Abstract: The multiplication and diffusion of jihadi networks within Nigeria is an important component of the broader spread of jihadi violence from the Sahel into coastal West Africa, a trend that has caused significant international concern. Yet, an understanding of the factors that facilitate or impede jihadi expansion in Nigeria, and Africa more broadly, remains limited and often unnuanced. Drawing on extensive fieldwork and interviews with non-state actors, the authors analyze how different jihadi groups, including various factions of Nigeria’s “Boko Haram” insurgency as well as so-called “Lakurawa” militants from neighboring Niger, have each attempted to expand into northwestern, central, and southern Nigeria over the past five years. In detailing these efforts, some failed and others successful, two key trends are identified. First, jihadis tend to expand into regions that are impacted by banditry (which is rampant in rural Nigeria) yet simultaneously not dominated by any overly powerful bandit leaders. The authors dub this the “Goldilocks effect” to reflect how jihadis seek areas with an ‘optimal’ level of banditry so that they can reap certain benefits from bandits without risking confrontation with powerful warlords. Second, jihadis try to expand in areas where the commanders have existing social or religious ties, and these ties are typically more important for gaining new recruits than appeals to factional affiliation per se. The authors demonstrate this through a case study of Kogi state in central Nigeria, where both Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Ansaru (an al-Qa`ida-aligned faction) have recruited from the same local religious networks.

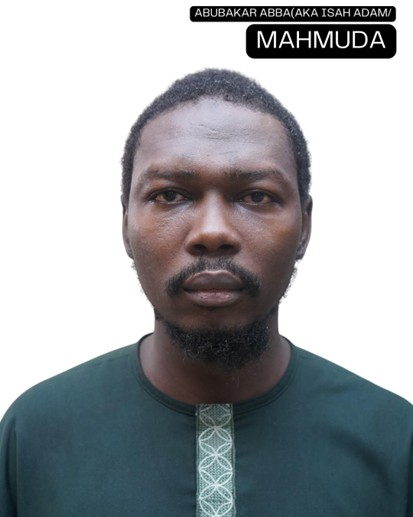

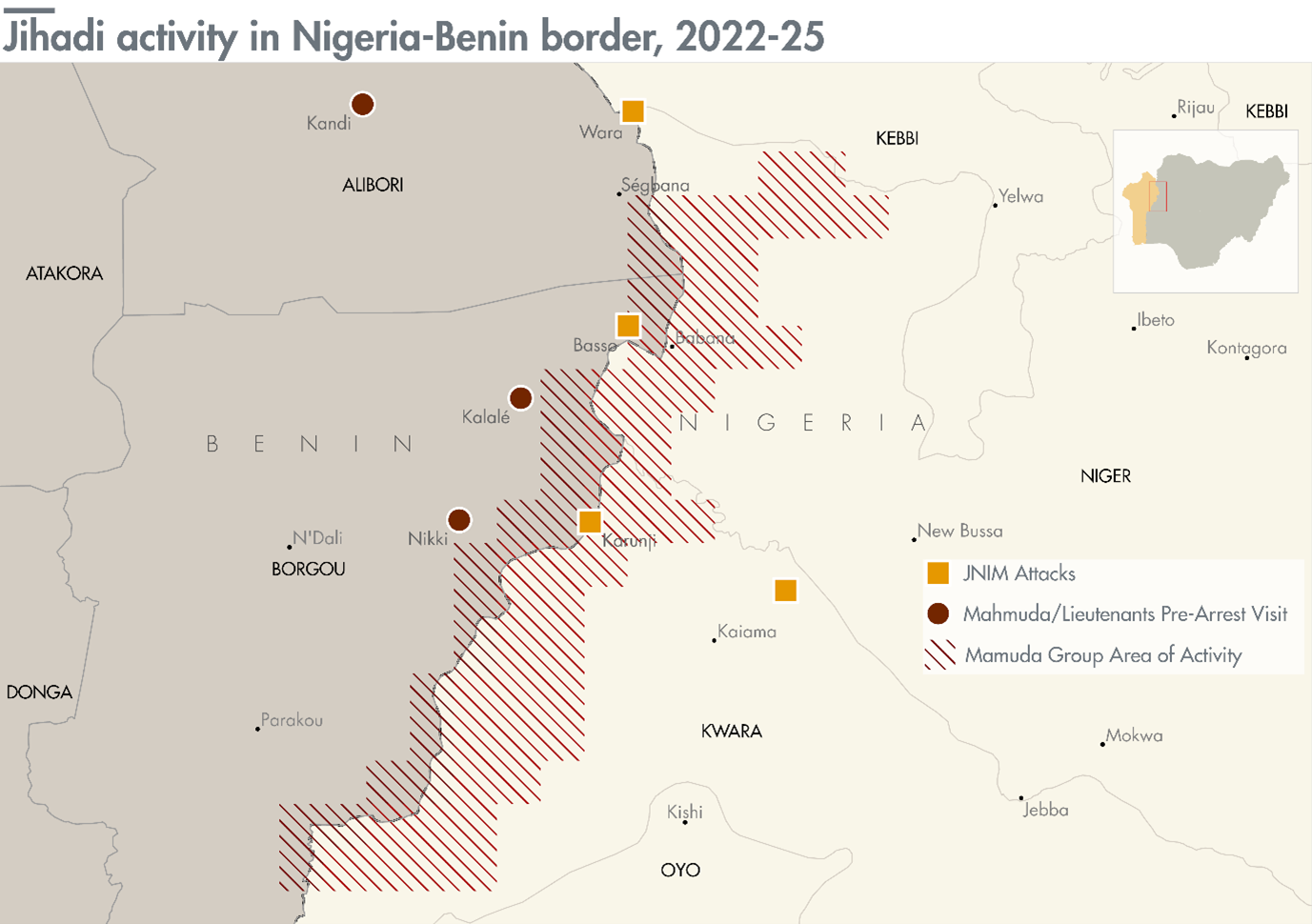

In November 2024 and April 2025, respectively, Nigerian and international media reported with consternation the emergence of two new terrorist groups operating in the country’s northwestern and north-central states,a known as “Lakurawa”1 and the “Mahmuda group,”2 respectively. Neither of the groups were exactly “new,” however. Lakurawa—a local Hausa term for militants from neighboring Sahel states—had been making incursions into communities in Nigeria’s Sokoto state near the Nigerien border since late 2017, while the group led by “Mallam Mahmuda” had operated in central Nigeria near the border with Benin since approximately 2020. Indeed, when Nigerian authorities arrested Mahmuda in August 2025, marking one of the country’s biggest counterterrorism successes in recent years, the country’s national security advisor linked Mahmuda to Ansaru, an early al-Qa`ida-aligned splinter faction of Boko Haram, and said that he had been active in various groups, Nigerian and foreign, for over a decade.3

The arrests raised important questions about the evolution of jihadi violence in Nigeria and West Africa more broadly:b How are jihadi groups entering ‘new’ regions? Are Nigerian jihadi groups and groups from the Sahel converging and cooperating? How relevant are the remaining veteran commanders of the Boko Haram conflict (now in its second decade4) to dynamics today?

As this study argues, the geography of jihadi violence in Nigeria has not been confined to Borno state in the country’s northeast, the geographic origin point and longstanding locus of the Boko Haram insurgency,c for some time. Nigeria faces threats from various jihadi factions operating in far-flung corners of the country, even as the two main jihadi groups operating in the northeast have also escalated their attacks in 2025, putting hard-won military gains at risk.5

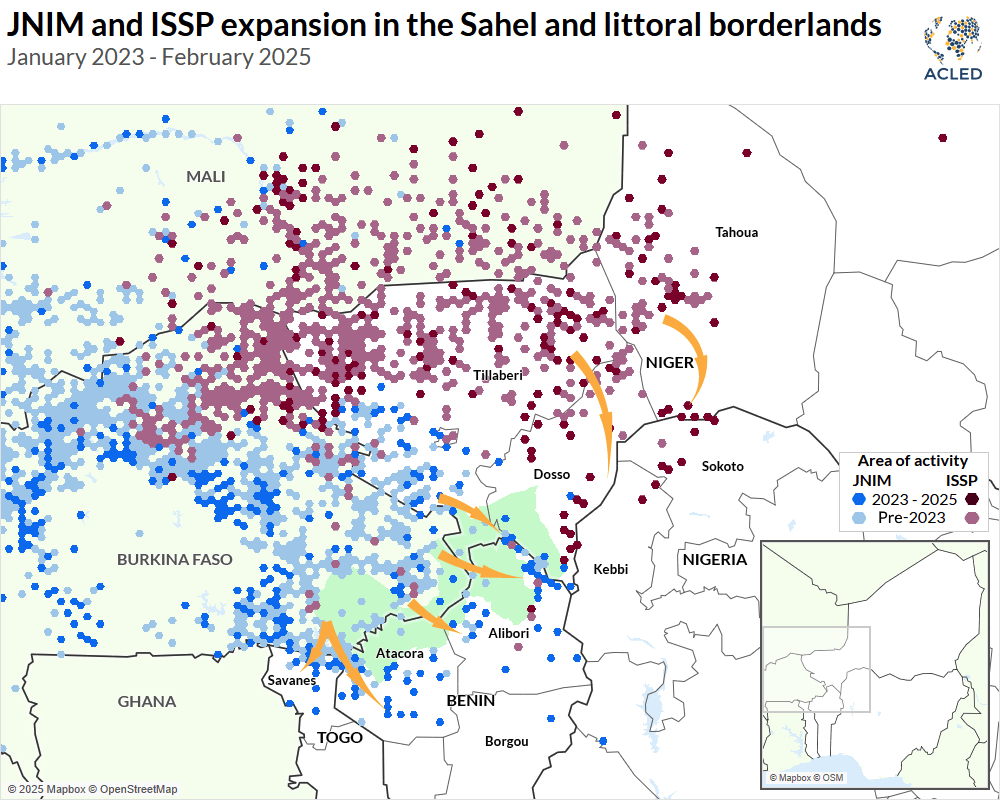

Yet to say, as most analysts do, that jihadis have “expanded” into northwestern, central, or even southwestern Nigeria—what the authors broadly refer to as “western” Nigeria for the purposes of this study—is also only partially correct. In some cases, jihadi groups from neighboring Sahelian states—the Islamic State’s Sahel Province, and Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM, al-Qa`ida’s affiliate in the Sahel)—are in the process of establishing or consolidating actual contiguous stretches of free movement and influence across Nigeria’s borders, expansion in a truer sense of the word. Yet in other cases, long-dormant Nigerian jihadi cells have been reactivating in locations far removed from any other jihadi-controlled territory or simply relocating to remote patches of forest on the other side of the country. Some of these networks have had significant success in these endeavors, while others have faced setbacks. Examining these jihadi failures alongside the successes, the authors believe, offers important lessons with relevance beyond Nigeria.

