Abstract: The persistent narrative of ‘jihadi brides’ traveling to Islamic State territory mostly out of a desire for love and adventure has oversimplified understanding of the motivations of an important demographic of the group’s members: women. A recently acquired log book from a guesthouse in Syria, however, provides important/revealing information about 1,100 females who transited the location over the course of four months. Analysis of the females’ ages, marital status, countries of origin, and other data points from the log book provides an empirical data point suggesting a diverse array of motivations of women who traveled into the Islamic State and contextualizes these findings for practitioners in the counterterrorism field.

The story is certainly worthy of headlines. Young women, wooed by the promise of adventure and romance in a faraway land, evade concerned parents to travel to meet their future spouses, who happen to be members of a terrorist organization. This narrative of young Western females joining and supporting the Islamic State has been supposed by well-publicized cases of young women either attempting to join or successfully joining this organization.1

But how representative are these stories of the broader phenomenon of female participation in the Islamic State? And if the narrative of jihadi brides is not accurate but remains in place, what are the potentially negative impacts on counterterrorism and deradicalization efforts around the world? While an authoritative and final answer to these questions is beyond what this article can offer, it does endeavor to provide an additional data point that calls into question the narrative of women attracted to the Islamic State simply because they were love-struck teenagers hopelessly duped by Islamic State Casanovas. To do this, it examines data on women traveling through Islamic State territory to see if, at a descriptive level, the data supports or undermines this narrative.

First, the authors briefly highlight how the Islamic State’s call to build a caliphate created a demand for migration to the conflict zone, not just on the part of military-aged males, but of females as well. Second, they present unique data taken from the battlefield in Syria, in the form of a guesthouse registry that covers a period of four months over an unspecified year and contains over 1,100 entries of females, with basic demographic information about themselves.a Third, the authors discuss the counterterrorism and policy implications arising from the examination of this unique data source.

The Call to Build a Caliphate: Not Gender Specific

In June 2014, the spokesperson for what was then known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, declared that the group had met the requirements to establish the caliphate. The group’s name consequently changed to the Islamic State. With this announcement, al-Adnani not only called for the pledging of loyalty to the new state, but extended an invitation to come and live in it.2

Days later, the leader of the Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, made a special plea to a wide range of professionals, from doctors to engineers, to join the state as well.3 What quickly became clear was that this call to come, targeted as it may have been to attract certain individuals and skillsets, was having a broader impact than ever may have been intended—the recruitment and travel of female respondents to the Islamic State’s territory in Iraq and Syria. To further encourage travel to the conflict zone, the group created a campaign to facilitate this process, complete with how-to manuals to help would-be travelers, daily logs illustrating the lives of females in the caliphate, and training documents to help prospective citizens understand how to cook, handle weapons, and perform other tasks.4

Beyond understanding what steps the Islamic State was undertaking to increase the number of females traveling into its territory, researchers also began to examine the demographics of this group of females. This task was made difficult by the fact that robust sources of data on these female travelers was not available. However, within the confines of that limitation, these early research efforts highlighted a variety of factors that explained the decision of females to travel to the conflict zone, ranging from a desire to contribute to the caliphate to a desire to find companionship with like-minded individuals to outright coercion by family members and acquaintances.5

However, despite this emphasis on the diversity of reasons for female travel to the conflict,b the story of “jihadi brides” quickly became the focus of much of the public discussion.6 In addition to being poorly informed by the research that did exist, the emphasis on jihadi brides also demonstrated the dangerous habit of “analysis by anecdote,” of which one of the most damaging side effects is the possibility that such perspectives hold sway with policymakers and practitioners charged with dealing with the problem. As one scholar put it, the focus on jihadi brides makes the development of counterterrorism measures difficult because “women are often active participants in Islamic State operations rather than just vulnerable, young girls lured with the promise of romance.”7

These challenges aside, the scope and size of the phenomenon is also something that has not been covered. Although various research efforts have identified a wide range of countries from which the more than 40,000 foreign fighters have originated, very little has been said about the number of women who have transited into Iraq and Syria. One publication in January 2015 put the number at over 550 Western women, while another placed the number of Western women as high as 1,000.8 Another scholar was quoted in May 2017 as saying that the number of Tunisian women that joined the Islamic State was 700, though it is unclear if all of those had traveled to Iraq and Syria.9 Regardless of the actual number, it seems clear that there is a dearth of primary source information on the potential scale of the challenge as it relates to women and the Islamic State.

The Data

This article presents a look at a unique set of data that provides greater insight into some of the issues raised above. This data was obtained in Syria and shared by the U.S. Department of Defense with the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) at West Point.c The source material was a large number of pages from a notebook. Each page contained printed Arabic headers for each of the columns, as well as handwritten entries across the rows of each page. The handwritten entries were in Russian.

Before examining what this series of guesthouse logs show, it is important to recognize that they are not without limitations. Perhaps the most obvious is that the data utilized in this article does not allow the authors to paint a clear picture of what these women were doing in Syria, other than that they stayed at a guesthouse operated by the Islamic State. The documents are much more a snapshot that allows a quick look at the movement of women in, around, and out of Syria.

Another limitation is that this data, other than by implication, does not allow the authors to answer the ‘why’ question when it comes to the travel of these women. Some may have been committed, others may have been coerced, and others may have been wandering. Indeed, each of these motivations finds some support in the many interviews and reports that been written about female travel into the territory controlled by the Islamic State. Unfortunately, this data does not offer any concrete way of distinguishing between these possibilities.

