Abstract: Israel is known for its capable military, security, and intelligence services, which actively patrol and protect the country’s borders. And yet, Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian officials report that the smuggling they have detected across Israel’s borders with Jordan and Egypt—mostly involving drugs or guns—has increased significantly over the past two years, with major consequences for both the public health and public security of Israel. This is despite peace treaties with both Jordan and Egypt and parallel efforts on the part of those countries to patrol their sides of the border. Building on the assessments of Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian officials, this study draws on a dataset the authors compiled of 105 cases of identified, thwarted, or disrupted weapons or drug smuggling attempts into Israel from March 2021 through April 2023 across all of Israel’s borders. The study focuses on the borders Israel shares with Jordan and Egypt, where disruptions of smuggling operations increased during this period.

In August 2022, the IDF reported there had been a “significant rise” in detected attempts to smuggle weapons and drugs into Israel from Jordan and Egypt, pointing to the more than 300 weapons and 2,150 kilograms of various drugs seized since the beginning of the year.1 In late 2022, an Israeli official confirmed to the authors that detected smuggling attempts across Israel’s borders had increased in recent years.2 As will be outlined, a database maintained by the authors finds that detected smuggling attempts into Israel rose between early 2021 and early 2023.

Does this mean that smuggling at Israel’s borders is becoming a greater challenge? Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian officials interviewed by the authors independently reported that it has, both in terms of an increase in known smuggling cases and in the complexity of smuggling operations and the dangers of addressing the challenge. The authors further believe it is reasonable to infer from the growth in detected smuggling activity that more smuggling is taking place, but this cannot be assumed with certainty.a It is also important to put the recent heightened smuggling challenges into context by considering historical data. For example, as will be noted later, when it comes to the number of detected smuggling attempts along Israel’s border with Egypt, despite the recent rise in cases, the levels remain lower than at their peak in 2019-2020, according to IDF data relayed to the authors.

The guns and drugs that are flowing into Israel are creating societal problems and public safety issues. The influx of weapons is also a major counterterrorism concern. Smuggled weapons have been a contributing factor to the surge of violence that has plagued the West Bank and Israel.3 Consider the December 2022 case when Israeli authorities arrested brothers Mohammed and Adam Abu Taha, residents of a Bedouin town near Beer Sheva in Israel’s Negev desert, on charges of smuggling weapons and ammunition. The brothers knowingly sold the weapons to members of Palestinian Islamic Jihad in the West Bank and to criminals in southern Israel.4

Indeed, this increased arms smuggling5 occurred against the backdrop of over a year and a half of violence that began with an 11-day battle between Israeli forces and Hamas in May 2021 and continued through a string of terror attacks in the spring of 2022 that prompted a sweeping Israeli military campaign with nightly West Bank raids targeting terrorist operatives.6 In July 2023, Israeli forces carried out an operation targeting militant facilities and weapons depots in Jenin, focusing in particular on the Jenin Brigades of the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Alongside the extensive collection of chemical materials to make explosives and hundreds of assembled explosive devices seized, authorities also found thousands of rounds of ammunition and weapons such as M-16s, pistols, and shotguns.7

Of the 472 terrorist attacks foiled by Israel security forces in 2022 in the West Bank or Jerusalem, 358 were shooting attacks, underscoring the centrality of small arms smuggling to this spike in violence.8

This study assesses the smuggling problem set facing Israel on its borders with Jordan and Egyptb by drawing on the authors’ dataset of 105 cases of identified, thwarted, or disruptedc weapons or drug smuggling attempts into Israel from March 2021 through April 2023 across all of Israel’s borders.

This article first describes the authors’ dataset and then makes some big picture observations. The study then focuses in turn on smuggling attempts at the borders Israel shares with Jordan and Egypt, where authorities on both sides of the border report a significant increase in detected smuggling activity has taken place in the past two years. In looking at the challenges at both borders, this article outlines what, as far as is known, is being smuggled, where smuggling attempts occur, and the impacts on Israel’s security and public safety.

The Dataset

The authors’ dataset consists of 105 cases of identified, thwarted, or disrupted weapons or drug smuggling attempts into Israel from March 22, 2021, through April 22, 2023 (the period over which the authors collected the data), primarily across the Jordanian and Egyptian borders (87) but also (18) across the de facto borders with Lebanon and Syria. It is important to stress that the approximately two-year time duration means that their data sheds light on recent and what may only be short-term trends.

The dataset draws from IDF and Israeli government press releases, news articles, and information gleaned from meetings with Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian government officials.9 The research also benefited from field research trips to smuggling hotspots along Israel’s borders with Jordan and Egypt during which the authors spoke to officials involved in border security and counter-smuggling operations.10

The dataset is, by definition, not comprehensive because it is limited to information that is either publicly available in media reports or IDF press releases or that could be gleaned from documents shared with the authors and author interviews. Indeed, officials confirmed that not all smuggling cases that are identified, thwarted, or disrupted by authorities (on either side of the border) are publicized, adding that there are plenty of successful smuggling operations that authorities learn about after the fact (these are typically not reported publicly, and are therefore not generally represented in the authors’ dataset).11 Therefore, the authors also provide the reader with summary data drawn from IDF sources when those have been made available, such as in media reports or the IDF’s annual report.

Publicly available data does not uniformly report the details of each smuggling operation. For example, the types of detail provided in reports varies regarding the specific locations where smugglings take place, the identities of those involved, and even the quantities of contraband smuggled. Any quantity of drugs smuggled is especially difficult to quantify over time, as reports sometimes describe the amount of drugs seized by estimated cash value and other times by weight. Despite these constraints, the dataset tracks available information regarding event location, perpetrator identity, and smuggled items (almost always weapons or drugs, but several cases involve money or gold).

What Authorities Say

Indeed, while the dataset is not an exhaustive list of each smuggling attempt during the March 2021 to April 2023 time period, the overall numbers in the dataset are nearly identical to those reported by Israeli authorities. (Neither Jordanian nor Egyptian authorities provided overall figures to the authors.) Israeli authorities confirmed to the authors the trendlines accurately reflect those observed by national counter-smuggling authorities.12 Israeli officials periodically release overall numbers regarding the scale and scope of smuggling operations across their borders. Where available, the authors provide these numbers for greater context.13

Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian authorities all report significant increases in known cross-border smuggling between early 2021 and early 2023. These governments have access to far more detailed data than they make public and than that which is included in the author’s dataset, and they are therefore well-positioned to make such an assessment. The actual pace of known smuggling fluctuates from month to month, but authorities in these countries report that the overall trendlines point up during the past two years.

