Abstract: Since October 7, in the wake of the “al-Aqsa Flood” terrorist attacks by Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), and other Palestinian factions from across the ideological spectrum, Iran’s aid to and strategic management of these groups has taken on a new level of relevance. The methods Iran has used to cultivate and maintain influence and control over disparate Palestinian groups follows the same pragmatic carrot-and-stick formula it has used across the Middle East with other proxies, with incentives that include financial aid, weapons, and training. The use of sticks was particularly important in Tehran’s restoration of influence over Hamas and PIJ after the Syrian civil war drove a wedge between Palestinian groups and Iran. The withholding of funds and a divide-and-rule approach helped Tehran get these groups back in line. More generally, Iran has worked to create and leverage splinter groups, particularly from the Palestinian Authority’s dominant Fatah Movement, to grow its influence in Gaza and the West Bank. Tehran has also strived to build influence among leftist Palestinian groups to create a broad coalition of partners. And it uses umbrella groups and joint operations rooms to try to bolster the unity and coherence of its Palestinian network.

On the morning of October 7, 2023, rocket barrages from the Gaza Strip consisting of around 2,0001-5,000a rockets began to hit targets in southern Israel. Armed motorized paragliders and gunmen in trucks, on motorbikes, and technicals streamed through holes blown through Israel’s once-vaunted border fence and began firing on a mixture of civilian and military targets.2 Seaborn divers and small boats attacked other targets on Israel’s coast.3 Around 1,200 Israelis were killed and around 3,500 wounded; over 240 were taken hostage.4 There were many reports of rape, beheadings, and torture.5

Most of the fighters who crossed into Israel were members of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), but they were joined by gunmen from numerous smaller Palestinian factions. The scope, brutality, and audacity of the attacks, along with the weapons systems used, revealed a level of planning, destructiveness, and capability that surprised many analysts both in and out of government.6

One common thread linking the attackers were their extensive financial, military, and political connections to the Islamic Republic of Iran. As this article will outline, these associations were the product of extensive cultivation and management of a Palestinian “Axis of Resistance” by Tehran over many years.

Along with spreading the Islamic Revolution, one of the main goals of the late Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini was the destruction of Israel.7 In fact, once Iran’s Shah was deposed, it was Khomeini who then invited Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasir Arafat to Iran, where he was allowed to take over office space in the former Israeli embassy.8 Arafat himself told a crowd of Iranians that with Khomeini in power and the Islamic Revolution established, “the road to Palestine now leads through Iran.”9 Since that time, Tehran has never abandoned the goal of Israel’s destruction.10

Iran currently lacks the conventional military capability for a heads-on confrontation with Israel. Proxy forces have allowed Iran to maintain some level of plausible deniability, while asymmetrically supplying Tehran with a means to effectively strike Israel or apply pressure to it. Furthermore, Iran’s creation of proxy forces has facilitated the spread of Iranian Islamist ideology.

As yet, no ‘smoking gun’ has emerged of direct Iranian involvement in or greenlighting of the October 7 attacks.11 This may reflect the opacity of many proxy-related activities by Iran and Tehran’s deliberate pursuit of plausible deniability. Alternatively, it may reflect the fact that while Iran cocked the gun, it was its Palestinian proxies that pulled the trigger. While praising those who carried out the October 7 attack, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei has repeatedly denied Iran played any direct role.12 Likewise on November 3, 2023, Hezbollah Secretary General, Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah, claimed the attack was “100 percent Palestinian” and that those who carried it out “kept it hidden … from everyone.”13

In his November 3 speech, Nasrallah also stated that Iran has “always been openly adopting and supporting resistance factions in Lebanon, Palestine, and in the region. However, they [Iran] do not exercise any form of control over these factions or their leadership.”14 This claim should not be taken at face value. As this article will outline, Iran has made many efforts over the years to maintain influence and control over what is calls the “Axis of Resistance,” and while it has not always succeeded in getting groups to do its bidding, it has always maintained significant sway over its network.

From around the time of the Syrian civil war, Iran has worked hard to cultivate new and old Palestinian proxies. As it did with Iraqi Shi`a militias in confronting U.S. forces in Iraq in the years after 2003,15 Iran has used Lebanese Hezbollah as a key go-between in creating and maintaining relationships with Palestinian groups. Given the large Palestinian refugee population in Lebanon, geographic proximity to the conflict zone, and Hezbollah’s loyalty and reputation as a leader within the “Islamic Resistance” against Israel, Iran has been able to rely on Hezbollah as a strong agent of influence. Further proxy-building efforts by Tehran among Palestinian groups have involved heavy financial incentivization,16 supplying weapons,17 assistance with propaganda,18 and the formation of unified umbrella groups to foment greater cooperation between Iran’s proxies.19

Yet, Iran has not only utilized carrots in its dealings with its Palestinian allies; it has also made clear that those benefits can be taken away as quickly as they were introduced if these groups do not toe the line. Among the sticks Iran has brandished is the crafting of splinter groups to apply pressure against organizations that are or have become unaligned with Tehran.

In order to set the stage for analyzing Iran’s relationships with its Palestinian proxies, this article first examines Tehran’s attempt to create loyalist splinter groups in Iraq out of insufficiently dependable Shi`a groups such as Moqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army to advance its interests. Next, the article outlines how after the Syrian civil war created a wedge between Tehran and Palestinian groups, Iran used carrots and sticks to restore influence over Hamas and PIJ. The third part of the article outlines how Iran has leveraged splinters, particularly from the Palestinian Authority’s dominant Fatah Movement. These groups formed a potent addition to Hamas and PIJ’s power in Gaza and allowed for a broader cross section of influence within Palestinian ranks. Tehran viewed Fatah as an entity to both neutralize and utilize. Fighters that had split from Fatah formed one element of the larger Hamas-led attack on October 7.

Iran did not just focus on Fatah. As outlined in the fourth part of the article, it has also engaged leftist Palestinian groups. These partnerships and efforts at proxy building have demonstrated Tehran’s desire to act to build a coalition of a wide cross-section of Palestinian armed groups.

The fifth part of the article outlines how Iran has followed-up on its new relationships with Islamist and leftist groups by reworking them into umbrella structures and joint operations rooms to boost the unity and coherence of its network. The final section then offers some conclusions. In the appendix, the author has included a table with details on the main Palestinian armed Islamist groups, the Fatah splinters, and Palestinian leftist armed groups.

Part One: Iran’s Use of Splinters in Iraq

Recruiting and utilizing splinters from other larger more dominant groups, often from groups that oppose Iran, has been a key Iranian strategy when it comes to the cultivation of proxy groups and networks.20 For Iran, this formula has worked particularly well over the years with Iraqi Shi`a militias. Iran’s formulaic approach, proven with these Shi`a militias, was then replicated for use with Palestinian factions.

Iran’s attempts to splinter more dominant and/or oppositional groups in Iraq is instructive with what it has attempted to do in the Palestinian context and particularly with Fatah. During the Iraq War (2003-2011) when radical Shi`a cleric Muqtada al-Sadr was leading his Mahdi Army (Jaysh al-Mahdi), numerous splits within the group began to develop due to his leadership and strategy. Al-Sadr had a mixed relationship with Iran, sometimes aligning with it21 and at other times opposing Tehran.22 In 2006, a group known as Asa`ib Ahl al-Haqq (League of the Righteous) split from al-Sadr’s ranks and soon received Iranian aid.23 Asa`ib Ahl al-Haqq’s then and current leader, Qais al-Khazali, was a founding member of Muqtada al-Sadr’s powerful Office of the Martyr Sadr and a close aide to al-Sadr.24 But he became fed up with al-Sadr’s management style and began working to build his own network.25 In so doing, he took advantage of his contacts with Iran’s IRGC-QF and numerous leading clerics that he had established during his prior visits to Iran with al-Sadr.26 This was exploited by Iran, which offered cash, training, and weapons.27 Asa`ib Ahl al-Haqq has since grown into a major player within Iraqi politics and within the Iraqi government funded and recognized al-Hashd al-Sha’abi (the Popular Mobilization Forces) militia umbrella group.28

Other proxy networks were also carved out of al-Sadr’s ranks by Iran. When al-Sadr opposed sending additional Shi`a fighters to the Syrian War, some Sadrist leaders and their networks disagreed with his decision.29 Tehran exploited that division by facilitating the transfer of Shi`a militiamen belonging to these networks to Syria and supplying the know-how to build separate groups.30 From 2013-2016, the Iranians fostered the growth of groups such as Kata’ib al-Imam Ali (the Imam Ali Battalions), led by Shibl Zaydi, a former Mahdi Army commander.31 An additional Sadrist splinter was Jaysh al-Muwwamal, led by another former commander of Jaysh al-Mahdi’s successor group, Saraya al-Salam.32 All of these efforts have provided Iran with a growing influence in Iraq and larger forces to draw on to serve Iranian interests. In addition, the pressure and threats of pressure Iran exerted on al-Sadr often forced him into more conciliatory positions vis-à-vis Iran because of concern over the loyalty of his own ranks.33

In 2012, when internal leadership issues arose within the Iraqi Shi`a militia group Kata’ib Hezbollah, instead of discarding a wide network of experienced personnel, Iran allowed the splinter group Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada to form the following year.34

A similar issue related to control and influence arose within Asa`ib Ahl al-Haqq, when one of its former leaders, Akram Ka’abi, split off and was allowed to form Harakat Hizballah al-Nujaba.35

The creation of these new groups from established organizations not only created groups more loyal to Tehran but also created pressure points on the original groups to stay in line.36 This was especially the case with Harakat Hizballah al-Nujaba’s relationship with Asa`ib Ahl al-Haqq when reports emerged that the latter was not always obeying instructions from Tehran.37 b From 2020-2021, when Asa`ib Ahl al-Haqq reportedly engaged in using front groups to launch rocket and UAV attacks against U.S. targets that had not been sanctioned by Iran, Harakat Hizballah al-Nujaba was brought forward to claim leadership of all front groups used to attack U.S. facilities and forces as well as domestic adversaries in Iraq.38 The effort was likely a move to reestablish Iran’s control and maintain a façade of unified Iranian control.

