According to news reports citing several unnamed senior U.S. officials, the leader of the Islamic State’s Somali branch quietly became the global head of the Islamic State last year. This is far from confirmed. But it is clear the group is growing as a threat. Over the last three years, the Islamic State’s Somalia Province has grown increasingly international, sending money across two continents and recruiting around the globe. There are also growing linkages between the group and international terrorist plots, raising the possibility that Islamic State-Somalia may be seeking to follow in the footsteps of Islamic State Khorasan in going global. Not only was the group linked to a May 2024 shooting at the Israeli embassy in Sweden, but in February 2024, a Somali-American man was arrested for his prior involvement in Islamic State-Somalia and encouraging others online to conduct acts of terror in New York. Despite being relatively limited inside Somalia compared to its rival in al-Qa`ida’s al-Shabaab, the Islamic State’s Somalia Province is punching well above its weight internationally and has become one of the Islamic State’s most important global branches.

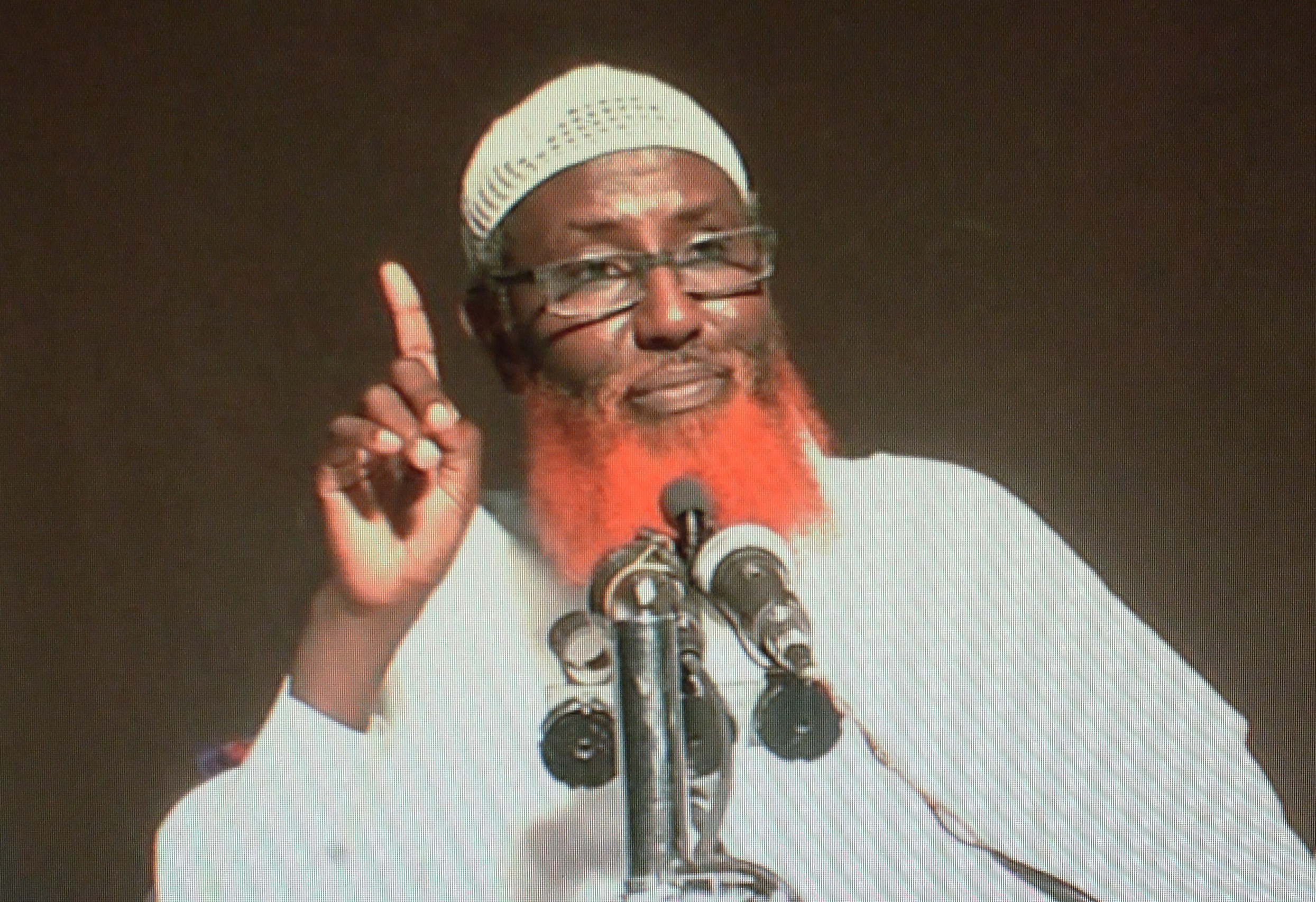

In late May 2024, a U.S. airstrike reportedly targeted the global leader of the Islamic State in a surprising place: northern Somalia.1 NBC News, citing three U.S. officials, reported that the man targeted was the founder of the Islamic State’s Somalia Province, Abdulqadir Mumin, and that he was acting as the Islamic State’s so-called caliph.2 Though this latter claim remains wholly unconfirmed as of the time of publishing, U.S. officials have nevertheless stated that Islamic State-Somalia is a “growing threat”3 and that the United States is “watching ISIS-Somalia closely.”4 Mumin is assessed by a Somali security source and local Somali media to have survived the strike against him.5

The authors are skeptical of the notion that the Islamic State’s central shura council appointed Mumin as caliph.c But the concerns expressed by U.S. officials over Islamic State-Somalia’s growing capabilities, ambitions, and reach are entirely warranted. Over the last three years, the branch has grown in importance for the Islamic State’s global operations. From sending money from across much of East Africa to the Middle East and beyond, to broader international recruiting, and growing linkages to international attack plotting, the Islamic State’s small franchise based in the mountains of northern Somalia is proving it can punch above its weight. This transformation is not dissimilar to those seen with other Islamic State groups, namely the Islamic State’s Khorasan Province (ISK), and illustrates how the Islamic State’s weakened central leadership in the Middle East can rely on select global ‘provinces’ to carry out tasks previously reserved for the so-called ‘core cadre’ in Iraq and Syria.

This article examines this transformation and details just how international the Islamic State’s Somalia Province has become, with it now acting as one of the most important global wings of the Islamic State as a whole. Starting with a brief background on the emergence of the Islamic State-Somalia, the article then turns to outlining the significance of Islamic State-Somalia to the Islamic State’s global leadership, including discussing its key role in financing the Islamic State’s African operations and beyond before examining its growing international recruitment efforts and how its ranks are increasingly made up of foreign fighters. Lastly, the article looks at the growing linkages between the group and international attack plotting, raising the possibility that Islamic State-Somalia may be seeking to follow in the footsteps of ISK by going global.

