Abstract: Somalia became one of the main jihadi destinations for German foreign terrorist fighters in the years 2010-2012. A significant portion of these Somali and non-Somali foreign fighters belonged to a group of al-Shabaab sympathizers that had formed in Bonn before their departure to Somalia. Several of these foreign fighters had kinship ties. For the non-Somali Germans who joined al-Shabaab, Somalia was a secondary option after failed attempts to reach other jihadi arenas. For the majority of those who joined the group from Germany, al-Shabaab turned out to be an unwelcoming host organization, with the majority of German recruits opting to escape Somalia. Recent trials in Germany of these returnees shed new light on their initial mobilization and their experiences in Somalia.

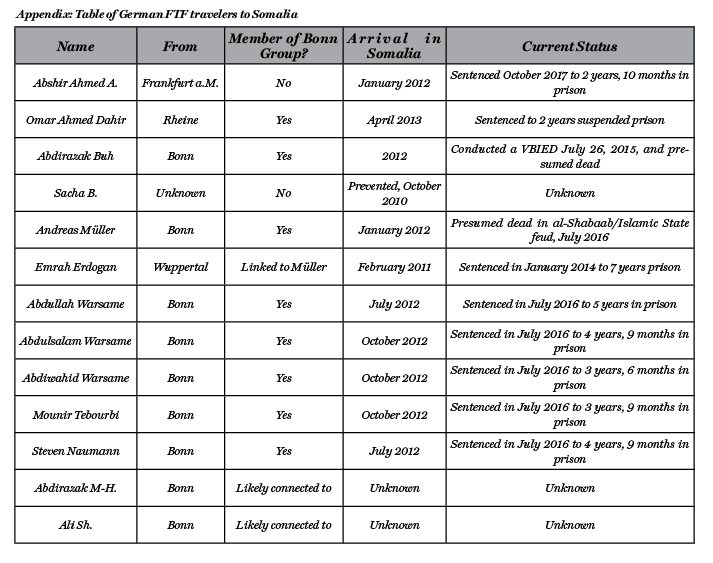

In 2016-2017, Germany prosecuted two separate cases of German foreign terrorist fighter (FTF) returnees from Somalia, shedding new light on the Somali and non-Somali foreign fighters from Germany who traveled in 2010-2012 to join the terrorist group al-Shabaab. Altogether, at least 15 individuals from Germany successfully joined the jihad in the Horn of Africa. Available open sources have enabled the full or partial identification of 12 of these German foreign fighters. While al-Shabaab foreign fighters from the United States, United Kingdom, and Scandinavia have been studied, this study, which draws on public German court documents and media reports, serves as a first attempt to analyze the experience of German al-Shabaab foreign fighters.

In October 2017, a Somali-born German national, identified by German press as 29-year-old Abshir Ahmad A., was found guilty by the Frankfurt Oberlandesgericht (State-level Higher Regional Court) of membership in a foreign terrorist group.1 In contrast to the majority of the German foreign fighters who traveled to Somalia, of which the majority belonged to a radical network from Bonn, Abshir Ahmad A. came from Frankfurt, where he became radicalized in 2011.2 Verbal support for al-Shabaab was followed by travel, and on January 22, 2012, Abshir Ahmad A. flew via London and Dubai to Somalia. After arriving in al-Shabaab-held territory, he underwent a security screening, followed by four months of ideological and paramilitary training in an al-Shabaab training camp, which included instruction in the use of small arms and basic infantry tactics.3 After training, he was given guard duties, but due to medical problems, he was discharged from active al-Shabaab duty. The verdict in his later trial stated that he had remained active in the terrorist group until around late 2013/early 2014.4

Abshir Ahmad A. remained in Somalia for several years before he attempted to return to Germany. On July 4, 2016, he was arrested at Frankfurt airport. During his interrogation, he provided the security authorities with a cover story for his stay in Somalia. Unbeknownst to Abshir A., however, German authorities had already arrested German al-Shabaab fighter Mounir Tebourbi, who revealed that he had met Abshir Ahmad A. in Somalia on several occasions. On October 27, 2017, Abshir Ahmad A. was convicted of terrorism offenses and sentenced to two years and 10 months in prison.5

The “Deutsche Schabab” Group

In October 2016, in what was Germany’s first counterterrorism prosecution against returning al-Shabaab foreign fighters, the state prosecution office accused five 23- to 31-year-old men of active “participation in a terrorist organization” and “preparation of acts endangering the security of the State.” A sixth suspect was accused of attempted participation in these crimes. All men had departed from the city of Bonn to join al-Shabaab in Somalia.6

A significant number of the approximately 15 known al-Shabaab fighters from Germany come from the Bonn region (German state of North Rhine-Westphalia). Trial proceedings during November 2016 provide insights into the mobilization of these German jihad-volunteers and their experiences in the ranks of al-Shabaab in Somalia.

