Abstract: The Congolese branch of the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province (ISCAP-DRC), locally known as the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), is a rising threat to the region. Not only did it inflict more fatalities than ever before in 2021, but last year was also the most operationally transformative for the group since it declared allegiance to the Islamic State around 2017. Thanks to its increased integration into the Islamic State, ISCAP-DRC’s modi operandi evolved in seven key areas—from a surge in Islamic State-supported propaganda to its first use of suicide bombings—that have contributed to the group’s escalating terror campaign in Congo and abroad. Together, these changes have enabled the ADF—already the deadliest group in eastern Congo—to become a bolder and more lethal terrorist organization, poised to further export its operations to the region.

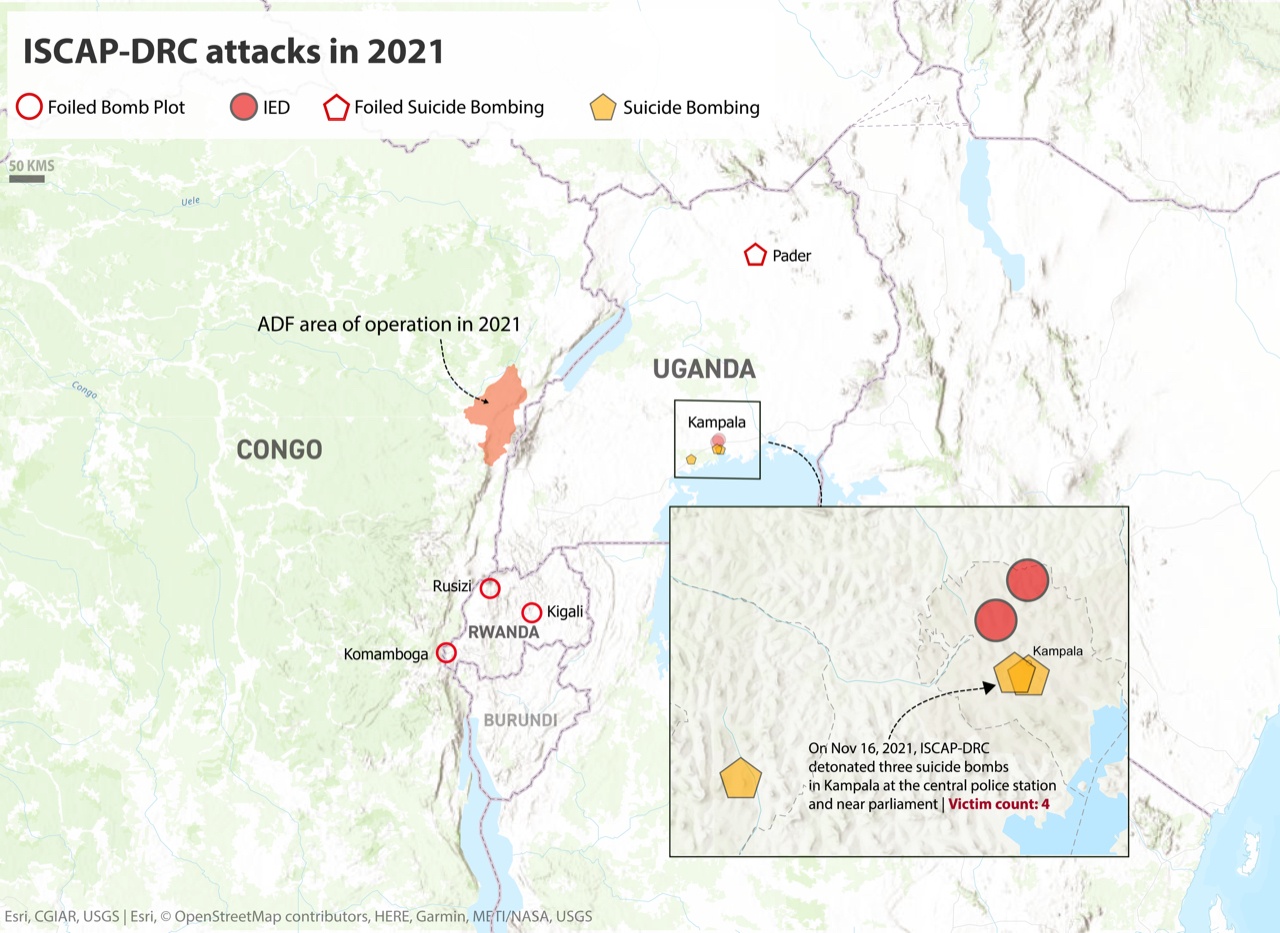

On November 16, 2021, three suicide bombers detonated themselves in two locations in downtown Kampala, Uganda, killing at least four civilians and wounding 30 others.1 While resulting in fewer casualties than the suicide bombings Kampala witnessed in the summer of 2010,a the November 2021 bombings had significant implications for regional security. First, the attacks were perpetrated by the Congolese branch of the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province (ISCAP-DRC), more commonly known by its local name, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF).b Second, the blasts were the first suicide bombings claimed by the Islamic State on Ugandan soil and outside of the ADF’s primary area of operation within the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, suggesting a desire by the Islamic State to project its power to new territories. And third, the bombings came on the heels of a coordinated—but ultimately unsuccessful—attempt by the ADF to bomb multiple civilian targets in Rwanda2 and amid credible reports of the ADF’s efforts to establish cells in surrounding countries.3

This article seeks to unpack the ADF’s transformation within the wider context of the overall operations of ISCAP-DRC last year. Specifically, this article argues that 2021 was the group’s most operationally transformative year since joining the Islamic State around 2017, with the ADF both pushing and being pulled toward adopting the norms and practices of its adopted parent organization. As will be outlined below, in addition to newly implementing the tactic of suicide bombings, the group also began exporting its violence beyond the borders of the DRC to Uganda and Rwanda, deepened its recruitment of foreign fighters, began clashing with other armed groups in the Congo on a more regular basis, began publicly emphasizing proselytization within the DRC, began filming and releasing beheading videos, expanded its use and capabilities with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and, by more deeply integrating its media efforts with the Islamic State, greatly expanded its propaganda production. Taken together, these changes, all explained and enabled to varying degrees by the group’s deepening linkages to the Islamic State’s transnational network, constitute a significant transformation in the group’s modi operandi.

Based on primary source fieldwork and research conducted by the authors across the DRC, Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, and Somaliland between November 2020 and April 2022 in addition to open-source research in French, English, Arabic, and Swahili, this article argues these operational transformations were the direct result of the ADF’s integration into the Islamic State. With the support of the Islamic State, particularly in terms of financing and propaganda, ISCAP-DRC has fully transitioned from a group traditionally only focused on Uganda and eastern Congo, to a wider, more regional terrorist threat. And if its operations in 2021 are any indication, the group’s propensity for exporting its violence across East and Central Africa will continue to deepen and expand if left unchecked.

Starting with a brief background of the ADF’s history and transition into a so-called province of the Islamic State, this article then provides a chronology of key developments in 2021, including the group’s operations across the DRC and the wider region and the joint military campaign launched against it by the DRC and Uganda in late 2021. It then examines significant changes across seven dimensions of the group’s operations in 2021, with these shifts all explained to varying degrees by the group’s deepening integration into the Islamic State’s transnational network.

How ADF Became ISCAP-DRC

Before outlining the ADF’s operational transformation throughout 2021, it is first important to briefly touch on its history. The Congolese branch of the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province started as the Allied Democratic Forces in Uganda in the mid-1990s, a radical, violent splinter group formed during intraclerical disputes over who would wield leadership of the state-recognized authority governing Uganda’s Muslim community. Quickly routed by Ugandan security forces and forced across the border into Congo, the group found support from the former Zairian government under Mobutu Sese Seko, as well as from Sudan, both of which sought a proxy with which to counter Uganda. The group carried out a bloody cross-border insurgency into Uganda during and after Congo’s cataclysmic wars between 1996 and 2003, until battlefield losses and geopolitical shifts in the early 2000s forced the group into a survival posture as one of the many foreign and Congolese militias that persisted in Congo’s east. While the group increasingly integrated with local communities and pursued economic activities, military pressure by Congolese security forces led the ADF to retaliate by perpetrating a series of bloody attacks against Congolese civilians in 2013. These massacres in turn led to a much more devastating offensive by the Congolese army in 2014 and the flight of the group’s longstanding leader, Jamil Mukulu, from Congo.4

While long espousing an Islamist outlook, the ADF had largely limited its goals to overthrowing the government of Uganda’s longstanding ruler Yoweri Museveni, but in 2016, that began to change. The year before, the ADF’s founder and its core ideological driver, Jamil Mukulu, was arrested in Tanzania. His successor, Musa Baluku, more radical and embracing a more global jihadi outlook, then set the group on its current trajectory. In 2016, the ADF began releasing rudimentary propaganda videos—its first ever—while also briefly publicly rebranding itself as Madina at-Tauheed wa-Mujahideen (MTM).c It is unknown when exactly the ADF, led by Musa Baluku, swore bay`a (allegiance) to the Islamic State and its then-leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, but reportedly by late 2017, the group was receiving its first iteration of financing from the Islamic State through Kenyan financier Waleed Ahmed Zein.5 Around the same time, the ADF released a video, widely shared on Islamic State-supporter media, featuring an Arabic-speaking Tanzanian known as ‘Jundi’ or ‘Abuwakas,’ urging people to join the Islamic State in Congo. By early 2019, the Islamic State officially recognized the ADF as part of its global apparatus by designating it one-half of its Central Africa Province, with the other half being the Mozambican jihadi group known locally as “al-Shabaab” (no relation to the Somali group of the same name).6 d And while the central leadership of the Islamic State’s Congolese branch remains predominantly Ugandan, the group has taken on more regional foreign recruits in recent years, including other nationalities represented in its upper echelons.7

Key Developments in 2021

While the Islamic State has openly operated inside Congo since 2019, last year saw some significant operational trends that bear exploring. Relying on data from the Kivu Security Tracker (KST)e of all known or suspected ADF attacks since 2017, the authors identified several key trends in 2021 when compared to previous years.

