The Arabic language version of this article is available here.

Abstract: In October 2019, the Islamic State announced its new leader as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurashi. The U.S. government has publicly designated and named this individual as Amir Muhammad Sa’id ‘Abd-al-Rahman al-Mawla. Although a few details have emerged about al-Mawla, very little is known about his history and involvement in the Iraqi insurgency. Using three declassified interrogation reports from early 2008, when al-Mawla was detained by U.S. military forces in Iraq, this article provides more insights into his early background. This examination shows that some of the current assumptions about al-Mawla are on tenuous ground, but also provides a unique window into what al-Mawla revealed about his fellow fighters during his time in custody.

Leadership transitions in any organization can produce uncertainty and invite speculation regarding the organization’s future trajectory. This dynamic is especially the case in clandestine terrorist organizations, in which the desire to publicize continuity of purpose and the qualifications of the incoming leader must be balanced with the need to maintain secrecy. For the group known as the Islamic State, this balancing act was of the utmost importance given the fact that on October 26, 2019, the group’s previous leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had been killed in a raid by U.S. military forces and the overall organization was merely a shadow of what it had been during the organization’s highwater mark in the summer of 2015.

Thus, when the group announced the appointment of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurashi as “commander of the believers and caliph of the Muslims” on October 31, 2019, it had to anticipate that its new leader would be under intense scrutiny and face a series of daunting challenges in an organization that, while still maintaining the capability to carry out serious operations, was also consistently being targeted by hostile forces, both from the outside but also from the inside as well.1 The Islamic State did not have to wait long to see the criticism come to fruition. Merely a few days following the announcement of al-Qurashi’s appointment as leader of the Islamic State, essays critical of the new leader began to circulate online among verified channels of Islamic State supporters. Among other critiques, these essays attacked the relative anonymity of al-Qurashi, referring to him as the “secluded paper caliph” and “an unknown nobody.”2 Such critiques were deflected by other Islamic State supporters, who argued that more knowledge of al-Qurashi was neither necessary from a legal perspective nor advisable from a security one.3

This lack of information from the group, which it had previously given prior to al-Baghdadi’s elevation, led to questions regarding who was actually at the head of the organization.a As a result, although several sources commented on different possibilities, confirmation from the U.S. government was not immediately forthcoming.4 b Then, on March 17, 2020, the U.S. government issued its perspective on the issue when it designated an individual by the name of Amir Muhammad Sa’id ‘Abd-al-Rahman al-Mawlac as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist, indicating that he has “succeeded [al-Baghdadi] to become the leader of ISIS.”5 Al-Mawla had been one of the individuals previously tagged as a possible successor, although at least one insider suggested he was “lower in rank in the administration as well as finance and military leadership.”6

Operating under the assumption that al-Qurashi is al-Mawla, which the authors are highly confident he is, the purpose of this article is to introduce documents that offer a unique vantage point on the contentious issue of the history of the presumed leader of the Islamic State. The source of this distinct perspective is a small sample of typed summaries of al-Mawla’s own words while being detained and interrogated by U.S. military forces in 2008. These three summaries, known as Tactical Interrogation Reports (TIRs), provide an inside look at how al-Mawla framed his own experience in joining and participating in the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). The TIRs present a view of al-Mawla as a religious scholard who also demonstrated political savvy, which during the course of his interrogation appears to have included a willingness to adjust to changing circumstances, even if that required providing information about his jihadi colleagues. This article, together with the accompanying discussion in this issue featuring analysis by a group of scholars regarding these TIRs,7 forms an important lens through which scholars, policymakers, and practitioners can understand al-Mawla’s personality and background.

In what follows, the authors offer brief contextual comments regarding the documents that form the basis for the subsequent analysis. Because of the unique nature of these documents, which are being released by the Combating Terrorism Center,8 this context is critical to understanding what they can and cannot reveal. Following this discussion, the article examines the content of the TIRs by focusing on what they reveal about al-Mawla’s own biography and what they reveal regarding his willingness to speak about his colleagues in ISI. Finally, the article concludes by discussing the importance of continued research and release of similar materials for our understanding of militant groups.

What Are Tactical Interrogation Reports?

Tactical Interrogation Reports (TIRs) are part of the paper trail the U.S. military creates when alleged enemy combatants are detained and interrogated in the course of military operations. TIRs seek to document the information that emerges during an interrogation, detailing everything from biographical information about the detainee to notes on their position within a network, and knowledge about their organization’s members and capabilities. In real time, TIRs can help inform intelligence by revealing new information, corroborating other sources, or highlighting inconsistencies among different accounts.

TIRs can be useful for the reasons detailed above, but since they are part of the detention and interrogation process in Iraq, it is vital to note some important considerations. First, the timing and conditions of TIRs matter because they pertain to when, how, and where a detainee is debriefed.e Second, these factors can shape the outcome of the interrogation and thus, the content documented in the TIRs. Third, because of how TIRs are produced,f what appears in the TIR should not be seen as a verbatim quote of what the detainee said, but rather as the gist of a conversation where the goal was to preserve the substance of the dialogue, but not necessarily the specific verbiage. Due to the importance of these considerations, the authors will describe the timing and conditions of al-Mawla’s TIRs, and will speak to how such factors might shape interpretation and analysis of the documents.

This article is based on an analysis of a small sample of three TIRs created during al-Mawla’s interrogation when he was detained by U.S. military forces in Iraq. It is extremely important for readers to note that this article uses only three TIRs, whereas the total number of TIRs composed for al-Mawla is approximately 66.9 Using such a small number of documents is not optimal. However, in deciding to write this article using only three TIRs, the authors had to strike a delicate balance. The authors did not control, or play a role in, the process whereby these TIRs were selected. These documents were provided to the CTC so they could be studied and shared.

Although the authors believe that having all the TIRs available is the best approach and continue to advocate that the rest of the TIRs be released, ultimately the authors elected to continue with the analysis, recognizing that there are more TIRs that will hopefully come out and allow for additional analysis.g Thus, any conclusions here are preliminary in nature and should be interpreted in that light. The three TIRs, referred to with capital letters for purposes of this article, are briefly summarized below:

- TIR A – This TIR is dated January 8, 2008, and a time of 0137C.h This TIR is the first of the three and the session it represents took place approximately two days after al-Mawla’s capture. In it, al-Mawla describes some of the basic details of his reasons for joining ISI, in addition to identifying several people that he knew within ISI.

- TIR B – This TIR has a date of January 25, 2008, and a time of 1430C.i TIR B reads more as an affidavit, as the language in the TIR suggests that it is being made in the presence of or written specifically for some sort of legal official. It contains brief summaries of al-Mawla’s identification of approximately 20 individuals within ISI along with seven pieces of SSE (sensitive site exploitation), likely material found in his possession or in his location at the time of his detention.

- TIR C – This TIR has a date of January 25, 2008, and a time of 1430C.j It appears to be a summary of al-Mawla’s early introduction and rise through the ranks of ISI in Mosul. It also contains brief synopses of several legal rulings in which al-Mawla participated and of ISI activities of which he had knowledge.

The interpretation of these TIRs is not only contingent on their timing, but also on at least two other factors: the treatment of the detainee and the validity of statements made by the detainee in interrogation sessions.

Interrogations generally occur in adversarial conditions. The authors considered the nature of al-Mawla’s interrogations before deciding to proceed with the analysis of these documents. In the specific case of al-Mawla, there are several reasons to believe that no mistreatment occurred during his detention in 2008.

First, the Abu Ghraib scandal caused significant reforms to U.S. detention policies and the treatment of prisoners in Iraq.10 In June 2008, not long after the interrogation sessions discussed in this article, a New York Times journalist reported after a visit to Camp Bucca and Camp Cropper that conditions there had improved, riots by prisoners were down, a system of hearings to facilitate the release of incorrectly captured individuals had been implemented, and that human rights advocates agreed that conditions generally had improved, albeit still with challenges.11 k Second, the revised September 2006 Army Field Manual 2-22.3 on “Human Intelligence Collector Operations,” which governed interrogation rules during the time of al-Mawla’s interrogation, included increased emphasis on the prohibition of the use of “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”12 Thirdly, the TIRs themselves contain no indications of mistreatment or abuse. Finally, the authors sought and obtained assurances from the U.S. government that al-Mawla had not been mistreated. While not sufficient alone, these assurances, combined with the other reasons noted above, form the basis for the willingness to consider this material. However, the authors acknowledge that the use of this type of material in future research raises important moral and ethical questions that require additional attention.

