Abstract: When it comes to counterterrorism, the United States has been living through an inflection point. It wants to focus less on terrorism so it can place more emphasis on strategic competition, but key terrorist adversaries remain committed. The terrorism landscape and the approaches used by key terror adversaries have also been evolving. The United States and its partners have been placing various forms of pressure against priority networks such as the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida in key locations to keep the threats these groups pose degraded, and to restrict their ability to conduct external operations and other impactful acts of terror. But over the past two years, there have been growing signs that the Islamic State is evolving around the pressure that has been placed against it, developments that highlight the limits of existing CT pressure approaches and the need for those approaches to evolve. This article introduces two frameworks: 1) a framework to help conceptualize non-state VEO power and CT pressure efforts to degrade those elements of power and 2) a defense and degradation in depth framework that can be used to help strategically guide future CT pressure campaigns. It is hoped that these frameworks provoke debate within the counterterrorism community and that they help the United States and its allies adjust their CT approaches so they can evolve to stay ahead of the threat.

The uptick in attacks and plots linked to the Islamic State and its Central Asian affiliate—Islamic State Khorasan (ISK)— in Europe and other places over the past two years is a cautionary tale. It is a reminder of the steadfast commitment of key salafi-jihadi groups, the persistent threats that these types of networks pose, and the need for ongoing forms of pressure to keep entities such as ISK off-balance and their capabilities, reach, and potential for surprise degraded.

Another lesson from the last two decades is that terror threats rarely stay the same: They change and adapt.1 “The history of global jihadism,” as noted by The Economist, “is one of reinvention under pressure from the West.”2 That pressure has helped to keep the threat posed by the Islamic State and its key affiliates at bay. But over the past two years, there have been growing signs that the Islamic State is evolving around the pressure that has been placed against it. Some key examples include ISK’s March 2024 attack in Moscow, Russia’s deadliest terror attack in 20 years;3 the doubling of Islamic State attacks in Syria in 2024;4 the intensification of local and regional activity by Islamic State affiliates in Africa;5 and the arrest of eight Tajik nationals who entered the United States from the southern border over terrorism concerns and links to Islamic State members.6 As reported by The New York Times, “heightened concerns about a potential attack in at least one location triggered the arrest of all eight men … on immigration charges.”7

These and other data points of concern were underscored by a June Foreign Affairs article by Graham Allison and Michael Morell entitled “The Terrorism Warning Lights are Blinking Red Again,”8 a reference to a phrase that George Tenet used during the summer of 2001 in the lead up to 9/11.9 The title could not have been more ominous, but it was also a reminder about how the United States needs to be careful and that it might not be doing enough on the counterterrorism front to contain the threat. The blinking red lights may have also been a sign that U.S. CT efforts may not be keeping up with the evolution, direction, or pace of the threat. The United States and its partners have been working hard to adjust and to optimize approaches to counterterrorism, but environmental changes have made that an increasing hard thing to do. For example, the United States and its partners today face a more diverse, complex, and ever-evolving threat landscape (which includes a rise in state sponsored terrorism) and need to confront the threats with fewer resources and less attention than they did a decade ago. The United States and its allies must also contend with ongoing technological change that has been “transforming the worlds of extremism, terrorism, and counterterrorism,”10 challenges that are difficult for bureaucracies to respond to in practice.

This article explores the topic of counterterrorism pressure, and it introduces several concepts as well as two frameworks to help guide strategic thinking about CT pressure and how it can be applied and evaluated. It is organized in three parts. Part I describes the risk-optimization conundrum that has been challenging the evolution of U.S. counterterrorism over the past several years. To level set the conversation, Part I also provides a short overview of key counterterrorism instruments and how different CT strategies have sought to integrate them. Part II introduces several concepts, including: 1) a framework to conceptualize violent extremist organization (VEO) power and CT pressure efforts to degrade those elements of power and 2) a defense and degradation in depth framework that can be used to help strategically guide and assess future CT pressure campaigns. Part III applies some of the introduced concepts to the case of the Islamic State to highlight their practical utility and application.

PART I: The Problem and CT Pressure Tools

The Risk-Optimization Conundrum: Key Considerations and Caveats

The United States’ shift in 2018 to strategic competition—with more emphasis and priority placed on near-peer threats—was a move that was overdue. Since then, the U.S. counterterrorism community has been navigating what that shift means for the CT enterprise in practice, what tradeoffs it entails, and how the enterprise can evolve, all so that it can create space for the United States to focus on strategic competition while also protecting the American people against a diverse and committed range of terror threats. This challenge has been underpinned by a principal conundrum. Networks such as the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida, for example, cannot be left alone. They are committed and persistent. As a result, consistent and sustained forms of counterterrorism pressure are required to keep these networks off-balance and to degrade, and limit, their capabilities, reach, and ultimately the type of threats they pose. But what level of pressure is ‘enough’ or ‘sufficient’ to keep the threats these (and other) terror networks pose to the U.S. homeland and U.S. interests contained is much less clear.

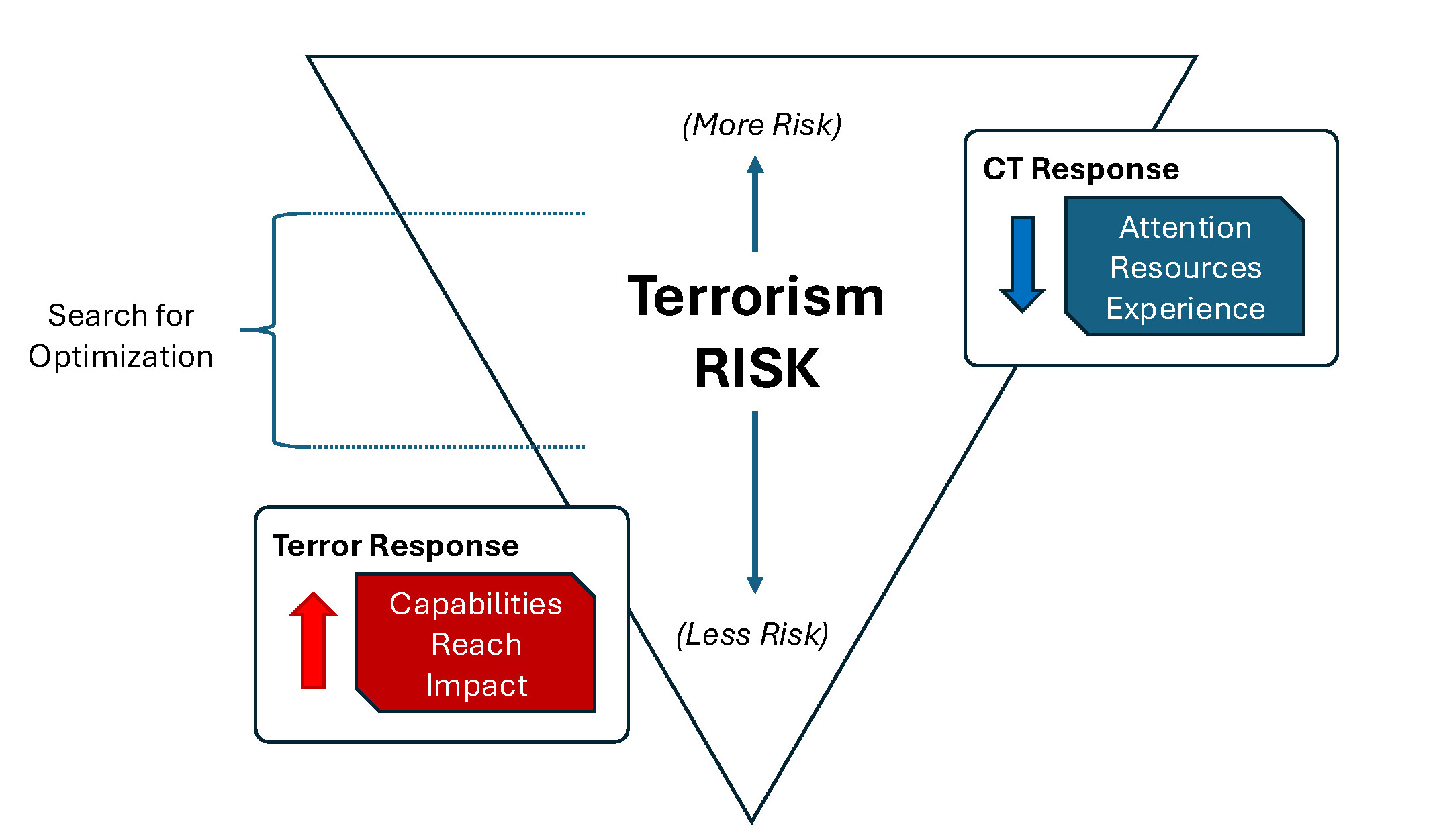

This conundrum is highlighted by Figure 1, which attempts to visualize how the United States is trying to optimize its CT efforts in relation to risk—to apply enough pressure, and devote enough resources, to keep key terror movements off-balance so that the maximum amount of time, attention, and resources can be transitioned to strategic competition priorities.

In theory, as more CT pressure is placed against a network, the level of terrorism risk goes down. Likewise, as less CT attention and resources, and as a result pressure, is applied against committed terror networks the terrorism risk goes up. As part of its efforts to make efficient use of government resources, the U.S. CT enterprise has been exploring, and trying to identify, how CT pressure can be optimized. This pursuit is conceptually reflected by the ‘Search for Optimization’ bracket on the left of Figure 1, which tries to situate CT pressure along a sliding scale of risk.

While theoretical in many respects, the conversation is also an important and practical one, as having a better sense of the issue can help the CT enterprise to be more intentional about how it seeks to manage risk. The approach, though, is not without its own share of hazards, and important cautions and caveats should be considered. For example, given the diverse nature of today’s terrorism threat and various unknowns—or less well knowns—it is important to be cautious in the quest to find a minimal level of CT pressure, as it suggests that counterterrorism, and counterterrorism impacts, can be scientifically approached or quantified. Further, while the United States and its partners have learned a lot about the Islamic State and other terror networks over the past decade, there is still a lot that the community does not know, and likely will not have the ability to know with good certainty about the posture, inner-workings, and standing of key VEOs for the foreseeable future. This ‘we only know what we know’ issue is also compounded by the fact that in various locales, the United States has less visibility into the inner workings of key VEO networks, not more, than it had several years ago. Another important cautionary factor to consider is that threat networks evolve and adjust their approaches in response to pressure—which highlights the dynamic way in which terror and counterterror entities interact and adapt in relation to each other. Those changes, or the direction of those changes, are not always apparent or immediately visible.

