Abstract: The May 17, 2024, Ulu Tiram attack in Malaysia offers a nuanced case study of radicalization, revealing the complex psychological and ideological mechanisms that transform individual belief systems into potential vectors of religious extremism. Initially misattributed to Jemaah Islamiyah but later described as an Islamic State attack, the incident is more accurately classified as a Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD)-influenced incident. The tragedy illuminates how an isolated familial environment, driven by a fanatical father’s extreme religious ideology, systematically groomed the attacker through a distorted theological narrative that reframed violence as a spiritual purification ritual and pathway to salvation. By examining the attacker’s background through a JAD-specific lens, this analysis transcends conventional interpretations of Islamic State support by demonstrating how self-imposed ideological exiles can create significant challenges for monitoring and intervention, thus underscoring the urgent need for sophisticated approaches that move beyond simplistic categorizations of terrorist sympathizers.

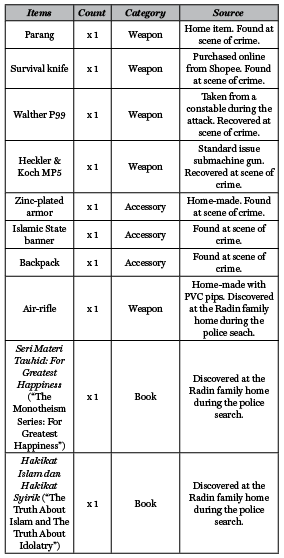

In the early hours of May 17, 2024, at approximately 2:45 A.M., 20-year-old Radin Luqman bin Radin Imran stormed into the Ulu Tiram police station in Johore, the southernmost state of Peninsular Malaysia.1 Wearing a dark mask with the Islamic State’s black banner draped over his shoulder, Luqman assaulted two on-duty constables, Ahmad Azza Fahmi Azhar and Syafiq Ahmad Said, with a parang.a During the attack, Luqman managed to disarm one of the officers and used the seized firearm in the assault.2 Both officers were killed in the encounter. A third constable, returning from patrol, intervened and fatally shot Luqman, though sustaining serious injuries himself in the process.3 Given the attack’s location in Ulu Tiram and Luqman’s history as a former Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) member, the media and public initially speculated that it was a JI-linked attack, until authorities confirmed it as an Islamic State-inspired attack 28 days after the attacker’s family was detained under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (SOSMA).4 b

Like Father, Like Son

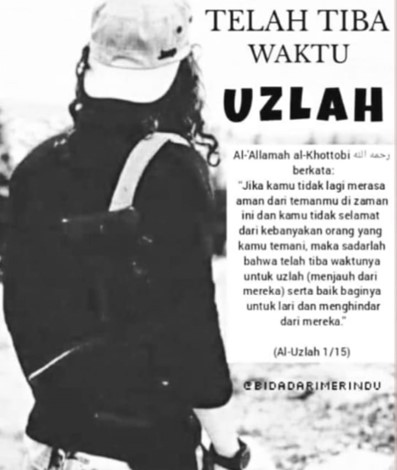

Radin Luqman bin Radin Imran’s father, Radin Imran, played a pivotal role in his youngest son’s radicalization, training, and attack method. From 2014, Imran fully committed himself to Islamic State ideology. He had aspired to travel to Syria, but this endeavor was limited by financial constraints.5 Instead, he systematically severed all ties with the outside world, plunging his family into seclusion. Simply put, Imran had ‘opted out’ of society. Neighbors initially attributed this withdrawal to shame over his prior JI involvement.6 In retrospect, Imran’s self-imposed exile, known as uzlah, was driven by his rejection of contemporary Malaysian society which he viewed as taghut (idolatrous), a pattern of withdrawal that parallels the Japanese phenomenon of hikikomori.c Imran’s fanatical beliefs were heavily influenced by Indonesian extremist preacher Aman Abdurrahman, leader of pro-Islamic State network Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) in Indonesia.7

At first glance, the Radin family seemed like a typical nuclear unit in the village. Born in Singapore in 1962, Radin Imran was later naturalized as a Malaysian citizen.8 Imran’s wife, Rosna Jantan, was also born in Singapore and the two of them were reportedly of Indonesian lineage. Together, they had four children, two boys and two girls. Radin Luqman was the second youngest. The exact details of their move to Malaysia and subsequent settlement in Ulu Tiram remain unclear, but sources suggested that they fled there to escape Indonesian authorities due to Imran’s past affiliations with JI.9

Imran embarked on a significant ideological journey in 1988 when he reportedly joined Darul Islam/Islamic Armed Forces of Indonesia (DI/NII), the very group that later would give rise to the founders and leaders of JI.10 Following his involvement with DI, Imran aligned himself with JI sometime in the 1990s, forging connections with key figures such as Noordin Mohammad Top, JI’s financier, and even underwent six months of militant training in the southern Philippines.11

