From 2013 through 2014, the Islamic State recruited tens of thousands of fighters from all corners of the globe to fight in Syria and Iraq. The vast majority of these fighters were new to jihad, having never taken up arms before. Yet, the Islamic State also drew a select group of recruits for whom Syria would not be their first jihad. This article examines 219 such fighters who reported prior jihadi experience outside of Syria. It finds that the profiles reported by Islamic State veteran jihadis with experience in Libya and Afghanistan, the two top locations from which Islamic State fighters reported prior experience, are substantially different. Veterans of jihad in Libya are the result of localized dynamics while veterans of jihad in Afghanistan represent a more internationalized jihadi contingent.

From 2013 through 2014, the Islamic State recruited tens of thousands of fighters from all corners of the globe to fight in Syria.1 In 2016, NBC News obtained and reported on a cache of Islamic State personnel files it received from a Syrian man who said he stole a flash drive containing the files from a senior commander in the group.2 These files, which NBC shared with the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), provided extensive insights into the Islamic State’s recruitment of foreign fighters.

One of these key insights was that the vast majority of the Islamic State’s foreign recruits were new to armed jihad. (Islamic State fighters had been asked to report their previous jihadi experience.) An analysis of the Islamic State personnel records by CTC’s Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler found that the percentage of fighters who reported prior jihadi experience was “relatively low” at 9.6% and that about a quarter of those who reported previous jihadi experience reported it only in Syria.3

In their analysis of the Islamic State files, Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler note that the top location where Islamic State fighters reported experience outside of Syria was Libya, with about 70 cases, followed by Afghanistan, with about 60 cases.4 Beyond these two countries, Yemen, Pakistan, Mali, Somalia, Chechnya, Dagestan, and Gaza were reported, each with 20 or fewer fighters. The initial report, however, did not provide an analysis of the ways in which veterans of jihad in these different regions vary, noting, “it is beyond the scope of this initial report to provide a detailed and comprehensive breakdown of the variety groups that the Islamic State’s new recruits had access to at this time.”5

This article provides an initial examination of the Islamic State recruits who reported prior jihadi experience in Libya and Afghanistan—the two top locations where recruits reported prior jihadi experience. It finds that veterans of jihad in Libya tend to have gained their experience as a result of localized conflict dynamics while veterans of jihad in Afghanistan represent a more internationalized veteran-jihadi population.

The findings reported in this article are based on a similar and likely overlapping, though not necessarily identical, set of Islamic State personnel files as those examined by the CTC. The records examined here consist of 3,577 entry records provided to the author by Nate Rosenblatt, an independent Middle East/North Africa consultant and doctoral candidate at Oxford University, which formed the basis for the New America reports All Jihad is Local: What ISIS’ Files Tell Us About its Fighters and All Jihad is Local Volume II: ISIS in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.6

Who Are the Islamic State’s Experienced Recruits?

In line with the findings of Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler, the files examined here suggest a fighting force that was relatively new to armed jihad. Among the 3,577 total fighters, 347, or 9.7%, reported some kind of prior jihadi experience. Of these 347 fighters, 219 fighters reported prior jihadi experience that could be identified as having been outside of Syria. These fighters constituted 6.1% of the overall sample.a

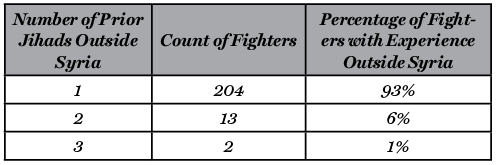

These veteran Islamic State fighters rarely fought in more than one field of jihad beyond Syria itself. Ninety-three percent of veteran jihadis (with experience outside of Syria) reported only one location outside of Syria where they had prior jihadi experience. Thirteen fighters—or 6% of the fighters who reported jihadi experience outside Syria—reported prior jihadi experience in two locations. Five of the 13 fighters who reported two locations of prior jihadi experience reported those locations as Pakistan and Afghanistan, which may be best understood as a single linked field of jihad given the rather porous Afghan-Pakistan border through which al-Qa`ida and the Taliban are known to cross frequently. Another two fighters reported locations that are geographically linked: Gaza and Egypt, and India and Pakistan. Only two veteran jihadis reported experience in three or more prior jihads outside of Syria.

