Abstract: This study examines the geographical origins, mobility patterns, and demographic characteristics of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) militants through an analysis of 615 profiles from the organization’s own martyrdom commemorative publications spanning 2006-2025. The findings reveal several important trends: the dominance of religious education among militants with identifiable educational data (120 profiles), particularly among commanders and suicide attackers; and the reemergence of new recruitment centers, particularly in Dera Ismail Khan in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) Province, which appears to have supplanted North Waziristan as a primary operational hub. The data also demonstrates TTP’s strategic expansion beyond traditional strongholds in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa into southern Punjab, urban areas of Sindh, and specific regions in Balochistan. The study also finds that suicide operatives are predominantly from KPK districts Dera Ismail Khan, North Waziristan, Bannu, and Khyber. Role distribution analysis reveals commanders (38.2% of all profiles) were disproportionately represented in cross-border movements (56% of all cross-border movements), while suicide operatives were concentrated in inter-provincial deployments (17.3%). Most significantly, the data reflects increased cross-border mobility between Afghanistan and Pakistan, with KPK-born militants comprising 82 out of 84 Afghanistan-based casualty cases, illuminating the cross-border regional dimensions of this resurgent insurgency. While these insights are based on TTP’s own materials, and therefore have limitations, the trends observed provide unique insights into TTP’s ongoing operational evolution and highlight potential vulnerabilities in its recruitment and deployment architecture.

The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) has unleashed a relentless wave of devastating attacks across Pakistan in recent years, revealing both its enhanced lethal capabilities and strategic expansion. In July 2023,1 suicide bombers targeted a police compound in Bara, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK), killing four officers and wounding 11 others, and a month later in August, a suicide attack in the Jani Khel area of the Bannu district killed another nine soldiers.2 This deadly momentum has persisted unabated into 2024 and 2025, with particularly brazen attacks in July 2024 and March 2025 on military bases in Bannu.3 These deadly assaults are mere flashpoints in the TTP’s notable resurgence in recent years. Following the Afghan Taliban’s return to power in 2021, the group has made a strong comeback, expanding its operational capacity and intensifying its violent campaign against the Pakistani state. Open-source data about TTP’s violent campaign confirms that the TTP’s violent footprint has grown significantly.4

Direct engagements or ‘battles’ between different TTP factions and the Pakistani state reveal the following numbers: Approximately 98 events were recorded in 2021;a 121 in 2022; 374 in 2023; and about 470 in 2024.b Indirect violence against civilians and other non-state targets (use of explosives, remote violence, or violence targeting civilians) reveals a parallel rise:c 26 events in 2021; 32 in 2022; 165 in 2023; and 247 in 2024. Other analysts and the TTP’s own annual data revealed comparable or higher figures; for example, Sayed and Hamming’s analysis shows that TTP’s claimed attacks increased from monthly rates of 14.5 in 2020 to 23.5 in 2021 and 45.8 in 2022.5 TTP’s own infographics claim even more drastic trends: During 2021, TTP claimed to conduct 282 attacks, 367 in 2022, 881 in 2023, and 1,758 in 2024.6 These multiple data sources collectively confirm a consistent pattern: TTP attacks have escalated sharply since 2021, to levels not seen since its prior peak years, with a particular escalation in direct confrontations with security forces.

The escalation in TTP’s violent campaigns reflects not only the group’s enhanced organizational capabilities, but also its recruitment effectiveness and cross-border networks. The Taliban’s governance in Afghanistan has provided the TTP with unprecedented strategic depth, allowing its leadership to operate with relative impunity while orchestrating attacks on Pakistani soil.7 The TTP has undergone a significant organizational metamorphosis since its formal inception in 2007,8 evolving not only in its structure and ideological articulation, but also in its patterns of operational focus. While KPK continues to serve as the epicenter of TTP-related violence, recent data reveals a geographic expansion that signals a shift in the group’s strategy as it intensifies its campaign against the Pakistani state. Balochistan maintained a secondary presence throughout the period with fluctuating but relatively low numbers (between 5-24 attacks annually), while Punjab emerged as a new theater starting in 2023 (nine attacks), with attacks rising to 19 in 2024.9 Sindh witnessed relatively fewer TTP-related incidents, with two incidents in 2023 and five in 2024, primarily in Karachi. TTP’s widening operational footprint within Pakistan, albeit subtle, indicates its intention to expand to new regions.

Understanding TTP’s multidimensional transformations and the geography of its attacks necessitates examining the human networks that enable them. The origins of TTP militants, their movement patterns, and their eventual operational deployment areas can reveal critical insights into recruitment pipelines, cross-border mobility, and the group’s ability to project power beyond traditional strongholds. An important source for understanding the contemporary evolution of TTP is the group’s own commemorative content, particularly its Rasm-e-Muhabbat (“Tradition of Love”) tribute series. These commemorative materials, disseminated through TTP’s Umar Media and affiliated channels, document the profiles of killed militants, offering insights into the organization’s human capital and infrastructure. Unlike official state reporting—which typically announces militant casualties without further detail—Rasm-e-Muhabbat entries offer rich, first-person documentation of TTP’s militant base. Each profile includes demographic characteristics such religious education/professional degrees, place of birth and death, militant rank, and death circumstances. Collectively, these profiles offer a rare empirical window into the group’s recruitment base, roles and hierarchy, and patterns of movement across Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The authors analyzed a comprehensive corpus of 615 TTP militant profiles compiled from the organization’s own martyrdom commemorative publications spanning from 2006 to early 2025. In doing so, multiple variables are systematically coded for each profile, including demographic data (education type), geographic information (province and city of birth and death), and other characteristics such as militant rank. To identify educational backgrounds, the following approach was adopted: First, all militants’ names and associated aliases (collectively referred to as titles by the authors) of the 615 militant profiles were captured into the dataset. While names were provided for all militants, aliases were listed for about 452 profiles. Next, using these titles, the authors coded a new variable ‘education type’ where either a militant’s name or alias explicitly included a term that denoted the militant’s educational background such as religious training or a professional degree. For example, profiles where titles included terms such as “Maulana,” “Qari,” “Mufti,” “Hafiz,” “Maulvi,” or “Talib”—all of which are commonly associated with madrassa training and Islamic scholarship in South Asia—were coded as religious education. Similarly, titles that referenced professional or academic degrees (e.g., “Engineer,” “Doctor”) were categorized as professional education. For profiles with no such reference in their titles, the authors coded these as ‘unknown.’ The authors did not use any additional textual or visual cues from profile narratives or framing to code education type, as such information tended to be inconsistent, ambiguous, and prone to subjective interpretation. Based on this coding strategy (relying on titles alone), all 615 profiles were coded into of the three categories (religious education; professional degree; and unknown). Overall, the authors identified educational markers for 120 out of 615 militants (approximately 20% of 615 profiles) through their titles. While this approach does not capture educational details for all profiles, it offers meaningful insights into both the educational backgrounds of TTP militants and the types of education the group chooses to emphasize across different ranks and operational roles. The fact that TTP chose to highlight religious or professional titles for only a subset of militants is itself telling: While one cannot assume that those in the ‘unknown’ category lacked education, the absence of such titles may reflect deliberate choices by TTP about which forms of education to emphasize—and/or which profiles to glorify or elevate. As such, while this approach does not allow for the development of a comprehensive profile of TTP militants educational attainments, the findings provide insights into TTP’s strategic messaging choices arounds its killed members.

It is important to note that these commemorative materials are produced primarily for propaganda purposes by the TTP and likely present a selective and idealized portrayal of militants. The profiles are likely curated by the group to shape specific narratives that serve TTP’s recruitment and legitimacy goals. As such, while valuable, this data should be interpreted cautiously. The authors use birth and death locations to estimate mobility of militants, however it is possible that these individuals worked in multiple locations or were recruited from some other place they had settled in, creating a more complex mobility pattern than the binary birth-death locations suggest. While this binary birth-death location approach cannot capture the full nuance of militants’ movements throughout their lifetimes, it nonetheless establishes important baseline patterns.

