Abstract: As early as the 1980s, the U.S. intelligence community documented the ways in which Iran deployed chemical weapons for tactical delivery on the battlefield. Nearly 40 years later, U.S. officials formally assessed that Iran was in non-compliance with its Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) obligations, pointing specifically to Tehran’s development of pharmaceutical-based agents (PBAs) that attack a person’s central nervous system as part of a chemical weapons program. Over time, concern about this program has increased, with reports to the Organisation for the Prevention of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), statements by multilateral groups such as the G7, and a variety of U.S. government reports and sanctions. Today, with Iran’s proxies wreaking havoc throughout the region, officials worry Tehran may have already provided weaponized PBAs to several of its partners and proxies. Such a capability, tactically deployed on the battlefield, could enable further October 7-style cross-border raids or kidnapping operations. With the region on edge following the targeted killing of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, followed by an Israeli ground campaign targeting Hezbollah infrastructure along the border, and the Iranian ballistic missile attack on Israel, concern about the use of such tactical chemical weapons is high.

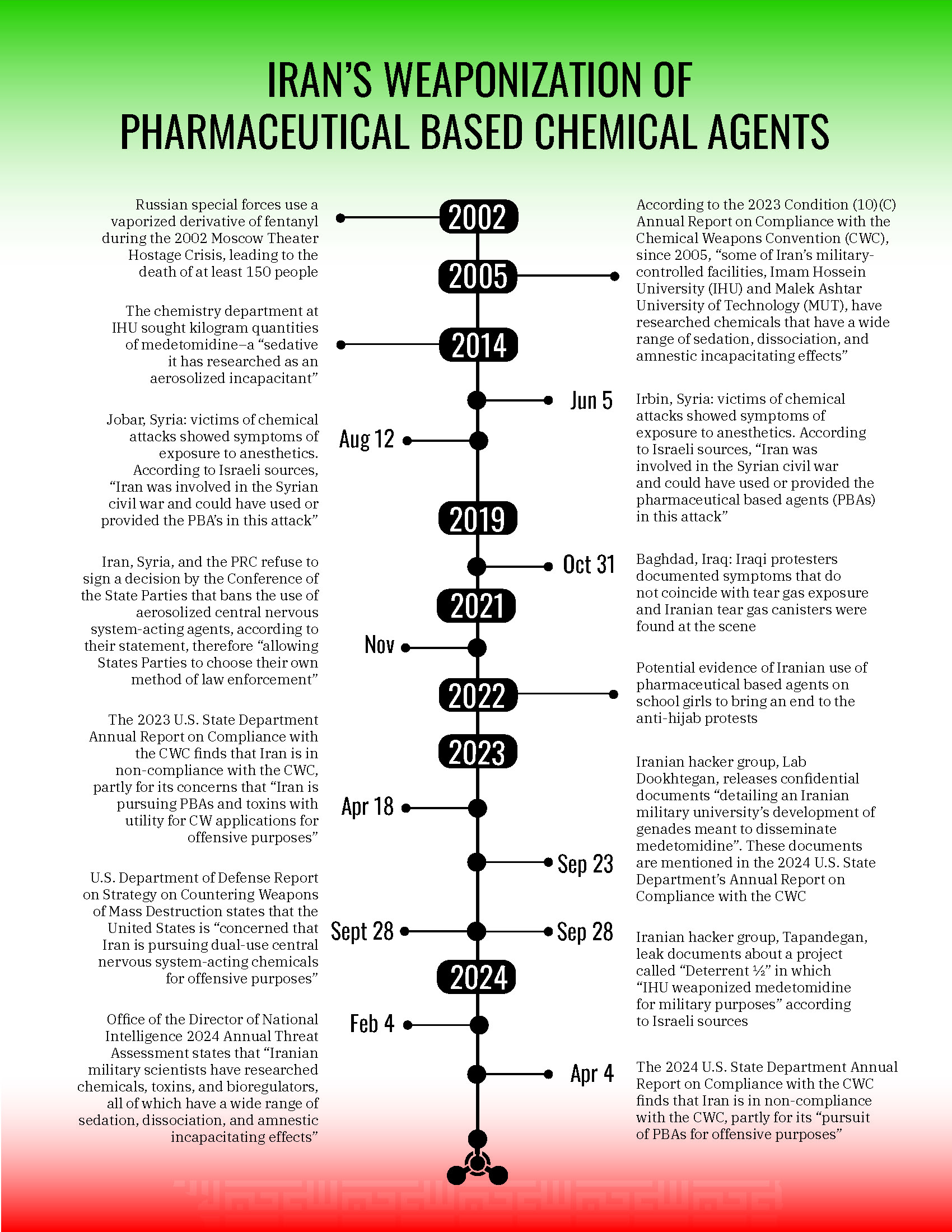

Since at least 2005, U.S. authorities contend, Iran has conducted extensive research and development of pharmaceutical-based chemical agents (PBAs), primarily anesthetics used to incapacitate victims by targeting the central nervous system, in violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention.1 While Tehran contends its PBA program is allowed under an exception for developing crowd control tools for law enforcement, Iran has been called out—along with Russia and Syria—for developing these dual-use chemical agents by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).2 While the issue has received scant public attention, the U.S. State,3 Treasury,4 and Defense5 departments, as well as the Office of the Director of National Intelligence6 and the G7,7 have highlighted the issue and begun taking action against Iranian entities tied to this activity.

Iran’s weaponization of PBAs, however, is no longer just a matter of research and development. Beyond its R&D program, Iran now appears to have produced fentanyl-based or other types of weaponized PBAs and provided these to partners and proxy groups that may have already used them in several cases in Iraq and Syria.8 At home, Iranian journalists have investigated the poisoning of thousands of school-aged girls with some suspecting the symptoms displayed suggest the involvement of PBAs (some believe this was an Iranian government response to a protest movement, while the Iranian government claims it was an