Abstract: Iran provides Lebanese Hezbollah with some $700 million a year, according to U.S. government officials. Beyond that cash infusion, Tehran has helped Hezbollah build an arsenal of some 150,000 rockets and missiles in Lebanon. And yet, Hezbollah also leverages an international network of companies and brokers—some Hezbollah operatives themselves, others well-placed criminal facilitators willing to partner with Hezbollah—to procure weapons, dual-use items, and other equipment for the benefit of the group’s operatives and, sometimes, Iran. In the context of the war in Syria, Hezbollah’s procurement agents have teamed up with Iran’s Quds Force to develop integrated and efficient weapons procurement and logistics pipelines that can be leveraged to greatly expand Hezbollah’s weapons procurement capabilities.

Hezbollah has long prioritized its weapons and technical procurement efforts, but with the group’s heavy deployment in the war in Syria, its procurement officers have taken on even greater prominence within the organization. Today, in the context of the war in Syria, some of Hezbollah’s most significant procurement agents have teamed up with Iran’s Quds Force to develop integrated and efficient weapons procurement and logistics pipelines that can be leveraged to vastly expand Hezbollah’s weapons procurement capabilities.

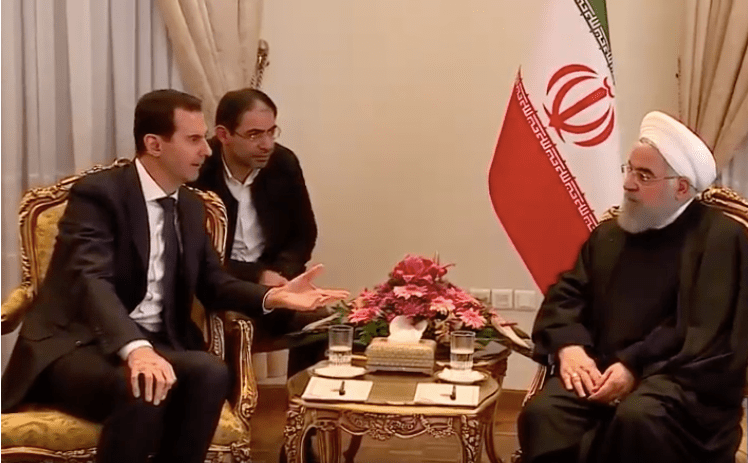

The latest sign of how closely Quds Force and Hezbollah procurement officers now work together came to light when Syrian President Bashar al-Assad visited Tehran for surprise meetings with President Hassan Rouhani and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on February 25, 2019. For the purpose of operational security, Assad’s visit reportedly dispensed with traditional protocols. The Iranian President was only informed of Assad’s visit shortly before he arrived, and Iran’s Foreign Minister was neither informed nor included in the meetings.1 Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani reportedly oversaw the security protocols for the visit himself and flew with Assad on the plane to Tehran.2 And the person Soleimani chose to accompany him to these meetings and serve as a notetaker was Mohammad Qasir,3 the head of Hezbollah’s Unit 108—the unit “responsible for facilitating the transfer of weapons, technology and other support from Syria to Lebanon,” according to the U.S. Treasury Department.4

Based in Damascus, Qasir and other senior Hezbollah officials work closely with officers from Quds Force’s Unit 190—which specializes in smuggling weapons to Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Gaza—under the supervision of Qassem Soleimani.5 This smuggling operation is significant in its own right, but it could also be used to assist Hezbollah’s own longstanding procurement efforts around the world, which are often intimately intertwined with the group’s transnational organized criminal networks raising funds through criminal enterprises.

Recent events underscored the scope and scale of these efforts. In November 2018, a Paris court found Mohammad Noureddine and several of his associates guilty of drug trafficking, money laundering, and engaging in a criminal conspiracy to finance Hezbollah.6 The result of an international joint investigation involving seven countries, the conviction marked the first time a European court specifically found defendants guilty of conspiracy to support Hezbollah.7 But it was telling for another reason, too: authorities revealed that at least some of the proceeds of these Hezbollah drug and money laundering schemes were “used to purchase weapons for Hizballah for its activities in Syria.”8

The weapons connection likely raised some eyebrows among analysts and investigators, given the very high levels of state sponsorship and support Iran provides to Hezbollah. But despite that support, Hezbollah, as also detailed in this article, has an established track record of procuring and smuggling weapons through its own channels, parallel to the weapons regularly funneled to the group by Iran. Hezbollah weapons procurement agents oversee this program, though they often rely on criminal facilitators—weapons dealers, smugglers, money launderers, and more—who are uniquely situated to provide the kinds of services necessary to purchase weapons on the black market and deliver them to Hezbollah in Lebanon. These relationships often first develop through criminal financial and money-laundering schemes that broaden out over time to include weapons deals. And then there are other types of procurement activities focused not on weapons themselves but on dual-use items with military applications like computer programs, laser range finders, night-vision goggles, and more.