Detachment 88 (Densus88), Indonesia’s anti-terror unit, was initially formed in 2003 in response to the 2002 Bali Bombing, primarily to counter the JI threat. Over time, the unit not only expanded in size, but it also expanded its focus to include the emerging threat posed by the Islamic State. As Densus88 strengthened its counterterrorism efforts, JI found itself increasingly alienated from the Indonesian public, as its violent methods no longer resonated with a population weary of extremist violence.12 Despite undertaking internal restructuring in 2009 to adapt to these challenges, JI’s influence continued to wane.13 Additionally, the group’s decision to concentrate solely on Indonesia and dismantle its operational structures in Mantiqi 1 (Malaysia and Singapore), 3 (Philippines), and 4 (Australia) further weakened its regional presence.14 JI eventually announced its dissolution in 2024.15

Between 2012 to 2013, Imran grew increasingly disillusioned with JI’s shifting strategies, as the group unexpectedly moved away from violent jihad toward more non-violent strategies.d This period of transition occurred during a turbulent period for JI, as it struggled to maintain its influence in Indonesia’s rapidly evolving security landscape.16 The group had already endured significant setbacks, including the mass arrests in Tanah Runtuh in 2007 and the splintering of its members, some of whom joined the now-former JI emir Abu Bakar Ba’asyir’s Jemaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT) and the Tanzim Aceh faction in 2011.17 Imran believed JI had changed drastically since he first joined at its inception, straying from the ideology that had initially drawn him to join the organization.18 By then, he felt that JI was being swayed by Indonesia’s democratic practices, including its electoral system and commitment to Pancasila.e

Dissatisfied with JI’s new direction, Imran redirected his allegiance. The intensifying restrictive security environment that undermined JI’s support base likely drove Imran to seek a more militant and aggressive cause. He turned to the Islamic State, which aligned with the violent jihadi ideals he had originally embraced and felt JI had abandoned. It was at this juncture that Imran encountered the pro-Islamic State group Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) and fell under the influence of Indonesian radical cleric Aman Abdurrahman.19 In 2014, Imran pledged bay`a to the Islamic State and its caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.20

Aman Abdurrahman and Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD)

Oman Rochman, known by his alias Aman Abdurrahman, is a central figure in Indonesia’s terrorism landscape, particularly due to his role as a hadith scholar and the recognized ideologue and leader of pro-Islamic State groups.21 Born in 1972 in West Java, Abdurrahman has been deeply involved in terrorism-related activities in Indonesia since 2004, beginning with his training of students in bomb-making techniques.22 By 2008, he had emerged as a radical preacher, fiercely opposing democracy, which he condemned as syirik (idolatry) and fundamentally incompatible with the teachings of Tawhid. Abdurrahman is a devout proponent of takfir and yakfur bit taghut, a doctrine that breeds intense hostility and legitimizes warfare against perceived oppressors, particularly rulers who eschew ‘Islamic’ laws in governance.23 This radical ideology forms the cornerstone of his rallying cry to target the police, whom he vilifies as agents of taghut (tyrants or false gods).f

In the shadows of Indonesia’s extremist landscape, the jihadi group Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) emerged as a formidable force under the ideological and spiritual guidance of Abdurrahman. Founded between late 2014 and early 2015, JAD united nearly two dozen extremist factions under a single banner, all swearing allegiance to al-Baghdadi.24 Abdurrahman’s influential teachings, which had previously inspired followers to participate in a jihadi training camp in Aceh, provided the foundation for JAD’s adaptation of Islamic State ideology to the Southeast Asian context, specifically Indonesia.25 As the Islamic State gained prominence in the mid-2010s, JAD aligned with its ideology. The declaration of a caliphate electrified Islamist extremists in the region, providing the group with recruitment opportunities.

JAD’s campaign of terror in Indonesia was marked by numerous acts of violence, targeting police stations, public spaces, and religious minorities.26 The group’s notoriety reached new heights with the January 2016 Jakarta attack, a carefully coordinated operation involving bombings and shootings that sent shockwaves through the capital and claimed multiple lives. Following this brutal debut, JAD escalated its tactics with the 2018 Surabaya church bombings.27 These chilling “amaliyah” operations underscored a disturbing evolution in extremist tactics and JAD’s willingness to shatter even the most fundamental societal norms, as entire families, including women and children, were deployed as suicide bombers against Christian congregations.28 JAD’s influence soon extended beyond Indonesia’s borders. The group facilitated training for other pro-Islamic State individuals from a network that spanned across Indonesia, Malaysia and the Southern Philippines, as evidenced by the 2021 Makassar bombing.29 This expansion was particularly significant, considering that the Islamic State’s regional “representatives” have traditionally been based in the Philippines (Islamic State’s East Asia Province, ISEAP).30 JAD’s focus on targeting state authorities was further underscored by the 2020 sword attack on a police station in South Daha, South Hulu Sungai Regency by pro-Islamic State/JAD members.31 Throughout its existence, JAD attracted individuals like Imran, who sought a more militant path in their extremist journey.