attack by unspecified ‘enemies’).9 Now, after a year of near-daily rocket fire by Hezbollah into northern Israel, Israeli authorities fear Hezbollah may attempt an October 7-style cross border raid into Israel from Lebanon in which the group could use Iranian-manufactured PBAs to incapacitate and kidnap Israeli soldiers deployed along the border, and enable fighters to penetrate farther into Israel to attack civilian communities.10 In the post-October 7 security environment, U.S. officials have prioritized the issue of Iran’s weaponization of PBAs in their diplomatic engagement at multinational fora like the OPCW and in bilateral engagements with allies around the world. The stakes are now higher still after the targeted killing of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah and the Israeli military maneuvers in southern Lebanon aimed at rooting out Hezbollah military infrastructure there.

This article briefly explains what pharmaceutical-based agents are, and explores the dangers posed by weaponized PBA’s as tactical battlefield weapons developed by Iran. Based on declassified CIA reports, the article explores the history of Iraq’s use of chemical weapons against Iran, Iran’s own development and deployment of chemical weapons, and concerns that Iran has provided weaponized PBAs to its partners and proxies. This led the United States to take a leading role calling out Iran’s weaponized PBA program, which became a more immediate national security concern for Israeli in particular in light of Lebanese Hezbollah’s ‘Plan to Conquer the Galilee.’ This year, the U.S. intelligence community inserted a warning about Iran’s chemical weapons program, including incapacitating agents, in its 2024 annual threat assessment. All of which means far more multilateral and national-level actions are needed to counter Iran’s development of PBAs and its transfer of these dangerous agents to partners and proxies.

The Danger of Weaponized PBAs

According to the Government Accountability Office, PBAs are “chemicals based on pharmaceutical compounds, which may or may not have legitimate medical uses, and can cause severe illness or death when misused.”11 PBAs present not only a national security concern, but can also have severe and even fatal health effects. These dual-purpose chemicals are often used for medical and veterinary purposes, but can also be weaponized for offensive goals.12 For example, the U.S. State Department has highlighted a case in which the chemistry department at Iran’s Imam Hossein University sought large quantities of medetomidine, a veterinary anesthetic drug with potent sedative effects, even though the department had little history of veterinary or other medical research. The university specifically researched the drug as an aerosolized incapacitant, and the quantities it sought (over 10,000 effective doses) were inconsistent with the reported research purposes.13

