Abstract: The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime to the forces of Hayat Tahir al-Sham (HTS) revealed the ongoing significance of multiple foreign fighter groups in Syria. These militias were instrumental in supporting HTS during its campaign for Damascus last fall. Two primarily ethnic Uzbek fighter groups that originated in Central Asia were prominent among them: the Imam Bukhari Battalion (Katibat Imam al-Bukhari, KIB) and the Tavhid and Jihad Battalion (Katibat Tavhid va Jihod, KTJ). Each had pledged allegiance to al-Qa`ida and fought alongside al-Qa`ida’s Syrian branch Jabhat al-Nusra. Each remained closely connected to al-Qa`ida even after al-Nusra rebranded as HTS. This article traces the origins and development of these Uzbek-led militias and argues that they constitute a resilient force of battle-hardened fighters, demonstrating remarkable staying power in Syria. Furthermore, this article demonstrates that KIB and KTJ still embrace a salafi-jihadi ideology and goals. It also emphasizes KIB’s and KTJ’s ongoing ties to al-Qa`ida and the Taliban and recommends that policymakers and counterterrorism experts consider the implications of their continued presence in Syria under the new regime, as well as the potential consequences if they leave Syria.

The fall of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024 revealed the ongoing significance of multiple foreign fighter organizations in Syria, groups that proved instrumental in Hayat Tahir al-Sham’s (HTS) campaign for Damascus. Among them were two primarily ethnic Uzbek fighter groups that originated in Central Asia: the Imam Bukhari Battalion (Katibat Imam al-Bukhari, KIB) and the Tavhid and Jihad Battalion (Katibat Tavhid va Jihod, KTJ). Smaller numbers of Uzbeks and other Central Asians joined Malhama Tactical, Muhojir Tactical, and Katibat al Ghuraba al Turkistan, which also supported HTS.1 a HTS voiced no objections as these organizations’ leaders gave media interviews in Damascus, celebrating their victory, and posted images of their involvement across dozens of social media channels. These Uzbek-led groups are among some 10,000 fighters, many from Russia and China, who lent critical support to HTS for over a decade.2 In spring 2025, HTS emir Ahmed al-Sharaa proposed integrating such foreign fighters into the new Syrian military, a process that has now begun.3 Yet, little is known about these entities, why and how they have operated in Syria for so long, or what role they might play in the post-Assad Syria.

This article examines the two main Uzbek militias, KIB and KTJ. It argues that they constitute resilient and battle-hardened fighter groups whose ties to al-Qa`ida and the Taliban have endured. KIB and KTJ still embrace a salafi-jihadi ideology and goals even though HTS claims to have rejected its former al-Qa`ida ties, aims, and ideology. It is therefore important to consider the implications of their continued presence in Syria, as well as the consequences should they leave.

The Syrian War, Foreign Fighters, and Central Asians

The Syrian civil war created an environment for a massive influx of foreign fighters. President Assad’s killing of anti-regime protesters during the Arab Spring and his use of chemical weapons in the civil war that soon erupted sparked unprecedented anger among Muslims worldwide.4 Al-Qa`ida was quick to enter the fray. Al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI) recruited thousands of foreign fighters to Syria and Iraq. By 2014, this movement had declared itself “the Islamic State” (ISIS or ISIL) and its territorial conquest the new caliphate. Meanwhile, al-Qa`ida had also directed the Syrian fighter Ahmed al-Sharra (known until December 2024 by his nom de guerre Abu Muhammad al-Julani, now Syria’s interim president) to establish a local, Syrian branch of al-Qa`ida,5 known as Jabhat al-Nusra as of January 2012. Jabhat al-Nusra also attracted foreign fighters, including several organizations previously waging jihad in Afghanistan.6 In fact, most foreigners joined or affiliated with either the Islamic State or Jabhat al-Nusra (which later split with al-Qa`ida, rebranded, and formed HTS). As Vera Mironova has shown, foreign fighters needed a local patron, even if they maintained organizational independence.7

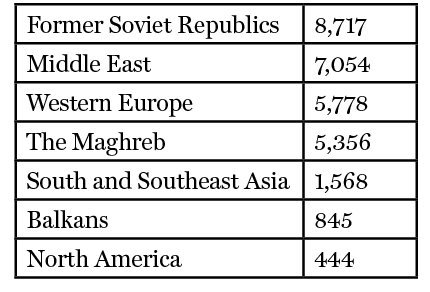

Unprecedented in scope, these foreign fighters exceeded 40,000 in number by 2016. They arrived from 110 countries and accounted for about 40 percent of all combatants.8 In January 2015, ICSR estimated citizens from Central Asia fighting in Syria and Iraq to be about 1,400, including some 500 Uzbeks.9 By 2017, as shown in Table 1, it was believed that almost one-third of foreign fighters were nationals of ex-Soviet republics, particularly from Central Asia, the Caucasus, or Russia.

Table 1: Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq by Region (2017)10

Later figures suggest that 5,000-6,000 Central Asians joined the jihad.11 Thousands of others likely attempted to join but were stopped en route in Turkey.12 Since Central Asians often traveled to Syria after working as labor migrants in Russia,13 some were counted as “Russian;” the actual number of Central Asians was likely higher than reported. Comparative data on fighters per million Muslim citizens in each country shows that Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Russia each produced more fighters than Egypt, Algeria, or Turkey.14 Among foreign fighters, Uzbeks gained a reputation for being particularly skilled.15

The exact breakdown between fighters joining the Islamic State versus al-Qa`ida is unknown. However, Central Asian fighters in Syria typically subdivided into militias along ethnic lines. Tajiks mostly joined the Islamic State.16 Russian-speaking fighters, including Chechens, affiliated with both the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra.17 Based on the author’s research, Uzbek and Uyghur-led groups, supplemented by some Kyrgyz and Tajiks, organized groups more typically affiliated with Jabhat al-Nusra.

Two of the main foreign fighter groups from ex-Soviet states have been the predominantly Uzbek KIB (500) and KTJ (500), which in turn have been supported by smaller Uzbek-led groups, Malhama Tactical and Muhojir Tactical.b Albeit not as large in number as the predominantly Uyghur TIP (about 3,500), they have been sufficiently sizable to play a role inside Syria and potentially beyond. Although these groups received little attention, in part because they were deemed too small to be of consequence, it is notable that about the same number or fewer foreign fighters played notable roles in the Russian-Chechen wars (200-700, 1994-2009), Bosnia (1,000-3,000, 1992-1995), Somalia (250-450, 1994-2014), and Afghanistan (2001-2014, 1,000-1,500).18

Moreover, these Uzbek-led groups and other Central Asians were well-trained, hardened, and resilient. The Soufan Center estimated that by October 2017, 30 to 50% of fighters from European Union states had gone home, as had 27% of Tunisians and 23% of Saudis.19 By contrast, only 11% of Russian nationals and fewer than 10% of Central Asians had left.20 According to Nodirbek Soliev’s 2021 dataset, of the total Central Asian fighters recorded, 39% were detainees, 29% were killed, and 32% remained at large. By 2021, 1,301 of 2,200 Central Asian detainees were repatriated,21 including 531 Uzbeks.22 Since most detainees were Islamic State-affiliated, the remaining 32% (approximately 1,600 fighters) were likely affiliated with al-Qa`ida or HTS.23 They included 1,300 Uzbeks. Their ongoing mobilization highlights the need for further investigation into KIB and KTJ, whose roots lie in Central Asia.

