Abstract: Data collected from news reports about al-Qa`ida suspects arrested in the Pakistani mega-city of Karachi since 9/11 suggest that the group’s presence in the city has been growing in recent years. The data also points to how the character and make-up of al-Qa`ida in the region is also shifting. Both trends speak to the persistence and diverse nature of the al-Qa`ida threat and how the challenges posed by the group in the region extend well beyond Afghanistan and span across more remote locales, as well as major urban areas in Pakistan—even 16 years after 9/11.

“We believe we have constrained al-Qa`ida’s effectiveness and its ability to recruit, train, and deploy operatives from its safe haven in South Asia; however, this does not mean that the threat from core al-Qa`ida in the tribal areas of Pakistan or in eastern Afghanistan has been eliminated.”

—Nicholas Rasmussen, NCTC Director, September 20161

Official U.S. government assessments of al-Qa`ida’s strength in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, and the threat posed by the elements of the group based there, typically paint a picture of an organization that has been degraded but that also continues to pose a lingering, or persistent, lower-level threat.2 The evidence most often used to support this view includes the significant and sustained leadership losses al-Qa`ida has suffered in the region since 9/11; al-Qa`ida core’s lack of success in conducting or inspiring operations in the West; the mostly insignificant attacks it has executed locally; and the group’s lessened ability to centrally coordinate or lead the activity of its regional affiliates.

In many ways, these are hard data points to argue against, especially if one looks at the two primary metrics—the losses inflicted on al-Qa`ida via drone strikes and other operations and the group’s ability to conduct attacks outside the region—that the United States has been using to evaluate the strength of al-Qa`ida based there. These two metrics are critical to any assessment of al-Qa`ida in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as they provide high-level measures of al-Qa`ida’s resilience, operational capacity, and ability to project force.

But just as they are necessary, these metrics are also not entirely sufficient, as they only measure specific dimensions of al-Qa`ida’s strength. Indeed, as any good social scientist knows, one’s assessment of a problem depends a lot on how that problem is defined and the metrics one uses to evaluate it. A focus on some metrics, and not others, could potentially skew one’s evaluation and understanding of a problem. For example, these two metrics say very little about al-Qa`ida’s ability to recruit members locally in Pakistan. They also do little to explain the disconnect between al-Qa`ida core’s relative failure to conduct attacks outside the region and the group’s demonstrated ability to execute a fairly consistent campaign of less significant, but still noteworthy, attacks in specific countries in the region. (The latter is a particularly important point given the number of al-Qa`ida members killed by counterterrorism forces in Afghanistan and Pakistan since 9/11.)

This issue is arguably compounded by the geographic apertures through which the al-Qa`ida problem has been viewed and evaluated. Indeed, despite a series of senior al-Qa`ida arrests occurring in other locations in Pakistan, most assessments of al-Qa`ida in that country focus on Pakistan’s tribal areas, a region that sits alongside Afghanistan’s long eastern border (where al-Qa`ida has also historically been a consistent problem). This focus is also warranted, but it also only tells part of the story, as a proper assessment of al-Qa`ida in Pakistan would include an evaluation of many variables across different geographic areas.

By taking a different, geographically more scaled-down view and by focusing on an important metric that often is not used to evaluate al-Qa`ida’s strength in Pakistan, this article seeks to demonstrate how evaluations of al-Qa`ida in that country might be incomplete. To gain purchase into the issue, this article intentionally looks at al-Qa`ida suspects arrested in one major city in Pakistan (Karachi) since 9/11. Given the narrow view taken, this article is not designed to be a full assessment of al-Qa`ida in Pakistan generally, or even in Karachi specifically. It only seeks to demonstrate what arrest action data can tell us about al-Qa`ida’s presence and potential strength in Karachi and how that has changed over the last 16 years. In the process of doing so and in highlighting what can be learned from other, easily collectible data, the author hopes to raise questions about how the United States has approached the issue of counterterrorism metrics and whether current assessments of al-Qa`ida in Pakistan are “right.” Such an approach is prudent, as the danger of potential misdiagnosis of the problem is not without its share of consequences; a poor diagnosis could lead to misguided and ineffective solutions to mitigate the threat—or worse, leave the United States more vulnerable to strategic and operational surprise.