This study, based on months of collaborative fieldwork across Nigeria, aims to provide a detailed assessment of the extent to which different Nigerian and Sahelian jihadi groups have either expanded into or relocated within different parts of the country over the past five years. The authors uncover a far more nuanced phenomenon at play than is sometimes depicted in media and analytical reports, although they do not downplay the risks that Nigeria faces of further and more widespread jihadi violence in the coming months and years. In particular, the authors identify two key trends that can help observers and analysts understand where jihadis find success and where they face setbacks.

Key Findings and Primary Arguments

The first finding builds on a previous study by the first author6 related to the volatile relationship between jihadis and Nigeria’s bandits, the latter a powerful and deadly set of militants who dominate swaths of rural northwestern and central Nigeria (albeit highly fragmented among dozens of gangs).d The authors find that jihadis appear cognizant of both the benefits that they can achieve by collaborating with bandits as well as the drawbacks—the benefits being financial and operational, the drawbacks being friction with territorial bandit gangs as well as reputational liability in the eyes of the rural communities in northern Nigeria whose loyalty they are trying to earn. Far from seeing bandits as a means of consolidating their insurgent hub,7 as many analysts and officials have worried for several years, jihadis have probed new areas in northwestern Nigeria and found the most amenable conditions in areas where bandits are present but somewhat weaker in their influence, suggesting that there is a “Goldilocks effect”—areas of equilibrium (some bandits, but not too many) in which jihadis can reap the benefits of banditry without as much of the attendant risk. Relatedly, the authors find that Nigeria’s jihadis rarely adopt wholly consistent approaches to banditry, in contrast to neighboring countries in the Sahel where jihadis have been largely successful in mass cooptation of local bandit networks;8 in Nigeria, the most successful jihadi groups instead aim to strike a balance between selectively cooperating with bandits for tactical gain and fighting other bandits to establish themselves as security providers for neglected rural communities. As will be shown, achieving this balance is difficult. In this regard, this study adds to a growing body of literature on the ‘crime-terror nexus’ that underscores some of the risks and liabilities that ideological insurgent movements such as jihadis may incur by working with criminals.e

The second finding reinforces the importance of what one might call the “micro-” and “meso-social” dynamics of jihadi insurgencies in shaping their trajectories of expansion. Much of the analysis on jihadi expansion in Africa focuses on “macro” factors such as porous borders,9 climate change,10 or the role of jihadi strategy at a high level,11 all of which are indeed important elements. However, the present research also underscores the extent to which jihadis typically choose to expand, relocate, or build cells in regions where their commanders have existing social ties, mirroring findings from studies of jihadi group formation, recruitment, and expansion in places such as Indonesia,12 Somalia,f and Iraq and Syria.13 g The expansionary efforts of each of the groups analyzed in this study have typically been overseen by autonomous commanders who rely on kinship, ethnicity, and other shared social networks (sometimes centered around specific mosques and Islamic schools) in their endeavors. The authors demonstrate this through a case study of Kogi state in central Nigeria, where both Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Ansaru have tapped into an important, if long overlooked, local jihadi scene. This extremist ‘milieu’ in Kogi first emerged in the 1990s with a hyper-local agenda rooted in disputes among different Muslim sects and traditional religion worshippers, with these social networks eventually forming the backbone of respective ISWAP and Ansaru campaigns decades later. Ideological conditions in Kogi were conducive to the emergence of jihadism in the area, as both Ansaru and later ISWAP recruited from a subset of the local salafi community that was, in some ways, already quite radicalized. But the authors argue that social ties are an equally significant part of the story, as personal relationships between members of this community have persisted and, in some cases, transcended the organizational and ideological divisions that would eventually emerge in the Nigerian jihadi scene.

Structure of the Study

The study continues below with a short note on the methodological strengths and limitations of this research. It then offers a brief explanation of Nigeria’s geography and ethnoreligious complexity and how this influences jihadi expansion.

The subsequent sections of this study establish its empirical basis through five case studies of jihadi groups/networks that have operated in ‘western Nigeria’ in recent years. The five principal groups analyzed in this study are as follows:

Mahmudawa: a jihadi group led by a commander, Mallam Mahmuda (real name Abubakar Abba), who was active in Niger and Kwara states as well as parts of Benin between 2020 and 2025

JAS: Jama‘at Ahl al-Sunna li-Da‘wa wal-Jihad, the direct successor to the original “Boko Haram”h insurgency begun in 2009, led by Abubakar Shekau until his death in May 2021 and now led by Bakura Doro,i which is based in different remote corners of the northeast; the main JAS commander in the northwest is known as Sadiku.

ISWAP: the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), the strongest jihadi group in Nigeria and a provincial affiliate of the Islamic State, which first emerged in a 2015 split with Boko Haram/JAS14

Ansaru: Jama’at Ansar al-Muslimin fi Bilad al-Sudan (“Vanguard for the Protection of Muslims in Black Africa”), better known as Ansaru, an early al-Qa`ida-affiliated splinter group of Boko Haram/JAS that was active in the early 2010s and has resurfaced in northwestern and north-central Nigeria in recent years; Ansaru seems to have further factionalized in recent years, with one network being active in Kaduna state in 2020-2022 and another centered in Kogi state and southwestern Nigeria in recent years; the factions may have been in the process of reconciling as of early 2025, but there is much conflicting information on the current status of the group(s).

“Lakurawa”: the local Nigerian term for militants from Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, most of whom are likely affiliated with the Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISSP) and who have been intermittently active in border regions of northwest Nigeria since 2017

In the section on Mahmuda’s group, the authors also provide a shorter analysis of JNIM (Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin), the al-Qa`ida-affiliated group active across the region from northern Mali to Benin that is estimated to be the most powerful jihadi group in West Africa.15 This group recently claimed its first attacks in Nigeria and appears to have ties with Mahmuda’s group, which merits a brief discussion in that section.

In the second half of the study, the authors elaborate on their key arguments regarding the factors behind jihadi expansion in Nigeria: the centrality and complexity of bandit-jihadi relations, and the importance of social and religious ties in building durable networks of expansion.

A Note on Methods

This study draws on fieldwork conducted across Nigeria and interviews with key sources who have first- or second-hand information on the dynamics in question. These sources include senior jihadi defectors, former bandits who have collaborated with various jihadis, members of communities that live under jihadi control or influence, security officials who have been tracking these groups, and individuals who have communicated with members of these groups—sometimes extensively—in the course of negotiating (e.g., the release of hostages or the defection of a senior commander), whom the authors refer to in citations as “intermediaries.”j In this effort, the research team (which includes several anonymous contributors) conducted dozens of interviews and several focus group discussions across 12 states in four of Nigeria’s six sub-national regions (geopolitical zones).k The authors also leveraged media reports, original open-source research on conflict incidents, data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED), as well as propaganda published by different jihadi groups to augment the analysis. For the purposes of visualizing certain conflict incidents and armed group control, the authors also utilized conflict data collected by the Clingendael Institute and ExTrac.l

Fieldwork and primary source research on conflict are invariably difficult and pose limitations. This study references secondary literature wherever possible and insofar as such secondary sources seem reliable. However, given the fact that the expansionary efforts of the groups in this study have not been written about in extensive detail, the study relies to a large extent on original interviews and fieldwork. In many cases, the authors were able to independently interview multiple sources with first-hand knowledge of a specific jihadi commander because they had, for example, served under that commander, resided in their camp (for example, as a wife of a fighter), or were a relation or old friend of the individual.m While not without their biases or shortcomings, these sources typically provided insights that were specific, detailed, and—when multiple testimonials were compared together—corroboratory. In other cases, the authors struggled to identify sources who were as close to the key individuals in question and instead relied on sources who have interacted with jihadis but may not have as detailed information.n The authors have characterized the sources in the endnotes (while maintaining their anonymity) to give a sense of how ‘proximate’ the sources are to the individual/group in question.

The level of empirical insight into each of these groups is admittedly somewhat uneven: Some groups, such as JNIM, appear to have had an inconsistent presence in Nigeria and thus limited contact with the sources interviewed. Furthermore, the chronology of jihadi networks can be hard to establish with any certainty when relying even on the testimony of former members of these networks, as sources often struggle to remember precise dates from years ago. Consequently, the assessments of certain groups’ or individuals’ histories herein are vague in places because the authors received contradictory dates for key events, or because their sources would use organizational labels and distinctions that exist today (e.g., Ansaru and ISWAP) to refer to events that predate the emergence of such groups. While cognizant of the limitations of this research, the authors endeavor to present their best assessment of the groups in question.

The Complexity of Identities and Geography in Nigeria

Nigeria unfortunately faces a fluid and diverse array of threats from non-state armed groups, which is reflective of the country’s size and complexity. While ethnic and religious identities are as complex in Nigeria as anywhere else,o they are also inescapable in this analysis, as many armed groups have mobilized around explicit ethnic or religious grievances. Contra simplistic framings of Nigeria as a country merely divided between a Muslim north and a Christian south,16 the relationship between ethnic and religious identities is much more complex than many analysts—and apparently some jihadis—might assume. If one is to presume that the ultimate objective of jihadis is the “destruction of current Muslim societies through the use of force and creation of what they regard as a true Islamic society”17 and that jihadis seek to exploit existing social fault lines to do so,p then this ethnoreligious complexity is bound to present opportunities, but also plenty of challenges, to jihadis in these strategic efforts.

