Abstract: With wars raging in Ukraine and Gaza, and geopolitical tensions running high globally, the Paris Olympic Games face a concerning and complex threat picture. By far the biggest threat is jihadi terrorism, and specifically the Islamic State Khorasan group, which launched the deadliest Islamic State terrorist attack in Europe in Moscow in March and has already sought, through its signature cyber-coach approach to terrorism, to get individuals in France to carry out attacks targeting the Games. Far-right and far-left violent extremist groups also pose concern, as does the potential for protests on, for example, the war in Gaza to turn violent. The French are on high alert for malevolent activity from Russia amidst mounting examples of its links to violent far-right actors in Europe. It appears unlikely the Iran threat network will directly target the Games because Iran is participating in them and because Iran does not want a breakdown in its relations with Europe. But if the conflict between Israel and Hezbollah escalates significantly before and during the Games, an attack by the Lebanese terrorist group on Israeli interests cannot be ruled out given it has in the past targeted Israelis in Europe.

On March 25, 2024, French President Emmanuel Macron announced France was elevating its terror alert level to the highest level after Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) carried out an attack on a concert hall at the Crocus shopping center in Krasnogorsk outside Moscow on March 22 that left 144 dead and 285 wounded.a Macron stated that ISK had “carried out several attempts on our soil in recent months.”1 French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal revealed that a thwarted plot in Strasbourg in 2022 had been connected to the group.2

The Crocus concert hall attack was the deadliest Islamic State attack in Europe ever, with more fatalities than the November 13, 2015, attacks in Paris that killed 131 and injured more than 400. It was not a surprise that Moscow was targeted. Russia has been an enemy of global jihadis since the days of the mujahideen’s 1980s jihad in Afghanistan. The Islamic State and Russia have clashed in Syria, Libya, Mozambique, and the Sahel region of Africa. In October 2015, the Islamic State’s Sinai branch downed a Russian plane over the peninsula, killing all 224 passengers.3

Islamic State-associated terrorism remains a potent threat to Western European countries and is the main security risk to the Paris Olympics. While there was a significant decrease in Islamic State-related attack plotting across Western Europe following the territorial defeat of the caliphate in 2019, plotting and attacks never ceased, and ticked up in 2023-2024.4

Ever since the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, geopolitics and great power competition have taken center stage in Europe; terrorism has gone from being a top priority for governments to one of many threats. With security agencies stretched thin, there has been a more permissive environment for terrorists and extremists—both non-state and state-supported—to mobilize and plot attacks without being detected.

With athletes and representatives of all nations (apart from Russia and Belarus) gathering from July 26 to August 11 in Paris for the Olympics, to include a large team from the United States, there is significant concern that terrorist actors could launch attacks while the world’s media spotlight is on France in order to gather global attention for their causes. It is hardly uncommon for terrorists to target sports venues.5 Terrorist attacks against major sports events have included Black September’s 1972 Munich hostage attack and the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing by al-Qa`ida supporters. The November 2015 Islamic State attack on the Bataclan and other targets in Paris also included attempted suicide bombings at the Stade de France stadium as 80,000 spectators watched an international soccer match between France and Germany. Furthermore, the European Islamic State crew that eventually struck the airport and other targets in Brussels in March 2016 originally plotted to attack the 2016 UEFA European Football Championship being hosted that year in France. They decided to change their plans out of fear of being caught after Salah Abdeslam, the sole surviving perpetrator of the 2015 Paris attacks, was arrested in Brussels.6

Europe is on high alert during this summer of sport. In early June, a week before the start of the Euro 2024 soccer tournament in Germany, police at Cologne airport arrested an alleged ISK supporter of shared German-Moroccan-Polish nationality who the previous September had allegedly transferred almost $1,700 via a cryptocurrency exchange to ISK. He had applied for a job as a steward and security guard for side events outside the soccer stadiums during the Euros.7 On June 18, German authorities publicly warned that Germany could see a large-scale ISK attack. “A possible scenario is a large-scale, co-ordinated attack of the kind we recently saw in Moscow,” said Thomas Haldenwang, head of Germany’s domestic intelligence agency (BfV), adding that ISK was “certainly the most dangerous group.” He added ISK had succeeded in “sending its supporters to western Europe, under cover of the refugee exodus from Ukraine.”8 According to a French security source, while Ukraine was indeed used as a refuge for a few fleeing Islamic State operatives, it has not become a staging ground for terror attacks nor a destination-of-choice for such jihadis.9

Attacking high-profile events is not easy for terrorist groups to pull off given their limited resources and stepped-up security efforts, target hardening, and the efforts by governments to intercept potential attack cells early ahead of such events. For example, Sweden, already on edge due to extremist threats and terrorist plots in the wake of Qur’an burnings, intensified security in the run-up to the May 2024 Eurovision contest. Despite forceful pro-Palestinian protests, and some minor violent incidents and threats, the event in Malmö saw no extremist or terrorism-related violence.10 However, security agencies’ ability to predict when and where terrorism might occur is limited at best. Terrorists tend to strike when and where they can, and typically where they are least expected to.

Furthermore, former head of Counter Terrorism Command at the London Metropolitan Police Richard Walton has noted that “the vulnerable underbelly” of big sporting events such as the Olympics is “outside of the host cities in venues and stadiums, transport hubs, and other crowded places where police are not familiar with high levels of security.”11 During France’s hosting of the 2016 Euro tournament, an Islamic State-inspired terrorist murdered a police officer in Magnanville northwest of Paris.12

The upcoming Olympics in Paris face risks linked to multiple different threat actors amidst a challenging security environment for France and its European partners. The Islamic State and likeminded extremists are the main threat to the Games, but increased polarization in the Western world over issues ranging from immigration, the economy, the environment, and international armed conflicts has produced a complex threat matrix. This article addresses the threat posed by jihadism, violent manifestations of Gaza protests, Iran-supported hybrid terrorism, and Russian influence and destabilization operations that could intensify such threats. The authors examine both right-wing and left-wing terror threats, but do not consider the threat posed by separatism. Separatist groups remain active in several parts of Europe, including the United Kingdom (Northern Ireland) and France (Corsica),13 but they operate locally against local authorities and pose less of a threat to international events such as the Olympics.

The Jihadi Threat to the Paris Olympics

Jihadi terrorism represents, by a significant margin, the biggest threat to the Paris Olympics and remains the biggest threat in Europe writ large.14 Although the central leaderships of al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State have not, as of the time of publication, issued direct threats to the Paris Olympics, jihadism remains the core terror threat to France. There is high attack activity by Islamic State-associated terrorists in France and, as will be outlined, French authorities have already foiled several terror plots targeting the Olympics. Islamic State supporters have shared propaganda and manuals on social media encouraging lone wolf attacks during the Olympics, including the use of weaponized small commercial drones.15

Jihadis view France as an archenemy, citing its colonial history (Algeria, Sahel), its military campaigns against jihadis (Africa, Syria, Iraq), and ‘injustices’ against Muslims (France’s ban on the niqab veil, the cartoons published in its media of the Prophet Mohammad). The threat from jihadis has ebbed and flowed in France since the 1990s, and the country has experienced waves of attacks linked to al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State, several of them mass casualty attacks, including the Charlie Hebdo and November 13 attacks in 2015 and the 2016 Nice attack.

France is home to longstanding jihadi networks and entrepreneurs,16 many returned foreign fighters, and numerous jihadis in and out of jail. This causes major concerns about recidivism in which freed terrorists rejoin terror networks and launch new attacks. France has seen examples of this dynamic with al-Qa`ida terrorists in the past, including the terror entrepreneur behind the January 2015 attack on Charlie Hebdo,17 but so far, the country has witnessed few recidivist attacks involving released Islamic State-linked terrorists, the knife attack in the vicinity of the Eiffel Tower in December 2023 being one notable exception (addressed below).18

Like other Western countries, France has experienced polarization and tensions over Islam and immigration, contributing to the problem set of terrorism, anti-Islam mobilization, segregation, and radicalization.19 The jihadi terror threat to France is linked to transnational jihadi terror networks within Europe and outside its borders including the Islamic State presence in conflict zones in Syria and Iraq in the mid-2010s and in Afghanistan today.

