Abstract: A detailed case study of a Portuguese Islamic State network with strong connections to the United Kingdom sheds significant light on the foreign fighter recruitment pipeline between Europe and Syria. Several of the men involved in the network made two trips to Syria. On January 9, 2013, British authorities informed their Portuguese counterparts that at least two Portuguese citizens were involved in the (first) kidnapping of British journalist John Cantlie in Syria. That information opened a seven-year investigation, recently closed, in which the Portuguese Judiciary Police were able to follow in real time the preparations, contacts, and final travel to Syria of a group of Islamist extremists, including their wives and children, who would join what became the Islamic State. Investigators established how they financed themselves through the creation of fictitious applications for student loans and welfare benefits in the United Kingdom. They used that money to travel but also to recruit and help young British extremists make their way into Syria, using Lisbon as transit point. But investigators were not able to shut down the pipeline because foreign fighter travel would only become a crime under Portuguese law in 2015, underlining the importance of such legislation. Several members of the network are presumed dead, while others face trial in Portugal. The most senior alleged member of the network, Nero Saraiva, was transferred from Syria to Iraq where he could face trial or extradition to Portugal. Saraiva allegedly became close to the Islamic State group known as the “Beatles” and appears to have had advanced knowledge of the execution of the American journalist James Foley.

“Message to America. The Islamic State is making a new movie. Thank u for the actors.” Posted on Twitter and Facebook on July 10, 2014, by Nero Saraiva, a self-professed Portuguese Islamic State fighter already on the radar of Western security services, the cryptic message received little attention.1 But 40 days later, it gained an entire new meaning. On August 19, 2014, the Islamic State published a four-minute, 40-second English video on the internet.2 Its title: “Message to America.” Its content: the shocking murder of American journalist James Foley.

British and Portuguese intelligence officials eventually came to the conclusion that Saraiva’s post on social media was no accident, but that he had advanced knowledge of James Foley’s fate and might have been involved in the production of Islamic State videos.3

Saraiva had arrived in Syria in April 20124 as one of the first European foreign fighters to join the conflict. He allegedly became part of a group responsible for a wave of kidnappings of Western citizens5 and became close to the British jihadis known as the “Beatles”a led by Mohammed Emwazi, the Islamic State executioner known as ‘Jihadi John.’6 While in Syria, Saraiva maintained several social media accounts where he shared images of his daily life in the jihadi battleground: pictures of weapons, armored cars, and Islamic State flags were mixed in with mundane images of landscapes, cats, horses, and food.7

In Syria, according to the author’s investigative reporting and court documents, Saraiva was the most senior member of a jihadi network of Portuguese nationals who joined the Islamic State.8 The group had bonded in London, to where they start moving in the early 2000s, and had become radicalized under the influence of hate preacher Anjem Choudary9 and the online preaching of Yemeni-American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki.10 The network included several sets of brothersb and childhood friends, all with roots in former Portuguese colonies in Africa. According to court documents, in the United Kingdom they had lived on welfare state benefits and had been able to create a scam that allowed them to obtain thousands of pounds in state subsidies, which they used to travel to Syria, recruit several British jihadis, and support Nero Saraiva’s activities in Syria.11

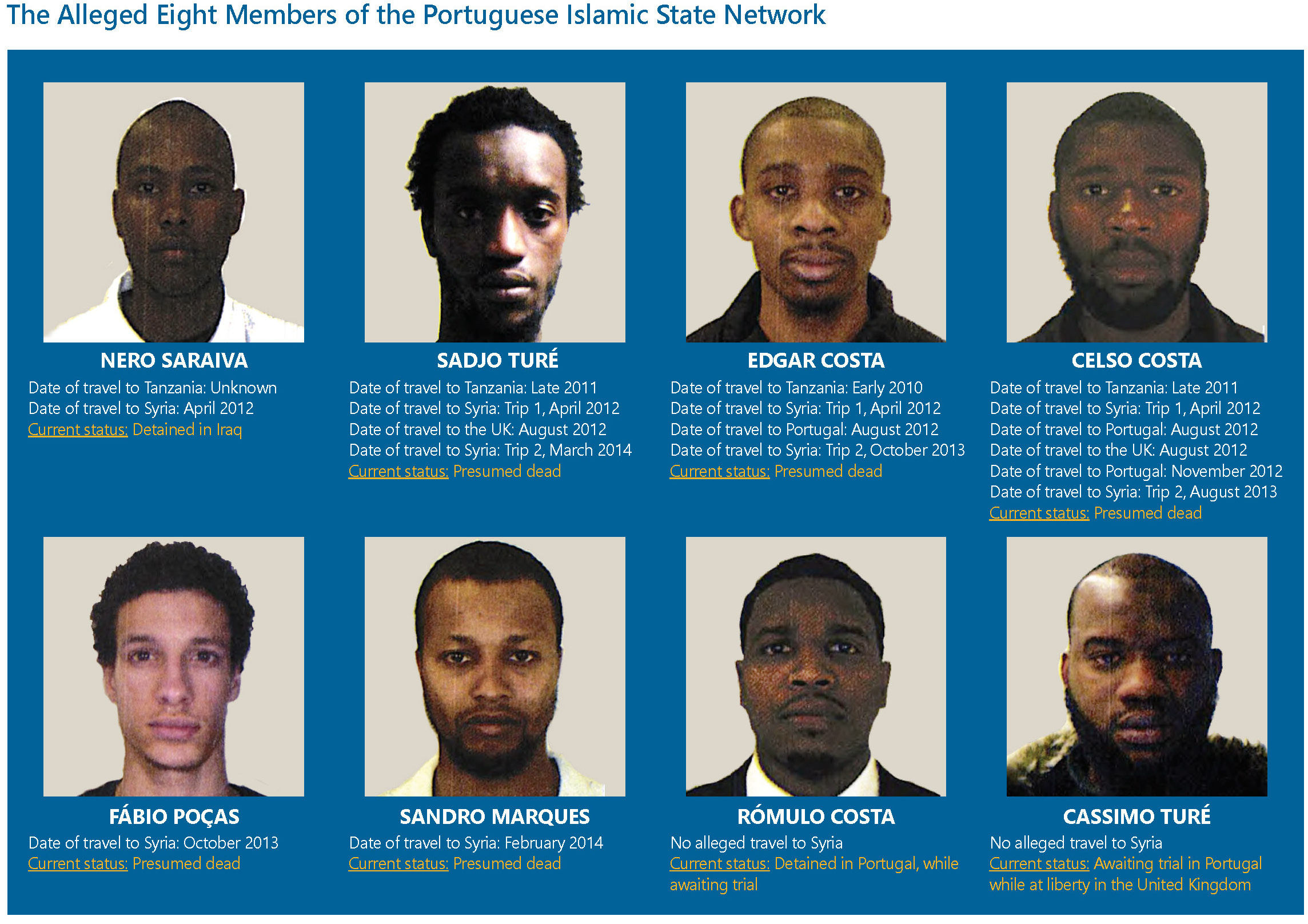

Aside from Nero Saraiva, the other key figures in the Portuguese jihadi network were Sadjo Turé, a recruiter and treasurer;12 Edgar Costa, an ideologue and trainer;13 and his brother Celso Costa, who appeared in several Islamic State propaganda videos.14 Edgar Costa, Celso Costa, and Sadjo Turé first traveled to Syria in April 2012 with Nero Saraiva.15 But while Saraiva stayed in northern Syria, the two Costa brothers and Sadjo Turé returned to Europe in August that year.16 The network would then expand to include Portuguese nationals Fabio Poças and Sandro Marques, who were also living in London at the time and were unknown to the authorities.17 Between 2013 and 2014, the five of them traveled to Syria with their respective wives and children and were reunited with Saraiva.18 Two other alleged members of the network, Cassimo Turé and Rómulo Costa, remained behind, in Portugal and the United Kingdom, respectively.

All eight (see Figure 1) were charged with terrorism-related offenses by prosecutors in Lisbon and are expected to be put on trial in September 2020, with all but two likely to be tried in absentia.19 Rómulo Costa is currently detained in Portugal; Cassimo Turé is awaiting trial while at liberty in the United Kingdom.20 Sadjo Turé, Edgar Costa, Celso Costa, Sandro Marques, and Fábio Poças have died while fighting for the Islamic State, intelligence and police authorities believe.21 But without conclusive evidence of their deaths, prosecutors decided to charge them in absentia.22

Saraiva was also charged in absentia. Despite being the first to arrive in Syria, Saraiva was apparently the only one of the adult male travelers to survive the fall of the Islamic State. In March 2019, he was arrested by the Syrian Democratic Forces after he left Baghouz severely injured.23 Then, in early 2020, he was transferred to coalition forces’ custody in Iraq24 and is considered a key element to clarifying what happened to Western hostages like British photojournalist John Cantlie and American reporter James Foley.25 He could face the death penalty in Iraq or be extradited to Portugal to stand trial for his crimes.26

This article provides detailed insight into how one group of European foreign fighters operated prior to their travel to Syria and their contacts, plans, relationships, and lives in the Islamic State. It starts by explaining how a group of childhood friends from the outskirts of Lisbon became radicalized in the United Kingdom and how they proceeded with their intentions to join a jihadi group by traveling first to Tanzania and then to Syria in early 2012. It will detail how one of them remained in Syria while the others returned to Europe where they became the target of a police investigation in Portugal and the United Kingdom and how the then absence of legislation in Portugal criminalizing foreign fighter travel allowed several to return to Syria to join what would become the Islamic State. This article will also describe how investigators were able to track their steps and status in Syria through online monitoring, shedding light on the environment in which such foreign fighters operated. The article concludes by examining the foreign fighter recruitment pipeline between Europe and Syria and the challenges counterterrorism officials had in shutting it down.

