Abstract: When Hamas took over the Gaza Strip by force of arms in 2007, it faced an ideological crisis. It could focus on governing Gaza and addressing the needs of the Palestinian people, or it could use the Gaza Strip as a springboard from which to attack Israel. Even then, Hamas understood these two goals were mutually exclusive. And while some anticipated Hamas would moderate, or at least be co-opted by the demands of governing, it did not. Instead, Hamas invested in efforts to radicalize society and build the militant infrastructure necessary to someday launch the kind of attack that in its view could contribute to the destruction of Israel. This article explores the road from Hamas’ 2007 takeover of Gaza to the October 2023 massacre.

The brutal Hamas-led October 7 attack on Israeli communities near Gaza represented a tactical paradigm shift for the group, which was previously known for firing rockets at Israel, carrying out suicide bombings targeting city buses or cafes, and conducting roadside attacks and shootings on restaurants and bars. October 7 was something different. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, after viewing evidence of the attackers’ brutality, said that it “brings to mind the worst of ISIS.”1 The Secretary was painfully blunt in describing the attack: “Babies slaughtered. Bodies desecrated. Young people burned alive. Women raped. Parents executed in front of their children, children in front of their parents.”

The group’s explicit targeted killing and kidnapping of civilians baldly contradicts Hamas’ articulated revised political strategy since it took control of the Gaza Strip in 2007.a Ironically, Hamas’ sharp tactical shift only underscores that the group never abandoned its fundamental commitment to the creation of an Islamist state in all of what it considers historical Palestine and the destruction of Israel.2

Moreover, Hamas has always described itself as a resistance organization, pushing back firmly against the ‘terrorist’ designation Israel, the United States, the European Union, and many others apply to the group. But by any measure, the October 7 attack is one of the worst acts of international terrorism on record. Thousands of Hamas operatives, aided by small numbers of terrorists from other groups such as Palestinian Islamic Jihad, murdered some 1,200 people in Israel,b wounded thousands, and took at least 240 hostages with nationals from more than 40 countries.3

As such, the Hamas massacre demands a re-examination of a critical point in Hamas history: its 2007 takeover of the Gaza Strip by force of arms aimed at fellow Palestinians, and its initiation of its governance project in Gaza. Despite wide-held beliefs that the shift to governance led to a more moderate Hamas, it is now clear that Hamas did not moderate—nor was it co-opted by the responsibility of providing public services to its constituents—but rather it prioritized building and maintaining its militant and terrorist capabilities. The October 7 attack obliterates all Hamas claims to legitimacy as a political actor.

This article will explore where Hamas came from, how the group used its governance to further its long-term goals, and how the group played a long game, obfuscating its commitment to employing violence to replace the State of Israel with an Islamist Palestinian state in all of what the group considers historic Palestine.

Background: Founded in Violence, Driven from the Bottom Up

Founded in 1987, Harakat al-Muqawwama al-Islamiyya, commonly known as Hamas, emerged out of the Muslim Brotherhood in Palestine, where it gained popularity among Palestinians through its extensive social services.c The group released its first official statement as Hamas on December 14, 1987,4 before publishing its organizational charter through the Islamic Association for Palestine, a Hamas front organization in Chicago, in August 1988.5 The group’s charter outlined its connection to the Muslim Brotherhood,6 highlighted its focus on Palestine, nationalism, and Islamic law (sharia),7 and underscored the group’s fundamental rejection of any negotiations with Israel. For Hamas, only through violence—specifically jihad—could the group achieve its goal: the complete destruction of Israel and creation in its place of an Islamist state in all of historic Palestine.8 Hamas’ charter also conflated Jews with Israel, and is ripe with historical anti-Semitic tropes.9 Hamas’ official debut corresponded with a growing discontent among many Palestinians with the failed Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), an umbrella organization dominating Palestinian politics at the time.10

Its Muslim Brotherhood roots are a vital part of understanding who Hamas is as an organization, and how it seeks to garner support—both internally and externally. Specifically, its modus operandi has focused on revolution-from-below, participating in aspects of the modern political systems, including its eventual participation in the 2006 Palestinian elections, in order to create a government one day ruled by sharia.11 In doing so, Hamas seeks to frame its “Islamization” of society as a “choice,” driven by the populous that lives under it. Despite this framing, Hamas has used violence and pressure countless times on civilian populations in order to achieve its goals of a ‘traditional’ Islamic society.

The spiritual founder of Hamas, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, rejected the idea that Hamas’ political and social wings were separate from its military wing, the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades: “We cannot separate the wing from the body. If we do so, the body will not be able to fly. Hamas is one body.”12 Hamas itself sees three areas of the group’s activity—political, social and charitable, and military—as mutually reinforcing. Each of these areas serve to benefit the other, and all are aimed at furthering the group’s overarching goal of creating a culture of resistance and destroying Israel.13 As such, Hamas deemed the mingling of funds given to the group as legitimate, as it considers the social services it provides a jihadi extension of its terrorist attacks. Hamas has a long history of raising funds through its charity, social welfare, and proselytizing organizations (collectively known as the Hamas dawa), including funds intended for terrorist and militant purposes. In a 1992 letter between two Hamas operatives that was seized by the FBI and later introduced as evidence in federal court, the two noted how when Hamas was still young, before the Hamas military wing had its own budget, Hamas operatives would “take not less than 50,000 from the monthly allowance of the dawa” for military expenses.14

Overseeing all of Hamas’ activities is its Majlis al-Shura, the group’s overarching political and decision-making body. Hamas also maintains geographically-based leadership structures representing the interests of the group in the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, within Israeli prisons, and among the group’s external leadership. The Hamas external leadership was based in Jordan until authorities there expelled the group’s leaders in 1999.15 Hamas external headquarters then moved to Syria, where it remained until the group broke with the Assad regime over the Syrian civil war, after which Hamas leaders left Damascus for Turkey, Lebanon, Qatar, and (briefly, during the Morsi-led Muslim Brotherhood government) Egypt.16 Hamas also maintains representative offices and personnel running Hamas investments and companies throughout the Middle East and North Africa.17 Since the Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip in 2007, the Gaza-based leadership has become the most prominent given its control of territory and the financial and military advantages that presents. Today, the leader of Hamas in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, working in tandem with Gaza-based Hamas militant leaders like Mohammed Dief, are in effect more powerful than the group’s overall leader, Ismail Haniyeh, who was once based in Gaza but moved to Qatar in late 2019.18

Since its foundation, violence has been a central part of Hamas and its goals.d As Article 12 of the 1988 Hamas charter notes:e

Nationalism, from the point of view of the Islamic Resistance Movement, is part of the religious creed. Nothing in nationalism is more significant or deeper than in the case when an enemy should tread Muslim land. Resisting and quelling the enemy become the individual duty of every Muslim, male or female. A woman can go out to fight the enemy without her husband’s permission, and so does the slave: without his master’s permission.

Over time, Hamas released several other documents that explained its goals and ideals. For example, in the mid-1990s, the European Commission asked Hamas to clarify its “objectives, values and ideals,” which led Hamas to release a document titled “This is what we struggle for.”19 While this, and another memorandum written in 2000 just before the Second Intifada, were written in an overall softer tone than the Hamas charter, both documents continued to acknowledge Hamas as a violent Islamist movement struggling for “the liberation of Palestine” that opposed Israel’s right to exist as a state.