Through his writings and recordings, Abdurrahman cultivated a dangerous ecosystem of radical thoughts. His works served not merely as theoretical treatises but as catalysts for violent action, inspiring a new generation of extremists to wage war against perceived enemies of their twisted interpretation of Islam. His political and religious ideas were conveyed in his 2015 magnum opus, Seri Materi Tauhid: For Greatest Happiness (“The Monotheism Series: For Greatest Happiness”).32 This deceptively titled work serves as a manifesto, rigorously outlining his beliefs on identifying taghut and unequivocally rejects democracy as a man-made system incompatible with ‘Islamic’ principles. The influence of Abdurrahman’s teachings reverberates throughout the pro-Islamic State faction within JAD in Indonesia. His followers, galvanized by his words, have launched numerous attacks on police stations and outposts, which Abdurrahman designated as the frontline defenders of the despised taghut system. Seri Materi Tauhid has become essential reading among JAD adherents, including Radin Imran. The book’s presence among a trove of radical materials discovered in the Radin family home and within multiple external hard drives underscores its pivotal role in shaping the ideological landscape.33

A Father’s Extremist Journey

Imran’s pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State marked a turning point in his radicalization journey. He came increasingly under the influence of Abdurrahman’s interpretation of extremist ideology, a toxic blend of salafi scholarship, original Wahhabi teachings, and classical works by figures like Ibn Taymiyyah.34 This potent ideological cocktail reshaped Imran’s worldview, driving him to embrace an increasingly militant and isolationist stance. Consumed by an apocalyptic fear of fitnah akhir zaman—the strife and tribulations believed to precede Judgement Day—Imran took drastic measures to shield his family from what he perceived as the spiritual decay of the outside world.g Determined to preserve his family’s ideological purity, Imran assumed the role of educator, home-schooling his children from a young age, resulting in limited formal education.35 Only his eldest son managed to complete secondary school, while the others attended only up to sixth grade, fourth grade, or had no schooling at all.h

Through this carefully controlled environment, he sought to indoctrinate them with his fanatical pro-Islamic State beliefs, heavily influenced by JAD beliefs, creating a closed ecosystem of extremist thought.36 In this enforced isolation, the eldest son emerged as the family’s lifeline to the outside world. As the sole breadwinner, he worked as a driver for Grab, the region’s ride-hailing service, shouldering the responsibility of providing for the family’s daily needs. Meanwhile, the rest of the family remained cloistered in their secluded existence, entirely dependent on the eldest son’s irregular commission-based income. Despite their self-imposed isolation, the family maintained minimal technological connections. Each member owned a cellphone, with the eldest son’s device serving as the primary hotspot in the absence of WiFi for the father to scroll through Twitter and Facebook occasionally with the assistance of Luqman, the youngest son.37 A solitary laptop languished in disrepair, and the conspicuous absence of a television underscored the family’s selective disengagement from mainstream media.38

The exact sequence of events that culminated in Luqman’s deadly attack on the Ulu Tiram police station remains unclear. Luqman’s actions were the product of years of careful grooming and incitement by his own father.39 i The attack’s precise execution revealed a chilling level of preparation and purpose, therefore contradicted claims that Luqman was “untrained.”40 When allowed to view Luqman’s body for the last time, he requested to smell it, expecting the fragrance of musk, a scent traditionally associated with martyrdom in Islamic tradition. The absence of this fragrance shocked Radin Imran so profoundly that he stumbled backward, his expectations shattered.41 For years, he had nurtured his youngest son for the path of martyrdom, cultivating a vision of glorious sacrifice.42 The harsh reality of Luqman’s death, devoid of the expected divine signs, forced Radin Imran to confront the grim consequences of his indoctrination.

JAD’s Off-the-Grid Homestead Strategy

While the extreme off-grid nature of the Ulu Tiram episode was likely an isolated case, there is some precedent in the region. In the 1970s, Ashaari Muhammad (alias Abuya) founded Darul al-Arqam (also known as Jamaah Aurad Muhammadiah), a religious cult deeply entrenched in Islamic eschatology.43 What began modestly as a small gathering in Kampung Datuk Keramat quickly transformed into a significant movement. By 1975, al-Arqam had established a sprawling commune on a five-hectare plot in Kampung Sungai Penchala, on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur.44 The movement continued to expand throughout the early 1990s, establishing a presence in the northern states of Peninsular Malaysia, such as Perak and Penang, and in Sabah on the island of Borneo, where it acquired vast tracts of land.45 However, the Malaysian government eventually outlawed al-Arqam, arresting its leaders under the Internal Security Act (ISA) for allegedly conspiring to challenge the state and conducting secret weapons training.46 In hindsight, al-Arqam likely represents Malaysia’s earliest known radical commune. Although poorly understood at the time, its practices of intentional communal living bore striking similarities to contemporary survivalist movements in the United States.

