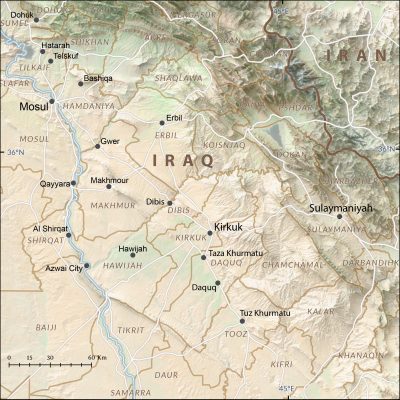

Abstract: Earlier this month, the Iraqi government announced the Islamic State had been driven from the small city of Hawija in Kirkuk Governorate—the Islamic State’s last remaining urban stronghold in northern Iraq. While this marked the culmination of a campaign by a diverse on-the-ground coalition to drive the group from urban areas in the region, the removal of the Islamic State also eliminated a unifying cause between the Kurdish peshmerga and the Iraqi military and federal police along with their Shi`a militia allies. With Iraqi forces now moving to take control of the oil rich region around Kirkuk away from Kurdish forces, escalating tensions in the region risks widening the faultlines between Iraq’s competing ethnic and sectarian power centers.

On October 4, 2017, Iraqi Security forces, along with pro-Iranian Shi`a militias known as Hashd al-Shaabi, entered the small city of Hawija in northern Iraq’s Kirkuk Governorate. Following a two-week-long offensive backed by coalition airstrikes, the jihadis were evicted from an area they had administered since June 2014.1 By that afternoon, Hashd al-Shaabi’s media arm released a statement that the city had been freed of Islamic State control.2 Iraq’s Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi and U.S.-led coalition partners confirmed the end of the Islamic State occupation there the following day.3

The Hawija campaign was initiated on September 21, 2017, when a constellation of Iraqi forces—including the army’s 9th Armored Division, the Emergency Response Division, Iraqi Special Operations Forces known as the Golden Division, elements of the Federal Police, and Iranian-backed Shi`a militias—began an offensive from the southwest4 to remove the Islamic State from a pocket of territory around the small city of Hawija in the western reaches of Kirkuk Governorate. Hawija had been the group’s last significant urban territorial holding in Iraq. In the second week of the coalition-supported Hawija campaign, according to official press releases, the United States carried out a total of 23 airstrikes in support of the Hawija operation between September 28 and when the operation for Hawija city largely concluded on October 5.5

After Iraqi troops and their Hashd al-Shaabi paramilitary counterparts moved in, some Islamic State militants fleeing Hawija moved toward the Kurdish-held district of Dibis, where several hundred fighters surrendered to Kurdish forces with some being transferred to Kirkuk city for interrogation.6 The fall of Hawija was more akin to that of Tal Afar, where Islamic State militants also fled. Militants and their families slipped out of Tal Afar northwest, ending up in the village of Sahil al Malih where approximately 150 fighters surrendered to Kurdish forces,7 in contrast to the grueling battle for Mosul where many detonated suicide vests as defeat approached rather than give themselves up.

In October 2016, Iraqi forces marching northward toward Mosul had bypassed Hawija because leaders in Baghdad had prioritized liberating Iraq’s second-largest city. This year, the inability of authorities in Baghdad and Erbil to agree on a political settlement for Kirkuk Governorate further delayed an offensive. There was no consensus as to precisely who should rebuild and govern the territory once the Islamic State was inevitably ousted. It was only after the speedy recovery of Tal Afar in the late summer that Iraqi forces finally focused on Hawija.

Before the offensive began, an estimated 1,000-1,200 Islamic State fighters remained in the Hawija pocket according to interviews with peshmerga fighters conducted by the author in August and September on the then static frontlines in Kirkuk Governorate.8 The pocket had been surrounded by a complex array of state and non-state forces, which greatly outnumbered the Islamic State. Most of the areas to the north and east were (and are) dominated by Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)-affiliated Kurdish peshmerga, with the exception of some Hashd al-Shaabi forces evidently loyal to the Iranian-born Iraqi cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani,a including in Taza Khurmatu and south of Daquq town in Kirkuk Governorate.b By contrast, there was no peshmerga presence to the south or west of Hawija. It is from this direction that Iraqi security forces and Shi`a militias, fresh from their victories in Mosul and Tal Afar, pushed eastward toward Hawija.