Uzbek-Led Foreign Fighter Organizations in Syria

The domestic political context in Central Asia was a major factor driving Uzbeks and other Central Asians to Syria. Central Asian groups in Syria had roots in both grievances and salafi-jihadi ideologies that predated Syria’s war and the rise of the Islamic State. In fact, their roots trace back to a long history of Islamic opposition to the USSR, opposition that radicalized over time—especially after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the subsequent crackdowns on mosques, Islamic study, and Islamist activism by post-Soviet regimes in the 1990s and 2000s. State suppression of independent Islam was most brutal in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, but was felt in other republics as well, where conservatively religious minorities were most targeted.24 Religious and political injustice, in addition to widespread economic hardship and corruption, pushed Central Asians to Syria.

Yet, KIB and KTJ fighters took different routes to Syria’s jihad. KIB fighters mostly went through Tajikistan and Afghanistan, where they had fought previously with an earlier Islamist opposition, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU).25 Many KTJ members came from Kyrgyzstan, often after migrant labor work in Russia or Turkey.26 Others came from the Islamic Jihad Union (IJU) in Afghanistan. Nonetheless, both KIB and KTJ intertwined national grievances and aims with al-Qa`ida’s transnational goals in Syria.

Katibat Imam al-Bukhari (The Imam Bukhari Battalion)

Origins and Development

Established by the IMU, KIB became one of the earliest, largest, and most significant of the Central Asian foreign fighter groups in Syria. KIB’s ties to al-Qa`ida and the Taliban predated 9/11 and have continued through 2025.

KIB was the culmination of the IMU’s shift from local to transnational jihad. In the 1990s, the IMU’s ideology was militant Islamist, but its goal was nationalist; it declared jihad against Uzbekistan to overthrow its president, Islam Karimov, and create an Islamic state.27 Sheltered by the Taliban, who allowed it to establish a base camp in Afghanistan, train, and recruit, the IMU pledged allegiance to Mullah Omar.28 The IMU fostered Taliban control by filling governance roles in non-Pashtun regions of Afghanistan.29 Its relationship soon involved connections to al-Qa`ida as well. Shortly after 9/11 and the launch of the U.S. war in Afghanistan, IMU fighters were taken prisoner along with Arab and other al-Qa`ida foreign fighters at Qala i-Jangi fort.30 The IMU soon began fully supporting the Taliban and al-Qa`ida against the United States, as did the IJU, which splintered from the parent movement.31

For over a decade, the IMU and IJU operated from the Pakistani frontier of North Waziristan, sheltered by and intertwined with the Haqqani network, as well as al-Qa`ida.32 They developed ties to the Uyghur East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM/TIP) and the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).33 By 2014, the IMU and IJU operated jihadi training and suicide camps and built IEDs and VBIEDs. They coordinated attacks with the Haqqani network and the TTP, striking U.S. and ISAF forces, the Afghan National Army and government, and the Pakistani security services and government.34 IMU and IJU statements, propaganda, and targets indicated that they had fully adopted al-Qa`ida’s salafi-jihadi ideology.35 They recruited transnationally, and the IJU plotted attacks in Europe.36

Between 2011 and 2013, the jihadi network in North Waziristan gave birth to the KIB. IMU leaders and Sirajuddin Haqqani, head of the Afghan Haqqani network and an influential deputy leader of the Taliban, appear to have been instrumental in this process.37 An early proponent of the ideology of global salafi-jihadism, the Haqqani network was notorious for orchestrating high-profile attacks against U.S. and ISAF forces, embassies, government targets, and the Intercontinental Hotel in Afghanistan.38 It had close ties to al-Qa`ida and had long abetted global jihadis. Akmal Jo’raboyev, who as a high-ranking IMU commander had collaborated in operations with Haqqani’s network, was designated KIB’s first emir.39

Creating the KIB was an entrepreneurial and strategic move. The IMU’s chances of success within Afghanistan, much less against Uzbekistan, seemed slim. The Taliban were facing a U.S. surge of troops. By contrast, in Syria, salafi-jihadism was gaining ground, the United States was then disengaged, and al-Qa`ida needed reinforcements to compete with the Islamic State.

KIB Operations in Syria

By early 2014, the IMU had sent 100-200 fighters to Syria, near Aleppo, under Jo’raboyev, who adopted the nom de guerre Salahadin al-Uzbeki.40 Almost unique among such groups, KIB would remain an independent militia in Syria through 2025.

For Central Asian aspiring militants, KIB became a viable alternative to joining the IMU or IJU in Afghanistan, which had achieved little success in establishing an Islamic state, despite two decades of fighting. Employing both social media propaganda and networking, KIB effectively recruited and sustained itself from 2013 through 2025, expanding to about 500-1,000 fighters.41 When the U.S. Department of State listed KIB as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) organization in 2018, it described it as the largest Uzbek fighting force in Syria and Iraq.42

KIB also had a pipeline of fighters for the future. It reportedly ran its own madrasa in Turkey for younger recruits and the children of its fighters; they studied ideology and religion under a radical Uzbek imam, a Ferghana Valley émigré, until they were old enough to join KIB camps. The group gained notoriety for using child soldiers after it broadcast a video depicting children firing weapons in one of its training camps.43

KIB’s force actively cooperated with early foreign fighter groups, especially Russian speakers from ex-Soviet states. Given its close connection to al-Qa`ida in Afghanistan, KIB affiliated with Jabhat al-Nusra as of 2015, and even recruited for it.44

KIB was among the more skilled, battle-hardened, and well-equipped fighter groups in Syria. It operated at least two training camps that taught martial arts, rifle and sniper skills, raids, bomb-making, and other small arms tactics to Central Asians as well as to Syrians under Jabhat al-Nusra.45 Photographs and videos posted in social media showcased the group using heavy mortars and trucks mounted with Soviet-made anti-aircraft twin-barreled autocannons, as well as both light and heavy machine guns, mostly Soviet, East German, or Romanian models.46 KIB’s arsenal also included multiple launch rocket systems, anti-tank missile systems, and heavy artillery guns.47

KIB played a significant role in Jabhat al-Nusra’s campaigns from 2015 to 2016. It participated in the rebel offensive to capture and hold Idlib in 2015, and during the prolonged, ultimately unsuccessful offensive in and around Aleppo in 2016.48 KIB fought against Assad’s forces in Latakia province as well in 2016. In spring 2018, KIB reportedly commanded about 500 fighters based in Khan-Shaykhun, with an operational zone spanning the provinces of Idlib, Aleppo, and Hama.49 In addition to fighting Assad’s forces, KIB also attacked the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) in Aleppo.50

Although it never joined HTS, KIB maintained good relations with al-Sharaa and closely coordinated with HTS’ umbrella of Syrian rebels and foreign forces to engage the regime in battles in northern Hama in 2019 and inside Idlib province in 2020 as the conflict escalated. In addition to supporting HTS operations, KIB also participated in the “Incite the Believers” operations room and campaign, which involved several jihadi groups operating in northern Syria, such as al-Qa`ida loyalist Hurras al-Din.51 Al-Qa`ida’s media strongly promoted the campaign.