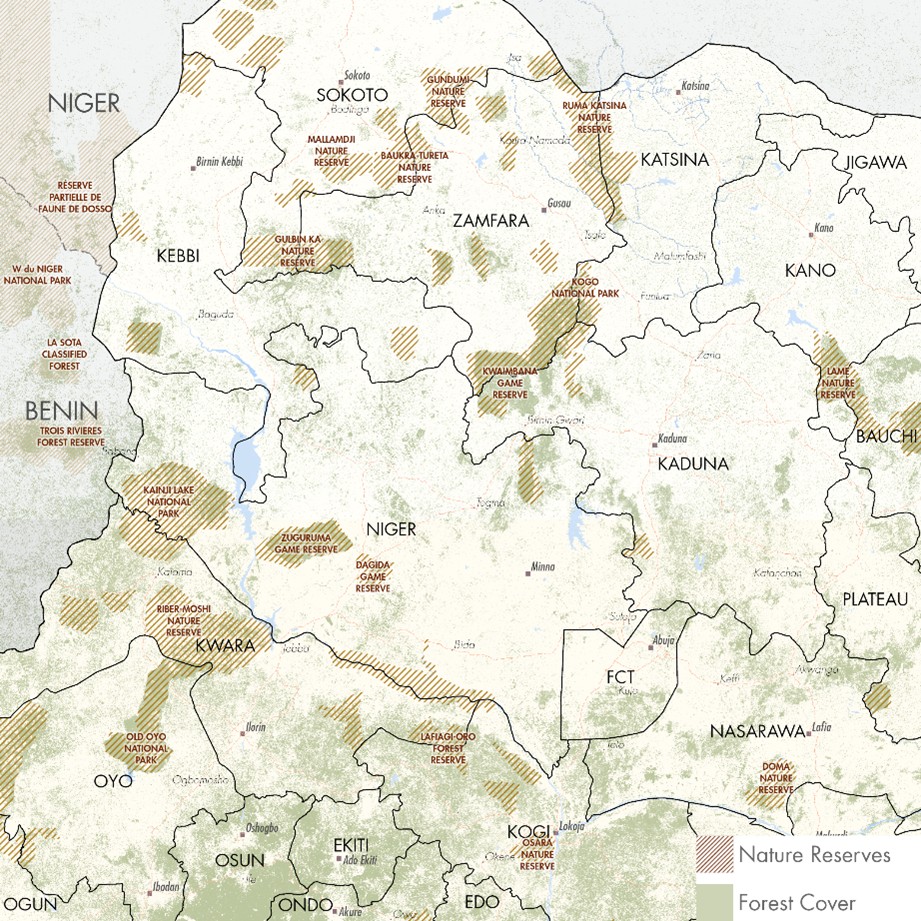

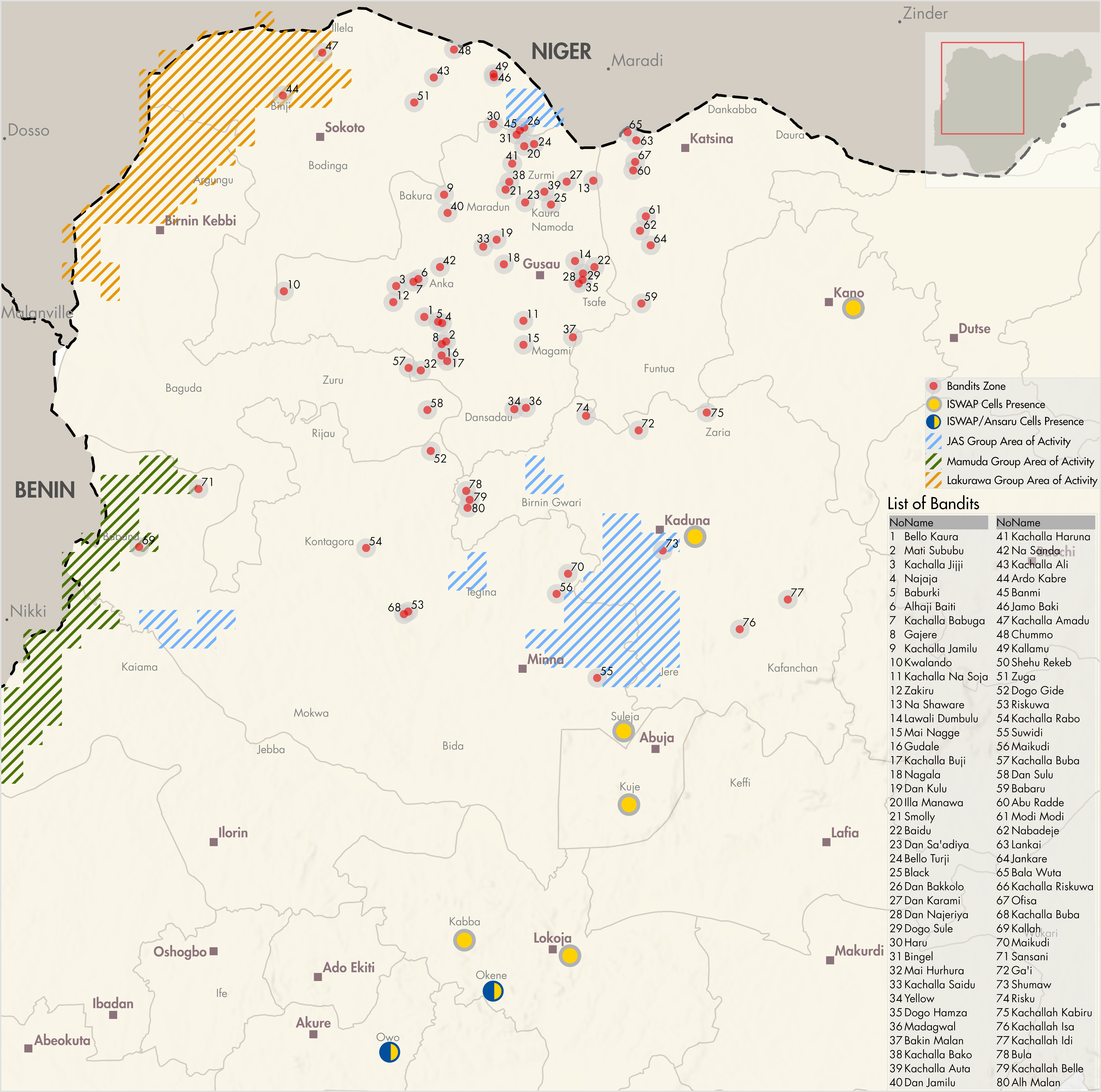

Importantly, in the northwest, many of Nigeria’s bandits are ethnic Fulani herdsmen who claim to have taken up arms as a result of the government’s neglect of pastoralist rights amid growing conflict with farming communities (these farmers typically identify as Hausa, although many other ethnic groups reside in states such as Kaduna, Kebbi, or Niger).18 This is notable insofar as Nigeria’s jihadi insurgencies have typically drawn from a different, non-Fulani ethnic base in the country’s northeast. Moreover, Nigeria’s most destructive bandit gangs largely hail from and operate in Muslim-majority areas in the northwestern states of Zamfara, Sokoto, and Katsina as well as parts of Kaduna, Niger, and Kebbi states (refer to map in previous section). Consequently, Muslim civilians constitute a sizable portion, if not the clear majority, of both the perpetrators and victims of banditry in the northwest.

As this study will show, this simple yet important fact poses a challenge to jihadi groups whose strategies rely on a population-centric insurgency aimed at winning support of vulnerable Muslim communities against the Nigerian state. This lack of shared ethnic identity and differing treatment toward northern Nigeria’s Muslim populations have, among other factors, impeded a greater degree of cooperation and convergence between Nigeria’s bandits and jihadis to date.19 By contrast, the two Sahelian jihadi groups of note, ISSP and JNIM, have both successfully exploited Fulani pastoralist grievances in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso and consequently recruited from those communities.20 It might stand to reason, in that case, that Sahelian groups like “Lakurawa” have had more success recruiting bandits to their cause in the course of expanding into Nigeria than Nigerian jihadis have. But as the authors will show, this has not necessarily been the case.

As such, in most northwestern states like Sokoto and Zamfara, jihadis are, to oversimplify somewhat, inserting themselves into communal conflicts between Muslim ethnicities (Hausa and Fulani). Because both communities are Muslim, jihadis should theoretically prefer to see both sides lay down their arms and join the jihadis in their fight against the Nigerian government. But if this approach does not work, as it often does not, it forces jihadis to effectively pick sides in a complex communal crisis. Because there are benefits and drawbacks to aligning with one side over another and because local conflict dynamics are fluid, jihadis in the northwest typically adopt pragmatic and flexible approaches to the banditry crisis. This forms the first key finding of this study, which the authors will demonstrate through several case studies.

Conversely, in Kogi state in central Nigeria, jihadi networks have formed as a result of intra-Muslim sectarian tension within an ethnic group (the Ebira) in which Muslims and Christians have traditionally coexisted. In other words, if in, for example, Sokoto, jihadis principally navigate ethnic divisions among Muslims, in Kogi (and, increasingly, southwestern Nigeria), they seek to accelerate and exploit religious and sectarian divisions within the same ethnic community. Ebira jihadis in Kogi have had some success in this regard, while still constituting a fringe movement within their community. Thus, despite being geographically far removed and quite socially distinct from the locus of the jihadi insurgency in the northeast, Kogi has become an important launching pad for jihadi expansionary efforts, as detailed in the penultimate section of this article.

The Mahmuda Group

Around 2021, residents in the Borgu emirateq that surrounds Kainji Lake National Park in Niger state began to witness armed men traversing the forests outside their communities on motorbikes, occasionally stopping in villages to purchase goods and warn residents against informing the security forces of their presence.21 Locals could often tell that the militants were not bandits, as these men tended to preach diatribes against local traditional rulers and “non-Islamic” gender norms that were common to the region.r The militants did not identify themselves, but eventually, some communities began referring to the group as Mahmudawa after its leader, Mallam Mahmuda.22 Over the next few years, this group gradually moved southward from Niger state into the Kaiama and Baruten communities in neighboring Kwara state, and eventually as far south as the northern fringes of Old Oyo National Park in Nigeria’s southwest, taking advantage of the extensive forest cover connecting Niger, Kwara, and Oyo states.23 (See Figure 2.)

The identity and affiliation of Mahmuda’s men remain a matter of debate. The data collected from the authors’ fieldwork in 2024-2025 strongly suggested that Mahmuda’s faction was independent of any other jihadi group and that it could at least partially trace its lineage to a splinter of Darul Salam,s an Islamist rejectionist sectt that first emerged in Niger state as early as the 1990s (first as a non-violent movement) and later reached a temporary accommodation with the JAS commander Sadiku before being dislodged from Nasarawa in 2020 and splintering further (see subsequent section). However, since Mahmuda’s arrest in August 2025 by Nigerian intelligence operatives, the authorities have publicly listed him as the deputy commander of Ansaru subordinate to Abu Baraa (see section on Ansaru for more).26 u The authors have admittedly not seen any concrete evidence that he was previously a member of Darul Salam, although his exact relationship with Ansaru remains equally unclear, and the authors’ sources indicate that he knew various factional commanders in Nigeria, suggesting that he may have had fluid alliances or affiliations.