Part Two: How Iran Used Carrots and Sticks to Restore Influence Over Hamas and PIJ

Hamas and PIJ form the two largest and most important Palestinian proxies for Iran.39 The two groups pioneered the use of suicide bombings by Palestinian organizations in the 1990s-2000s,40 c with the former taking over Gaza in 2007. Both groups have built themselves into strong military and terrorist actors over a period of decades. With its closer ideological links and long relationship with Iran, PIJ has been Iran’s main proxy for much of its activities among the Palestinians.41 However, Hamas as the much stronger group was hard for Iran to ignore, and it actively cultivated the organization.42 For example, Hamas leader Khaled Meshal was hosted by Lebanese Hezbollah in January 2010 and met Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah.43 That same month, Israel reportedly killed a Hamas leader involved in smuggling Iranian rockets to the group in Gaza.44 By 2010, a year before the outbreak of the war in Syria produced tensions between Tehran and Hamas that were eventually surmounted, estimates of Iranian funding to Hamas exceeded $20-$30 million a year.45

With such cash injections, it appeared that Iran had secured influence for years to come. Yet, in 2013, the war in Syria presented Iran with new challenges for its relationship with various Palestinian proxies. Tehran deployed Shi`a militias with a history of sectarian animosity toward Sunnis to prop up the Assad regime. These forces were cast as “defenders of the [Shi`a] shrines” and the “Shi`a resistance.”46 Any foe of Iran or Hezbollah in Syria was branded “takfiri,”47 a term used to describe ultra-hardline Islamist extremists.d But in reality, the forces they were fighting on the ground were at times Syrian Muslim Brotherhood affiliates from similar ideological streams as Hamas.48 From 2013-2015, there were claims of current and former Hamas members joining and training Syrian rebel groups.49 In 2015, one leader from Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyyah, a Syrian Sunni Islamist group, claimed he had received videos from Gaza to assist in tunnel repairs in Syria.50

Palestinian camp-turned-neighborhoods, particularly Yarmouk, south of Damascus, were hotbeds of rebel and Sunni extremist activity and directly abutted Shi`a zones.51 This created discomfort for Sunni Palestinian groups such as Hamas and PIJ in their relations with Tehran. Advances made by Syrian rebel groups52 and growing sectarianism within the Palestinian territories added to the tensions.53 Furthermore, the wholesale destruction occurring in Palestinian areas within Syria54 resulted in many former proxies of Iran cooling their enthusiasm for Tehran or outright opposing it. With Tehran waging a sectarian war against fellow Sunnis in Syria,e for Hamas, the 13-month long presidency of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Muhammad Morsi in Egypt from June 2012 to July 2013 opened up the possibility of replacing the patronage of Tehran with that of Cairo.55

From 2012-2013, Tehran froze most of its funding to Hamas due to the group’s support for Sunni Islamist rebel groups in Syria and its open disapproval of Iran’s intervention in the conflict.56 In June 2013, the deputy minister of foreign affairs for Hamas in Gaza told Reuters, “Things are not easy … and we are trying to overcome the problem.”57 For its part, Hamas began courting Turkey and Qatar to fill the financial hole left by the Islamic Republic.58 Yet, the financial issues were taking their toll on the group. By 2014, Hamas sent signals to Tehran that it was seeking some form of rapprochement.59

Palestinian Islamic Jihad, for its part, maintained a more neutral position on the war in Syria, but like other Iranian-backed factions, it mostly escaped being penalized by Tehran for this decision.60 However, in 2015, when the group did not give messaging support to the Iranian-backed Ansar Allah (also referred to as the Houthis) in Yemen, the group reportedly lost for a period of time its Iranian funding.61 “Iran wants all the factions it considers its allies and gives money to support all the political and military positions that [Iran] executes in the region,” said one unnamed PIJ official in January 2016. “The [Palestinian] Islamic Jihad movement did not support the Iranian military and political positions, so relations became tense and it got bad.”62

Just like it had in Iraq to rein in group such as Asa`ib Ahl al-Haqq, Iran encouraged a group to splinter off PIJ, using this as a form of stick to put pressure on it. Peeled from the ranks of the PIJ in 2014,63 Harakat Sabireen was small by comparison to Hamas and its PIJ parent group. According to a March 2019 report by Al-Monitor, Iran had, “shifted much of its financial support instead to Sabireen.”64 However, Harakat Sabireen made up for its small size by its speedy assembly, increased funding by Tehran, flashy marketing, and its resilience even when Hamas made attempts to shutter the group.65 The group, numbering only around 300, also had leadership elements in Iran.66 Sabireen even adopted Lebanese Hezbollah-style iconography to further make clear its true loyalties.67 f Harakat Sabireen also actively disobeyed Hamas’ strictures when it launched rockets into Israel.68

By 2019, due in part to Iran’s withholding of funds and splinter group strategy, Hamas and PIJ had fully returned to the Iranian fold. Iran subsequently allowed Harakat Sabireen to fade and Hamas moved in to begin fully dismantling the group the same year.69 For Tehran, fallowing Sabireen was likely a minor sacrifice to rebuild links and more direct control over the larger and far more influential and powerful PIJ and Hamas. Carrots then further helped to surmount the tensions caused by the Syrian civil war. In 2023, Iranian funding for Hamas was reported to be around $100 million a year.70 This tripling of funding compared to 2010 only underlines Iran’s drive to keep Hamas’ rule of Gaza afloat.

protest in the city of Khan Yunis in the southern Gaza Strip. (Yousef Masoud /SOPA Images/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images)

Part Three: Iran’s Efforts to Splinter Fatah

In the Palestinian arena, Tehran applied the same concepts when dealing with Fatah, the most dominant member of the PLO and within the Palestinian Authority (PA). This does not mean that Iran has not tried to build close relations with the PLO and Fatah directlyg—it has. But Tehran’s fundamental differences with the PLO and by extension the Palestinian Authority’s role and relationship with Israel has regularly set the two at loggerheads, making such attempts difficult.71 Thus, Iran has focused significant efforts toward exploiting internal divisions within the PLO/Fatah/PA and encouraging disgruntled members to splinter off and, ideally, ally more closely with Iran.

Following the 2007 Hamas-Fatah War, Hamas stripped the Palestinian Authority and particularly Fatah’s leadership of their control and power in the Gaza Strip. Prior to that bout of violence, some Fatah members had had their own tensions with the Palestinian Authority under Mahmoud Abbas. These figures would later lead factions that often identified as Fatah, but often did not follow Abbas’s leadership.72 Others separated themselves from Fatah, or operated in an opaque sphere where Iranian aid could still flow to them while they maintained their links with Fatah and the Palestinian Authority.73

Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades Splinters

One part of Fatah that Iran has tried to create splinter groups from is the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade (Kata’ib Shuhada al-Aqsa), an Islamist military formation formed in 2000 by members of Fatah. Ostensibly, the group is still to this day a Fatah-controlled entity.74 Working to suck in splinters from the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade made sense for Tehran. Support for Palestinian Islamist groups, namely PIJ and Hamas, has long been a hallmark of Iranian policy. Ali Khamenei, the current Supreme Leader, has noted that “the foundations of this resistance rest on Palestinian jihad groups [emphasis by the author] and all faithful and steadfast Palestinians living inside and outside Palestine.”75

Following the destruction of the Palestinian Authority and by extension Fatah’s influence in Gaza, factions within the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade gravitated toward commanders who more often promoted violence than their “political” Fatah counterparts and who favored partnerships with Hamas or PIJ.76

Jaysh al-Asifa and Other Splinters

In 2012, one faction of al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, Jaysh al-Asifa (The Storm Army) was announced by the Palestinian Authority to no longer have no connections to it or Fatah.77 Jaysh al-Asifa had initially been known as the Martyr Imad Mughniyeh Groups,78 a Lebanese Hezbollah commander responsible for the deadly bombings of the U.S. embassy and Marine Corps barracks in Beirut in 1983, along with other hijackings, kidnappings, and murders throughout the 1980s.79 However, Jaysh al-Asifa still promoted itself as an entity associated with Fatah.80 Its leader, Salem Thabit (Abu al-‘Abd), told Raya Media Network in April 2014 that he wanted to unify Fatah military factions.81 Thabit worked to coordinate and organize the joint Hamas-al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade March 2004 double suicide bombing of the port of Ashdod.82 He also promoted strong relations with Hamas.83 The group did little to hide its links to Lebanese Hezbollah, telling the pro-Hezbollah daily Al-Akhbar in 2014 that “the relationship [between the Jaysh al-Asifa and Lebanese Hezbollah] had a major role in transferring experiences of the resistance from Lebanon to Gaza.”84 In 2015, Thabit spoke of further moves to “unify arms [of his faction and Hamas] against the enemy [Israel].”85 By 2020, operating primarily in Gaza, the group had undertaken joint operations with the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP).86