The information presented here is the result of six years of investigative reporting by the author in Portugal, the United Kingdom, and Finland,27 and is based on more than 10,000 pages of judicial documents, as well as interviews the author conducted with counterterrorism and intelligence officials, witnesses, one alleged member of the network (Poças) while he was with the Islamic State, and several relatives of the eight-man group.

The UK Radicalization of a Portuguese Friendship Group

Sadjoc and Cassimod Turé, Sandro Marques,e and the brothers Rómulo,f Edgar,g and Celso Costah were childhood friends. They lived in the county of Sintra in the outskirts of Lisbon, went to the same school, and shared a love for soccer and music. In the late 1990s, Sadjo Turé and the three Costa brothers were part of a hip-hop group called Greguz du Shabba28 and spent afternoons in their family apartment, improvising rhymes about racism, poverty, and social exclusion, while practicing break dance moves.29

The Costa brothers, who were Portuguese nationals of Angolan descent, and Sandro Marques, a Portuguese national of Cape Verdean descent,30 were raised in Catholic families.31 Sadjo and Cassimo Turé, Portuguese nationals whose family originated from Guinea-Bissau, were the only ones in the alleged eight-man network raised in a Muslim family.32 One by one, the Sintra group started immigrating to the United Kingdom to study and work. The first to move was Sadjo Turé, around 2003.33 He went to live in an apartment on Creighton Road in north London, in a building mostly occupied by immigrants, and would later move to a tower block in the east London district of Leyton.34 In 2005, he was joined by his older brother, Cassimo Turé.35

Sandro Marques and Rómulo and Celso Costa followed them not long after.36 Edgar Costa stayed in Portugal until after he finished his marketing degree in Porto, and by 2007, he had also moved to London, along with his girlfriend.37

It was in the British capital that some years later the Sintra group met Nero Saraivai and Fábio Poças.j Both, like the Costa brothers, had Angolan origins.38 Born in Angola, Saraiva at age three moved to Portugal with his mother to escape civil war.39 He went to a Catholic school until his mother moved to the United Kingdom40 where his name appears on the electoral roll from 2003.41 Poças was the youngest of the group. Born in Angola, he was raised in the outskirts of Lisbon. At 16, he went to live with an aunt in London42 to study arts and play soccer.43 He enrolled in a Muay Thai gym where he met the rest of the group.44

The Portuguese London friendship group would gather to play soccer in public parks and watch Portuguese soccer games in a Portuguese café.45 The circumstances are not clear, but at some point, the non-Muslim members of the group converted to Islam. Very little is known about how the group as a whole became radicalized.

Sadjo Turé, who had resided in London the longest, at a certain point came to admire the hate preacher Anjem Choudary,46 and the rest of the Portuguese group came to share these views.47 In a later search of the Costa family residence in Lisbon, the police found CDs and DVDs with preachings and writings by the Yemeni-American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki and, among others, a PDF copy of Join the Caravan, the book authored by Abdallah Azzam, the Palestinian cleric who led the mobilization of Arab fighters to Afghanistan in the 1980s.48

The Portuguese group stopped drinking alcohol, going out at night, and playing music.49 Gradually, they drifted away from the remaining Portuguese community in Leyton. “They spent a lot of time talking about religion and reading the Quran. They stopped playing soccer with us and started playing with each other. They started to learn Arabic and from time to time they came to us talking about religion,” a person who had once been friends with them told the author.50 What is certain is that by around 2010, most of them were already radicalized51 and had two goals in mind: to join a jihadi movement52 and to marry and have children.53

Travel to East Africa and Syria

According to court documents, in early 2010, Edgar Costa traveled to Tanzania and stayed for two years.54 While living in Dar es Salaam, he met through Facebook55 and marriedk then 18-year-old Fatuma Majengol who was later described by Saraiva in recorded conversations as “the best wife” because she was “quiet” and “obedient.”56 In Tanzania, Portuguese authorities believe, Edgar Costa enrolled in terrorist training camps connected to al-Shabaab and became an instructor.57 According to recorded conversations, one of those he trained was his friend from London Nero Saraiva, the first of the Portuguese group to join him in East Africa.58

In the summer of 2010, at an East London mosque, Celso Costa was introduced to Reema Iqbal,m then 21 years old, who had come to take Islam more seriously after a failed relationship left her with a broken heart.59 They married weeks later at the Iqbal family home, with the women separated from men.60 Celso Costa then suggested that his wife’s best friend, Shima Essanoor, ought to marry his best friend, Sadjo Turé.61 Shima agreed, and soon the four were living together in a council flat in the London neighborhood of Walthamstow that belonged to Nero Saraiva,62 who had left to join Edgar Costa in Tanzania.

The Costa-Turé household appears to have been an echo chamber of extremism: non-Muslims were described as “pigs” and “kuffar” and Shima later told The Sunday Times that they would switch off mobile phones and put them in another room to avoid monitoring.63

When Shima became pregnant with twins, she told the newspaper the group started to talk about going abroad for jihad, and there was hope she would give birth to sons so that her twins would become “future warriors.”64 “That’s when I knew they had lost it,” Shima said.65 On December 26, 2010, she woke up early and ran away and later reported everything she knew to United Kingdom. counterterrorism police.66 Shima only saw Sadjo Turé once after fleeing, when the twins were two days old.67

Soon after Shima left him, Sadjo Turé married Zara Iqbal,n Reema’s middle sister. The elder Iqbal sister Shamila Iqbalo was married to a newly appointed NHS doctor named Shajul Islam.p Shajul, Celso Costa, and Sadjo Turé became close, with the Portuguese referring to their British friend in recorded conversations as “the doc.”68

Some of the Walthamstow circle would soon follow in the footsteps of their friends Edgar Costa and Nero Saraiva. According to court documents, during 2011, Sadjo Turé, Celso Costa, and their respective wives moved to Tanzania where Portuguese authorities believe they enrolled in terrorist training camps connected to al-Shabaab.69 Their presence in the country is well documented. In a later search of the Costa family residence in Lisbon, the police found receipts of medical assistance for Reema Iqbal, issued by the Regency Medical Center in Dar es Salaam on November 23, 2011; December 16, 2011; and March 15, 2012.70 On February 9, 2012, Zara Iqbal gave birth to her first child with Sadjo Turé in Dar es Salaam.71

Soon after, the group began to relocate to Syria. In early April 2012, Nero Saraiva and Edgar Costa departed to Turkey, through Sudan.72 They took a flight to Istanbul and then a bus to Hatay, and finally to Reyhanli where they settled for two weeks before entering Syria with an Ahrar al-Shamq member.73 They crossed the border on April 14, 2012.74 Six days later, on April 20, Celso Costa and Sadjo Turé arrived in Turkey.75 They followed the same path and joined Nero Saraiva and Edgar Costa in Syria.76 The wives (of Edgar, Celso, and Sadjo) allegedly stayed on the Turkish side of the border: in Lisbon, authorities later found receipts of lab analysis in the name of Reema Iqbal, issued by the Reyhanli Hospital on May 21, 2012, and June 20, 2012.77

According to Saraiva’s Islamic State file,78 his recruiter was “Abu Muhammad al-Absi.” This was the kunya (jihadi fighting name) of Firas al-Absi,79 a Saudi-born onetime dentist who fought in Afghanistan and met Abu Musab al-Zarqawi there.80 Years later, in Syria, al-Absi formed a group closely aligned with Jabhat al-Nusra, the Majlis Shura Dawlat al Islam, which became notorious for kidnapping Westerners and raising an al-Qa`ida flag over the Bab al-Hawa border crossing between Turkey and Syria on July 19, 2012.81

On that same day, British photographer John Cantlie, Dutch journalist Jeroen Oerlemans, and their local guide were taken hostage near Bab al-Hawa82 by al-Absi’s group.83 While attempting to escape, the two men were shot and wounded, but their guide made a break and managed to raise the alarm. They were freed by a group of fighters Oerlemans assumed were part of the Free Syrian Army on July 26, 2012, and returned to Europe.84

In the United Kingdom, John Cantlie recalled his ordeal in several media interviews and described his kidnappers as a group of jihadis from around the world, with as many as 15 appearing to be from the United Kingdom.85 He also mentioned being treated by a doctor who “spoke with a south London accent and was using saline drips with NHS logos on them.”86

