Abstract: This past summer, the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) launched an offensive that made significant headway against Islamic State forces in northeast Lebanon. But its counterterrorism efforts have repeatedly run into interference from Hezbollah, which not only launched its own operation against al-Qa`ida-aligned militants in an apparent attempt to upstage the LAF but also undercut the LAF’s offensive against the Islamic State by helping to broker safe passage into Syria for a large number of Islamic State fighters. While the defeat and displacement of Sunni jihadis in Lebanon has improved the security outlook for Lebanon (though not Syria and Iraq), Hezbollah’s decision to enter the fray—borne out of concern the LAF might otherwise accrue prestige and strengthen its popular standing to the Iran-backed party’s detriment—risks raising tensions in Lebanon.

The war in Syria, which began in 2011, turned the mountainous ‘backwater’ region of northeast Lebanon into the country’s most significant security challenge. The area eventually evolved into a haven for the Islamic State and Hay`at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), formerly al-Qa`ida’s representative in Syria. By late 2011, the Sunni-populated town of Arsal, eight miles from the Syrian border, became an important conduit for smuggled weapons to the nascent rebel groups battling the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. In June 2013, Arsal received a major influx of Syrian refugees and rebel fighters, more than 25,000 altogether, following the fall of the rebel-held town of Qusayr, five miles north of the Lebanese border.1

In November 2013, Hezbollah and the Assad regime forces of the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) spearheaded an offensive to restore Syrian government control over the Qalamoun region, an expanse of mountainous territory adjacent to the border with northeast Lebanon.2 The campaign, which lasted until April 2014, coincided with a wave of suicide car bomb attacks claimed by al-Qa`ida- and Islamic State-aligned militants targeting predominantly Shi`a areas of Lebanon.a Many of the car bombs were manufactured in militant-held areas of Qalamoun prior to being driven across the border into Lebanon via Arsal.3 The conclusion of Hezbollah’s Qalamoun offensive left most of the towns of the area in Syrian government hands, but hundreds of Sunni rebel fighters and jihadis moved into the mountainous region straddling the border east of Arsal and Ras Baalbek, a Christian village five miles north of Arsal.

On August 2, 2014, a combined force of some 700 militants, drawn mainly from the Islamic State and the then-named Jabhat al-Nusra (the forerunner of HTS), stormed Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) positions in Arsal, triggering five days of fighting. A ceasefire deal five days later saw the militants retreat back to their mountain redoubts to the east, taking with them large quantities of looted arms and ammunition and 36 captured Lebanese soldiers and policemen. Four of the hostages were executed, and seven others were released. Jabhat al-Nusra freed its 16 hostages for 13 jailed militants held by the Lebanese authorities in a prisoner swap in December 2015.4 The fate of the nine soldiers held by the Islamic State remained unknown.

In the aftermath of the battle, the LAF increased its deployment in the northeast area, building a series of fortified checkpoints and observation posts to dominate the ground to the east and control access in and out of Arsal.b

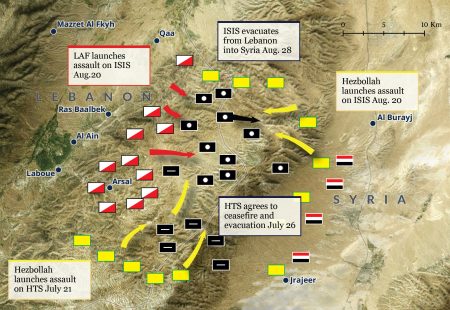

In early May 2015, Hezbollah launched a second operation against Sunni rebel fighters and jihadis in the Qalamoun area.5 By the time the operation ended two months later, the Islamic State and HTS militants had been squeezed into a pocket of mountainous territory that ran from southeast of Arsal to northeast of Ras Baalbek and extended across the border into Syria. The LAF manned a defensive line to the west while Hezbollah deployed in a line of mountain-top outposts to the north and south of the militants. The eastern flank, inside Syria, was guarded by a mix of Hezbollah, Syrian Arab Army (SAA), and loyalist paramilitary forces.

