Abstract: A key question for the future of Afghanistan is if the United States withdraws the remainder of its forces from the country, would Afghanistan’s security forces or the Taliban be stronger militarily? According to a net assessment conducted by the author across five factors—size, material resources, external support, force employment, and cohesion—the Taliban would have a slight military advantage if the United States withdraws the remainder of its troops from Afghanistan, which would then likely grow in a compounding fashion.

In the November/December 2020 issue of this publication, Seth Jones examined the ideology, objectives, structure, strategy, and tactics of the Afghan Taliban, as well as the group’s relationship to other non-state actors and sources of state support.1 In concluding his study, Jones considered the implications of the current situation in Afghanistan and wrote that:

… without a peace deal, the further withdrawal of U.S. forces … will likely shift the balance of power in favor of the Taliban. With continuing support from Pakistan, Russia, Iran, and terrorist groups like al-Qa`ida, it is the view of the author that the Taliban would eventually overthrow the Afghan government in Kabul.2

This is a critically important judgment for the future of U.S. policy on Afghanistan, and one that deserves more rigorous attention than Jones was able to dedicate in the concluding remarks of his paper. In addition to Jones’ article, there have been numerous recent, detailed works on the Taliban’s history,3 social resources and adaptations,4 political trajectory,5 and perspectives on peace negotiations.6 There are also various U.S. government reports that periodically give a wealth of information on the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF).7 Yet, a formal assessment of how Afghanistan’s security forces compare to the Taliban’s fighting forces in the context of U.S. troop withdrawals is lacking. In this article, the author therefore seeks to answer the question: If the United States withdraws the remainder of its forces from Afghanistan,a would the ANDSF or the Taliban be stronger militarily?

To do this, the author will conduct a net assessment of the two sides’ military forces in the projected absence of U.S. forces. In this context, net assessment refers to the practice of considering the strategic interactions of “blue” (friendly) and “red” (adversary) forces through the use of data that are widely available, in order to create strategic insights that lead to decisive advantage.8 While there are many elements that could be focused on while conducting such an assessment and there is a great body of literature about which are most important,9 the author examines five here: size, material resources (i.e., money and technology), external support, force employment, and cohesion. The first four are included because they address the fundamental inputs to military effectiveness: people, things, and the ability of people to use those things. The author includes cohesion because it speaks to the will of both sides to fight10 and because it is particularly important in the context of the war in Afghanistan and efforts to end it via a negotiated settlement.11 Of note, the author does not consider the possible impacts of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 due to a paucity of reliable data and no clear indication that its consideration would change the results of the assessment. This article now examines each of these factors for both sides, then conducts a net assessment of the five factors, before providing an answer to the central question along with some of the implications.

Size

Taliban

The number of people in the Taliban’s fighting forces is difficult to determine precisely, but a variety of sources give an estimate of 60,000 core fighters, give or take 10-20 percent.12 b The most systematic public study of the Taliban’s size (from 2017) concluded that the group’s total manpower exceeds 200,000 individuals, which includes around 60,000 core fighters, another 90,000 members of local militias, and tens of thousands of facilitators and support elements.13 These numbers are considerable increases over official U.S. estimates of around 20,000 fighters that were provided in 201414 and illustrate the group’s ability to recruit and deploy new fighters in recent years. They also illustrate the Taliban’s ability to withstand significant casualties—estimated to be in the range of thousands per year.15 As a Taliban military commander recently commented, “We see this fight as worship. So if a brother is killed, the second brother won’t disappoint God’s wish—he’ll step into the brother’s shoes.”16

ANDSF

Afghanistan’s security forces have an authorized total end-strength of 352,000 personnel.17 c Yet, the country has never been able to fill all of those billets. As of July 2020, the Afghan Ministry of Defense (MOD)—which includes the army, air force, and special operations forces (SOF)—had 185,478 personnel. The Afghan Ministry of Interior (MOI)—which includes a variety of police forces—numbered 103,224. This gives a total of 288,702 security force personnel, or 82 percent of total authorized end-strength.18 d While analysts have greater confidence in these numbers now than in the past as a result of a new biometric manpower system in Afghanistan that was implemented to address the phenomenon of “ghost soldiers,”19 e they nonetheless represent an upper bound on the true size of the fighting force—they are merely the number of filled billets. A 2014 study of the Afghan army found that its force structure was about 60 percent combat personnel,20 but the number of soldiers showing up for duty each day is even lower (since some soldiers are always sick, on leave, etc.). One official U.S. reference quoted an on-hand percentage of about 90 percent.21 Using these figures together (and subtracting the roughly 8,000 personnel in the Afghan Air Force (AAF)22) gives an estimated on-hand army fighting force of about 96,000 soldiers. The Afghan police are a much leaner force, with only about 11 percent as administrative and support personnel for the 89 percent that are patrolmen.23 Assuming a 90 percent on-hand rate for the police as well gives about 83,000 patrolmen. All told then, the ANDSF are likely fielding a fighting force in the vicinity of 180,000 combat personnel each day.

Material Resources

Taliban

There is no consensus on the Taliban’s yearly revenue total. Official United Nations, government, and some independent estimates range from $300 million to $1.6 billion per year,24 with the United States estimating that up to 60 percent of these totals comes from Taliban involvement in the drug trade.25 These numbers are disputed, however, by David Mansfield’s detailed work on illicit economies and drug production in Afghanistan, which suggests that the Taliban’s share of drug proceeds is significantly less than popularly understood and therefore the group’s annual revenues are much less as well.26

What is clear is that the Taliban have for years generated some amount of funding from the drug trade (e.g., via taxes and protection payments),27 whether on opiates,28 hashish,29 or more recently, crystal methamphetamine.30 In recent years, the Taliban have also greatly diversified their portfolio of funding sources.31 The most notable expanded source is illegal mining (e.g., precious stones,32 talc,33 and rare earth minerals34), which some reports now put near or at the same level of revenue for the group as drugs.f The Taliban also actively tax the areas they control (e.g., on infrastructure, utilities, agriculture and social industry35), and generate additional revenue from smuggling,36 extortion,37 kidnapping for ransom,38 and private donations.39

The Taliban have traditionally relied on some degree of centralization of revenue collection, such as that from formal taxation, alongside a redistributive resource model.40 But in recent years, the group has given local commanders more leeway in generating revenue (e.g., via war booty) and expending resources to maintain its war machine. Recent interviews with Taliban recruitment officials and commanders suggest that the group does not pay its fighters regular salaries, but rather covers their expenses: “we take care of their pocket money, the gas for their motorcycle, their trip expenses. And if they capture spoils, that is their earning.”41