The rise of JAD in Indonesia heralded the emergence of extremist communities operating within isolated, self-exiled cell-like structures known as “uzlah.”47 JAD’s attacks were often executed by a decentralized and compartmentalized network where micro factions operate independently, yet remained loosely connected by a shared ideology or mission, often without direct contact with other cells.48 The 2018 Surabaya bombings were particularly significant as they marked the first time entire families, including children, were mobilized to execute an attack. The families had isolated and homeschooled their children, bearing striking similarities to the behavior of the Radin family in Ulu Tiram.49 Just prior to the deadly assault, one of the families strategically increased their engagement with neighbors, which ultimately led the police to discontinue their surveillance.50 JAD’s shift to a decentralized model proved remarkably effective, enabling the group to execute terrorist operations with deadly precision. By favoring multiple, precise attacks over less frequent but larger operations, JAD maximized its effectiveness while minimizing organizational risk. This strategic pivot prioritized operational agility over raw destructive power.

The year 2019 witnessed the evolving tactics of extremist groups in Southeast Asia. Two distinct incidents highlight this transformation: a thwarted plot against Indonesia’s General Election Commission (KPU) and a devastating attack on a cathedral in the Philippines. In Indonesia, two independent pro-Islamic State cells from Bekasi and Lampung orchestrated a plot targeting the KPU.51 Motivated by the call of Islamic State spokesman in Iraq Abu al-Hassan al-Muhajir to attack voters, whom he deemed taghut (apostates) for participating in democracy, these cells operated autonomously yet shared a common goal.52 Indonesia’s elite counterterrorism unit, Densus88, successfully foiled the plot through persistent, intelligence-driven raids.53 Later that year, an Indonesian couple, Rullie Rian Zeke and Ulfa Handayani Saleh, executed a more successful operation. Traveling from Indonesia to the Philippines via Malaysia, they connected with members of the Sawadjaan-led cell of the Abu Sayyaf Group who facilitated them in the deadly bombings of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel Cathedral in Jolo, Sulu.54 While much of the focus was on their status as foreign terrorist fighters, the attack’s more critical aspect was its deliberate evasion of law enforcement surveillance.

The Sawadjaan cell’s facilitation of JAD members for this attack highlights the effectiveness of decentralized extremist networks. By leveraging dispersed cells and individuals, these groups can evade detection, plan, and execute attacks with alarming precision. This case illustrates the dichotomous nature of contemporary extremist operations: a carefully crafted veneer of isolation concealing intricate ties to leverage expansive networks or collaborative efforts.

In the case of Radin and his family, they took their commitment a step further. Their embrace of an isolated existence represented a marked departure from the established tactics employed by other pro-Islamic State or JAD adherents in Indonesia to evade surveillance. The origins of the Radin family’s seemingly off-grid, survivalist lifestyle remain unclear, yet mounting evidence suggests a curious ideological cross-pollination with the tenets of Western right-wing extremism.

Social media platforms and messaging apps, including TikTok, Telegram, and WhatsApp, have become hubs for numerous channels and content in Malay and Indonesian. There are spaces dedicated to eschatological contemplations, doomsday preparations, and the ominous specter of an impending apocalypse.55 On Telegram, while these channels may not necessarily align themselves with the Islamic State, the sporadic circulation of outdated issues of al-Naba, Dabiq, and Rumiyah serves as a poignant reminder to the faithful of their sacred duty to the path of jihad.

Intriguingly, these channels also showcase information culled from the American doomsday prepper community, replete with infographics that bestow knowledge on homesteading, food security anxieties, and a panoply of survival strategies. Amidst the cornucopia of shared PDF books, one title in particular commands attention: a survival guide authored by James Wesley, Rawles, a prominent figure in the American Redoubt movement.56 j The inclusion of material from the American Redoubt movement, with its emphasis on Christian values and conservative political ideals, adds an additional layer of complexity to this ideological melting pot that sharply contrast with the close kinship living norms traditionally found in Nusantara societies.k This unexpected fusion of seemingly disparate ideologies hints at a broader exchange of ideas, one that encompasses not only survivalist tactics and off-grid living methods, but also a shared sense of impending doom and the need for self-reliance in the face of an uncertain future.

The resulting worldview potentially aligns with many JAD or pro-Islamic State adherents’ “near enemy” strategy, targeting both kafr (infidels) and taghut (apostates), while anticipating the arrival of the Mahdi, followed by the Prophet Mohammad, and the second coming of Christ. This hybrid ideology mirrors that of fringe extremist communes in the West, particularly those associated with white supremacist and survivalist movements in the United States. These groups often establish intentional, rural, and radical communities through homesteading or smallholding, and actively seek self-sufficient, off-grid environments for spiritual purity.57 One example is Samuel Weaver, a self-proclaimed ‘white separatist’ who relocated to Ruby Ridge, Idaho, to isolate his family from what he viewed as a declining society.58 Weaver was part of Christian Identity, a diverse far-right movement in America, known for doomsday preparation and apocalyptic, conspiratorial ideologies along with racist violence.59 For the Radin family and its Western counterparts, isolation serves as a crucible for preparing for an impending apocalypse. This shared eschatological vision often culminates in a disturbing rationalization of violence as a necessary act of cleansing, paving the way for their envisioned post-apocalyptic world.60