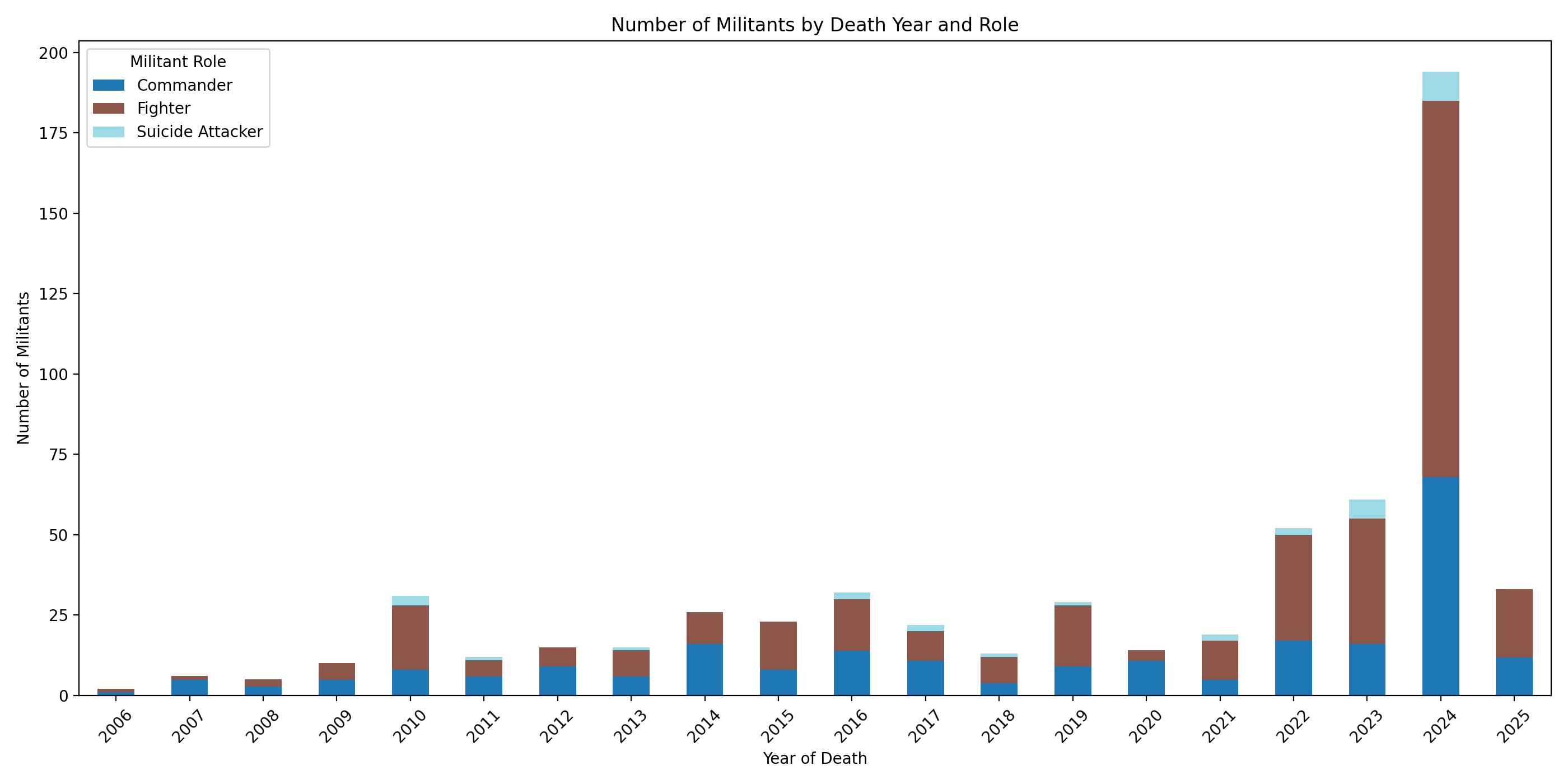

The article begins with a brief overview of TTP’s historical evolution and recent revival in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, before turning to an analysis of its militant profiles and then looking at the broader implications. Overall, the data comprises fighters (56.9%), commanders (38.2%), and suicide attackers (4.9%). The findings reveal several important trends. Among the 120 TTP militants for whom educational backgrounds could be identified through titles, religious education overwhelmingly dominates, accounting for 118 cases (98.3%). Among the 120 militants with identifiable religious or professional educational markers in their titles, nearly half were commanders (46.7%), followed by fighters (45.8%) and suicide attackers (5.8%). While this breakdown reflects the role distribution within the 120-profile subset, religious education is most frequently noted among commanders (24% of all 235 commanders) and suicide attackers (23% of all 30 suicide attackers) than among fighters (15.7% of all 350 fighters). This suggests that formal religious education may play a more significant role in facilitating leadership and martyrdom positions within the organization. Second, the data trends suggest the emergence of new activity hubs: The analysis reveals growing operational footprints in southern Punjab, urban areas of Sindh, and Balochistan. Third, the data indicates a geographical reconfiguration, with a shift away from historical bases in North Waziristan toward strategic nodes like Dera Ismail Khan—which appears to be transforming from a peripheral support zone during TTP’s formative years (2007-2013) into a critical operational hub following the Taliban’s Afghanistan.10 The analysis also suggests that most TTP suicide operatives largely belong to districts such as DI Khan, North Waziristan, Bannu, and Khyber in KPK, with emerging recruitment areas in Balochistan. Most significantly, the findings underscore increased cross-border mobility between Afghanistan and Pakistan, illuminating the cross-border dimensions of the insurgency.

The TTP’s Evolution and Resurgence

The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan emerged in December 2007 as an umbrella organization uniting previously disparate militant groups operating throughout Pakistan’s tribal areas. Under the leadership of Baitullah Mehsud, a shura (council) of 40 senior Taliban commanders established the group in response to Pakistani military operations against al-Qa`ida-affiliated militants in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA).11 The organization initially brought together militant factions primarily from the seven agencies of FATA, but also from settled areas of KPK.12 The TTP’s formation was precipitated by several factors—most importantly, by the Pakistani military’s operations in FATA in 2007—which created deep resentment among local Pashtun tribes who viewed these operations as an infringement on their autonomy.13 The 2007 siege of Lal Masjid (Red Mosque) in Islamabad, which resulted in the deaths of numerous militants and civilians, served as a galvanizing event that accelerated the formation of the insurgency.14

The TTP’s ideology draws heavily from the Deobandi school of Islamic thought, which has been influenced by both the Afghan Taliban’s approach and al-Qa`ida’s global jihadi orientation.15 Since its inception, the TTP has maintained several core objectives: removal of the Pakistani government from the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA);d enforcement of sharia law; resistance against the Pakistani military; opposition to Pakistan’s participation in the War on Terror; and support for the Taliban’s insurgency in Afghanistan.16 Over time, while these objectives have shifted, the TTP’s battle with Pakistan security forces has only grown more aggressive. Under the current leadership of Noor Wali Mehsud, the TTP has positioned itself as a movement seeking autonomy in select areas.17

The TTP has undergone several leadership transitions since its formation, each marking distinctive shifts in the organization’s strategy and operational focus. Baitullah Mehsud (2007-2009) established the TTP as a unified force opposing the Pakistani state and positioned it as an ally of both al-Qa`ida and the Taliban.18 Hakimullah Mehsud (2009-2013) succeeded Baitullah, with his tenure marked by increased operational capacity and an expansion of the TTP’s targets to include international objectives. Mullah Fazlullah (2013-2018), also known as “Radio Mullah” for his fiery sermons broadcast over FM radio in Swat Valley, marked a significant departure from the previous Mehsud tribal leadership. His appointment created deep fissures within the organization, leading to factional splits and a decline in operational cohesion.19 Under Fazlullah’s leadership, the TTP carried out some of its most notorious attacks, including the 2014 assault on the Army Public School in Peshawar that killed over 140 people, including 132 children.20 All three leaders—Baitullah, Hakimullah and Fazlullah—were killed in U.S. drone strikes.21 Noor Wali Mehsud (2018-present) returned the TTP’s leadership to the Mehsud tribe and has overseen what scholars describe as a strategic revival of the organization. A religious scholar and writer with significant jihadi experience, Noor Wali has implemented substantial reforms to TTP’s organizational structure and strategy. These include a reunification of splinter factions through a more “federal” approach to leadership while building more coherence through a centralized Taliban-style organizational/governance structure,22 avoiding indiscriminate attacks,23 and strengthening media operations to enhance the group’s public image and recruitment.24

The Afghan Taliban’s capture of Kabul in August 2021 has thus far proven to be a watershed moment for the TTP, providing it with unprecedented strategic depth and operational freedom. The release of detained members from Afghan prisons25 and reintegration of splinter factions have further accelerated its momentum,26 enabling the TTP to not only reestablish itself in former KPK strongholds but also expand into new territories in Balochistan, southern Punjab, and urban centers—a geographic extension that is likely designed to stretch Pakistani security forces thin. The tangible result has been a dramatic surge in operational tempo, with ACLED data revealing that TTP attacks increased significantly between 2021 and 2024, rising from 140 total events to 784 events across all categories, with direct confrontations with security forces increasing more than fivefold (90 to 470) and violence against civilians expanding tenfold (25 to 250).27

Analysis of Militant Profiles

The “Rasm-e-Muhabbat” (Tradition of Love) Series

As the TTP has undergone a revival under the leadership of Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, its expanded propaganda infrastructure has introduced various products including magazines in Urdu, English, and Pashto, a weekly Urdu newspaper, Nasheed (Islamic chants), press releases, video series, tribute posters, and audio and video podcasts. The media output represents a deliberate effort by the TTP leadership to curate its public image and enhance its appeal among potential recruits and sympathizers. Among these propaganda materials, the Rasm-e-Muhabbat tribute series offers particularly valuable data points for understanding TTP’s recruitment patterns, geographic mobility, and operational evolution.

The Rasm-e-Muhabbat tribute poster series features profiles of TTP militants and commanders killed on the battlefield. Each poster features a unique profile of a militant with demographic and operational details (e.g., region of birth and death, year of death), and a photograph. The materials were initially disseminated on Umar Media and TTP-associated Telegram groups in August 2023, and subsequently distributed on TTP-affiliated X (formerly Twitter) accounts. The series has evolved to encompass tribute videos and now maintains its own Telegram bot and WhatsApp channel with over 500 followers. Each poster is marked by a distinctive numeric reference number.e While the informational content and overall layout has remained consistent, variations in the released posters suggest that the Rasm-e-Muhabbat has been produced by multiple design entities instead of a centralized production team, demonstrating the evolution and dispersion of TTP’s technological capabilities within the organization.

