Abstract: As a result of military offensives on opposite sides of the Euphrates River by Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Assad regime, the Islamic State has now been all but territorially defeated in the Middle Euphrates River Valley. While the area has now been liberated from the Islamic State, securing and stabilizing the region will likely prove much harder. There is a very great risk of a jihadi revival in a region with a geography that is difficult terrain for counterinsurgents. The long period it took the overstretched SDF to liberate the east side of the Euphrates afforded the Islamic State time to create sleeper cells. Additionally, the fact that the west of the river is now under Assad regime control and the possibility that the whole region will fall under regime control now that the United States has announced it is pulling troops out of Syria will likely provide opportunities for both the Islamic State and the al-Qa`ida offshoot Hayat Tahrir al-Sham to tap into local Sunni anger to rebuild their operations in Deir ez-Zor. If they manage to do so, the region could emerge as a jihadi safe haven that threatens Iraq, Syria, the wider region, and global security.

Now that the Islamic State has been territorially defeated in its last significant safe haven in the Middle Euphrates Valley in Deir ez-Zor, attention is turning to securing and stabilizing the area. Drawing on extensive communications with local residents in Deir ez-Zor, U.S. officials involved in coalition efforts, SDF commanders, local citizen journalists, and tribal figures among other sources, this article argues there is a high risk of a significant jihadi revival in the area.