Since its founding, Hamas has committed countless acts of violence against both military and civilian targets, including bombings, rocket and mortar attacks, shootings, stabbings, kidnappings and attempted kidnappings, and car ramming attacks. With the onset of the Second Intifada in 2000, Hamas attacks dramatically increased. Between 2000 and 2005, 39.9 percent of the 135 suicide attacks carried out during the Second Intifada were executed by Hamas.20 According to the Global Terrorism Database, Hamas killed 857 people and injured 2,819 between 1987 and 2020.21 Intended to terrorize not only the targeted individuals but also the general Israeli population, Hamas attacks have been indiscriminate in nature.f

From its inception, Hamas attacks were intended to instill fear in the civilians who comprise the local population so that they will either leave the land Hamas claims belongs to the Palestinians or, at a minimum, pressure their leaders to give concessions to Hamas, such as obtaining the release of Palestinian prisoners held in Israeli prisons. For example, both before and after the so-called “Shalit deal” in which Israel released over 1,000 Palestinian security prisoners in exchange for one Israeli soldier captured in Gaza in 2006—Gilad Shalit22—Hamas has ceaselessly engaged in kidnappings and attempted kidnappings in hopes of gaining a valuable bargaining chip to use in future negotiations with Israel.23

For Hamas, eager to create a “culture of resistance,”24 its bottom-up approach to shaping popular support for violence meant engaging with both men and women. While some parts of its charter were aimed at wide audiences, Articles 17 and 18 specifically note women’s unique role in Hamas. Stressing women as vital to the dissemination of their ideology, the Hamas charter calls Muslim women the “maker of men,” noting that “[w]oman in the home of the fighting family, whether she is a mother or a sister, plays the most important role in looking after the family, rearing the children and [imbuing] them with moral values and thoughts derived from Islam.” One of the reasons Hamas emphasizes women’s education is so that female supporters are knowledgeable enough to pass on Islam and the organization’s ideology to their children.g Hamas has organized events on women’s issues since its inception, and these have been attended by the highest echelons of the organization.25 The group even established the “Islamic Women’s Movement in Palestine” in 2003,26 highlighting the strategic incorporation of women even prior to governance.h

Despite Hamas’ transition into governance, most countries around the world do not engage in formal diplomatic relations with the group, due to the group’s continued engagement in violent activities.i The following section will explore Hamas’ governance project.

Governance: Playing the Long Game on Their Own Terms

From its creation in late 1987 until its decision to participate in Palestinian elections held in early 2006, Hamas operated as a sub-state actor engaged in a spectrum of activities including terrorism, social welfare provision, charity, religious proselytization, and local political activities within professional syndicates and student groups on university campuses.27

Active as a violent non-state actor for almost 20 years, Hamas entered legislative politics with support from local populations that benefited from its largesse and were frustrated with the corruption of the group’s primary Palestinian political rival, Fatah. For Hamas, efforts to win local support can have a significant pay-off in its bid for international legitimacy.28 Hamas’ pivotal juncture came in the January 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) elections. The group won a majority 74 out of 132 seats in the PLC as part of the “Change and Reform” bloc, and, notably, ran with both men and women on the ballot.29 For the first time since its formation, Hamas joined the Palestinian government. Election results led to the formation of a new government under Hamas’ Ismail Haniyeh, which heightened tensions with its political rival, Fatah. Hamas’ electoral success signified the first time an Islamist group democratically took power in the Arab world, with Hamas’ governance style being described as an “Islamic democracy of sorts,” in which the group saw compatibility between democracy and Islamism.30

In 2006, Fatah and Hamas agreed to a short-lived national unity government to govern the areas of the West Bank under PA authority and all of the Gaza Strip.31 During this brief attempt at unity, Hamas tried to change the Palestinian political system from within and move the Palestinian Authority away from security cooperation with Israel and its pursuit of a two-state solution, and toward violent competition with Israel in pursuit of its destruction and the creation in its place of a single, Islamist, Palestinian state.32

For some, the very fact that Hamas decided to participate in elections for seats in the Palestinian Legislative Council—itself a product of the Oslo peace process—was a sign that the group could, and maybe already was, moderating its hardline positions.33 Indeed, more hardline jihadis such as Usama bin Ladin lambasted Hamas, saying the group had “forsaken their religion” by participating in elections.34

As for Hamas, the group’s leaders were crystal clear that Hamas’ participation in elections did not mean the group had moderated its position calling for the destruction of Israel. Gaza was to be a launchpad to further this goal, not a distraction from it. In an interview with an Israeli newspaper (not buried in an obscure Arabic publication), senior Hamas official Manmoud Zahar explained: “Some Israelis think that when we talk of the West Bank and Gaza it means we have given up our historic war. This is not the case.” And Hamas’ idea of parliamentary participation was equally clear, Zahar continued: “We will join the Legislative Council with our weapons in our hands.”35

Perhaps, then, it should not have been a surprise when in 2007 Hamas turned its guns on its fellow Palestinians, took over the Gaza Strip by force of arms, and split the Palestinian polity in two.36 Between January 2006 and June 6, 2007, more than 600 Palestinians were killed in factional fighting.37 And in one week alone, between June 7, 2007, and June 14, 2007, more than 160 Palestinians in Gaza were killed in factional fighting, with at least 700 injured.38 Tensions with Fatah continued, with reports that Hamas threw Fatah supporters off rooftops in 2009.39

Hamas has been the de facto ruler in Gaza since mid-June 2007, running the administration of government and leveraging the same to build up its military capabilities to fight Israel. This resulted in two entities governing the Palestinian people: Hamas ruling Gaza and the Fatah-dominated Palestinian Authority (PA) governing the West Bank. That said, Hamas in Gaza is not recognized as a legitimate government by the United Nations, other multilateral organizations, or the vast majority of countries around the world, including the United States. Hamas does not coin its own currency.40 The legitimacy of Hamas’ continued control of Gaza is regularly questioned by the PA, Israel, and the international community as there have been no elections since 2007.

Since its formation, Hamas has received and continues to receive significant financial and other support from Iran.41 Ahmed Yousef, a Hamas leader and former advisor to Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Haniyeh, confirmed this in January 2016, when he stated that “the financial and military support Iran provides to the movement’s military wing has never stopped, it has been reduced over the past five years.”42 While the exact amount has fluctuated over the years, Iranian funds to Hamas have covered operational costs—weapons, intelligence, sanctuary, safe haven, operational space, and training—as well as long-term organizational costs, such as leadership, ideology, human resources and recruitment, media, propaganda, public relations, and publicity.43ハEven when as a result of the Syrian civil war Hamas broke with the Assad regime in Syria, where it long maintained its external headquarters, Iran cut some funding for the Hamas political bureau but maintained funding for Hamas military activities.44

Iran is not the only state actor offering support to Hamas. For decades prior to the Syrian civil war, the Assad regime provided support to the group.45 More recently, Qatar has publicly—with Israel’s knowledge and acquiescence—provided Hamas monthly stipends to pay for fuel for electricity and to help Hamas pay public sector wages.46 Moreover, Ismail Haniyeh, Hamas’ top political leader, along with several other senior Hamas leaders, lives in luxury in Qatar.47 Since October 7, Qatar has utilized its unique relationship with Hamas to facilitate hostage negotiations and has publicly indicated it is open to reconsidering Hamas’ continued presence in Doha.48

Through its governance, Hamas developed the necessary bureaucracy to collect taxes, customs duties, and bribes, as well as extortion and racketeering schemes, through which the group raised significant funds.49 Eventually, Hamas’ income from local governance of Gaza would dwarf its funding from Iran by a factor of about four to one.50 Indeed, Hamas has used its governance to entrench its system of control and continue its military engagement.

