Abstract: In recent months, there have been a series of vehicular attacks in Germany, the United States, and Israel targeting civilians during celebrations and public gatherings. This is representative of an increase in the use of the tactic. Following the Nice and Berlin attacks in 2016, vehicular ramming terrorist attacks in North America and Europe reached a peak in 2017, before subsiding with the waning of the international terror threat posed by the Islamic State and its supporters. Of the 18 terrorist vehicular ramming attacks between 2014 and March 2025, 15 (83%) were carried out by jihadis and three (17%) by right-wing extremists. Since 2016, governments and security practitioners have focused significant attention on protecting against the vehicle-ramming threat to pedestrianized areas, bringing in new technologies. Yet, the relative ease of launching a vehicle attack and the very large number of soft targets available means it is a tactic that is very difficult to defend against. When it comes to indicators and warnings of future attacks, the demonstration effect created by high-casualty vehicle-ramming attacks has in the past seemingly produced a surge in copycat attacks, which means the security agencies should be particularly vigilant given the recent uptick in high-profile attacks, including the New Orleans attack.

Five recent mass-casualty attacks underline the continued threat posed by the vehicle-ramming terrorist tactic. On December 20, 2024, Taleb Jawad Al-Abdulmohsen, a 50-year-old Saudi psychiatrist and self-professed atheist and anti-Islamist,1 drove his rented BMW X3 around the Magdeburg Christmas Market in northeast Germany. Using an emergency escape road set up by local law enforcement,2 the perpetrator was able to drive into the crowd for 400 meters, killing six and injuring 299.3

Eleven days later, Shamsud-Din Jabbar, a U.S. veteran from Texas, drove a Ford F-150 Lightning pickup truck flying an Islamic State flag into pedestrians celebrating New Year’s Eve on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, Louisiana.4 Crashing his vehicle after 400 meters, he opened fire on the crowd before being neutralized by law enforcement officers. Fourteen people were killed and 35 were injured during the attack.5

A few weeks later, on February 13, 2025, Farhad Noori, a 24-year-old Afghan national, rammed his Mini Cooper into a union demonstration close the Munich train station. Two people—a mother and her two-year-old daughter—were killed and 37 others were injured before the suspect was arrested by German law enforcement. Noori was known to share Islamist content online; he screamed “Allah Akbar” multiples times as he was arrested.6

A further two weeks later, in a terrorist attack on February 27, 2025, a 53-year-old Palestinian driver injured 13 people at a bus stop in Israel before being neutralized by Israeli law enforcement.7

Most recently, on March 3, 2025, in Mannheim, Germany, a 40-year-old German national with mental health challenges drove his car into a crowd, before fleeing. The attack killed two people and injured 11 others. The driver then attempted suicide using an alarm pistol in his car, before being detained.8

This article explores the characteristics of vehicular attacks, with part one discussing the tactical advantages they offer to the assailants both during the preparation of attacks and in their execution. The second part of the article discusses the evolution of the threat, and the third part examines the evolution of prevention efforts.

Characteristics of Vehicular Attacks

Vehicle-ramming tactics, and efforts to stop them, are far from a new phenomenon and were first observed in Israel in the early 1970s and have more recently been a regular feature of Islamic State terrorism in the West.9 Vehicular attacks are, by definition, a low-skill and low-tech modus operandi. Most individuals are familiar with the use of a motor vehicle, and no technical knowledge is required outside of the target selection phase of the attack. Access to a vehicle can be gained through various means such as theft (as seen in Berlin in 2016 where Anis Amri stole the truck he used to target the Breitscheidplatz Christmas Market)10 or taken from work (as seen in an attack in Jerusalem in 2008 involving a bulldozer).11

In other cases, assailants have used their personal vehicles during attacks, as seen as in a car-ramming attack in Munster, Germany, in 201812 and Waukesha, Wisconsin, in December 2021.13 In numerous cases, perpetrators rented—at no significant cost—the vehicles they used in attacks. For example, Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel, who carried out what remains the deadliest vehicular attack in history in 2016 in Nice, France, rented a truck for a few thousand euros.14 The rise of vehicle-sharing apps, similar to the one used by the New Orleans attacker, can reduce the cost of obtaining a vehicle while at the same time allow perpetrators to avoid whatever scrutiny they might face from commercial car renting companies.a