The Taliban have also, in recent years, increasingly benefitted from overruns of vulnerable Afghan security force checkpoints and installations, which has afforded them a wealth of armaments mostly procured by the United States, including armored vehicles, night-vision devices, Western rifles, laser designators, and advanced optics.42 And while the Taliban have been using commercial drones to conduct aerial surveillance for years, they have only recently begun routinely weaponizing them for attacks against ANDSF positions.43

ANDSF

Over the past five years, the ANDSF have been funded at around $5-6 billion per year.44 The United States has provided about 75 percent of this funding via the Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF) and has generally dictated how that money is spent, with another $1 billion or so coming from international partners and the Afghan government contributing roughly $300-400 million more.45 In fiscal year (FY) 2020, Congress appropriated $1.6 billion for the Afghan Army, $1.2 billion for the AAF, $728 million for Afghan special security forces (ASSF),g and $660 million for the police.46 International donors provide funding for the ANDSF either bilaterally or through one of two multilateral channels: the NATO ANA Trust Fund or the Law and Order Trust Fund Afghanistan.47

These sources of funding cover all of the expenses of the ANDSF, though international sources have typically been used to cover salaries, procurement of end-use items (e.g., weapons, vehicles, communications equipment, aircraft), maintenance and sustainment of those items, and training on how to use them. Afghan government contributions have typically been used for food and uniforms.48

As a result of tens of billions of dollars of international expenditures, the ANDSF today have an air force consisting of 174 aircraft (a mix of transport and attack helicopters, and transport, surveillance, and attack fixed wing platforms), some of the region’s best SOF, and an army that boasts heavy artillery, mortars, thousands of armored vehicles and personnel carriers, tactical drones and technical intelligence capabilities, military grade communications gear, and Western weapons and munitions (including technology to operate at night).49

External Support

Taliban

The Taliban are the beneficiaries of support from a number of external actors. Al-Qa`ida has been a long-time ally for the group,50 providing “mentors and advisers who are embedded with the Taliban, providing advice, guidance and financial support.”51 The relationship between al-Qa`ida and the Haqqani-led portion of the Taliban is particularly strong.52 The Taliban also receive funds, arms, and training from Iran.53 Taliban sources have openly admitted to this support, as well as to the receipt of military supplies from Russia.54 Private donors from within the Gulf Arab states have also been a consistent source of funding for the Taliban.55

The most significant source of external support for the Taliban, however, comes from Pakistan.56 In his book on the subject, Steve Coll discusses at length the nature of this support, which includes sanctuary for senior Taliban leaders, but also Pakistan army and intelligence service support to recruitment and training of Taliban fighters in areas near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, support to deployment of those fighters into Afghanistan, and support to their rest and recuperation (including medical support) back inside Pakistan.57 Pakistan has also provided the Taliban with military materiel, as well as strategic and operational advice for the group’s operations in Afghanistan.58 While Pakistan took great pains to hide this support for years, the amount of reporting on it today is voluminous, and a former Director General of Pakistan’s intelligence agency recently admitted to supporting the Taliban “in any way he could.”59

ANDSF

As discussed in the prior section, the ANDSF receive over 90 percent of their funding from international sources, which pays for nearly everything the force needs except for food and uniforms. They also receive training and advisory support from international forces. Most of that training occurs in Afghanistan, though the United States has also been training Afghan pilots at Moody Air Force Base in Georgia.60

Force Employment

Taliban

Since the mid-2000s, the Taliban have been executing an “outside-in” military strategy.61 h In this approach, they first used sanctuaries in Pakistan (and to a lesser extent, Iran62) to generate military manpower and materiel, which they used to seize rural areas in Afghanistan.63 They then used their control of those areas to generate funding (as described above) and additional manpower, which they have used to seize adjacent territory. More recently, they have been using consolidated tracts of rural territory to project military power into areas surrounding Afghanistan’s district and provincial capitals, with the goal of seizing and holding them in order to undermine the political control and popular standing of the government. Ultimately, the Taliban’s military forces would like to follow this strategy to pressure and seize control of Kabul, at which time the group could claim military victory and political control of the country.64

To advance this strategy, the Taliban use a wide variety of tactics, on which they provide regular training for their military forces (with external support, as described above).65 These include guerrilla tactics (e.g., ambushes, raids, hit-and-run attacks);66 conventional tactics (e.g., massed assaults, multi-prong attacks);67 terrorist tactics (e.g., car and truck bombs);68 intelligence activities;69 intimidation (e.g., targeted assassinations, kidnappings, night letters, death threats);70 influence and information warfare (e.g., media and information operations, shadow diplomacy, destroying communications infrastructure);71 and criminal activities (e.g., drugs, smuggling, protection rackets, kidnapping for ransom).72 To implement these tactics, the Taliban use primarily Soviet-style small arms and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), though they also have limited numbers of heavy machine guns, heavy mortars, anti-armor weapons, and sniper rifles.73 In recent years, the Taliban have been able to overrun numerous ANDSF checkpoints and installations, affording them more advanced gear such as up-armored vehicles, night-vision devices, and laser optics.74 The group has used this advanced equipment to conduct assaults on hardened ANDSF facilities75 and to arm its relatively new “Red Unit,” which is an elite infantry unit (estimated to number from several hundred to a thousand members) used to spearhead and support attacks against particularly important or sensitive targets across the country.76

ANDSF

For years, the ANDSF’s strategy for defending the country from the Taliban relied primarily on two main elements: establishing heavy presence (a “ring of steel”) in and around major population areas and conducting large-scale (e.g., division- or corps-sized) clearing operations to try and retake areas that had been seized by the Taliban.77 More recently, at the behest of the current U.S. commander in Afghanistan—and as a result of significant growth in these forces as part of President Ashraf Ghani’s “ANDSF Roadmap” initiative78—the ANDSF have moved away from this model and relied far more heavily on the destructive and disruptive power of the AAF and ASSF in a move away from a counterinsurgency-centric strategy and toward one based on military pressure and attrition. In this mode of operations, elements of the ASSF like the Afghan Commandos conduct direct action raids (often enabled by the AAF) and generate intelligence to cue strikes by the AAF against Taliban targets.79

Despite all of its technical capabilities and the preferences of U.S. military leadership in Afghanistan, the preferred mode of operation of the country’s army and police remains wide-area security via the use of over 10,000 static checkpoints.80 This is largely the result of the ANDSF’s major shortcomings, which have persistently included poor leadership, high attrition and inability to effectively manage personnel, rampant corruption, and poor sustainment, maintenance, and logistics practices.81 These shortcomings—along with the desire of Afghan political actors to have a visible ANDSF presence in their areas of influence and the checkpoints’ role in extorting local populations82—have made them the lowest common denominator and easiest mode of operation for the ANDSF. The U.S. military has been trying for years to change this dynamic, mostly unsuccessfully.83