The Guesthouse Log

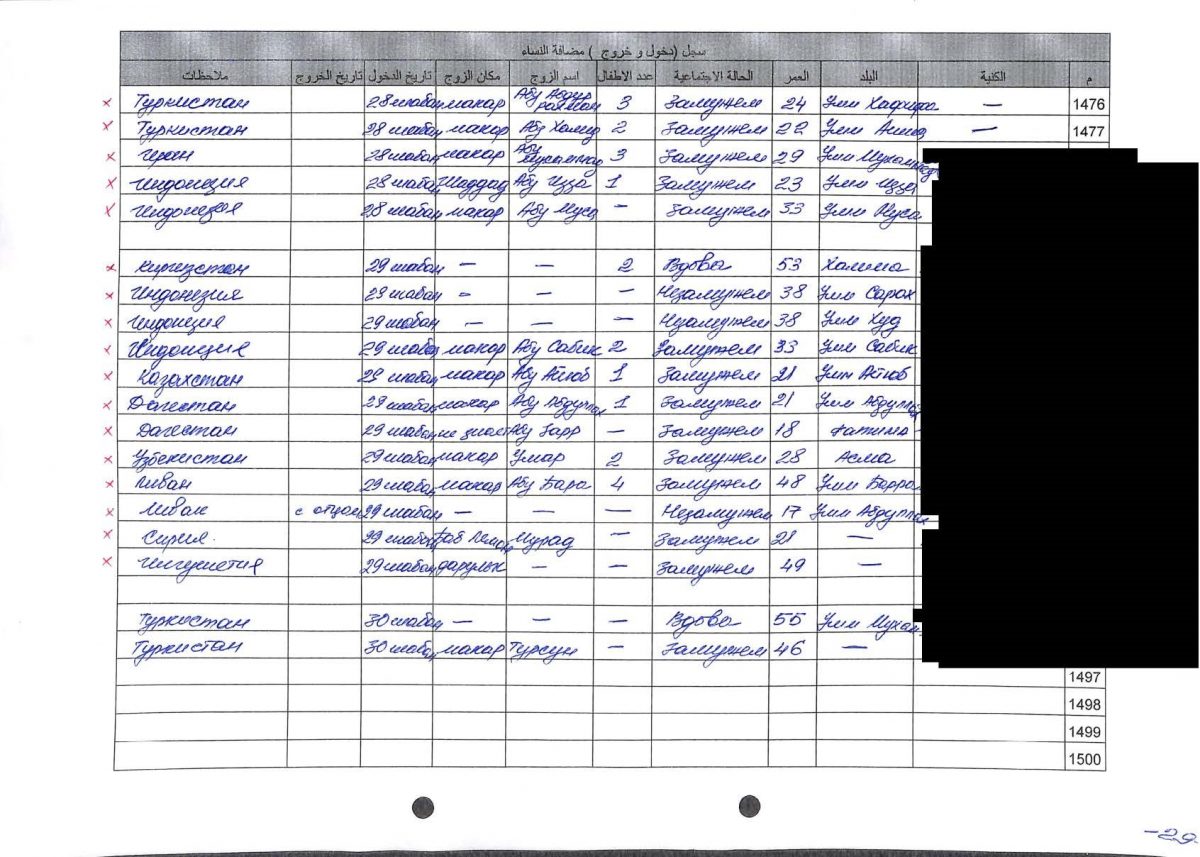

The guesthouse log, as the authors refer to it in this article, is a series of printed pages that keep track of the women who apparently spent some time at the facility at which this registry was kept. They are number in the lower right-hand corner of each page sequentially (1-49), suggesting they go together. Each page contains line-by-line entries with each entry representing a woman who came into this particular guesthouse. An example of this can be seen in Figure 1.

While the columns were mostly consistent across all of the pages, there were some differences. For instance, some pages had only one space for the name of the registrant while other pages separated first and last names into separate columns. In other cases, information was placed in columns where the header did not match the information (for example, the country of origin was placed under a column labeled ‘remarks’). That said, the following information appeared on the pages:d

# (a simple ID number of each entry on a page)

Name

Alias

Age

Marital Status

Number of Children

Name of Husband

Location of Husband

Date of Entry

Date of Exit

Country of origin

There were 1,139 entries with some level of information completed, 1,138 of them with either a name or an alias entered. Among the other columns, information was filled out to varying degrees, with some columns such as age and marital status containing more information than other columns, such as the name of husband and date of exit columns, which were filled out more sparingly. In what follows, the authors examine various cuts of this data to see how it informs existing understanding of a previously under-examined aspect of travel into Islamic State territory—that of women coming from around the world.