After the 2020 ceasefire in Idlib, KIB appeared largely dormant for several years. Some suggested it had splintered, but reports of its demise were premature. It reemerged with strength as part of HTS’ campaign in fall 2024 (see below). That HTS tolerated KIB’s independence, even while forcing other groups under its authority, was a testament to its strength and contributions to fighting the Assad regime.

KIB’s Unbroken Allegiance to al-Qa`ida and the Taliban

Throughout the Syrian conflict, KIB maintained its allegiance to al-Qa`ida, even as some foreign fighters defected to the Islamic State. KIB reaffirmed its oath to the Taliban in late 2014, despite the IMU’s 2014 betrayal and pledge to join the Islamic State. KIB’s commitment to Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qa`ida’s front in Syria, was manifested during operations in Idlib and Aleppo. KIB fighters endured relentless aerial bombardments by both Putin and Assad. Islamic State-controlled areas, by contrast, were not carpet-bombed. In a propaganda video released in 2016, KIB reaffirmed its al-Qa`ida ties by honoring Usama bin Ladin and other al-Qa`ida martyrs. Its social media channels regularly shared images and videos of its weapons and ambushes in Afghanistan to demonstrate its ongoing ties to the Taliban.52

KIB adeptly negotiated Jabhat al-Nusra’s break with al-Qa`ida in late July 2016, a split allegedly driven by Jabhat al-Nusra’s desire to focus solely on Syria and the anti-Assad campaign.53 c KIB maintained its long-standing relationship with al-Sharaa and did not challenge his authority, but never publicly renounced its oath to al-Qa`ida and cooperated with Hurras al-Din.

KIB never joined HTS in abandoning global salafi-jihadism. Nor did it sign a declaration of support to HTS as did many other foreign fighter groups in 2019, including KTJ, the Turkistan Islamic Party, and Jaysh al-Muhajireen wa al-Ansar.54 Probably to appease HTS and avoid U.S. targeting, KIB downplayed its pursuit of global jihad, denied employing terrorism, and contested the U.S. government listing it as an SDGT. KIB proclaimed itself “volunteers defending the oppressed Syrian people” against Russia, Iran, Assad, and the Islamic State.55

KIB’s statements have demonstrated its commitment to salafi-jihadi ideology, even with generational change in leadership. After Salahadin’s assassination, KIB’s new, young emir, Abu Yusuf Muhojir, remained close to al-Qa`ida and the Taliban. For example, in 2018, Muhojir responded to U.S. recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital on Telegram by calling for: “protect[ing] the Muslim sanctuary of Jerusalem from the Jews and Crusaders;” Muhojir further endorsed the “protection of the Palestinians and jihad against the godless regimes of Western countries, and [called] for the Muslims of Central Asia to join the jihad as the only way to resist the aggression of the U.S. and its Zionist allies.”56

Like al-Qa`ida, both KIB’s Syrian and Afghanistan branches renewed their allegiance to the Taliban when Mullah Akhundzada was appointed emir in 2016. The latter has wielded draconian control over Afghanistan since 2021 and continues to justify militancy in creating what he calls a “pure” Islamic state.57 KIB identified itself on social media as the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan – Katibat Imam al Bukhari,” the Taliban’s state’s official name.58

From HTS-controlled Idlib, KIB had sent dozens of fighters back to Afghanistan. The Taliban’s resurgence as U.S. troop levels declined offered KIB militants an alternative base of operations and a potential haven if Idlib fell to Russian-backed Assad forces or if intra-jihadi conflicts in Syria made Afghanistan more attractive. In 2018, KIB fighters were deployed to northern Afghanistan (Faryab, Baghdis, Badakhshan, and Jowzjan provinces) to establish training camps for new recruits. The United Nations Security Council reported that KIB had 80-100 fighters there.59

In February 2020, when the Trump administration agreed to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan, Muhojir congratulated the Taliban on “victory.” KIB continued posting Telegram videos and photos of KIB training and joint operations, one showcasing the capture of Afghan government soldiers in joint attacks with the Taliban.d Even though the Taliban claimed to have broken ties with al-Qa`ida-linked groups, it made no attempt to evict KIB or al-Qa`ida. Shortly after August 2021 and the fall of Kabul, Muhojir praised the Taliban for its defeat and humiliation of the United States and NATO.60 Muhojir’s public missive ended with a “Poetic Gift to our Islamic Emirate from the Mujahideen of the Imam Bukhari Battalion, the soldiers of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in Syria.” The poem celebrated “my Taliban” in victory over the “infidels” and “crusaders,” from Russia to the United States; he claimed it a victory “for the whole Islamic Ummah.”61

Although it remained in Idlib, KIB was strategically positioned to operate in either Syria or Afghanistan, or both. In 2024, it would join HTS in toppling Assad.

Katibat al-Tawhid wal Jihad (The Battalion of Monotheism and Jihad)

Origins and Development

KTJ has been another predominantly Uzbek foreign fighter group, fighting first in alliance with al-Qa`ida’s Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria, and later with HTS. KTJ was founded in 2014 by Sirojiddin Muxtorov, an ethnic Uzbek-Uyghur citizen of Kyrgyzstan. He hailed from the village of Kashkar-Kyshtak, near Kara-Suu in the Osh region of the Ferghana Valley. The area was home to large Uzbek and Uyghur minorities within Kyrgyzstan. Over the previous decade, Muxtorov had become radicalized due to the religious and political repression perpetrated by both the Kyrgyz and Uzbek governments. Both regimes branded strict religious practice—common among Uzbeks, Uyghurs, and Ferghana Valley residents—and discussion of politics within mosques as “extremism.” Sentences against those labeled extremists were lighter in Kyrgyzstan, but human rights abuses and torture in detention centers outraged many. Additionally, both regimes closely collaborated with China to monitor and incarcerate Uyghurs.62

Muxtorov attended the Kara-Suu mosque, located near the Kyrgyz-Uzbek border, and was close to the family of the mosque’s revered imam, known by the honorific Rafiq Qori. The latter, an ethnic Uzbek, had gained widespread prominence from his underground teaching of Islam during Soviet times and his activism in reviving Islam through Arab connections. In the mid-1990s, Uzbekistan’s security services had arrested Rafiq Qori’s relatives for salafi preaching, and in 2005, had massacred hundreds of protesters in the Ferghana Valley. In 2006, a joint operation by Uzbekistani and Kyrgyzstani security services killed Rafiq Qori, whom they accused of having IMU connections.63

