Abstract: Ever since Boko Haram’s leader Abubakar Shekau pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in March 2015, the group has been seen as firmly in the Islamic State fold. But as both the Islamic State and Boko Haram weaken, al-Qa`ida, which has a history of cooperation with jihadis in Nigeria, including factions within Boko Haram, may be making a takeover bid.

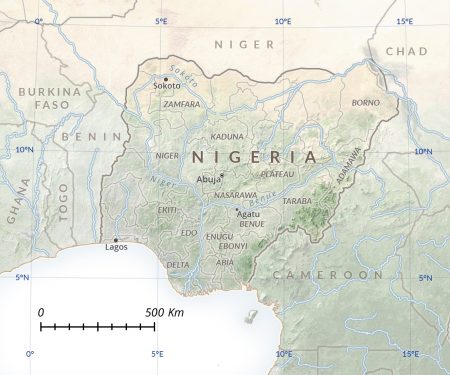

Initially formed as a Nigeria-centric, grassroots Islamist extremist organization,1 Boko Haram has evolved into a militant movement of transnationalist proportions. From a geographical perspective, the Islamist sect has expanded its footprint outside of its strongholds in northeastern Nigeria into the wider Lake Chad region.2 In doing so, Boko Haram is now seen as exerting an operational presence in Niger’s southeastern Diffa and Zinder regions, Cameroon’s Extreme-North (Far North) province, and the Lac Region of Chad where it continues to launch attacks against both state and civilian interests. Further reinforcing its status as a transnationalist terrorist organization was the March 2015 pledge of allegiance by Boko Haram’s leader, Abubakar Shekau, to the so-called Islamic State in the Levant’s caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.3 In doing so, Boko Haram, renamed Wilayat West Africa, became the Islamic State’s most well-known and deadliest wing,a with the sect’s dawlahb—an ‘Islamic’ province declared by Shekau in northeastern Nigeria—briefly serving as the largest contiguous area of Islamic State-held territoryc outside of the Levant.

But while investigations are ongoing to uncover the extent of Boko Haram’s relationship with the Islamic State—and whether any operational and/or logistical contiguity exists between the two groups—research on the Nigerian sect’s relationship with the al-Qa`ida transnationalist network has been limited. Using the significant groundwork laid by Jacob Zenn and other scholars, including in this publication,4 this article seeks to piece together a chronological narrative of Boko Haram’s opaque linkages with al-Qa`ida and why this relationship could endure beyond the Nigerian sect’s association with the Islamic State.

Al-Qa`ida, bin Ladin, and Muhammad Yusuf

Al-Qa`ida’s linkages to Boko Haram can be traced to the latter’s very beginnings. It is claimed that the sect’s founding leader, Muhammad Yusuf5—a Maiduguri-born Islamic scholar who gained popularity through his widely disseminated sermons—was an ardent admirer of Usama bin Ladin6 and may have been inspired by the al-Qa`ida leader in forming Boko Haram. There has even been speculation that in 2000 bin Ladin had made available as much as $3 million in funding to Islamist political organizations in Nigeria and that some of these funds were allocated to Yusuf and his then-fledgling movement.7 Yusuf is said to have used these funds, which were eventually distributed following two separate audio messages by bin Ladin in 2002 calling on Nigerian Muslims to wage jihad, to establish a micro-lending scheme for his followers.8

Although evidence of bin Ladin’s financial assistance to Yusuf is not definitive, the micro-lending plan the al-Qa`ida leader is purported to have facilitated served as one of Boko Haram’s most important revenue-generating mechanisms in its near decade-long insurgency against the Nigerian state and its regional allies.9

Shekau Courts al-Qa`ida

With Yusuf’s killing during the so-called Maiduguri Uprisingd in July 2009, the leadership reins of Boko Haram were transferred to Shekau. Amid an intensive crackdown on the sect by the Nigerian state security apparatus, it was suggested that Shekau had reached out to al-Qa`ida for assistance. Evidence of this was disclosed earlier this year by the United States’ Office of Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), which declassified a portion of the documents recovered during the May 2011 raid on bin Ladin’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan.10