This article details how now, in the context of the war in Syria, some of Hezbollah’s most significant procurement agents—such as Muhammad Qasir—have teamed up with Iran’s Quds Force to develop integrated and efficient weapons procurement and logistics pipelines through Syria and into Lebanon that can be leveraged to greatly expand Hezbollah’s international weapons procurement capabilities. The Syrian war elevated the importance of such efforts, which quickly increased in scale and scope. As Assad gains control over more of Syria, Hezbollah and the Quds Force will be well placed to leverage their position in Syria along with their newly refined procurement and smuggling pipelines through various channels to secure and send weapons and sensitive technologies back to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Hezbollah’s Early Procurement Efforts

Hezbollah has a long history of independently procuring weapons and dual-use technology through its own networks abroad. A 1994 FBI report stated that Iran, as Hezbollah’s primary sponsor, “provides most of the group’s funding and weaponry.” And yet, the report added, Hezbollah still engaged in what it described as “domestic weapons procurement” activities in the United States, such as an unnamed New York Hezbollah member who was reportedly involved in acquiring night-vision goggles and laser-sighting equipment and sending them to Hezbollah in Lebanon.9

An early example is Fawzi Mustapha Assi, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Lebanon who was caught trying to smuggle night-vision goggles, a thermal-imaging camera, and global-positioning modules to Hezbollah in July 1998. Described by U.S. authorities as a Hezbollah procurement agent, Assi successfully smuggled goods to Hezbollah from 1996 until his arrest.10 Assi pled guilty to material support charges and acknowledged in his post-hearing sentencing memorandum that “the material he provided was meant to support the resistance in south Lebanon in their armed conflict with the Israeli Defense Force.”11

At the same time, according to U.S. authorities Hezbollah operative Mohammad Hassan Dbouk and his brother-in-law, Ali Adham Amhaz, ran a Hezbollah procurement network in Canada under the command of Hezbollah’s chief military procurement officer in Lebanon, Haj Hassan Hilu Laqis. Dbouk allegedly described Assi as “‘the guy’ for getting equipment on behalf of Hezbollah.” According to court documents, Dbouk added that he himself “personally met this individual [Assi] at the airport in Beirut to ensure Hezbollah got the equipment he obtained,” including night-vision goggles and GPS systems.12 According to court filings, Hezbollah procurement officials in Lebanon would later stress to Dbouk that such equipment was desperately needed because “the guys were getting lost, you know, in the woods, or whatever, and they need compasses.”13

According to the FBI, Dbouk turned out to be “an intelligence specialist and propagandist, [who] was dispatched to Canada by Hizballah for the express purpose of obtaining surveillance equipment (video cameras and handheld radios and receivers) and military equipment (night-vision devices, laser range finders, mine and metal detectors, and advanced aircraft analysis tools).”14 According to Canadian authorities, Dbouk’s, Amhaz’s, and Laqis’ efforts bore fruit. For example, after hearing that Hezbollah roadsides bombs in south Lebanon killed an Israeli general, Ali Amhaz allegedly congratulated Dbouk for his part in improving Hezbollah military capabilities.15

Allegedly, Dbouk recognized that his procurement efforts for Hezbollah came under the ultimate authority of Imad Mughniyeh, who served as the head of Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad Organization (IJO)—the organization’s external operations group—until U.S. and Israeli intelligence agents reportedly teamed up to kill him in Damascus in 2008.16 In April 1999, Dbouk allegedly sent a fax to Laqis, informing him that payment was needed for several items Dbouk had purchased. Dbouk allegedly boasted that he had sent Laqis “a little gift” in the form of a PalmPilot and a pair of binoculars and added, “I’m ready to do any thing you or the Father want me to do and I mean anything … !!”17 “The Father,” according to U.S. Attorney Robert Conrad, is a reference to Mughniyeh.18

These cases are typical of the type of small-scale weapons procurement and somewhat larger scale dual-use technology procurement Hezbollah engaged in directly in the run-up to the Israeli withdrawal from southern Lebanon in May 2000. But Hezbollah’s procurement efforts only increased in the wake of that withdrawal. According to a 2003 Israeli assessment, “Hezbollah uses its apparatuses throughout the world not only to strengthen its operational capabilities for launching terrorist attacks, but also as a means of purchasing the advanced arms and equipment needed for the organization’s operational activities. To transact these purchases, Hezbollah uses its operatives who reside outside Lebanon (either permanently or temporarily), ‘innocent’ businesspeople (including Lebanese), and companies founded by the organization (some of which are front companies).”19

Consider the case of Riad Skaff, who worked as a ground services coordinator at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport from 1999 until his arrest in 2007. For a fee, Skaff smuggled bulk cash and dual-use items like night-vision goggles and cellular jammers onto airplanes. Prosecutors argued that Skaff’s conduct “in essence was that of a mercenary facilitating the smuggling of large amounts of cash and dangerous defense items for a fee,” which he knew were destined for Lebanon, “a war-torn country besieged by the militant organization, Hezbollah.”20

In other cases, Hezbollah operatives in the United States raised funds for the purchase of weapons elsewhere, including in Lebanon. Mahmoud Kourani, a convicted Hezbollah fighter trained in Iran, was a one-time resident of Dearborn, Michigan. Bragging to a government informant about his ties to Hezbollah, Kourani once let slip that before he came to the United States, another alleged Hezbollah supporter, Mohammed Krayem, had allegedly sent money to Kourani’s brother, a Hezbollah military commander in Lebanon, to fund the purchase of military equipment from members of the United Nations Protection Forces in Lebanon.21

Operation Phone Flash Exposes Hezbollah’s Procurement, Inc.

