Abstract: On May 13, 2018, three churches in Surabaya, Indonesia, were targeted by suicide bombers comprising one single family of six. These are the first suicide bombings involving women and young children in Indonesia, thus marking a new modus operandi. They also show an increased capability among Indonesian Islamic State supporters when compared to previous attacks. But this increase is not necessarily indicative of a greater capacity across Indonesia’s pro-Islamic State network and the involvement of whole families reflects a broadening participation in Indonesian jihadism rather than a complete departure. The recent upsurge in violence is locally rooted, even if it is framed within the broader Islamic State ideology. The attacks also bring to the fore the role of family networks and the increased embrace of women and children in combat roles.

On Sunday, May 13, 2018, three churches in Surabaya (East Java), Indonesia, were targeted by almost simultaneous suicide bombings, killing 13 and wounding 41. According to Indonesian authorities, TATP (triacetone triperoxide) was used in all three bombings, and they were carried out by one family comprising Dita Oepriarto; his wife, Puji Kuswati; teenage sons, Yusuf Fadhil (18) and Firman Halim (15); and young daughters, Fadhila Sari (12) and Famela Rizqita (9). Later that day, a premature bomb explosion in a house in Sidarjo (near Surabaya), involving another family of six, injured the bomb maker Anton Febrianto and the two younger children, Farisa Putri (11) and Garida Huda Akbar (10), while killing his wife, Puspitasari, and the eldest son, Hilta Aulia Rahman (17). Febrianto was subsequently shot dead by the police.1 The following day, on Monday, May 14, a family of five rode two motorbikes to the entrance of Surabaya police headquarters where they blew themselves up. Four of the attackers were killed, and three police officers as well as three civilians were injured. The eight-year-old daughter of the suicide bombers, who had no explosives strapped to her, was flung off the motorbike and survived.2

This was the first successful series of Islamic State-inspired bombings in Indonesia since the January 2016 attack in Jakarta’s Thamrin business district, which had targeted a traffic police post and Starbucks café.3 It was also Indonesia’s first successful suicide bombing by a female and the first bombings carried out by whole families, including their young children. TATP, the explosives used in the three Surayba church attacks, is the same sensitive and tricky-to-make high explosive used in major attacks in Paris, Brussels, and Manchester between 2015 and 2017. These bombings indicate both an increase in the capability of Islamic State sympathizers in Indonesia as well as a new modus operandi. However, it would be wrong to assume that this increase in capability applies across Indonesia’s pro-Islamic State network and to see the involvement of whole families as a complete departure. It is equally incorrect to see this upsurge in Islamic State-inspired attacks as the result of returning Indonesian foreign fighters.

Returning Foreign Fighters?

The church bombings were quickly claimed by the Islamic State through its Amaq News Agency.4 Shortly thereafter, Indonesian police chief Tito Karnavian explained that one of the reasons for what he referred to as the activation of terrorist sleeper cells in Indonesia was the pressure on the Islamic State in the Middle East. The attacks by the Western coalition forces had cornered the Islamic State, he suggested, and compelled it to order all its cells everywhere to respond.5 The Indonesian police then asserted that the family responsible for the attacks had just returned from Syria.6 This allowed for the emergence of a false narrative that the renewed violence in Indonesia, as in parts of Europe, was the anticipated and feared consequence of returning foreign fighters. This narrative was further supported by inflated numbers of Indonesian returnees, which was put as high as 500 by some media sources.7

The returning foreign fighter narrative also seemed to explain why these families had been so much more competent in constructing the Islamic State signature TATP bombs than the numerous bomb makers in preceding years, whose bombs exploded only partially or not at all. The targeting of churches also seemed to mirror other Islamic State-inspired attacks on churches in Egypt and Pakistan in 2017.8 However, as more information about the family involved in the church bombings started to emerge, the Indonesian police retracted its claim that the family members were foreign fighter returnees from Syria.9 In fact, the family had never been to Syria. Neither had the family involved in the premature explosion in Sidoarjo nor the family responsible for the Surabaya police headquarters bombing.10