Methodology, Limitations, and Caveats

The data for this report was assembled by culling newspapers for articles containing the search string “Al-Qa`ida AND Karachi AND arrest OR detain” between September 12, 2001, and May 31, 2017.a Data from relevant articles was then coded to create a database of arrest actions that targeted al-Qa`ida operatives in the Pakistani mega-city of Karachi. The variables that were coded fell into four broad categories: temporal (including day, month, and year), geographic (including district- and neighborhood-level arrest data), arrest details (including number of arrest actions, number of individuals arrested, number killed, arresting unit, violent encounter, plot disrupted, plot target, and materiel recovered), and individual and group dynamics (including names of arrested, role/position, nationalities, prior group affiliation, and names of other group(s) present). While as many of these variables were coded as the data would allow, some fields were more heavily populated than others.

There are a number of limitations associated with this dataset. First, the database is not based on internal police or Pakistani court records, but rather media accounts of arrests. Because this author does not know what the entire population of arrest actions looks like, the author does not know how representative the database is in relation to all al-Qa`ida arrests made in Karachi over the time period studied. Press accounts of arrests certainly provide a reflection of what has transpired, but it is not clear how closely press accounts comport with local Pakistani law enforcement or judicial statistics. Even if law enforcement data were available, Pakistan and its local security forces have, at times, had incentives to either inflate or underreport the number of al-Qa`ida arrests in Karachi and across the country generally. For example, in the immediate months and years after 9/11, Pakistan arguably had an incentive to publicize the arrests of al-Qa`ida members so that it could demonstrate its commitment to the United States and its war on terror. A case can also be made that Pakistani security forces could have also had incentives to underreport arrests, to downplay the local al-Qa`ida threat. An additional factor that needs to be considered is that press reports about al-Qa`ida arrests can contain inaccurate and/or biased information.

Second, even though care was given to only code those incidents the research team identified as being arrests of al-Qa`ida operatives (and not those individuals that were more loosely “linked” to the group), the events were generally coded as they were reported. Given the lack of public data about most al-Qa`ida arrests, especially the arrest of less well-known operatives, and terrorism trials in Pakistan, the research team was not able to follow up on each case to identify how it was resolved (i.e., whether the suspect was convicted/sentenced or acquitted/released). Thus, the data reviewed below only presents the view from initial arrest of al-Qa`ida suspects in Karachi as revealed in public reporting and not the more final view of those who have been legally convicted for their membership in, or direct association with, the group. For these various reasons, the data and findings found in this article should be considered impressionistic.

Finally, there are a number of analytical issues that are also worth keeping in mind. Arrest data, while useful, is only one measure (albeit an important one) of a terrorist organization’s physical presence in a particular location. For example, one unknown is how many al-Qa`ida members were present in Karachi but managed to evade arrest. Another analytic consideration is that, given the specific geographic focus of this article, the view provided by it is inherently localized. Drone strike and other arrest data show how al-Qa`ida has operated in other areas across Pakistan, and while that data is important to understanding al-Qa`ida’s broader influence and presence in the country, evaluating that material is beyond the scope of this article.

Why Karachi?

Various factors make Karachi an attractive location for al-Qa`ida to operate in, and as a focus area for this type of study.b Karachi is Pakistan’s financial capital and main commercial hub, which likely makes it logistically and financially attractive to the group. Home to more than 18 million people, Karachi is also the largest city in the country. (Given its population and growth rate, Forbes magazine identified Karachi as the “World’s Fastest Growing Mega-City” in 2013.3) And the size and diversity found in the city likely make it an attractive place to hide and engage in covert activity. Karachi also holds the unfortunate distinction of being Pakistan’s most violent city, and political violence in Karachi can be incredibly complicated, as it can be driven by ethno-political rivalries, sectarian tensions, criminal turf battles, globally oriented agendas, and/or a combination of factors.4 This means that federal, state, and local security forces likely have their hands full as they deal with a multiplicity of pressing problems orchestrated by a range of different types of actors—with al-Qa`ida being only one dimension of a much more complicated, local security picture.

Historically, Karachi has also been an important base of operations for al-Qa`ida. For example, one early counterterrorism break in 1998 pointed to the role Karachi played as a key transit point for al-Qa`ida members during the late 1990s. On August 7, 1998, the same day al-Qa`ida conducted its successful, coordinated attacks against the United States’ embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, Pakistani authorities arrested Mohammed Sadiq Odeh at the Karachi airport, immediately after he arrived on a flight from Nairobi, Kenya.5 Odeh was traveling on a false passport, and during his interrogation, he admitted his role in the Embassy attacks.6 A U.S. court would later sentence him to life in prison for his involvement in the Embassy bombings.7

