Abstract: The coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic marks a unique event in human history—one that has captured the attention of the world, including supporters of violent extremist groups. This article examines unofficial pro-Islamic State media responses to the global pandemic during its early months and provides a content analysis of various themes and narratives. The authors collected and archived data from the online platforms Telegram, Twitter, and Rocket.Chat. In turn, 11 dominant themes and narratives were identified, highlighting the ways in which decentralized online pro-Islamic State networks create content designed to appeal to a diverse audience, capitalize on a current event, as well as provide a space for community engagement and camaraderie in a time of social isolation.

Although the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic brought much of the world to a stand-still, the internet has allowed people to remain virtually connected and updated on the latest COVID-19-related news, including violent extremist groups and terrorist organizations. In the case of the Islamic State, unofficial media networks, consisting of decentralized Islamic State supporters online, have produced a wide range of responses to the pandemic. Documenting these narratives offers insights into how a decentralized media ecosystem allows space for supporters to converge and diverge from the viewpoints presented in official propaganda, tailor messages for a global audience, boost morale among supporters, and utilize the momentum of a catastrophic event to expand upon carefully shaped narratives previously developed by the terrorist organization.

The authors’ dataset identified 11 themes and narratives in online Islamic State supporter content, which provides a framework for closer analysis on how Islamic State supporters are reacting to COVID-19. The authors argue that Islamic State supporters are essential elements in the Islamic State’s messaging, helping shape narratives and ideals among the broader Islamic State community. During a global pandemic, this serves a number of purposes, such as developing a stronger sense of community; maintaining and shaping in-groups, out-groups, and notions of the “other;” supporting and advising; and offering opportunities to express anger, fear, and antipathy in an uncertain world. This article provides a detailed explanation of the themes and narratives found in the dataset, offering a comprehensive overview of pro-Islamic State unofficial media responses to the coronavirus. Although a number of official Islamic State media products—including issues of its Al Naba newsletter and an audio message from May 28, 2020, by the Islamic State’s official spokesman, Abu Hamza al-Qurashi1—make references to the virus, understanding what the Islamic State’s central media is saying about COVID-19 is important; knowing what the group’s wider community is saying may be even more so.

Methodology

Between January 20, 2020, and April 11, 2020, 442 items of online Islamic State supporter content were collected on three social networking and messaging platforms: Twitter, Telegram, and Rocket.Chat.a All 442 items of Islamic State supporter content are archived from online platforms that were selected due to a significant and stable pro-Islamic State presence, along with the authors’ ability to access channels, groups, and chats on these platforms. Content was gathered from public and private channels, chats, and groups on Telegram and Rocket.Chat as well as from Twitter accounts identified as pro-Islamic State from their tweet history. It is important to note that due to privacy restrictions, any content related to the coronavirus in Direct Messages (DMs) on Twitter and Rocket.Chat, along with individual one-on-one chats and Secret Chats on Telegram, were inaccessible to the authors.

The authors analyzed the data for dominant themes and narratives in the content. This process was done through qualitative analysis and basic intercoder reliability looking for manifest and latent qualities in the content.b Upon completion, data was quantitatively analyzed while bearing in mind the dominant themes and narratives derived from the qualitative breakdown.

It should be emphasized that although the dataset is extensive, it does not capture the full population of Islamic State supporter content related to the coronavirus. Nevertheless, the authors can assume that it provides a large enough sample to therefore extrapolate dominant themes and narratives surrounding the virus. Furthermore, this study is limited to the access that both authors have to online platforms used by the Islamic State and its supporters. This includes pro-Islamic State groups and channels on these platforms. Online pro-Islamic State groups, channels, and user accounts are regularly shut down and removed due to platform terms of service, content regulations, and policies on terrorism and extremism.c Accordingly, not every researcher or analyst conducting similar work will have the same experiences or access to identical pro-Islamic State platforms, groups, and channels; thus, replication of this study may produce different results.

Eleven themes and narratives were identified. A 12th category of “other” was noted since this content contained wide-ranging themes and narratives that did not fall into one of the 11 categories. Themes and narratives include:

Counting: content listing the numbers of confirmed cases and deaths in African, Asian, European, South American, and North American countries. This also includes user-created graphs, announcements of prominent individuals becoming ill (for example, the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Prince Charles), and citing the number of infected individuals on U.S. naval ships.

Conspiracies: content about the virus being created or spread by unbelievers, the West, or a Zionist plot and the notion that the virus was created in a lab. Some of these postings contain musings mirroring anti-vaccination conspiracy theories.

Defeating Boredom: content that offers ways of defeating boredom during social isolation. The majority of this content suggests performing religious practices.