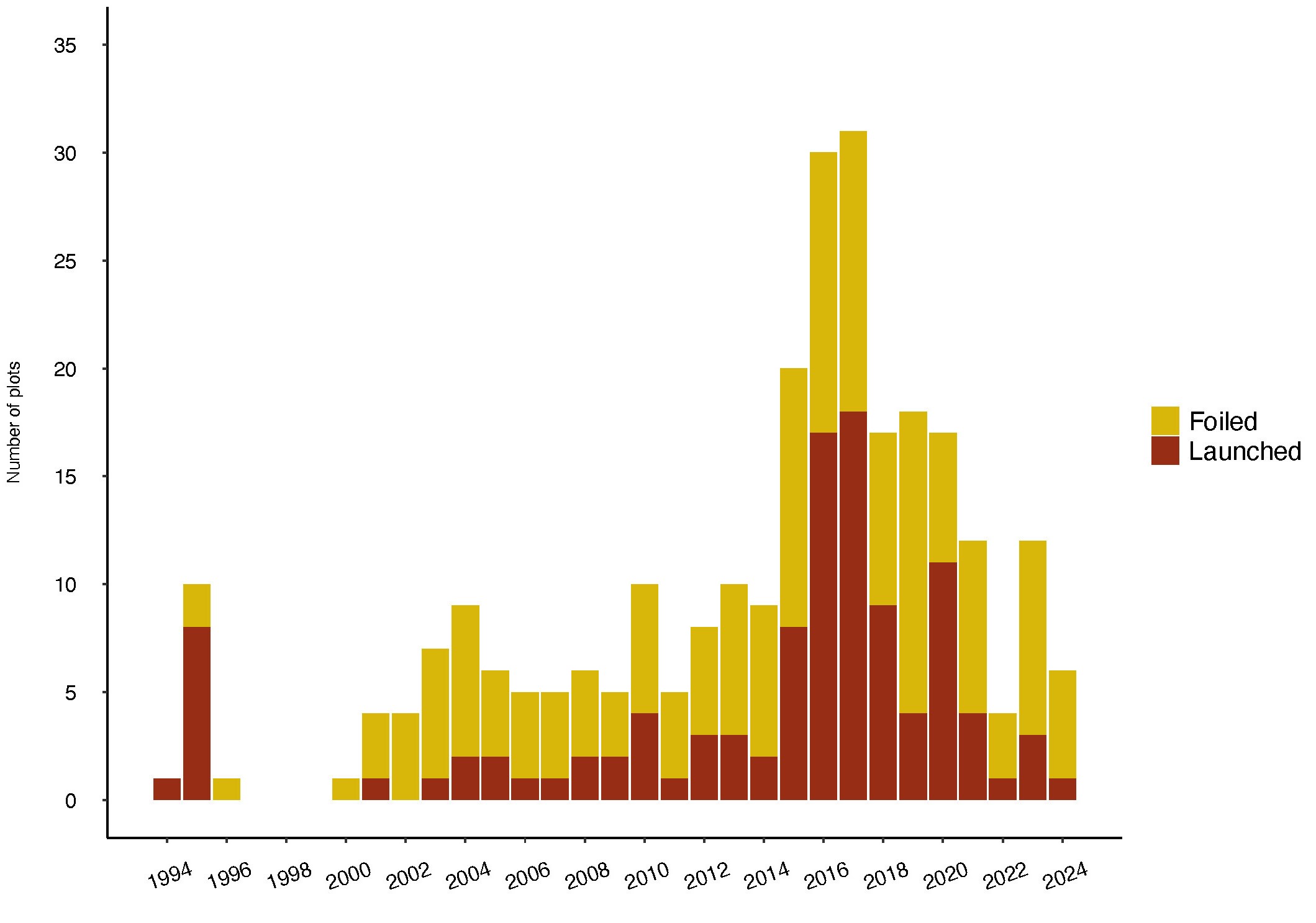

According to FFI’s Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED),20 b around a quarter of all attack activity (foiled plots and launched attacks) by terrorists linked to or inspired by the Islamic State in Western Europe in recent decades happened after the collapse of the Islamic State’s ‘caliphate.’ The dataset includes 273 well-documented jihadi terror plots from 1994 until 2024, 69 of them occurring between January 1, 2019, and June 1, 2024. For the period 1994-2018, 58 percent (118 of 204 cases) are foiled plots. For the period January 1, 2019, until June 1, 2024, 65 percent (45 of 69 cases) are foiled plots. While jihadi attack activity has decreased in the region since the high tide of 2014-2017, when the Islamic State was at its strongest and prioritized international terrorism, today’s threat is higher than most assume.21 The number of plots and attacks has fluctuated between 19 and four in the period 2019 to the present day with the lowest numbers (four cases) recorded in 2022 followed by increase in 2023 and worrisome numbers so far in 2024 (six to eight cases).22 The threat involves a variety of perpetrators and attack modes, ranging from amateurish teenage Islamic State fans who plot simple attacks alone to cells composed of seasoned jihadis with ties to Islamic State networks in Europe and groups abroad (such as ISK) plotting complex potentially mass-casualty attacks. As will be outlined later in the article, a significant number of plots have seen ISK operatives guide plotters from overseas. Analysts have referred to such figures as terrorist “cyber coaches”23 or “virtual entrepreneurs.”24

Several attacks and plots targeted French teachers accused of insulting the Prophet Mohammad, such as the 2020 killing of Samuel Paty by an 18-year-old of Chechen origin and the 2023 killing of a teacher in Arras by a 20-year-old of Chechen origin. The Arras case was motivated by hatred toward France and injustices against Muslims in Iraq, Asia, and Palestine.25 Both attackers hailed from religious families and were influenced by known extremists. The killer of Samuel Paty was in contact with a Tajik HTS member in Syria, though he never expressed any political motive for his crime and did not link it to any terrorist organization while he had the opportunity to do so. An HTS spokesperson at the time denied any involvement of the group in the issue.26 The Arras killer, on the other hand, vowed allegiance to the Islamic State’s caliph, as was proven by investigators’ exploitation of his electronic devices, even though the Islamic State never claimed responsibility.27 Fast forward to June 2024 and the loosening of HTS’ grip on northwestern Syria has become a source of concern for French security agencies because some French-speaking jihadis still at large in the Idlib area have made aggressive comments online in relation to the Paris Olympics.28

Several recent attacks in Europe have targeted LBGTQ+ individuals, such as the October 2020 stabbing of gay men by a 20-year-old Syrian in Dresden (killing one of them);29 the stabbing of gay men in a park in Reading, United Kingdom, by a 25-year-old Libyan Islamic State supporter in July the same year,30 killing three and injuring two; and the June 2022 shooting attack on Pride-revelers outside a gay bar in Oslo, Norway, killing two and injuring 21. The Oslo attacker was of Iranian-Kurdish origin. He interacted with known Norwegian Islamic State supporters both inside and outside Norway, physically and/or digitally, including allegedly a female Norwegian foreign fighter in a Syria detention camp. The Oslo perpetrator shot at crowds using a pistol and a machine gun, which fortunately jammed before he was overpowered by victims and bystanders and arrested by police.31

In the years since the collapse of the Islamic State’s caliphate, multiple attacks and plots have targeted members of the security apparatus, mainly police officers in the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, and Germany. A radicalized IT-worker for French police killed colleagues at a Paris police station in October 2019.32 There were at least two knife attacks targeting policewomen, in Rambouillet33 (April 2021) and Chapelle-sur-Erdre34 in May of the same year. In April 2020, an Islamic State-inspired extremist rammed his car into motorbike police in Paris, gravely injuring one of them.35 He had sworn allegiance to the Islamic State’s caliph and said he did it for the group and Palestine. In October 2020, a group of teenagers in Belgium planned to stab police officers but were intercepted.36 In May 2022, a U.K. teenager made preparations to kill police and soldiers using a hunting knife.37 More recently, in March 2024 two Afghans linked to ISK were arrested in Germany for plotting to attack police and crowds outside the Swedish parliament to avenge Qur’an burnings by anti-Islam activists in Sweden.38 The plot was reportedly an example of ISK employing a cyber-coach approach to enabling terrorism, which has become the group’s signature. According to German prosecutors, after having been tasked by ISK to carry out an attack, “the two made concrete preparations in close consultation with ISK operatives.”39 According to a French security source, cyber-coaching is the right term to describe the ISK modus operandi. The source says the group’s cyber-coaches act as a human resources hub that can connect different elements to conduct an attack. At the same time, according to the source, this can make it easier to foil plots since each hub tends to engage with many individuals and more than one plot.40

According to the JPED (with preliminary numbers for the period 2022-2024), one pattern is that while armed assaults with knives or gunsc dominate the jihadi threat in Europe between January 1, 2019, and June 1, 2024, (37 incidents, 54 percent of 69 cases), the terrorists keep on plotting bomb attacks (19 incidents, 28 percent of cases). During the same period, some 43 percent of armed assaults were foiled (16 out of 37 incidents), whereas 89 percent of bombing plots were foiled (17 out of 19 incidents). The high foiling rate for bomb plots likely reflects the fact that European security services have in recent years closely monitored jihadi attempts to obtain explosives. The recent high rate of thwarting bomb attacks in part explains why only five percent of deaths (33 of 660 killed in the whole dataset) occurred after 2018. The 2000s and 2010s saw multiple mass-casualty bombings, such as the train attacks in Madrid and London by al-Qa`ida-associated cells in 2004-2005 and the bombings in Manchester and Brussels by Islamic State-linked terrorists in 2016-2017.