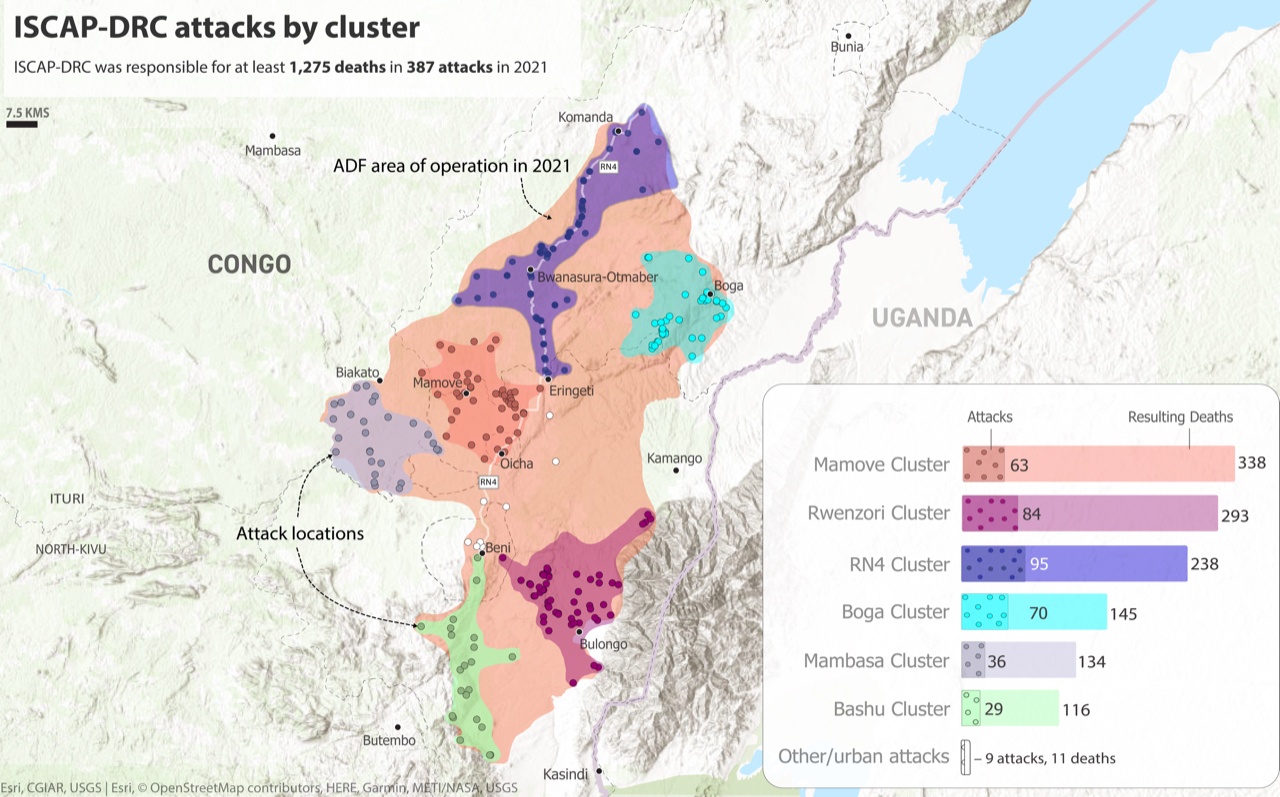

Firstly, 2021 was the deadliest year on record for ISCAP-DRC. The group was responsible for at least 1,275 civilian deaths in DRC in 2021—almost three times the death toll of 2019 and more than a 50% increase over 2020’s 782 killed.

Secondly, much of this violence was driven by a rapid rise in massacres of 10 people or more: ISCAP-DRC killed 378 people in 22 such massacres in 2020, while 2021 witnessed almost double the number of such massacres and deaths with 40 such massacres claiming 715 lives.8 The highest concentration of these massacres was in the area around the town of Mamove, which spans the North Kivu-Ituri border to the west of Route Nationale 4 (RN4), where 12 ISCAP-DRC massacres of 10 people or more killed at least 220 people.f

And thirdly, both wings of ISCAP in DRC and Mozambique faced international interventions in 2021, though it remains unclear how effective the interventions will be at curbing ISCAP’s violence in either country.g

This section seeks to place the highlights of ISCAP-DRC’s broader operations in 2021 into context in the local, regional, and international theaters. Doing so creates a better backdrop in which to extrapolate the noticeable trends and evolutions with respect to the group that will be discussed throughout this article.

ADF Military Operations in 2021

The year 2021 started with significant bloodshed inflicted by ISCAP-DRC (also known as the ADF) with the continuation of its massacres in Rwenzori, an area southeast of Congo’s Beni town, that had escalated throughout 2020. Following the group’s expulsion from Loselose on January 1, 2021—the only populated town the ADF is confirmed to have ever occupied—ADF fighters retaliated, killing 22 people in nearby Mwenda.9 At the same time, January 2021 provided the first hint that ADF forces were moving into the southern part of Ituri Province in northeast Congo. Although the group had committed a handful of smaller attacks in the area over the course of 2020, the January 14, 2021, massacre of 46 people near Ambebi, across the provincial border from Mamove, demonstrated that the ADF was establishing a much larger and more aggressive presence in southern Ituri than had previously been known.10 Over the course of 2021, the ADF would go on to open a significant second front in Ituri in its campaign against the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) and the people of eastern Congo.

The Rwenzori region remained the group’s main focus in February 2021, accounting for 16 of 21 incidents, but by March 2021, the majority of the violence had shifted north, first to Mamove and then eventually to Ituri’s Irumu territory.11 Mamove suffered 11 incidents affecting 13 villages that March, with the ADF killing 77 people.12 Most of those deaths occurred in three days of coordinated attacks—March 19, 23, and 30—when the ADF hit multiple villages each day, killing 66 people total.13 That same month, the group was designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization by the U.S. State Department.14 h

A few weeks later in April 2021, as a response to the ADF’s growing violence, the Congolese government announced a “state of siege” in North Kivu and Ituri provinces. Under this authority, Kinshasa replaced civilian government officials with military appointees tasked with ending the massacres and bringing peace to the region.15 Both North Kivu and Ituri have remained in this state of siege ever since.

The ADF resurfaced powerfully but briefly in the Rwenzoris in May 2021, killing 60 people in 13 attacks, but by the end of that month, the ADF’s campaign for southern Ituri had begun in earnest. Twin attacks around the towns of Boga and Tchabi on May 31, 2021, powerfully demonstrated this shift, with ADF fighters killing 55 people and making international headlines.16

By June 2021, the ADF began to shift its focus to elsewhere in Ituri province’s Irumu territory, and more specifically, Route Nationale 4. RN4 is the main economic thoroughfare connecting North Kivu’s Eringeti to Ituri’s Komanda and on to the provincial capital of Bunia. The ADF’s campaign along RN4 was the group’s most sustained assault of the year. In total, ADF fighters attacked villages on or along the road 78 times—all but nine of which occurred between June and the end of the year—up to and past Komanda, the largest town in Irumu territory.17 Based on the data compiled by the authors from KST incidents, the casualties during most of these operations remained relatively low, with the RN4 cluster having the second-lowest average death toll per operation, but the sustained nature of the attacks forced FARDC to close the road in September to try to reestablish control.i When it reopened a week later, civilians were encouraged to use the road only as part of FARDC- and MONUSCO-protected convoys.18 The ADF launched at least three successful attacks against the convoys,19 demonstrating security forces’ inability to control the road. Moreover, this offensive represented the northernmost attacks ever perpetrated by the ADF inside Congo, further expanding the group’s main area of operation.

At the same time as the RN4 offensive, the ADF also perpetrated its first-ever suicide bombing, targeting civilians inside Beni city, DRC,20 and restarted its kinetic operations inside Uganda with an assassination attempt on a high-level Ugandan official21 and a foiled suicide bombing plot.22 All three dynamics will be discussed in more detail in a later section.

The next month, in July 2021, Rwanda intervened inside northern Mozambique to help that country combat the other wing of the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province.23 The combined Rwandan-Mozambican force succeeded in driving the Islamic State militants back from cities it took over, namely Palma district and Mocimboa da Praia, sparking widespread anger among Islamic State supporters and likely prompting the ADF’s subsequent efforts (discussed later in the article) to attack Rwanda in September 2021.

Even as the ADF was fighting for control of RN4 in the north, the group also began to expand farther south in Beni territory. While attacks and casualties in Rwenzori remained low through September 2021, the August 2021 joint FARDC-MONUSCOj campaign targeting ADF camps south of Rwenzori—an area known as Mwalika—pushed the group out of what was its traditional area of operations. Its fighters retaliated with attacks in Bashu, a region to the east of Butembo that had historically been spared the ADF’s violence. The sudden shift, with attacks occurring within nine kilometers of Beni territory’s largest city, Butembo, caused significant distress among the local population. Although Bashu suffered relatively few attacks overall—only 20 during 2021—each incursion was fairly deadly, with an average of five civilians killed per attack (the highest average of any ADF cluster in 2021).24 This number was driven in part by the ADF’s most significant massacre in the region, when the group attacked Kisunga village on November 11, 2021. Operating with impunity for almost four hours in the middle of the night, ADF fighters killed 38 and abducted 59 others as they burned buildings, a health center, and a motorcycle before escaping with their stolen goods.25

With operations continuing in Bashu, the ADF began to reassert itself around Rwenzori in October 2021. That month, the group mounted a series of attacks in the region that appeared aimed at harassing security forces to draw them up into a defensive posture around towns north of the Beni-Kasindi road, the main road between Beni town and Uganda.