Another challenge with using TIRs for analytic purposes is that it is incredibly difficult to ascertain whether what al-Mawla divulges regarding himself or ISI as an organization is true. Any interrogation is, by definition, an adversarial process where the incentives of both parties typically are not aligned toward a common outcome. The interrogator is seeking facts, while the detainee may be trying to minimize their involvement in illegal activities, distract the interrogator with lies or half-truths, and protect others within the organization. In short, neither can the truth of what is said be unreservedly accepted, nor can it be entirely discarded simply because some fabrications likely exist within the material.

While it is impossible to fully resolve this concern, there are at least two ways in which the authors attempt to mitigate it in this analysis. The first is to examine the nature of the material on its face. If a claim being made by al-Mawla seems so outlandish that it is likely false, the weight given to that statement may need to be significantly discounted. The second form of mitigation is to engage in different types of cross-checking of the material contained in the TIRs. In this regard, the fact that there is an approximately two-and-a-half-week gap between the first and last two of the three TIRs being released is helpful. If al-Mawla changed or omitted certain statements from one TIR to the next, even though he discussed similar topics, it may indicate a need to be cautious in giving credence to those statements. It could also mean that he regretted making the statements and wanted to avoid talking about them again. In addition to internal cross-checking of the TIRs themselves, the authors attempted wherever possible to verify the information provided in the TIRs with external sources, as well as through engagement with other scholars in the field.

In sum, these three TIRs contain potentially valuable information to enhance the public’s understanding of al-Mawla. This is not to say that the analysis that follows is conclusive or without challenges. Such information represents only one perspective and should be considered in light of other information and material. Indeed, any type of data presents potential biases that should be mitigated to the extent possible and include the appropriate caveats. In what follows, the authors attempt to follow the approach outlined above while also seeking to examine potential insights emerging from these TIRs in an effort to better understand who al-Mawla is.

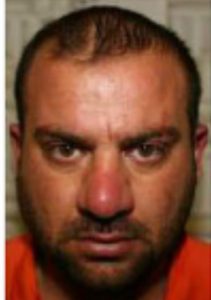

(Rewards for Justice)

“Talking” with al-Mawla

Details about the operation resulting in al-Mawla’s capture are limited, but al-Mawla’s TIR does reveal that he was captured on January 6, 2008, at around 1:37am local time in Iraq.l The following day, a press release from U.S. Central Command noted that operations in Mosul had resulted in the capture of “a wanted individual believed to be the deputy al-Qaeda in Iraq leader for the network operating in the city.”13 The press release also stated that the individual had “previously served as a judge of an illegal court system involved in ordering and approving abductions and executions.”14 Although the press release does not explicitly name the individual described in the TIR used in this article, it contains several pieces of information which mirrored what al-Mawla would tell interrogators after his capture: his prior role in ISI’s judicial system, his participation in kidnappings and murders, and his leadership position in Mosul.

The timing of al-Mawla’s capture raises an interesting question regarding al-Mawla’s biography. Some open-source reporting has claimed that al-Mawla crossed paths with future Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Camp Bucca in 2004.15 In some cases, this overlapping time period seems to be used to buttress al-Mawla’s legitimacy, suggesting that he had very early connections to the rest of the Islamic State’s future leadership and formed a key part of the Camp Bucca radicalization hub.16 However, given that the TIRs list January 2008 as al-Mawla’s date of detention, this chronological discrepancy raises doubts regarding al-Mawla’s reported connections to the Camp Bucca network and to al-Baghdadi himself at that time. There is no certainty on this point, as there are several alternative explanations for this discrepancy in the timeline.

One is that, assuming the dates of detention for both al-Baghdadi and al-Mawla are accurate and that al-Mawla’s 2008 capture was his first time being detained, these two individuals never actually crossed paths in Camp Bucca.m Of course, it is not implausible that al-Mawla had been previously detained prior to his capture in 2008. It is not inconceivable that he was captured and placed into Camp Bucca during 2004 and met al-Baghdadi during this time. Under this scenario, al-Mawla would have to have been released at some point in time and then recaptured in 2008. However, nothing in these TIRs, either in al-Mawla’s statements or in the administrative data, indicates a prior detention.n

Another possibility is that al-Baghdadi’s detention timeline is incorrect, too. Under this scenario, al-Baghdadi and al-Mawla could have met in prison, but not during al-Baghdadi’s only confirmed stint in prison, which began in February 2004.o Although there has been some debate regarding when al-Baghdadi’s time at Camp Bucca ended,p in 2019, the Pentagon confirmed to a journalist that he had been released after 10 months in custody, with no indications that he was captured again.17 In sum, although it is difficult to come to any definitive conclusion, these TIRs cast doubt on the notion of an al-Baghdadi/al-Mawla relationship as a result of being jointly detained in Camp Bucca in 2004 or 2008.

Beyond details regarding the circumstances of al-Mawla’s capture, the real substance of the TIRs comes from two general types of conversation conveyed in the documents. One type is information about al-Mawla’s background and personal involvement with the insurgency. It is this category of information that can provide the details that are currently lacking regarding the Islamic State leader’s personal characteristics and biography. The other type focused on what al-Mawla knew about ISI, both on the organizational and individual level. The interrogators’ goal of pursuing this type of information would likely have been to invite al-Mawla to reveal what he knew about how ISI ran its operations and about the key individuals and personalities that made up the organization. Such information could then have been utilized to enable further military efforts against those individuals. The remainder of this article explores these two types of information.

Al-Mawla’s Background

As noted above, very little is known about al-Mawla’s early life and introduction into ISI. Although the brief discussions contained in the TIRs do not completely fill in all the gaps, they do provide some insight into at least two distinct parts of al-Mawla’s background: pre- and post-recruitment into ISI.

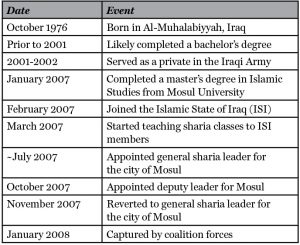

When it comes to the pre-ISI stage of his life, the TIRs shed light on the location and date of his birth. It has long been suggested that al-Mawla was born in Tal Afar. However, because Tal Afar refers to both a specific city as well as a larger region, there has always been some ambiguity regarding his birthplace. In these TIRs, al-Mawla states that he was born in Al-Muhalabiyyah, Iraq, in October 1976, which would have made him 31 years old when U.S. military forces arrested him and 43 years old today (September 2020). Al-Muhalabiyyah is a small town of 14,000 residents (in 2011), located in the Tal Afar district but approximately 20 miles from the actual city of Tal Afar.18 The Tal Afar region is home to an ethnically diverse population of Arabs and Turkmen, with some estimates placing the proportions in the early 2000s at 10 and 90 percent, respectively.19 Although the specific ethnic breakdown of Al-Muhalabiyyah is not known with certainty, it is generally accepted to be predominantly Turkmen.20

The birth of al-Mawla in Al-Muhalabiyyah raises an important issue regarding his ethnicity. Indeed, whether al-Mawla is Turkmen or Arab has been a critical point of discussion in public discourse. A few sources have suggested that if al-Mawla is a Turkmen, this could pose legitimacy problems for him because the Islamic State mostly has Arabs in its senior leadership echelons.21 One caveat is that at least two other senior members of the group—Abu Muslim al-Turkmani, allegedly the second-in-command of the group before his death in 2015, and Abdul Rahman Mustafa al-Qaduli, a senior official in the group’s “cabinet”—were both reported to have been Turkmen as well.22

Beyond this claim, however, potentially lies a more challenging one. Several sources, including a U.N. report to the Security Council made public in January 2020 and based on the observations of several member states, suggested that his Turkmen lineage would indicate that he could not be from the Qurayshi tribe, a prerequisite to being the caliph.23 If accurate, this claim would be incredibly damaging to al-Mawla’s legitimacy, because it would suggest al-Mawla cannot fulfill the requirements to serve as the caliph. The implication being made is that al-Mawla’s tribal lineage is exclusively Turkmen, not Arab. However, other analysts have pointed out that this is not necessarily the case and that the larger al-Mawla and constituent al-Salbi tribes may have distant connections to the Qurayshi tribe.24 These competing perspectives, while holding important consequences for the legitimacy of the Islamic State leader, are difficult to resolve and it is not clear which ought to hold sway.