The fact that jihadi terrorists go on attempting bomb attacks despite the high rate of these plots being detected and thwarted implies that death rates could rise again if European security services decide to decrease counterterrorism efforts to prioritize other risks. It is worth outlining some of these jihadi bomb plots for context. In 2019, German police thwarted a plot by several Iraqi Islamic State supporters directed by an Iranian Islamic State operative in the United Kingdom to inflict mass killings with explosives.41 The same year, a U.K.-based woman receiving instructions from a 25-year-old Norwegian-Somali jihadi in Norway plotted a suicide-attack on Saint Paul’s cathedral.42 In late 2019, Dutch security services intercepted an alleged plot to launch Mumbai-style terror attacks in the Netherlands with suicide vests and car bombs.43 That same year (2019) also saw jihadi bomb plots in Offenbach (March)44 and Berlin45 (November), Germany, and reportedly against a Christmas market in Austria (December).46 From 2020 onward, there were three foiled bomb plots in Germany: one by Tajiks allegedly linked to ISK against U.S. military bases and an Islam critic,47 one against a synagogue in the city of Hagen48 in 2021, and one against the Cologne cathedral on New Year’s Eve 2023 by Tajiks and Uzbeks linked to ISK.49 The 2020 plot by the Tajik Islamic State supporters to target U.S. bases in Germany was another example of the ISK using a cyber-coach approach to enabling terrorism in the West. As outlined by Nodirbek Soliev in this publication, “German prosecutors have described the cell’s contact in Afghanistan as a high-ranking Islamic State member and ‘religious preacher,’ who gave a series of radical lectures to the Tajik cell via the encrypted communication platform Zello. According to court documents, this militant issued ‘specific guidelines’ for ‘the attack’ planned by the cell in Germany.”50

The United Kingdom has seen at least two thwarted bombing plots since 2019, in Redhill51 and Leeds.52 Sweden and Denmark, which have been experiencing heightened threat levels linked to Qur’an burnings and the publication of cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad, have also foiled alleged bomb plots by Islamic State followers.53

The stereotype of the post-caliphate Islamic State plotter in Europe is a young individual who self-radicalizes via social media. While there are a few examples of self-radicalized plotters without ties to organized networks, investigations more commonly uncover interactions with Islamic State networks in Europe and internationally. Plotters interact with such networks physically and/or via social media communication apps, such as Telegram, WhatsApp, or, as noted above, Zello. Oftentimes, they receive guidance regarding tactics and targets. For the Islamic State and later ISK as already noted, such cyber-coaching has become a signature approach to enabling terrorism in the West. The former head of the Afghan intelligence agency NDS Ahmad Zia Saraj recently noted in this publication that:

using end-end-encryption, [ISK] can recruit, exchange information swiftly, plan, and execute attacks. It has meant that terror attacks have not needed the logistics of old. Now an [ISK] terrorist in Afghanistan can recruit a member who is living in, say, Sweden and fund him using cryptocurrency. Because he’s only busy with his phone and he’s only using those apps, it can be very hard for the security services to detect that individual because that person may seem like a quite normal person. He may not appear to have any suspicious activities and so on, unless he is tracked through his telephone and his telephone is taken. […]

Encrypted messaging apps have helped terrorists speed up operations, enhance operational security, save time, save travel costs, and to plan and execute and even monitor attacks in real time. The NDS noticed that a newly recruited fighter does not need to physically attend a training camp to learn how to construct a bomb or how to target the enemy. All this can be done via a smart phone with less risk of exposure. Advancing technology has made it possible for someone to be trained in terrorist tactics in any part of the world, regardless of borders or travel restrictions. A terrorist in Afghanistan or Iraq can easily train another one in any part of the world.54

A French security source points out an important caveat: Cyber-coaches can only do so much, and at a certain point, it is up to the plotter on the ground to prepare and carry out an attack. The source notes that as terror plots materialize, they face usual real-world logistical challenges such as how to conduct surveillance, how to obtain vehicles, and how to obtain fire-arms.55 It stands to reason that those who have not received in-person training—at a training camp or safe house, for example—tend to be less adept at carrying out these tasks and concealing them from authorities.

One example of network embeddedness is the deadly attack against a German-Filipino tourist near the Eiffel Tower on December 2, 2023, by a 26-year-old Islamic State-affiliated terrorist of Iranian-Kurdish origin. The assailant had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State’s caliph and had said he wanted to avenge the killing of innocent Muslims. The attack seemed to have been triggered by the war in Gaza as the attacker had shared multiple posts about the conflict on social media.56 At the same time, the Eiffel Tower attacker was apparently well-known to the French security services for being radicalized and mentally unstable and was on the so-called ‘S-list’ (‘Fiche-S’).57 This list of potentially violent extremists in France contained in 2018 some 30,000 persons, of whom more than half were considered radical Islamists.58 The assailant had spent several years in jail for plotting a similar attack back in 2015-2016 but was released in 2020.59 The previous plot in 2015-2016 was allegedly instigated and supported by a French Islamic State foreign fighter in Syria with whom the Eiffel Tower attacker communicated online.60 Investigations into the 2023 attack by the Eiffel Tower revealed that the terrorist killer had multiple contact points (primarily via social media) with known Islamic State-linked or -inspired French terrorists such as the killer of a married police couple in their home in Magnanville in 2016, and one of the killers of a Catholic priest in Normandy the same year.61 As already noted, the Eiffel Tower attack was one of the first ‘successfully’ launched attacks in France by a perpetrator previously convicted for Islamic State-related terror plotting.d Given the high number of terrorists who have been released from prison in France after serving their sentence, the fact that there have been very few attacks by them suggests there should be concern but not panic about the threat of terrorist recidivism.62

While the threat to Western Europe is transnational, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany have been the most targeted countries, with France topping the list both before and after the collapse of the Islamic State’s territorial caliphate. Although not all early intercepted terror plots become known to the public, the ones that are publicly known indicate that France has a significantly lower rate of thwarting jihadi terror plots compared to the United Kingdom and Germany in 2019-2024. During these years, according to FFI data, France has foiled only 29 percent of publicly known plots (five out of 17 cases) compared to a thwarting rate at 58 percent for the United Kingdom (seven out of 12 cases) and as high as 94 percent for Germany (15 out of 16 terror plots).63 The fact that in recent years a significantly higher percentage of plots have gotten through in France compared to the United Kingdom and Germany is a concerning metric as the country prepares to host the Olympics.

France has been the main European enemy for jihadis since the early 1990s, when it was first attacked by the Algerian GIA. It has been exposed to al-Qa`ida and Islamic State terror ever since. The United Kingdom and Germany came under attack in the 2000s primarily for supporting the Global War on Terror and have both been home to significant jihadi networks and entrepreneurs.

From the early 1990s through at least the 2010s, the United Kingdom was the main hub for jihadi propaganda and recruitment in Western Europe. Over time, al-Qa`ida and Islamic State supporters in the United Kingdom built and coordinated networks across Western Europe that took part in, directly or indirectly, attack activity both in the United Kingdom and other European countries, France included. Germany has also since the 1990s been the home base of substantial jihadi support networks, which increasingly transformed into attack cells from around the millennium onward, the most notorious being the Hamburg cell that played an important role in the 9/11 attacks.64 In the post-caliphate era, Germany has faced more jihadi attack plots than the United Kingdom, but historically the United Kingdom has been the second most targeted country in Europe after France. The main difference between France and the United Kingdom, apart from geography (island versus land borders, something that makes access to firearms considerably more difficult in the United Kingdome) is their approaches to prevention and counterterrorism. France has relied on the military more than the United Kingdom in the counterterrorism domain for securing strategic and sensitive areas, including the deployment of large numbers of soldiers on patrols inside France, whereas the United Kingdom has focused more on prevention than France. Germany reformed and strengthened its counterterrorism systems significantly after the 2016 attack on a Berlin Christmas market by a Tunisian Islamic State supporter.65 Countermeasures were toughened all over Western Europe following the wave of Islamic State attacks between 2014-2017.66