Entrenching the System of Control

Long before Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip, the group invested in grassroots efforts to entrench its position within society and create broad public support for its goal of destroying Israel.j In the years that followed, Hamas took advantage of the benefits of governance to deliver educational and social service programs that instilled its “culture of resistance” in Gazan society.51 On Hamas’ payroll were Gazan men and women who worked in their police, and as teachers, doctors, administrators, and more. A critical component of Hamas’ ideology has been transforming the ethno-political Palestinian struggle into a religious conflict, which allows the group to inspire Palestinians to reject any sort of compromise or peaceful solution to the ongoing conflict.

Hamas emphasizes its campaign of radicalization targeting Palestinian youth. In 2010, on its Al-Qassam Brigades website in English, Hamas announced that it operated 800 youth summer camps, reaching over 100,000 male and female students. According to the group, the “Hamas summer games is an annual enterprise aim[ed] to convey joy and entertainment for Palestinian children and youth who suffer from cruelty of Israeli siege imposed after Hamas great democratic win.”52 Arguing that youth are the most vital part of Palestinian society, Hamas claims “[t]he Islamic ideology adopted in Hamas summer games, meets with the Islamic values of the Palestinian people.” Hamas combines youth social services with its ideology, as seen by the fact that the theme of the summer camp that year was “Our Aqsa Mosque, Our Prisoners, Freedom Is Our Appointment,”53 not the catchiest of summer camp names.

Hamas has used the tactic of exposing Gazan children to such radical messages at a young age in both recreational institutions and schools. In 2013, Hamas issued a new education law that excluded male teachers from girls’ schools and segregated classes by gender after age nine.54 Hamas framed this as a decision to “codify conservative Palestinian values into law.”55 Hamas has argued that women have agency to decide whether or not to wear a hijab, though the group has also noted that doing so is a religious obligation.56 Hamas’ actions, however, did not always reflect this framing. To assist in the internalization of its ideals, Hamas exerted pressure mainly through “virtue” campaigns seeking to discourage “Western” behaviors.57 In 2010, the group enforced the removal of “immodest” mannequins, which it argued was a policy derived from the complaints of ordinary Gazans.58 While Hamas has not codified all of its behavioral strictures into law, in 2016, its police officers began to penalize driving instructors who did not have a chaperone for female students,59 and in 2021 a Hamas-appointed judge sought to require a male guardian’s permission for women to travel outside of Gaza.60

To be sure, Hamas leverages its position in Gaza to radicalize Palestinians to support its commitment to violence. After taking control of Gaza, Hamas embarked on a considerable public relations campaign, focusing on culture and the arts to glorify violence against Israel. For instance, in July 2009, Hamas premiered the feature-length film Emad Akel, celebrating the life of a leading Hamas terrorist killed by Israeli troops in 1993. Written by hardline Hamas leader Mahmoud Zahar, the film was screened at the Islamic University in Gaza City and dubbed by Hamas interior minister in Gaza Fathi Hamad as the first production of “Hamaswood instead of Hollywood.”61

Similarly, Hamas’ Al Aqsa Television produced a children’s show featuring a Mickey Mouse lookalike named Farfur who praised “martyrs” and preached Islamic domination. After being roundly condemned, including being described as “pure evil” by Walt Disney’s daughter, Hamas ran one final skit in which Farfur refused to sell his land to an Israeli, who then murdered the Palestinian mouse.62 The young Palestinian girl presenting the skit commented, “Farfur was martyred while defending his land.” He was killed “by the killers of children.”63 Farfur was quickly replaced with a new character, Nahoul the Bee: “I want to continue in the path of Farfur, the path of Islam, of heroism, of martyrdom and of the mujahedeen … We will take revenge of the enemies of Allah.”64 Most recently, the program introduced Nassur, a stuffed bear who called for “slaughter” of Jews “so they will be expelled from our land.”65 Notably, in 2016, the U.S. State Department designated Fathi Hammad himself as a specially designated terrorist for his ongoing terrorist activities on behalf of Hamas.66

Hamas has faced pushback to some of its politics, such as its promotion of “traditionalist” behaviors for men and women. For example, female lawyers fought back against a 2009 Hamas-appointed judge’s ruling which enforced a new uniform that mandated wearing a hijab and jilbab. In response to pressure, Hamas withdrew the decision, citing a misunderstanding.67 Additionally, public protests erupted in February 2021 after a Hamas-appointed Higher Shari’a Council judge ruled that women required permission from a male guardian to travel outside of Gaza.68 Gazan protests drove the court to amend the law, rewriting it to allow male guardians to petition the court to prevent a woman from traveling.69 Protests also arose in 2019 and 2023 against living conditions in Gaza under Hamas, both of which Hamas violently suppressed.70

Notwithstanding such protests, Hamas has not tolerated any real challenge to its governing authority. In 2009, for example, Hamas security forces raided a mosque affiliated with a salafi-jihadi group that challenged Hamas’ authority in Gaza, killing 24 and wounding 130.71

Continued Military Engagement and Preparation

Even as Hamas entrenched its political control of Gaza, it significantly expanded its security, militant, and terrorist cadre; developed domestic weapons production capabilities; dug tunnel networks to smuggle goods and covert weapons; and facilitated militant activities.72 Hamas continued to engage in terrorist activities targeting Israel, instigated rocket wars with Israel, and invested significant time, energy, and funds into militant infrastructure such as rocket production and tunnel networks in preparation for future military engagements with Israel.

Despite periodic talk of ceasefires with Israel and reconciliation with its Palestinian political rival, Fatah, Hamas continued to engage in a wide array of militant and terrorist activities targeting Israel.73 Shooting attacks and launching incendiary balloons were not uncommon along the border between Israel and the Gaza Strip.74 Israeli communities near the Gaza Strip became accustomed to the firing of rocket-propelled grenades and mortar shells from Gaza toward their communities.75 From time to time, Hamas operatives placed explosives along the Gaza border fence.76 And for years, Hamas invested millions of dollars in an underground tunnel network—used by the group to smuggle weapons from Egypt, carry out attacks into Israel, and hide its operations and weapons production from Israel’s above-ground surveillance capabilities.77 These were purposefully dug near and under schools, mosques, and U.N. facilities.78 The placement of the tunnels near U.N. facilities was purportedly intended as a preventive measure, using these as human shields against an Israeli attempt to destroy the terror infrastructure.79

Israeli and Palestinian Authority officials also point to Hamas’ plots to target PA officials and instigate a coup to take over the PA. In 2009, for example, Palestinian security forces in the West Bank seized $8.5 million in cash from arrested Hamas members who plotted to kill Fatah-affiliated government officials. Palestinian officials reported that some of the accused had “recently purchased homes adjacent to government and military installations, mainly in the city of Nablus” for the purpose of observing the movements of government and security officials. Security forces also seized uniforms of several Palestinian security forces from the accused Hamas members.80 Israeli and PA authorities thwarted another Hamas coup attempt two months later, this one overseen by Hamas external leadership based in Turkey and operatives in Jordan.81 PA officials warned of still more Hamas coup plots in 2019.82