Divine Punishment: content that specifically refers to the coronavirus being an act of God, a punishment from God, or a “Soldier of Allah.” Notions of divine punishment are also attached to nations, with examples including China, the United States, and Israel as well as geographical regions such as the West. Additionally, issues like the Chinese government’s oppression of the Uighurs; matters surrounding the group being pushed out of its last territorial holding in Baghouz, Syria; prisons holding Islamic State detainees; and detention camps housing women and children associated with the Islamic State are similarly connected with notions of divine punishment.

Humor: content contains a number of items that sarcastically mock individuals, groups, and religions denounced by the Islamic State and its supporters as nonbelievers (kuffar), rejectors (rafidah), and apostates (murtadeen).

Naming Groups: content that indicates online channels and chats with coronavirus-themed names.

Practical Responses: content offers advice on coronavirus symptoms and detection, along with discussions on wearing face masks. This content reflects similar advice found in the Islamic State’s Al Naba issue 225, which provides “sharia directives” of covering one’s mouth when sneezing or yawning, as well as avoiding “lands of the epidemic,” while those infected should not “leave from it.”2

Religious Support and Resources: content includes imploring God to protect Muslims, anasheed (vocal a cappella music), memes with scripture, Islamic remedies for the virus, discussions on mosques being closed, praying at home, reminders of faith, and discussions on divine plagues. It is important to note that the framing of this category is not meant to infer that religion does not have bearing on other themes and narratives in the dataset, including the divine punishment and vindictive categories.

Islamic State Coronavirus News: content that denotes the sharing of Islamic State news on the coronavirus.

Socioeconomic Decay: content includes discussions on what life will look like after the pandemic: social unrest, economic devastation, and the collapse of society.

Vindictive: these narratives compromise rejoicing at perceived enemies becoming ill, wishing affliction as “payback”3 for crimes against the Muslim community (ummah), and jubilation at death tolls and reports of mass graves in Western nations and China.

It is important to note that when considering Islamic State supporter content in the dataset, originally, some items are unassociated with the Islamic State but come from the wider jihadi community. Additionally, some of this content is also used by Islamic State supporters from ‘Islamic’-themed posts online, including content featuring generic religious advice related to the virus. These items are then reused or repurposed by Islamic State supporters, circulated in their online communities, and employed for their own agendas.

The Data

As the coronavirus became a prominent topic in international news and daily discussions, the authors began noticing virus related content posted in pro-Islamic State channels, groups, and chats on Twitter, Telegram, and Rocket.Chat. Considering the timely nature of these posts and the coronavirus pandemic being a unique time in history, the authors began archiving Islamic State supporter content related to the pandemic. From January 20, 2020, to April 11, 2020, the authors gathered 442 items of online community content related to the coronavirus and associated with Islamic State supporters. Content includes 442 unique posts with text, images, video clips, memes, text with links to news stories or online groups to join, graphs, infographics, PDFs, and anasheed.