The post-caliphate phase of European jihadism has also seen certain new patterns in terms of who the terrorists are and what drives them. The authors have observed an increase in the number of plots and attacks by teenagers under 18. At least one teenager under 18 appears in nine of 69 cases between 2019 and the present day (13 percent) compared to 18 of 204 cases before 2019 (nine percent). Examples include, among others, the aforementioned plots by teenagers to attack police in Belgium and the United Kingdom and a 16-year-old producing poison for an attack in Norway.67 Two alleged plots to launch terror attacks during the Paris Games also involved teenagers. In April 2024, French counterterrorism officials arrested a 16-year-old boy of Chechen origin suspected of plotting a suicide bombing and shooting attack in the La Défense business district during the Paris Olympics.68 In late May 2024, French security foiled another alleged plot by an 18-year-old man, also of Chechen origin, to launch a suicide attack against spectators and police during one of the upcoming Olympic soccer matches at Geoffroy-Guichard stadium in Saint-Étienne.69 Le Parisien newspaper reported that he was in contact with ISK operatives and plotted the attack in liaison with them, with his conspiratorial communications taking place over Telegram.70 However, according to a French security source, investigations have revealed that the operatives communicating with the Saint-Étienne plotter were Chechen Islamic State jihadis in Syria rather than belonging to ISK. The source added that while the Chechen networks and the ISK networks are distinct they operate in the same language (Russian), both employ a cyber-coach approach to external plotting, both attempt to recruit from geographically proximate diaspora communities, and have collaborated before.71 The Saint-Étienne plot speaks to how Islamic State branches have embraced the cyber-coach model to terrorism. In the authors’ assessment, the cyber-coach hub that reached out to the Saint-Étienne plotter may have established contact with others to try to get them to launch attacks during the Olympic Games. It should be noted that Chechen fighters are still active in eastern Syria west of the Euphrates.

Another emerging trend is an increase in the involvement of women in terrorist plotting: six out of 67 cases (nine percent) during 2019-2024 compared to 14 out of 204 cases (seven percent) between 1994 and 2019. Despite the fact that active participation of women in terrorist plots is an unresolved dogmatic question for the Islamic State, they have appeared in plots or attacks in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, France, Belgium, and Germany after the Islamic State’s collapse. Examples include, among others, the aforementioned plot to bomb Saint Paul’s cathedral in London in 2019, a plot by a female terrorist cell to attack a religious site in France during Easter 2021, a 2023 plot by Chechens to launch terror attacks in Belgium,72 and a 2024 plot to attack Christian worshippers and police in Germany.73

There have been a large variety of national backgrounds involved in recent plots and attacks, as has been the case throughout the history of European jihadism. In the post-caliphate era, there seems to be a relative increase in plotters with Central Asian backgrounds, primarily Chechens, Uzbeks, and Tajiks. As already noted, there have also been attacks and plots involving people of Iranian- Kurdish backgrounds. In sum, European jihadism continues to be multinational to include ethnic European converts to Islam.

With regard to motivation, al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State continue to seek to attack the United States, Israel, and their European allies, and all European nations that have fought jihadism are considered legitimate targets. They are all seen by jihadis as complicit in a war against Islam and insults against the Prophet Mohammad. Some countries, such as France and the United Kingdom, are prioritized as targets, but other countries face elevated threats due to specific developments. For example, Denmark has been a main target among Nordic countries due to the 2005 publications of cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad by a Danish newspaper. Sweden has seen an intensified threat in connection with Qur’an burnings since 2023, as exemplified by the cell intercepted in Germany plotting to shoot police and crowds outside the Swedish parliament.

It is important to note that there are signs that some al-Qa`ida affiliates are less motivated to transfer the fight to Western countries than they were in the past. For example, al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its nodes seemingly no longer consider attacks on French soil as part of their fight but do not rule out attacking French interests outside France, even though their main priority for now is to combat local juntas and Russian mercenaries in the Sahel.74

Israel’s war in Gaza has created concern that jihadi terror groups will exploit anger among Muslim communities around the world to rebuild their capacity to launch attacks in the West.75 In April 2024, FBI Director Christopher Wray testified that “we’ve seen the threat from foreign terrorists rise to a whole ‘nother level after October 7.”76 The Israel/Palestine issue has always been part of the motivation mix for jihadi terrorists in Europe and amplified threat levels. When Dutch Moroccan jihadi Mohammed Bouyeri killed filmmaker Theo Van Gogh in 2004, he was propelled by his anger at a short film he deemed offensive to Islam but he was also partially motivated by Israeli actions in Gaza and was a staunch supporter of Hamas.77 A similar pattern was seen with Mohammed Merah’s attack on a Jewish children’s school in Toulouse in 2012. He was part of al-Qa`ida’s networks78 and motivated by global jihad but targeted the school to, in his view, avenge the killing of Palestinian children.79

There are many such examples in the history of European jihadism, and in the aftermath of Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, injustices against Palestinians have once again featured as a partial motive and trigger for jihadi plots in Western Europe. Amidst the high number of civilian casualties in the Israeli war against Hamas in Gaza, there have been several terror incidents that were partly triggered by the Gaza war. The shooting of Swedish soccer supporters in Brussels in October 2023 appears to have been primarily motivated by Qur’an burnings but also partly by Gaza.f The attack on the teacher in Arras, France, later the same monthg and the attack on the German tourist near the Eiffel Tower in December 2023 also seemed to be partially motivated by Gaza,h as was the case with possible plots in Belgium to launch a suicide attack80 and an alleged plot in October 2023 to carry out a car-ramming attack on a pro-Israeli rally in Düsseldorf, Germany, by an Islamic State supporter.81 The suspect reportedly communicated with a chat partner in Syria about the attack plans in another possible example of cyber-coaching.82 Israeli attacks on Gaza have pushed and will continue to push already radicalized people to commit violence; it will also likely help to radicalize others.

Another risk is that jihadis might groom young, radicalized activists who are frustrated and disillusioned with the effects of law-abiding Gaza protests, into committing violence. While the authors have not seen examples of this since the start of the Gaza war, there are historical examples of people who progressed from Islamist activism to jihadi violence (e.g., followers of the U.K.-based al-Muhajiroun or Sharia4Belgium).83

European Gaza protests have been relatively peaceful until now, but there have been some violent incidents, such as a Molotov cocktail attack against a U.S. consulate in Italy.84 If the situation gets more heated, for example if protests spiral out of control and government crackdowns become harsher, this could make frustrated activists recruitment targets for malign actors, such as jihadis or states aiming to sow discord among Europeans.

Violent Activism

A potential violent threat to the Paris 2024 Olympics is political activism getting out of hand causing violence or ultimately terrorist incidents. The risk is low compared to the jihadi terror threat but cannot be ruled out. Pro-Palestinian protests have been intensifying across Western Europe since Israel launched its war against Hamas in Gaza, killing a high number of civilians.85 The deaths of women and children and the humanitarian situation has mobilized protesters on European streets, in the vicinity of political and state institutions, Israeli representations, and synagogues and on university campuses. The pro-Palestinian protest movements seem to be organized bottom-up, transnational, and multi-national including diasporas, students, left-wing activists, or average citizens from different political stripes. Social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram appear to be key vehicles of mobilization.86

Student protests resembling those in the United States, such as the occupation of a building and encampments at Columbia University, have occurred in multiple European countries including the United Kingdom, Ireland, Switzerland, and France, where students occupied buildings at elite universities Sorbonne and Sciences Po. Some student protests in the United States turned violent (clashes with police or counterdemonstrators), whereas European protests have so far been much calmer.87

In a few countries, protests have involved violent clashes, and there are also examples of support for Hamas, manifestations of antisemitism, vandalism, threats, physical violence against police or Jews, bomb threats, firebombs thrown at Israeli diplomatic offices and synagogues and explosives placed in the vicinity of Israeli diplomatic offices.88 Some of the incidents are examples of activism getting out of hand, but according to the Israeli intelligence service Mossad, criminal networks operating on Iran’s behalf were behind the placing of explosives in the vicinity of Israeli targets (addressed later in this article).89

European governments differ in their approach to the protests, and some countries such as Germany and France have introduced zero-tolerance measures against protests considered antisemitic or supportive of Hamas.90 French police evacuated student protesters at Sorbonne91 and Sciences Po.92 Whether tough responses curb or fuel the intensity of the protests remains to be seen. Neither the protests nor the countermeasures are comparable to the massive anti-Vietnam mobilizations in 1960s and 1970s America,93 but the latter demonstrated how violent crackdowns may generate more protests and internationalize protests.

