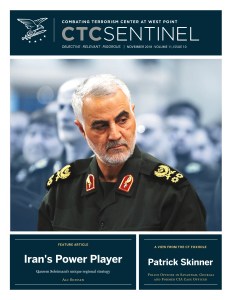

Since 2017, Patrick Skinner has worked as a “beat cop” in Savannah, Georgia. He is a former CIA case officer, with extensive experience in source handling and source networks, specializing in counterterrorism issues. After leaving the CIA, he worked as Director of Special Projects for The Soufan Group. In addition to his intelligence experience, he has law enforcement experience with the Federal Air Marshal Service and the U.S. Capitol Police, as well as search and rescue experience in the U.S. Coast Guard. Follow @SkinnerPm

Editor’s note: Patrick Skinner is not speaking in any capacity for his police department. The views he expresses are his alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Government.

CTC: Earlier this year, The New Yorker ran a profile of you entitled “The Spy Who Came Home,”1 which outlined how you went from working for the CIA on counterterrorism in the decade after 9/11 to becoming a beat cop in Savannah, Georgia. The article described how you applied lessons learned working in intelligence and counterterrorism to local policing. It would be great if you could speak to that, but we’d also like to focus on the other side of the equation and discuss insights you may have gained from police work at the community level that may be applicable to counterterrorism and counterinsurgency.

Skinner: The response to that New Yorker profile, from my fellow beat cops and people in other agencies and departments, continues to be amazing. I perhaps have an odd view point, as a [former CIA] case officer having seen places where the badge means nothing while the gun means everything. Yet, now I still see such places, but instead of a failed state—whatever that means—it’s a few houses in a block or two in an American city.

In my new life as a local cop in my hometown, I’ve spent the last year or so trying to apply whatever lessons I tried to learn as a CIA Operations Officer (OO, though usually still called a Case Officer) working in the Counterterrorism Center (CTC). Some of those lessons have proven immediately and consistently invaluable: embracing the truth that I don’t know much about a scene I have been sent to; asking more questions than making statements; trying to understand the motivations of the people with whom I engage in times of tremendous stress; writing clear reports on what actually happened and not what I wanted to happen. The tools of the trade for a case officer are in many ways the tools of the trade for a local beat cop. Daily, I see how my time with CIA shapes my time with my police department.

I can only speak from my limited experience in trying to apply our counterterrorism strategy overseas as a case officer and now trying to apply our ‘community policing’ strategy in my hometown, and I don’t have academic research to support my observations and my personal lessons learned. But I feel that we are trying to do the same thing in both instances with the same ill-fitting tactics, and we don’t see this because we use such very different rhetoric when describing efforts at home and overseas. We attempt (meaning we plan, fund, and execute) campaigns overseas that we would never, ever try here at home. Yet, both are the same side of the coin, only looked at from different angles. If I had to sum it up in one sentence, I would say that in our overseas CT and COIN endeavors, we are constantly retrying the impossible at great cost and greater negative consequences. I think that for both local policing and overseas CT and COIN, it is only by examining challenges at a hyper-local level that progress can be achieved.

CTC: What prompted you to make such a big career change and join your local police department?

Skinner: After leaving the CIA, I returned to Savannah and worked as an analyst in the private sector examining counterterrorism and security issues. It was all important work, but I was writing about places I hadn’t been to in a while. And it dawned on me that I had little sense what was happening in my hometown. We have a crime problem like most American cities, especially in the South. After working so long on issues affecting far-off places, I wanted to do something that made a difference in my local community.

CTC: How has your CIA training helped you as a beat cop?

Skinner: Let me give you just one example. It was emphasized during our training that one should try not to make a verbal mistake. Whatever you do, don’t screw up by saying something wrong. If you don’t know what to say, don’t say anything. The Agency taught you [to] never disrespect somebody. Always be respectful at all times. Listen. Don’t be rude. Don’t be arrogant. And so I do that now as a beat cop in Savannah, with every single call. And it’s paying off, so far anyway.

CTC: What parallels are there between your counterterrorism work and fighting crime?

Skinner: In some respects, it’s exactly like terrorism. There are a handful of network-based people that commit most of the crimes in our city, and so I approach my work accordingly. It’s almost counterinsurgency, even though this is my hometown. I will not disrespect anybody that’s a criminal. If we did that in counterinsurgency [overseas], we probably wouldn’t be having the problems we have.

CTC: Because it’s about getting the local community on your side?

Skinner: Yeah, or at least not against you. With many criminals, they know their job is to break the law and your job is to catch them. When you make arrests, you don’t have to gloat. Just put the handcuffs on them and talk to them about whatever they ate for dinner or whatever. I arrest a lot of people, and I see them a week later, or a month, it depends on the crime.