Background

Emergence of the Islamic State in Somalia

The Islamic State first appeared in Somalia in the second half of 2015 in two separate locations of Somalia when pro-Islamic State commanders within al-Qa`ida-affiliated al-Shabaab defected from that group and pledged allegiance to the Islamic State’s then-caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.6 The first to defect—in September 2015—were well-known al-Shabaab commanders in southern Somalia, including Bashir Abu Numan, Hussein Abdi Gedi, and Mohammad Makkawi Ibrahim. They were quickly wiped out by al-Shabaab.7 Some Somali Islamic State cells survived in Mogadishu and now constitute the most militant branch within Islamic State-Somalia.8

The second, and most important, Islamic State-loyal group to emerge in Somalia was a faction led by Mumin in Somalia’s semi-autonomous northern region of Puntland. Mumin, once a prominent ideologue within al-Shabaab, defected and joined the Islamic State with a few dozen of his men in October 2015.9

Remaining operationally dormant for a year, Islamic State-Somalia quickly shot to international attention when in October 2016 it briefly captured and occupied the northern port town of Qandala.10 Thereafter, in 2017, the group was made an official ‘province’ of the Islamic State.11 Since then, its military prospects have shrunk due to a combination of military pressure from Somalia (both Puntland State and the Federal Government of Somalia in Mogadishu), the United States, and al-Shabaab. However, Islamic State-Somalia continues to maintain strongholds in Puntland’s Al-Madow Mountains (sporadically clashing with al-Shabaab’s fighters posted nearby12) and attack cells in Mogadishu.13 Other Islamic State cells have periodically popped up elsewhere, such as in the central city of Beledweyn in 2018 or near Kenya in 2019,14 though the Al-Madow Mountains and Mogadishu remain Islamic State-Somalia’s core areas of operation.

Though Mumin’s exact current role inside Islamic State-Somalia remains somewhat unclear, it is unanimously believed that he is one of its two top leaders. For example, the United Nations’ ISIL and Al-Qa’ida Sanctions Monitoring Team has long described Mumin as the emir of Islamic State-Somalia, with the United States’ National Counterterrorism Center stating the same.15 But in 2023, the U.S. Treasury Department described Mumin as just the emir of the Al-Karrar office, a regional administrative hub of the Islamic State,a with Abdirahman Fahiye Isse Mohamud described as the current emir of Islamic State-Somalia.16 The aforementioned United Nations Monitoring Team now follows a similar tack of describing Mumin as both the emir of Islamic State-Somalia and of Al-Karrar, with Abdirahman Fahiye likewise the deputy emir of both entities.17 Despite the opaqueness of Mumin’s exact role within Islamic State-Somalia itself, he nevertheless continues to be an important figure within the larger organization (and possibly for the Islamic State globally).

(Simon Maina/AFP via Getty Images)

Global Significance: Leadership and Finance

Increasing Importance within the Islamic State

As noted, several unnamed U.S. officials told NBC News in June that Mumin is the global leader of the Islamic State. An alternative theory has also surfaced. On June 18, three days after the NBC News story was published, Voice of America noted there were “a flood of rumors emanating from Somalia that the IS emir, Abu Hafs al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, traveled from Syria or Iraq and then through Yemen to the semi-autonomous Puntland region of Somalia in country’s northeast.” The outlet quoted a senior U.S. defense official stating that top Islamic State leaders “view Africa as a place where they should invest, where they are more permissive and able to operate better and more freely, and they want to expand … so, they did bring the caliph to that region.” The official’s words suggest the caliph relocated, but is not Mumin.18

The idea that either Mumin himself is Abu Hafs or that Abu Hafs was moved from the Middle East to northern Somalia seems far-fetched to the authors. For the Islamic State, how would the Islamic State’s ideologues validate the necessary Qurayshi lineage of Mumin, a necessary religious condition for any potential caliph to be taken seriously by the group’s support base?b Why would the Islamic State’s central shura council think Somalia would be a safer place for its caliph? And out of all of its global leaders, from Africa’s Sahel to the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, why would Mumin be specifically chosen? Even with these questions, it is possible that Mumin is instead the emir of the Islamic State’s General Directorate of Provinces (GDP), the Islamic State’s administrative structure that oversees and manages its so-called ‘provinces’ around the world,19 a point made in this publication by Austin Doctor and Gina Ligon.20 Such a position is arguably more immediately relevant to the Islamic State’s operations than the caliph, as the emir of the GDP is directly responsible for managing all of the ‘provinces’ and is thus more active in day-to-day activities. Having Mumin as emir of the GDP would make him effectively the operational leader of the Islamic State,21 but would avoid the sticky ideological questions around the religious legitimacy of a non-Qurayshi Arab as caliph. Without knowing or examining the exact intelligence from which the United States is reportedly basing its assessment, however, it is impossible to know if this alternative hypothesis is indeed viable. According to a U.N. report, some member states have also expressed skepticism over the assertion that Mumin is Abu Hafs, but it is also unclear if these disagreements are politically motivated or actually based on disagreements in analysis.22

Even with the exact role of Mumin being contested, his organization is certainly taking on more global importance for the Islamic State. The Islamic State’s Al-Karrar regional office has been based in Somalia since at least late 2018, just one of many such ‘offices’ under the GDP that function as regional command structures organized to help coordinate all of the Islamic State’s activities and operations in a specific area.23 Al-Karrar’s purview includes all of eastern, central, and southern Africa, where it helps oversee and manage all of the Islamic State’s official ‘provinces,’ networks, and support activities.24 These Islamic State branches routinely communicate with Al-Karrar, addressing current statuses, needs, and goals. As an example, leaked and recovered Islamic State documents have detailed Islamic State groups in both the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Mozambique sending routine status updates to Al-Karrar, while Al-Karrar has in turn “facilitated the movements of trainers, tactical strategists, and financial support” to both groups.25 A degree of command-and-control also exists between Al-Karrar and its constituent groups and networks.

As another example, the United Nations previously reported that the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province (ISCAP) in the DRC has received “guidance from Al-Karrar to recruit, expand the group [ISCAP], and develop strategic attacks.”26 Somali security sources have stated that Mumin, via Al-Karrar, is also in communication with other Islamic State groups on the continent.27 Though the exact command Mumin exerts on the other groups outside of Al-Karrar’s purview is unclear, Mumin’s role within the GDP implies some degree of command.28 For much of the African continent, however, it is quite evident that Islamic State-Somalia’s Al-Karrar office is the preeminent leadership body of the Islamic State with Mumin as one of the Islamic State’s most important leaders on the continent and likely beyond, regardless if he is actually caliph or not.

