Abstract: Recent attacks, disrupted plots, and arrests in Europe and the United States have suggested that the terrorist threat posed by older extreme far-right individuals might be increasing. A deep dive into the United Kingdom, which has seen five attacks by extreme far-right men over the age of 47 since June 2016, indicates that most attackers had limited direct connections to the organized extreme far-right, conducted attacks involving limited but rapid planning, and—perhaps as a result—had relatively limited impact in terms of casualties. These attacks coincided with (and likely led to) significant increases in the number of extreme far-right-linked men aged 51 and over being referred to the U.K.’s Prevent program and discussed within its Channel program. The U.K. case study and data raise important policy questions regarding the likely effectiveness of preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) interventions for older demographics in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

As 2022 came to a close, a series of attacks and arrests in Europe appeared to hint at the emergence of a possible new trend: older (and even geriatric) far-right terrorists.a In mid-October, a 75-year-old woman was one of five arrested in Germany for plotting to kidnap the country’s health minister and bring down its power grid.1 Two weeks later, a 66-year-old U.K. man firebombed a migrant center in Dover,2 and in early December, those arrested for plotting to overthrow the German government included several individuals over the age of 60.3 Finally, on December 23, a 69-year-old man attacked a Kurdish cultural center in Paris, killing three.4

Although terrorism is typically seen as the preserve of the young, terrorist attackers over the age of 45 are not a new phenomenon in either the Islamist or far-right context,5 with the oldest known attacker an 88-year-old white supremacist who attacked the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., in 2009.6 In November 2022, the United Kingdom’s Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation noted that “the most recent completed extreme right-wing terrorist … attacks [had] all [been] carried out by older men,”7 with the last attack by anyone younger than 47 in 2015.

Despite this reality, U.K. authorities—and others facing a far-right terrorism problem8—have characterized the threat as originating from a “technologically aware demographic of predominantly young men, many of them still in their teens,”9 with disrupted plots since 2017 featuring two individuals in their late teens and one in their early 20s.b Given this discrepancy between the age of the primary source of the extreme far-right threat identified by U.K. authorities and the age of those successfully conducting far-right terrorist attacks, this article will use the United Kingdom as a case study to better understand the terrorist threat posed by older individuals motivated by extreme far-right ideology.

This article starts with a comparative analysis of the backgrounds of and methodologies used by the recent U.K. attackers, seeking to identify any key commonalities and inconsistencies. It then explores U.K. government data to help understand whether these attacks are reflective of any change in the threat posed by older extreme far-right individuals in the United Kingdom. Finally, it identifies some implications from this analysis for policymakers and responses to far-right terrorism in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

U.K. Case Study: Recent Attacks and Attackers

There were five completed far-right terrorist attacks perpetrated in the United Kingdom since 2015. The following short case studies examine each of the perpetrators.c

Case 1: Thomas Mair

Fifty-two-year-old Thomas Mair, who killed Jo Cox MP in June 2016, was described as a recluse and a “loner in the truest sense of the word” who had never had a job or a girlfriend, had no friends, and had lived alone since 1996.10 Mair had a long-standing interest in the extreme far-right, sharing his hope that “the white race would prevail” in a letter to the editor of a South African far-right magazine in 1991.11 Following a series of far-right bombings in London in 1999, Mair purchased extreme far-right instructional material and subscribed to a variety of American neo-Nazi magazines.12

Although there is limited data on Mair’s activities until 2016, police found newspaper clippings related to Anders Breivik’s 2011 attack in Norway in Mair’s home. His online research into previous attacks against politicians and his target indicates that the febrile nature of the Brexit referendum campaign finally prompted Mair into action. Of the five attacks, his was the only one in which a firearm was used.13 Mair was jailed for life in November 2016, having been found guilty of murdering of Jo Cox, two weapons offenses, and stabbing a bystander who tried to intervene.14

Case 2: Darren Osborne

On June 19, 2017, 47-year-old Darren Osborne drove a rented van into worshippers outside Finsbury Park Mosque in London, causing the death of one person. He is now serving life in prison for what the judge sentencing him described as a “terrorist attack.”15 Like Mair, Osborne was long-term unemployed and described as a loner, although he had a long-term partner and four children. Osborne, who had a history of substance abuse and had recently threatened suicide, also had a 30-year criminal record, including for theft, burglary, and assault.16