Less than three months later, on October 9, 2012, Scotland Yard detectives made the first arrests in “Operation Architrave,” the codename for the British investigation into the abduction of John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemans87 when a newly qualified NHS doctor and his wife landed in Heathrow on a flight from Cairo.88 They were Shajul Islam and Shamila Iqbal.r One month later, another suspect, Jubayer Chowdhury,s was also detained at Heathrow airport after arriving from Bahrain.89 The third and last wave of arrests related to John Cantlie’s kidnapping came on January 9, 2013; three men, including Shajul’s older brother Najul Islam,t were detained at separate addresses in east London.90 A fourth suspect, Sadjo Turé, was arrested that same day at Gatwick airport, as he was about to take a flight to Lisbon.91

The Portuguese Investigation

That same afternoon, January 9, 2013, chief inspector of the Judiciary Police Counter Terrorism National Unit João Paulo Ventura signed a two-page report that initiated one of the biggest terrorism investigations in Portugal.92 According to the document, British authorities informed their Portuguese counterparts that they believed two Portuguese nationals had been involved in the abduction of journalists John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemansu in Syria in July 2012.93 One was Sadjo Turé,94 and the other was Celso Costa, who was then living in Portugal.95 Sadjo and Celso were described as Muslims who lived together in London where they became radicalized.96 An additional individual was mentioned as a person of interest: Edgar Costa, Celso’s brother.97

During the afternoon and evening of January 9, 2013, Portuguese investigators acted swiftly: they collected the suspects’ ID files, addresses, and phone numbers in Portugal and requested permission to initiate wiretaps and video surveillance.98 At 7:45 PM, the requests received the agreement of the Public Prosecutor Vitor Magalhães99 v and were approved by a judge that same evening.100

As they started monitoring the suspects, the Judiciary Police tried to fill in the blanks and understand where the man had been in the preceding months. They quickly found that on August 2, 2012, a few days after the release of Cantlie and Oerlemans, Celso and Edgar Costa had taken a flight from Istanbul to Lisbon.101 They discovered that Sadjo Turé had stayed in Turkey a little longer to register his newborn son at the Portuguese embassy in Ankara. After doing so on August 9, 2012,102 he went back to the United Kingdom that same day.103 Nero Saraiva remained in Syria and for that reason was then not on the counterterrorism radar of Portuguese authorities.104

The news of Sadjo Turé’s detention at Gatwick on January 9, 2013, spread quickly among the Portuguese group after his brother, Cassimo, who was with him when he was stopped at the airport, proceeded with his travel to Lisbon and spread the word.105 In the Portuguese capital, Celso and Edgar Costa expressed concern they might be under investigation, according, ironically, to conversations between them recorded by the Portuguese police106 on January 16, 2013, after Celso’s wife Reema called from the United Kingdom to say that Sadjo Turé had been released without charges.107 The phone interceptions were hard for investigators to interpret. With African origins, the suspects sometimes spoke in Creole.108 Additionally, they adopted security measures, being careful to speak in code over the phone. They referred to Syria as “Susana,” Turkey as “Tomas,” Sudan as “Sudas,” money as “ball,” police as “bonga,” and the jihadi group they had allegedly been with as “the company.”109

Their connection to “the company” was clear during a recorded conversation between Sadjo Turé and Edgar Costa on January 26, 2013. While talking about a possible return to Syria, Sadjo Turé mentioned that there was “going to be a thing on February 10, 11, 12 or 13” but that it did not have anything to do “with kidnaps.” It was the “company’s international day” in which a lot of people were participating, he said.110

Also clear from their conversations was their desire to each marry a second woman and have many children.111 They discussed their favorite nationalities of women (mentioning Bosnia, Morocco, Mexico, Brazil, Germany, and the Netherlands) and whether it was better to marry a recently converted Muslim or one that was raised in the faith. They stressed how important it was that candidates for marriage would be willing to travel abroad for jihad.112 In their search for additional wives, they created profiles on muslima.com and connected with potential brides through Facebook.113

Edgar Costa was the most active in searching for a new wife. In September 2013, after striking out several times, including flying all the way to Mexico City to meet a would-be bride,114 he connected through social media with a woman from the United States. They spoke over the phone, exchanged text messages, and he even sent her $560 to finance her travel to Lisbon, a trip she never took.115

The funds available to the Lisbon group was a concern to police. The Costa brothers had no job and spent most of their days at home, online, playing soccer, and working out in local gyms.116 But they did not lack money.117 The authorities even intercepted a picture Celso Costa sent his wife that featured packs of banknotes of €10, €20, and €50 spread over his bed.118

Edgar Costa, Celso Costa, and Cassimo Turé often went to money transfer shops to collect funds sent from the United Kingdom by Sadjo Turé.119 As they investigated this, Portuguese police learned Sadjo had been detained again in the United Kingdom on February 10, 2013, on suspicions of fraud and fraudulent use of credit cards.120 His house was searched, his ID and passport were taken from him along with £280. He was released a few days later, but he had to present himself at the police station every Tuesday and Thursday and was not allowed to leave the United Kingdom.121 In an intercepted phone conversation with Celso Costa, Sajdo Turé seemed confident, saying that the police took his computer and mobile phone but that “it had nothing.” Cryptically, Turé said that if he were to go to prison one day, it would be “for this and not for that big thing.”122

The reason for Sadjo Turé’s detention became clear to Portuguese investigators in late March 2013. According to court documents, the Metropolitan Police informed their Portuguese counterparts that they had collected evidence that Sadjo Turé acted as a mediator and facilitator in the process of fraudulently obtaining subsidies and loans available in the United Kingdom to foreign students.123 To obtain the funds, he allegedly used real or fake IDs and forged Portuguese qualification certificates. British police also believe he was involved in fraudulent operations in order to get other social benefits.124 The scheme had allegedly been going on for years. According to Shima Essanoor, Sadjo Turé former wife, while in the United Kingdom in 2010, the wider group had all “claimed jobseeker’s allowance,” a benefit once described by Anjem Choudary as “jihad-seeker” allowance, and had “loads of council houses in different people’s names,” as well as student loans and a scheme in which Sadjo Turé generated cash by taking out mobile phone contracts in other people’s names and selling the phones for up to £800.125 To maintain all these alleged schemes, the group had a “book” with a list of names they used to obtain social benefits as well as the email accounts created to be sent the necessary codes to receive the funds.126

These alleged schemes continued after Portuguese police opened their investigation. Once Sadjo Turé received the codes, he would get the money and send some of it to his friends in Portugal through Western Union and Unicambio. According to Portuguese court documents, after Turé realized he was on the British police radar because of his detention at Gatwick airport on January 9, 2013, he was helped in making these remittances by Fabio Poças, a new addition to the Portuguese extremist network.127

Between January and July 2013, the money transfers to Lisbon surpassed 27,000 euros.128 The funds were used to pay daily expenses and travels but was also sent from Lisbon to other countries including Turkey, Mexico, Gambia, and Tanzania.129 According to court documents, during the period in question, more than €6,000 was sent from Portugal to Turkey to someone who was referred over the phone as “the fat guy.”130 According to court documents, in March 2013, this person was identified by British authorities as Portuguese national Nero Saraiva, then an active member of Kataib Al-Muhaijireen.131 As Magnus Ranstorp documented in this publication, Turkey (and especially its border region with Syria) was at the time a key hub for the flow of funds to Syria for terrorist use.132

Return to Syria

Contrary to his friends Sadjo Turé, Edgar Costa and Celso Costa, who returned to Europe in early August 2012, Nero Saraiva remained in Syria, where the situation changed almost daily. In August 2012, Saraiva’s recruiter Firas al-Absi was executed by another rebel faction,133 and his younger brother, Amr al-Absi (who was known by the kunya Abu Atheer al-Absi) merged his own group, Katibat Usood al-Sunna, with Majlis Shura Dawlat al-Islam, renaming this conglomeration al-Majlis Shura Mujahideen.134 Amr al-Absi continued to attract foreign jihadis, and like his brother, he oversaw the kidnapping or obtention from other kidnappers of journalists and aid workers, including James Foley and John Cantlie in late 2012.135 For that, Amr al-Absi earned the moniker of “kidnapper-in-chief.”136

Nero Saraiva kept himself in the company of other European jihadis he met in the Aleppo region, notably from the United Kingdom, Finland, and Sweden, and in 2013, he was spotted in Hraytan (a town just to the north of the city of Aleppo),137 where Katibat al-Muhajireen (KaM) was based under the command of Tarkhan Batirashvili, the Chechen jihadi known as Abu Omar al-Shishani.138 w

In Syria, Saraiva married a onetime Finnish nurse who had converted to Islam139 and who had traveled to Syria in November 2012. The former nurse had three children with Saraiva (born in September 2013, September 2015, and November 2017).140

In the 2012-2013 period, Saraiva was part of a group of European jihadis, which included several recruits from Finland.x Initially, he allegedly operated as a sniper,141 but he eventually became the leader of this European group.142

Their group was moving at the time between Hraytan, Anadan, and Atme in northern Syria, near the Turkish border. Saraiva acted as a guide for the Finnish newcomers: he would introduce them to people, show them the area, and help them to find houses and allegedly weapons.143