Involvement in Global Islamic State Financing

Beyond providing leadership, Al-Karrar is also one of the Islamic State’s preeminent financial apparatuses around the world. Islamic State-Somalia itself generates the money that Al-Karrar uses to fund Islamic State networks across the world. As documented by the U.S. Treasury in July 2023, “in the first half of 2022, ISIS-Somalia generated nearly $2 million by collecting extortion payments from local businesses, related imports, livestock, and agriculture.”29 According to the U.S. Treasury, Islamic State-Somalia generated at least $2.5 million in 2021,30 meaning that Islamic State-Somalia and thus Al-Karrar had close to $5 million dollars (if not more as the U.S. Treasury 2022 estimate only accounts for half of that year) to utilize to fund Islamic State activities for those years. In early 2023, a U.N. report stated that Islamic State-Somalia was generating at least $100,000 a month from its extortion activities in both northern Somalia and Mogadishu, though this was likely an undercount of its total available funding from all of its revenue streams.31 This number was expanded in July 2024, as another U.N. report suggested that Islamic State-Somalia makes around $360,000 a month, primarily from extortion and illicit taxation. If true, this would account for at least $4.3 million in annual income for the group, a significant increase from previous estimates.32

The significance of Al-Karrar’s funding—and Islamic State-Somalia’s fundraising—is made evident by the extent to which it has funded Islamic State activity across eastern, central, and southern Africa. For instance, according to a June 2023 study by the Bridgeway Foundation, Al-Karrar facilitated the movement of almost $400,000 between Somalia and nodes in South Africa from 2019 to September 2021.33 On the orders of Al-Karrar, at least $200,000 of this money was then transferred further down the line to Islamic State operatives across East Africa, including financial nodes for ISCAP and the Islamic State’s Mozambique Province.34 The network detailed by Bridgeway, however, was just one such financial network and thus represents only a conservative fraction of the total money moved by Islamic State-Somalia’s Al-Karrar and transferred to other Islamic State nodes. The true total is likely significantly higher, as other networks have been established since the specific network detailed by Bridgeway was shut down in September 2021.35

Furthermore, this funding has expanded beyond just Africa, underlining the global importance of Islamic State-Somalia and its Al-Karrar office. For example, in leaked Islamic State letters dated late 2018, Islamic State leaders in the Middle East ordered Al-Karrar to send funds to Islamic State nodes in both Turkey and Yemen via the Islamic State’s Al-Faruq and Umm al-Qura regional offices, respectively.36 Further, in the network uncovered by Bridgeway, some of the money from Al-Karrar was shown to have also been moved to Islamic State operatives in the United Arab Emirates.37 The United Nations additionally found in early 2023 that Al-Karrar was sending $25,000 a month in cryptocurrency to ISK.38 It is evident from this additional international funding that the Islamic State’s central leaders look to Islamic State-Somalia and Al-Karrar as a dependable source to fund its global activities. In fact, a July 2024 U.N. report explicitly states that Al-Karrar’s funding “is the top revenue source for the organization overall.”39

All of the aforementioned financial activities were controlled and directed by Bilal al-Sudani. Originally a Sudanese member of al-Shabaab, al-Sudani (real name: Suhayl Salim Abd el-Rahman) was first designated as a terrorist by the U.S. government in 2012 for his role in facilitating the movement of people and funds for al-Shabaab.40 Independent analysts believe that when al-Sudani defected to Islamic State-Somalia in late 2015, he brought most of his contacts with him, effectively enabling him to rise up the ranks and quickly become one of the foremost leaders within Islamic State-Somalia.41 As the leader of Al-Karrar, it was al-Sudani who oversaw the aforementioned funding of various Islamic State groups across Africa and around the world. It was al-Sudani’s importance to the Islamic State that resulted in him being specifically targeted by U.S. special operations forces in early 2023.42

Speaking after the raid that killed al-Sudani, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin emphasized the Sudanese jihadi’s importance to the Islamic State writ large when he said that al-Sudani was “responsible for fostering the growing presence of ISIS in Africa and for funding the group’s operations worldwide, including in Afghanistan.”43 For instance, some of the money that al-Sudani oversaw being transferred to Afghanistan assisted ISK’s deadly suicide bombing at Kabul Airport’s Abbey Gate during the hasty U.S. withdrawal from the country in August 2021.44 Given al-Sudani’s outsized importance for the Islamic State not only in Africa but also around the world, it is very likely that al-Sudani was also considered by the Islamic State itself to be one of its key global leaders, thereby highlighting the growing global nature of Islamic State-Somalia and its importance to the Islamic State as a whole. It was noteworthy in this regard that al-Sudani guided the Islamic State’s West Africa Province in Nigeria on issues of governance, according to the U.S. Treasury, further indicating his high status and authority within the Islamic State beyond Somalia.45

Al-Sudani’s prominent global role speaks to how the Islamic State has become reliant on the constituent bodies of the GDP, the so-called regional ‘offices,’ to undertake cross-provincial actions once reserved for the core cadre in the Middle East.46 As noted by researcher Aaron Zelin, Al-Karrar’s integration with other ‘offices’ of the Islamic State, namely Al-Sadiq in Afghanistan, Umm al-Qura in Yemen, and Al-Faruq in Turkey, and possibly Al-Furqan in Nigeria, also point to growing organizational integration within the Islamic State’s total global network.47

International Recruitment

In addition to taking on more of an outsized role within the Islamic State’s broader global leadership and operations, the Islamic State’s Somali Province has an increasingly international composition. Whereas previous reports once characterized Islamic State-Somalia as a group primarily consisting of Somalis,48 the group’s demographics today suggest that Somalis may now be outnumbered by foreign fighters. An increasingly wider international composition gives the group greater opportunities to plot international terror.

To be clear, even from its beginning Islamic State-Somalia has always contained foreign fighters. Specifically, it has always touted members from Ethiopia,49 d Djibouti,50 and the Somali diaspora from both the West51 and from East Africa, primarily Kenya.52 Somali officials have long noted the presence of Yemenis among Islamic State-Somalia’s ranks.53 Islamic State-Somalia’s ties to Yemeni arms smugglers and the illicit economy inside Yemen likely helped it to attract fighters from the Arab country.54 Other early Islamic State-Somalia foreign fighters included at least two American citizens and at least one Pakistani national, two of whom were former members of al-Shabaab.55

In southern Somalia and northern Kenya, Islamic State-Somalia also once benefited from the short-lived Jabha East Africa, also known as Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (ISSKTU), a small grouping of pro-Islamic State members within al-Shabaab from the aforementioned countries that was active for several months in 2016.56 Jabha East Africa offered the Islamic State a first opportunity to expand in sub-Saharan Africa. However, it remained small and became operationally defunct nearly as quickly as it emerged.e Though Islamic State-Somalia benefited in the mid- to late 2010s from such international combatants, they remained a minority compared to the Somalis within Islamic State-Somalia’s ranks, many of whom were from Mumin’s Ali Saleebaan sub-clan of the wider Somali Darod clan family in northern Puntland.57

Islamic State-Somalia also sought to capitalize on these early foreign fighters and mobilize supporters to incite attacks in the West and elsewhere. On December 25, 2017, the Islamic State released a video titled “Hunt Them Down, O Monotheists,” encouraging violence against Christmas and New Year’s gatherings and presenting high-profile targets such as in London and New York, and prominent religious figures such as Pope Francis.58 The production features three militants, with one fighter speaking in accented English and two others from Ethiopia, calling upon Muslims, specifically those in East Africa, to join the Islamic State cause. Like Islamic State Central and ISK, Islamic State-Somalia sometimes includes foreign fighters as role models for those of similar ethnolinguistic and national backgrounds. One example was a January 2019 Islamic State-Somalia video eulogizing several foreign fighters who had traveled to join the group and fought in its ranks, including a purported Canadian doctor identified as Yusuf al-Majerteni. The majority of the militants shown were from Ethiopia, Djibouti, and various Somali clans.59 One segment featured al-Majerteni encouraging foreigners and doctors to join Islamic State-Somalia. The third installment of the Islamic State’s “Answering the Call” series, published in February 2020, featured Islamic State-Somalia jihadis training, as well as a long profile of an Ethiopian foreign fighter who had tried and failed to join the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria and later traveled to fight and die with Islamic State-Somalia. This was not the only video released by the group to entice Ethiopians to join the franchise.60 More recently, in July 2022, Islamic State-Somalia published a 25-minute video titled “Upon the Path of the Conquerors” in Amharic with Arabic subtitles.61 Amharic is spoken in parts of Somalia as well as Eritrea, and is the official language of Ethiopia.