In the years following the July 2006 war with Israel, Hezbollah’s procurement kicked into high gear in an effort to replenish its weapons stocks. For big-ticket items, like missiles, Hezbollah relied on Iran, and sometimes Syria.22 But Hezbollah proactively complemented the shipments of other items it received from Iran—from small arms and ammunition to shoulder-fired rockets and dual use items—with material it procured through its own global networks. In December 2011, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah underscored the group’s procurement efforts: “We will never let go of our arms,” he said. “And if someone is betting that our weapons are rusting, we tell them that every weapon that rusts is replaced.”23

Replacing spent ammunition and rusted weapons at the scale needed after the 2006 war demanded an organized procurement channel run by Hezbollah weapons procurement agents around the world. Hezbollah procurement agent Dani Tarraf is a case in point. In 2006, agents with the Philadelphia Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) opened several parallel investigations into Hezbollah criminal activities in suburban Philadelphia, which together became known as Operation Phone Flash.

In the context of Operation Phone Flash, investigators came across Tarraf, a German-Lebanese procurement agent for Hezbollah with homes in Lebanon and Slovakia and business interests in China and Lebanon.24 At first, Tarraf was just underwriting the purchase of stolen merchandise that Hezbollah operatives then shipped and sold around the world. Tarraf was introduced to an undercover FBI agent posing as a member of a crime family, and wasted little time before asking if the criminal enterprise could expand to include the sale of guided missiles and 10,000 “commando” machine guns for Hezbollah.25

In his meeting with the undercover agent, Tarraf expressed interest in a wide array of weapons, including M4 rifles, Glock pistols, and antiaircraft and antitank missiles. Tarraf sought to impress the undercover agent, showing him around his Slovakian company, Power Express, and introducing him to his storage and shipping network and explaining that the weapons would be mislabeled as “spare parts” before being shipped to Syria for Hezbollah. U.S. investigators ultimately determined that Power Express “operated as a subsidiary of Hezbollah’s technical procurement wing.”26

Tarraf was very clear that he wanted weapons that could “take down an F-16.” Tarraf went online and pulled up the precise specifications for the weapons he wanted the undercover agent to procure on his behalf as the FBI taped the conversations and captured his computer search records. Tarraf and the undercover agent soon met in Philadelphia, where Tarraf put down a $20,000 deposit toward the purchase of Stinger missiles and 10,000 Colt M4 machine guns. Tarraf noted that the weapons should be exported to Latakia, Syria, where Hezbollah controlled the entire port. Secrecy would be guaranteed there because Hezbollah could shut down all the cameras when the shipment arrived. Once the items arrived in Syria, Tarraf assured, no shipping paperwork would be required.27 After his arrest in November 2009, Tarraf confessed to being a Hezbollah member and “working with others to acquire massive quantities of weapons for the benefit of Hezbollah.”28

In a parallel case in Philadelphia, an FBI source met in Beirut with Hassan Hodroj, who allegedly served on Hezbollah’s political council. Publicly described as a Hezbollah spokesman and the head of its Palestinian issues portfolio, Hodroj was also deeply involved in Hezbollah’s procurement arm, according to U.S. authorities.29 The details on Hodroj that follow are the facts as presented by the U.S. Department of Justice. Hodroj told the FBI source exactly what he wanted—1,200 Colt M4 assault rifles—and explained that Hezbollah would pay in cash to make it harder for authorities to track the payments back to Hezbollah. Hodroj stressed that Hezbollah primarily needed “heavy machinery” for the “fight against the Jews and to protect Lebanon.” Like Dani Tarraf, Hodroj allegedly wanted the weapons shipped to the port of Latakia, Syria, which he described as “ours.”30 Before the meeting ended, Hodroj broached one more subject: he was also in the market for sensitive technology from the United States, specifically communication and “spy” systems that could help Hezbollah secure its own communications and spy on its adversaries’ communications.31

Throughout this period Hezbollah continued to receive not only considerable funding but also direct weapons shipments from Iran, as documented by the U.S. Defense Department in its 2010 annual report on Iranian military power:

“With Iranian support, Lebanese Hizballah has successfully exceeded 2006 Lebanon conflict armament levels. On 4 November [2009], Israel interdicted the merchant vessel FRANCOP, which had 36 containers, 60 tons, of weapons for Hizballah to include 122mm katyushas, 107mm rockets, 106mm antitank shells, hand grenades, light-weapon ammunition.”32

And yet, a series of U.S.-led international investigations would soon reveal that Hezbollah’s independent weapons procurement program continued unabated.

Hezbollah Procurement as Sanctions Hit Iran and the Syria War Began

Whereas Iran pumped funds and weapons into Hezbollah after the 2006 war, by 2009 declining oil prices and sanctions combined to force Tehran to slash its annual budget for Hezbollah by 40 percent.33 As a result, Hezbollah enacted severe austerity measures to reduce spending and diversified its income portfolio by significantly expanding its international criminal activities.34 In one case, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents caught a weapons trafficker affiliated with Hezbollah, Alwar Pouryan, seeking to sell weapons to the Taliban for desperately needed cash instead of trying to procure weapons for Hezbollah.35 Hard financial times also forced Hezbollah to rely in part on deceptive means to secure funding for development projects in the wake of the 2006 war, such as hiding its own and Iran’s ties to Hezbollah’s construction arm, Jihad al-Bina, when approaching international development organizations for development funding.36