These attacks continued into November 2021, even as the ADF maintained pressure from Bashu up to RN4 and over to Ituri’s Mambasa territory in the west and Boga in the east. With the ADF’s return to the Rwenzori region, the group was now operating simultaneously across an area significantly larger than when 2021 began: The group’s overall AO (area of operations) in 2020 accounted for roughly 3,523 square kilometers, whereas 2021 saw the group operating over more than 6,800 square kilometers, representing a 94% increase in territory.26 This expansion becomes even more stark when compared to the group’s overall AO for 2017, the first year of its integration into the Islamic State. Between 2020 and 2021 alone, the group’s AO nearly doubled (Figure 2).k

At the same time that the ADF was pushing back into Rwenzori in Congo, its operatives in Uganda began their bombing campaign. In October 2021, the group detonated three bombs, including a failed suicide attack outside of Kampala that killed only the bomber. These operations represented the successful resumption of the ADF’s offensive operations (discussed further in a later section) inside Uganda, which it had not conducted since at least 2017. As noted at the beginning of the article, in November 2021, the ADF conducted its largest international terrorist attack since the late 1990s when it perpetrated a triple suicide bombing attack against two targets in central Kampala.27 The bombings were quickly claimed by the Islamic State.28

Operation Shuja: DRC and Uganda’s Response

The ADF’s major escalations and evolution inside Congo and its foreign operations were not without serious consequences. After years of fruitless negotiations between Uganda and Congo, the two countries finally agreed in November 2021 to joint military operations targeting the group. A memorandum of understanding to cooperate on intelligence sharing and fighting terrorism was reportedly signed on November 5, 2021, but it was not until November 28—following the triple suicide bombing in Kampala—that Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi reportedly authorized the Ugandan armed forces (UPDF)’s entry into Congo.29

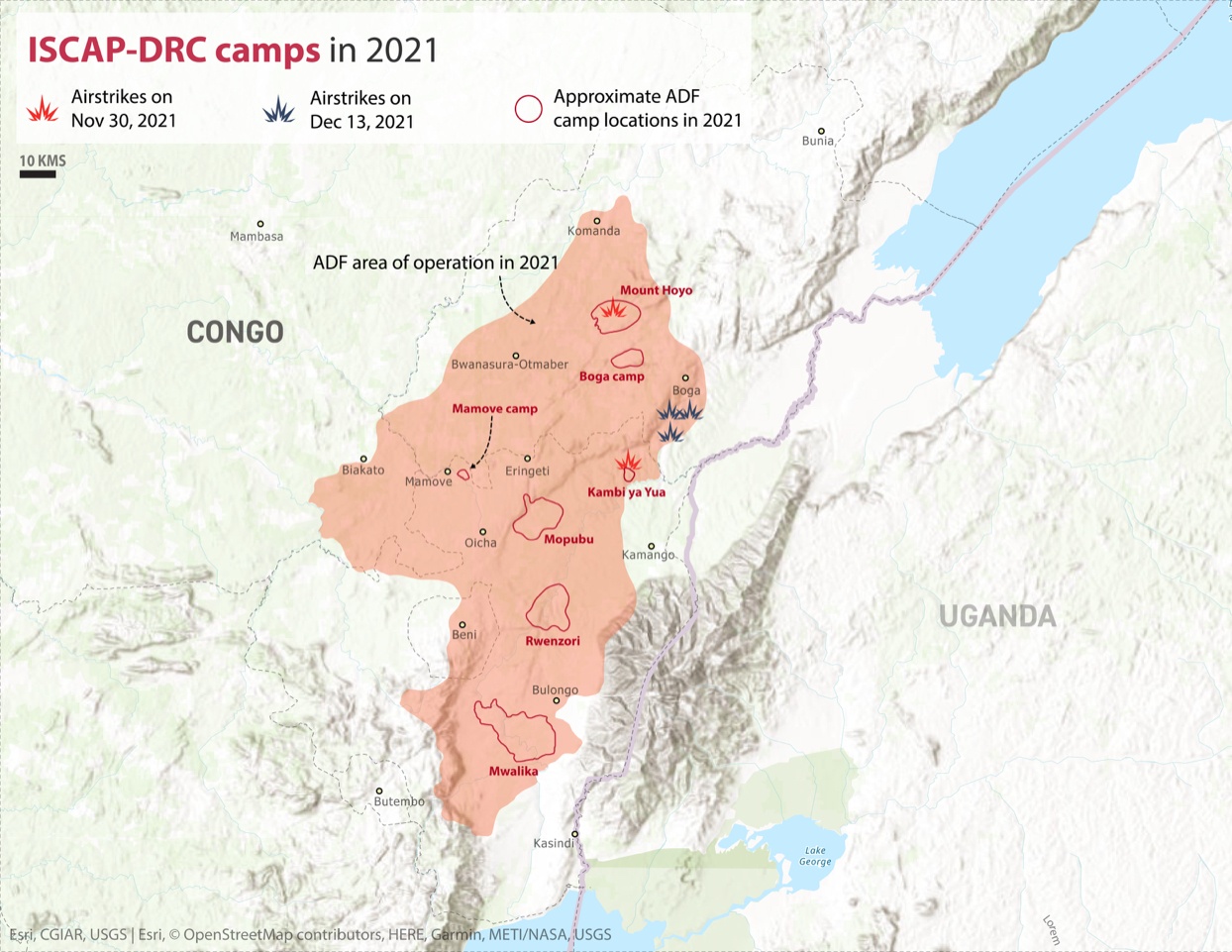

Cross-border operations began with Ugandan airstrikes on several ADF positions in Congo’s North Kivu and Ituri two days later on November 30, 2021. The strikes were quickly announced in a press release, subsequently reported as having struck targets near the locale of Kambi ya Yua in Virunga National Park near the Mbau-Kamango road in Beni territory of North Kivu and the villages of Belu I, Belu II, and Tondoli in the southern Irumu territory of Ituri.30

The same day as the strikes, approximately 100 UPDF soldiers crossed into Congo at the Nobili border crossing, with their numbers growing over the next few days as a forward operating base was established at Mukakati village, approximately eight kilometers northwest from the Congolese town of Kamango on the road to Mbau near Beni town.31 Early efforts of the joint operation, named “Operation Shuja,” or “courage” in Swahili, centered on rehabilitating the section of the Mbau-Kamango road between Kamango and the Semuliki river in order to facilitate troop and vehicle movements, an effort reported to have been completed by December 17, 2021.32

The FARDC and UPDF quickly claimed successes, including at one point suggesting that ADF leader Musa Baluku was killed or injured during the initial round of airstrikes.33 Baluku has since been confirmed alive, although the question remains as to whether he suffered any injury. The UPDF claimed on December 15, 2021, that they entered Kambi ya Yua camp—previously bombed on November 30—after a two-day trek from the FARDC base at the bridge across the Semuliki bridge.34 l Despite official claims of a major victory, counter-claims that only two ADF fighters were killed and photos of the camp itself suggested that the position may have been smaller than previously stated.35 However, sources report that ADF leader Musa Baluku was in Kambi ya Yua camp when it was hit, making it a strategically important target.36

UPDF air and artillery strikes continued in mid-December, 2021, with strikes on three villages south of Boga in Ituri reportedly killing 15 ADF fighters on December 13.37 In addition, the joint forces announced ground operations along RN4 in Ituri and search-and-clear operations along RN44 in southeastern Mambasa, a significant expansion of the areas targeted during the first weeks of Operation Shuja.38 These deployments, conducted by FARDC, were likely intended to respond to an escalation in ADF activity in both theaters during December, which itself was likely the result of ADF evacuations from previously held positions following air and artillery strikes. Previous offensives against the ADF have often resulted in significant escalations in ADF activity elsewhere in its area of operations, as the group has tried to both clear civilians from new areas it moves into and divert FARDC into a civilian protection posture.

While the number of ADF attacks and the overall death toll it inflicted in December 2021 was roughly on par for monthly ADF operations in 2021, the attacks were concentrated in ways that suggest a response to the joint operations. This is mainly evident from the amount of attacks concentrated inside Ituri’s Mambasa territory, which also suggests the ADF has moved westward as the joint UPDF-FARDC operations have pushed it out of its more traditional strongholds in North Kivu and the southern part of Irumu territory in Ituri. At least 15 ADF attacks were recorded inside Mambasa in December 2021, as opposed to just four such operations in November 2021. As the joint operations continue, it is possible the jihadi group will continue to mount more such attacks inside Mambasa territory. And as witnessed in prior offensives against the ADF,39 if the joint military forces of Congo and Uganda do not properly hold or maintain control over areas taken over, the ADF will likely return to its former strongholds in the near future.