Fast forward to today, however, and it is apparent that Islamic State-Somalia’s ranks are increasingly international, with foreign fighters possibly outnumbering its Somali members (though to be clear, it is still recruiting Somalis). According to a Somali security source, Ethiopians are today the single largest demographic within the group, accounting for at least 200 people out of an estimated 500-700 members total.62 f In addition to ethnic Somali-Ethiopians, the group has also recruited many ethnic Oromo and Amhara fighters into its ranks, while one senior leader in the group, Abu Farah al-Habashi, is himself allegedly an ethnic Tigrayan, according to the same Somali security source.63 The recruitment of Ethiopians across their country’s diverse ethnic landscape presents further unique security challenges, as all three aforementioned regions, Oromia, Amhara, and Tigray, are in the throes of their own conflicts.

Farther south, in sub-equatorial Africa, Islamic State-Somalia has also increasingly recruited Tanzanians. Recent defectors from Islamic State-Somalia stated the majority of new combatants being trained in the group’s training camps were Ethiopians and Tanzanians.64 The same defectors also noted significant numbers of Ugandans training with the group as well.65 Importantly, Kenyan authorities arrested three Kenyan nationals in April 2023 attempting to travel to Somalia to join Islamic State-Somalia.66 The three were previously wanted for terrorism offenses inside Kenya on behalf of al-Shabaab.67 Furthermore, in late 2023, authorities in eastern DRC arrested two Congolese nationals who were being recruited into Islamic State-Somalia.68 A recent Tanzanian detainee held by Puntland Security Forces has also stated the presence of Malawians inside Islamic State-Somalia, though this is so far uncorroborated elsewhere.69

Some recruits have traveled from farther away in Africa. There are a growing number of North Africans within the ranks of Islamic State-Somalia. For example, at least a dozen Moroccan nationals have been detained over the last year in Puntland for their membership in Islamic State-Somalia.70 According to the aforementioned recent defectors from Islamic State-Somalia, there are a large number of Tunisians within the group, though exact totals remain unknown.71

There are a significant number of Sudanese fighters in Islamic State-Somalia, with their number among the first foreign demographic to defect from al-Shabaab. One case in point was Sudanese national Mohamed Makkawi Ibrahim, a former al-Qa`ida in Sudan member who originally joined al-Shabaab before becoming an early convert to the Islamic State inside Somalia and an early so-called ‘martyr’ for the group.72 Another case in point was Bilal al-Sudani, who was killed alongside 10 other Sudanese Islamic State-Somalia fighters in early 2023.73 A third case in point is Mohamad Ibrahim Daha, a senior Islamic State-Somalia commander who was captured by Puntland security in June 2023.74 Puntland officials have since continued to periodically report the capture of Sudanese Islamic State-Somalia fighters. According to a Somali security source, the Sudanese represent one of the largest cohorts within Islamic State-Somalia.75 The high total of Sudanese is likely related to Islamic State misfortunes elsewhere. For instance, Sudanese were once among the largest foreign components of the Islamic State’s Libya Province at its height between 2014-2016, with estimates that at least 150 Sudanese nationals fought for that Islamic State wing.76 With that Islamic State branch today being all but defunct, it is likely that Somalia now offers the most attractive and/or easiest destination of choice for those Sudanese wishing to join the Islamic State. Given the large numbers of Tunisians that were also present with the Islamic State in Libya, this too could explain their reported presence in northern Somalia.77

At least two Syrians joined Islamic State-Somalia, though it is unclear if either had prior ties to the Islamic State in their home country.78 Israeli police and the Shin Bet also announced last month that they arrested a teen in Haifa before he could journey to join Islamic State-Somalia after being in contact with the group, underlining the broad geographic scope of Islamic State-Somalia’s online recruitment efforts.79 Unlike before, however, wherein the Islamic State showcased foreign fighters in Somalia through its media released from its Somali Province, this recent surge in foreign numbers to its Somali wing has not been touted by the Islamic State’s central media at all. Rather than a specific strategic decision to not have Islamic State-Somalia film such fighters, this dearth in recent propaganda is likely more related to the decline in Islamic State propaganda videos across the board over the last almost two years.80

Nevertheless, Islamic State-Somalia’s increased international recruitment presents several potential implications. First, with rumors emerging that Somalia may attempt some form of negotiations with al-Shabaab (though denied by Somalia’s government),81 any such negotiations could create disquiet among al-Shabaab’s more radical foreign recruits (or even local recruits) who do not support such political endeavors and thus could bolster the ranks of Islamic State-Somalia by defecting. With increased manpower, this could help Islamic State-Somalia spread more geographically in Somalia. Second, any foreign jihadi fighters defecting to the group could gain instruction within Islamic State-Somalia’s training camps and then return to their home countries to conduct acts of terror either on their own or as directed by the group. Tanzania especially faces a threat from any such returning foreign fighters because there is not only a Tanzanian contingent inside Islamic State-Somalia but there are also large Tanzanian components in the Islamic State’s Mozambique and Central Africa Provinces.82 g Likewise, the large numbers of Ethiopians and Sudanese within the ranks of Islamic State-Somalia also pose a significant security challenge in that any potential returning cell threatens to exacerbate and complicate already intense conflicts in those countries.

Growing Linkages to International Terror

The international composition of Islamic State-Somalia’s fighters provides it with opportunities to plot international terror, for example by sending foreign fighters to carry out attacks back in their home countries or having those foreign fighters provide online coaching to extremists back in their home countries to carry out attacks. As will be outlined below, there are indicators that Islamic State-Somalia is eyeing attacks outside Somalia.