This places the idea, or pursuit, of identifying a minimum amount of pressure more into the realm of art than science, and the CT community would be wise to not be dogmatic about, or rigidly beholden to, what it believes should be the minimum amount of pressure that should be applied to entities such as the Islamic State (or other terror networks). This is because it assumes that such a formula exists and that terrorism risk, and the dynamics of surprise, can be controlled. Those risks can certainly be managed, but the past two decades of CT experience provide plenty of evidence that highlights how even when key networks are placed under a considerable amount of pressure, they can still find gaps and seams to exploit, and ways to attack. Thus, efforts that aim to quantify minimum amounts of CT pressure should be viewed as a general guide that needs to remain flexible and responsive to evolving conditions and change, rather than as a doctrinal number or level. The same ‘need to remain flexible’ idea should also be applied to the different types of pressure placed against VEOs, as predictable CT approaches arguably make it easier for terror groups to adapt and regenerate around those forms of pressure over time.

CT Instruments and the Orchestration of Pressure

While CT pressure efforts are operationally driven by the various instruments of counterterrorism, they are, or should be, guided by strategy. In addition to outlining key goals and areas of focus, strategy sets the vision for how different instruments of counterterrorism, including kinetic and non-kinetic forms, should be brought together and orchestrated. To level set what is meant by pressure, this short section outlines key CT instruments. It also discusses how different counterterrorism strategies have conceptually sought to strategically orient these instruments.

There are different ways to bucket the instruments of counterterrorism. One well-known framework is the diplomatic, informational, military, and economic (DIME), and the DIME-FIL (which also includes finance, intelligence, and law enforcement), model. There are also the similar categories – diplomacy, criminal law, financial controls, military force, intelligence—that U.S. intelligence community veteran Paul Pillar outlined in his classic article “The Instruments of Counterterrorism.”11 A brief overview of key instruments relevant to CT today follows.

Diplomacy: At a high level, diplomatic activity helps to shape, enable, and set the conditions for counterterrorism actions and campaigns to take place, or to enhance their positive, or limit their negative, effects. For example, diplomatic activity is critical for coalition building, facilitating access and placement for operational CT forces, influencing host nation CT actions, enabling local partnering and security cooperation, and overseeing hostage and other negotiations. Signaling—whether viewed through the lens of deterrence, or through specific tools such as the U.S. State Department’s Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) designations list—is another important element that diplomacy brings to counterterrorism.

Military Force and Foreign Kinetic Activity: Like diplomacy, military contributions to CT are multi-faceted. The most discussed area is direct action, which can include contributions from military forces and other government elements. These types of unilateral or partnered operations can take the form of precision strikes or raids to remove or capture key VEO leaders, to degrade VEO infrastructure or specific VEO capabilities (e.g., strikes against locations where money or weapons are stored), or achieve other effects.

Security Cooperation: Security cooperation is another key mechanism that is used to develop, augment, and reinforce other forms of CT pressure. Through global train and equip programs, defense trade and arms transfers, international education and training initiatives, and institutional capacity building projects, the U.S. government helps partner nations to develop their CT capacity and capabilities. If executed well, these types of efforts can help specific countries to combat VEOs on their own and to apply pressure against key networks over the longer term.

Law Enforcement and Criminal Law: As noted by Pillar, “the prosecution of individual terrorists in criminal courts has been one of the most heavily relied upon counterterrorist tools.” While the contributions of local, tribal, state, and federal law enforcement entities are rooted in the forensic and investigative actions they take to charge, arrest, and prosecute terrorism suspects (and their enablers), the law enforcement community makes other important CT contributions. Examples include community outreach, measures taken to harden and protect key infrastructure, and engagement with international law enforcement partners.

Intelligence: Intelligence cuts across all dimensions and instruments of counterterrorism, from enabling operations to preventing acts of terrorism in the first place. It includes collection and analysis of different types of intelligence, such as human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), geospatial intelligence (GEOINT), and open-source data (OSINT).

Resource Controls and Counter Threat Finance: Like any organization, terror networks need resources to survive, and they also need to be able to store and move financial and other resources. The United States and its partners have developed various sanctions regimes to freeze or seize assets used by individual terrorists, entities, and their supporters, and to prohibit access to sensitive technologies and dual use items. Key tools in the U.S. context that enable this activity include Executive Order 13224, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Specially Designated Nationals List, and Export Control actions taken by the U.S. Commerce Department.

Terrorist Travel: Another pillar of counterterrorism activity involves preventing the movement of terrorists and individuals with concerning ties to terrorism. The U.S. government’s approach to this issue is layered, and it involves inputs from multiple U.S. departments and agencies. For example, it includes watchlisting data generated by the Departments of Defense and Treasury and FBI, and information shared by foreign partners. These data inputs are designed to complicate and prohibit terrorist travel abroad, and to ensure that individuals with terrorism ties are prevented entry into the U.S. homeland by frontline law enforcement entities such as U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents.

Digital Actions: The rise in social media and digital platforms over the past two decades has broadened and diversified the counterterrorism landscape in profound ways. One important change is that it has led to an increase in the number of private companies “who either have been meaningfully shaping, or have a role in, the world of counterterrorism and how specific counterterrorism actions or responses take place.”12 This includes companies such as Meta, YouTube, and Discord, that—to varying degrees—promote policies or engage in activity on their platforms that are designed to limit extremism or how their platforms might be used to promote an act of terrorism (e.g., Livestreaming, access to an attacker’s manifesto, etc.). In addition to corporate actions that can be pursued unilaterally, through consortiums (e.g., Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism-GIFCT), or at the behest of a government or in partnership with it (e.g., some of the activity of Europol’s Internet Referral Unit), digital CT actions can also encompass offensive cyber operations to deny or destroy terrorist cyber resources and online influence and counterinfluence activities.

Safe Communities and Societal Resilience: Approaches to counterterrorism also involve efforts focused on both the left (prior to an incident) and right (after an incident) sides of terrorism. This includes programs that promote healthy and safe communities and that aim to identify and prevent individuals and organizations from engaging in terrorism and political violence in the first place, or that provide off-ramps to radicalized individuals (e.g., intervention and deradicalization initiatives). It also includes initiatives that promote societal resilience to terrorism that help societies to recover from acts of terror after they occur.

Strategy provides a framework for how these different CT instruments—the mechanisms of CT pressure—should be brought together so their collective utility and power can be actualized. As Pillar noted: “Every tool used in the fight against terrorism has something to contribute, but also significant limits to what it can accomplish. Thus, counterterrorism requires using all the tools available, because no one of them can do the job. Just as terrorism itself is multifaceted, so too must be the campaign against it.”13 Identifying the right mix of instruments is critical, but being flexible and adjusting where and how that mix is applied, given changing conditions, is arguably just as important for CT strategies to be effective, and to remain effective.

Since 9/11, different countries and administrations have framed their approaches in different ways. For example, the United Kingdom’s counterterrorism strategy (CONTEST), which serves as a model for many countries in Europe, organizes CT activity around four ‘P’ pillars: prevent, pursue, protect, and prepare.14 In its first term, the Trump administration’s CT strategy framed its approach around six key lines of effort: 1) pursuing terrorists at their source; 2) isolating terrorists from financial, material, and logistical sources of support; 3) modernizing and integrating a broader set of tools and authorities; 4) protecting U.S. infrastructure and enhancing preparedness; 5) countering terrorist radicalization and recruitment; and 6) strengthening the CT abilities of international partners.15 The Biden administration’s approach, as reflected in the declassified version of National Security Memorandum 13 (NSM 13), embraces seven lines of effort.a Those seven lines share a lot of common ground with the Trump administration’s CT strategy in its first term, but they are framed differently.

As the United States looks forward on the CT front, it is important that any future CT pressure effort or campaign be nested within, or designed to support, a broader CT strategy—and that it considers policy implications, including constraints, and practical feasibility, too.