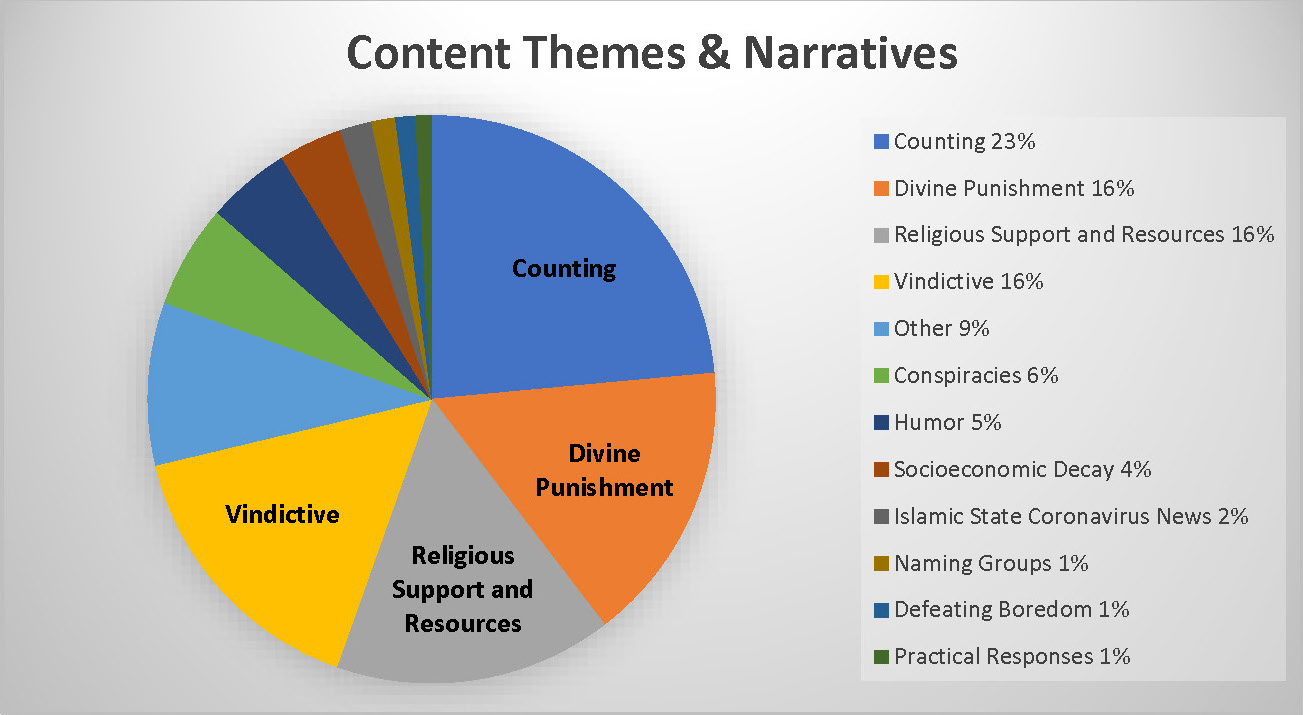

Content analysis revealed 11 themes and narratives, along with a 12th category of “other.” Figure 1 displays the breakdown of content for dominant coronavirus themes and narratives.

“Counting” made up the most content in the dataset at 23% (or 104 items). “Divine Punishment,” “Religious Support and Resources,” and “Vindictive” content followed at 16% each, with “Divine Punishment” consisting of 71 items of content and “Religious Support and Resources” and “Vindictive” with 70 items each. “Other” ranked third at 9% or 41 items. Languages used in the content—listed in order of frequency—are English, Arabic, content mixing English and Arabic, French, Indonesian, and Dhivehi (an Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the Maldives).

Dominant Theme and Narratives

Scholar Daniel J. O’Keefe4 argues that messages with narratives are more persuasive than messages that lack narratives, while scholars Alister Miskimmon, Ben O’Loughlin, and Laura Roselle5 contend that strategic narratives are an approach used by political actors to form shared meaning and influence the actions of domestic and international actors. Themes provide narrative with resonance, while also offering connotations that communicate details to an audience beyond those in the direct message.6 In the case of this study, 11 themes and narratives are found in the content analyzed, providing insight into how a decentralized, but centrally guided media ecosystem shapes coronavirus messaging among Islamic State supporters online.

Counting was the largest subset of data,d consisting of supporters sharing news updates on the number of coronavirus deaths by country, those infected with the disease, and prominent individuals being diagnosed. The countries mentioned in these various posts included Western nations, China, South Korea, Afghanistan, India, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Algeria, Iraq, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Turkey.

One Rocket.Chat post7 includes a graphic of the total number of cases by country where the United States was listed as the leading country in worldwide coronavirus cases. Accompanying this graphic is sarcastic commentary stating, “USA is the World Leader! Make America ‘great’ again, insha’Allah (God willing).” Aside from various countries’ coronavirus statistics, content also highlights city and region-specific information, particularly in relation to cities and states within the United States. An outlier within the counting category includes a comment on the coronavirus being present in Roj Camp.8 e

Sharing statistics on coronavirus numbers does not require much effort or creativity on the part of those posting it. Additionally, the readily available nature of constantly changing information contributes to an environment where supporters are able to provide real-time updates. When considering the numbers posted by Islamic State supporters on coronavirus deaths and infections, some of the statistics cite major news sources, while other posts lack references, therefore the accuracy of the numbers in the counting category are disparate. Although a number of posts consist of tables displaying coronavirus statistics without commentary, the authors documented several supporters responding with comments such as “Allahu akhbar (God is great)” and “Alhamdulillah (praise be to God) this makes me happy!”9 when seeing daily increases in reported infections and fatalities. Hypothetically, these counting posts provide an opportunity for supporters to develop a stronger sense of community and bonding by expressing shared feelings of delight over the plight of their perceived enemies.10

A number of conspiracy themes surrounding the coronavirus are present in the data. These include the virus being created or spread by unbelievers, the West, or a Zionist plot; that the virus was created in a lab; and anti-vaccination conspiracies.f A post on Rocket.Chat11 from March 24, 2020, proposes a conspiracy theory that “Murtadeen (apostates) and Kuffar (nonbeliever) journalists and so called [sic] analysts” are purposely spreading the virus among the ranks of the “Mujahideen” and Islamic State “brothers” and “sisters” held in camps and prisons. A different user responded by suggesting that the “kuffar (nonbelievers) have already been purposefully leaving Muslims in disgusting conditions and abusing them,” making them more susceptible to disease.12 Additionally, a lengthy post with an anti-vaccination narrative was posted on Telegram by “Glad Tidings to The Strangers,”13 on March 26, 2020. The post argues against vaccinations in general, claiming that “the doctor who injects with these vaccines does not even know what they are putting in the person they are injecting … These kuffar (nonbelievers) don’t [sic] care about anyone.” In their insight on conspiracies surrounding the coronavirus, scholars Marc-André Argentino and Amarnath Amarasingam have noted the harm done by anti-vaccination narratives in relation to trust in science.14 During a global pandemic, such narratives are highly problematic when trying to control and eradicate a contagious virus.