By 2013, other elements of al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade were thanking Lebanese Hezbollah and Iran for supplies of “weapons and equipment,” adding that the “main supporters for the Palestinian resistance” were Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, Hezbollah, and Iran.87 In 2015, Gazan sections of the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade openly asked Iran for money on television.88 One subgroup of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade—the Martyr Nidal Amoudi Brigade (Liwa al-Shahid Nidal al-Amoudi)—demonstrated its links to Iran by featuring Iranian weaponry, particularly with the Iranian-made AM-50 .50 caliber anti-material rifle.89

Additionally, al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade’s Gaza factions actively and increasingly participated in operations with Hamas, PIJ, and other Iranian-backed organizations. In the West Bank, the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades as a whole was increasingly seen as a stalking horse for Iran. In 2023, an unnamed Palestinian Authority security source told The Jerusalem Post that the group was being paid by Iran via PIJ.90

By October 7, factions that emerged from the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, including Jaysh al-Asifa and Liwa al-Shahid Nidal al-Amoudi, ceased posting regular updates on platforms such as Telegram. In fact, Liwa al-Shahid Nidal al-Amoudi stopped posting on October 5.91 Instead, pages generically belonging to the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade placed these groups back under the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade moniker and claimed responsibility for attacks launched by them on October 7. These included the videotaped kidnapping of an Israeli citizen,92 h small arms attacks on Israeli civilian structures,93 the capture and destruction of Israeli civilian and military vehicles,94 and one member of the group stomping on a dead body (presumably an Israeli).95

Harakat al-Mujahideen

While many elements of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades maintained their outwardly Fatah-affiliated branding, other elements within Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades grew into separate organizations with their own branding and structure. A case in point is the Harakat al-Mujahideen (Holy Warrior Movement), a Palestinian fighting group that participated in the October 7 attacks. The group released a video of “leadership inspecting [the group’s] forces” inside an Israeli village96 and of beheaded Israeli troops at the Fajah military base near Gaza in an October 8 video release.97

Harakat al-Mujahideen’s founder, Umar Atiya Abu Shari’ah, was also one of the founders of the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade in Gaza.98 Beginning in 2000, during the so-called Second or al-Aqsa Intifada, the precursor networks based along the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade’s began to coalesce under Shari’ah’s leadership.99 While elements of the Harakat al-Mujahideen have been established in the West Bank, its main powerbase has been in Gaza.100 In 2021, Asa’ad Abu Shari’ah, the group’s secretary general, stated there was “requirement for national unity” that would “bring together all of the leaders of [the Palestinian armed] factions.”101 After thanking God for the group’s development, he thanked “the Islamic Republic of Iran and Lebanese Hizballah as the main supporters of the Palestinian resistance,”102 demonstrating the group’s pro-Tehran orientation.

Other Fateh Splinters

The Popular Resistance Committees

Harakat al-Mujahideen were not the only splinter from Fatah to grow into a new organization. Another group that grew out of Fatah was the Popular Resistance Committees (PRC). The group claimed it worked with Hamas and other Palestinian groups in carrying out the October 7 attack “killing or capturing a large number of Zionist soldiers and settlers.”103 On the day of the attack, the group also posted images of captured Israeli equipment, IDs and credit cards belonging to an Israeli soldier.104

The PRC’s leader, Jamal Abu Samhadana, earlier in his militant career had gained a reputation for being a popular Fatah military leader in the Rafah area of Gaza. But despite his deep familial and personal links with Fatah, he claimed to be deeply influenced by PIJ founder Fathi Al-Shaqaqi.105 According to the Hezbollah-linked al-Mayadeen news outlet, by 1995, Samhadana was secretly working with PIJ and Hamas’ early armed formations. 106 From 2000-2004, working closely with Hamas, Samhadana founded and developed the Popular Resistance Committees (PRC). Samhadana claimed to be inspired by the success of Lebanese Hezbollah in southern Lebanon and the resulting Israeli pullout from the area in May 2000.107 The group adopted new tactics with small arms, rockets, and improvised explosive devices.108 In 2005, the PRC went so far as to gun down Yasir Arafat’s cousin Musa Arafat, a Gaza-based advisor to Mahmoud Abbas, and kidnapped his son.109 One Fatah representative told AFP the attack was “a very powerful blow to the [Palestinian] Authority.”110

It has been claimed that the PRC introduced RPG-7 type grenade launchers into the Gaza Strip.111 In 2006, the former head of Israel’s Shin Bet said Samhadana was a “criminal and a hired killer by the Hamas.”112 The PRC also worked with other Palestinian factions (particularly Hamas), resulting in the PRC, Hamas, and Jaysh al-Islam (the Army of Islam) orchestrating the June 2006 capture of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit.113 The operation would later result in Lebanese Hezbollah launching its own kidnapping operation that would trigger the 2006 Hezbollah-Israel War.114

By 2021, the PRC openly lauded its direct links to Iran, commemorating the late IRGC-QF commander Qassem Soleimani’s aid to the group in what would become known as the May 2021 Battle of the Sword of Jerusalem (Sayf al-Quds). The PRC’s military spokesman noted, “there was outside support [for the group and during the fighting], most notably the support of Hajj Qasim Suleimani.”115 Lebanese Hezbollah’s Al-Manar news outlet noted the spokesman emphasized “the Palestinian resistance relies on the Islamic Republic and Lebanese Hizballah … They are the largest and only supporters over the past decade for Gaza and the resistance.”116

Harakat al-Ahrar al-Falastinia

Another Fatah splinter group is Harakat al-Ahrar al-Falastinia (the Palestinian Freedom Movement), which was founded in Gaza in 2007 by Khaled Abu Hilal, a former Fatah leader. The group, which is also known as Fatah al-Yasir (Yasir Arafat’s Fatah), began as a more Islamist-focused oppositional element to Fatah117 with Hilal building close links to Hamas and PIJ.118 In a 2007 interview with The New York Times, he claimed that what he had created was “pure Fatah, Fatah before Oslo,” a reference to the 1993 Oslo Accords. He also railed against Fatah’s corruption and said he was pushing for stronger links with Hamas.119 By the time Hilal founded Harakat al-Ahrar al-Falastinia, he had already built up significant support among Gazan members of al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade who had issues with Fatah leadership at the time. In 2006, some 800 of the group’s members had pledged their allegiance to Hilal and voiced their approval for Hamas.120

In 2011, Hilal voiced his support for Iran and pushed for further cooperation with the Islamic Republic due to its support for the “right of Palestinian resistance.”121 In 2016, when Iran promised $30,000 for Palestinians whose homes were destroyed and $7,000 to the family of every “martyr,” the Palestinian Authority voiced its disapproval of these funds, considering them “interference.”122 Hilal responded to the PA by stating that accepting the Iranian money was as “a duty for the [Palestinian] nation and not interference.”123

Harakat al-Ahrar al-Falastinia’s military section, Kata’ib al-Ansar (the Brigade of the Supporters), also stepped up their activities with combined operations with Hamas and PIJ, in addition to their own attacks against Israeli targets.124 In May 2021, Khaled Abu Hilal resigned as secretary general of the Palestinian Freedom Movement and joined Hamas.125 It is not clear if Harakat al-Ahrar al-Falastinia played a role in the October 7 attack. Its last post on its website was on October 3, 2023.126 The group did celebrate the October 7 attacks, however. It also claimed the deaths of movement leaders as a result of Israeli airstrikes on October 9127 and another “martyr” following an Israeli strike on Khan Younis in Gaza on October 12.128

Iran’s recruitment of Fatah’s assets demonstrates that the elements of the Palestinian Authority are duplicitous, not in control of their own forces, or a mixture of both. This recruitment owed much to particular commanders’ need for a benefactor for their groups. Iran and its proxies also provided many of these factions with media assistance. The geographic isolation of Gaza, separated from other Palestinians in the West Bank, along with Hamas’ and PIJ’s dominance in Gaza served as a further exploitable elements for Tehran.i Iran’s cultivation of splinters from Fatah and its provision of funding and weapons to these groups not only strengthened PIJ’s and Hamas’ positions in Gaza and the West Bank, but also provided the Iranians with more armed proxies for its shadow war against Israel and supplied Tehran’s Palestinian allies with a further domestic pressure point against Fatah. As has been outlined, many of the Iranian-sponsored splinter sections of Fatah participated in the October 7 attacks, with elements of the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigade claiming it had launched rockets and sent fighters into Israel, possibly taking Israeli hostages.129 Their participation served as a force multiplier for Hamas and PIJ.

Part Four: Iran’s Outreach to Leftist Palestinian Groups

Due to the political threat Communism posed to the power of Iran’s Islamic Revolution, and its atheism, there is little doubt regarding Ayatollah Khomeini’s hatred of Marxism. From 1982-1983, Khomeini sought to arrest and execute communist opponents in Iran’s leftist Tudeh Party.130 In his 1989 letter to Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev, the Supreme Leader noted, “it is clear to everyone that Communism should henceforth be sought in world museums of political history.”131

However, the Islamic Republic has acted far more pragmatically vis-à-vis leftist Palestinian groups, pulling them from history’s dustbin and reestablishing them as viable proxies. The collapse of the Soviet Union combined with the onset of the 1993 Oslo Accords marked a dire time for Palestinian leftist organizations. Left without their communist benefactors, suffering from a sense of ideological failure and decades of combat and intra-political losses due to factional infighting, and held back by an aging leadership apparatus, many of these groups faced the stark choice of (re)joining Arafat’s PLO and later the Palestinian Authority, attempting to maintain some level of militancy with an extremely diminished capability to execute any attacks, or merely fading into obscurity. Iran’s attempts to acquire the loyalty of leftist groups stemmed from these weaknesses.