In early 2017, sources close to Hezbollah were indicating that the Sunni jihadis “would not see another winter in the mountains,” heightening speculation that the Iran-backed group was preparing an assault against either HTS or the Islamic State or both.6

Who to Lead?

By the end of June, an offensive to drive out HTS and the Islamic State from Lebanese territory appeared imminent, but it was unclear who would take the lead in the operation. Hezbollah had already chalked up two successful campaigns against the militants in the 2014 and 2015 Qalamoun operations and was well-suited to advance on both HTS and the Islamic State. On the other hand, the LAF was supposed to be the primary security actor in Lebanon, was deemed sufficiently strong to tackle the militants, and had the option of drawing upon U.S. military support if it ran into difficulties.7 Furthermore, the onset of the operation came as the United States was reassessing its level of commitment to the LAF.c The U.S. military support for Lebanon was premised in part on the hope that strengthening the LAF would allow it to stand up to Hezbollah and undermine the party’s argument that only its doctrine of warfare is suitable to defend the country against external threats.8 With Hezbollah stronger than ever, questions were increasingly being raised in Washington as to the point of continuing to provide funding to the LAF.9 d

For the LAF, the upcoming battle against HTS and the Islamic State represented an opportunity to showcase its new capabilities and armaments to its international backers after a decade of support. On July 18, Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri appeared to endorse the LAF playing the lead role against the militants, saying “the army will carry out a well-planned operation in the outskirts of Arsal, and the government gives it the freedom to deal with this issue.”10

Phase One: Hezbollah vs. HTS

Just three days later, however, Hezbollah seized the initiative by formally announcing the start of an operation to attack HTS in its stronghold southeast and east of Arsal and in adjacent areas of Syrian territory in coordination with the SAA.11 The offensive was accompanied by a blaze of publicity with pro-Hezbollah media publishing extensive photos and video footage of fighters in action. The two main Hezbollah units taking part in the operation were the Radwan Brigade and the Haidar Brigade.12 The former is one of Hezbollah’s SOF (special operation forces) units, and the latter is composed mainly of recruits from the Bekaa Valley.13 Hezbollah artillery units provided fire support for the infantry forces while D-9 bulldozers were employed to clear tracks of possible Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and mines. HTS controlled an area of some 35 square miles outside Arsal in Lebanese territory and 13.5 square miles near Flita in Syria.14 Its fighters, numbering around 400, were dug into fortified hill-top positions and also made use of natural caves and man-made bunkers.15

By July 24, Hezbollah claimed to have seized 70 percent of the territory held by HTS in Lebanon and all the terrain held by the group in Syria.16 Losses amounted to 19 dead Hezbollah fighters and 143 militants.17 The HTS defensive lines quickly collapsed with some 30 militants, headed by Abu Talha al-Ansari, an HTS commander, fleeing to Islamic State-held territory and others regrouping on the outskirts of Arsal.18 A Free Syrian Army (FSA) unit, Saraya Ahl ash-Sham, which numbered some 800 fighters, stayed out of the battle, retreating to a refugee camp outside Arsal in preparation for negotiations that would see them and their families granted safe passage to Syria.19

Meanwhile, the LAF was left on the sidelines having been upstaged by Hezbollah. The LAF tightened its measures around Arsal, while permitting Syrian refugees from nearby encampments entry into the town. It also shelled HTS militants seen heading toward Arsal to escape Hezbollah’s offensive.20

The optics of Hezbollah leading the fight against HTS—with the LAF all but marginalized—discouraged the LAF’s backers in Washington and London and threatened to derail the foreign assistance programs.21