The Big Picture

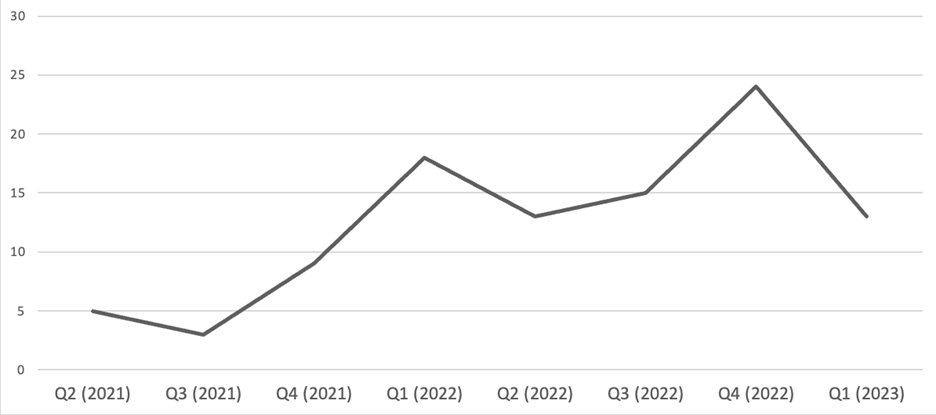

Overall, according to the authors’ dataset, the number of identified, thwarted, or disrupted attempts to smuggle drugs or weapons into Israeli territory—mostly from Jordan and Egypt—increased during the course of 2021 and 2022. (See Figure 1.d) Looking across Israel’s various borders, the number of identified, thwarted, or disrupted smuggling attempts shot up from three in the third quarter of 2021 to 23 in the fourth quarter of 2022.15

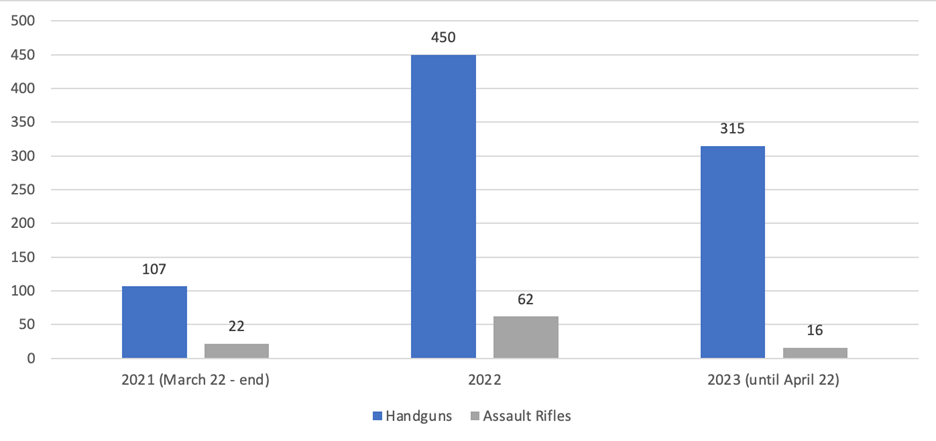

In August 2022, the IDF reported there had been a “significant rise” in detected attempts to smuggle weapons and drugs into Israel from Jordan and Egypt, pointing to the more than 300 weapons and 2,150 kilograms of various drugs seized since the beginning of the year.16 Comparatively, 300 weapons were seized in 2020 and 2021 combined.17 Similarly, the authors’ dataset shows a stark increase in the number of weapons intercepted at the border from 2021 to 2022, with an even higher figure per month in 2023 for the period up until April 22. (See Figure 2.)

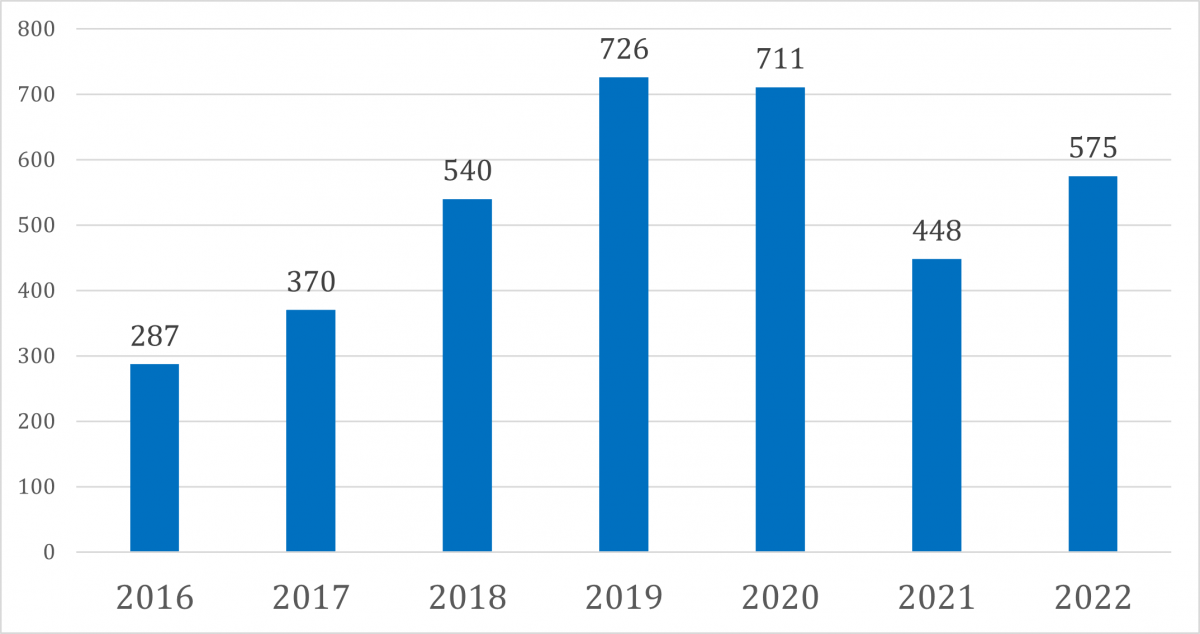

Israeli forces embarked on a concerted anti-smuggling campaign in 2018 alongside efforts by Egyptian and Jordanian counterparts. According to the IDF, the number of identified, thwarted, or disrupted smuggling attempts along the Egyptian border increased from 448 in 2021 to 575 in 2022.18 According to the IDF, both 2019 and 2020 saw more than 700 identified, thwarted, or disrupted drugs smuggling attempts along the Egyptian border, a higher number than in the past two years. (See Figure 4.)

Others point to changed circumstances to explain what they see as an ongoing threat from cross-border smuggling, even as the number of known smuggling attempts began to drop in early 2023 (Figure 1).19 For example, the cumulative tolls of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine put Israel and its neighbors under significant economic stress, creating an environment ripe for illicit activity.e As lockdowns kept civilians out of work and shrank the number of available jobs, parallel gray and black job markets grew. Due to the lack of other opportunities, more people were drawn into the growing smuggling industry.20 According to the IDF, Israeli Bedouin smugglers can make a profit of around $50,000-$70,000 from one smuggling operation, and Egyptian smugglers can earn $25,000-$35,000.21 Such lucrative opportunities enable smuggling rings to offer attractive salaries to those struggling to find a job. Because of these circumstances, authorities expect cross-border smuggling to remain an ongoing challenge.