Employing a content analysis approach, this study examines 615 poster profiles of TTP militants and commanders who were killed on the battlefield between 2006 and 2025 (February). The data corpus was systematically extracted from TTP official and associated Telegram channels, the Rasm-e-Muhabbat Telegram bot, and its WhatsApp channel. Biographical identifiers extracted included names, aliases, and geographic data captured province, birth city, and birth tehsil/district information. Educational backgrounds were coded into three categories: religious education, professional degree, and unknown. Classification was based on explicit textual references in the names or aliases of militants such as: Maulana, Qari, Hafiz, Mufti or similar identifiers, which were used to infer that the individual received a specific type of education or training. Operational contextual factors documented the month of death and death location details (city, tehsil/district, province, and country). Organizational elements included walayat (sub-group) affiliations and hierarchical position classified as fighter, commander (mid-level commander, ranking commander), or suicide bomber, identified through visual analysis and textual designations such as “Commander” or “Fidai” (suicide bomber).f

Roles: Commanders, Fighters, and Suicide Bombers

The overall rank distribution of the 615 TTP militants shows that the majority—56.9% (350 individuals)—were classified as fighters, forming the core operational segment of the group. Commanders, which include both mid-level and ranking leadership, accounted for 38.2% (235 individuals), indicating a considerable presence of tactical and strategic operatives among those killed. A smaller group—4.9% (30 individuals)—were identified as suicide bombers representing a specialized role within the organization.

Educational Background

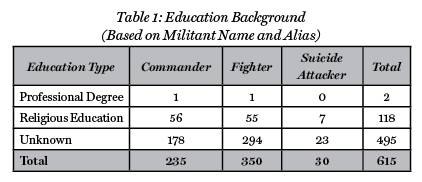

As noted above, education type was only recorded when it was referenced in the text or honorifics commonly associated with formal madrassa training or professional degrees. Table 1 shows the breakdown of these numbers, where educational background could be identified for 120 of the 615 profiles. Among these, 118 individuals (98.3%) had religious education, while two individuals (1.7%) held professional degrees. These educational patterns span TTP’s operational structure: Among those with religious education, 47.45% of the 118 served as commanders, 46.61% as fighters, and 5.9% as suicide attackers. Both individuals with professional degrees were non-suicide operatives—one a commander, the other a fighter. While this verified subset does not capture the full picture, the consistency with which religious titles appear in TTP’s commemorative literature—and the near-absence of secular educational credentials—reflects the group’s intentional cultivation of religious legitimacy. Their absence in most profiles could indicate incomplete religious training (such as madrassa students who had not yet earned formal titles), or inconsistent documentation practices in TTP’s commemorative materials.

When comparing TTP militants with explicitly stated religious/professional degree education to those without such references (the unknown category), the authors find that religious titles were more common among commanders (24% of 235) and suicide attackers (23% of 30) than among fighters (18% of 350). In other words, fighters had the highest number of titles without any clear religious education identifiers in their names or aliases. This pattern suggests that religious training may play a more prominent role in facilitating leadership and martyrdom roles—or, at the very least, deemed more important by TTP to highlight in those roles as part of its narrative strategy. In contrast, the lower proportion of religious titles among fighters may reflect a broader, more opportunistic recruitment strategy for rank-and-file roles, where religious credentials are less critical to highlight.

While education can only be captured in approximately 20% of the 615 profiles, the predominance of religious education in this subset aligns with the broader socioeconomic landscape of Pakistan’s tribal regions, where access to formal education remains severely constrained by structural inequalities, ongoing conflict, and historical marginalization.28 The presence of TTP militants with religious backgrounds (and minimal degree holders) reflects not only TTP’s targeted recruitment patterns and Islamist ideology, but also the systematic educational deprivation characterizing these regions.29 Within this context, religious seminaries often represent the only accessible educational institution, serving as both knowledge centers and social networks that can subsequently be leveraged for militant mobilization. Realizing the significance of the religious seminaries, TTP has established a religious board by the name of Tehreek ul Madaris Al Islamia under which 80 religious seminaries with more than 6,000 students are working (mostly in Afghanistan) and held its first graduation ceremony in January 2023.30

Geographical Birth & Death Locations

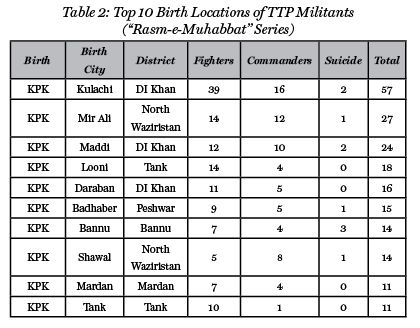

Analysis of the profiles reveals a strategic reconfiguration of TTP’s operational geography and recruitment architecture. Based on the birth locations of the TTP profiles, the organization’s primary recruitment corridors are concentrated in Dera Ismail Khan, North Waziristan, and Peshawar Districts, with particular recruitment density in the towns of Kulachi, Spinwam, Mir Ali, and Badaber, as shown in Table 2 below. These locations represent critical nodes in TTP’s human resource pipeline, functioning as both ideological incubators and operational staging grounds. These towns not only account for high numbers but also show a notable presence of leadership roles, indicating that certain localities may serve as deeper ideological or organizational hubs within the TTP’s structure. The prominence of Dera Ismail Khan (henceforth referred to as DI Khan) as a recruitment hub is particularly significant as it sits at the geographic intersection of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Balochistan provinces. While TTP activity during and after Operations Zarb-e-Azb (2014) and Raadul Fassad (2017) remained confined to the relatively isolated districts of the erstwhile FATA,31 TTP appears to be reemerging in urban centers,32 and developing networks that enable the movement of fighters, resources, and operational capabilities across provincial boundaries.

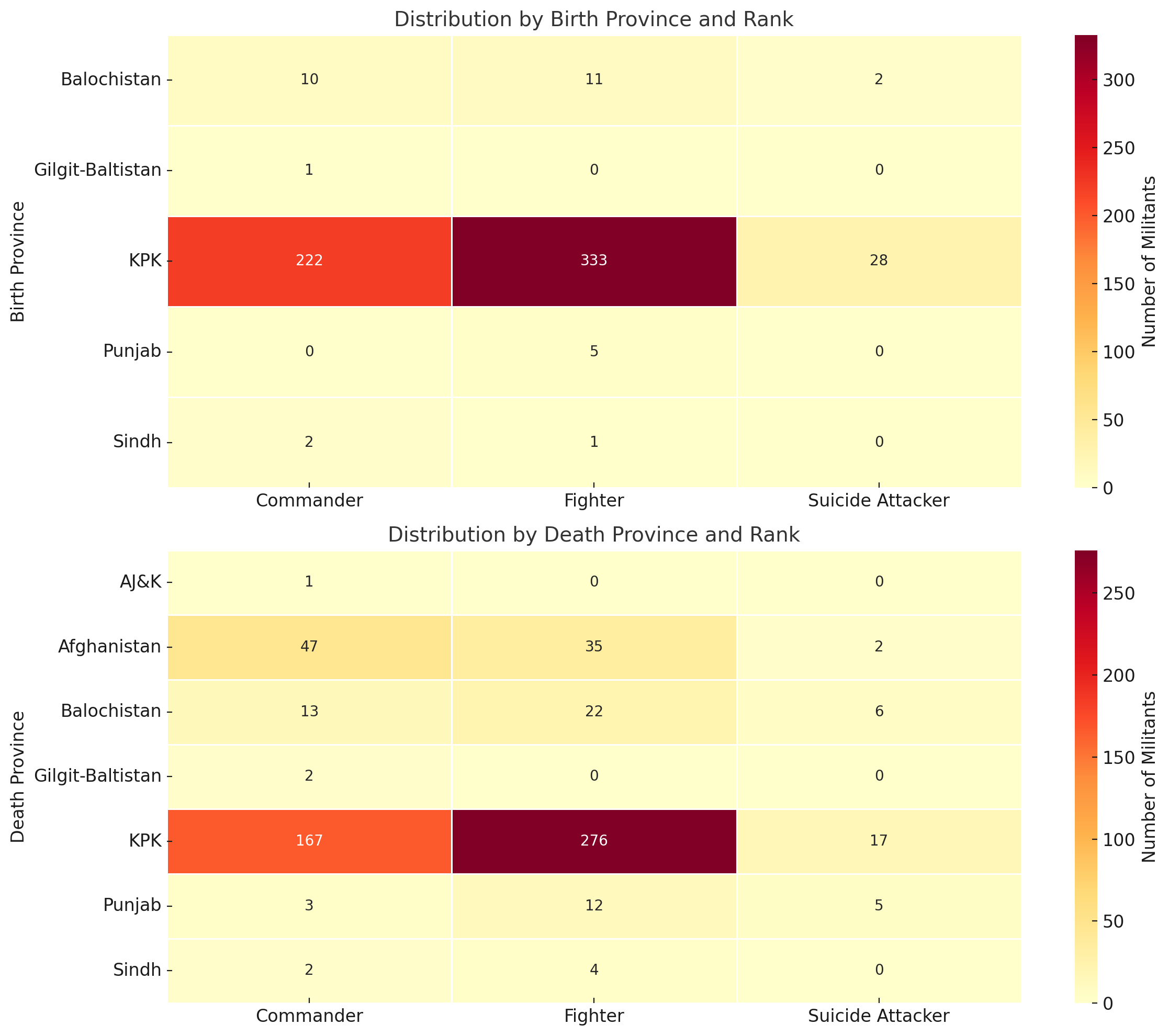

Overall, and perhaps unsurprisingly, the data reveals that TTP militants overwhelmingly originate from KPK, with over 580 individuals born in the region. Other regions like Balochistan, Punjab, Sindh, and even Gilgit-Baltistan account for only a small fraction of the birth locations. In contrast, death locations tell a different story of operational dispersal. While KPK still reports the highest number of deaths, the spread is much broader with deaths recorded in Balochistan and Punjab, and notably, in Afghanistan, despite not being a source of birth data. This geographical disparity between births and deaths indicates that TTP militants are highly mobile, often moving from their home regions to engage in activities in other parts of the country and across the border in Afghanistan. As shown in Figure 3, KPK serves as a primary source for fighters, which form the bulk of its militant population. In contrast, other provinces such as Balochistan provide a relatively balanced mix of fighters and commanders, suggesting that evolution into leadership roles may be occurring more frequently among militants who operate in or migrate to different regions. In the deaths location data, Afghanistan notably shows a higher proportion of commanders relative to fighters, suggesting that militant leadership might be more active in that operational theater.