On July 26, 2017, Hezbollah and the HTS agreed to a ceasefire brokered by Major General Abbas Ibrahim, the head of the Directorate of General Security.22 In subsequent negotiations, it was agreed that 7,777 people, including 1,116 militants and 6,101 civilian refugees, would be transported in buses from Arsal to the rebel-held Idlib province in northern Syria.e

With HTS evicted from the Arsal area, attention turned toward Islamic State fighters deployed in the mountains east of Ras Baalbek. On August 4, Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s secretary-general, said in a speech that the LAF would carry out the offensive against the Islamic State on Lebanese territory while Hezbollah and the SAA would attack from the Syrian side.23

“I declare tonight that we, in Hezbollah, are at the service of the Lebanese army,” he said, indicating that if the LAF was to run into trouble against the Islamic State, Hezbollah would be available to provide support.24

The Summer 2017 LAF and Hezbollah Offensives against Sunni Militants (Rowan Technology)

Phase 2: The LAF vs. the Islamic State

The LAF estimated Islamic State strength in Lebanon in the summer of 2017 at around 600 fighters divided into three groups—the “Bakri” faction in the northern sector, east of the Christian village of Qaa; the “Ali” faction in the central sector, east of Ras Baalbek; and the “Osama” faction in the south.25 The total area covered by the Islamic State in Lebanon was 46 square miles, according to the LAF.26 Hezbollah said that the Islamic State was in control of 60 square miles of terrain in Syria in the Qalamoun region.27

The LAF deployed some 5,000 troops for the operation against the Islamic State.f The LAF’s theater commander, Brigadier General Fadi Daoud, the commander of the 6th MIB, devised a pincer movement plan with a blocking force to the north and attacking forces from the west and south with the goal of driving the militants eastward into Syrian territory.28

On August 14, the 1st Intervention Regiment (IR) took hills just northeast of Arsal and southwest of the main Islamic State-held area.29 Two days later, the 1st IR attacked Islamic State positions in hills on the southern front of the Islamic State Osama faction. The Islamic State militants put up stiff resistance, wounding several LAF troops.30 The 1st IR was pulled back briefly, and the Islamic State positions were struck with precision munitions—AGM114 Hellfire missiles and 155mm laser-guided “Copperhead” artillery rounds.31 The “Copperheads” were guided onto target by the AC208 Cessna aircraft and by Mukafaha SOF on the ground.32

The Mukafaha also took over several mountaintop outposts that had been manned by Hezbollah along the northern flank of the operational area east of Qaa. The Hezbollah fighters had agreed to a Ministry of Defense request to pull out, and the fighters redeployed on the Syrian side of the border.33

On August 19, the LAF announced the formal commencement of Operation Fajr al-Jurd (“Dawn of the Outskirts”) and noted that the offensive would not be coordinated with the SAA and Hezbollah.34 Hezbollah immediately followed with its own declaration that it was launching its attack on the Islamic State from Syrian territory. The near simultaneous announcements created an impression that the launch of the offensive had been coordinated between the LAF and Hezbollah. During the next few days, pro-Hezbollah media outlets repeatedly stated that the LAF was coordinating its campaign with Hezbollah and the SAA, statements that were interpreted as attempts to embarrass the LAF in front of its U.S. patron.35 One report claimed there was “continuous open communications between the Lebanese army operations center and the operations command of Hezbollah and the Syrian army.”36 The LAF rejected such accusations, and no evidence has emerged to confirm that there was any field coordination during the anti-Islamic State operation.

On August 20, the LAF’s Air Assault Regiment launched a frontal attack from the west on the main defensive line of the Bakr and Ali factions. The LAF made extensive use of the “Copperhead” munitions, firing over 140 rounds at Islamic State targets, destroying machine gun nests, mortar pits, and other fixed positions.37 The synchronicity between the LAF’s command post, artillery batteries, and ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) assets denied the Islamic State militants the ability to maneuver and kept them trapped in their positions.