Gun-Running Across the Israeli-Jordanian Border

On a Saturday evening in April 2023, Israeli authorities arrested Jordanian Member of Parliament (MP) Imad al-Adwan at the Allenby Bridge border crossing for attempting to smuggle over 200 guns into the West Bank. Subsequent investigation revealed that the Jordanian lawmaker reportedly carried out a dozen earlier smuggling runs starting in early 2022. In each, he leveraged his diplomatic passport to smuggle illicit goods: namely guns, electronic cigarettes, gold, and birds.22 Despite MP al-Adwan’s membership in the Jordanian Parliament’s Palestine Committee and his past statements in support of Hamas,23 the primary driver for al-Adwan’s smuggling activities was financial rather than in support of any Palestinian militant group, according to Israel’s Shin Bet internal security service.24

This incident stood out both for the number of weapons smuggled and the fact that a parliamentarian was used to drive them across an official border crossing at the Allenby Bridge into the West Bank. Most smuggling attempts from Jordan involve criminal smuggling networks that span the Israeli-Jordanian border using members of Bedouin tribes as runners to deliver illicit goods to and across the border, typically at isolated portions of the border far from official border crossings.25

Israeli and Jordanian officials report that the level of arms smuggling from Jordan into Israel and the West Bank has increased over the past two years, in terms of what is being detected.26 This increase is also reflected in the authors’ March 2021 to April 2023 database.

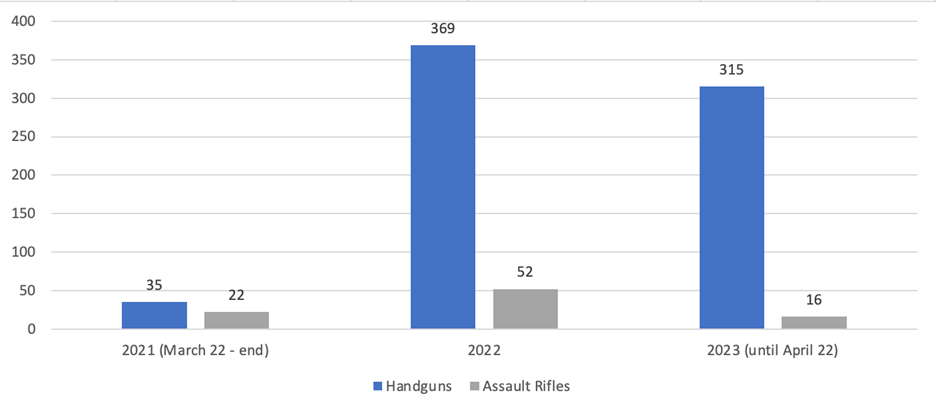

As already noted, more detected smuggling is likely indicative of more smuggling getting through, and this appears to have fueled instability and a surge in terrorist and other violent activity. According to the authors’ database, from March 2021-April 2023, at least 35 smuggling attempts and 951 weapons (809 handguns and assault rifles, plus grenades and other weapons) were discovered and seized by Israeli police. (Figure 3).f These numbers include 22 thwarted smuggling attempts from Jordan in 2022 alone compared to four thwarted in 2021. According to summary data provided in the IDF’s 2022 Annual Data Report, the number of smuggled weapons seized at or near the Jordanian border jumped to approximately 570, a large quantity compared to 239 seized at Israel’s borders with Lebanon and Syria27 g and the estimated zero weapons smuggled from Egypt that same year.28 Aligning with the authors’ data, Jordanian authorities have reportedly thwarted over 20 smuggling plots, most involving 9mm handguns, over the past three years.29

As already noted, many smuggling plots on both sides of the border are not publicly reported. Weapons smuggling benefits both terrorist and organized criminal groups but is primarily driven by criminal smuggling networks that recruit members of Bedouin tribes to help facilitate their smuggling operations. Jordanian authorities report that drug smugglers in southern Syria also recruit Jordanian Bedouins to work with Shi`a militias tied to Iran and smuggle drugs—mostly Captagon—from Syria into Jordan.30

According to Jordanian officials, cross-border smuggling incidents as of late 2022 were occurring about once or twice a week.31 Israeli officials also concede they neither stop nor even necessarily know about every smuggling attempt: “At the Jordanian border, the border is so long that we know smuggling events take place when we catch them, but IDF Bedouin trackers often tell us that more cross-border incidents happen that we don’t know about until after the fact. And there are likely more still that we never find out about.”32 Israeli authorities refer to these as “black smuggling operations” where smugglers go “black” and trackers only find evidence after the fact.33

The Jordanian border spans the geographic areas of responsibility of three IDF commands (north, central, and south), requiring robust coordination within the Israeli military to address security concerns. While the Jordanian military is fairly well-deployed along its side of the border, the Israeli military is more sparsely deployed along large portions of the border since the terrorism threat is comparatively lower there than in other parts of the country. This results from the 1994 Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty and the area’s sparse population.34 On the Israeli side, increased counter-smuggling efforts have yielded success, including surveillance cameras monitoring the Israel-Jordan border, undercover police operations, daily border patrols, and a joint operations center run by the IDF, Shin Bet, and Magen, the Israeli Police’s anti-smuggling unit.35

Cases along the Jordan-Israel border mostly involve weapons smuggling attempts conducted by West Bank Palestinians and Israeli-Arabs from Bedouin communities in the Negev desert and their counterparts on the Jordanian side of the border, many of whom come from the same Bedouin tribes.36 Criminal smuggling organizations recruit members of these tribes across borderlines who then pass goods to fellow tribesmen on the other side of the border, saving smugglers from having to cross the border themselves.37 Based on the data gleaned from incidents when arrests are made on the Israeli side of the border, the smuggling operatives along the Jordanian border tend to work in small groups of one to three people.38

What Is Smuggled, and Where?

The Israeli-Jordanian border runs over 400 km from the Golan Heights and along the West Bank to the ports of Eilat and Aqaba, making it Israel’s longest border. Significant portions of the Israeli border security fence in the south are old, lacking the more sophisticated technology featured in Israel’s newer border fences. In some spots along the long and sparsely populated southern desert border, there is no security fence at all, just barbed wire. Along that stretch of border, the commander of the IDF’s Jordan Valley 41st battalion told The Jerusalem Post that border penetrations are easy. “This area, the whole Jordanian border, is the easiest to breach. Here you can dig under, or simply cut a hole.”39 However, as one approaches the southern city of Eilat, a 30-km sophisticated border fence with sensors has been constructed.40

Along certain parts of the border, smugglers benefit from the region’s topography, which presents serious challenges to effective border surveillance. South of the Dead Sea, the Arava desert (Wadi Araba) is barren and flat. Smuggling succeeds here because the border is too long to effectively patrol and the area is a sparsely populated wilderness. North of the Dead Sea, the Jordan Valley is a rollercoaster of small hills running along the Jordan River marking the borderline between Israel and Jordan. “These hills cause us dead areas because of all the small channels,” a local Israeli commander told The Times of Israel. “It’s impossible to control. I can’t put a soldier on each peak.”41 Even from the best vantage points, he noted, one cannot see what is happening in each channel along the river’s floodplain, where natural berms and ditches create blind spots that allow smugglers to evade surveillance cameras and patrols.42