The most striking parallels to JAD’s uzlah approach, as demonstrated by Imran’s deep-seated anti-social and anti-government sentiments, can be found in the infamous cases of Charles Manson’s Spahn Ranch and David Koresh’s Branch Davidian compound in Waco. In today’s interconnected world, ideas can transcend geographical boundaries with unprecedented ease. The uzlah phenomenon serves a dual purpose: not only as a practical strategy for survival and adaptation amidst government crackdowns on extremist activities, enabling more efficient and covert preparation for attacks, but also as a means to withdraw from society to demonstrate ideological commitment.61 Southeast Asia’s natural terrain, which has long nourished village life, provides a conducive environment for individuals such as Imran and his family to isolate themselves from society and sustain themselves.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the nature and cause of the Ulu Tiram attack is essential for formulating an effective response and deterrence policy. The Islamic State as an organization aims to reestablish and govern a caliphate, focusing on state-building as a primary goal as a necessary precursor for the apocalypse. While JAD originally aligned with Islamic State ideology and aspired to integrate Indonesia into this caliphate, its goals may have shifted. JAD-leaning proponents now aggressively pursue a more radical societal transformation, distinguishing themselves from other pro-Islamic State factions such as the Abu Sayyaf Group and the East Indonesian Mujahideen.

To be precise, Radin Imran was not driven by a conventional state-building agenda aimed at territorial expansion; rather, his actions were motivated by a belief in an impending apocalypse. His focus was on preserving his family’s sacrosanctity and redeeming their sins in preparation for what he saw as an inevitable end.l Extremists such as Imran actively work to expedite the collapse of the existing order, driven by a desire to create conditions they believe are necessary to prepare for the end of times and simultaneously absolve themselves.62 This strategy embodies a broader, more complex trend in extremist ideology that combines elements of the Islamic State’s apocalyptic vision—as exemplified by adherents’ early fixation on Dabiq as a prophesied battleground—with decentralized, society-wide transformative objectives.63 Imran’s approach represents a significant evolution in Southeast Asian Islamist extremism, blending traditional jihadi ideology with an urgent, apocalyptic worldview that reflects broader Nusantara Muslim eschatological anxieties. His case demonstrates how local religious and cultural elements shape the manifestation of extremist ideologies, creating a distinct syncretic form that draws from both global jihadi thought and deeply embedded Malay Muslim apocalyptic narratives. This is why it is essential not to characterize the event as merely an Islamic State-inspired attack, as Imran and his son were specifically following the Indonesian attack model.

This blind spot allows radical ideologies to take root and flourish beyond the reach of traditional intervention methods. The cornerstone of many PCVE programs—community engagement and reintegration efforts—proves woefully inadequate against individuals who have deliberately severed ties with mainstream society. In Radin’s case, his lack of prior arrests meant he was never obligated to participate in any outreach programs. These self-imposed exiles, viewing the broader community as fundamentally incompatible with their values, present a unique challenge that current strategies are ill-equipped to tackle. Reaching and rehabilitating individuals who live off the grid requires innovative methods that go beyond the current framework. A paradigm shift is urgently needed to tackle evolving radicalization threats and understand believers’ end goals. While Malaysia boasted a 97 percent success rate in its deradicalization efforts in 2019, it glossed over recidivism rates.64 m In the author’s view, Malaysia’s current PCVE framework is inadequate in addressing the doomsday prepper mentality. Existing deradicalization approaches focused on correcting misunderstandings of Islam prove ineffective against this mindset.

JAD-inspired attacks, in particular, have some parallels with other doomsday cult attacks driven by spiritual crises stemming from anxieties about an imminent apocalypse. One such example was Aum Shinrikyo that was responsible for the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack.n This recognition has significant implications for countering violent extremism strategies. Off-grid extremist communities and extremist homesteaders, operating in physical and digital isolation, present unique challenges for counterterrorism efforts. Conventional surveillance and intelligence methods face significant obstacles when confronting these secluded individuals. Despite awareness of potential threats and watchlisted individuals, authorities have repeatedly failed to adequately monitor or intervene.

This first-of-its-kind attack in Malaysia exposes a troubling vulnerability: Extremist actors can intentionally isolate themselves from society to evade detection and monitoring, all while projecting a benign façade as they plan attacks or travel for operations.65 Isolation can cultivate highly committed, ideologically driven actors who are elusive and challenging to identify and neutralize.66 Simultaneously, such extreme isolation may have broader implications, including mental health decline, as exemplified by Imran’s daughter, who exhibited symptoms of severe depression presumably from such conditions.67

Innovative methods that transcend the current PCVE framework are essential to counter this risk. A more nuanced, informed approach is crucial to address the unique risks posed by off-grid radicalization and develop targeted strategies for reaching and rehabilitating those who have intentionally disconnected from society due to their distrust and rejection of the state. Failure to adapt to these evolving threats may lead to an increased attempts carried out by individuals or groups that have slipped through the cracks of traditional counterterrorism measures or, worse, copycats.68 CTC

Munira Mustaffa is a security analyst specializing in Southeast Asian security challenges. She serves as a Fellow at Verve Research and a 2023 Visiting Fellow at the International Center for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) in The Hague and is an Affiliate Member of the AVERT (Addressing Violent Extremism and Radicalisation to Terrorism) Research Network. As the founder and executive director of Chasseur Group, she leads a consulting firm dedicated to analyzing complex security issues, focusing on non-traditional security and irregular warfare. X: @muniramustaffa

© 2025 Munira Mustaffa

Substantive Notes

[a] Parang is a type of curved blade common in Southeast Asia. Although it shares similarities with the Latin machete, the parang features a distinctive design, with a slimmer midsection and a downward-curving hilt, making it uniquely suited to the region’s dense vegetation and varied agricultural tasks.