The grouping had long been on the radar of German authorities. In 2010, a document of the North Rhine-Westphalian Landeskriminalamt (LKA) drawn up for the state prosecutor’s office, and which was leaked to the press, warned that the state had become a “jihadist bastion”7 and stated that a secretive group of approximately 15 members had been detected in the Bonn region. The group was said to consist of Somalis but also native-born German converts to Islam, calling themselves “Deutsche Schabab,” the German al-Shabaab. The LKA suspected that members had very likely provided the terrorist group with financial and material support.8 The report stated that the imam of a mosque in Bonn-Beuel, “Sheikh Hussein,” was the leader and religious authority of the group. It added that members of the group met regularly with him to discuss their participation in the global jihad.9 It is noteworthy that by 2007, the same radical-Islamist milieu in North Rhine-Westphalia had produced at least 13 jihadi travelers to the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region.10 When it came to the pro-Shabaab mobilization, a central figure seems to have been the aforementioned Sheikh Hussein, a then 39-year-old radical preacher of Somali origin, identified in the German media as Hussein Kassim M.11

Two additional key figures in the grouping supportive of al-Shabaab in Bonn were named in the leaked LKA document: Omar Ahmed Dahir, a physics student of Somali origin from the town of Rheine, and his friend Abdirazak Buh, a Somali-Libyan dual national. In 2008, both men had attempted to join the jihad in the Horn of Africa, but were prevented at the last moment by German police who arrested them as they were about to take off from Köln-Bonn airport. Both were soon released from custody, however, and the state prosecutor’s office dropped the investigation against the men due to the lack of evidence.12 The men had allegedly planned to fly via Amsterdam to Entebbe, Uganda, and continue from there to Somalia.13

Another German, though not connected to the Bonn group and who failed in his attempt to reach Somalia, was a radicalized former Bundeswehr non-commissioned officer who has been identified as Sascha B. The 23-year-old convert had been radicalized during his service in the German military.14 On September 22, 2010, Sascha B. boarded a plane from Frankfurt to Kenya, but his attempt to travel to Somalia ended when Kenyan authorities arrested him near Mombasa and deported him back to Germany.15

From Pakistan to Somalia: 2011-2012

These failed attempts to travel to join al-Shabaab were not enough to deter additional attempts by Islamist extremists from Germany to join the jihad in Somalia. The year 2011 became a watershed one in outbound jihadi travel patterns from Germany as Somalia replaced Pakistan as the top jihadi-travel destination for a period of time before the large subsequent travel flows to Syria. In 2011, German authorities counted six attempts to travel to Pakistan while the number of attempts to Somalia was double this number. In total, there were 12 attempts by Germany radicals to travel to Somalia that year, with four successfully reaching their destination.16

Those who successfully made the trip in 2011 included Abdirazak Buh, who managed to reach Somalia on his second attempt after traveling via Egypt.17 Buh was soon followed by Andreas Müller, a German convert to Islam who traveled with his wife and child to Somalia via Kenya in September 2011. Buh and Müller joined an al-Shabaab faction led by Sheikh Ali Mohammed Rage18 in January 2012.19

Müller had grown up in a middle class home in Bonn.20 He converted to Islam in 1998 and married an Eritrean Muslim woman.21 His greatest desire was to migrate with his wife to an Islamic country where both could live as “proper” Muslims. This desire took the couple first to Bosnia and later to the UAE, but applications by Müller and his wife for permanent residence permits were declined in both countries.22 In 2006, the couple became parents. This did not put an end to Müller’s desire to emigrate, however. In 2009, Müller, his wife, and his daughter were arrested for illegal entry into Pakistan and kept in jail for six months on suspicion that the family had tried to join jihadis in Waziristan.23

Interestingly, the first known jihadi from Germany to arrive in Somalia had also spent time in Pakistan. In early 2010, Emrah Erdogan, a then 23-year-old German-Turkish national, traveled from Wuppertal (in North Rhine-Westphalia) to Waziristan, where he first joined the “Deutsche Taliban Mujahiden” (DTM) and then allegedly the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU). Erdogan was part of a wave of German jihadis to the region who joined Central Asian jihadi groups—like IMU or IJU or their own group, called the “die Deutsche Taliban”—the “German Taliban-movement.”

According to court documents, in November 2010 Erdogan phoned the German federal police to threaten that al-Qa`ida was planning attacks in Germany.24 It is unclear why Erdogan made these threatening calls.

Soon afterward, he decided to leave Pakistan and change battlefields.25 One possible explanation for Erdogan’s departure was that he left his hosts in “bad standing,” fearing reprisals resulting from his jihadi hosts for his unauthorized calls to German security authorities.

In February 2011, Erdogan traveled via Iran and Kenya to Somalia, allegedly with a letter of recommendation from al-Qa`ida for his new host organization, al-Shabaab, on a USB memory stick.26 Using the kunya Abu Khattab, Erdogan served as a propagandist and a contact point for individuals wanting to join al-Shabaab in Somalia.27 It is unclear, if Buh, Müller, or any other of the Deutsche Schabab members were in contact with Erdogan before their travel. When Buh and Andreas Müller joined al-Shabaab in early 2012, there was already at least one German foreign fighter in Somalia, which possibly had the effect of pulling newly arriving foreign fighters from Germany into a clique.

Buh had been identified by the LKA in 2010 as a leading member of the Deutsche Schabab. In the spring of 2012, two additional travelers from Bonn arrived in Somalia with their spouses and children: Abdullah Warsame, a 28-year-old Somali with German nationality,28 and his brother-in-law Steven Naumann, a 26-year-old German convert. The route they took—first flying to Mombasa in Kenya and then with the help of smugglers transiting by road into Somalia—was followed by the rest of the group a few months later.29

By the time Warsame and Naumann traveled to join al-Shabaab, Erdogan—who had been in Somalia for about a year and had been jailed by al-Shabaab for some time30—had come to the conclusion the country was not at all a welcoming arena for jihadi volunteers and was allegedly trying to discourage Western jihadi volunteers from traveling to Somalia.31 By 2011, al-Shabaab was past its peak strength of 2009-2010 when it had made territorial gains and witnessed fast organizational growth, following the withdrawal of Ethiopian forces from Somalia.32

Al-Shabaab’s emir, Ahmed Godane had become suspicious of the loyalty of some of al-Shabaab’s foreign fighters.33 In an attempt to purge the organization from any opposition to his rule, al-Amniyat, the feared internal security organization of the group, started to isolate, arrest, and assassinate individuals suspected of divided loyalties.34 Prominent members with personal ties to al-Qa`ida leaders like Ibrahim al-Afghani, a founding member of the organization, were killed.35 Prominent foreign fighters started to die under mysterious circumstances. Erdogan was one of those caught up in Godane’s dragnet. Al-Shabaab suspected Erdogan of being a spy and jailed him.36 Eventually—it is not clear why—the cloud of suspicion lifted.