Aside from the birth location of al-Mawla in an area that is majority Turkmen, however, there is little in the TIRs to substantiate the claim that he is of Turkmen origin.q Moreover, the only piece of tangible evidence in the TIRs contradicts this theory. In the biographical details printed at the top portion of each TIR, al-Mawla’s ethnicity is indicated as Arab.25 If accurate, this would represent an interesting deviation from the current understanding of al-Mawla. Of course, this may have been an intentional deception on al-Mawla’s part, something that he truly believed, or simply an error by the transcriber of the TIRs in entering al-Mawla’s biographical information, but none of these outcomes can be verified relying only on the TIR. Recent efforts to uncover more information about this point, however, strengthens the conclusion that al-Mawla is an Arab.26

The Tal Afar region experienced significant security challenges following the 2003 invasion of U.S. and coalition forces, although there are also indications that radical groups and individuals had a presence and stoked sectarian tension there long before this point.27 Unfortunately, the TIRs do not paint a clear enough timeline to know whether al-Mawla stayed in his hometown for long, moved on, or whether these years formed an important part of his evolution into a jihadi. The next date that appears in the TIRs is his time in service in the Iraq military, which occurred for approximately a year and a half from 2001-2002, when he would have been about 25 years old. Although the specific actions of al-Mawla during his military years are unknown, the TIRs note that he held the rank of private in the infantry and worked in some sort of administrative position.28 r

That said, there is nothing remarkable or that can be easily interpreted about al-Mawla from the mere fact that he served in the Iraqi Army, as at the time, service in the Iraq military was compulsory. However, it is hard to believe that the overall condition of the Iraqi Army would not have had an impact on al-Mawla when it came to his perspective regarding the Iraqi government and the value of organizational skill and the challenges of dealing with low morale. The Iraqi Army immediately prior to this point in time was a struggling entity, with one report referring to Western intelligence estimates of a desertion rate of 20-30 percent.29

The fact that al-Mawla served 18 months in the military, as opposed to a longer duration, is interesting. As already noted, military service in Iraq was compulsory for all males during the time, but the length of service required was contingent on factors such as education.30 With conscription in Iraq at this time, those who did not complete high school had to serve three years in the military, those who completed high school served two years, and those who finished a college degree served 18 months.s Thus, the fact that al-Mawla was in the Iraq Army for 18 months suggests that he had most likely graduated with a bachelor’s degree prior to joining the army, although it is not referenced anywhere in the three TIRs. It is interesting to note, however, that those who elected to pursue graduate studies and successfully completed a graduate degree could do so and would only have to serve in the military for four months upon completion of their degree. The fact that al-Mawla did not appear to pursue religious graduate studies at this point in his life (which, by his own account, he eventually did later on) might suggest that it was not necessarily a desire at this time. Of course, this conclusion is merely speculative given the lack of detail presented in the TIRs about al-Mawla’s pre-Army activities.

Following his time in the military, the next significant date highlighted in al-Mawla’s resume is his completion of a master’s degree in Islamic Studies from the University of Mosul in January 2007. Religious knowledge is seen as essential for a caliph, as it provides him with the theological repertoire to eventually lead.31 Al-Baghdadi, al-Mawla’s predecessor, was said to have a doctorate in Islamic jurisprudence.32 Although having a degree in religious studies is not necessarily the only way to meet the knowledge requirement, the fact that al-Mawla did have such a degree is important. Indeed, al-Mawla’s religious expertise was specifically noted by at least one other senior Islamic State figure when speculating on the next leader following al-Baghdadi’s death.33

Beyond equipping him with religious credentials, al-Mawla’s religious expertise also appears to have been his gateway into the group.t After his graduation in January 2007, he claims that he was approached by someone named Falah to participate in ISI’s religious education efforts. For his part, al-Mawla said that he decided to join the organization in February 2007. This part of al-Mawla’s timeline is intriguing. By early 2007, the Iraqi insurgency was raging, with violence increasing since the bombing of the al-Askari mosque in February 2006 and with the first U.S. troops being deployed as part of the “surge” strategy.34 From ISI’s perspective, this period was marked with increasing challenges due to internal strife and counterterrorism pressure from both state and non-state actors.35

The fact that, from his own recollection conveyed nearly two-and-a-half weeks into his detention, al-Mawla seems to have only joined after being approached by Falah suggests either a lack of vision regarding what the struggle was to become or an indifference to all that had been occurring in the several years prior to his recruitment.u Indeed, the individual who preceded al-Mawla as leader of the Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, founded his own militant group immediately following the U.S. invasion in 2003, was imprisoned in 2004, and joined the emergent Mujahideen Shura Council when it was formed in January 2006.36 Al-Mawla appears, in contrast, to have somehow avoided participation in any of these events despite being just five years younger than al-Baghdadi. The fact that he started and completed graduate studies during this time suggests his focus was not on the battlefield and that he may not have shared the same early commitment to the jihadi cause as many others during this time, including al-Baghdadi, his eventual predecessor as head of the Islamic State.

Of course, alternative interpretations might explain why al-Mawla downplays his recruitment narrative. It could be that he was trying to minimize his level of commitment to the group. Under this scenario, al-Mawla, would have been an active participant in the early insurgency in Iraq, but either deliberately hid such details during his interrogations or was not questioned in detail about his own history in the insurgency.v However, if this were true, it would also require an explanation why al-Mawla, having confessed to being the current leader responsible for ISI’s interpretation of Islamic law in Mosul and a past second-in-command for the group in the city, would still feel a need to minimize his origin story. Thus, the TIRs raise the possibility of al-Mawla as being aloof from the insurgency during its early phase, but also do not provide sufficient detail to exclude the possibility of his being deceptive on this point.

Moreover, al-Mawla’s motives for joining ISI are not entirely clear in these documents either. In one of his early TIRs, which took place two days after his capture, al-Mawla makes the dubious claim that he “joined ISI in order to stop fighters attacking innocent people and was not in ISI for the money.”37 This same theme is not repeated (or at least was not included) in al-Mawla’s narrative in a session a couple of weeks later about joining the organization, in which it seems that his initial attraction to the group stemmed from a request to teach classes to ISI members, and less from his own convictions.38 This inroad due to religious classes opens the possibility that al-Mawla’s attraction may have been due to the religious justification upon which the group tried to stake its claims to become a “state.” This was an issue the group was discussing quite publicly in late 2006 and early 2007, at the time al-Mawla claimed to have recently received his graduate degree in Islamic studies.39 These potential observations aside, it seems likely that more details about his recruitment might be present in TIRs that have not yet been made public.w

One point regarding al-Mawla’s early claims of his recruitment is worth discussing because it seems to be so out of place. In the earliest of the three TIRs, al-Mawla claims to have avoided pledging allegiance to ISI because he was a Sufi.40 The claim that he did not pledge allegiance seems unlikely, given both his quick rise in the group and the fact that his later statements do not reference this point at all.41 Al-Mawla’s claim about being a Sufi also seems absurd, as the Islamic State and its predecessor organizations branded Sufis as heretics and carried out acts of heinous violence against Sufis.42 However, despite its seeming falsity, even this statement made by al-Mawla in the TIR has found corroborating evidence in recent reporting.43 If true, it would not only suggest that al-Mawla was uninvolved early on in ISI, but that he may have come from a background antithetical to the group’s beliefs. In this case, al-Mawla either would have had to conceal this from ISI or renounce these beliefs before joining. However, these claims, both about being a Sufi and about not pledging allegiance, should be viewed cautiously, as al-Mawla does not repeat this claim in the later TIRs, even when revisiting the topic of joining the organization. The latter claim about not pledging allegiance seems particularly nonsensical given the eventual positions al-Mawla claims to have occupied in the group.