[b] Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) was a militant Islamist organization based primarily in Indonesia. Founded in 1993, the group emerged with the goal of establishing an Islamic state in Indonesia, with four major territorial divisions (mantiqi) that spanned across the region. JI founders, Abu Bakar Bashir and Abdullah Sungkar, had established the Tarbiyah Luqmanul Hakim boarding school in Ulu Tiram in the early 1990s. The school had since closed down following government crackdown.

[c] This is a Japanese term that describes a severe form of social withdrawal, where individuals isolate themselves from society, often staying confined in their homes for extended periods. For further reading, see Andy Furlong, “The Japanese Hikikomori Phenomenon: Acute Social Withdrawal among Young People,” Sociological Review 56:2 (2008): pp. 309-325.

[d] JI gained international notoriety after executing several devastating terrorist attacks in the region, most notably the 2002 Bali bombings that killed 202 people. The group eventually disbanded in 2024.

[e] Pancasila, the foundational philosophy of the Indonesian state, consists of five principles: monotheism, a just humanity, national unity, deliberative democracy, and social justice for all.

[f] Tawhid refers to the Islamic theological concept of monotheism, specifically the absolute oneness of God (Allah). Conversely, taghut describes the act of worshipping entities other than the one true God, which is considered a fundamental violation of Islamic monotheism. The concept also applies to political oppression to describe tyrants who abuse power to suppress the vulnerable under the guise of divine authority. See also Shawkat Taha Ali Talafihah, Mohd Fauzi Mohd Amin, and Muhammad Mustaqim Mohd Zarif, “Taghut: A Quranic Perspective,” Ulum Islamiyyah 22 (2017): pp. 87-95.

[g] In Islamic eschatology, fitnah akhir zaman refers to a series of omens or conditions of strife that signal the approaching end of times. The term fitnah encompasses meanings such as treachery, disloyalty, unrest, and strife. However, in Malay, it is often used more narrowly to refer to libel, slander, or defamation. Akhir means “end” in both Malay and Arabic, while zaman translates to “age” or “time” in both languages. The trials and tribulations of the end times (fitnah akhir zaman) are discussed in the books of hadith under Kitabu al-Fitn (The Book of Tribulations) and Kitabu al-’Alamatu as-Sa’ah (The Book of the Signs of the Hour).

[h] Accounts of Imran’s children’s education status conflicted. According to the author’s source, the children were home-schooled. However, one article, citing Inspector-General of Police (IGP) Razarudin Husain, stated they did not enroll in school at all, while another referenced the IGP noting witness statements that indicated the children had limited education. See “Family of Ulu Tiram Attacker Held under Sosma,” Free Malaysia Today, May 23, 2024, and “Operator Kilang Dituduh Sokong Pengganas ‘IS’, Simpan Bahan Letupan,” BH Online, June 11, 2024.

[i] Radin Imran bin Radin Mohd Yassin was eventually charged with three offenses under Malaysia’s Penal Code: (a) incitement or encouragement of acts of terrorism, (b) supporting a terrorist group, and (c) possession of terrorism-related materials.

[j] These channels are not necessarily pro-Islamic State, but they are created with the aims to provide spiritual guidance and preparedness teachings to help community members navigate end-of-times uncertainties. The chat groups share diverse resources, from selected Hadith or Qur’anic verses to religious text interpretations to survival guides, drawing from both Islamic and non-Islamic sources, including American libertarian materials and wilderness survival texts such as Richard Graves’ Bushcraft.

[k] Kinship in this context refers to the social relationships that form the basis of family ties and community structures within Nusantara societies. These relationships are typically characterized by close, interdependent networks of familial and communal support, which often contrast with the more individualistic and self-reliant norms emphasized by movements such as the American Redoubt. For further reading, see Marshall Sahlins, “What Kinship Is (Part One),” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17:1 (2011): pp. 2-19.

[l] In his confession to the police, Radin Imran admitted that he was motivated by his anxieties over “fitnah akhir zaman.” This information was obtained by the author from a law enforcement source, August 2024.

[m] However, some of the recent Islamic State-related arrests included a number of recidivists, as reported by Zam Yusa in, “The Ulu Tiram Attack: Inspiration for Terror in Malaysia,” Diplomat, July 17, 2024. See also Thomas Renard’s analysis on Malaysia’s recidivism rate in “Overblown: Exploring the Gap Between the Fear of Terrorist Recidivism and the Evidence,” CTC Sentinel 13:4 (2020): pp. 19-29.