He then allegedly went ‘operational.’ Erdogan was involved in a May 28, 2012, bomb attack against a small shopping complex on Moi Avenue in Nairobi, which injured 30,37 Kenyan authorities subsequently claimed. According to their account, Erdogan had slipped from Somalia across the Kenyan border early that May and was a member of the attack cell. Erdogan was arrested two weeks later on June 10, 2012, at Daressalam airport in neighboring Tanzania. A week later, he was handed over to German authorities, who put him on trial. Although involvement in the bomb attack in Nairobi was not proven in court, in January 2014 Erdogan was given a seven-year jail sentence after being convicted for terrorism offenses.38 The U.N. Security Council’s al-Qaida Sanctions Committee subsequently listed the now jailed Erdogan as an al-Qa`ida associate on November 30, 2015.39

Yet more Deutsche Schabab members arrived in Somalia in late 2012 and early 2013. Two of Warsame’s brothers, the 23 year old Abdulsalam and Abdiwahid Warsame, followed in Abdullah’s and Steven Naumann’s footsteps to Somalia together with Mounir Tebourbi,40 a 30-year-old German-Tunisian who also went by the name Aby Yahya.41 All three had their families with them.

What motivated them? Based on their statements during the court proceedings, for the Warsame family, the motivation to travel to Somalia seems to have been a combination of factors. The oldest brother Abdullah wanted to “live in an Islamic society” after his Umrah pilgrimage to Mecca and had contemplated Egypt as an alternative to Somalia.42 They instead chose to travel to Somalia as their mother wanted to return there to reconnect with family members in the Kismayo region. While none of the three brothers had performed well in school in Germany or secured a decent income, the worst off seems to have been the youngest brother Abdiwahid.43 He had dropped out of school altogether and developed a drug addiction.44 After their older brother had suggested, in a family meeting, migration to Somalia, the younger brothers had gone along with his decision.45

During their childhood, the Warsame brothers had been introduced to the idea of jihad and martyrdom by the sermons of a Tunisian imam, Emir Abu Obeida, in a local mosque in Bonn.46 Abdulsalam testified that he had been prepared to “do his basic military service” in al-Shabaab.47 All men had watched al-Shabaab propaganda videos before departure.48 Another member of the Deutsche Schabab grouping in Bonn was the German-Tunisian Mounir Tebourbi. According to German media reports, Tebourbi had dreamed of living in a “Sharia State,” as well as martyrdom and paradise before traveling to Somalia.49 He had come in contact with jihadi circles around the year 2005 when he was studying machine engineering at university at Gummesbach near Bonn.50 Mounir had first come across unidentified members of the group that metamorphosed into the Deutsche Schabab while playing soccer.51

Like the non-Somalis Erdogan and Müller, Tebourbi seems to have viewed Somalia as a secondary option. In 2009, he had attempted to travel to Pakistan to join the German foreign fighters in Waziristan and to fight against ISAF in Afghanistan, but he was forced to return to Germany after making it to the Iranian-Pakistani border.52

It remains unclear why the German authorities let some of the Deutsche Schabab members leave Germany. At least Buh, Abdullah Warsame, and Mounir Tebourbi were known to the security authorities for their activity in the jihadi milieu of Bonn before their travel.53 The explanation might be simple: all the Deutsche Schabab members traveled to Somalia via countries like Egypt and Kenya that could have been seen as plausible tourist destinations, denying the authorities the possibility to prevent their departure from Germany.

Training and Trying Times in Somalia

In 2012, the number of German al-Shabaab fighters reached its peak. Besides Erdogan, Buh, Müller, Abshir Ahmad A., the Warsame brothers, Naumann, and Tebourbi, two additional members of Deutsche Schabab found their way to Somalia around the year 2012: Abdirizak M. H. and Ali Sh.54

The trial in Germany of the Warsame brothers, Naumann, and Tebourbi gives a relatively detailed description of how al-Shabaab received it foreign volunteers. After arrival, the five men from Bonn were subjected to an al-Shabaab ‘clearinghouse process’ in which they were vetted for their trustworthiness. Personal mobile phones and electronic devices were confiscated by al-Shabaab, and the men had to stay isolated in a house, together with other al-Shabaab volunteers from “Kenya, America and Asia.”55 The German volunteers did not stay together all the time. Indeed, it looks as if al-Shabaab may have intentionally split the group up. Three had to stay in a type of quarantine longer than the others, but finally, all five were admitted to al-Shabaab training after giving an oath of allegiance to the emir of al-Shabaab.56 In 2013, the men received combat training for several months in al-Shabaab training camps, including training in using AK-assault rifles and RPGs as well as guerrilla tactics. After this, the men were posted to man al-Shabaab’s defensive positions against government forces.57 In the spring of 2013, a sixth man from Bonn arrived in Mogadishu with the desire to join al-Shabaab. Omar Ahmed Dahir, a German-Somali, had already once tried to travel to Somalia in 2008 together with Abdirazak Buh.58 When Buh had made a second and successful attempt to travel to Somalia, in 2012, Dahir had remained in Bonn.