Among the cache of documents were letters between Abdelhamid Abou Zeid, a former commander of al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) who was killed northern Mali in 2013, and the leader of al-Qa`ida’s North Africa branch, Abdelmalek Droukdel.11 In one of the exchanges authored in August 2009, Abou Zeid details how Shekau deployed a three-member group to establish ties and communication between himself and Droukdel.12 Shekau’s chosen emissaries, which included Boko Haram members Abu Muhammad Amir al-Masir, Khalid al-Barnawi, and Abu Rayhanah, were allegedly selected because Abou Zeid knew them from their time in the ranks of the AQIM-affiliated Tariq Ibn Ziyad Battalion.13 In addition to connecting its leadership to that of AQIM, Boko Haram also requested assistance with funding, training, and expertise, such as bomb making and waging a tactical asymmetric armed campaign.e In March 2016, ODNI also declassified another undated letter from the bin Ladin cache that was written by Shekau himself and addressed to al-Qa`ida leadership. In it, the Boko Haram emir requested to speak with bin Ladin’s then deputy and current leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and also sought instruction on how his movement could form part of al-Qa`ida’s transnationalist network.14

While there is currently no evidence confirming whether bin Ladin ever responded to Shekau’s requests, AQIM confirmed that Droukdel had established contact with Shekau around 2009 as per a series of letters AQIM made public in April 2017. These communiqués detailed how Droukdel welcomed the idea of forging a relationship between AQIM and Boko Haram and even pledged to assist the latter with its training and financing. It cannot be said for certain whether links between the two groups were formally solidified. Notably, Shekau never swore fidelity to either bin Ladin or al-Zahwari—a pledge that would have facilitated Boko Haram’s transition to an al-Qa`ida franchise and the provision of training and resources. However, there are suggestions that Boko Haram may have received some form of operational and technical assistance from al-Qa`ida. This was highlighted in August 2011 when a Boko Haram suicide bomber drove his explosive-laden vehicle into the offices of the United Nations building in the Garki district of Abuja, killing 23 people and wounding 76 others.15 Nigeria’s Department of State Services (DSS) later claimed the car bombing was planned by Boko Haram commander Mamman Nur, who masterminded bomb making while training in Somalia alongside al-Qa`ida’s largest African affiliate, al-Shabaab.16 The Abuja attack may have marked the first instance of an alleged transference of operational expertise from an Africa-based al-Qa`ida affiliate to jihadis in Nigeria. However, it would certainly not be the last.

Boko Haram’s Ties to al-Qa`ida in Mali

While Nur’s connections to al-Qa`ida have not been definitively proven, links between the sect and the transnationalist extremist movement became clearer a year later. Coinciding with the March 2012 military coup in Mali, a security vacuum in the country’s separatist north was rapidly filling with a variety of Islamist extremist movements.17 According to a briefing issued at the time by Malian local deputy governor Abu Sidibe,18 Boko Haram was one of the Islamist groups to occupy the region.19 Sidibe claimed that an estimated 100 Boko Haram militants had infiltrated Mali’s Gao administrative division and aided insurgents of the al-Qa`ida-linked Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO)f in securing control of the territory.20 Malian officials also cited Boko Haram’s involvement in the April 2012 abduction of seven diplomats from the Algerian consulate in Gao.21

Claims of a Boko Haram presence in northern Mali were also given credence by then French Minister of Foreign Affairs Laurent Fabius. Addressing a conference focusing on security challenges in Mali and the Sahel in November 2013, Fabius claimed that his military had acquired documentary evidence detailing the training of Boko Haram militants within northern Mali.22 These camps, which were located in the Adrar des Ifoghas mountain range near the Algerian border, were believed to have been operated by AQIM.23 Months later, Boko Haram was also added to the United Nations Security Council’s Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee’s sanctions list.24 One of the factors that led to the sect’s designation was findings confirming that Boko Haram “maintained a relationship with” AQIM “for training and material support purposes.”25 In a press release, the committee also affirmed that a “number of Boko Haram members fought alongside Al-Qaida affiliated groups in Mali in 2012 and 2013 before returning to Nigeria with terrorist expertise.”26