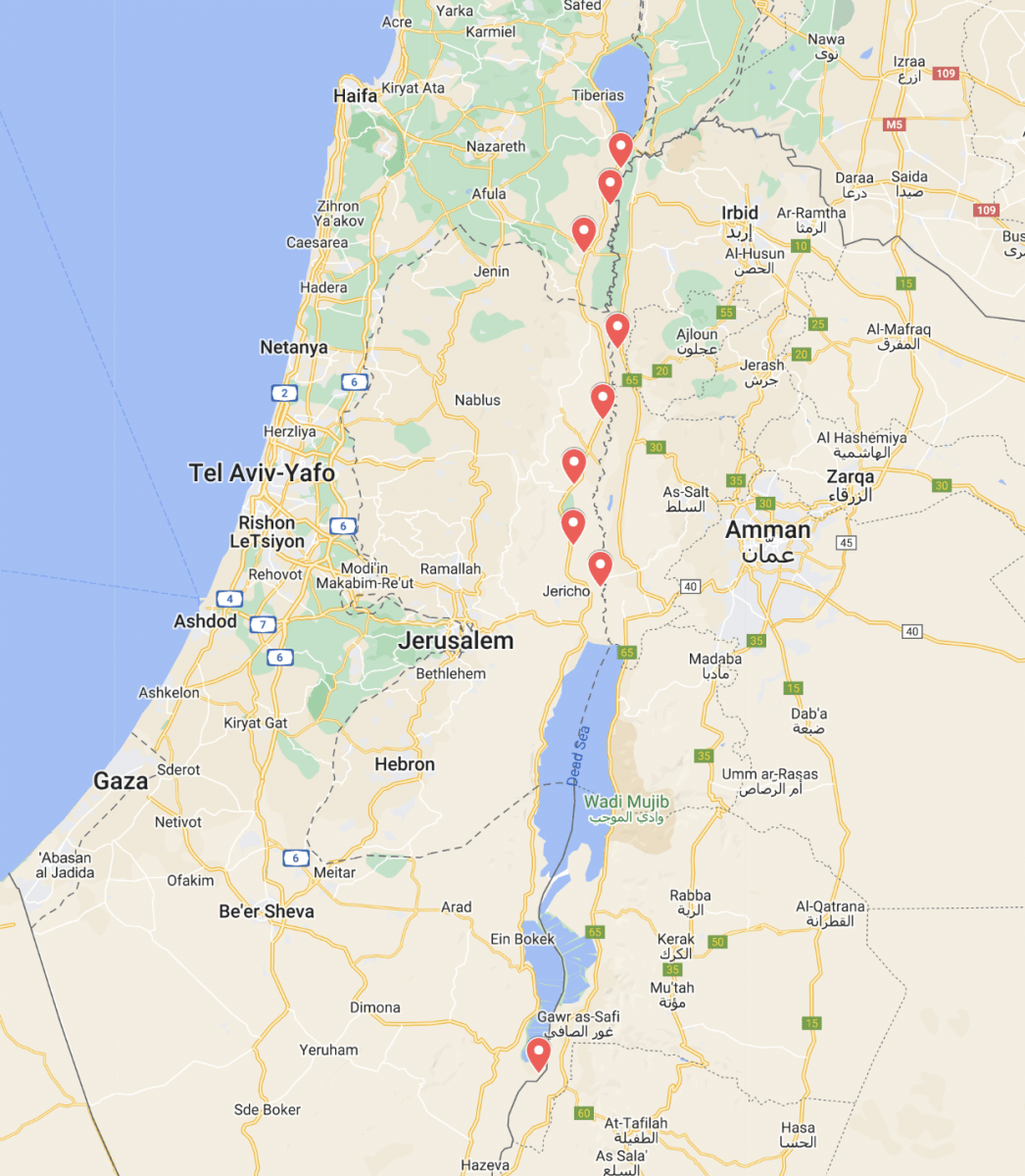

The authors’ dataset includes nine smuggling attempts from the area around Jericho in the West Bank, just north of the Dead Sea to the northern border of the West Bank, and another eight smuggling attempts into Israel directly from the Beit She’an area to Hamat Gader, south of the Sea of Galilee. There are another 17 attempts that occurred in the “Jordan Valley” or “along the Jordanian border,” but it is unclear where exactly these incidents took place. The few smuggling attempts that did not occur within these aforementioned boundaries occurred south of the Dead Sea (Map 1).43

As noted earlier, Jordanian MP al-Adwan allegedly attempted to smuggle three bags of weapons across the Allenby Bridge, including some 200 handguns and about a dozen AR-15 style assault rifles.44 This represents a significantly greater scale of ambition beyond past smuggling plots. On average, weapons busts along the Jordanian border include roughly 15 handguns and one or two assault rifles.45 Although there have been larger cases, no known public cases have matched the scale of MP al-Adwan’s various smuggling runs. Only after his arrest did authorities learn that starting in February 2022, the Jordanian parliamentarian allegedly made a dozen smuggling runs moving a variety of contraband across the border.46

In April 2023, Israeli police confiscated 63 handguns and arrested a Bedouin Israeli citizen suspected of smuggling weapons from Jordan.47 At the time, this was the largest-ever capture of weapons smuggled from Jordan. Earlier, in December 2022, Israeli authorities arrested two Israeli Bedouin brothers and a Palestinian from the northern West Bank on charges of smuggling weapons and ammunition that was then sold to members of the Palestinian Islamic Jihad in the West Bank and criminals in southern Israel.48 According to Israeli prosecutors, the brothers knowingly sold weapons to the terrorist group—including around 150,000 rounds of ammunition, dozens of weapons parts, and hundreds of M-16 rifles—noting that they met with Palestinian Islamic Jihad operatives on a regular basis over an extended period of time.49

The overwhelming majority of smuggled weapons coming in through Jordan are handguns, which account for about 90 percent of smuggled weapons seized at or near the Jordan-Israel border, according to the IDF.50 Many of the seized handguns are produced by Delta Defence Group,51 which has reportedly flooded the markets in Syria and Iraq in recent years, according to weapons research group Silah Report.52 The commander of Magen reports weapons dealers in Syria and Iraq enter into business deals with counterparts in Jordan who hire Jordanian smugglers to move guns into Israel and the West Bank.53 They have no problem selling these weapons to terrorists or organized criminals, but they themselves are criminals driven by profit rather than violent extremist ideology.54

Not all reported smuggling cases fully document what weapons were seized at or near the Jordan-Israel border, but collating the data from those that do reveals over 951 weapons were seized from March 2021 to April 2023, including 719 handguns and 90 assault rifles. Without providing details other than the total number of weapons seized per year, the IDF reported in May 2023 that 143 were seized in 2021, 508 in 2022, and 342 in the first five months of 2023 (not including weapons parts, which appear in about 50 percent of smuggling runs).55 Over the same time period, Jordanian authorities reportedly seized 70 weapons in 2021, 100 in 2022, and 30 in the first five months of 2023.56