Several investigations only later made public would reveal that Hezbollah created multiple illicit financing and weapons procurement networks in and around this time. For example, according to U.S. prosecutors, from 2009 through 2013, a Hezbollah procurement network including Usama Hamade, Issam Hamade, and Samir Ahmed Berro illegally exported UAV parts and technology to Hezbollah, which they shipped to the group in Lebanon via third countries such as the UAE and South Africa.37 Also in 2009, prosecutors allege that Hezbollah dispatched Samer el Debek, an alleged U.S.-based Hezbollah operative, to Thailand to dispose of explosive precursor chemicals the group was stockpiling there because the group believed its Bangkok safe house was under surveillance.38 That same year, prosecutors allege, Ali Kourani, another alleged U.S.-based Hezbollah operative, traveled to Guangzhou, China, the location of a company that manufactured “the ammonium nitrate-based First Aid ice packs that were [later] “seized in connection with thwarted [Hezbollah Islamic Jihad Organization] IJO attacks in Thailand and Cyprus.”39 According to prosecutors, Ali Kourani and Samer el Debek were primarily tasked with carrying out preoperational surveillance for potential Hezbollah attacks in the United States and Panama. As previously mentioned, they alleged Debek was sent to Thailand to shut down a Hezbollah explosives lab, and that Ali Kourani was directed “to cultivate contacts in the New York City area who could provide firearms for use in potential future IJO operations in the United States.” Kourani was also reportedly tasked with obtaining surveillance equipment in the United States, such as drones, night-vision goggles, among other items.40

Unlike the case of Kourani and Debek, who are accused of being members of Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad Organization, most cases involved Hezbollah leveraging criminal fundraising enterprises to procure weapons for the group rather than assigning such tasks to more operational networks. Consider the July 2014 designation of brothers Kamel and Issam Amhaz and Ali Zeiter, who functioned as “a key Hezbollah procurement network,” according to the U.S. Treasury Department. Using a Lebanon-based consumer electronics business, Stars Group Holding, as a front for a variety of illicit activities, the network allegedly purchased technology around the world—in North America, Europe, Dubai, and China—to develop drones for Hezbollah.41 The U.S. Treasury Department press statement announcing this action noted that “Hezbollah’s extensive procurement networks exploit the international financial system to enhance its military capabilities in Syria and its terrorist activities worldwide” and underscored that this global terrorist and criminal activity was expanding.42 Indeed, an investigative report on sanctions evasion through the luxury real estate market revealed the Amhaz brothers’ extensive unsanctioned business empire, stretching from Lebanon to Hong Kong and from West Africa to North America.43

A particularly important arrest came in April 2014, when Czech authorities arrested alleged weapons dealer Ali Fayad acting on a U.S. arrest warrant. An alleged Lebanese-Ukrainian arms dealer with reportedly close ties to Hezbollah and Russia President Vladimir Putin, as well as Syria, Iran, and Latin American drug cartels, Fayad was the target of an elaborate sting operation.44 Hezbollah kidnapped several Czech citizens in Lebanon to secure Fayad’s release, and Putin put significant pressure on the Czech government as well, leading to his release and return to Lebanon in January 2016.45 The lengths to which Hezbollah went to secure his release indicated the importance it attached to him and his alleged procurement activities.

By early 2015, DEA investigations into Hezbollah narco-trafficking and money-laundering operations revealed some of the group’s weapons procurement efforts as well. The DEA dubbed the entity involved in these activities as the “Business Affairs Component” (BAC) of Hezbollah’s External Security Organization (its terrorist wing, also known as Islamic Jihad), which it said was founded by the late Hezbollah terrorist mastermind Imad Mughniyeh himself.46 The BAC is run by two key Mughinyeh deputies, DEA reported: Abdallah Safieddine and Adham Tabaja. Safieddine reportedly served as the group’s representative to Tehran, and is a cousin of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah.47 Tabaja was designated by the U.S. Treasury in June 2015. According to Treasury, Tabaja is a Hezbollah member who “maintains direct ties to senior Hizballah organizational elements, including the terrorist group’s operational component, Islamic Jihad.” Also according to Treasury, he provided financial support to Hezbollah through his businesses in Lebanon and Iraq.48 The reason Hezbollah was so deeply involved in the drug trafficking and money laundering schemes utilized by the BAC, according to then-DEA Acting Deputy Administrator Jack Riley, was to “provide a revenue and weapons stream for an international terrorist organization responsible for devastating terror attacks around the world.”49 In one case, the U.S. Treasury designated Hezbollah-linked Lebanese businessman Kassem Hejejj for working with Tabaja, providing credit to Hezbollah procurement companies, and opening bank accounts for Hezbollah in Lebanon.50

In a coordinated action on October 2015, U.S. and French law enforcement agencies arrested Joseph Asmar in Paris and Iman Kobeissi in Atlanta. U.S. authorities lured Kobeissi to the United States, where she allegedly informed an undercover DEA agent posing as a narcotics trafficker that her Hezbollah associates sought to purchase cocaine, weapons, and ammunition. Most telling, however, was their alleged desire to procure weapons and other materiel not only for Hezbollah but for Iran as well, as detailed by the U.S. Department of Justice:51