PART II: CT Pressure Concepts and Frameworks

VEO Power and CT Pressure Targets: Core Areas of Focus

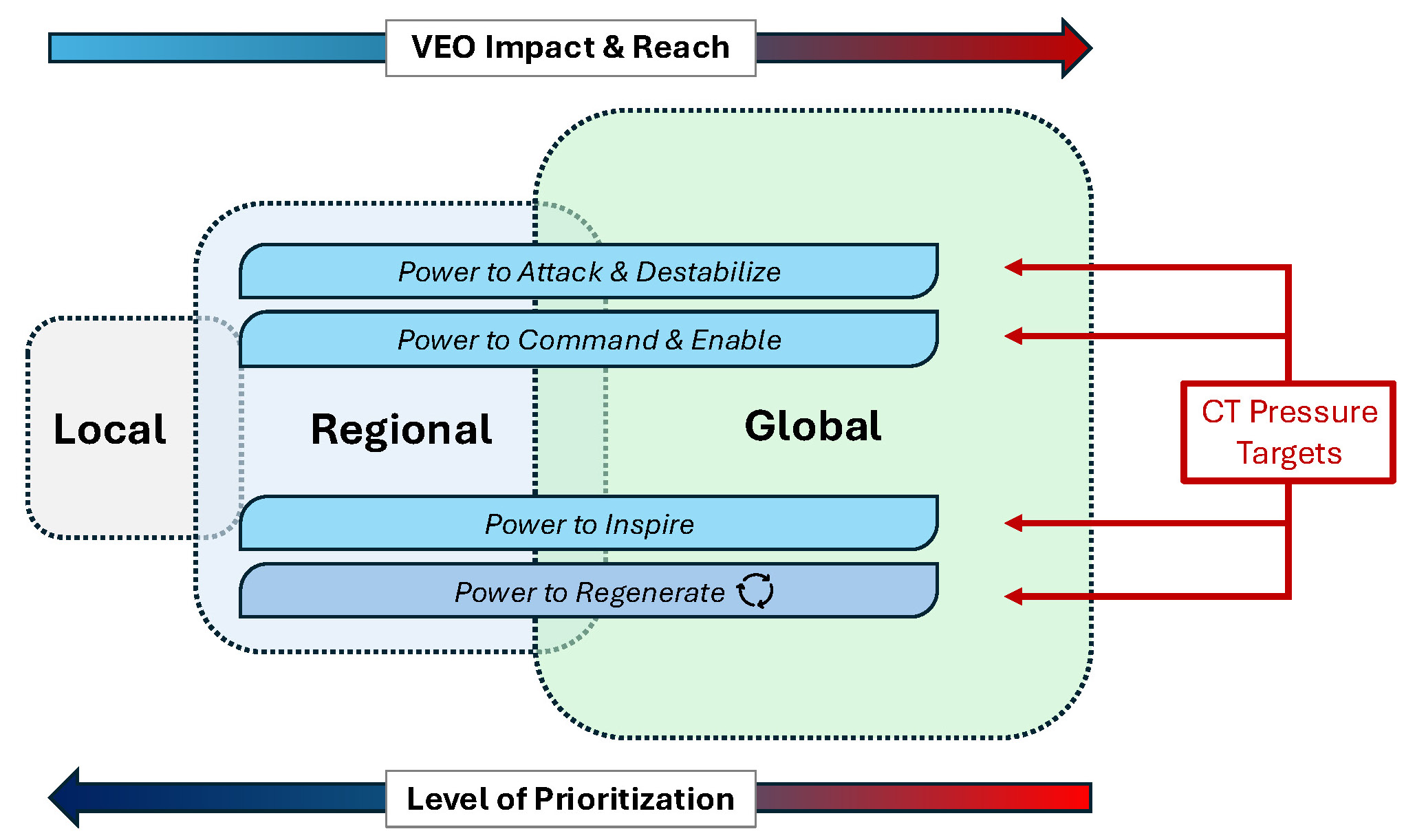

This section introduces a new framework to conceptualize non-state VEO power and CT pressure efforts to degrade those elements of power.b The framework is centered around a network’s or movement’s ability to operate within and across local, regional, and global levels. While many VEO groups begin their campaigns of violence locally and will remain locally focused, the targeting interests and priorities of other VEOs evolve, and some—such as the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida—have global ambitions from the start. The arrow at the top end of the graphic is designed to illustrate how the danger a VEO poses to U.S. interests and global security becomes more concerning as its operational impact and reach, as reflected by its targeting preferences, moves from left to right—from local to regional and global. This is not to suggest that VEO groups that have not yet ‘gone global’ and that remain focused regionally or locally are not a CT concern or priority (some are), but rather that VEO entities that operate across all levels are the most concerning and deserving of U.S. CT pressure and attention. That aspect is captured by the ‘Level of Prioritization’ arrow at the bottom of the graphic in Figure 2. This arrow, which moves from right to left, captures how the level of U.S. prioritization, and as a result CT pressure, is deeply influenced by a VEO’s impact and reach.

One important issue to consider is when, at what point, across a VEO’s lifecycle does it make sense to apply or reapply CT pressure.16 While the answer may seem simple on the surface—‘it should be when VEOs have demonstrated global reach and impact’—how the United States and its partners approach the question can also have a bearing on the efficiency and potential long-term sustainability of CT efforts. For example, is it more efficient and effective to continue to surge, apply, and reapply pressure on VEOs when they reach, are close to reaching, or regain global capability status? Or would it be more efficient over the longer term to apply consistent forms of pressure against key networks that have global ambitions but who still operate at the local and regional levels so their capabilities can be degraded earlier, before they reach the global level? While the latter approach might require more upfront investment, it could also prove more efficient over the longer term. Both approaches involve tradeoffs and different types of risk, however. Applying pressure against local and regional groups, for example, may embolden them or provide incentives for them to develop global capabilities faster. But if governments wait too long to apply CT pressure against a local or regional group that is poised to expand, they could also be locking themselves into providing off-and-on surge support, which can also be resource intensive.

In addition to the ‘when’ to apply pressure question, consideration should also be given to what types of pressure would be most effective against different VEOs, where those forms of pressure can be applied, and what level of pressure intensity and periodicity will lead to ideal outcomes.

A second component of the framework is the four high-level elements of VEO power. These include a VEO’s: 1) power to attack and destabilize, 2) power to command and enable, 3) power to inspire, and 4) power to regenerate.c The local, regional, and global construct can be used to evaluate a VEO’s power in relation to each of the four areas. For example, a VEO might be assessed as having the ability to inspire at the global level, but not have the power to conduct attacks at that level. These four elements of VEO power can also be used to orient CT pressure (and CT strategy more broadly) as part of a campaign to degrade a VEO’s ability across the four power areas. While these four VEO powers can be understood as distinct power areas, there can be interplay and dependencies between them, too. A network’s power to inspire, for instance, can also enhance that network’s ability to regenerate. A brief explanation of each of the four VEO power areas follows.

Power to Attack and Destabilize: This power area includes a VEO’s ability to conduct attacks within and across geographic areas and its ability to destabilize or complicate environments. While a VEO’s ability to conduct attacks, especially global terror operations, is a more straightforward way to assess the danger a VEO poses to U.S. interests and international security, a VEO’s ability to destabilize is also an important factor to consider. This is because a VEO’s ability to destabilize, especially its ability to consolidate control over a specific location or progressively destabilize wider geographic areas, can evolve into a strategic problem for the United States and its partners. This can take various forms, such as a VEO overthrowing, or assisting in the overthrow of, a country’s government or a VEO being able to threaten several regional governments and gain control over territory. These developments can help a VEO to develop safe haven, that provide networks with more time and space to plot and plan, to train, and to consolidate their control and influence. While not the norm, the October 7th attack highlights how regional destabilization can be triggered by a terror attack, which highlights how these two areas—attack and destabilize—can converge.

Power to Command and Enable: This power area is designed to evaluate a VEO’s ability to command and enable core elements of the network, its affiliated networks, its members, and more loosely connected individuals across local, regional, and global levels. It includes a VEO’s ability to lead, to maintain unity and cohesion within and across its movement (e.g., ensuring that its component parts are engaging in activity that is aligned with the movement’s vision, ideology, and goals), and to provide direction, resources, and technical know-how that enables cells and individuals to act.

Power to Inspire: This power area focuses on a VEO’s ability to inspire and motivate across local, regional, and global levels through in-person and digital means. It includes a VEO’s ability to brand itself; to provide a compelling vision and to effectively market that message; to recruit people and bring resources into its movement; to retain recruits and key supporters (and keep them motivated); and to inspire disconnected or loosely connected individuals to conduct acts of violence, or engage in operational activity, on behalf of the network. Another way to view a VEO’s ability to inspire is the capability it has to ‘push’ out and ‘sell’ its ideology and vision so it results in a ‘pull’ of individuals and resources that the network can use to consolidate its position or evolve into new areas.

Power to Regenerate: The resilience of key terror networks, such as the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida, and their ability to rebuild and regenerate their capabilities after loses and setbacks has proven to be an enduring feature during the post-9/11 period. This is because these types of VEO networks and their ideologies are focused on long-term success, even if it entails considerable suffering and setbacks spread across decades. This is a core reason why the threats these networks pose are persistent. Thus, a terror network’s ability to regenerate is a key factor that needs to be addressed as part of any CT pressure approach or CT strategy. This is so the ability and power of key VEO networks, and their supporters, is degraded not just over the short-term (e.g., through the removal of key leaders and other actions, such as sanctions), but also so their appeal, capabilities, and ability to sustain themselves is also degraded over a longer period of time.

This will likely require learning more about the strengths and vulnerabilities of key VEO networks, and in experimenting with new approaches. For example, for the past two decades a core element of al-Qa`ida’s senior leadership has received shelter and support from the Iranian government.17 A pressure campaign focused on al-Qa`ida’s regenerative capacity would devise ways—beyond what has already been done—to expose, further degrade, weaponize, or further problematize the support that Iran provides to the group. While those pressure approaches could share common ground with other efforts, such as leadership decapitation approaches focused on the Islamic State in Syria, they will also arguably need to be different given differences across operating environments. Another strand focused on regenerative pressure could target financial resources and aim to identify key funders and sources of financial support that have received less attention. Emphasis could also be placed on disrupting or subverting VEO supply chains, particularly those that involve dual-use technologies or other key inputs.

High-level benchmarks could be created for each of the four VEO power areas, and these could be used to evaluate the evolution of a VEO network’s capabilities and the effectiveness of a CT pressure campaign over time. For example, one high-level metric that could be used for the ‘Power to Attack and Destabilize’ area is the number of attacks a VEO network was able to execute, and the failed plots it was not able to bring to fruition, measured across local, regional, and global levels on a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis. Other metrics for that power area could include the size and significance of the territory a VEO network controls or over which it wields meaningful influence, or a VEO’s ability to regionally expand the reach of its operations. Similarly, global data on the number of successful or disrupted plots involving inspired individuals, organized by specific VEO networks, could be compiled to inform and measure time-bound change in a VEO’s ‘Power to Inspire.’ The number of individuals arrested for providing material support to a VEO could also be used to evaluate that aspect of VEO power. To help scale the effort, data collection for some or all benchmarks could be automated or leverage data inputs from existing approaches. The indicators for each power area could be measured as a scorecard and could be used to inform and modulate where and how CT pressure is applied. For example, if ‘Power to Inspire’ metrics point to a VEO having achieved more power in that area over an annual period, that finding could inform kinetic targeting strategies, digital forms of pressure, and/or outreach efforts to technology partners.