Despite a brief reprieve in January, the first five months of 2022 has demonstrated that the joint operations have failed to completely prevent the ADF from perpetrating attacks in any of its 2021 geographic clusters, though changes in the intensity and frequency of attacks in each cluster remain to be seen. Additionally, 2022 has seen the ADF expand into areas it has not operated in the previous several years. With the UPDF establishing bases along the Mbau-Kamango road, not far from the Ugandan border, the ADF has begun targeting villages near the border in Watalinga, indicating that the area—part of the ADF’s infamous “triangle of death” from its 2014 operations—may once again become a target of sustained ADF operations.40

Operational Trends: How 2021 Was a Year of Transformation

Having provided a chronology of ISCAP-DRC/ADF operations in 2021, this article now examines how the group’s operations transformed in 2021, demonstrating both new capabilities and the intensification of other changes that began with the group’s evolution into an Islamic State affiliate. There were seven dimensions to these changes that, as will be outlined, the authors argue were enabled or explained by the group’s deepening integration into the Islamic State’s transnational network; enabled in the sense that the Islamic State’s central leadership had a direct impact on the change, or explained in the sense that the ADF itself adopted the norms and behaviors more typical of global Islamic State provinces. The first was the ADF’s increased reliance on the Islamic State for media distribution and the corresponding surge in propaganda production. The second was that the group began filming and releasing beheading videos. The third was that the ADF for the first time adopted suicide bombings as a tactic. The fourth was the new emphasis placed by the ADF on proselytization within the DRC. The fifth was the deepening of ideologically motivated foreign fighter recruitment. The sixth was that the ADF began exporting its violence beyond the borders of the DRC to Uganda and Rwanda. And the seventh was that the ADF began clashing with other armed groups in Congo on a more regular basis as it expanded its operating space. These seven dimensions are now discussed in turn.

1. A Surge in Propaganda Production and Increased Reliance on the Islamic State for Media Distribution

Over the course of 2021, the ADF’s external propaganda, released primarily through the Islamic State’s central media apparatus, greatly outpaced its media output of the previous two years combined. This includes both official claims of attacks and media, including photos and videos, released by the Islamic State. Conversely, the ADF’s internal media and/or media produced for more local consumption was relatively low compared to 2020. This dynamic of the group’s propaganda likely reflects greater integration into the Islamic State’s global apparatus. This increase in propaganda output is the most observable illustration of the ADF’s deepening relationship with the Islamic State, and it appears the ADF also follows clear Islamic State media diktats given its participation in coordinated media releases by Islamic State affiliates around the world.

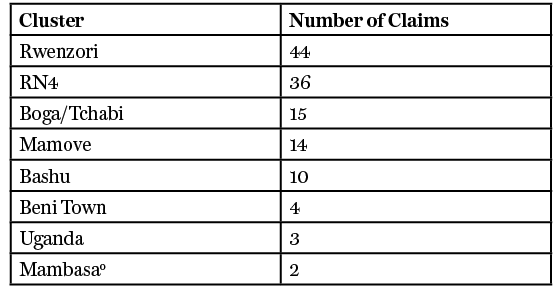

The ADF claimed more attacks officially through the Islamic State in 2021 than the previous two years combined, suggesting the group is becoming more integrated within the global media apparatus of the Islamic State: The Islamic State claimed 128 operations in DRC and Uganda in 2021, of which at least 68% correlated to confirmed or locally reported ADF attacks. The Islamic State had previously issued a total of only 94 communiques from the DRC in 2019 and 2020 combined.41

While the Islamic State’s 128 official claims by ISCAP-DRC only represent roughly 40% of the ADF’s total operations, this claims-to-attacks ratio sits at the higher end of the Islamic State’s global wings, or so-called ‘provinces.’42 For instance, official claims issued for the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS)m between January and September 2021 only accounted for 16% of the group’s overall activity according to data compiled by the authors.43 Meanwhile, researchers Gregory Waters and Charlie Winter found that the Islamic State’s claims in the central Syrian desert in 2020 only accounted for roughly 25% of the group’s overall operations in the region.44 The higher number for ISCAP may be the result of more consistent and accurate communications between field commanders and the Islamic State’s central media apparatus especially compared to other African provinces and/or a desire by the Islamic State to highlight its Central Africa operations to continue its core ideological component of territorial and operational expansion.

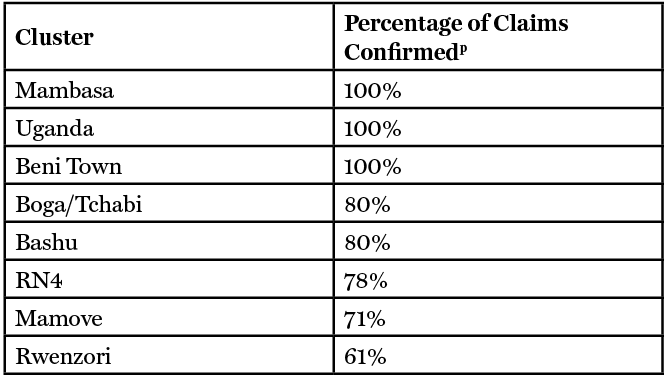

On the ground, the Islamic State’s official claims were largely based in DRC’s North Kivu province (the 72 claims in Rwenzori, Mamove, Bashu, and Beni Town), followed by Ituri (the 53 claims in RN4, Boga/Tchabi, and Mambasa), and Uganda (three claims). The Islamic State’s claims came from all six of the ADF’s geographic operational clusters,n Beni town, and Uganda, demonstrating the continued integration of the group across camps and international borders (see Table 1).

Table 1: ISCAP-DRC 2021 claims per geographical cluster

In comparing the proportion of claims that correlate to confirmed ADF attacks in each geographical cluster, it is clear there exists little variation between the clusters (see Table 2). The clusters with more operational output tended to have lower overall confirmation percentages compared to the clusters with fewer total operations. This may be because the Islamic State is keen to highlight attacks in areas in which attacks are rarer.

Table 2: Percent of 2021 claims confirmed per geographical cluster

The relatively high confirmation percentages between each geographical cluster suggest that each camp is able to maintain steady communication up the chain of command to report operations back to the Islamic State’s central media apparatus. It should be noted that these percentages account for the total number of claims that have been confirmed by the KST’s data. However, given the nature of the conflict—with civilians fleeing ADF territories and the ADF operating in very remote areas—it is possible that some attacks have gone unreported. Inconsistencies and mistakes in the Islamic State’s central media apparatus’ reporting of attacks may also skew this data.

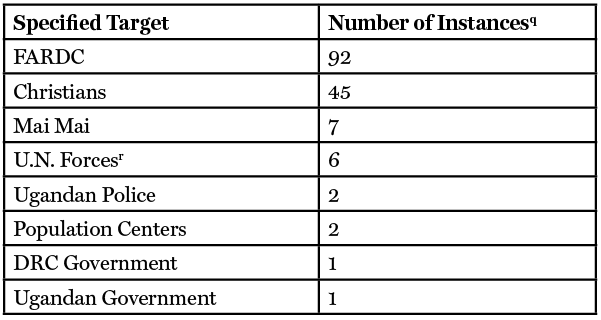

In terms of stated targets of the attacks, ISCAP claims in 2021 predominantly focused on the FARDC, followed by civilians, referred to as ‘Christians’ (see Table 3). Many communiques specified multiple targets in a single claim, thus resulting in the total number of targets being higher than the overall number of attack claims. It also bears noting here that in some instances, the stated target in a claim did not correspond to the actual targets reportedly struck on the ground, a practice seen within other Islamic State provinces. This is particularly true for some claimed raids against the FARDC that in actuality were perpetrated against civilians.

Table 3: Target types struck according to ISCAP-DRC 2021 claims

In terms of the methods of attacks specified by the Islamic State in its claims, assaults and/or ambushes were the most common (115), followed by arson (51). The Islamic State also claimed seven IEDs and three suicide bombing attacks—two in DRC and one in Uganda.s It also claimed two territorial occupations, one in North Kivu and one in Ituri, and two kidnapping/hostage-taking operations, both of which were against FARDC soldiers. One of the captured FARDC soldiers was later murdered, accounting for the Islamic State’s only communique explicitly claiming an execution of a hostage in Congo in 2021.45 The communiques often specified multiple methods in a single claim.

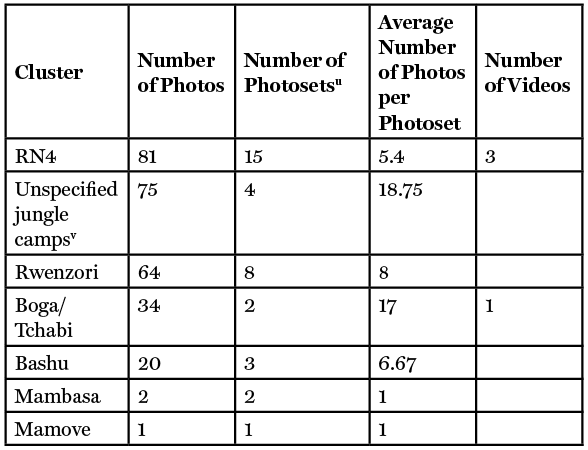

Much like official claims of responsibility, media officially released by ISCAP through the Islamic State’s central media apparatus greatly expanded in 2021. For instance, just 31 photos and one video were released in 2020. In 2021, however, the Islamic State on behalf of ISCAP released 277 photos and four videos, an increase of almost 800% over the previous year.t And whereas media released in both 2019 and 2020 were exclusively from Beni’s Rwenzori sector, the geographical scope of ISCAP media also significantly expanded in 2021.

Organizing ISCAP media releases into the ADF’s aforementioned clusters, it is evident that not only were the claims more geographically diverse than in 2020 but that every ADF cluster submitted media back to the Islamic State’s central media apparatus. In total, 115 photos and all four videos were released from Ituri’s Irumu territory (including RN4 and Boga/Tchabi clusters), 85 total photos from Beni territory in North Kivu (including Rwenzori, Bashu, and Mamove clusters), and two total photos from Ituri’s Mambasa territory (see Table 4).