In an April 2023 report to Congress, the State Department determined that Iran’s riot control agent (RCA) declaration, which is required under the CWC, was incomplete.14 The report, which fulfills a congressionally mandated requirement for an annual report from the president, found that Iran developed more than one riot control agent that it marked for export but which it never declared as a chemical agent it holds for riot control purposes, as required by the CWC. “The United States has concerns,” the State Department concluded, “that Iran is pursuing PBAs and toxins with utility for CW applications for offensive purposes.”15

From Mustard Gas to Fentanyl-Based Incapacitating Agents

The use of chemical weapons (CW) is a sensitive issue for Iran, which suffered from Iraq’s widespread use of chemical weapons during the Iran-Iraq war. While Iran registered over 50,000 victims of Iraqi chemical attacks requiring medical care, an estimated one million Iranians were estimated to have been exposed to nerve agents or mustard gas throughout the war.16 And yet, Iran also used chemical weapons and riot control agents during the Iran-Iraq war, according to a declassified CIA report, including those using mortars and artillery as delivery systems.17 Tehran started producing small quantities of CW “since at least 1984,” according to the CIA.18 “Iran,” the CIA reported in 1988, “used chemical weapons on a very limited scale beginning in 1985, probably for testing or training.”19 That R&D progressed to the point of being able to deploy CW agents within a couple of years. Iran produced about 100 tons of CW agent (mostly mustard) in 1987, the CIA determined, adding it anticipated Iran could produce twice that by the following year. “Since April 1987,” the CIA report continued, “Iran has launched several small-scale chemical attacks with mustard and an unidentified agent that causes lung irritation.”20 This, the agency determined, was not some rogue operation, but the result of a decision by Iranian policymakers to develop and deploy chemical agents, in large part to retaliate for Iraqi chemical attacks.21

In a 2001 report to Congress from the Director of Central Intelligence, the DCI reported that the CIA’s Weapons Intelligence, Nonproliferation, and Arms Control Center (WINPAC) determined that Iran was “vigorously pursuing” programs to produce indigenous Weapons of Mass Destruction, including chemical weapons.22 Though party to the CWC, Iran “continued to seek chemicals, production technology, training, and expertise from entities in Russia and China that could further efforts at achieving an indigenous capability to produce nerve agents” and “probably also made some nerve agents.”23

The event that would trigger Iran’s interest in more vigorously pursuing a program to specifically weaponize dual-use pharmaceuticals as incapacitating agents would come the following year. In 2002, Russian special forces pumped a pharmaceutical-based chemical gas into a Moscow theater where Chechen terrorists held hundreds of hostages.24 The Russians overtook the terrorists and gained control of the theater, but some 120 hostages died in the operation along with the attackers—many from inhaling the gas, believed to have been some kind of fentanyl derivative.25 According to the 2023 Annual Report by the U.S. State Department, published Iranian papers cited the “potential weapons applications of the PBAs; one specifically referenced the use of fentanyl during the 2002 Dubrovka theater hostage crisis.”26

In the wake of the Moscow theater attack, Israeli and American officials say, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Ministry of Defense worked to develop chemical weapons and ammunition to serve as delivery systems—primarily grenades and mortars—to be used tactically on the battlefield.27 From the outset, these experts contend, the idea was to provide partners such as the Syrian regime and proxy groups such as Iraqi Shi`a militias and Lebanese Hezbollah with weaponized PBAs to incapacitate their adversaries. Once inhaled, these agents cause victims to lose full consciousness and enable the forces deploying them to advance quickly and quietly and/or take captive the unconscious victims. Moreover, deploying weapons produced with dual-use items, and then providing said weapons to proxies, provides Iran with multiple layers of cover and reasonable deniability for having done so at all.