Although posts about defeating boredom were not numerous, a small amount of content emphasized spiritual growth as a way to pass the time during quarantine. A channel on Telegram shared a message urging “brothers and sisters to make use of this time to gain closeness to the Rabbul’Alaalameen (Lord of the Universe)” and posted a check list of “Things you can do in Quarantine In Order to Use Your Time Wisely Fi Allah (for God).” The list encouraged activities such as reading the Qur’an daily, learning Arabic, dhikr (ritual prayer), and making dua (invocation).15

Seventy-one items of content with the divine punishment theme appear in the dataset. A large number of posts relate to what the Islamic State and its supporters perceive as the enemy, encompassing nonbelievers (kuffar), rejectors (rafidah), and apostates (murtadeen), including Shi`a, Shi`a militias, Iranians, and the Iranian government. Numerous posts also framed the virus as God’s divine punishment on enemy nations and China for its oppression of Muslims and, more specifically, Uighurs. Although the plight of Uighurs has occasionally been mentioned in official propaganda and by Islamic State supporters, COVID-19 has amplified narratives on the Chinese government’s oppression of the Uighurs, bringing this issue to the forefront. The scholar Aymenn Al-Tamimi has pointed out conflicting narratives surrounding China and the coronavirus in official Islamic State propaganda, noting that the Islamic State’s Al Naba 220 newsletter cautions supporters against judging the virus as a punishment on China by God, and that the newsletter also expresses delight over the spread of the virus in the country.16 Issue 226 of Al Naba further details the pandemic as an illustration of God’s punishment on nations, while mentioning the potential economic, security, and social costs of the virus on enemy states.17 Furthermore, the editorial highlights “crusader” countries being preoccupied by the virus, while suggesting that the pandemic provides an opportunity to strike Western nations, similar to attacks by the Islamic State in London, Paris, Brussels, and other locations.18

The Battle of Baghouz is an additional topic commonly referenced in the divine punishment content found in the dataset. Although the defeat in Baghouz marked the end of the Islamic State’s territorial claims, supporters revisited this event by incorporating a coronavirus-centered narrative, suggesting that the virus is God’s vengeance on those involved in the group’s removal from its last pocket of territory. In a similar vein, one comment mentioned Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s death in October 2019, speculating that “when the blood of the caliph gets shed disaster will hit earth.”19

When considering the Islamic State’s official spokesman Abu Hamza al-Qurashi’s May 28, 2020, audio statement titled “And the Disbelievers Will Know to Whom the Final Abode/Home Belongs” (a quote from Qur’anic verse 13:42), parts of the speech make reference to the coronavirus being a punishment of God on the “crusaders,” nonbelievers, and the Tawagheet (an idol, tyrant, oppressor) who fought against Muslims, God’s religion, and the Islamic State.20 The speech also states that, due to the virus, the “crusaders” are now suffering under conditions that Islamic State fighters experienced at the hands of their enemies, such as having their bodies “thrown in the streets” and living under imposed curfews.21 Comparable notions are found in Islamic State supporter content within the dataset, particularly in the Divine Punishment and Vindictive categories. This points to Islamic State supporter content reflecting overall themes promoted by the group’s spokesman and central media, while also focusing on topics not touched upon in official propaganda.

Humor comprises 5% of content in the data. This category included jokes about toilet paper shortages, sarcastic comments about the coronavirus spreading in Iran, and anti-Chinese sentiments. Some content also included generic humor about the virus unrelated to pro-Islamic State opinions. For example, one post by an Islamic State supporter on Twitter22 used the hashtag “#CoronaJihad,” joking that Vladimir Putin will contract the virus. Although Hindu nationalists in India have extensively used “#CoronaJihad” to promote anti-Muslim sentiments,23 this supporter’s tweet uses the hashtag to imply a different meaning: the virus is fighting against a leader of the “kuffar.”

Many people turn to humor during times of crisis as a coping mechanism.24 The Islamic State supporter content reflects this with supporters posting content that mocks their perceived enemies while framing their adversaries as being absurd. Much of the content is lighthearted yet with underlying prejudice.

During data collection, the authors identified six newly established pro-Islamic State groups and channels with coronavirus or pandemic names and themes, in both English and Arabic. Examples include the now defunct Telegram channels “The Pandemic,” “korounna,” and “COVID-19,” among others. Naming groups could be undertaken for various reasons to include: supporters exploiting a timely subject, supporters creating groups and channels dedicated to coronavirus news and discussion, or supporters evading pro-Islamic State group and channel shutdowns through the use of non-Islamic State-themed names.25 When considering the content within these groups and channels, the most plausible reasons are utilizing the newsworthy and global nature of the virus, along with a desire to discuss COVID-19 in environments of shared belief.