Table 4: Number of media products released in 2021 per ISCAP-DRC geographical cluster

While all clusters produced media—demonstrating the ability of all ADF clusters to transmit media to the ADF’s central media team, which then transmits such media to the Islamic State’s media apparatus—there are clear disparities in media output between individual clusters. The volume and consistency of media generated by units operating along RN4 probably illustrates that this theater has been a priority for the group’s propaganda since its activity escalated there in June 2021, possibly due to its strategic importance as a critical transportation artery and enabled by relatively reliable cell phone service along the road.46 Conversely, the discrepancy between media output and the frequency of attacks by units operating around Mamove may be due to the lack of communications infrastructure in some of the more remote parts of the ADF’s area of operation, which could limit propaganda output despite those areas being a high priority for the group. The relatively large amount of photos published in relatively fewer photoset releases from inside the ADF jungle camps and the Boga/Tchabi area, by contrast, may be due to the difficulty of transmitting media from more remote areas with limited cell phone coverage (reducing the numbers of photosets that can be sent), with the greater size of individual releases possibly an attempt to compensate for the relative infrequency of releasing media from those locations.

The group’s media, while becoming more integrated than previously within the global Islamic State media apparatus, also featured clear evidence of the group’s organizational and ideological affiliation with the Islamic State more broadly. For instance, all 75 photos emanating from the ADF’s jungle camps were used as part of an Islamic State media campaign showing its members around the world celebrating both Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. The fact that the ADF participated in this campaign suggests that it specifically coordinated its media output in this regard with the Islamic State’s central media apparatus, as the Islamic State presumably passed on a wish-list of photos it wanted for this campaign. One of the photos released from an unspecified jungle camp also featured ADF leader Musa Baluku, marking the second time he was explicitly featured in official Islamic State media.w One photo released from the group’s Boga/Tchabi cluster featured an ADF member engaging in dawa, or proselytizing to locals in an effort to convert them to the Islamic State’s version of Islam. As will be discussed later in the article, this was the first documented instance of the ADF engaging in such behavior for the Islamic State. Other photos also demonstrated clear homages to violent Islamic State motifs, such as a November 2021 photo showing ADF members dressed in black kanzusx holding the severed head of a killed FARDC soldier and a similar photo also showing men in black kanzus released the same month (see below). The latter photo was in the style of traditional Islamic State propaganda, particularly during the height of its territorial caliphate in Iraq and Syria.

Unlike official media released by the Islamic State, media internally produced by the ADF and intended for more local audiences suffered a decline in 2021. The group produced and directly released a long list of propaganda videos in 2020, many of which explicitly referenced its loyalty to the Islamic State. However, the small amount of media that was directly released by the group in 2021 continued to show the group’s internal branding and identity as part of the Islamic State. For instance, videos released directly by the group, such as a November 2021 video from Komanda, Ituri, prominently featured the logo of the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province.48 Other videos, such as the internal ADF beheading videos described in the next section, included clear Islamic State rhetoric.

The relative paucity in 2021 in directly released ADF media is likely due to the group’s further integration into the global Islamic State media apparatus. Given the substantial increase in ADF media released by official Islamic State channels in 2021, it is possible the group focused more on providing media to the Islamic State’s central media apparatus than producing media itself for local consumption. This integration of media production into the Islamic State’s broader propaganda apparatus likely demonstrates the enthusiasm of the ADF’s leadership for their membership within the Islamic State’s global infrastructure. Moreover, it also demonstrates the ADF’s adherence to the Islamic State’s media requirements in that global provinces are to submit media back to the Islamic State’s central media diwan, or department, for centralized releases.49

2. ADF Begins Producing Beheading Videos

The second change is that the ADF began releasing beheading videos in the summer of 2021, a phenomenon best explained by the group’s desire to align itself more clearly with the Islamic State’s overall brand by imitating the global jihadi organization’s infamous hyper-violence. The three beheading videos were distributed by the ADF’s internal media apparatus and circulated on Congolese social media. The video’s production and content falls in line with what Jason Warner, Ryan O’Farrell, Héni Nsaibia, and Ryan Cummings describe as the “normative adoption” of the Islamic State’s practices by its affiliates around the world.50 As stated by Warner and his co-authors, “[Islamic State] provinces’ behaviors were often informed informally by the normative adoption of the IS brand as they sought to mimic what IS Central was doing.”51 So while the beheading videos may not have been the product of direct orders from Islamic State Central—especially given that the Islamic State did not distribute them through its official channels—their production nevertheless demonstrated that the ADF was taking it upon itself to become more Islamic State-like as part of its newfound identity.

All three videos consisted of ADF fighters giving speeches with clear references to the Islamic State, threats against the ADF’s local and international opponents, and religious justifications for the beheadings themselves. The ADF had never before produced and released such videos, and they constitute a clear imitation of the Islamic State’s own grisly releases similar to the series of infamous beheading videos featuring the Islamic State’s ‘Jihadi John.’52

The ADF released the first of the videos on June 5, 2021, featuring a light-skinned young man in a FARDC uniform who begins beheading a man in civilian clothes while others hold the victim down or watch.53 The man who carried out the beheading is Kenyan national Salim Mohamed Rashid, who arrived in the ADF camps in late 2020, as discussed below.54 Once the victim is no longer moving, the assailant pauses to deliver a speech in Swahili, proclaiming:

Truly, this is the Islamic State that has come to slaughter, we have come to slaughter you, we have come for you infidels with machetes, O you infidels. O America, we have come for you to slaughter you! O spies, we have come for you to slaughter you! O Kenya, we have come for you to slaughter you! Tshisekedi [referring to Felix Tshisekedi, the current President of the DRC], we have come for you with machetes, Allah the Most High willing. Allah the Exalted willing, Islamic State: long live! Islamic State: long live! To our leader, know that you have soldiers within Congo that pledge allegiance to you that we shall hear and obey you …

Almost two weeks later, on June 18, the ADF released a second beheading video, this time showing 14 men in civilian clothes tied up and kneeling in a jungle setting.55 A man off-screen explains that they are prisoners of war who have refused to convert to Islam and that the punishment for this is death. He then declares, speaking of those who are about to carry out the beheadings, “These are soldiers of Caliphate. These are soldiers of the Caliph to believers, yes, Abu Ibrahim Al-Quraishi.y May Allah protect them. Allah willing, they are going to do an act of worship to fulfill Allah’s command!” The video then shows young boys being brought in to help with the beheadings, and all 14 men are killed.

While most of the perpetrators in this video have not been individually identified, they refer to Boaz, a known ADF commander, and an ADF fighter named Isa can be briefly seen on-camera.56 Isa, a Congolese fighter whose real name was Mbudi Abdallah and went by a kunya of Abu Khadija,57 would later carry out a suicide bombing outside a bar in Beni town on June 27, 2021, the ADF’s first such attack, as described above.58

The third beheading video, shared online on June 26, 2021, showed three men and a woman in civilian clothes tied up in a jungle setting.59 A group of more than a dozen boys and men are gathered around them. A light-skinned man speaking Swahili with a Kenyan accent declares that, according to Allah, the only way to achieve victory is to cut off their enemies’ heads. The four executioners do so to shouts of the Islamic State’s battle cry: “Dawlat al-Islam! Baqiya!”

3. The Adoption of Suicide Bombings

The third change, and arguably one of the ADF’s most significant new operational trends beginning in 2021, was its undertaking of suicide bombings as part of its campaign of terror. This change has come as a direct result of its integration into the Islamic State, as the ADF has enthusiastically implemented tactics more aligned with the Islamic State’s operational toolkit. It is so far unknown if the Islamic State’s central leadership has demanded this of its Central Africa affiliate, or if the ADF chose to adopt the tactic as part of its consistent enthusiasm for its adopted identity as part of the Islamic State’s global hierarchy.

That said, the ADF took it upon itself to start laying the ideological and religious groundwork for suicide bombings as early as March 2021. In doing so, ADF’s ideologues framed suicide bombings within the Islamic State’s overall operational template and thus something in which the ADF should now undertake. That month, ISCAP-DRC senior ideologue Abu Qatada al-Muhajir (see photo) said in a widely shared sermon to the group that a “martyrdom vest [is what] a leader wears all the time for self-destruction and defense, this is worn by every [jihadi] commander.”60 He added, “they will soon get all of you those martyrdom vests, which you will be required to wear,” urging the fighters to “pray that Allah makes it possible for you to die with a martyrdom vest that blows hundreds of infidels.” Al-Muhajir also contended that ADF leader Musa Baluku himself “has to put on his martyrdom vests or belt on a daily basis as a defensive mechanism against being arrested and subsequently tortured by infidels,” as according to al-Muhajir, “it is compulsory for all Islamic leaders to wear it [a martyrdom vest] daily.” Among the ‘Islamic leaders’ explicitly mentioned by al-Muhajir as wearing the so-called martyrdom vests was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the former Islamic State leader, further showing that the ADF’s ideologues explained undertaking suicide bombings to its rank-and-file within the framework of how the Islamic State operates more broadly.

Three months later, the ADF put these teachings into practice for the first time when on June 26 and 27, 2021, the group detonated three bombs in the northeastern DRC town of Beni, the third in the form of a suicide attack. Targeting a bar near the town center, the aforementioned ADF fighter known as Isa or Abu Khadija al-Answar (or al-Ansari) blew himself up. Two civilians were injured in the blast, and only the bomber was killed.61 As with the bombing earlier that day, the IED appeared to be remote controlled and was reportedly not originally intended as a suicide bomb. Internal messages from the group, however, indicate that Isa chose to turn it into such when he was prevented from entering the bar. It is also possible a malfunction caused the bomb to explode early. Regardless, the Islamic State claimed the attack as a suicide bombing—the first by its Central Africa Province.62

Two months later, the ADF began trying to export this tactic to Uganda. As will be outlined in more detail below, in August 2021, a successful security operation prevented the first would-be suicide bombing by the group in that country,63 while a second attempted suicide bombing, this time in October 2021, killed only the bomber himself.64 The group’s third attempt, however, resulted in three near-simultaneous blasts in downtown Kampala on November 16, 2021, that killed four people and injured dozens more.