Islamic State-Somalia’s international ambitions were noticeable relatively early in its existence. In late 2018, just three years after Islamic State-Somalia’s foundation, a 20-year-old Somali national identified as Omar Mohsin Ibrahim (known as Anas Khalil during his time fighting for the Islamic State in Libya) was arrested in the southern Italian city of Bari for plotting to bomb churches, particularly in Vatican City.83 He was allegedly in contact with members of the Islamic State in Somalia, specifically “one of its operational cells.”84 The plan reportedly was to make rudimentary improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and place them in various churches around Italy, beginning with the bombing of St. Peter’s Basilica.85 According to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Somalia, the “Vatican plot represents the first instance in which ISIL elements in Somalia were directly linked to an attempted terrorist attack outside the country.”86 However, according to the same U.N. panel, “intercepted communications indicate that ‘Anas Khalil’ devised the plan to plant a bomb in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome on 25 December, Christmas Day, of his own accord and was not directly tasked by ISIL operatives outside the country.”87 Nevertheless, stored in Omar Mohsin Ibrahim’s phone contacts were entries corresponding with several key leaders of Islamic State-Somalia ostensibly to seek guidance and support in this effort (though ultimately the exact nature of any conversations was unclear).88 The stored phone contacts included Abdullahi Mohamud Yusuf, or Al-Majerteni (different from the other ‘al-Majerteni’ mentioned above), one of the top leaders in Islamic State-Somalia prior to his arrest earlier in 2018.89 h So although it is probable that Khalil’s Vatican plot was not directly ordered by the Islamic State’s leaders in Somalia, it seems likely that its leadership, particularly Al-Majerteni, was in the know given the likely communication between the plotter and the group.

Several years later, there were renewed links between the group and global terror plotting. In March 2024, Swedish authorities arrested four individuals in the Stockholm suburb of Tyresö for preparing “terrorism offenses.”90 A few weeks later, a Somali imam in the same city was arrested as part of the same attack plotting.91 Further investigations into this cell revealed links to Islamic State-Somalia,92 though it remains unclear at the time of publication if Islamic State-Somalia directly oversaw or tasked the cell with the attack plot. While the exact nature of what the cell was in the midst of planning is opaque, Swedish authorities stated this cell was also linked to a May 2024 shooting at the Israeli embassy in Sweden and was integrally connected to criminal gangs in Tyresö and its surroundings and actively seeking to recruit from them.93 The Swedish cell was also reportedly in contact with and guided other pro-Islamic State individuals in Europe, specifically an individual in Spain who sought to target Jewish individuals.94 i

It is noteworthy that Abdulqadir Mumin himself once lived in Gothenburg, Sweden, in the early 2000s, where he was the imam at a local mosque and investigated there for extremism.95 j Islamic State financial receipts reviewed by the Bridgeway Foundation also documented significant transfers from Sweden to East Africa between 2017 and 2018—by members of the Somali diaspora—which were also directed by the Islamic State nodes in both Kenya and the Middle East.96 The Swedish case illustrates the potential for Islamic State-Somalia to use diaspora communities in the West to carry out attacks, much as al-Qa`ida used British Pakistanis for attack plotting in the United Kingdom in the 2000s and ISK has used Central Asians in Europe in recent years.

The ISK Playbook

There is concern that Islamic State-Somalia could follow ISK’s trajectory. In recent years and months, other Islamic State branches such as those in Pakistan and the Philippines have followed ISK’s lead in establishing in-house propaganda apparatuses, outside of Islamic State Central’s media infrastructure, and using these to build support, recruit, fundraise, and call for attacks inside their regions of operations and abroad using diaspora communities.97 It is worth noting that ISK’s official branch propaganda outlet, Al-Azaim Foundation for Media Production (hereby shortened to just Al-Azaim), was operated externally to the branch by supporters before being taken under official control in 2021 when it was designated as the central outlet.

For Islamic State-Somalia, there too exists a supporting propaganda organ called al-Hijrateyn that publishes a high volume of video, audio, and print content across numerous social media sites and messaging applications in Amharic, Somali, Oromo, and Swahili that resembles Al-Azaim prior to its formal integration into ISK and subsequent expansion.98 Moreover, Al-Azaim and al-Hijrateyn have deepened the formal Islamic State-Somalia-ISK relationship with al-Hijrateyn’s recent admission into the global pro-Islamic State media outlet umbrella coalition Fursan al-Tarjuma, which Al-Azaim was heavily involved with creating and making outreach to other branch-level and unofficial supporter outlets.99 Within this umbrella, it is possible that administrators from Al-Azaim can cooperate with those from al-Hijrateyn to improve on its media operations and formalize potential joint media campaigns.

Before undertaking and guiding numerous attack plots in the West, ISK began its strategy of regionalization and internationalization by building up its propaganda apparatus. It prepared the information space by globalizing its narratives and messaging, taking aim at an expanded range of neighboring countries and others further abroad.100 Given the growing relationship between Islamic State-Somalia’s media outlet and ISK’s Al-Azaim media outlet—a core component of ISK’s transformation—and current international plotting trends within Islamic State-Somalia, it should be anticipated that Islamic State-Somalia could emulate ISK’s strategy and change its doctrine to prioritize attacking foreign interests and nationals in East Africa, develop its external operations capabilities for attacks abroad, and ramp up efforts to incite and guide supporters—particularly Somalis and speakers of Amharic, Oromo, and Swahili from the surrounding region living in the West—to violence.101 ISK has incited such violence through its Central Asian media content and has used Central Asian diaspora members, Tajiks in particular, to plot and undertake terrorist attacks abroad.102

As Islamic State-Somalia grows more international in character, more countries could be at risk, particularly in Western diaspora communities and across East Africa. If Islamic State-Somalia evolves similarly to ISK, it could theoretically utilize radicalized Somali (or other) diaspora communities to strike in the West if it chooses that path. Especially vulnerable are Somali communities in the United States and Canada, who have been the targets of jihadi recruitment campaigns in the past.103

The potential threat to the United States was underlined when a Somali-American man was arrested in February 2024 for his involvement in Islamic State-Somalia and for encouraging others online to conduct acts of terror in New York City.104 According to investigators, the American, identified as Harafa Hussein Abdi, originally traveled to Somalia and joined Islamic State-Somalia shortly after its formation in late 2015.105 There, he received military training and became part of the group’s media wing, helping it to produce propaganda videos and engage with supporters online.106 U.S. prosecutors have also reported that Abdi appeared in one such propaganda video where he called on others to make hijrah (emigrate for jihad) to Somalia and explicitly encouraged Islamic State supporters in the United States to undertake shooting and bombing attacks in New York City.107 Abdi left Islamic State-Somalia in 2017 and was initially arrested by an unnamed East African country where he had reportedly resided since leaving the group.108 Abdi’s case highlights not only the potential danger Islamic State-Somalia poses in encouraging terror plots abroad, but also showcases just how long the group has possessed such ambition.

As outlined above, Islamic State-Somalia has links to diaspora communities in Europe, particularly in Scandinavia, where it could also plot attacks. In the near term, it is probably East African countries that are at most risk of Islamic State-Somalia terrorism. With its increased East African recruitment, particularly of Tanzanians, it is increasingly possible that Islamic State-Somalia provides these East Africans with the necessary training and experience to return to their home countries and perpetrate acts of terror.

Conclusion

Once a relatively small group based in the foothills of Somalia’s northern mountains and relegated second fiddle inside the East African country by al-Qa`ida’s al-Shabaab, the Islamic State’s Somalia Province has significantly grown in importance for the Islamic State not only in Africa but increasingly for global Islamic State activities. While still relatively militarily contained inside Somalia itself, its ability to generate millions of dollars and command Islamic State activities across much of Africa via its Al-Karrar office has caught the attention of both the Islamic State’s central leadership and counterterrorism officials around the world.