Al-Qa`ida’s Nigerian Proxy

Amid suggestions of synergies between Nigerian Islamists and al-Qa`ida in Malian territory, evidence of a symbiotic relationship between the two groups was also emerging within Nigerian borders. Days before the March 2012 Malian coup, a British national, Chris McManus, and an Italian, Franco Lamolinara, were executed by their kidnappers in the northwestern Nigerian town of Sokoto during a failed joint rescue operation by the British and Nigerian militaries.27 The pair was initially seized in the town of Birnin Kebbi in May 2011 by militants who identified themselves as al-Qa`ida in the Lands Beyond the Sahel.28 A similar fate would befall German engineer, Edgar Raupach, who was seized from the city of Kano, Nigeria, in January 2012.29 While no group specifically claimed Raupach’s kidnapping, the terms for the release for the German hostage were set by AQIM. The terrorist group demanded the release of Felize Gelowicz—a German woman convicted on charges related to her husband’s intent to conduct terrorist attacks on German soil—in exchange for the incarcerated engineer.30 In a grim echo of the McManus and Lamolinara case, Raupach was executed by his captors in Kano in May 2012 amid suspicions that a rescue operation had been launched to secure his release.31

Although the identities of the perpetrators of both the Birnin Kebbi and Kano abductions were initially obscure, Nigerian security forces believed that they were members of Boko Haram.32 Researchers focusing on Boko Haram, such as Jacob Zenn, speculated that al-Qaeda in the Lands Beyond the Sahel may have been a Boko Haram33 offshoot that later became known as Jama’at Ansar al-Muslimin fi Bilad al-Sudan, or Ansaru. Announcing its formation in the city of Kano in February 2012, Ansaru derided Shekau’s leadership of the main sect as ‘un-Islamic’ and chastised him both for his gratuitous violence and killing of Muslim civilians.34 At the time of its creation and as initially hypothesized by Zenn in this publication, Ansaru was believed to be led by senior members of Boko Haram’s governing body, or Shura Council, most notably Khalid al-Barnawi who had fallen out with Shekau over his leadership style and his envisioned trajectory for the movement.35

In pledging to limit its insurgent activities to Christian, state, and foreign interests36—as Droukdel himself had publicly instructed his AQIM members to do37—Ansaru employed a pan-West African narrative similar to the one employed by al-Qa`ida’s African affiliates.38 However, similarities between Ansaru and al-Qa`ida were not only limited to rhetoric. As noted by Zenn, apart from incorporating AQIM symbolism within its branding—denoted by Ansaru’s use of the ‘setting sun’ logo, which was seemingly borrowed from AQIM’s predecessor, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) of which Droukdel and al-Barnawi were members—the militant group also demonstrated operational contiguity with al-Qa`ida’s North African branch.39 Notably, Ansaru continued to target western expatriates in kidnappings in northern Nigeria that were carried out with the same surgical precision as that of AQIM and its affiliates in the Sahel. The most notable of these was the kidnapping and subsequent execution of seven expatriate workers from a construction site in the town of Jama’are in Bauchi state in February 2013.40 Following his arrest in the Lokoja area of Kogi State in April 2016, Khalid al-Barnawi was charged with the kidnapping and murder of 10 foreign nationals in Nigeria, including that of McManus, Lamolinara, Raupach, and the seven victims of the Jama’are attack.41 In this regard, al-Barnawi’s indictment tied him both to kidnappings claimed by Ansaru and those committed by assailants defining themselves as members of al-Qa`ida, making clear the overlap between the organizations.