Defense and Degradation in Depth: A Framework to Guide CT Pressure

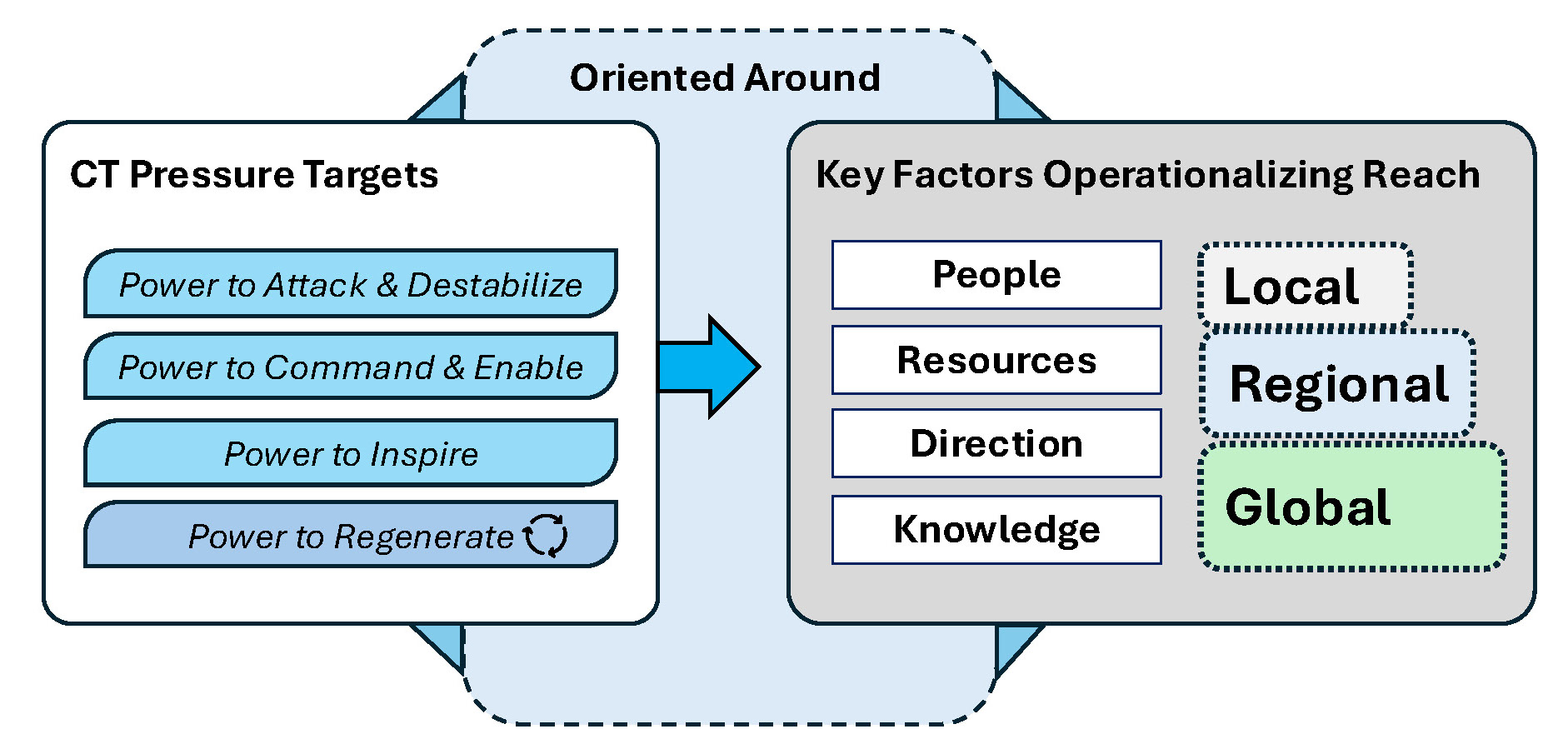

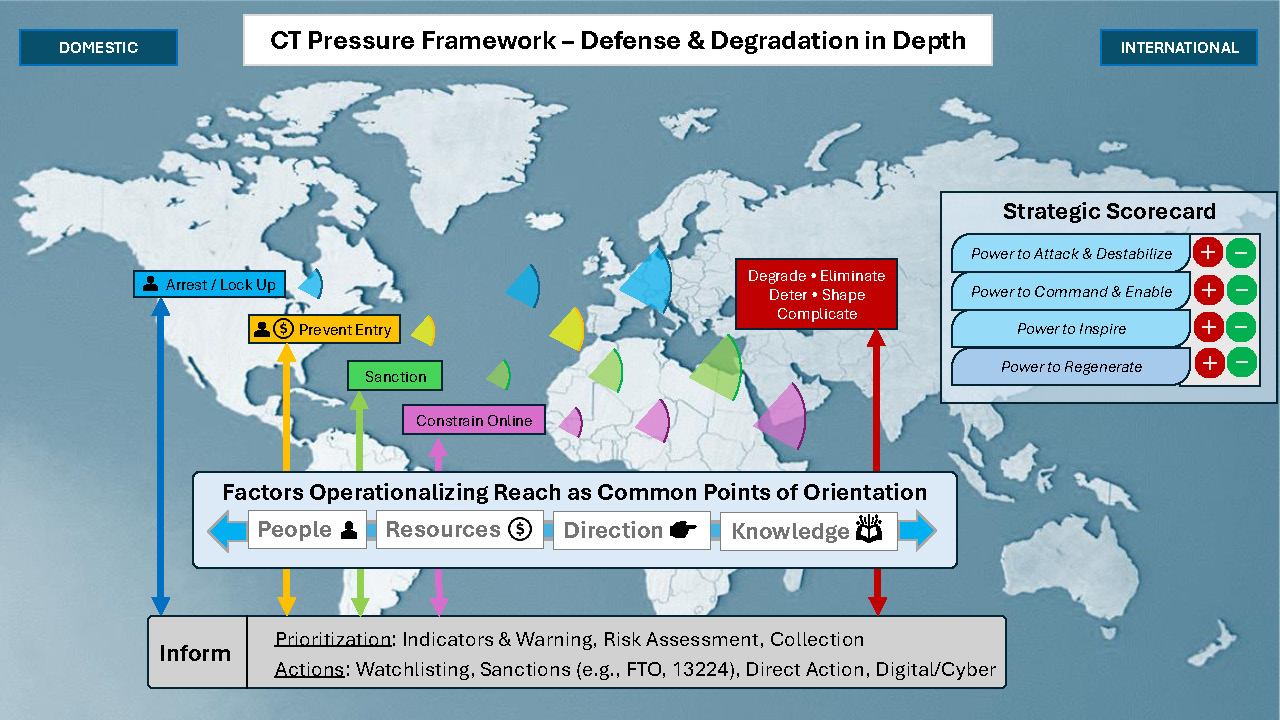

This section builds on the previous one, and it introduces two additional concepts that can be used to operationalize and evaluate CT pressure efforts. The first concept (Figure 3) identifies common points of orientation that can help guide an interagency CT pressure approach focused on the four VEO power areas just discussed. Since an overarching goal of U.S. and partner CT efforts is to limit the reach and impact of key VEOs across geographic areas, it is recommended that emphasis be placed on key factors that enable VEOs to operationalize their reach, and that these serve as common orientation points to focus interagency CT pressure efforts. Figure 3 identifies four key factors: people, resources, direction, and knowledge. In many ways, these four factors are already points of emphasis for the U.S. CT community, but they are being presented to showcase how CT pressure efforts could be more intentionally oriented around them.

For the U.S. CT enterprise, the operatives of terrorist groups and their resources have been a consistent point of focus for more than two decades; this is something the community is exceptionally good at focusing on. Those two factors, and the need for pressure emphasis on them, are far from new. The importance of, and need to limit, VEO operational direction and technical knowledge transfer are also appreciated by the U.S. CT community. But despite their importance, those two factors can be more difficult to ‘see’ and disrupt, and as a result have arguably received less attention.

An Islamic State plot disrupted in 2017 highlights how these four enabling factors come together. That year, Australian authorities arrested two brothers, Khaled Khayat and Mahmoud Khayat, living in Sydney who tried to place a bomb on an Etihad flight and later also sought to conduct a terror attack in Australia using an improvised chemical weapon.18 In addition to the Australia-based Khayat brothers, two other people—both Islamic State operatives based in the Levant—played critical roles in the plot. This included Tarek Khayat, another brother of Mahmoud and Khaled, and Basil Hassan. One of the unique and innovative features of the plot was that the “Islamic State had provided direct logistical support” to the plot “by mailing the [Australia-based] Khayat brothers a partially constructed bomb,” a key resource.19 The package that Islamic State figures sent to Australia from Turkey via DHL “contained a welding machine with an explosive substance hidden inside a copper coil.”20 External direction was also a key feature, as “during the course of the plot” an Islamic State operative “provided guidance and instructions via the Telegram messaging app to the Khayat brother in Sydney.”21 The instructions provided included details “for how to wire the bomb,” a form of knowledge transfer. This involved a technical back and forth as Khaled “repeatedly sent photos to both Tarek and Hassan to demonstrate his progress and seek feedback.” When the plan to smuggle a bomb onto the Etihad flight ran into problems, “Khaled was sent [additional] instructions on how to create a chemical compound that could be dispersed as a lethal gas.”22 The 2017 foiled plot—described as “the most serious Islamic State plot” Australia “has ever faced”23—highlights the importance of the four key enabling factors and how the Islamic State creatively used them in combination to almost pull off a devasting terror attack.

The second concept, Figure 4, introduces a layered, defense and degradation in depth CT pressure framework. While layered defense, or defense in depth, is not a new idea or concept, over the past decade it has not been as well used to conceptually guide U.S. counterterrorism strategy or efforts.d This is unfortunate because the general defense in depth construct can help to strategically orient CT strategy and CT pressure campaigns—and gauge the strategic effectiveness of those efforts.

Some modifications to the general defense in depth concept help bring the idea, and its value, to life. The first is expanding the posture of the concept itself so it includes offensive components as a core element, in addition to those that are defensively focused. One of the key lessons the United States learned from 9/11 and the past two decades of counterterrorism activity is that offensive and persistent forms of CT activity are needed to degrade and disrupt key VEO actors. A defensive posture, even one oriented around defense in depth, is not enough. Figure 4 incorporates the offensive element by positioning the framework around defense and degradation in depth.

The second modification is the overlaying of key CT actions onto the framework. While the examples highlighted in Figure 4—arrest/lock up, prevent entry, sanction, constrain online, and degrade, deter, etc.—are not exhaustive, they highlight how each of these action areas, and how they are approached, can be layered. In many ways, the United States and its partners have already been approaching some of these CT action areas in that type of manner.