After joining the group, al-Mawla seems, according to what can be deduced from his own account, to have taught religious classes for only a few months before being appointed the leader of ‘Islamic’ law (sharia) for ISI for the city of Mosul.44 This position would have put al-Mawla at the center of several activities that extend well-beyond preaching and teaching classes, as the ‘correct’ interpretation of Islamic law plays a critical role in military, media, and personnel matters within the group. This begs the question: could al-Mawla, merely months into his membership in the group, really have risen so quickly up the ranks?

It is possible that he is lying about his progression in the group. Because he claimed to have been a Sufi, and given what seems to be a recruitment narrative that is more accidental than passionate, it strains credulity to think that he rapidly climbed the ranks of ISI. However, because it seems likely that he did actually end up in the ISI positions he claims to have held, this suggests the misrepresentation might be in relation to his timeline for joining. Indeed, he may have joined many months (or even years) before he claims to have done so. In this scenario, al-Mawla’s story becomes much more clouded, as any timeline which suggests his interfacing with ISI prior to January 2007 would greatly undermine the rest of the narrative he posed in these TIRs. Other than the fact that the timeline seems implausible, no direct information could be identified in these TIRs to support this conclusion. And, to the contrary, recent reporting has suggested that al-Mawla may have remained a Sufi through 2007.45 If this is true, earlier recruitment by ISI would seem unlikely.

Of course, there are possible reasons which explain how al-Mawla could have advanced so quickly. His religious training provides one explanation, as it was something in high demand in the group. Another possibility is that he had personal relationships with the right figures, perhaps aided by the fact that he operated in Mosul, which was a critical node in the group’s organization. In addition, the pressure from the Awakening councils and counterterrorism operations by the U.S. military during the mid-2000s occurred against large numbers of targets at a very high pace. For example, in August 2004, U.S. Special Operations forces conducted 18 raids against counterterrorism targets in Iraq. That number had increased to 300 a month by August 2006.46 It was still at the rate of about 10 to 20 captures a night in mid-2008 across Iraq.47 The fight in Mosul was particularly intense, with one report noting that during May and June 2007, “13 AQI leaders were captured or killed in Mosul.”48 Perhaps the confluence of factors, al-Mawla’s religious training and high personnel turnover within ISI because of counterterrorism actions, created a path for quick ascendency. There is some indication of quick turnover among leadership figures in the TIRs due to captures and battle deaths, but such evidence is circumstantial and does not provide conclusive answers.x

Regardless of whether al-Mawla’s timeline for rising in the group is accurate, it seems clear that he ultimately participated in a wide range of the group’s functions. Such activities are discussed by al-Mawla in some detail, including the mediation of disputes with other militant groups, nomination of judges, oversight of ISI media fliers, and issuance of binding legal rulings regarding ‘Islamic’ law in a number of cases.49

The latter category, legal cases in which al-Mawla was involved, are highlighted in some detail in one of his TIRs in which he appears to offer case summaries for judicial decisions that he made.50 Although highlighting each of these cases in detail here is beyond the scope of this article, a few examples show how al-Mawla’s decisions were sometimes seemingly ineffective, but also how his rulings led to real consequences for the parties involved. In one of the cases he oversaw—which involved the death of three individuals at the hands of Ansar al-Sunna, an Iraqi militant group—al-Mawla’s verdict regarding Ansar al-Sunna’s culpability for those deaths apparently did not sit well with the implicated group, leading to what seems to be no resolution. In two of the cases, one for an unknown individual and the other allegedly for a fellow ISI member, he orders whippings for swearing.

Several of his cases involve rulings on the amount of ransoms required to be paid in order to release individuals kidnapped by ISI. Each of these kidnapping cases seems to have a positive outcome in which the hostage returns home, and the authors of this article are left to wonder if al-Mawla is telling the truth regarding his rulings or whether he is minimizing the negative consequences of his rulings.51 This is hard to tell. In the case of Western hostages, previous research has shown ISI kidnappings quite frequently end in the hostage’s murder.52 In the case of locals, mixed incentives seem to result at times in death and at times in release for ransom.53 Among the cases al-Mawla mentioned he was involved in, both outcomes are represented. In one, the sole case resulting in the death of the hostage, the victim was identified by al-Mawla as a member of the Iraqi Army.54 Here, however, al-Mawla seems to distance himself from the implementation of execution as a punishment, although he seems to have been aware of the decision at the very least. In another, al-Mawla judged that a ransom payment was needed to return the individuals to their families.55

Because of numerous personnel changes within the group (for reasons that are not always explained), al-Mawla also says he served for a time as the deputy leader for the city of Mosul. In this role, he claims that he was “second in command” in the city and says that he was aware of various ISI activities such as kidnapping, executions, assassinations, and ransoms. His discussion of his knowledge of, but never his participation in, these activities may be an attempt to downplay his involvement in any decision-making processes. While understandable for someone who is being interrogated by an adversary, al-Mawla’s discussion of his activities suggests he was operationally involved to a significant level prior to his capture. Regardless of his actual level of involvement, al-Mawla clearly occupied a leadership role within an organization that carried out a large number of operations in Mosul, many of which likely harmed the very people he claimed in an earlier session he had joined the group to protect.56 y

In sum, al-Mawla’s timeline (seen in Table 1) prior to his capture in January 2008, as depicted by his own statements and conveyed through these TIRs, is interesting for many reasons. First, it gives more insight into the history of an individual who is allegedly at the head of the Islamic State. Of course, while this information is essential, there are still significant gaps in his biography. If more information, details, and documents were available, it would significantly enhance the counterterrorism community’s understanding of al-Mawla’s individual path into jihad and potentially his leadership style.

Second, his self-described timeline paints a picture of him as a relative late-comer to AQI (al-Qa`ida in Iraq)/ISI specifically, but also potentially to the Iraqi insurgency more broadly. Though certainly not conclusive of his own beliefs about the insurgency, it is hard to imagine an individual who early on felt passionately about the cause staying on the sidelines for so long. Third, this personal timeline provides a glimpse of an individual who has a significant amount of leadership experience. Assuming that his timeline for joining is correct, and there are certainly valid reasons to be skeptical of it, al-Mawla played several relatively notable and involved roles in a very short period. Although such experience would undoubtedly have offered him a crash course in being a militant leader, the value of which should not be understated, it also would have made him a potential liability if he were captured. In this next section, the authors examine in more detail how al-Mawla’s knowledge of the inner workings and people of the organization was discussed in some level of detail during his interrogations and may have been connected to military operations carried out against at least one prominent ISI figure.

Al-Mawla’s Colleagues

One of the more intriguing facets of al-Mawla’s interrogation sessions is how much information he yields regarding the individuals that may have worked in various positions within ISI. At least in part, his knowledge of so many different players speaks to his ability to cultivate support from others within the movement, but what he told the interrogators provides a window into his strategic calculations regarding his concern with his future as opposed to the future of those about whom he spoke. The matter of revealing information while in custody is not new. One of the best-known examples is that of Ayman al-Zawahiri, who, while under torture, allegedly gave up the hiding place of one of his confederates who was apprehended and executed by the Egyptian security services.57 Later, in writing a rebuttal to a critique of him and the organization to which he belonged, al-Qa`ida, al-Zawahiri made several references to the lack of culpability those who are in prison should face for statements they make.58

Setting aside the issue of guilt or condemnation, the authors believe that al-Mawla’s conversations about his fellow fighters are worth exploring and considering because they offer researchers a window into who al-Mawla was and how he performed in his trusted role. However, the matter of categorizing this information as contained in the TIRs is far from straightforward. The declassified TIRs themselves include no unique identifiers to cross-reference individuals from one session to the next. Moreover, most of the names offered are aliases, making identifying duplicate entries difficult without further details. Unfortunately, some of the names and descriptions are less robust than others, making the issue of counting how many individuals he named challenging at best.