Cohesion

Taliban

The military scholar Jasen Castillo cites military cohesion as a dependent variable consisting of two factors: staying power (the ability of a military force to hold together and fight even as the odds of military victory diminish) and battlefield performance (the willingness of units to fight with determination and flexibility).84 He then relates these factors to two independent variables: degree of regime control and degree of organizational autonomy.85

The Taliban—which exhibit a high degree of control over their fighters and the communities in the areas they control,86 and a high degree of organizational autonomy via their regional shura, mahaz (front), and qet’a (unit) structures87—constitute what Castillo calls a “messianic military.”88 i This type of military is characterized by strong cohesion, reflected in strong staying power (a military that “collapses only when an adversary possesses crushing material superiority”) and strong battlefield performance (whereby “most units fight with determination and flexibility”).89

This observation based on Castillo’s theory is backed by recent studies employing other methods. For many years, analysts studying the Taliban have commented on perceived issues with the group’s cohesiveness and possibilities of fragmentation.90 As evidence, they have cited events such as infighting among Taliban commanders,91 the emergence of rival regional shuras,92 widespread disillusion among rank and file with Taliban leadership, and the direction of the seemingly endless war.93 Yet, recent detailed studies of the Taliban’s structure, history (e.g., the group’s reaction to the announced death of Mullah Omar), and evolution in the context of studies on insurgent group cohesion have concluded that the Taliban are today a relatively cohesive group.94 This cohesion likely stems from four major sources: strong vertical and horizontal ties within and across the entirety of the movement and the communities in which it operates;95 strong and continuous internal socialization of key issues (e.g., peace talks) and focus on obedience and cohesion;96 the group’s organization for, and perceived successes on, the battlefield and in negotiations;97 and its strong base of material resources.98

ANDSF

The Afghan government, on the other hand, maintains a relatively low degree of control over the areas supposedly under its protection,j and it affords its military a very low degree of organizational autonomy.k This results in the ANDSF being what Castillo calls an “apathetic military.”99 This type is characterized by a low degree of cohesion, reflected in weak staying power (a military that “collapses quickly as probability of victory decreases”) and weak battlefield performance (whereby “only the best units fight with determination and flexibility”).100 Examples of weak ANDSF staying power, as defined by Castillo, can be seen at the micro level—in the form of near-daily Taliban overruns of poorly defended ANDSF checkpoints101—and at the macro level—in the form of the near-collapse of the Army’s 215th Corps in 2015102 or the collapse of ANDSF defenses around Ghazni in 2018.103 Examples of weak battlefield performance can be seen in the government’s increasing reliance on the AAF and ASSF as the most capable units within the ANDSF.l

In addition to these structural examples of weak cohesion, at the individual level, the ANDSF have been plagued with a high level of attrition (on the order of 30 percent per year) for many years, with the primary factor being so-called “dropped from rolls,” or soldiers and police that desert their unit and do not return within 30 days.104 Such desertions accounted for 66 percent of Afghan army and 73 percent of police attrition in 2020.105 According to the U.S. Department of Defense, desertions “occur for a variety of reasons, including poor unit leadership, low pay or delays in pay, austere living conditions, denial of leave, and intimidation by insurgents.” The single greatest contributor to desertions is poor leadership,106 which a former U.S. commander in Afghanistan also called “the greatest weakness of the Afghan security forces.”107

Net Assessment

Having discussed size, material resources, external support, force employment, and cohesion for both the Taliban and the ANDSF, the author now conducts a net assessment of those factors in the projected absence of U.S. forces.

Size

A glance at commonly cited numbers would leave the impression that Afghanistan’s security forces far outnumber the Taliban, by as much as a factor of four or five (352,000 to 60,000). A more nuanced comparison, however, suggests a different story. Most estimates put the number of Taliban frontline fighters around 60,000. The comparable number of Afghan soldiers is about 96,000. The only detailed public estimate of the Taliban’s militia elements—its “holding” force—is around 90,000 individuals.108 The comparable government force is the police, which has about the same number of people (84,000) in the field. Thus, a purely military comparison of strength shows that the government’s fighting force is only about 1.5 times the strength of the Taliban’s, while the two sides’ holding forces are roughly equivalent.109 Assessment: Slight ANDSF advantage.

Material Resources

The Taliban have a much leaner (i.e., fewer administrative and support elements) and less technically sophisticated fighting force than the Afghan government—lacking an air force, heavy artillery, a fleet of armored vehicles, and the like. As such, the group’s military element costs significantly less than the ANDSF. A calculation of the total cost of the Taliban’s fighting force relative to the group’s revenue was impossible given a lack of reliable data. What is clear is that the Taliban have a significantly diversified portfolio of funding streams and there has been no significant reporting in recent years of the group suffering from financial deficiencies.

The ANDSF, on the other hand, are vastly more advanced than the Taliban in terms of technical capabilities. But they also cost far more than the Afghan government can afford.110 The United States and its allies have thus far been willing to pay the multi-billion dollar per year price tag for the ANDSF—and have committed to providing some degree of security assistance through 2024 (though the scope of that assistance is to be determined).111 The ANDSF are thus heavily reliant on just a few sources of funding, and there is little reason to think the Afghan government will reach fiscal self-sustainability anytime soon.112 Afghanistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) has only averaged 2-3 percent growth in recent years, and decades of war have stunted the development of most domestic industries.113 Afghan government funding for its security forces (which is only about 8-9 percent of their total cost) is equivalent to roughly two percent of its GDP and one fourth of total government revenues—levels that are already extremely high for a developing country.114 The United States’ own assessment is that “given the persistence of the insurgency and continued slow growth of the Afghan economy … full self-sufficiency by 2024 does not appear realistic, even if levels of violence and, with it, the ANDSF force structure, reduce significantly.”115

Critically, the ANDSF will continue to be reliant for the foreseeable future on contract logistics support for aircraft, vehicles, and other technical equipment.116 For example, sustainment costs make up nearly 64 percent of the AAF budget, and sustainment of the AAF alone is just over 13 percent of the total amount of U.S.-provided funding.117 The U.S. Defense Department has assessed that without this funding, “the AAF’s ability to sustain critical air-to-ground capability will fail and the fleet will steadily become inoperable.”118 Without these capabilities, ground units will not be able to execute operations in locations where the terrain prohibits the use of traditional ground transportation, thereby limiting operational effectiveness.119 Assessment: Strong Taliban advantage for funding relative to requirements; strong ANDSF advantage for technical capabilities.

