Abstract: The crowds that stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, represented an emerging trend in American far-right extremism. Although many disagreements and personality clashes continue to emerge within and among groups since the storming of the Capitol, there are increasing indications that the typically fractious world of the extreme far-right is becoming more unified toward an objective of overthrowing the country’s prevailing political and social order. This objective is sometimes referred to as accelerationism. It is capable of uniting a wide spectrum of ideologies; however, it is not an ideology in itself. The coalition of extreme far-right ideologies whose adherents stormed the Capitol is defined by its myriad weak ties, and by the growing importance of unaffiliated actors within it, all united by their shared acceptance of accelerationist tactics.

The extreme far-right has long been characterized by its internal fissures and in-fighting. This fragmentation comes naturally to such a complex assortment of constituent groups—from those with neo-Nazi and white supremacist tendencies to the full range of unlawful militias, those with male supremacist and “incel”a tendencies, Christian nationalists, conspiracy theorists, and more. Each element nurtures its own peculiar ideologies of anti-democratic and authoritarian values, its specific commitments to hierarchies and stratification of identity, its conspiracy theories, and its fantasies of utopian restoration. These frequently clash, and while similarities and overlaps abound, fragmentation and schism have been the norm rather than the exception. And indeed, prior attempts to unify groups across this disparate spectrum—most notably in the aspirationally named “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017—have failed. To the great advantage of efforts to combat it, the extreme right had remained a fractured and disorganized spectrum—until January 6, 2021.

On that date, the myriad ideologies, extremist cultures, and conspiracy theories converged as both organized militants and spontaneous rioters alike participated in the first mass action of an eclectic but increasingly unified extreme far-right scene.1 Since January 6, only a relatively small number of arrests have been made of individuals who are members of groups—as opposed to individuals with no formal affiliation.2 This is noteworthy, as it suggests that groups are becoming less important on the extremist fringe than the ideological positions they represent. There were clearly several highly coordinated, hardcore militant groups present at the U.S. Capitol on January 6—including unlawful militias like the Oath Keepers and the extreme far-right, street-fighting gang the Proud Boys.3 And there were also less organized movements present, including individuals affiliated with the QAnon conspiracy cult,4 which has no formal structure or leadership yet can claim a far larger membership5 than organized unlawful militia groups.6 However, the vast majority of those who swarmed the Capitol to stop the formal certification of President Biden’s election were not affiliated with any named extremist group.7

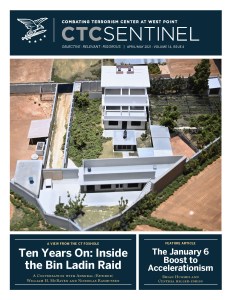

The events of January 6 reflected a growing trend across extremist milieus more broadly, in which previously fragmented groups and ideologies are coalescing around shared objectives related to the violent overthrow of the United States’ existing political and social order. These objectives reflect a growing belief on the extreme far-right that total collapse must precede any social or political project, if they ever hope to reorient society according to their preferred mode of hierarchic organization. As a belief, strategy, and tactic, this approach has come to be known as accelerationism. On January 6, the extreme far-right’s ability to come together in pursuit of a shared goal—to take the U.S. Capitol by force, interrupt the certification of the electoral college votes confirming Joe Biden as the incoming U.S. president, and arrest and/or execute liberal politicians—revealed how quickly consolidation can happen, driven by large-scale disinformation and calls to action from elected officials and group leaders.

The following article will detail key dynamics associated with a coalescing extreme far-right. In order to understand how a movement still prone to in-fightingb can also be increasingly unified, it is necessary to understand the nature of accelerationism. Accelerationism is a strategic orientation, not an ideology in itself. In fact, insofar as accelerationism addresses ideology, it is through the goal of dismantling prevailing norms of liberal democracy. In this way, accelerationism is uniquely capable of sidestepping the ideological and operational conflicts endemic to the extreme far-right. This operational alliance was seen in action during the events of January 6, when a variety of unaligned individuals as well as formal extreme far-right groups stormed the U.S. Capitol with the intent of overturning the constitutional transfer of presidential power. This article then goes on to describe the role of online communication technology, media, and cultural spaces in fostering a more ecumenical extreme far-right. Online networks are both looser and more extensive than those of earlier eras, creating an extremist milieu that is both decentralized and coordinated, and in which the distance between dedicated extremists and potential recruits is smaller than ever before. Of course, it is impossible to discuss the events of January 6 without an examination of the role played by Donald Trump. This article concludes with an assessment that Trump has been a key element in the evolution of this more united extreme far-right front. However, with Trump having left office and now lacking his platform on social media, the extreme far-right and accelerationist tendencies seem to have evolved past the need for Trump as a galvanizing figure.