“Kobeissi also allegedly arranged to obtain firearms and heavy weapons for her associates in Hezbollah and other independent criminal groups in Iran. During recorded conversations between Kobeissi and the undercover DEA agent, Kobeissi stated that she had customers in Iran who would like to purchase a variety of firearms and blue prints for “heavy weaponry.” In one list Kobeissi provided to the undercover agent containing a request for firearms for her Iran-based customer, Kobeissi included an order for more than 1,000 military-style assault rifles, including M200 sniper rifles, M4 carbine rifles, and Objective Individual Combat Weapons, as well as 1,000 Glock handguns. In another communication, Kobeissi attempted to obtain thousands of handguns for her Hezbollah associates. In recorded conversations between Kobeissi and the undercover DEA agent, Kobeissi also discussed the potential for obtaining aircraft parts for her customers in Iran in violation of U.S. sanctions. In those recordings, Kobeissi can be heard stating that they had to hurry and obtain the aircraft parts while there were still sanctions against Iran so they could earn additional money for smuggling in the sanctioned parts.”52

In other words, Hezbollah procurement networks had matured to the point that Iran was seeking to leverage its ability to gain access to weapons and sanctioned goods for Iran’s own direct needs. In turn, Iran also took the opportunity to use Hezbollah networks to benefit some of its other proxies as well, including Houthi rebels in Yemen.

For example, in December 2015, the U.S. Treasury Department targeted more branches of Hezbollah’s procurement network, including alleged procurement agents Fadi Hussein Serhan and Adel Mohamad Cherri and their companies, as well as additional companies owned by the aforementioned Ali Zeiter, an alleged Hezbollah procurement agent who had been designated by Treasury in July 2014.53 Much of the procurement activities these individuals and companies were involved in related to obtaining sensitive technologies and equipment for Hezbollah’s UAV program—including using their companies as fronts through which they purchased electronic equipment from companies in the United States, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. In one case, Cherri allegedly specifically procured dual-use items in China to be sent to Yemen for use in Houthi improvised explosive devices (IEDs).54

Meanwhile, as Hezbollah’s role in the war in Syria deepened, the group increasingly leaned on its BAC to raise funds and procure weapons and ammunition for Hezbollah operatives deployed to Syria. In 2016, U.S. federal agents in Miami issued arrest warrants for three alleged Hezbollah BAC operatives: Mohammad Ahmad Ammar, Ghassan Diab, and Hassan Mohsen Mansour. According to an affidavit filed in this case, “intelligence gathered by DEA and its foreign counterparts shows that a significant form of Hezbollah funding for the purchase of weapons in the Syrian conflict comes from laundering drug money for Latin American cartels, most notably Colombia’s Oficina de Envigado …”55

Further evidence of the drug-weapons connection came in November 2018, when a Paris court convicted one of Diab’s Hezbollah money-laundering associates, Mohammad Noureddine, on charges of drug trafficking, money laundering, and engaging in criminal conspiracy to finance Hezbollah.56 The conviction of Noureddine—a “Hezbollah-affiliated money launderer”57— along with several others was the product of a joint operation carried out by the DEA in coordination with partners from seven foreign countries, which led to the arrest of Noureddine and 14 other individuals in France, Italy, Belgium, and Germany. Code-named Operation Cedar, the raids targeted Hezbollah operatives and criminal facilitators involved in a massive drug and money-laundering scheme.58 U.S. authorities would later reveal that proceeds from the Hezbollah drug and money laundering schemes of which Noureddine was a part were “used to purchase weapons for Hizballah for its activities in Syria.”59

In fact, when it came to Syria, Hezbollah combined its independent procurement efforts with those of Iran to build integrated and efficient weapons procurement and logistics pipelines to vastly expand Hezbollah’s international weapons procurement capabilities. The U.S. Treasury Department designated and exposed one of the most important alleged lynchpins in this network, Abd Al Nur Shalan, in July 2015. Shalan, a Lebanese businessman with alleged close ties to Hezbollah leadership, had “been Hezbollah’s point person for the procurement and transshipment of weapons and materiel for the group and its Syrian patrons for at least 15 years,” according to the Treasury Department.60 With his many years of alleged experience procuring weapons for both Hezbollah and the Assad regime, Shalan was well placed to play a critical role procuring weapons for Hezbollah in the context of the Syrian war. Even before Secretary General Nasrallah’s official acknowledgment that Hezbollah had entered the war in defense of the Assad regime, Shalan was at the center of efforts to make sure Hezbollah operatives in Syria were well armed. By 2014, once Hezbollah’s deployment to Syria was made official, authorities noticed that Shalan was using “his business cover to hide weapons-related material in Syria for Hezbollah.”61

According to the U.S. Treasury Department:

“Shalan has been critical in keeping Hezbollah supplied with weapons, including small arms, since the start of the Syrian conflict. Shalan ensures items purchased for Hezbollah personnel in Syria make it through customs. In 2014, Shalan used his business cover to hide weapons-related materiel in Syria for Hezbollah. In 2012, Shalan was involved in helping Hezbollah obtain weapons and equipment and in shipping the material to Syria. In 2010, Shalan was at the center of brokering a business deal involving Hezbollah, Syrian officials, and companies in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine regarding the purchase of weapons. Further in 2010, he acquired a number of tons of anhydride, used in the production of explosives and narcotics, for use by Hezbollah. In November 2009, Shalan coordinated with Hezbollah and Syrian officials on the purchase and delivery of thousands of rifles to Syria.”62

Given Shalan’s alleged background, it should not surprise that he is reported to be a close associate of Mohammad Qasir,63 the head of Hezbollah’s Unit 108 who served as a notetaker during President Assad’s meeting with Iran’s President and Supreme Leader.