External Support

As just discussed, the Taliban appear to have a sustainable, diversified funding model for their fighting forces. Thus, while the group benefits from external support from the likes of Russia, Iran, and even al-Qa`ida, it does not appear to require any of this support to continue its operations in Afghanistan. Pakistan’s support to the Taliban, however, has been essential to the group’s success to date.120 While the Taliban could, in theory, attempt to fully move their organization into areas they control in Afghanistan, doing so would be not only a serious logistical undertaking (e.g., since many of the group’s recruitment efforts and training locations are centered in Pakistan’s border areas) but would also expose the group to persistent threats of attack by the ANDSF (most notably, by air). Taliban leaders are thus quite reliant on sanctuaries in Pakistan for their own safety and comfort. While this has occasionally made them vulnerable to pressure by Pakistan (the arrest of Mullah Baradar is an important case in this regard121), this pressure has thus far not been significant enough to warrant the group completely decamping to Afghanistan.

The ANDSF are similarly reliant on external support, though critically in different ways. Costing many times what the Taliban’s fighting force costs, the ANDSF are almost entirely reliant on foreign funding, most notably for salaries and the costs of procuring, maintaining, and sustaining the force’s technical capabilities. The continued provision of this funding is at risk in the absence of U.S. advisors to provide oversight of the billions of dollars in aid such support requires.122 Even if it were to continue with no U.S. troops on the ground, there are other important roles played by advisors that would end. For example, only a fraction of the funding provided by the United States and its allies for the ANDSF is given to the Afghan government directly (as “on budget” funds), with the rest being spent “off budget” by U.S. military entities in Kabul.123 The Afghan Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior persistently struggle to spend even the on-budget amount, averaging only about a 60 percent execution rate.124 U.S. advisors have been getting around this by doing their own procurement for goods and services down to Army corps and provincial headquarters levels—a practice that would disappear in the absence of those advisors.125 Assessment: Draw; both forces have significant external dependencies.

Force Employment

At the strategic level, the Taliban have consistently employed their “outside in” strategy since the mid-2000s, and have steadily eroded the government’s territorial control since then.126 This is roughly the same strategy that was successfully employed by the mujahideen against the Soviet occupation and by the Taliban in its initial conquest of Afghanistan.127 The Afghan government, on the other hand, has vacillated in its strategic approach since the end of the U.S. surge in 2014. In the 2015-2018 timeframe, the ANDSF implemented what was called a “hold-fight-disrupt” strategy. As described by the commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan at the time:

This methodology designated areas which the ANDSF would “Hold” to prevent the loss of major population centers and other strategic areas to the enemy, those for which the ANDSF would immediately “Fight” to retain and those areas where they would assume risk by only “Disrupting” the enemy if they appeared. The ANDSF designed their phased operational campaign plan, called Operation SHAFAQ, to anticipate and counter the enemy’s main and supporting efforts. This prioritization caused them to concentrate forces in more populous areas and remove forces from more remote, sparsely inhabited areas.128

It is perhaps not surprising then that the last reported official U.S. assessment of territorial control (in October 2018) showed the government in control of 54 percent of the country’s districts, with the Taliban in control of 12 percent and the rest contested.129 In 2015, the same source had assessed the Afghan government as being in control of 72 percent of districts.130 The dramatic decrease in government control (from 72 to 54 percent) was commensurate with both the introduction of the “hold-fight-disrupt” strategy and the dramatic increase in estimates of Taliban strength (from 20,000 to 60,000) over roughly the same timeframe.

By late 2018, the new U.S. commander in Afghanistan shifted to an attrition strategy, featuring offensive operations by the ASSF and AAF, with the rest of the ANDSF largely in supporting roles (e.g., attempting to hold ground via checkpoints).131 This shift increased the number of Taliban casualties through more aggressive air and SOF targeting of Taliban fighters, and there are indications that the Taliban wanted that bleeding to stop.132 But overall, it failed to stem the Taliban’s steady encroachment on Afghanistan’s major cities. Today, approximately 16 of the country’s 34 provincial capitals are effectively surrounded by Taliban-controlled or -contested areas.m Assessment: Slight Taliban advantage.

Cohesion

Application of Castillo’s theory of military cohesion to both the Taliban and the ANDSF shows the former to be a more cohesive fighting force than the ANDSF. This theoretical conclusion is supported by independent analyses of the Taliban in the context of theories of insurgency cohesion, as well as by observations of ANDSF manpower trends. Assessment: Strong Taliban advantage.

Summary

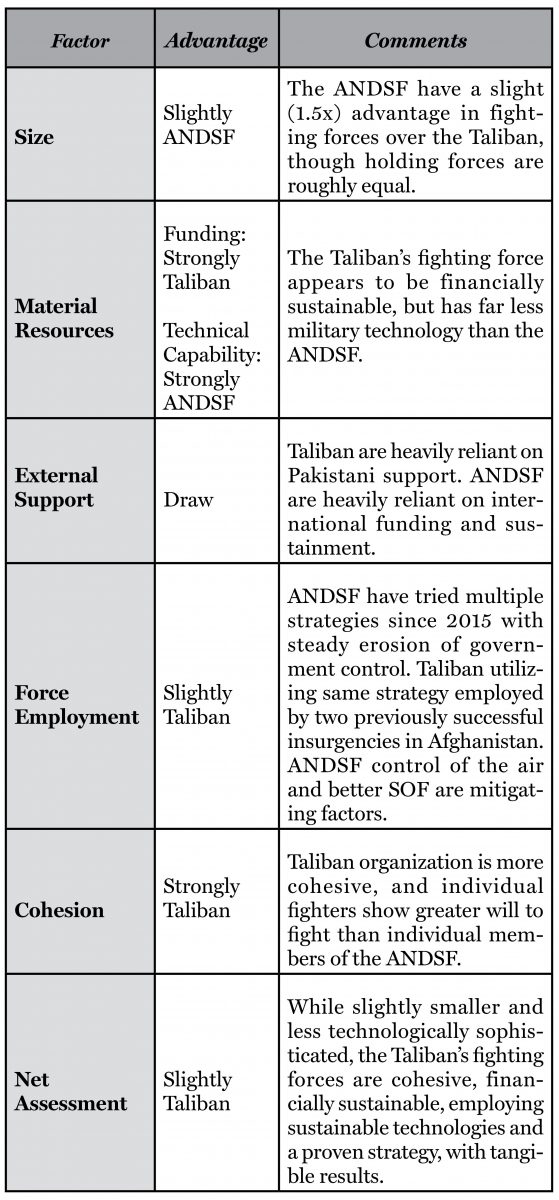

Table 1 summarizes the comparative discussion of each factor and presents a net assessment of each. As the last row indicates, the net assessment of these factors tilts slightly to the advantage of the Taliban. While the ANDSF field a slightly larger fighting force and have vastly more technical capabilities than the Taliban, they are almost entirely reliant on external funding (75 percent from the United States)—most critically, for salaries, procurement, and sustainment of those technical capabilities. They have also not been able to identify an effective strategy, and they are aptly described by Castillo’s theory as an “apathetic military.”133 The Taliban, on the other hand, field a slightly smaller and far less technically sophisticated fighting force than the ANDSF. But that force is cohesive and appears to be financially sustainable, and is employing technologies that are sustainable and a strategy that has been proven to work in Afghanistan. Those advantages are evident in tangible successes of the Taliban’s military machine on the battlefield, most notably in the steady erosion of government control since the end of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission in 2015.