In contrast to Mair, Osborne’s radicalization was rapid, driven by his disgust at a May 2017 BBC drama-documentary about the sexual abuse of children by a group of British-Pakistani men. He joined Twitter in early June 2017, following far-right accounts including that of Tommy Robinsond and Britain Firste and engaging with material from those “determined to spread hatred of Muslims.”17

Osborne had initially sought to conduct a mass-casualty attack against the annual Al-Quds Day march in central London, targeting both Muslims and senior Labour Party politicians who he believed would be in attendance.18 Having driven from Wales that morning (June 18, 2017), Osborne failed to get close to the march and subsequently drove for hours before finding the mosque in the early hours of June 19. Despite his chaotic targeting approach, the attack was not entirely spontaneous, with Osborne having inquired about renting the van on June 16. The following day, he was evicted from a pub for ranting about “killing Muslims.”19

Case 3: Tristan Morgan

On July 21, 2018, Tristan Morgan, a 51-year-old X-ray technician, set fire to a synagogue in Exeter on the Jewish holiday of Tisha B’Av.20 Morgan also set himself on fire and was quickly arrested after police identified his van using the synagogue’s CCTV. Morgan was described as having a “deep-rooted anti-Semitic belief, embodied in a desire to do harm to the Jewish community.” He was convicted of arson and two terrorism-related offenses for possessing “The White Resistance” manual and publishing a song encouraging terrorism. Morgan, who had no history of violence, was reportedly “psychotic” during the attack and was handed an indefinite hospital order.21

Case 4: Vincent Fuller

On March 16, 2019, 50-year-old father of four Vincent Fuller threatened passers-by near his home in Surrey with a baseball bat, shouting “All Muslims must die. White Supremacists rule.” When Fuller broke the bat damaging a vehicle, he took a knife from his home and slashed a 19-year-old sitting in a parked car.22

There is limited information about Fuller’s background, although like Osborne, he had an extensive criminal record with 24 convictions and had served a six-year prison sentence. A video of the previous day’s far-right attack on mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand,23 was found on Fuller’s phone. In a Facebook post less than two hours before the attack, Fuller stated, “I agree with what the man did in New Zealand,” adding “Kill all the non-English and get them all out of our England.”24 Fuller was convicted of attempted murder, carrying a weapon, affray, and racially aggravated harassment, and sentenced to 18 years and nine months in prison, with a further five-year extended sentence. The judge sentencing Fuller described his offense as a “terrorist attack.”25

Case 5: Andrew Leak

Lastly, on October 30, 2022, 66-year-old Andrew Leak threw three petrol bombs at a migrant center in Dover. The fire caused minor injuries to two staff members, and Leak was found dead in his car just minutes later. Leak, a twice-married grandfather and pensioner, was reportedly suffering from cancer and claimed online that he had spent time in prison. Like Osborne, Leak admired Tommy Robinson, sharing posts by him and other extreme far-right actors, engaging with racist and anti-immigrant content, and promoting COVID-19 conspiracy theories.26 As a result of his racist, inflammatory posts, Leak had reportedly been banned from Twitter the week prior to the attack and suspended from Facebook on multiple occasions.27

Leak was the only attacker who used explosives, although his devices were described as ‘crude’ and had minimal impact. Like Osborne, he traveled to his chosen target, driving 120 miles from his home in High Wycombe to Dover. Like Fuller, he also shared his intentions online, posting a video one hour before the attack threatening to “obliterate” Muslim children.28 At the inquest, the senior national coordinator for counterterrorism policing in the United Kingdom stated that although mental health was likely a factor, “I am satisfied that the suspect’s actions were primarily driven by an extremist ideology.”29

Key Findings: Commonalities and Inconsistencies

What then can be learned from these five attacks and attackers? Each had an individual pathway toward violence, despite sharing a similar age range, gender, and ideology. There are, of course, commonalities. Osborne and Fuller had long criminal records, while Leak claimed to have served prison time. Loneliness, substance abuse, and unemployment recur, as does the role of the internet and an increasingly febrile U.K. political atmosphere as radicalizing or catalyzing factors. But as a group, what is striking is how unremarkable the perpetrators are.