Unconfirmed reports that global Islamic State leadership now rests with Islamic State-Somalia come as the group is already expanding its international recruitment capabilities and pools and potentially looking to engage in international terrorism plotting via diaspora Somali communities. All of this points to Islamic State-Somalia growing on the global stage, somewhat mimicking the international growth of other Islamic State ‘provinces,’ namely the Islamic State’s Khorasan Province. As the Islamic State continues to flounder in its historical strongholds of Iraq and Syria,k the growing of regional ‘provinces’ such as Islamic State-Somalia into global actors offers the so-called ‘core’ group in the Middle East additional opportunities to retain its funding and leadership capabilities and further extend its brand of jihad in the name of “remaining and expanding.” CTC

Caleb Weiss is the Bridgeway Foundation’s Defections Program Lead for Uganda, which is focused on promoting defections from the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province, and an editor of FDD’s Long War Journal, concentrating on jihadism and political violence across the African continent. X: @caleb_weiss7

Lucas Webber is a researcher focused on global security issues and violent non-state actors. He is co-founder/editor at militantwire.com, Senior Threat Intelligence analyst at Tech Against Terrorism, and Research Fellow at The Soufan Center. X: @LucasADWebber

© 2024 Caleb Weiss, Lucas Webber

Substantive Notes

[a] By late 2018, the Islamic State had restructured its organization to include the General Directorate of Provinces (GDP) and its subordinate regional offices around the world. These regional offices act as coordination hubs, helping to administer the Islamic State’s disparate provinces on behalf of the wider GDP. In addition to the Al-Karrar office in Somalia, there also exists: Ard al-Mubarakah, responsible for Iraq and Syria; Al-Furqan, which oversees Africa’s Lake Chad Basin, North Africa, and the Sahel; Al-Sadiq, overseeing South and Southeast Asia; Umm al-Qura, which is responsible for Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf states; Dhu al-Nurayn, which focuses on Egypt and Sudan (though this office may now be defunct); and Al-Faruq, which looks after Turkey, the Caucasus region, and Europe. Another office, Al-Anfal, also once previously managed the Islamic State’s activities in North Africa, but this has since been subsumed under the Al-Furqan office. See “Letter dated 11 July 2022 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, July 15, 2022, p. 5.

[b] There is technically a way for the Islamic State to claim that Mumin is indeed a descendant of the Quraysh. For example, the larger Somali Darod clan to which Mumin belongs claims descent from Abdirahman bin Isma’il al-Jabarti, himself an alleged descendent of Aqil ibn Abi Talib, a cousin of the Prophet Mohammad and member of the Qurayshi Banu Hashim tribe. This alleged lineage, however, is rooted more in Somali culture and mythos rather than legitimate genealogy. As such, this proposed lineage still presents a challenge for the Islamic State, which previously had to deal with persistent rumors that one of its previous caliphs, Abu Ibrahim, was actually ethnic Turkmen and thus not of the Qurayshi lineage. On the legendary origins of the Darod, see I.M Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2003), p. 5 and Mohamed Abdirizak Dol, The Origin of the Darod Tribe in Somalia (2019), p. 4.

[c] The Islamic State believes, as do many mainstream Muslims, that Islamic rulers must be of Qurayshi lineage, as stipulated by a Hadith [saying] of Prophet Mohammad as recorded by Sahih al-Bukhari. In appropriating this belief, the Islamic State has hoped to legitimize its state-building project. For the Hadith in question, see Sahih al-Bukhari, 3501.

[d] This includes the former deputy emir of Islamic State-Somalia Abu Zubair al-Habashi, who was killed at some point in 2020. This also includes Abu al-Bara al-Amani, who led Islamic State-Somalia’s combat operations until his death in January 2023. See “Letter dated 28 September 2020 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, September 28, 2020, p. 19 and “News: Puntland State Police announce killing of Ethiopian-born Daesh militia leader,” Addis Standard, January 13, 2023.

[e] Jabha East Africa was founded by a Kenyan member of al-Shabaab who then recruited a small cadre of other al-Shabaab foreign fighters from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The new group subsequently pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in early 2016. A few weeks later, it conducted an attack against African Union forces in southern Somalia before conducting a series of other small operations in both Kenya and Tanzania throughout 2016. By early 2017, its networks were largely rolled up in Tanzania, and some of those within the former Jabha East Africa went to Islamic State franchises elsewhere, particularly Mozambique. The group thus served as the Islamic State’s first attempt at expansion into deep sub-Saharan Africa, though it was never formally recognized as an official ‘province.’ Instead, it acted more as an informal arm of Islamic State-Somalia. See Brenda Mugeci Githing’u and Tore Refslund Hamming, “The Arc of Jihad: The Ecosystem of Militancy in East, Central and Southern Africa,” International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, November 2021, pp. 18-20.

[f] The total number of combatants within Islamic State-Somalia is highly contested, but it likely falls somewhere around or within that range. This number also represents a significant increase from earlier manpower estimates, further highlighting the group’s expansion efforts. To note, the most recent United Nations estimate puts Islamic State-Somalia at around 300-500 combatants. See “Letter dated 19 July 2024 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, July 22, 2024, p. 10.

[g] Tanzania historically has faced recruitment and low-level terrorism incidents related to al-Qa`ida (largely via al-Shabaab) in the years since al-Qa`ida’s 1998 suicide bombing on the U.S. embassy in Dar es Salaam. In the early 2010s, al-Shabaab recruited a significant number of Tanzanians and set up rudimentary training camps on Tanzanian soil. By the mid- to late 2010s, then Tanzanian President John Magufuli effectively suppressed or co-opted most of al-Shabaab’s Tanzanian networks, including Ansaar Muslim Youth Centre, Muslim Renewal, and al-Muhajiroun. Though al-Shabaab still benefits from some Tanzanian recruitment today, by most indications the networks that survived Magufuli’s purges and political co-option have largely switched allegiances to the Islamic State, as seen with the former Jabha East Africa networks. As such, Tanzanians are today primarily being recruited into the Islamic State’s various affiliates across East and Central Africa. The concern is these recruits could return to launch attacks in their home countries. For more on the background of al-Qa`ida’s/al-Shabaab’s efforts and connections that set the groundwork for today’s jihadism threat in Tanzania, see Andre LeSage, “The Rising Terrorist Threat in Tanzania: Domestic Islamist Militancy and Regional Threats,” Institute for National Strategic Studies, September 2014 and Jay Radzinski and Daniel Nisman, “Key signs that Al Qaeda’s Islamic extremism is moving into southern Africa,” Christian Science Monitor, March 12, 2013. For more on how Tanzania, particularly under late President Magufuli, repressed these previous jihadi efforts, see Peter Bofin, “Tanzania and the Political Containment of Terror,” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, Hudson Institute, January 24, 2022.