One of the things I learned at the CIA was the importance of area familiarization. But I’ve now moved past that and realized that I need to know area familiarization from the people who live there, and that’s almost impossible to do as a tourist. The way we operate in a lot of places where we’re doing COIN and CT operations, we’re tourists at best. In fact, we’re walking around with the word “outsider” written all over us. It’s hard to do here because I’ve literally got police written on me, but it’s even harder to do overseas.

CTC: One of the things you mentioned in the New Yorker article was that the CIA had taught you to realize how much you did not know. How key is such humility to both policing and counterterrorism work overseas?

Skinner: It’s such an important thing to realize when you’re crafting your objectives. If you understood not just that you don’t know a tremendous amount, but that you can’t know it, your goals would be very, very different. And you would more clearly see the things you should and could do. When I listen to people in Washington D.C., and even sometimes when I hear our police leadership, start talking grand strategies or demanding more intelligence, I’m very, very aware now of how difficult that is.

Being a beat cop in Savannah has made me keenly aware of the difficulties in fighting crime, even here at home, and that has transformed the way I view CT overseas. Let me preface this by saying there are things that work like targeted raids, which are really effective in keeping network-based groups off balance. This is the case for both policing at home and CT work overseas. Raids based on solid intel (or warrants based on solid probable cause) are very effective at disrupting known threats. The issue is when those raids become the strategy because nothing else works. If you get lucky enough to get a decent source, you can wreck these network-based groups.

But when it comes to larger, almost nation-building type efforts and counterinsurgency, I’ve become worse than pessimistic. Today, as a beat cop, I see how difficult it is to get information for people in one block, two houses on one block in my hometown with home field advantage, speaking the same language, with unlimited time. And very often, we can’t do it. Yet, you’ll get somebody coming up with a white paper and say, “All you need to do is to get the Shi`a in this half of a country on your side. We just need to know more insight into this community.” And that’s insane. I’ve worked on gathering intelligence like that, and a lot people I know still do, and you don’t really see how insane that is until you have to do that in one row of houses here in America.

If we understand that, then we can maybe shape more realistic policies instead of repeating hollow mantras like “we’re gonna win hearts and minds.” I don’t even know what that means. My experience so far as a police officer tells me we can’t even do that here. And we have unlimited time here. We live here. But when it comes to overseas, it’s the reverse situation: they live there, and we have very limited time and very limited mobility, limited resources. But despite all this, we ask more of the CT and counterinsurgency staff overseas than we would ever ask here.

For those who say, “Oh, we just gotta win hearts and minds,” I’ll put it this way: if in roll call here in Savannah, my sergeant said, “OK, Skinner, you’ve got one week to figure out what’s going on in these two blocks. You gotta know these people’s hopes, aspirations, fears, political leanings, and then get them to tell you where the criminals are,” you know what the result would be? Despite no language limitations and even if I was allowed to wear plain clothes, I would fail miserably, and it would almost certainly be counterproductive because I would try to rush it. We do that overseas all the time, except we do it by provinces and even entire countries rather than two blocks. The unbelievably large scale of what we were/are trying to do overseas in our CT/COIN endeavors is really clear to me now as a beat cop responsible for a few blocks in my hometown. I find that humbling, looking back and looking ahead.

CTC: What challenges did you face in obtaining intelligence when you worked in counterterrorism for the CIA?

Skinner: When I was focused on Afghanistan, we were going after some pretty big people, always going after the next number three or four in al-Qa`ida. I was in a lot of different places, but in the east, we were working right along the Afghan border, so it was usually a high-level target. And that’s such a weird problem to work because you’re not really getting the local community involved in that because they’re not going to support you no matter what. Even if they agreed with you, they can’t [help you] because they’ll get killed. By definition, we were invaders.

We had a lot of successes that didn’t mean a lot. Or they were, at best, temporary. I had no problem with that. If we could keep a group off balance by continually knocking out mid-level management, well, that was my job and that was fine. And we were pretty good at it. Critics refer to it as whack-a-mole, but it did contain the problem to some degree, even if it did nothing to address the larger issues behind the threat. That’s the point I was making earlier about raids. They’re good, but they’re not a strategy.

A war zone is not really clandestine. I mean, everybody knows who you are. If you’re in these locations—and I spent significant time in Afghanistan and Iraq—you’re limited in the way you move. And you can’t fool yourself; it’s not clandestine. What you do is barely espionage. We were using espionage-lite tactics to basically get leads.