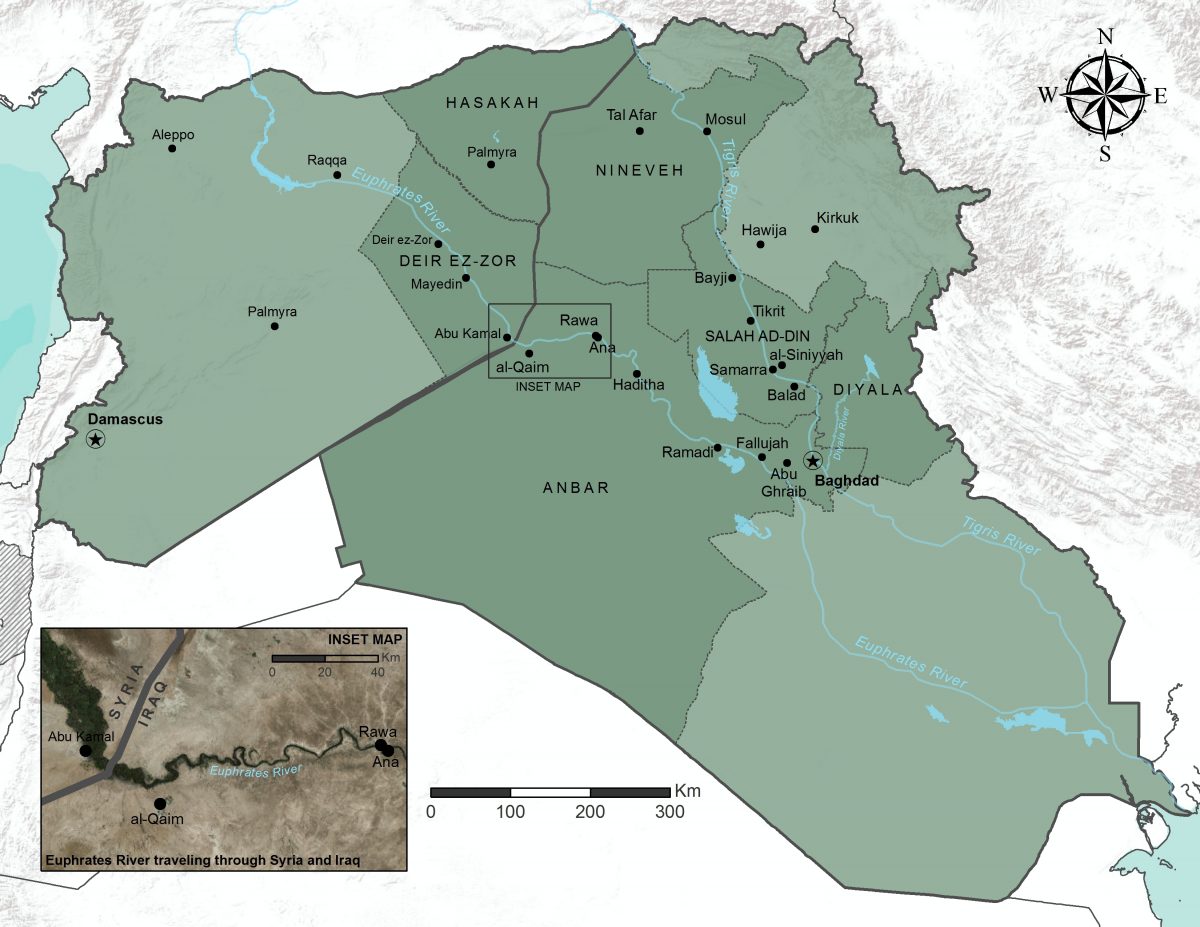

Removing the Islamic State from Deir ez-Zor was always going to be a significant challenge, especially because unlike in Iraq, the United States has had to work exclusively with a non-state actor to liberate, secure, and stabilize territory that had been seized from the Islamic State. By the summer of 2017, that force, the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), had expelled the Islamic State from much of northeastern Syria and reached its second center in Raqqa.1 At that point, the SDF had already become stretched to the limit.a The Kurdish YPG, or the People’s Protection Units, was operating farther away from its strongholds in the north and thus relying heavily on U.S. firepower to drive the group out of the city.2

The situation for the SDF was further complicated as the U.S.-led coalition advanced south to the governorate of Deir ez-Zor, the final major battleground against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, because it is the only province in eastern Syria that has no indigenous Kurdish communities. The SDF’s limited capabilities—in terms of manpower, training and local knowledge—allowed jihadis to survive and melt into the local population.3 It also caused the battle to drag on for twice as long as the fight in Mosul, providing the Islamic State with more time to prepare for a future insurgency and terrorism campaign by establishing sleeper cells.4

The slow campaign against the Islamic State in northeastern Syria by the U.S.-backed coalition also allowed the Assad regime to get a ‘head start’ in the race to ‘liberate’ Deir ez-Zor, with pro-Assad forces back in control of the west side of the Euphrates River by late 2017. As this article will outline, the return of regime control has provided fertile conditions for the Islamic State and the al-Qa`ida-linked Hayat Tahrir al-Sham to tap into local Sunni anger to rebuild their operations in the region.b

Finally, the announced pull-out of U.S. troops from Syria5 will only make it more difficult to secure and stabilize the area because U.S. disengagement risks the entire region falling back under Assad control. It risks creating even more fertile conditions for a jihadi revival.

The Islamic State’s Last Territorial Stand

On September 5, 2017, the Assad regime backed by relentless Russian firepower broke a siege that the Islamic State had imposed around Deir ez-Zor’s provincial capital for nearly three years.6 Forces loyal to the government had maintained control of several neighborhoods inside the city, against all odds. At its zenith in 2014-2015, the Islamic State had been in control of the rest of the province to the south, west, and east of the garrison, in addition to Hasakah and Raqqa to its north. Despite being equipped back then with an army of suicide bombers, the group had failed to drive out the regime forces from this critical part of eastern Syria. This had resulted in a stalemate, the regime unable to break the siege despite repeated attempts.

The siege was broken after Damascus was able to turn its full attention to the province, with intensive air cover from Russia and heavy ground support from Iranian-backed militias.7 The regime and its allies benefited from reduced fighting elsewhere in the country due to de-escalation agreements brokered by Russia, Iran, and Turkey, which enabled it to allocate resources to the battle in Deir ez-Zor Governorate.8 Four days after the Russian-backed forces broke the siege, the U.S.-backed SDF hastily launched a campaign to clear the Islamic State from Deir ez-Zor, even though the battle in Raqqa was still ongoing.9

After the siege was lifted in the town of Deir ez-Zor, the Assad regime’s campaign there was concluded in just two months.10 Given the long, grinding campaign by the SDF on the eastern side of the Euphrates in the region, it is yet to be fully explained why forces loyal to Assad were able to take back control of the western side so quickly, especially since all of the Deir ez-Zor Governorate’s urban centers except one are situated on that side.11

As forces loyal to Assad advanced on the western side, the Islamic State seemingly did little fighting and just melted away.12 By contrast, it has now been fighting against the SDF in the rest of Deir ez-Zor for 17 months, a period nearly twice as long as its battle to keep control of Mosul in Iraq and more than four times longer than the fight to hang onto Raqqa.