The Finnish jihadis did not seem to like Saraiva much. One of them later told the police “he lacked Islamic manners and information. He was stubborn and did not want to learn. He also interfered with other people’s behavior on Islamic issues, even though he didn’t know anything himself.”144 The former Finnish foreign fighter added, “Saraiva was very arrogant. He was driving around and if he saw some local smoking tobacco he might pull the car and have a conversation about how we can get Allah’s help.” He also said that Saraiva used his hard reputation to keep the newcomers’ equipment and cars for himself.145

Saraiva was in permanent contact with his Portuguese friends in Lisbon and London. He would ask them for money, transmit instructions given by Omar al-Shishani, or brag about his accomplishments.146 In May 2013, Saraiva asked for money to buy a car, and in August 2013, he told Sadjo Turé his group would need “100,000 [presumably euros] to buy the big chili for sparrows,” which was interpreted by Portuguese police as an anti-aircraft gun. That month, Saraiva described the sieges of Aleppo’s prison and airport: “It’s very heavy, a lot of things, there are many people shooting at us.”147 In June 2013, Saraiva mentioned a scheme used by jihadis to get new cars to the group: rent them and cross the border.148 “This is order from … the taller one … with the red hair, red beard [Abu Omar al-Shishani according to court documents]. He told me yesterday that, everyone who comes from Eurojutsto [the code they used for Europe], if they can do that they should. We need good vehicles … good stuff to clean the pigs.”149

During the summer and fall of 2013, members of the Portuguese network started to return to Syria and were reunited with Saraiva there. On June 22, 2013, Celso Costa, his wife Reema Iqbal, and their newborn son, together with Zara Iqbal (Sadjo Turé’s wife) and her son boarded a flight to Istanbul.150 However, upon arriving, Celso Costa was prevented from entering Turkey because he had passed the visa term (90 days) when he was there in 2012, and he returned to Lisbon the next day.151 The women carried on with the children, and after a couple of days in Istanbul waiting for instructions, they took a bus to Reyhanli where Saraiva helped them cross the border.152

The women’s behavior in Syria, while living in his six-room house along with nine adults and eight children, displeased Saraiva.153 On a long phone call recorded on July 28, 2013, he expressed his discontent to Celso Costa: “I’m responsible for them and they are going shopping with another brother and his wife without telling me. What the hell is that? We come here to do things right and they bring democracy to my place? … You have to speak with them or else I tell them to go somewhere else.”154

Celso Costa assured him he was going to speak with his wife.155 At the same time, he was working on a plan that would allow him to enter Turkey under a false ID.156 According to court documents, on August 10, 2013, Fabio Poças traveled to see Celso Costa in Lisbon in order to deliver the passport of Celso’s older brother Rómulo, to whom Celso resembled.157

On August 16, 2013, Celso Costa boarded a flight to Sofia, Bulgaria,158 and then a bus, entering Turkey easily after presenting Rómulo Costa’s passport at the border.159 In Istanbul, he bought a new phone and took another bus to Hatay where he contacted Saraiva, who helped him cross the border.160

In Lisbon, Fatuma Majengo gave birth to her first child with Edgar Costa. While waiting for the boy to be old enough to travel, Edgar Costa continued to work with Sadjo Turé on behalf of “the company.” In early August 2013, they allegedly started preparing the journey of two British nationals recruited by Sadjo Turé in London: Khavar Masoody and Taroughi Haydary,z whom Edgar instructed to travel with “western clothes” and a “new passport.”161

On August 21, 2013, Edgar Costa booked two plane tickets for the British duo from the United Kingdom to Portugal with 794.58 euros sent by the London-based Sadjo Turé.162 The next day, Masood and Haydary arrived at Lisbon airport, where they were picked up by Edgar Costa and Sandro Marques and taken to the Costas’ family apartment. There, they received their final instructions: once in Istanbul, they should buy new phones and separate bus tickets to Hatay where someone would pick them up to cross the border.163 On August 23, 2013, after being escorted to the airport by Edgar Costa, Masood and Haydary departed to Turkey.164

Subsequently, Saraiva sent word that the two had safely arrived in Syria.aa In London, Sadjo Turé was pleased: he complimented Edgar Costa in Lisbon and promised to send him more recruits. “The program continues,” he said.165 Through the group’s efforts, Lisbon had now become a transit hub for British foreign fighters traveling to Syria, a route that was likely to trigger less scrutiny than directly flying from the United Kingdom to Turkey. There were several reasons for this. Police in Portugal did not have legal grounds to stop such travel as it was not then a crime. Portuguese authorities were less concerned about foreign fighter travel because the Muslim community in the country was small and well-integrated. And the fact that Portugal had a relatively minor foreign fighter problem meant that arrivals from the country in Turkey likely received less scrutiny. By contrast, the United Kingdom had a much larger foreign fighter problem, with hundreds believed by the end of 2013 to have traveled to Syria.166 And as the Portuguese network knew all too well from the 2012 investigation into the Cantlie-Oerlemans abduction, U.K. police had started to make arrests in relation to jihadi activity in Syria.ab

Despite Lisbon now being used as a transit hub, Edgar Costa would not remain in Portugal much longer. In early October 2013, he was ready to travel with his wife and son. The plan was for Fabio Poças and his wife to make the trip with them. But when Poças headed to London Luton airport to take a flight to Lisbon with his pregnant British wife, he was approached by the Metropolitan Police and prevented from traveling.167 During questioning, he told British police he was Catholic and that he did not have an opinion about the situation in Syria because he had different priorities in life.168 Police took possession of his five mobile phones, a laptop, and £2,600 before letting him go.169

Four days later, Poças took a flight to Faro and then a bus to Lisbon. He stayed in Edgar Costa’s apartment. The plan was that his wife would travel separately and meet him in Turkey, but she changed her mind because she was not willing to travel alone and pregnant to an unknown country. During a heated argument over the phone, she asked for a divorce because he was going to jihad and would not be able to support her.170

On October 11, 2013, Edgar Costa, his wife Fatuma, and their son, accompanied by Poças, departed from Lisbon airport to Istanbul on different flights.171 Once in Turkey, they followed the same route to Syria as the others had.172

With most of the group now in Syria, Sadjo Turé received what for him was good news regarding his case in the United Kingdom. On November 11, 2013, his alleged co-conspirators in the kidnapping of John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemans in Syria in the summer 2012—Shajul Islam, Najul Islam, and Jubayer Chowdhury—were released and all charges against them dropped.173 It was publicly stated by authorities that the prosecution had relied wholly on John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemans’ testimony but had been unable to call either of them to testify.174 ac During a phone call, Sadjo Turé remarked to his brother Cassimo, “the doc and his brother” got out because there was no evidence. “The journalists said nothing.”175 ad

Around the same time, in the United Kingdom, Sadjo Turé recruited another candidate to jihad and sent him to Lisbon, asking his older brother, Cassimo, to buy plane tickets to Istanbul for the recruit and look after him while in Portugal.176 However, when the young British man arrived in Turkey, he was prevented from entering the country.177

Soon, the only two members of the Portuguese network still in Europe joined their friends in Syria. On February 26, 2014, Sandro Marques, his wife Mayibongue Sibanda,ae and their daughter boarded a flight to Istanbul.178 They entered Syria through Tell Abyad on March 7.179 Finally, according to court documents, in late March 2014, Sadjo Turé was able to elude surveillance by authorities in the United Kingdom and get to France.180 He entered Syria on April 1, 2014.181 Like the others before them, he and Sandro Marquez allegedly joined Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar.182

Why, despite the active Portuguese investigation, was the group allowed to travel to Syria? According to Portuguese law at the time of their departure, it was not a crime to travel to a conflict zone with the purpose of joining a terrorist organization or obtain military training. It was only in June 2015 that the anti-terrorism law was changed to criminalize traveling abroad to join a terrorist group and also the public apology of terrorism.183 Soon after the change in law, Portuguese authorities issued European and International Arrest Warrants against all eight male members of the Portuguese Islamic State cell.184 The case underlined how important such legislation was in providing European countries powers to stem the tide of foreign fighter travel.