I was focused on AQI in Iraq back in 2009, 2010. In 2009, the year before there was a big fall off in their operations, they were really active, and we were in a we-need-to-stop-the-next-car-bombing mode because they were just devastating. We spent a lot of time working with just a handful of sources where you’re just running them as skillfully as you could, relying on them. It was getting the information on the intentions of small cells.

It was in hindsight very myopic. We were looking through the wrong end of the telescope because we had little idea about what was going on around these cells, and we likely inflated their importance because we happened to know about [their existence]. The massive problem was that we were doing CT in the middle of a quasi-war. That’s insane. But we did it because we didn’t have a lot of options.

Our biggest problem was you couldn’t move around very well. That was always the biggest issue. It was obvious [I was an] American spy overseas anywhere I went in a war zone. I had a great beard, but I’d be burned before I even got out of the car. So we were getting played because we couldn’t move around. We only knew what the people who were already telling us stuff were telling us, and so you could fall into the whole feedback loop. You had no idea what was going on.

The sheer pace of operations—and this was very much like local police where the 9-1-1 calls are relentless—you going to fall back into what seems to work, and you’re going to do it every single time. Before you have a chance to reflect and assess, you’re onto the next operation.

CTC: What are the lessons you’ve learned as a beat cop in Savannah that you think could be applied to counterterrorism and counterinsurgency?

Skinner: I know from my police work that a small fraction of criminals commit a large fraction of the crime. In the United States, we call them gangs. Overseas, some of these criminals are labeled terrorist groups. In both cases, it’s network based, based on families or neighborhoods or other forms of connections. It is small cells. And so investigators—case officers overseas or detectives here in the United States— need to focus on those [networks or cells]. And you need to be very, very, targeted.

One track is avoiding mistakes. I’m very aware at work every day of the potential consequences of doing something wrong to someone, for example humiliating or disrespecting them. The damage is so immediate. One bad impression will overcome 10 good experiences. I’m hyper aware of the fact that I am acting in the name of the state. And I am very, very, very hesitant to use that power until I know that I’m right. And does that mean that I’m a hesitating cop? Well, no, but it probably means I’m not gonna make a lot of mistakes. I do not want to make a mistake in the name of the state, using the power of the state. But overseas, we do that a lot. It’s not our intention. We call it collateral damage, but it’s killing innocent people or it’s raids based on bad intel. You want to avoid kicking in doors in the wrong house, which we did overseas all the time. And we kind of just missed the very large impact that has on people. I would say, exercise more caution than you think you should. You really don’t want to make mistakes. I can’t stress this enough. Mistakes made in law enforcement or CT are devastating to individuals. Mistakes in law enforcement and CT made repeatedly are devastating to communities and entire systems of justice.

Another track is trying to put people at ease. As a cop where you go out and are chatting to people, you are putting people at ease and you’re getting a lot of baseline information. You’re building goodwill or at least you’re building the absence of ill will. I’m not fooling myself that I’m winning hearts and minds so much as seeking in the moment I have with a person to make some connection. And then build on that every chance I get.

This community based-approach to policing cannot be just based on individual ad hoc efforts. It has to be systematically ingrained through training. The problem is that it’s virtually impossible for outsiders to successfully do this in a place like Iraq or Afghanistan. The only way this approach can really pay dividends overseas is if it’s locals—whether it be Iraqis or Yemenis or Afghans—who are the ones doing it. But their law enforcement at times barely existed, and that’s where things fell apart. Because we were just relying on raids and drone strikes with limited ground collection because we didn’t have the community policing. And in that situation, you’re going to start making a lot more errors because your intel is bad. And that’s going to generate a loop of failure.

What I really came to believe in is most of the problems we faced were because of the collapse of local law enforcement and also more importantly, local governance. It was this collapse that allowed ISIS to go from a criminal gang to taking over large parts of Iraq and Syria.

The lack of local governance and fair, accountable, transparent, decent, non-heavy handed, local policing causes network-based cells to metastasize. We can’t really do anything until we fix that, and sometimes we can’t because these places are so broken. But despite this, we keep on coming up with grand strategies to “improve governance” and deluding ourselves they will work.

CTC: So what’s the alternative?