Figure 1: Page from Islamic State Female Guesthouse Registry

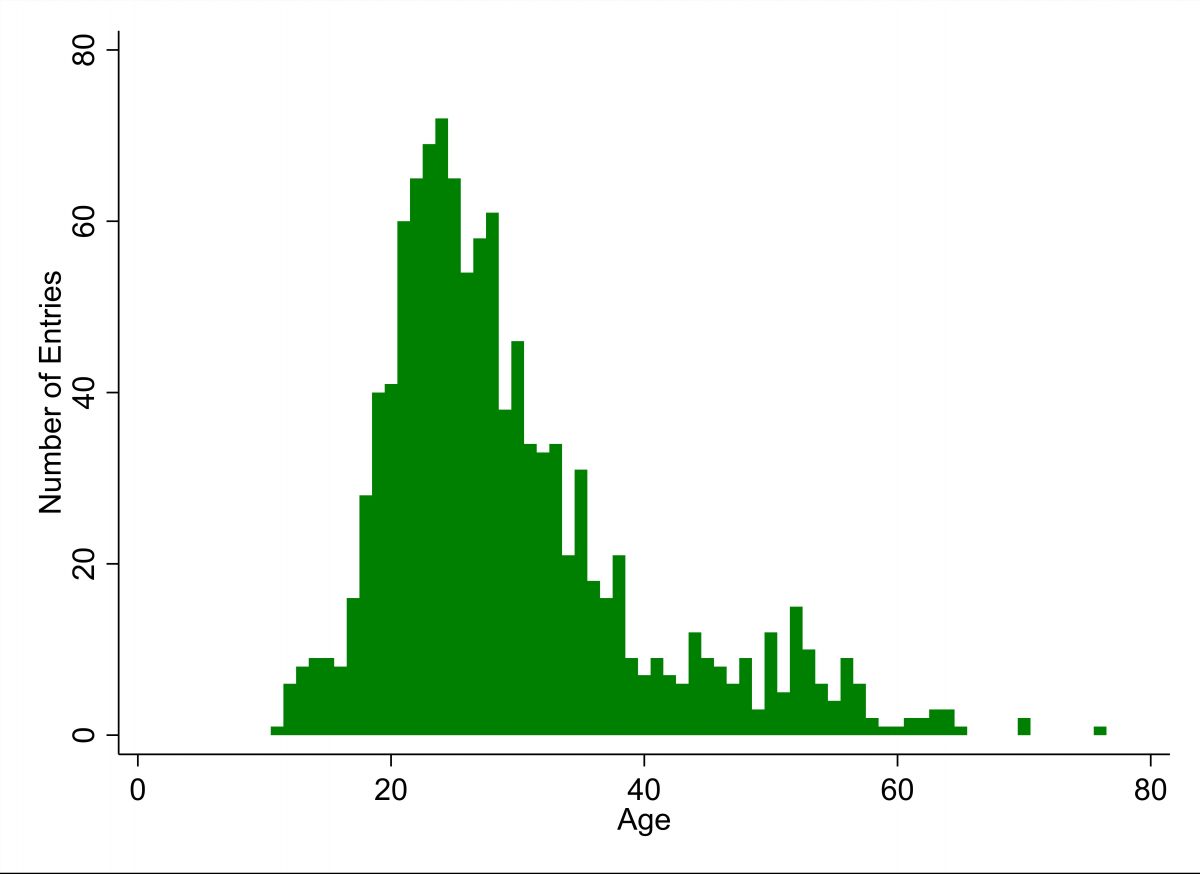

Age

Figure 2 provides the age breakdown for the 1,132 women for whom an age was entered. As can be seen, there is a wide distribution of ages. The youngest entrant in the data was 11 years old, while the oldest was 76. The overall mean in the dataset was approximately 29 years old. The wide range of ages is important. As noted previously, much of dialogue about the travel of females into Islamic State territory revolves around young women, but this data reveals a more diverse flow. Only five percent of the women who stayed in this particular guesthouse were 17 years old or younger. If one groups together those who are 21 years old or under, it only accounts for 20 percent of the women.

Figure 2: Age Distribution of Women Who Stayed in Guesthouse

This finding is particular interesting when compared to what is known about demographics of the male foreign fighter population that entered to fight on behalf of the Islamic State. Using leaked entry forms for that group of fighters, the average age range was found to be 26-27 years old, or about two to three years younger than for those listed in the female guesthouse data.10 Indeed, among entering male foreign fighters, about 10 percent of the overall population was 17 years old or younger, or about double what the female guesthouse data reveals.