Provision of Weaponized PBAs to Proxies

As early as 1988, U.S. intelligence analysts noted with concern that “CW tactical delivery methods have improved with experience,” adding that “CW can contribute to tactical successes as one component of an integrated fireplan.”28 Fast forward to 2024, and Israeli officials report “with high confidence” that Iran has provided chemical incapacitating agents to proxies in Iraq and Syria.29

Israeli authorities point to several cases in recent years in which chemical agents were used and victims displayed symptoms of exposure to anesthetics.30

On June 5, 2014, victims of a chemical attack in Irbin, Syria, showed symptoms beyond just difficulty breathing, nausea, and reddening of the eyes to also include loss of consciousness and a total loss of feeling.

On August 12, 2014, victims of a chemical attack in Jobar, Syria, experienced reduced consciousness, along with other symptoms.

On October 31, 2019, pro-Iranian Iraqi militias helped Iraqi law enforcement with riot control after a wave of civil protests in Baghdad, Iraq. Some protestors experienced symptoms inconsistent with tear gas, including loss consciousness and unresponsiveness to stimuli. In this case, Iranian tear gas grenades were found at the scene.31

Whether or not these cases involved the use of weaponized PBAs or some other kind of chemical agent, Israeli officials point to these cases as reasons to be concerned that Iran could—or perhaps already has—provided weaponized PBAs to partners like the Syrian regime or proxies like Shi`a militias in Iraq or Lebanese Hezbollah. “The most concerning part of all this for the Israel Defense Forces,” an IDF official explained, “is Hezbollah getting this kind of material.”32 Hezbollah already has battlefield tear gas dispersal systems such as grenades and mortars, and could use these as delivery systems for grenades filled with PBAs. Indeed, the IDF is already acting on the assumption that Hezbollah has such systems and has already forward deployed them to the field for use in operations to kidnap Israeli soldiers deployed along the border or as part of a plan to infiltrate into Israel to attack civilian communities in an October 7-style attack.33

Calling Out Iran’s Weaponized PBA Program

The incidents outlined above piqued the concerns of intelligence and counterproliferation officials about the potential implications of Iran’s weaponized PBA program, which has started getting public mentions in government documents and reports. In 2018, the State Department assessed in an annual report that Iran was in non-compliance with the CWC for failure to declare its chemical weapons production facility, its transfer of chemical weapons, and its retention of an undeclared stockpile of chemical weapons.34 Then, in the 2019 edition of that annual report, the State Department specifically noted its concerns about Iran’s failure to declare its complete holdings of Riot Control Agents (RCAs), and its “serious concerns that Iran is pursuing PBAs for offensive purposes.”35 The G7 expressed its concerns about Iran’s CWC non-compliance in an April 2019 report on non-proliferation and disarmament.36

By the end of 2020, the U.S. government was ready to take public action targeting persons and entities tied to Iran’s weaponized PBA program. That December, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated the Shahid Meisami Group for “testing and producing chemical agents and optimizing them for effectiveness and toxicity for use as incapacitating agents.”37 The designation press release positioned Shahid Meisami Group as “an organization subordinate to” the Iranian Organization of Defensive Innovation and Research (also known as SPND), and which is responsible for several SPND projects “to include testing and producing chemical agents and optimizing them for effectiveness and toxicity for use as incapacitating agents.”38 Sanctioned by the State Department in 2014, SPND was founded in 2011 by the late United Nations-sanctioned Iranian nuclear weapons developer Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, who was killed by a remote-controlled weapon (reportedly deployed by Israeli agents) in November 2020.39 “In the field of nuclear and nanotechnology and biochemical war, Mr. Fakhrizadeh was a character on par with Qassim Soleimani but in a totally covert way,” an advisor to Iran’s foreign ministry later explained to The New York Times.40

Also designated in December 2020 was the head of Shahid Meisami Group, Mehran Babri, who had previously worked at Iran’s Defense Chemical Research Lab. Shahid Meisami Group, the State Department would later report, also maintained close ties to Iranian military entities.41 For example, it participated in Iranian defense expos where it provided fact sheets on its products, including the “Ashkan” irritant hand grenade that creates smoke containing the chemical riot control agent dibenzoxazepine (CR), and a “Fog Maker System” capable of producing high volumes of smoke and fog in a short period of time. “This is noteworthy,” the State Department reported, “because it can disseminate debilitating chemicals, like CR, over a large area quickly.”42