Online Monitoring

There was much change in Syria during the course of 2013. In March 2013, KaM had merged with two other groups to become Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar. In November of that year, its leader, Omar al-Shishani, swore allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of what was then called the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).185 The group of Portuguese followed suit.186

After the Portuguese group returned to Syria, investigators were only able to track their activities and whereabouts by monitoring social media and their irregular phone calls to their families in which they would usually say they were working in Turkey187 as well as intelligence provided by Western allies.188 On his Facebook page in early 2014, Fabio Poças identified himself as a “mujahid/foot soldier/sniper” of “Dawlah Islamiah fi Iraq wa Shaam” living in Aleppo.189 He would show himself in Al Bab, and in January 2014, he posted pictures on a “150 cars convoy traveling throughout the desert.”190 He called it “Dawla Convoy” going from Aleppo to Raqqa.191 That same month, ISIL fought other rebel groups in Raqqa and took definitive control of the city, making it its capital.192

On April 1, 2014, a video of a Western jihadi wearing a black balaclava standing on the banks of the Euphrates was posted on FISyria.com,193 the official website for Abu Omar al-Shishani’s faction.194 In the video, he was identified as Abu Isa Andaluzi from Dawlat al Islamyia, (or in other words ISIL). Speaking in English, he appealed for Ukrainian Muslims to support jihad in Syria and asked Muslim women to travel to the region where sharia law was being implemented. Portuguese authorities immediately recognized him as Celso Costa.195

Around this time, Fabio Poças, Celso and Edgar Costa, Sadjo Turé, and Sandro Marques had settled in Manbij with their families.196 On June 11, 2014, Poças posted a video on Facebook showing ISIL militants in Manbij celebrating the group’s conquest of the city of Mosul.197 He was the most active on social media, regularly posting pictures of himself, face uncovered, alone or in the company of known jihadis like the former German rapper Denis Cuspert.198 af

Nero Saraiva allegedly continued to play a senior role within ISIL. Information shared with Portuguese authorities by intelligence agencies on May 26, 2014, indicated that he held a leadership role within the organization, which allowed him to actively participate “in planning, and execution, of all actions perpetrated by ISIL, namely the ones directed against western targets, including hostage taking, kidnaps and eventually other actions against targets or interests outside Syria.”199 According to the same information, his group had been relocated to Raqqa.200

Two months later, on July 10, 2014, Saraiva shared his cryptic post on Twitter and Facebook: “Message to America the Islamic State is making a new movie. Thank u for the actors.”201 Forty days later, on August 19, 2014, the Islamic State published the execution video of James Foley with the title “Message to America.” As already outlined, Saraiva’s tweet gained a new meaning. For intelligence and police officers, it was clear he had advance knowledge of James Foley fate.202 And he was soon connected by Western intelligence services to the group of Mohammed Emwazi, the terrorist known as Jihadi John.203

When the James Foley execution video was released, Saraiva was living in Manbij. According to The Sunday Times, Ahmad Walid Rashidi, one of the few Western hostages held captive by the Islamic State to be freed alive, believes that during the summer of 2014 he saw Saraiva at a police and judicial building used by the terrorist group in Manbij: “He had a gun at the office,” he stated.204

Saraiva’s cryptic “Message to America” on social media was not immediately reported on by media organizations. But when his tweet was quoted in the press in November 2014,205 Saraiva disappeared from social media as his accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram were blocked.206 His whereabouts became unknown. Fábio Poças described him as a “lone wolf” to whom he had no access.207 His family outside the conflict zone lost track of him.208 For the next four years, he would be mentioned occasionally in reports shared by intelligence agencies when a prisoner or an Islamic State repentant claimed to have seen him in a certain place.209

The Fate of the Network

As the international campaign to defeat the Islamic State developed, the Portuguese Judiciary Police started to receive unconfirmed reports that Sandro Marques had died in coalition bombings in August 2014.210 In early September 2015, authorities intercepted several conversations in which the mother and father of Sadjo Turé talked with relatives about their son’s death in Syria.211

Two months later, on November 12, 2015, the eve of the Paris terrorist attacks, the Costa brothers appeared in an Islamic State propaganda video published online by Furat Media, face uncovered.212 According to the video, the images were recorded during the Eid al Adha celebration that took place between September 23 and 27, 2015. “We sacrifice the sheep according to the Sunnah, but we also kill kafir,” Celso Costa said, with his brother at his side.213

By the time the Syrian Democratic Forces freed Manbij in August 2016, Edgar Costa, Celso Costa, and Fábio Poças had left the town with their families and moved to Raqqa.214 The Costa brothers contacted their father and older brother, Rómulo Costa, in order to organize an escape from Islamic State territory, along with their wives and children.215 Both brothers had taken second wives in Syria.ag

As for Poças, he never showed any intention to leave.216 Like his friends, Poças had married in Syria, in his case to Angela Barreto,ah a Portuguese-Dutch woman who had traveled alone to Syria to meet him in August 2014.217 They had a son and a daughter while in Syria. Poças also managed to convince his first wife, Ruzina Khanam,ai to join him in October 2015 with their child.218 When the SDF launched the offensive to take Raqqa in June 2017, Poças and his wives and children moved to the Al Mayadeen area.219 When that town was taken, they ran from village to village. Eventually, the group split. Fabio Poças was killed while he was crossing the Euphrates, a family member told the author.220 Ruzina Khanam and her daughter’s fate is unknown. Angela Barreto and her children then stayed under Nero Saraiva’s responsibility and went to live with him and his family in Saffa.221 She and Saraiva would eventually marry and move to Baghouz in late 2018.222

In early August 2018, the Judiciary Police received through international cooperation channels information about Edgar Costa presence along the Euphrates, near the Iraqi-Syrian border.223 That same intelligence mentioned he was establishing contacts with the Islamic State hierarchy and his intention to leave Syria.224 At the time, he had sent to Portugal a list of names of women and children so that his father could buy plane tickets for them all. The plan was for them to travel directly to Angola, where the family patriarch had business interests related to oil exploitation.225 But his father had problems understanding the Arabic names and was not able to deliver the tickets.226 Eventually Edgar and Celso Costa’s contact with their family in Portugal and the United Kingdom stopped.227 In September 2018, Portuguese authorities received information through international cooperation channels that Edgar and Celso Costa had been killed.228 Their wives and children were captured by the SDF and sent to Roj and Ain Issa camps.229

Returning Edgar and Celso’s wives and children to Europe became a priority for the Costa family. The patriarch, Manuel da Costa, discussed it several times on the phone with his son, Rómulo, who was living in London and who for several years had not been allowed to leave the United Kingdom because he was suspected of terrorism financing.230 But in June 2019, with all charges dropped, he traveled to Portugal for the first time in almost 10 years—only to be detained231 and charged later with terrorism support and financing.232 The Judiciary Police and the Public Prosecutor believe that, back in 2014, he willingly gave his passport to his brother Celso Costa, so that the later could travel to Syria.233 Rómulo Costa denies all charges234 with his lawyer, Lopes Guerreiro, arguing that there is no concrete evidence of his alleged crimes, only “suppositions.”235 Rómulo Costa remains in detention while awaiting trial, with proceedings scheduled to start on September 8, 2020.

As already outlined, also among those charged and facing trial is Cassimo Turé, Sadjo Turé’s older brother. The Portuguese Public Prosecutor charged him for support of a terrorist organization, recruitment, and terrorism financing for what is alleged to be his role in obtaining money from fraudulent schemes and his help in receiving in Lisbon the recruits sent to Syria.236 Cassimo Turé denies all charges and claims he was just doing his brother a favor, not knowing Sadjo’s exact goals.237 Due to his cooperation with authorities, Cassimo Turé was allowed to await trial while living at liberty in London.238

In the end, Nero Saraiva, the first to arrive in Syria, was the only one of the adult male Syria travelers to survive. In early 2019, while walking among the tents in a makeshift Islamic State encampment in Baghouz, he and his most recent wife, Angela Barreto, were hit by bomb shrapnel. Saraiva was severely injured in his legs. Angela was hit in her head. A few days later, while in their tent, they were hit again by coalition bombing: this time, the Portuguese jihadi was injured in his head and shoulder, and collapsed.239 A daughter of Angela’s was also hit by shrapnel in her head.240

With the injured allowed to leave Baghouz, they left in March 2019. Angela was sent with the children to the Syrian Democratic Forces-run Al-Hol camp, where her older daughter died from her injuries.241 Saraiva was taken to a prison hospital.242 Debriefed by coalition forces, he claimed to have five wives and ex-wives and a total of 10 children.243

Six months later, fully recovered from his injuries, he was interviewed by a Kurdish news agency and confirmed what Portuguese investigators already knew about his steps until he entered Syria in 2012.244 During that interview, Saraiva claimed that in late 2014, he was part of a unit of foreigners called Katibat Musab al-Zarqawi and that for three months, he was tasked with registering new recruits that came from Europe.245 He claimed that he then changed jobs and started doing reconnaissance “in all areas.”246 He also claimed that following an injury, he spent almost one year in Mosul for treatment, before returning to Raqqa and reverting to his reconnaissance duties until 2016.247After this, he claimed he stayed most of the time at home or on the run from airstrikes. He never mentioned any involvement in terrorist activities, fighting, kidnappings, or the executions of foreigners.248

Following his capture, Saraiva remained under SDF detention in Syria until he was transferred to coalition forces’ custody in Iraq.249 He has been questioned there several times in the last few months (spring/summer 2020) about his role within the Islamic State and his knowledge about Western citizens’ kidnappings and executions250 and is considered one of “the most high value suspected ISIS detainees.”251

During that period, he asked Portuguese authorities to be repatriated to Portugal via the International Red Cross.252 With the international arrest warrant issued for him by Portuguese authorities, he could be extradited to Portugal to stand trial and answer for his alleged crimes. Alternatively, he could face trial and the death penalty in Iraq.253 A key question will be whether he eventually reveals what he knows about the fate of Western hostages.