The Family Bombers

Little has been made public by investigators about the three families, although some information has become available on the church bombers who lived in a middle class neighborhood of Surabaya. Dita Oepriarto ran an herbal medicines business. The Facebook pictures of his wife Puji Kuswati showed a family not unlike other families with children at play, a family outing white water rafting, and get-togethers with female friends. The women have their heads covered in jilbabs (headscarves) in various colors and styles; their faces are unveiled.11 The Facebook posts stopped in 2014, possibly marking a point in the process of radicalization. Dita Oepriarto was described by neighbors who knew him as a “good person,” “friendly” and “refined.”12 A Christian neighbor said that there had been “nothing strange about the family” and that “they were like other devout Muslims.”13 A Muslim neighbor said that they prayed at an “unremarkable local mosque.”14 However, he also stated that he had heard from the older men in the community that Dita Oepriarto was not “mainstream” as he objected to “secular rituals,” including raising the Indonesian flag and “singing the Indonesian national anthem.”15 This resonates with comments made by classmates who stated that Dita Oepriarto never felt comfortable with the values advocated by Indonesia’s pluralistic state philosophy of pancasila,a which he believed should be opposed as it was not based on Islamic law.16

While it is still unclear how these three families met, it is known that they all attended pengajian (Islamic studies sessions) together every Sunday in Surabaya.17 Pengajian have been the most common path of radicalization as well as recruitment in Indonesia for all jihadi organizations, including the pro-Islamic State network.18 These specific, pro-Islamic State pengajian that the three families attended were held by ustadzb Khalid Abu Bakr, who already in the 1990s had a reputation as a firebrand cleric skilled at mobilizing Muslims to come to the defense of Islam. Contrary to some media reports, he was never a member of the Indonesian jihadi group Jemaah Islamiyah.19 After the declaration of the Islamic State caliphate in 2014, ustadz Khalid became an Islamic State sympathizer and decided to go on hijrah to Syria in 2016. However, he was arrested in Turkey and deported back to Indonesia in January 2017.20 It is then that, according to local Islamists, he started holding pro-Islamic State Islamic studies sessions and “started to gather ISIS sympathizers around him.”21 Whether or not ustadz Khalid is a formal member of the pro-Islamic State group Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) or is an off-structure pro-Islamic State cleric remains unclear so far. However, Indonesian police believe that church bomber Dita Oepriarto was not only a formal member of JAD but in fact headed the Surabaya cell of JAD to which the other two families are also believed to have belonged.22

The Pro-Islamic State Network in Indonesia

Indonesia’s pro-Islamic State network is extensive as it was grafted onto pre-existing jihadi organizations, including Negara Islam Indonesia (NII), Mujahidin Indonesia Timur (MIT), Tauhid wal Jihad, and Jemaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT), following the establishment of ISIS in the Middle East.23

In 2015, JAD was formed as an umbrella organization headed by Aman Abdurrahman, a radical preacher who had previously been involved in establishing a jihadi training camp in Aceh in 2010, for which he was sentenced to 15 years in prison on Nusakambangan Island. He was the leader of an amorphous group formed in 2004 that called itself Tawhid wal Jihad.c However, he is best known for his translation of the writings of the Jordanian hardline Salafi cleric Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi into Indonesian, and it is as an ideologue that Abdurrahman has been credited with “importing” and “indigenizing” the ideology of the Islamic State.24

JAD is territorially organized across Indonesia into wilaya (regions), branches, and cells. These include wilaya in Greater Jakarta (Jabodetabek), Banten, Central Java, East Java, West Java, Lampung, and Kalimantan as well as a cell in Toli Toli (Sulawesi) and a self-affiliated cell in Medan (Sumatra).25 It is a hierarchical organization in the sense that it is headed by an amir and has command structures at the local level. At the same time, it is also a loose organization that allows branches, cells, and individuals to operate independently from each other. While some directives for operations between 2016 and 2018 have come directly from imprisoned JAD leaders, often relayed through prison visitors, many attacks have been conceived ad hoc at the local level.26 What ties them together is a standardized ideological curriculum used in Islamic studies sessions,27 including online pengajian groups as well as the shared compendium of bomb-making instructions, which includes the tried and tested pressure cooker bomb instructions from AQAP’s Inspire magazine, the TATP instructions circulated by the Islamic State, and various instructions disseminated by Bahrun Naim (including some for a dirty bomb).28 With respect to the latter, local expertise has determined the degree of capability. Whether a bomb exploded and how much damage it caused was a reflection of the individual bomb maker’s skills, access to materials, and instructions chosen. Thus, while the Surabaya bombs showed a greater capacity than previous JAD bombs, this does not necessarily mean JAD as a whole has increased its military capacity.