Understanding Accelerationism: An Anti-Ideology

It is necessary to distinguish accelerationism from the many extreme far-right tendencies it presently serves to unite. Accelerationism is not an ideology in itself. Rather, it is an ideological style and a strategic method, meant to bring about the failure of the ideologies that prevail in any given system or country at this particular moment in time. In the United States, these systems include representative democracy with a strong federal government, putative equality under the law, free markets, internationalism, and a highly technological lifestyle in which commercial entertainment and consumption play important roles. Under accelerationism—as a goal and a tactic—individuals with disparate beliefs are united in the goal of hastening the cataclysmic end of economic, political, and social systems so as to more rapidly bring about what is seen as an inevitable end-times collapse and subsequent rebirth into a utopian afterworld.

Therefore, the question of what happens after systems collapse does not matter in accelerationism per se, even if most extreme-right tendencies do have a ‘utopian’ vision to follow the collapse. Within the anti-government fringe, ideologies such as the Oath Keepers’ paranoid anti-federalism envision a restoration of “self-government” and “natural rights” in a gauzy re-envisioning of the days of the U.S. founding—implicitly if not explicitly white and male dominated.8 For QAnon conspiracy theorists, the utopian future centers on “the Storm,” a preordained day of reckoning for satanic global leaders, in which mass arrests and execution of their political opponents will vindicate them in the public eye.9 To the ideologies most associated with the Trumpist base, this entails delivery of authoritarian power via mob violence to existing political figures such as former president Donald Trump.10 And for still others, it means the beginning of a race war, genocide, and Armageddon itself, followed by a rebirth into a “restored” white civilization.11

These are ‘utopian’ dreams specific to distinct extreme far-right ideologies. But they are not merely statements of political belief or moral value. As functions of ideology, they are “devices designed to bring about a fleeting—yet temporarily necessary—halt to [disagreement] by opting for one conceptual structure rather than another.”12 That is, they are social and strategic fantasies that aim to organize and direct large groups of people toward a shared goal. This is distinct from accelerationism proper, which has no aim beyond itself. As a strategy and style, accelerationism’s goal is nothing less than to destroy the dominant liberal-democratic order of the United States. It is agnostic as to what follows the “magic moment of ecstatic brotherhood”13 of insurrection and coup. It is an inter-tendency approach that happens to be compatible with the intra-tendency goals of those “militant networks, organized clusters, and inspired believers”14 who stormed the Capitol. Accelerationism is best understood as an anti-ideology, directed toward the destruction of the current ideological order and the political-economic system that expresses and creates that order. But in its anti-ideological thrust, accelerationism makes possible what had once been so difficult: to move the many varieties of extreme far-right tendencies in unison.

Accelerationism in Action at the U.S. Capitol

The events of January 6 represent an inflection point for this loose coalition. The storming of the Capitol reflected the climax of a years-long process of consolidation through new organizational tactics. The extreme far-right has increasingly abandoned “traditional organizing methods,” which it has determined are insecure and vulnerable to surveillance, infiltration, and prosecution.15 Instead, individuals and groups across the spectrum have relied on informal online networking,16 linked to calls for individual “lone actor”-style violent action through a torrent of messaging advocating for accelerationist insurrection and violence against the government, political opponents, and minority groups.17

In this loose network, ideology and tactics are crowd-sourced, and political violence is more typically valorized and rewarded than explicitly plotted. This arrangement has been compared to the style of leaderless resistance advocated by Louis Beam.18 c However, it is also unique to the age of networked digital communication. This new network of far-right extremism exhibits vastly more vectors of connection between its members than the extreme far-right leaderless resistance of the 20th century while simultaneously these connections are far weaker than those that animated the white power movement of the 1980s and 1990s.

The groups, individuals, and tendencies that circulate in accelerationist networks have been able to set aside the acrimony and infighting of the past, thanks to the loyalties that accompany these extensive, but loose, ties. They also share in the growing belief that the overthrow of the existing political and social order is the essential first step of any future agenda seeking to reshape the country. For now, any “Day 2” disagreements over the precise form of their remade America fade into the background of the more immediate desire for mass violence.