[n] Aum Shinrikyo’s founder, Shoko Asahara, was vehemently anti-government and projected a delusional, grandiose vision of himself as a savior. To realize this vision, he believed he had to hasten the arrival of his apocalyptic prophecy. See Robert Jay Lifton, Destroying the World to Save It: Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1999). See also Yoshiyuki Kogo, “Aum Shinrikyo and Spiritual Emergency,” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 42:4 (2002): pp. 82-101, which discusses “social drop-out” as a phenomenon in Japan that helped the cult gain members.

Citations

[1] Ben Tan, “In Johor, Two Cops Dead, One Injured After Man Attacks Police Station,” Malay Mail, May 17, 2024.

[2] The detail regarding the attacker wearing an Islamic State flag, which was omitted from media reports, was obtained from author’s interview with a law enforcement source in June 2024.

[3] “Ulu Tiram Attack: Injured Cop Maintains Fighting Spirit, to Continue Serving as Lawman,” Bernama, June 15, 2024.

[4] “Family of Ulu Tiram attacker, including S’porean, charged,” FMT, June 19, 2024.

[5] Details regarding the individual’s aspiration to hijrah to Syria were obtained from an interview conducted by author with a law enforcement source, August 2024. The information shared during the interview was based on post-arrest statements made by the individual in May 2024.

[6] “Family of Ulu Tiram Attacker Held under Sosma,” Free Malaysia Today, May 23, 2024.

[7] “The Ongoing Problem of Pro-Isis Cells in Indonesia,” IPAC Report No. 56, April 29, 2019, pp. 1-12 to understand the proliferation of autonomous pro-Islamic State cells in Indonesia.

[8] “No. 1827 –– Constitution of the Republic of Singapore: Notice of Proposed Deprivation Under Article 133(1),” Singapore Electronic Gazette, June 7, 2024. The notice highlights Singapore’s formal action to strip Imran of his citizenship following the Ulu Tiram incident.

[9] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement source, August 2024.

[10] Details about Imran’s group membership were obtained from author’s interview with a law enforcement source, June 2024.

[11] Details of his relationship with Noordin and subsequent training were obtained by author from a law enforcement source, August 2024.

[12] “The Re-Emergence of Jemaah Islamiyah,” IPAC Report No. 26 (2017): pp. 1-15.

[13] Alif Satria, “Understanding Jemaah Islamiyah’s Organisational Resilience (2019-2022),” ICCT, November 2, 2023.

[14] “Jemaah Islamiyah’s Military Training Programs,” IPAC Report No. 79 (2022): pp. 1-12.

[15] Zachary Abuza, “Jemaah Islamiyah’s Disbandment Appears Irreversible – And Real,” Benar News, November 29, 2024.

[16] “The Re-Emergence of Jemaah Islamiyah.”

[17] Ibid.

[18] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement officer source. This information is based on admissions made by the individual during his 28-day detention under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (SOSMA) following the attack.

[19] Details regarding his motivation were drawn from his post-arrest confessions in May 2024.

[20] “5 Family Members of Malaysian Man Who Attacked Police Station Face Terrorism Charges,” Associated Press, June 19, 2024.

[21] “Putusan PN Jakarta Selatan 140/Pid.Sus/2018/PN JKT.SEL,” Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung Republik Indonesia, February 5, 2018.

[22] “Indonesia: Jihadi Surprise in Aceh,” International Crisis Group, Asia Report Mo. 189, April 20, 2020.

[23] “COVID-19 and ISIS In Indonesia,” IPAC Short Briefing 1 (2020): pp. 1-7.

[24] “Jamaah Ansharut Daulah,” United Nations Security Council, March 4, 2020.

[25] Kirsten E. Schulze, “The Surabaya Bombings and the Evolution of the Jihadi Threat in Indonesia,” CTC Sentinel 11:6 (2018): pp. 1-6.

[26] Uday Bakhshi and Adam Rousselle, “The History and Evolution of the Islamic State in Southeast Asia,” Hudson Institute, February 28, 2024.

[27] Schulze.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “Indonesia’s Villa Mutiara Network: Challenges Posed by One Extremist Family,” IPAC Report No. 84, February 27, 2023, pp. 1-13. See also, “Learning from Extremists in West Sumatra,” IPAC Report No. 62, February 28, 2020, pp. 1-14 to understand the region’s pro-Islamic State’s network’s extensive reach.

[30] Bakhshi and Rousselle.

[31] “Police Capture Alleged Masterminds behind Kalimantan Police Station Terror Attack,” Jakarta Post, June 9, 2020.

[32] Vidia Arianti, “Aman Abdurrahman: Ideologue and ‘Commander’ of IS Supporters in Indonesia,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 9:2 (2017): pp. 4-9.

[33] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement officer source, August 2024.