The other 10 percent of guns smuggled across the Jordan-Israel border are M-16 and AK-47 style assault rifles and shotguns, officials report.57 Just a few years ago, most guns used in terror attacks in Israel and the West Bank were homemade “Carlo” submachine guns assembled in the West Bank.58 Today, journalists regularly document West Bank militants roaming the streets with proper assault rifles. Many of these are stolen from IDF armories or sold on the black market by IDF soldiers,59 but some are also smuggled into the country from Jordan. The authors’ dataset includes 14 smuggling cases involving large weapons (M-16s, AK-47s, and shotguns) that were intercepted or detected.60 IDF officials state that, along with M-16 and AK-47 style assault rifles, authorities have also seized a small number of shotguns at or near the Israel-Jordan border.61 These types of weapons (M-16s, AK-47s, and shotguns), Israeli authorities maintain, almost always end up in the hands of terrorists.62

The other commodity most being smuggled across Israel’s borders is drugs. In fact, one reason Israeli officials believe they have had more success thwarting arms smuggling from Jordan is an intelligence collection shift from drugs to guns. Another reason is the IDF’s decision to have Jordan Valley-based units focus more time and resources on patrolling the Jordanian border rather than the West Bank.63 Of the 35 documented smuggling cases along this border, 33 involved weapons, three involved unspecified drugs valued at $1.2 million total, and two involved the movement of cash (80,000 Jordanian dinar) or gold (unspecified amount).64

The precise location of each smuggling operation from Jordan is often unknown. Both government press releases and media reports identify where arrests take place, which is typically near the border, but not where the actual cross-border smuggling occurred. As a result, some of the locations tracked in the authors’ dataset are located a few kilometers from the border and some are listed only as “Jordan Valley.” The vast majority of the smuggling attempts from Jordan occurred along the border north of the Dead Sea and south of the Sea of Galilee, either crossing directly into the northern West Bank or into Israel between the area around Beit She’an and north to Hamat Gader.65 Some smuggling locations are recurring, though new ones appear each month, according to an IDF official involved in counter-smuggling efforts.66

Rarely do smugglers cross the border themselves, instead preferring to come up to the border fence and either throw bags of weapons over the fence or leave them there for someone on the other side to pick up after cutting a hole in the fence. In other cases, smugglers deposit bags of weapons or other contraband at a prearranged drop site in the narrow ‘no-man’s-land’ that lies between the Jordan River border and the Israeli border fence set back from the river. At some points, the space between the border and the fence can be as wide as 100 meters. Smugglers then cut through the security fence, retrieve the weapons from the ‘no-man’s-land,’ and supply the weapons to arms dealers.67

Impact on Security and Public Safety

Jordan’s Interior Minister Salameh Hammad has attributed the sharp rise in illegal weapons to the civil war in neighboring Syria.68 The increase was spurred by both the influx of guns from places such as Iraq and the growth of narcotics-smuggling networks in southern Syria, which often also smuggle guns into Jordan.69 Many of these smuggling routes became much harder to patrol as jihadi groups and, later, Syrian regime forces controlled the Syrian side of Jordan’s northern border.70 The flow of Captagon pills from Syria into Jordan has been widely reported, but weapons flow along these routes as well, with the drugs destined for the Gulf and the guns for the West Bank and Israel.71

In July 2022, Jordanian armed forces thwarted an attempt to smuggle 54 handguns, five shotguns, and ammunition from Syria.72 Because the Jordanian market is saturated with easily obtainable small arms, weapons are now being smuggled to Israel and the West Bank, where demand is high. Small arms reportedly cost about $2,000 apiece in Jordan, but sell for about $5,000 in the West Bank.73 According to a report from November 2022, a bullet for an M16 previously cost as little as about 85 cents in the West Bank, but by late 2022 cost about $5.50.74 In February 2023, an illegal gun dealer in East Jerusalem told The Washington Post that 9mm bullets were selling on the black market for as much as $10 apiece and handguns were running $13,000 to $23,000 depending on the type, condition, and age.75 In contrast, the same weapon could be legally bought in Israel for around $1,350 if one has a weapons license.76

The sharp increase in prices appears to be a function of both the impact of counter-smuggling efforts, which have put some constraints on the supply of weapons and ammunition, and continuing high demand for weapons in Israel and the West Bank. In fact, demand is so high that guns are often smuggled across the border before buyers are lined up.77 Militant groups in the West Bank have been especially active, including new groups unaffiliated with Hamas or Palestinian Islamic Jihad and without access to these groups’ arms caches. As the February 2023 terrorism wave spread, applications for gun licenses by Israelis spiked by 400 percent.78 Increased crime in Israel has led to increased demand for weapons among criminal syndicates and civilians seeking the means to protect themselves. In 2023, 51 Israeli-Arabs were reportedly killed by organized criminal gangs in Galilee, the so-called Triangle bordering the northern West Bank and the Negev.79 As one East Jerusalem gun dealer told The Washington Post, “Guns are everywhere. You want a gun? You can buy a gun in an hour. You can buy a handgun. They’re not cheap. You can even buy a machine gun, an assault rifle. They’re very expensive. But demand is very high. So it is a very good business.”80

Israeli organized criminal networks are another source of violence and instability in the West Bank. In 2022, seven criminal gangs were active in Arab communities, and over 104 Palestinians were killed by organized gangs.81 Consequently, the demand for arms in the Arab community has risen because of unsafe conditions and easy access to weapons.

The influx of guns has factored in the sharp increase in terrorist activity in the West Bank. West Bank militants increasingly walk the streets openly brandishing M-4s, M-16s, and CAR-15 style rifles.82 As early as 2019, there were reports that militants tied to Fatah Tazim were purchasing weapons that had been smuggled through Jordan from Syria.83 While most of these weapons are smuggled for profit without prejudice as to who purchases them, Iran has publicly claimed responsibility for some undetermined percentage of the weapons flow.84 In August 2022, Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commander Major General Hossein Salami stressed the importance of supporting Palestinians engaged in jihad against Israel, adding that just as Iran managed to send weapons to Gaza in the past, “the West Bank can be armed in the same way, and this process is happening.”85 General Salami continued on to praise the “unseen hands” getting weapons to Palestinians in the West Bank.86

Smuggled weapons are flowing in from Jordan, but that is by no means the only source of black-market arms. Another problem is organized weapons and ammunition theft from IDF bases and the homes of IDF soldiers. In November 2022, for example, thieves stole approximately 70,000 bullets and 70 grenades from an IDF base in the north of the country.87 Although this is a notable problem, there have only been around 10 reported cases of weapons stolen from IDF bases between January 2021 and April 2023.88 Overall, the IDF reported a downward trend in such thefts as base inspections increased,89 but weapons stolen from the IDF remain a primary source for assault rifles on the black market. An Israeli think tank found that between the weapons stolen from IDF bases and those smuggled through areas controlled by the Palestinian Authority, there are tens of thousands of illegal weapons in Israel’s Arab communities.90