Regardless of the clear baseline ideological differences, there are commonalities between the Palestinian leftist groups and Iran’s modus operandi. Many of the numerous Palestinian “Popular Front”-style Marxist factions that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s were no shrinking violets when it came to violent actions and terrorist attacks. One of the earliest and most powerful organizations of the period, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) were pioneers when it came to hijacking civilian airliners and supplied fighters that countered numerous U.S. allies and moderate Arab states.132

The tactics and strategy of many Palestinian leftist groups were often in line with the notion that violence was the only way to achieve a Palestinian state.133 j This meshed well with the violent ‘Islamic Resistance’ ideology Iran pushed for its Shi`a Islamist proxies such as Lebanese Hezbollah.134 As more violent behaviors became commonplace to the Palestinian arena, there were more hardline groups from which Iran could recruit. Moreover, politically speaking, many leftist groups either vehemently opposed the 1993 Oslo Accords or maintained ambiguous stances on them. Iran and its proxies stood in opposition to the process, creating alignment on the issue. Speaking to Egypt Today in 2017, Abu Ahmed Fouad, the Damascus-based deputy director of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), stated, “The [Popular] Front [for the Liberation of Palestine] is a triangle of strength opposing the political approach represented by the powerful leadership of the Palestine Liberation Organization and the Palestinian Authority.”135 The PFLP was seen by Iran as a means to influence Palestinian affairs and as a potential counter to Palestinian Islamic Jihad and Hamas.136 The PFLP and its military section, Kata’ib al-Shahid Abu Ali Mustafa (The Martyr Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades), which advanced into Israel during the October 7 attacks137 was and is the strongest Palestinian leftist group courted by Iran.138 However, it is also important to understand the nuance of Iranian proxy-building among smaller and more overlooked leftist organizations, many of which emerged from the PFLP. This article focuses significant attention on them.

The PFLP-GC: Iran’s First Leftist Proxy

In more recent years, the late IRGC-QF commander Qassem Soleimani has been given credit by Palestinian leftist groups for the Iranian embrace of ideologically diffuse Palestinian factions. In a 2021 interview with Hezbollah’s official Al-Ahed magazine, PFLP deputy director Abu Ahmed Fouad stated that “the martyr Soleimani totally removed issues of bias when he stated, ‘We will put aside any ideological differences and share one goal, resistance to remove the cancerous entity [Israel].’”139 Soleimani was building on Iranian attempts to make progress with Palestinian leftist groups.

Iran’s first attempt to pull a Palestinian leftist group under its wing concerned the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC). Formed in 1968 by Ahmed Jibril after a split with the PFLP, the group became well known for its numerous advanced terrorist attacks.140 Jibril ruled the PFLP-GC with an iron fist until his death in 2021; splinters from his group were often killed in retribution for disloyalty.141 At the time, the PFLP-GC favored violent action and looked down on more intellectually focused endeavors, such as writing papers on leftist theory, that were swirling around many leftist Palestinian groups.142 This led the organization to pull off some audacious terrorist and guerrilla attacks in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1987, one of these attacks involved the use of two motorized hang gliders and resulted in the deaths of six Israeli soldiers. It likely served as a form of inspiration for the use of motorized hang gliders and paragliders by Hamas on October 7, 2023. In fact, on October 10, the pro-Hezbollah al-Mayadeen published an article commemorating the PFLP-GC attack.143 The use of these recreational vehicles as weapons was also adopted by elite units of the IRGC, which, for example, displayed their use in 2019.144

The PFLP-GC maintained close links to Syrian leader Hafez al-Assad and later his son Bashar al-Assad, and acted as a proxy for Syria throughout the 1970s and 1980s, particularly during intra-Palestinian fighting.145 Adam Dolnik has noted that “the group’s relationship with Syria was a key factor why Jibril never achieved the level of prominence that one might expect based on his military excellence and a touch for spectacular attacks.”146 The group’s violence against fellow Palestinian groups and willingness to bend to accommodate to the will of Syria led some Palestinian critics to brand Ahmed Jibril and the PFLP-GC as having embraced “revolutionary nihilism.”147

Beginning in the 1990s, through Lebanese Hezbollah, Iran increased its contacts with the PFLP-GC. According to Gary Gambill, “a few hundred PFLP-GC guerrillas were permitted to operate against Israel in conjunction with Hezbollah throughout the 1990s.”148 Gambill has noted that the group lacked functional command and control structures in Lebanon and was reliant on performing operations with Lebanese Hezbollah.149 Starting in 2000, the PFLP-GC began to attempt arms smuggling operations to Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza.150

In the 1990s and 2000s, several factors gave Iran opportunities to gain more influence among Palestinian leftist groups. One was Syria’s deepening links with Iran during the 1990s and 2000s. A second factor was Damascus’ dominance over the PFLP-GC and other “Popular Front” groups. A third factor was the ability of Damascus to grant Palestinian leftist groups staging areas in Syria and in the then Syrian-occupied Lebanon. Fourthly, groups such as the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), PFLP, and PFLP-GC all have their headquarters in Damascus. Writing in 1997, Harold Cubert, a chronicler of the PFLP, noted that “with its headquarters located in Damascus, and its very existence currently dependent upon Syria’s goodwill, the PFLP is in no position to carry out its strategy against Israel and the West, unless its host allows it.”151 As Iranian influence in Syria has grown since 2013 due to propping up the Assad regime, the DFLP, PFLP, and PFLP-GC have undoubtedly had to increasingly answer to and work with Tehran.152

In the case of the PFLP-GC, their powerbase was limited to a series of Palestinian camps primarily in Syria and to a lesser extent in Lebanon. In Lebanon, the heavy influence of Hezbollah allowed for further Iranian influence over the group. In Syria, the PFLP-GC has continued to act as a loyal servant of the Assad regime, acting as a proxy for both Assad and Iran against Syrian Sunni jihadi, rebel, and oppositional Palestinian groups.153 During the Syrian War, the PFLP-GC’s loyalty to Assad was deep and its violent acts against fellow Palestinians became so numerous that sections of the PFLP-GC based outside Syria and Lebanon actively opposed Jibril and his group. A former member of the group’s Gaza politburo told Al-Monitor that the PFLP-GC had performed a “deplorable and completely unacceptable act” when the organization shelled the Palestinian neighborhood of Yarmouk south of Damascus in 2012.154 Nevertheless, the PFLP-GC maintained its pro-Assad positions. And despite its unpopularity in Palestinian circles, Iran maintained its links to the group. Iran even utilized a nucleus of members from the PFLP-GC to create another pro-Assad militia group in Syria, Liwa al-Quds.155

Named after Ahmed Jibril’s son, Muhammad Jihad Jibril, who was killed in a 2002 car bombing, Kata’ib Shahid Jihad Jibril (The Martyr Jihad Jibril Brigades) became a new militant wing for the PFLP-GC in the West Bank and Gaza.156 Kata’ib Shahid Jihad Jibril subsequently claimed small arms attacks, including a 2004 shooting attack against Israelis near Hebron157 and one in 2005 against Israeli troops in Nabulus.158 Yet, these attacks were minor and representative of a group with little reach.

Kata’ib Shahid Jihad Jibril remained obscure, but by 2018 and particularly in Gaza, it was showing off new capabilities. Despite the PFLP-GC’s actions against other Palestinians in Syria and limited influence in Palestinian areas outside Lebanon and Syria, it appeared the group had not only gained new young members, but also more advanced weaponry. In November 2018, its members were photographed with a MANPADS.159 During the October 7 “al-Aqsa Flood” attacks, in which it claimed it participated, Kata’ib Shahid Jihad Jibril claimed the loss of two members.160 Given its overt links to Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, without some form of Iranian backing and Hamas and PIJ allowing it to grow, it is highly doubtful the group could have been able to produce these results organically, particularly in Gaza.k

The PFLP-GC was an obvious group for Tehran to utilize in Gaza. The Assad regime already had an high degree of control over the group, facilitating Iranian influence.161 In Lebanon, the PFLP-GC had to get acquiescence from Lebanese Hezbollah in order to pull off any military attacks against Israel.162 The group’s diehard membership, history of supporting and working with Lebanese Hezbollah, and hardcore militarism made it an attractive partner to Iran.

The DFLP: Tehran’s Other Popular Front

Originally founded as the Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine in 1969, the DFLP resulted from a split from its fellow leftist group the PFLP. Led by Jordanian-Palestinian Christian Nayef Hawatmeh, the small group earned an early reputation for a strong communist intellectual base.163 According to Jillian Becker, the DFLP had “especially close ties with the Soviet Union.”164 The DFLP often acted as a go-between for radical leftist groups and the Fatah-dominated PLO. The group carried out a number of deadly attacks, including the 1974 Ma’alot Massacre in which over 20 school children were killed.165 However, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, negotiations between the PLO and Israel, and eventually with Yasir Arafat’s signing of the 1993 Oslo Accords, the DFLP ran into hard times.