The U.S-backed SDF launched its operation in Deir ez-Zor on September 9, 2017, advancing from southern Hasakah near the Syrian-Iraqi borders along a dead tributary of the Euphrates known as the Khabour River.13 The forces headed west toward the Euphrates River and then south into the small town of Hajin and the border town of Abu Kamal, two miles from the border with Iraq.c

The SDF’s operation initially made quick gains, despite its rushed start before the end of the Raqqa campaign.14 Around mid-November 2017, the SDF liberated all the areas situated along the Khabour tributary and started to move south along the Euphrates River. By then, the first in a series of military pauses had slowed progress.15 Even so, by late 2017, the Islamic State appeared to be crumbling in the face of the U.S.-backed forces and had lost control of the west side of the river to the Assad regime.

As the Islamic State withdrew from the western side of the river, the group concentrated its war effort on the SDF side.16 Its numbers there were swelled not only by this but also Islamic State fighters who had moved to the eastern side of the Middle Euphrates River Valley from other areas the Islamic State had previously controlled in Iraq and northern Syria.17 With most of the villages east of the river emptied of its original residents, the areas the SDF were trying to liberate had become a sanctuary for Islamic State militants and their families.18 As the SDF advanced slowly south in the period up to late 2017 and in the period that followed, Islamic State fighters moved their family southward from one village to another.19

In early 2018, the SDF resumed fighting and took control of the so-called Shaytat towns—three villages named after the Shaytat tribe and the victims four years previously of the single worst massacre carried out by the Islamic State in Syria.20

As it pushed further southward, the SDF, which had already been stretched thin during the battle of Raqqa, relied heavily on U.S. airstrikes.21 The airstrikes intensified in Hajin and even more so in the villages to its south. Locals newly recruited by the SDF in Deir ez-Zor were poorly trained, and the Islamic State killed numerous fighters in its frequent raids on SDF positions, whether in the desert during poor weather or inside towns at night.d

The final stage of the operation to liberate the so-called Hajin pocket (the area stretching southeast from Hajin to the border town of Abu Kamal) began on September 11, 2018. The town of Hajin itself was finally announced as liberated in mid-December 2018.22 Kurdish commanders had expected the operation in the Hajin pocket to end the previous month, but the fighting in the town and in the villages to the south dragged on longer.23

South of Hajin, airstrikes by the U.S.-led coalition blunted the Islamic State’s ability to fight an intensive final battle against the Kurdish-led force. In the villages that remained under Islamic State control, there were by late 2018 thousands of Islamic State fighters along with their families. Speaking to the SDF after being captured, an Islamic State fighter from Canada explained that the group became almost paralyzed as the airstrikes intensified and targeted “strategic places” outside the frontlines in Sousa and Baghouz, two major villages south of Hajin and closer to the Iraqi border.24 He said that the Islamic State, which according to him then still had fighters numbered “in the thousands,” had stored large amounts of food and prepared to defend that last pocket of land. However, he said, the increase in airstrikes had led the militants to move along tunnels and trenches, and not fight in the open. When this article went to press in mid-February 2019, the Islamic State presence on the eastern side of the Euphrates River had shrunk to one neighborhood in the village of Baghouz near the river.25 In the early part of 2019, a significant number of fighters surrendered to Kurdish forces with others trying to flee the area to reach Turkey through human smugglers.26 It is possible a significant number managed to slip into areas controlled by the regime.

Difficult Terrain for Counterinsurgency

The stakes for securing and stabilizing Deir ez-Zor are particularly high. This is because the governorate’s geography creates difficult terrain for counterinsurgents. In this regard, Deir ez-Zor has three distinct topologies. The first is the city of Deir ez-Zor and adjacent towns, extending south to the Deir ez-Zor airport. Beyond that part, the rest of the governorate is tougher terrain. Even when the Assad regime was still strong in 2012, it steadily gave up its bases in the rest of the governorate because it could not sustain a presence in the hostile rural environment. If jihadis regroup, a similar pattern is likely.