Drug Smuggling Across the Egypt-Israel Border

On February 5, 2023, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and Israel Police foiled an attempt to smuggle $14 million (NIS 50 million) in drugs from Egypt by vehicle. Israeli forces confiscated 92 kg of heroin and cocaine and 28 kg of hashish from the vehicle. Bedouin smugglers in the Negev typically traffic marijuana and hashish grown in the Sinai Peninsula. In rare cases like this one, harder drugs such as cocaine and heroin have been smuggled as well.91 From November 2022 to May 2023, authorities identified, thwarted, or disrupted 18 known smuggling attempts along the Egyptian border, seizing over 717 kg of drugs.92 h

Smuggling along Israel’s southern border with Egypt has also been a problem, though the number of detected smuggling attempts along this border has fallen since its peak in 2019-2020. Here, drugs are the primary illicit commodity smuggled across the border. The year 2022 saw an increase in attempted drug smuggling operations, according to the IDF, which reported approximately 800 “operational incidents’’ along Israel’s various borders (a term that appears to include the 575 detected smuggling incidents and other, related ‘operational incidents’)—marking a significant increase from 2021.93 The number of reported drugs smuggling attempts across the Egyptian border has steadily increased over several years, from 287 cases in 2016 to a peak of 726 cases in 2019, according to Israeli figures, before dropping significantly in 2021 and partially rebounding in 2022. (See Figure 4.) Israeli authorities said that, as of late 2022, there were typically one to two smuggling attempts a day along this border.94

While some reports imply that the increase in drug smuggling is tied to terrorism,96 evidence suggests otherwise.97 Hamas has long smuggled weapons from Iran to the Gaza Strip via Sudan and the Sinai.98 This study, however, focuses on smuggling along the Egyptian-Israeli border, not from Egypt directly into Gaza. Only in a small number of cases have terrorist groups engaged in smuggling operations along Israel’s border with Egypt. The authors’ dataset includes two such cases involving Hamas, one on land and one by sea, both involving weapons and equipment; but the overwhelming majority of smuggling is carried out by criminal organizations.99 Israeli authorities assess that neither Hamas in the Gaza Strip nor Islamic State-Sinai has pursued smuggling drugs into Israel as a means of making money. Iran, they assess, has not done so either.100

As in Jordan, smugglers in Egypt and Israel largely come from the Bedouin tribes that span the countries’ borders. Israeli and Egyptian authorities point to increased identified, thwarted, or disrupted drug smuggling from 2016-2020101 (Figure 4), which is the result of several factors including long-term neglect by the Egyptian government and rampant unemployment. In 2013, a tribal leader pointed to unemployment as the primary driver behind crime and violent extremism in the Sinai.102 Even jobs tied to smuggling goods from Sinai into Gaza dwindled over time. Egypt flooded tunnels under the popular Rafah crossing, collapsing the tunnels and the illicit economy they created.103 For many, this left two options: either joining tribal militias being paid by the government to fight the Islamic State or joining criminal networks that cultivate marijuana in the Sinai and smuggle drugs into Israel. Between the two, smuggling pays far better and is the only growth industry in the area.104 This was not the case until 2014, when Israel built a sophisticated security fence along key tracts of the border to prevent human trafficking. Until then, there was no need for, and thus market for, dedicated smugglers, because anybody could smuggle items across the then-open 200 km border with an easily-breached fence. The new fence includes sophisticated sensors and is 5 to 8 meters high, depending on the location.105

Egypt’s counterinsurgency campaign against Islamic State-Sinai, largely carried out through the so-called Sinai Tribal Union and other “armed civilian groups,” sputtered along for a while but began making significant gains with “Operation Sinai 2018.”106 Perhaps counterintuitively, however, cracking down on Islamic State-Sinai opened established smuggling routes in North Sinai that were effectively denied to smugglers while the Islamic State controlled those areas. Due to the lack of economic opportunities in the region, some of these tribesmen, now better armed, are believed to have turned to smuggling once the Islamic State in Sinai was effectively defeated.107 This helps explain the 2019-2020 spike in detected instances of smuggling of drugs at the Egyptian border.

What Is Smuggled, and Where?