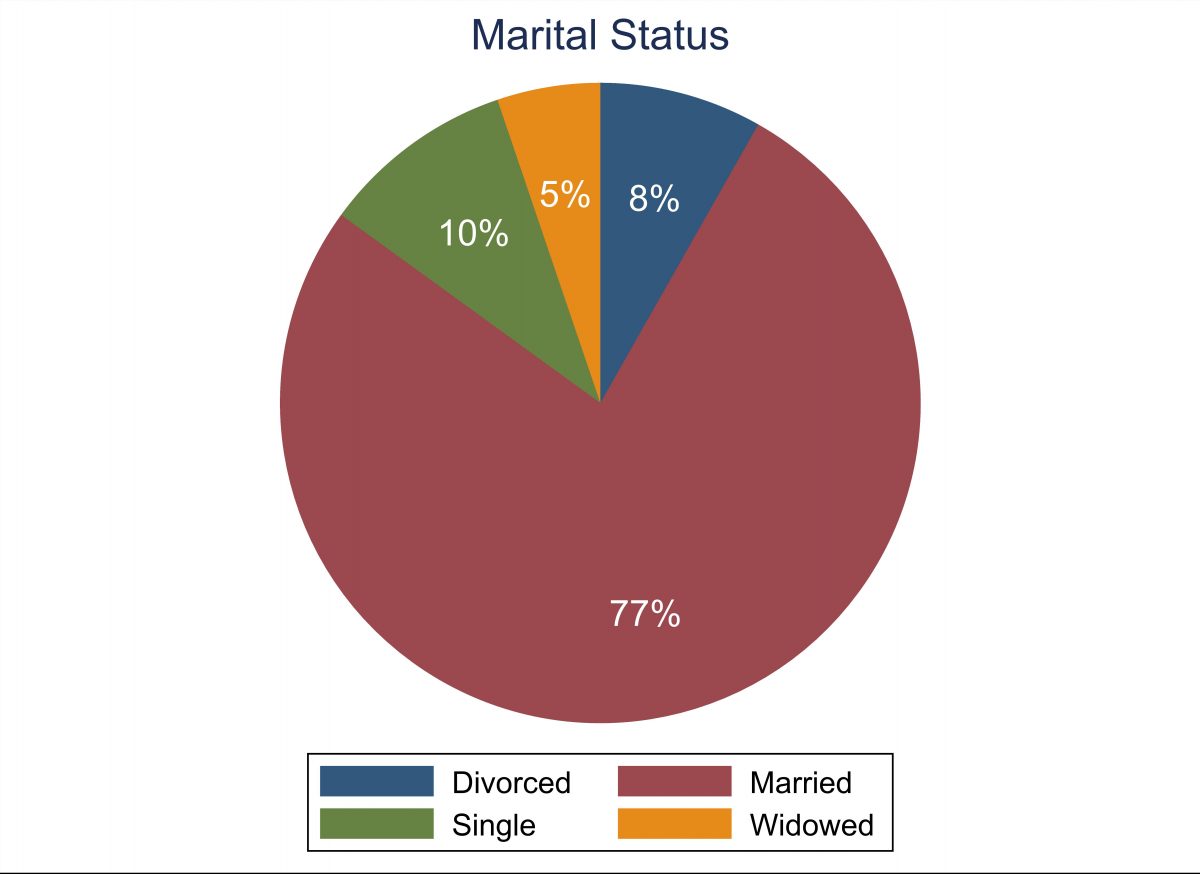

Marital Status

Figure 3, for which 1,135 of the women had an entry next to their name, shows the breakdown of marital status. Although most of the women had common notations of “married” or “single” next to their names, there were departures from the more common responses. Two women noted their status as “ran away from husband,” although the guesthouse book provides no additional details. A smaller number of women listed their status as “divorced.”

Among the more common categories, the possibility exists of a couple of intriguing findings. The first is that, of the more than 1,100 women who transited this guesthouse, 77 percent of them were married. This stands in contrast to what was found among the entering male foreign fighters, of whom only 30 percent were married.11 This asymmetry in marital status raises the possibility of differing motivations for coming to the caliphate. While the fact that a large portion of males were single may indicate that finding a partner might have motivated a non-trivial potion of the men to enter the caliphate and join the Islamic State, the high proportion of married women in the guesthouse would suggest it may not have been as common of a motivation for women.e That is not to say that finding a partner was not a possible motivation for women staying at this guesthouse as 10 percent were listed as single. However, this number pales in comparison to the 61 percent of men who were listed as single among the leaked foreign fighter records.

This point, though intriguing, should not be overemphasized due to two related data caveats. First, it is not known if the women staying at this guesthouse were coming from outside of Syria or whether they were traveling from location to location within the Islamic State’s territory. Second, because it is not known if the women staying at this guesthouse came directly from abroad, there is no way of knowing if they were married prior to arriving in Syria. Unfortunately, the few insights into the Islamic State’s female guesthouse system available in the open source do not allow the authors to clarify this point.f

That said, beyond having potential implications for the motivation of individuals to travel, the marital finding also speaks to a challenging dynamic for women who did make it to the caliphate. Stories have come out of the Islamic State’s territory of women being married multiple times to a number of fighters after a previous spouse died in battle or from other causes.12 This data suggests one possible reason for this practice: there was a shortage of available women to whom Islamic State fighters could be married. Granted, this data does not take into account the availability of locals to whom fighters could be married, but the fact that such a high proportion of women staying at this guesthouse were married makes this a distinct possibility.

Figure 3: Marital Status of Women Lodging at the Guesthouse

One of the other interesting pieces of the marital status data is the relatively high number of divorced and widowed women who appeared in the dataset. Taken together, 13 percent of all the women who stayed at this guesthouse fell into these two categories, which is more than the number who listed themselves as being single.