On December 10, 2012, an unexploded bomb was found at the Bonn railway station. A large counterterrorism investigation ensued. Dahir and another individual were arrested the next day after a 14-year-old witness claimed to have seen the men leaving behind the luggage containing the IED. A day later, Dahir was released and publicly cleared of suspicion.59 The investigation led to another member of the Bonn jihadi milieu, a German convert to Islam, Marco G., who was charged together with three co-conspirators for the failed attack at the Bonn railway station and convicted in April 2017 to life imprisonment.60

The episode could have contributed to Dahir’s decision to undertake another attempt to leave Germany as four months later—in April 2013—Dahir did indeed reach Somalia. Once in Mogadishu, Dahir met with Abdiwahid Warsame and Mounir Tebourbi who just had graduated from their training camp.61

On the advice of both men, Dahir presented himself to the al-Shabaab members responsible for the vetting process at the ‘clearinghouse.’ However, they suspected Omar Dahir to be a spy and jailed him for five months.62 During his incarceration, Dahir was reportedly tortured.63 Luckily for him and untypically, al-Shabaab decided instead of the usual punishment for spying (beheading) to expel him.64 Kenyan authorities arrested Dahir in July 2014 and deported him to Germany.65

After a year, disillusionment settled in among the remaining quintet. The constant squabbles between al-Shabaab commanders, frequent U.S. drone strikes, and especially the “rigid treatment” of foreigners in al-Shabaab demoralized the German group.66 Contributing to the sense of disquiet, in September 2013 al-Shabaab had assassinated Omar Hammami (alias Abu Mansoor al-Amriki), a prominent public member of al-Shabaab’s foreign fighter community.

In August 2014, the remaining members of the Deutsche Schabab group fled with their families to Kenya. In Nairobi, three of the men gave themselves up to German law enforcement authorities and were flown to Germany. Abdullah (28) and Abdulsalam Warsame (24) and Steven Naumann (26) were arrested upon their arrival at Frankfurt airport. Their wives and children and Abdullah’s and Abdulsalam’s mother also returned to Germany.

While Somalia had been a disappointment to the brothers Abdullah and Abdusalam Warsame and their bother-in-law Naumann, not all were willing to turn their back on the jihadi cause. At some point—it is not clear from where—Tebourbi allegedly made contact with a Syria-based American rapper cum terrorist “Duale”67 (possibly Douglas McAuthur McCain, alias “Duale Khalid,” the first American to die (August 23, 2014) while fighting for the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria68) for advice on how to join the Islamic State. Abdiwahid, the youngest of the Warsame siblings, was willing to continue with Tebourbi to Syria.69 Interestingly, both men were pictured in an al-Shabaab propaganda video entitled “Mujahedeen Moments 4” and produced by the group’s media wing Al-Kataayb Media.70 Their plan to leave al-Shabaab and change battlefields and join the Islamic State in Syria/Iraq, by traveling first to Turkey, however, ended in Nairobi as al-Shabaab had confiscated their passports.71 Kenyan security authorities arrested the pair. Both claimed to have been in Somalia on a “humanitarian mission” but to no avail as they were handed over to German security authorities. During their interrogations, both confessed and gave evidence against the other.72

In July 2016, the Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht)73 of Frankfurt sentenced the six to prison terms of up to five years. The longest sentence was handed to the oldest of the brothers, Abdullah Warsame, while the others were sentenced from a two-year suspended jail sentence to four years and nine months in prison.74

While disillusionment and discontentment had caused the six-man travel group from Bonn to return to Germany in 2014, not all members of the Deutsche-Schabab took this trajectory. Abdirazak Buh, 29, who had been one of the first to arrive in Somalia, became the first German suicide bomber to blow himself up in Somalia. On July 26, 2015, Buh carried out a VBIED-suicide bombing against the Jazeera Palace Hotel in Mogadishu, killing at least 15 people. Al-Shabaab took responsibility for the attack.75

Meanwhile, Andreas Martin Müller (alias Abu Nusaybah) had become somewhat of a bête noire to regional security services. Kenya attributed several terrorist attacks in the country to Müller, and in June 2015, the government announced a $100,000 reward for his capture.76 At some point after joining the jihadi cause in Somalia, Müller seems to have been active in a Shabaab sub-group Jaysh Ayman (“Army of the Faithful”) together with a handful of other foreign fighters.77

While it is unclear from what point Müller became involved in the unit, one of the attacks Müller was accused to have taken part in was on a Kenyan military base in Buare, Lamu County, on June 14, 2015. The attack made headlines after it was discovered that one of the al-Shabaab terrorists killed was 25-year-old British convert Thomas Evans.78 Earlier the same year, Evans and Müller had been involved in a deadly al-Shabaab attack against a Kenyan university in Garissa County that left more than 140 people dead, Kenyan authorities alleged.79 In pictures retrieved from a camera found on Evans’ body after the Lamu County attack, Evans and Müller could be seen embracing each other before the attack.80

In April 2016, a split took place in al-Shabaab when a group calling itself “Jabha East Africa” announced its loyalty to the Islamic State and gave its bay`a (oath of allegiance) to Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, recognizing him as the “rightful Khalifa (leader) of all Muslims.”81 This decision by the group, who claimed to represent “all East Africans in al-Shabaab,” amounted to a declaration of war against its previous host organization:

“Sadly, Al-Shabaab has forgotten the resolved needed to work for the establishment of the rule of Allah. Many Kenyans, Tanzanians and Ugandan Mujahideen have been accused without evidence of working against Islam and the Mujahideen. Many have been detained for accepting the declaration of the Khalifah … We in JAHBA EAST AFRICA are telling the Mujahideen in East Africa that Al-Shabaab has now become a psychological and physical prison.”82