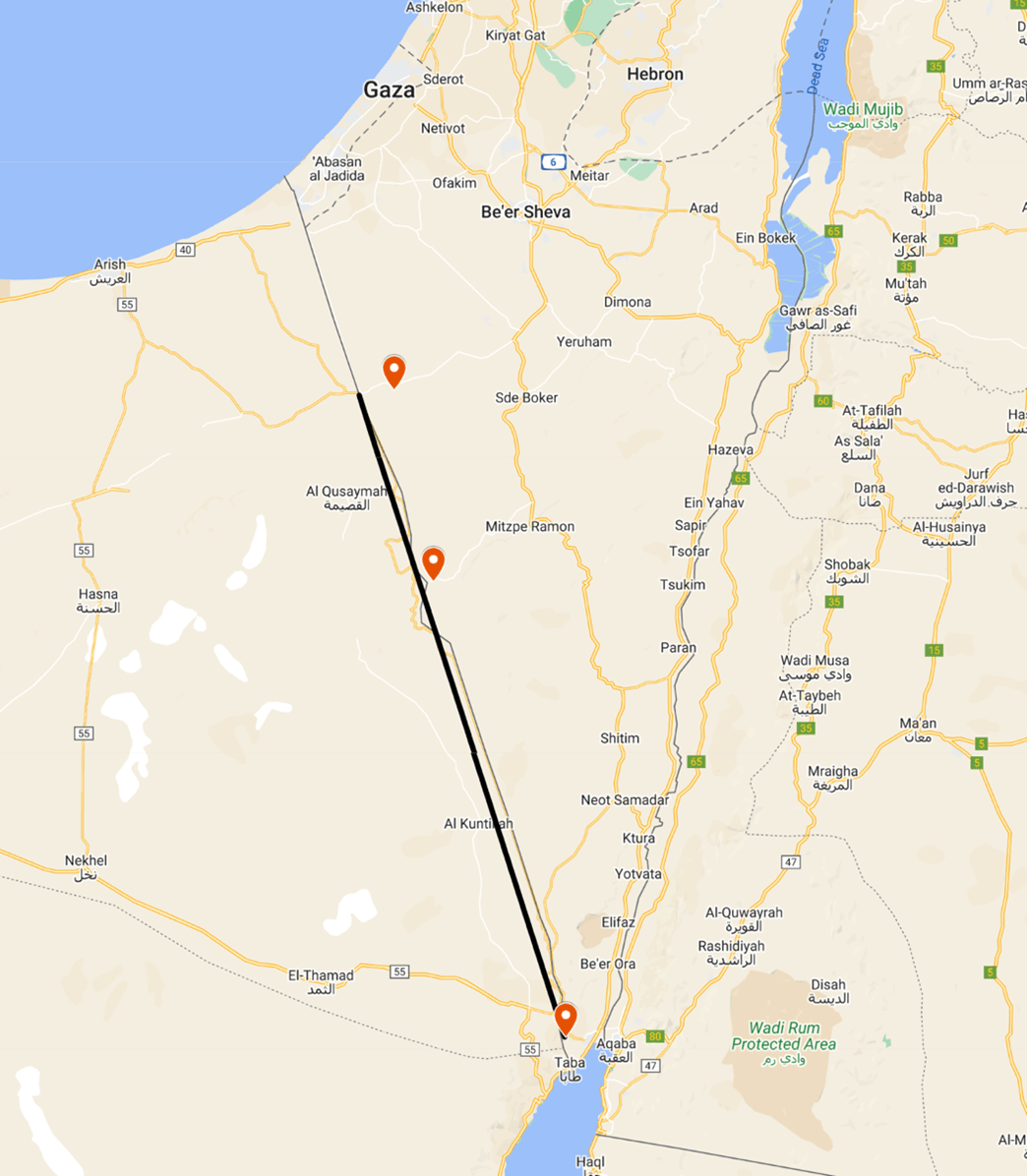

The Egyptian-Israeli border runs for just over 200 km, along which there are several hotspots where most of the cross-border smuggling takes place. Three of the most significant hotspots are along a 140-km run of the border starting at the Nitzana border crossing (border stone 26) and running south to Mount Harif (border stone 49) and Mount Sagi (border stone 53). Smuggling also occurs further north, near the Kerem Shalom crossing at the point where the Israeli, Gaza, and Egypt borders meet, and closer to the city of Eilat and the Red Sea.108 Most publicly reported cases, however, state that smugglings took place along the Egyptian border or in the territory of the IDF’s Paran Regional Brigade, which was established in 2018 (part of a restructuring of the IDF’s 80th “Edom” Division) for the specific purpose of guarding Israel’s border alongside the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula.109 The IDF also reports thwarting over 30 maritime smuggling attempts in 2022 emanating from Egypt, though it does not differentiate between those destined for Israel and those for the Gaza Strip.110

The topography of the Egypt-Israel border area favors smuggling, with its many dry river beds (wadis) that complicate surveillance and reconnaissance efforts by military and police and block lines of sight. Large water pipes run under some of the roads and provide cover. Periodic bluffs overlooking the border provide natural lookout spots for smugglers. On the Egyptian side of the border, smugglers emerge from staging areas around Jebel Khali and other mountains and cross the flat plateau that leads to the border fence. On the Israeli side, they do much the same, exiting from staging areas around Mount Hanif and Mount Sagi.111

Of the 52 reported smuggling attempts across the Egypt-Israeli border in the authors’ dataset, 49 involved drugs, with the remaining cases involving weapons and, in one case, $390,000 in gold bars.112 Hashish and marijuana grown in Sinai are two commonly smuggled commodities, but smugglers are increasingly trafficking hard drugs such as cocaine and heroin. In 2022, for example, Israeli authorities seized five tons of hashish, cocaine, and other drugs worth some $57 million. Many more drug-smuggling runs were not disrupted.113 Based on reported cases, over the past few years Israeli authorities have seized over 2,900 kg and an additional $31 million worth of drugs (some cases are reported by weight, others by value).114 According to a March 2023 U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime report on the global cocaine market, cocaine seizures in Israel increased dramatically from 2017 to 2021.115 However, the total value of drugs smuggled into Israel reportedly dropped from $4 billion in 2019 to $1.86 billion in 2020.116 Israel initiated an interagency counter-smuggling initiative in 2020, Operation Negev Shield (Magen HaNegev), after which the numbers reportedly dropped further still, reaching $370 million in 2021 and $85 million in 2022.117

Though much smaller in scale, there is also some limited smuggling from Israel into Egypt. This typically involves marijuana plant seeds first smuggled into Israel from the Netherlands onward into Egypt for cultivation there. The final product is later smuggled back into Israel for sale.118

As the pace of disruption rose, disrupting the flow of drugs in both directions across the border, smugglers developed more sophisticated and aggressive tactics to move their product. Countermeasures to evade counter-smuggling efforts include investing in surveillance and intelligence collection, fine-tuning smuggling tactics at the border and developing aggressive maneuvers for situations when military or police encounter smugglers.119

“Smugglers don’t have much,” an Israeli official explains, “but they do have time and patience.”120 Days ahead of a planned smuggling operation at the Egypt-Israel border, smugglers send spotters to a bluff overlooking a preferred smuggling spot along the border or along the roads leading to it to track security forces’ patterns of movement and determine when it is safe to approach the border. If needed, they will move on to another area or wait until security forces leave to patrol another area.121 At an abandoned Israeli military outpost on a ridge overlooking the Egypt-Israel border, the IDF found old mattresses, water bottles, and signs of a fire where spotters camped out for days to observe a preferred smuggling spot along the border. Smugglers also dispatch people to sit just outside the line of vision of the IDF’s stationary surveillance cameras, which are located sporadically along the border at smuggling hotspots, and report via walkie-talkie when the cameras are pointed away so that smugglers can move unnoticed.122

The criminal networks running drugs across the Egypt-Israel border also invest significant sums of money to hire teams of couriers, drivers, lookouts, and scouts, as well as operations officers to oversee each smuggling operation. Smuggling operations officers seek financially unstable Bedouin in the Negev Desert area who have either completed their IDF service or still serve in the IDF, including as trackers in anti-smuggling efforts, to obtain advanced knowledge of Israeli patrols and other intelligence.123 According to IDF figures, on the Israeli side of the border a courier is paid $15,000-$20,000 per smuggling run, a spotter sent to serve as a lookout at a border crossing before a smuggling operation is paid $5,000-$10,000, and the operations officer overseeing the smuggling attempt makes $10,000 per bag smuggled. On the Egyptian side of the border, the pay runs much less, with couriers earning $1,500-$2,000 per smuggling run, a spotter making $500-$1,000, and the operations officer $5,000 per smuggling attempt.124

While smugglers along the Jordanian border operate in small groups, one-way smugglers along the Egyptian border cope with increased patrols is to overwhelm them by sending groups of up to 30 people at a time. Egyptian forces—drawn not from the regular military but the Ministry of Interior’s Central Forces—tend to be lightly armed, lack floodlights to illuminate the border, and have old communications systems. Large groups of well-armed smugglers can effectively keep such Egyptian forces at bay while they withdraw from the border fence and escape. A typical smuggling run takes just two to three minutes at the border fence, with smugglers converging from either side to send and receive goods. A long smuggling operation might run up to eight minutes, but they are intended to be quick to decrease the risk of disruption or capture.125

At the Egypt-Israel border, smugglers typically throw bags of drugs and other contraband over the security fence,126 which is five meters tall in most places but six to eight meters tall at smuggling hotspots along a 17 km stretch of the border.127 At its higher points, smugglers rush the border with ladders so they can toss bags over the fence.128 In other cases, smugglers run “ATM operations,” where a square is cut out of the border fence and goods are passed through to a counterpart on the other side who retrieves goods as he or she might retrieve money from an ATM.129

Smugglers operating on the Egypt-Israel border tend to be more violent in cases when they are engaged by authorities and have large quantities of drugs in their possession. In some cases, smugglers run off into the wilderness carrying the drugs and leave their vehicles behind. The cost of losing a car is the cost of business, as long as the drugs are not confiscated.130