Table 1: Number of Prior Jihads Listed, Excluding Syria

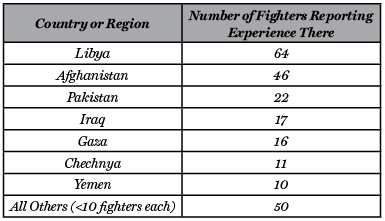

The files examined in this article also provide a similar set of findings regarding the locations where the Islamic State veteran fighters reported prior jihad. Libya was the top-cited location of experience outside of Syria with 64 fighters reporting experience there, followed by Afghanistan where 46 fighters reported experience. As with Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler’s data, there is a steep drop-off after these two with the next highest-cited location being Pakistan, with 22 fighters reporting experience there.

Table 2: Locations of Jihadi Experience Outside of Sham

The rest of this article examines in detail the set of Islamic State fighters who reported prior jihadi experience in Libya and Afghanistan in order to identify differences between the two contingents of veterans.

Veterans of Jihad in Libya

By far, the most common location outside of Syria where Islamic State veteran jihadis gained their experience was Libya, where 64 fighters reported prior jihadi experience. Islamic State recruits who reported being veterans of jihad in Libya were the product of highly localized dynamics tied to conflicts in Libya. The Islamic State recruited from a Libyan population that had mobilized to fight in the Arab Spring uprising and the subsequent civil war.

Most veterans of jihad in Libya were Libyans themselves. Veterans of the Libyan jihad reported residing in four countries, but 54 of the 64 fighters (84%) who reported prior jihadi experience in Libya reported residing in Libya.

This is unsurprising. Since the Arab Spring reached Libya and escalated into an armed rebellion in February 2011, Libya has been ripped apart by conflict: first, the uprising against Muammar Qaddafi and then, a civil war between competitors for power. Around 300,000 Libyans joined militias during the uprising against Qaddafi.7 These numbers are reflected in the Libyan contingent of Islamic State recruits, more than half of whom reported prior jihadi experience with the vast majority reporting such experience only in Libya.8

Beyond Libya, the next most common site of residence of veterans of the Libyan jihad was Tunisia, which borders Libya to the west, where seven fighters (11%) reported residing. This likely reflects the close connections between Tunisia and Libya, which contributed to Tunisia being the largest source of foreign fighters who traveled to fight in Libya itself, a flow that existed from the beginning of the Libyan uprising and built upon the nexus between Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia and Ansar al-Sharia in Libya.9 An examination of the Islamic State personnel files shows that many Tunisians passed through Libya on their way to fight in Syria. For example, 8.7% of the Tunisians in the Islamic State files examined here reported being recommended to the group by Nouredine Chouchane, who ran a training camp in Libya, and Libya was by far the most common destination to which Tunisian fighters reported traveling.10

Another two fighters reported residing in Egypt, which borders Libya to the east. Only one fighter reported being a veteran of jihad in Libya and residing in a country that didn’t border Libya. That fighter reported residence in Bosnia.

Another sign that veterans of jihad in Libya among Islamic State recruits gained their experience as a result of localized conflicts within Libya rather than an internationalized jihadist mobilization is that only one reported experience outside of Libya (or Syria), with reported experience in Libya, Egypt, and Gaza.

In addition, veterans of jihad in Libya are relatively young compared to other Islamic State recruits. The median year of birth for a veteran of jihad in Libya was 1991. That is two years younger than the median Islamic State fighter among the full set of 3,577 records, who was born in 1989, and four years younger than the median veteran recruit who reported experience in a location other than Syria—born in 1987.

The youthfulness of veterans of jihad in Libya points to two conclusions. First, these veterans are quite similar to the overall population of Libyan Islamic State recruits, which was also relatively young with a median birth year of 1992.11 Second, it means that veterans of jihad in Libya among Islamic State recruits are too young for their reported experience to be a reference to earlier rounds of armed jihadi rebellion in Libya. For example, the median veteran of jihad in Libya recruited by the Islamic State would have been at most seven years old when the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group’s armed rebellion in Libya’s east was decisively crushed in 1998.12

Veterans of Jihad in Afghanistan

Afghanistan was the second most cited location where Islamic State recruits reported jihadi experience outside of Syria. Forty-six fighters reported prior jihadi experience in Afghanistan. In contrast to fighters who reported experience in Libya, Islamic State fighters who reported jihadi experience in Afghanistan represent an internationalized jihadi contingent and their jihadi experience cannot be reduced to an outgrowth of conflict in Afghanistan and its mobilization of Afghans.