On August 22, with the Islamic State focused on the LAF threat to the west, the 6th MIB and a company from the 4th IR advanced from the south toward the main concentration of Islamic State forces near Khirbet Daoud.38 The LAF column used D9 bulldozers to cut new tracks through the rocky landscape to avoid using existing routes that were laced with IEDs and land mines.39 The Islamic State militants deployed in Ras al-Kaf, a major stronghold on a 5,200-foot mountain, could see the approaching LAF column to the south and feared they would be cut off from the Syrian border.40 The militants began retreating to the east, and by August 24, the surviving fighters were bottled up in a valley of some 7.5 square miles adjacent to the border.41

The LAF operation had proceeded with an efficiency and speed that drew compliments from foreign military officials. One described the offensive as “21st century maneuver warfare by a modern military.”42 A retired LAF brigadier general who was familiar with the details of the operation told the author, “Two things won the battle—ISR and precision munitions.”

However, the LAF never launched a final assault to oust the Islamic State, as a controversial ceasefire deal emerged on August 27 in which it was revealed that Hezbollah and the Syrian government had agreed to allow the surviving militants safe passage to Boukamal on Syria’s eastern border with Iraq in exchange for information on the nine LAF soldiers who had been captured three years earlier.g The bodies of the soldiers were recovered, and on August 28, some 400 Islamic State fighters and their families departed the Qalamoun region in buses (and ambulances for the wounded) for the journey to Boukamal.43 h In mid-September, the convoy reportedly reached Islamic State-held territory in Syria’s Deir ez-Zour province and across the border in the Iraqi town of Qa’im after the U.S. ended overhead surveillance.44

LAF soldiers on a M113 armored personnel carrier deployed close to the border with Syria on August 28, 2017, a day after a ceasefire was reached with the Islamic State. (Nicholas Blanford)

Conclusion

The LAF’s anti-Islamic State campaign was its most proficient CT operation since the end of the 1975-1990 civil war, and it demonstrated the extent of its improved capabilities since its last major counterterrorism engagement in 2007 against a Sunni jihadi group in north Lebanon.i But the offensive also exposed the strains that exist between the LAF and Hezbollah, which could pose challenges in the future.

While the Islamic State was defeated and the mission of restoring state control over northeast Lebanon appears to have been accomplished, there is some simmering resentment within LAF ranks at what they perceive to have been Hezbollah’s attempts to undermine the operation from the start.45 First, Hezbollah had undercut the LAF by mounting its own offensive against HTS, embarrassing the military in front of the United States and United Kingdom. Then, as the LAF prepared to launch its attack against the Islamic State, Hezbollah leader Nasrallah had warned against asking for help from the United States and instead offered his party’s support if the LAF should run into difficulties.46 When the LAF operation advanced more quickly than had been generally expected, Hezbollah had stepped in with a scene-stealing ceasefire deal, which allowed the Islamic State militants to evade capture or death in battle.

On August 31, Hezbollah held a triumphant “victory” parade in Baalbek in the Bekaa Valley to celebrate the defeat of HTS. However, a similar “Victory Festival,” scheduled for September 14 in central Beirut, to mark the LAF’s win against the Islamic State was postponed two days beforehand. The Lebanese ministries of tourism and defense said in a statement that it was postponed for “purely logistic reasons.”47 But a political source close to Prime Minister Hariri said that Hezbollah had pressured President Aoun, its ally, to drop the parade.48

Hezbollah justifies its continued armed status on the basis that its doctrine of warfare, weapons, training, equipment, and tactics is best suited to defend Lebanon against external threats. Until recently, that external threat was limited to Israel. The LAF lacks the capacity to confront the Israel Defense Forces. But the emergence of groups like the Islamic State and HTS, which the LAF is capable of defeating, combined with the improvements to the LAF as a result of U.S. support, has challenged Hezbollah’s argument that it is the primary security actor in Lebanon.