While most European protests have been non-violent, there have been, as noted, other worrying incidents that could signal a turn to the worse in some countries. In November 2023, activists vandalized a Jewish cemetery in Austria.94 The same month in the Swedish city of Malmø, protesters burned Israeli flags and expressed bombing threats against Israel outside a synagogue. In January 2024, protesters violently disrupted a jewelry fair in Vicenza, Italy, because of Israeli participation, throwing firebombs and flares, and clashing with police.95 In April 2024, protesters disrupted a conference on scientific cooperation in Turin, calling for a boycott of Israel. The protesters tried to enter the venue, resulting in several polices officers and protesters being injured in clashes.96

In October 2023, as many as 65 police officers were injured during a pro-Palestinian riot in the Berlin borough of Neukölln, where activists threw stones and burning liquids. Protesters reportedly advertised this riot on Telegram, urging men to turn “turn NeuKoelln into Gaza. Burn everything.”97 On October 18, assailants threw Molotov cocktails at a Berlin synagogue.98 On October 21, four Syrians (aged 17-21) were arrested in Cyprus suspected of setting off a small explosive near the Israeli embassy.99 On February 2, 2024, a 22-year-old Hamas supporter threw Molotov cocktails at the U.S. consulate in Florence. He reportedly issued a video threatening 50 attacks against ‘Zionist targets’ (half of the targets were not Israeli or American).100

As of late June, Israel continues to carry out offensive operations in Gaza. Pro-Palestinian protests should be expected in Paris during the Olympics, and one cannot rule out violent incidents, despite the massive security presence. The highly diverse nature of the pro-Palestinian protest movements that mostly include benign peaceful activists and smaller segments of potentially violent actors, poses a special challenge to security forces. In this instance, they face a less predictable threat than from known terrorist networks and one that requires flexible approaches, facilitating democratic rights while clamping down on violent transgressions. With Gaza tensions running high, violent manifestations of activism by new types of actors could slip through the net as French security has its hands full with more familiar threats such as jihadism. The self-immolation of a U.S. serviceman in February in front of Israel’s embassy in the United States101 was just one illustration of how the Gaza war is mobilizing strong sentiment in Western societies across a broad spectrum of the population.

Of the attending nations, Israel and the United States face the highest risks from any violent protests. While violent manifestations of pro-Palestinian activism are a threat in their own right, they could also overstretch a security apparatus mainly focused on the jihadi threat. And as noted, frustrated radicalized activists who want to harm Israel could be targeted for recruitment by militant Islamic State networks. Pro-Palestinian protests or violent incidents could also generate counterprotests or amplify threats from extreme far-right or extreme left-wing actors.

Extreme Right- and Left-Wing Threats

Neither right- nor left-wing extremists have a history of carrying out terror attacks against sports events in Western Europe. However, given the extreme left’s anti-Zionism and support for the Palestinian cause, and the extreme right’s antisemitism, one cannot rule out the possibility of political violence in France during the Paris Olympics from such actors in the Gaza war context.

The Extreme-Left

Although extremism and political violence by contemporary left-wing and anarchist actors in Europe are understudied,102 such actors have posed a relatively limited terrorist threat in Western Europe since the 1970s and 1980s when groups such as the Red Army Faction (RAF), the Italian Red Brigades, and anarchist Action Directe in France launched terrorist campaigns, involving large-scale lethal attacks as well as smaller targeted operations. While the RAF did not itself target sports events, it cooperated with Palestinian nationalist terrorists103 including Black September Organization (BSO) behind the attack on the Munich Olympics of 1972 (BSO demanded the release of RAF leaders from German jails during the hostage crisis).104

The European left-wing terrorists of the 1970s and 1980s received state support from communist countries and operated and cooperated across state boundaries. The German RAF, as noted, cooperated with Palestinian nationalist terror groups such as PFLP.105 The European left-wing terrorists targeted symbols of capitalism, businesses, political opponents (conservative/right-wing), and U.S./NATO for supposedly Americanizing Europe. This period was the high-tide of left-wing terrorism in Europe. Left-wing terror groups disintegrated after the fall of the Soviet Union, and Europe’s extreme left-wing and anarchist movements became fragmented.

Contemporary European left-wing and anarchist extremists are ideologically diverse, overlapping with different single-issue activisms, including environmentalism, animal rights, anti-vaccination, or incel culture.106 They are mostly associated with (sometimes) violent protests or clashes with extreme right-wing activists, vandalism, sabotage and threats against state institutions and representatives (including police and representatives of the judicial system), infrastructure, businesses, and occasionally plotting lethal terrorism.

Data from Europol and the Global Terrorism Database shows significant numbers of yearly left-wing anarchist attacks in Europe. According to Europol, in 2022 of the 16 attacks recorded in the European Union, “the majority were attributed to left-wing and anarchist terrorism (13), two to jihadist terrorism, and one to right-wing terrorism.”107 However, such left-wing attacks are seldom comparable to jihadi or right-wing mass-casualty terrorism. Referring to left-wing extremism and anarchism, Ilkka Salmi, the former EU Counter-Terrorism Coordinator, noted that “even if attacks linked to this part of the ideological spectrum are quite numerous, they are often far less lethal.”108

Most left-wing anarchist attacks involve IEDs against buildings and infrastructure, and rarely cause deaths. Several Western European countries have recently voiced concerns over increased violent actions from left-wing anarchist groups, and there have been foiled attack plots designed to kill. For example, in June 2022 an Italian anarchist group sent a postal package containing an IED to the CEO of a defense and security firm in Italy, which was detected and disarmed.109

In Germany, the 2023 trial of members of a violent left-wing group targeting real and purported right-wing extremists raised concerns about a left-wing terrorism resurgence.110 In May 2023, U.K. police arrested a self-proclaimed left-wing anarchist for plotting terrorist attacks on government buildings and houses of politicians. He wrote a terrorist manual, gathered chemicals for bomb-making, and had downloaded computer files needed to make a 3D-printed assault rifle. Convicted of terror offenses in February 2024, this U.K. admirer of the American terrorist Ted Kaczynski wanted to assist others committing terror acts and had expressed intent to kill “at least 50 people.”111 In 2023, a trial started in France for what French authorities refer to as an ‘ultra-leftist’ group that allegedly plotted terror attacks on police or military officers. The anarchist leader of this alleged terror cell had spent time as a foreign fighter in Syria with Kurds fighting the Islamic State.112

While left-wing terrorists could see opportunities at the Paris Olympics to target symbols of capitalism, Americanism, environmental degradation, or Israeli actions in Gaza, there is no shortage of such symbols at any given time, and violent left-wing actors do not currently display the intent or capacity for spectacular attacks.

The Extreme-Right

Whereas left-wing terrorism could be re-emerging in Western Europe, right-wing violence and terrorism saw some resurgence in the 2010s. According to the RTV dataset hosted by the Center for Research on Extremism (C-REX) at Oslo University, the region experienced relatively high levels of fatal political violence in the 1990s followed by lower attack activity in the 2000s113 before an uptick following the 2015 migrant crisis.114

The 2011 attacks by Norwegian right-wing terrorist Anders Breivik against the government quarters in Oslo and a political youth camp on Utoya island, killing 77 and injuring more than 300, underlined that anti-Islam sentiment was fueling right-wing extremism and demonstrated how right-wing terrorism could be as lethal and brutal as jihadism.

Western Europe has faced significant levels of right-wing political violence since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany.115 In the latter 2010s, security services in several European countries warned of a significant rise in right-wing terror plotting, with U.K. counterterrorism police referring to right-wing terrorism as “the fastest growing threat.”116 Yet, according to C-Rex data, this trend has not continued. Fatal attacks and terrorism by right-wing actors have decreased rather than increased in Western Europe after 2020.117

In terms of the geographical distribution of right-wing violence and terrorism in Western Europe, Germany has faced the highest levels in recent years, followed by the United Kingdom, Italy, Greece, and Spain.118 Among smaller countries, the Nordic countries of Sweden, Norway, and Finland have also seen significant levels.119 Most of this violence in Western Europe has targeted ethnic, religious minorities (and to a lesser extent sexual minorities), or political opponents (left-wing activists), or increasingly the state or state representatives.120 Most of the right-wing violence does not align with a narrow definition of terrorism, but represents political violence in a wider sense, including beating, kicking, and stabbing, but also arson, and the use of Molotov cocktails and IEDs. The perpetrators of this violence are typically gangs, or loose constellations of people who connect over neo-Nazi, fascist, racist, or anti-state (sovereign citizen) ideas and launch spontaneous hate-driven attacks. According to the C-Rex center, which tracks right-wing violence in Western Europe, when it comes to the overall trend, political violence by right-wing extremists has decreased in Western Europe from higher levels in the 1990s.121 One possible explanation is that right-wing populism has surged across Europe and entered the political mainstream, lowering incentives for political violence.122 A notable exception from the decline trend is France, which has experienced an upward trend in right-wing political violence of late.123