A comprehensive survey of all the groups and tendencies comprising this emerging American extremist front has yet to be conducted. However, information gleaned from the January 6 insurrection offers a sample of this population, which may be indicative of its broader make-up. “‘This is Our House!’: A Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill Siege Participants,” published by George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, describes the January 6 cohort according to three distinct categories: “militant networks, organized clusters, and inspired believers.”19 These were drawn from the so-called Patriot movement, unlawful militia groups, the Oath Keepers, Three Percenters movement,d QAnon and assorted conspiracy theorists, street-fighting gangs like the Proud Boys, white nationalist groups like Rise Above Movemente and “Groypers,”f neo-confederates, and other more obscure tendencies.20 There is now strong evidence to suggest that participants also included representatives of nihilistic and occultist neo-Nazi tendencies associated with the “Siege” subculture.21 g These groups often identify themselves by the use of “skull mask” neck gaiters.22

But perhaps most worrying of all, are those Americans who were not previously affiliated with any of the above groups but are now increasingly drawn into the large tent of the networked extreme far-right. On January 6, it was unaffiliated individuals who appeared to represent the plurality of rioters.23 To date, the majority of people charged for crimes related to the insurrection have no known ties to extremist groups.24 It is possible that some proportion of these individuals acted out of character and were ‘swept up’ in the crowd, but it should be noted that scholars of the psychology of riots have long rejected the so-called “mad-mob theory” of riots as inadequate.h The fact that many who stormed the Capitol had a lack of formal affiliation far from rules out casual engagement or personal identification with extremist movements and ideologies. It does, however, indicate that most participants in the insurrection were drawn together by factors beyond formal organization or group affiliation.

The presence of the Trumpist base at events also attended by members of far-right extremist groups is significant for several reasons. First, premeditated terrorist actors can knowingly exploit the right to peacefully protest in order to camouflage their own actions. A mass of legal protestors can provide operational cover in which terrorists can move undetected, transforming “the civilian population into the sea in which the guerilla [can] swim.”25

Second, the presence of the Trumpist base at such events offers a prime recruitment opportunity for extreme elements in the crowd. Outreach such as this can be ideological and social, as seen at the pro-Trump rally in Washington, D.C., on November 14, 2020.26 It can also take the form of “nonaligned” demonstrators becoming swept up in the mania of the riot, as the Capitol riot turned into a “free-for-all, plunder for plundering’s sake.”27 It seems possible, likely even, that some of the Trump base who did not travel to Washington on January 6 have seen media reports of nonaligned demonstrators who stormed the Capitol and have identified with them based on demographic and cultural markers such as age, ethnicity, geography, attire, slogans, etc. This could in turn lead some to identify with the emerging insurrectionary coalition that seeks to mobilize that base to its own specific ends.

How Online Ecosystems Help Accelerationism

The events of January 6 represent both an apotheosis of the emerging extreme far-right coalition and a galvanizing moment to launch its future. In its role as a galvanizing moment, January 6 has spawned a variety of narratives with potential for cross-movement appeal, catalyzed in part by the ease of their production and circulation in online contexts. As the fringe of the extreme far-right enjoys greater access to unaligned sympathizers (both online and off), one may expect these aspirations toward collapse to circulate between them as freely as any other narrative or ideological position. The authors of this article are presently unaware of any empirical work measuring the frequency of accelerationist messaging or sentiment. However, it is possible (and indeed, until such an empirical study emerges, it is necessary) to assess the present situation symptomatically. To do this, the authors analyze what is known about the accelerationist views of established groups (described above) in light of what is known about the communicative and operational practices of the broader extreme far-right.