Children

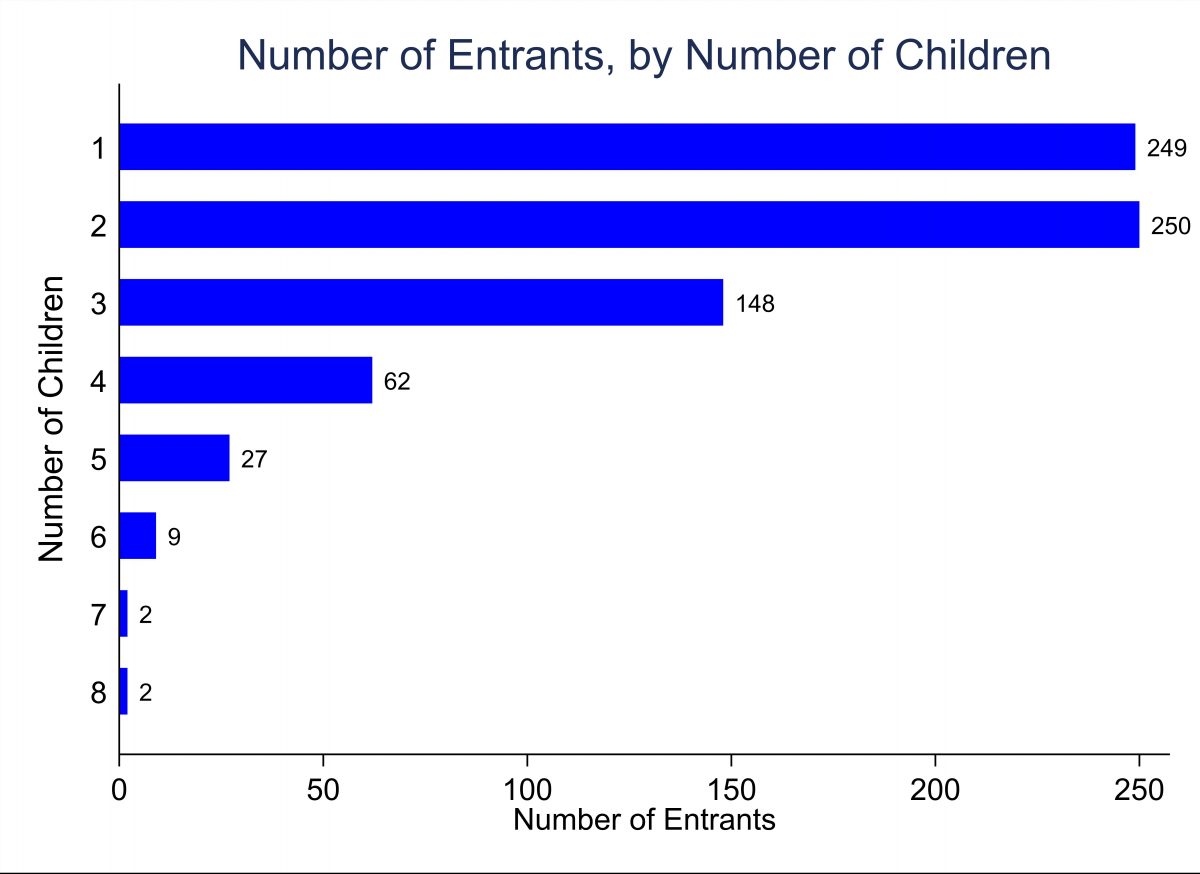

In examining the number of children listed for each of the women in the guesthouse registry, it is important to note that that it is not clear whether any or all of the listed children were traveling with the individual who was staying at the guesthouse or whether these numbers also include any children left in their home countries. Given that caveat, Figure 4 shows the breakdown of the number of children listed for the 749 women for whom this column was completed.

Figure 4: Number of Entrants, by Number of Children Listed

Country of Origin

Overall, the women who stayed in this guesthouse were from 66 different locations around the world.g Table 1 breaks down the individual locations from which the women came, as well as the number of women on the guesthouse register per one million citizens in their location of origin.h

Before discussing the data in detail, two caveats must be made. First, it is worth reemphasizing what this data shows. It may be the case that it shows the number of female entrants into the Islamic State’s territory during this time period, but there is no way to determine that. At the very least, it shows the origins of women who stayed at this guesthouse, for whatever reason, during the time period covered by the log books. Second, the guesthouse register was in Russian. Although it is clear from the diversity in the origins of registrants that the guesthouse was not exclusively for individuals from Russian-speaking countries, one cannot exclude the possibility that individuals from such countries were more likely to stay here than individuals from countries where other languages were spoken more predominately.

With these caveats in mind, the data in Table 1 reveals at least three interesting findings. Perhaps the first is the diversity of locations from which the women staying at the guesthouse came. As mentioned, according to the data for this guesthouse, women from 66 different locations stayed for some period of time in the caliphate. Though this may surprise some, it is consistent with a similar pattern research has shown for male foreign fighters, who have come from an equally diverse array of countries.13 If this small snapshot of data is any guide, the message of the caliphate appears not to discriminate in its wide appeal based on gender.

The second intriguing finding has to do with the ‘top’ locations from which the women came. The most common location of origin for the women staying at this guesthouse is Dagestan, with 200 individuals listed in the registry. What is more, Dagestan is also the location with the most women on the registry when taking that location’s population into account. The number of women staying in the guesthouse per million citizens of Dagestan is 67.89. In fact, four of the top five locations in terms of the per capita ratio are Russian provinces.