The arrest and lock up action area, highlighted in blue, is a useful example. U.S. efforts to identify, arrest, and convict extremists and prevent acts of terrorism are strongly rooted in the U.S. homeland, and include actions taken by the FBI, various DHS components, state, local, tribal, and territorial law enforcement partners, and engagement with civil society organizations, communities at risk, and private sector companies. Through various mechanisms—multi-nationally through entities like Interpol, Europol, and Operation Gallant Phoenix; bilaterally through country-to-country partnerships; and jointly or unilaterally through direct action—the United States can extend both the defensive/protective and offensive/disruptive elements of the arrest/lock up area. This extension is represented by the shaded blue arcs that extend geographically that have a dual purpose. Offensively, they enable and bolster layered mechanisms for the United States to apply CT pressure in different geographic locations, and defensively, they create layered obstacles that complicate VEO efforts. Efforts that aim to prevent entry, sanction, constrain online, and pursue terrorists and their enablers abroad can be guided or bolstered by similar layered approaches.

The framework also includes two types of cross-cutting factors. These include: 1) the four factors—people, resources, direction, and knowledge—that help VEOs to operationalize their reach, which, as discussed earlier, can serve as common points of orientation for CT pressure and 2) data injects from key CT actions that can inform key tasks (e.g., threat prioritization, risk assessments, indicators and warning effort, collection) and tee-up future kinetic and non-kinetic CT pressure approaches.

The framework’s final contribution is a strategic VEO power scorecard,e with the goal being for U.S. CT pressure efforts to be evaluated in relation to the four VEO power areas. Data and metrics from various sources, including CT actions, other U.S. interagency activity (e.g., relevant U.S. Customs and Border Protection enforcement data, etc.), from partners, and open sources could be used to populate and score VEO power across time. Those results could also inform how, where, and in what manner CT pressure efforts should be modulated.

PART III: Applying the Concepts and Frameworks

The Islamic State Case

This final section evaluates the Islamic State in relation to the VEO power score card. It also examines some of the action elements of the defense and degradation in depth framework so that the evaluative capacity and features of the frameworks presented in this article are brought to life.

As a global movement, the Islamic State draws strength from its ideology and vision of the world and its globally distributed array of formal regional affiliates, which provide reach and network resilience. Since losing control of its territorial ‘caliphate’ in 2019, the Islamic State’s core network based in Syria and Iraq has sought to rebuild. Some regional Islamic State affiliates, such as the Islamic State node still active in the Philippines, have followed suit.24 Other regional affiliates—especially those based in West Africa and the Sahel—have intensified their local and regional activity and have made territorial and regional reach gains, while still others including ISK have played a much more active and leading role in external operations over the past several years.

Given its diverse makeup, there are important differences in the strength, orientation, and capabilities of the different Islamic State affiliates. But when the Islamic State is viewed wholistically as a broad-based movement, or system, it has demonstrated an ability over the past two years to make gains across at least three of the four VEO power areas despite considerable forms of CT pressure in some geographic areas. The danger is that the Islamic State continues to make advancements across VEO power areas and/or that its gains intensify.

Power to Attack and Destabilize

Over the past five years, the United States and its partners have placed a considerable amount of pressure on the Islamic State’s core element based in Syria and Iraq. This has included the removal of at least three Islamic State ‘caliphs’ through direct action CT raids in fairly quick succession. That form of pressure has been complemented by pressure being applied against the Islamic State’s mid- to senior-level leadership ranks. For example, since late August 2024 “U.S. forces in the Middle East have killed 163 Islamic State group militants and captured another 33 [militants] in dozens of operations in Iraq and Syria.”25 This included the removal of “over 30 senior and mid-level ISIS leaders.”26

While those operations are important and have made it harder for the Islamic State to function and plan attacks, other data points suggest that the type and form of pressure has not been enough. This is because while the Islamic State “mostly remains on the back foot in Iraq, the U.S. is struggling to contain the group’s growing foothold in Syria’s Badiya.”27 In 2024, “the number of [Islamic State] attacks in Syria has more than doubled … despite an increase in U.S. air strikes.”28 Some analysts believe that the “reality is far worse” though, as the Islamic State “claims only a fraction of its attacks in Syria and Iraq in an apparent effort to conceal its methodical recovery,” which may mask the true picture.29

Just as worrying are signs the Islamic State in its previous core base of Iraq and Syria is reconstituting its external operations capabilities. The commander of U.S. Central Command, General Michael Kurilla, has also warned that “Isis in Syria and Iraq has grown so rapidly that it is again capable of carrying out attacks abroad.”30 f In October, Ken McCallum, the head of MI5, expressed similar concerns about the reconstitution of the Islamic States’ external operations capabilities, with particular concern focused on ISK: “Today’s Islamic State is not the force it was a decade ago … but after a few years of being pinned well back, they’ve resumed their efforts to export terrorism.”31

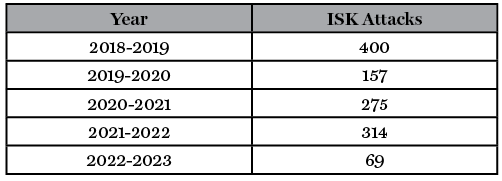

ISK’s power to attack and destabilize has evolved in a different way over the past five years. As reflected in Table 1 below, the network’s ability or interest in conducting attacks in Afghanistan has declined considerably since 2021 and 2022.32 Across the border in Pakistan, the number of attacks attributed to ISK over the same five-year period has remained more consistent, but low.33

Table 1: Attacks in Afghanistan Claimed by ISK, 2018-202334

Since 2017, the Islamic State has claimed responsibility for at least four terror attacks in Iran. This has included attacks in 2017, 2018, 2022, and 2024.35 g While the 2024 attack was claimed by the Islamic State, and not directly by ISK, it is believed that ISK played a key role in its execution,36 h illustrating how external operations involve different inputs from across the movement.37

The drop in local ISK attacks in Afghanistan and the steadier, low-level pace of regional ISK operations is contrasted by the “tick up” in the number of transnational terror plots and attacks that involved inputs or have been tied to ISK over the past two years.38 This has resulted in an “increased external threat from ISIS-Khorasan.”39 As noted by The Economist, the network’s highly lethal attack in Moscow in March of this year “was the clearest warning that Islamic State …, seemingly smashed five years ago, is returning to spectacular acts of international terrorism.”40

The orientation and activity of Islamic State-affiliated networks in Africa have been more locally and regionally focused, but the ability of the Islamic State’s nodes on the continent to destabilize is not dropping; for many, it has increased. As noted by Aaron Zelin in March of this year, “the Islamic State is once again racking up territorial gains around Africa.” For example, “In Mali, [Islamic State] forces seized portions of the rural eastern Menaka region and the Ansongo district in southern Gao last year, while foreign fighters reportedly became more interested in traveling to Wilayat Sahel, the group’s self-styled ‘Sahel Province.’ Elsewhere, [Islamic State] ‘provinces’ in Somalia and Mozambique have taken over various towns in the Puntland and Cabo Delgado regions [in early 2024], further destabilizing the area and in some cases jeopardizing important natural gas projects.”41 There is the risk that “if left unchecked, they could threaten U.S. and Western interests in the future.”42

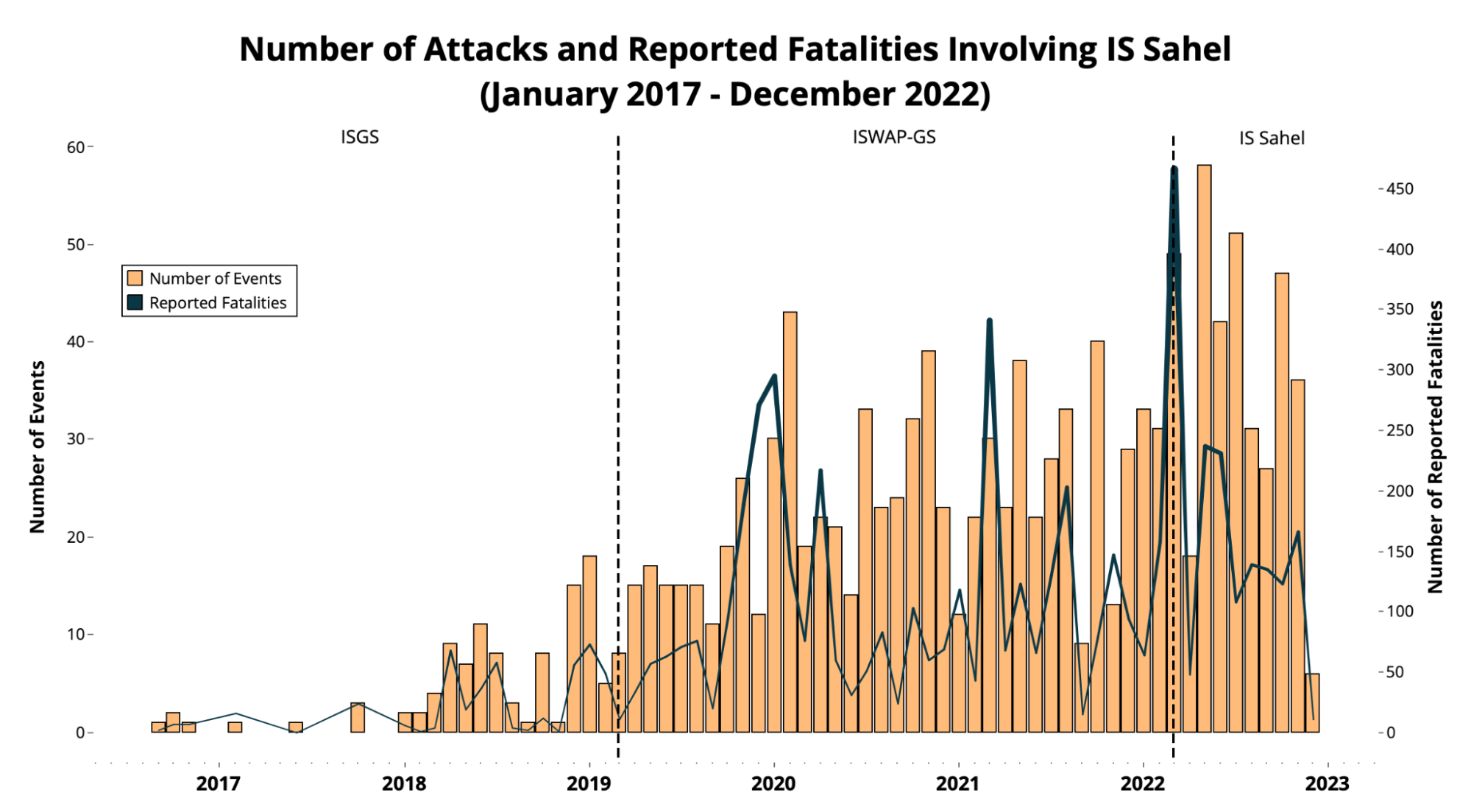

The trendline of attacks conducted by Islamic State Sahel (also known as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara) since 2017 is illustrative of the rise of activity, and the development of operational capacity for key affiliates on the continent.43 It also provides an important counterpoint to the activity of ISK, which has placed more emphasis on external actions than local and regional ones.