Between January 6-13, 2021, a team of researchers in the authors’ lab—the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL)—conducted an exploratory analysis of online content within white supremacist extremist channels on Telegram. The result of the coding indicated that anti-establishment, martyrdom, and accelerationist themes accounted for roughly one-third of narrative and rhetorical content sampled across 23 white supremacist far-right Telegram channels with a range of 1,000-47,000 subscribers each.28 Anti-establishment and accelerationist narratives saw considerable overlap, the former defined as general anti-government and anti-society sentiments and the latter defined as advocacy for violence in bringing about their downfall and/or celebrating January 6 as a turning point in the march toward societal collapse and/or civil war. In other words, anti-establishment sentiments represent the emotional motive for accelerationist tactics and “anti-ideology.” Martyrdom, which celebrated sacrifice for the cause of white supremacy and/or the overthrow of society, also fed a general tone of hoped-for collapse. Less frequently, content discussed how to “red-pill” (that is, radicalize) “normies” (that is, unaffiliated and not-yet radicalized audiences). In all cases, a tipping point was sought. Of course, the search for such a tipping point has historically been common to extremist viewpoints.29 However, in light of anti-societal and pro-accelerationist viewpoints, the implied outcome of these is toward collapse. The exploratory study conducted by PERIL staff suggests that January 6 was viewed by some as just such a tipping point, but further research with a larger sample across a broader range of online extreme far-right spaces is required before any more definitive conclusions can be drawn.

To be sure, these channels present a picture of the furthest vanguard of the extreme far-right. However, these themes do not need to be explicitly connected, either to one another or to a specific ideology, faction, or subculture. Due to the fast-flowing nature of digital communication, and due to the easy juxtaposition of content afforded by the cut, link, copy, paste, and embed features of digital media, these themes and their ideological or subcultural framing are assembled collage-style in the mind of the audience. Narratives and identifications accrue rather than progress in a logical argumentative style, appealing to emotions rather than reason. Together, these themes offer a powerful narrative of heroic purpose and willingness to sacrifice for the sympathetic audiences that encounter them.

Themes like martyrdom and victimhood (which appeared in roughly eight percent of all the aforementioned content analyzed) create powerful emotional investments in this accrual of narrative and identity. These two themes most frequently appeared in content describing the events surrounding the death of Ashli Babbitt. Babbitt was a 35-year-old veteran of the U.S. Air Force who was shot and killed by law enforcement while she attempted to climb through a broken window into the Speaker’s Lobby of the U.S. Capitol.30 She has since come to represent heroism and martyrdom among many of the tendencies inspired by the January 6 attack.31 One post remarked that Babbitt and others killed on January 6 were “people you can recognize, relate to … they’re people you can look into the eyes of and say ‘they didn’t deserve this, they died for this.’”32 This post reflects a larger assumption among the members of this loose, undeclared coalition: most do not view themselves as an elite or select body, but rather as the vanguard of a sleeping majority that will either rise up to assist them in a future civil war or will at least welcome the new order once it has been established. The populist attitude is key in linking the extreme fringes surveyed in the authors’ sample with the much larger group of Americans, including elements within the Trump base whom they target for recruitment and propagandizing. Crucially, however, this view does not reflect the attitude of the more luridly mystical groups and nihilists for whom wholesale destruction is its own moral and metaphysical good.

It is not merely the content of the media bringing together insurrectionist groups across the extreme far-right spectrum. The tools of digital communication themselves promote easy juxtaposition of media and social networks, at the level of both infrastructure and platforms. At its most fundamental, the world wide web is stitched together with hyperlinks: small, simple lines of code that connect any two data points on the web. These lines of code have been simplified and automated such that creating them constitutes a routine part of even the most casual web user’s activity. Yet this simple tool to juxtapose data points also allows the close association of previously siloed subcultures. A link in a yoga Facebook group may take users to a QAnon thread, which may just as easily lead to the kind of conspiratorial conversations in which many of the January 6 insurrectionist groups participated. In the mind of a vulnerable user, the mere presence of these connections implies legitimate affinity between the groups. Without this underlying communication and networking structure, it is difficult to see how such a broad, ecumenical, unified but loose-knit coalition could come to be.

Furthermore, this loose-knit coalition of insurrectionist tendencies would not have become the mobilized force of January 6 were it not for social media, including so-called “alt-tech” and especially the Parler platform (effectively a Twitter clone). In the weeks following the 2020 U.S. presidential election, the far right moved en masse to Parler. Here, far-right users “could share and promote ideas without worrying about the company blocking or flagging their posts for being dangerous or misleading.”33 Mainstream social media sites had ramped up enforcement of policies against spreading disinformation and threats of violence in the run-up to the election, and it appears to be the case that the coinciding crackdowns helped to shepherd a mass exodus to alt-tech. In turn, this mass exodus fostered the mixing of various tendencies with grudges pertaining to the election.