Conclusion and Implications

The author set out in this article to address the question: If the United States withdraws the remainder of its forces from Afghanistan, would the ANDSF or the Taliban be stronger militarily? Having conducted a net assessment of the Taliban and ANDSF in the projected absence of U.S. troops across five factors—size, material resources, external support, force employment, and cohesion—the author concludes that the answer is slightly in favor of the Taliban. This finding has numerous implications, but this article now focuses on two immediate suggestions for improving the military balance in Afghanistan.

First, the ANDSF would be well served by significantly increasing its focus on recruitment. While authorized for an end strength of 352,000 soldiers and patrolmen, the ANDSF has never approached that figure and is currently about 63,000 personnel short. In other words, the ANDSF are missing a cadre roughly the size of the Taliban’s entire fighting force. Growing the ANDSF to their approved end strength would give the force a much stronger size advantage than it currently enjoys. While size is not everything, in an attrition war of territorial control—which the war in Afghanistan has steadily become—it is a critical factor. Having a larger force may also help mitigate the risk of increased desertions or defections by members of the ANDSF if U.S. advisors depart or if the Taliban continue to gain territory.134

Second, the U.S.-led advisory mission since 2015 has not been helping the ANDSF to win, so much as it has been slowing the ANDSF’s lossesn by improving the force’s technological advantages over the Taliban. As this analysis shows, that advantage is today quite large. However, it has come at the expense of dependency—the ANDSF are currently far too complex and expensive for the government to sustain. This has been mitigated for years by advisors who have been directly performing critical support and sustainment functions of the ANDSF. If the United States fully withdraws those advisors, as stipulated in the U.S.-Taliban agreement,o the Taliban’s slight military advantage at that point would begin to grow, as a result of at least two factors: (1) the ANDSF’s technical advantage will erode as maintenance and support functions currently performed or overseen by advisors slow down or cease; and (2) the ANDSF’s major vulnerability—its dependence on foreign funding—will increasingly be at risk, since without U.S. troops in Afghanistan, the United States would have limited ability for oversight of security assistance and less “skin in the game.” Both factors portend likely declines in U.S. security assistance funding (which may be exacerbated by continued corruption in Afghanistan’s Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior135 ). Further, the resultant increase of the Taliban’s military advantage is likely to be non-linear. This will result both from increasing overuse and cannibalization of technical capabilities (e.g., helicopters) and from the ANDSF’s general lack of “staying power” as predicted by Castillo’s theory.136 To stem the rate of this possible future decline, the United States would be wise to immediately do everything it can to decrease the complexity of ANDSF equipment and systems, and increase the sustainability of the force. This would ideally include significant adjustments to both force structure and force employment.137

In conclusion, the author finds that if the United States were to withdraw the remainder of its forces from Afghanistan, the Taliban would enjoy a slight military advantage that would increase in a compounding manner over time. While the Taliban’s chief spokesman recently “said that the group’s primary goal is to settle the issues through talks and that a ‘military solution’ would be used only as a last resort,”138 the results of this analysis suggest that the United States and government of Afghanistan would be wise to vigorously pursue negotiations while U.S. forces remain and avoid tempting the Taliban to exploit the military advantage it would have in their absence. CTC

Dr. Jonathan Schroden directs the Center for Stability and Development and the Special Operations Program at the CNA Corporation, a non-profit, non-partisan research and analysis organization based in Arlington, Virginia. His work at CNA has focused on counterterrorism and counterinsurgency activities across much of the Middle East and South Asia, including numerous deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. The views expressed here are his and do not necessarily represent those of CNA, the Department of the Navy, or the Department of Defense. Follow @jjschroden

© 2021 Jonathan Schroden

Substantive Notes

[a] The author assumes that U.S. troops will either withdraw in accordance with the terms of the U.S.-Taliban agreement (which states all U.S. troops must depart by May 1, 2021, if the Taliban meet their obligations) or within a single six-month extension as has been recently suggested. “Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan which is not recognized by the United States as a state and is known as the Taliban and the United States of America,” U.S. Department of State, February 29, 2020; Barnett R. Rubin, “How Biden can bring U.S. troops home from Afghanistan,” Responsible Statecraft, January 11, 2021.

[b] It is typically not clear whether these estimates include the number of personnel in the Haqqani network, which has at various times been considered separate from, or integrated with, the Taliban.

[c] This number does not include 30,000 Afghan Local Police, which are in the process of being disbanded due to discontinuation of funding from the United States.

[d] There are an additional 10,741 civilians working in the ministries.

[e] The Afghan Personnel and Pay System was implemented over the past several years to identify and remove ghost soldiers from the rolls of the ANDSF, which had been estimated to be as high as 40 percent of the reported strength in some areas. See John F. Sopko, “Assessing the Capabilities and Effectiveness of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces,” Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, February 12, 2016.

[f] The Taliban’s own Stones and Mines Commission has stated the group earns $400 million per year from mining. See Matthew Dupee, “The Taliban Stones Commission and the Insurgent Windfall from Illegal Mining,” CTC Sentinel 10:3 (2017); Hanif Sufizada, “The Taliban are Megarich—Here’s Where They Get the Money They Use to Wage War in Afghanistan,” Conversation, December 8, 2020; and Frud Bezhan, “Exclusive: Taliban’s Expanding ‘Financial Power’ Could Make It ‘Impervious’ To Pressure, Confidential Report Warns,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 16, 2020.

[g] ASSF include Afghan Army SOF, the AAF’s Special Mission Wing, and various special police units.

[h] This military strategy complements the Taliban’s political strategy. See, for example, Kriti M. Shah, “The Taliban’s Political Strategy,” ORF Raisina Debates, September 19, 2020.

[i] Note that Castillo only applies his theory to state (national) militaries, and some would rightly question this author’s application of it to the Taliban (nominally a non-state group). However, the Taliban today control—and govern—significant swaths of Afghanistan’s countryside; have their own governance, diplomatic, military, and information structures; levy taxes; and in many ways act like a pseudo-state. The author therefore finds it instructive to extend Castillo’s theory to the Taliban’s military component.

[j] Examples of this include both the frequent attacks that occur inside Afghanistan’s major cities, the ongoing nationwide campaign of targeted assassinations, and the fact that the Taliban are able to project their own governance activities into areas nominally under government control. See Emma Graham-Harrison, “In Afghanistan, Fears of Assassination Overshadow Hopes of Peace,” Guardian, November 21, 2020, and Ashley Jackson, “Life Under the Taliban Shadow Government,” Overseas Development Institute, June 2018, p. 5.