Rather than attempt to provide a definitive assessment of the question of Mahmuda’s affiliations at this stage, the authors instead treat him as the leader of an independent group for the purposes of this study, while also recognizing that he has had relationships with other jihadi commanders in Nigeria (and apparently abroad). Mahmuda’s group operated with a high degree of autonomy, with Mahmuda himself acting like a local powerbroker in his dealings with communities. It is therefore useful to think of his movement as effectively its own minor insurgency in the western fringes of Niger and Kwara states.

Mahmuda’s Emergence and Modus Operandi

Mahmuda is a Hausa from Daura in Katsina state in the country’s northwest, the son of a religious and well-respected former ward councilor.27 Former neighbors from Katsina describe him as smart, honest, and passionate about religion,28 and Nigerian newspapers have reported that he used to sell audio and video tapes of Islamic preachers, including the late Mohammed Yusuf, founder of the “Boko Haram” insurgency.29 Precise details of his trajectory within the jihadi orbit are unclear, but his neighbors report that he disappeared from home around 2010 or 2011 after intelligence agents attempted to arrest him, indicating that he was likely an early member of JAS,30 although he seems to have eventually left the group. Mahmuda reportedly traveled to Somalia, Niger, and Libya at various points in the 2010s,31 which would indicate that he was likely an early member of Ansaru, which was the more international-oriented faction of Boko Haram.

The precise reasons behind his group’s emergence in Niger state around 2021 are unclear, but it is notable that this was a time when various jihadi networks were relocating to or moving around within the broader northwest, including the JAS cell under Sadiku, the Ansaru group under Mala Abba, and possibly militant members of the Darul Salam sect. If Mahmuda knew some of these other networks as well those whom the authors interviewed claim, then he might have sensed an opportunity to establish his own jihadi enclave in western Niger state, a remote region far from other, potential rival groups.

Prior to his arrest, Mahmuda and his brother, Aiman, oversaw a relatively small but influential network that operated across a wide swath of forests and nearby communities (Aiman typically assuming day-to-day management of operations as Mahmuda traveled frequently).32 Witnesses described Mahmuda as a skilled orator well-versed in the Qur’an.33 Mahmuda’s group never produced any formal propaganda, the closest thing to official statements being a series of audio messages from Mahmuda circulated on WhatsApp to communities surrounding his group’s camps, in which he explains his group’s religious mission and justifies his actions. In these audios, he typically refers to his group as “people of the forest” and his fighters as “students,”34 although one individual who witnessed Mahmuda open a school in the forest in Kwara state said that he called it Darul Salam.35

Initially, Mahmuda’s group focused on dawa (proselytization) by preaching to the communities within the Borgu emirate and was relatively non-confrontational. One vigilante member from Kwara state recalls:

When they captured two of my vigilantes, insisting they would take them if I didn’t come, I decided to meet them. I was greeted by their members, who claimed they were not there to cause violence. They requested that we send our boys to teach them, assuring us that as long as we did not attack them, they would not attack us. After our meeting, they did not come into our villages or attack us, but they would stop people on the road to ask questions.36

In keeping with the group’s initial preference for dawa over violence, Mahmuda made overtures to the local salafi community (often referred to colloquially as Izala, after the name of the most prominent Nigerian salafi-adjacent organizationsv) during his first months in Borgu. This was an unusual step for a Nigerian jihadi group: Ever since Mohammed Yusuf had fallen out with the salafi mainstream by the late-2000s, salafi clerics have consistently condemned the takfiri violence of Yusuf’s successors.37 Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, Mahmuda’s approach was unsuccessful. As one respondent recalled: “Since Mahmuda’s group operates in the forest, all the Izala people refused to work with them.”38

Mahmuda had more luck with traditional rulers in the Borgu area. Jihadi commanders often seek arrangements with traditional rulers, who might be desperate for alternative sources of security provision.w But in Mahmuda’s case, it seems that the traditional rulers were simply looking to collect the fees that such rulers often feel they are entitled to for conducting any meeting or business with outsiders. As one source in Kaiama explained, “[The traditional ruler] took money for sheltering them. They told him they came to preach and gave him ten million naira [approximately 6,800 USD] … Traditional leaders generally like visitors because they pay them a sheltering levy; Fulani and migrants do it a lot.”39

It would be a mistake to characterize Mahmuda’s group as having ever been truly non-violent, however. Dawa was a way of recruiting people into a movement that was clearly preparing for a conflict of one sort or another, as one source recalled: “Wherever he went, he told people he wanted to teach them religious books. But after two weeks, he would persuade them to train with weapons and join his group.”40

Moreover, his group combined efforts at outreach with violence against individuals or communities who refused to cooperate. Mahmuda seemed to employ abductions as a tool of coercion, with traditional rulers or vigilante members being targeted for “detention,” as Mahmuda called it, until they would agree to work with the group, although the lines between coercive abduction and kidnapping-for-ransom were somewhat blurred in practice.x

Mahmuda employed a common jihadi strategy of attempting to win popular support by defending communities against bandits. As detailed further in this study, such a strategy poses a complex balancing act for jihadis and contains many potential pitfalls. In addition to being highly mobile and operating across the border in Benin (see below), one cell of Mahmuda’s group was reportedly rebuffed by vigilantes when it attempted to move southward into Kishi in the northern part of Oyo state in 2023 or 2024.41 It is possible that members of the group hoped to establish a small presence in Old Oyo National Park (where bandits operate and illegal mining takes place42 y) as part of a broader effort to establish a corridor near the Benin border, or simply as a fallback area after operations in Kwara. It is unclear, however, if they ever managed to sustain a cell in the park.z

Mahmuda’s audios and the authors’ interviews indicate that Mahmuda was generally confident in his popular acceptance among communities in Borgu emirate until early 2025, when the Nigerian and Beninois began intensifying operations against his camps. These operations prompted Mahmuda to lash out against the communities he perceived as complicit.43 In one of his last audios released in April 2025, Mahmuda spoke specifically to the communities around Baruten and Kaiama local government areas (LGAs)aa in Kwara, claiming that his group had sought good relations with the communities but that they had betrayed him by collaborating with the military.44 Finally, following months of military operations against the group,ab Nigerian Department of State Services (DSS) agents captured Mahmuda in August 2025.45 While the authorities have not released many details about Mahmuda since his arrest, it is possible that more will be learned about his group in the coming months. As of this writing, it remains an open question whether his group will fracture or if a new commander will assume control.

An Insurgency Cut Short, or JNIM’s Newest Affiliate?

Given the confusion among analysts regarding Mahmuda’s affiliation and mounting evidence of JNIM encroachment into Nigeria, the authors believe a brief discussion on Mahmuda’s potential ties to JNIM is merited. However, the analysis here is somewhat more speculative than in other parts of this study given the difficulty in getting verified information regarding JNIM’s presence in Nigeria.

Since early 2025, analysts have speculated about links between Mahmuda’s group and JNIM given the proximity between the two groups on different sides of the Benin-Nigeria border.46 There is indeed some evidence pointing to a relationship with JNIM. One security source noted that communications showed Mahmuda was in touch with a JNIM cell in Burkina Faso.47 Furthermore, Mahmuda and his fighters frequently crossed into Benin, visiting various locations in the Borgou and Alibori departments such as Kandi, Kalalé, and Nikki.ac While Nikki is farther south than JNIM has historically operated in Benin, the group has had a strong presence around Kandi, the northernmost of the three towns. Furthermore, JNIM claimed its southernmost attack within Benin to date in Basso (near Kalalé) along the Nigerian border on June 12, 2025,48 indicating that the group is gradually establishing freedom of movement within central Benin.ad (See Figure 4.)

As for JNIM, it is safe to say that the group is now operating on Nigerian territory, but it remains an open question how large and consistent a presence it maintains in the country. A video circulated on JNIM supporter channels in July 2025, shortly before Mahmuda’s arrest, that showed a group of seven fighters, at least one of them non-Nigerian in appearance, who claimed to be a JNIM cell in Nigeria.49 Then, on October 28, 2025, a video emerged that appeared to show JNIM fighters participating in their first attack in Nigeria, during which the fighters ambushed a small group of Nigerian soldiers in Kwara state. JNIM did not officially claim the attack through its formal media platform, but the video circulated on JNIM-affiliated channels and featured fighters self-identifying as JNIM taking responsibility for the operation.50 Less than a month later, on November 22, JNIM officially claimed (via its official al-Zallaqa media platform) an attack on a military position in Karonji, a community in Baruten LGA of Kwara along the Benin border.51

Given the limited number of fighters featured in the July 2025 video and the small scale of the October 2025 attack and later the November 2025 attack claimed by JNIM, it is not unreasonable to speculate that the group’s presence in Nigeria might be relatively small at the moment. But the fact that the October and November attacks, as well as reports of suspected movements by JNIM fighters into Nigeria since as early as 2020,52 coincide with the rough area of operations of Mahmuda’s group also raises the possibility that the two groups are collaborating or at least tolerating each other’s presence. Once again, the authors do not have hard evidence and can only speculate, but it is fair to presume that collaboration between the two groups would be one way for an otherwise small JNIM cell to operate in Nigeria—for example, Mahmuda’s group providing a base and logistical support to JNIM. The arrest of Mahmuda creates yet another layer of uncertainty as the authors are not presently certain of the group’s new leader, let alone their dispensation toward JNIM. These questions are quite significant given the implications of a larger JNIM presence in Nigeria amid all the other challenges the country faces. As such, this issue bears further research and monitoring.

Sadiku’s Jihad: The JAS Experiment in Northwest Nigeria

A JAS commander known as “Sadiku” (a nom de guerreae) has been one of the most successful Nigerian jihadi entrepreneurs outside the northeast, carving out a niche in the hills that bound Kaduna and Niger states since approximately 2020 and engaging in some of the most successful operations of any jihadi in the region. Sadiku’s group serves as a fascinating case study of how jihadis navigate unfamiliar terrain in their efforts at expansion, and for this reason, his group is the subject of a separate, forthcoming study.af For the purposes of this study, it suffices to provide some brief background on Sadiku’s group and assess his approach toward managing relations with bandits and the local population.