If one only considers terrorism, there were worrisome patterns of increased terrorist plotting (attacks and thwarted plans) from the latter 2010s and until 2023,124 most prevalent in Germany (e.g., an alleged bombing plot uncovered in September 2021),125 the United Kingdom (e.g., an alleged plot to attack police, LGBT+, and Muslims uncovered in October 2021)126 and France (e.g., a neo-Nazi plot to attack a Masonic lodge uncovered in May 2021),127 and to a lesser extent in Italy (e.g., an alleged plot to kill a left-wing activist uncovered in June 2021)128 and Sweden (e.g., the killing of a female psychiatrist in July 2022).129 But plots and attacks have occurred all over the region, including among other countries Norway (e.g., the failed attack on a mosque in Norway in August 2019),130 Finland (e.g., a plot by a Nazi cell to launch terror attacks with 3D-printed guns uncovered in November-December 2021),131 and Spain (e.g., a plot to kill the prime minister uncovered in September 2018).132

Such right-wing terrorist plots are rarely carried out by organizations staging terror campaigns in the manner of al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State, but by rather loose networks and individuals with extreme right-wing sympathies and eclectic ideologies fusing Nazism and fascist ideas with anti-Islam sentiment and increasingly revolutionary anti-state antagonisms fueled by conspiracy theories. Some of these terrorists have dabbled in right-wing populist politics, and most of them network in extreme right-wing social media, via Facebook, WhatsApp, Telegram, or other platforms and applications. Several plots have involved online links to the transnational Atomwaffen Division network emanating from the United States, such as the aforementioned 2021 bomb plot uncovered in Germany, which involved a former politician in the CDU who had become radicalized.133 The right-wing terrorist profiles vary and include teenagers as well as elderly people and both males and females. As with jihadism, most attacks by far-right terrorists in Western Europe involve single perpetrators, while several group-based plots have been intercepted. While tactics and weapons are generally simple (guns or simple IEDs), extreme right-wing plotters have shown a keener interest in utilizing 3D-printed weapons than jihadis, as will be documented below.

Multiple right-wing terrorist plots and attacks across Western Europe specifically targeted Muslims and some drew inspiration from the 2011 Norway attacks by Breivik and the 2019 attacks on mosques in New Zealand by Brenton Tarrant. In August 2019, a 22-year-old tried to carry out a mosque shooting in Norway but was overpowered and failed.134 In October 2019, an 84-year-old threw an incendiary device at a mosque in Bayonne, France, and shot at worshippers who confronted him, saying he wanted to avenge the fire at Notre Dame for which he blamed Muslims.135 In September 2020, a 55-year-old woman plotted to attack Muslims with explosives in Germany.136 In August 2021, a 15-year-old right-wing, anti-Islam, and anti-LGBT+ extremist inspired by Tarrant launched a knife attack at his school in Sweden in 2021, killing a teacher and threatening students. In September 2021, French police arrested a 19-year-old neo-Nazi and admirer of Hitler and the Norwegian terrorist Breivik, who allegedly plotted terrorist mass shootings at his school and a mosque.137 He had linked up with the online Atomwaffen network via social media and co-conspired with other teenagers, including a girl with jihadi sympathies. In February 2024, U.K. police intercepted a suspected three-man right-wing terror cell plotting attacks on an Islamic education center in Leeds using a 3D-printed semi-automatic weapon.138

Multiple extreme-right plots and attacks have in recent years targeted foreigners in general. In early 2019, a 50-year-old xenophobic man was arrested for ramming his car into crowds of foreigners in Germany.139 In February 2020, a mentally troubled 43-year-old right-wing extremist carried out a mass shooting at a shisha café, a bar, and another café in Hanau, killing nine people and injuring others before returning home where he killed his mother and committed suicide.140 In December 2023, a 69-year-old extreme right-wing French pensioner attacked a Kurdish cultural center, a Kurdish restaurant, and a Kurdish hairdressing salon in Paris with a Colt 45mm handgun, killing three and injuring three.141

Several extreme-right plots and attacks have in recent years targeted Jewish-Israeli persons or institutions. In October 2019, a 27-year-old right-wing antisemitic extremist who attacked a synagogue in Halle, killing two, brought with him that day, among other weapons, a gun with 3D-printed plastic components and explosives.142 In May 2020, French security services arrested a 36-year-old man for plotting terror attacks against the Jewish community in Limoges.143 In February 2020, a 22-year-old man was arrested on suspicion of plotting terror attacks on both Jewish and Muslim institutions in Germany. He was part of a chatgroup dubbed ‘Feuerkrieg Division’ linked to several attack plots.144 In December 2020, U.K. police arrested an 18-year-old right-wing extremist for trying to build a 3D-printed gun and plotting to shoot an Asian friend for sleeping with white women. This individual also discussed attacks on Jews working in the bank sector.145

Plots and attacks targeting politicians, the political system, or the state have become increasingly common. In June 2019, a 45-year-old right-wing extremist assassinated a pro-immigration CDU politician shooting him in the head outside his home.146 In 2020-2021, two other right-wing extremist networks plotted attacks on German ministers. Five men and one woman made plans for assassinating the Saxony prime minister via Telegram chat groups.147 Another group of four made plans in a Telegram chat group dubbed “Unified Patriots” to assassinate the German health minister, Karl Lauterbach. These four suspected terrorists were extreme anti-COVID-19-measures activists and linked to the Reichsbürger movement, an eclectic political current based on the core idea of bringing down the German republic and restoring the historical German empire.148 The movement is inspired by Qanon conspiracy theory, and in December 2022, a major counterterrorism operation cracked down on Reichsbürger extremists allegedly plotting terror attacks with a view to initiating a massive coup to topple the government.149 In late 2022, French police uncovered a plot by a right-wing conspiracy theorist and extreme anti-Covid-19-measures activist to overthrow the French government and stage terror attacks against state institutions, vaccination centers, a Masonic lodge, and prominent people.150

As Paris prepares to host the Olympics, there are active transnational extreme-right networks aiming to weaken European democracies, spread chaos, polarize and draw attention to specific movements, causes, and grievances. At the same time, the right-wing terror threat is limited compared to that posed by jihadi actors and lacks the latter’s capabilities and strategic depth gained from mother organizations in conflict zones. One factor that could amplify the threat from both left-wing, right-wing, and Islamist actors is the return of state support or influence operations, notably by Russia and Iran in the current threat environment.

Russia and Proxies

The Soviet Union supported left-wing terror groups internationally and in Europe during the 1970s and 1980s when these groups dominated international terrorism. As noted, European left-wing extremism became weakened and disintegrated after the Soviet collapse. Fast forward to the current era and Putin’s Russia has cultivated relations with right-wing movements, political actors, and extremist networks in Western and Eastern parts of Europe. Russia aims to weaken and polarize the European Union and Europe to win the war in Ukraine and ‘make Russia great again’ on the European continent.151

According to sources in European security agencies, cited by the Financial Times, Russia has significantly increased influence operations and espionage especially in former Eastern Bloc states but also in Western European countries with limited counterespionage capacity.152 The FT’s sources warned that Russia was plotting violent acts of sabotage, including bombings, arson attacks, and destruction of infrastructure, all over Europe “directly and via proxies.”153 While Russia has never been shy about targeting exiles such as the 2018 attempted killing of Sergei and Yulia Skripal with Novichok in the United Kingdom, a wider range of targets now seem to be on the table.

In April 2024, two German-Russian citizens were arrested in Germany suspected of plotting attacks on military and logistics targets.154 The two men were charged with arson on a storage facility for aid shipments to Ukraine.155 Russian involvement was also suspected in two attempts at derailing trains in Sweden.156 Other suspicious incidents mentioned in the FT coverage of this development have included explosions and fires at munition factories in south Wales (in April 2024) and in Berlin (in May 2024).157

Evidence is mounting of Russian attempts to co-opt European right-wing populist politicians, pushing huge amounts of Russian propaganda and narratives via sophisticated social media and fake news influence operations, and interacting with European right-wing extremists and terrorists.158 Russian extreme right-wing groups have for years enjoyed leeway to operate in Putin’s Russia and offered paramilitary training to Western European extremists, some of whom joined the war in Ukraine as foreign fighters from its outset in 2014.159 Investigations into several right-wing terror cases outlined in the previous section indicate indirect or direct links to Russia and Russia-based extremists. For example, the Reichsbürger extremists suspected of plotting terrorism and a coup in Germany allegedly had Russian contacts and hoped to receive Russian support and negotiate a new order for Germany after toppling the government.160