Despite these challenges, the authors attempted to create a list of the total number of names al-Mawla gave during these three sessions. Wherever possible, the effort sought to identify common names across all three sessions, in effect reducing the amount of possible double-counting in the authors’ tally. Even with these efforts, there is some amount of uncertainty regarding the specific number of unique names al-Mawla discussed. With those caveats, it appears that al-Mawla described or named approximately 88 individuals over the course of these three sessions. Not all of these descriptions are equal, however, as some simply refer to what he heard someone else call an individual at a meeting (“Doctor” in one case), whereas others are robust descriptions of what the individual looked like, what function they performed within ISI, and the frequency with which al-Mawla engaged with some of these individuals. For example, in 64 of the 88 cases, al-Mawla provided at least a basic description of the organizational department in which the named individual worked in ISI, including the ‘Islamic’ legal, military, security, media, and administrative branches.

Al-Mawla’s willingness to provide detailed information on individuals is especially prevalent in one of the TIRs.59 In it, al-Mawla appears to be giving an affidavit of some sort against several individuals, identifying them specifically as members of ISI and noting their illegal activities such as kidnapping, assassination, and attacks on coalition forces.60 Specifically in this session alone, he testifies against no fewer than 20 individuals in front of what appears to be some sort of legal official (referred to as a “prosecutor” in the TIR).z Because the authors must rely on the TIRs alone, it is difficult to speak definitively about al-Mawla’s rationale for identifying these individuals. However, the end of the TIR contains a note which says, “I wrote his statement with my hand and of my own free will without pressure or coercion.” It is likely that the “his” in this statement is a transcription typo and that it should have been “this,” reflecting that al-Mawla was writing these actual words. If true, that suggests a certain level of agency on al-Mawla’s part regarding how much information he provided. The fact that he detailed activities and gave testimony against them suggests a willingness to offer up fellow members of the group to suit his own ends. Indeed, almost every statement from al-Mawla toward the 20 individuals carries with it the almost formulaic pronouncement “(blank) is a member of ISI.”

Beyond his recollection of individual roles and names, al-Mawla also conveys the organizational structure of ISI in Mosul in some detail, going so far as to help complete a line-and-block chart that shows the names and positions of approximately 40 individuals functioning in various roles. Although all the names he provided were aliases, which may or may not ultimately have been helpful in identifying who these specific individuals were, it seems clear that such information could be used to narrow down the pool of individuals serving in certain roles and provide at least some level of corroboration if these individuals ever were captured and prosecuted. Beyond naming these individuals, however, his organizational descriptions in the form of line-and-block charts do not appear to convey much substantive information about how these respective departments functioned. Such information is gleaned more from his own descriptions of his activities and interactions than from the charts.

What does this tell us about al-Mawla? On the practical level, the amount of detail and seeming willingness to share information about fellow organization members suggests either a degree of nonchalance, strategic calculation, or resignation on the part of al-Mawla regarding operational security. His comments regarding the few individuals already deceased (al-Mawla identified eight of the 88 as already deceased when he was captured) presumably had little consequence for his group. However, for the individuals already in U.S. military custody (al-Mawla seemed to believe that at least 14 of the individuals discussed had already been captured by coalition or security forces) or still operating in Iraq at the time of his interrogation, al-Mawla’s descriptions of their roles likely had repercussions for at least some of those individuals.aa

Previous research by the CTC has relied on personnel records in the form of spreadsheets created by the Islamic State to document payments to personnel during the 2016-2017 timeframe.61 Using the full names listed at the end of one of the al-Mawla TIRs, the authors searched other CTC documents to see if these individuals appeared.ab Through this process, eight individuals whose full names were identified appear to be listed both in the TIRs and also in the spreadsheet.ac Seven of these individuals, based on dates of birth contained in the payment spreadsheet, would have been between the ages of 23 and 49 in 2008.ad The authors must stress the fact that even though the same full names were listed in both documents, there is no way of verifying that they are the same individuals.

What is particularly interesting is that of these eight individuals, six are listed in the financial spreadsheet from 2016/2017 as being prisoners or detainees in 2016/2017. This spreadsheet represented a period of about eight to nine years after the al-Mawla TIRs. Additionally intriguing is that fact that of those six individuals identified as being detained in 2016/2017, four were identified by al-Mawla in his TIRs as having been detained during the same time in which he was back in 2008, while the status of the other two is unclear based on al-Mawla’s TIRs.

Is it possible that four of the individuals against whom al-Mawla gave statements in 2008 were still in Iraqi custody in 2016, having never been released? Several rounds of prisoner releases or amnesty took place before and after 2008 as the United States sought to figure out how to handle thousands of detainees and transferred custody of thousands to the Iraqi government. It is certainly possible that, even if these are the same individuals, they were released and recaptured at a later point. However, it is critical to note that these prisoner releases typically excluded individuals convicted of terrorism charges, assuming there was evidence of such.62 This raises the possibility that, perhaps in part due to al-Mawla’s direct testimony against them, some ISI members may remain in prison to this day.ae

In addition to the individuals discovered in the payment spreadsheet, other declassified information offers potential insight into the impact of al-Mawla’s testimony. For example, a document used in a RAND study referred to a raid carried out in early 2008 by U.S. military forces against an ISI media operative named Khalid.63 According to the RAND study, when Khalid was captured, he was in possession of personnel documents that named “Abu Hareth” as the ISI administrative emir during the late 2007 to early 2008 timeframe.64 Al-Mawla named an ISI member known as Abu Harith in all three of his TIRs as occupying the same position.af It is, of course, impossible to say where the information that guided U.S. military forces to Khalid came from or to attribute it to al-Mawla, but an ISI operative called Khalid is mentioned in two of al-Mawla’s three TIRs as still functioning in his media role when al-Mawla was captured.65 In one of the TIRs, a redacted reference states that al-Mawla provided a physical description of an individual he named as Khalid.66 In another, al-Mawla claims to have carried out several meetings in this Khalid’s office, suggesting he would have known this Khalid and his place of work with some familiarity.67 This raises, but does not conclusively confirm, the possibility that the raid that led to the capture of Khalid was influenced by al-Mawla’s interrogation.ag

In addition to Khalid, there is another interesting connection between al-Mawla and later military action against ISI. In October 2008, a raid by U.S. military forces killed Mohamed Moumou, also known as Abu Qaswara al-Maghribi, who some reports suggested was in top tier leadership of ISI at the time and overall leader of ISI’s efforts in northern Iraq, including Mosul.ah Other reporting at the time suggested that Abu Qaswara, also known as Abu Sara, also had some responsibility for foreign fighters coming in and out of Iraq and was a Swedish citizen.68 For such a high-ranking individual, intelligence likely came from a variety of sources and methods. However, these TIRs also suggest that al-Mawla may have contributed in some measure to his elimination, as Abu Qaswara is one of the 20 individuals against whom al-Mawla testified.69

In his testimony, al-Mawla notes the importance Abu Qaswara plays in the organization, the fact that his accent shows that he is not from Iraq, the important role he played in ISI administration in the region, and his role in helping individuals get medical treatment outside of Iraq, all of which are facts that have since been verified in reporting about Abu Qaswara. Perhaps most importantly, al-Mawla notes that he met Abu Qaswara on two occasions. Since the authors are working with a limited set of data, they ultimately cannot say what role this information may or may not have played in guiding the U.S. military to Abu Qaswara.ai It does raise the possibility, at the very least, however, that al-Mawla did provide information that may have helped focus attention on, and ultimately lead to the death of, ISI’s then second- or third-in-command, an individual lauded by the then-leader of ISI as “one of the great figures of the State.”70

Beyond whatever the discovery of these names in other files held by the Islamic State might suggest, the fact that these names appear in other documents indicates that al-Mawla was speaking, at least in part, about genuine colleagues in ISI. As an additional data point, the authors were able to locate a partial list of names of individuals transferred from the U.S. military to the Iraqi government. The list was posted by an Iraqi human rights organization online in 2012.71 At least two of the 20 individuals against whom al-Mawla provided testimony in front of some sort of legal official appear in this list. In other words, taking into account what appear to be matching names in Islamic State spreadsheets (eight individuals), on the roster of the human rights organization (two individuals), and found in other open-source reporting (one individual—Abu Qaswara), there is evidence to suggest that at least half of these individuals named in detail by al-Mawla appear to be authentic.