Meanwhile, working closely with Hezbollah, Hamas also slowly developed a terrorist capability in Lebanon that it could use at some point in the future to target Israel from more than one front at a time. In 2017, not long after Hamas leader Salah al-Arouri relocated from Turkey to Lebanon, the head of Israel’s Shin Bet security service warned that Hamas was setting up a base of operations in Lebanon. This was intended to complement the group’s main center of gravity in Gaza, he added, where the group was continuing “to invest considerable resources in preparation for a future conflict [with Israel], even at the cost of its citizens’ welfare.”83 Fast-forward to 2023, and Hamas’ long-term planning in Lebanon paid off. In June 2023, Hamas operatives fired rockets into Israel from Lebanon.84 And in the weeks following the October 7 massacre, Hamas again fired rockets at Israel from Lebanon in an attempted effort to encourage Hezbollah to open a second front with Israel and draw Israeli troops away from Gaza.85

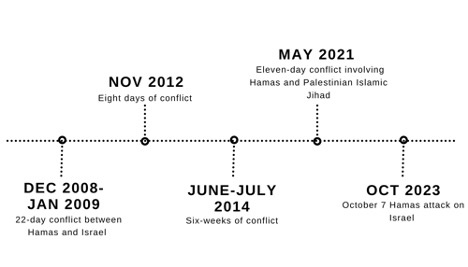

Since Hamas took over the Gaza Strip by force in 2007, Hamas and Israel have had several ‘mini wars,’ including in 2008-2009, 2012, 2014, 2021, and now the most recent full-scale war sparked by the October 7 attack (see Figure 1). Hamas struggled to find ways to target Israel, despite the restraints of governance. The group evolved its strategy over time to employ new methods of targeting its primary threat—the Israeli state—but continued to make use of tried and trusted methods, including terror tunnels, rockets, and other hallmarks of the group’s decades-long history of violent action.

Additionally, Hamas regularly sought to instigate violence in the West Bank, and periodically managed to carry out attacks there despite Israeli and PA security efforts to counter terrorism. Most notably, in August 2014, Hamas operatives kidnapped three teenage Israeli boys—one of whom was also an American citizen. The operation was led by Hamas operatives from the West Bank, but funded by Hamas operatives in Gaza through the al-Nour Association, a Hamas-affiliated charity in Gaza.86 From a conference in Turkey, Hamas leader Salah al-Arouri took credit for the operation, explaining the goal had been to spark a new Palestinian uprising.87

Al-Arouri has always been particularly focused on fanning the flames of violence in the West Bank, which is where he cut his teeth as a young Hamas operative himself.88 This was especially true in the period following the summer 2014 war. Just in 2016, 114 local Hamas cells were apprehended in the West Bank, while only 70 were apprehended in 2015.89 One cell, broken up near Hebron in February 2017, had been receiving instructions online from Hamas commanders in Gaza to carry out shooting, kidnapping, and explosives attacks in the West Bank and Israel, including a bus station, a train station, and a synagogue.90 Another attempted kidnapping plot was foiled a few weeks earlier, resulting in the seizure of large quantities of ammunition, two AK-47s, three pistols, and a shotgun from a West Bank cell.91

A Shift? Softening the Language

Since wresting control of Gaza, Hamas has strived to portray itself as a legitimate political actor and representative of Palestinians in Gaza—one less focused on violence, even operating with a semblance of foreign policy objectives. The group also operated several social media accounts, including an official Twitter account, to engage with the general public. One academic study examining Hamas’ Twitter account found that between 2015 and 2018, the group mostly tweeted about its internal governance and foreign policy, with the smallest focus on “resistance.”k

Even earlier, in 2009, Hamas leader Khaled Mishal offered to cooperate with U.S. efforts to promote a peaceful resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict.92 Mishal stated that Hamas was willing to engage in a ceasefire with Israel and approve a new Israeli-Palestinian status quo, based on the 1967 borders, a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip with its capital in East Jerusalem.93 Such sentiments were echoed by Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh in 2017, who stated that “while we are not opposed to the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state, with Jerusalem as its capital, on the basis of the 1967 territories, we refuse settlements and we adhere to our strategic choice not to recognize Israel.”94

Yet at other times, Mishal, Haniyeh, and other senior Hamas leadership have outright refused to consider political compromise, instead asserting that violence is necessary for the group to achieve its stated goals. For example, at a 2009 speech in Damascus, Mishal insisted, “We must say: Palestine from the sea to the river, from the west to the occupied east, and it must be liberated. As long as there is occupation, there will be resistance to the occupation.”95 Violence, Mishal stressed, “is our strategic option to liberate our land and recover our rights.”96

The inconsistency in Hamas’ messaging was, at least in part, a result of its internally conflicted nature. Hamas—the government—seems to recognize that it must at least appear moderate for political expediency in an effort to achieve near-term political goals, like opening border crossings into Gaza for trade. In particular, Hamas has been eager to gain access to building materials and financing to rebuild infrastructure destroyed during each round of fighting.97

The sometimes-conciliatory tone of Hamas leaders public messaging is belied by the group’s continued violent actions and radicalization on the ground, as well as the rise to prominence of violent extremist leaders within the group’s local shura (consultative) councils.98 Indeed, the discrepancy between Hamas’ periodically softer messaging and its consistently hardline activities has underscored the group’s discomfort with the ideological crisis presented by its governance project in Gaza.

This was further highlighted by the rhetorical shift in its May 2017 “Document of General Principles and Policies.” Seen by some as an update to its 1988 charter, the document—which did not supersede the previous charter, despite the new language—adopted what seemed like a softer, more moderate tone. In the document, Hamas dropped reference to its Muslim Brotherhood roots and seemingly presented itself as a more “centrist” alternative to global jihadi organizations like the Islamic State and secular nationalist groups like the Palestine Liberation Organization. Hamas also highlighted that it believed in “managing its Palestinian relations on the basis of pluralism, democracy, national partnership, acceptance of the other and the adoption of dialogue.” And for the first time, the group acknowledged in writing the possibility of a Palestinian state drawn along the borders that existed in 1967. But rhetoric aside, Hamas’ actions at that time also offered a clear indication of the group’s continued hardline militancy.

Hamas’ so-called moderation was aimed at widening its international appeal at a time when the group faced multiple challenges, including a dismal economic situation in Gaza—most recently underscored by the energy crisis in Gaza—and strained relations with Egypt, which has violently suppressed Hamas’ parent organization, the Muslim Brotherhood. And despite being hailed as a sign of moderation, the document still included less friendly sections, including a rededication to armed resistance to liberate all of Palestine: “Resistance and jihad for the liberation of Palestine will remain a legitimate right, a duty, and an honor for all the sons and daughters of our people and our umma [global Islamic community],” the document stated.