[34] Muhammad Rashidi Wahab Wahab, Wan Fariza Alyati Wan Zakaria, and Wan Ruzailan Wan Mat Rusoff, “Ideologi Ekstrem Dalam Seri Materi Tauhid,” Journal of Public Security and Safety 14:2 (2022): pp. 15-40.

[35] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement officer source, August 2024.

[36] “Father of Ulu Tiram Police Station Attacker Charged with Supporting Islamic State Group, Possessing Firearms,” Star, October 23, 2024.

[37] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement officer source, August 2024.

[38] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement officer source, August 2024.

[39] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement officer source, August 2024. This information is based on admissions made by the individual during his 28-day detention under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (SOSMA) following the attack.

[40] Faisal Asyraf, “Man Who Attacked Ulu Tiram Police Station Untrained, Says Expert,” Free Malaysia Today, May 18, 2024.

[41] Information obtained by author from eyewitnesses.

[42] Information obtained by author from a law enforcement officer source, August 2024. This information is based on admissions made by the individual during his 28-day detention under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (SOSMA) following the attack.

[43] Sharifah Zaleha Syed Hassan, “Political Islam in Malaysia: The Rise and Fall of Al Arqam,” Asian Cultural Studies 15 (2006): pp. 43-55.

[44] Kamarulnizam Abdullah, The Politics of Islam in Contemporary Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2003).

[45] Ibid.

[46] Hassan.

[47] Eka Setiawan, “Fenomena Orang-Orang Menutup Diri,” Ruangobrol.id, October 3, 2019.

[48] Bakhshi and Rousselle.

[49] Kate Lamb, “The Bombers next Door: How an Indonesian Family Turned into Suicide Attackers,” Guardian, May 19, 2018.

[50] “The Surabaya Bombings and The Future of ISIS In Indonesia,” IPAC Report No. 51, October 18, 2018, pp. 1-12.

[51] “Indonesian Islamists and Post-Election Protests in Jakarta,” IPAC Report No. 58, July 23, 2019, pp. 1-19.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Farouk Arnaz and Telly Nathalia, “Anti-Terror Unit Seizes ‘Mother of Satan’ Bombs from Terrorist Hideouts,” Jakarta Globe, May 7, 2019.

[54] “Indonesia’s Villa Mutiara Network: Challenges Posed by One Extremist Family.”

[55] The channels and content described herein are based on the author’s original research and observations.

[56] The channels and content described herein are based on the author’s original research and observations.

[57] G. Jeffrey MacDonald, “A Surge in Secessionist Theology,” Christian Century, December 26, 2012.

[58] David Ostendorf, “Christian Identity: An American Heresy,” Journal of Hate Studies 1:3 (2002): pp. 23-55.

[59] Ibid. See also Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth, “Prophets of the Apocalypse: White Supremacy and the Theology of Christian Identity,” Cult Education, 2001.

[60] Robert Jay Lifton, Destroying the World to Save It: Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1999).

[61] Rahmat Hidayat, “Densus 88 Arrest Members of Jamaah Islamiah and Anshor Daulah in Three Different Locations,” Jakarta Daily, August 18, 2022.

[62] Mohd Irman Mohd Abd Nasir, Hanif Md Lateh, Rahimah Embong, and Muhamad Azuan Khairudin, “Penglibatan Ekstremisme dalam Kalangan Masyarakat Kelas Bawahan di Malaysia [The Involvement in Extremism Among Lower Class Citizens of Malaysia],” Asian Journal of Civilizational Studies 15 (2019): pp. 33-54.

[63] William McCants, “ISIS Fantasies of an Apocalyptic Showdown in Northern Syria,” Brookings, August 16, 2016.

[64] “97 per Cent Success Rate for Malaysia’s Deradicalisation Programme, Says Nga,” Bernama, January 10, 2019.

[65] Siswanto Sp, Shandra Sari, and Lestari Victoria Sinaga, “Pertanggungjawaban Pidana Memberikan Bantuan Menyembunyikan Pelaku Tindak Pidana Terorisme (Studi Analisis Putusan PengadilanNegeri No. 66/Pid.Sus/2020/PN Jkt.Tim),” Jurnal Rectum: Tinjauan Yuridis Penanganan Tindak Pidana, [S.l.] 4:2 (2022): pp. 106-118.

[66] “Extremist Women Behind Bars in Indonesia,” IPAC Report No. 68, July 21, 2020, pp. 1-26. This report briefly mentioned an Islamic State network in Indonesia running a clandestine program called “uzlah,” in which recruited members were trained and prepared in seclusion for their journey to Syria.

[67] Mohamed Farid Noh, “Court Orders Sister of Ulu Tiram Attack Suspect to Hospital for Depression,” NST Online, July 31, 2024. See also Norshahril Saat, “Ulu Tiram Killings: When Well-being is Key,” Fulcrum, May 30, 2024.

[68] Haezreena Begum Abdul Hamid, “Is Crime Contagious? The Ulu Tiram Incident and Its Aftermath,” Malay Mail, May 20, 2024.

Skip to content

Skip to content