Due to increasing PLO negotiations with Israel and then the Oslo Accords, an internal split led by Yasir Abd Rabo (Abu Bashar) took more of the DFLP’s followers away from Hawatmeh’s camp.166 In 1993, the DFLP rejected the Oslo Accords and wavered in its support for PLO chairman Yasir Arafat.167 By the late 1990s, the DFLP was floundering. It continued some violent attacks through the 2000s, but they were piecemeal, hardly comparable to successful terrorist attacks launched by Palestinian rivals, and unrepresentative of the group’s capabilities during its height in the 1970s.168

However, by the 2010s, the group was in increasing contact with Iran and its proxies. In 2011, the DFLP’s 11th congress was held in Beirut and included a speech by Lebanese Hezbollah parliamentarian Nawaf al-Musawi.169 During al-Musawi’s speech, it was reported that he “stressed the need for the Palestinian factions to overcome their political differences, so that they could be [better] able to confront the Israeli aggression.”170 Meetings, events, and other forms of coordination with Lebanese Hezbollah persisted. In 2013, Lebanese Hezbollah utilized the DFLP to assist in distributing food to Palestinian refugees displaced from fighting in Syria. This particular initiative backfired. Given many of the refugees had just seen their neighborhoods destroyed by pro-Assad forces, they burned the food in protest against the gesture from Lebanese Hezbollah.171

In 2012, the DFLP attempted to maintain a position similar to that of PIJ regarding the fighting in Syria. In conjunction with Fatah and the small Jabhat al-Nidal al-Sha’abi al-Falastini [Palestinian Popular Struggle Front], the DFLP pushed for neutrality for Palestinians living in Syria.172 While there were no reports of the DFLP taking part in fighting on either side of the Syrian War, the group did maintain a relatively pro-Assad stance. In 2021, Nayef Hawatmeh even offered his congratulations to Bashar al-Assad when he was re-elected to his position as president.173 Meetings between the DFLP and Lebanese Hezbollah also continued well into 2023, with a DFLP delegation congratulating Lebanese Hezbollah in July of that year for its “July victory,” a reference to the 2006 Hezbollah-Israel War, saying it was part of the “path to Palestinian victory and liberation.”174

The most dynamic portion of DFLP-Iranian cooperation took place in the Gaza Strip. Established in 2000, the DFLP’s armed section known as Kata’ib al-Muqawama al-Wataniyah – Quwet al-Shahid Umar al-Qasim (The National Resistance Brigades – Martyr Umar al-Qasim Forces), or KMW, has offered one of the clearest examples of Iranian influence within the DFLP. Initially formed around cellular structures in the West Bank and Gaza,175 with Iranian assistance, the KMW was reformed into a more cohesive armed structure and slightly rebranded with a more modern facade.176

By 2019, the DFLP’s KMW was sporting new capabilities in Gaza. In one parade, the group demonstrated it had access to MANPADS, possibly of Iranian origin.l In 2021, the DFLP posted photos of the group’s fighters using the Iranian-made AM-50 .50 caliber anti-material rifle.177 KMW also likely received assistance from Iran related to its media profile, launching a Telegram channel in 2019 for more advanced media propaganda. Signs of Iranian influence could even be spotted in the type of music used in propaganda videos.178 m From 2019-2022, the group claimed more armed activity, particularly via the use of mortars and rocket munitions.179 These activities would also include other Iranian proxies. In May 2022, the group claimed a joint operation that included the PIJ and al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade in Gaza.180

Moreover, the DFLP publicized its role of maintaining loyalty to the Iranians. The January 3, 2020, death of IRGC-QF commander Qassem Soleimani was memorialized on their social media. The group posited that Soleimani’s death would “only increase our determination to follow the same path of [that] martyr commander.”181 Around two weeks later, the DFLP posted material that sent slightly more subtle signs of loyalty to Tehran. During a January 2020 ceremony to honor a freed Palestinian prisoner, Alaa Abu Jazar, the event was replete with DFLP members posing with weapons in front of “martyrdom” posters devoted to members of Harakat Sabireen.182

It was the military rather than political wings of Palestinian leftist groups such as DFLP that received makeovers and increased support. From access to newer small arms to heavier weapons and new alliances with more powerful groups in Gaza, the DFLP’s KMW displayed them with gusto. Nevertheless, the DFLP’s political wing, particularly via social media, did not receive the same attention from Iran, appearing to still use old messaging techniques and lacking the flashy imagery, uniforms, and attention allotted to KMW.

Part Five: Tehran’s Strategy of Crafting Unity and Coherence Through Umbrella Groups and Joint Operations Rooms

Umbrella groups and joint operations rooms have been a regular feature within the Palestinian arena for decades and were regularly crafted by various Palestinian actors.n In fact, the PLO itself operated as an umbrella group. Some had shorter lifespans than others. In more recent times, umbrella groups containing outfits part of Iran’s Palestinian proxy network in Gaza, point to some level of Iranian influence and direction. Iran has regularly demonstrated a desire to craft umbrellas for its proxies to organize ideologically and religiously different groups it exerts various levels of control over.

Not all umbrella type groupings and organizations crafted by Tehran are equal, but the end effect of them tends to be demonstration of Iranian management, control, and better armed organization for the groups included within them. The patronage supplied by Iran and its more loyal proxies have stood as a symbol to other groups that it would not only be in their interest to fight under Iranian direction, but that this would offer a better prospect of political and military success.

Before discussing Iran’s use of umbrellas in the Palestinian context, it is useful to discuss Tehran’s previous use of this strategy in other locations. In 1997, Lebanese Hezbollah created the Lebanese Resistance Brigades (Saraya al-Muqawama al-Lubnaniya), a non-sectarian militia auxiliary to Lebanese Hezbollah’s main Shi`a-staffed forces. Its purpose also extended to becoming a middleman between Lebanese Hezbollah and by extension Iran, and other anti-Israel armed groups in Lebanon. According to Chris Zambelis, the group would “forge operational ties with non-Islamist militias that subscribe to a host of different ideologies but nevertheless act under the rubric of resistance. This includes militants that promulgate secular, nationalist, socialist, and leftist ideologies.”183

While the Lebanese Resistance Brigades was not necessarily an umbrella group itself, it allowed Hezbollah to craft informalized umbrella structures with groups that held their own ideologies and levels of autonomy. As a partial result of these networking advances, in May 2008, when Lebanese Hezbollah’s telecom network was threatened with closure by Lebanese authorities, primarily from parties opposed to Hezbollah, Hezbollah not only mobilized sectarian allies such as Harakat Amal, but also secular groups such as the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP). These groups then stormed into Beirut.184 In 2013, units from the SSNP coordinated with and fought alongside Lebanese Hezbollah and Iraqi Shi`a militias in Syria. The relationship deepened to such a degree that the secular SSNP adopted the sectarian rhetoric of Lebanese Hezbollah.185

In Iraq, the Popular Mobilization Forces (al-Hashd al-Sha’abi) serves as another example for Iranian umbrella network construction. According to one former al-Hashd al-Sha’abi commander, Iran’s thinking was that tensions between different groups could be controlled, defused, and utilized by Iran with the “correct loyal men” leading the organization.186 Since the 2014 formation of al-Hashd al-Sha’abi in Iraq, it has been overwhelmingly dominated by Iranian-backed Shi`a militia groups and commanders.187 Yet, Hashd al-Sha’abi also included members that were loyal to factions that clashed with Iranian interests and ideology.188 o

As already noted, extremely loyal groups to Iran, such as the Badr Organization, make up the largest contingent of al-Hashd al-Sha’abi’s forces. Many commanders of al-Hashd al-Sha’abi arose from the ranks of another loyal Iranian proxy group, Kata’ib Hezbollah.189 Over time, some Hashd al-Sha’abi groups were dropped by the Iranians over issues ranging from loyalty, potential unacceptable levels of criminality, or because they had openly opposed Iran.190 The Hashd al-Sha’abi promoted pro-Iranian messaging and heavily promoted factions more loyal to Iran.191 This demonstrated Iran’s influence over various Shi`a militias and its ability to build a core of effective partners within different factions.

Turning to the Palestinian context, in the hopes of crafting various Fatah-splinter, leftist, and Islamist groups into a more loyal, militarily cohesive, and politically responsive network, it was in Iran’s interest to form new umbrellas for its ideologically heterodox web of Palestinian proxies. One early example includes the Ten Resistance Organization, created in 1991 at the Iranian-run World Conference in Support of the Islamic Revolution in Palestine.192 Hamas and leftist Palestinian groups created the umbrella group as a protest against negotiations between Israel and the PLO.193

In September 2023, Hamas and PIJ also started a joint operations room in Beirut. According to the official Iranian Islamic Republic News Agency, Iran’s foreign minister praised the group and “underlined the need for unity among all the Palestinian groups.”194

Another joint operations room, which was functional by 2021, primarily included Lebanese Hezbollah and Hamas.195 This joint operations room utilized Lebanese Hezbollah as a coordinator between Iran, other Iranian proxies in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, and the Palestinian groups.196 Ibrahim al-Amin, a writer with the pro-Hezbollah Al-Akhbar, told Hezbollah’s Al-Manar that in 2021 Beirut-based joint operations room included Palestinian factions other than Hamas, utilized Hezbollah to smuggle Hamas field operatives in Gaza to Beirut, and that IRGC-QF commander Ismail Qaani made two visits to the group’s offices during the two weeks of fighting between Palestinian forces in Gaza and the West Bank in May of that year.197

Iran’s main Palestinian umbrella project grew wings in Gaza and the West Bank has been the Joint Operation Room for the Palestinian Factions of Resistance (al-Ghurfa al-Mushtrakat li-Fasa’il al-Muqawama al-Falistinia, or JOR). Initially, the JOR began as a partnership between Hamas and PIJ in 2006.198 Ten other armed organizations including Islamist Fatah splinters and leftist groups were added to the umbrella JOR grouping between January 2017 and July 2018.p In November 2018, Yahya al-Sinwar, Hamas’ Gaza lead and prominent military commander, referred to the JOR as a body that would form the “nucleus of the army of liberation.”199 By December 2018, the PFLP, particularly through its Abu Ali al-Mustafa Brigades, also began deferring to the JOR for how it would execute armed decision-making.200 The JOR reared its head in a more militant fashion with rocket attacks against Israeli targets in November 2018201 and a round of rocket attacks from Gaza in 2019.202 New marketing material, including iconography, propaganda, and promotional material, was also displayed by the JOR starting in 2020.203