Skinner: The alternative is you want to begin whatever your big plan is with the absolute, overwhelming understanding and embrace of the fact that these issues are hyper, hyper local in a way you can’t possibly understand. And then see how you can address that. And that’ll scale back your ambitions and make you tailor your resources in a more targeted way. The U.S. military got it right in a few places in Iraq. They were not in a position to fix Baghdad or the central government, but they did have the capacity to fix one city block and build some goodwill there. In theory, you can then build that goodwill block by block. You need to have a grassroots counterinsurgency. But while it may sound easy, my entire point is it’s almost impossible to do as a foreign government on foreign soil with a lack of cultural, linguistic, and local knowledge. The surge in Anbar worked because it was a local effort supported by the U.S.; but it wasn’t supposed to win the war. It was supposed to buy time for social and governmental reforms and improvements that never happened. We see this a lot with law enforcement and community outreach in the U.S.; a good idea or something that works in a particular situation becomes ‘the solution’ writ large and of course it can’t be. We rely too heavily on any one thing when the point I’m making, poorly and at length, is there is no one thing, and it is precisely that drive for ‘the one thing’ that wrecks progress.We don’t solve life; we live it. We don’t end crime; we address it. And we should address it in the Hippocratic Oath sort of way of first do no harm to the community.

CTC: All this suggests that it’s only by partnering up with local governments that significant progress can be made on winning hearts and mind and gaining information. Building up the capacity of partner governments and providing training continues to be a key part of the U.S. counterterrorism strategy.2

Skinner: The problem is a lot of those funds in places such as Afghanistan are wasted because of corruption.

CTC: And then there’s the issue of governments in some parts of the world using repressive practices, which might tamp down terrorist activity in the very short term but create bigger problems in the medium to long term.

Skinner: That’s exactly right. I get why we embrace certain governments. Because we like stability. We embrace tyrants with terrible human rights records. That’s not a secret. Nothing new either. But working with unsavory governments can generate a lot more ill will than successes. Like fishing with dynamite. We would have a revolution in the streets tomorrow if we tried one-tenth of the tactics we’re enabling some of our partners to use overseas.

CTC: How can resources be better allocated in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency overseas, and what can be done to make them more impactful?

Skinner: I get waste, but it’s the amount of money we apply to stuff that we know is counterproductive. And then we cry poverty for stuff that doesn’t take a lot of money but has massive impact. You want to help a community? Build a park. Fix the roads. You don’t need to do all this complicated stuff. And overseas, you definitely don’t want to do it where we build massive, incredibly advanced medical facilities that fall into disrepair because of corruption and the lack of underlying infrastructure and training, which is what has happened in Iraq.3

We have relied far too much on so-called “agents of influence.” Here [in the United States], we call them community leaders. And at every stage, they tended to inflate their actual influence and their ability. People who speak for communities here [in the U.S.], they do have some influence, but it’s a self-selecting audience, almost an echo chamber of sorts. They have reach but perhaps not with the true target audience, the people not listening to what the government or even ‘community leaders’ have to say. Overseas in CT work, it was pretty bad. We would work with people because they were easy to work with or had some influence, but then we just kept going back to them for everything. In my limited lane of CT work overseas, I was always less than impressed at the agents of influence we worked with. Now as a beat cop, I try to be that agent of influence on every call and earn that influence the only way it really can work, every day. It’s frustrating but I keep harping on this: these issues, the persistent challenges of CT and law enforcement, they resist grand gestures. They require the opposite of grand gestures. They require countless small gestures.

CTC: The New Yorker noted that over the last 20 years, more than $5 billion of military gear has been transferred to state and local police forces.4 What’s your concern over the potential militarization of the police?

Skinner: In some countries overseas, the police are the military, especially in the Middle East. They literally are the military. Their CIA is the FBI, which is the military. It’s all the same thing. So they patrol in the literal sense. The danger is when we do that here. I think the militarization of police is insane. Cops should not dress like soldiers. Dressing the part matters. But they shouldn’t talk like soldiers. I get that need to have that equipment, and that equipment can be kept somewhere for when you need it. But the heart and soul of a police department needs to be community-based policing and not just the rhetoric of community. It has to be the mentality. It’s not semantics. It has to be the philosophy. It has to be at the center of every single thing you do.

As a member of the community in Savannah and as a police officer here, I use the term neighbor, and I use it all the time. But I use it because it’s actually true. I live four minutes from my precinct police station. If you don’t feel like part of the community, your operations risk being counterproductive. That was the case for some of the CT raids and COIN operations carried out overseas in recent years. Imagine coming home and there’s pretty significant police activity in your neighborhood, and it looks like you’ve been invaded. And then it happens the next month or it happens the next day, and you get pulled over in your driveway every single day. Imagine what would happen if that were happening in your hometown. CTC

Citations

[1] Ben Taub, “The Spy Who Came Home: Why an Expert in Counterterrorism Became a Beat Cop,” New Yorker, May 7, 2018.

[2] Joshua A. Geltzer, “Trump’s Counterterrorism Strategy Is a Relief,” Atlantic, October 4, 2018.

[3] Editor’s note: See Stephanie McCrummen, “At Iraq’s hospitals, a man-made emergency,” Washington Post, May 9, 2011.

[4] Taub.

Skip to content

Skip to content