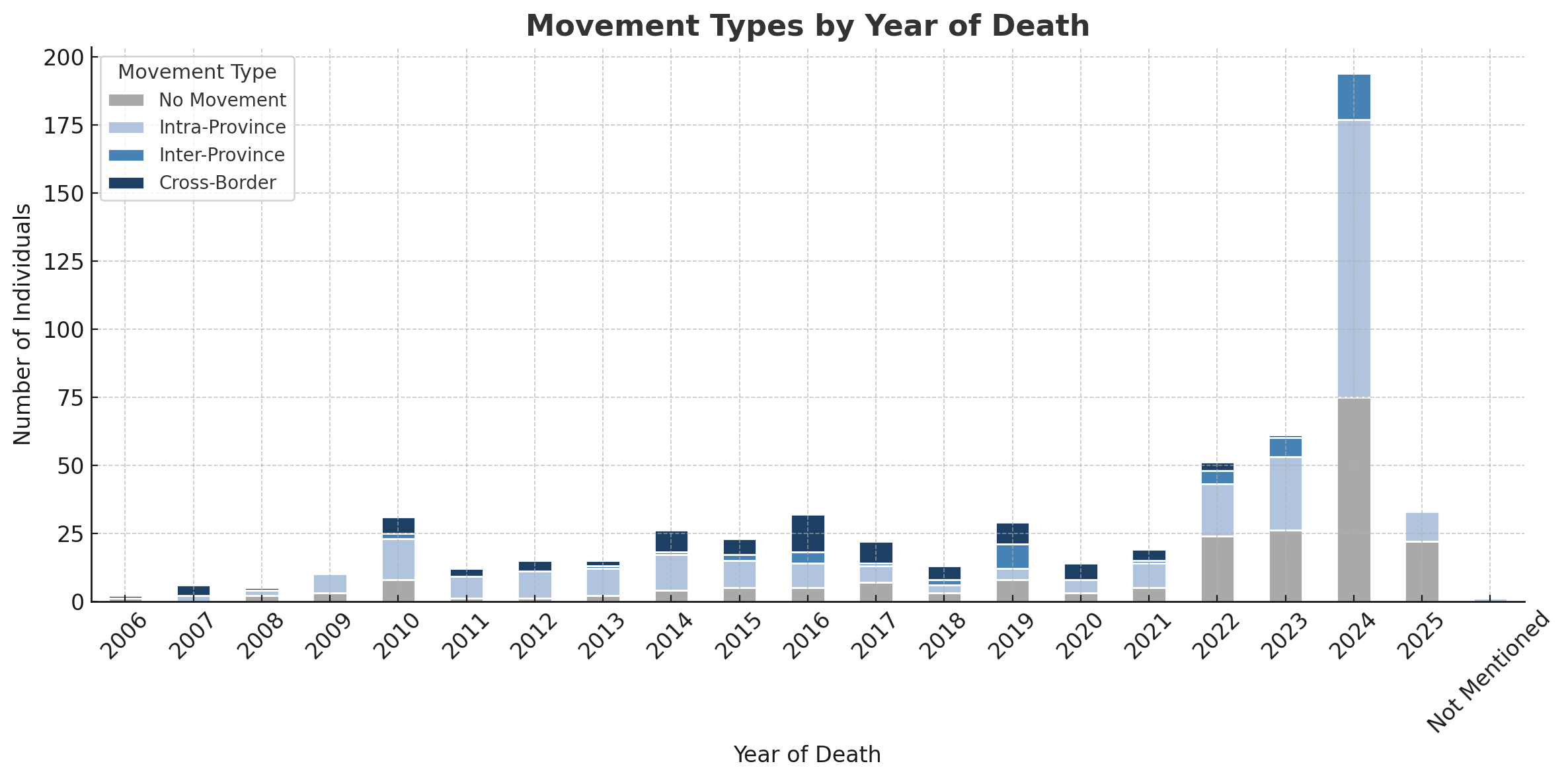

Militant Movements: Intra-province, Inter-province, and Cross-border

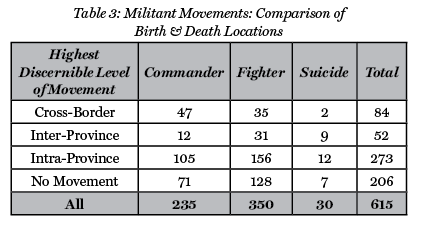

The complexity of militant movement patterns can indicate how capable an organization may be in conducting attacks that are not territorially bound—representing a more fluid, network-centric model. The mobility of militants is assessed by comparing their birth and death city/provinces, and categorizing this variable into four types: no movement (where birth/death province, city match); intra-province movement (where death/birth province match, city differs); inter-province movement (where birth/death province differ but country matches); and cross-border movement (where birth/death country differs).g As shown in Table 3, of the 615 profiles analyzed, 273 militants experienced intra-provincial movement as their highest discernible level of movement, while 52 engaged in inter-provincial mobility as their highest recorded travel reach. Cross-border movement has also been observed, involving 84 militants—from Pakistan to Afghanistan. This indicates TTP’s ability to expand beyond traditional strongholds with those who crossed borders further underscoring the group’s regional access and the use of Afghan territory as a sanctuary. In contrast, 206 individuals showed no recorded movement, suggesting localized recruitment and deployment. Commanders were most heavily represented in cross-border movements (56% of those involved in such movements), followed by intra-provincial movements (38% of those involved in this category of movements), suggesting that senior operatives play a pivotal role in both transnational operations and localized command structures. Suicide attackers were most concentrated in inter-provincial movements (17.3%), with lower percentages in other types of movements (intra-province and cross-border) and only about 3% in the no-movement category—suggesting that TTP tends to deploy these operatives across provincial lines to target high-value installations.

In general, these movement patterns appear to align with the broader organizational changes observed within the TTP post 2021. Since then, the TTP has pursued a dual approach of consolidating its fragmented factions under a more centralized command structure while simultaneously forming smaller, more agile units to maximize operational flexibility.33 The group’s internal mergers and new guidelines issued by Noor Wali Mehsud indicate a desire to exert greater control over the TTP network, which likely contributed to improved coordination of localized and cross-border operations.34 TTP’s hybrid structure of central oversight combined with decentralized, mobile units35 align with the observed militant movement trends. The concentration of commanders among the cross-border cohort is perhaps reflective of the group’s centralized coordination of cross-border activities from sanctuaries in Afghanistan, while the patterns of intra- and inter-provincial movement among fighters and suicide attackers mirror the decentralized deployment of smaller units tasked with local operations and strategic attacks across provincial lines.