There is also no consistent attack method or targeting methodology. The only common threads across all five attacks are their relative failure in terms of impact—none were mass- or even multiple-casualty attacks (though not all aimed to be)—and their relatively limited planning time. Several appear to have been spontaneous in their timing and targets, with only Mair, Morgan, and Leak exhibiting any degree of successful planning. Their spontaneity and relative failure are no doubt connected.

Finally, although several attackers had some online or offline connectivity with extreme far-right groups and individuals, they appear to have been largely passive recipients of narratives and propaganda. All acted alone, with some ‘leaking’ their intentions in the hours prior to their attack.

Individuals with limited or no connection to the organized extreme far-right, conducting low-tech attacks with limited or no lead-in times are difficult for authorities to identify and disrupt, regardless of age. However, this is not the only type of threat posed by this age demographic. The aforementioned December 2022 plot to overthrow the government in Germany and the attack that month on the Kurdish cultural center in Paris demonstrate that older far-right terrorists can be more connected, more organized, and more deadly than those seen so far in the United Kingdom.

Additional U.K. Data Sources and Findings

To better characterize the threat posed by older and geriatric extreme far-right individuals in the United Kingdom, it would be useful to understand trends relating to terrorism-related arrests since 2016. However, the upper age category in U.K. data on terrorism-related arrests is “over 30,”f making it impossible from this official data alone to determine if arrests for individuals 45 and above specifically are on the rise.g

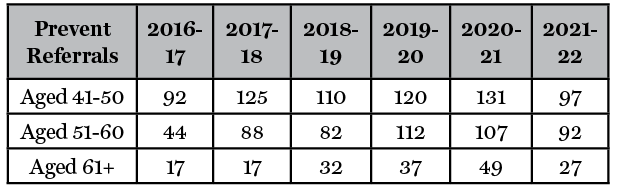

The other potential source of data is the United Kingdom’s Prevent program. Under this construct, law enforcement, other public entities, and the community at large refer individuals they identify as at risk of being drawn into terrorism. Although total Prevent referrals for individuals of all ages relating to the extreme far-right increased by 35% between April 2016 and March 2022,h referrals among the 51-60 and 61+ age groups for individuals linked to extreme far-right increased by 109% and 58%, respectively. However, extreme far-right referrals for these age groups—and the 41-50 age group—peaked in 2020-21, declining in 2021-22.

Table 1: Prevent referrals of older individuals with connections to the extreme far-right, 2016-2022i

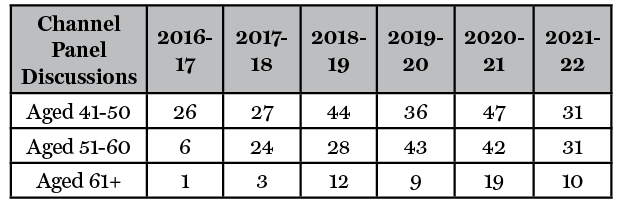

Following an initial triage of the Prevent referrals, those individuals who are assessed as vulnerable to being drawn toward committing terrorism offenses (but who do not pose an imminent threatj) are then reviewed by a multi-sectoral Channel Panel, made up of representatives from these public bodies. Although the total number of Channel Panel discussions for individuals linked to the extreme far-right increased by 121%, the figures for individuals above the age of 51 with connections to the extreme far-right outstripped this increase. However, figures for 2021-22 again showed a decline across all three age groups from the previous year.

Table 2: Channel Panel discussions of older individuals with connections to the extreme far-right, 2016-2022

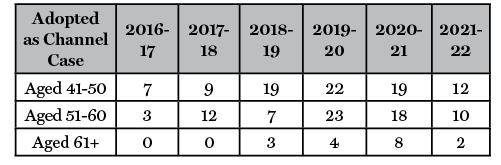

Through these discussions, the Channel Panels decide whether individuals require interventions or support to prevent them from committing terrorism-related offenses. If so, individuals can be adopted as Channel cases, although as involvement within Channel is voluntary, older individuals assessed as requiring support may choose to reject it. Although the total number of Channel cases for individuals linked to the extreme far-right increased by 173%, the figures for individuals above the age of 51 outstripped this increase. Again, the number of cases peaked (in 2019-20) before subsequently declining.