All of the groups involved with the JOR had high levels of Iranian backing and were ostensibly marketed as a more unified force. “With the strength of God, we fight together and [will] win together,” a December 2020 communique by JOR read.204 In December 2020, JOR announced a new series of armed exercises “to enhance cooperation and joint actions … [to] permanently and continuously raise their combat readiness.”205 JOR posted highly polished propaganda surrounding the exercises that included launching rockets, simulating taking an IDF hostage from a tank, raiding small structures, deploying what was likely an Iranian-made Misagh MANPADS, and using an Iranian-made AM 50.206 In other videos from the drill, combat divers simulated raiding coastal targets and JOR fighters interdicted mock Israeli seaborn forces.207 All of these tactics were later utilized in the October 7 attacks. Citing Hamas, the analyst Joe Truzman noted the training operation was “the first of its kind and is an effort to ready Palestinian militant groups against a potential military conflict against Israel.”208 Much of the propaganda and statements produced for the JOR followed models that utilized filming, graphics, and even text used by Iran that had also been used for other regional Iranian proxies.209 q

Following the May 2023 clashes involving the JOR and Israel, IRGC-QF commander Ismail Qaani singled out the JOR with special greetings to the umbrella group, adding that their operations “proved once again that by relying on almighty God, firm determination, and wise management, [these forces were] capable of breaking the enemy’s power.”210 In a form mirroring earlier unveilings of newly minted Iranian proxies,r Iranian and other proxy/proxy-supporting publications granted the JOR regular coverage and high praise.211 Yet, by September 2023, a month before the so-called Al-Aqsa Flood operations, the JOR seemed to cease activity. No posts emerged from its Telegram, and coverage withered. It is possible this was for reasons of operational security or for other reasons relating to the impending October 7 attack. Almost all the constituent groups of the JOR assisted in the attacks from Gaza into Israel in October and did so in a mutually supportive manner.s It remains to be seen whether the JOR will be revived in the coming months.

Conclusion

It is possible that Iran was surprised by the catastrophic success of the October 7 attacks. Tehran may not have expected the attacks to have dealt as deadly a blow to Israel as they did. However, there is little doubt that Iran’s financial aid, structuring of its proxies into more cohesive armed factions and then into umbrella organizations, and assistance through the supply of weapons increased the deadliness and extremism of its Palestinian proxies. It is also quite clear that without Iranian assistance and nurturing, these groups would not have been in a position to strike Israel, as they did on October 7 with as much success as they showed.

Armed capabilities supplied by Iran, such as a variety of UAV designs, rockets, demolition charges, and other munitions, were smuggled into Gaza and used to deadly effect in the October 7 attack in which Israeli vehicles, buildings, civilian houses, and observation posts were all targeted.212 Iranian assistance allowed its Palestinian proxies to amass the firepower, messaging know-how, and much of the hi-tech equipment necessary to carry out and propagandize the attack. Financial aid provided by Iran did more than keep Hamas operating as a governing body in Gaza; it was also directly piped into Hamas’ terror and military apparatus.213

Training provided to Hamas fighters and the other proxies also honed their abilities to execute the October 7 attacks. As PFLP-GC secretary general Talal Naji told Iran’s al-Alam in August 2021, “Sometimes the training took place in the Islamic Republic of Iran, sometimes in Syria, and sometimes in Lebanon with the brothers in Hezbollah who are waging jihad.” While it is currently unknown how Hamas or fighters from other groups traveled to Iran, Lebanon, and Syria, it can be assumed to be via the wide network of Gaza’s smuggling tunnels,214 by sea,t or from flights Gazans could take originating outside of Israel.215

Naji also stressed that “as you know, we are an axis, an axis of resistance. [IRGC-QF commander Qassem Soleimani] used to supervise himself,” adding that Iranian-supplied weapons, such as the Russian-made laser-guided Kornet anti-tank missile, strengthened their capabilities.216 u

Iran allows for a level of autonomy among its proxies, but as this article has outlined, Tehran has moved to punish insufficiently obedient groups, allowing them to wither on the vine, or has engineered splinters to weaken them or pressure them into line.

Hamas’ takeover of Gaza served as the means for Iran to absorb splintered factions of Fatah into its orbit. Even if those factions could not be fully controlled, creating a reliance on Iran’s weapons, money, and other forms of political support facilitated their reformation into Iran’s umbrella. By cultivating ties with militant factions with differences with Abbas’ Fatah, Iran was able to recruit manpower to its “Axis of Resistance” and create a pressure point within Fatah. Furthermore, the continued presence of Fatah splinter fighters in Gaza has given Iran leverage to ensure the obedience of Hamas and PIJ. Small and less popular groups such as the PFLP, PFLP-GC, and DFLP were cultivated by Iran as part of a larger umbrella of Tehran-aligned groups, but likely simultaneously served other roles, including countering the Palestinian Authority and if necessary to put pressure on Hamas and PIJ.

As the Israeli offensive continues in Gaza, it is possible some armed Palestinian groups may be forced to shift their center of gravity to Lebanon. This would expose them to even deeper Iranian influence. On December 4, 2023, Hamas’ Lebanon section released a statement calling for the creation and recruitment for the Vanguards of the al-Aqsa Flood (Taliy’ah Tufan al-Aqsa), a group focused on “resisting [Israeli] occupation.”217 Given any armed activities by Hamas in Lebanon would have to be coordinated with Lebanese Hezbollah, these activities would also be subject to a degree of control by the Iranian decision makers that exert influence over Hezbollah. As previously seen with the PFLP, DFLP, and PFLP-GC, groups dependent on using Lebanon or Syria as staging areas have only become more beholden to their masters in Damascus or Tehran.

Even if Hamas and PIJ are militarily defeated in Gaza in the months ahead, Iran would still have many options to work with in both Gaza and the West Bank. As Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer stated in an October 31 piece, “The war is radicalizing far more Palestinians than Hamas propaganda ever could.”218 Iran will likely attempt to rebuild its network in Gaza from newly radicalized Palestinians, including among leftist actors, Islamists, and smaller factions they can more strongly control.

In this scenario, it should be expected that Iran will also continue to splinter off groups from Fatah/the Palestinian Authority. On November 5, a mysterious group claiming to represent members within the Palestinian Authority-affiliated security services emerged. Called the Sons of Abu Jandal, the group demanded that Mahmoud Abbas and the PA security forces engage in violence against Israel or revolt against Abbas.219 While no link to Iran has yet been established and the group has since gone quiet, it is these types of splinters that have been exploited by Tehran in the past.

In the months ahead, it is likely that Iran will continue to use the carrots (e.g., funding) and sticks (e.g., fostering splinter groups) in order to maintain and deepen control over its Palestinian “Axis of Resistance.” As Israel’s military campaign in Gaza puts these groups under increasing pressure, Iran’s leverage will only grow. Given Iran has aimed to provide support to a wide range of new and well-established groups, particularly those with more violent dispositions, the radicalizing effect of the war on Palestinians provides fertile terrain for Tehran. CTC

Phillip Smyth specializes in Iranian proxy organizations and Shi`a militia groups. He was formerly a Soref Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and researcher at the University of Maryland. Hizballah Cavalcade, his blog on Jihadoloy.net, tracked Iran-backed Shi`a militias across the Middle East, including in Bahrain, Iraq, and Syria. X: @PhillipSmyth