Table 1: Country of Origin of Guesthouse Entrants

| Location of Origin | Records (#) | Women per Million

Citizens |

| Dagestan | 200 | 67.89 |

| Turkey | 124 | 1.58 |

| Xinjiang | 76 | 3.48 |

| Tajikistan | 73 | 8.54 |

| Azerbaijan | 61 | 6.32 |

| Russia | 61 | 0.42 |

| Indonesia | 54 | 0.21 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 53 | 8.90 |

| Chechnya | 50 | 39.40 |

| Uzbekistan | 44 | 1.41 |

| Morocco | 39 | 1.12 |

| Kazakhstan | 34 | 1.94 |

| Egypt | 31 | 0.33 |

| France | 23 | 0.35 |

| Tunisia | 22 | 1.95 |

| Germany | 15 | 0.18 |

| Syria | 15 | 0.80 |

| Iran | 14 | 0.18 |

| Sweden | 11 | 1.12 |

| Kabardino-Balkaria | 10 | 11.63 |

| Pakistan | 10 | 0.05 |

| Ingushetia | 7 | 16.99 |

| Australia | 6 | 0.25 |

| Lebanon | 6 | 1.03 |

| Netherlands | 6 | 0.35 |

| Tartarstan | 6 | 1.58 |

| United States | 6 | 0.02 |

| Georgia | 5 | 1.35 |

| Saudi Arabia | 5 | 0.16 |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 0.08 |

| Bosnia & Herzegovina | 4 | 1.13 |

| Iraq | 4 | 0.11 |

| Karacayevo-Cherkessia | 4 | 8.37 |

| Kosovo | 4 | 2.22 |

| Macedonia | 3 | 1.44 |

| South Africa | 3 | 0.05 |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 3 | 2.21 |

| Ukraine | 3 | 0.07 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | 0.01 |

| Belgium | 2 | 0.18 |

| Jordan | 2 | 0.22 |

| Latvia | 22 | 1.01 |

| Libya | 2 | 0.32 |

| Palestine | 2 | 0.42 |

| Sudan | 2 | 0.05 |

| Abkhazia | 1 | 4.15 |

| Afghanistan | 1 | 0.03 |

| Albania | 1 | 0.35 |

| Austria | 1 | 0.12 |

| Belarus | 1 | 0.11 |

| Brazil | 1 | 0.00 |

| Bulgaria | 1 | 0.14 |

| Caucasus | 1 | N/A |

| Crimea | 1 | 0.44 |

| Denmark | 1 | 0.18 |

| Guyana | 1 | 1.30 |

| India | 1 | 0.00 |

| Israel | 1 | 0.12 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 0.03 |

| Maldives | 1 | 2.44 |

| Philippines | 1 | 0.01 |

| Slovenia | 1 | 0.48 |

| Somalia | 1 | 0.07 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 0.12 |

| Turkmenistan | 1 | 0.18 |

| Yemen | 1 | 0.04 |

Other locations that stand out in the analysis are Turkey, with 124 women listed in the log book, and Xinjiang, with 76 women listed. Although the per capita figure for these countries is comparatively small, the absolute number of women is noteworthy. The presence of Turkish women among the Islamic State’s was confirmed by an Iraqi court, which recently sentenced 16 of them to death for supporting the Islamic State.14 However, while Turkey’s geographic proximity to the Islamic State’s territory makes it a likely origin country, the number of women (whether from Turkey or other locations) staying in the guesthouse raises additional questions more broadly about how effective Turkey’s efforts to close the border to travelers were, particularly when it comes to females. The same border policing challenge may exist in the case of women leaving the caliphate, as a recent article noted that many women who lived previously in the caliphate’s territory are now back in Turkey, either under arrest or temporarily staying in Turkey while trying to leave.15