Table 3: Channel cases of older individuals with connections to the extreme far-right, 2016-2022

It is important to note that for the 2021-22 dataset, the UK Home Office introduced additional granularity to its characterization of ideological connections (referred to as “type of concern”), increasing the number of categories from four to 11. Given the significant drop-off in the number of extreme right-wing older individuals across all three datasets in 2021-22, it is possible that some of the individuals who would previously have been categorized as extreme right-wing now sit in one of these new categories.k

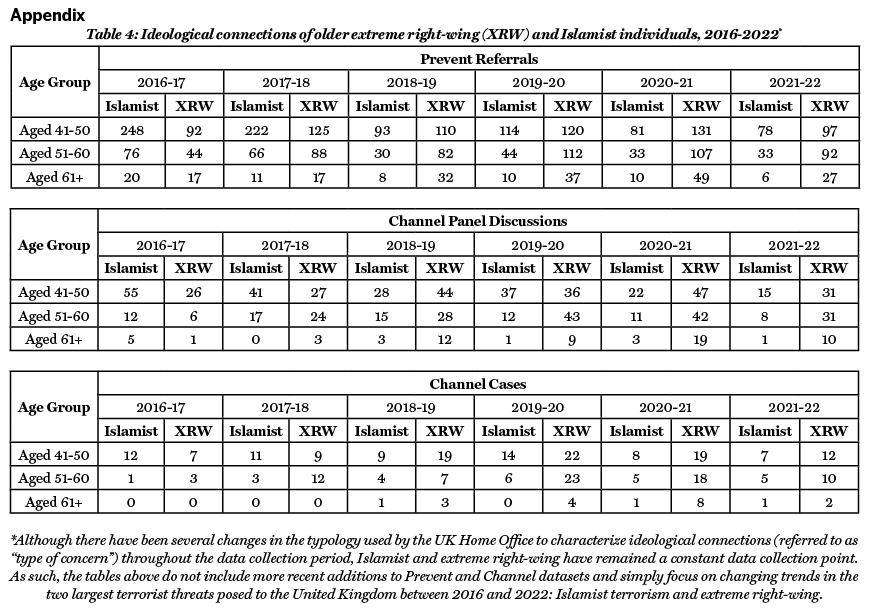

Despite this recent drop-off, the data still shows a marked shift in the primary ideological connection of individuals aged 51 and over referred through Prevent during the period 2016/17 to 2021/22, with nearly three times as many individuals referred for far-right-related concerns as Islamist from 2018/19 to 2021/22 (see the first table in the appendix). Individuals discussed at Channel Panels and adopted as Channel cases in that age group were also more likely to be affiliated with the far-right than any other ideology from 2017/18 onward (see the second and third tables in the appendix).30

Prevent data is, of course, an imperfect tool for determining whether there has been an increase in radicalization among this (or any) age group. As the UK Intelligence and Security Committee noted in a recent report, an increase in Prevent referrals “does not necessarily indicate an increase in the extreme right-wing threat, but rather indicates a greater awareness of the potential risk and the greater focus being placed on this issue.”31

So, while it would be inaccurate to correlate more Prevent referrals and Channel Panel discussions involving those 51 and over with an increase in the far-right threat from this age group, the data does suggest that at a minimum, police and other public bodies are increasingly aware that this demographic is at risk of being involved in terrorism.

Conclusion: Implications for Policymakers and P/CVE Responses

The cases studies and data analysis point to the two key questions recent attacks pose for U.K. policymakers (and those elsewhere): Will existing systems identify individuals within older age groups who are vulnerable to radicalization and/or who are already radicalized? And, if identified, will the preventative programming and tailored interventions currently offered be effective for them?

On the first question, the above data suggests that a range of U.K. authorities have recognized the potential vulnerability of individuals aged 51 and above to radicalization. The failure of the U.K. system to prevent the attacks explored here does not in and of itself indicate that specific opportunities were missed (particularly given the low-tech methodology used and limited planning times). And it is to be hoped that similar cases would be treated differently in the future, given the increased awareness that the Prevent data appears to indicate.

There are, however, questions about how individuals are identified in the United Kingdom. Will a system that relies heavily on referrals from the education system and the policel identify concerns relating to older, isolated individuals who are disconnected from other touchpoints across local government? Other sources of referrals—friends, family, the community—rely on a broad awareness of potential warning signs among this age group. It is unclear to what extent this awareness exists, or indeed has been included in messaging by relevant authorities, despite recent attacks by older far-right extremists.