Even as Hamas was trying to change its tune, its parallel militant activity spoke volumes about the group’s true intentions. After Yahya Sinwar became the group’s leader in Gaza in 2017, the internal balance of power shifted from Hamas external leadership to officials inside Gaza. At this time, Hamas weathered a period of diminishing foreign relationships with longtime partners, including a break with Syria’s Assad regime and the ouster of Mohamed Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt. Sinwar’s tenure has also seen mounting influence exerted by two overlapping Hamas constituencies: prisoners and the military wing, both of which Sinwar has belonged to.99

In 2021, Palestinians were scheduled to vote for new legislators, and the Hamas list stood out for its sheer number of hardline militant candidates. These included Hamas members with known ties to deadly terrorist attacks, and several members who, like Sinwar, were released from Israeli prisons under the Shalit deal100—once again highlighting that there is no distinction between the group’s political activities and its military wing. Some old-guard Hamas leaders appeared in the top ranks as well, including number-one candidate Khalil al-Hayya and Nazar Awadallah, who challenged Sinwar in the group’s recent internal elections. Yet, two-thirds of the candidates were under age 40, according to Al-Monitor.101

Hamas has demonstrated its staying power in a competitive and often unforgiving institutional environment, including numerous challenges to its governance from both the PA and violent Islamist groups, including PIJ and the Islamic State. It has maintained control and adapted when necessary to stay in power.102 For example, Hamas has previously accepted fragile calm with Israel, though reluctantly, to stabilize Gaza’s economic situation,103 and in March 2021, the group appointed a woman, Jamila al-Shanti, to its Political Bureau for the first time.104 Hamas has also attempted to expand its political footprint, encroaching on Fatah strongholds in the West Bank through participating in student elections.105

As it turned 35 in 2022, Hamas unabashedly highlighted what it considers to be its most admirable traits in its continued attempt to gain international legitimacy. It brought attention to its self-proclaimed democratic rule allegedly supported by Gazans, alleged gender inclusivity, and its multi-language messaging aimed at local and international audiences.106 Hamas hoped that by distracting Israeli and international attention away from its violent activities, it would be able to obfuscate its core, violent objectives. And yet, despite changes in Hamas rhetoric, as the events of October 7 underlined, the group remained committed to its original goal of Israel’s destruction by any means necessary, and establishing a Palestinian state in its place with itself as its leader.

Conclusions

The Hamas governance project in Gaza presented the group with a critical ideological and tactical crisis. Hamas was forced to choose between engaging in acts of violence targeting Israel or attempting to effectively govern the territory it took over by force of arms. For a short period of time after 2007, Hamas found itself forced by circumstance to suspend the tempo of resistance operations, for which it is named and by which it defines itself. For some, the cessation of violence, however temporary, was a sign of moderation within Hamas. Others expected Hamas to be co-opted by the day-to-day responsibilities of governance. However, Hamas’ actions, including its continued radicalization and weapons smuggling into Gaza, better denoted the movement’s true intentions and long-term trajectory. To be sure, Hamas is not a monolithic movement. But the one constant among its various currents is its self-identification as a resistance movement committed to Israel’s destruction and the creation in its place of an Islamist state in all of what it considers historic Palestine.

Looking back at the Hamas governance project in Gaza, it is clear the group remained committed to engaging in terrorist activity, and indeed it prioritized militancy over other activities at the expense of the Gaza Strip’s civilian population. Never co-opted, Hamas invested in efforts to inculcate its ideal of violent resistance against Israel throughout its time governing Gaza, and played a long game lulling Israeli and Western leaders into thinking it could be deterred with periodic nods to moderation. Meanwhile, it built tunnels and weapons production facilities, trained operatives, and prepared for the day it could finally act on its commitment to destroying Israel. As Hamas politburo member Khalil al-Hayya noted in the wake of the October 7 attack, “Hamas’s goal is not to run Gaza and to bring it water and electricity and such. Hamas, the Qassam and the resistance woke the world up from its deep sleep and showed that this issue must remain on the table.”107 Al-Hayya aptly summed up the relative weight Hamas gives to addressing the needs of Palestinians and fighting Israel. Referring to the October 7 attack, he explained: “This battle was not because we wanted fuel or laborers. It did not seek to improve the situation in Gaza. This battle is to completely overthrow the situation.”

Hamas’ attack was designed to elicit a “disproportionate” response from Israel. While several Israeli leaders have said the stated war objectives is the destruction Hamas, such an operation cannot be done by military force alone. Rather, what the war appears to be about is ending Hamas’ governance project in Gaza. What comes next for the group is largely dependent on how the war goes. Most of Hamas’ leadership remains, Israelis are still being held hostage in Gaza, and the scale of Israel’s response could serve to radicalize a new generation. As Hamas leader Haniyeh said in the days after Israel began its retaliatory attacks on Gaza that have resulted in thousands of deaths, “[w]e are the ones who need this blood, so it awakens within us the revolutionary spirit, so it awakens within us resolve, so it awakens within us the spirit of challenge, and [pushes us] to move forward.”108 Questions remain about what is next for Hamas. While true supporters of Hamas will see the October 7 attacks as a victory, many in Gaza will see the attacks as a betrayal of Hamas’ governance promise. CTC

Dr. Devorah Margolin is the Blumenstein-Rosenbloom Fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy and an Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University. Her research primarily focuses on terrorism governance, terrorism financing, the role of propaganda and strategic communications, countering/preventing violent extremism, and the role of women and gender in violent extremism. Dr. Margolin is the co-editor of Jihadist Terror: New Threats, New Responses (I.B. Tauris, 2019). X: @DevorahMargolin

Dr. Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler fellow and director of the Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Levitt teaches at the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and has served both as a counterterrorism analyst with the FBI and as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis at the U.S. Treasury Department. He is the author of Hamas: Politics, Charity, and Terrorism in the Service of Jihad (Yale, 2006), and has written for CTC Sentinel since 2008. X: @Levitt_Matt

© 2023 Devorah Margolin, Matthew Levitt

Substantive Notes

[a] Over 35 years, Hamas had never undertaken an operation of such scale, and it had not explicitly targeted vulnerable groups like children or the elderly. While the group has struck civilians over the years, before October 7 those attacks mainly targeted adults, whom the group sees as legitimate targets due to Israeli military draft laws. To Hamas, all Israeli adults are military targets. Hamas has also indiscriminately targeted civilians through rocket attacks or suicide bombings. The taking of children and elderly hostages into Gaza is a first for the group, which before October 7 had only taken male hostages over the age of 18.

[b] Regardless of Hamas’ framing, the number killed on October 7 is similar to the number who died when al-Qa`ida crashed United Airlines Flight 175 into the World Trade Center’s south tower two decades ago: 1,385 of the nearly 3,000 deaths caused on 9/11, according to the Global Terrorism Database. See “Incident Summary,” GTD ID 200109110005, Global Terrorism Database; “Israel revises Hamas attack death toll to ‘around 1200,’” Reuters, November 10, 2023.

[c] The Muslim Brotherhood in Palestine was active starting in the 1960s and 1970s. See Shaul Mishal and Avraham Sela, The Palestinian Hamas: Vision, Violence, and Coexistence (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006); Jerrold Post, The Mind of the Terrorist: The Psychology of Terrorism from the IRA to Al-Qaeda (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

[d] Article 8 of the group’s charter, reflects the centrality of violent jihad—religiously sanctioned resistance against perceived enemies of Islam—to its objectives: “Allah is its target, the Prophet is its model, the Koran its constitution: Jihad is its path and death for the sake of Allah is the loftiest of its wishes.” Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement,” August 18, 1988. This was also found in early leaflets produced by the group published in June 1988: “For our war is a holy war for the sake of Allah unto victory or death.” Reproduced in Mishal and Sela, p. 51.