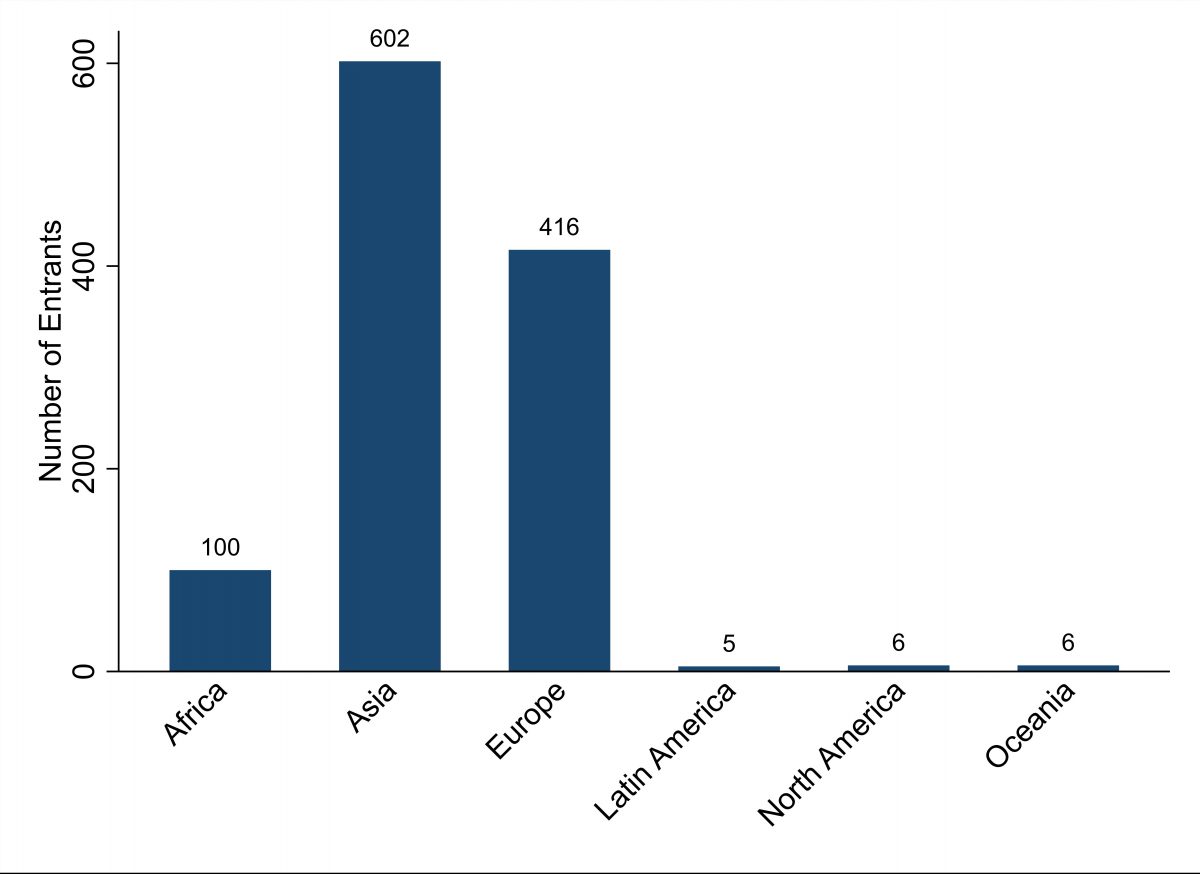

The third and final finding related to the geographic dynamics in this data can be seen by aggregating the data into regions. To group the data, the authors relied on the United Nations’ classification scheme for regions of the world, coding each individual that stayed at the guesthouse into a region based on her country of origin.16 Figure 5 shows stark differences between regions.

The large number of fighters from the European region is due to the fact that the United Nations considers Russia as part of the region, and Russia and its territories accounted for 340 of the women in Europe. This is certainly consistent with recent reports, one of which cited an estimate of over 700 Chechen women and children as having traveled to Iraq and Syria.17 Although much smaller in scale, another recent report suggested that Iraq deported to Russia four women and 27 children who the Iraqi government suspected of having ties to the Islamic State.18 It certainly seems plausible that Russian women formed an important part of the female contingent traveling to the Islamic State’s territory.

One of the other key populations of interest is Central Asia, which represents 34 percent of the total number in the Asia region. Recent events such as the use of a truck by an Uzbekistan-born militant to kill eight individuals in New York City and the growing number of Islamic State recruits from Central Asia have attracted more attention to the region.19 However, there has long been a connection between Central Asia and jihad.20 Regardless of when it became a problem, it seems clear from this data that the Central Asia problem is not constrained by gender. The contingent of women in the log books from Central Asia is comparatively larger than almost all other sub-regional groups.

Figure 5: Guesthouse Entries, by Region

The last group worth mentioning is not because of large numbers, but comparative small numbers: those from Western countries. Of the entire dataset of over 1,100 individuals, only seven percent come from Western countries.i This is a bit surprising, particularly given the prominent public focus in Western media placed on the travel of Western women to join the Islamic State. At the very least, this seems to suggest that the challenge of female travelers to the Islamic State is much more of a world challenge than it is an exclusively Western challenge.

Of course, there is a possibility that the data is skewed because this guesthouse was more prone to receive travelers from a certain region. It is important to reiterate at this point that the guesthouse registry was in Russian, which likely explains the large number of women from Russia who transited this particular guesthouse. However, anecdotal evidence actually provide some support for the possibility that the data presented above may be an accurate representation of the female population of the Islamic State. In September 2017, Iraq said it was prepared to deport over 1,300 women and children, “most of [whom] came from Turkey, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Russia.”21 Naturally, this may not be because more women came from these countries, but it could be due to the fact that Western countries have not made the decision on whether to even accept individuals returning from Islamic State-held territory.

Conclusion

This piece began by highlighting what seems to be a common narrative regarding the women who end up in the territory of the Islamic State: they are young, Western women who have been duped into traveling to the caliphate. The data here, limited though it is, paints a far more diverse picture of the types of women who were documented by the group to be transiting in and out of Syria. It seems a stretch to argue that all of these women decided to travel without any knowledge or awareness of what they were doing or the conditions into which they were heading.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from this data is that the challenge of dealing with the outflow of individuals from Iraq and Syria who were living in territory controlled by the Islamic State extends far beyond the men and boys who came to fight for the group. Indeed, the log book presented here records more than 1,100 women as having set foot in this single one guesthouse over an approximately four-month period. That said, it needs to be clearly stated that the point of this article is not that all women who transited into the caliphate were members of the Islamic State. Rather, this analysis has shown that these women are a diverse group in terms of age, country of origin, and family status. The motivations for their travel are likely to be similarly diverse.

The magnitude of entries as well as their diversity should give pause to policymakers regarding the potential for long-term issues arising from the diminution of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Women and children, even if not complicit in or contributing to what the organization was doing, will require repatriation and resettlement assistance. Those who were willing participants in the organization will be of special concern to security services. This concern was highlighted anecdotally by a recent article that talked with women who fled Iraq and Syria, but remained committed to the ideals of the Islamic State and the need for future violence.22 However, the pursuit of any threats that might potentially arise in the future must be balanced against the important of due process, fair treatment, and the protection of human rights.