The town of Abu Kamal and its environs southeast of Deir ez-Zor form their own region that is largely separate geographically from the rest of the governorate. Rather than include it in its Wilayat al-Kheir (the Deir ez-Zor Province), the Islamic State linked it to the Iraqi border town of al-Qa’im to form its Wilayat al-Furat (the Euphrates Province) because the two towns are closer to each other. The counterinsurgency challenge in Deir ez-Zor is further complicated by the fact that it is surrounded by desert and includes a long stretch of border with Iraq, meaning it will require a large fighting force to secure and hold it, which the regime does not currently have.e

Another factor that might complicate the situation for the Islamic State’s enemies is that in the town of Abu Kamal specifically, the river passes through the Syria-Iraqi border. At that location, three items favorable to a potential future jihadi insurgent campaign converge: the river, the Syrian and Anbar deserts, and the borders. Ideally, this area should be now be controlled by a force or a group of forces that work closely with each other, a senior U.S. official told the author.27 Instead, the Euphrates River now serves as a demarcation line separating Russian-backed pro regime and U.S.-backed SDF, with the SDF operating east of the river and pro-Assad forces mostly west of the river.28 The terrain for counterinsurgency is made more difficult still because the extensive tracts of desert that lie between the river and the Syria-Iraq border.

In this context, the Islamic State and other jihadis will likely find gaps that could be difficult to suppress, especially given the United States is set to draw down forces. Such gaps include the ability to move through the river, the deserts, and the borders, especially since these areas are usually only lightly governed and contain porous borders. Additionally, the growing presence of Shi`a militias along the Iraqi borders, instead of the U.S.-allied Iraqi Army, could further complicate the United States’ future ability to conduct and coordinate operations in those areas from Iraq.29 f The Islamic State has a history of successfully using rivers and areas adjacent to them as hideouts and for mobility, even when the United States was heavily present inside Iraq after its troop surge in 2007. The Middle Euphrates River Valley includes lush river reeds and palm orchards that make it easier for militants to hide and survive.

The Residual Islamic State Presence

While the geographic terrain of Deir ez-Zor presents challenges to counterinsurgents, the demographic terrain provides opportunities to jihadis. On both sides of the river, there are already indicators of a vacuum in Deir ez-Zor. Villages and towns on the regime’s side are still largely empty or ruined, with a few exceptions. Locals’ reluctance to return to their towns reflects widespread fears of regime retribution and rejection of its legitimacy.30 Mass exodus from the areas west of the river started before the regime’s campaign and continued afterward, especially with the heavy Russian bombing of civilians in Mayedin in October 2017.31

Sizable numbers of the population relocated from the west side of the Euphrates to SDF-held areas.32 This trend speaks to the deep popular suspicion toward the regime and the relative popularity of the SDF, which many view as less corrupt and brutal.33 However, incidents on the ground and information provided to the author by sources in the region suggest that the Islamic State still has loyalists among the population living under the SDF and even operating within the SDF.34 Tribal figures complain, for example, that the SDF has set free local members of the Islamic State, and many of those were incorporated by the SDF into low-key security activities, such as manning checkpoints and patrolling in newly-liberated areas.35 The reason cited by the tribal figures for this policy is the SDF’s attempt to appease local clans, especially those with whom they had pre-existing contacts. Those former Islamic State members incorporated into security structures reportedly vouch for locals who ostensibly joined the Islamic State for non-ideological reasons.36

There are clearly merits in trying to rehabilitate such individuals. For example, a notable case in Hasakah involved a former senior member of the Islamic State who had served as part of its tribal outreach.37 He was jailed for two months but then released after Kurdish commanders learned that he had originally been compelled to join the group after the militants threatened to punish his son. Locals also testified that he enabled the release of civilians jailed or accused by the Islamic State. Notwithstanding this example, multiple sources from Deir ez-Zor, in speaking with the author in late 2018/early 2019, have questioned the loyalty of former associates of the group.