Islamic State Sahel Attacks44

Like ISK, Islamic State-Somalia “is a study in contrasts. At home, [in Somalia] its impact is limited. It appears, however, to play an outsize, if still vague, role in the Islamic State’s global operations.”45 When it comes to transnational terrorism, there is growing concern about the network. As noted by Caleb Weiss and Lucas Webber in this publication, “Over the last three years, the Islamic State’s Somalia Province has grown increasingly international, sending money across two continents and recruiting around the globe. There are also growing linkages between the group and international terrorist plots, raising the possibility that Islamic State-Somalia may be seeking to follow in the footsteps of Islamic State Khorasan in going global.”46 While not a global threat today, that same possibility could extend to other Islamic State affiliates in Africa at some point in the future, too.

Assessment: Differences exist across various Islamic State components, but when these data points are viewed in aggregate, the Islamic State’s overarching power to attack and destabilize is up across local, regional, and global levels. Over the past two years, the Islamic State has not been able to conduct an attack in the United States—an important win, but the movement’s external operations capabilities are arguably more developed than they were two years ago, a dynamic that places the U.S. homeland at greater risk.

Power to Command and Enable

It is difficult to assess the Islamic State’s ability to command and enable through open sources, as internal documents produced by the Islamic State and its affiliates and communications within and across the movement’s nodes likely provide much more granular insights about this issue.

One high-level window into the Islamic State’s power to command is the composition of the movement’s global network of affiliates, and whether the number of formal affiliates has grown, reduced in size, or remained steady across time. This is because if the central leadership element of the Islamic State was viewed as not capable or not a useful partner, one would expect various affiliates to be less embracing of the movement and its brand. While the composition of Islamic State affiliates has changed at key periods, the most active and influential regional Islamic State nodes have maintained the affiliation and remained outwardly loyal. This is not to suggest that there have not been disagreements or points of friction between affiliates and the ‘center’i but rather that the number and quality of formal Islamic State partners has remained mostly stable.

In July 2023, the United Nation’s Monitoring Team held the view that “the trend of counter-terrorist pressure prompting ISIL … to adopt flatter, more networked and decentralized structures has continued,” and that this provided affiliated groups with more operational autonomy.47 The report also assessed that the role of the Islamic State’s “overall leader has become less relevant to the group’s functioning.” At the time, member states had “little evidence of command and control of the affiliates from the core leaderships.”48 While that view may have been true in 2023, it is less clear if the same can be said today. However, despite the lack of reporting and public clarity about the role the ‘center’ has recently played in guiding affiliate activity, the United Nations also assessed it had “not had an impact on the level of violence perpetrated by the affiliated groups and their perceived success.”49 Or, in other words, command and control dynamics did not appear to have meaningfully affected affiliate attack campaigns and how those are viewed.

This may be partly because the Islamic State has adapted and made changes in its structure and approach that appear designed to mitigate counterterrorism pressure effects.50 A key lens into these dynamics is the Islamic State’s General Directorate of Provinces (GDP).51 The primary role of the GDP has been to serve as a “bridge between the Islamic State’s central leadership and its various provinces,” with it functioning as a core mechanism through which leaders can “issue orders on how provinces should organize their economic institutions, handle their finances, and pursue their military strategy.” But, as noted by Tore Hamming in this publication, the GDP’s importance and influence has also evolved over time, and it “now allegedly occupies a central position in the execution of external terrorist operations.” Purported internal Islamic State documents covering the 2015-2020 period released online showed that the GDP “has tremendous institutional power within the Islamic State and directs how provinces are organized and set up.”j

These adjustments were not just administrative; they appear to have also been underpinned by key geographic changes. As noted by Aaron Zelin, while the GDP “has previously been based in Syria … new information suggests … at least at the highest levels … [that] it might now have centrality in Somalia.”52 This view is tied to recent reporting that the Islamic State had anointed the leader of its affiliate in Somalia, Abdulqadir Mumin, as its overall leader—the global ‘caliph.’53 Various terrorism researchers are skeptical of the claim, and some have put forward the theory that Mumin may have been appointed to serve as the emir of the GDP instead.54 But regardless of which theory may be correct, they both suggest that the Islamic State is continuing to adapt its organizational structures and approach in response to repeated senior leadership losses that have affected the core network in the Levant. The survival implications of these changes seem clear. As noted by Zelin: “In many ways, the key aspects that animate the Islamic State as an organization (governance, foreign fighter mobilization, and external operations) remain, they have just moved from primarily being based out of or controlled by its location of origin in Iraq and Syria to being spread across its global provincial network.”55 The elevation of Mumin, given his geographic location, speaks to this. The critical role played by other Somalia-based Islamic State leaders, such as Bilal al-Sudani who according to the Department of Defense “was responsible for fostering the growing presence of ISIS in Africa and for funding the group’s operations worldwide, including in Afghanistan” speaks to it as well.56 Other reporting also suggests that the Islamic State’s dispersion strategy is not limited to leadership dynamics but also involves efforts to “diversify … some of their combat power to Africa, to Central Asia.”57

Over the short term, decentralization and dispersion provide depth and are likely to help the Islamic State to enhance its resilience, especially if counterterrorism pressure against other key dispersed command and control nodes remains limited. But, as al-Qa`ida’s experience highlights, over the longer-term decentralization and dispersion could also introduce, or compound existing risks for the group.

ISK’s power to virtually enable, guide, and in various cases direct radicalized individuals located abroad has also evolved into a growing problem.58 Evidence of this is seen in the steady stream of ISK-linked arrests, plots, and attacks over the past two years that involved ISK members providing some form of remote instruction, including its devastating attack in Moscow.59

Assessment: The lack of data inputs makes this power area difficult to assess. CT pressure has degraded the ability of the Islamic State’s core element based in Syria and Iraq to command and enable across the broader Islamic State enterprise. But despite the pressure, other Islamic State elements have generally been able to maintain their operational pace and capacity. In addition, ISK’s ability to enable remote plotters has not diminished; it has arguably grown. The Islamic State also appears to be adapting its organizational structures and posture to limit the impact of CT pressure, reconstitute capabilities, and build resilience across its movement.

Power to Inspire

As noted earlier, a VEO network’s power to inspire can be measured by its ability to offer a compelling vision and market itself, to recruit members, and to inspire individuals located abroad to engage in operational activity—either in direct partnership with the group or on behalf of it.

The Islamic State’s loss of its territorial caliphate in Syria and Iraq has diminished its allure and its ability to inspire the masses of recruits, especially foreigners, that the core node in the Levant achieved during its heyday. But the ability of various Islamic State nodes to maintain or increase their local and regional attacks speaks to the capacity of those nodes, and the Islamic State generally, to remain attractive and to successfully recruit. While far from what it used to be, even the Syria-based fighters of the Islamic State have been able to enhance their operational capacity over the past year, a feat which requires committed recruits. Despite reported challenges in some areas,k manpower does not appear to be a broad issue for the movement.

The Islamic State’s ability to virtually motivate distantly located individuals to align themselves with the movement, to seek formal connections, to reach out for operational guidance, or to conduct acts for the movement (or on its behalf) has also picked up over the past two years.

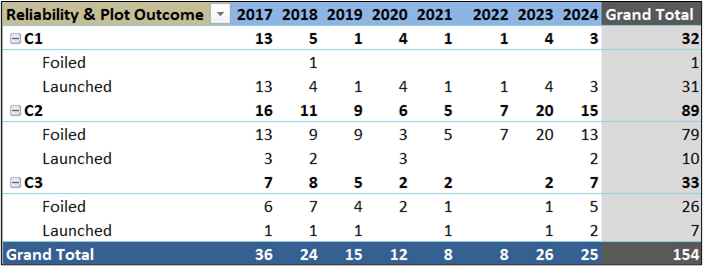

This is particularly evident in Europe. A critical resource in this regard is FFI’s Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED).l The JPED includes data on launched and foiled terror plots in Western Europe since 1994, and results are organized into three reliability categories based on the level of documentation that supports each case.m The most reliable and best sourced cases are C1 and those that are more dubious and not as well sourced are C3. Table 2 below provides a summary of Islamic State-linked plots from 2017 to early September 2024 organized by reliability measure. While C1 cases paint a more measured picture, the broad trend across all data categories is that Islamic State-linked plots have risen in Western Europe over the past two years from a lower period of activity (2020-2022) that coincided with the coronavirus global pandemic. When all C3 cases are excluded, the trend still holds. The collection of cases includes plots tied to single individuals and small groups, a considerable number of cases involving minors, plots with connections to ISK and the Islamic State—some of which involved remote contact and directions being provided, and plots where direct contact with Islamic State nodes or personnel was not publicly apparent.n