Further demonstrating its purported ties to AQIM, Ansaru also claimed responsibility for the January 2013 ambush of a Nigerian military convoy in Kogi State.42 At the time of the attack, the convoy was en route to Mali where it was set to serve as part of an African Union peacekeeping mission mandated to target al-Qa`ida positions in the country’s desert north.43 Evidence of Ansaru’s establishment as a possible al-Qa`ida proxy was further strengthened in 2013 with a complex attack in neighboring Niger. On May 23 that year, two simultaneous militant incursions took place at a military base and French-operated uranium mine in the respective Nigerien towns of Agadez and Arlit.44 The attacks, which killed 36 people, was claimed by MUJAO in accordance with the Signatories in the Blood brigade led by infamous al-Qa`ida commander Mokhtar Belmokhtar, in what it called a reprisal for French interference in Mali. In a pre-recorded video, one of the future attackers identified himself as Abu Ali al-Nigiri and also revealed his membership in Ansaru.g Al-Nigiri was killed during the incursions, along with all other militants who took part in the Arlit and Agadez incursions.45 His death coincided with Ansaru’s cessation in launching and claiming attacks.

Ansaru’s Dormancy

Following intensive counterterrorism operations in Mali, there was speculation that Ansaru’s Malian-based patronage network had collapsed.46 Within Nigeria, Ansaru was also facing increasing crackdowns by both the military and Shekau loyalists. These conditions may have prompted Ansaru’s leadership to seek rapprochement with Shekau.47 This hypothesis was reinforced by Boko Haram’s November 2013 kidnapping of a French priest near the Nigerian border in northern Cameroon. In claiming the kidnapping, Boko Haram noted that the abduction was carried out with the assistance of Ansaru, suggesting that some form of cooperation between the factions was taking place.48

Following the incident, the only other evidence of Ansaru’s independence from and opposition to Boko Haram was noted in a January 2015 video release in which two self-proclaimed Ansaru members again distanced the group from Boko Haram and its armed violence against Muslim civilians.49 Ansaru’s operational dormancy as an entity also apparently brought to an end connections between the Nigerian sect and al-Qa`ida, with the former eventually drifting toward the orbit50 of the Islamic State, to which it eventually pledged allegiance in March 2015.

Al-Qa`ida Takeover Bid?

Ansaru’s, and by extension al-Qa`ida’s, dormancy within Nigeria’s jihadi theater ended, however, in January 2017. In the fourth edition of al-Qa`ida-aligned Al Risalah magazine,h an essay entitled “A Message to Nigeria” was dedicated to tracing the origins and evaluating the current state of jihad in the West African country.51 Authored by Sheikh Abu Usamatul Ansary—the self-professed emir of Ansarui—the entry also includes important references to how and why Ansaru was created. Ansary wrote that Ansaru had been established in consultation with “our Algerian brothers in the Sahara,” a reference that appears to reinforce Ansaru’s ties to Droukdel and the wider AQIM fraternity.52 Al-Ansary also ascribes Ansaru’s formation to Shekau’s penchant for gratuitous violence against Muslim civilians, his inability to handle criticism, and most significantly, his un-Islamic actions.53 The fact that the article was published in an al-Qa`ida-aligned magazine made clear the reconstituted Ansaru group as led by Ansary regarded itself as part of the al-Qa`ida fold.

Interestingly, al-Ansary’s critique of Shekau was almost identical to that made by Abu Musab al-Barnawi (the Islamic State recognized emir of its Nigerian wing)54 j and his closest known associate, Mamman Nur55 in an audio tape released on August 5, 2016. Both al-Barnawi and Nur have split from Shekau and are believed to lead Wilayat West Africa (ISWAP).56 This raised the possibility that the new Ansaru emir was trying to lay the groundwork for this affiliate to switch its allegiance to al-Qa`ida.