Perpetrators of vehicular attacks also have access to a vast number of potential targets given the growth of pedestrianized areas in urban centers and of open-air gatherings following the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite attempts by authorities to protect certain zones where there is high foot traffic, it remains all too easy for perpetrators to find targets. According to an examination by the authors of mass casualty attacks in the West between January 2012 and December 2022—defined as attacks in which four or more victims were killed—vehicular ramming was the second most common method used after mass shootings.15

Vehicular attacks also have a particularly shocking component, due to their speed and kinetic force and the fact that they occur in highly vulnerable pedestrian spaces. This facilitates an important aspect of terrorism: media coverage, especially if images or videos of the attack are posted online or broadcast. In the case of the Magdeburg attack, CCTV images immediately spread on social media in the minutes following the attack, before being broadcast on traditional channels. Some assailants seek to maximize the media impact, with one example being the New Orleans attacker flying an Islamic State flag at the back of his attack vehicle.16

Countering vehicular attacks is hugely challenging. Potential targets are numerous, changing in number according to seasonal activities, events, or time of day. The type of vehicle used by attackers will also impact the type of protection that needs to be set up, according to speed, weight, size, and special capacity in the case of a weaponized excavator or bulldozer. Detection of potential attackers is also made difficult because of the number of vehicles in urban areas and because of the usual absence of criminal acts in the preparation of attacks. In the Magdeburg, New Orleans, and Munich attacks, the intention of the perpetrators was only clear to law enforcement personnel at the moment the vehicle entered the restricted zones, just seconds before the attacks began.

On the response side, vehicular attacks are extremely fast-paced events with the immediate potential for a large number of casualties, including numerous polytraumatized victims who need immediate medical attention. The speed and impact of vehicular attacks sometimes resemble more of a large bomb attack than a mass shooting. The complexity of the victims’ injuries presents challenges that go beyond the medical capacities of first responders.

The Evolution of the Threat

According to the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database, there were 288 incidents of vehicular terrorism from 1970 to 2020.17 This number is focused on vehicles used as blunt-force weapons to attack civilians and does not include vehicle-borne explosives, or, in the case of Israel, against soldiers.

In 1973, Olga Hepnarová killed eight people in Prague when she drove her Praga RN truck into a group of pedestrians. Four years later, a man in his early 30s rammed his car into the stage during a Ku Klux Klan rally in Plains, Georgia, injuring some 30 people.18 Seven years later, in 1984, an individual looking to “get even with the police” drove his car into a crowd in Los Angeles, killing one person and injuring 54 injured.19 Similar attacks took place elsewhere in the world, including in Australia and Brazil.20 From 1990 to early 2000, there were regular vehicular attacks in Israel and the West Bank, frequently targeting IDF soldiers at bus stops.21 This method of attack continued and expanded in the 2010s, mostly used by lone operators organizing attacks without the support of a group. In a 2010 edition of the al-Qa`ida magazine Inspire, jihadi groups promoted such tactics due to their efficiency, calling followers to “mow down the enemies of Allah.”22 In the mid-2010s, there was an increase in Palestinian vehicular attacks in Israel and the West Bank,23 at the same time a wave of Islamic State-organized and -inspired attacks started in Western Europe.24