That same year, Muxtorov began Islamic studies with Rafiq Qori’s son, who assumed leadership of the Kara-Suu mosque. Sharing his father’s puritanical interpretations, Rashod Qori continued his Arab connections and also indirectly supported the pro-caliphate movement Hizb ut-Tahrir.64 A regime change in Kyrgyzstan in 2010 amplified repression by triggering deadly pogroms against ethnic Uzbeks, and then prosecuting Uzbeks for the unrest.65 Rashod Qori was among those routinely threatened. Ultimately arrested, in 2015, he received a 10-year prison sentence. Outraged followers staged mass protests, as they had upon his father’s killing.66

After several years under Rashod Qori’s mentorship, Muxtorov went to Syria to continue his studies at the Islamic University of Al-Fatah al-Islamiya. There, he studied the works of Taqi al-Din Ahmad Ibn Taymiyyah, Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, and Sayyid Qutb, major figures in the development of salafi-jihadi ideology. Muxtorov reportedly also adopted the ideas of al-Qa`ida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri.67 As the Syrian war developed, Muxtorov began advocating Muslim unity and each Muslim’s duty to carry out jihad. He returned to Kyrgyzstan to serve as an assistant imam at a Kara-Suu mosque, but left again for Syria in 2012.68

Muxtorov took the nom de guerre Abu Saloh al-Uzbeki and joined KIB. Respected as a skilled orator and religious scholar, he rose through the ranks. After being wounded in the eye and treated in Turkey, he returned to Syria in fall 2014 to lead an independent group of Central Asian fighters. Initially called the Janaat Oshiklari (the Lovers of Paradise), the group included his own recruits as well as Uzbeks and Uyghurs who had previously fought with KIB and TIP.69 Active on social media, Janaat Oshiklari gained followers and evolved into KTJ (the Battalion of Monotheism and Jihad), a name reminiscent of Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi’s early foreign fighter group in Iraq.

KTJ Operations in Syria, Russia, and Central Asia

KTJ’s membership grew to an estimated 500 fighters.70 Muxtorov used both extensive social media platforms and personal networks, both in the Ferghana Valley and among migrant laborers, to recruit fighters and financiers. His videos and audio sermons on YouTube and Telegram, although removed now, suggested that the charismatic Muxtorov had thousands of online followers. Aravan and the surrounding districts in Kyrgyzstan’s Ferghana Valley, Muxtorov’s homeland, were a “hot spot,” supplying 33% of Kyrgyzstan’s several hundred foreign fighters in Syria.71

The Uzbek-led Islamic Jihad Union (IJU) in Afghanistan, another ally of al- Qa`ida, the Haqqani network, and the Taliban, reportedly sent fighters to join KTJ and aid in training.72 Assistance from KIB also helped KTJ to become one of the most formidable and durable foreign fighting groups in Syria. KTJ’s voluminous propaganda regularly showcased its combat training, weapons, and participation in numerous offensives from 2014 through 2025, as well as its emir’s Islamic teachings.73

KTJ collaborated with KIB, TIP, and Russian-speaking groups from the Caucasus (including Chechens and Azeris). Like these groups, and the IJU, KTJ became closely affiliated with Jabhat al-Nusra, which in 2014 was still al-Qa`ida’s Syrian front. In a 2015 video posted on his YouTube channel, Muxtorov pledged an oath to Jabhat al-Nusra and Ayman al-Zawahiri.74 That public move set KTJ, like KIB, apart from the thousands of foreign fighters then joining the Islamic State.

Over the next few years, KTJ operated mainly in northwest Syria, engaging in combat with Assad’s forces and his backers, which included Russian PMCs and air power, and Iran’s Quds force. Muxtorov’s unit fought in the successful campaign to capture Idlib province.e KTJ also fought in the long and bloody siege of Aleppo, Jisr al- Shughur, and Latakia in 2015-2016.75 It regularly released photos of its operations, showcasing equipment similar to that used by KIB.76 In 2019, it joined rebels in battles around northern Hama, again posting images of its operations.77

KTJ became known for its combat skills and experience. It served in specialized roles, providing Inghimasi shock troops, sniper squadrons, and trainers in the use of Soviet and East European-made weapons, captured from the Syrian Army or bought on the black market. On one occasion at least, KTJ used a VBIED.78 Dozens of propaganda images showed KTJ’s weapons; one showed its fighters learning to operate a U.S.-made TOW anti-tank guided missile.79

KTJ’s operations reflected its salafi-jihadi goals. The apostate regimes of Central Asia and also Russia were its targets. Like Chechen groups and al-Qa`ida, KTJ had a virulent anti-Russian agenda. In addition to supporting Jabhat al-Nusra through sustained Russian bombing campaigns, Muxtorov emphasized KTJ’s commitment to bringing militant jihad back to Russia and its Central Asian allies. KTJ allegedly orchestrated a suicide bombing in St. Petersburg’s metro in April 2017, during President Putin’s visit; 14 were killed and 50 injured, according to U.S. government sources.80 Muxtorov’s targeting of Russia triggered a backlash by the Russian security services against ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbek labor migrants. The Russian Ministry of Defense claimed to have killed Muxtorov in 2022.81

In alliance with oppressed Uyghurs in both China and the Ferghana Valley, KTJ also regarded China as an enemy of Muslims. Muxtorov reportedly ordered the August 2016 terrorist attack on the Chinese Embassy in Kyrgyzstan. The suicide car bomb attack was carried out by a Kyrgyzstani KTJ member, possibly with TIP support.82

Although coming under HTS control in 2019, KTJ still maintained its militia’s organization and identity. It was observed at the frontlines in Jebel al-Zawiyah, near the Aleppo-Idlib border at al-Atarib, and in the Latakia mountains between 2019 and 2022.83 Following other fighter groups, KTJ also spawned a tactical group, allegedly of elite fighters and trainers; Muhojir Tactical released its manifesto online on November 16, 2022. It posted videos in Russian and Uzbek, showcasing its training and calling for jihad on multiple Telegram channels, Instagram, and TikTok.84 Muhojir Tactical’s founder, Ayyub Hawk, was an ethnic Uzbek who had fought in Syria since 2015. He claimed to be motivated by the duty to defend Muslims against the genocidal Kyrgyzstani, Russian, and Syrian regimes.85

KTJ’s Salafi-Jihadi Ideology and al-Qa`ida

From its founding, KTJ was shaped by Muxtorov’s adherence to salafi-jihadi ideology. In September 2015, KTJ answered Ayman al-Zawahiri’s call for all Muslims to unite in jihad against the West and Russia by declaring an oath of loyalty to al-Qa`ida central and its Syrian branch, Jabhat al-Nusra.86 KTJ portrayed itself as committed to al-Qa`ida’s global movement, with a mission to draw Central Asians into the global ummah by waging jihad in Syria first, and later, in Central Asia.