French authorities expect Russia to try to undermine the Paris Games, and are taking precautions.161 If Russia does try to play a spoiler role, it would likely be in response to President Macron’s more hardline approach against the Russian war in Ukraine. French officials point to an ongoing influence operation against the Olympics preparations, including rumors and disinformation about France’s ability to organize the Games and manage the security situation. Influence operations appear to have intensified amid the Gaza war, the Crocus attack, and statements by Macron that France does not rule out boots on the ground in Ukraine.162

Fake Russian accounts spread rumors and disinformation about French interference in Ukraine or even involvement in the Crocus attack.163 French security services allege Russia state security (FSB) was behind a campaign of spray-painting Stars of David on houses associated with Jews in Paris in October 2023 to fuel polarization over Gaza.164 French authorities also allege Russian involvement in the spray painting of red hands at the Shoa Holocaust memorial in Paris in May 2024 by three perpetrators entering France from Bulgaria.165 Furthermore, French authorities believe Russia had a hand in a social media campaign falsely claiming an unusual spread of bedbugs in Paris via Ukrainian refugees to France, seemingly aiming to create a bad image of the country in the run-up to the Paris Games.166 The French domestic intelligence agency DGSI assesses that Russia will exploit any contentious issue from pension reform to the Olympics to amplify polarization within French society.167 While influence operations and sabotage are the most likely threats associated with Russia, support for non-state terrorist networks cannot be ruled out. On June 5, 2024, French media reported that the domestic security services had arrested near Charles de Gaulle airport a 26-year-old Ukrainian-Russian from the Russia-occupied Donbass region who accidently set off an explosive in his hotel room while preparing a bomb suitable for a terror attack.168 According to a French security source, investigations clearly indicate a Russian operation, with it not being excluded that the plan was to carry out a false flag attack to pin the blame on jihadis given the explosive was of the type often associated with jihadis.169

Iran and Proxies

Since the latter 2010s, there has also been growing concern among European security services about the terror threat on European soil posed by actors linked to and supported by Iran. Unlike Russia, Iran will compete in the 2024 Paris Olympics. While the European Union maintains trade and political relations with Iran,170 the relationship has become increasingly strained due to human rights violations, the nuclear program, the conflict with Israel, and Iranian harassment and violence against exiles in Europe and threats to Jewish and Israeli people and institutions residing in Europe. All of this has been compounded by Iran’s support for Russia’s war on Ukraine. Of late, European officials have voiced growing concerns about terrorist spillover from the war between Israel and Hamas,171 including threats from Iranian proxies or allies such as Hamas itself and Hezbollah. The Iran-allied Houthi movement’s rocket attacks on ships with direct or indirect links to Israel, including European vessels, have also added to concerns about terrorism spillover, forcing the European Union to launch a maritime mission to protect vessels, personnel, and trade interests.172

Iran has a track record of violent operations in Western Europe, mainly in the shape of terrorism-style attacks on dissident exiles and on Israeli targets. A main target is the exiled opposition group Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK),173 a Marxist, feminist, and Islamist movement operating mainly out of Iraq and France, which fought on Saddam’s side in the 1980s Iran-Iraq war. In 2018, one of Iran’s ‘deadly diplomats’ recruited an Iranian couple in Belgium for a foiled plot to stage a bombing against a MEK rally in France.174 Iranian intelligence operatives acting as diplomats have been tied to numerous assassinations or plots to assassinate dissident exiles and plans to attack Israeli targets, including a plot to attack an embassy and kindergarten in Germany also in 2018.175 Since the 1990s, assassins or would-be assassins allegedly linked with Iran, the IRGC/MOIS, and Hezbollah have also been part of the effort to carry out the fatwa to avenge Salman Rushdie’s Satanic verses, including the attack on a Norwegian publisher of Rushdie’s book in 1993. Plots and attacks linked to Iranian agents have occurred across Western Europe, including among others France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Austria, Cyprus, Austria, Norway, and Sweden.176

The regional Iranian response to the Israeli campaign on Gaza has so far appeared relatively restrained. Iranian proxy Hezbollah has increased rocket attacks on northern Israel, the Iran-allied Houthis in Yemen have launched attacks against Israeli-linked ships in the Red Sea to avenge the military campaign against Gaza, and Iran responded to Israeli airstrikes on the consulate in Damascus by directly attacking Israel with missiles and drones for the first time. Yet, the scope and intensity of the attacks on Israel suggested Tehran prefers to stay below the threshold for total war.

As for facilitating international terrorism in Europe, Iran seemingly considers limited attacks on Israeli targets in Europe is one way to harm Israel below this threshold. In a recent development, Israel’s national security service Mossad publicly stated that Iran stood behind “a string of terror attacks by criminal networks on Israeli embassies in Europe since October 7,” using particularly two Swedish-based criminal networks, Foxtrot and Rumba, as proxies.177 According to Mossad and Swedish authorities, these gangs were responsible for placing a grenade on the premises of the Israeli embassy in Stockholm in January 2024 and gunshots outside the embassy on May 17, 2024.178 Mossad indicated Iran also had a hand in the throwing of two airsoft grenades179 at the Israeli embassy in Belgium following a similar modus operandi to the Swedish case.180

As for larger attacks during high-profile events such as the Paris Olympics, Tehran likely knows any attacks linked to the Iran threat network would crush what remain of Iran-E.U. relations and could decrease European sympathy for Palestinians and increase European sympathy for Israel. At the same time, while Iran supports multiple Shi`a and Sunni proxies fighting Israel (Hezbollah, Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, the Houthis, and the Hashd al-Shaabi in Iraq), these groups have their own agendas and agency are not unitary actors. These groups or sub-groups/factions could also resort to international terrorism by themselves.

In an unexpected development, in December 2023, a series of arrests in Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands allegedly intercepted terror cells linked to Hamas plotting attacks on Jewish targets in Europe. Denmark arrested three individuals tied to Hamas and a Danish criminal gang called Loyal to Familia.181 In Germany, also in December 2023, police arrested three Lebanese citizens and one Egyptian with Hamas ties,182 and in Rotterdam, Netherlands, a Dutch citizen was apprehended.183 The European investigations have not clarified as to whether the alleged plotters in Germany, Denmark, and Netherlands were interlinked. It is alleged the cell in Germany was closely affiliated with the leadership of Hamas’ military wing the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades.184 There is limited information about the further investigations into the alleged terror plot(s) in the public domain, but according to Der Spiegel’s coverage of the case, the mission of the cell in Germany was to locate a Hamas weapons cache that turned out to be in Bulgaria, and transport weapons to Germany (Berlin) for use in attacks on Israeli targets in Europe.185 Statements by Danish authorities indicated Danish Jews were at risk and that the Gaza war and Qur’an burnings may have been triggers.186 On January 13, 2024, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that “On 14 December 2023, the Danish and German security and enforcement authorities announced the widespread arrest of suspects in Europe who are now the subject of judicial proceedings. In a continuing intelligence effort, considerable information has been uncovered that proves how the Hamas terrorist organization has acted to expand its violent activity abroad in order to attack innocents around the world. Thanks to combined inter-organizational forces in Israel and abroad, a comprehensive and in-depth picture of Hamas’s terrorist activities has been revealed, including details of areas of action, targets for attacks and those involved in implementing the activity – from Hamas commanders in Lebanon to the last attackers in the operational infrastructure, as well as information on the intention to attack the Israeli Embassy in Sweden, the acquisition of UAVs and the use of elements from criminal organizations in Europe.”187

It is difficult to assess the implications of this alleged Hamas plotting in Europe without knowing for sure what was planned and by whom. If there actually were plans to stage attacks, were these plans sanctioned by the central Hamas leadership, or initiated by semi-independent or rogue cells?188 If the cells were directed from Lebanon by Hamas as publicly claimed by Israel, could there be involvement by Hezbollah or Iranian agents? If the cells were semi-independent or rogue, it could signal an increased threat from Hamas sympathizers of different stripes and add to the existing threat from individuals and cells associated with jihadism and other extremisms. If, on the other hand, the cells were sanctioned by the central Hamas organization or involved Iranian or Hezbollah elements, it would be more of a game-changer. Hamas and Hezbollah, whose military wings are proscribed as terrorist organizations by the European Union, are known to have built support networks in several European countries, but particularly in Germany and France. The coverage of the alleged Hamas plot revealed the existence of substantial and highly organized Hamas support structures across German states involved primarily in fundraising for the mother group.189 According to CNN, German security services estimate there are some 450 active Hamas-supporters in Germany.190 As for Hezbollah, the group is estimated to have some 1,000 members in Germany.191

If there is a major escalation of the conflict between Israel and Hezbollah this summer ahead of or during the Olympics, one concern is that it may change Hezbollah’s calculus when it comes to launching terrorist attacks in Europe, especially against Israeli or Jewish targets. In 2012, the group carried out a bomb attack on an Israeli tour bus in Burgas, Bulgaria, killing six.192 In a speech on June 19, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah warned that if Israel launched an operation into southern Lebanon, Hezbollah would fight Israel with “no rules” and “no ceilings.” He also threatened Cyprus with attacks if the island were to be used for operations against Hezbollah.193