KPK Recruits

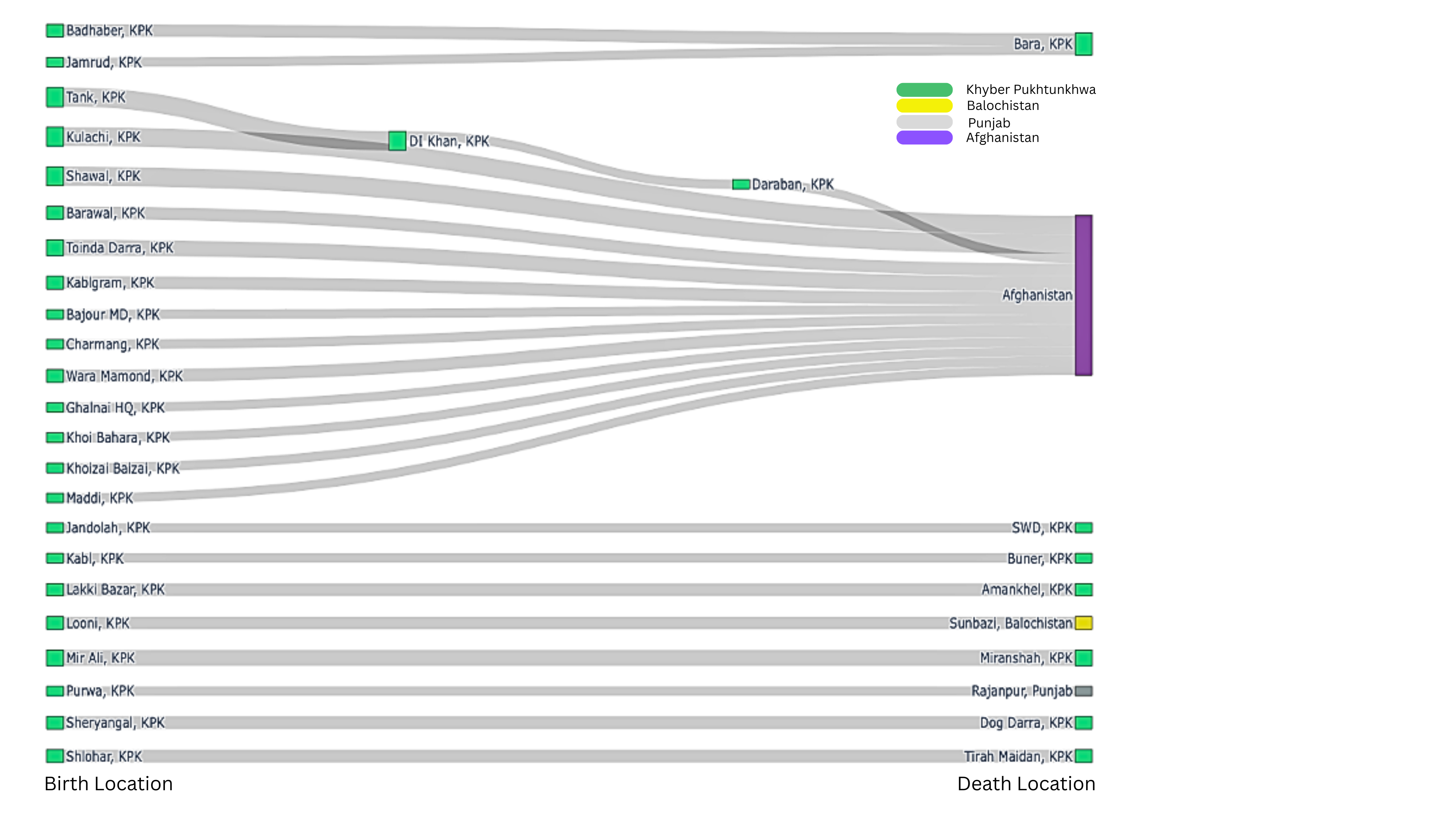

To further assess TTP militants’ movements, two Sankeyh figures were created to illustrate key inter-city and cross-border movement patterns of militants. The first figure focuses on the directional flows from areas in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa—notably cities like Bannu, DI Khan, and Bajour—to other regions within Pakistan and provinces in Afghanistan such as Kunar, Paktika, and Nangarhar. To emphasize meaningful trends, only movement paths involving three or more individuals were included in this visualization, as shown in Figure 4. The thickness of the flow lines represents the number of individuals making each journey, with thicker lines indicating prominent corridors of militant movement. The second figure (Figure 5) shows militant flows from the rest of the provinces, outside KPK.

Within Pakistan, TTP movements from KPK were most frequently directed toward Balochistan (23 cases), followed by Punjab (16 cases) and then Sindh (five cases). In examining the specific KPK-to-Balochistan routes, the analysis shows that the top origin cities and towns in KPK for these movements are Khoi Bahara (four cases) and Looni (four cases), while the main destination cities in Balochistan are Sunbazi (six cases total), Gul Kech (three cases), and Zhob (three cases). For KPK-to-Punjab movements (16 total cases), the militants primarily moved from DI Khan (KPK) to Rajanpur, Mianwali, and the urban centers of Multan and Faisalabad (Punjab), followed by militants from Bannu, Swabi, Tank (KPK) to Mianwali, Lahore, and Rawalpindi (Punjab). KPK-to-Sindh movements were less frequent (five total cases), with destinations such as Karachi (two cases), Ghotki (two cases), and Sukkur (one case).

Cross-Border Movement

Additionally, Afghanistan appears to be a destination or fallback zone for militants primarily from KPK. Among militants who died in Afghanistan—often seen as a strategic fallback or sanctuary—KPK-born individuals make up 82 of 84 cases (two from Balochistan). At the same time, within Pakistan, 455 militants who died in KPK were also born there. These patterns strongly suggest that KPK functions not only as a geographic stronghold for the TTP but also as its principal recruitment and deployment zone, enabling both internal circulation and transnational extension of militant activity. Various reports by the United Nations and security think tanks have highlighted the support provided to the TTP by the Afghan Taliban,36 which has been denied by the Afghan Taliban leadership.37 This study’s analysis of Rasm-e-Muhabbat commemorative posters provides further evidence of TTP militant presence in at least four of Afghanistan’s provinces—Paktika, Kunar, Nangarhar, and Paktiya, with militants primarily originating from DI Khan, North Waziristan, and the former Mohmand Agency in Pakistan.

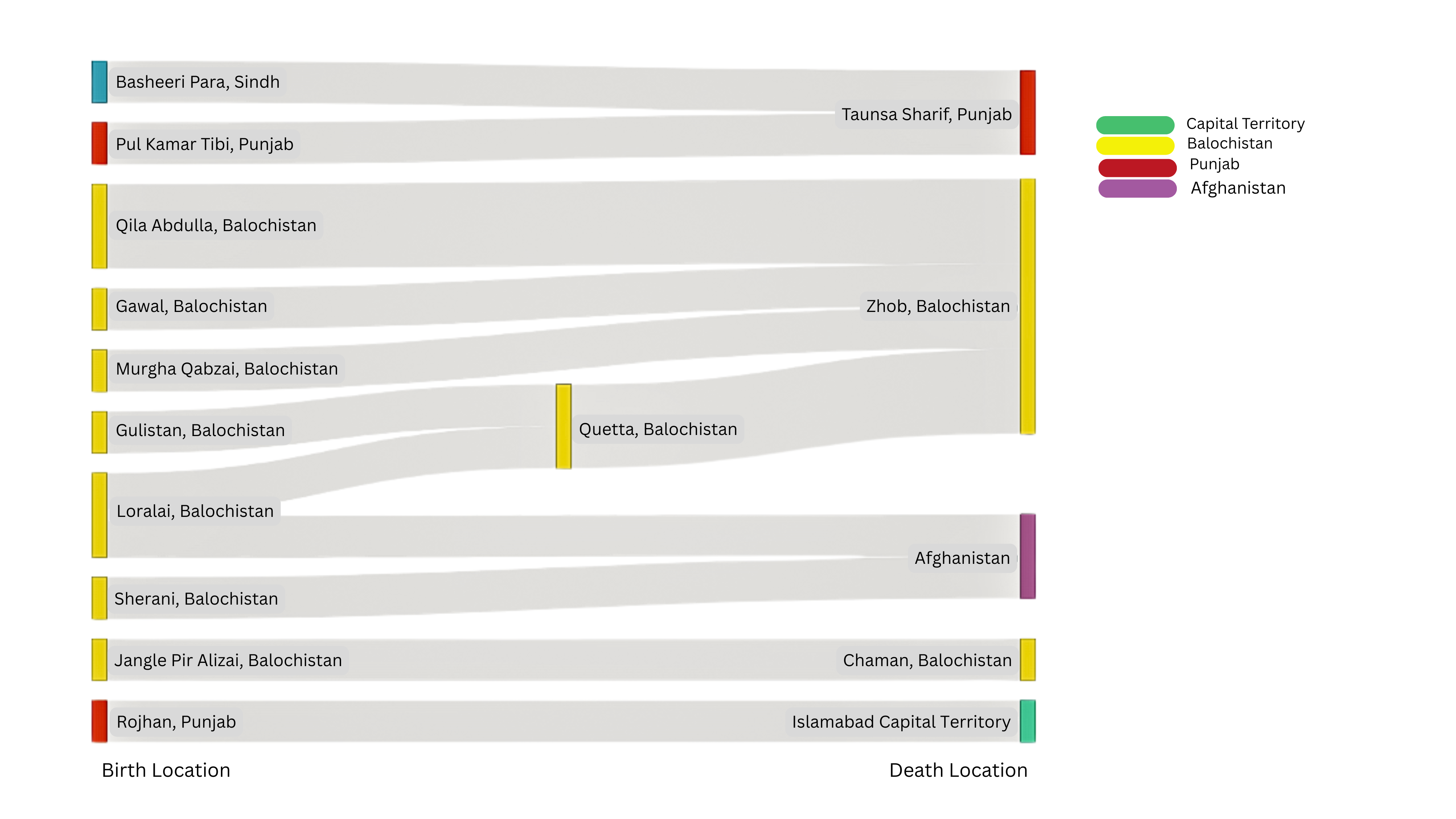

Non-KPK Recruits

As shown in Figure 5, militant movements originating from other provinces are predominantly localized. Out of Balochistan’s 23 profiles, the majority of these remained within the province, while a smaller number extend outward—three to KPK and two to Afghanistan—indicating some interregional and cross-border dynamics. Punjab- and Sindh-born militants showed limited movement: from Punjab, there was one movement to the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT), and another to KPK; from Sindh, there was one movement each to Punjab, and to KPK. These patterns suggest that, aside from Balochistan’s modest outbound flows, militant activity originating in these provinces largely remains localized, reflecting a tendency toward intra-provincial rather than interprovincial mobilization. Overall, KPK-born militants exhibit the highest degree of interprovincial mobility in the dataset, serving as the primary drivers of TTP movement across Pakistan.