© 2023 Phillip Smyth

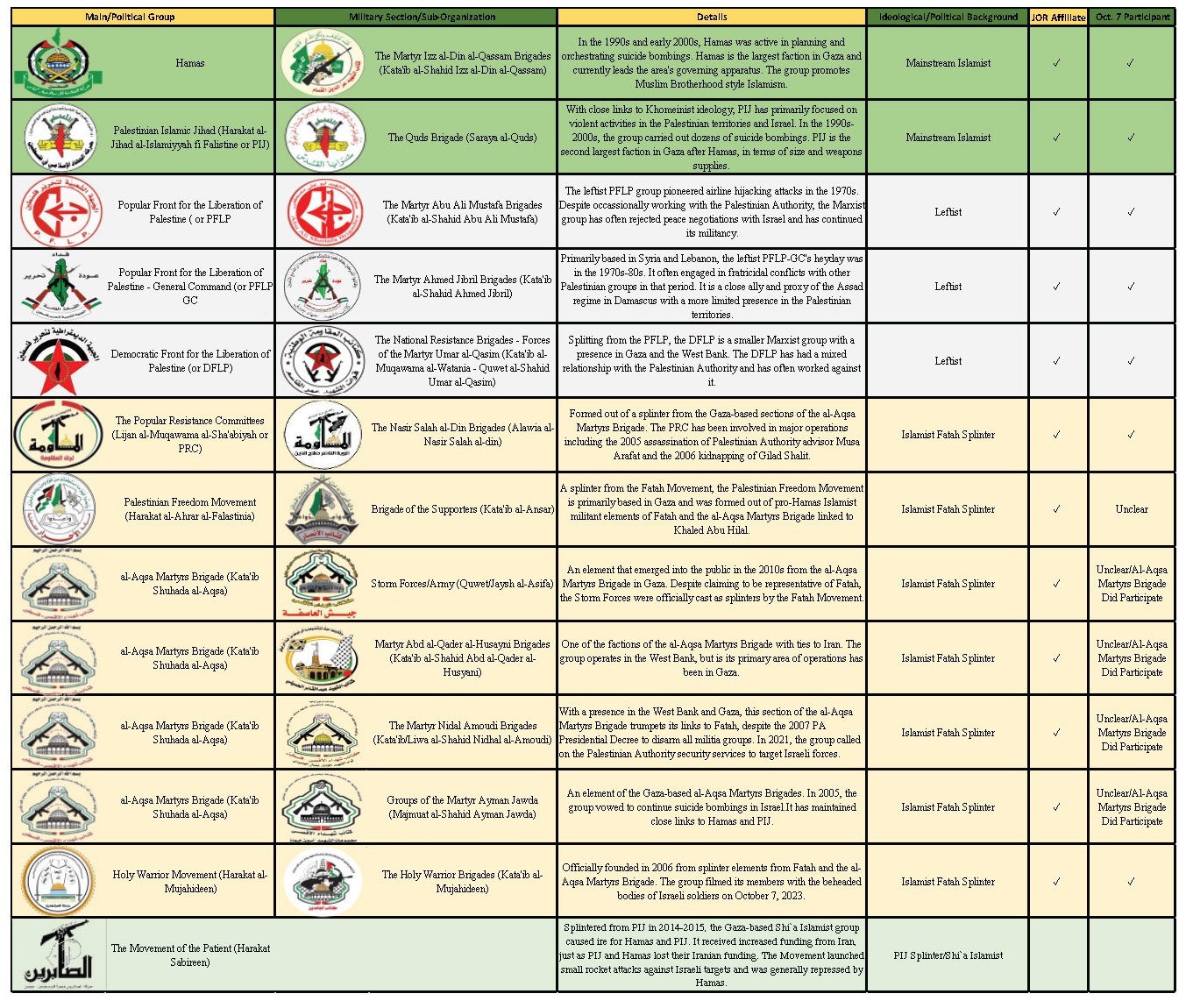

Appendix: Iran-Backed Palestinian Organizations

Color Key

Green: Main Islamist organizations (2)

Gray: Leftist groups (3)

Yellow: Islamist Fatah splinters (7)

Light Green: PIJ splinter/Shi`a Islamist (1)

Substantive Notes

[a] Hamas claimed it launched 5,000 rockets. See “Why the Palestinian group Hamas launched an attack on Israel? All to know,” Al Jazeera, October 7, 2023.

[b] It is important to note that following AAH’s use of reportedly unapproved front groups to attack U.S. interests, Harakat Hizballah al-Nujaba leader Akram Kaabi was publicly utilized as a means to demonstrate overall Iranian control. In December 2021, Kaabi posed in front of flags belonging to a multitude of the established front groups and behaved as a spokesman for them, signifying he—and by extension, Iran—was in control of all elements. See al-Muqawama al-Islamiyyah Harakat al-Nujaba, Telegram, December 9, 2021.

[c] The Bus 405 suicide attack (albeit, not a bombing) is considered “the first Palestinian suicide attack, despite the fact that … [the perpetrator] survived.” It was launched by Palestinian Islamic Jihad in September 1989. From 2000-2005, Both Hamas and PIJ were also responsible for 65.5 percent of suicide bombings by Palestinian groups. See Efraim Benmelech and Claude Berrebi, “Attack Assignments in Terror Organizations and The Productivity of Suicide Bombers,” Working Paper 12910, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2007, pp. 5-7.

[d] This is term is used, often pejoratively, to describe ultra-hardline Islamist extremists who regard those who do not follow their approach as guilty of apostacy and deserving of death.

[e] The sectarian nature of the war in Syria and increased Iranian Shi`a proselytizing in Gaza became major issues for Hamas. In 2011, Hamas was attempting to maintain links with Tehran and more quietly deal with Iranian proselytizing. See “Shiite Militancy Makes Inroads in Sunni Gaza,” Jamestown Foundation, Terrorism Monitor 8:24 (2011). In January 2012, Hamas attacked Gaza’s small community of Shi`a Muslims. See Avi Issacharoff, “Hamas Brutally Assaults Shi’ite Worshippers in Gaza,” Haaretz, January 17, 2012. In June 2013, a salafi mob, in part inspired by Muslim Brotherhood-encouraged anti-Shi`a sectarianism, led to the lynching of Shaykh Hassan Shehata and three other Egyptian Shi`a. See “Egypt: Lynching of Shia Follows Months of Hate Speech,” Human Rights Watch, June 27, 2013. In turn, Shehata’s death was used as a recruitment tool by Iranian Shi`a militias for Syria. See Phillip Smyth, “Liwa’a ‘Ammar Ibn Yasir: A New Shia Militia Operating in Aleppo, Syria,” Hizballah Cavalcade, Jihadology, July 20, 2013.

[f] Harakat Sabireen incorporated a mix of Sunni and primarily Iranian Shi`a Islamist ideology into its structure. Harakat Sabireen founder Hisham Salem is a Shi`a religious shaykh and was originally a commander within the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. His early networks that eventually grew into Harakat Sabireen included extensive support from Iranian-linked Shi`a charities and his Harakat Sabireen membership has included former PIJ members who converted to Shi`a Islam. Avi Issacharoff, “Hamas, beholden to Iran, lets Shiite group operate in Gaza,” Times of Israel, May 12, 2015; author conversations, Iranian-backed Iraqi Shi`a militia commander, August-September 2019; Hassan Abbas, “Al-Sabireen: an Iran-Backed Palestinian Movement in the Style of Hezbollah,” March 14, 2018; Salah Qashta, “‘al-Sabireen’ ..al-halif al-falastini al-awal li-airan ‘ala qa’ima al-irhab al-amrikani,” Irfaa Sawtak, February 2, 2018.

[g] One example is Iran’s shipment of tons of arms to Yasir Arafat-controlled elements of the PLO via the Karine A cargo ship in 2002. Robert Satloff, “The Peace Process at Sea: The Karine-A Affair and the War on Terrorism,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, May 1, 2002.

[h] While the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade subunit could not be identified, the kidnapper’s headband included, “Liwa” or brigade. This may point to a link to Liwa al-Shahid Nidhal al-Amoudi.

[i] It is important to note that in 2015, Jaysh al-Asifa’s head noted that it was “not easy for the fighters of Fatah to carry weapons in the Gaza Strip after the Hamas movement took over.” See Amar Abu Shebaab, “Qa’id jaysh al-’asifa li ‘raya’: tawhid miqatli fatah lays ‘asira w al-’alaqa mah al-qassam taybeh,” Raya, April 20, 2014.

[j] It should be noted that the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), a violent splinter from the PFLP, was considered more moderate than its other “Popular Front” cohorts. In the 1970s, when most groups adopted the “Rejectionist” approach to achieve the full destruction of the State of Israel, the DFLP posited that a unilateral declaration of a Palestinian state on any amount of “liberated land” (through armed conflict or negotiations) was a preferrable option. For the DFLP, this territory could serve as a springboard for the future “liberation of Palestine.” See Muhammad Y. Muslih, “Moderates and Rejectionists within the Palestine Liberation Organization,” Middle East Journal 30:2 (1976), pp. 127-128.

[k] The PFLP-GC had already suffered splits inside the Palestinian Territories due to issues some members had with its actions during the Syrian Civil War. In fact, in Syria, the PFLP-GC suffered a split that resulted in some fighters forming the short-lived Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-Free Command. See “27 2 Damascus Ugarit dimashq, i’alan tashkil al-jebha al-sha’abia al-tahrir falastin al-qa’ida al-hurr al-mishaqa ‘an jebha ahmed Jibril,” Ugarit News, YouTube, February 27, 2013.

[l] The MANPADS in the photo appears to be an SA-7 Strela-type system. If Iranian, it is likely a Misagh-type MANPADS. KMW’s official Telegram channel, Telegram, December 13, 2019.

[m] The background instrumental music is a song called “Ya Wa’ad Allah” by Lebanese Hezbollah band Firqat al-Fajr and was released after the 2006 Hezbollah-Israel War. Different versions (including instrumental styles) have been used by various Iranian supported groups. See “Ya Wa3d Allah … New Version YA-Lubnan.com,” Daily Motion, 2008. In Bahrain, the song was used by Iranian-backed Bahraini militants and another version was made for Iraq’s Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. See Phillip Smyth, “Singing Hizballah’s Tune In Manama: Why Are Bahrain’s Militants Using the Music of Iran’s Proxies?” Hizballah Cavalcade, Jihadology, May 5, 2014.

[n] One example is the 2021 “Joint Operations Room.” See Adnan Abu Amar, “Ghurfa al-’amliat al-mushtarkat lilmuqawama fi gaza nuwat li ‘jaysh al-tahrir,’” Al Jazeera, May 28, 2021.

[o] A number of these groups later broke off. Muqtada al-Sadr’s Saraya al-Salam began operating with the Iraqi Ministry of Defense, and many factions loyal to Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani formed their own network in 2020. See Suadad al-Salhy, “Iran and Najaf struggle for control over Hashd al-Shaabi after Muhandis’s killing,” Middle East Eye, February 16, 2020.