JAD is by far the largest and most defining group in Indonesia’s pro-Islamic State network, which also includes the much smaller Katibul Iman—sometimes referred to as Jemaah Ansharut Khilafah (JAK), led by Abu Husna—as well as the Poso-based Mujahidin Indonesia Timor (MIT) until the death of its leader Santoso, alias Abu Wardah, in July 2016.29 As a whole, these groups have pursued the local aims of establishing sharia law and Islamic governance in Indonesia. Seeing the Indonesian government, Indonesia’s pluralistic nationalist ideology of pancasila, and the police as institutionalized idolatry as well as being the main obstacles to achieving an Islamic Indonesia, Islamic State supporters regard the police and the government as the main targets of their violence. Religious minorities such as Christians and Buddhists have also been attacked in the broader context of waging war on all forms of ‘unbelief.’ It is here where the church bombings fit in.

While the focus of the Indonesian pro-Islamic State network has been domestic, some Indonesian Islamic State supporters also went to the southern Philippines to participate in the battle of Marawi in 2017.30 However, the primary foreign link has been with the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. Here, JAD, Katibul Iman/JAK, and MIT had separate connections to the key Indonesian leaders in Syria: Bahrumsyah, the commander of the Indonesian-Malay Katibah Nusantara; Abu Jandal, the former leader of Katibah Masyaariq who was killed in November 2016; Abu Walid, who is believed to be closely connected to the Islamic State’s central leadership; and Bahrun Naim, who until his death in November 2017 functioned as recruiter for amaliyat (jihadi military operations) in Indonesia.31

Indonesian counterterrorism data shows that 779 Indonesians went to Syria and Iraq between 2012 and 2018. Of these, 103 are known to have been killed. Some 539 Indonesians tried to go to Syria but were deported, mostly from Turkey.d Another 171 had plans to go but were stopped while still in Indonesia or are currently under surveillance.32 The vast majority of these were recruited through Islamic studies sessions and facilitated by groups in Indonesia’s pro-Islamic State network.33 In January 2016, political analyst Sidney Jones estimated that 45 percent of the Indonesians who went to Syria “were women and children, and not all the adult males were fighters.”34 Many were families who went to live in the caliphate, selling all their possessions to get there, without the intention of returning. This, rather than the narrative of returning foreign fighters, is borne out by Indonesian counterterrorism data, which shows only 86 of those who went to Syria and Iraq have returned to Indonesia.35

The relationship between the pro-Islamic State network in Indonesia and Indonesians within the Islamic State in Syria as well as the Islamic State more generally is a complex one that reflects the ‘glocal’ nature of the Islamic State phenomenon in Indonesia.36 The Islamic State has provided inspiration, ideological justification, and a global narrative in which the local Indonesian narrative is situated. It has also repeatedly issued instructions to the ummah (community) more broadly to carry out attacks. Before the death of Bahrun Naim, there were direct instructions for attacks from Indonesians in Syria such as the instructions to attack a police station, a temple, and church on August 17, 2015, in Solo, the planned attacks on New Year’s Eve of 2015,37 and the planned attack on the presidential palace on December 11, 2016, by what would have been Indonesia’s first female suicide bomber, Dian Yulia Novi.38 Moreover, the Islamic State has sent money to some pro-Islamic State groups in Indonesia such as MIT to purchase weapons.39 At the same time, however, the attacks by the pro-Islamic State network in Indonesia are firmly anchored in the local context, drawing upon local grievances, feeding off local debates on what it means to be a good Muslim, and pursuing the same local aims as well as striking at the same local targets as Indonesian jihadi organizations such as Jemaah Islamiyah and Darul Islam had before them.40