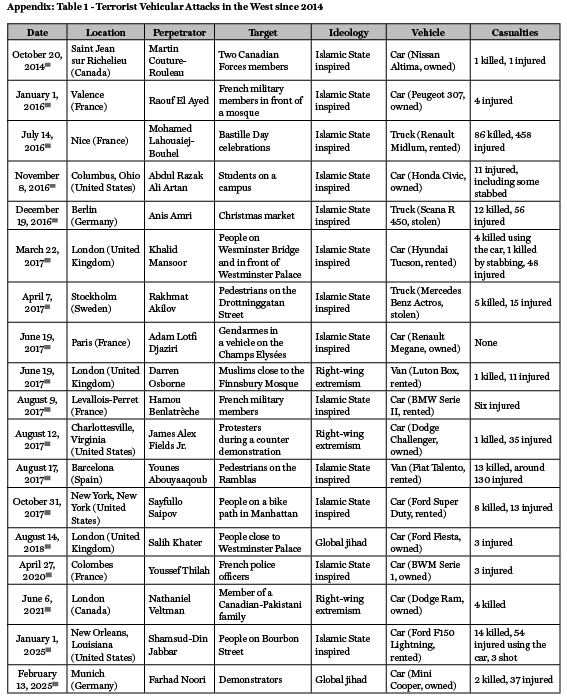

In September 2014, Islamic State spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani called for supporters to use vehicles as weapons, saying that if they were “not able to find an IED or a bullet,” then they should “single out the disbelieving American, Frenchman, or any of their allies, smash his head with a rock, or slaughter him with a knife, or run him over with your car.”25 Just weeks later, on October 20, 2014, one of the group’s supporters, Martin Couture-Rouleau, heeded the call in a vehicle attack that killed a member of the Canadian armed forces.26 There were, however, no further terrorist vehicular ramming attacks in the West until a January 2016 attack on the French military in the town of Valence. (See Table 1 in the appendix.)

The watershed moment for the threat came on France’s national day in 2016. At 10:32 PM on July 14, a 19-ton Renaud Midlum truck, driven by 31-year-old Tunisian jihadi named Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel, plowed into the crowd on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, France, for more than a kilometer. Eighty-six people were killed and 458 were injured in the span of four minutes and 17 seconds, before the terrorist was shot dead by law enforcement. He had carefully organized his attack, using his job as a delivery man to rent the truck in advance, and practicing reconnaissance and driving in the area 11 times in the days preceding the attack.27 In the years that followed the Nice attack, there was an increase in mass-casualty vehicular attacks in the West. (See Table 1.) Just five months after the Nice attack, in December 2016, another jihadi attack using a semi-trailer truck killed 12 people at a Christmas market in Berlin. As noted by Vincent Miller and Keith Hayward, “the VRA [vehicle ramming attack] has transitioned from being a relatively rare occurrence, to become, by 2016, the most lethal form of terror attack in Western countries, claiming just over half of all terrorism-related deaths in the West that year.”28

The following year saw a surge in vehicular terrorist attacks in the West (defined for the purpose of this study as North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand), with seven attacks, the most seen in any year. (See Table 1.) These included mass-casualty attacks by jihadis in London in March 2017 (five killed, including four with a vehicle),29 in Stockholm in April (five killed),30 Barcelona in August (13 killed),31 and New York in October (eight killed).32

It is noteworthy that there was a surge in vehicular terrorist attacks following the two deadliest attacks (Nice and Berlin). The authors assess that this created a demonstration effect in which the high casualties and significant media coverage of those attacks showed the effectiveness of this terror tactic and in turn produced a copycat effect. This suggests that the demonstration effect is a more powerful indicator of future attacks than calls by terrorist leaders such as the late Abu Muhammad al-Adnani for the tactic to be used.

The surge in vehicular attacks during this period was also seen in the developed world as a whole, to include Palestinian terrorism targeting Israel. Writing in 2019, Brian Michael Jenkins stated, “because there are relatively few events over a long period of time (more than 45 years), the trend lines can be misleading. However, the recent increase is obvious. There were 16 attacks between 1973 and 2007 and 62 attacks between 2008 and the end of April 2018. Thirty of these occurred in 2017 and the first four months of 2018 alone.”33 According to Brian Michael Jenkins and Bruce Butterworth, the use of vehicles as weapons of terror in developed countries increased from two in the years 1994-1997 to 68 in the period from 2014-2019.34 b

These tactics soon extended beyond the jihadi ecosystem to include attacks perpetrated by non-ideological attackers in Melbourne, Australia, in 2017 (six killed, 27 injured);35 Munster, Germany, in 2018 (four killed, 20 injured);36 Trier, Germany, in 2020 (five killed, 23 injured);37 and Waukesha, Wisconsin, in 2021 (six killed, 62 injured). Far-right terrorists also applied the same tactics, in London, United Kingdom, in front of the Finsbury Park Mosque where one person was killed and 12 others were injured by Darren Osborne in 201738 and London, Canada, where a 20-year-old killed four members of a Pakistani family with his car in 2021.39

According to the authors’ database, there were 18 terrorist vehicular ramming attacks between January 2014 and March 2025 in the West. The large majority of attacks were carried out by jihadis, many of whom were inspired by the Islamic State. Fifteen (83%) of the terrorist attacks were carried out by jihadis and three (17%) by right-wing extremists. Five of the attacks (28%) targeted the military, police, and security services.