This development stands in sharp contrast to prior “deplatforming” waves, which tended to target one particular tendency or narrow topic (e.g., Gamergate,i the alt-right, etc.). The concurrent banning of QAnon-related content likely contributed to this cross-pollination as well.34 QAnon’s highly adaptable conspiracy narrative and generally cordial attitude toward fellow travelers35 likely fostered connections during this migration, both between Q supporters and other extremist tendencies, and between tendencies via QAnon-spread content. While Parler has since declined in popularity, Telegram appears now to serve as the single-stop, online social space for the extreme far-right; the app’s Apple Store downloads increased by 146 percent the week of January 6, 2021.36

The Trump Factor

The rhetoric and actions of Donald Trump while president were in the authors’ assessment a key factor in the coalescing of the inclusive accelerationist network. The extreme far-right, J.M. Berger noted, does not typically “synchronize.” However, Trump “provided … a central nexus of the force of gravity that pulls them all into alignment.”37 Several January 6 arrestees have explicitly stated that they undertook their actions on behalf of the then-president.38

During the years in which this loose-knit, accelerationist network was forming, Trump was a charismatic leader around whom each extreme far-right tendency—no matter how bespoke and idiosyncratic—could rally.39 His rhetorical vagaries offered a blank screen on which these tendencies could project their desires.40 And his relentless repetition of entirely false conspiracy theories provided moral justification and a sense of heroic purpose to those who stormed the Capitol that day.41

It remains to be seen whether the former president will still hold the position of influence he once did. It seems unlikely that he could. By failing to support the rioters after they entered the Capitol, and by at least tacitly acquiescing to the election of President Joe Biden, some in this network have come to see him as a traitor or a coward.42 On the other hand, with Trump out of office, the inherent contradictions of an anti-government movement with the federal executive as its figurehead is at last resolved. The acceleration can continue as planned.

Conclusion

January 6 represented an apotheosis for this new extreme far-right accelerationist network, just as it has become a moment of reckoning for the mainstream of society. The Capitol insurrection no doubt helped to inspire the Biden administration’s heightened concern over domestic extremism,43 just as it has sparked renewed energy among those conservatives determined to retake control of the Republican Party from Trump loyalists.44 But it has also become a source of renewed momentum and energy for the extreme far-right. It is a unifying symbol, an example of a victory that almost was and might still be. It has empowered and emboldened its admirers while offering an opportunity to exercise the common terrorist tactic of studying and learning from failed actions.45

It remains unclear whether the coalition that formed on January 6 will ultimately reflect a fleeting, one-time moment in the history of the extreme right or if it will be the first among many examples of unifying events that even temporarily bring together groups and individuals from across a fragmented ideological spectrum. More cross-national research would be useful to determine whether and how accelerationist networks are communicating across borders, taking inspiration from each other’s violent acts, and finding ways to align to bring down their own national systems through violent and insurrectionist action. Finally, the events of January 6 signaled increased engagement from women, who have historically been less engaged in violent action on the extremist fringe, in ways that deserve more attention and study. Ongoing research will likely benefit from an exploratory spirit, since it appears that this “ecumenical” extreme far-right is itself in a mode of discovery and experimentation, as consolidation remains the order of the day and collapse the dream for tomorrow. CTC

Brian Hughes is the associate director of the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL) in American University’s Center for University Excellence (CUE), where he develops studies and interventions to reduce the risk of radicalization to extremism. He is a lecturer in the American University School of Communication. Twitter: @MrBrianHughes

Cynthia Miller-Idriss is a professor in the School of Public Affairs and in the School of Education at American University and is the director of the Polarization and Extremism Research & Innovation Lab (PERIL) in the university’s Center for University Excellence (CUE). Dr. Miller-Idriss has testified before the U.S. Congress and regularly briefs policy, security, education and intelligence agencies in the United States, the United Nations, and other countries on trends in domestic violent extremism and strategies for prevention and disengagement. Her most recent book is Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right (Princeton University Press, 2020). Twitter: @milleridriss

© 2021 Brian Hughes, Cynthia Miller-Idriss

Substantive Notes

[a] Scholar John Horgan has defined incels as “an online community of mostly heterosexual men [whose] self-worth is defined by what they would see as physical and sexual inadequacy.” Jordan Culver, “A Canadian teenager has been charged with terrorism inspired by the online ‘incel’ movement. What is an ‘incel?’” USA Today, May 21, 2020.