The town of Beni in the DRC was also the location for the ADF’s final and deadliest suicide bombing of 2021. On Christmas Day, as people congregated in a popular restaurant to celebrate the holiday, a suicide bomber detonated himself at the restaurant’s entrance after being refused entry by local security.65 The blast immediately killed six people, while another 20 civilians were injured. Hours later, two additional people succumbed to their wounds, raising the death toll to eight.66 The relative effectiveness of the Christmas Day attack may reflect improvements in bomb-making or more effective target selection, as this bombing hit a packed restaurant while the November 16 bombers in Kampala had detonated their explosives in the middle of the street.

Through the adoption and continued use of suicide bombings, the ADF has shown a clear ideological and tactical shift since officially joining the Islamic State. The relatively quick operationalization of the tactic—insofar as the group perpetrated its first suicide bombing just a few months after the first known efforts to sensitize the tactic to its members—evidences the group’s implementation of the tactics of the Islamic State and its deepening commitment to the ideological justifications that underpin them. This dynamic again fits into the “normative adoption” model as mentioned above. It appears that the ADF has taken it upon itself to start implementing suicide attacks as a result of its newfound identity as part of the Islamic State.

4. Outreach to the Banyabwisha

The fourth major shift in the ADF’s behavior in 2021 was its first publicized attempt at dawa, or proselytizing, to local communities. Though there is no clear evidence that these efforts were the result of direct orders from the Islamic State’s central leadership, the ADF’s documentation of these dawa attempts for publication by Islamic State media indicates that the relationship between the two groups played a role in the ADF’s actions.

During the summer of 2021, the ADF publicized its engagement with the predominantly Christian Congolese Hutu community in Irumu territory, locally referred to as Banyabwisha. The group’s engagement with the community represents the ADF’s first real foray into community outreach in over a decade—and the first time the engagements have been categorized as dawa, or proselytizing, by the group.

The ADF, as a primarily foreign militant group professing an extremist interpretation of Islam in a region with a very small Muslim community, has in recent years largely avoided attempting to foster legitimacy within neighboring communities. While significant intermarriage took place in the 2000s between ADF personnel and the Vuba ethnic minority in northern Beni,67 the ADF since its 2015-2016 pivot toward the Islamic State has largely relied on recruits from outside its area of operation—recruited both from elsewhere in Congo and farther abroad—or resorted to kidnapping and forcibly recruiting locals.68 Its engagement with the Banyabwisha community in Irumu suggests an attempt to change this dynamic and foster local community relations.

The Banyabwisha in Irumu are a relatively recent migrant community, with many immigrating to the territory to purchase, clear, and farm land after fleeing instability and hostility in Masisi territory farther south.69 Their entry into Irumu territory, particularly the areas around Tchabi and Boga, has led to extreme hostility with longstanding communities—referred to as autochtones, or indigenous—from whose customary leaders Banyabwisha migrants often bought land.70 In 2020, repeated episodes of violence erupted between Banyabwisha and ethnic Nyali over land rights. Nyali, Nande, and Hema communities often rejected the legitimacy of the Banyabwisha presence, a hostility reflected in official government statements pledging to remove the Banyabwisha.71 Accusations against the Banyabwisha included assertions that they are Rwandans attempting to steal land and that they collaborated with the ADF in its attacks against neighboring communities.72

On May 31, 2021, a series of massacres took place in Tchabi and Boga in which ethnic Nyali communities were reportedly targeted by ADF fighters, Banyabwisha were reportedly spared, and Banyabwisha militia allegedly supported the ADF’s attacks.73 This was followed by nine ADF attacks in June 2021 and three attacks in July 2021 in which Banyabwisha fighters reportedly assisted the ADF.74 On July 1, 2021, local residents massacred at least eight Banyabwisha civilians in Komanda, 90 kilometers northwest of Tchabi where the previous attacks took place, accusing the Banyabwisha of collaborating with the ADF.75

In early August 2021, a series of videos emerged on both the ADF’s internal media channels and wider Congolese social media in which approximately 15 men claiming to be Banyabwisha described to senior ADF leader Muhammed Lumwisa76 their flight from Komanda and Bandinbese after the July 1 massacre and their rescue by the ADF.77 Calling on other Banyabwisha in Masisi territory to join them with the ADF in Irumu, the men framed their relationship with the ADF as a move that would help them reclaim their Congolese citizenship, something often denied by rival communities accusing the Banyabwisha of being Rwandan. A few days later, the Islamic State’s central media apparatus released a statement and picture of the ADF reaching out to locals in the Tchabi area in an attempt to convert them to Islam, the first time the Islamic State—or the ADF—has publicly advertised attempts at dawa, or proselytizing, toward Christian communities in Congo.

While reported cooperation between the ADF and a Banyabwisha militia, and clear attempts by the ADF to recruit among the Banyabwisha, suggest that the ADF’s intentions were to foster a domestic recruitment base through capitalizing on pre-existing inter-communal tensions, the results appear mixed. In August 2021, at least two confrontations occurred between the ADF and the DRC military FARDC in which Banyabwisha fighters supported the FARDC, as well as a third incident in which the ADF attacked a Banyabwisha militia outright.78 The FARDC had reportedly recruited Banyabwisha militia as proxies against the ADF, including some Banyabwisha militia members who had reportedly defected from the ADF.79 As of early 2022, it appeared that some Banyabwisha individuals remained part of the ADF but are reportedly perceived by leadership as unreliable and likely to defect.80

This sequence of events—with the ADF reportedly cooperating with some Banyabwisha militia, publicly attempting to recruit among them, other Banyabwisha militia siding with FARDC against the ADF, and Banyabwisha recruits ultimately being seen as unreliable—leaves many questions. The ADF has clearly attempted to exploit intercommunal tensions between Banyabwisha and other communities in order to recruit locals and publicize their efforts themselves and through the Islamic State’s central media apparatus, but they appear to have incurred some level of backlash or rejection by other segments of the Banyabwisha community.

The degree to which the ADF have been successful in presenting themselves to the Banyabwisha community as allies or protectors remains uncertain, as does the degree to which the ADF may see these dynamics as a model to replicate elsewhere in its areas of operation. It is almost certainly no coincidence that the ADF’s foray into attempting to build local legitimacy—quickly publicized by both the group and the Islamic State itself, which frequently emphasizes dawa activities by its other affiliates81—has occurred since its 2016-present evolution into an Islamic State affiliate. As with other shifts in the ADF’s modi operandi, the ADF’s explicit framing of attempts at domestic recruitment as dawa may not be the result of directives from the Islamic State, but are clear indication of the Islamic State’s influence over the group’s trajectory.

5. Deepened Foreign Recruitment

The ADF’s transformation into an Islamic State affiliate has also coincided with a large influx of foreign recruits from across the region. According to recent defectors, hundreds of foreign fighters from beyond the ADF’s historical recruitment base in Uganda have reportedly journeyed to ADF camps in eastern Congo since October 2016, particularly from Tanzania, Burundi, Kenya, and South Africa. These recruits are reportedly far more ideological in their motivations, and many desired to join the ADF specifically because it is now part of the Islamic State.82 This stands in sharp contrast to the narrative, common for many years among Ugandan and Congolese ADF defectors, of being tricked into joining the group with promises of employment.83 z

While the ADF has historically included isolated fighters from several countries beyond Uganda and Congo, this large influx of regional recruits has resulted in some important shifts in the ADF’s internal practices. Regional recruits from outside DRC have reportedly been given special treatment, taking on new levels of prominence and causing friction with other recruits or existing fighters.84 By summer 2019, ADF leadership was reportedly instructing combatants and civilians within its camps to converse in Swahili in order to facilitate communication between members with diverse origins.85 This regionalization in recruitment activities is similarly reflected by the emergence of numerous Telegram channels run by ADF personnel distributing Islamic State propaganda—with a focus on the ADF’s activities—in regional languages like Swahili and English, in addition to longstanding propaganda efforts in Luganda. By early 2021, the flow of regional recruits had become important enough that a special camp for non-Ugandan foreign fighters was reportedly established in Ituri, a notable departure from the ADF’s historical practice of filtering largely Ugandan foreign fighters and Congolese recruits through its camps in the Semuliki river valley in southern Beni territory.86

The trajectories of several individuals who joined the ADF in late 2020 and 2021 illustrate these shifts, and how the ADF’s integration into the Islamic State has enabled the group to take advantage of and co-opt pre-existing jihadi networks that have historically funneled recruits elsewhere. At least two of the ADF’s recent regional recruits have had prior experience with jihadi cells and presumably passed on some of their expertise to the group. One was Kenyan national Salim Mohamed Rashid, who joined the group in late 2020 and appeared in the ADF’s first ever beheading video in June 202187—the first time that a Kenyan national has been featured in an ADF propaganda video.88 He had previously been arrested in Turkey in 2016 for attempting to join the Islamic State’s ranks in Syria before he was deported back to Kenya.89 Rashid was arrested again in early 2019 for what Kenyan officials said was his alleged role in a cell of the Somali militant group al-Shabaab near Mombasa, Kenya, and was further accused of having been in possession of explosive materials prior to his arrest.90 aa Subsequent information casts doubts on these accusations, indicating rather that Rashid remained an Islamic State supporter throughout this time and joined the ADF to further that cause.91 Rashid’s time in the ADF, however, was relatively short-lived as he was arrested by the FARDC in late January 2022.92

Another was Mahmoud Salim Mohamed (subsequently referred to as Mahmoud), who was also a Kenyan national and also joined the ADF in late 2020. Mahmoud had been initially arrested in Malindi, Kenya, in 2016 for his alleged involvement in a series of purported al-Shabaab attacks in and near Mombasa.93 ab Mahmoud’s current whereabouts are unknown, though he has been reported dead by local sources.94

Perhaps even more illustrative of this shift toward personnel from outside the ADF’s historical recruitment base is the reported presence of a technical advisor sent by the Islamic State to the ADF’s camps in eastern Congo. In September 2021, local Congolese officials arrested Jordanian national Hytham S.A. Alfar as he was leaving the ADF’s camp in Mwalika in Beni territory, offering the first confirmed presence of an Arab member in the ADF’s camps.95 Also known as Abu Omar, Alfar was reportedly in the ADF camps to help the group improve its technological capacity,96 although the exact nature of the instruction he provided is unknown. The FARDC claimed that he was helping the ADF operate its drones.97 The use of technical advisors sent by the Islamic State’s global command to its African branches is not a novel phenomenon, as the Islamic State repeatedly sent advisors to assist its West Africa Province in Nigeria.98 ac If confirmed, the presence of technical advisors would indicate that the ADF has not only benefited from its integration into the Islamic State through the expansion of its recruitment pools, but also through the Islamic State’s attempts to improve its tactical capabilities.