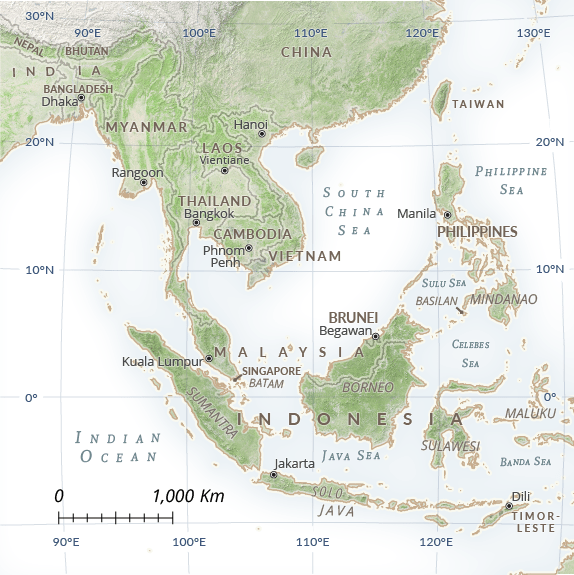

Southeast Asia (Rowan Technology)

Glocal Dynamics

Indonesian police chief Tito Karnavian, in his explanation of the motives behind the Surabaya church bombings, stated that at the local level these attacks were connected to the 2017 re-arrest of JAD leader Aman Abdurrahman,41 who is currently on trial in Jakarta for his alleged involvement in the January 2016 Jakarta attack.42

The church bombings coincidentally marked the peak of an upsurge in local violence. This violence started with a riot of Islamist detainees in the headquarters of the mobile police (Brimob) in Kelapa Dua, Jakarta, on Wednesday, May 8. The riot was ostensibly triggered by one of the inmates not receiving the food his wife had sent. The prisoners killed five police officers and took others hostage, all of whom were eventually released. They also posted pictures of the riots on Instagram and used social media to call for reinforcements. After the police regained control on May 10, during which one inmate was shot and killed, 155 prisoners were transferred to the maximum-security prison on Nusakambangan Island.43

This prison riot, which was not JAD-led or -directed, was followed by further violent actions against the police.44 On May 11, a Brimob officer was stabbed by a suspected Islamist extremist near the Brimob headquarters. On May 12, two women, who are believed to have been responding to the appeal for reinforcements, were arrested on their way to Brimob headquarters with scissors with which they planned to stab an official. On May 13—the day of the church bombings and the premature explosion in Sidoarjo—four alleged members of JAD were shot dead by the police in Cianjur. Two other members of this cell were arrested.45 They had been planning to attack police stations in Jakarta and Bandung, including the Brimob headquarters.46 On May 14, a family drove on two motorbikes to the gate of Surabaya police headquarters where they blew themselves up. On May 16, four men attacked police officers with swords—killing one—after crashing their car into the gate of the provincial police headquarters in Pekanbaru, Riau.47

Some analysts have incorrectly linked the Surabaya church bombings to the prison riot at Brimob headquarters, pointing to a call to jihad that went out to JAD members through social media on May 9 asking them to help the prisoners by attacking the police, non-Muslim houses of worship, crowded places, and places where heretics gather.48 On Telegram, in particular, members of pro-Islamic State chat groups were exhorted to “Support in your own cities the mujahedeen who caused the riot! Burn the assets of nonbelievers, idolaters, apostates and hypocrites!”49

The Surabaya bombings, however, were not directly linked to the prison riot. According to information from within Indonesian jihadi circles, they had been in the making for much longer, already planned before the prison riot broke out.50 Counterterrorism expert Harits Abu Ulya has posited that the Surabaya bombings were motivated by revenge against the Indonesian police, who were responsible for the many arrests of Islamic State supporters since January 2016. They were also an attempt to demonstrate that the Islamic State in Indonesia was alive and well.51 Similarly, political analyst Sidney Jones has argued that the family bombings could be viewed as “an effort to keep motivation high precisely because recruitment is declining.” She has further suggested that “now that their energies are no longer focused on getting to Syria, the Islamic State’s supporters in Indonesia may be turning their attention back to waging war at home.”52 The Surabaya bombings could thus mark the beginning of more violence in Indonesia.