Apart from sharing distaste for Shekau and severing ties with his movement, there have been a number of other shared characteristics between the al-Qa`ida-aligned Ansaru and the Islamic State-loyal ISWAP over the years. Both groups favor the targeting of state and foreign interestsk while sparing Muslim civilians and are seemingly adept at kidnapping operations.57 The leadership structures of both movements appear to be less Nigeria-centric,58 while the geographic area of focus is also not constrained to Nigeria’s borders.59

With al-Qa`ida seemingly strengthening its presence in West and North Africa—as noted by its geographical expansion across the region60 and the consolidation of its many affiliates into the Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin’ (JNIM)l—it is plausible that the recent chapter in Al Risalah dedicated to jihad in Nigeria was an attempt by al-Qa`ida-aligned jihadis to court al-Barnawi and Nur’s ISWAP faction to bring them back into the al-Qa`ida fold.

The article was published at a time when the Islamic State’s relative strength and influence appears to be waning in Africa as highlighted by its loss of territory along the Libyan coastlinem and the severe pressure its affiliates are under in the wider Maghreb. In both Nigeria and the wider West African region, the jihadi landscape remains both dynamic and fluid with allegiances broken as often as they are being made.

Conclusion

In its near decade-long insurgency, Boko Haram has evolved from a Nigerian-centric grassroots Islamist extremist organization to an affiliate of the Islamic State with an operational footprint spanning an entire region. Throughout Boko Haram’s many transitional phases, al-Qa`ida has been in the foreground, assuming the purported roles of financier, interlocutor, and even divider of Nigerian jihadi groups as illustrated by the origin story of Ansaru.

The immediate question is the role that al-Qa`ida might assume in the next chapter of Nigerian jihadism, particularly in a context where the transnationalist network is strengthening its position in West Africa and where its ideological rival and Boko Haram’s patron, the Islamic State, has found it difficult to fulfill its axiom of “remaining and expanding.”n Given Nigeria is home to Africa’s largest Muslim population; has social, political, and economic cleavages, which could readily be exploited; and is located not far from al-Qa`ida’s strongholds in northern Mali, the country will likely be seen as a prime area of infiltration for al-Qa`ida. With Boko Haram also on the backfoot,61 it could be incentivized to seek a patron with a more promising trajectory. Al-Qa`ida has a proven track record of developing and working with affiliates62 and already has deep ties to jihadis in Nigeria. CTC

Ryan Cummings is the director of the political and security risk management consultancy Signal Risk. He is also a founding member of the Nigerian Security Network whose analysis has been featured by The New York Times, TIME, Al Jazeera, and Deutsche Welle. He is a contributor to the Tony Blair Foundation and the International Peace Institute on issues of terrorism, conflict, and political instability. Follow @pol_sec_analyst

Substantive Notes

[a] In 2016, the Institute of Economics and Peace ranked Boko Haram as the deadliest Islamist extremist group in its annual Global Terrorism Index (GTI) report. Boko Haram accounted for more cumulative fatalities in 2015 than any other Islamist extremist movement, overtaking the Islamic State itself. See “Global Terrorism Index 2016,” Institute for Economics and Peace, November 2016.

[b] In August 2014, Shekau released a video in which he announced the Borno State town of Gwoza as the capital of a swath of territory in Nigeria’s northeastern Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states. Many reports suggested that Shekau had declared a caliphate; however, the Arabic term used by Shekau to describe this territory under Boko Haram’s command was dawlah, which can be translated to mean ‘state.’ For further reading on this, see Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, “Boko Haram Did Not Declare A Caliphate,” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, September 4, 2014.

[c] At the time of Shekau’s bay`a (pledge of allegiance) to al-Baghdadi in March 2015, Boko Haram had exerted some form of control over parts of Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states despite the Nigerian army and the partnered militaries of the Cameroon, Chad, and Niger launching a multi-pronged offensive against the sect as of February 2015. These counterinsurgency operations continued for several months, and only in October 2015 did the Nigerian government claim to have liberated all territory that had previously fallen under the sect’s control. At the time of its March 2015 bay`a, Boko Haram still exerted control over the town of Gwoza and at least three local government areas, namely that of Abadam, Kala-Balge, and Gwoza, which cumulatively comprised a total land area of more than 8,000 square kilometers, larger than the total area controlled by the Islamic state in Libya at the time.