While the influx of foreign fighters from beyond the ADF’s historical recruitment networks in Uganda began in 2016, the aforementioned events that took place throughout 2021—the creation of a special camp exclusively for foreign recruits, the enlistment of established jihadis, and the presence of an Arab trainer reportedly there on behalf of the Islamic State’s global command—illustrate a critical transformation for the group’s relationship with foreign fighters. Foreigners joining the group in 2021 that were shown to be more ideological, experienced, and on the ground were afforded a degree of importance not seen with either Ugandan recruits or even with foreign fighters over previous years. The ADF is now clearly tapping into regional Islamic State recruitment networks and more clearly emphasizing the importance of foreign fighters. This bears tremendous importance for the ADF going forward, potentially bolstering both its numbers and its tactical proficiency.

6. The Move to Export Terror Outside the DRC

The sixth change seen in 2021—and already referenced in the suicide bombing section above—was the ADF’s efforts to export its new brand of terror to neighboring countries, which was both enabled by Islamic State funding and encouraged by Islamic State Central leadership. This encouragement is unsurprising given the transnational aims of that network. Indeed, Baluku stated in a May 2021 sermon that he had received orders to expand the group’s territory,99 and a source close to the group indicated that Islamic State Central specifically encouraged operations in Uganda.100 Additionally, money received through Islamic State-affiliated networks helped fund the ADF’s regional operations and bombing campaigns.101

Although the ADF conducted numerous operations from Congo into Uganda in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as well as mounting an urban bombing campaign in Uganda in 1998 and 1999 that killed dozens, its cross-border operations essentially ended by 2007 after several successive military operations by the UPDF.102 Since then, the group has likely been responsible for as many as 14 targeted assassinations in Uganda between 2011 and 2017,103 but had not attempted any mass-casualty attacks until August 2021. Overall, from June to December 2021, the ADF was responsible for at least one assassination attempt and a series of bombings and attempted bombings in Uganda and Rwanda, which represents a sudden and sustained escalation from the past 15 years. These renewed operations largely fall under the Islamic State’s core ideological component of tatamadad, or the ideological need to expand the territorial caliphate.104

The jihadi group’s renewed external operations began in June 2021 when ADF gunmen attempted to assassinate General Katumba Wamala, Uganda’s Minister of Works and Transport and former chief of defense forces, in Kampala.105 While General Wamala survived the assassination attempt, his daughter and driver were killed in the attack. The attempt on General Wamala’s life marked the return of the ADF’s Ugandan-based offensive operations, which had been dormant since 2017 when the group killed Ugandan Police Force spokesman Andrew Kaweesi.106

As noted above, in August 2021, the ADF began a series of bombing attempts across Uganda. That month, on August 27, Ugandan officials reported that security forces thwarted a suicide bombing plot targeting the funeral of Paul Lokech, a Ugandan general who had played a prominent role in Somalia and in previous operations in eastern Congo against the ADF.107 The bombing cell attempted to detonate a suicide vest during the funeral in Pader.108 Despite being unsuccessful, the Pader plot represents the ADF’s first suicide bombing attempt inside Uganda and its second suicide operation overall.

On October 7, 2021, a small explosion occurred outside of the main police station in Kampala’s Kawempe neighborhood, causing no injuries and minimal damage.109 Ugandan authorities only acknowledged the bombing at the police station after another IED detonated in Kampala’s Komamboga neighborhood on October 23, which left one person dead at a pork joint.110 Both bombings were claimed by the Islamic State.111 Two days later, on October 25, a suicide bomber detonated his bomb on a bus in Uganda’s Mpigi District, killing himself and seriously wounding at least one other person.112 The Islamic State did not comment on that explosion, but in all three bombings, Ugandan government officials publicly blamed the ADF.113

Finally, on November 16, 2021, came the triple suicide bombing in Kampala. At approximately 10:00 AM, a suicide bomber attacked Kampala’s Central Police Station, followed just minutes later by two suicide bombers detonating themselves near the parliament building.114 The twin blasts killed four victims, and over 30 more were hospitalized for their wounds, including more than two dozen police officers.115 In the hours following the bombings, the police shot a man they claimed was a fourth suicide bomber.116 A search of his home allegedly revealed a suicide vest and other explosive materials.117 The Islamic State’s central media apparatus was quick to claim the November 16 attacks, declaring that three of its “knights” attacked the “polytheistic” parliament and “Crusader” police.118 The claim identified the bombers by their aliases of Abdul Rahman al-Ugandi, Abu Shahid al-Ugandi, and Abu Sabr al-Ugandi, while Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni reported that two of the bombers were named Mansoor Uthman and Wanjusi Abdallah and that both were Ugandan citizens.119

ISCAP’s external operations were not just contained to its native Uganda. The Rwandan government announced on October 1, 2021, that it had arrested 13 people who it said were connected to the ADF inside the capital Kigali and two other districts in the country’s north and southwest.120 The Rwandan government elaborated further, stating that the 13 were arrested “with different improvised explosive device (IEDs) materials that include: wires, nails, phones, explosives and videos for radicalization.”121 The arrests had taken place in both August and September 2021 but were only disclosed to the public in October 2021.122 Despite anti-Rwandan motifs playing a large role in Islamic State-supporter propaganda since August 2021—presumably because of Rwanda’s role in routing the Islamic State affiliate in Mozambique—the Islamic State’s central leadership has not officially mentioned any activity inside Rwanda.123

Ugandan officials, Rwandan sources, and detained individuals have identified senior ADF leader Meddie Nkalubo (see photo below) as the ringleader behind the aforementioned spate of bombings in Uganda since August 2021 and the foiled bombing plot inside Rwanda in September 2021.124 Ugandan police released a statement on October 26, 2021, linking Nkalubo to the bombings earlier that month in Kampala and Mpigi.125 Rwandan officials have also linked Nkalubo to the foiled plot in Kigali in September 2021.126 Nkalubo joined the ADF after disappearing from Kampala in March 2016, quickly becoming a central figure in the group’s adoption of jihadi imagery and propaganda techniques. He later became a key organizer in financial transfers to the ADF from the Islamic State through Kenyan intermediaries.127

profile in March 2020

These bombings and attempted plots in both Rwanda and Uganda suggest one facet of the ADF’s new strategy is that it seeks to be a hub for regional attacks in Central and East Africa, even as the group expands its violence and reach inside eastern DRC. Where the ADF has the requisite networks, as seen with the plots and bombings in Rwanda and Uganda, it appears intent on organizing and undertaking terrorist activity. Sources close to the group indicate that these networks have continued to expand to other countries in the region,128 likely helped by the Islamic State’s frequent propaganda, as well as the ADF’s own outreach on its numerous Telegram channels that emphasize its role as an official affiliate (see previous section for further details). As the ADF’s recruitment networks expand, these recent plots suggest that the ADF may attempt to replicate such training and support for acts of terror across East Africa, potentially through the return of regional recruits to their home countries.129

7. Increased Clashes with Other Armed Groups

The final operational change of note in 2021 was the ADF’s increased clashes with other armed groups. Although it is likely that the decision to fight these groups was made locally, the opportunity and perhaps even the necessity of doing so appears to be the result of the group’s territorial expansion that was encouraged and partially funded by the Islamic State, as well as the ADF’s increased military capacity stemming from its influx of fighters in recent years.

Though the ADF’s overall emir Musa Baluku has implied he has received orders from the Islamic State’s central leadership to expand inside Congo,130 it is unclear whether this diktat included an order to be more aggressive with other armed groups, as likely occurred with the Islamic State affiliate in the Sahel.131 Regardless, multiple defectors report that in 2017, the year the ADF joined the Islamic State, the group was out of money and on the verge of collapse as Jamil Mukulu’s financing streams had dried up following his 2015 arrest.132 Indeed, there was only a single recorded ADF-caused civilian death in the first eight months of 2017.133 Access to new funding streams was reportedly one of the main considerations in propelling the ADF’s alliance with the Islamic State, and since its inception, the latter has provided the ADF with a fairly steady flow of financial support.134 ad This funding, along with increased recruitment due to the ADF’s notoriety as an Islamic State affiliate, has supported the ADF as it has pushed its operations into new territories inside Congo. This has in turn naturally brought it closer to other nearby armed groups, resulting in an increased rate of clashes between the militants.

While the ADF has clashed with other militant groups sporadically in the past, such clashes were exceedingly rare until 2021. The ADF’s expansion has increased the overlap in its area of operations, resulting in several clashes over the course of the year. Between May and July 2021, the ADF launched at least four attacks against the Patriotic Union for the Liberation of Congo (Union des patriotes pour la libération du Congo, UPLC), a longstanding Mai Mai group operating in southern Beni territory and northern Lubero.135 Then in September 2021, the ADF clashed with at least two Congolese militant groups in Irumu territory. The Islamic State claimed six of these eight attacks, specifically claiming that they were fighting members of an “apostate Christian militia” or militias allied with the “Crusader Congolese army” and releasing pictures showing their dead opponents.136

As the ADF continues to expand its areas of operation, both of its own volition and in response to the joint military operations, it is likely that clashes between it and other Congolese militant groups will continue to escalate. This may result in displacement of other militant groups weaker than the ADF and will likely exacerbate an already immensely complicated security environment for FARDC.