Although the religious support and resources category represents 16% (or 70 items) of content in the dataset, it consists mainly of narratives offering prayers of protection to the ummah (the greater Muslim community), content referring to plagues mentioned in religious scripture,g discussions on prayer due to mosques closures, and content on faith. Some of the more interesting content suggest ‘Islamic’ remedies for the virus, including a Twitter post on February 28, 2020, that suggests “A cure for every disease,” stating a hadith from “Al-Bukhari and Muslim,” noting the use of “Black Seed regularly, because it is a cure for every disease, except death.”26

The majority of religious content in the dataset offers advice, along with comfort to the Islamic State community online. While the majority of online content in the dataset is interactive—with users being able to comment and share posts—the religious content provides users with a means of expressing their thoughts and prayers with other like-minded individuals. Moreover, the content offers insight into a softer side of pro-Islamic State messaging, displaying a more human element of the Islamic State community online than is regularly discussed.

Islamic State coronavirus news is not a dominant theme in the dataset; however, it is important to note from a communications perspective. The data reflects that content with articles and screenshots from mainstream media reports discussing the Islamic State’s response to the coronavirus was shared among pro-Islamic State community members. A Rocket.Chat post from April 9, 2020, includes a tweet that provided a link to an article called “How the Islamic State Feeds on Coronavirus.”27 Several other Telegram posts feature news articles that directly display images of a coronavirus infographic from the Islamic State’s Al Naba 225 newsletter titled “Sharia Directives to Deal with Epidemics.” Along with the infographic, these posts included supporter commentary pointing out how mainstream media outlets help spread Islamic State propaganda to a wider public audience. Scholar Brigitte L. Nacos28 has noted the relationship between mainstream media and terrorists’ content, recognizing how the media may unintentionally spread Islamic State propaganda to a wider audience (if precautions are not taken) by highlighting alarming or violent terrorist attacks, videos, and other content.29 That being said, it is important to note that many news organizations and journalists remain cognizant of this potential issue and take precautions when covering terrorism or referencing terrorist propaganda.

Posts falling under the socioeconomic decay category cited economic collapse and societal decline as being the primary threat, not coronavirus itself. Several posts provided predictions that war would eventually erupt, and one commentary from a Telegram post on March 15, 2020, drew attention to the rise in U.S. gun sales with the added hope that it is a sign that “allies will turn against each other and the believers will take full advantage of it.”30 Interestingly, one Twitter user seemed to express apprehension at mass civil unrest and advised others to prepare for the chaos.31

Seventy items of vindictive content are found in the dataset. Much of the content consists of posts celebrating perceived enemies becoming sick and narratives reflecting the virus as vengeful payback for crimes against the ummah. A post on Rocket.Chat32 from March 19, 2020, states “there is no need to argue with the kuffar (nonbelievers) about the #coronavirus. just [sic] sit back an [sic] enjoy their pain and agony. and [sic] yes we are baqiyah (enduring/everlasting) by permission of allah [sic].”