While the arrest of Odeh was an early warning sign about the potential importance of Karachi to al-Qa`ida, other pre-9/11 data points demonstrate how the city functioned as an al-Qa`ida logistics hub. And one that was intimately tied to the operations that al-Qa`ida conducted in New York and Washington, D.C., in September 2001. For example, in the late 1990s, Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, the courier who nearly a decade later unknowingly lead the United States to Usama bin Ladin’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, operated an al-Qa`ida guest house in the city.8 Some of the 9/11 hijackers stayed at that guest house.9 Prior to 9/11, and for a period after, Karachi also served as a ‘home base’ and planning hub for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), the 9/11 mastermind, and Ramzi bin al-Shibh, the al-Qa`ida operative who coordinated logistics for the operation.10 It was in Karachi where the 9/11 hijackers received specific training and were informed of their plot,11 and where KSM and al-Shibh monitored news of the operation after the attacks took place.12 After fleeing Afghanistan, several of bin Ladin’s wives and children also hid out in the city in guest houses that KSM had arranged for them.13 c

Arrests: A Review of the Data

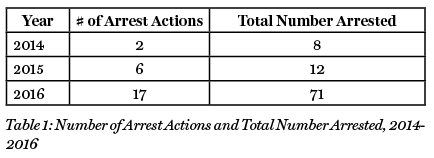

The database contains information on 102 al-Qa`ida arrest actionsd between September 12, 2001, and May 31, 2017, in Karachi, Pakistan. According to the data, 300 al-Qa`ida suspects were arrested in the city over that period of time. Across that more than 15-year timeframe, Pakistani law enforcement and security forces conducted more than five al-Qa`ida arrest actions in Karachi every year on average. This roughly equates to Pakistani security forces engaging in at least one, publicly identifiable, al-Qa`ida arrest action in Karachi every other month on average for a 15-year period.

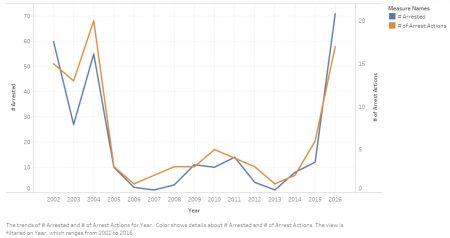

As Figure 1 below illustrates, the frequency of those arrest actions and the number of al-Qa`ida operatives arrested have fluctuated considerably over time. Indeed, Figure 1 shows how the number of incidents and total number of al-Qa`ida suspects arrested were most frequent/highest during the immediate years after 9/11 (2002-2004) and since 2015.e A slight, but noticeable, rise in incidents and arrests from 2009-2011 is also apparent in the data.

Figure 1: Number of Arrest Actions and Number Arrested over Time

The ‘bookending’ of the high points of the data tells a mixed and interesting story. On one hand, the lull in incidents and total arrests from 2005-2014 suggests that during that time period al-Qa`ida was less of a problem, or at least had a less visible presence, in Karachi. Absent other contextual data to explain these trends, a case can be made that the rise in incidents and arrests after 9/11 and the eventual decline in al-Qa`ida arrest activity in Karachi until 2014 is a relatively good-news story. This is because the data shows two important trends: 1) how after an initial high period of post-9/11 arrest actions,f the number of al-Qa`ida arrests declined significantly,g and 2) how the number of al-Qa`ida arrest actions remained relatively low, and did not spike again, for close to a decade. Assuming al-Qa`ida wasn’t just lying low in the city during the 2006-2015 time period, this suggests that the group was less active in Karachi during that time as well.h On the surface, these trends make sense as al-Qa`ida suffered a number of significant and high-level leadership losses in the years after 9/11 and during much of the 2000s al-Qa`ida in the region was primarily preoccupied with its survival.

Yet, on the other hand, the steady uptick in incidents and the number of al-Qa`ida operatives arrested in Karachi between 2013-2016 is a concerning trend in the data. And the dramatic spike in incidents and arrests from 2015-2016 is potentially even more disturbing. Indeed, the highest number of al-Qa`ida members arrested in Karachi per year, across the entire dataset, was recorded close to 15 years after 9/11; four and a half years after bin Ladin was killed in Abbottabad, Pakistan; and a year and a half after al-Qa`ida core formally established its South Asia chapter—al-Qa`ida in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS)—in September 2014. The number of arrest actions and the number of al-Qa`ida suspects arrested in Karachi from 2015 to 2016 nearly tripled and increased almost six-fold, respectively. Put another way, since the creation of AQIS until the end of 2016 (the last year for which we have complete yearly data), there have been 24 arrest actions resulting in the arrest of 88 individuals. Over that time period, security forces have come close to conducting at least one al-Qa`ida arrest action per month on average, with three al-Qa`ida operatives arrested on average per incident.i Counterterrorism officials in Karachi have noticed a similar trend, and they “worry that the organization is regrouping and finding new support here [in Karachi] and in neighboring Afghanistan.”14 In terms of size, “counterterrorism officials in Karachi have a list of several hundred active al-Qaeda members, which makes them assume there are at least a few thousand on the streets.”15 While there has been an uptick in al-Qa`ida-related arrests in the city and the group’s presence in the city appears to have grown, the possibility that thousands of al-Qa`ida members are roaming around Karachi should certainly be taken with a grain of salt.