Hezbollah’s Unit 108

Iran provides Lebanese Hezbollah with some $700 million a year, according to U.S. government officials.64 Above and beyond that cash infusion, Tehran has helped Hezbollah build an arsenal of some 150,000 rockets and missiles in Lebanon, far larger than the stockpiles of most sovereign states.65 Against the backdrop of the Syrian war, Iran has continued to smuggle weapons into Syria for transshipment to Hezbollah in Lebanon, leading Israel to carry out airstrikes targeting these weapons shipments.66 In response, Iran has now embarked on a “missile accuracy project” centered on providing Hezbollah GPS guidance kits that can increase the accuracy of the group’s missile arsenal.67 According to Israeli authorities, Hezbollah has already built underground missile production sites in Beirut and elsewhere, though these are reportedly still non-operational.68

Under the leadership of Bashar al-Assad, Damascus also began to provide weapons directly to Hezbollah, a shift in behavior from the more reserved relationship Syria maintained with Hezbollah under Bashar’s father, Hafez al-Assad. By 2010, for example, Syria was not just allowing the transshipment of Iranian arms to Hezbollah through Syria, but it was providing Hezbollah long-range Scud rockets from its own arsenal, according to U.S. and Israeli officials.69

Iran has used civilian airlines such as Mahan Air to transport weapons and personnel for Hezbollah, the Syrian regime, and other armed groups,70 and has helped Hezbollah build a sophisticated smuggling network to move these weapons from Syria to the Lebanese border and then to Hezbollah strongholds in Lebanon.71 These networks are also available to move weapons procured by Hezbollah’s own procurement efforts, such as those allegedly overseen by Abd al Nur Shalan and others.

The first link in the weapons transportation chain is Qasir’s Unit 108, which is responsible for moving weapons across Syria to the Lebanese border and then, together with Unit 112, transporting weapons across the border into Lebanon. (Another Hezbollah unit, Unit 100, runs a ratline in the reverse direction, from Lebanon to Syria to Iran, ferrying Hezbollah trainees to and from advanced training in the handling and use of the rockets delivered from Iran, like the Fateh-110.72)

Mohammad Qasir, also known as Hajj Fadi, is uniquely qualified to head a unit as sensitive and important as Unit 108. One of Qasir’s brothers, Hassan, is reportedly the son-in-law of Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah.73 Another brother, Ahmed Qasir, was the suicide bomber who carried out the November 1982 attack on an Israeli military headquarters in Tyre.74 Nasrallah referred to Ahmed as the “prince of martyrs” at a Martyrs Foundation event marking the anniversary of the attack.75

With his family legacy, Mohammad Qasir rose high and fast within Hezbollah, and remains a trusted confidant of Nasrallah, Shalan, Soleimani, and others despite charges of enriching himself, failing to protect weapons shipments from Israeli airstrikes, and infidelity.76 In May 2018, the U.S. Treasury Department designated Qasir as “a critical conduit” for Quds Force payouts to Hezbollah.77 Seven months later, the U.S. Treasury Department exposed another Iranian illicit financing scheme, using the Central Bank of Syria and benefitting both Hezbollah and Hamas, and revealed Qasir’s central procurement role as the head of “the Hezbollah unit responsible for facilitating the transfer of weapons, technology, and other support from Syria to Lebanon.”78 Also designated was designated was Mohammad Qasim al-Bazzal, described by the U.S. Treasury as an associate of Qasir and a Hezbollah member.79 In a letter to a senior official at the Central Bank of Iran, Qasir and a Syrian associate confirmed receipt of $63 million as part of a scheme to benefit Hezbollah.80 Then, in February 2019, Qasir appeared as a notetaker in photographs and video clips of Assad’s secret visit to Tehran.81

Conclusion

The fact that Hezbollah benefits from both Iranian largesse and its own procurement efforts is well documented. Canada’s Terrorist Financing Assessment for 2018 noted that “Hezbollah operates within a logistical and support structure that is both global in scope and highly diversified in nature.”82 Europol’s 2018 terrorism report highlights a major criminal money-laundering case in Europe in which “a share of the profits [were used] to finance terrorism-related activities of the Lebanese Hezbollah’s military wing.”83 The U.S. National Strategy for Combatting Terrorist and other Illicit Financing 2018 noted: “Hizbollah receives support from Iran and uses a far-flung network of companies and brokers to procure weapons and equipment, and clandestinely move funds on behalf of operatives.”84

As documented here, these include alleged formal Hezbollah procurement agents (Laqis, Dbouk, Amhaz, Cherri, Zeaiter, Serhan, Shalan) as well as alleged criminal and alleged illicit financial networks that are well positioned to expand into procurement activities due to their criminal contacts (Kobeissi, Asmar, Hejejj). They leverage alleged front companies (Stars Holdings, Vatech SARL85) and provide transshipment and smuggling services as well, whether for materiel Hezbollah procured on its own or received from Iran.