The then impending month of Ramadan may also have played a role in the timing of this violence. Jihadi organizations have often marked Ramadan with a campaign of violence, spurred by the belief that the rewards are greater and that the path to paradise for those martyred is easier and faster. The Islamic State has followed this pattern with its late spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani calling for attacks during the Islamic holy month in 2015 and urging Muslims “to make it a month of calamity for non-believers” in 2016.53 However, there was already a tradition of attacks during Ramadan among Indonesian jihadis that clearly predated the Islamic State. This was most obvious during the 1998-2007 conflict in Poso, Central Sulawesi, where attacks were regularly launched during Ramadan in order to ensure success and secure ‘greater rewards.’54 The most shocking of these was the beheading of four Christian school girls in 2005, whose heads were then presented as Lebaran (Eid al-Fitr) ‘gifts.’55 Attacks on churches also have a history in Indonesia that predates the Islamic State. On Christmas Eve 2000, churches in 11 cities were targeted in near simultaneous bombings. Churches were also destroyed by Muslims during the communal conflicts in Ambon and Poso.

The motive for the Surabaya church bombings was explained in issue 10 of the relaunched Al-Fatihin online magazine. Al-Fatihin was first published during Ramadan 2016 as a newsletter of the Malay-speaking muhajirin (emigrants) to the Islamic State.56 In this form, it only ever had one edition. On March 5, 2018, possibly as indication of the increased JAD activity to come, it was relaunched as a more local, Indonesia-only but still Islamic State-affiliated, now weekly online publication. Issue 10 of Al-Fatihin magazine appeared the day after the church bombings and the bombings featured as the main article under the title “Kill the idolaters wherever they are.” It took obvious pride in the capability of the ‘soldiers of the caliphate,’ highlighting the three ways these bombings were carried out: by motorcycle, explosive vest, and car. It argued that the differentiation between civilian and military was an incorrect understanding of Islam.57 It then discussed at length and in detail the targeting of “kafir Christians” who were performing idolatrous rituals at the time of the bombings. The article asserted that the blood of kafir is halal and that Islam only differentiates between believers and unbelievers, the latter including any Muslim who violates any of the “Ten Nullifiers of Islam” and anyone who defies the word of Allah.58 The reason for the Surabaya attacks was to wipe out unbelief, idolatry, and defiance of the word of Allah.59

The Widening Participation in Jihad

The Surabaya bombings saw the coming together of three different recent trends in jihadism, in particular in Islamic State-directed or -inspired attacks. These trends are an increased reliance on family or kinship networks, a recent embrace of the participation of women in attacks, and an increase in the use of children. These increases are not coincidental but, as Mohammed Hafez has pointed out, a recruitment strategy involving kinship radicalization. This strategy provides that extra layer of security as “political ideas are infused with emotional commitments” and “narrative fidelity is enhanced by actual brotherly fidelity.”60 In Indonesia, suicide bombings carried out by whole families including young children are a new modus operandi. They have been explained by the family wanting to go to paradise together.61 However, the involvement of families in amaliyat (jihadi military operations) in Indonesia itself is not new.62 The perpetrators of the 2002 Bali bombings included brothers Ali Ghufron, Amrozi, and Ali Imron. The 2009 Marriot hotel bombing included members of the extended family of Saifuddin Zuhri. Unlike the Surabaya bombings, these bombings were male only. Women in Indonesian jihadi organizations had far more traditional roles, such as wives, mothers, and teachers, but were no less important in tying together and consolidating the organization.63

This does not mean, however, that Indonesian women were not interested in pushing the boundaries of their roles. The emergence of the Islamic State provided Muslim women globally with the means to play a more active role.64 The recruitment of females by the Islamic State in order to populate its caliphate, its establishment of the Al-Khansa Brigade, and the use of social media, which leveled the playing field without violating gender separation, allowed women to push the boundaries from muhajirat (female emigrants) to mujahidat (female fighters), despite initial opposition from the Islamic State toward women combatants.65

The Islamic State’s position started to shift in late 2016. Indeed, in December, Al-Naba, the Islamic State’s newsletter, included an article stating that while jihad was not an obligation for women, “if the enemy enters her abode, jihad is just as necessary for her as for the man.”66 Battlefield evidence of this shift started to emerge in early July 2017 during the battle for Mosul when a woman carrying a baby walked up to Iraqi soldiers and reportedly detonated the explosives she was carrying. By mid-July, more than 30 women are believed to have been involved in martyrdom operations.67 This shift was confirmed in the July 2017 edition of Rumiyah magazine, which called upon women to follow the example of Umm ‘Amara, who together with four other women had militarily defended the Prophet Muhammad at the Battle of Uhud.68 In October 2017, the Islamic State called upon women to take up arms and to launch terror attacks, declaring it an obligation.69