Operational and Seasonal Trends

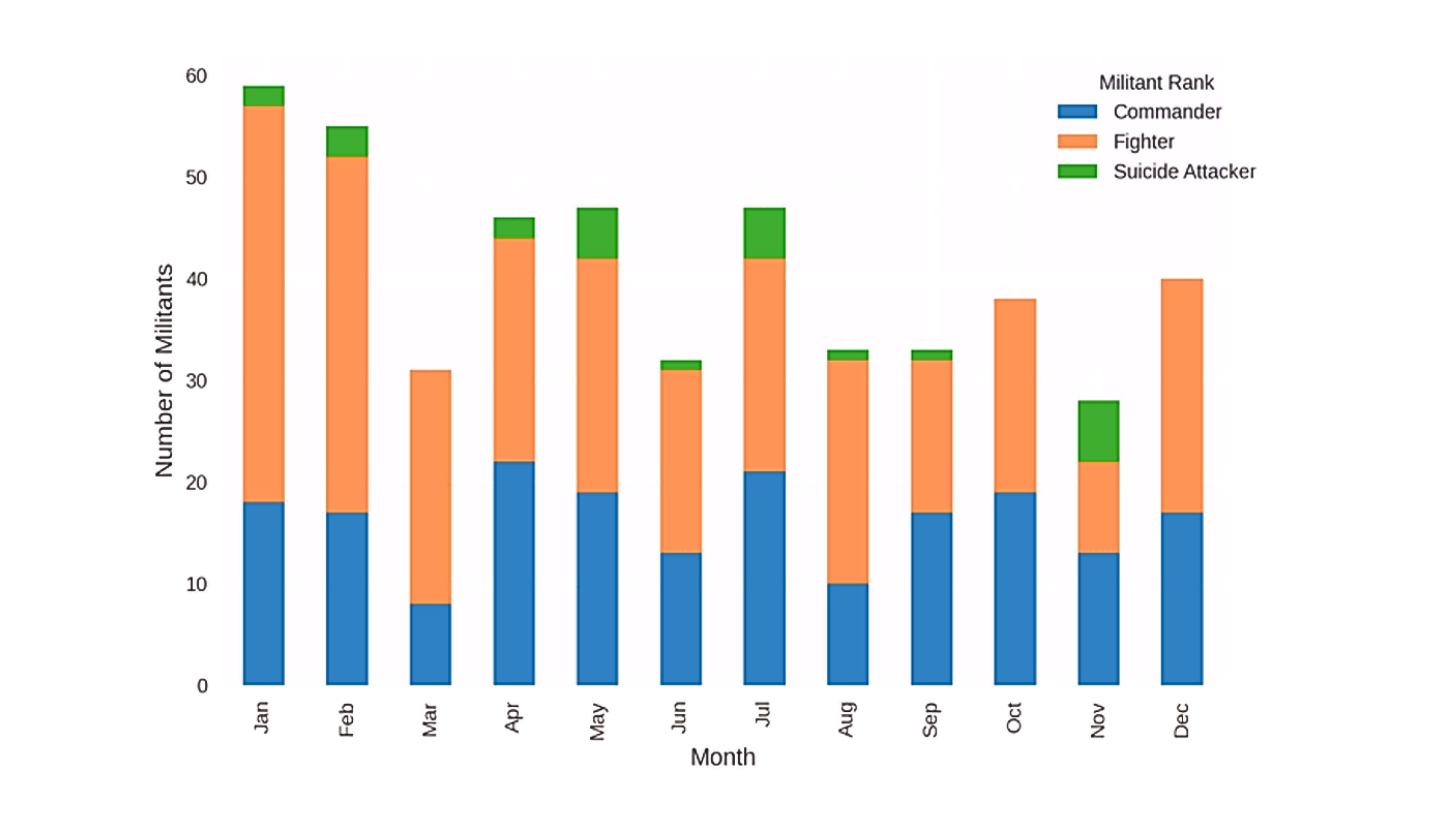

The monthly distribution of militant deaths by rank (see Figure 6) reveals consistent operational engagement throughout the year, with noticeable surges in January, February, and July. Across all months, fighters consistently represent the largest share of fatalities, underscoring their frontline role in militant operations. Commanders also show steady losses, suggesting regular targeting or exposure of mid-level leadership. Suicide attackers, while far fewer in number, appear intermittently, with small spikes in May, July, and November. The data also reveals a shift in operational patterns between 2006 and 2025. In KPK, as noted above, there has been a notable transition away from earlier strongholds such as North Waziristan District, with DI Khan district reemerging as a key operational hub, especially from 2023 onward. As noted above, while the TTP had been active in DI Khan in prior years (2007-2013), its activities in this region declined significantly post 2014; however, in recent years, DI Khan appears to have reemerged as a critical operational hub following the Taliban’s Afghanistan takeover in 2021.38 Examining data from ACLED, restricting the data to direct violent engagements between state forces and TTP, the authors find support for this observation. Between 2010 and 2020, only 24 engagements are recorded in DI Khan. However, between 2021-2024, about 140 events are recorded peaking in 2023 at 65 events. In terms of violence against civilians and other non-state targets, we find a similar pattern. While a total of 13 attacks were recorded between 2010-2020, 33 attacks were recorded between 2021 and 2024, with attacks peaking in 2024 in DI Khan at 22 attacks. This shift is accompanied by rising activity in Khyber, Tank, and Lakki Marwat in KPK.

Balochistan, which initially recorded very few operations before 2015, shows increased numbers of TTP militant deaths in several cities such as Zhob, Sunbazi, and Quetta (five deaths noted between 2010-2015; 36 between 2016-2024 with the most notable increase in 2024 at 20). This change, beginning prominently after 2016, reflects an operational transformation in the province, and appears to align with TTP’s 2016 declaration of Balochistan as its “next battlefield.”39 In Punjab, the data on militant deaths indicates a shift of operational activity toward Southern Punjab,40 particularly toward the Rajanpur and Dera Ghazi Khan districts. These patterns are likely influenced by sustained counterterrorism pressure in central Punjab’s urban hubs where earlier activity was concentrated.41 In Sindh, operational deaths showed an increase from two cases (2013-2014) to four cases (2016-2025). Furthermore, based on death locations, it appears that the TTP is attempting to grow its operational footprint in the relatively stable and settled regions of KPK and Gilgit-Baltistan, including Nowshera, Karak, Kohat, and Diamir—areas previously considered outside the group’s core zone of operations. These shifts illustrate a geographic recalibration in TTP’s strategy, aimed at dispersing its footprint and testing the state’s ability to respond across a wider terrain. The ACLED dataset (2021-2025) validates the operational trends analysis, showing both the geographic expansion and shifting patterns of TTP activity. While KPK remains the epicenter, the data confirms increased activity in Balochistan (state-TTP militants’ clashes increased from four in 2021 to 19 and 14 events in 2023 and 2024, respectively), the emergence of Southern Punjab as a new front (armed clashes increased from two in 2021 to 13 and 27 in 2023 and 2024, respectively), and limited but strategic presence in Sindh in 2024.42

Temporal Trends

Figures 7 and 8 illustrate key temporal and operational trends in TTP militant deaths based on role and movement type from 2006 to early 2025. The first figure disaggregates the number of militant deaths by role—fighter, commander, and suicide attacker per year, while the second figure categorizes militant deaths by movement type. The first figure highlights the growing share of both fighters and commanders in the TTP’s profiles for those who died after 2021, underscoring the group’s expanding manpower and perhaps the rising exposure of leadership figures in clashes with security forces, including the death of TTP commander Bali Khyara in DI Khan43 and Hafeezullah Mubariz Kochwan44 near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. The second figure shows that intra- and inter-provincial mobility increased steadily, and cross-border movements were notably concentrated between 2016 and 2019. This earlier pattern of cross-border activity is arguably one indicator that the TTP had already begun embedding networks across Afghanistan a few years prior to its resurgence in 2021.45 However, these findings must be interpreted with caution. Since the data is drawn from TTP’s own commemorative propaganda series, it likely presents a selective and idealized portrayal of the group’s activities. Earlier years, especially before 2015, are likely underrepresented due to inconsistent media production and weak organizational infrastructure, making temporal comparisons imperfect.

Broader Implications

The Rasm-e-Muhabbat profiles reveal significant organizational evolution within the TTP over time. The educational distribution across ranks indicates strategic human resource allocation, with leadership positions typically filled by marginally better-educated individuals. The dataset also reveals a calculated geographic expansion that extends well beyond TTP’s traditional strongholds in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). The shift from North Waziristan to Dera Ismail Khan district as a primary operational hub signals a strategic reorientation toward areas that facilitate cross-regional connectivity. DI Khan’s position at the intersection of KPK, Punjab, and Balochistan provides TTP with unprecedented operational flexibility and access to new recruitment pools. The documented presence in Balochistan (particularly post-2016), southern Punjab, and urban centers in Sindh demonstrates a deliberate strategy to stretch Pakistani security forces thin across multiple fronts.

This geographic diversification serves multiple objectives: complicating counterterrorism operations, embedding the organization in more densely populated regions with greater resource accessibility, and facilitating recruitment across a wider demographic base. The cross-border movement patterns, particularly into Afghanistan’s Paktika, Kunar, Nangarhar, and Paktiya provinces, further underscore TTP’s cross-border operational framework and its ongoing, more than a decade-long, strategic exploitation of the porous Afghanistan-Pakistan border. The educational profile with religious education dominating the identifiable cases suggests that TTP’s recruitment strategies likely exploit regions with limited formal schooling.46 The concentration of recruitment in specific localities such as Kulachi, Mir Ali, and Badaber points to deep localized networks that facilitate continued replenishment of militant ranks despite ongoing security operations.