This section has considered what the TIRs reveal about al-Mawla’s discussions of the other individuals inside ISI. Although there are clearly some gaps and it is difficult to corroborate any of the information provided, a few pieces of information suggest that the individuals al-Mawla discussed were real. The TIRs, however, do not reveal any of al-Mawla’s motivations for discussing these specific individuals, although from the line-and-block charts he outlined of ISI’s structure in Mosul, he does not appear to have been sharing information only about a certain subset of individuals. Rather, he appears to have named individuals in some capacity across all levels of the organization, while describing some individuals in some detail.

Conclusion

This article has provided a brief first look at a unique set of information in an effort to help fill in some of the biographical and behavioral details regarding the individual alleged to be the head of the Islamic State: Amir Muhammad Sa’id ‘Abd-al-Rahman al-Mawla. Since his appointment, several questions have been raised regarding al-Mawla and his background, yet the availability of sources has limited the ability to find answers. The information presented in this article is certainly far from perfect and not without its own challenges, but the authors believe that it can help provide partial clarity to a topic that has been shrouded in much uncertainty.

For instance, this article has suggested that key assumptions about al-Mawla, notably his Turkmen ethnicity and early involvement in the insurgency in Iraq, may not be accurate. Moreover, statements made by al-Mawla, while doubtless trying to minimize his own commitment to ISI, suggest that his commitment may have been borne less of zeal than of serendipity. If true, this would suggest that something certainly changed in al-Mawla, as his later reputation suggests someone who ruthlessly pursued his ideology, even to carrying out genocide against its enemies.aj The TIRs also show that al-Mawla, who, according to the timeline that he himself provided, appears to have quickly risen in the organization’s ranks in part because of his religious training, knew much about ISI and was willing to divulge many of these details during his interrogation, potentially implicating and resulting in the death of at least one high-ranking ISI figure. This information, however, should not necessarily be taken at face value. The claims made by al-Mawla while in custody are very difficult to verify, adding a critical note of caution to the findings discussed in this article.

Of course, one source that has yet to offer many details is the group itself. To date, no sort of biography has emerged from the Islamic State to fill in the blanks regarding the questions of al-Mawla’s lineage, early life, or actions before and after his capture by U.S. military forces. More fundamentally, the group itself has not even acknowledged that their leader is named al-Mawla. This may be an intentional omission due to security reasons, because the group looks forward to contradicting the guesses and assumptions of others, or because on the critical issue of internal group cohesion, it sees no benefit to be gained from doing so. Of course, not showing himself may have negative tradeoffs, such as potentially limiting the appeal of the Islamic State around the world.72 Regardless of the ultimate reason, it is unlikely that this article will be the final word. Moreover, as more information about al-Mawla becomes available, some details, especially regarding his early life and his time spent in ISI, may need to be revised accordingly.

The 2008 Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) between Iraq and the United States required that the United States provide information to Iraq on all detainees being held at that time, and that Iraq would either pursue legal avenues against them or the United States would then release them.ak Under the terms of this agreement, the United States transferred custody of al-Mawla to the Iraqi government.73 One question that is beyond the scope of this article, yet looms in the background, is why was al-Mawla, given the level of leadership and involvement in the insurgency to which he appears to have admitted in the three TIRs, ultimately released? The data here does not allow the authors to answer that question, although it is important to note that tens of thousands of individuals were in U.S. military custody from 2003-2011.al Al-Mawla is not the first future Islamic State leader to have been released from custody in Iraq. His predecessor, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was detained and released by U.S. forces in 2004.74 Despite some excellent work in this area, there is a need for more research and analysis, both inside and outside government, on the subject of detention policies and the identification of future threats.75

In the end, there is clearly more to be learned about al-Mawla, his early history, and the role that he played in ISI, but also about the path he took when released from custody by the Iraqi government. Subsequent reporting refers to him as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s deputy in the period before he succeeded him as leader and, as noted above, connects him to the genocide of Yazidis in Iraq in 2014.76 Making a more complete set of al-Mawla’s TIRs available, as well as those of other figures in the militant movement, such as occurred in the case of Shi`a Iraqi militant Qayis al-Khazali, would allow for a more conclusive and comprehensive analysis both of these organizations and the individuals who play prominent roles within them.am The authors’ hope is that more information will come to light to help answer these questions and enhance our understanding of terrorist groups and the individuals that lead them. CTC

Daniel Milton, Ph.D., is Director of Research at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. His research focuses on the Islamic State, propaganda, foreign fighters, security policy, and primary source data produced by terrorist organizations. Follow @Dr_DMilton

Muhammad al-`Ubaydi is a research associate at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

The authors thank Audrey Alexander, Meghan Cumpston, Paul Cruickshank, Brian Dodwell, Kristina Hummel, Damon Mehl, Don Rassler, and a group of anonymous others for their help in bringing this article to fruition.

© 2020 Daniel Milton and Muhammad al-`Ubaydi

The three Tactical Interrogation Reports described in this article are accessible on the Harmony Program’s page here.

Click below to access the three Tactical Interrogation Reports directly. The documents are available in original language (English) and in Arabic translation.

Substantive Notes

[a] Indeed, the release of a biography of al-Mawla’s predecessor, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, more than a year before he claimed the mantle of the caliph, sought to outline al-Baghdadi’s credentials in a way to strengthen his hold on the movement. Haroro J. Ingram, Craig Whiteside, and Charlie Winter, The ISIS Reader: Milestone Texts of the Islamic State Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020): p. 173.

[b] In a report made public in January 2020, the United Nations did offer that several states believed that al-Mawla was the likely successor, although they cautioned that the information had not yet been confirmed. “Twenty-fifth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” United Nations, December 27, 2019; Paul Cruickshank, “UN report warns ISIS is reasserting under new leader believed to be behind Yazidi genocide,” CNN, January 29, 2020.

[c] This article relies on al-Mawla full name as stated in both the U.S. designation announcement and the relevant field from the TIRs. However, it is important to note that in TIR B, the name of his tribe is listed as al-Slibi, not al-Mawla. This is discussed later in the article. Additionally, when describing his own picture in TIR B (Photo #1), he appears to omit the name “Amir.” Because these are typed summaries of the session, it is hard to say whether this was a deliberate or accidental omission on his part, or whether the transcriber of the session made a mistake. In TIR C, which appears to be a more carefully transcribed confession of sorts, he does use the name “Amir.” “Terrorist Designation of ISIS Leader Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Mawla,” U.S. Department of State Office of the Spokesperson, March 17, 2020.

[d] The U.S. government has publicly stated that al-Mawla “was a religious scholar in ISIS’s predecessor organization.” “Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Mawla: Up to $5 Million Reward,” Rewards for Justice, August 21, 2019.