Compared to KIB, both Muxtorov and his successor as KTJ’s religious ideologue, Sheikh Ahluddin Navqotiy, produced and broadcast dozens of religious “lessons,” in which they promoted strict interpretations of sharia, covering topics from marriage and child-rearing to prayer and politics. They condemned secularism, idolatry, and polytheism. Their audio and video sermons emphasized an individual’s duty to wage jihad and reestablish the caliphate, lionized Abdullah Azzam, Usama bin Ladin, and other al-Qa`ida leaders, and praised the mujahideen in Afghanistan and Syria.87 They advocated jihad against Israel, defense of the Palestinians, fighting against infidels, and martyrdom. They condemned dividing Muslims by nationality, region, or national borders, praised the virtues of the caliphate, denounced apostate Central Asian regimes, Russia, China, and the United States, and decried Russian carpet-bombing and Wagner’s war crimes in Syria.

KTJ’s statements supporting global jihad, beyond Syria, further revealed its transnational ideology and allegiance to al-Qa`ida. Like KIB, KTJ responded to the U.S. recognition of Jerusalem by aligning with al-Qa`ida; Muxtorov called for “Muslims of the world to free the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem from the Jewish occupation.”88

Even after Jabhat al-Nusra broke from al-Qa`ida and rebranded as HTS, Muxtorov and KTJ remained loyal to al-Qa`ida for several years. As a consequence, in spring 2019, when al-Sharaa forced KTJ under HTS, Muxtorov was removed. Together with several dozen KTJ members, the former emir defected and began affiliating with Jabhat Ansar al-Din and Hurras al-Din, both groups loyal to al-Qa`ida. Apparently in retribution, HTS’ internal security forces arrested Muxtorov in 2020 and detained him for several months.f

HTS did not fully sever the ties between KTJ and al-Qa`ida or the Taliban. KTJ’s new emir, an Uzbek named Ilmurad Khikmatov, went by Abdul Aziz al-Uzbeki; he was a respected 20-year veteran of the IJU in Afghanistan. Abdul Aziz avoided open defiance of HTS in his rhetoric. However, KTJ’s salafi-jihadi ideology remained unchanged. Its leaders still promoted the idea of an Islamic state, the obligation of jihad against infidels, and martyrdom.89 “Abu Saloh” audio and video lessons and propaganda were reposted under multiple other channels and names.

KTJ continued cordial relations with the Taliban as well, which it praised as a model state.90 In 2021, KTJ’s leaders praised the Taliban (in Uzbek, Pashto, and Dari) for victory “over the most powerful evil empire in the world.”91 KTJ retained close ties to the IJU, which had an estimated 200 to 250 members, mostly in northern Afghanistan.92

Unlike the IMU, the IJU had remained loyal to al-Qa`ida and the Taliban, and presented itself as fully supportive of and integrated into Taliban rule.93

In October 2023, following Hamas’ terrorist attack on Israel, KTJ followed al- Qa`ida and the Taliban in declaring support for Palestinians and a jihad against Jews. Multiple KTJ videos urged mujahideen worldwide to sacrifice their lives to liberate Jerusalem.94 They emphasized that “this was a war between Islam and the American- Zionist allies.”95 Abdul Aziz merely included the caveat that KTJ fighters remained committed to Syria. HTS had also proclaimed support for the Palestinians and compared Israeli strikes on Gaza to Russian strikes in Syria.96

KTJ has never disavowed its commitment to jihad against the Central Asian regimes, Russia, and China. Yet, Abdul Aziz pragmatically stated that KTJ has not, and will not, engage in terrorist activity.97 To remain active in Syria, KTJ needed to align with HTS’ desire to be removed from the U.S. terrorist list.

KIB, KTJ, and HTS: At a Turning Point in 2024-2025

With HTS controlling most of Idlib, the war with Assad’s regime at a stalemate, and the catastrophic 2023 earthquake disrupting communication, little was known about either KIB’s or KTJ’s operations from 2021 through early 2024. The United Nations Security Council reported that KIB and KTJ each maintained a force of several hundred in Syria, as well as hundreds in Afghanistan. Their social media propaganda for recruiting and fundraising continued.98

In fall 2024, HTS planned a new campaign to overthrow Assad. HTS’ Al-Fath Al- Mubin Operations Room, the military command center for coordinating and conducting operations,99 included KIB, KTJ, and the Uzbek tactical groups, among other foreign fighters. It launched “Operation Deterrence of Aggression” on November 27, 2024. The campaign ended quickly, with the fall of the 53-year Assad dictatorship on December 8. As Uzbek and other fighters celebrated, KIB emir Muhojir announced on social media that their victory revealed the “divine power of the Almighty.”100 Photos and footage of the operation were disseminated on multiple channels by KIB supporters; one had over 38,000 views.101 Ayyub Hawk, Muhojir Tactical’s leader, gave a television interview extolling MT’s role in taking Aleppo and talking about the coming conflict with Israel.102 KTJ’s emir Abdul Aziz stood near the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, where he proclaimed that the “descendants of al-Bukhari (Central Asians) had fulfilled” their duty to the caliphate. Over 14,000 viewed the video, many posting effusive praise. One follower commented: “May the mujahideen be pleased with their paradise and may they be blessed.” Although KIB and KTJ’s social media following had taken a severe hit since being branded SDGTs, these Uzbek groups nonetheless stood to benefit from the victory. Moreover, their public statements suggested that HTS valued their contribution.

Recent steps by HTS are indicators of the importance al-Sharaa places on foreign fighters, who comprised up to 30% of HTS forces in overthrowing Assad.103 This spring, HTS announced its decision to integrate foreign fighters into the new Syrian military.

Hardened fighters, such as the Uzbeks, Uyghurs, and Chechens remain a valuable asset. Malhama Tactical is already training the new Syrian army and special forces.104 To retain these al-Qa`ida-linked groups, HTS was willing to defy the Trump administration’s demand that they be expelled.105 g In doing so, HTS also risks losing the support of mainstream Syrians, who view foreign militants as extremists, especially given multiple allegations that foreign fighter groups (albeit not specifically Uzbeks) have perpetrated violence against civilians.106

Conclusion: Potential Scenarios for Uzbek Foreign Fighters in Syria

This analysis of the origins, long-term trajectory, and uncertain future of KIB and KTJ has several important implications for policymakers seeking to address Syria, Central Asia, and global salafi-jihadism.

First, their ability to survive over a decade of the Syrian conflict and their pivotal role in the HTS coalition that contributed to overthrowing the Assad regime demonstrate that these Uzbek groups are highly skilled and resilient fighting forces. HTS likely aims to maintain the capabilities of its new military and security forces. To do so, al-Sharaa has already appointed foreign militia leaders to prominent military positions; among those appointees are a Tajik citizen who recruited Central Asians to Syria, three ethnic Uyghurs from China, and Turkish and Jordanian nationals.107 However, experience in Afghanistan and other areas has shown that integrating previously autonomous foreign fighters and diverse ethnic groups into a centralized, hierarchical military is a long-term process fraught with challenges.