[h] Al-Majerteni is a veteran of the Islamic State in both Iraq and Libya and has traveled extensively around the Middle East and Africa working on behalf of the Islamic State. While stationed in Libya, he was in charge of its office for recruitment of foreigners. Al-Majerteni was later detained inside Somaliland from 2018-2021, with his current status and whereabouts unclear. See “Letter dated 1 November 2019 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992),” United Nations Security Council, November 1, 2019, pp. 19-20.

[i] The shooting on the Israeli embassy in Sweden and the plot to kill Jewish people in Spain also comes in a post-October 7th environment in which many jihadi groups are attempting to exploit collective anger over Israel’s actions in Gaza.

[j] While Mumin was living in the United Kingdom following his stint in Sweden, he was also linked to the future perpetrator of the May 2013 Lee Rigby murder in London. See Colin Freeman, “British extremist preacher linked to Lee Rigby killer emerges as head of Islamic State in Somalia,” Telegraph, April 29, 2016.

[k] To caveat, recent indications and attack trends suggest that the Islamic State is currently on the upswing in both Iraq and Syria, and particularly so in the latter country. See Charles Lister, “CENTCOM says ISIS is reconstituting in Syria and Iraq, but the reality is even worse,” Middle East Institute, July 17, 2024.

Citations

[1] Courtney Kube, “Global leader of ISIS targeted and possibly killed in U.S. airstrike,” NBC News, June 15, 2024.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Carla Babb, Harun Maruf, and Jeff Seldin, “Islamic State in Somalia poses growing threat, US officials say,” Voice of America, June 18, 2024.

[4] Jeff Seldin, “US watching #ISIS-#Somalia closely, per @USAfricaCommand’s Gen. Michael Langley …,” X, June 27, 2024.

[5] Author (Weiss) interview, Somali security source, Kampala, Uganda, July 2024; “Source: ISIS leader Abdulqadir Mumin survives U.S. airstrike in Somalia,” Hiraan Online, July 10, 2024.

[6] Jason Warner and Caleb Weiss, “A Legitimate Challenger? Assessing the Rivalry between al-Shabaab and the Islamic State in Somalia,” CTC Sentinel 10:10 (2017).

[7] Ibid.; Caleb Weiss, “Jihadi archives: Islamic State’s eulogy of Sudanese jihadist Mohamad Makkawi Ibrahim,” FDD’s Long War Journal, July 5, 2024.

[8] Based on author’s (Weiss) own compilation of Islamic State-Somalia attack data.

[9] Warner and Weiss.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Caleb Weiss, “Reigniting the Rivalry: The Islamic State in Somalia vs. al-Shabaab,” CTC Sentinel 12:4 (2019); Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State describes intense campaign against Shabaab in northern Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, February 2, 2024.

[13] Based on author’s (Weiss) own compilation of Islamic State-Somalia attack data.

[14] Caleb Weiss, “Shabaab kills pro-Islamic State commander,” FDD’s Long War Journal, January 14, 2019.

[15] See, for example, “Letter dated 23 January 2024 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, January 29, 2024, p. 8; “ISIS-Somalia,” National Counterterrorism Center, as of September 2022.

[16] Caleb Weiss, “U.S. designates Islamic State financier in Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, July 29, 2023.

[17] “Letter dated 19 July 2024 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, July 22, 2024, p. 10.

[18] Babb, Maruf, and Seldin.

[19] Tore Hamming, “The General Directorate of Provinces: Managing the Islamic State’s Global Network,” CTC Sentinel 16:7 (2023).

[20] Austin Doctor and Gina Ligon, “The Death of an Islamic State Global Leader in Africa?” CTC Sentinel 17:7 (2024).

[21] Ibid.

[22] “Letter dated 19 July 2024 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee …,” p. 12.

[23] Caleb Weiss, Ryan O’Farrell, Tara Candland, and Laren Poole, “Fatal Transaction: The Funding Behind the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province,” GWU Program on Extremism, June 2023.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Letter dated 21 January 2021 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, February 3, 2021, p. 11; “Letter dated 15 July 2021 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, pp. 9, 80; “Letter dated 11 July 2022 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, July 15, 2022, p. 9.

[27] Author (Weiss) interview, Somali security source, Kampala, Uganda, July 2024.

[28] Author (Weiss) interview, Somali security source, Kampala, Uganda, July 2024.

[29] “Treasury Designates Senior ISIS-Somalia Financier,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 27, 2023.

[30] Ibid.

[31] “Letter dated 13 February 2023 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, February 13, 2023, p. 8.

[32] “Letter dated 19 July 2024 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee …,” p. 10.

[33] Weiss, O’Farrell, Candland, and Poole.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Hamming.

[37] Weiss, O’Farrell, Candland, and Poole.

[38] “Letter dated 13 February 2023 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee …,” p. 8.

[39] “Letter dated 19 July 2024 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee …,” p. 20.

[40] “Somalia Designations,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 5, 2012; “Background Press Call by Senior Administration Officials on a Successful Counterterrorism Operation in Somalia,” The White House, January 26, 2023.

[41] Tricia Bacon and Austin C. Doctor, “The Death of Bilal al-Sudani and Its Impact on Islamic State Operations,” GWU Program on Extremism, March 2, 2023.

[42] Katharine Houreld, “Killing of top ISIS militant casts spotlight on group’s broad reach in Africa,” Washington Post, February 3, 2023.

[43] “Statement by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III on Somalia Operation,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 26, 2023.

[44] Eric Schmitt, “Ties to Kabul Bombing Put ISIS Leader in Somalia in U.S. Cross Hairs,” New York Times, February 4, 2023.

[45] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, June 16, 2023.

[46] Aaron Zelin, “The Islamic State’s External Operations Are More Than Just ISKP,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, July 26, 2024.

[47] For more on the growing global integration of all of the Islamic State’s geographically disparate franchises, see Aaron Zelin, “A Globally Integrated Islamic State,” War on the Rocks, July 15, 2024.

[48] See, as an example, “The Islamic State in East Africa,” European Institute of Peace, September 2018.

[49] “Ethiopian authorities say Al-Shabaab, Islamic State planning attacks on hotels,” Africanews, September 23, 2019.

[50] Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State Somalia eulogizes foreign fighters,” FDD’s Long War Journal, January 23, 2019.

[51] Thomas Joscelyn, “Shabaab executes alleged spies in southern Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, October 11, 2018; David K. Li, “FBI arrests three men from Lansing, Michigan, for allegedly supporting ISIS,” NBC News, January 23, 2019.

[52] Ibid.; author (Weiss) interview, Somali security source, Kampala, Uganda, July 2024.

[53] “The Islamic State in East Africa,” p. 18.

[54] “Treasury Sanctions Terrorist Weapons Trafficking Network in Eastern Africa,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 1, 2022.

[55] Thomas Joscelyn, “American jihadist reportedly flees al Qaeda’s crackdown in Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, December 8, 2015; Al-Naba Issue 242, Islamic State, July 9, 2020; “Feds charge Minnesota man who they say trained with ISIS and threatened violence against New York,” Associated Press, February 17, 2024.