[k] This can be seen in the frequent reach of the most senior Afghan security officials (e.g., the Ministers of Defense and Interior) to tactical levels—for example, by directing tactical operations of security forces directly via cell phone from Kabul. Author discussions with U.S. military personnel, 2008-2020, and “A Force in Fragments: Reconstituting the Afghan National Army,” Asia Report 190, International Crisis Group, May 12, 2010.

[l] In 2017, the U.S. commander in Afghanistan stated that the ASSF conducted 70 percent of all Afghan army offensive operations. See John W. Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces – Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” February 2017, p. 13. This proportion has steadily increased since that time. “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 30, 2020, p. 9.

[m] U.S. forces in Afghanistan no longer produce assessments of district control in Afghanistan, but FDD’s Long War Journal has continued to do so via independent means. FDD’s current assessment shows the Afghan government in control of 133 (33 percent) of the country’s districts, with the Taliban in control of 75 (19 percent) and another 187 (47 percent) contested. (The last three districts are unconfirmed.) See Bill Roggio and Alexandra Gutowski, “Mapping Taliban Control,” FDD’s Long War Journal. The author calculated the number of provincial capitals surrounded by Taliban controlled/contested areas by comparing FDD’s map to a political map of Afghanistan.

[n] This is most evident in the goal of controlling 80 percent of Afghanistan’s territory within two years that was stated by the U.S. commander in Afghanistan in 2017. Not only was that goal not achieved, the Afghan government has demonstrably lost ground since it was stated. See “Department of Defense Press Briefing by General Nicholson via Teleconference from Kabul, Afghanistan.”

[o] The agreement stipulates that, subject to the Taliban meeting their obligations under the agreement’s terms (which include not allowing terrorist groups like al-Qa`ida to use Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States and its allies), the “United States, its allies, and the Coalition will complete withdrawal of all remaining forces from Afghanistan” within 14 months of the agreement’s signing (which is generally accepted to be May 1, 2021). See “Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan between the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan which is not recognized by the United States as a state and is known as the Taliban and the United States of America.”

[p] It is noteworthy that Congress has now required the Defense Department to withhold 5-15 percent of ASFF funding for the ANDSF if certain conditions (e.g., pertaining to corruption) are not met by the Afghan government. See “William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021,” Section 1521, 116th Congress of the United States of America.

Citations

[1] Seth G. Jones, “Afghanistan’s Future Emirate? The Taliban and the Struggle for Afghanistan,” CTC Sentinel 13:11 (2020).

[2] Ibid., p. 8.

[3] Antonio Giustozzi, The Taliban at War: 2001-2018 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[7] See, for example, “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” U.S. Department of Defense, December 2020; “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), December 31, 2020; and “Operation Freedom’s Sentinel: Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress,” October 1, 2020-December 31, 2020.

[8] Those unfamiliar with net assessment are encouraged to see Paul Bracken, “Net Assessment: A Practical Guide,” Parameters (2006): pp. 90-100.

[9] See, for example, the list of works cited for the author’s course on military power and effectiveness, available at Jonathan Schroden, “Today begins my course ‘Military Power & Effectiveness’ …,” Twitter, January 15, 2020.

[10] Jasen J. Castillo, Endurance and War: The National Sources of Military Cohesion (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), p. xii.

[12] J.P. Lawrence, “Afghan general: There are a lot more Taliban fighters than previously thought,” Stars and Stripes, June 12, 2018; Courtney Kube, “The Taliban is gaining strength and territory in Afghanistan,” NBC News, January 30, 2018; Jeff Schogol, “Once Described As On Its ‘Back Foot,’ Taliban Number Around 60,000, General Says,” Task and Purpose, December 4, 2018; Clayton Thomas, “Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service Report R45122, November 10, 2020, p. 11; “Eleventh Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” United Nations Security Council, May 27, 2020, p. 11; Antonio Giustozzi, “Afghanistan: Taliban’s Organization and Structure,” Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre (Landinfo), August 23, 2017.

[13] While Giustozzi does not explicitly state that his estimates of Taliban strength include the number of Haqqani network members, the author has assumed that they do based on the nature of Giustozzi’s discussion (e.g., his description of the Haqqanis’ Miran Shah shura as being under the authority of the Taliban’s Rahbari Shura (leadership council)). See Giustozzi, “Afghanistan: Taliban’s Organization and Structure,” pp. 5, 12. Giustozzi’s estimates have been endorsed by several other analysts. See Rupert Stone, “The US is greatly downplaying the size of the Afghan Taliban,” TRT World, January 7, 2019.

[14] Kube.

[17] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), October 30, 2020, p. 80; “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 30, 2020, p. 29.

[18] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” October 30, 2020, p. 80.

[19] Ibid.; “Report on Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 2015, p. 38.

[20] Jonathan Schroden et al., Independent Assessment of the Afghan National Security Forces, CNA DRM-2014-U-006815-Final, January 2014, p. 134.

[21] “Report on Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 2015, p. 34.

[22] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” October 30, 2020, p. 80.

[23] “Justification for FY 2021 Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) Afghanistan Security Forces Fund,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, February 2020, p. 13.

[24] “Eleventh Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” p. 14; Hanif Sufizada, “The Taliban are Megarich—Here’s Where They Get the Money They Use to Wage War in Afghanistan,” Conversation, December 8, 2020.

[25] Chris Sheedy, “From Accounting to Bringing Down the Taliban,” In The Black, September 1, 2018; John W. Nicholson, “Department of Defense Press Briefing by General Nicholson in the Pentagon Briefing Room,” U.S. Department of Defense press briefing, December 2, 2016.

[26] David Mansfield, “Understanding Control and Influence: What Opium Poppy and Tax Reveal about the Writ of the Afghan State,” Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, August 2017; David Mansfield, “Denying Revenue or Wasting Money? Assessing the Impact of the Air Campaign Against ‘Drug Labs’ in Afghanistan,” LSE International Drug Policy Unit, April 2019; David Mansfield, “The Sun Cannot be Hidden by Two Fingers: Illicit Drugs and the Discussions on a Political Settlement in Afghanistan,” Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, May 2019. Mansfield’s criticisms appear to be supported by some recent work by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). See Michael Osman, Murat Yildiz, and Hamid Azizi, “’Voices of the Quchaqbar’—Understanding Opiate Trafficking in Afghanistan from the Perspective of Drug Traffickers,” UNODC, January 2020, pp. 40-41.

[27] Ibid. See also the yearly UNODC reports on poppy production in Afghanistan (e.g., “Afghanistan Opium Survey 2018: Challenges to Sustainable Development, Peace, and Security,” UNODC, July 2019), as well as Dawood Azami, “Afghanistan: How does the Taliban make money?” BBC, December 22, 2018; and Sheedy.