Cars were most often used in the attacks. Thirteen of the attacks (72%) were carried out by cars, three of the attacks (17%) were carried out by trucks and two (11%) by vans. It is notable that the two highest casualty attacks were carried out by trucks—the Nice attack (86 killed and 458 injured) and the Berlin attack (12 killed, 56 injured)—underlining that this form of vehicular attack poses the greatest threat. Nine of the attacks (50%) were carried out by vehicles owned by the perpetrators, seven of the attacks (39%) were carried out in rented vehicles, and two (11%) were carried out in stolen vehicles, in both cases trucks.

A total of 152 people died in the 18 attacks. Demonstrating that attacks are highly likely to produce casualties after being launched, 12 (67%) of the attacks produced fatalities and only one attack resulted in no injuries.

As can be seen Table 1, with the waning of the Islamic State international terror threat, terrorist use of vehicular attacks dropped in the West from 2018 onward, before ticking up in 2025 with the attacks in New Orleans and Munich. Both these attacks, especially the New Orleans attack, received significant media coverage or, in other words, created a new demonstration effect that could lead to a surge in copycat attacks in the months ahead.

The Evolution of Prevention Measures

Beginning in the 1990s, there have been efforts in the United States to harden buildings and other critical infrastructure from vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs).40 In many cases, this had the added benefit of protecting pedestrians who use the sidewalks separating the street from commercial or government buildings. Security practitioners saw bollards as one means of hardening the landscape while not limiting the aesthetic value of the area. From the1990s, the use of bollards has been the preferred choice of protecting campuses and buildings in the United States. In the United States alone, 90,000 sites have added concrete bollards since the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.41

Attempts to prevent any type of vehicular collision with pedestrians began as early as the 18th century with the use of wood and iron structures to direct pedestrians away from horse-drawn vehicles.42 Preventative measures continued to be adopted in the form of streets and highways being designed around neighborhoods well into the 20th century.43 As Paul Hess and Sneda Mandhan point out, in New York, prior to the 2017 vehicle-ramming attacks in Nice and Berlin, physical security of public spaces was focused on VBIEDs.44 The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency did not provide any guidance on how to protect against vehicle ramming that was not delivered via VBIED.45 Protection rested on diversion of vehicles from high pedestrian zones with the use of bollards and other physical barriers, or limiting access of vehicles and pedestrians to areas deemed critical.46 According to the Mineta Transportation Institute, since 2012, preventative measures have evolved to include more technology, such as cameras, fencing, and effective intelligence gathering, to disrupt potential attacks.47

It was after the Nice and Berlin attacks of 2016 that governments and security practitioners in the West focused significant attention on protecting against the vehicle-ramming threat to pedestrianized areas. Governments and security practitioners began working on new prevention techniques. Traditional retractable traffic bollards were deemed no longer sufficient because they cannot withstand the impact of large trucks. Stronger protective measures were put in place, with, for example, the French company La Barrière Automatique (LBA) developing a retractable bollard capable of withstanding the impact of a 7.5-ton truck going 80 kilometers per hour (approximately 50 miles per hour).48 The LBA model is deployed one meter above ground and another 1.70 meters below, providing an ‘iceberg’ protection effect. While traditionally delivering products for the French Vigipirate national security plan, LBA is seeing its customer base expand from embassies, industrial sites, and stadiums to communities and businesses such as shopping centers and supermarkets. Much like the LBA model, Intertex Barriers of Valencia, California, has developed a retractable barrier that can be manually operated or function autonomously.49