Three primary explanations exist to explain this trend in the data. First, while al-Qa`ida has long had a presence in Karachi, the uptick in arrests and incidents could be attributed to an expansion, or growth, of al-Qa`ida’s presence in the city in recent years. Indeed, all else being equal, an intensification of al-Qa`ida activity in the city would—at least, in theory—result in an increase in arrests targeting the group. The intensification of al-Qa`ida activity in the area could be tied to renewed or regenerated interest in the group, after it formally established AQIS. A second explanation for this particular trend in the data is that the spike in activity is tied to the performance or posture of the security forces conducting the arrests. Perhaps, security forces—as a result of training or knowledge gained from prior cases—have gained better intelligence or have become more efficient at disrupting local al-Qa`ida cells. The uptick in arrests and incidents could also be explained by security forces having taken a more aggressive posture against al-Qa`ida (which could lead to more arrests) or a more aggressive policing posture generally, as those forces sought to get a better hold of the ‘Karachi al-Qa`ida problem’ after the establishment of AQIS. (One should remember that AQIS conducted its inaugural attack in Karachi,j which could have led to a local crackdown.) Lastly, the increase in incidents and arrests could be tied to media dynamics, with the media potentially reporting on these types of incidents more often in the last several years.

Where: Karachi District and Micro-Level Breakdowns of al-Qa`ida Arrests

District-Level Trends

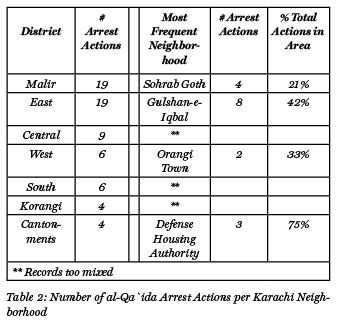

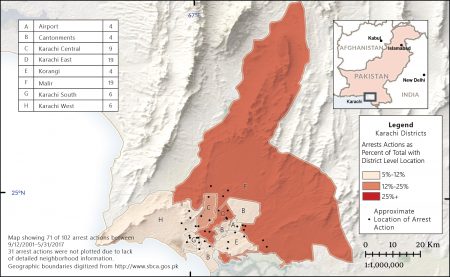

The administrative management of land in Karachi can be a complex affair.k At a general level, Karachi is divided into six administrative districts: Malir, Central, South, West, East, and Korangi—as well as a number of cantonment areas administered by Pakistan’s military.16 Karachi’s international airport, which is managed by Pakistan’s Civil Aviation Authority, for the purposes of this article was designated as a district with the various cantonments also grouped together as one district. The data was coded accordingly. Seventy-one arrest actions, out of the total 102 that feature in the dataset, provide at least a specific Karachi district-level location. Analysis of this level of geographic arrest data is useful as it allows us to: 1) hone in on areas where al-Qa`ida’s presence in the city has been publicly identified, and 2) track how the group’s geographic presence in the city has shifted over time.

The Karachi areas with the highest number of arrest actions were Malir (19 incidents, 26.7% of total) and East (19 incidents, 26.7% of total), followed by Central (9 incidents, 12.7% of total), West (six incidents, 8.5% of total), South (six incidents, 8.5% of total), Korangi and Cantonment areas (four incidents each, each representing 5.6% of total). Four al-Qa`ida suspects were also arrested at Karachi’s main airport. While al-Qa`ida operatives have been arrested in all six districts of Karachi and in different cantonment areas, Malir and East—the two districts with the highest number of al-Qa`ida arrest actions—together account for 53.4% of all incidents over time. If one then includes the number of arrest actions from Central district, the percentage from Karachi’s top three al-Qa`ida arrest districts jumps to 66% of all al-Qa`ida arrest activity in the city.

Heat Density Map of al-Qa`ida Suspect Arrest Actions per District (Rowan Technology)

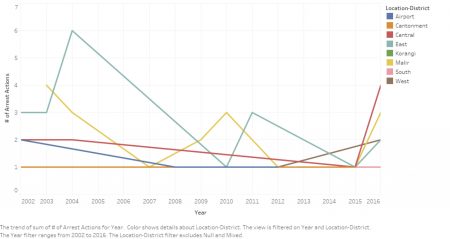

An evaluation of district-level arrest actions over time brings these trends into sharper focus. Indeed, despite there being a number of arrest ebbs and flows related to most districts, Figure 2 shows how Malir and East have remained relatively consistent al-Qa`ida arrest areas across time.