Female Indonesian Islamic State supporters had already been pushing the boundaries considerably.70 They were very active on social media, organizing groups as well as encouraging and even recruiting men for jihad. Several played key roles in persuading their families to go to Syria. A small number joined MIT as combatants in the Poso Mountains. Some helped their husbands make bombs. And others volunteered to be suicide bombers.71 The latter included Dian Yulia Novi who in her deposition stated that she had wanted to carry out a martyrdom operation ever since she started learning about the Islamic State in 2015 through social media.72 If she had not been arrested in December 2016, she would have been Indonesia’s first female suicide bomber.

Male children have also featured regularly as Islamic State combatants, even before women joined their ranks. Indeed, Mia Bloom, John Horgan, and Charlie Winter looking at data from January 2015 to January 2016 concluded that “the use of children and youth has been normalized under the Islamic State” and that they were used in the same way that male adults would, without consideration to their age.73 This explains why the article in Al-Fatihin did not pay special attention to the fact that whole families including young children had carried out the Surabaya bombings. They were all equally ‘soldiers of the caliphate.’

Indonesian children have been part and parcel of the Islamic State project, but until the Surabaya bombings, this participation was restricted to those in Syria and Iraq. Indonesian children joined the hijrah as part of their families; Indonesian boys participated in military training as could be seen on Islamic State videos; and at least one of the boys, Hatf (12), who had gone to Syria in 2016, is known to have “died in combat with a French ISIS unit two months short of his 13th birthday.”74

Conclusion

For Islamic State supporters in Indonesia rather than in Syria, carrying out amaliyat was a way to connect with the broader Islamic State community without having to travel to the Middle East but also to connect with the dispersed pro-Islamic State community across Indonesia. Indonesian mujahidat, of course, served an additional tactical purpose as exemplified by the repeated attempts of Bahrun Naim, from his base in Syria, to recruit akhwat (sisters) for amaliyat—including instructing Dian Yulia Novi to attack the presidential palace in December 2016. He saw the use of akhwat as a way to overcome the lack of success in attacks in Indonesia in 2016 and 2017; akhwat would be able to avoid detection more easily.75 Using families for suicide bombings provides a similar tactical advantage, and becoming a mujahidin family provides a similar sense of belonging to both the broader Islamic State community and the Indonesian pro-Islamic State community. The Surabaya family bombings also exemplify the ever-broadening participation in jihad in Indonesia and the shift in jihadism more generally from the exclusive vanguard model to a more populist endeavor. It is thus unlikely that they will remain a one-off.

The push by Indonesian women to be more involved in jihadism combined with the Islamic State’s position that age and now gender are not a barrier to becoming a ‘soldier of the caliphate,’ suggest that it is likely that there will be further amaliyat by Indonesian women. Moreover, the fact that for the pro-Islamic State network in Indonesia the struggle has always been about making the local environment more ‘Islamic’ and targeting those who it believed to be an obstacle to this aim, means that Islamist violence will most likely persist. Such violence will continue to be driven by distinctly local developments. In the next year, three stand out. The first is the fate of JAD leader Aman Abdurrahman, currently on trial in Jakarta, with prosecutors seeking the death penalty. The second is the new counterterrorism legislation, which was passed in the wake of the Surabaya bombings after being under discussion in parliament for more than a year. This will undoubtedly result in further arrests of JAD members, thereby making the police even more of a target of revenge attacks. The third is the Indonesian presidential election in 2019, which pro-Islamic State Indonesian militants may seek to exploit by placing further strains on Christian-Muslim relations or by targeting the ‘kafir democracy.’

The final factor to take into consideration is the return of Indonesian foreign fighters from Syria and Iraq. As many Indonesians went to live rather than to fight in the Islamic State caliphate, analysts such as Solahudin have suggested that most have no intention of returning.76 That seems to be borne out by the current numbers. Only 86 Indonesians have returned so far, and none of those who joined the Islamic State have been involved in violence in Indonesia. Only one of these 86 perpetrated an attack on a police officer at North Sumatra police headquarters in Medan in June 2017. And he had spent six months training in Syria with the Free Syrian Army (FSA).77 While the data on Indonesians who have returned from Syria to Indonesia currently does not give credence to the narrative on the threat emanating from returning foreign fighters, that does not mean that the possibility of such a threat can be completely ruled out. Indeed, only a few highly skilled explosive trainers returning from Syria could make a great difference to JAD’s capabilities. CTC

Dr. Kirsten E. Schulze is an associate professor in international history at the London School of Economics and an associate of the LSE Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre.