A few months later, in July 2016, “Jabha East Africa,” announced on Twitter that Müller had died: “da bros [sic] who beg Al Shabaab to come to Islamic State. May Allah accept him.”83 Combined with this announcement, Jabha East Africa also distributed an old propaganda video featuring Müller.84 The tweet indicated that before his death, under unknown circumstances, Müller had defected from al-Shabaab to Jabha East Africa. His motive for changing sides could have ranged from ideological (as the announcement seems to have indicated) to personal survival, as the declaration and several other subsequent Jabha East Africa announcements repeatedly made reference to the persecution of non-Somali foreign fighters in al-Shabaab.85

Conclusion

With the announcement of Müller’s (unconfirmed) death, the longest-serving foreign fighter from Germany in Somalia had been taken off the battlefield. The mobilization of foreign fighters to al-Shabaab from Germany underscores the importance of friendship and kinship ties in the radicalization process and the FTF phenomenon as has been pointed out by several scholars.86 From the 12 identified German foreign fighters to join al-Shabaab, all but two came from Bonn and had been members of the Deutsche Schabab group and the wider jihadi milieu of Bonn. Interestingly the Warsame-brothers87 and their family friend Mounir Tebourbi88 had been living in a neighborhood of Bonn-Tannenbusch, a locality of the city that has seen significant foreign fighter outflows. By 2012, these included several jihadi volunteers who traveled to the Afghan-Pakistan border region and then later a large proportion of the 50 German FTFs who traveled from Bonn to join the Islamic State.89 This geographical concentration of the German jihadi volunteers is, as such, not unique. Minneapolis also saw waves of departures and in Sweden, Stockholm’s Rinkeby, Göteborg, and Malmö became hotspots for al-Shabaab recruitment.90 However, a slight difference to the U.S. and Swedish experiences can be detected in the makeup of the travelers: almost all of the foreign fighters from the United States and Sweden (and Scandinavia) were ethnic Somalis. In the German case, a significant portion were non-Somalis. This can be explained by the multiethnic makeup of the salafi-jihadi milieu in Bonn.

In addition to the preexisting friendships, another factor binding the group together was kinship. Out of the 12 identified travelers, three were brothers. If the kinship bond is extended to include in-laws, then four out of 12 identified travelers belonged to a single family (the Warsame brothers and their in-law Steven Naumann).

How much was the migration of the Deutsche Schabab to Somalia the result of top-down recruitment? German authorities never pressed charges against the alleged radical preacher of the Deutsche Schabab group, Hussein Kassim M. This suggests authorities were unable to find evidence connecting his alleged radicalization activity and the decision of the members of the group to leave for Somalia.

At least six, and possibly eight, of the al-Shabaab fighters from Germany were of Somali heritage. For the non-Somalis (Erdogan, Müller, and Tebourbi), Somalia was clearly a secondary option, as all three had attempted to reach another jihadi arena before arriving in Somalia. For Erdogan, Somalia became a refuge from U.S. drone strikes (and possibly his jihadi comrades’ fury). The fact that several travelers reached Somalia via countries like Egypt and Kenya, countries that could be seen as plausible tourist destinations, may explain why German authorities were unable to prevent their departures to fight jihad in Somalia.

The friendship and kinship factor in mobilization also helps to explain why German foreign fighters—in comparison to the mobilization and travel to join al-Shabaab from Minnesota or some parts of Northern Europe—were late arrivals in Somalia. By 2012, the situation of al-Shabaab had become difficult. It had lost control of Mogadishu in 2011 to AMISOM and was retreating from the high point of its expansion.

Collectively for the German jihadi volunteers, Somalia and al-Shabaab seems to have been a bitter disappointment. At least two of the 12 were suspected of being spies and were jailed and physically abused/tortured by the same group they had wanted to join. The growing tensions inside al-Shabaab, and additional tensions within the group created by the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria and the announcement of its global caliphate, complicated their situation further. Abdiwahid Warsame and Tebourbi looked into possibilities to leave Somalia to join the Islamic State in Syria. Müller seems to have been caught up in the infighting and chose to split from al-Shabaab.

By the end of 2016, out of the 12 German al-Shabaab foreign fighters, seven had returned to Germany and had to stand trial for terrorism offenses. With Buh likely dead and Müller purportedly dead, only two partially identified German foreign fighters—Abdirazak M-H. and Ali Sh.—remain unaccounted for. CTC

Dr. Christian Jokinen received his doctorate from the Department for Contemporary History at the University of Turku in Finland. He specializes in political violence and terrorism.

Substantive Notes

[a] In 2015, German authorities assessed that 30 individuals from Germany had at least attempted to travel to Somalia to join al-Shabaab. “15 deutsche Dschihadisten kämpfen in Somalia,“ Die Zeit, May 16, 2015.

[b] German media and authorities customarily identify suspected or convicted individuals with only the first letter of their last name. However, some local and international media outlets have not held to this norm, enabling the full identification of some of the German FTFs.

[c] State Criminal Police Office

[d] In 2015, the Somali community in Germany was assessed to number around 5,000 members. Larger Somali communities in Europe could be found in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the Nordic countries of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

[e] It is unclear if the group indeed called themselves ‘Deutsche Schabab,’ as media reporting has suggested, or if this was a name given to the group by German security authorities. The German internal security service Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz echoed this assessment when it stated in its 2013 annual report that the threat of al-Shabaab in Germany was stemming from “individual supporters and sympathizers.” “Bundesministerium des Innern (Hrsg.), Verfassungsschutzbericht 2013,” p. 253.

