Anderson, p. 16.

[173] Osuh.

[175] Walsh; Spilcker.

[176] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, p. 12.

[177] Osuh; “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, p. 44.

[178] “Regina v Hashem Abedi,” Note for Opening, pp. 51-52.

[179] Ibid., pp. 51-52.

[180] Ibid., p. 57.

[181] Ibid., pp. 57-60.

[182] “Brother of Manchester Arena bomber guilty of murder.”

[183] Ibid.

Skip to content

Skip to content