[b] In March 2021, The New York Times reported that “some of the most prominent groups that participated [in the U.S. Capitol riot] are fracturing amid a torrent of backbiting and finger-pointing” with rifts emerging within far-right extremist groups such as the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, and Groyper Army. Neil MacFarquhar, “Far-Right Groups Are Splintering in Wake of the Capitol Riot,” New York Times, March 1, 2021 (updated March 3, 2021).

[c] “An iconic figure of the radical right, Louis Beam played a key role in shaping the revolutionary racist movement in the United States during the three decades following the Vietnam War as one of [the movement’s] principal theorists and strategists.” “Louis Beam, Extremist Files,” Southern Poverty Law Center.

[d] The Three Percenters are “a wing of the militia movement that arose as part of a resurgence of the militia movement in 2009. The term “Three Percenter” refers to the erroneous belief that only 3% of colonists fought against the British during the Revolutionary War—but achieved liberty for everybody. Three Percenters view themselves as modern day versions of those revolutionaries, fighting against a tyrannical U.S. government rather than the British.” “Three Percenters,” Anti-Defamation League.

[e] “The Rise Above Movement (RAM) is a white supremacist group (originally known as DIY Division) that originated in southern California in 2017, with the goal of fighting against the “destructive cultural influences” of liberals, Jews, Muslims and non-white immigrants. RAM is part of the alt right segment of the white supremacist movement. Operating almost like a street-fighting club, RAM emphasizes physical fitness, boxing and martial arts.” “Rise Above Movement,” Anti-Defamation League.

[f] “Groypers are a loose network of alt right figures who are vocal supporters of white supremacist and ‘America First’ podcaster Nick Fuentes.” “Groyper Army,” Anti-Defamation League.

[g] “Siege is an anthology of violent pro-Nazi and pro-Charles Manson essays written by American neo-Nazi James Mason in the 1980s and first published as a single volume in 1992. The book has since inspired a generation of neo-Nazis who have formed a violent online subculture called Siege Culture devoted to Mason’s calls for independent terror cells to carry out a race war.” “James Mason’s Siege: Ties to Extremists,” Counter Extremism Project.

[h] Academic research into the psychology of riots offers a valuable framework with which to view the January 6 insurrection. According to scholars Matthew Radburn and Clifford Stott, “There are three ‘classical’ theoretical explanations of the crowd that endure in the popular imagination. The first, ‘mad mob theory,’ suggests that individuals lose their sense of self, reason and rationality in a crowd and so do things they otherwise might not as an individual. The second is that collective violence is the product of a convergence of ‘bad’ – or criminal – individuals enacting their violent personal predispositions together in the same space. The third is a combination of the first two and is captured in the narrative of Joker: ‘The bad leading the mad.’ … While these explanations are often well rehearsed in the media, however, they do not account for what actually happens during a ‘riot.’ This lack of explanatory power has meant that contemporary social psychology has long rejected these classical explanations as inadequate and even potentially dangerous – not least because they fail to take account of the factors that actually drive such confrontations. In fact, when people riot, their collective behaviour is never mindless. It may often be criminal, but it is structured and coherent with meaning and conscious intent.” Matthew Radburn and Clifford Stott, “The psychology of riots – and why it’s never just mindless violence,” Conversation, November 15, 2019.

[i] Gamergate “arose in 2014, ostensibly over concerns about ethics in game journalism, and quickly coalesced into a group of self-identified members whose concerns expanded to include the rise of what they labeled ‘PC culture’ and ‘social justice warriors.’ The more vocal of the group typically harass people, more often women and minorities, who question some of the status quo of game content in the video game industry.” Brian Crecente, “Inside the ADL’s Plans to Take on Gamergate, Hate in Gaming,” Variety, June 29, 2018.

Citations

[1] “Trump Supporters Storm Capitol; DC National Guard Activated; Woman Fatally Shot,” Washington Post, January 7, 2021.

[2] “The Capitol Siege: The Arrested And Their Stories,” NPR, April 2, 2021.

[4] For more on the security threat posed by QAnon, see Amarnath Amarasingam and Marc-André Argentino, “The QAnon Conspiracy Theory: A Security Threat in the Making?” CTC Sentinel 13:7 (2020).

[6] Mike Giglio, “A Pro-Trump Militant Group Has Recruited Thousands of Police, Soldiers, and Veterans,” Atlantic, November 2020; Jason Wilson, “US militia group draws members from military and police, website leak shows,” Guardian, March 3, 2020.