In recent years, the use of active, passive, deployable, or improvised vehicle-ramming mitigation tools became common practice.50 Vehicle inspections and security checks at entry points, remote parking, and shuttle services have also helped in mitigating the risk as once an attack is underway, it is extremely difficult to stop because of the speed of the attack and the difficulty in bringing a moving vehicle to a stop. During the Nice attack, for example, the killing was only stopped by the action of a civilian was able to throw his scooter in front of the 19-ton truck, slowing it down so that law enforcement officers were able to shoot and neutralize the terrorist.51 The use of hollow point bullets by a majority of law enforcement agencies52 is another impediment to stopping attacks in their tracks due to the deflection caused by the windshield.53 The difficulty of responding to an active vehicular ramming attack underlines the importance of preventing attacks.

Conclusion

Vehicular attacks committed by terrorists are not a new phenomenon. As described in this article, this modus operandi has been used by lone actors and groups for decades around the world. The recent cases in Germany and the United States are not a return of the vehicular attacks in the West but rather an evolution of the modus operandi, using new technical tools such as the use of electric cars and peer-to-peer apps.54

The recent attacks do represent an uptick in the use of the tactic, however. Following the Nice and Berlin attacks in 2016, vehicular ramming terrorist attacks in North America and Europe reached a peak in 2017, before subsiding with the waning of the international terror threat posed by the Islamic State and its supporters. Of the 18 terrorist vehicular ramming attacks between 2014 and March 2025, 15 (83%) were carried out by jihadis and three (17%) by right-wing extremists. Most of the attacks involved cars but the two of the highest casualty attacks (Nice and Berlin) involved trucks, underlining that these forms of vehicular attacks pose the greatest threat. Most of the attacks produced fatalities and only one resulted in no injuries, demonstrating the high likelihood that vehicular ramming attacks will produce casualties once launched.

Since 2016, governments and security practitioners have focused significant attention on protecting against the vehicle-ramming threat to pedestrianized areas, bringing in new technologies. Protective measures such as using fixed or mobile bollards are key because once an attack is underway, it is very difficult to stop. But the facility of launching a vehicle attack and the very large number of soft targets means it is a tactic that is very difficult to defend against. Therefore, preventing attacks from being carried out in the first place through intelligence and law enforcement efforts is key but nonetheless challenging because an attack involving a vehicle can be planned and prepared with little risk of arousing suspicion.

When it comes to indicators and warnings of future attacks, the demonstration effect created by high-casualty attacks has, in the past, seemingly produced a surge in copycat attacks, which means that security agencies should be particularly vigilant in the months ahead given the recent uptick of high-profile attacks, including in New Orleans. CTC

Alexandre Rodde is a Visiting Fellow at the Protective Security Lab at Coventry University. He works as a security consultant and analyst, specializing in terrorism, mass shootings, and violent extremism in the French national security apparatus. He is the author of Le Jihad en France: 2012-2022 (not yet available in English).

Justin Quinn Olmstead, Ph.D., is a historian for Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Prior to that, he was Associate Professor of History at the University of Central Oklahoma. His most recent book is From Nuclear Weapons to Global Security: 75 Years of Research and Development at Sandia National Laboratories. He is a Resident Fellow at the CMC, a Senior Research Fellow at the Armed Services Institute in the Center for Military Life, Thomas University, Visiting Fellow at the Center for Peace & Security, Coventry University, U.K., and an Associate Editor for the Journal of the Society for Terrorism Research.

© 2025 Alexandre Rodde, Justin Olmstead

Substantive Notes

[a] According to reports, the vehicle used by Shamsud-Din Jabbar in the New Orleans attack was rented via the car-sharing app Turo. Natalie Neysa Alund, “What is Turo? Car rental app was used in both New Orleans attack and Las Vegas explosion,” USA Today, January 2, 2025.

[b] The data includes all cases, including non-ideological ones, in OECD-signatory countries.

Citations

[1] “The ‘atheist’ Saudi refugee suspected of Germany attack,” Agence France-Presse, December 21, 2024.

[2] “Täter nutzte Fluchtweg – hat Sicherheitskonzept versagt?” T-Online, December 21, 2024.