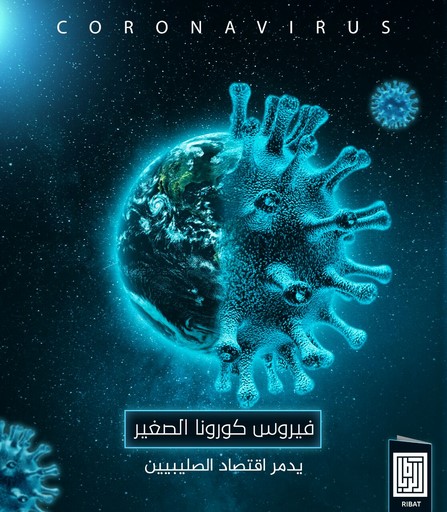

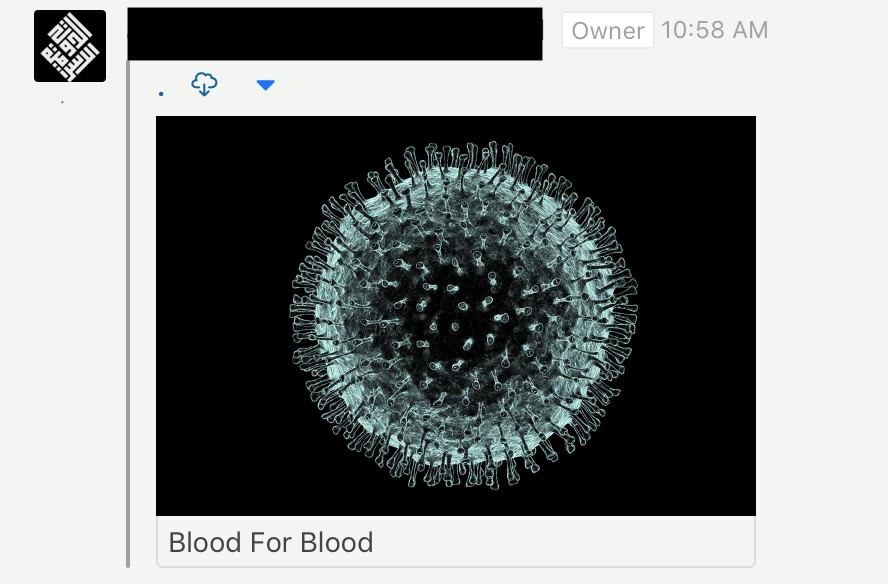

As Figures 2 and 3 display, a number of images are also found in the vindictive category depicting virus cells alongside malicious narratives. The scholar Paul Messaris explains that images associated with narratives may have a more persuasive effect on their consumers.33 Furthermore, media strategists suggest that posts with images are more appealing to audiences and receive greater engagement.34 This points to Islamic State supporters using known marketing tactics to promote and persuade fellow supporters online.35 In the case of the vindictive content, the images used support the narratives associated with this category.

A few posts in the vindictive content category were aimed at well-known researchers in the terrorism studies field discussing issues surrounding the coronavirus on Twitter. Posts from Islamic State supporters include links to or screenshots of these Twitter posts followed by malicious comments directed at the researchers. This demonstrates that just as the authors follow the Islamic State and its supporters online, they similarly keep track of researchers in the field.

It is noteworthy that during the time of data collection, the authors found only one piece of supporter content related to biological terrorism. This item was placed in the “other” category and is a discussion about using an infected Islamic State supporter to spread the virus to the unbelievers (kuffar): A member in a private Telegram group mentions that “one of our brothers” was infected by coronavirus and in reply, another supporter responds “May Allah preserve his health. He should try to go infect others.”36 Despite there being one post in the dataset on this subject, it is worth mentioning since it promotes using the virus as a weapon.

As researcher Jessica M. Davis suggests, several factors may account for the lack of Islamic State supporters’ posts promoting the coronavirus as a biological weapon.37 The highly contagious nature of the virus means it would be difficult to measure the number of people who contracted COVID-19 as the direct result of a biological terrorist attack. Tracking the number of fatalities would be difficult even if an infected Islamic State supporter were able to spread the disease. Depending on the objectives, these often-ambiguous dynamics may take away from any “immediate ‘glory’”38 and accompanying ‘flashy’ terrorist attack footage that the Islamic State could use in its official media.

Although the dataset only indicates one discussion related to biological terrorism,h it is worth mentioning that a Tunisian arrest report39 from April 16, 2020, notes that a jihadi recently released from prison was encouraging jihadis with coronavirus symptoms to cough, sneeze, or spit when in the presences of security officials as a means of spreading the virus. Moreover, in late May 2020, the sixth edition of a pro-Islamic State propaganda magazine targeting India—called the Voice of Hind (India) and thought to be associated with the group Junudul Khilafaah Al Hind40— encourages Muslims to become infected with the virus in order to spread it to security forces and disbelievers.41 i This indicates that while it is not a common narrative in this dataset, use of COVID-19 as a biological weapon has gained at least some traction in jihadi circles.

Conclusion

The coronavirus data underpinning this article serves as a case study on the ways in which Islamic State supporters online construct various narratives through unofficial propaganda and individual commentary. As scholars Rosemary Pennington and Michael Krona state, “ISIS’s power also lies in the stories it tells of itself”42—stories that maintain an inherent flexibility that allow supporters to continue building on top of older narratives in order to maintain relevancy. These narratives may also veer from the official status quo and conflict with the beliefs of fellow comrades who develop their own individual understandings of the world, how it relates to them personally, and how they conceptualize it as Islamic State supporters.

A stark contrast between Islamic State supporter content and official Islamic State propaganda can be seen in the Counting category, which constitutes the largest subset in the data. Whereas some supporters regularly posted updates on the number of coronavirus deaths and infections across countries, this has not been seen in official Islamic State media products. Another area of differing views can be found in the Conspiracies category where some Islamic State supporters promoted conspiratorial theories regarding the coronavirus. Supporters who claim the virus was created in a lab or as part of a Zionist plot contradict and stray away from official Islamic State media narratives, which promote the virus as a form of divine punishment on the kuffar and the will of God. Then again, other Islamic State supporters celebrated the virus as a “soldier of Allah,”43 falling in line with official Islamic State narratives of the virus being a punishment from God.