Substantive Notes

[a] Pancasila is Indonesia’s state philosophy based on five principles: belief in one God, nationalism, humanism, democracy, and social justice.

[b] Ustadz is an honorific title for a teacher of Islam.

[c] Abdurrahman continued to lead Tawhid wal Jihad and to translate jihadi material from Arabic to Indonesian while in prison. He maintained a website until recently.

[d] This 539 figure is a distinct number. Deportees are counted separately as they did not make it to Syria or Iraq.

Citations

[1] “Sidoarjo bomb also involved family of six: E. Java Police,” Jakarta Post, 14 May 14, 2018.

[4] Amaq, May 13, 2018.

[5] Rita Ayuningtyas, “Ini Motif Bom Gereja Surabaya Versi Kapolri,” liputan6.com, May 13, 2018.

[6] “Pelaku Bom Surabaya Baru Pulang dari Suriah,” Fajar Online, May 14, 2018.

[8] See, for example, Adham Youssef, “Gunman launches deadly attack on Coptic church near Cairo,” Guardian, December 29, 2017. See also “Pakistani Christians bury 11 after ISIS attacks Methodist church,” Christianity Today, December 19, 2017.

[10] Information obtained by the author, spring 2018.

[11] Puji Kuswati’s Facebook profile, which has since been taken down.

[12] “Keluarga Dita Oepriarto, Potret Bomber Surabaya di Mata Tetangga,” tirto.id, May 15, 2018.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Noor Huda Ismail, “Ideologi Kematian Keluarga Teroris,” CNN Indonesia, May 15, 2018.

[18] Julie Chernov-Hwang and Kirsten E. Schulze, “Why they join: Pathways into Indonesian Jihadi Organizations,” Terrorism and Political Violence (forthcoming 2018).

[19] Author communication, former member of the JI markaziyah, May 2018.

[20] Sidney Jones, “How ISIS Has Changed Terrorism in Indonesia,” New York Times, May 22, 2018.

[21] Author communication, Indonesian Islamist in the Surabaya area, May 2018.

[23] For a comprehensive analysis, see “The Evolution of ISIS in Indonesia,” IPAC Report 13:24 (2014). See also “Disunity among Indonesian ISIS Supporters and the Risk of More Violence,” IPAC Report 25:1 (2016).

[25] Ibid.

[26] Information obtained by the author.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Tom Allard and Agustinus Bea De Costa, “Exclusive: Indonesian militants planned ‘dirty bomb’ attack – sources,” Reuters, August 25, 2017.

[29] “Indonesia’s most wanted militant ‘killed in shoot-out,’” Guardian, July 19, 2016.

[30] For detailed analysis, see “Marawi, the ‘East Asia Wilaya,’ and Indonesia,” IPAC Report 38:21 (2017).

[31] Schulze and Liow.

[32] Brig-Gen (police) Marthinus Hukom, “Dinamika Teror Terkini” presentation at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Jakarta, May 21, 2018.

[33] Schulze and Liow. See also Chernov-Hwang and Schulze.

[34] Sidney Jones, “Understanding the ISIS threat in Southeast Asia,” presented at ISEAS Region Forum, January 3, 2016, p. 1.

[35] Hukom.

[36] For further discussion, see Schulze and Liow. See also Kirsten E. Schulze and Julie Chernow-Hwang, “From Afghanistan to Syria: How the global remains local for Indonesian Islamist militants” in Tom Smith and Kirsten E. Schulze eds., Exporting Global Jihad (London: IB Tauris, 2019).

[37] Schulze, “The Jakarta Attack and the Islamic State Threat to Indonesia,” p. 30; “Disunity among Indonesian ISIS Supporters and the Risk of More Violence,” p. 8.

[38] Deposition of Dian Yulia Novi, Badan Acara Pemeriksaan (BAP) Dian Yulia Novi alias Dian alias Ukhti alias Ayatul Nissa Binti Asnawi, December 16, 2016.