Conclusions

This case study sheds significant light on the foreign fighter pipeline that operated in the last decade between Europe and Syria and the challenges authorities faced in stopping the flow. The foreign fighter pipeline to Syria involved networks that transcended national borders in Europe with Lisbon becoming a transit hub for British fighters. But different laws in different countries when it came to foreign fighter travel hampered authorities’ ability to slow or shut down the pipeline. The case highlights the importance of legislation against foreign fighter travel as Portuguese investigators were previously powerless to stop the travel, only granted those powers in 2015 when the anti-terrorism law was updated to criminalize travel to a conflict zone and apology for terrorism. Notwithstanding the legal limitations placed on Portuguese authorities, questions should be asked about whether more could have been done to stop the members of the network moving back and forth between Syria and Europe.

The case study underlines the fundamental role in information sharing between countries in investigating and dismantling terrorist networks. Portuguese authorities only became aware of the existence of a Portuguese jihadi network when they were informed by their British counterparts.

The case study also illustrates the importance of fraudulent schemes to raise money to finance foreign fighter travel from Europe to Syria, especially the apparent ease with which they managed to obtain state subsidies and loans available to foreign students in the United Kingdom.aj As outlined above, the network was able to send thousands of euros to Turkey and Syria through money transfer agencies, even after they had been put under investigation.

The case study also points to the foreign fighter mobilization to Syria being self-propelled to a significant degree. The Portuguese extremists profiled in this case study exhibited much self-initiative and had to make ad hoc arrangements to get to Syria without raising attention. They tended to find the cheapest way to travel, learning over time how to identify different routes and points of entry in Turkey.

Once on the ground in Syria, Europeans tended to group together and recruit friends they left behind in Europe, according to the picture painted by this case study. The ones who arrived in Syria in early 2012 and 2013 ended up playing key roles within the Islamic State. They moved between different locations, mostly between Hraytan, Manbij, and Raqqa.

The case study illustrates how foreign fighter networks created connectivity between extremists in Europe and jihadis on the ground in Syria/Iraq, with in this case Saraiva allegedly functioning as a magnet drawing back members of the network to the jihadi battleground. The fact that the network was composed of several sets of brothers and childhood friends illustrates the importance of kinship and friendship bonds in European jihadi networks.254

Women had an important role in this foreign fighter network as well and appear to have been willing to travel to a conflict zone, with almost all bringing their children. One of the women traveled while her husband was under surveillance in the United Kingdom, and another proceeded with her journey even when her husband was stopped at the Turkish border. The case illustrated their importance and that women joined the jihad out of their own free will rather than, as sometimes is assumed, forced by their husbands to travel. To the contrary, the wives also help propel the jihadi journey of their husbands.

The case illustrates the importance of social media to gather evidence not merely on foreign fighter presence in Syria, but also of their activities. There is a fundamental need for social media companies to cooperate with national authorities who are looking to build judicial cases against their respective foreign fighters.

Finally, the Portuguese case might provide an example regarding what to do to the thousands of European jihadis detained in Syria and Iraq. Nero Saraiva, the most senior alleged member of the network, is the subject of an international arrest warrant issued by Portuguese authorities and is set to go on trial in absentia in September. There seems to be no reason why that warrant could not be carried out so that he could stand trial for his crimes. CTC

Nuno Tiago Pinto is an investigative reporter and chief editor at Sábado news magazine. He authored the books Os combatentes portugueses do Estado Islâmico (The Portuguese fighters in the Islamic State); Heróis Contra o Terror: Mário Nunes, o português que foi combater o Estado Islâmico (Heroes Against Terror: Mário Nunes, the Portuguese that went to fight the Islamic State); and Dias de Coragem e Amizade – Angola, Guiné e Moçambique: 50 Histórias da Guerra Colonial (Days of Courage and Friendship – Angola, Guinea and Mozambique: 50 Stories from Portuguese Colonial War). Follow @ntpinto23

© 2020 Nuno Tiago Pinto

Substantive Notes

[a] The group of four British jihadis of the Islamic State were dubbed the “Beatles” by their captives due to their accent. They were nicknamed “John,” “Paul,” “Ringo,” and “George” like the famous rock band. They were identified as Mohammed Emwazy, Aine Davis, Alexanda Kotey, and El Shafee Elsheikh, respectively. Tara John, “What to Know About the ISIS ‘Beatles’ Captured in Syria,” Time, February 9, 2018; Charlie Savage and Eric Schmitt, “Trump Officials Reconsider Prosecuting ISIS ‘Beatles,’” New York Times, January 31, 2020.

[b] There are numerous examples of siblings being recruited into terrorist networks. Four pairs of brothers were involved in the August 2017 attacks in Catalonia. In addition, siblings were involved in the 2013 Boston bombings, the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks, and the November 2015 Paris attacks. Fernando Reinares and Carola García-Calvo, “‘Spaniards, You Are Going to Suffer:’ The Inside Story of the August 2017 Attacks in Barcelona and Cambrils,” CTC Sentinel 11:1 (2018): p. 7; Mohammed M. Hafez, “The Ties that Bind: How Terrorists Exploit Family Bonds,” CTC Sentinel 9:2 (2016).

[c] Sadjo Turé, born December 12, 1979, Guinea-Bissau. Also known as Abu Yusha Al Andalus. All footnotes listing date/place of birth and (where applicable) the aliases of individuals mentioned in this article are based on information from Portuguese court documents. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB.

[d] Cassimo Turé, born July 12, 1975, Guinea-Bissau.

[e] Sandro Alexandre Silva dos Santos Marques, born November 4, 1978, Lisbon; also known as Mohamed, Primeiro, and Abu Yaminah Al Portughal.

[f] Rómulo António Céu Rodrigues da Costa, born March 22, 1979, Lisbon, Portugal.

[g] Edgar Augusto Céu Rodrigues da Costa, born July 27, 1983, Lisbon, Portugal; also known as Abu Zakarya Al Andalus.

[h] Celso Emanuel Céu Rodrigues da Costa, born April 15, 1986, Lisbon, Portugal, also known as Abu Isa Al Andalus.

[i] Nero Patricio Contreiras Saraiva, born August 16, 1986, Luanda, Angola; also known as Abu Yakoub Al Andalus.

[j] Fábio Ricardo Dias Neiva Poças, born August 26, 1992, Benguela, Angola; also known as Abdurahman Al Andalus.

[k] On January 6, 2011. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 1,372.

[l] Fatuma Athumani Majengo, born November 20, 1993, Singida, Tanzania.

[m] Reema Iqbal, born October 7, 1988, Pakistan; British national, also known as Umm Ibrahim Pakistani and Sakiha Ahmad Mahmod.

[n] Zara Iqbal, born November 21, 1989, Pakistan; British national, also known as Umm Yusha Pakistani and Aisha Ahuma Mahmod. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,094.

[o] Shamila Iqbal, born May 25, 1986, Pakistan. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 89.

[p] Shajul Islam, born March 18, 1986. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 90.

[q] At the time, Ahrar al-Sham was one of the main Islamist groups fighting the Syrian government.

[r] U.K. authorities suspected that Shajul Islam traveled to Turkey and then crossed into Syria were he allegedly joined the jihadi group responsible for the abduction of John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemans. “Syria kidnap case against doctor dropped by prosecution,” BBC, November 11, 2013.

[s] Jubayer Chowdhury, born July 15, 1988.

[t] Najul Islam, born February 15, 1981.

[u] Oerlemans was later killed while reporting in Libya in 2016. “Dutch photojournalist Jeroen Oerlemans shot dead in Libya by sniper,” Associated Press, October 2, 2016.

[v] Magalhães was also the Public Prosecutor in charge of the Portuguese investigation that helped dismantle an Islamic State European cell. Nuno Tiago Pinto, “The Portugal Connection in the Strasbourg-Marseille Islamic State Terrorist Network,” CTC Sentinel 11:10 (2018); Nuno Tiago Pinto and Carlos Rodrigues Lima,“Ministério Público acusou oito jihadistas portugueses de terrorismo,” Sábado, December 17, 2019; Nuno Tiago Pinto, “Acusado de recrutar para o Estado Islâmico,” Sábado, March 28, 2018.

[w] Tarkhan Batirashvili was a former Georgian military officer who traveled to Syria in 2012 where he led Jaysh al-Mujahireen wal-Ansar (Army of Emigrants and Supporters). Following his bay`a (oath of allegiance) to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, he became the Islamic State’s overall on-the-ground military commander. Hassan Hassan and Michael Weiss, ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror (New York: Regan Arts, 2015), pp. 123-125; “Tarkhan Tayumurazovich Batirashvili,” United Nations Security Council.