Although there are divergent ideas between the themes and narratives found in Islamic State supporter content and official Islamic State propaganda, the coronavirus provides the Islamic State and its community with a topic that unites supporters and offers opportunities to promote religious messages that serve in unifying its base. The supporter content goes a step further due to its interactive nature, serving as a mechanism to discuss COVID-19-related issues in various ways ranging from helpful to extreme to humorous. It also offers supporters a means of expression and kinship in an uncertain world that is socially isolated.

Themes and narratives in extremists’ communications are important, whether in products produced by official media wings or those expressed by community members. Furthermore, identifying possible points of contention within an online ecosystem like that of the Islamic State may present an opportunity for counterterrorism-focused strategies to capitalize on discrepancies found in community content and official products. CTC

Chelsea Daymon is a researcher pursuing a Ph.D. in Justice, Law & Criminology in the School of Public Affairs at American University. She is also an associate fellow at the Global Network on Extremism & Technology. Follow @cldaymon

Meili Criezis is a program associate with the Polarization and Extremism Research and Intervention Lab (PERIL) at American University. Her research focuses on terrorist propaganda, domestic/international violent extremism across ideologies, and extremist networks in online spaces. Follow @malikacoexist54

Substantive Notes

[a] The authors monitored the online platforms Twitter, Telegram, and Rocket.Chat* between the dates of January 20, 2020, and April 11, 2020, for Islamic State supporter content related to the coronavirus. For Telegram and Rocket.Chat, the authors collected everything they could find related to the coronavirus. For Twitter, content was collected from accounts identified as pro-Islamic State based on their tweet history. Since Twitter is less centralized compared to Telegram and Rocket.Chat, which have dedicated pro-Islamic State channels and groups, there could be a selection bias in the Twitter content archived for this study. The decentralized nature of Islamic State supporters on Twitter proved challenging. Although, the authors attempted to collect all Islamic State supporter content related to the coronavirus on Telegram, Rocket.Chat, and Twitter during the collection period, account shutdowns and the banning of user profiles, at times, made the task difficult. Despite these challenges, the authors assume that the dataset provides a large enough sample to infer dominant themes and narratives surrounding the coronavirus. When considering content found on the platforms, Telegram was the platform with the highest amount of content at 39% or 172 items of content, Twitter ranked second at 38% or 168 items, while Rocket.Chat came in third at 23% or 102 items.

* Rocket.Chat is an open-source platform that allows users to create team chats either on the cloud or through their own servers. It can be used on mobile devices or through a desktop application. Rocket.Chat provides users with file-sharing capabilities, audio, video, LiveChat, and end-to-end encryption (E2E). Users can also customize their experiences on the platform through additional options, plugins, and themes. Similar to al-Qa`ida, the Islamic State has set up its own Rocket.Chat server where propaganda is disseminated, and users chat amongst themselves.

[b] Basic intercoder reliability consisted of the authors separately and independently going through the data and placing content into categories they deemed appropriate based on manifest and latent qualities. There was 95% agreement when reviewing the initial placement of content into categories, while any remaining discrepancies were reconciled through a second review of the content based on the themes and narratives found within. Manifest qualities refer to themes and narratives that are physically present in the content, while latent qualities refer to underlying meanings which require interpretation. Although some products could potentially be grouped into one category under a religious umbrella, the authors were careful to analyze both the manifest and latent qualities of each post, noting slight differences in semantics, attributions, and meanings. Thus, the Religious Support and Resources category focuses on religious advice, scriptures, and prayers for the ummah, while the Divine Punishment and Vindictive categories differ in that Divine Punishment is an act of God, while Vindictive content focuses on malicious retribution while God is not mentioned. Accordingly, each item of content was place in an exclusive category based on the overall dominant theme or narrative present. For example, a Rocket.Chat post from March 20, 2020, referring to North America, Europe, and the coronavirus states “they getting [sic] payback for their crimes inash’Allah (God willing). now [sic] they experience some of pain [sic] experienced by the Ummmah [sic].” Due to the overall vindictive quality of the post, this post was placed in the Vindictive category. On the other hand, a post on Twitter from March 3, 2020, states “O Allah how perfect are You. Coronavirus is the perfect punishment to bring Your disbelieving arrogants [sic] down to their knees and humility to the believing slaves.” Owing to the overriding narrative that the coronavirus is a punishment from God, this post was placed in the Divine Punishment category. Based on this careful system of analysis, each item of content was place in one category with no items in the dataset appearing in more than one category.

[c] It is worth noting that Telegram and Europol have conducted a number of joint Referral Action Days where, through coordinated efforts, many pro-Islamic State channels and groups on Telegram have been disrupted and removed. Despite these actions, a continued Islamic State presence remains on Telegram. See “Referral Action Day with Six EU Member States and Telegram,” Europol, October 5, 2018; “Europol and Telegram Take on Terrorists Propaganda Online,” Europol, November 25, 2019; and Amarnath Amarasingam, “A View from the CT Foxhole: An Interview with an Official at Europol’s EU Internet Referral Unit,” CTC Sentinel 13:3 (2020): pp. 15-19.