Other than simmering LAF-Hezbollah rivalry, the operations against HTS and the Islamic State have helped improve security and stability in Lebanon. Both groups were effectively surrounded by the LAF and Hezbollah in northeast Lebanon from 2014, so their ability to export instability into Lebanon was limited. But their presence continued to serve as a pole of reference, inspiration, and potential support for jihadi militants in Lebanon.

Given the presence of Hezbollah, the proximity to Syria, and the presence of some 1.5 million Syrian refugees, Lebanon has been surprisingly fortunate in not having been subjected to more terrorist attacks by radical Sunni groups. Other than a spate of suicide car bomb attacks between July 2013 and June 2014 (in part due to the presence of Sunni jihadis in the Qalamoun area), Lebanon has since only suffered a handful of attacks. Part of the reason is due to enhanced coordination and cooperation between Lebanon’s sometimes rival intelligence services.49 Furthermore, Lebanon’s small size and tangled sectarian demographics grant little operational space for Sunni militant cells to plot and execute attacks without discovery by Lebanese intelligence services.

With the conflict in Syria showing indications of entering a less intense phase, the likelihood of another extremist group seizing terrain in Lebanon appears remote. But should such a development occur, the LAF has demonstrated that it is capable of confronting and defeating non-state, external threats such as HTS and the Islamic State, validating foreign military assistance programs. Hezbollah, however, has expanded the justification for retaining its weapons from one limited solely to the simmering Israel front to a broader interpretation of national security, one that encroaches upon the LAF’s jurisdiction. On September 4, Hezbollah MP Ali Fayyad said, “A few years ago, we used to say that the Resistance [Hezbollah] plays a role in liberating the land and safeguarding Lebanon from the Israeli threat. But today, we can say that the Resistance has a role in liberating the land and confronting anything that threatens this entity, whether Israeli, takfiri, or anything else.”50

If Hezbollah perceives that a more robust and increasingly confident LAF could undermine its national defense rationale, the current, sometimes uncomfortable relationship with Hezbollah could evolve into a more serious rivalry. The LAF is wary of Hezbollah’s sensitivities and does not seek or desire a confrontation with the powerful Shi`a force, which could aggravate sectarian tensions in Lebanon. But the quandary of how to reconcile the tasks, duties, and ambitions of two relatively powerful military forces crammed into Lebanon’s tiny land space will continue to bedevil supporters and opponents of both institutions. CTC

Nicholas Blanford is the Beirut correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor and a non-resident senior fellow with the Middle East Peace and Security Initiative at the Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security at the Atlantic Council. He is the author of Warriors of God: Inside Hezbollah’s Thirty-Year Struggle against Israel, published by Random House in 2011.

Substantive Notes

[a] A log of the attacks compiled by the author at the time shows there were 14 suicide bomb attacks of which 12 were vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices. The attacks were claimed by Jabhat al-Nusra fi Lubnan, the Islamic State, and the Abdullah al-Azzam Brigades, an al-Qa`ida-inspired group based in Lebanon. The bombings killed nearly 100 people and wounded nearly 900.

[b] The British government provided military assistance to the LAF in the tower construction as well as the raising, training, and equipping of (so far) four Land Border Regiments tasked with securing Lebanon’s border with Syria. Nicholas Blanford, “Hezbollah seizing territory along Lebanon’s northeastern border,” Arab Weekly, July 30, 2017.

[c] Since 2005, the United States has provided the LAF in excess of $1.5 billion in military assistance, making Lebanon the world’s fifth-largest per capita recipient of U.S. military funding. The U.S. State Department cut its Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program for Lebanon from its proposed foreign aid budget for 2018, potentially signaling a tougher approach toward the LAF. In 2016, the FMF budget for Lebanon amounted to $85.9 million. Nicholas Blanford, “Lebanese army takes over Hizbullah positions on Lebanese border,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, May 30, 2017; Nicholas Blanford, “Why US may slash military aid to an ally it helped build up in Lebanon,” Christian Science Monitor, July 18, 2017.