It took some time for U.S. and other officials to make it happen, but a year later, in December 2021, the Conference of States Parties of the [CWC] Convention adopted a decision—opposed only by Iran, Syria, and Russia—reaffirming the ground rules for the use of central nervous system (CNS)-acting chemicals for law enforcement purposes.43 The decision made a distinction between riot control agents, which can legitimately be used by law enforcement, and CNS-acting chemicals, which cannot. While the decision committed parties “not to use riot control agents as a method of warfare,” Iran did not sign on.44 Moreover, the decision included a loophole in that it banned aerosolized use of CNS-acting agents, without explicitly banning their production, research, development, or transfer.

For the United States and its allies, the bottom line was clear, loopholes notwithstanding. In September 2023, the U.S. Department of Defense categorized Iran’s as a “persistent threat” when it comes to WMD challenges, noting not only Iran’s nuclear program but also its CWC non-compliance.45 The department’s annual report on its strategy for countering weapons of mass destruction made Washington’s position on Iran’s weaponized PBA program crystal clear: “The United States is also concerned that Iran is pursuing dual-use central nervous system-acting chemicals for offensive purposes.”46

That concern led to the State Department’s decision to list the fact that Iran specifically develops PBAs as part of its chemical weapons program as an additional CWC violation in its April 2024 report on CWC compliance.47

Interestingly, one source the State Department cited in that 2024 report was Lab Dookhtegan, which says it is a hacker organization working against Iranian state-sponsored cyber actors. The State Department report points to a September 23, 2023, Lab Dookhtegan social media post showing allegedly confidential documents “detailing an Iranian military university’s development of grenades meant to disseminate medetomidine, an anesthetic that is a central nervous system-acting chemical.” According to these leaked documents, in which the U.S. government has sufficient confidence to cite them in an official government report, “this development included information on the production and testing of prototype weapons” to disseminate these nerve agents.48 Speaking at the March 2024 Executive Council meeting of the OPCW, the U.S. representative to the OPCW was clearer still:

The United States assesses that Iran maintains a CW program and did not declare all of its chemical weapons related activities and facilities as required when it ratified the CWC. The United States also assesses that since acceding to the CWC, Iran has developed and filled weapons with pharmaceutical-based agents in violation of its obligations to the Convention.49

Shortly thereafter, in July 2024, the State Department imposed sanctions against the Hakiman Shargh Research Company on the basis of the organization’s proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, specifically chemical weapons. A close read of the press statement announcing the designation reveals it was focused on the company’s role in developing and transferring weaponized PBAs.50 After noting that the United States first assessed Iran was in non-compliance with its CWC obligations in 2018, the State Department spokesman added that Iran further “violated the CWC due to its development of pharmaceutical-based agents as part of a chemical weapons program.” Then, for the first time, a U.S. government official came out publicly with the underlying security concern at hand: “The United States will continue to counter any efforts by the Iranian regime to develop chemical weapons, including those that may be used by its proxies and partners to support Iran’s destabilizing agenda of inciting and prolonging conflict around the world.”

Hezbollah’s “Plan to Conquer the Galilee”

October 7 ushered in a wave of Iranian-inspired and supported proxy warfare against Israel unlike anything the country had previously experienced. Since then, Israelis across the political spectrum have been traumatized and fear terrorist groups will attempt further cross-border raids into Israel. For years, Israeli intelligence knew of a notional Hamas plan to storm across the border into Israel to kill and capture civilians, but they dismissed Hamas’ ability to execute such a plan and put more trust than they should have in high-tech defense systems to protect them.51 Years earlier, Israeli officials exposed Hezbollah tunnels dug into Israel under the border with Lebanon which was intended to be used as part of a plot to storm across the border from Lebanon.52 Indeed, Hamas’ October 7 operation came straight out of Hezbollah’s playbook.53