Sadiku has been a mysterious figure, and the first author has in fact mistakenly identified him as a native of the northwest in the past.ag However, it is now clear from speaking to six former associates of his that he is an ethnic Babur, a minority found in southern Borno, and an early member of Yusufiyyaah with a relatively advanced degree of Western and Islamic education by the standards of JAS commanders.53 Around 2020, then JAS leader Abubakar Shekau designated Sadiku (or Sadiku and another commander, as some former associates recall54) as his envoy to the Darul Salam sect based in Nasarawa. While Sadiku seems to have worked closely with Darul Salam, helping their members learn bombmaking skills in an attempt to win their loyalty, he seems to have also been working to establish a JAS cell in Shiroro LGA of Niger state around this same period, with reports of jihadi-like attacks on villages beginning in early 2020 and escalating in 2021.55

When the military launched operations against Darul Salam’s communes in Nasarawa in 2020, Sadiku’s base of operations shifted to the hilly area straddling Shiroro LGA of Niger state and Chikun LGA of neighboring Kaduna state. At least a few Darul Salam members relocated with Sadiku to Kaduna/Niger and joined his JAS network,ai but others refused to join JAS while others still were detained in the military raids.56

It seems Sadiku took little time to broker two sets of agreements, broadly defined, in order to establish his group’s new bases in Chikun and Shiroro LGAs. This area is principally inhabited by the Gwari, also known as Gbagyi, a minority community in central Nigeria who have largely been displaced from their homes since the 1990s when the government moved the federal capital to Abuja. These communities were suffering from bandit attacks when Sadiku stepped in, offering his group as a security provider to those communities in return for their cooperation and support.57 That many of the Gwari are Christian mattered little to Sadiku who, in stark contrast to JAS’ approach in the northeast, did not interfere with the Gwari villages around his bases in Chikun, allowing them to attend their churches and more or less go about their lives unimpeded.58 aj In return, these villagers would help Sadiku’s group gather supplies, transport fighters (and sometimes hostages) along rural roads, and provide intelligence of any security forces in the region.59

The second group that Sadiku needed to find an arrangement with were the local bandits. The region where his group operates is home to numerous gangs, including some that are linked to several of the biggest warlords in the northwest. Beneficial relations with these bandits could allow Sadiku to tap into the lucrative illicit economy of the region—dominated by cattle rustling, kidnapping for ransom, logging, and gold mining—while hostility toward the bandits could result in his still-small group being overrun in their new bases. Yet, embracing the bandits wholeheartedly would not only have undermined Sadiku’s own credibility as a jihadi60 but also harmed his effort to win the trust of the local Gwari communities.

Sadiku’s approach to banditry was thus to employ both carrot and stick: Early in his foray into the region, he called a number of bandits who had been raiding Gwari villages in Chikun LGA and encouraged them to join his group to gain sophisticated weapons (e.g., IEDs) in return for reaching an arrangement with the local Gwari villages.61 Some agreed, while those who refused became valid targets for Sadiku’s group, who began attacking the bandits as a way of earning the support of the local Gwari (a similar tactic to what Ansaru was doing in another part of Kaduna around this time,62 as well as Lakurawa in parts of Sokoto63). At the same time, Sadiku formed pragmatic alliances with some of the stronger bandit warlords in the northwest, such as Dogo Gide, the late Ali Kawaje, and Dankarami (aka Gwaska),64 although his relationship with Dogo Gide deteriorated and resulted in conflict in early 2025, as detailed in a subsequent section.

Sadiku’s group was responsible for an audacious March 2022 attack on the rail line that connects Abuja to Kaduna. With the support of some bandits,65 ak his fighters used explosives to sabotage the rail track before taking dozens of passengers hostage.66 After months of negotiations, his group secured hundreds of millions of Naira (tens of thousands of dollars) as ransom along with the release of several associates who had been in detention (including children of Sadiku and his associates who had been picked up by the military in Nasarawa in 2020 and subsequently housed in an orphanage).67 The windfall from the train kidnapping helped Sadiku keep his commanders, bandit partners, and even members of the local Gwari community satisfied, although it also strained his relationship with the overall JAS leader in the northeast, Bakura, who expected that some of the proceeds would make their way to the northeast.68 (The authors’ understanding is that Sadiku remains loyal, as of this writing, to Bakura and at least nominally part of JAS, although he operates highly autonomously.)

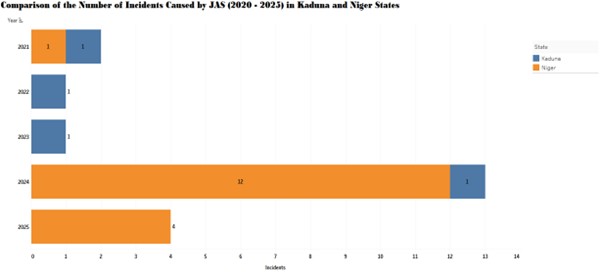

Yet, despite its limited popular outreach, Sadiku remains a violent militant. His group appears to be more hostile to parts of the population in Shiroro in Niger state than in Kaduna, where his relationship with local communities seems strongest (see Figure 5 below for a comparison of recorded attacks, per ACLED).al One resident of a community in Shiroro described the group’s relationship toward residents as one of “fraud” because the jihadis are often requisitioning goods from the communities without paying market price.69

Figure 5: Conflict incidents related to JAS in Kaduna and Niger states, January 2020 to July 2025 (Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data)am

The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, but one possibility is that his lieutenants in Shiroro are perhaps more aggressive than the lieutenants who oversaw the camps in Kaduna.70 Moreover, some of the communities in Niger state where Sadiku’s group operates fall under the influence of the bandit Dogo Gide,71 with whom Sadiku has had an inconsistent relationship (detailed later in this article). It is possible that Sadiku’s group has consequently viewed the communities in Niger with greater suspicion given their links to Gide. While Sadiku’s fighters have been forced to relocate within and outside Niger state since early 2025 due to clashes with Dogo Gide’s gang, his network has proven resilient in and will likely continue to operate in the northwest so long as it can find the right balance of influence with bandits and local populations.

ISWAP

No group has achieved more notoriety for its operations outside northeastern Nigeria than ISWAP. While always principally focusing its efforts on the insurgency against the Nigerian military in the northeast,72 in 2022, the group began claiming attacks in central and even southern Nigeria. The group claimed attacks in nine states outside of the northeast as well as in the Federal Capital Territory in 2022 and early 2023. (See Figure 6.) The most spectacular of these, a July 2022 attack (conducted with support from other jihadi groups) on Kuje prison in a suburb of Abuja that freed over 60 high-profile Boko Haram detainees,73 briefly led to a panic in the nation’s capital and was followed a few months later by another (thwarted) attempt in Abuja, this time to attack the country’s Defence Headquarters with a suicide vehicle-borne IED (SVBIED).74 an

Understanding how and why ISWAP undertook this campaign in 2022-2023 provides necessary context to one of the key findings of this study, which is that jihadis seek where possible to coopt existing social and religious networks in their efforts at expansion. According to defectors, ISWAP’s senior leadership had long debated whether to undertake the risk of a terrorist campaign targeting urban centers across northern Nigeria or whether to focus resources and energy in the northeast, where they felt they were gradually gaining ground.75 ISWAP experienced a power struggle around 2021 in which Habib Yusuf (aka Abu Musab al-Barnawi, son of the late Boko Haram founder Mohammed Yusuf) succeeded in purging an internal rival, Mustapha Kirmima, and reasserted himself as overall leader of the group.76 ao

Habib reportedly felt ISWAP should undertake a campaign in “Nigeria” (what ISWAP fighters call the rest of the country, as opposed to the northeast—i.e., part of the broader Islamic State “caliphate”77) and had a relationship with a two key commanders, Abu Qatada and Abu Ikrima, whom he felt could oversee the campaign.78 As Habib saw it, the benefits of a campaign outside the northeast could be manyfold—including gaining additional revenue from kidnapping and money laundering, winning new recruits (including by freeing veteran jihadis from prisons),ap tying down military forces far from ISWAP’s base of operations, and simply exacting revenge against the Nigerian state.aq After ISWAP killed Shekau in May 2021, Habib likely also felt that a campaign in western Nigeria could rally the remaining Nigerian jihadis outside his fold, namely the Ansaru faction that was reasserting itself in Kaduna at the time (see subsequent section), thereby reunifying the Nigerian jihad under one banner as it had (briefly) been under his father.ar

Abu Qatada and Abu Ikrima were both ethnic Ebiras from Kogi state.79 Kogi was an ideal hinge-point for ISWAP’s expansion both because of its geography—situated beneath Abuja and on the edges of the southwest—and because of its small but important jihadi scene within the Ebira community that could potentially be rallied for ISWAP’s campaign. The authors’ sources offer somewhat conflicting reports as to whether Habib chose Abu Qatada to oversee operations, with Abu Qatada then deputizing Abu Ikrima to relocate to the north central region for day-to-day management of the campaign, or if Abu Ikrima took the initiative to propose a campaign based in Kogi to Habib, with Habib urging both Abu Qatada and Abu Ikrima permission to collaborate. In either case, according to one defector, Abu Qatada was nominally Ikrima’s superior, while Abu Ikrima spent much of 2022 and 2023 on the move across Nigeria while overseeing a network of fighters based in Kogi.80

Ikrima’s network was highly active in the second and third quarters of 2022, conducting a string of ISWAP-claimed shootings and bombings in Kogi and parts of neighboring Ondo and Edo states as well as participating in the Kuje prison break.81 Ikrima’s network helped plan the latter, representing the highwater mark of ISWAP’s Kogi-based campaign (although some reports suggest many of the attackers were ISWAP fighters dispatched from Lake Chad for the operation,82 while members of other jihadi groups also likely took part83).