[f] Die Zeit claimed that the Al-Muhsinin mosque served as a meeting point for radicalized individuals, of which some had travelled to Waziristan and joined al-Qa`ida. Christian Denso, “Bonn und sein Islamistisches Milieu,” Die Zeit, April 30, 2009. In 2010, the local newspaper in Bonn, General-Anzeiger, alleged that the mosque had hosted in August 2009 a seminar with preachers that German security authorities had categorized as ”extremists.” Frank Vallender, ”Experten warnen vor Extremisten, die in Beueler Moschee vortragen,” General-Anzeiger, December 4, 2010.

[g] It is noteworthy that while fundraising activity on behalf of al-Shabaab was suspected to take place in the Cologne/Bonn region, in Munich and Augsburg, a significant number of the identified foreign fighters to travel to Somalia came from Bonn. “Die Shabaab-Milizen,” Akademie des Verfassungsschutzes, May 2015.

[h] According to German press reports, Buh was born in Libya in 1985. “Islamist aus Bonn sprengte sich in die Luft,” Bild, July 28, 2015.

[i] Here, it is worth noting that travel to Somalia did not mean automatic acceptance into al-Shabaab. Indeed, in several cases the process to join the group took several months.

[j] His alias was Salahuddin al-Kurdi or Abu Khattab.

[k] Another possible factor for his departure was the death of his brother Bünyamin in a U.S. drone strike a month before on October 4, 2010. Dirk Baehr, “Die Somalischen Shabaab-milizen und ihre Jihadistischen netzwerke im Westen,” KAS Auslandsinformationen 8/2011.

[l] According to German media reporting, Müller was in contact with Erdogan, but it is unclear when these contacts took place, either before or after Müller’s arrival in Somalia. Thomas Scheen, “Deutscher Islamist von Kenianischen Behörden gesucht,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 18, 2015.

[m] In June 2011, Comoros-born al-Qa`ida operative and leading member of al-Shabaab Mohammed Harun Fazul took a wrong turn with his car in Mogadishu and was killed at a government checkpoint. It is widely suspected, however, that Fazul’s death was orchestrated by al-Shabaab elements. Jeremy Scahill, “The purge – How Somalia’s Al Shabaab Turned Against Its Own Foreign Fighters,” The Intercept, May 19, 2015. One of the first to be killed by al-Shabaab FTFs from Europe was Bilal al-Berjawi, a British-Lebanese sub-commander within the group who was killed by a drone strike in January 22, 2012. A month later, his companion Muhammad Sakr was also killed under similar circumstances. Raffaello Pantucci and A.R. Sayyid, “Foreign Fighters in Somalia and al-Shabaab’s Internal Purge,” Terrorism Monitor 11:22 (2013).

[n] Jaysh Ayman has presented itself as a local movement defending Swahili Muslims and fighting against the Kenyan government. The group has been found responsible for several attacks and cross-border raids in which fighters, among other things, travel across the land border between Somalia and Kenya to target individuals and carry out attacks in Kenya. Andrew McGregor, “How Kenya’s Failure to Contain an Islamist Insurgency is Threatening Regional Prosperity,” Terrorism Monitor 15:20 (2017); Thomas Joscelyn, “American charged with supporting Shabaab, serving in ‘specialized fighting force,’” FDD’s Long War Journal, January 11, 2016.

[o] According to German media reports, over 45 percent of the 15,000 inhabitants of Bonn-Tannenbusch have a migrant background. Around 40 percent of the inhabitants of Bonn-Tannenbusch live on social welfare payments. The neighborhood has been seen as one of Germany’s most active salafi hotspots. Frank Vallender, “Problemviertel Tannenbusch – Nährboden für Salafismus?” General-Anzeiger, November 17, 2014; “Bonn-Tannenbusch – Das Deutsche Molenbeek?” WDR, December 3, 2015.

[p] German authorities, however, prevented Hussein Kassim M. from becoming a German citizen. Hussein Kassim M. challenged this legally, but lost. By 2014, German media reported that Hussein Kassim M. was no longer serving as an imam. Frank Vallender, “Hassprediger darf kein Deutscher sein,” General-Anzeiger, May 28, 2014.

[q] Traveling to join al-Shabaab from Minnesota started in 2007 and took place over the next two years in several waves. “Timeline: Minnesota pipeline to al-Shabab,” Minnesota Public Radio, last updated September 25, 2013.

[r] Leading FTFs from the United Kingdom Bilal Berjawi and Mohammed Sakr reached Somalia in 2009. The same year, 10 FTFs from Sweden were reported to have joined a growing contingent of Swedish Somalis fighting in the ranks of al-Shabaab. One of these, Fuad Shongole became a significant leader in al-Shabaab. Raffaello Pantucci, “Bilal al-Berjawi and the Shifting Fortunes of Foreign Fighters in Somalia,” CTC Sentinel 6:9 (2013); Eva Blässar, “Terroristgrupp rekryterar medlemmar I Sverige,” YLE, January 24, 2010; “Sweden rattled by Somali militants in its midst,” Associated Press, January 24, 2010. For a profile of al-Shabaab leadership figure Fuad Qalaf, see Nathaniel Horadam and Jared Sorhaindo, “Profile: Fuad Mohamed Qalaf (Shongole),” Critical Threats, November 14, 2011.

[s] These were Erdogan in 2012; the Warsame-brothers, Naumann, and Tebourbi in 2014; and Abshir Ahmad A. in 2016.

Citations

[1] “Verurteilung wegen Mitgliedschaft in der terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Al Shabab,’” OLG Frankfurt a.M., October 27, 2017; “Fast drei Jahre Haft für Ex-Shabaab-Kämpfer,“ Deutsche Welle, October 27, 2017.

[2] “Verurteilung wegen Mitgliedschaft in der terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Al Shabab.’”

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Axel Spilcker, “Sie sammeln sich in Bonn,” Focus, November 22, 2010.