[29] Ibid.

[31] “Tenth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” United Nations Security Council, June 13, 2019; Matthew Dupee, “The Taliban Stones Commission and the Insurgent Windfall from Illegal Mining,” CTC Sentinel 10:3 (2017).

[32] “Sources of funding (including self-funding) for the major groupings that perpetrate IED incidents –Taliban;” Dupee.

[33] “At Any Price We Will Take the Mines: The Islamic State, the Taliban, and Afghanistan’s White Talc Mountains,” Global Witness, May 2018; Dupee.

[34] “Eleventh Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” p. 16.

[35] Ibid., p. 14; Azami, “Afghanistan: How does the Taliban Make Money?;” Mujib Mashal and Najim Rahim, “Taliban, Collecting Bills for Afghan Utilities, Tap New Revenue Sources,” New York Times, January 28, 2017.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Frud Bezhan, “Exclusive: Taliban’s Expanding ‘Financial Power’ Could Make It ‘Impervious’ To Pressure, Confidential Report Warns,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 16, 2020; Azami, “Afghanistan: How does the Taliban make money?”

[41] Mashal.

[42] Shawn Snow, “US weapons complicate Afghan war,” Military Times, July 25, 2017; Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Jawad Sukhanyar, “The Taliban Have Gone High-Tech. That Poses a Dilemma for the U.S.,” New York Times, April 1, 2018; Kyle Rempfer, “Taliban’s use of US weapons muddled two death inquiries in Afghanistan,” Army Times, July 2, 2020; Austin Bodetti, “How the US Is Indirectly Arming the Taliban: Much of the Taliban’s armory comes from American equipment given to the Afghan military and police,” Diplomat, June 13, 2018; Miles Vining and Ali Richter, “Night vision devices used by Taliban forces,” Armored Research Services, April 29, 2018.

[43] Franz J. Marty, “Fire From the Sky: The Afghan Taliban’s Drones,” Diplomat, December 22, 2020; Ruchi Kumar and Ajmal Omari, “Taliban Adopting Drone Warfare to Bolster Attacks,” National, January 4, 2021.

[44] “Justification for FY 2021 Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) Afghanistan Security Forces Fund;” OSD, “Justification for FY 2020 Overseas Contingency Operations Afghanistan Security Forces Fund,” March 2019.

[45] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 30, 2020, pp. 94-95, 97; Thomas, p. 9.

[46] “Justification for FY 2021 Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) Afghanistan Security Forces Fund,” p. 12.

[47] Ibid., p. 10.

[48] “Some Improvements Reported in Afghan Forces’ Capabilities, but Actions Needed to Enhance DOD Oversight of U.S.- Purchased Equipment,” GAO-19-116, U.S. Government Accountability Office, October 2018, pp. 5-6; Tamim Asey, “The Fiscally Unsustainable Path of the Afghan Military and Security Services,” Global Security Review, June 7, 2019; author discussions with U.S. and Afghan government officials, 2013-2020.

[49] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020.

[50] Jones; Mir, p. 8; Abdul Sayed, “The Future of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and Pakistan,” Center for Global Policy, December 17, 2020; Susannah George, “Behind the Taliban’s Ties to al-Qaeda: A Shared Ideology and Decades of Battlefield Support,” Washington Post, December 8, 2020.

[51] “Eleventh Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” pp. 11-12.

[52] Mashal; Devin Lurie, “The Haqqani Network: The Shadow Group Supporting the Taliban’s Operations,” American Security Project, September 2020.

[53] “Sources of funding (including self-funding) for the major groupings that perpetrate IED incidents –Taliban;” Jones; Jeff Schogol, “Iran Supports the Taliban with Weapons, Training, and Money, Pentagon Report Says,” Task & Purpose, November 19, 2019; Ahmad Majidyar, “Afghan Intelligence Chief Warns Iran and Russia Against Aiding Taliban,” Middle East Institute, February 5, 2018.

[54] Farrell, p. 71; Jones; Justin Rowlatt, “Russia ‘Arming the Afghan Taliban’, Says US,” BBC, March 23, 2018; Nick Paton Walsh and Masoud Popalzai, “Videos Suggest Russian Government May be Arming Taliban,” CNN, July 26, 2017; Majidyar; Andrew Wilder, “U.S., Russian Interests Overlap in Afghanistan. So, Why Offer Bounties to the Taliban?” United States Institute of Peace, July 7, 2020.

[56] Jones.

[57] Steve Coll, Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 2001–2016 (New York: Random House, 2018), pp. 329-340.

[58] Matt Waldman, “The Sun in the Sky: The Relationship Between Pakistan’s ISI and Afghan Insurgents,” Harvard University Discussion Paper 18, June 2010; Farrell, p. 72; “Sources of funding (including self-funding) for the major groupings that perpetrate IED incidents –Taliban.”

[59] Mohammad Haroon Alim, “Former DG ISI, Reveals Secrete [sic] Links with Taliban,” Khaama Press News Agency, December 2, 2020.

[60] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, pp. 3-4.

[61] Schroden et al., Independent Assessment of the Afghan National Security Forces, pp. 43-79.

[62] “Sources of funding (including self-funding) for the major groupings that perpetrate IED incidents –Taliban;” Majidyar.

[63] Farrell, p. 64; Borhan Osman and Fazl Rahman Muzhary, “Jihadi Commuters: How the Taleban cross the Durand Line,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, October 17, 2017.

[64] Schroden et al., Independent Assessment of the Afghan National Security Forces, pp. 43-79.

[65] Alec Worsnop, “From Guerrilla to Maneuver Warfare: A Look at the Taliban’s Growing Combat Capability,” Modern War Institute, June 6, 2018; Antonio Giustozzi, “The Military Cohesion of the Taliban,” Center for Research Policy Analysis, July 14, 2017; Farrell, p. 71.

[66] Ibid.; Jones.

[67] Obaid Ali and Thomas Ruttig, “Taleban Attacks on Kunduz and Pul-e Khumri: Symbolic Operations,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, September 11, 2019; Fazl Rahman Muzhary, “Unheeded Warnings (1): Looking Back at the Taleban Attack on Ghazni,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, December 16, 2018; “Tenth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” p. 7.

[68] Ibid.; Jones; Christopher Woody, “A New Taliban Tactic is Racking up a Huge Body Count in Afghanistan,” Business Insider, October 19, 2017.

[69] William Rosenau and Megan Katt, “Silent War: Taliban Intelligence Activities, Parallel Governance, and Propaganda in Helmand Province,” CNA CRM D0025094.A1/Final, May 2011; Hollie McKay, “How the Taliban Remained Dominant in Afghanistan: Terrifying Tactics and an Advancing Weapons Arsenal,” Fox News, August 6, 2019.