Following the success of the Kuje assault, Ikrima promised Habib that his network could strike a series of more ambitious targets, including targets in Abuja and other detention facilities across northern Nigeria.84 According to defectors, Habib agreed to lend Ikrima dozens of AK-47 rifles and provided funds for the operations.85

However, Nigerian intelligence agencies were on alert after the Kuje attack and learned of the impending operations.86 Additionally, one source claims that Ikrima’s network had to recruit new fighters from Kogi and neighboring states in order to have sufficient manpower to conduct the operations, leaving these fighters with little time to train or even learn the true nature of their operations until the last minute, which resulted in the fighters making a string of tactical and operational security mistakes.87 In late October 2022, Nigerian authorities thwarted several simultaneous plots by Ikrima’s network, killing or capturing several dozen of the fighters in his network.88 Ikrima’s star within ISWAP tanked after the failure of this second round of attacks.89 Unable to return the rifles ISWAP had lent him, Ikrima reportedly avoided returning to the northeast for fear of being branded a traitor and instead moved around different parts of north central Nigeria where he had contacts among fellow Kogi jihadis, including members of Ansaru.90

ISWAP’s expansion into central Nigeria lost momentum by 2023: While Abu Qatada and another ISWAP commander from Kogias reportedly continued the effort after Ikrima’s falling out, Nigerian security agencies managed to arrest and neutralize various members of their networks.91 Additionally, growing conflict between ISWAP and the Bakura-led JAS faction around Lake Chad in late 2022 forced ISWAP to divert energy and resources away from expansion toward the factional conflict closer to home.92 ISWAP ceased claiming attacks outside the northeast in early 2023, with the exception of a shooting at a supermarket in an Abuja suburb in January 2024.at

However, since mid-2023, Nigerian intelligence agencies have arrested apparent ISWAP cells in various locations across central and even southwestern Nigeria,93 indicating that the group has continued trying to build a network of urban cells to leverage for future campaigns outside the northeast.au These cells, dispersed as they are across the country, may be intended to offset the risks that came with relying on a network based principally in one state, Kogi, that had a history of operating autonomously and fragmenting, as detailed further in this study.

Two Ansarus? Kaduna and Kogi

Ansaru was one of the first groups to splinter from Boko Haram, forming around 2011-2012, and it has long been a subject of debate and speculation among analysts given its more secretive nature and apparent ties to al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).94 The early group conducted several attacks across Nigeria’s northwestern and north-central states between 2012 and 2013, including multiple kidnappings of Western nationals, before Nigerian security forces began dismantling the group’s cells in 2014, culminating in the arrest of founding member Khalid al-Barnawi in the Kogi state capital in 2016.95

This section briefly analyzes two distinct and contrasting campaigns that have each been attributed by analysts and Nigerian officials to Ansaru, one being an overt insurgency seemingly inspired by JNIM that took over a small patch of Kaduna state between 2020 and 2022 and seemingly signaled Ansaru’s reemergence as a regional jihadi actor; and the other being a clandestine and unclaimed campaign of terrorist attacks, kidnappings, and bank robberies that has occurred across Kogi state and parts of southwestern Nigeria over the past decade. The modus operandi of these two apparent networks—the one in Kaduna, reportedly led by one Mala Abba, and the one in Kogi, reportedly led by one Abu Baraa—were so different that the authors assess that the two groups actually split from each other for a time, a rift that is further attested to by one public communication released by the Kaduna-based group (see below).

Ansaru’s insurgency in Kaduna was detailed in two previous studies by the first author. The group adopted a ‘hearts and minds’ approach to communities in the Birnin Gwari LGA of the state that had long been suffering from banditry. Aligning itself with the Hausa communities in those villages, Ansaru began fighting the surrounding smaller gangs, all while boasting of its exploits on al-Qa`ida-linked Telegram channels and preaching to communities about the necessity of jihad and the failures of democracy and the Nigerian government.96 The group was successful for a time, earning some genuine popular support from otherwise desperate villagers, and members of the group began intermarrying with local communities as part of a broader effort at integration.97 However, this overt insurgency was abruptly cut short in the summer of 2022 when the bandits that Ansaru had been antagonizing teamed up and drove the jihadis out of their enclaves in Birnin Gwari.98 The group has since gone quiet,99 making no public statements since that time. The authors have received sporadic reports since 2022 that suspected Ansaru members are still active around the northwest, including in neighboring Shiroro LGA of Niger state as well as parts of Zamfara, but their presence seems to be diminished, and it is difficult to determine if they are even operating as discrete cells or if the fighters have instead joined other jihadi outfits or even bandit gangs.

The authors have limited insight into the membership of the Kaduna-based Ansaru, except that locals who interacted with the group report that the fighters seem to have come from the northeast, which leads the authors to believe they were likely fighters in Shekau’s JAS who defected to form this new group in the late 2010s/early 2020s rather than members of the original Ansaru.av Details about the leader of this network, known as Mala Abba,100 are scant. Among bandits and jihadi defectors, he is rumored to have been captured and/or extrajudicially killed by security forces, though they provide differing dates between 2021 and 2024.101 It is possible that security forces have captured the wrong individual on multiple occasions, and it is likewise possible that Mala Abba is a nom de guerre used by whoever leads the network at a given time, in which case the network may have already seen multiple leaders come and go. Despite operating in relatively close proximity to Sadiku’s cell in Kaduna, a former member of that group recounted fighting Ansaru on several occasions and otherwise keeping their distance from them, underscoring the degree to which some of the factionalism of the early Boko Haram conflict (Ansaru having split from JAS as early as 2011) persists years later even in relatively “new” theaters of the jihad.102

Abu Baraa and Ansaru in Kogi

When Nigerian authorities announced the arrest of Abu Baraa in August 2025 alongside that of Mahmuda (although the two had been arrested in different locations at different times), they hailed it as the dismantling of the long-running Ansaru network in the country. The authors assess that Abu Baraa’s network had in fact operated separately from the rest of Ansaru in Kaduna for at least several years, although he may have been in the process of reconciling with the Mala Abba faction (or what remained of it) at the time of his arrest. This assessment is based on what the authors have learned about the highly autonomous nature of his associates in the period around 2020-2023. Moreover, Mala Abba’s network released an audio in 2022 in which they refuted claims, reportedly circulating in jihadi circles after the Abuja-Kaduna train attack, that Abu Baraa was their leader.103 Researcher Malik Samuel also noted reports of a rift between Abu Baraa and the rest of Ansaru.104

The arrest of Abu Baraa was nevertheless significant as he was a veteran jihadi commander. Daniel Prado Simón and Vincent Foucher provide a useful biography of Abu Baraa that largely corroborates what the authors learned about him from their sources.105 To briefly summarize, Abu Baraa (real name Mahmud Muhammad Usman) was born to an ethnic Ebira Islamic scholar from Kogi state (the present authors’ sources add that his mother is Fulani106), though he grew up in Maiduguri.107 He received secondary education and attempted to join the National Defence Academy but was rejected, to his frustration.108 He was soon drawn to Mohammed Yusuf and became a member of the amniyat or internal security forces of Yusuf’s movement.109 When Ansaru split over disagreements with Yusuf’s successor, Abubakar Shekau, in 2011-2012, Abu Baraa reportedly joined the network.110 He received training from AQIM in Libya in the 2010s alongside other Ansaru associates111 and would eventually become its emir after Khalid al-Barnawi, an early AQIM-linked jihadi and one of the faction’s founding members, was arrested in 2016 in Kogi.112

(Source: Bayo Onanuga/X)

Baraa was highly mobile within Nigeria, narrowly avoiding escape on at least one occasion.113 By 2022, if not earlier, he had apparently fallen out with Mala Abba and the Ansaru group in Birnin Gwari, as previously noted. Despite this rift, he apparently continued to hold sway over a faction of the jihadi community in Ebiraland in Kogi (detailed later in this study) and networks in southwestern Nigeria, with cells in locations such as Shaki in northern Oyo, Owo in northern Ondo, and various parts of Kogi state alongside major northern cities such as Kaduna, Zaria, and Kano.114 The network was involved in criminal activities such as bank robberies, kidnapping for ransom of both Nigerians and expatriates (including attacks on highways in the southwest),115 and may have been responsible for a gruesome massacre at a Catholic church in Owo in 2022 that was widely attributed to ISWAP but never claimed.116 aw

Indeed, in notable contrast to ISWAP and the Ansaru network operating in Birnin Gwari, Abu Baraa’s network never claimed any attack. Per one security source, he “eschew[ed] publicity,” preferring instead to raise funds for future operations through criminal activity and radicalizing new recruits into his cause.117 His network was technologically savvy and better educated than the rank-and-file of other Nigerian jihadi groups. He and his associates were early users of Telegram in Nigeria to conduct outreach and radicalization aimed primarily at university students.118 Despite principally comprising ethnic Ebira and Yorùbá,ax his network may have conducted outreach to some Fulani communities in the southwest that felt aggrieved by growing anti-pastoralist sentiment and harassment from Amotekun, a vigilante group created by southwestern governors in 2020 amid growing farmer-herder conflict.ay This is in notable contrast to the Ansaru of Mala Abba, which effectively aligned with Hausa communities against Fulani in the course of its intervention in the banditry crisis in Birnin Gwari.119

It is unclear how much direct oversight Abu Baraa exercised over his network, as he was reportedly not based in Kogi in recent years.120 As noted previously, the exact relationship between Mahmuda and Abu Baraa remains somewhat unclear to the authors, although they clearly knew each other and had been in contact before their arrests.121 Interestingly, despite being in Ansaru, Abu Baraa may have also played an indirect role in the growth of Sadiku’s JAS network in Kaduna, as several of Sadiku’s future lieutenants undertook Islamic studies at one point or another in the Kinkinau neighborhood of Kaduna state where Abu Baraa was based for a time and expressed familiarity with him, indicating that he may have helped play a role in radicalizing them.az

The authors’ interviews in the first half of 2025, shortly before his arrest, indicated that Abu Baraa was likely in the process of attempting to reconcile the different factions of Ansaru that had previously split and possibly conducting outreach to other jihadi cells in north central Nigeria.122 In this sense, the authors may concur at least in part with Simón and Foucher’s assessment that at the time of his arrest, Abu Baraa was “attempting to coordinate among Nigeria’s many jihadi factions and their Sahelian counterparts … among whom he enjoyed considerable respect.”123 Indeed, it may have been because Abu Baraa was consistently relocating to mediate between factions that he proved vulnerable to arrest.124

Lakurawa

“Lakurawa” is the colloquial term used by Nigerians to describe Sahelian militants who first appeared in the borderlands of northwest Nigeria in 2017-2018 (although the militants were earlier known as Lakuruje).ba Notably, it was traditional authorities in Sokoto state who first invited Lakurawa to provide protection to their communities from Zamfara-based bandits.125 The militants soon overstayed their welcome, however, clashing with some of the community leaders who first welcomed them and enforcing a harsh interpretation of sharia law that alienated much of the rural population.126 These militants have been highly active once again in the northwest since late 2024, generating significant media attention within Nigeria and internationally127 and prompting the Nigerian military to reframe its operations in the northwest, at least partially, as an offensive against the group.128