Table 2: Islamic State-Linked Plots (Launched and Foiled), 2017-September 2024

The central ‘glue’ that appears to be enabling these plots is the Islamic State’s propaganda combined with its virtual activity and remote enabling. As noted by MI5 head McCallum, “it’s hard to overstate the centrality of the online world in enabling today’s threats.”60 Data from the Washington Institute’s Islamic State Worldwide Activity Map situates the central importance of online activity for the group: “Since March 2023, the IS Activity Map has tracked 470 relevant legal cases in forty-nine different countries. Of these, 103 cases featured some type of IS-related attack plot, 88 involved social media activity or other propaganda, 55 involved financial transfers or fundraising, 42 were related to foreign fighters, and 38 involved recruitment activities.”61

A core element of the Islamic State’s virtual activity involves the use, and weaponization of, encrypted communication apps, with emphasis placed on platforms such as Telegram. For example, “in at least 44 percent of the 57 virtually directed Islamic State plots between 2014 and 2020,” that researcher Rueban Dass studied “Telegram was used as a method of communication.”62 Further, according to Aaron Zelin: “A lot of Islamic State Khurasan Province-related external operations plotting has more to do with recruitment and inspiration online and guidance through encrypted applications than an individual traveling abroad to gain fighting and training experience and then returning home to plot. While this model is not new, it’s the first time we’ve seen it be successful while a group is not in control of territory and shrinking in its local capabilities.”63

The recent plot trends observed in Europe and the evolution of the Islamic State’s virtual approach present threat implications to other areas, including the United States. That issue has not been lost on senior U.S. government CT leaders. For example, in October 2024 Acting Director of NCTC Brett Holmgren noted how “recent attacks and disrupted plots in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Sweden are manifestations of the threat we’re worried about here at home—young, vulnerable lone actors or loosely formed groups, often only connected virtually, drawing inspiration or guidance from ISIS to radicalize online and plan attacks.”64

That worry is well placed because “violent extremists who are not members of terrorist groups remain the most likely to successfully carry out attacks in the United States.”65 Indeed, since 9/11 homegrown violent extremists “have conducted 41 of the 49 terrorist attacks in the United States.”66

According to the Washington Institute’s Islamic State Worldwide Activity Map, which tracks inspired, directed, and guided plots and attacks linked to the group, there was one case in the United States in 2023. In 2024, as of mid-November, there have been five, a considerable rise.67 o

Assessment: The Islamic State’s ability to inspire, and the way it does so, varies across its components, but in aggregate the movement maintains its ability to inspire. This capability is being reconstituted and for some affiliates such as ISK, which has leveraged virtual means and modalities to translate inspiration into more plots and operational attempts, it has grown. When it comes to CT pressure, this is a key area that deserves more strategic thought and attention.

Power to Regenerate

The Islamic State’s power to regenerate is a two-sided coin. One side reflects steps the Islamic State and its partners take to regenerate capabilities. The other side reflects the will and posture of governments and coalitions to continue to apply meaningful forms of pressure to degrade the Islamic State over the short, mid, and longer terms. The regenerative outcome is highly dependent on how the two sides of the coin interact, and how they influence each other.

Like the power to command and enable, it is difficult to study a VEO’s power to regenerate using open sources. This sub-section evaluates the Islamic State’s regenerative capacity in relation to key resources (e.g., manpower and finances), operational capacity (i.e., how it makes use of those resources), and challenges and opportunities that could help the movement to rebuild.

As noted earlier, existing manpower does not appear to be an issue for the Islamic State generally. In certain locations like Syria, there also remains a lot of additional manpower potential that the group could tap into and use to either expand or intensify activity if not managed carefully. This includes some “9,000 Islamic State fighters [who] remain in jails across northeastern Syria.” As reported by The Wall Street Journal:

The group has made no secret of its intention to free its comrades so they can return to the battlefield. Twice this year, insurgents have tried to stage breakouts from detention facilities. In one case, an Islamic State suicide bomber tried to breach the gate of a Raqqa jail in a three-wheeled auto rickshaw filled with explosives. There are also some 43,000 Syrian, Iraqi and other displaced people living in camps in northeastern Syria, including many wives and children of jailed Islamic State fighters whom the SDF and U.S. see as potential recruits for the next generation of militants.68

So, on the manpower side—at least in Syria—there is a lot of latent potential, especially if counterterrorism pressure is lifted. These dynamics could also be heavily influenced by changes made to the U.S. mission in Syria, the plan to end the “U.S.-led coalition’s military mission in Iraq … by September 2025,”69 and the contours of the future bilateral U.S.-Iraqi defense relationship.

On the financial side, the Islamic State in its former core operating area in Iraq and Syria has not been able to regenerate, but it has been making do with far less resources than it had during its heyday.70 In August, the CTC published a broad assessment by Jessica Davis on the financial future of the Islamic State. It found:

The future of the Islamic State’s financial infrastructure is networked, resilient, and adaptive. The network has achieved this by focusing local groups on finance and governance and combining new and old methods of moving funds. The network also has redundancies: Revenue-sharing between groups and provinces allows the redistribution of funds to weaker groups or those that have suffered disruption, either because of between-group competition in their areas of operations or because of state or international CTF (countering the financing of terrorism) activities. As a result, countering the financing of the network will be an international coordination challenge, exacerbated by the great power division in some of the institutions for combating terrorism like the U.N. Security Council (and associated monitoring teams), and the expulsion of Russia from the Financial Action Task Force.

There are currently insufficient kinetic counterterrorism efforts being applied to disrupt the territorial control of Islamic State sub-groups. Without a sustained and effective kinetic counterterrorism approach, the group’s revenue-generating taxation and extortion activities will remain operational. Further, cash storage sites used by these groups will continue to amass funds, helping to sustain groups (and the broader network) over the long term. The current lack of investigative capacity to disrupt terrorist financing activities (through investigations and arrests) of terrorist financiers also remains a challenge for CTF and means that many Islamic State financiers and financial facilitators can operate with impunity. This is true for both the areas where Islamic State sub-groups operate directly, but also for their support areas outside direct conflict zones.

So, even if the Islamic State has not been able to regenerate its financial resources, it has adapted. It also appears to have ‘runway’ in various locales around the world to continue to acquire and pull resources into the movement without much resistance.

The Islamic State’s operational capacity varies across countries and regions. In Syria, the group has been making regenerative strides. In Iraq, in 2024 the group has conducted fewer attacks than in 2023, potentially a sign that it has less capacity.71 In Africa, the operational capacity of the Islamic State’s affiliates is generally trending up.

Assessment: The Islamic State’s core network in the Levant has not regenerated to levels observed during the 2014-2017 period—far from it—but the core network has been making regeneration strides. Other Islamic State affiliates have been helping the movement to adapt, bolster its resilience, and regenerate in a more collective way as a system.

The scores from the four VEO powers paint a not-so-great picture, as the Islamic State’s power is up or increasing in at least three of the four areas (power to attack and destabilize, inspire, and regenerate) from what it was years prior. The Islamic State’s ability to command and enable is split. Its power to command appears to be down, but it has made gains in its ability to enable since the loss of the movement’s physical caliphate.

The layered defense and degradation in depth framework also holds evaluative potential. For example, the June arrest of the eight Tajiks who gained entry to the United States and who were suspected of having ties to Islamic State members was touted by the Biden administration as a success because these individuals were identified, apprehended, and a potential plot was thwarted. The case is a good news story because nothing happened, and it was held out as a model to demonstrate how the “systems we have built and refined since 9/11 to keep the Homeland safe are working.”72 The efforts by U.S. government personnel to monitor and apprehend the eight individuals were a success, but there were also failings. When the ability of eight foreign nationals with suspected ties to a key terrorist group are evaluated in relation to the prevent entry action area included in the framework, it highlights how the system caught these individuals on the last line of defense—after they were already in the United States. So, while the detention of the eight suspects was a partial and important success, the case also illustrates how some of the United States’ defense mechanisms failed even while the overall layered system of defense succeeded. Identifying how and where defenses fall short is important so those deficiencies can either be addressed or approaches can evolve.

Conclusion

When it comes to counterterrorism, the United States has been living through an inflection point. It wants to focus less on terrorism, but key terrorist adversaries remain committed. The terrorism environment has also been evolving, and the United States and its partners need to contend with a terror landscape that is “more diverse, decentralized, and complex”73 than it used to be, which presents its own set of challenges. This includes threats posed by mainstay salafi-jihadi networks, such as the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida and their affiliated offshoots, but also inspired or loosely connected individuals, actors motivated by other ideologies and grievances, and the rise in state-sponsored or state-supported terror, as typified by the devasting attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and the rise of the Houthi threat. Changes in the environment share connective tissue with, and are being driven by, adaptations—and adaptive strategies—that have been embraced by terror networks. The Islamic State’s operationalization of its virtual enabling model is an important case in point.

Some of these adaptations have likely been initiated as a way to evolve around counterterrorism pressure. As a result, approaches to counterterrorism need to evolve along with them or adapt to better shape these adversarial changes in the first place. This article provided context and frameworks to help counterterrorism practitioners and strategists to understand and evaluate the power of VEOs and how CT pressure efforts or campaigns to degrade such entities could be approached and assessed from a strategic perspective. The Islamic State case study included at the end of this article highlighted how counterterrorism pressure has shaped the trajectory of that movement and made things much more difficult for its key node in the Levant. But that case study also drew attention to the limits of existing CT pressure approaches, the need for flexible and responsive approaches, and how additional thought and consideration should be given to the where, when, and how of CT pressure—so CT gains can be maintained, and so CT approaches can evolve to stay ahead of the threat. CTC

Don Rassler is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Director of Strategic Initiatives at the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy. His research interests are focused on how terrorist groups innovate and use technology; counterterrorism performance; and understanding the changing dynamics of militancy in Asia. X: @DonRassler

© 2024 Don Rassler

Substantive Notes

[a] These include: LOE 1 Strengthen Defenses, LOE 2 Build and Leverage Partner Capacity, LOE 3 Strengthen Our Capacity to Warn, LOE 4 Narrowly Focus Direct Action CT Operations, LOE 5 Deter and Disrupt State Sponsored Terrorism, LOE 6 Degrade Transnational Enablers of Terrorism, and LOE 7 Integrating CT with other U.S. foreign policy and national security efforts. For background, see Gia Kokotakis, “Biden Administration Declassifies Two Counterterrorism Memorandums,” Lawfare, July 5, 2023.