[39] “Disunity among Indonesian ISIS Supporters and the Risk of More Violence,” p. 1.

[40] Schulze and Chernov-Hwang.

[41] Ayuningtyas.

[42] Kanupriya Kapoor, “Indonesian court indicts cleric accused of masterminding attacks,” Reuters, February 15, 2018. See also Karuni Rompies, “Indonesia seeks death penalty for JAD leader Aman Abdurrahman,” Sydney Morning Herald, May 18, 2018.

[43] Fitra Moerat Ramadhan, “Kerusuhan setelah magrib di Mako Brimob,” Tempo, May 12, 2018.

[44] Information obtained by the author, May 2018.

[45] “Terduga Teroris di Cianjur Termasuk Kelompok JAD,” Republika, May 13, 2018.

[47] Wahyudi Soeriaaatmadja, “4 men attack Riau provincial police headquarters using swords, killing one police officer,” Straits Times, May 16, 2018.

[48] Zahrul Darmawan, “Pengamat: Teror Masih Berlanjut, ISIS Sebar Undangan Jihad,” Viva News, May 13, 2018. See also Amindoni.

[49] Quoted in Jones, “How ISIS Has Changed Terrorism in Indonesia.”

[50] Author communication, several Indonesian jihadi sources, May 2018.

[51] Harits Abu Ulya, “Bom Surabaya, Antara Dendam dan Pembuktian Eksistensi ISIS,” Kompas, May 14, 2018.

[52] Jones, “How ISIS Has Changed Terrorism in Indonesia.”

[54] “Napak Tilas Jihad di Bulan Suci,” BUNYAN, December 2001, pp. 11-16.

[55] Stephen Fitzpartick, “Beheaded girls were Ramadan ‘trophies,’” Australian, November 9, 2006.

[56] Al-Fatihin, edisi 1, Ramadhan 1437.

[57] “Bunulah Kaum Musyrikin Dima Saja Berada,” Al-Fatihin, edisi 10, p. 1 and continued on pp. 7-10.

[58] Ibid., p. 8.

[59] Ibid., p. 9.

[61] La Batu.

[62] Sulastri Osman, “Jemaah Islamiyah: Of Kin and Kind,” Journal of Current Southeast Asia 29:2 (2010).

[63] For a more detailed discussion, see Ibid.

[64] For a more detailed discussion, see Anita Peresin and Alberto Cevone, “The Western Muhajirat of ISIS,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 38:7 (2015). See also Debangana Chatterjee, “Gendering ISIS and Mapping the Role of Women,” Contemporary Review of the Middle East 3:2 (2016).

[65] For a more detailed discussion, see Charlie Winter and Devorah Margolin, “The Mujahidat Dilemma: Female Combatants and the Islamic State,” CTC Sentinel 10:7 (2017).

[66] “I will die while Islam while Islam is Glorious,” Al-Naba, Issue LIX, Central Media Diwan, December 12, 2016, as translated by Charlie Winters and cited in Winters and Margolin.

[68] “Our Journey to Allah,” Rumiyah, Issue 11 (Shawwal 1438/July 13, 2017), p. 15.

[69] Charlie Winter, “1. Big news: the latest issue of #IS’s newspaper features an unambiguous call to arms directed at female supporters,” Twitter, October 5, 2017. See also Lizzie Dearden, “ISIS calls on women to fight and launch terror attacks for the first time,” Independent, October 6, 2017.

[70] For a comprehensive discussion, see “Mothers to Bombers: the Evolution of Indonesian Women Extremists,” IPAC Report 35 (2017). See also Nava Nuraniyah, “Not just brainwashed: understanding the radicalization of Indonesian female supporters of the Islamic State,” Terrorism and Political Violence (forthcoming 2018).

[71] Ibid.

[72] Deposition of Dian Yulia Novi, Badan Acara Pemeriksaan (BAP) Dian Yulia Novi alias Dian alias Ukhti alias Ayatul Nissa Binti Asnawi, December 16, 2016.

[74] Sidney Jones, “Surabaya and the ISIS family,” Interpreter, May 15, 2018.

[75] Author interview, person close to Bahrun Naim, August 2017.

[76] Solahudin, “How dangerous are Indonesian returnees and deportees,” presentation at LSE, January 19, 2018.

Skip to content

Skip to content