Hezbollah’s plan to storm into the northern Galilee, overrun Israeli communities, kill and kidnap civilians, and lay roadside bombs to attack first responders remains a present threat for Israel. The Alma Research and Education Center, an Israeli think-tank based in northern Israel and focused on that border, assessed that Hezbollah’s Radwan special forces unit “reached operational capacity to fulfill its mission to invade the Galilee” in 2022.54 This remains a pressing operational threat today, and is one of the reasons the over 60,000 Israelis displaced from their homes in northern Israel remain wary of returning home.55 Indeed, Israeli authorities contend the targeted killing of Hezbollah commander Ibrahim Aqil and several other Radwan special forces leaders in an airstrike on September 20, 2024, prevented just such a ground invasion, dubbed Hezbollah’s “Plan to Conquer the Galilee.”56

Israeli intelligence officials assess that Iran develops incapacitating chemical agents not only for the use of its own law enforcement and military personnel, but also for members of its proxy network.57 With this in mind, it is clear why Israeli authorities are so concerned about the potential transfer of weaponized PBAs to Iranian proxies, especially when groups such as Hezbollah already have the delivery systems necessary to deploy such chemicals, including grenade launchers and mortars.

Conclusion

Back in 1998, the CIA assessed that the successful deployment of chemical weapons, combined with “the lack of meaningful international sanctions or condemnations” was the reason why Iran and other states believed they could acquire chemical weapons as a deterrent capability or force multiplier “without fear of repercussions.”58 Moreover, the CIA warned at the time, once a country acquires a chemical weapons capability, it is unlikely to willingly relinquish such a military tool, “especially in areas of frequent conflict such as the Middle East and Asia.”59

Fast forward 26 years and the same findings apply. In its 2024 annual threat assessment, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence warned that “Iranian military scientists have researched chemicals, toxins, and bioregulators, all of which have a wide range of sedation, dissociation, and amnestic incapacitating effects.”60 That research and development, the DNI added, is likely to continue and is intended “for offensive purposes.”61 All of which means that further coordinated multilateral and national-level actions will be necessary to counter Iran’s weaponized PBA program and disrupt the transfer of this dangerous category of weapons to Iran’s proxies and partners around the world.

And there are a variety of multinational fora for such engagement. For example, in late September 2024, on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly, senior government officials convened for the Summit of the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats. In his remarks, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken noted the threats posed by methamphetamines in Asia, Captagon in the Middle East, tramadol in Africa, and fentanyl in the United States.62 To this, the coalition should add the challenge of pharmaceutical-based agents, including but not limited to fentanyl-based chemicals, which presents more of a threat to international security than to public health. Against the backdrop of the targeted killing of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, the Israeli incursion into southern Lebanon to dismantle infrastructure intended to be used in an October 7-style cross border raid, and the Iranian ballistic missile attack against Israel on October 1, addressing Iranian support to its proxies is a priority concern. At a time of growing regional instability in the Middle East, largely the result of the militancy of Iranian proxies, the threats posed by Iran’s weaponized PBA program can no longer be overlooked. CTC

Dr. Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler fellow and director of the Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Levitt teaches at the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and has served both as a counterterrorism analyst with the FBI and as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis at the U.S. Treasury Department. An updated version of his book Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God was released in September 2024. He has written for CTC Sentinel since 2008. X: @Levitt_Matt

© 2024 Matthew Levitt

Citations

[1] “2023 Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC),” U.S. Department of State, April 18, 2023.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Matthew Miller, “United States Imposes Sanctions Targeting Iran’s Chemical Weapons Research and Development,” U.S. Department of State, July 12, 2024.

[4] “Treasury Designates Entity Subordinate to Iran’s Military Firm,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, December 3, 2020.

[5] “Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction.” U.S. Department of Defense, January 1, 2023.

[6] “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” Office of the Director of National Security, February 5, 2024.

[7] “2019 G7 Statement on Non-Proliferation and Disarmament,” G7, April 6, 2019.

[8] Author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024. See also Nick Waters, “Iraqi Protesters Are Being Killed By ‘Less Lethal’ Tear-Gas Rounds,” Bellingcat, November 12, 2019.

[9] Chloe Hadjimatheou, “Exclusive: Iran Believed to Be Developing Chemical Weapons, Decades after Publicly Giving Them Up,” Tortoise, May 28, 2024.