[b] The framework may not be as useful for state-sponsored/supported entities that engage in terrorism.

[c] These four VEO power elements are a modified and updated version of a prior framework the Combating Terrorism Center developed in 2009. The five power aspects that article highlighted included: the power to destroy, power to inspire, power to humiliate, power to command, and power to unify. For background, see “Five Aspects of Al-Qa`ida’s Power,” CTC Sentinel 2:1 (2009).

[d] In the early years after 9/11, the concepts of layered defense and defense in depth were used to help orient the United States’ approach to counterterrorism.

[e] There have been other approaches to scorecard the threats posed by al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State. One key example is the Critical Threat Project’s “State of al Qaeda and ISIS” annual series. For an example, see Katherine Zimmerman and Nathan Vincent, “The State of al Qaeda and ISIS in 2023,” Critical Threats Project, September 11, 2023.

[f] This is a departure from a little more than a year ago when the United Nations Monitoring Team assessed: “While the previously well-developed external operations capability of both the ISIL (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida core groups remains diminished and largely constrained.” See “Thirty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” United Nations, July 2023.

[g] The Iranian government has also blamed the group for an attack in 2023. See Maziar Motamedi, “Iran blames ISIL for shrine attack, arrests foreign nationals,” Al Jazeera, August 14, 2023.

[h] It is possible that the 2023 attack was also executed by ISK. See “Tajik National Behind Deadly Attack On Shah Cheragh Shrine In Iran, Regional Chief Justice Says,” RFE/RL, August 14, 2023.

[i] One example highlighted by the United Nations: “With Omar’s death and the relative silence from Abu Yasir Hassan (S/2023/549, para. 13), who has sought to disassociate ASWJ from ISIL following fundamental disagreements over reporting lines, finance, and leadership issues.” See “Thirty-third report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” United Nations, January 29, 2024.

[j] While the collection of documents reviewed by Hamming provided insights into the dynamics of center and periphery relationships during the 2015-2020 period, the author is not aware of similar documents covering the 2020-2024 period having been made public.

[k] One example is Islamic State-Somalia, as according to the International Crisis Group: “Sustained recruitment in Somalia has proven a challenge, due both to Al-Shabaab’s strength and IS-Somalia’s narrow clan base.” “The Islamic State in Somalia: Responding to an Evolving Threat,” International Crisis Group, Briefing 21 / Africa, September 12, 2024.

[l] The author would like to thank Petter Nesser, who kindly shared a copy of JPED dataset, and helpful information about its features and limitations. The version of the JPED shared includes case information up to early September 2024, and it is more up to date than the version and data that Petter Nesser and Wassim Nasr used for their June 2024 CTC Sentinel article. For background on JPED, see Petter Nesser, “Introducing the Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED),” Journal of Peace Research 61:2 (2023). See also Petter Nesser and Wassim Nasr.

[m] As explained by Nesser: “It classifies JPED’s plots into three categories based on documentation. For an incident to be included we need documentation that the perpetrator is jihadi. Secondly, we need documentation that an attack was launched, or in the making (e.g. bomb-making). Last, we need documentation about targeting. If all aspects are well documented, the case is category 1 (C1). If two aspects are well documented, it is category 2 (C2). If there are uncertainties regarding two or more aspects, the case is defined as category 3 (C3). The purpose is to avoid generalizing from dubious (C3) cases.” Nesser.

[n] The coding of plot connection type can be challenging. As noted by Nesser, “open sources seldom can specify connection type with a high degree of certainty. And it is very difficult to follow and update cases as investigations move along.” Author correspondence with Nesser, November 2024.

[o] The author would like to thank Aaron Zelin for this data input.

Citations

[1] Jim Garamone, “Defeat-ISIS Group Adapts to Continue Pressure on Islamic State,” DoD News, October 11, 2024.

[2] “Beware, global jihadists are back on the march,” Economist, April 29, 2024.

[3] Catherine Belton and Robyn Dixon, “Terrorist attack in Russia exposes vulnerabilities of Putin’s regime,” Washington Post, March 24, 2024.

[4] Adrian Blomfield, “The Return of al-Qaeda and Islamic State,” Telegraph, October 12, 2024.

[5] Aaron Zelin, “Islamic State on the March in Africa,” Washington Institute, March 1, 2024.

[6] Adam Goldman, Eric Schmitt, and Hamed Aleaziz, “The Southern Border, Terrorism Fears and the Arrests of 8 Tajik Men,” New York Times, June 25, 2024.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Graham Allison and Michael J. Morell, “The Terrorism Warning Lights Are Blinking Red Again,” Foreign Affairs, June 10, 2024.

[9] See “Chapter 8 – The System Was Blinking Red,” 9/11 Commission Report, July 22, 2004.

[10] Don Rassler, The Compound Era of U.S. Counterterrorism (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2023).

[11] Paul Pillar, “The Instruments of Counterterrorism,” U.S. Foreign Policy Agenda 6 (2001).

[12] Rassler.

[13] Pillar.

[14] For background, see “Counter-terrorism Strategy (CONTEST) 2023,” UK Home Office, July 18, 2023.

[15] “National Strategy for Counterterrorism of the United States of America,” The White House, October 2018.

[16] The literature of leadership decapitation suggests this is a key issue to consider. For background, see Bryan C. Price, “Targeting Top Terrorists: How Leadership Decapitation Contributes to Counterterrorism,” International Security (2012) and Jenna Jordan, “When Heads Roll: Assessing the Effectiveness of Leadership Decapitation,” Security Studies 4:18 (2009).

[17] Ellen Nakashima, “Israel, at behest of U.S., killed al-Qaeda’s deputy in a drive-by attack in Iran,” Washington Post, November 14, 2020. See also Assaf Moghadam, “Marriage of Convenience: The Evolution of Iran and al-Qa`ida’s Tactical Cooperation,” CTC Sentinel 10:4 (2017) and Cole Bunzel, “Why Are Al Qaeda Leaders in Iran?” Foreign Affairs, February 11, 2021.

[18] For background, see Andrew Zammit, “Operation Silves: Inside the 2017 Islamic State Sydney Plane Plot,” CTC Sentinel 13:4 (2020). See also Mette Mayli Albæk, Puk Damsgård, Mahmoud Shiekh Ibrahim, Troels Kingo, and Jens Vithner, “The Controller: How Basil Hassan Launched Islamic State Terror into the Skies,” CTC Sentinel 13:5 (2020).

[19] Zammit.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Albæk, Damsgård, Ibrahim, Kingo, and Vithner.

[22] Zammit.

[23] Ibid. Andrew Zammit’s article also provides insight into how the plot was disrupted.

[24] Haroro Ingram, “The Cascading Risks of a Resurgent Islamic State in the Philippines,” United States Institute of Peace, January 9, 2024.

[25] Ellen Mitchell, “US military carried out 95 counter-ISIS operations in last 60 days,” Hill, November 4, 2024.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Blomfield. For additional context on Iraq data, see Charles Lister, “CENTCOM says ISIS is reconstituting in Syria and Iraq, but the reality is even worse,” Middle East Institute, July 17, 2024.

[28] Ibid. See also Michael Phillips, “In Syria’s Hinterlands, the U.S. Wages a Hidden Campaign Against a Resurgent Islamic State,” Wall Street Journal, August 12, 2024.

[29] Lister.

[30] Blomfield.

[31] Blomfield. For full context of quote, see “Director General Ken McCallum gives latest threat update,” MI5, October 8, 2024.

[32] Data in Table 1 is from Aaron Zelin, “The Islamic State’s External Operations are More than Just ISKP,” Washington Institute, July 26, 2024. See also Amira Jadoon, Abdul Sayed, Lucas Webber, and Riccardo Valle, “From Tajikistan to Moscow and Iran: Mapping the Local and Transnational Threat of Islamic State Khorasan,” CTC Sentinel 17:5 (2024).

[33] Analysis of ACLED data for the period. See also Jadoon, Sayed, Webber, Valle.

[34] Zelin, “The Islamic State’s External Operations are More than Just ISKP.”

[35] For background on early attacks, see Aaron Zelin, “The Islamic State Attacks the Islamic Republic,” Washington Institute, October 31, 2022.

[36] See Aamer Madhani, “US warned Iran that ISIS-K was preparing attack ahead of deadly Kerman blasts, a US official says,” Associated Press, January 25, 2024, and Jadoon, Sayed, Webber, and Valle.

[37] Aaron Zelin, “A Globally Integrated Islamic State,” War on the Rocks, July 15, 2024.

[38] For background, see Petter Nesser and Wassim Nasr, “The Threat Matrix Facing the Paris Olympics,” CTC Sentinel 17:6 (2024); Javed Ali, “The Islamic State’s Afghanistan-based affiliate is emerging as a global menace,” Defense One, March 26, 2024; Zelin, “The Islamic State’s External Operations are More than Just ISKP;” and Jadoon, Sayed, Webber, and Valle.

[39] “NCTC Director Christine Abizaid, Statement for the Record, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs,” October 31, 2023. For background on recent ISK plots and attacks, see Nicolas Stockhammer and Colin P. Clarke, “Learning from Islamic State-Khorasan Province’s Recent Plots,” Lawfare, August 11, 2024. See also Aaron Zelin, “The latest ISKP arrest in Germany is now the 21st external operations plot/attack …,” X, March 19, 2024.

[40] “Beware, global jihadists are back on the march.”

[41] Zelin, “Islamic State on the March in Africa.”

[42] “Remarks by Acting Director of the National Counterterrorism Center at Cipher Brief Threat Conference,” Cipher Brief Threat Conference, October 6, 2024.

[43] For background on Islamic State Sahel, see Héni Nsaibia, “Newly restructured, the Islamic State in the Sahel aims for regional expansion,” ACLED, September 30, 2024.

[44] Ibid.

[45] “The Islamic State in Somalia: Responding to an Evolving Threat,” International Crisis Group, Briefing 21 / Africa, September 12, 2024.

[46] Caleb Weiss and Lucas Webber, “Islamic State-Somalia: A Growing Global Terror Concern,” CTC Sentinel 17:8 (2024).

[47] “Thirty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” United Nations, July 25, 2023.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Zelin, “A Globally Integrated Islamic State.”