[d] The Maiduguri Uprising refers to the events that unfolded July 26-29, 2009, when a police shooting of a group of Boko Haram members attending a funeral of a fellow member led to an outbreak of retaliatory violence in various regions in northeastern Nigeria. At the time of the clashes, Yusuf was remanded into police custody in Maiduguri where he was subjected to an extrajudicial killing. “Boko Haram attacks – timeline,” Guardian, September 25, 2012.

[e] Headed by Algerian national Abdul Hamid Abu Zayd, the Tariq Ibn Ziyad Battalion is considered as one of AQIM’s most radical affiliates and has perpetrated a number of kidnappings targeting foreign expatriates.

[f] The Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) was formed as a splinter faction of AQIM following the kidnapping of thee humanitarian aid workers from a refugee camp in Tindouf, Algeria, in October 2011.

[g] In the 51-minute video, which was released following the Agadez and Arlit attacks, a MUJAO militant identifies himself as Abu Ali al-Nigiri at approximately 30 minutes and 34 seconds. He then proceeds to state that he is a member of Jama’at Ansar al-Muslimin fi Bilad al-Sudan (Ansaru) from Nigeria.

[h] First published in July 2015, Al Risalah is an English-language magazine published by the al-Qa`ida-aligned Syrian extremist group Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra). Al Risalah is geared toward a Western, English-speaking audience and is a direct response to the Islamic State’s multilingual publication, Dabiq, which has been used as an effective propaganda mechanism by the group. To date, only four editions of Al Risalah have been published, along with a separate special edition of the publication that featured an exclusive interview with AQIM commander Shaykh al-Mujahid Hisham Abu Akram.

[i] While many analysts and media outlets speculated that Khalid al-Barnawi was the emir of Ansaru, the fourth issue of Al Risalah confirms that the movement remains led by Sheikh Abu Usamatul Ansary, despite claims that he was either killed in 2013 or that his moniker is merely a pseudonym used by al-Barnawi himself. The latter hypothesis is disputed by Ansary himself, who references al-Barnawi’s attempted assassination at the order of Shekau and his arrest and ongoing detention by Nigerian services in his essay.

[j] Abu Musab al-Barnawi is the son of Muhammed Yusuf. Musab al-Barnawi has no known family relationship to Khalid al-Barnawi. “Al-Barnawi” is a geographical kunya, suggesting both are from Nigeria’s Borno State. On August 2, the Islamic State formally named Abu Musab al-Barnawi as the wali, or governor, of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP)—the name adopted by Boko Haram after Shekau pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi—in its Al Naba publication. Shekau responded to al-Barnawi’s appointment as ISWAP’s leader by releasing an audio message affirming that he remains in charge of the movement. Both al-Barnawi and Nur responded to Shekau’s audio message with a communiqué of their own in which Shekau is chastised for his “false ideology.” For further reading, see “Boko Haram’s Shekau, group’s new leader, al-Barnawi, in war of words,” Premium Times, August 5, 2016.

[k] In the first videos released by both Ansaru and ISWAP announcing their respective formations, both groups emphasize the objectives of protecting Muslim civilians against the Nigerian state and its foreign allies. Both groups also stress the important of sparing civilians’ lives when waging jihad.

[l] Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin’ (JNIM) is an al-Qa`ida militant group formed on March 2, 2017, out of the merger between AQIM and the Islamist extremist affiliate groups of al-Mourabitoun, Ansar Dine, and the Macina Liberation Front. For an in-depth profile on the group, see Héni Nsaibia, “Jihadist Groups In The Sahel Region Formalize Merger,” Jihadology, March 27, 2017.

[m] After controlling an estimated 120-mile stretch of coastal territory at the height of its insurgency in Libya, the Islamic State lost its final stronghold of Sirte to an offensive spearheaded by Libya’s Government of National Accord and allied militias. While the group continues to operate within Libyan territory, it does so as a significantly weakened enterprise. For further reading, see Patrick Wintour, “Isis loses control of Libyan city of Sirte,” Guardian, December 5, 2016.