Whether existing programming in the United Kingdom (and elsewhere) will be effective for this age group is more difficult to answer. CVE programming recipients have tended to be young, with programming developed in response to how terrorist groups have sought to radicalize young people (particularly online).

The profiles of the five U.K. attackers (incomplete though they are) suggest that online connectivity between them and the organized extreme far-right predominantly took place on mainstream social networks, and points to the role of the broader political environment as a catalyzing factor. Although online material played a significant role in Darren Osborne’s radicalization, none of it, as far as is known, broke any terrorism or criminal law.32

Exposure to this lawful but hateful material does not require access to the niche apps and channels often used by young extreme far-right actors. Globally, 51% of 50- to 65-year-olds use Facebook, while 58% of those over 56 use YouTube.33 Tailoring preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) programming to engage with this very online but perhaps less tech-savvy cohort may present challenges, due to the difficulty of identifying how and where to engage with them, and how to teach people who grew up before the internet age to navigate the current information environment.

There remain significant gaps relating to the extent of this phenomenon in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, with further data needed to understand the extent to which recent arrests and attacks might be indicative of a broader trend. And while it would be unwise to draw broader conclusions solely from the U.K. experience, it is an important reminder that the profile of terrorist attackers continues to evolve in terms of gender, ideological inspiration, and in this case, age. Last year saw a U.K. teenager convicted for far-right-related terrorism offenses conducted when he was 1334 as well as an attack by 66-year-old Andrew Leak. Norms and expectations among authorities and the general public about what a terrorist looks and sounds like—and key warning signs and trigger points for intervention—need to evolve at a similar pace, as do the types of intervention available to address their unique age-related needs. CTC

David Wells is a global security consultant who spent the past five years as Head of Research and Analysis at the UN Counter-Terrorism Directorate (UN CTED) in New York. He is also an Honorary Research Associate at Swansea University’s Cyber Threat’s Research Centre (CYTREC) and a non-Resident Scholar at the Middle East Institute. Twitter: @davidwellsct

© 2023 David Wells

Substantive Notes

[a] In this article, “older” is used as a relative term, to contrast with the traditional counterterrorism focus on threats posed by young people and the primary extreme far-right threat identified by U.K. authorities (individuals in their teens and early 20s). Although different datasets explored through the article include different age ranges, the article’s primary focus is on individuals aged 45 and over. Geriatric is used to refer to individuals over the age of 65.

[b] Ethan Stables was sentenced to an indefinite hospital order for planning to attack a pub hosting an LGBT+ night in June 2017 when he was 19 years old. For more information, see “Ethan Stables sentenced over gay pride attack plot,” BBC, May 30, 2018. Jack Renshaw was jailed for life for planning to murder a local MP and policewoman in July 2017, when he was aged 22. For more information, see “Jack Renshaw: MP death plot neo-Nazi jailed for life,” BBC, May 17, 2019. Eighteen-year-old Luke Skelton was charged in November 2021 with having carried out “hostile reconnaissance” of three police stations. In May 2022, the jury in Skelton’s case failed to reach a verdict. For more information, see “Luke Skelton: Jury fails to reach verdict on Wearside student accused of terror plot,” BBC, May 13, 2022.

[c] In addition to these completed attacks, U.K. authorities have disrupted 37 “late stage” attacks since 2017, with around one-third linked to the extreme far-right. For more information, see David Parsley, “Terror investigations at record high as threat of extreme right wing ‘lone actors’ rises,” The i, December 28, 2022.

[d] Tommy Robinson (born Stephen Yaxley-Lennon) is the founder and former leader of the extreme far-right group the English Defence League, and remains a high-profile U.K. far-right activist. See the Counter-Extremism Project’s profile and other news reporting (e.g., The Guardian archive) for more information.

[e] Britain First is an extreme far-right, anti-Muslim, anti-immigration group founded in 2011 by former members of the British National Party. Multiple party members have been convicted of terrorism offenses. See Hope Not Hate’s website for further information.

[f] The most recent statistics for the period ending September 2022 are available at “National statistics: Operation of police powers under the Terrorism Act 2000 and subsequent legislation: Arrests, outcomes, and stop and search, Great Britain, quarterly update to September 2022,” UK Home Office, December 8, 2022.