Conclusion

The terrorism threat matrix facing the Paris Olympics is diverse and multifaceted. It includes both known and predictable terror threats and others that are less likely on paper but hold the potential for surprise. The diversity and breadth of the potential threats facing the Games is going to make it hard for security services and first responders to prioritize resources in a way that can enable them to keep the known threats at bay and simultaneously manage threats that may emerge from under the radar. Jihadism remains the main non-state terror threat to Western Europe, France, and the Olympics, with Islamic State Khorasan posing a clear and present danger to the Games, especially through its cyber-coach approach of guiding radicalized individuals in Europe to launch attacks. “Threat is defined as capability and intent, and ISK have both,” Richard Walton, the former head of Counter Terrorism Command at the UK Metropolitan police, states in an interview published in this issue of CTC Sentinel. “In my assessment, [ISK] is the biggest threat during this summer of sport.” Underlining the threat, on May 31, an Afghan national motivated by Islamist ideology murdered a police officer in Mannheim,194 and with less than two months to go before athletes were due to arrive in Paris, French police thwarted a plot by a teenager being cyber-groomed by ISK to target an Olympic soccer venue during the Games. There is also concern about the terrorist threat from left-wing extremism and a significant right-wing terror threat, which could see violence targeted at the Paris Games.

Some radicalized activists might view the Games as an opportunity to draw attention to their cause through violence. Jihadis may groom frustrated activists who are vulnerable to extremist messages and recruit them for terrorist acts.

Western European security services are warning of a more aggressive Russia increasing influence operations to cause polarization and weaken European support for Ukraine, while preparing sabotage on infrastructure or other violent operations on European soil. Russia has been cultivating Western European right-wing politicians, extremists, and terrorists who could be weaponized in the conflict over Ukraine. Russia may otherwise amplify already existing threats through influence operations and disinformation.

Finally, the Iran threat network also potentially poses a threat to the Paris Games. Tehran has been targeting exiles and Israeli symbols and people via its spies, the IRGC, and Hezbollah. Hamas itself could pose a threat and so could Hezbollah, with or without Iran’s blessing, especially if there is an escalation in hostilities between Hezbollah and Israel in the coming weeks. CTC

Petter Nesser is a senior researcher at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) and the author of Islamist Terrorism in Europe (Hurst/OUP, 2015, 2nd edition 2018). X: @petternessern

Wassim Nasr is a journalist and jihadi movements specialist with France 24 and senior research fellow at the Soufan Center (TSC). He is the author of Etat Islamique, le fait accompli (Tribune du Monde, Plon, 2016). X: @SimNasr

© 2024 Petter Nesser, Wassim Nasr

Substantive Notes

[a] In late May, the chief of the Russian internal security service FSB acknowledged that the terrorists were “coordinated via the internet” by ISK members but claimed without offering any evidence that Ukraine may have facilitated the attacks. “Russia says Islamic State behind deadly Moscow concert hall attack,” France 24, May 24, 2024.

[b] JPED currently covers data from December 1994 until June 1, 2024. The public dataset only covers attack activity until January 1, 2022. The public dataset will be updated in December 2024.

[c] According to a French security source, France has the highest ratio in Europe of terrorism victims by firearms. The source stated the logistical challenges of producing explosives makes such plots rare in France. Author (Nasr) communication with French security source, June 2024.

[d] There have been Islamic State-inspired attacks launched in France by plotters previously convicted of jihadi activity not connected to the Islamic State. For example, see “French jihadist murders police couple at Magnanville,” BBC, June 14, 2016.

[e] In a 2016 interview in this publication, the head of Counter Terrorism Command at the UK Metropolitan Police Richard Walton stated, “it’s clear there’s an availability of firearms on the European mainland that is just not replicated here in the UK. And we’ve got some sea around us, so it’s much more difficult to get guns into the UK. This is a critical difference in the UK, even compared to our counterparts in Europe, in terms of the threat from Daesh and marauding terrorist attacks.” Paul Cruickshank, “A View from the CT Foxhole: An Interview with Richard Walton, Head, Counter Terrorism Command, London Metropolitan Police,” CTC Sentinel 9:1 (2016).

[f] As noted by Tore Hamming in this publication, “on October 16, just nine days after the Hamas attack on Israel, Abdessalem Lassoued, a 45-year-old Tunisian living in Brussels, attacked and killed two Swedish soccer fans while wounding another. Lassoued initially managed to escape, but after an extensive manhunt, he was killed the following morning in a café in the Schaerbeek district of the city. While it appears that his motivation for specifically targeting Swedish nationals, identified through their Swedish soccer shirts, was the Qur’an burnings that took place in Sweden over the summer and fall, postings on his social media profile including images of the Dome of the Rock suggest that the war in Gaza was a contributing factor or at least a matter of concern for the perpetrator.” Tore Hamming, “The Beginning of a New Wave? The Hamas-Israel War and the Terror Threat in the West,” CTC Sentinel 16:10 (2023).

[g] The perpetrator recorded audio and video on his phone before the attack in which he pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and declared his hatred for France, the French, democracy, and the educational system. In the audio-message in Arabic, he expressed support for Muslims in Iraq, Asia, and the Palestinian territories (without linking it to the war following Hamas’ October 7 Gaza flood campaign). “French prosecutor says alleged attacker in school stabbing declared allegiance to Islamic State,” Pais, October 17, 2023.

[h] The attacker expressed anger to investigators that “so many Muslims are dying in Afghanistan and in Palestine.” Dominique Vidalon and Gilles Guillaume, “Knifeman kills German tourist, wounds others near France’s Eiffel Tower,” Reuters, December 2, 2023.

Citations

[1] Victor Goury-Laffont, “Macron: IS wing that claimed Moscow carnage also attempted attacks in France,” Politico, March 25, 2024.

[2] Toky Nirhy-Lanto, “Attentat de l’Etat islamique à Moscou : Strasbourg a été visé par cette organisation en 2022 révèle le Premier ministre, Gabriel Attal,” France 3, March 26, 2024; Ingrid Melander, “Macron says Islamists who hit Russia had tried to attack France,” CTV News, March 25, 2024.

[3] “Islamic State’s claim on Moscow shooting: ‘History’ of attacks on Russia,” France 24, March 23, 2024.

[4] “Beware, global jihadists are back on the march,” Economist, April 29, 2024.

[5] Grace R. Rahman, Gregory N. Jasani, and Stephen Y. Liang, “Terrorist Attacks against Sports Venues: Emerging Trends and Characteristics Spanning 50 Years,” Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, March 20, 2023.

[6] Kim Willsher, “Brussels terror cell ‘planned to attack Euro 2016 tournament,’” Guardian, April 11, 2016.

[7] “Suspected IS supporter arrested at Cologne airport,” Deutsche Welle, June 9, 2024.

[8] Guy Chazan, “Germany warns of Moscow-style terror attacks,” Financial Times, June 18, 2024.

[9] Author (Nasr) communication with French security source, June 2024.

[10] Emma Lofgren, “Swedish police pleased after Eurovision weekend passes peacefully,” Local Sweden, May 13, 2024.

[11] Richard Walton, “Protecting Euro 2016 and the Rio Olympics: Lessons Learned from London 2012,” CTC Sentinel 9:6 (2016).

[12] “French jihadist murders police couple at Magnanville,” BBC, June 14, 2016.

[13] “European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) 2023,” Europol, June 14, 2023 (updated October 26, 2023).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Tariq Tahir, “Paris Olympics: ISIS circulates ‘detailed attack manuals’ on using drones to hit games,” National, June 5, 2024.

[16] Petter Nesser, “Military Interventions, Jihadi Networks, and Terrorist Entrepreneurs: How the Islamic State Terror Wave Rose So High in Europe,” CTC Sentinel 12:3 (2019).

[17] Alexandria Sage and Chine Labbé, “French attacks inquiry centers on prison ‘sorcerer’ Beghal,” Reuters, January 15, 2015.

[18] “Man accused of fatal stabbing near Eiffel Tower faces terror charges,” France 24, June 12, 2023.

[19] Clea Caulcutt, “Macron’s explosive home front in the Gaza war,” Politico, April 13, 2024.

[20] Petter Nesser, “Introducing the Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED),” Journal of Peace Research 61:2 (2024).

[21] “Beware, global jihadists are back on the march.”

[22] Based on updated data from FFI’s Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED). The dataset is presented in Nesser, “Introducing the Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED).”