[e] Hamas’ language in Article 12 is seemingly a nod toward Abdallah Azzam’s notorious fatwa on the individual duty of jihad. Ideologue Azzam, a Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood member, inspired the likes of other terrorist groups such as al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State, as both organizations have cited nearly indistinguishable language in their justifications for violence. See Devorah Margolin, “Hamas at 35,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 21, 2022.

[f] While Hamas terror attacks may not explicitly target Westerners, the group’s terrorist attacks do not discriminate among their victims. As such, innocent civilians from around the world have been killed in Hamas attacks, including civilians from the United States, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, Romania, China, the Philippines, and Sweden, among other nationalities. Hamas has purposely targeted many busy civilian venues, including buses, bus and light rail stops, discotheques, restaurants, markets, universities, and even a hotel hosting a Passover Seder. See “Chinese Worker, Palestinian killed in Gaza Settlement Attack,” Agence France-Presse, June 7, 2005; “The Family of Nations Under Fire: Victims of Palestinian Violence From 18 Countries,” Beyond Images, March 2, 2004; “Palestinian Suicide Bombings 1994-2004: Don’t Let the World Forget …,” Beyond Images, September 2, 2004.

[g] For example, in two identical articles on Hamas’ Al-Qassam website, it is stated that: “More important than the role in armed resistance is women’s role in spreading Islamic teaching and principles inside the Palestinian society. Women are very active in teaching the Holy Quran and Islamic conduct in various life issues. Women as mothers who carry the burden of caring for children have been able to educate future mothers on how to lead their lives, and how to raise their children.” “Women’s Participation in the Palestinian Struggle for Freedom,” Al-Qassam website, December 3, 2006; “International Woman’s Day Is Different in Palestine,” Al-Qassam website, March 7, 2007; Gina Vale, Devorah Margolin, and Farkhondeh Akbari, “Repeating the Past or Following Precedent? Contextualising the Taliban 2.0’s Governance of Women,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), January 12, 2023.

[h] While Hamas highlighted women’s roles as wives, mothers, and supporters of the movement throughout the 1980s and 1990s, in the early 2000s, a shift occurred. In 2001, Ahlam Mazen Al-Tamimi was arrested for her support role in bombing a Sbarro restaurant in Jerusalem, and Hamas’ Al-Qassam website praised Al-Tamimi and called her “the first female member in Al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas.” “Prisoners: Ahlam Mazen At-Tamimi,” Al-Qassam website, 2006 (online at time of collection in 2016, undated). Then, in 2004, Reem Riyashi became Hamas’ first female suicide bomber. While Hamas praised Riyashi, the group also continued to underscore its use of women as suicide bombers only under conditions of strategic necessity. See Sami Abu Zuhri and Faraj Shalhoub, “Debate, al-Majd TV, Clip No. 117,” MEMRI, June 13, 2004.

[i] Hamas has been variously designated as a terrorist group by countries around the world. Both the political and military wings of Hamas are designated as terrorist entities by Canada, the European Union, Israel, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In 1995, the U.S. government designated Hamas a Specially Designated Terrorist (“SDT”). In 1997, the U.S. government designated Hamas a Foreign Terrorist Organization (“FTO”), a designation that has been renewed every two years. In 2001, the U.S. government designated Hamas a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (“SDGT”), a designation Hamas has retained through the present. Additionally, several individuals and front organizations associated with Hamas have been designated SDTs and SDGTs. See Executive Order 12947, “Prohibiting Transactions with Terrorists Who Threaten to Disrupt the Middle East Peace Process,” Part IX, January 25, 1995; U.S. State Department Bureau of Counterterrorism, “Designation of Foreign Terrorist Organizations,” October 8, 1997; Executive Order 13224 – Blocking Property And Prohibiting Transactions With Persons Who Commit, Threaten To Commit, Or Support Terrorism; “US Designates Five Charities Funding Hamas and Six Senior Hamas Leaders as Terrorists,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Treasury Department, August 22, 2003. In contrast, only the military wing of Hamas—Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, or more simply, Al-Qassam—has been designated by others, including Australia and New Zealand. In the Middle East, policies toward the group are mixed. Saudi Arabia’s designation of the Muslim Brotherhood led to cool relations with Hamas, while Egypt overturned its previous designation of Hamas in 2015. The governments of Jordan, Qatar, and Turkey have not overtly supported Hamas and its agenda, but they have met with its leaders and played bystander or intermediary roles. Elsewhere, the group’s complex relationship with Syria has just started to thaw, while Iran has financially and militarily supported Hamas for decades. See “Egypt court overturns Hamas terror blacklisting,” BBC, June 6, 2015; Ido Levy, “How Iran Fuels Hamas Terrorism,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, June 1, 2021.

[j] Hamas has used its governance to run an extensive social service network in Gaza. These include food-based charities (feeding women and children), operating weddings and financial incentives to newlyweds, and supporting widows and families of “martyrs” or those who are killed or imprisoned while supporting Hamas’ cause. See “Zionists Resort to ‘black Propaganda’ to Counter Hamas,” Al-Qassam website, September 5, 2009; “Because of the Siege, Children Suffer in Gaza,” Al-Qassam website, February 23, 2008; “We Will Never Recognize the Occupation,” Al-Qassam website, July 17, 2009.

[k] In 2015, the group tweeted, “Hamas respects human rights; that is part of our ideology and dogma #AskHamas.” See Tweet 2720, March 15, 2015, cited in Devorah Margolin, “#Hamas: A Thematic Exploration of Hamas’s English-Language Twitter,” Terrorism and Political Violence 34:6 (2020).

Citations

[1] Anthony Blinken, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu After Their Meeting,” U.S. Department of State, October 12, 2023.

[2] Devorah Margolin, “A Major Pivot in Hamas Strategy,” War on the Rocks, October 16, 2023.

[3] Cassandra Vinograd and Isabel Kershner, “Israel’s Attackers Took About 240 Hostages. Here’s What to Know About Them,” New York Times, November 2, 2023.

[4] Wael Abdelal, Hamas and the Media: Politics and Strategy (Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2016).

[5] See Ahmad Dep., Exhibit 11, included in Boim at al v. Quranic Literacy Institute et al, cited in Matthew Levitt, Hamas: Politics, Charity and Terrorism in the Service of Jihad (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 150.

[6] For example, see Article 2: “The Islamic Resistance Movement is one of the wings of Moslem Brotherhood in Palestine.” Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement,” August 18, 1988.

[7] For example, see Articles 1, 5, 6, 8, and 11. Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement.”

[8] For example, see Preamble, Articles 6, 7, 8, 11 and 13. Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement.” This was also found in a Hamas leaflet published on August 18, 1988: “Every negotiation with the enemy is a regression from the [Palestinian] case, concessions of a principle, and recognition of the usurping murderers’ false claim to a land in which they were not born.” Reproduced in Mishal and Sela, p. 51.