The Hawija operation was mostly completed in two fairly short phases. The first phase initially focused on liberating the town of al-Shirqat in neighboring Salah ad-Din Governorate and then dozens of villages in the vicinity of Hawija in a bid to ultimately liberate the city of Hawija itself. The next phase claimed Rashad Air Base 20 miles south of Hawija, which the Islamic State had used as a training center and logistics hub since mid-2014.9 Iraqi Army Lieutenant Colonel Salih Yaseen stated Baghdad intended to rebuild the damaged airbase, which would provide state security forces with a stronger foothold in order to “maintain security in the north.”10 This set the stage for Iraqi forces in mid-October to push up into Dibis district, where there is a large peshmerga presence.11

The sudden absence of Islamic State control in and around Hawija has exposed Iraq’s deeply entangled ethnic and sectarian fissures. Just days after the Islamic State abandoned Hawija, Qais al-Khazali, commander of Asaib Ahl al-Haq—an aggressively pro-Iranian Hashd al-Shaabi paramilitary outfit—gave a speech in Najaf stating he intended for forces under his command to capture Kirkuk and the governorate’s disputed territories from the Kurds in the near term. Iraqi forces, augmented by Hashd al-Shaabi fighters, have since moved into the area, pushing Kurdish forces out of the city.12

Northeastern Iraq (Rowan Technology)

A Nexus of Ethnic and Sectarian Strife

Almost 15 years after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, the future of the fiercely contested, hydrocarbon-rich Kirkuk Governorate is still uncertain. Baghdad claims Kirkuk is an integral part of the Republic of Iraq while Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) authorities portray the city and its surroundings as an inseparable geographic component of Kurdish identity. The late Iraqi President and PUK leader Jalal Talabani once described Kirkuk as the “Kurdish Jerusalem” during a public address in Suleimaniyah in 2011.13 The KRG held a controversial vote in Kirkuk on September 25, 2017, as part of a referendum for Kurdish independence from Iraq despite intense criticism from Arab and Turkmen political actors, such as the Iraqi Turkmen Front, who fear communal fragmentation if Iraq is formally split in the disputed territories.14

The vote was tallied at 92.73 percent in favor of independence, with a turnout calculated to be at 72.61 percent of the registered electorate.15 The United States and others involved in the international anti-Islamic State coalition had pleaded unsuccessfully with KRG President Massoud Barzani to postpone the vote, with the offensives in Hawija and al-Shirqat then ongoing and with the Islamic State still present in parts of al-Anbar Governorate.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi reacted to the referendum by demanding the KRG’s airports and borders with Turkey and Iran be put under federal control.16 He also demanded the KRG hand over its oil revenues,17 dramatically escalating the situation and setting the stage for Iraqi and Shi`a militia forces to retake Kirkuk.

Kirkuk Governorate, in which Hawija is located, has long acted as an incubator for conflict in Iraq because of its complex sectarian and ethnic mix of Kurds, Turkmen, Arabs, and several ancient Christian sects. The killing of some 50 Sunni Arab protestors by government forces during a violent crowd dispersal raid in Hawija in April 2013 allowed the Islamic State (then calling itself the Islamic State of Iraq, or ISI)18 to exploit communal grievances and anger over the sectarian policies and corruption associated with then Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and to engage disgruntled Sunni Arab tribesmen, helping set the stage for the group’s territorial takeover the following year.19

A peshmerga fighter in rural Dibis district at what was the Kurdish frontline against the Islamic State in September 2017 (Derek Henry Flood)