Analysts in and out of government debate why Hezbollah exposes itself to additional law enforcement scrutiny by carrying out procurement efforts of its own when it receives such general support—funds and weapons both—from Iran. Some alleged procurement efforts clearly grew out of alleged illicit financial schemes and were allegedly pursued simply because the opportunity presented itself (Operation Phone Flash, Kobeissi, Asmar), but allegedly others were pursued by Hezbollah proactively (Dbouk, Amhaz, Shalan). One reason for the latter appears to be Hezbollah’s search for sensitive technologies even more than small arms—according to the U.S. Treasury Department, Hezbollah-affiliated networks specifically “seek to procure sensitive or controlled goods from the United States.”86 Another reason Hezbollah carries out its own procurement efforts may be a demand among Hezbollah’s fighters for original Western-manufactured weapons rather than the Chinese or other knock-offs often provided by Iran. And then there are special circumstances, like the Syrian war, when the demand for weapons and ammunition is so immediate that efforts to procure materiel—both independently and through Iran—are dramatically increased.

By all accounts, Hezbollah continues to prioritize its need to replenish and build its weapons arsenals in the wake of the Syrian war, but faces severe difficulties doing so. As sanctions targeting Hezbollah and Iran take increasing effect, Hezbollah is feeling the pinch.87 Nasrallah himself recently lamented the impact of sanctions and publicly called upon Hezbollah’s members and sympathizers to donate funds to the group’s Islamic Resistance Support Organization (IRSO).88 The IRSO specifically raises funds for Hezbollah’s military activities, including its “Equip a Mujahid” fundraising campaign. The U.S. Treasury designated the IRSO in 2006 for its weapons procurement fundraising,89 but in the wake of sanctions targeting both Iran and Hezbollah, the group has renewed its IRSO procurement fundraising campaigns.90 Sanctions are also affecting Iran’s ability to smuggle weapons to its terrorist proxies, including Hezbollah. In February 2019, Panama expelled over 60 Iranian ships from its merchant marine registry, denying them the ability to sail under the Panamanian flag because authorities linked these ships to support for terrorist groups.91

As a result, the channels Hezbollah and the Quds Force have now created to move weapons through Syria to Hezbollah stockpiles in Lebanon are all the more critical to the group’s ability to procure and smuggle weapons into Lebanon. Mohammad Qasir’s appearance at Assad’s meetings in Tehran underscores not only the importance Hezbollah and the Quds Force attribute to Qasir and Unit 108, but the central role Assad’s Syria will continue to play in supporting Iran and Hezbollah’s militant agenda in the region so long as he remains in power. CTC

Dr. Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler fellow and director of The Washington Institute’s Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence. He has served as a counterterrorism official with the FBI and Treasury Department, and is the author of Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God. He has written for CTC Sentinel since 2008. Follow @Levitt_Matt

[3] Author interview, Western intelligence official, February 2019; see video posted on the official Twitter feed of the Presidency of the Syrian Arab Republic, “The president’s working visit today to the Iranian capital,” February 25, 2019.

[6] “Lebanese businessman jailed in Paris drug trial,” Times Live (South Africa), November 29, 2018.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “International Radical Fundamentalism: An Analytical Overview of Groups and Trends,” U.S. Department of Justice, Terrorist Research and Analytical Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, November 1994, declassified on November 20, 2008.

[10] United States of America v. Fawzi Mustapha Assi, Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division, U.S. District Court, Government’s Sentencing Memorandum, Criminal No. 98-80695, June 9, 2008.

[11] United States of America v. Fawzi Mustapha Assi, Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division, U.S. District Court, Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law Regarding Applicability of § 3A1.4 of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines, Criminal No. 98-80695, October 17, 2008.

[12] FBI 302 interview of Said Mohamad Harb, August 18, 2000, Case # 265B-CE-82188, p. 9.

[13] United States v. Mohamad Youssef Hammoud and Chawki Youssef Hammoud, June 10, 2002, Docket No. 3:00-cr-147, pp. 1,486-1,487.

[14] Robert Fromme and Rick Schwein, “Operation Smokescreen: A Successful Interagency Collaboration,” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 76:12 (2007): pp. 20-27.

[15] United States v. Mohamad Youssef Hammoud et al, “CSIS Summaries, Redacted Copy, Trial Testimony,” Docket No. 3:00-cr-147, p. 5.

[16] Matthew Levitt, “Why the CIA Killed Imad Mughniyeh,” Politico, February 9, 2015; Adam Goldman and Ellen Nakashima, “CIA and Mossad Killed Senior Hezbollah Figure in Car Bombing,” Washington Post, January 30, 2015.

[17] United States v. Mohamad Youssef Hammoud et al, “CSIS Summaries, Redacted Copy, Trial Testimony,” p. 22.

[18] “An Assessment of the Tools Needed to Fight the Financing of Terrorism: Hearing before Senate Committee on the Judiciary,” Western District of North Carolina, November 20, 2002 (Testimony of Robert J. Conrad, Jr).

[20] United States of America v. Riad Skaff, Government’s Sentencing Memorandum, No. 07CR0041, United States District Court, Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, May 27, 2008; United States of America v. Riad Skaff, No. 07CR0041, United States District Court, Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, January 29, 2007 (Affidavit of ICE Special Agent Matthew Dublin).