[d] The relationship between the LAF and Hezbollah is extremely complex. On the one hand, Hezbollah has significant support in Lebanon, and some in the LAF endorse the party’s anti-Israel credo. Hezbollah wields some influence within the LAF, especially in the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI), and as the dominant political power in the country, it has influence over government decisions affecting the LAF. On the other hand, there are officers and soldiers who bristle at Hezbollah’s military and political power and are uncomfortable with sharing responsibilities of national defense with a non-state actor. Multiple author interviews, LAF officers and soldiers, 2010-2017.

[e] In addition, three Hezbollah fighters captured during the battle were released in exchange for three HTS militants held in a Lebanese prison. HTS also released five Hezbollah prisoners who were captured in the Aleppo province in northern Syria, and both groups swapped the remains of several dead fighters. “Militants leave Lebanon in 3rd phase of swap deal,” Daily Star, August 2, 2017.

[f] The maneuver forces included two mechanized Infantry Brigades, two Intervention Regiments, the Air Assault Regiment and a company of Mukafaha, and a Special Operations Force unit attached to the Directorate of Military Intelligence. Close air support included unmanned aerial vehicles and three AC208 Cessna aircraft fitted with AGM114 Hellfire missiles. Author interview, senior LAF officer, September 2017; author interview, Aram Nerguizian, senior associate, Burke Chair in Strategy, Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 2017. See also Nicholas Blanford, “US operating UAVs in Lebanon,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, March 26, 2015.

[g] The deal was broadly criticized not just by Hezbollah’s political opponents but also by the families of the dead soldiers as well as Hezbollah’s own support base. Many of them were unhappy that a group that had been responsible for staging rocket attacks on Shi`a villages in the Bekaa and staging suicide car bomb attacks was being allowed to go free. Furthermore, the Lebanese government said it had received information that the nine soldiers were executed by their captors in February 2015 but could not confirm the identities of the victims. However, a political source told the author in September 2017 that the government had received a video of the execution in which the nine captives were tied to trees and beheaded, a fact that has not been made public. Author interviews, Hezbollah supporters in southern Beirut, August 29, 2017; Sami Moubayed, “Outcry but noting more after Hezbollah-ISIS deal,” Arab Weekly, September 10, 2017.

[h] The United States did not acknowledge the deal between two groups regarded as terrorist organizations and blocked passage to Boukamal by destroying a bridge and cratering a road. The Islamic State column was not attacked directly due to the presence of civilians. “Daesh release Hezbollah fighter as convoy arrives in Deir al-Zor,” Reuters, September 14, 2017.

[i] The LAF fought a 106-day battle against Fatah al-Islam, an al-Qa`ida-inspired group, in the Nahr al-Bared Palestinian refugee camp from May to August 2007. The fighting saw 168 soldiers killed along with more than 200 militants and dozens of civilians. The camp was completely destroyed in the battle. Nicholas Blanford, “Tough homecoming for Lebanon’s refugees,” Christian Science Monitor, November 14, 2007.

Citations

[1] “Quseiris overwhelm Bekaa Valley town of Arsal,” Daily Star, June 10, 2013.

[2] Nicholas Blanford, “Syrian Army goes all-in to take back strategic highway,” Christian Science Monitor, December 2, 2013.

[3] “Arsal man who sent al-Labweh bomb-laden car killed in Syria,” Naharnet, March 2, 2014; “Arsal residents fear car bomb attacks,” Now Lebanon, March 17, 2014.

[4] Nicholas Blanford, “Chain of Lebanese border forts nears completion,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, December 2, 2014; Nour Samaha, “Lebanese army and al-Nusra Front conduct prisoner swap,” Al Jazeera, December 2, 2017.

[5] Jean Aziz, “The battle at Qalamoun,” Al Monitor, May 11, 2015.

[6] Multiple author interviews, Hezbollah combatants and sources close to Hezbollah, January-April 2017.