[8] “Bonner Islamisten schon 2010 im Visier – ohne Folgen,” Focus, December 22, 2012.

[9] Spilcker, “Sie sammeln sich in Bonn;” “Islamist aus Bonn sprengte sich in die Luft,” Bild, July 28, 2015.

[10] Spilcker, “Sie sammeln sich in Bonn.”

[11] “Islamist aus Bonn sprengte sich in die Luft.”

[12] Axel Spilcker, “Bonn – das Mekka der Radikalen,” Focus, January 1, 2013; Florian Flade, “Bonner Islamist soll Anschlag in Somalia verübt haben,” Die Welt, July 28, 2015.

[13] Dirk Baehr, “Die Somalischen Shabaab-milizen und ihre Jihadistischen netzwerke im Westen,” KAS Auslandsinformationen 8/ 2011; Flade, “Bonner Islamist soll Anschlag in Somalia verübt haben;” Florian Flade, “Bonner Islamist steckt hinter Anschlag in Somalia,” Die Welt, July 29, 2015; Florian Flade, “Deutsche Dschihadisten in Somalia,” Jih@d blog, August 6, 2015.

[14] “Soldat Sascha B. – Dschihadist beim Bund,” Wirtschafts Woche, April 12, 2016.

[15] Dirk Baehr, “Die Somalischen Shabaab-milizen und ihre Jihadistischen netzwerke im Westen,” KAS Auslandsinformationen 8/ 2011; Florian Flade, “Somalia ist die neue Keimzelle des Terrors,” Die Welt, October 5, 2010; Florian Flade, “German Military Fires Muslim Soldier,” Jih@d blog, October 5, 2011; Florian Flade, “German Convert wanted to join Al-Shabaab,” Jih@d blog, October 5, 2010.

[17] Flade, “Bonner Islamist soll Anschlag in Somalia verübt haben.”

[18] For a profile of al-Shabaab leadership figure Sheikh Ali Mohammed Rage, see Nathaniel Horadam and Jared Sorhaindo, “Profile: Ali Mohamed Rage (Ali Dhere),” Critical Threats, November 14, 2011.

[19] Dirk Baehr, “Salafismus in Deutschland,” 2014, p. 236.

[20] Yassin Musharbash, “Wo bist du, Andy?” Die Zeit, May 24, 2012.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.; Yassin Musharbash and Holger Stark, “Islamists in Pakistan Recruit Entire Families from Europe,” Spiegel, September 21, 2009.

[24] “Staatsschutzsenat des Oberlandesgerichts Frankfurt am Main eröffnet Hauptverfahren gegen Emrah E. wegen mitgliedschaftlicher Beteiligung an ‚.Al-Quaida‘ und ‘Al-Shabab,’” OLG Frankfurt, March 22, 2013.

[25] Florian Flade, “Ey, was ist mit Allah?” Jih@d blog, June 18, 2012.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Staatsschutzsenat des Oberlandesgerichts Frankfurt am Main verurteilt Emrah E. zu Gesamtfreiheitsstrafe von sieben Jahren.”

[28] All the members of the group were fully identified in Axel Spilcker, “Bonner Terror-Touristen,” Focus, September 15, 2014.

[29] Johanna Boos, “Die Reise nach Somalia, Teil 2,” TAZ blogs, November 17, 2015.

[30] “Staatsschutzsenat des Oberlandesgerichts Frankfurt am Main verurteilt Emrah E. zu Gesamtfreiheitsstrafe von sieben Jahren.”

[31] Flade, “Ey, was ist mit Allah?”

[32] Stig Jarle Hansen, Al-Shabaab in Somalia. The History and Ideology of a Militant Islamist Group, 2005-2012 (London: Hurst & Company, 2013), pp. 73-103.

[33] Raffaello Pantucci and A.R. Sayyid, “Foreign Fighters in Somalia and al-Shabaab’s Internal Purge,” Terrorism Monitor 11:22 (2013); Hassan M. Abukar, “Somalia: The Godane Coup and the Unraveling of Al-Shabaab,” African Arguments, July 2, 2013.

[35] Ibid.; Bill Roggio, “Shabaab confirms 2 top leaders were killed in infighting,” FDD’s Long War Journal, June 30, 2013. Another leading al-Shabaab member killed in infighting was Moalim Burhan.

[36] “Staatsschutzsenat des Oberlandesgerichts Frankfurt am Main verurteilt Emrah E. zu Gesamtfreiheitsstrafe von sieben Jahren.”

[37] “Tanzania arrests man over recent Nairobi attack,” BBC, June 13, 2012.

[38] “Staatsschutzsenat des Oberlandesgerichts Frankfurt am Main verurteilt Emrah E. zu Gesamtfreiheitsstrafe von sieben Jahren.”

[39] “QDi.362, Emrah Erdogan,” Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee, November 30, 2015.

[40] Identified in Spilcker,“Bonner Terror-Touristen.”

[42] Nicole Opitz, “Vom Kiffer zum Dschihadisten,” TAZ blogs, November 14, 2015.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Boos.

[46] Nicole Opitz, “Al Shabaab Prozess: Der jüngste Bruder sagt aus,” TAZ blogs, October 9, 2015; Opitz, “Vom Kiffer zum Dschihadisten;” Boos.

[47] Boos.

[48] Opitz, “Vom Kiffer zum Dschihadisten.”

[49] Jörg Diehl and Fidelius Schmid, “Familientrip in den Dschihad,” Spiegel, June 12, 2015; Frank Lehmkuhl and Axel Spilcker, “Von Bonn in den Dschihad,” Focus, May 16, 2015.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Spilcker, “Bonner Terror-Touristen.”

[53] Vallender and Franz.