Disputed Demography

The population in Hawija city has historically been majority Sunni Arab, though some peshmerga field commanders along the Dibis and Daquq fronts dispute this claim.20 Villages astride the north-south highway between Tuz Khurmatu in Salah ad-Din Governorate and Kirkuk city have had a significant Shi`a minority historically, many of whom are Turkmen.21 According to an official census conducted in Iraq in 1957, Turkmen were the majority in Kirkuk city while Kurds were the overall majority in the governorate, with Arabs ranking the third most numerous group in the city and second in governorate.22

Among both Kurds and Turkmen from Kirkuk, there is a deep sense of historical grievance over the Ba’ath Party’s “Arabization” campaign in the governorate during the Saddam Hussein era, which was an attempt by the Ba’athists to suppress Kurdish or Turkmen challenges to their Arab nationalist hegemony. This included population transfers and the gerrymandering of Kirkuk Governorate’s boundaries, whereby Arab-majority districts like Hawija and Dibis northwest of Kirkuk city were attached to Kirkuk Governorate while heavily Turkmen Tuz Khurmatu was annexed to Salah ad-Din Governorate to make Kirkuk Governorate more Arab in its overall demography.23 Lieutenant Colonel Salam Omar, an ethnic Kurdish commander with the Kakai Battalion along the Daquq front, told the author that he and many Kurds held the view that Hawija had historically been a Kurdish majority area but was now unequivocally Arab in character because of the Saddam Hussein Arabization program and the fact that three years of Islamic State occupation had resulted in any Kurds that remained fleeing northward.24 Now as homeless Sunni Arabs continue to flee out of what was Islamic State-held territory in the Hawija area and as Hashd al-Shaabi militias encroach on the area, there is concern in some Kurdish circles that this displaced population will further alter Kirkuk’s demography.25

The Role of Hashd al-Shaabi

According to peshmerga fighters who interviewed internally displaced persons (IDPs) who had fled Hawija and surrounding Islamic State-controlled villages in the summer of 2017, Sunni Arab civilians feared communal reprisals from Hashd al-Shaabi based on their ethno-religious identity coupled with home geography.26 c Worsening conditions in Hawija city compounded such worries as the Iraqi security forces (ISF) and Hashd al-Shaabi began closing in late September. IDPs who made it to peshmerga-controlled access points along the frontline spoke of malnutrition and high infant mortality as the Islamic State clung to power in its final months in Hawija.27

The involvement of Shi`a militias in the offensive to liberate Hawija was particularly troubling to a population that witnessed the killing of 50 Sunni protestors in 2013 by heavily Shi`a security forces at the behest of then Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. The Hashd al-Shaabi militias of Soraya al-Khorasani and the Badr Organization, among others, were integral in the operation by fighting closely alongside the Iraqi army to free Hawija.28

The involvement of Hashd al-Shaabi militias also worried prominent Kurdish leaders, such as former Iraqi Minister of Foreign Affairs Hoshyar Zebari in Erbil and the late Iraqi president’s son Bafel Talabani in Suliemaniayh, who fear a post-Islamic State collision with Shi`a paramilitaries as well as proper Iraqi state forces.29 In early October 2017, these concerns were not allayed despite a five-point agreement reached between the Iraqi military and peshmerga leaders four days into the Hawija offensive, which hammered out force cooperation aimed at defeating the Islamic State.30 The agreement carefully avoided addressing the contentious issue of who should control the governorate’s disputed territories.31 Tensions between the peshmerga and Hashd al-Shaabi began ratcheting up immediately after Islamic State militants were ousted.32

A peshmerga commander at the Dibis front told the author he was highly skeptical of the agenda of Hashd al-Shaabi militias, which he believed were using the Hawija operation as a pretext to advance a Shi`a Arab agenda aimed at curbing Kurdish territorial claims. His worry was Shi`a Turkmen from the region would be mobilized to clash with peshmerga forces and eventually end Kurdish control of the Kirkuk region. The takeover of Kirkuk city and an increasing part of the region by Iraqi and Shi`a militia forces will no doubt have multiplied such concerns.33