Second, integration will be particularly challenging given that KIB boldly, and KTJ more subtly, maintained their allegiance to both al-Qa`ida and the Taliban. As has been seen, their salafi-jihadi ideology has remained unchanged during decades of fighting. It is unlikely that they will abandon either building an Islamic state or their larger, long-term goal of bringing down regimes in Russia, Central Asia, Israel, and the United States. Integrating these groups into a Syrian regime and military that has abandoned global jihad and the opportunity to establish an Islamic state either forebodes ideological conflict or requires significant ideological moderation.

Third, HTS could ultimately decide to exclude KIB, KTJ, and other foreign fighter groups from the new military and perhaps even from Syrian citizenship—whether because al-Sharaa sees them as threatening his control or because of U.S. criticism over al-Qa`ida ties. While President Trump has temporarily backed down from demanding the expulsion of all “foreign terrorists” from Syria, the United States could reimpose sanctions if periodic reviews show that Syria is failing to meet expectations.108 If expelled, or if they decide to leave for other reasons, foreign fighters will have several options.

Most likely, KIB and KTJ would migrate to Afghanistan, where they have maintained a small force connected to the IJU and a base of operations. Their unbroken pledge to the Taliban and long-standing ties to the Haqqani network, which gained strength after the fall of Kabul in 2021, would support this regional move. From there, they could join the Taliban’s Emirate, continue attacks on Central Asian regimes, or target Pakistan. The political and religious conditions that originally fueled the Islamist opposition within former Soviet Central Asia remain largely unchanged. In this scenario, both the Central Asian countries and U.S. interests in the region would face an increased threat. An alternative would be for KIB and KTJ to join al-Qa`ida factions in other parts of the Middle East or Africa. KIB and KTJ fighters, especially their tactical groups, might become “road warriors,” similar to Afghan-Arabs after the mujahideen’s victory over the USSR, fomenting jihad elsewhere.

While Assad’s overthrow is a victory against dictatorship, uncertainty rather than stability and democracy has replaced his rule. HTS’ break with al-Qa`ida was a setback for the latter in Syria, but it is too early to dismiss al-Qa`ida’s influence altogether. None of the options above is desirable from a counterterrorism standpoint. The United States and Central Asian countries should carefully consider and prepare for each possibility. CTC

Dr. Kathleen Collins is the Arlene C. Carlson Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota. She is author of Politicizing Islam in Central Asia: From the Russian Revolution to the Afghan and Syrian Jihads (Oxford University Press) and Clan Politics and Regime Transition in Central Asia (Cambridge University Press). She has presented her research to various U.S. government agencies, NATO partner militaries, the Helsinki Commission, the UNDP, and other organizations.

The author is grateful to Captain Chris Borg, Mike Croissant, Edward Lemon, Thomas F. Lynch, Damon Mehl, Mariya Omelicheva, and Noah Tucker for advice on this project.

© 2025 Kathleen Collins

Substantive Notes

[a] Malhama disappeared for a time and was thought to be absorbed into HTS after its founder died in 2019, but it regrouped in 2024. See Daniel Garofalo, “Malhama Tactical is Back!” Daniele Garofalo Monitoring, January 28, 2025.

[b] Note that estimates of these foreign fighter group memberships have fluctuated, with membership declining over time due to battle losses. Current estimates of remaining fighters in Syria are from “Katiba Imam al-Bukhari (KIB),” United Nations Security Council, n.d. and “Khatiba al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (KTJ),” United Nations Security Council, n.d. Additional KIB and KTJ fighters are in Afghanistan (see below). On Malhama Tactical and Muhojir Tactical, see “Militant Enterprises: The Jihadist Private Military Companies of Northwest Syria,” Syria Justice and Accountability Centre, May 9, 2024. Some reports likely overestimate these PMCs’ capabilities. See Rao Komar, Christian Borys, and Eric Woods, “The Blackwater of Jihad,” Foreign Policy, February 10, 2017.

[c] Some sources doubt a full split actually took place. See Jennifer Cafarella, “Avoiding al-Qa`ida’s Syria Trap: Jabhat al- Nusra’s Rebranding,” Institute for the Study of War, July 28, 2016.

[d] KIB’s own channel was regularly removed from Telegram, but Muhojir and other supporters continued to post evidence of their presence. Caleb Weiss, “Taliban attempts to cover up images posted by an Uzbek jihadist group in Afghanistan,” FDD’s Long War Journal, July 8, 2020.

[e] The Russian-language Golos Shama (“Voice of Sham”) published an interview with Saloh on January 29, 2018. It was translated by Joanna P. Paraszczuk and posted on the blog “From Chechens to Syria” on February 2, 2018.

[f] Various reasons have been given for Muxtorov’s arrest. See Uran Botobekov, “Top Uzbek Jihadist Leader Suffers for Loyalty to Al Qaeda,” Modern Diplomacy, July 10, 2020.

[g] The administration subsequently pulled back its demand that foreign fighters be expelled.

Citations

[1] Caleb Weiss, “New Uighur jihadist group emerges in Syria,” FDD’s Long War Journal, January 18, 2018.

[2] Omar Abdel-Baqui, “Foreign Jihadists Helped Syria’s Rebels Take Power. Now They’re a Problem,” Wall Street Journal, April 30, 2025.

[3] Raia Abdulrahim, “They Went to Syria to Fight With Rebels. Now Some Are Joining the New Army,” New York Times, June 8, 2025.

[4] Fawaz Gerges, ISIS: A History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

[5] Brian Fishman, The Master Plan: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and the Jihadi Strategy for Final Victory (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016); Charles Lister, The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 51-57.

[6] Lister, p. 59.

[7] Vera Mironova, From Freedom Fighters to Jihadists: Human Resources of Non-State Armed Groups (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 101, 118.

[8] Alex Schmid, “Foreign (Terrorist) Fighter Estimates: Conceptual and Data Issues,” Policy Brief, ICCT, October 27, 2015.

[9] Peter Neumann, “Foreign Fighter Total in Syria/Iraq Now Exceeds 20,000,” International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, January 26, 2015.

[10] Richard Barrett, “Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees,” Soufan Center, October 2017.

[11] Ibid.; Nodirbek Soliev, “Tracing the Fate of Central Asian Fighters in Syria: Remainers, Repatriates, Returnees, and Relocators,” Perspectives on Terrorism 15:4 (2021): p. 126; Kathleen Collins, Politicizing Islam in Central Asia: From the Russian Revolution to the Afghan and Syrian Jihads (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023), p. 447.

[12] Author interviews, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Kazakh embassy officials, Washington D.C., 2018, 2019, 2024.

[13] Noah Tucker, “Islamic State Messaging to Central Asians Migrant Workers in Russia,” Central Asia Program, GWU, CERIA Brief No. 6, March 2015; Thomas F. Lynch III, Michael Bouffard, Kelsey King, and Graham Vickowski, “The Return of Foreign Fighters to Central Asia: Implications for U.S. Counterterrorism Policy,” Strategic Perspectives 21 (2016).