[54] Partly identified by Flade in “Deutsche Dschihadisten in Somalia.”

[55] Opitz, “Al Shabaab Prozess;” Boos.

[56] Opitz, “Vom Kiffer zum Dschihadisten;” Nicole Opitz, “Die Reise nach Somalia Teil 1,” TAZ blogs, November 14, 2015; “Freiheitsstrafen für sechs Angeklagte wegen Beteiligung an der terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Al-Shabab.’”

[57] Opitz, “Al Shabaab Prozess;” Lehmkuhl and Spilcker.

[59] “Terror-Angst in Bonn: Zweiter Islamist nach Bombenalarm festgenommen,” Focus, December 11, 2012; “Polizei lässt Festgenommene wieder frei,” Der Spiegel, December 12, 2012.

[60] “Lebenslänglich für Hauptangeklagten in Düsseldorfer Islamisten prozess,” Die Welt, April 3, 2017.

[61] “Anklage gegen mutmaßliche Mitglieder der ausländischen terroristischen Vereinigung Al-Shabab,” Generalbundesanwalt, March 20, 2015; Frank Vallender, “Bonner sollen als Dschihadisten an der Waffe gedient haben,” General-Anzeiger, March 23, 2015.

[62] Nicole Opitz, “Von jungen Männern, die auszogen, um … ja, was eigentlich?” TAZ blogs, July 13, 2016.

[64] Anette Hauschield, “Unzufrieden und enttäuscht zurück nach Hause,” TAZ blogs, November 10, 2015.

[66] Ibid.; Spilcker, “Bonner Terror-Touristen.”

[69] Opitz, “Vom Kiffer zum Dschihadisten;” Hauschield.

[70] Opitz, “Von jungen Männern, die auszogen, um … ja, was eigentlich?”

[71] “Monitoring Report Nr. 1 Strafverfahren gegen Abdullah W. u.a. 1. Verhandlungstag,” International Research and Documentation Centre War Crimes Trials, Trial-Monitoring Programme, June 12, 2015.

[72] Lehmkuhl and Spilcker; “Von Frankfurt ins Somalische Terrorcamp,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 11, 2015; Vallender; “Freiheitsstrafen für sechs Angeklagte wegen Beteiligung an der terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Al-Shabab.’”

[73] “Freiheitsstrafen für sechs Angeklagte wegen Beteiligung an der terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Al-Shabab;’” “15 deutsche Dschihadisten kämpfen in Somalia,” Die Zeit, May 16, 2015.

[74] “Freiheitsstrafen für sechs Angeklagte wegen Beteiligung an der terroristischen Vereinigung ‘Al-Shabab;’” “Haftstrafen wegen Beteiligung an Terrormiliz,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, July 7, 2016.

[75] Florian Flade, “Bonner Islamist soll Anschlag in Somalia verübt haben;” Flade, “Bonner Islamist steckt hinter Anschlag in Somalia.”

[76] “Kenya issues reward for German al-Shabab fighter,” BBC, June 18, 2015.

[77] Sunguta West, “Jaysh al-Ayman: A ‘local’ threat in Kenya,” Terrorism Monitor 16:8 (2018).

[78] “Briton Thomas Evans among al-Shabab fighters killed in Kenya,” BBC, June 15, 2015; Thomas Scheen, “Deutscher Islamist in Kenia gesucht,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 18, 2015.

[80] “Briton Thomas Evans among Al-Shabab Fighters Killed in Kenya;” “UK Jihadist Thomas Evans was Al-Shabab Cameraman,” BBC, June 20, 2015; David Williams, “Final Moments of the ‘white beast’: Heavily-bearded British Muslim convert is seen hugging and praying with Al-Shabaab fighters before going into battle where he was shot dead by Kenyan troops,” Daily Mail, June 24, 2015.

[82] “Our Bay’ah to The Shaykh Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi Al-Hussayni Al-Qurayshi,” Jabha East Africa, available at Jihadology.

[83] Weiss.

[84] “New video message from Jabha East Africa: ‘The Martyr Muller,’” Jihadology, July 1, 2016.

[85] For example, Jabha East Africa’s statement “From the heart of Jihad” on July, 4, 2016, in which it claimed that “today, Al-Shabaab ONLY jails and kills innocent Mujahideen from East Africa.” “From the Heart of Jihad,” Jabha East Africa, available at Jihadology.

[86] For example, see Mohammed M. Hafez, “The Ties that Bind: How Terrorists Exploit Family Bonds,” CTC Sentinel 9:2 (2016) or Marc Sageman, Understanding Terrorist Networks (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), pp. 107-113.

[87] Rüdiger Franz, “Nach Abschiedsvideo Richtung Somalia,” General-Anzeiger, June 12, 2015.

[88] Dhiel and Schmid.

[89] Joachim Wagner, “Das Sind die Deutschen Treibhäuser des Terrors,” Die Welt, February 11, 2016.

[90] Jay Newton-Small, “Minneapolis Somalis Struggle with al-Shabaab link,” Time, September 26, 2013; Christina Capecchi and Mitch Smith, “Minneapolis fighting Terror recruitment,” New York Times, September 5, 2015; Lorrie Flores, “Motivating factors in Al-Shabaab recruitment in Minneapolis, Minnesota,” Walden University, 2016; Hansen, pp. 96-97, 99, 137; Michael Tarnby and Lars Hallundbaek, “Al Shabaab. The Internationalization of Militant Islamism in Somalia and the implications for Radicalization Processes in Europe,” Danish Ministry of Justice, February 26, 2010; Kajsa Norell and Karin Wirenhed, “ Personer i Rinkeby hotas av al-Shabab,” Sverige Radio, November 12, 2009.

Skip to content

Skip to content