All of this raises concern over the Islamic State’s residual support and clandestine membership in Deir ez-Zor. As noted above, the limitations on the capabilities of the SDF as a counterinsurgent force and the slow pace of their push southward along the Euphrates into Deir ez-Zor afforded the Islamic State opportunities to preserve fighters and establish sleeper cells on the east side of the river. The Islamic State’s swift withdrawal from the western side of the Euphrates, the widespread urban destruction, and the reluctance of people to return to their homes on the western bank of the river provide favorable conditions for a future resurgence of the group. On the east side of the river, the coalition-backed campaign also created hardships for the local population, with a senior French military officer publicly arguing that the approach taken by the coalition in the Hajin pocket had “prolonged the conflict” and “massively destroyed the infrastructure … leaving behind the seeds of an imminent resurgence of a new adversary.”38 There are already recurrent night-time attacks by Islamic State militants in SDF-held areas.39

The Consequences of U.S. Disengagement

Although there have been mixed messages about the timetable for U.S. withdrawal, it seems unlikely the region will be secured and stabilized before the last contingents of U.S. troops are expected to leave.g As reported by several U.S. media outlets, the Pentagon assessed in late January 2019 that the Islamic State could take back territory in Syria within months if the United States did not maintain military pressure on the group.40

One possible scenario for when U.S. troops draw down is that the SDF remains in control of the parts of Deir ez-Zor east of the river, but without close guidance, oversight, and support from the U.S.-led coalition. This would likely further weaken its ability to secure the area. In mid-February 2019, General Joseph Votel, commander of U.S. Central Command, told CNN that the SDF “still require our enablement and our assistance.”41 There is a risk that the Islamic State will regenerate in an accelerating way as the military pressure against it subsides.

In recent years, as outlined by Michael Knights in this publication, the Islamic State was able to regenerate in multiple areas in Iraq after they were liberated from the group, including Salah ad-Din where the group gradually returned to conduct ambushes, targeted killings, and small raids.42 It is noteworthy that the Islamic State was able to regenerate in parts of Iraq despite the fact that forces battling the Islamic State in Iraq are more numerous and battle-hardened than in eastern Syria.

Another possible scenario is the regime takes over the rest of Deir ez-Zor once U.S. forces depart because the Kurds come to an arrangement with Damascus43 or prove unwilling to sustain the burden of operations on the east side of the Euphrates. A regime takeover of the eastern side of the Euphrates could create favorable conditions for jihadi militants for several reasons. One, it could drive more people from their homes, as already happened in the regime’s side, creating a greater population of internally displaced people from which jihadi groups can recruit. Two, it could push locals to more closely align with the Islamic State because of deep-seated animosity among the Sunni population in the area toward the regime. Finally, a transition from SDF to Assad regime forces could open new space for the militants to operate.44 A similar situation took place in the Iraqi province of Kirkuk when pro-government forces expelled the Kurdish peshmerga and took over in October 2017.45 The Islamic State subsequently regrouped in Kirkuk and since then has waged a steady insurgency against the Iraqi forces there.46

An Opportunity for al-Qa`ida

If regime forces return to eastern Deir ez-Zor, this could provide an opportunity for al-Qa`ida’s offshoot, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), to revive its presence in an area that once served as its most significant pocket inside Syria,47 before the Islamic State expelled it from the region in the summer of 2014.48

HTS up until 2016 went by the name Jabhat al-Nusra. Unlike in Raqqa and Hasakeh, most Jabhat al-Nusra fighters in Deir ez-Zor remained cohesive and did not ‘defect’ to the Islamic State.49 Hundreds of HTS’ members come from the governorate, and the group has a broader network that it could utilize to return as a committed force against the regime.50 Given the group’s rebranding, the perception that it remains a viable force against the regime, and its less aggressive approach, even non-jihadis might welcome such a formidable former ally in the fight against the regime in their areas.

As noted above, the return of the whole of Deir ez-Zor to Assad regime control would make it especially vulnerable to a jihadi resurgence. HTS has extensive networks closer to the regime areas within Deir ez-Zor, while the Islamic State has more experience operating in the deserts around Deir ez-Zor, which connect the governorate with central and southern Syria. The Islamic State also likely has a significant number of sleeper cells within Assad regime-controlled areas in central and western Syria, which could be awoken as the militants regroup in other areas of Deir ez-Zor. According to the account of a senior member of the Islamic State to Iraqi media, the group maintained cadres operating discreetly in regime-held areas.51

The High Stakes in Deir ez-Zor

For now, the Islamic State as a territorial entity in Iraq and Syria is over, and the military momentum against it continues to hold. The organization has lost the last pocket of land it held in the Euphrates River Valley, where many of its most hardcore fighters who descended from other battlefields in Iraq and northern Syria were ostensibly preparing for a sustained final battle.52 h

But while Deir ez-Zor has now been liberated from the Islamic State, the region is far from secured and stabilized. The U.S. drawdown has created the possibility of a worse-case scenario in which the Assad regime takes back nominal control of the whole of Deir ez-Zor, risking a powerful jihadi revival in the border region between Syria and Iraq.