[21] United States of America v. Mahmoud Youssef Kourani, Government’s Written Proffer in Support of Detention Pending Trial, Crim. No. 03-81030, United States District Court, Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division, January 20, 2004; USA v. Mahmoud Youssef Kourani, Indictment, Crim. No. 03-81030, United States District Court, Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division, November 19, 2003; United States of America v. Sealed Matter, Affidavit of Timothy T. Waters.

[22] Nicholas Blanford, Warriors of God: Inside Hezbollah’s Thirty-Year Struggle Against Israel (New York: Random House, 2011), pp. 336-339.

[23] Nada Bakri, “Hezbollah Leader Backs Syrian President in Public,” New York Times, December 6, 2011.

[24] Author interview, law enforcement officials in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 2010.

[25] Ibid.; “Arrests Made in Case Involving Conspiracy to Procure Weapons, Including Anti-Aircraft Missiles,” United States Department of Justice, Press Release, November 23, 2009; United States of America v. Dani Nemr Tarraf et al, Indictment, Crim. No. 09-743-01, United States District Court, Eastern District of Pennsylvania, November 20, 2009.

[26] Author interview, law enforcement officials in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 2010.

[27] Ibid.; “Arrests Made in Case Involving Conspiracy to Procure Weapons;” United States of America v. Dani Nemr Tarraf et al, Indictment and Criminal Complaint, Crim. No. 09-743-01, United States District Court, Eastern District of Pennsylvania, November 20, 2009.

[28] United States of America v. Dani Nemr Tarraf et al, Pretrial Detention Order.

[29] Spencer Hsu, “Hezbollah Official Indicted on Weapons Charge,” Washington Post, November 25, 2009; “Sayyid Nasrallah, Hamas Call for Resumption of Lebanese-Palestinian Dialogue,” Al Manar TV, December 2, 1999 (supplied by BBC Worldwide Monitoring); Stewart Bell, “10 People Charged with Supporting Hezbollah,” National Post (Canada), November 24, 2009; author interview, law enforcement officials in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 2010; United States of America v. Hassan Hodroj et al, Affidavit Samuel Smemo, Jr.

[30] United States of America v. Hassan Hodroj et al, Affidavit Samuel Smemo, Jr.

[31] Ibid.

[33] Matthew Levitt, “Hezbollah: Party of Fraud,” Foreign Affairs, July 27, 2011.

[34] This observation is based on the author’s discussions with current and former U.S. government officials tracking Hezbollah over the past decade.

[38] United States v. Samer El Debek, Affidavit in Support of Warrant to Arrest, United States District Court, Southern District of New York, May 31, 2017.

[39] United States v. Ali Kourani, Affidavit in Support of Warrant to Arrest, United States District Court, Southern District of New York, May 31, 2017; United States of America v. Samer El Debek, Affidavit in Support of Warrant to Arrest.

[40] United States v. Ali Kourani, Affidavit in Support of Warrant to Arrest.

[42] Ibid.

[44] Josh Meyer, “The Secret Backstory of How Obama Let Hezbollah Off the Hook,” Politico, December 2017.

[46] “DEA and European Authorities Uncover Massive Hizballah Drug and Money Laundering Scheme.”

[47] Meyer.

[49] “DEA and European Authorities Uncover Massive Hizballah Drug and Money Laundering Scheme.”

[50] “Treasury Sanctions Hizballah Front Companies and Facilitators in Lebanon And Iraq.”

[52] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] DEA Special Agent Kenneth Martin, “Affidavit in Support of Arrest Warrant,” Circuit Court of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in and for Miami-Dade County, Florida, [date unspecified on the document] 2016.

[56] “Lebanese businessman jailed in Paris drug trial.”

[58] “DEA and European Authorities Uncover Massive Hizballah Drug and Money Laundering Scheme.”

[59] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] “Exposed: the head of Hezbollah’s Unit 108 responsible for smuggling the Iranian missiles from Syria to Lebanon,” Intelli Times (Israel), February 16, 2018. A Western intelligence official confirmed the information in question to the author in February 2019.

[66] Ehud Yaari, “Bracing for an Israel-Iran Confrontation in Syria,” American Interest, April 30, 2018.

[68] Ibid.

[71] “Exposed: the head of Hezbollah’s Unit 108 responsible for smuggling the Iranian missiles from Syria to Lebanon.”

[73] “Exposed: the head of Hezbollah’s Unit 108 responsible for smuggling the Iranian missiles from Syria to Lebanon.”

[74] “Hezbollah,” Mapping Militants Project, Stanford University, August 5, 2016.

[75] “Hizbullah SG Speech on 11-11-2007,” Al-Ahed News (Lebanon), November 11, 2007.

[76] “Exposed: the head of Hezbollah’s Unit 108 responsible for smuggling the Iranian missiles from Syria to Lebanon.”

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid.

[81] See video posted on the official Twitter feed of the Presidency of the Syrian Arab Republic, “The president’s working visit today to the Iranian capital,” February 25, 2019.

[82] “Terrorist Financing Assessment: 2018,” Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada, 2018.

[83] “European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TESAT) 2018,” Europol, 2018.

[84] “National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing: 2018,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2018, p. 46.

[85] “Treasury Sanctions Hizballah Procurement Agents and Their Companies.”

[86] “National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing,” p. 26.

[88] “Nasrallah: Resistance needs support because we are in the heart of the battle,” An-Nahar (Lebanon), March 8, 2019.

Skip to content

Skip to content