[d] The authors listed “divine punishment” and “religious support and resources” as two separate categories but if they had been grouped under the same category, this would constitute the largest meta category of data.

[e] Roj Camp is a refugee/internally displaced person (IDP) camp located in northeast Syria and under the control of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-led militia. It houses a number of women and children associated with the Islamic State, making it, along with other camps holding women and children linked to the group, a topic of interest for Islamic State supporters.

[f] Anti-vaccination conspiracies spread false information about the dangers and/or the effectiveness of vaccines. Common conspiracies include assertions that vaccinations cause autism, are a part of a government attempt to monitor or infect people, and are simply a way for companies to profit financially at the expense of human lives.

[g] In the Religious Support and Resources category, references to plagues originate from religious scripture and offer religious advice for dealing with plagues. Any references to plagues as punishment on non-believers and/or enemies were placed in the Divine Punishment category only if posts referred to the virus being a punishment by God. On the other hand, as mentioned earlier, posts wishing the virus as retribution on various actors yet without mentioning God as the punisher were placed in the Vindictive category.

[h] It is worth noting that discussions on biological terrorism could be taking place in Direct Messages (DMs) on Twitter and Rocket.Chat, or in individual one-on-one chats and Secret Chats on Telegram, which were inaccessible to the authors.

[i] This special “lockdown” edition of Voice of Hind features articles related to the coronavirus with discussions ranging from the suffering of Muslims in India to taking advantage of Western nations that are preoccupied with the virus. “The Voice of Hind,” issue 6, May 29, 2020.

Citations

[1] “And the Disbelievers Will Know Who Gets the Good End,” translation of Abu Hamza al-Qurashi’s speech, March 28, 2020.

[2] Al Naba issue 225, March 12, 2020, p. 12.

[3] Rocket.Chat post, March 20, 2020.

[4] Daniel J. O’Keefe, Persuasion: Theory and Research (3rd Edition) (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2016).

[5] Alister Miskimmon, Ben O’Loughlin, and Laura Roselle, Strategic Narratives: Communication Power and the New World Order (New York: Routledge, 2013).

[6] Charlie Hargood, “Exploring the Importance of Themes in Narrative Systems,” University of Southampton, School of Electronics and Computer Science, Ph.D. thesis (2009): pp. 1-42.

[7] Rocket.Chat post, April 2, 2020.

[8] Telegram post, March 11, 2020.

[9] Telegram post, March 24, 2020.

[10] Jennifer Preece, Online Communities: Designing Usability, Supporting Sociability (Chichester, England: Wiley, 2000).

[11] Rocket.Chat post, March 24, 2020.

[12] Rocket.Chat post, March 24, 2020.

[13] Telegram post, March 26, 2020.

[15] Telegram posts, March 22, 2020.

[17] Al Naba issue 226, p. 3. March 19, 2020.

[18] Ibid., p 3.

[19] Twitter post, February 29, 2020.

[20] See “And the Disbelievers Will Know Who Gets the Good End,” translation of Abu Hamza al-Qurashi’s speech, March 28, 2020, p. 2, and Aymann Jawad Al Tamimi, “New Speech by the Islamic State’s Official Spokesman: Translation and Analysis,” Aymann Al Tamimi blog, June 1, 2020.

[21] “And the Disbelievers Will Know Who Gets the Good End,” p. 2.

[22] Twitter post, March 31, 2020.

[26] Twitter post, February 28, 2020.

[27] Rocket.Chat post, April 9, 2020.

[28] Brigitte L. Nacos, Mass-Mediated Terrorism: Mainstream and Digital Media in Terrorism and Counterterrorism (3rd Edition) (Plymouth, U.K.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Telegram post, March 17, 2020.

[31] Twitter post, January 25, 2020.

[32] Rocket.Chat post, March 19, 2020.

[33] Paul Messaris, Visual Persuasion: The Role of Images in Advertising (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1997): p. xv.

[34] See Michael Patterson, “How to Double Your Social Engagement with Images,” Convince & Convert, n.d.

[35] Michael Krona and Rosemary Pennington, The Media World of ISIS (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2019): p. 145.

[36] Telegram post, April 2, 2020.

[38] Ibid.

[39] See “[Arresting a Takfiri Element Inciting the Spread of Coronavirus Among Security Officials],” Tunisian Republic Ministry of Interior, April 16, 2020.

[40] Kabir Taneja, “Islamic State Propaganda in India,” Observer Research Foundation, April 16, 2020.

[41] Voice of Hind, Lockdown Special issue 6, p. 7. May 2020.

[42] Krona and Pennington, p. 267.

[43] Telegram post, March 18, 2020; Twitter post, March 18, 2020; Telegram post, March 19, 2020.

Skip to content

Skip to content