[9] For example, see Preamble, Articles 7, 17, 22, 28, and 32. Hamas, “The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement.” This was also found in early leaflets produced by the group published in January 1988, “[The Jews] are “brothers of the apes, assassins of the prophets, bloodsuckers, warmongers … Only Islam can break the Jews and destroy their dream.” Reproduced in Mishal and Sela, p. 52.

[10] Pamala L. Griset and Sue Mahan, Terrorism in Perspective (London: Sage Publications, 2003).

[11] Gina Vale, Devorah Margolin, and Farkhondeh Akbari, “Repeating the Past or Following Precedent? Contextualising the Taliban 2.0’s Governance of Women,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), January 12, 2023.

[12] “Yassin Sees Israel ‘Eliminated’ Within 25 Years,” Reuters, May 27, 1998.

[13] Levitt, Hamas.

[14] “Subject: Hamas/Bassem Musa’s Letter,” in Stanley Boim et al. v. Quranic Literacy Institute et al. Currency unstated, likely Israeli Shekel or U.S. dollar, cited in Levitt, Hamas, p. 68.

[15] William A. Orme Jr., “Jordan Frees Four Jailed Hamas Leaders and Expels Them,” New York Times, November 22, 1999; “Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal returns for Jordan visit,” BBC, January 29, 2012.

[16] Fares Akram, “Hamas Leader Abandons Longtime Base in Damascus,” New York Times, January 27, 2012; Omar Shaaban, “Hamas and Morsi: Not So Easy Between Brothers,” Carnegie Middle East Center, October 1, 2012.

[17] “Treasury Targets Covert Hamas Investment Network and Finance Official,” U.S. Department of Treasury, May 24, 2022; Hadeel al Sayegh, John O’Donnell, and Elizabeth Howcroft, “Who funds Hamas? A global network of crypto, cash, and charities,” Reuters, October 16, 2023.

[18] Fares Akram and Isabel Debre, “As Young Gazans Die at Sea, Anger Rises Over Leaders’ Travel,” Associated Press, January 6, 2023.

[19] Michelle Pace, “The Social, Economic Political and Geo-Strategic Situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territories,” Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union, European Parliament, 2012.

[20] Efraim Benmelech and Claude Berrebi, “Human Capital and the Productivity of Suicide Bombers,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21:3 (2007): p. 227.

[21] Global Terrorism Database, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, University of Maryland, 2020.

[22] William Booth, “Israel’s prisoner swaps have been far more lopsided than Obama’s Bergdahl deal,” Washington Post, June 5, 2014.

[23] “Hamas Kidnappings: A Constant Threat in Israel,” Israel Defense Forces, June 16, 2014.

[24] Ethan Bronner, “Hamas Shifts From Rockets to Culture War,” New York Times, July 23, 2009.

[25] Islah Jad, “Islamist Women of Hamas: between feminism and nationalism,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 12:2 (2011).

[26] Ibid.

[27] Levitt, Hamas.

[28] Devorah Margolin, “#Hamas: A Thematic Exploration of Hamas’s English-Language Twitter,” Terrorism and Political Violence 34:6 (2020); Sagi Polka, “Hamas as a Wasati (Literally: Centrist) Movement: Pragmatism within the Boundaries of the Sharia,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42:7 (2019): pp. 683-713.

[29] Joshua L Gleis and Benedetta Berti, Hezbollah and Hamas: A Comparative Study (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

[30] Bjorn Brenner, Gaza Under Hamas: From Islamic Democracy to Islamist Governance (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016).

[31] David Rose, “The Gaza Bombshell,” Vanity Fair, April 2008.

[32] “National Reconciliation Document,” Palestine-Israel Journal 13:2 (2006).

[33] General Shlomo Brom, “A Hamas Government: Isolate or Engage?” United States Institute of Peace, March 10, 2006.

[34] Reproduced in Cole Bunzel, “Gaza and Global Jihad,” Foreign Affairs, November 2, 2023.

[35] Reproduced in Michael Herzog, “Can Hamas be Tamed,” Foreign Affairs, March 1, 2006.

[36] Rose, “The Gaza Bombshell.”

[37] Mohammed Assadi, “Factional battles kill 616 Palestinians since 2006,” Reuters, June 6, 2007.

[38] Palestine Center for Human Rights, “Black pages in the absence of justice – Report on bloody fighting in the Gaza Strip from 07 to 14 Jun 2007,” Relief Web, October 9, 2007.

[39] “Fatah Man Thrown Off Roof,” Agence France-Presse, March 17, 2009; “Hamas seizes Fatah headquarters in Gaza,” Associated Press via NBC News, June 11, 2017.

[40] See “2015 Investment Climate Statement – West Bank and Gaza,” U.S. Department of State Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs, May 2015.

[41] Colin P. Clarke, Terrorism, Inc.: The Financing of Terrorism, Insurgency, and Irregular Warfare (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Security International, 2015), pp. 102-111.; Joshua L. Gleis and Benedetta Berti, Hezbollah and Hamas: A Comparative Study (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), p. 156; “Terrorist Group Profiler,” Canadian Secret Intelligence Service (CSIS), June 2002, author’s personal files. See also Stewart Bell, “Hamas May Have Chemical Weapons: CSIS Report Says Terror Group May be Experimenting,” National Post (Canada), December 10, 2003.

[42] Ahmad Abu Amer, “Will Iran deal mean more money for Hamas?” Al Monitor, January 27, 2016.

[43] Clarke, pp. 102-111; Zeev Schiff, “Iran and Hezbollah Trying to Undermine Renewed Peace Efforts,” Haaretz, May 12, 2004.

[44] Matthew Levitt, “Combating the Networks of Illicit Finance and Terrorism,” Testimony submitted to the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, 118th Congress, October 26, 2023.

[45] “State Sponsors of Terrorism” in “Country Reports on Terrorism 2010,” United States Department of State, August 18, 2011; Fares Akram, “Hamas Leader Abandons Longtime Base in Damascus,” New York Times, January 27, 2012.

[46] Hadeel Al Sayegh, John O’Donnell, and Elizabeth Howcroft, “Who funds Hamas? A global network of crypto, cash and charities,” Reuters, October 16, 2023.

[47] Evan Dyer, “How tiny Qatar hosts the leaders of Hamas without consequences,” CBC News, October 18, 2023.

[48] Humeyra Pamuk, “Qatar open to reconsidering Hamas presence in Qatar, US official says,” Reuters, October 27, 2023.

[49] Levitt, “Combating the Networks of Illicit Finance and Terrorism,” p. 3.

[50] Ibid., p. 2.

[51] Levitt, Hamas, p. 56.

[52] “Hamas Summer Games, Tomorrow Pioneers,” Al-Qassam website, June 19, 2010.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Fares Akram, “Hamas Adds Restrictions on Schools and Israelis,” New York Times, April 1, 2013.

[55] Ibid.; “Hamas law promotes gender segregation in Gaza schools,” Reuters, April 1, 2013.

[56] “Hamas and Women: Clearing Misconceptions,” Hamas website, January 12, 2011, accessed July 14, 2018.

[57] Dina Kraft, “Hamas launches ‘virtue campaign’ in Gaza,” Telegraph, July 28, 2009.

[58] “Hamas targets women’s underwear in modesty drive,” Reuters, July 28, 2010.