[e] Upon capture, detainees were generally held in local, smaller detention facilities (referred to as Temporary Holding Facilities or THF) until they could be transferred to larger facilities where most of the detainees were held (Theater Internment Facilities or TIF). In some cases, detainees might be interrogated for as long as 14 days before they had to be transferred to a TIF. After their initial screening at the TIF to determine their potential intelligence value, detainees determined to have potentially useful information would be taken into interrogation rooms by personnel from the Joint Intelligence and Debriefing Center (JIDC) and questioned regarding their own background, as well as their knowledge of militant activities and organizations. Robert M. Chesney, “Iraq and the Military Detention Debate: Firsthand Perspectives from the Other War, 2003-2010,” Virginia Journal of International Law 51:3 (2011): pp. 549-636. The THF sometimes consisted of multiple different facilities, known as brigade internment facilities (BIF) and division internment facilities (DIF). W. James Annexstad, “The Detention and Prosecution of Insurgents and Other Non-Traditional Combatants: A Look at the Task Force 134 Process and the Future of Detainee Prosecutions,” Army Lawyer 72 (2007): pp. 72-81; Brian J. Bill, “Detention Operations in Iraq: A View from the Ground,” International Law Studies 86 (2010): pp. 411-455.

[f] Whether these sessions took place at a THF or TIF, interrogators would typically speak through an interpreter, who would relay questions and then convey the detainee’s answers to the interrogator. After a session was complete, a paraphrased summary of the interrogation was written up into a document known as a TIR. Although the format of TIRs may differ slightly from one detainee to the next or from one time period to the next, they each tend to contain the same types of demographic and contextual information: the detainee’s name, when the interrogation session took place, basic information regarding when the detainee was captured, the detainee’s family status, work experience, and basic biographical information. Chesney; Bill.

[g] The authors have been informed that the remaining TIRs are under review to see if their release would have negative impacts on current operations. Author correspondence with U.S. State Department officials.

[h] A couple of points need to be made about the date and time. First, it reflects the time at which the interrogation session was conducted. Second, the use of the letter ‘c’ after the time indicates the “Charlie” time zone, of which Iraq is a part. Thus, 0137C is 1:37am local time in Iraq.

[i] Generally speaking, detainees could be held and questioned in the THF for up to 14 days, at which point the had to be transferred to a TIF. Thus, although it is not clear from the TIRs when al-Mawla was transferred, it is possible that TIR A occurred at the THF near his point of capture and TIRs B and C took place at the TIF. Chesney, p. 569.

[j] The fact that TIRs B and C both have the same time stamp suggests that multiple sessions may have been carried out at that time or that, due to the nature of the content discussed in the session, it may have been broken out into two reports. It may also simply be a clerical error.

[k] It would be disingenuous to suggest that no problems existed after this point at Camp Bucca. Indeed, several military personnel were accused of abuse in Camp Bucca in August 2008. “U.S. Navy: 6 sailors accused of abused detainees in Iraq,” USA Today, August 14, 2008. Other studies found that significant changes were slow in coming and that gradual improvement eventually occurred. Jeffrey Azarva, “Is U.S. Detention Policy in Iraq Working?” Middle East Quarterly 19:1 (2009): pp. 5-14.

[l] Night raids by U.S. forces were relatively common in Iraq as a method of using the element of surprise to detain suspected militants. For one example, see Michael R. Gordon, “Night Raid in Iraq: Seeking Militants, but Also Learning the Lay of the Land,” New York Times, August 4, 2007.

[m] Aside from one account of open-source reporting, the authors are not aware of any evidence of al-Mawla being detained prior to 2008. Martin Chulov and Mohammed Rasool, “Isis founding member confirmed by spies as group’s new leader,” Guardian, January 20, 2020.

[n] Perhaps this was a strategic choice on his part to prevent knowledge of his prior encounter with authorities, whether coalition forces or local security services. Al-Mawla certainly would have had incentive to hide such information.

[o] This capture date comes from U.S. Army detention records about al-Baghdadi that are available at the Army’s Freedom of Information Act reading room. Al-Baghdadi was listed as detainee “US9IZ-157911CI.”

[p] The issue of al-Baghdadi’s time in prison has received a fair amount of press attention. Terrence McCoy, “How ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi became the world’s most powerful jihadist leader,” Washington Post, June 11, 2014; Colin Freeman, “Iraq crisis: the jihadist behind the takeover of Mosul – and how America let him go,” Telegraph, June 13, 2014; Aaron Y. Zelin, “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: Islamic State’s driving force,” BBC, July 31, 2014; Joshua Eaton, “U.S. Military Now Says ISIS Leader Was Held In Notorious Abu Ghraib Prison,” Intercept, August 25, 2016. Some of the debate centers around statements made by a former U.S. military officer at Camp Bucca who claims to have seen al-Baghdadi in 2009. In 2014, these claims led U.S. officials to tell ABC News that al-Baghdadi was back on the battlefield by 2006. James Gordon Meek and Lee Ferran, “ISIS Leader’s Ominous New York Message in Doubt, But US Still on Edge,” ABC News, June 16, 2014.

[q] There is substantial discussion in the open source regarding potential evidence of al-Mawla’s Turkmen ethnicity. Some have pointed out that an individual that is allegedly al-Mawla’s brother, Adel Salbi, was at some point a member of the Iraqi Turkmen Front, a political party. Chulov and Rasool; Mina al-Lami, “Analysis: Ongoing uncertainties about identity of new Islamic State leader,” BBC Monitoring, January 24, 2020; reporting by journalist Jenan Moussa on Arabic Al Aan TV. Additionally, it is interesting to note that the U.S. State Department’s press release on the designation of al-Mawla lists one of his aliases as “Abu-‘Umar al-Turkmani,” suggesting his Turkmen origin. Caution must be ascribed to this, however, as evidence exists that the aliases used do not always reflect true origins or ethnicity. Vera Mironova and Karam Alhamad, “The Names of Jihad: A Guide to ISIS’ Noms de Guerre,” Foreign Affairs, July 14, 2017.

[r] This claim that al-Mawla was a private directly contradicts a profile of him that refers to him as “a former officer in Saddam Hussein’s army.” See “Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Mawla a.k.a. Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi,” Counter Extremism Project.

[s] It was also possible—and, indeed, was official policy—for an individual to pay money to reduce the length of mandatory service to 90 days. This could be done at any point in time during someone’s service.

[t] One possibility which has been suggested is that perhaps al-Mawla’s graduate studies were part of a long-term strategy by ISI to cultivate religiously educated individuals, either by sending them to receive such studies or simply focusing on them for recruitment purposes. Both al-Mawla and al-Baghdadi pursued higher education in religious studies in the same general timeframe, albeit at different universities (al-Mawla in Mosul and al-Baghdadi in Baghdad). Al-Mawla pursued a master’s degree while al-Baghdadi completed his doctorate. Daniel Milton, “The al-Mawla TIRs: An Analytical Discussion with Cole Bunzel, Haroro Ingram, Gina Ligon, and Craig Whiteside,” CTC Sentinel 13:9 (2020).

[u] Of course, it could also be that he was trying to minimize his level of commitment to the group. However, given that at this point al-Mawla was now two and a half weeks into his detention and had just finished confessing to being the leader responsible for ISI’s interpretation of Islamic law in Mosul, such a minimization seems out of place. TIR C.

[v] Or simply did not view them as relevant to his ISI timeline because they were with an insurgent group other than ISI. Milton, “The al-Mawla TIRs: An Analytical Discussion.”

[w] This likelihood is suggested by one of the TIRs which starts by stating that “Detainee repeated previously reported information about his initial recruitment into ISI.” TIR A.

[x] For example, in one TIR, al-Mawla seems to indicate that the overall leader of ISI in Mosul changed at least twice in the space of a few months due to the individuals being captured by coalition forces. TIR B. If such churn was common in leadership positions, a quick rise may have occurred out of necessity.

[y] It is also interesting to note that prior CTC research demonstrated that violence perpetrated by al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI) and ISI disproportionately harmed locals, not coalition forces. Scott Helfstein, Nassir Abdullah, and Muhammad al-Obaidi, Deadly Vanguards: A Study of al-Qa’ida’s Violence Against Muslims (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2009).

[z] The TIR does not indicate whether this was a U.S. or Iraqi official. Although not necessarily common practice, U.S. military forces would sometimes bring Iraqi judges or prosecutors in to speak with a detainee in an effort to obtain evidence that could be potentially useful at trial, as confessions made in the presence of such individuals were generally the only type of confession considered valid in judicial proceedings. The authors cannot be sure that this is what happened in this case, although it seems plausible. Annexstad, p. 78; Chesney, p. 569.