[70] “Tenth Report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” p. 7; Giustozzi, “Afghanistan: Taliban’s Organization and Structure,” p. 18; Jones.

[71] Thomas H. Johnson, Taliban Narratives: The Use and Power of Stories in the Afghanistan Conflict (London: Hurst, 2017), Giustozzi, “Afghanistan: Taliban’s Organization and Structure,” p. 19; Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Najim Rahim, “To Disrupt Elections, Taliban Turn to an Old Tactic: Destroying Cell Towers,” New York Times, October 2, 2019.

[72] See references in the material resources section on the Taliban.

[73] Giustozzi, The Taliban at War, chapter 4.

[74] Snow; Gibbons-Neff and Sukhanyar; Rempfer; Bodetti.

[75] James Clark, “An Emboldened Taliban Nearly ‘Wiped Out’ an Entire Afghan Army Unit Using Lethal New Tactics,” Task & Purpose, October 19, 2017; Woody.

[76] Rahmatullah Amiri, “Helmand (2): The Chain of Chiefdoms Unravels,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, March 11, 2016; Mirwais Khan and Lynne O’Donnell, “Taliban’s New Commando Force Tests Afghan Army’s Strength,” Associated Press, August 6, 2016; Bill Roggio, “Taliban Touts More Elite ‘Red Unit’ Fighter Training on Social Media,” FDD’s Long War Journal, April 8, 2020; “Everything You Need to Know About the Taliban’s Special Forces Unit,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 13, 2018.

[77] Schroden et al., Independent Assessment of the Afghan National Security Forces, pp. 83-159.

[78] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, p. 30.

[80] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” October 30, 2020, p. 90.

[81] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, p. 33; Schroden et al., Independent Assessment of the Afghan National Security Forces, pp. 147-159; John W. Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces – Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” February 2017, pp. 11-12.

[82] Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces – Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” p. 12.

[83] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, pp. 31-32.

[84] Castillo, p. 18.

[85] Ibid., p. 34.

[87] Giustozzi, “Afghanistan: Taliban’s Organization and Structure,” pp. 21-23; Watkins, p. 13; Jones; Amiri.

[88] Castillo, p. 34.

[89] Ibid.

[90] For a good history of this, see Watkins.

[91] Anand Gopal, “Serious Leadership Rifts Emerge in Afghan Taliban,” CTC Sentinel 5:11 (2012): p. 9.

[92] Giustozzi, “Afghanistan: Taliban’s Organization and Structure,” pp. 21-23.

[93] Farrell, p. 75.

[94] Watkins; Mir; Giustozzi, “The Military Cohesion of the Taliban.”

[95] Mir, p. 12; Watkins, pp. 7, 13; “Taking Stock of the Taliban’s Perspectives on Peace,” p. 8; Giustozzi, “The Military Cohesion of the Taliban.”

[96] Mir, p. 12; Mullah Fazl, unreleased audio recording, March 25, 2020; “Message of Felicitation of the Esteemed Amir-ul-Mumineen Sheikh-ul-Hadith Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada (may Allah protect him) on the Occasion of Eid-ul-Fitr,” Voice of Jihad, May 20, 2020; Ashley Jackson and Rahmatullah Amiri, “Insurgent Bureaucracy: How the Taliban Makes Policy,” Peaceworks 153, United States Institute of Peace, November 2019; Borhan Osman, “Rallying Around the White Flag: Taleban embrace an assertive identity,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, February 1 ,2017.

[97] Mir, p. 12; Giustozzi, “The Military Cohesion of the Taliban.”

[98] Watkins, p. 12 as well as the discussion in the material resources section on the Taliban.

[99] Castillo, p. 34.

[100] Ibid.

[101] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, pp. 31-32.

[103] Muzhary; W.J. Hennigan, “Exclusive: Inside the U.S. Fight to Save Ghazni From the Taliban,” Time, August 23, 2018.

[104] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 30, 2020, p. 36.

[105] Ibid., pp. 36-37.

[106] Ibid.

[107] John W. Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces – Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” p. 11.

[108] Giustozzi, “Afghanistan: Taliban’s Organization and Structure,” p. 12.

[109] This assessment assumes that personnel in the fighting forces remain loyal to their respective sides.

[110] Asey.

[111] “Justification for FY 2021 Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) Afghanistan Security Forces Fund,” p. 10.

[113] Thomas, p. 15.

[114] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, p. 97.

[115] Ibid.

[116] Ibid., p. 45.

[117] “Justification for FY 2021 Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) Afghanistan Security Forces Fund,” p. 67.

[118] Ibid., p. 68.

[119] Ibid., p. 82.

[121] Jones.

[123] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, p. 38.

[124] Ibid.

[125] Ibid., p. 38.

[126] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), January 30, 2019, p. 43.

[127] Schroden et al., Independent Assessment of the Afghan National Security Forces, pp. 271-319.

[128] John W. Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces – Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” February 9, 2017.

[129] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” January 30, 2019, p. 43. Note that districts coded as “contested” often consist of the government controlling the district center and the Taliban controlling much of the rest of the district’s territory.

[130] “Addendum to SIGAR’s January 2018 Quarterly Report to the United States Congress,” SIGAR, January 30, 2018, p. 1.

[131] Schroden, “Military Pressure and Body Counts in Afghanistan.”

[132] Schroden, “Weighing the Costs of War and Peace in Afghanistan;” author discussions with individuals directly involved in negotiations with the Taliban.

[133] For a contrary view of the ANDSF, see Abdul Rahman Rahmani and Jason Criss Howk, “Afghan Security Forces Still Worth Supporting,” Military Times, August 29, 2019.

[134] See, for example, Farshad Saleh, “Only 30 percent of Kandahar police service members are on duty: Governor,” Ariana News, December 31, 2020.

[135] “Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan,” June 30, 2020, pp. 44, 46; John W. Nicholson, “Statement for the Record by General John W. Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces – Afghanistan Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Situation in Afghanistan,” pp. 2, 9, 11, and 16-17.

[136] “Military collapses quickly as probability of victory decreases.” See Castillo, pp. 19-20. A review of how the Taliban conquered Afghanistan in the mid-90s also reveals a significant “divide and assimilate” component of the group’s strategy, in which the Taliban negotiated the surrender or “flipping” of various other groups and factions in order to take control of areas without fighting. It is highly likely the group would again employ this approach against various elements of the ANDSF. See Jonathan Schroden et al., Independent Assessment of the Afghan National Security Forces, CNA DRM-2014-U-006815-Final, January 2014, pp. 271-319.

[137] For some suggestions on how to do this, see Asey as well as Jonathan Schroden, “Afghanistan Will Be the Biden Administration’s First Foreign Policy Crisis,” Lawfare, December 20, 2020.

Skip to content

Skip to content