Kirkuk’s Burning Wealth

The high-stakes competition between Iraqi power centers over the future of Hawija and the broader region has had much to do with Kirkuk region’s immense oil wealth that can produce an estimated 150,000 barrels per day depending on current security conditions and political stability.34 These energy resources were deftly exploited in recent years by the Islamic State, which had petroleum engineers extract valuable crude often by makeshift means. As the group cemented its gains in Iraq, oil smuggling in places like the Hamrin Field in the contested northern reaches of Salah ad-Din Governorate near Hawija became a substantial revenue stream.35

As Iraqi forces and their Hashd al-Shaabi allies moved closer to the Hawija pocket in late September, Islamic State militants employed scorched-earth tactics by setting fire to infrastructure and croplands.36 This included torching oil wells in the Hamrin Field’s Alas Dome southeast of the shrinking pocket in order to delay their opponents from economically benefiting from recaptured territory.d The oil well fires serve doubly as physical cover for the militants on the move from coalition aircraft above and advancing Iraqi and Shi`a militia forces.37

Iraqi forces in mid-October seized a number of oilfields near Kirkuk city. No matter how the oil wealth of the region is divided, it will not be easy to restore the degraded oil extraction and production facilities, which will likely continue to be the focus of insurgent attacks.38

A Poisoned Chalice

The freeing of Hawija city has resulted in the Islamic State losing its last significant urban territorial holding in Iraq, bringing relief to a population that has been under the group’s control for three straight years. The conflict resulted in many fleeing the city. It was estimated prior to 2014 that the wider Hawija district had approximately 500,000 inhabitants, but at the time of its liberation, the United Nations estimated that at most some 78,000 civilians remained in the city itself.39

Though it has been pushed out of its last significant city, the Islamic State is not yet completely out of the Iraqi sector of the theater. At the time of this writing, the group still controls remote Euphrates River Valley towns of al-Qaim and Rawa in al-Anbar Governorate, although Baghdad has proclaimed “the total defeat of Daesh is imminent.”40 Peshmerga field commanders believe that a significant number of Islamic State fighters will retreat into the countryside and blend into the civilian population to fight an asymmetric war.41

The removal of this jihadi pocket will also bring relief to peshmerga and Shi`a militias, which had withstood repeated Islamic State attacks on positions in Daquq, Taza Khurmatu, and Tuz Khurmatu orchestrated from inside the Hawija pocket as well as the Jebel Hamrin range.42 During the author’s visit to Hashd al-Shaabi’s base outside the village of Basheer just to the southwest of Taza Khurmatu in the late summer, incoming sniper rounds from a nearby Islamic State-held village was met quickly by return fire from Shi`a fighters from the al-Abbas brigade.43

By dislodging a common enemy, the collapse of the Islamic State’s control in Hawija removed the primary unifying cause upon which the diverse Iraqi coalition fighting the Islamic State could agree. With the region’s oil and gas wealth eyed by all sides, coupled with the Kurdish referendum having rocked northern Iraq’s fragile political status quo, the liberation of the Hawija pocket quickly escalated inter-ethnic disputes between Arabs, Kurds, and Turkmen, sectarian tensions between local Sunnis and various Shi`a armed groups, and between Baghdad and Erbil. CTC

Derek Henry Flood is an independent security analyst with an emphasis on the Middle East and North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia. He is a contributor to IHS Jane’s Intelligence Review and Terrorism and Security Monitor. Mr. Flood traveled to various frontline positions on the eastern outskirts of Hawija in August and September 2017 to research this article. Follow @DerekHenryFlood

Substantive Notes

[a] The author encountered some of these Hashd al-Shaabi forces in late summer 2017. Although they refused to comment on the matter when asked by the author, they appeared to be aligned with the Ayatollah Sistani-influenced faction of Hashd al-Shaabi that supports an Iraqi national agenda while emphasizing the defense of the holy shrines of Najaf, Karabala, and Khadimyya. Author observations, Kirkuk city and outside Taza Khurmatu, August 2017. The Hashd al-Shaabi forces that stormed Hawija were allied to the pro-Iranian camp. Author correspondence, Iranian source, September 2017.