Figure 2 also shows the decline in number of arrests during the 2000s in East and Central districts and how Central has grown since 2015 as a more frequent al-Qa`ida arrest area (nearly similar to the level of arrest activity observed in East during the 2003-2005 timeframe).l

Figure 2: District-Level al-Qa`ida Arrests over Time

Neighborhood Level

Sixty-nine of the 102 arrest actions provide both neighborhood and district-level data, allowing us to identify high-density al-Qa`ida arrest areas and other micro-level geographic arrest trends (as reflected in Table 2 below). Measured as a percentage of all arrest actions across all districts, the neighborhood of Gulshan-e-Iqbal—in Karachi’s East District—accounted for 11.5% of all al-Qa`ida arrest actions in the city for which the author has this level of data. The East District, within which this neighborhood is situated, was also home to the highest total number of al-Qa`ida suspects arrested across time. Another interesting takeaway from the data is that three of the four Cantonments’ arrest actions took place in territory managed by the Defense Housing Authority.

And while Malir District had the same number of total arrest actions that took place in East District, arrests in Malir were less concentrated in one neighborhood than in both West and East Districts. Arrest actions in the districts of Korangi, Central, and South were so dispersed across neighborhoods in those districts that neighborhood level patterns could not even be identified.

This data shows how al-Qa`ida’s presence in Karachi, at least as measured by arrests, has been stronger and more concentrated in some districts—and in some neighborhoods within districts—over time. This data also shows how al-Qa`ida’s presence in other districts has been more geographically dispersed.

Who: Noteworthy Arrests of al-Qa`ida Members in Karachi and Nationality Data

As mentioned earlier, prior to 9/11, Karachi served as a base of operations for al-Qa`ida and individuals like KSM and al-Shibh. The city remained the primary base of operations for KSM for a year and a half after the 9/11 attacks, until his arrest in Rawalpindi in March 2003.17 After beheading Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, who was kidnapped in Karachi in January 2002, KSM even felt comfortable enough with his presence in Karachi that he invited and arranged for an Al Jazeera journalist to interview him and al-Shibh in the city in the spring of 2002 for a special 9/11-focused program.18 Around that same time, in a not well-publicized operation, Pakistani forces in Karachi reportedly arrested a Libyan, who years later would go on to play a leading role in al-Qa`ida.19 In jihadi circles, that Libyan was known as Abu Yahya al-Libi.20

KSM’s bold comfort is what eventually led to his capture, however, as not long after meeting with the Al Jazeera journalist, al-Shibh was arrested in Karachi by U.S. and Pakistani forces.21 From that point onward, the net continued to close around KSM. Then, one month after KSM was captured in Rawalpindi, Walid bin Attash—a key al-Qa`ida operative involved in the USS Cole bombing—was arrested (along with other al-Qa`ida suspects) in the Karachi district of Korangi.22 According to former FBI Special Agent Ali Soufan, who tracked and interrogated al-Qa`ida suspects at that time, “Khallad [Walid bin Attash] spent a lot of time in Karachi planning with KSM.”23 Thus, when looked at in aggregate, Karachi served as the place of arrest for senior to mid-level al-Qa`ida operatives who each individually played key operational roles in the group’s three most noteworthy international attacks: the 1998 East African embassy bombings, the USS Cole attack, and the 9/11 operation.

The number of high-profile or well-known al-Qa`ida members arrested in Karachi dropped off after the first few years following 9/11. As noted above, the number of al-Qa`ida arrest actions in Karachi—as well as the number of al-Qa`ida individuals arrested there—has picked up since al-Qa`ida formally created AQIS in September 2014. Two noteworthy al-Qa`ida members detained in Karachi since then have included Shahid Usman, al-Qa`ida’s Karachi chief who was arrested in December 2014,24 and Abdul Rehman al-Sindhi, a financier arrested in April 2016 who raised and moved funds for al-Qa`ida, Harakat al-Jihad Islami (HuJI), and Jaish-e-Muhammad.25