[7] “‘This Is Our House!’ A Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill Siege Participants,” George Washington Program on Extremism, March 2021; Robert A. Pape and Keven Ruby, “The Face of American Insurrection: Right-Wing Organizations Evolving into a Violent Mass Movement,” University of Chicago, Chicago Project on Security & Threats, January 28, 2021.

[8] Rachel Goldwasser, “Well Before The Jan. 6 Insurrection, Oath Keepers Trafficked in Violence and Conspiracy Theories,” Southern Poverty Law Center, February 12, 2021; Sam Jackson, Oath Keepers – Patriotism and the Edge of Violence in a Right-Wing Antigovernment Group (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020).

[10] Bob Altemeyer, Right-Wing Authoritarianism (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1981); John W. Dean and Bob Altemeyer, Authoritarian Nightmare: Trump and His Followers (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2020).

[11] Brian Hughes, “‘Pine Tree’ Twitter and the Shifting Ideological Foundations of Eco-Extremism,” Interventionen: Zeitschrift Für Verantwortungspädogik 14 (2019): pp. 18-25.

[12] Michael Freeden, “The Morphological Analysis of Ideology” in Lyman Tower Sargent and Marc Stears eds., The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 120.

[13] Slavoj i‑ek, “Against the Populist Temptation,” Critical Inquiry 32:3 (2006): p. 570.

[14] “‘This Is Our House!’ A Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill Siege Participants.”

[17] Meili Criezis and Kesa White, “Insurrectionist Narratives: A Snapshot Following the January 6 Insurrection,” Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab, forthcoming; Jakob Guhl and Jacob Davey, “A Safe Space to Hate: White Supremacist Mobilisation on Telegram,” ISD Briefing, Institute for Strategic Dialogue, June 26, 2020.

[19] “‘This Is Our House!’ A Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill Siege Participants.”

[20] Mallory Simon and Sara Sidner, “Decoding the Extremist Symbols and Groups at the Capitol Hill Insurrection,” CTVNews, January 9, 2021; A.C. Thompson and Ford Fischer, “Members of Several Well-Known Hate Groups Identified at Capitol Riot,” PBS Frontline, January 9, 2021.

[21] “Woman Accused of Stealing Nancy Pelosi’s Laptop Appears in Video Making Nazi Salute,” Bellingcat, February 24, 2021; Peter Smith, “Neo-Nazi Terror Groups Looking To Washington DC Violence To Help Radicalize Trump Supporters,” Canadian Anti-Hate Network, January 11, 2021.

[23] Pape and Ruby.

[24] Ibid.

[27] Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), p. 31.

[28] Criezis and White. This study’s coding scheme was developed inductively, based on the independent analysis of two PERIL Program Associates with domain expertise (Ms. Criezis and Ms. White). These independent analyses were then compared and synthesized into a final codebook. Published report forthcoming.

[29] Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, Friction: How Conflict Radicalizes Them and Us (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[30] “The Journey of Ashli Babbitt,” Bellingcat, January 8, 2021.

[31] “Far-Right Extremists Memorialize ‘Martyr’ Ashli Babbitt,” Anti-Defamation League, January 15, 2021.

[32] Criezis and White.

[35] “The QAnon Conspiracy: Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy.”

[38] Pape and Ruby.

[41] Dave Goldiner, “Barr Says Trump’s Claims That Election Was Stolen ‘Precipitated the Riots’ at Capitol,” New York Daily News, January 19, 2021; Pape and Ruby.

[42] ArLuther Lee, “Capitol Rioters Feel Betrayed by Trump, Lawyer Says,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, January 22, 2021; Joe Sommerlad, “‘The Final Betrayal’: Trump Supporters Denounce President on Reddit after He Suddenly Decries Capitol Riot Violence He Incited,” Independent, January 8, 2021.

[43] Ken Thomas and Sabrina Siddiqui, “Biden Says Rioters Who Stormed Capitol Were Domestic Terrorists,” Wall Street Journal, January 7, 2021; Matt Stieb, “Biden Admin Takes Steps to Defuse Domestic Extremism,” New York Magazine, April 4, 2021.

[44] Matthew Daly, “Led by Cheney, 10 House Republicans back Trump impeachment,” AP News, January 13, 2021; David Smith, “Never Trumpers’ Republican revolt failed but they could still play key role,” Guardian, February 7, 2021.

Skip to content

Skip to content