[3] “Magdeburg Christmas market attack deaths rise to six,” BBC, January 6, 2025.

[4] Brian Thevenot and Chris Kirkham, “Exclusive: New Orleans’ planned new Bourbon Street barriers only crash-rated to 10 mph,” Reuters, January 4, 2025.

[5] Tucker Reels and Kerry Breen, “At least 14 killed, dozens hurt on Bourbon Street in New Orleans as driver intentionally slams truck into crowd; attacker dead,” CBS News, January 2, 2025.

[6] Alex Therrien, “Mother and child die from injuries after Munich car attack,” BBC, February 15, 2025.

[7] Nadine El Bawab and Jordana Miller, “At least 13 injured after car rams into bus stop in Israel,” ABC News, February 27, 2025.

[8] “Two dead, several injured in Germany as car rams into crowd,” Monde, March 3, 2025; Orestes Georgiou Daniel, “Mannheim car ramming attack suspect a German with history of mental illness, say investigators,” Euronews, March 3, 2025.

[9] Brian Michael Jenkins and Bruce R. Butterworth, “An Analysis of Vehicle Ramming as a Terrorist Tactic,” Security Perspective, Mineta Transportation Institute, San Jose State University, May 2018.

[10] “Berlin truck attacker Anis Amri killed in Milan,” BBC, December 23, 2016.

[11] “At least four dead in Jerusalem bulldozer attack,” France 24, July 2, 2008.

[12] “Münster victim dies weeks after car rampage,” Deutsche Welle, April 26, 2018.

[13] “Judge sentences man to life in prison for Waukesha Christmas parade attack,” NPR, November 16, 2022.

[14] Alexandre Rodde, Le Jihad en France 2012-2022 (Paris: Editions du Cerf, 2022), pp. 215-216.

[15] Based on the author’s (Rodde) database, unpublished.

[16] “FBI Statement on the Attack in New Orleans,” FBI National Press Office, January 1, 2025.

[17] “Global Terrorism Database 1970 – 2020 [data file],” START, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2022.

[18] “Car Crashes Klan Rally in Plains, 30 injured,” Eugene Registe Guard, July 3, 1977.

[19] “Driver Booked in Fatality Close to Olympic Village,” Blade Toledo, July 29, 1984.

[20] “Man who drove road train into pub denied parole,” ABC News (Australia), September 5, 2013; “Estudante Joga Caro Na Mltidao e Fere 15,” Jornal do Brasil, April 20, 1993.

[21] Deborah Sontag, “Palestinian’s Hit-and-Run Bus Kills 8 Israelis and Injures 20,” New York Times, February 14, 2001.

[22] Eve Sampson, “Vehicle Ramming Attacks: Using Cars and Trucks as Weapons Has Become Common,” New York Times, January 1, 2025.

[23] Brian Michael Jenkins and Bruce R. Butterworth, “‘Smashing Into Crowds’ — An Analysis of Vehicle Ramming Attacks,” San José State University, Mineta Transportation Institute, November 2019.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Duncan Gardham, “ISIL issued warning to ‘filthy French,’” Politico, November 15, 2015.

[26] “Canadian soldier killed by convert to Islam in hit and run,” Guardian, October 21, 2014.

[27] Rodde, pp. 215-216.

[28] Ryan Scott Houser, “Democratization of terrorism: an analysis of vehicle-based terrorist events,” Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open, September 8, 2022; Vincent Miller and Keith J. Hayward, “’I Did My Bit’: Terrorism, Tarde and the Vehicle Ramming Attack as An Imitative Event,” British Journal of Criminology 59:1 (2019): p. 4.

[29] “Westminster attack: What happened,” BBC, April 7, 2017.

[30] “Stockholm truck attack: Who is Rakhmat Akilov?” BBC, June 7, 2019.

[31] “Barcelona attack: 13 killed as van rams crowds in Las Ramblas,” BBC, August 17, 2017.

[32] “Sayfullo Saipov Indicted on Terrorism and Murder In Aid Of Racketeering Charges In Connection With Lower Manhattan Truck Attack,” U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of New York, November 21, 2017.