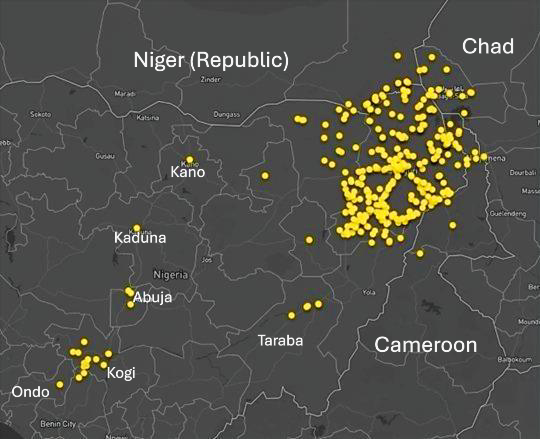

The identity and affiliation of Lakurawa have been much debated among analysts. As described in a separate article by the first author, some of the confusion stems from the fact that the original Lakurawa group seems to have been quite heterogenous, comprising both Malian and Nigerien militants who came from different Fulani clans and had differing modus operandi.129 Furthermore, given the fluidity of jihadi alliances and fracturing in the Sahel, some of the original members of Lakurawa may have been affiliated with JNIM in 2017-2018 but are now affiliated with ISSP.130 Nonetheless, the present evidence points to the majority of so-called Lakurawa activity, particularly in Sokoto and northern Kebbi states, as being the work of ISSP militants. Among other evidence, United Nations experts have identified ISSP activity in these states as well as an ISWAP logistics hub in Sokoto reportedly used to facilitate coordination between the two Islamic State affiliates.131 As Héni Nsaibia demonstrates in a recent ACLED report on the southward expansion of Sahelian jihadis, ISSP has been pushing steadily from southern Niger into northwestern Nigeria in 2024-2025, and the ingress points of Lakurawa into Nigeria (e.g., Tangaza and Gudu LGAs of Sokoto) correspond with known ISSP bases on the Nigerien side of the border.132 (See Figure 8 below from the ACLED report.) At the same time, some evidence suggests that JNIM may also be intermittently operating in parts of Kebbi and Niger states (see the previous section on Mahmuda’s group for more) under the guise of “Lakurawa,” as at least one former Nigerian jihadi has been approached for collaboration by self-described al-Qa`ida-affiliated Lakurawa members.133 Nevertheless, for the purposes of this study, most of the authors’ analysis focuses on the activity of Lakurawa in Sokoto and parts of Kebbi state where, the authors can reasonably assume, so-called Lakurawa activity is the work of ISSP.

Despite their growing notoriety within Nigeria, the militants work hard to maintain operational security, never telling communities whether they belong to ISSP, JNIM, or any other faction, likely because the confusion surrounding their identity benefits them.135 The composition of Lakurawa therefore remains rather unclear, and analysts and journalists have floated several names of potential leaders since late 2024.136 A July 2025 article by Mondafrique, citing unnamed sources, said that one Namata Korsinga, a Nigerien Fulani from the commune of Abala Filingue in Tillaberi, is the leader of the Lakurawa subgroup while his younger brother, Saadu Korsinga, is the leader of the ISSP Katiba that has been active in western Niger in recent months.137 A colleague the authors consulted had also heard reports of one Kousanga (likely an alternative spelling of Korsinga) in Lakurawa, but as a deputy of the group beneath a more senior ISSP commander, and noted that sources gave conflicting names of the overall Lakurawa leader.138 The authors had heard from their contacts in Sokoto earlier in 2025 that leaders of Lakurawa included one Namata—lending weight to Mondafrique’s reporting—as well as Abu Muslim, Abu Anas, Manu (possibly a former ISWAP associate, according to some of the authors’ sources), and Abdulkarim.139 A very rough picture of the group’s leadership thus may be starting to emerge, but much work remains to be done to clarify the leadership as well as overall size and composition of the group.

2024-2025: A New Modus Operandi?

While Lakurawa is not a new group, its operations since late 2024 have differed from its initial incursions in notable ways that point to a more aggressive campaign of expansion. This could be explained by several factors, including ISSP’s desire to break out of the Liptako-Gourma tri-border region of the Sahel (where it has long been contained) and establish a corridor to Benin via northwestern Nigeria as part of its competition with its JNIM rivals.140 bb The militants may also be taking advantage of the breakdown in relations between Nigeria and Niger following the July 2023 coup in Niamey that has hindered cross-border cooperation.141 In these efforts, the group’s approach to local Nigerian communities varies from protection to hostility.

Lakurawa is currently operating across a much wider swath of northwestern Nigeria than it did previously. Whereas the group previously operated almost exclusively in Tangaza and Gudu LGAs in Sokoto state along the border with Niger, in late 2024, it began operating farther within the interior of Sokoto, particularly in a stretch of sparse forest across Binji and Silame LGAs that extends to within 20 miles of the Sokoto state capital.142 More worrying still, the group has been active in neighboring Kebbi state, particularly in Augi, Arewa Dandi, and Argungu LGAs down to Bunza, Dandi (Kamba), and Bagudo LGAs (which share a border with Benin).143 Wherever they operate, according to locals, “they tend to move through various villages during the day without much interaction … They do not ask for directions, suggesting they might already know the area.”144

The group appears to have consolidated influence in the border regions of Sokoto where it first appeared in the late 2010s: In Gudu LGA and Tangaza LGA, respondents said the group has closed down public schools145 and replaced existing imams by appointing their own their own (either from the community, or by appointing members of the group to preach themselves).146 bc The group prevents civil servants and security personnel from entering the area147 (with an exception for health professionals, at least in the case of Balle in Gudu LGA148). As one source in Tangaza explained, “In so far as you have anything that identifies your relations with the government like ID cards, [a certain] vehicle plate number, they will seize it and even threaten to kill you.”149 Lakurawa is also still, as it was in 2018, fighting bandits selectively in a manner that allows it to present itself as a defender of vulnerable Muslim communities. The group is also adjudicating land disputes and conflicts between farmers and herders, supplanting the role of traditional authorities.150

Unfortunately, this approach seems effective to some extent. Various respondents spoke more favorably of Lakurawa than bandits, particularly in the northernmost parts of Sokoto state. One resident in Tangaza recounted how his friend had been kidnapped by bandits and freed by Lakurawa in October 2024 when the latter attacked a bandits’ camp. As he recalled: “They asked him for the contact of his people, and they called us to inform that the man is in safe hands. The following day, they arranged for his returning back home … and he was dropped off.”151 These sorts of experiences can cumulatively contribute to building a degree of popular support. As a community leader Tangaza LGA frankly remarked, “The reality is whoever saved you from kidnappers, you will never forget him. This is the true picture of what transpired: the Lakurawa saved us from the bandits when the government could not do anything.”152

But at the same time, the group is once again attempting to impose its extreme interpretations of the sharia that many residents find excessive and harsh. In rural parts of Augi LGA of Kebbi state, many shops have ceased selling cigarettes (which are often but not exclusively consumed by bandits, providing some income to local vendors) out of fear of incurring Lakurawa’s wrath,153 while elsewhere in the northwest, Lakurawa has flogged residents for having haircuts deemed “un-Islamic.”154 Even the foreignness of the militants poses some basic stumbling blocks to their expansion, at least in certain communities in the region, as one of the authors’ interviewees in Sokoto bluntly observed:155

Q: Have you ever listened to them preach?

A: Yes, they preach in French, Fulfulde, Zabarmanci, and Buzanci, but not in Hausa. Those are their native languages.

Q: Do people here understand those languages?

A: No. They just form a circle and listen without truly understanding.

The group has also shown less compunction about attacking and stealing from civilians whom it deems to have disobeyed its injunctions. The authors’ interviewsbd suggest a geographic correlation to Lakurawa’s relative hostility toward local communities, with respondents in Kebbi state and the interior of Sokoto state recounting more abuse at the hands of the group than those in northern Sokoto (e.g., Tangaza and Gudu LGAs) during fieldwork in early 2025.be This could be a function of different commanders within the group adopting different strategies in their respective areas, but it is also likely rooted in the fact that the group has longer-standing ties with communities in northern Sokoto and thus less need to enforce compliance violently. In Kebbi and central Sokoto, by contrast, Lakurawa has stolen cattle from communities under the auspices of zakat collection156 and attacked villages that raise vigilante groups,157 indicating that its violence is largely aimed at asserting dominance over populations in the frontiers of its new expansion.

As a result of these more recent and aggressive tactics, many respondents in Kebbi and Sokoto distinguished between the “original” Lakurawa and what they perceive as a different, current manifestation of the group. As one source in Kebbi claimed, “the first set claimed to be preaching Islam, while the second set engages in violent attacks on people’s lives and livestock.”158 Yet other respondents went further and speculated that Lakurawa are in fact bandits using the jihadi label as a guise for their operations. One claimed: “These recent people I believe are a distortion of the Lakurawa we know. We believe [they are] the bandits that were raided by security forces that changed to become the new Lakurawa, since the main Lakurawa have forced them out of kidnapping and cattle rustling.”159 Another source noted differences in the appearance and ethnicity of the present Lakurawa and those of the first militants who emerged in 2018:

The Lakurawa we knew wore turbans. This new group also wears turbans but has facial markings, and the turbanning is very different. They appeared to be a mix of Fulani and Tuaregs before, but now even Hausa and Zabarma are among them. The old Lakurawa used to pay for what they took from shops. If their cattle destroyed your crops, they would come, assess the damage, and pay you. This new group does not pay; they simply seize everything.160

The authors do not agree with the assessment that Lakurawa are merely bandits by another name, nor is there strong evidence to suggest that the current Lakurawa are a fundamentally different set of militants than the first group (although the heterogeneity of the militants circa 2017-2018 and limited insight into the group’s current membership make it difficult to assess with any confidence). Nonetheless, the aforementioned quotes underscore the challenges that Lakurawa faces in upholding the reputation for defending communities from banditry that it has tried to cultivate in the northwest, as discussed in the following section.bf

Facilitators or Impediments to Expansion? The Interplay between Bandits and Jihadis

The preceding sections have provided brief overviews of the key jihadi groups that are operating in western Nigeria at present. In this section, the authors elaborate on the first of two factors that they identify as being critical to facilitating jihadi operations in western Nigeria, which they dub the banditry “Goldilocks effect.”