[56] Jason Warner, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Three ‘New’ Islamic State Affiliates,” CTC Sentinel 10:1 (2017).

[57] “The Islamic State in East Africa,” p. 14.

[58] Thomas Joscelyn and Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State video promotes Somali arm, incites attacks during holidays,” FDD’s Long War Journal, December 27, 2017.

[59] Weiss, “Islamic State Somalia eulogizes foreign fighters.”

[60] “Answering the Call #3 – Wilayat al-Sumal,” Islamic State, February 28, 2020, available at Jihadology.

[61] “Upon the path of the Conquerors – Wilayat al-Sumal,” Islamic State, July 30, 2022, available at Jihadology.

[62] Author (Weiss) interview, Somali security official, Kampala, Uganda, July 2024.

[63] Author (Weiss) interview, Somali security official, Kampala, Uganda, July 2024.

[64] Information provided to author (Weiss) by Somali security source, April 2024.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Fred Kagonye, “Three arrested on their way to join ISIS in Puntland,” Standard, April 2023.

[67] Mary Wambui, “Detectives finally seize 3 terror suspects on the run for 7 years,” Nation, May 8, 2023.

[68] Information provided by Congolese security sources, December 2023; “Letter dated 31 May 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, June 4, 2024, p. 58.

[69] Puntland Security Force, “Cimraan Maxamed Calaawi waa ajnabi kasoo jeeda dalka Tanzania…,” Facebook, August 15, 2024.

[70] See, as examples, “Somalia: Moroccan nationals linked to ISIS, arrested in Puntland,” Garowe Online, November 23, 2023; Abdirisaq Shino, “Somalia: Puntland Police Arrest Two Suspected Daesh/ISIS Members in Bari Region,” Horseed Media, February 9, 2024; “Somalia: Foreign ISIS fighters surrender in Puntland,” Garowe Online, July 2, 2023; “Puntland Court Sentences Six Moroccan Daesh Members to Death,” Halqabsi News, February 29, 2024.

[71] Information provided by Somali security source, April 2024.

[72] Weiss, “Jihadi archives: Islamic State’s eulogy of Sudanese jihadist Mohamad Makkawi Ibrahim.”

[73] Eric Schmitt and Helene Cooper, “Senior ISIS Leader in Somalia Killed in U.S. Special Operations Raid,” New York Times, January 26, 2023.

[74] “Top ISIS Commander Among Suspects Apprehended in Puntland Anti-Terror Operations,” Somali Digest, June 27, 2023.

[75] Author (Weiss) interview, Somali security source, Kampala, Uganda, July 2024.

[76] “Sudan brings home 8 children of ISIS fighters in Libya,” Sudan Tribune, June 20, 2017.

[77] Aaron Zelin, “The Others: Foreign Fighters in Libya,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, January 16, 2018.

[78] Information provided by Somali security source, July 2023; Shino.

[79] “Man arrested in Haifa district for planning to join ISIS in Somalia,” Jerusalem Post, June 17, 2024.

[80] Mina al-Lami, “1/ 2023 has been a tough one for #ISIS, whose activity was down by more than half compared to last year …,” X, December 21, 2023.

[81] “Somalia rules out negotiations with Al-Shabaab,” Garowe Online, June 30, 2024.

[82] “IntelBrief: Islamic State Resurging in Mozambique,” Soufan Center, March 21, 2024; “Actor Profiles: Islamic State Mozambique (ISM),” ACLED, October 30, 2023; Tara Candland, Ryan O’Farrell, Laren Poole, and Caleb Weiss, “The Rising Threat to Central Africa: The 2021 Transformation of the Islamic State’s Congolese Branch,” CTC Sentinel 15:6 (2022).

[83] “Terrorismo, il 20enne arrestato a Bari progettava un attentato a San Pietro per Natale: ‘Mettiamo bombe nelle chiese,’” Repubblica, December 17, 2018.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Ibid.

[86] “Letter dated 1 November 2019 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992),” United Nations Security Council, November 1, 2019, pp. 19-20.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Ibid.

[89] Ibid.

[90] “Swedish security service says 4 people arrested on suspicion of preparing ‘terrorist offenses,’” Associated Press, March 7, 2024.

[91] “Swedish security service detains imam linked to Islamic State in Somalia,” Hiraan Online, May 1, 2024.

[92] Alexandra Enberg, “Sweden safe haven for terrorists: Security expert,” Andalou Agency, March 12, 2024.

[93] “Teorin: Gängkriminella värvas till islamistisk terror,” Expressen, May 21, 2024.

[94] Ibid.

[95] Magnus Sandelin, “The Swedish Connection,” Hate Speech International, January 18, 2016.

[96] Weiss, O’Farrell, Candland, and Poole.

[97] Riccardo Valle, “Islamic State’s Pakistan Branch Follows ISKP in Threatening the West and Foreign Interests,” Militant Wire, July 14, 2024; Uday Bakshi, “The Rise of the Islamic State-Aligned East Asia Knights Outlet,” Militant Wire, June 20, 2022.

[98] Lucas Webber and Daniele Garofalo, “The Islamic State Somalia Propaganda Coalition’s Regional Language Push,” CTC Sentinel 16:4 (2023).

[99] Lucas Webber and Daniele Garofalo, “Fursan al-Tarjuma Carries the Torch of the Islamic State’s Media Jihad,” Global Network on Extremism and Technology, June 5, 2023.

[100] Lucas Webber and Riccardo Valle, “Islamic State Khorasan’s Expanded Vision in South and Central Asia,” Diplomat, August 26, 2022.

[101] Lucas Webber and Daniele Garofalo, “Daesh Expands its Language Capabilities to Amharic,” Extremist Monitoring Analysis Network, November 29, 2022.

[102] Colin Clarke, Lucas Webber, and Peter Smith, “ISKP’s Latest Campaign: Expanded Propaganda and External Operations,” Global Network on Extremism and Technology, June 27, 2024; Amira Jadoon, Abdul Sayed, Lucas Webber, and Riccardo Valle, “From Tajikistan to Moscow and Iran: Mapping the Local and Transnational Threat of Islamic State Khorasan,” CTC Sentinel 17:5 (2024).

[103] Matt Smith, “Somali jihadists recruit in U.S., Canada, Europe,” CNN, September 23, 2013; Lorrie Flores, “Motivating Factors in Al-Shabaab Recruitment in Minneapolis, Minnesota,” Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies, Walden University, 3093, 2016; Paul Joosse, Sandra M. Bucerius, and Sara K. Thompson, “Narratives and Counternarratives: Somali-Canadians on Recruitment as Foreign Fighters to Al-Shabaab,” British Journal of Criminology 55:4 (2015): pp. 811-832.

[104] “Feds charge Minnesota man who they say trained with ISIS and threatened violence against New York.”

[105] Ibid.

[106] Ibid.

[107] “U.S. Citizen Charged with Providing Material Support to Isis and Receiving Military-Type Training at Isis Fighter Camp,” U.S. Department of Justice, February 16, 2024.

[108] Ibid.

Skip to content

Skip to content