[x] One was the Finnish-Namibian jihadi Muhammed Shuuya, also known by his kunya Abu Salamaj al-Finlandi. Saraiva’s wife, the former Finnish nurse, was close friends with Shuuya’s wife (also a convert) who traveled with Shuuya to Syria in the summer of 2013. In Syria, Shuuya and Saraiva became close friends, and according to information provided to Finnish police by Islamic State returnees, at a certain point they all lived together. Shuuya was the emir of the group of Europeans until his death in July 2013, after which Saraiva took his place. Saraiva was also connected to Hassan Al Mandlawi, a Swedish jihadi sentenced to life in prison for participating in the beheading of two prisoners in the Aleppo region in 2013. He and Saraiva were pictured together. Nuno Tiago Pinto, “O mais perigoso terrorista português do Estado Islâmico preso na Síria,” Sábado, August 29, 2019; Sami Sillanpää, “ISIS-VAIMO JA SEN MIES,” Helsingin Sanomat, September 1, 2019; Gothenburg Court of Law, case number B 9086-15; Mika Viljakainen, “Espoolainen lähihoitaja Antti tuli uskoon vuonna 2012, kaksi vuotta myöhemmin hän oli Isis-taistelija – tässä koko uskomaton tarina,” Ilta-Sanomat, January 18, 2020.

[y] Khavar Usman Masood, born October 4, 1992, in Barking, United Kingdom. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 2,592.

[z] Taroughi Haydari, born January 1, 1996, Jalalabad, Afghanistan. Ibid., p. 2,592.

[aa] The current status and location of the British duo is not publicly known.

[ab] It is important to note that the United Kingdom had yet to crack down hard on foreign fighter travel to Syria. A study published in late 2013 noted that “like their continental counterparts, British authorities face problems when it comes to the prosecution of fighters. Only a few returnees have been arrested. A famous case involved the kidnapping of a British freelance photographer, John Cantlie, and a Dutch journalist, Jeroen Oerlemans, for a week in Syria in July 2012. … However, besides these arrests, which were clearly connected to a very specific offence, namely kidnapping, ‘others who have been taking part in the armed struggle against the Assad regime are not deemed to be doing anything illegal.’” Edwin Bakker, Christophe Paulussen, and Eva Entenmann, “Dealing with European Foreign Fighters in Syria: Governance Challenges & Legal Implications,” ICCT, December 2013, p. 20.

[ac] John Cantlie returned to Syria in November 2012 and was abducted for the second time. He was then with American journalist James Foley. Cantlie would only resurface again in an Islamic State video in September 2014. According to The Times, Oerlemans “refused to give evidence for fear that it would further endanger” Cantlie. James Gordon Meek and Rhonda Schwartz, “Missing British Hostage John Cantlie Surfaces Alive in New ISIS Video,” ABC News, September 18, 2014; Catherine Philp and David Brown, “Kidnap trial doctor treats gas victims,” Times (London), April 7, 2017.

[ad] Following his release, Shajul Islam returned to Syria where he started to work as a doctor in Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham-controlled areas. Shamila Iqbal’s location is not publicly known. Philp and Brown.

[ae] Mayibongwe Sibanda, born November 13, 1990, Zimbabwe, British citizen. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,095.

[af] Denis Cuspert, known as Deso Dogg and Abu Talha al Almani.

[ag] During their second trip to Syria, both Costa brothers took second wives. Celso Costa married a German woman named Sabina Tafilovij while Edgar Costa married an Indonesian named Seri Kejiki. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,246.

[ah] Angela Sofia Barreto Dionísio, born August 2, 1995, the Netherlands. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,247.

[ai] Ruzina Khanam, born January 26, 1992, United Kingdom. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,247.

[aj] A variety of fraudulent schemes have been observed in European countries with respect to Islamic State-linked individuals. Magnus Ranstorp, “Microfinancing the Caliphate: How the Islamic State is Unlocking the Assets of European Recruits,” CTC Sentinel 9:5 (2016); Mette Mayli Albæk, Puk Damsgård, Mahmoud Shiekh Ibrahim, Troels Kingo, and Jens Vithner, “The Controller: How Basil Hassan Launched Islamic State Terror into the Skies,” CTC Sentinel 13:5 (2020).

Citations

[1] Hugo Franco and Raquel Moleiro, “Estado Islâmico: um tweet que causou suspeita,” Expresso, November 1, 2014.

[2] “IS Beheads Captured American James Wright Foley, Threatens to Execute Steven Joel Sotloff,” SITE Intelligence Group, August 19, 2014.

[3] Robert Verkaik, Jihadi John: The Making of a Terrorist (London: Oneworld Publications, 2016), p. 124; Franco and Moleiro, “Estado Islâmico: um tweet que causou suspeita;” Nuno Tiago Pinto, “O mais procurado terrorista português,” Sábado, April 11, 2019.

[4] Nero Saraiva Islamic State file, kindly shared with the author by Georg Heil from WDR television and Volkmar Kabish from NDR radio and Sueddeutsche Zeitung, which first reported about the Islamic State’s cache of files.

[5] Nuno Tiago Pinto, “Nero Saraiva envolvido em rapto de jornalista britânico,” Sábado, March 22, 2016.

[7] Nuno Tiago Pinto, Os combatentes portugueses do Estado Islâmico (Lisbon: A Esfera dos Livros, 2015).

[8] Ibid.

[10] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,169.

[11] Ibid., p. 9,151.

[12] Ibid., p. 913.

[13] Ibid., p. 9,106.

[14] Nuno Tiago Pinto, “Do hip-hop para a jihad,” Sábado, November 19, 2015.

[15] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,099.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., p. 9,100.

[18] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Valentina Marcelino, “Confirmada morte de mais um jihadista português na Síria,” Diário de Notícias, November 20, 2015; Hugo Franco, “Dois irmãos portugueses dados como mortos na Síria. Eram jiadistas do Daesh,” Expresso, September 22, 2018; Valentina Marcelino, “Só um dos jihadistas portugueses estará ainda vivo,” Diário de Notícias, April 6, 2019.

[22] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, pp. 9,347-9,564.

[24] Author interview, Portuguese counterterrorism officials, June 2020; Nuno Tiago Pinto, “Porta aberta à extradição de Nero Saraiva para Portugal,” Sábado, July 2, 2020; Rohit Kachroo, “London man believed to be ‘most high value suspected ISIS detainee’ worldwide could face death penalty in Iraq,” ITV News, July 2, 2020.

[26] Pinto, “Porta aberta à extradição de Nero Saraiva para Portugal;” Kachroo, “London man believed to be ‘most high value suspected ISIS detainee’ worldwide could face death penalty in Iraq.”

[27] A series of articles were published by the author in cooperation with Dipesh Gadher from The Sunday Times, Sami Sillanpää from Helsingin Sanomat, and Rohit Kachroo from ITV News. Nuno Tiago Pinto, “Quem são as mulheres e os filhos portugueses da jihad,” Sábado, October 25, 2018; Dipesh Gadher, Tom Harper, and Richard Kerbaj, “Up to 80 ISIS brides stream back to UK,” Sunday Times, October 28, 2018; Dipesh Gadher and Tom Harper, “Jihadi brides are widows now and they want to come home,” Sunday Times, October 28, 2018; Dipesh Gadher, “Sisters went to Syria ahead of men,” Sunday Times, November 11, 2018; Gadher, “We’ll take your babies to Syria’s war, said my jihad-crazy friends;” Nuno Tiago Pinto, “Radicais de longa data,” Sábado, November 29, 2018; Pinto, “O mais perigoso terrorista português do Estado Islâmico preso na Síria;” Sami Sillanpää, “ISIS-VAIMO JA SEN MIES,” Helsingin Sanomat, September 1, 2019; Gadher, “London Isis chief captured in Syria may know what happened to hostage John Cantlie;” Nuno Tiago Pinto, “A ‘empresa’ que recrutava jovens ingleses para a jihad,” Sábado, December 12, 2019; Rohit Kachroo, “London man who fought for so-called Islamic State and recruited others named in joint ITV News investigation,” ITV News, December 12, 2019; Pinto, “Porta aberta à extradição de Nero Saraiva para Portugal;” Kachroo, “London man believed to be ‘most high value suspected ISIS detainee’ worldwide could face death penalty in Iraq.”

[28] Pinto, “Do hip-hop para a jihad.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] Hugo Franco and Raquel Moleiro, “Matar e morrer por Alá: cinco portugueses no Estado Islâmico,” Expresso, October 2014.

[31] Author interview, family member, August 2019.

[32] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,224.

[33] Ibid., p. 8,286, Cassimo Turé deposition, August 28, 2019.

[34] Nuno Tiago Pinto, “O sexto elemento da célula de Londres,” Sábado, April 16, 2015.

[35] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 8,286, Cassimo Turé deposition, August 28, 2019.

[36] Pinto, “Do hip-hop para a jihad.”

[37] Ibid.

[38] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 8,286, Cassimo Turé deposition, August 28, 2019.

[39] Pinto, “O mais procurado terrorista português.”

[40] Ibid.

[41] Gadher, “London Isis chief captured in Syria may know what happened to hostage John Cantlie.”

[42] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,484.

[43] Nuno Tiago Pinto, “Mato qualquer um que lute contra o Islão,” Sábado, October 9, 2014.

[44] Franco and Moleiro, “Matar e morrer por Alá: cinco portugueses no Estado Islâmico.”

[45] Ibid.

[46] Gadher, “We’ll take your babies to Syria’s war, said my jihad-crazy friends.”

[47] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 570.

[48] Ibid., p. 9,171.

[49] Pinto, “Do hip-hop para a jihad.”