[59] Emily Harris, “Hamas: Gaza Women Learning To Drive Must Have A Chaperone,” NPR, June 1, 2016.

[60] “Women need male guardian to travel, says Hamas court in Gaza Strip,” Guardian, February 15, 2021.

[61] “Gaza: Hamas produces first feature film,” Jerusalem Post, July 18, 2009.

[62] Yaakov Lappin, “Disney’s daughter slams Hamas’ Mickey,” Ynet, May 9, 2007.

[63] “Hamas TV Kills Off Mickey Mouse Double,” Associated Press, June 30, 2007.

[64] Simon Mcrgegor-Wood, “Bye, Bye Mickey! Hamas TV Abuzz Over Nahoul the Bee,” ABC News, July 17, 2007.

[65] Josiah Daniel Ryan, “Hamas Children’s TV Program Again Calls for ‘Slaughter of Jews,’” Jerusalem Post, October 4, 2009.

[66] “State Department Terrorist Designation of Senior Hamas Official – Fathi Hammad,” U.S. Department of State, September 16, 2016.

[67] Rory McCarthy, “Hamas patrols beaches in Gaza to enforce conservative dress code,” Guardian, October 18, 2009; “German Mediator Is Serious,” Al-Qassam website, September 3, 2009, accessed July 19, 2018.

[68] “Women need male guardian to travel, says Hamas court in Gaza Strip.”

[69] Nidal al-Mughrabi, “Gaza law barring women from travel without male consent to be revised, judge says,” Reuters, February 16, 2021; Fares Akram, “Hamas ‘guardian’ law keeps Gaza woman from studying abroad,” Associated Press, November 5, 2021.

[70] Oliver Holmes, “Hamas violently suppresses Gaza economic protests,” Guardian, March 21, 2019; Gianluca Pacchiani, “Protests against Hamas reemerge in the streets of Gaza, but will they persist?” Times of Israel, August 8, 2023.

[71] Matthew Levitt and Yoram Cohen, “Deterred but Determined: Salafi-Jihadi Groups in the Palestinian Arena,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, January 11, 2010.

[72] Levitt, “Combating the Networks of Illicit Finance and Terrorism;” Daphné Richemond-Barak, Underground Warfare (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2017).

[73] Matthew Levitt and Aviva Weinstein, “How Hamas’ Military Wing Threatens Reconciliation with Fatah,” Foreign Affairs, November 29, 2017.

[74] See, for example, “Incendiary balloons from Gaza spark two fires in south,” Times of Israel, September 30, 2018.

[75] See, for example, Andrew Carey, Hadas Gold, Kareem Khadder, and Abeer Salman, “Israel launches airstrikes after rockets fired from Gaza in day of escalation,” CNN, May 11, 2021.

[76] See, for example, Emanuel Fabian, “Palestinians detonate large explosive on Gaza border in latest rioting,” Times of Israel, September 6, 2023.

[77] Richemond-Barak.

[78] Marco Hernandez and Josh Holder, “The Tunnels of Gaza,” New York Times, November 10, 2023.

[79] “Israel Protests to UN after Hamas Tunnel Found under UNRWA Schools in Gaza,” Times of Israel, June 10, 2017.

[80] “Palestinian police arrest West Bank plotters,” Reuters, July 4, 2009.

[81] Terrence McCoy, “After Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, Palestinian unity government on rocks,” Washington Post, September 10, 2014.

[82] “Senior PA official said to warn Hamas plotting coup against Abbas in West Bank,” Times of Israel, April 16, 2019.

[83] Judah Ari Gross, “Shin Bet chief: Hamas setting up in Lebanon with Iran’s support,” Times of Israel, September 10, 2017.

[84] “Rocket launch at Israel from Lebanon draws Israeli cross-border shelling,” Reuters, July 6, 2023.

[85] Emanuel Fabian, “Hamas claims responsibility for rocket fire from Lebanon,” Times of Israel, October 19, 2023.

[86] Isabel Kershner, “New Light on Hamas Role in Killings of Teenagers That Fueled Gaza War,” New York Times, September 4, 2014.

[87] “Hamas Admits to Kidnapping and Killing Israeli Teens,” NPR, August 22, 2014.

[88] Matthew Levitt, “Hamas’ Not-So-Secret Weapon,” Foreign Affairs, July 9, 2014.

[89] Jonathan Lis, “Hamas is Plotting Attacks on Israel Every Day, Shin Bet Chief Warns,” Haaretz, March 20, 2017.

[90] Judah Ari Gross, “Shin Bet nabs Hamas terror cell ‘plotting attacks in Israel,’” Times of Israel, February 6, 2017.

[91] Anna Ahronheim, “Israel foils terror cell’s kidnapping, attack plot to free Hamas prisoner,” Jerusalem Post, December 8, 2016.

[92] Matthew Levitt, “Reality Contradicts New Hamas Spin,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 7, 2009.

[93] “Transcript, Interview with Khaled Meshal of Hamas,” New York Times, May 5, 2009.

[94] Kifah Zboun, “Haniyeh: We Support Establishment of Palestinian State on Basis of 1967 Borders,” Asharq al-Awsat, November 2, 2017.

[95] Ali Waked, “Mashaal: Abbas leading us to doom,” Ynet, November 10, 2009.

[96] Howard Shneider, “Defiant Abbas Reiterates Conditions Before Talks,” Washington Post, October 12, 2009.

[97] Becky Sullivan, “Gaza Wants to Rebuild, but Ensuring Funds Don’t Go to Hamas is Slowing the Process,” NPR, June 23, 2021.

[98] Katherine Bauer and Matthew Levitt, “Hamas Fields a Militant Electoral List: Implications for U.S.-Palestinian Ties,” PolicyWatch 3473, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, April 21, 2021.

[99] Ali Hashem and Adam Lucente, “Meet Hamas’ Key Leaders, Many on Israel’s Target List in Gaza,” Al-Monitor, October 18, 2023; Adnan Abu Amer, “How Hamas Prisoners Elect Leaders Behind Bars,” Al-Monitor, February 13, 2017.

[100] See Bauer and Levitt.

[101] Adnan Abu Amer, “Drawing on past lessons, Hamas submits inclusive electoral list,” Al-Monitor, April 1, 2021.

[102] David Pollock, “Netanyahu and Hamas Set to Coexist Uneasily Again,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, November 29, 2022; Wafaa Shurafa and Fares Akram, “Mass funeral in Gaza draws tears, rare criticism of Hamas,” Associated Press, December 18, 2022.

[103] Pollock; Shurafa and Akram.

[104] “Hamas elects first woman to political bureau,” Times of Israel, March 14, 2021.

[105] Aaron Boxerman, “Hamas wins landslide victory in student elections at flagship Birzeit University,” Times of Israel, May 18, 2022.

[106] Devorah Margolin, “Hamas at 35,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 21, 2022.

[107] Ben Hubbard and Maria Abi-Habib, “Behind Hamas’s Bloody Gambit to Create a ‘Permanent’ State of War,” New York Times, November 9, 2023.

[108] “Hamas Leader Ismail Haniyeh: We Need The Blood Of Women, Children, And The Elderly Of Gaza – So It Awakens Our Revolutionary Spirit,” Special Dispatch No. 10911, MEMRI, October 27, 2023.

Skip to content

Skip to content