[p] Hamas’ Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades; PIJ’s al-Quds Brigades; the PFLP’s Martyr Abu Ali al-Mustafa Brigades; the DFLP’s KMW; the PFLP-GC’s Martyr Jihad Jibril Brigades; the Palestinian Freedom Movement’s Brigade of the Supporters; the Popular Resistance Committee’s Nasir Salah al-Din Brigades; the Palestine Mujahideen Movement’s Mujahideen Brigade; Fatah-splinter/Al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigade’s Groups of the Martyr Ayman Jawda; The Martyr Nidal Amoudi Brigade; Martyr Abd al-Qader al-Husayni Brigades; and Storm Army.

[q] Similar markers can be seen with videos produced for the Iranian-backed Iraqi front group Saraya Thawrat al-Ashreen al-Thania. See Saraya Thawrat al-Ashreen al-Thania official Telegram Channel, Telegram, July 5, 2020. JOR statements also match a model used by the Iranian-backed Bahraini group Saraya al-Mukhtar: JOR official Telegram channel, Telegram, May 10, 2021, and Saraya al-Mukhtar Official Telegram Channel, Telegram, Telegram, February 20, 2017. At times, even the same fonts were utilized in these posts.

[r] When Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and Kata’ib Hezbollah’s first videos of attacks on U.S. forces were released from 2005-2007, Lebanese Hezbollah’s Al-Manar was often the first to run them or run them as exclusives. Author observation. See also “Iraqi shia resistance:asaeb ahlu alhaq,” archive.org, April 11, 2008.

[s] While it is unclear whether Harakat al-Ahrar al-Falastinia participated and which specific Gaza-based factions of al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade were involved, all of the other elements of the JOR have claimed roles in the October 7, 2023, attack. (See Figure 1.)

[t] In one 2013 case, smugglers brought in a dismantled Hyundai Sonata from Egypt into Gaza. “Hamas polices seas as tunnel smuggling suffers,” Reuters, November 11, 2013.

[u] The missiles were also used on the first day of the curent Gaza war. See Seth J. Frantzman, “Overwhelmed: The IDF’s first hours fighting the terror waves on Oct 7,” Jerusalem Post, October 16, 2023. Hamas has since claimed the use of the weapon against Israeli soldiers. See Iran Observer, “Hamas released a footage of the Kornet missile hitting the Israeli APC …,” X, October 28, 2023.

Citations

[1] Bill Hutchinson, “Israel-Hamas conflict: Timeline and key developments,” ABC News, October 18, 2023.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Stephen Sorace, “Israeli Navy unit repels Hamas terrorists infiltrating by sea on morning of attack, IDF video shows,” Fox News, October 16, 2023; Abdelali Ragad, Richard Irvine-Brown, Benedict Garman and Sean Seddon, “How Hamas built a force to attack Israel on 7 October,” BBC, November 27, 2023.

[4] “Israel-Hamas war live updates: 2 hostages released by Hamas are American Israeli citizens,” NBC News, October 20, 2023; Cassadra Vinograd and Isabel Kershner, “Israel’s Attackers Took More Than 200 Hostages. Here’s What We Know About Them,” New York Times, October 24, 2023; “Israel revises death toll from Oct. 7 Hamas assault, dropping it from 1,400 to 1,200,” Times of Israel, November 11, 2023; Cassandra Vinograd and Isabel Kershner, “Israel’s Attackers Took About 240 Hostages. Here’s What to Know About Them,” New York Times, November 20, 2023.

[5] “Israeli forensic teams describe signs of torture, abuse,” Reuters, October 15, 2023; “Images of the Mass Kidnapping of Israelis by Hamas,” Atlantic, October 9, 2023; Georgina Lee, “What is a war crime and did Hamas commit war crimes in its attack on Israel?” Channel 4, October 11, 2023.

[6] Armin Rosen, “How Hamas Fooled the Experts,” Tablet Magazine, October 12, 2023.

[7] “Imam Khomeini Exposed Israeli Crimes,” International Affairs Department, Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini’s Works, May 9, 2014.

[8] James M. Markham, “Arafat, in Iran, Reports Khomeini Pledges Aid for Victory Over Israeli,” New York Times, February 19, 1979.

[9] Jonathan C. Ral, “PLO Chief, in Iran, Hails Shah’s Fall,” Washington Post, February 19, 1979.

[10] Amir Vahdat and Jon Gambrell, “Iran leader says Israel a ‘cancerous tumor’ to be destroyed,” Associated Press, May 22, 2020.

[11] Jennifer Maddocks, “Israel – Hamas 2023 Symposium – Iran’s Responsibility for the Attack on Israel,” Lieber Institute, West Point, October 20, 2023; Summer Said, Benoit Faucon, and Stephen Kalin, “Iran Helped Plot Attack on Israel Over Several Weeks,” Wall Street Journal, October 8, 2023; Dan De Luce and Ken Dilanian, “U.S. intelligence indicates Iranian leaders were surprised by Hamas attack,” NBC News, October, 11, 2023; Warren P. Strobel and Michael R. Gordon, “Iran Knew Hamas Was Planning Attacks, but Not Timing or Scale, U.S. Says,” Wall Street Journal, October 11, 2023; Katie Bo Lillis, “US intelligence currently assesses Iran and its proxies are seeking to avoid a wider war with Israel,” CNN, November 2, 2023; “President Joe Biden: The 2023 60 Minutes interview transcript,” 60 Minutes, October 15, 2023.

[12] “Iran’s Khamenei lauds Hamas attack on Israel, again denies involvement,” Times of Israel, October 10, 2023.

[13] Jack Khoury and Reuters, “Hezbollah’s Nasrallah Praises ‘Heroic’ Oct 7 Hamas Attack, Says It Was ‘100% Palestinian,’” Haaretz, November 3, 2023.

[14] “Kalimat al-sayyid hassan nasrallah khalal al-ahatifal al-takrimi lishuhada ‘ala tariq al-quds,“ Spot Shot Video, YouTube, November 3, 2023.

[15] “Treasury Designates Hizballah Commander Responsible for American Deaths in Iraq,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 19, 2012.

[16] Scott Glover, Curt Devine, Majlie de Puy Kamp, and Scott Bronstein, “‘They’re opportunistic and adaptive’: How Hamas is using cryptocurrency to raise funds,” CNN, October 12, 2023.

[17] Michael Evans, “How Iran’s tech and homemade weapons gave Hamas power to strike Israel,” The Times (London), October 11, 2023; Fabian Hinz, “Iran Transfers Rockets to Palestinian Groups,” Wilson Center, May 19, 2021; Nakissa Jahanbani, Muhammad Najjar, Benjamin Johnson, Caleb Benjamin, and Muhammad al-`Ubaydi, “Iranian Drone Proliferation is Scaling Up and Turning More Lethal,” War on the Rocks, September 9, 2023.

[18] Yonah Jeremy Bob, “Iran-Hezbollah help Hamas, Islamic Jihad trounce Israel with propaganda – exclusive,” Jerusalem Post, December 6, 2021.

[19] Nancy Ezzeddine and Hamidreza Azizi, “Iran’s Increasingly Decentralized Axis of Resistance,” War on the Rocks, July 14, 2022.

[20] Colin Clarke and Phillip Smyth, “The Implications of Iran’s Expanding Shi`a Foreign Fighter Network,” CTC Sentinel 10:10 (2017).

[21] “Al-Sadr vows to defend Iran,” Al Jazeera, January 22, 2006.

[22] John Davison and Ahmed Rasheed, “Rift between Tehran and Shi’ite cleric fuels instability in Iraq,” Reuters, August 23, 2022.

[23] Sam Wyer, “The Resurgence of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq,” Institute for the Study of War, December 2012.

[24] “The Qayis al-Khazali Papers,” American Enterprise Institute, August 2018; Bryce Loidolt, “Iranian Resources and Shi`a Militant Cohesion: Insights from the Khazali Papers,” CTC Sentinel 12:1 (2019).

[25] “Tactical Interrogation Report 1,” Khazali Files, American Enterprise Institute, March 21, 2007.

[26] “Tactical Interrogation Report 4,” Khazali Files, American Enterprise Institute, March 26, 2007.

[27] “Tactical Interrogation Report 11,” Khazali Files, American Enterprise Institute, March 26, 2007.

[28] Phillip Smyth, “Iranian Militias in Iraq’s Parliament: Political Outcomes and U.S. Response,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, June 11, 2018.

[29] Author conversations, Iran-backed Iraqi Shi`a militia group leaders and members, August 2012-June 2013.

[30] Author conversations, Iran-backed Iraqi Shi`a militia group leaders and members, August 2012-June 2013; author conversation, Shi`a militia commander (from a Sadrist splinter group fighting in Syria and Iraq), April 2018; author conversation, Auws al-Khafaji, December 2019. Khafaji is the leader of Quwet Abu Fadl al-Abbas. He was a leading figure in al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army, running afoul of him in 2012. Khafaji later deployed forces to Syria from 2012-2015.

[31] Matthew Levitt and Phillip Smyth, “Kataib al-Imam Ali: Portrait of an Iraqi Shiite Militant Group Fighting ISIS,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, January 5, 2015.

[32] Phillip Smyth, “Making Sense of Iraq’s PMF Arrests,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, April 26, 2019.

[33] “Iraq chaos as al-Sadr supporters storm Green Zone after he quits,” Al Jazeera, August 29, 2022; Firas Elias, “Deciphering Muqtada al-Sadr’s Decision to Shut Down Saraya al-Salam,” Emirates Policy Center, November 21, 2021.

[34] “Tashiya ahd ‘anasr kata’ib sayyid al-shuhada fi al-basra alathi saqat fi suriya,” National Iraqi News Agency, May 6, 2013.