[aa] The fact that a number of people named by al-Mawla are already in custody is interesting in and of itself for two reasons. One, it raises the possibility that, on some level, he was providing information of relatively less value, as those individuals were already in custody. If this was true, it may support a point raised by some of the panelists about prior training on how to deal with interrogations. Milton, “The al-Mawla TIRs: An Analytical Discussion.” Of course, such information might not have been completely useless, as that information could still have been used against those individuals in their own interrogations or potential prosecutions. The second point raised by al-Mawla’s knowledge of so many alleged ISI members already in detention is that perhaps he knew as many of them as well as he did because of longer relationships than those suggested in his TIRs. Although he is careful not to say that he knew any of them before joining in early 2007, the possibility that he was covering his tracks cannot be ignored. Of course, another possibility is that he simply became acquainted with them at the detention facility itself, although the details he shares consistently over the course of his TIRs casts doubt on that possibility.

[ab] For this search, the authors relied on the full names of individuals as listed at the end of TIR B.

[ac] Some of the details across these two sources, the TIRs and the payment spreadsheet, seem to corroborate that these individuals are the same. For example, not only are full names the same, but also each one of the individuals listed has an identification number in the payment spreadsheet that corresponds to the Ninawa province. Additionally, some of the individuals are described by al-Mawla as working on the left or right side of Mosul, and this also matches what appears in the Islamic State payment spreadsheet. In fairness, not all of the details are consistent: sometimes al-Mawla described an individual as working on the left or right side, whereas the payment spreadsheet had them working on the opposite site. The aliases used by al-Mawla are also not necessarily the same as those listed in the spreadsheet, although one might expect aliases to have changed.

[ad] One individual’s estimated age was 16, which cast some doubt on whether this individual was actually the person mentioned in al-Mawla’s TIRs or whether the birthdate was incorrectly entered in the payment spreadsheet.

[ae] The individuals who may still be in custody, ironically, appear to have remained on Islamic State payment spreadsheets through at least late 2016, suggesting their families received money from the group that is now headed by the very individual whose testimony may have played a role in keeping them in prison.

[af] There are slight variations in the spelling of this individual’s name between the TIRs and the RAND study.

[ag] It is not certain he was referring to the same Khalid and Abu Harith as in the RAND study. However, the circumstantial evidence is convincing. Not only do the figures in the RAND study share the same name as the figures named by al-Mawla, but these are all figures alleged to have been in and around Mosul during this same timeframe. Additionally, the RAND study specifies that Khalid and Abu Harith occupied important roles in the media and administrative units, and al-Mawla lists the leaders of each of these units (actually drawing a line-and-block chart in the case of the media), with Kahlid at the top of the Mosul media unit and [Abu] Harith at the top of the administrative unit. TIR C; Patrick B. Johnston, Jacob N. Shapiro, Howard J. Shatz, Benjamin Bahney, Danielle, F. Jung, Patrick K. Ryan, and Jonathan Wallace, Foundations of the Islamic State: Management, Money, and Terror in Iraq, 2005-2010 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016).

[ah] There is some confusion as to the specific position of Abu Qaswara in the ISI leadership hierarchy. Several have him tagged as the second-in-command in the group. Fred W. Baker III, “Coalition Forces Kill al-Qaida in Iraq’s No. 2 Leader,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 15, 2008; “Swedish ‘al-Qaeda leader’ killed in Iraq,” The Local – Sweden, October 15, 2008; “U.S. military: Senior al Qaeda chief killed in Iraq,” CNN, October 15, 2008. It is important to note, however, that the U.S. government may have incorrectly assumed that Abu Qaswara was second-in-command because of a deliberate effort by ISI to obfuscate the leadership structure. Even in this case, he was still a high-ranking figure, likely third-in-command. Kyle Orton, “Mohamed Moumou: Islamic State’s Commander of the North,” Kyle Orton’s Blog, January 28, 2017.

[ai] Per reporting at the time, this operation seems to have been a targeted operation, not merely one in which Abu Qaswara was an incidental casualty. “U.S. military: Senior al Qaeda chief killed in Iraq.”

[aj] According to the U.S. government, “As one of ISIS’s most senior ideologues, al-Mawla helped drive and justify the abduction, slaughter, and trafficking of the Yazidi religious minority in northwest Iraq and also led some of the group’s global terrorist operations.” “Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Mawla Up to $10 Million Reward,” September 2, 2020; Paul Cruickshank and Tim Lister, “Baghdadi’s successor likely to be Iraqi religious scholar,” CNN, October 29, 2019; Paul Cruickshank, “UN report warns ISIS is reasserting under new leader believed to be behind Yazidi genocide,” CNN, January 29, 2020.

[ak] According to the text of the agreement, it entered into force on January 1, 2009. “Agreement Between the United States of America and the Republic of Iraq On the Withdrawal of United States Forces from Iraq and the Organization of Their Activities during Their Temporary Presence in Iraq,” November 17, 2008; Michael J. Carden, “President signs security pact with Iraq,” American Forces Press Service, December 16, 2008.

[al] According to press reporting, the United States held approximately 22,000-26,000 individuals in detention facilities across Iraq in 2008, with Camp Bucca’s capacity being approximately 18,580 individuals. When Camp Bucca closed in 2009, some reports mentioned that a total of at least as many as 100,000 individuals may have been held in custody by the United States since the beginning of military operations in 2003. Alissa J. Rubin, “U.S. military reforms its prisons in Iraq,” New York Times, June 1, 2008; Alissa J. Rubin, “U.S. Remakes Jails in Iraq, but Gains Are at Risk,” New York Times, June 2, 2008; Michael Christie, “U.S. military shuts largest detainee camp in Iraq,” Reuters, September 17, 2009.

[am] Al-Khazali was a Shi`a Iraqi militant who broke away from Muqtada al-Sadr and carried out operations against U.S. and coalition soldiers. Captured in early 2007 by British military forces, al-Khazali provided a wealth of information over the course of nearly 100 different sessions. Although al-Khazali was released in 2010, his TIRs remained classified until February 2018 when they were released by the U.S. government. Bryce Loidolt, “Iranian Resources and Shi`a Militant Cohesion: Insights from the Khazali Papers,” CTC Sentinel 12:1 (2019): pp. 21-24. Another example of the use of TIRs to understand a difficult problem can be found in previous CTC research regarding Iranian strategy in Iraq, which relied on declassified TIRs of militants fighting in Iraq to better understand facilitation routes between Iraq and Iran, as well as the intentions of Iran with regard to Iraq in the future. Joseph Felter and Brian Fishman, Iranian Strategy in Iraq: Politics and “Other Means” (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2008).

[2] Cole Bunzel, “Caliph Incognito: The Ridicule of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi,” Jihadica, November 14, 2019.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Paul Cruickshank and Tim Lister, “Baghdadi’s successor likely to be Iraqi religious scholar,” CNN, October 29, 2019; Martin Chulov and Mohammed Rasool, “Isis founding member confirmed by spies as group’s new leader,” Guardian, January 20, 2020; Husham al-Hashimi, “Interview: ISIS’s Abdul Nasser Qardash,” Center for Global Policy, June 4, 2020.

[6] “Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Mawla: Up to $5 Million Reward,” Rewards for Justice, August 21, 2019; Cruickshank and Lister; al-Hashimi.

[8] See the Combating Terrorism Center’s website at ctc-westpoint.go-vip.net

[9] Author correspondence with U.S. State Department officials.

[11] Alissa J. Rubin, “U.S. military reforms its prisons in Iraq,” New York Times, June 1, 2008.

[12] “FM 2-22.3 (FM 34-52) Human Intelligence Collector Operations,” Department of the Army, September 2006, chapter 5, pp: 15-23.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Chulov and Rasool; “Al Mawla: new ISIS leader has a reputation for brutality,” Agence France-Presse, July 21, 2020.