[14] Collins, Politicizing Islam in Central Asia, p. 447.

[15] “Officer: Uzbeks, Uighurs among remaining foreign militants in Mosul’s Old City,” Iraqi News, April 24, 2017.

[16] Edward Lemon and Noah Tucker, “A ‘Hotbed’ or a Slow, Painful Burn? Explaining Central Asia’s Role in Global Terrorism,” CTC Sentinel 17:7 (2024); author interview, Damon Mehl, August 2018.

[17] Fishman, The Master Plan; Mironova; Maria Galperin Donnelly, Thomas M. Sanderson, Olga Oliker, Maxwell B. Markusen, and Denis Sokolov, “Russian-Speaking Foreign Fighters in Iraq and Syria,” CSIS Report, December 29, 2017.

[18] Schmid, p. 3.

[19] The Soufan Center data is published in Niall McCarthy, “Scores Of ISIS Foreign Fighters Have Returned Home,” Forbes, October 25, 2017.

[20] Author interviews, U.S. embassy officials, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, June 2019.

[21] Soliev, pp. 129-130.

[22] Noah Tucker, “Foreign Fighters, Returnees and a Resurgent Taliban: Lessons for Central Asia from the Syrian Conflict,” Security and Human Rights, February 2022; author interview, Uzbek embassy official, Washington D.C., August 2019.

[23] Soliev, p. 126.

[24] Collins, Politicizing Islam in Central Asia, pp. 381-409; Bruce Pannier, “Countering a `Great Jihad’ in Central Asia,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, November 19, 2024.

[25] Joanna Paraszczuk, “Main Uzbek Militant Faction in Syria Swears Loyalty to Taliban,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, November 12, 2014.

[26] Author interviews, journalist and GKNB official, Kyrgyzstan, November 2018 and June 2019. See also “‘We Live in Constant Fear:’ Possession of Extremist Material in Kyrgyzstan,” Human Rights Watch, September 2018, p. 16.

[27] Mariya Omelicheva, “Ethnic Dimension of Religions Extremism and Terrorism in Central Asia,” International Political Science Review 31:2 (2010): pp. 167-186; Collins, Politicizing Islam in Central Asia, pp. 246-249.

[28] “Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) letter detailing the establishment of the IMU’s Bukhari Camp,” Harmony document AFGP-2002-000489, Combating Terrorism Center, West Point; Damon Mehl, “The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan Opens a Door to the Islamic State,” CTC Sentinel 8:6 (2015).

[29] Mehl.

[30] Toby Harnden, First Casualty: The Untold Story of the CIA Mission to Avenge 9/11 (New York: Little Brown and Co, 2021), pp.181-185.

[31] Jeremy Binne and Joanna Wright, “Uzbek-led Fighters in Afghanistan and Pakistan,” CTC Sentinel 2:8 (2009).

[32] Don Rassler, Fountainhead of Jihad: The Haqqani Nexus, 1973-2012 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). See also DIA FOIA Electronic Reading Room, document 161542, October 2004.

[33] Reza Khan, “The Death Knell for Foreign Fighters in Pakistan?” CTC Sentinel 7:8 (2014).

[34] Anne Stenersen, “Uzbekistan’s Role in Attacks in Pakistan,” CTC Sentinel 7:7 (2014); Collins.

[35] Guido Steinberg, “A Turkish Al-Qaeda: the Islamic Jihad Union and the Internationalization of Uzbek Jihadism,” Strategic Insights, July 2008.

[36] Binne and Wright; Guido Steinberg, German Jihad: On the Internationalization of Islamist Terrorism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), p. 12.

[37] Caleb Weiss, “State Adds Uzbek Jihadist Group to Terror List,” FDD’s Long War Journal, March 22, 2018; Paraszczuk.

[38] Rassler.

[39] Caleb Weiss, “Uzbek jihadist group claims ambush in northern Afghanistan,” Threat Matrix, FDD’s Long War Journal, February 9, 2017; Paraszczuk; author interviews, Damon Mehl, August and November 2018.

[40] Weiss, “State adds Uzbek jihadist group to terror list;” author interviews, Damon Mehl, 2018; author interview, U.S. government official, 2018.

[41] Estimates vary by year and source. See “State Department Terrorist Designation of Katibat al-Imam al-Bukhari,” U.S. Department of State, March 22, 2018, and “Katibat Imam al-Buhkari (KIB),” United Nations Security Council, n.d.

[42] “State Department Terrorist Designation of Katibat al-Imam al-Bukhari.”

[43] “Katibat Imam al-Buhkari (KIB);” video on jihadology.net.

[44] Bill Roggio, “Uzbek commands group within the Al Nusrah Front,” FDD’s Long War Journal, April 25, 2014.

[45] Bill Roggio and Caleb Weiss, “Jihadists continue to advertise training camps in Iraq and Syria,” FDD’s Long War Journal, December 28, 2014.

[46] Caleb Weiss, “Uzbek group showcases fighting Kurds in Aleppo,” FDD’s Long War Journal, April 13, 2016.

[47] “Katibat Imam al-Buhkari (KIB).”

[48] Weiss, “Uzbek group showcases fighting Kurds in Aleppo.”

[49] “Katibat Imam al-Buhkari (KIB).”

[50] Weiss, “Uzbek group showcases fighting Kurds in Aleppo.”

[51] Caleb Weiss and Joe Truzman, “‘Incite the Believers’ continues to fight Assad regime in southern Idlib,” FDD’s Long War Journal, January 27, 2020.

[52] Weiss, “Uzbek Jihadist Group Claims Ambush in Northern Afghanistan.”

[53] Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, “Hurras al-Din: The Rise, Fall, and Dissolution of al-Qa`ida’s Loyalist Group in Syria,” CTC Sentinel 18:5 (2025).

[54] The document and its translation can be found at “The Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham-al-Qaeda Dispute: Primary Texts (X),” Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, February 6, 2019.

[55] “Statement Regarding Classifying al-Bukhari Brigade,” Imam Bukhari Battalion, March 25, 2018, translation posted at https://www.longwarjournal.org/wp- content/uploads/2018/03/DZKizoOWsAAtKe3.jpg

[56] Uran Botobekov, “Central Asian Terrorist Groups Join Jihad Against U.S. After Declaration of Jerusalem as Israel’s Capital,” CACI Analyst, February 16, 2018.

[57] Abubakar Siddique, “Taliban Leader’s Dominance Results In Increased Oppression, Isolation,” Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, January 22, 2023.

[58] Akmal Dawi, “Unseen Taliban Leader Wields Godlike Powers in Afghanistan,” Voice of America, March 28, 2023; Weiss, “State adds Uzbek jihadist group to terror list.”

[59] “Katibat Imam al-Buhkari (KIB);” “Letter dated 23 May 2023 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, June 1, 2023, p. 18.