[33] Jenkins and Butterworth.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Karen Percy, “Bourke St murderer James Gargasoulas given life jail sentence but could get parole in 46 years,” ABC News, February 21, 2019.

[36] “German police see mental illness behind Muenster van attack,” France 24, April 8, 2018.

[37] “Trier: Five die as car ploughs through Germany pedestrian zone,” BBC, December 1, 2020.

[38] Kevin Rawlinson, “Darren Osborne jailed for life for Finsbury Park terrorist attack,” Guardian, February 2, 2018.

[39] Kate Dubinski, “Judge rules killer of London, Ont., Muslim family committed terrorism, calling it a textbook example,” CBC, February 22, 2024.

[40] Paul Hess and Sneha Mandhan, “Ramming Attacks, Pedestrians, and the Securitization of Streets and Urban Public Space: A Case Study of New York City,” Urban Design Institute 28:1 (2022).

[41] Gerald Dlubala, “Concrete Bollards Are Crucial To Separating Cars From Pedestrians and Buildings,” Park and Facilities Catalog, May 17, 2017.

[42] Mark Jenner, “Circulation and Disorder: London Streets and Hackney Coaches, 1640-1740” in Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker eds., The Streets of London: From the Great Fire to the Great Stink (London: Rivers Oran Press, 2008), p. 43.

[43] Hess and Mandhan.

[44] Ibid.

[45] “Incremental Protection for Existing Commercial Buildings from Terrorist Attack: Providing Protection to People and Buildings,” Risk Management Series, FEMA 459, April 2008.

[46] Nicole Gelinas, “Vehicular Terrorism in the Age of Vision Zero,” Bloomberg, October 17, 2018; “Incremental Protection for Existing Commercial Buildings from Terrorist Attack;” Hess and Mandhan.

[47] Daniel C. Goodrich and Frances L. Edwards, “Transportation, Terrorism and Crime: Deterrence, Disruption and Resilience,” Mineta Transportation Institute, Project 1896, January 2020.

[48] Anastassia Gliadkovskaya, “Watch: This destructive barrier was created to stop lorry attacks,” Euronews, June 26, 2018.

[49] Jeff Anderson, “Anti-Terrorist Barriers Help Protect Facilities,” Library AutomationDirect.com, June 1, 2007.

[50] “Vehicle Incident Prevention and Mitigation Security Guide,” Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, April 2024.

[51] Rodde, p. 213.

[52] “U.S. Social Security orders 174,000 hollow-point bullets,” CBC, September 4, 2012.

[53] Chris Butler, “Implications of shooting through a windshield,” Blue Line, June 25, 2022.

[54] Yannick Veilleux-Lepage and Marc-André Argentino, “2025 New Orleans Truck Attack: The Role of Electric Vehicles and Peer-to-Peer Platforms,”ICCT, January 2025.

[55] “Canadian soldier killed by convert to Islam in hit and run.”

[56] Rodde, Le Jihad en France 2012-2022.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Mitch Smith, Richard Pérez-Peña, and Adam Goldman, “Suspect Is Killed in Attack at Ohio State University That Injured 11,” New York Times, November 28, 2016.

[59] “Berlin Christmas market attack,” Deutsche Welle, December 17, 2021.

[60] “London attack: Khalid Masood identified as killer,” BBC, March 23, 2017.

[61] “Stockholm truck attack.”

[62] Rodde, Le Jihad en France 2012-2022.

[63] “Darren Osborne guilty of Finsbury Park mosque murder,” BBC, February 1, 2018.

[64] Rodde, Le Jihad en France 2012-2022.

[65] “A woman recalls the deadly car attack at the Charlottesville rally organizers’ trial,” NPR, November 8, 2021.

[66] “Barcelona attack.”

[67] Benjamin Mueller, William K. Rashbaum, and Al Baker, “Terror Attack Kills 8 and Injures 11 in Manhattan,” New York Times, October 31, 2017.

[68] “Westminster car crash driver Salih Khater jailed for life,” BBC, October 14, 2019.

[69] Rodde, Le Jihad en France 2012-2022.

[70] Dubinski.

[71] Reels and Breen.

[72] Therrien.

Skip to content

Skip to content