[n] The slogan Baqiya wa tatamaddad (remaining and expanding) was adopted as the official slogan of the Islamic State following its use in a speech by former spokesman Abu Muhamad al-Adnani in June 2014.

Citations

[1] Marc-Antonie Pérouse de Montclos, “Boko Haram and Politics: From Insurgency to Terrorism” in Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos (ed.) Boko Haram: Islamism, Politics, Security and the State in Nigeria (Leiden, Netherlands: African Studies Centre, 2014), p. 7.

[2] Ryan Cummings, “Has Boko Haram become more than Nigeria’s problem?” African Arguments, April 3, 2014.

[3] Rukmini Callimachi, “Boko Haram Generates Uncertainty With Pledge of Allegiance to Islamic State,” New York Times, March 7, 2015.

[4] See, for example, Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram’s International Connections,” CTC Sentinel 6:1 (2013); Jacob Zenn, “Leadership Analysis of Boko Haram and Ansaru in Nigeria,” CTC Sentinel 7:2 (2014); Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram: Recruitment, Financing, and Arms Trafficking in the Lake Chad Region,” CTC Sentinel 7:10 (2014); Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram and the Kidnapping of the Chibok Schoolgirls,” CTC Sentinel 7:5 (2014); Jacob Zenn, “A Biography of Boko Haram and the Bay`a to al-Baghdadi,” CTC Sentinel 8:3 (2015); and Jacob Zenn, “Wilayat West Africa Reboots for the Caliphate,” CTC Sentinel 8:8 (2015).

[5] Andrea Brigaglia, “Ja‘far Mahmoud Adam, Mohammed Yusuf, and Al-Muntada, “Islamic Trust: Reflections on the Genesis of the Boko Haram phenomenon in Nigeria,” Annual Review of Islam in Africa 11 (2012).

[6] Zenn, “A Biography of Boko Haram and the Bay`a to Al-Baghdadi.”

[7] “Curbing Violence in Nigeria (II): The Boko Haram Insurgency,” International Crisis Group Africa Report 216 (2014).

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Motivations And Empty Promises: Voices of Former Boko Haram Combatants and Nigerian Youth,” MercyCorps, April 2016.

[10] Thomas Joscelyn, “Osama bin Laden’s files: AQIM commander recommended training Boko Haram’s members,” FDD’s Long War Journal, February 18, 2017.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Thomas Joscelyn, “Osama Bin Laden’s Files: Boko Haram’s leader wanted to be ‘under one banner,’” FDD’s Long War Journal, March 4, 2016; “Praise be to God the Lord of all worlds,” Bin Laden’s Bookshelf, Department of National Intelligence, March 1, 2016.

[15] “Abuja attack: Car bomb hits Nigeria UN building,” BBC, March 27, 2011; Jacob Zenn, “Demystifying al-Qaida in Nigeria: Cases from Boko Haram’s Founding, Launch of Jihad and Suicide Bombings,” Perspectives on Terrorism 11:6 (2017); Shaykh Abu al-Hasan Rashid, “Shari’ah Advice and Guidance For the Mujahidin of Nigeria,” April 28, 2017. This section was updated several hours after publication with information that recently emerged indicating Droukdel had made contact with Shekau.

[16] “UN House Bomb Blast: DSS Declares Al Qaeda-linked Man, Mamman Nur, Wanted,” Sahara Reporters, August 31, 2011.

[17] “Timeline: Mali coup led to split, northern Islamist haven,” Reuters, September 27, 2012.

[18] “Boko Haram extends campaign to troubled Mali,” Channels TV, April 9, 2012.

[19] “Mali: islamistes de Boko Haram à Gao,” Figaro, April 9, 2012.

[20] “Terrorism profiles: Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa,” The Mackenzie Institute, January 18, 2016.

[21] “Dozens of Boko Haram Help Mali’s Rebel Seize Gao,” Vanguard, April 9, 2012.