Conclusion

This article has argued that not only is the ADF now truly part of the Islamic State’s global apparatus as the Congolese branch of its Central Africa Province, but that the group’s integration into the global jihadi organization has resulted in several distinct evolutions as reflected on the ground by its operations over the course of last year. Accompanied by persistent financing from the Islamic State, the group’s (1) further integration into the Islamic State’s media apparatus, (2) production of beheading videos, (3) adoption of suicide bombings, (4) attempts at dawa, (5) deepened its role as a hub for more ideological foreign fighters, (6) expansion of its operating space in Congo and abroad, and (7) increase in the number of clashes with other armed groups in Congo signal that the ADF is no longer just a local threat to eastern Congo and minor threat to Uganda. ISCAP-DRC is becoming a significant transnational terrorist threat across East and Central Africa.

To be clear, while the ADF is part of the Islamic State’s global hierarchy, it has not lost its more localized agenda or strategy. Indeed, this is common for the Islamic State’s African provinces.137 ISCAP-DRC’s expanded area of operations in Congo and its proliferation of terrorist cells to neighboring countries has provoked a coordinated counter-offensive including intervention by the Uganda military, yet it remains to be seen whether these actions will sustainably erode the ADF’s capacity for violence. Past offensives have forced the ADF to pivot toward new areas, typically with disastrous results for civilians, where it has managed to regroup and continue its operations. Ensuring that these experiences are not repeated will require improved intelligence, flexibility, cooperation, and stamina on the part of local and regional security forces, and failure risks the continued expansion of ISCAP-DRC’s capabilities—now with far more severe implications for the entire region. CTC

Tara Candland is Vice President of Research and Analysis at the Bridgeway Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to ending and preventing mass atrocities.

Ryan O’Farrell is a senior analyst at the Bridgeway Foundation and the co-author of The Islamic State in Africa: The Emergence, Evolution, and Future of the Next Jihadist Battlefront. Twitter: @ryanmofarrell

Laren Poole is Chief Operations Officer at the Bridgeway Foundation. Before working to curb the rise of the Islamic State in Central Africa, he managed Bridgeway Foundation’s counter-Lord’s Resistance Army assistance project to the African Union in the Central African Republic.

Caleb Weiss is a senior analyst at the Bridgeway Foundation and research analyst at FDD’s Long War Journal. Twitter:@caleb_weiss7

© 2022 Tara Candland, Ryan O’Farrell, Laren Poole, Caleb Weiss

Substantive Notes

[a] In July 2010, three suicide bombers from al-Shabaab, al-Qa`ida’s branch in East Africa, detonated themselves in two neighborhoods of Kampala at large social gatherings of people watching the FIFA World Cup. Over 70 people were killed in those blasts.

[b] A note on language: While the group is officially the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province, it is most commonly referred to by its old name, the Allied Democratic Forces, in Congolese and Ugandan media and by officials in both countries. This report uses both terms interchangeably and does not differentiate between the two names; they both refer to the Islamic State-loyal group led by Musa Baluku in eastern Congo, which maintains cells across East and Central Africa. The use of the name ADF, on occasion, by the authors is for convenience and is not meant to minimize the group’s affiliation with the Islamic State.

[c] The use of MTM dates back to at least 2012, but it was unclear if the moniker referred specifically to the ADF’s main camp, known simply as Madina, or if it referred to the group as a whole. By 2016, however, MTM was indeed being used publicly to refer to the group writ large.

[d] On May 9, 2022, the Islamic State began referring to the insurgency in northern Mozambique—which since June 2019 had been labeled as part of “Central Africa Province” alongside the ADF—as its own “Mozambique Province.” “IS designates Mozambique as its own province following battle in Quiterajo,” Zitamar News, May 13, 2022.

[e] The Kivu Security Tracker (KST) is a joint project of the Congo Research Group (CRG), Human Rights Watch (HRW), and the Bridgeway Foundation. CRG oversees the collection and triangulation of data for the KST, the Bridgeway Foundation provides technical and financial support to the KST, and HRW provides training and other support to KST researchers but does not independently verify all incidents reported. The KST uses a network of local researchers to monitor and map violence by state security forces and armed groups in Congo’s North and South Kivu and Ituri provinces. Each incident is verified by multiple independent sources before being published.

[f] Combined with a series of other smaller attacks, this made Mamove the deadliest of ISCAP-DRC’s six geographic clusters, even though it was not the most active; both the Rwenzoris and RN4 suffered more attacks in 2021, but their final death tolls remained lower than in Mamove.

[g] “Interventions” refers to the unilateral Rwandan intervention in Mozambique beginning in July 2021, the South African Development Community’s Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) beginning in August 2021, and the Ugandan intervention in DRC beginning in November 2021.

[h] The U.S. State Department’s designation referred to the group as “ISIS-DRC,” or the ‘Islamic State in Iraq and Syria – Democratic Republic of the Congo,’ in its official designation. This article does not use this terminology, but notes this is indeed the same group designated by the State Department.

[i] In order to facilitate better analysis, the authors identified and distinguished between certain camps and the highly mobile sub-groups that comprise the fighting forces of ISCAP-DRC, assigning each an approximate geographic “cluster.” The six clusters identified as part of ISCAP-DRC’s operations are: Rwenzori, Bashu, Mamove, Mombasa, RN4, and Boga/Tchabi.

[j] MONUSCO is the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

[k] Although there are various internal and external elements that undoubtedly contributed to this territorial push, including the 2019 FARDC offensive that drove the ADF out of some of its traditional areas of operation, the Islamic State’s influence cannot be ignored here. The ADF’s alliance with the international jihadi group has dramatically improved its propaganda efforts, increased its recruitment opportunities, and opened up significant new funding streams.

[l] The FARDC military base at the Semuliki river bridge, also referred to as PK51, is the site of a former MONUSCO base attacked by the ADF on December 7, 2017, resulting in the deaths of 15 Tanzanian peacekeepers. The position was later transferred to the FARDC.

[m] Also known as the Islamic State West Africa Province-Greater Sahara (ISWAP-GS) following the Islamic State’s organizational restructuring of its West African wings in 2019.

[n] The data relating to attack claims was categorized into geographic clusters by the authors’ using KST attack data in an attempt to track where the ADF maintains its large semi-permanent and mobile camps across North Kivu and Ituri provinces.

[o] The border areas around Mamove between North Kivu’s Beni territory and Ituri’s Mambasa and Irumu territories are delineated slightly differently depending on the specific map employed. It is possible that attack claims for Mambasa are much higher but have been categorized as part of the ADF’s ‘Mamove’ cluster.

[p] ‘Confirmed’ meaning a particular claim matched an ADF attack confirmed by the Kivu Security Tracker.

[q] ‘Instances’ meaning how many times this type of entity was targeted, according to the Islamic State’s claims.

[r] Referring to peacekeepers who are part of the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or MONUSCO.

[s] Referring to the June 27, 2021, and December 25, 2021, suicide bombings in the DRC and the November 16, 2021, suicide bombings in Uganda.

[t] Over half of the media products (51%) were released by the Islamic State’s central media, 40% was released by the group’s weekly Al Naba newsletter, and nine percent of all media was released through its Amaq News Agency.

[u] Defined in which a particular media release had two or more photos at a time for the same incident.

[v] Referring to photos released from inside one of the ADF’s many physical camps in the Congolese jungle; however, the exact location, camp name, etc. were not specified by the Islamic State. The authors thus grouped these media products into a single entity as “unspecified jungle camps.”

[w] The first time Musa Baluku appeared in an official Islamic State photo was in a similar photoset for Eid celebrations in the summer of 2019.

[x] Also known as thawb in Arabic, these are ankle-length garments traditionally worn by men across the Swahili Coast and much of East Africa, much like across the Arab world. Black kanzus, or thawbs, feature prominently in typical Islamic State media.

[y] This is a reference to then-Islamic State leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi, born Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Salbi, who took on the role of the Islamic State’s “caliph” after the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi on October 27, 2019, and was himself killed in a U.S. special forces raid on a house in northwestern Syria on February 3, 2022.

[z] It is worth pointing out that it is likely that some former members downplay their overall ideological affinity or commitment to the ADF or jihad in general after leaving the group.

[aa] Al-Shabaab here refers to al-Qa`ida’s East African branch. It should not be confused with the Islamic State affiliate in northern Mozambique that is locally referred to as al-Shabaab and comprised the other wing of the Islamic State’s Central African Province until being designated as its own province in May 2022.

[ab] While both Salim Rashid and Mahmoud were undoubtedly involved in extremist activity inside Kenya, the propensity for Kenyan media and government officials to label most terrorist activity as “al-Shabaab” makes it difficult to definitively ascertain if the two indeed had prior experience with al-Qa`ida’s East African branch or if the two were already within the Islamic State’s networks at the time of this activity and subsequent criminal charges regarding their alleged involvement in al-Shabaab. See Brian Ocharo, “Kenya: Terror Suspect Salim Mohamed Detained for 4 More Weeks,” Daily Nation, June 11, 2019; Richard Kamau, “Police Foil Planned Terrorist Attack in Mombasa as ‘Most Wanted’ Suspects Flee,” Nairobi Wire, January 6, 2016; and William Mwangi and Elkana Jacob, “Wanted terror suspect Mohamud Mohamed aka Gasere surrenders to police,” Star, January 5, 2016.