Nationality Dynamics

The nationality of al-Qa`ida suspects arrested in Karachi also hints at how the make-up of al-Qa`ida in Pakistan has changed since 9/11. The nationality field was not a heavily populated category—only 35% of cases (36 total arrest actions) in the database identified the specific nationality of the individual, or some of the individuals, arrested—and so one can only form a general impression based on the data alone. Yet, what is in the data, as well as what does not appear in the data, raises some interesting questions, and when the nationality field is viewed in relation to other evidence, it lends credence to the view that the more time that elapses after 9/11, the less Arab, and more Pakistani al-Qa`ida in Pakistan becomes.m This trend, which Pakistani journalist Zaffar Abbas identified and wrote about in August 2004, aligns with the broader localizing of al-Qa`ida’s South Asian regional agenda, a long-game of sorts that allows al-Qa`ida to build out its local base and develop capabilities that can be used in the region, and elsewhere.26

According to the data, Pakistani citizens were arrested in at least 10 of the 36 cases for which we have specific nationality information. This means that when a nationality was listed in a press report about an al-Qa`ida arrest in Karachi, a Pakistani was arrested in a little more than one-quarter (27%) of all those cases. When viewed in relation to other data, the period for which the author has nationality data suggests that there is a story behind what is not reported or contained in the data, however. For example, the last case for which there is nationality data is an arrest action that occurred in May 2011 (the same month that Usama bin Ladin was killed). Prior to that date, the nationality reporting was more specific. This could be due to there having been more foreign, non-Pakistani al-Qa`ida suspects arrested in Pakistan immediately after 9/11 and prior to May 2011. The lack of references to nationalities in reporting after that date could also be explained by there not being a need, or desirable reason, to call attention to specific nationalities post-May 2011. This could be due to the bulk of those arrests being arrests of Pakistani citizens. This theory seems plausible because the bulk of localized al-Qa`ida arrest press coverage came from Pakistani newspapers, which might not feel the need to report such data, especially if the arrest did not involve the capture of foreigners.

If one assumes that the absence of reported nationality data means that the individual(s) arrested were locals, then the data would indicate that all reported al-Qa`ida suspects arrested in Karachi since June 2011 have been Pakistani citizens. While it is not possible to validate this theory without official arrest records, a noticeable uptick in Urdu-language statements and videos released by al-Qa`ida since the mid-to late 2000s shows how the recruitment of Pakistanis by the group has been a key priority. The important roles played by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Ilyas Kashmiri, Badr Mansor, and Shahid Usman—all Pakistanis—also speak to the evolving local character of al-Qa`ida, a trend noticed by local security analysts. For example, in a June 2016 interview with The Washington Post, Saifullah Mehsud, the director of the FATA Research Center, noted that al-Qa`ida in Pakistan was “making a comeback of sorts.”27 But, he added, “it’s a different, more localized al-Qaeda.”28 Ominously, Pakistani investigative journalist Syed Saleem Shahzad was murdered under mysterious circumstances in May 2011 for writing about the connections between al-Qa`ida and members of the Pakistani military.29 The creation of AQIS, recent attacks conducted in Pakistan by that affiliate, and the operators used by the group also speak to the further localizing of al-Qa`ida’s presence in Pakistan and across the region.

Conclusion

The trends that are apparent in, and suggested by, the data show how al-Qa`ida has been able to maintain a fairly consistent presence in Karachi since 9/11, a presence that appears to have grown in recent years. An annualized projection of arrest data collected through the end of May 2017 shows a slight drop-off in the number of arrest actions and total number of al-Qa`ida suspects likely to be arrested in 2017.n The total number of arrest actions and al-Qa`ida suspect arrests projected for 2017 is still more than the total figures for 2014 and 2015 combined, however.

The data also speaks to the complex nature of the al-Qa`ida threat and the enduring challenge the group’s presence poses in the region, even 16 years after 9/11. For example, the data highlights the diverse nature of al-Qa`ida’s presence in Pakistan and how the challenges posed by the group in the country have become even more localized and occur across rural and urban, and “settled” and tribal, areas. This article and its findings also take on particular relevance given recent adjustments made to the United States’ Afghanistan policy and on-going debates about the nature of the U.S.-Pakistan partnership—and what that relationship should look like.

The trends discussed here also serve as a useful reminder that just as al-Qa`ida and its approach in Pakistan continue to evolve, the metrics that the United States is using to evaluate the group might also need to change as well. Attacking the United States and the West through operations conducted outside of the South Asia region remains a leading priority for al-Qa`ida.30 As a result, metrics that speak to al-Qa`ida’s ability to execute and inspire international attacks and to act in strategic ways are as needed as ever.

Yet, the data presented in this article and the localized trajectory of AQIS and al-Qa`ida in Pakistan indicate that it also makes sense to develop, collect systematically, and study metrics that provide more useful gauges of how these local elements of al-Qa`ida are faring. The localization of al-Qa`ida in Pakistan is not a phenomenon unique to Pakistan, but it is a trend that has been observed across all of al-Qa`ida’s regional affiliates.31 This makes the need for a localized approach to counterterrorism metrics all the more apparent and timely. Developing a set of local and regional capability metrics for the various al-Qa`ida branches will help to ‘benchmark’ the threat each of these entities pose in their respective locales and to track shifts in geographic presence and capabilities over time.