The author previously warned in this publication in late 2017 that there was a high risk that the Syria-Iraq border area that stretches into Deir ez-Zor along the Euphrates could become a long-term jihadi safe haven that threatens not only Iraq and Syria, but also the wider region and global security:

“This contiguous terrain in Iraq and Syria is akin to the region along the Afghan-Pakistani border that previous U.S. administrations dubbed ‘AfPak’ and treated as a single theater requiring an integrated approach. The ‘Syraq’ space, which stretches from the areas near the Euphrates and Tigris river valleys in northern and western Iraq to Raqqa and Palmyra, looks set to be to the Islamic State what AfPak has been to the al-Qa`ida and Taliban factions, providing a hospitable environment and strategic sanctuaries.”53

Despite the fact that the Islamic State has lost control of its territory in the border region, the very real risk of a jihadi revival means there continues to be a significant risk that the region emerges as a long term jihadi safe haven. In such circumstances, Deir ez-Zor would likely become key to the Islamic State’s mobility and connectivity between central and southern Syria, the Syrian-Iraqi border region, and through the Syrian and Anbar deserts, as well as providing the Islamic State with a sanctuary to sustain its campaign of international terror attacks. CTC

Hassan Hassan is an analyst and writer who focuses on militant Islam, nonviolent extremism, and geopolitics in the Middle East. He is a contributing writer at The Atlantic and a senior fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy in Washington, D.C. He is the co-author of ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror, a New York Times bestseller chosen as one of The Times of London’s Best Books of 2015 and The Wall Street Journal’s top 10 books on terrorism. Follow @hxhassan

Substantive Notes

[a] A senior U.S. official involved in the fight against the Islamic State told the author that the Kurdish leaders of the SDF were not keen to fight in Deir ez-Zor, especially after the grinding fight in Raqqa. Such reluctance could be explained by the lack of interest in a province regarded as outside the Kurdish ancestral homelands, often referred to as Rojava, but the Kurdish-led force ultimately agreed to lead the fight in Deir ez-Zor. Author interview, U.S. official, March 2018.

[b] Deir ez-Zor was a key stronghold for the HTS predecessor group Jabhat al-Nusra from 2012 to 2014, when the Islamic State defeated it and drove it out of the province. Aron Lund, “Syria’s al-Qaeda Wing Searches for a Strategy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 18, 2014.

[c] With the exception of Hajin, this part of Deir ez-Zor is largely rural and its population is concentrated in the fertile lands along the river. The SDF area of operations also includes most of the governorate’s oilfields and gas plants.

[d] Kurdish fighters, who tend to be better trained, generally were not stationed inside populated areas. Author interviews, SDF fighters and local contacts, over the course of the campaign in Deir ez-Zor in 2017-2019.

[e] While the regime has been able to secure itself, the conflict in Syria is not over yet. One-third of the country remains outside of the government’s control, either under Turkish influence in the northwest or the SDF in the east. The regime forces also have a superficial hold on much of the country, outside the major urban centers. There is a vast arc of vulnerable areas that Damascus probably cannot sufficiently secure—a rough terrain of deserts and river valleys extending from the Israeli borders in the southeast to Iraq in the east and then to Turkey in the northwest.

[f] After announcing the U.S. troop withdrawal from Syria in December 2018, President Trump suggested U.S. troops in Iraq could be used for operations that proved necessary in Syria. Paul Sonne and Tamer El-Ghobashy, “U.S. forces will stay in Iraq and could reenter Syria from there, Trump says,” Washington Post, December 26, 2018.

[g] In December 2018, President Trump announced U.S. troops would leave within 30 days, before tweeting the withdrawal would take place “slowly.” The New York Times subsequently reported that the draw-down period had been extended to several months. In mid-February 2019, CENTCOM Commander General Votel stated U.S. troops would begin pulling out in the coming weeks but did not give a date for their complete withdrawal. Eric Schmitt and Maggie Haberman, “Trump to Allow Months for Troop Withdrawal in Syria, Officials Say,” New York Times, December 31, 2018; Gordon Lubold, “U.S. Mideast Commander Sees Syria Withdrawal ‘Right on Track,’” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2019.