There is another important point this article illustrates that is less obvious. The authors acquired the captured enemy material that populated this article from the Department of Defense, which in turn acquired it from the battlefields of Syria. As this article has shown in a small way, and as has been demonstrated more broadly with the publication of a New York Times piece featuring materials picked up in the aftermath of conflict, there is much to be learned from what has been left behind on the battlefield.23 Continued efforts to release and study this material are likely to yield far more important and substantive contributions to the collective understanding of how organizations like the Islamic State fight, evolve, and threaten the world. CTC

Daniel Milton, Ph.D., is Director of Research at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. He has authored peer-review articles and monographs related to terrorism and counterterrorism using both quantitative and qualitative methods. His published work has appeared a number of venues, including The Journal of Politics, International Interactions, Conflict Management and Peace Science, and Terrorism and Political Violence.

Brian Dodwell is Deputy Director of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. His research interests include jihadi terrorism in the United States, U.S. homeland security challenges, and the nexus between terrorist groups and transnational criminal organizations. Mr. Dodwell regularly lectures to intelligence and law enforcement community audiences on these and other related topics.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Colleen McCue and Major Meghan Cumpston for their support and advice on this project. It would not have been possible with their assistance.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

Substantive Notes

[a] Unfortunately, the year of the guesthouse registry is hard to discern from the books themselves. The best guess the authors can hazard is sometime from 2014-2016.

[b] This despite explicit recognition in early research that “the assumption that females join ISIS primarily to become ‘jihadi brides’ is reductionist and above all, incorrect.” Erin Marie Saltman and Melanie Smith, ‘Till Martyrdom Do Us Part’: Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon (London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2015), p. 5.

[c] As is the case with all CTC products involving captured enemy material, once the data was provided by the Department of Defense to the CTC, the analysis was conducted by the CTC alone.

[d] In the pages, it is clear that the individual filling out the sheets did so with only moderate attention to the column headings. For instance, country of origin was listed under the ‘remarks’ column, and the alias of the woman was often listed in the column marked ‘country.’

[e] The interrogation of Umm Sayyaf, wife of a higher-ranking Islamic State official, is said to have revealed the promise of at least one wife as part of the Islamic State’s recruitment pitch to males. Nancy A. Youssef and Shane Harris, “The Women Who Secretly Keep ISIS Running,” Daily Beast, July 5, 2015. Another scholar pointed out that offering wives to incoming male fighters was “the perfect solution to the so-called ‘marriage crisis,’” in which many males in Arab countries remain unmarried because of the high cost. Mia Bloom, “How ISIS is Using Marriage as a Trap,” HuffPost, March 2, 2015.

[f] References to guesthouses appear in several accounts based on interviews with women who lived within the Islamic State’s territory. Carolyn Hoyle, Alexandra Bradford, and Ross Frenett, Becoming Mulan? Female Western Migrants to ISIS (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2015); Kim Willsher, “’I went to join ISIS in Syria taking my four-year-old. It was a journey into hell,’” Guardian, January 9, 2016; Ben Wedeman and Waffa Munayyer, “Bride of ISIS: From ‘happily ever after’ to hell,” CNN, April 26, 2017; Rodi Said, “Islamic State turned on dissenters as Raqqa assault neared,” Reuters, June 28, 2017.

[g] Several of the ‘countries’ listed in the guestbook are non-internationally recognized countries, but instead sub-regions of larger countries. For this presentation of the data, the authors elected to keep these regions separate instead of aggregating them into the larger countries to which they pertain, as the authors felt that this provides a more informative look at the data.

[h] The calculation of women per million citizens was made based on the total population in the country of origin in 2015, based on population figures from the World Bank. In the case of provinces and locations within Russia and China, census data was used where possible. Most of the population estimates for Russian territories came from the 2010 population census, which was the last available population census.

[i] The following countries had at least one entrant and were categorized as Western countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States.

Citations

[1] “American Girls May Have Wanted to Join ISIS in Syria, FBI Says,” CBS News, October 21, 2014; Katrin Bennhold, “Jihad and Girl Power: How ISIS Lured 3 London Girls,” New York Times, August 17, 2015.

[2] Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, “This is the Promise of Allah,” June 29, 2014.

[3] Abu Bakr al-Husayni al-Qurashi al-Baghdadi, “A Message to the Mujahidin and the Muslim Ummah in the Month of Ramadan,” July 1, 2014.

[4] Anita Peresin, “Fatal Attraction: Western Muslimas and ISIS,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9:3 (2015).

[5] Erin Marie Saltman and Melanie Smith, ‘Till Martyrdom Do Us Part’: Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon (London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2015); Anne Speckhard and Ardian Shajkovci, “Beware the Women of ISIS: There Are Many, and They May Be More Dangerous Than the Men,” Daily Beast, August 21, 2017.

[8] Peter R. Neumann, “Foreign fighter total in Syria/Iraq now exceeds 20,000; surpasses Afghanistan conflict in the 1980s,” ICSR, January 26, 2015; Bibi van Ginkel and Eva Entenmann eds., The Foreign Fighters Phenomenon in the European Union (The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2016), p. 4.

[11] Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler.

[13] Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler.

[16] The U.N. method for assigning countries to geographic regions can be found at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/

[19] Syria Calling: Radicalisation in Central Asia (Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2015); Andrew E. Kramer, “New York Attack Turns Focus to Central Asian Militancy,” New York Times, November 1, 2017.

[20] Ahmed Rashid, Jihad: The Rise of Militant Islam in Central Asia (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002).

[23] Rukmini Callimachi, “The ISIS Files: When Terrorists Run City Hall,” New York Times, April 4, 2018.

Skip to content

Skip to content