Potential Vulnerabilities in TTP’s Operational Model

Despite its resurgence, the TTP’s operational model reveals several exploitable vulnerabilities. First, its heavy reliance on specific geographic recruitment corridors (particularly DI Khan, North Waziristan, and Peshawar districts) creates opportunities for targeted counter-recruitment initiatives. Focused socioeconomic development and educational programs in these areas could potentially disrupt TTP’s human resource pipeline, especially in the long-term, as they can reinforce civilian populations resilience to extremism. However, education quality and content matters, rather than just years of schooling. As Afzal’s study of Pakistan shows, higher education levels correlate with less favorable views of extremist groups, suggesting that expanding quality education access could gradually reduce the pool of potential recruits. However, this requires meaningful changes in educational curricula where it is carefully designed to foster an inclusionary identity and tolerance.47 Second, the group’s leadership structure appears potentially vulnerable to disruption, with commanders making up 38.2% of deaths in the dataset. This vulnerability is especially pronounced due to the decentralized operational structure of TTP divided into smaller units called “Wilayahs,”i despite centralized command and control. However, the TTP’s sustained operational tempo despite these leadership losses indicates significant contingency planning and organizational adaptability, likely reinforced through its recent mergers, structural reorganization, and expanded media infrastructure.

Third, the seasonal patterns in militant deaths indicate operational rhythms that security forces could exploit. The notable surges in January, February, and July suggest potential planning cycles or operational windows that could be anticipated and countered. Finally, the group’s expansion beyond its traditional ethnic Pashtun base into more diverse regions may strain its ideological coherence and organizational culture.48 As TTP attempts to incorporate recruits from different ethnic, linguistic, and social backgrounds, it may face internal tensions that could be leveraged to promote defections or splinter group formation.

Implications for Pakistani Security Forces

For Pakistani security forces, the data highlights several critical challenges. First, the geographical dispersal of TTP operations necessitates a counterterrorism approach, which is broad and multipronged yet carefully coordinated, taking into account provincial-level characteristics.49

The group’s expansion into Balochistan50 and southern Punjab51 alongside its continued stronghold in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, underscores the urgent need for comprehensive inter-provincial security coordination. Historically, Pakistan’s counterterrorism efforts have faced challenges due to fragmented inter-agency communication, lack of resources, and inconsistent policy execution.52 The urgency of this coordination is underscored by current political polarization in the country and divisions between the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf-led KPK government and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N)-led federal government.53 These tensions have manifested in competing policy approaches; for example, the KPK government’s decision in February 2025 to form a provincial jirga to negotiate with the Taliban was denounced as a “direct assault on the federation” by federal officials, rejecting the KPK government’s negotiation plans again in 2025.54 Similar discord has been observed in KPK Chief Minister Ali Amin Gandapur’s challenge to the Afghan refugee expulsion policy and resistance to purely military-focused counterterrorism without concurrent development commitments.55 These disagreements occur against the backdrop of Pakistan’s deteriorating security environment, with rising levels of terrorism in part attributed to the failed 2022 negotiations with the TTP.

Recent institutional initiatives—such as the establishment of the National Intelligence Fusion and Threat Assessment Centre (NIFTAC),56 the Provincial Intelligence Fusion and Threat Assessment Centers (PIFTAC), and the revival of the Peshawar Safe City Project57—are in the authors’ view steps in the right direction toward enhancing real-time intelligence sharing and localized threat response. However, the effectiveness of these reforms will ultimately depend on sustained political will, resource commitment, and the ability to operationalize intelligence into proactive, on-the-ground counterterrorism measures across provincial lines. Historically, Pakistan’s counterterrorism efforts have faced challenges due to fragmented inter-agency communication, lack of resources, and inconsistent policy execution.58 Ensuring that initiatives like NIFTAC and the Safe City Projects are not only fully operational but also effectively integrated into the broader security framework is crucial.

Second, the geographic patterns (based on birth and death locations), along with available educational background of TTP militants suggests that military operations alone are unlikely to provide a sustainable long-term solution. Among the 120 profiles with identifiable educational data—representing approximately 20% of the sample—religious education overwhelmingly dominates, with commanders and suicide attackers more frequently represented in the subset (as a proportion of their overall numbers in the dataset), compared to fighters. This suggests that madrassa-based training likely plays a prominent role in shaping both leadership pathways and ideologically symbolic roles within TTP. Additionally, birth location data is heavily concentrated in underdeveloped areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, particularly in and around Dera Ismail Khan and North Waziristan. (See Table 2.) According to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Education Sector Plan (ESP) 2020–25, these areas face significant challenges in access and equity in education, especially in the newly merged districts with KPK.59 In such educationally disadvantaged regions where literacy rates remain low,60 religious seminaries often represent the only feasible educational pathways.61 This represents a structural reality that likely facilitates TTP’s recruitment and influence among populations with limited exposure to non-religious education and potentially high susceptibility to ideological influence.62 Without addressing fundamental socioeconomic grievances and public education deficits in affected regions, security forces will likely face a perpetual regeneration of militant ranks.

While Pakistan’s counterterrorism approaches have historically been dominated by militarized responses, it recently approved the National Prevention of Violent Extremism (NPVE) Policy in December 2024, which introduces a “5-R” approach of revisit, reach out, reduce, reinforce, and reintegrate.63 Again, the effectiveness of this new approach will depend on how well it can be integrated within existing security frameworks and commitment of state resources. Third, the cross-border movement patterns, particularly the significant number of commanders deaths in Afghanistan highlight the limitations of purely domestic counterterrorism approaches. Effective containment of TTP will require diplomatic engagement with Afghanistan’s Taliban government to address sanctuary issues, notwithstanding the Taliban’s public denials of support for TTP.64 This regional dimension of the insurgency necessitates a coordinated approach that acknowledges the porous nature of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border and the historical connections between militant groups operating across this frontier.

As the authors’ analysis of TTP militant profiles suggests, the organization appears to have developed a resilient insurgent infrastructure through what may be strategic recruitment patterns, deliberate exploitation of educational disparities, and calculated cross-border mobility. Confronting this multifaceted challenge demands moving beyond conventional security paradigms toward a combination of kinetic and governance-oriented interventions. For example, precision leadership targeting operations should be coupled with educational investments, community resilience building, and cross-border security cooperation that acknowledges the TTP’s cross-border militant mobilization. The demographic and geographic patterns uncovered in this study illuminate potential pressure points for calibrated counterterrorism/insurgency measures. These include targeting emerging militant hotspots to disrupt recruitment pipelines while strengthening cross-provincial intelligence integration along key mobility routes. A multidimensional strategy, informed by granular understanding of militant networks, can help Pakistani authorities be more effective in countering the evolving threat that TTP represents today. CTC

Saif Tahir is a policy researcher with expertise in analyzing jihadi propaganda narratives, currently a PhD student at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. His research focuses on analyzing jihadi propaganda, tactical and operational narratives, and the militant landscape across Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Amira Jadoon is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Clemson University. She specializes in international security, terrorism and violent extremism, and the strategic dissemination of disinformation.

© 2025 Saif Tahir, Amira Jadoon

Substantive Notes

[a] Based on ACLED, the authors restricted the data to events where ‘actor 1’ was recorded as a TTP faction (engaged in armed clash with state forces). The authors did not include TTP’s engagements with other rebel groups or militias.

[b] In terms of indirect violent engagements with state forces (use of explosives, remote violence) 25 events were recorded in both 2021 and 2022; 77 in 2023; and 64 in 2024.

[c] Based on ACLED, the authors restricted the data to events where a TTP faction was noted as ‘actor 1’ and event type included various types including direct attacks through gunfire; suicide attacks; use of explosives, landmines, IEDs; as well as abductions. The authors did not include attacks on other rebel groups or militias to separate inter-group conflict.

[d] Post-2021, the group has revised its territorial goals to be more pragmatic, limited to control of the regions along the Afghan border. See Abdul Sayed and Tore Hamming, “The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan After the Taliban’s Afghanistan Takeover,” CTC Sentinel 16:5 (2023).

[e] If the reference numbers indicate release order, markings from March 2025 suggest TTP has produced over 844 to date. However, methodical examination reveals inconsistencies, including instances where identical reference numbers were assigned to distinct posters, indicating potential data fabrication or systematic numbering errors.

[f] The term “Fidai” comes from Arabic and Persian roots meaning “one who sacrifices.” In TTP’s usage, a “Fidai” may conduct various types of self-sacrificing operations beyond just suicide bombings, including high-risk guerrilla attacks, targeted assassinations, and operations where escaping alive is unlikely. See N. S. Jamwal, “Terrorists’ Modus Operandi in Jammu and Kashmir,” Strategic Analysis 27:3 (2003).

[g] As noted in the methodology, the authors’ binary birth-death location approach does not capture the full mobility patterns of TTP militants’ movements throughout their lifetimes, but it helps establishes baseline patterns.

[h] A Sankey diagram is a flow diagram used to visualize the movement or distribution of elements between different stages or categories. The Sankey diagrams in this study illustrate militant mobility between birth and death locations, created with Python.

[i] Wilayahs are the district level administrative structures created by the TTP taking inspiration from Tehrik-i-Taliban Afghanistan. A wilayah typically includes administrative and intelligence heads followed by other officials including in charge of defense, political affairs and so forth that are appointed by the TTP leadership/Shura council. See “Inspired by Afghan Taliban, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) creates administrative structure, names Pakistani districts as Wilayats, appoints governors and intelligence chiefs,” MEMRI Jihad and Terrorism Threat Monitor, March 1, 2022.

Citations

[1] “2 Suicide Bombers Attack Pakistan Police and Government Compound, Killing 4 and Injuring 11,” Associated Press, July 20, 2023.

[2] “Suicide Bomber Attacks Security Convoy In Northwestern Pakistan, Killing Nine Soldiers,” Radio Free Europe, August 31, 2023.

[3] “At Least 8 Pakistani Soldiers Killed in Military Base Suicide Attack,” Al Jazeera, July 16, 2024; “Deadly attack rocks Pakistan military base,” CNN, March 4, 2025.