[b] Peshmerga stationed nearby along the Daquq front told the author they had virtually no interaction with the nearby Shi`a militias before the operation began in September. Author interview, peshmerga Lieutenant Colonel Salam Omar, Daquq front, August 2017.

[c] The peshmerga received a small number of IDPs from Hawija before the offensive began. Babak Deghanpisheh, “Fears of abuse as Iraq Shi’ite fighters set to storm city,” Reuters, October 17, 2016.

[d] The Islamic State had employed similar tactics in August 2016 when it was ousted from Qayyarah. Samya Kullab, Kamaran al-Najar, Rawaz Tahir, Muhammed Hussein, and Araz Mohaemed, “Facing defeat in Hawija, IS torches oil wells,” Iraq Oil Report, September 29, 2017; “Civilians Pay Price of ISIS’s ‘Smoke War’ Around Mosul,” Agence France-Presse, October 24, 2016.

Citations

[1] “Iraqi forces liberate 11 villages from Daesh near Hawijah,” Al-Sumaria News, September 21, 2017; “Federal police to launch 2nd phase to retake Hawija from ISIS,” Baghdad Post, September 27, 2017; Maher Chmaytelli, “Iraqi forces in final assault to take Hawija from Islamic State,” Reuters, October 4, 2017.

[2] “The leadership of Hashd al-Shaabi is celebrating the liberation of the Hawija,” Al-Hashed.net, October 4, 2017.

[3] “Iraqi prime minister says government forces have retaken northern town of Hawija from Islamic State group extremists,” Associated Press, October 5, 2017; “Iraqi Security Forces liberate Hawijah,” inherentresolve.mil, October 5, 2017.

[4] Osama bin Javaid, “Iraq: Who will control Hawija after ISIL?” Al Jazeera, September 23, 2017.

[5] Various press releases, U.S. Central Command, September 28-October 5, 2017.

[6] Feras Kilani, “Iraq’s Hawija: Where have IS fighters gone?” BBC News, October 7, 2017.

[7] Leyla H. Sherwani “Dozens of IS Militants in Tel Afar Surrender to Peshmerga,” Bas News, August 29, 2017; Ahmed Rasheed, “Iraqi forces begin house-by-house fight for last IS holdout at Tal Afar,” Reuters, August 30, 2017; “Around 150 ISIS members surrender to peshmerga northwest of Tal Afar,” Nalia Radio and Television, August 31, 2017.

[8] Author interview, PUK-aligned peshmerga fighters, Dibis district frontline, September 2017.

[9] Ahmed Rasheed, “Iraqi forces seize air base from Islamic state near Hawija,” Reuters, October 2, 2017.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Author’s observations, Dibis district, Kirkuk Governorate, August and September 2017.

[12] Baxtiyar Goran, “Shia militia leader vows to enter Kirkuk, Shingal soon,” Kurdistan 24, October 9, 2017.

[13] Raber Younis Aziz, “Talabani Criticized for Designating Kirkuk ‘Jerusalem of Kurdistan,’” AKnews, March 9, 2011.

[14] “The Arab Council calls for the removal of Kirkuk from the referendum of Kurdistan and renews its demand for the liberation of Hawija,” Al-Sumaria News, September 18, 2017: Fehim Tastekin, “Kurdistan referendum leaves Iraq’s Turkmens in quandary, Al-Monitor, September 18, 2017; author’s observations, Erbil and Kirkuk city, September 2017.

[15] “Massive ‘Yes’ vote in Iraqi Kurd referendum,” Agence France-Presse, September 27, 2017.

[16] Haider al-Abadi, “All land & air border-crossings in Iraqi Kurdistan must be returned to federal jurisdiction within 3 days,” Twitter, September 26, 2017.