[60] See Muhojir’s letter, “The Good News of Victory,” to the Taliban, February 29, 2020.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Léa Polverini and Robin Tutenges, “The Kyrgyz Trap,” Pulitzer Center, May 2025.

[63] Collins, Politicizing Islam in Central Asia, pp. 391-393, 453.

[64] Ibid., p. 453; Uran Botobekov, “Katibat al Tawhid wal Jihad: A faithful follower of al-Qaeda from Central Asia,” Modern Diplomacy, April 27, 2018.

[65] Author interviews, human rights activists, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, June 2019; Kathleen Collins, “Kyrgyzstan’s Latest Revolution,” Journal of Democracy 22:3 (2011).

[66] “The Prosecutor General of Osh City vs Rashod Kamalov,” Global Freedom of Expression, October 7, 2015; Collins, Politicizing Islam in Central Asia, pp. 394-395.

[67] Botobekov, “Katibat al Tawhid wal Jihad.”

[68] Ibid; Collins, Politicizing Islam in Central Asia, pp. 453-454.

[69] Ibid.

[70] “Katibat al Tawhid wal Jihad (KTJ),” Counterextremism Project, n.d.

[71] Author interview, Muhammad Tahir, journalist and director, Radio Free Europe, November 2018; Noah Tucker, “Not in Our Name,” Radio Free Europe, December 4, 2018.

[72] Author interviews, Damon Mehl, August and November 2018.

[73] Author’s database of Abu Saloh videos. For similar observations of videos, see Noah Tucker, “Research Note: Uzbek Online Recruiting to the Syrian Conflict,” CERIA, CAP, GWU, No. 3, November 2014.

[74] “[Uzbek Militants Join Al-Qaeda in Fight Against Russia],” Radio Liberty, November 3, 2015. The video link on YouTube is now defunct.

[75] Caleb Weiss, “Foreign jihadists advertise role in Latakia fighting,” Threat Matrix, FDD’s Long War Journal, July 11, 2016; Caleb Weiss, “Uzbek group pledges allegiance to Al Nusrah Front,” FDD’s Long War Journal, September 30, 2015.

[76] Weiss, “Foreign jihadists advertise role in Latakia fighting.”

[77] Caleb Weiss, “Foreign jihadists involved in Hama fighting,” FDD’s Long War Journal, June 12, 2019.

[78] “Who is Katibat al-Tawhid wa-l-Jihad?” Syrians for Truth and Justice, April 20, 2022.

[79] Ibid.; Cameron Colquhoun, “Inghimasi – The Secret ISIS Tactic Designed for the Digital Age,” Bellingcat, December 1, 2016.

[80] “Terrorist Designation of Katibat al Tawhid wal Jihad,” U.S. Department of State, March 7, 2022; “Alleged sponsor of St. Petersburg terror act named,” Ferghana Information Agency – Moscow, September 1, 2018.

[81] “Terrorist group’s leader, native of Kyrgyzstan, killed by Russian forces in Syria,” AkiPress.com, Kyrgyzstan, September 11, 2022.

[82] Ibid.

[83] “Who is Katibat al-Tawhid wa-l-Jihad?”

[84] “Militant Enterprises: The Jihadist Private Military Companies of Northwest Syria,” Syria Justice and Accountability Centre, May 9, 2024.

[85] Daniel Garofalo, “Interview with the Founder of Syria-Based Muhojir Tactical,” Daniele Garofalo Monitoring, May 12, 2023.

[86] “[Uzbek Militants Join Al-Qaeda in Fight Against Russia].”

[87] For example, “Abu Saloh, ‘jihod haqida’” [Abu Saloh “About Jihad”], YouTube, April 5, 2018; “[Are you scared to go to Jihad? We are as brave as the companions], YouTube, May 22, 2017; Saloh Mujohid Haqida, “[Abu Saloh Mujohid],” YouTube, May 23, 2019. The latter had over 99,000 views. Sheikh Navqoti’s more recent posts on various YouTube and Telegram channels have had tens of thousands of views.

[88] Botobekov, “Central Asian Terrorist Groups Join Jihad.”

[89] Uran Botobekov, “The Evolution of an al-Qaeda Affiliate: Unmasking Notorious Uzbek Leader Abdul Aziz Domla of Katibat al-Tawhid wal Jihad,” Homeland Security Today, September 10, 2023.

[90] Author database of Abu Saloh online videos and audio recordings.

[91] Uran Botobekov, “How Taliban Victory Inspired Central Asian Jihadists,” Modern Diplomacy, September 17, 2021.

[92] “Letter dated 23 May 2023 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee.”

[93] Ibid.

[94] “Falastinga qanday yordam bera olamiz?” Ustoz Abdulaziz, YouTube, October 20, 2023.

[95] The YouTube video link is now defunct. See Uran Botobekov, “How Are Central Asian Jihadi Groups Exploiting the Israel-Hamas War?” Diplomat, December 1, 2023.

[96] Aaron Zelin, “New Video Message from Hayat Tahir al-Sham’s Dr. Mazhar al-Ways, ‘Support for Our People in Gaza,’” jihadology.net, October 15, 2023.

[97] The YouTube video link is now defunct. See Botobekov, “How Are Central Asian Jihadi Groups Exploiting the Israel-Hamas War?”

[98] “Letter dated 20 January 2020 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations, January 20, 2020.

[99] Mehmet Emin Cengiz, “The Aleppo Offensive: The Shattering of the Status Quo in Syria,” Al Sharq Strategic Research, December 2, 2024; “Al-Fath Al-Mubin Operations Room [FMOR],” Global Security, November 27, 2024.

[100] Uran Botobekov, “Central Asian Militants in Post-Assad Syria: Evolving Roles and Challenges,” Homeland Security Today, January 7, 2025.

[101] “Hama Shahriga Kirish 06.12.2024 | Abu Yusuf Muhojir,” YouTube, December 6, 2024.

[102] Poistine, “New Syria and Israel Aggression, Ajiob, Ajsin, Really,” YouTube, December 10, 2024.

[103] Rany Ballout, “What Will Syria Do with Its Foreign Militants?” National Interest, July 31, 2025.

[104] Daniel Garofalo, “Propaganda of the Jihadist Tactical Groups, May & June 2025,” Daniel Garofalo Monitoring, July 25, 2025.

[105] Ahmad Sharawi, “Trump presses Sharaa on foreign fighters as jihadists rise in Syria’s new army,” FDD’s Long War Journal, May 16, 2025.

[106] “803 Individuals Extrajudicially Killed Between March 6-10, 2025,” Syrian Human Rights Network, March 11, 2025.

[107] Farangis Najibullah, “Foreign Fighters Promoted In Syria’s New Army Have Their Governments Concerned,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, January 8, 2025; Ahmad Sharawi, “Profiles of commanders in the new Syrian army’s regional divisions,” FDD’s Long War Journal, March 20, 2025.

[108] “Syria: Briefing and Consultations,” Security Council Report, May 20, 2025.

Skip to content

Skip to content