[g] Given that U.K. authorities already have access to this data, it is recommended that further granularity is included in these statistics moving forward, allowing for an easily accessible understanding of trends relating to age and terrorism-related arrests across all ideological persuasions.

[h] All Prevent-related data in the tables presented in this article and included in the broader analysis is taken from UK Home Office statistics. See “Official Statistics: Individuals referred to and supported through the Prevent Programme, April 2021 to March 2022,” UK Home Office, January 26, 2023.

[i] All Prevent and Channel data in this section and included in Tables 1-4 is collected on a 12-month basis between April 1 and March 31. Thus, the data for 2016-17 is from April 1, 2016, to March 31, 2017, and so on.

[j] Depending on the type and level of risk identified by police in this initial assessment, these cases may be escalated from the Prevent space into the ‘Pursue space,’ requiring more immediate investigative or disruptive action. See “Channel Duty Guidance: Protecting people vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism,” 2020, for more information.

[k] In 2020-21, the categories were Islamist, Extreme Right-Wing, Other and Mixed, unstable, or unclear. In 2021-22, these were adjusted to Extreme Right-Wing, Islamist, Other, Conflicted, No specific extremism issue, High CT risk but no ideology present, Vulnerability present but no ideology or CT risk, No risk, vulnerability or Ideology Present, School massacre, Incel and Unspecified. “Official Statistics: Individuals referred to and supported through the Prevent Programme, April 2021 to March 2022.”

[l] These two streams have consistently been the source of a majority of Prevent referrals. See “Official Statistics: Individuals referred to and supported through the Prevent Programme, April 2021 to March 2022.”

Citations

[1] Tristan Fielder, “75-year-old arrested for plotting to kidnap German health minister,” Politico, October 14, 2022.

[2] “Dover migrant centre attack: Firebomber died of asphyxiation, inquest told,” BBC, November 8, 2022.

[4] “Paris shooting: Three dead and several injured in attack,” BBC, December 23, 2022.

[5] See, for example, John Horgan, Mia Bloom, Chelsea Daymon, Wojciech Kaczkowski, and Hicham Tiflati, “A New Age of Terror? Older Fighters in the Caliphate,” CTC Sentinel 10:5 (2017) and “Capitol Hill Siege, Demographics Tracker,” Program on Extremism, George Washington University, which includes data on those charged in relation to the 2021 Capitol Hill siege.

[6] “Accused Holocaust museum shooter dies,” NBC News, January 6, 2010.

[9] “Annual report 2021-22,” Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, December 13, 2022.

[11] Alex Amend, “Here are the letters Thomas Mair published in a pro-Apartheid Magazine,” Southern Poverty Law Center, June 20, 2016.

[12] Tom Burgis, “Thomas Mair: The making of a neo-Nazi killer,” Financial Times, November 23, 2016.

[13] Cobain, Parveen, and Taylor.

[14] Tom Burgis, “Thomas Mair found guilty of MP Jo Cox murder,” Financial Times, November 23, 2016.

[15] Sewell Chan, “Makram Ali Died of Injuries in Attack Near London Mosque, Police Say,” New York Times, June 22, 2017; Kevin Rawlinson, “Darren Osborne jailed for life for Finsbury Park terrorist attack,” Guardian, February 2, 2018.

[17] Rawlinson, “Darren Osborne jailed for life for Finsbury Park terrorist attack.”

[20] “Tristan Morgan: Far Right Antisemitic Terrorist,” Community Security Trust, July 5, 2019.

[22] “Vincent Fuller: White Supremacist car park stabbing ‘terrorist act,’” BBC, September 10, 2019.

[23] For more on the attack, see Graham Macklin, “The Christchurch Attacks: Livestream Terror in the Viral Video Age,” CTC Sentinel 12:6 (2019).

[25] Ibid.; “Vincent Fuller: White Supremacist car park stabbing ‘terrorist act.’”

[29] “Dover migrant centre attack driven by right-wing ideology – police,” BBC, November 5, 2022.

[30] All Prevent-related data in the tables below and included in the broader analysis is taken from UK Home Office statistics. See “Official Statistics: Individuals referred to and supported through the Prevent Programme, April 2021 to March 2022,” UK Home Office, January 26, 2023.

[31] “Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism,” Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, July 13, 2022.

[33] “The 2022 Social Media Demographics Guide,” Khoros, 2022.

Skip to content

Skip to content