[7] Aram Nerguizian, “The Lebanese Armed Forces, Hezbollah and the race to defeat ISIS,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 31, 2017.

[8] Author interview, Andrew Exum, former deputy assistant secretary of defense in the Obama administration, July 7, 2017.

[9] Tony Badran, “The Pentagon fills Hezbollah’s shopping list,” Tablet Magazine, August 15, 2017.

[10] Statement from the Press Office of the President of the Council of Ministers, July 18, 2017.

[11] “Hezbollah launches battle to clear Nusra terrorists from Arsal outskirts,” Al Manar (English), July 21, 2017.

[12] Author interview, source who was in close contact with the Hezbollah operations room during the battle, July 2017.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Nazih Osseiran, “Hezbollah eyes Daesh after swift gains,” Daily Star, July 24, 2017.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Hezbollah fighters liberate key Arsal valley from terrorists’ grip,” Press TV, July 24, 2017.

[18] Osseiran.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Hezbollah rains rockets on militants near Arsal,” Daily Star, July 24, 2017.

[21] Author interviews, diplomats in Beirut and senior LAF officers, July-September 2017; author interview, Aram Nerguizian, senior associate, Burke Chair in Strategy, Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 2017.

[22] Tom Perry, “Hezbollah and rebels agree ceasefire at Lebanese-Syrian border,” Reuters, July 26, 2017.

[23] “Sayyed Nasrallah to ISISL: Lebanese, Syrians will attack you from all sides,” Al Manar (English), August 4, 2017.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Dawn of the Jurds,” a PPS brief of Islamic State deployment, LAF Directorate of Orientation.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Sayyed Nasrallah to ISISL: Lebanese, Syrians will attack you from all sides.”

[28] Author interviews, senior LAF officer and retired senior LAF officer, September 2017.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Tom Perry and Angus McDowall, “Lebanese army, Hezbollah announce offensives against Islamic State on Syrian border,” Reuters, August 19, 2017.

[35] Ibrahim al-Amine, “Lebanese army denial of coordination with Hezbollah should not be ignored,” Al-Akhbar, August 28, 2017; see also messages from the Hezbollah-affiliated War Media Center on the Telegram messaging app.

[36] Al-Amine.

[37] Author interview, Nerguizian.

[38] Author interviews, senior LAF officer and retired senior LAF officer, September 2017.

[39] Author interview, Nerguizian.

[40] Author interview, senior LAF officer, September 2017.

[41] Paula Astih, “Lebanon: 20 square kilometers separate army from defeating Daesh,” Ash-Sharq al-Awsat, August 23, 2017.

[42] As told to Aram Nerguizian, senior associate, Burke Chair in Strategy, Center for Strategic and International Studies.

[43] Rod Nordland, “Lebanon frees hundreds of ISIS fighters in exchange for soldiers’ bodies,” New York Times, August 28, 2017.

[44] “Syria war: Stranded IS convoy reaches Deir al-Zour,” BBC News, September 14, 2017; “Daesh release Hezbollah fighter as convoy arrives in Deir al-Zor,” Reuters, September 14, 2017; Rob Nordland and Eric Schmitt, “Why the U.S. Allowed a Convoy of ISIS Fighters to Go Free,” New York Times, September 15, 2017.

[45] Author interviews, LAF officers and soldiers, August-September 2017.

[46] “Sayyed Nasrallah to ISISL: Lebanese, Syrians will attack you from all sides.”

[47] “Report: Hezbollah pushed for postponement of Lebanon Arsal ‘victory festival’,” Ash-Sharq al-Awsat, September 13, 2017.

[48] Author interview, political source close to Prime Minister Hariri, September 2017.

[49] Author interviews, senior Lebanese intelligence officers and politicians, September 2016-May 2017.

[50] “Fayyad says Resistance’s ‘vital role’ brought stability to Lebanon,” Naharnet, September 4, 2017.

Skip to content

Skip to content