The continued tracking of al-Qa`ida arrest actions in Karachi, for example, could be used to discern whether the recent spike in al-Qa`ida arrests in that city since the creation of AQIS is a unique and more time-limited occurrence, or whether it represents a broader, more sustained pattern of behavior. Data about the nationality of those arrested and their background and positions (i.e., are those arrested low-skilled foot soldiers, or are they more seasoned leaders or individuals with technical skills?) could also aid local security services and be used to better evaluate the nature, character, and evolution of the al-Qa`ida threat. It is also likely to show how al-Qa`ida in Pakistan today represents a diversified threat that poses different types of challenges across local, regional, and global spectrums. CTC

Don Rassler is Director of Strategic Initiatives at the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. His research is focused on terrorist innovation and the changing dynamics of Afghanistan’s and Pakistan’s militant landscapes. Follow @donrassler

Substantive Notes

[a] The author would like to thank former CTC intern Dakota Foster for the excellent coding support that she provided. This project would not have been possible without her assistance.

[b] It is also worth highlighting that Karachi is not the only city outside of Pakistan’s tribal areas where al-Qa`ida has operated. High-profile al-Qa`ida members have been arrested in Rawalpindi, Faisalabad, Quetta, Lahore, Mardan, and other places since 9/11.

[c] It is also believed that Karachi was going to serve, or did serve, as a transit point for bin Ladin’s son Hamza as he traveled from Iran to reunite with his father. For background, see Ali Soufan, “Hamza bin Ladin: From Steadfast Son to al-Qa`ida’s Leader in Waiting,” CTC Sentinel 10:7 (2017).

[d] By “arrest action,” this author means a successful (resulting in either the arrest or death of at least one individual) arrest operation that law enforcement or security forces conducted. It is not a measure of how many individuals were arrested during that particular operation. The “total number of arrested” field provides details on that particular statistic.

[e] Figure 1 includes data up until the end of 2016.

[f] The highest number of arrest actions took place in 2004.

[g] According to the dataset, only one al-Qa`ida suspect was arrested in Karachi in 2006.

[h] A drop off in public reporting could also explain the noticeable decline in the number of incidents and arrests over that time period.

[i] To be precise, 0.86 arrest actions have occurred on average per month over that time frame.

[j] On September 6, 2014, several days after Ayman al-Zawahiri announced the creation of AQIS, a team of al-Qa`ida operatives penetrated Karachi’s Naval Dockyard and attempted to hijack and commandeer Pakistan naval ship Zulfiqar so it could be used to “attack US Navy patrol vessels in the Indian Ocean.” The attackers were stopped before they could take command of the vessel. Five members of Pakistan’s Navy were given the death penalty for the role they played in the attack. For quote and background, see “PNS Zulfiqar Attack: Five Naval Officers Get Death Penalty,” AFP, May 25, 2016, and Ray Sanchez, “New al Qaeda Branch in South Asia Launches First Assault,” CNN, September 19, 2014.

[k] For example, as Laurent Gayer noted in 2014, “thirteen public agencies are involved in the control and development of land in the city.” Laurent Gayer, Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City (Oxford University Press: New York, 2014), pp. 261-262.

[l] Given the low numbers of overall arrest actions per district per year, the reader should not over-interpret these results as definitively denoting which parts of Karachi are al-Qa`ida “hotzones.” The data only shows which locales al-Qa`ida suspects have been arrested in over time.

[m] The author recognizes that al-Qa`ida has always been a fairly ethnically diversified organization, and that while its 1990s membership was primarily composed of Arabs, it was never exclusively an Arab organization.

[n] Annualized projections of data collected through May 2017 suggest that 9.6 al-Qa`ida arrest actions will be conducted in Karachi in 2017, with 26.4 total suspects being arrested during the year.

Citations

[1] Nicholas Rasmussen, Hearing Before the Senate Homeland Security Governmental Affairs Committee, “Fifteen Years After 9/11: Threats to the Homeland,” September 27, 2016.

[2] For example, see Daniel R. Coats, Hearing Before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, “Worldwide Threat Assessment of the Intelligence Community,” May 11, 2017; Vincent R. Stewart, Hearing Before the Senate Armed Service Committee, “Worldwide Threat Assessment,” May 23, 2017; David E. Sanger and Mark Mazzetti, “New Estimate of Strength of al-Qaeda is Offered,” New York Times, June 30, 2010.