Understanding Bandits, Jihadis, and their Interplay

The ongoing banditry crisis in northern Nigeria constitutes an immensely fragmented and complex conflict that has not received as much analytical or scholarly attention as the Boko Haram conflict in the northeast. For the purposes of this study, it suffices to emphasize two key characteristics of contemporary banditry in northern Nigeria.

First, bandit leadership and hierarchies are decentralized and fluid—but banditry is hardly egalitarian, and not all bandits are equal in their power or influence. There is no precise or reliable estimate of the total number of bandits operating in northwestern Nigeria—which could be complicated by the fact that some fighters are “part-time” bandits161—although officials have often given a (likely excessive) estimate of up to 30,000 armed bandits.162 The number of gangs is similarly difficult to gauge, although there are undoubtedly dozens and possibly several hundred,163 depending on how one distinguishes one gang from another. This is difficult, as underscored by a recent study co-authored by one of the present authors that argues:

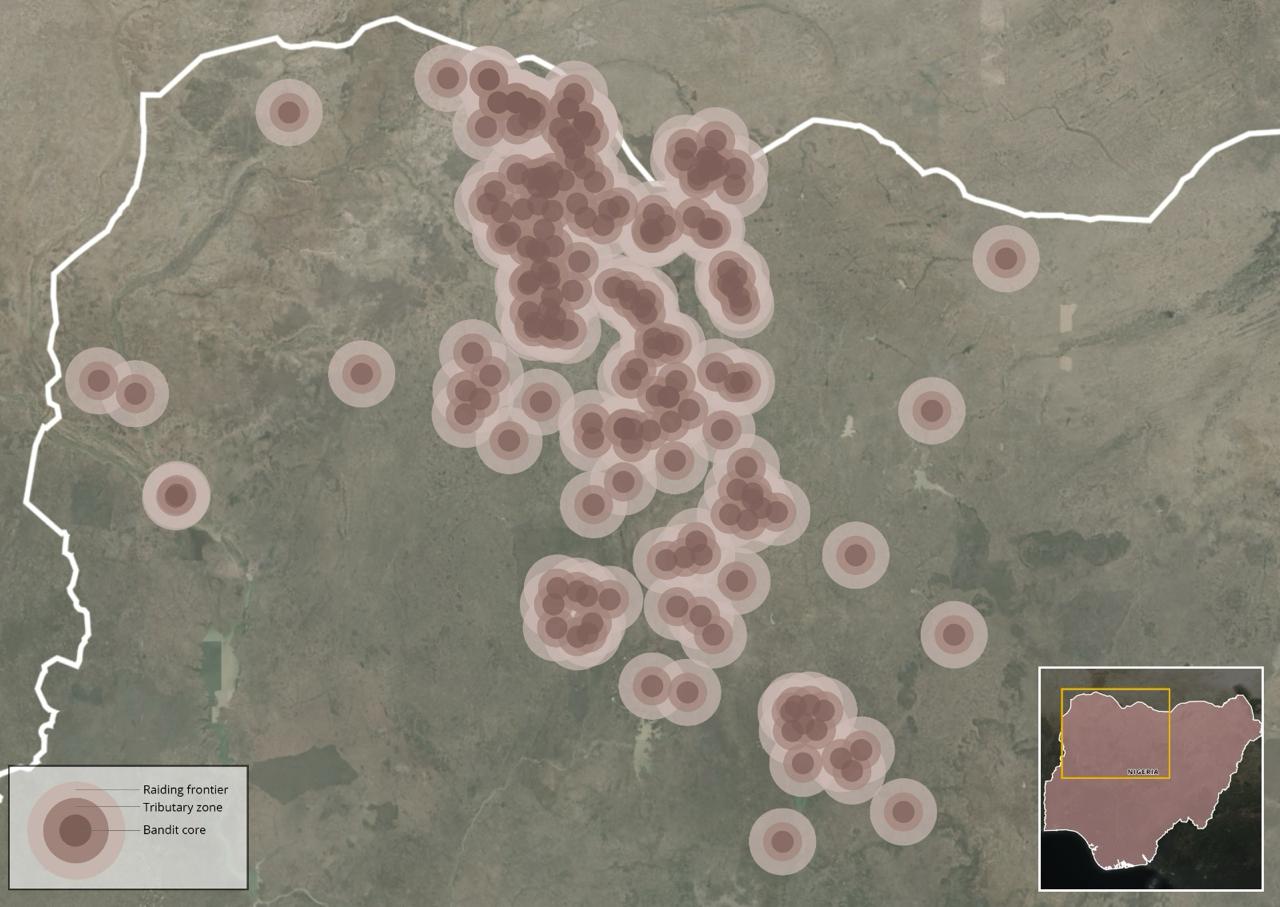

Unlike armies or insurgencies with formalised chains of command, banditry operates through a delicate interplay of autonomy and allegiance, resulting in a centrifugal dynamic of radical fragmentation and a centripetal logic based on specific forms of ‘capital’ that hold currency in bandit society… A major bandit leader may occupy a camp with a group of loyal bandits no bigger than 50. But spread in his area of influence are minor kachallas [commanders] with their own groups, who are independent in their actions but nonetheless pledge allegiance to the oga [top bandit].164

For example, that study shows that in one LGA alone in eastern Sokoto state bordering Zamfara (Sabon Birni LGA), there are 30 different notable bandit commanders, yet all of them have traditionally been loyal to Bello Turji, one of the most infamous bandits in the northwest.165

The fluid organizational nature of banditry—coupled with the previously described challenges of conducting field research in any conflict zone—make mapping bandit influence and power more difficult than mapping even jihadi areas of attack or control in Nigeria, given that the latter operate more like classic insurgents and (contra bandits) often claim their attacks in one way or another. Consequently, this section of the present study employs some admittedly vague or subjective labels regarding the relative influence of bandits, as such traits are quite difficult to quantify.

However, the authors’ assessments reflect the views of the dozens of respondents whom they interviewed in the banditry-afflicted regions of the northwest, many of whom articulated a clear consensus that certain bandits are highly powerful (one might call them warlords166) and exercise influence over many smaller but still deadly gang leaders. These respondents also noted that certain regions and states are bandit “strongholds.” Specifically, the epicenter of the banditry crisis has long been in Zamfara state,167 which respondents also stated constitutes the base for most of the warlords in the region. In the states neighboring Zamfara (Katsina, Sokoto, Kaduna, Niger, and Kebbi), those LGAs that are adjacent to the boundaries with Zamfara are typically more impacted by banditry than those LGAs that are further removed, which itself represents an emerging political geography of banditry that can be divided into overlapping and shifting zones of bandit “cores,” “tribute zones,” and “raiding territories.”168 (See Figure 9.)

The second aspect of banditry that is relevant here, as detailed in a previous study in this publication, is that banditry presents opportunities and challenges for jihadis who seek to expand into western Nigeria.169 On the one hand, those parts of Nigeria suffering from banditry present advantages to jihadis that are seeking to expand or relocate. For starters, banditry erodes what little state presence previously existed in rural Nigeria, contributing to the inability of security forces to establish a permanent and widespread presence across rural communities and thereby creating what might be dubbed “illicitly governed enclaves.”170 In such enclaves, there are ample opportunities for jihadis to make a profit, typically by partnering with bandits in activities such as kidnapping for ransom and cattle rustling or by selling weapons to gangs or instructing them in IED making (for a price). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, bandits offer jihadis a foil: In their effort to earn popular support for their insurgencies from Muslim communities, jihadis present themselves as a contrast to—and, indeed, protection from—those bandits who indiscriminately raid and terrorize communities across Nigeria’s northwest without any ideological pretense. Whether in the case of Ansaru in Kaduna, Mahmuda in Niger and Kwara, or Lakurawa in Sokoto, time and again jihadis have presented themselves as security providers to desperate rural communitiesbg that the state has been unable to protect. In other words, the presence of banditry not only provides jihadis with financial opportunities, but also the opportunity to develop new constituencies within the broader population.

On the other hand, Nigerian banditry presents an immensely complex set of conflict dynamics that jihadis often struggle to navigate. Jihadis have struggled to coopt bandits due to an array of factors, including a lack of ideological and strategic alignment between bandits and jihadis; the bandits’ reluctance to surrender their autonomy to jihadis who hail from a different part of Nigeria (and are typically of different ethnicitiesbh); friction over the behavior of bandits, such as drug and alcohol use and even bandit hairstyles that jihadis consider vices; and the loose organization and frequent fracturing of bandit gangs.171 In short, bandits make for difficult partners and may quickly become enemies.

Moreover, there is an obvious tension between the different benefits that jihadis seek to accrue from operating in areas affected by banditry. Jihadis seek to profit from banditry, which necessitates some degree of cooperation, while at the same time they position themselves as superior to bandits and indeed as a defense against them. In other words, to garner both sets of benefits from banditry, jihadis would need to both cooperate and fight with bandits.

Examples of Jihadi-Bandit Relations

Sadiku’s JAS cell struck what was likely the most effective balance of profiting from banditry while still presenting itself as a superior alternative and security guarantor to local communities, particularly the Gwari villages of Chikun LGA in Kaduna. Upon his relocation to the northwest, Sadiku developed a close relationship with Dogo Gide among several other bandits. Underpinning this arrangement, at least initially, was Sadiku’s flexible approach to the bandits. As one of his former associates described it:

Sadiku brought his own soldiers and weapons from Shekau and said to the bandits, “You have your own space, we have our own space. This is our camp, and you can have your own. You won’t be under us, we won’t be under you.” So, they agreed to stay in the same area but operate independently.172

Sadiku was careful not to preach jihadi ideology too much to the bandits (although Dogo Gide expressed some interest),173 and he cautioned his fighters not to be overly judgmental of the bandits and their un-Islamic ways, noting that in Kaduna, “[the situation] was different from Sambisa” where the jihadi project was “more advanced.”174

Yet even Sadiku’s lax attitude toward the bandits could not sustain this modus vivendi forever, as a bandit that is an ally one day might become an enemy the next. Dogo Gide and Sadiku fell out in late 2024 and began clashing, reportedly because Sadiku was “arrogant [and] demands respect” from the bandits, according to a former associate of Sadiku’s.175 “But to the bandits, Sadiku is an immigrant,” this source continued. “The forest belongs to them, so how can someone from Borno come and take over the forest?”176