[17] Maher Chmaytelli, “Iraqi PM presses case for Baghdad to receive Kurdistan oil revenue,” Reuters, September 30, 2017.

[18] Derek Henry Flood, “Kirkuk’s Multidimensional Security Crisis,” CTC Sentinel 6:10 (2013).

[19] “Iraq violence continues with 40 dead,” Associated Press, April 25, 2013; Abdel Bari Atwan, Islamic State: The Digital Caliphate (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015), p. 56.

[20] Author interviews, peshmerga field commanders, August and September 2017.

[21] Author’s observations, Kirkuk and Salah ad-Din governorates, September 2017.

[22] David Romano, “Kirkuk: Constitutional Promises of Normalization, Census, and Referendum Still Unfulfilled,” Middle East Institute, July 1, 2008.

[23] Liam Anderson and Gareth Stansfield, Crisis in Kirkuk: The Ethnopolitics of Conflict and Compromise (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), pp. 28-30.

[24] Author interview, peshmerga Lieutenant Colonel Salam Omar, Daquq district, August 2017.

[25] Baxtiyar Goran, “Kirkuk governor concerned about ethnic balance and IDPs,” Kurdistan 24, July 18, 2016.

[26] Author interviews, peshmerga fighters, Dibis frontline, September 2017.

[27] “Situation Report #3, Hawija, Kirkuk governorate,” Access Aid Foundation, September 26, 2017.

[28] Author correspondence, Iranian source, September 2017.

[29] “Zebari warns of ‘abnormal movement’ by Shiite militia near Peshmerga frontline,” Rudaw, October 11, 2017; “Bafel Talabani addresses the international community and Baghdad,” Kurdsat News, October 12, 2017.

[30] “Iraqi military, Kurdish Peshmerga reach 5-point agreement for Hawija ops,” Rudaw, September 24, 2017.

[31] Ibid.

[32] “Shiite Hashd al-Shaabi Opens Fire on Kurdish Peshmerga in Hawija,” Millet Press, October 7, 2017; “Kurdish Peshmerga Forces Block Roads to Mosul Amid Escalating Tension,” Millet Press, October 12, 2017.

[33] Author interview, peshmerga Colonel Shaduman Mohamed, Dibis district base, Kirkuk Governorate, September 2017.

[34] Newzad Mehmud, “Erbil supports larger self-rule for Kirkuk oil industry,” Rudaw, March 9, 2016.

[35] “IS oil smugglers continue stealing from Alas field,” Iraq Oil Report, June 15, 2016; Kamaran al-Najar and Ben van Heuvelen, “Rivers of crude spill from IS smuggling operation,” Iraq Oil Report, August 9, 2017.

[36] Sarah Benhaida, “Cinders and desolation in Iraq’s Hawija after IS,” Agence France-Presse, October 7, 2017.

[37] “Militant set fires at oil wells south of Hawija attempt to block the advance of security forces,” Al-Ghad Press, September 29, 2017.

[38] “Militants storm Iraq’s Bai Hassan oilfield and gas facility near Kirkuk,” Agence France-Presse, July 31, 2016; “Northern Iraq crude oil exports dive on pipeline outages, oil field attacks: sources,” Platts, August 15, 2016.

[39] Rikar Hussein and Yahya Barzinji, “Iraqi Army, Allied Shiite Forces Enter IS-held Hawija,” Voice of America, October 4, 2017.

[40] Government of Iraq, “The total defeat of Daesh is imminent as Iraq’s Armed Forces prepare to liberate the towns of Qaim & Rawa in Anbar province,” Twitter, October 8, 2017.

[41] Author interviews, Colonel Shaduman Mohammed in Dibis and Commander Sayyed Hossein outside Tuz Khurmatu, September 2017.

[42] “Three Peshmerga killed in ISIS attack south of Kirkuk,” NRT News, August 1, 2017; “Peshmerga Repels IS Attack on Daquq Frontline,” Bas News, May 25, 2016.

[43] Author’s observations, Basheer, Iraq, August 2017.

Skip to content

Skip to content