[50] Ibid.

[51] Gadher, “We’ll take your babies to Syria’s war, said my jihad-crazy friends;” Pinto, “Radicais de longa data.”

[52] Ibid.

[53] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 1,995.

[54] Ibid., p. 2,190.

[55] Ibid., Appendix C, p. 52.

[56] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, Appendix C, p. 130.

[57] Ibid., p. 9,106.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Gadher, “We’ll take your babies to Syria’s war, said my jihad-crazy friends;” Pinto, “Radicais de longa data.”

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 90.

[69] Ibid., p. 9,099.

[70] Ibid., p. 9,107.

[71] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 1,549.

[72] Beritan Sarya, “Portuguese ISIS member under SDF arrest for 6 months,” ANF News, September 18, 2019. See embedded video.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Nero Saraiva Islamic State file kindly shared with the author by Georg Heil from WDR television and Volkmar Kabish from NDR radio and Sueddeutsche Zeitung, which first reported about the Islamic State cache of files.

[75] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,102.

[76] Sarya.

[77] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,107.

[78] Produced by the Islamic State General Border Administration, these files were the personal records of Islamic State fighters filled out mostly between 2013 and 2014. Each form contained details like names, addresses, occupations, education levels, point of entry, and facilitator. Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler, The Caliphate’s Global Workforce: An Inside Look at the Islamic State’s Foreign Fighter Paper Trail (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2016).

[79] Nero Saraiva Islamic State file kindly shared with the author by Georg Heil from WDR television and Volkmar Kabish from NDR radio and Sueddeutsche Zeitung, which first reported about the Islamic State cache of files.

[80] Pinto, “Nero Saraiva envolvido em rapto de jornalista britânico.”

[81] Ibid.; Kyle Orton, “Death of a Caliphate Founder and the Role of Assad,” Kyle Orton’s blog, March 10, 2016.

[82] “Syria Kidnap case against doctor dropped by prosecution,” BBC, November 11, 2013.

[85] “British hostage John Cantlie feared beheading in Syria,” BBC, August 5, 2012.

[86] Sengupta.

[87] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 88.

[88] Sengupta; “Reasons for UK doctor’s erasure are withheld on grounds of ‘confidentiality,’” BMJ, March 30, 2016.

[89] “Man Charged in UK over Syria kidnap,” BBC, November 15, 2012.

[90] Caroline Davies, “Four held in London over suspected Syria links,” Guardian, January 10, 2013; Raffaello Pantucci “British Fighters Joining the War in Syria,” CTC Sentinel 6:2 (2013).

[91] Tom Whitehead, “Four men arrested under terror laws after kidnap of journalist,” Telegraph, January 10, 2013; Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, pp. 1-2.

[92] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, pp. 1-2.

[93] Ibid.

[94] Ibid.

[95] Ibid.

[96] Ibid.

[97] Ibid.

[98] Ibid., pp. 5-15.

[99] Ibid., p. 20.

[100] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 27.

[101] Ibid., p. 92.

[102] Birth certificate 14/2012, Consular Section Portugal Embassy in Ankara, August 9, 2012. Copy obtained by the author at Instituto dos Registos e Notariado.

[103] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 1,541.

[104] Ibid., p. 9,099.

[105] Ibid., pp. 1-2.

[106] Ibid., pp. 92, 118, Appendix B, p. 3.

[107] Ibid., p. 119.

[108] Ibid., p. 172.

[109] Ibid., p. 173.

[110] Ibid.

[111] Ibid.

[112] Ibid., p. 1,301.

[113] Ibid., p. 2,002.

[114] Ibid., pp. 302, 440.

[115] Ibid., p. 2,752.

[116] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 130.

[117] Ibid., p. 174.

[118] Ibid., p. 114.

[119] Ibid., p. 302.

[120] Ibid., p. 303.

[121] Ibid.

[122] Ibid., p. 322.

[123] Ibid., p. 800.

[124] Ibid., p. 801.

[125] Gadher, “We’ll take your babies to Syria’s war, said my jihad-crazy friends;” Pinto, “Radicais de longa data.”

[126] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,152.

[127] Ibid., p. 801.

[128] Ibid., pp. 2,997; 2,999; 3,065; 4,368; 4,435.

[129] Ibid.

[130] Ibid.

[131] Ibid., p. 802.

[133] Sengupta.

[134] Orton; Pinto, “Nero Saraiva envolvido em rapto de jornalista britânico.”

[135] Ibid.; Louisa Loveluck, “Senior Isil operative responsible for murder of Western journalists killed in Aleppo air strike,” Telegraph, March 4, 2016; Ben Taub, “Journey to Jihad,” New Yorker, May 25, 2015.

[138] Orton.

[139] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,379; Pinto, “O mais perigoso terrorista português do Estado Islâmico preso na Síria;” Sillanpää.

[140] Ibid.

[141] Pinto, “O mais perigoso terrorista português do Estado Islâmico preso na Síria;” Sillanpää.

[142] Ibid.

[143] Ibid.; Finnish National Bureau of Investigation, case number 2400/R/234/14, November 24, 2016.

[144] Finnish National Bureau of Investigation, case number 2400/R/234/14, November 24, 2016.

[146] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,152.

[147] Ibid., p. 2,523; Appendix C, p. 77.

[148] Ranstorp.

[149] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,397.

[150] Ibid., p. 1,940.

[151] Ibid., p. 9,176.

[152] Ibid., pp. 1,834-1,835.

[153] Ibid., p. 2,272.

[154] Ibid., p. 2,273; Appendix C, p. 129.

[155] Ibid.

[156] Ibid., Appendix C, p. 135.

[157] Ibid., p. 9,418.

[158] Ibid., p. 2,417.

[159] Ibid., p. 8,137.

[160] Ibid., p. 2,494.

[161] Ibid., p. 2,493.

[162] Ibid., p. 2,570.

[163] Ibid.

[164] Ibid., pp. 2,591; 2,737.

[165] Ibid., pp. 2,591; 2,577; 2,737.

[167] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,062.

[168] Ibid.

[169] Ibid.

[170] Ibid., Appendix C, p. 331.

[171] Ibid., p. 3,108.

[172] Ibid., p. 9,131.

[174] Ibid.; “Syria Kidnap case against doctor dropped by prosecution.”

[175] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,258.

[176] Ibid., p. 9,131.

[177] Kachroo, “London man who fought for so-called Islamic State and recruited others named in joint ITV News investigation;” Pinto, “A ‘empresa’ que recrutava jovens ingleses para a jihad.”

[178] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,596.

[179] Sandro Marques Islamic State file, kindly shared with the author by Georg Heil from WDR television, Volkmar Kabish from NDR radio, and Sueddeutsche Zeitung.

[180] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, pp. 3,726; 9,486.

[181] Sadjo Turé Islamic State file, kindly shared with the author by Georg Heil from WDR television, Volkmar Kabish from NDR radio, and Sueddeutsche Zeitung.

[182] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,175.

[183] Law number 60/2015, June 24.

[184] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,937.

[186] Pinto, “Mato qualquer um que lute contra o Islão.”

[187] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,437.

[188] Ibid., p. 3,726.

[189] Ibid., p. 3,459.

[190] Ibid., p. 3,532.

[191] Ibid.

[192] “Raqqah: Capital of the Caliphate,” RAND, National Security Research Division.

[194] Joscelyn.

[195] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,709.

[196] Pinto, “Mato qualquer um que lute contra o Islão.”

[197] “June 2014: ISIS Insurgents celebrate Mosul takeover,” Washington Post, June 12, 2014.

[198] Pinto, “Mato qualquer um que lute contra o Islão.”

[199] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 3,728.

[200] Ibid.

[201] Franco and Moleiro, “Estado Islâmico: um tweet que causou suspeita.”

[202] Ibid.; author interview, intelligence officer, December 2014.

[203] Gadher and Hookham.

[204] Ibid.; Dipesh Gadher, “UK terrorists turn Isis stronghold into ‘little London,’” Sunday Times, December 14, 2014.

[205] Gadher, “UK terrorists turn Isis stronghold into ‘little London;’” Franco and Moleiro, “Estado Islâmico: um tweet que causou suspeita.”

[206] Hugo Franco and Raquel Moleiro, Os jiadistas portugueses (Lisbon: Lua de Papel, 2015).

[207] Pinto, Os combatentes portugueses do Estado Islâmico; author interview, Fábio Poças, December 2014.

[208] Author interview, family member, April 2019.

[209] Author regular interviews with police and intelligence officials between 2015 and 2019.

[210] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 4,791.

[211] Ibid., p. 4,836.

[212] Pinto, “Do hip-hop para a jihad.”

[213] Ibid.

[214] Author interview, family member, September 2019.

[215] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 6,039.

[216] Author interview, family member, September 2019.

[217] Author interview, Fabio Poças, January 2015.

[218] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 5/13.1JBLSB, p. 9,247.

[219] Author interview, family member, September 2019.

[220] Ibid.

[221] Ibid.

[222] Pinto, “O mais perigoso terrorista português do Estado Islâmico preso na Síria;” Sillanpää.