[h] In one of its publications last year, the Islamic State complained that many of its members had become dormant and unwilling to conduct insurgency tactics in their areas. “If more precautions restrict the individual’s mobility and ability to achieve what’s required of him, these precautions turn into a mechanism that obstructs jihadi work instead of facilitating it … which could affect its success, continuity and ability to grow,” the publication stated. Hassan Hassan, “We have not yet seen the full impact of ISIS sleeper cells coming back to life,” National, April 18, 2018.

Citations

[1] “Syria war: US-backed forces ‘surround IS in Raqqa,’” BBC, June 29, 2017.

[3] This is observation is based on the author’s conversations with local sources with first-hand knowledge of SDF operations in 2018 and early 2019.

[4] Sarah El Deeb, “Cornered in Syria, IS lays groundwork for a new insurgency,” Associated Press, February 6, 2019; author interviews, local sources in Deir ez-Zor, 2018 to early 2019; “As IS defeat in Deir e-Zor nears, concern turns to tribal tensions, sleeper cells,” Syria Direct, February 14, 2019.

[7] Ibid.

[9] “U.S.-backed forces to attack Syria’s Deir al-Zor soon: SDF official,” Reuters, August 25, 2017.

[11] Tom Perry and Sarah Dadouch, “U.S.-backed Syrian fighters say they will not let government forces cross Euphrates,” Reuters, September 15, 2017.

[13] “US-backed SDF launches offensive in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor,” Rudaw, September 9, 2017.

[14] “US-backed Syrian Fighters Make Sweeping Advance In Eastern Syria,” Globe Post, September 10, 2017.

[15] “SDF halts offensive against ISIS after the Turkish attacks,” Rudaw, October 31, 2018.

[17] Author interviews, local contacts in Deir ez-Zor, 2017-2018.

[18] Vera Mironova and Karam Alhamad, “ISIS’ New Frontier,” Foreign Affairs, February 1, 2017.

[19] Author interview, local sources in Deir ez-Zor, 2017-2019.

[22] Martin Chulov, “Isis withdraws from last urban stronghold in Syria,” Guardian, December 14, 2018.

[23] Author interview, SDF commander, December 2018.

[24] “New in-depth interview with captured Canadian ISIS fighter,” Almasdar News, January 18, 2019.

[25] “As IS defeat in Deir e-Zor nears.”

[26] Ibid.

[27] Author interview, U.S. government official, January 2018.

[28] “US strikes in Deir ez-Zor to defend SDF headquarters,” Rudaw, August 2, 2018.

[30] Author interviews, locals from various villages in Deir ez-Zor, January 2018.

[31] Author interview, local contacts in Deir ez-Zor, September 2017.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Author interview, local contacts in Deir ez-Zor, 2017-2019.

[34] Author interviews, journalists and local contacts in Deir ez-Zor, 2018.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Footage filmed by a journalist from Raqqa, shared with the author in June 2017, documented the story of the Islamic State’s former senior official.

[39] Author interviews, journalists and local contacts, 2018.

[46] Ibid.

[48] “Islamic State expels rivals from Syria’s Deir al-Zor – activists,” Reuters, July 14, 2014.

[49] Author interviews, members and associates of HTS, 2014 to 2019.

[50] Ibid.

[51] “As IS defeat in Deir e-Zor nears;” “ISIS Official Known for Caging Foes Is Captured by Iraq,” New York Times, November 30, 2018; “Nas publishes dangerous confessions by one of the most important ISIS commanders captured by the Iraqi intelligence,” Nas News [Iraqi news outlet], November 29, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ePvMrTcYQM&t=12s.

[52] “New in-depth interview with captured Canadian ISIS fighter;” Bassem Mroue, “ISIS Reverting to Insurgency Tactics After Losing Caliphate,” NBC News, October 12, 2018; Liz Sly, “In Syria, U.S.-backed forces launch battle for last Islamic State foothold,” Washington Post, February 9, 2019.

Skip to content

Skip to content