[22] Ayobami Olopade, “Mali is Boko Haram’s training ground – French foreign minister,” The Scoop, November 15, 2013.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Boko Haram to Its Sanctions List,” United Nations, May 22, 2014.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] British hostage murder: timeline of how the kidnap of Chris McManus and Franco Lamolinara by al-Qaeda unfolded,” Telegraph, March 8, 2012.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “Germany confirms citizen kidnapped in Nigeria,” Reuters, January 27, 2012.

[30] “German engineer kidnapped in Nigeria killed during failed rescue attempt,” Associated Press, May 31, 2012.

[31] Ibid.

[32] “Nigeria’s militant Islamists adopting a disturbing change of tactics,” Guardian, March 8, 2012.

[33] “Expert interview: Jacob Zenn – On terrorism and insurgency in Northern Nigeria,” African Arguments, October 24, 2013.

[34] “Boko Haram: Splinter group, Ansaru emerges,” Vanguard, February 1, 2012.

[35] Zenn, “Leadership Analysis of Boko Haram and Ansaru in Nigeria.”

[36] Ibid.

[37] Sergei Boeke, “Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb: Terrorism, insurgency, or organized crime?” Small Wars & Insurgencies 27:5 (2016).

[38] Rafaello Pantucci and Sasha Jesperson, “From Boko Haram to Ansaru – The Evolution of Nigerian Jihad,” Royal United Services Institute, April 2015.

[39] Jacob Zenn, “Ansaru Logo Gives Hints to Boko Haram and Transnational Links,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 21, 2013.

[40] “Extremist Group in Nigeria Says It Killed 7 Foreign Hostages,” Associated Press, March 9, 2013.

[41] “Nigeria: Khalid al-Barnawi, leader of the Islamist group Ansaru, charged,” Sahel Standard, March 15, 2017.

[42] “Islamists Ansaru claim attack on Mali-bound Nigeria troops,” Reuters, January 20, 2013.

[43] Ibid.

[44] “Niger suicide bombers target Areva mine and barracks,” BBC, May 24, 2013.

[45] Bill Roggio, “MUJAO suicide bombers hit uranium mine, barracks in Niger,” FDD’s Long War Journal, May 23, 2013.

[46] Zenn, “Leadership Analysis of Boko Haram and Ansaru in Nigeria.”

[47] Ibid.

[48] “Boko Haram Holding Kidnapped French Priest,” Vanguard, November 15, 2013.

[49] “Jama’at Ansar al-Muslimin Fi Bilad al-Sudan: God Is Our Master,” Jihadology, January 29, 2015.

[50] Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram, Islamic State and the Archipelago Strategy,” Terrorism Monitor 12:24 (2014).

[51] Al Risalah Issue 4: The Balanced Nation, “A Message to Nigeria,” January 23, 2017.

[52] Al Risalah, Issue 4.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Yinka Ajayi, “What we know about Boko Haram’s new leader, Abu Musab al-Barnawi,” Vanguard, August 7, 2016.

[55] Jacob Zenn “Making sense of Boko Haram’s different factions: Who, how and why?” African Arguments, September 20, 2016.

[56] “Boko Haram renames itself Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP) as militants launch new offensive against government forces,” Independent, April 26, 2015.

[57] John Campbell, “Kidnapping comes to Northern Nigeria,” Council on Foreign Relations, February 19, 2013.

[58] Zenn, “Making sense of Boko Haram’s different factions: Who, how and why?”

[59] Ryan Cummings, “Boko Haram: A regional solution required,” Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, May 1, 2015.

[60] Andrew Lebovich, “The Hotel Attacks and Militant Realignment in the Sahara-Sahel Region,” CTC Sentinel 9:1 (2016).

[61] “Boko Haram on the backfoot,” International Crisis Group Briefing 120, May 4, 2016.

[62] Daniel Byman, “Buddies or Burdens? Understanding the Al Qaeda Relationship with Its Affiliate Organizations,” Security Studies 23:3 (2014).

Skip to content

Skip to content