Veterans of jihad in Afghanistan reported residing in 16 different countries—four times as many as veterans of jihad in Libya reported—suggesting a highly internationalized contingent.

Unlike veterans of jihad in Libya, the majority of whom reported residing in Libya, only three veterans of jihad in Afghanistan reported their residence as being Afghanistan when filling out the Islamic State entry form. Moreover, none of these three fighters appear to be Afghans themselves. One reports being an Iranian citizen; another reports being a Tunisian citizen; and the final individual did not report a citizenship but used a kunya—or nom de guerre—ending in al-Kurdi, meaning the Kurd.

Instead, 43 fighters—93% of those reporting experience in Afghanistan—reported residing outside of Afghanistan. The countries these fighters reported residing in can be broken into three categories: those reporting residing in countries that border Afghanistan, those reporting residing in Central Asian countries that do not border Afghanistan, and those from outside the region.

Eighteen of the 43 fighters residing outside of Afghanistan came from bordering countries. These included Iran (8), Pakistan (7), Tajikistan (2), and Uzbekistan (1). Another two reported residence in Central Asian countries that do not directly border Afghanistan—one each in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Together, these suggest that part of the more internationalized nature of veterans of Afghanistan’s jihad may be a product of regional foreign-fighter flows from bordering countries and Central Asia.

However, 23 fighters—half of the total set of veterans reporting experience in Afghanistan—report residing in a country outside of the region. These fighters report residence in nine separate countries as follows: Saudi Arabia (9), Azerbaijan (4), Egypt (2), Jordan (1), Kosovo (1), Kuwait (1), Libya (1), Turkey (3), Ukraine (1).

Another sign that Islamic State recruits reporting jihadi experience in Afghanistan represent a more internationalized contingent is that nine of these veterans report prior jihadi experience in more than one country other than Syria. That accounts for more than half of the 15 fighters who reported experience in more than one country other than Syria. In five of these cases, the two countries are Afghanistan and Pakistan, which may simply be a single jihadi front. However, two fighters reported experience in Chechnya as well as Afghanistan—one of whom also reported experience in Pakistan. A third fighter who reported experience in Afghanistan reported experience in Bosnia, and a fourth reported experience in Yemen.

Veterans of jihad in Afghanistan were also far older than veterans of jihad in Libya. Their median year of birth was 1983. That makes the median veteran of jihad in Afghanistan among Islamic State recruits eight years older than the median veteran of jihad in Libya, six years older than the median Islamic State fighter overall, and four years older than the median veteran of a jihad outside of Syria. The older age of many of the Islamic State fighters reporting experience in Afghanistan suggests that they may well be more fully integrated into international jihadi currents.

Conclusion

The differences between Islamic State veterans who reported prior jihadi experience in Libya and those who reported such experience in Afghanistan are not surprising. Afghanistan has been a site of jihad for decades throughout which time it attracted thousands of men from around the world whereas Libya only recently became a site of open jihadi armed struggle. However, the differences illustrate the need to distinguish between distinct populations even when examining a specific variable—for example, whether an Islamic State recruit reports prior jihadi experience. This suggests a need for further disaggregation of data by geography when examining captured or leaked terrorist records. CTC

David Sterman is a senior policy analyst at New America’s International Security Program. He is also the co-author of All Jihad is Local Volume II: ISIS in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, an examination of Islamic State personnel records from North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula at the subnational level.

Substantive Notes

[a] One hundred and twenty-one fighters reported experience only in Syria, Sham, or with a militant group active in Syria. Seven fighters reported prior jihadi experience, but it was unclear where they developed such experience.

Citations

[1] “Foreign Fighters: An Updated Assessment of the Flow of Foreign Fighters Into Syria and Iraq,” Soufan Group, December 2015.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Nate Rosenblatt, “All Jihad is Local: What ISIS’ Files Tell Us About its Fighters,” New America, July 20, 2016; David Sterman and Nate Rosenblatt, “All Jihad is Local Volume II: ISIS in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula,” New America, April 5, 2018.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Fears over Islamists within Libyan rebel ranks,” BBC, August 11, 2011.

Skip to content

Skip to content