[10] “Herzog: Hezbollah Chiefs Were Meeting to Plan Oct. 7-Style Invasion When Killed,” Times of Israel, September 22, 2024; author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024.

[11] “Chemical Weapons: Status of Forensic Technologies and Challenges to Source Attribution,” Government Accountability Office, September 2023.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “2023 Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).”

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Golnaz Esfandiari, “Iran: ‘Forgotten Victims’ Of Saddam Hussein Era Await Justice,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, December 1, 2006.

[17] “Impact and Implications of Chemical Weapons Use in the Iran-Iraq War,” Director of Central Intelligence, August 10, 2010.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] “Unclassified Report to Congress on the Acquisition of Technology Relating to Weapons of Mass Destruction and Advanced Conventional Munitions,1 July Through 31 December 2001,” Central Intelligence Agency, n.d.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Erika Kinetz and Maria Danilova, “Lethal Chemical Now Used as a Drug Haunts Theater Hostages,” Associated Press, October 8, 2016.

[25] James R. Riches, Robert W. Read, Robin M. Black, Nicholas J. Cooper, and Christopher M. Timperley, “Analysis Clothing and Urine from Moscow Theatre Siege Casualties Reveals Carfentanil and Remfentanil Use,” Journal of Analytical Toxicology 36:9 (2012): pp. 647-656.

[26] “2023 Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).”

[27] Author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024. See also “2023 Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).”

[28] “Impact and Implications of Chemical Weapons Use in the Iran-Iraq War.”

[29] Author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024.

[30] Author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024.

[31] Waters.

[32] Author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024.

[33] Author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024.

[34] “Compliance with the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction Condition (10)(C) Report,” U.S. Department of State, March 2018.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “2019 G7 Statement on Non-Proliferation and Disarmament.”

[37] “Treasury Designates Entity Subordinate to Iran’s Military Firm.”

[38] Ibid.

[39] “Additional Sanctions Imposed by the Department of State Targeting Iranian Proliferators.” U.S. Department of State, August 29, 2014; Ronen Bergman and Farnaz Fassihi, “The Scientist and the A.I.-Assisted, Remote-Control Killing Machine,” New York Times, September 18, 2021.

[40] Ibid.

[41] “2023 Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).”

[42] Ibid.

[43] “Understanding Regarding the Aerosolized Use of Central Nervous System-Acting Chemicals for Law Enforcement Purposes,” Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Conference of the States Parties, December 1, 2021.

[44] “2023 Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).”

[45] “Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction.”

[46] Ibid.

[47] “Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).”

[48] Ibid.

[49] “Statement by Ms. Laura Gross, United States of America Representative to the OPWC, at the 105th Session of the Executive Council,” Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, March 2024.

[50] Miller.

[51] Ronen Bergman and Adam Goldman, “Israel Knew Hamas’s Attack Plan More Than a Year Ago,” New York Times, December 1, 2023.

[52] Colin Dwyer and Bill Chappell, “Israel’s Army Says It Found Tunnels Dug by Hezbollah Beneath the Border with Lebanon,” NPR, December 4, 2018.

[53] Matthew Levitt, “The War Hamas Always Wanted,” Foreign Affairs, October 11, 2023.

[54] Tal Beeri, “The Radwan Unit Is Capable of Carrying out an Invasion of the Galilee at Any given Moment,” Alma Research and Education Center, November 29, 2023.

[55] Assaf Orion, Hanin Ghaddar, Matthew Levitt, and Robert Satloff, “The Hamas-Israel War: End of the Beginning or Beginning of the End?” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 15, 2023.

[56] “Press Briefing by IDF Spokesperson RAdm. Daniel Hagari – September 20, 2024,” Israeli Defense Force, September 20, 2024.

[57] Author interview, Israeli defense officials, July 2024.

[58] “Impact and Implications of Chemical Weapons Use in the Iran-Iraq War.”

[59] Ibid.

[60] “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community.”

[61] Ibid.

[62] “Secretary Antony J. Blinken Introductory Remarks for President Biden at the Summit of the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats,” U.S. Department of State, September 24, 2024.

Skip to content

Skip to content