[3] See Joel Kotkin, “The World’s Fastest-Growing Megacities,” Forbes, April 8, 2013.

[4] For background, see Huma Yusuf, “Conflict Dynamics in Karachi,” Peaceworks 82 (2012), and Huma Yusuf, “Profiling the Violence in Karachi,” Pakistan Institute of Peace Studies, Conflict and Peace Studies 2:3 (July-September 2009). See also results from START’s Global Terrorism Database.

[5] Ali Soufan, The Black Banners: The Inside Story of 9/11 and the War Against al-Qaeda (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 2011), p. 88.

[6] “Hunting Bin Laden,” PBS Frontline, April 1999.

[7] Sherri Day, “Four Sentenced to Life in Prison for Roles in Embassy Bombings,” New York Times, October 18, 2001.

[8] Soufan, The Black Banners, p. 535.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Soufan, The Black Banners, p. 359; Terry McDermott and Josh Meyer, The Hunt for KSM: Inside the Pursuit and Takedown of the Real 9/11 Mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (Little, Brown, and Company: New York, 2012), pp. 21, 115, 138-145, 155-156, 186, 218-219, 225, 285; The 9/11 Commission Report (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 2004), pp. 149, 157. See also United States vs. Adis Medunjanin, Deposition, March 29, 2012.

[11] McDermott and Meyer, p. 138; The 9/11 Commission Report, pp. 157-158.

[12] The 9/11 Commission Report, p. 156. See also Cathy Scott Clark and Adrian Levy, The Exile: The Stunning Inside Story of Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda in Flight (Bloomsbury USA: New York, 2017), pp. 13-14.

[13] Clark and Levy, pp. 99-104.

[14] Tim Craig, “An offshoot of al-Qaeda is regrouping in Pakistan,” Washington Post, June 3, 2016.

[15] Ibid.

[16] For background on these districts, see http://www.kmc.gos.pk/Contents.aspx?id=84.

[17] Terry McDermott and Josh Meyer, “Inside the Mission to Catch Khalid Sheikh Mohammed,” Atlantic, April 2, 2012.

[18] McDermott and Meyer, p. 224. See also Clark and Levy, pp. 111, 118, and pp. 132-137.

[19] Jarret Brachman, “The Next Osama,” Foreign Policy, September 10, 2009.

[20] Ibid.

[21] McDermott and Meyer, p. 247; Clark and Levy, pp. 161-162.

[22] “Pakistan Captures Six ‘High Profile’ Al-Qa’ida Suspects,” AFP, April 30, 2003.

[23] Soufan, The Black Banners, p. 262.

[24] Syed Raza Hassan, “Pakistan Arrests Suspected South Asian al Qaeda Commander,” Reuters, December 12, 2014.

[25] Syed Raza Hassan, “Pakistan Arrests al Qaeda Operative Named in U.N. Sanctions List: Police,” Reuters, April 22, 2016. See also “Treasury Continues Efforts Targeting Terrorist Organizations Operating in Afghanistan and Pakistan,” U.S. Treasury Department Press Release, September 29, 2011.

[26] Zaffar Abbas, “The Pakistani al-Qaeda,” Herald, December 25, 2016 (originally published in August 2004). For background on al-Qa`ida’s dual strategy in the region, to include its efforts to build a resilient organization and focus on local capacity building, see Anne Stenersen, Al-Qaida in Afghanistan (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2017), pp. 165-175, and Anne Stenersen “Al-Qa`ida’s comeback in Afghanistan and its Implications,” CTC Sentinel 9:9 (2016). For additional context, see Don Rassler, “Al-Qaeda in South Asia: A Brief Assessment,” in eds. Aaron Y. Zelin, How al-Qaeda Survived Drones, Uprisings, and the Islamic State: The Nature of the Current Threat (Washington Institute for Near East Policy: Washington, D.C., 2017), pp. 77-86, as wellas “Growing Pakistanization of al-Qaeda,” News, December 14, 2010, and Stephen Tankel, “Going Native: The Pakistanization of al-Qaeda,” War on the Rocks, October 22, 2013.

[27] Craig.

[28] Ibid.

[29] For background, see Dexter Filkins, “The Journalist and the Spies: The Murder of a Journalist who Exposed Pakistan’s Secrets,” New Yorker, September 11, 2011, and Carlotta Gall, “Pakistani Journalist Who Covered Security and Terrorism is Found Dead,” New York Times, May 31, 2011.

[30] For example, see “Al-Hadeed News Report,” Al-Sahab in the Indian Subcontinent, March 6, 2016.

[31] Zelin.

Skip to content

Skip to content