[4] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) dataset, retrieved February 2025.

[5] Abdul Sayed and Tore Hamming, “The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan After the Taliban’s Afghanistan Takeover,” CTC Sentinel 16:5 (2023).

[6] Tehrik-i-Taliban infographics showing annual aggregate numbers, disseminated via Telegram.

[7] Abdul Sayed and Amira Jadoon, “Understanding Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan’s Unrelenting Posture,” Program on Extremism, George Washington University, August 16, 2022; Vanda Felbab-Brown, “The Taliban’s Three Years in Power and What Lies Ahead,” Brookings Institution, August 14, 2024.

[8] Amira Jadoon and Abdul Sayed, “The Pakistani Taliban is reinventing itself,” 9Dashline, October 28, 2021.

[9] “Pakistan: Conflict Dashboard.”

[10] “Pakistan: Terrorists’ Torment in Dera Ismail Khan – Analysis,” Eurasia Review, November 21, 2023; “Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan Regions Facing Frequent Attacks in Northwest Pakistan,” ANI News, January 7, 2023.

[11] Abdul Sayed and Tore Hamming, “The Revival of the Pakistani Taliban,” CTC Sentinel 14:4 (2021): p. 29.

[12] Hassan Abbas, “A Profile of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan,” CTC Sentinel 1:2 (2008).

[13] Shahzad Akhtar and Zahid Shahab Ahmed, “Understanding the Resurgence of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan,” Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 16:3 (2023): pp. 285-306.

[14] Amira Jadoon, “The Evolution and Potential Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan,” United States Institute of Peace, Special Report 494, May 2021.

[15] See, for example, Dietrich Reetz, “The Deoband universe: What makes a transcultural and transnational educational movement of Islam?” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27:1 (2007): pp. 139-159; Muhammad Qasim Zaman, “Tradition and authority in Deobandi madrasas of South Asia” in Robert W. Hefner and Muhammad Qasim Zaman eds., Schooling Islam: The culture and politics of modern Muslim education (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), pp. 61-86.

[16] Jadoon, “The Evolution and Potential Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan.”

[17] Antonio Giustozzi, “The Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan,” Royal United Services Institute, August 12, 2021.

[18] Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Guardians of God: Inside the religious mind of the Pakistani Taliban (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[19] Ibid.; Amira Jadoon and Sara Mahmood, “Fixing the Cracks in the Pakistani Taliban’s Foundation: TTP’s Leadership Returns to the Mehsud Tribe,” CTC Sentinel 11:11 (2018).

[20] Saira Ali and Umi Khattab, “Reporting terrorism in Muslim Asia: the Peshawar massacre,” Media International Australia 173:1 (2019): pp. 108-124.

[21] Jadoon, “The Evolution and Potential Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan.”

[22] Abdul Sayed, “Analysis: How Are the Taliban Organized?” Voice of America, September 5, 2021.

[23] Jadoon and Sayed, “The Pakistani Taliban is reinventing itself.”

[24] Kabir Taneja, “A Revival of Online Terror Propaganda Ecosystems in Afghanistan and Pakistan,” GNET, November 6, 2023; Johsua Bowes, “Telegram’s Role in Amplifying Tehreek-i-Taliban’s Umar Media Propaganda and Sympathizer Outreach,” GNET, January 30, 2024.

[25] “Pakistani Taliban video welcomes prisoners released in Afghanistan,” BBC Monitoring, August 25, 2021.

[26] Sayed and Hamming, “The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan After the Taliban’s Afghanistan Takeover.”

[27] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) dataset, retrieved February 2025; Mantasha Ansari, “Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) Attacks In Pakistan More Than Tripled Between 2021 And 2023, Following Taliban Takeover Of Afghanistan,” MEMRI, January 19, 2024.

[28] Wisal Yousafzai, “K-P fails to improve access to schooling,” Express Tribune, February 24, 2025.

[29] See Peter W. Singer, “Pakistan’s madrassahs: Ensuring a system of education, not jihad,” Brookings Institution, November 1, 2001; Khyber Pakhtunkhwa program document, Global Partnership for Education, September 2021.

[30] Samri Backup, “TTP announced the graduation ceremony of 31 students at ‘Manba Al-Uloom’ madrassa …,” X, January 14, 2023.

[31] Naeem Asghar, “Terrorist incidents drop 21% in 2018: Nacta,” Express Tribune, April 7, 2019.

[32] Abdul Basit, “Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan ingress into Punjab: Prospects and challenges,” Diplomat, May 28, 2024.

[33] See Jadoon and Mehmood, “Fixing the Cracks in the Pakistani Taliban’s Foundation; Amira Jadoon and Abdul Sayed, “The Pakistani Taliban Is Reinventing Itself,” South Asian Voices, Stimson Center, November 15, 2021; Sayed and Hamming, “The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan After the Taliban’s Afghanistan Takeover.”

[34] Ibid.

[35] Sayed and Hamming, “The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan After the Taliban’s Afghanistan Takeover.”

[36] See “Thirty-fifth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2734 (2024) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” United Nations Security Council, December 30, 2024.

[37] “UN: Afghan Taliban Increase Support for Anti-Pakistan TTP Terrorists,” Voice of America, June 14, 2024; “The challenge to Islamabad from the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, January 17, 2024; “TTP a matter Pakistan must take up: Taliban spokesman,” News International, August 29, 2021.

[38] “Pakistan: Terrorists’ Torment in Dera Ismail Khan – Analysis;” “Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan Regions Facing Frequent Attacks in Northwest Pakistan.”

[39] Saif ur Rehman Tahir, “A study of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) social media communication: Major trends, key themes and propaganda appeals,” Pakistan Journal of Terrorism Research II:I (2020).

[40] “Pakistan’s Punjab Police arrest 20 alleged terrorists linked with TTP,” Business Standard, March 1, 2025.

[41] Imran Gabol, “10 terrorists arrested as Punjab CTD conducts 73 operations,” Dawn, March 8, 2025.

[42] Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) dataset, retrieved February 2025.

[43] “Most wanted terrorist Iqbal alias Bali Khyara killed in police encounter,” 24 News HD, May 4, 2023.

[44] Fidel Rahmati, “Senior TTP commander killed in Pakistan border operation,” Khaama Press, April 12, 2025.

[45] Info_Tracks, “#Breaking Key TTP Commander Yasir Parakay from Hafiz Gul Bahadar has been killed along with …,” X, August 23, 2022.

[46] Singer.

[47] See Madiha Afzal, “Pakistan Under Siege: Extremism, Society, and the State,” Brookings Institution Press, 2018.

[48] Basit.

[49] Sibra Waseem, “Global Terrorism Index 2025: A wake-up call for Pakistan’s counterterrorism gaps,” Modern Diplomacy, March 30, 2025.

[50] Zia Ur Rehman, “Pakistani Taliban move into new territories,” Deutsche Welle, March 5, 2023.

[51] “Terrorists attack police check post with rocket launchers in DG Khan,” Geo News, February 1, 2025.

[52] Tariq Parvez, “Revamping Nacta,” Dawn, January 14, 2023; “Revisiting Counter-terrorism Strategies in Pakistan: Opportunities and Pitfalls,” Crisis Group, January 18, 2018; “Revisiting Counter-terrorism Strategies in Pakistan: Opportunities and Pitfalls,” Asia Report No. 271, International Crisis Group, July 22, 2015.

[53] Usama Nizamani, “Political Cooperation Can Stem the Resurgent Threat of Militancy in Pakistan,” South Asian Voices, April 2, 2024.

[54] “K-P CM’s call to talk with Afghanistan an attack on federation: Defence Minister,” Express Tribune, September 12, 2024; Setara Qudosi, “Pakistan’s federal government rejects provincial plan to negotiate with Taliban,” AMU TV, February 2, 2025.

[55] Amira Jadoon, “The Untenable TTP-Pakistan Negotiations,” South Asian Voices, June 24, 2022; “Gandapur criticises govt’s Afghan policy,” Express Tribune, March 17, 2025.

[56] “PM inaugurates National Intelligence Fusion & Threat Assessment Centre,” Radio Pakistan, May 6, 2025; “Nacta to run new intel coordination, threat center,” Dawn, April 8, 2025.

[57] Rijab Sohaib, “Deadline Announced for Completion of Peshawar Safe City Project,” Propakistani, April 23, 2025.

[58] Parvez; “Revisiting Counter-terrorism Strategies in Pakistan: Opportunities and Pitfalls,” International Crisis Group, January 18, 2018.

[59] Global Partnership for Education, “Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Education Sector Plan 2020–2025,” Government of Pakistan and UNICEF, September 2022; Ayaz Gul, “Millions of Children in Restive Pakistani Province Lack Access to Education,” Voice of America, April 27, 2017.

[60] “Survey paints bleak picture of literacy in tribal districts,” Dawn, August 30, 2021.

[61] Peter W. Singer, “Pakistan’s Madrassahs: Ensuring a System of Education not Jihad,” Brookings Institution, November 1, 2001.

[62] Diaa Hadid, “Pakistan Wants To Reform Madrassas. Experts Advise Fixing Public Education First,” NPR, January 10, 2019.

[63] Abid Hussain, “Can Pakistan’s new anti-extremism policy defeat rising armed attacks?” Al Jazeera, February 25, 2025.

[64] Tahir Khan, “Pakistan envoy hails Pak-Afghan coordination body revival after 15-month gap with new talks,” Dawn, April 16, 2025.

Skip to content

Skip to content