Smugglers on the Egypt-Israel border are growing increasingly sophisticated and are known to operate quadcopter drones to collect intelligence and evade patrols.131 In several cases, smugglers have managed to steal IDF tactical radios to broadcast music or gibberish noise and disrupt Israeli military communications during a smuggling operation.132 Smugglers, who typically drive sports utility vehicles (SUVs) or ATVs, can outrun both Egyptian and IDF patrols across the sandy terrain. They have also been known to run chains or place other impediments across roads to disable military or police vehicles, which must stick to the roads. Smugglers about to be cornered and desperate to evade capture have been known to attempt to ram military and civilian vehicles with their SUVs.133

Impact on Security and Public Safety

The U.S. Department of State’s 2012 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report listed Israel as having “a significant domestic demand for illegal drugs.”134 That demand has only intensified with the spread of COVID-19 and subsequent lockdowns. According to the 2022 World Drug Report, many countries, including Israel, reported overall growth in drug consumption and relapses since the start of the pandemic.135 From 2018 to 2022, marijuana addiction increased by nearly 50 percent in Israel,136 and by the end of 2022, the marijuana industry had grown to around 1.8 billion NIS (almost $500,000).137

While the majority of drugs consumed in Israel are smuggled into the country from abroad, domestic marijuana production is on the rise, with organized criminal groups growing the illegal crop in greenhouses in parts of the Negev desert classified as live firing zones.138 i Much as marijuana farms first popped up in isolated parts of U.S. national parks,139 Bedouin criminals now grow marijuana in the desert where civilians are less likely to interfere.140 While authorities are aware of this trend and now proactively cracking down on it, growers have become brazen as well. In 2020, Israeli Border Police found 27,500 marijuana plants growing at the edge of an IDF training base in the Negev. The plants were grown in trenches dug in a live fire zone with beige nets spread over them to make the area blend in with the desert.141

Aside from the public health threat posed by the flow of drugs into the country, Israeli officials are concerned about the increasingly aggressive and militant nature of these drug smuggling operations.142 Drug smuggling is so lucrative that criminal networks are willing to engage Israeli military and police in gun battles to protect their smuggling routes.143 Because of this, and because authorities do not know if what is being smuggled is drugs or weapons until they arrive on the scene, the IDF take the lead on counter-smuggling along the Israeli side of the Egyptian border, not the Israeli police.144

In December 2022, Israeli soldiers shot dead a suspect attempting to smuggle drugs from Egypt after smugglers fired at the soldiers as they arrived at the scene.145 In January 2022, nine drug- smuggling attempts took place across the Egyptian border on the same night. When IDF forces arrived at the various smuggling scenes, the smugglers fired at them. That night, soldiers confiscated over 400 kg of drugs worth approximately $2.2 million (NIS 8 million).146 Two Israeli Border Police officers were injured when Egyptian forces mistook them for smugglers.147 In February 2023, smugglers fired some thirty bullets at a base near the Nahal Lavan (White River) hiking trail close to the Egyptian border. In the nearby Israeli border community of Kadesh Barnea, farmers complained that chickens were killed in the crossfire when they shot at the vehicles of arriving Israeli forces.148

Conclusion

In early June 2023, Israeli forces thwarted a smuggling attempt in the middle of the night, and hours later, an Egyptian police officer crossed the border into Israel and shot and killed three Israeli soldiers. This case along with that of Jordanian Parliamentarian Imad al-Adwan attest to the increased need for cross-border security cooperation.149

Al-Adwan’s arrest came on the heels of increasingly strained Israeli-Jordanian relations, including clashes at the Temple Mount/Noble Sanctuary in Jerusalem on April 5, 2023, and comments on March 18, 2023, by a right-wing Israeli minister, who suggested that the idea of a Palestinian people is an “invention” and posed with a map of Greater Israel that included modern-day Jordan.150 And yet, both countries have sought to handle the arrest in a professional manner that would prevent further destabilization of the relationship between Jerusalem and Amman. The Jordanian foreign ministry released a statement noting it was following up on reports of the arrest with the relevant authorities.151 Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen went out of his way to state that he did not ascribe blame for MP al-Adwan’s actions to either the government of Jordan or the Jordanian Parliament, but rather saw al-Adwan’s behavior as “a foolhardy criminal act.”152 After the June 2023 shooting at the Egypt-Israel border, Egyptian Defense Minister Mohamed Zaki called Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant to offer condolences and discuss measures to prevent such tragedies in the future.153

The reason all sides displayed such restraint in these cases is that the three countries work diligently to prevent terrorist and criminal activities across and along their shared borders. It should therefore not come as a surprise that while al-Adwan was detained in Israel, Jordanian authorities ran a parallel investigation and arrested several suspects believed to be involved in the smuggling.154 In early May 2023, Jordan revoked al-Adwan’s legal immunity and Israel deported him back to Jordan to stand trial.155 Following the June 2023 shooting at the Egypt-Israel border, a senior Egyptian officer quickly visited the scene of the attack in Israel and IDF officials confirmed that the Egyptian army was fully cooperating in the investigation.156 Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu and Egyptian President al-Sisi spoke on the phone and reportedly agreed to conduct a joint investigation into the incident.157

Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian authorities all report a sharp rise in cross-border smuggling over the past couple of years.158 The authors’ dataset underscores the assessments of these officials, showing a significant increase in identified, thwarted, and disrupted smuggling across Israel’s borders with Jordan and Egypt, though the number of detected smuggling attempts across the Egyptian border was lower in 2021-2022 than its peak in 2019-2020. The downward slope in detected smuggling attempts since late 2022 (see figure 1) suggests that counter-smuggling efforts may be having the intended impact; however, it is still too early to draw firm conclusions. Some of the counter-smuggling success is attributable to enhanced cooperation between Israeli military and security agencies and the completion of border defenses. Furthermore, Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian officials all stressed to the authors the importance of their cross-border coordination and cooperation.159

Officials are increasingly willing to make such statements publicly. Enhanced counter-smuggling efforts are the result of a “deep understanding by decision-makers — both the police and government — that the Jordanian border is the most intensive source of fuel for crime in the Arab community, and for terror,” the head of Magen explained in 2022.160 “Strong cooperation” with Egyptian counterparts along the Egypt-Israel border has effectively constrained weapons and drug smuggling across that border, an Israeli officer noted that same year.161 Indeed, officials see counter-smuggling and border security as an area of growth with “lots of areas of potential regional and international cooperation.”162 Multilateral bodies such as NATO agree. In May 2023, NATO and Jordan held talks that focused on how the military alliance could help Jordan secure its borders.163 In the authors’ view, Egypt should be included in such discussions with particular focus on upgrading the training and equipment for the Egyptian Ministry of Interior’s Central Forces, its equivalent of Border Police, which often operate without basic necessities like modern communication gear and floodlights.164

In the final analysis, Israel, Jordan, and Egypt all see counter-smuggling and border security as a shared interest and a security function they perform for their own benefit. Many of the circumstances that have contributed to the increase over the last two years in detected smuggling are highly likely to persist, from regional instability and the ready availability of guns to the massive profits criminals stand to make from narcotics sales. Commercial incentives mean that smugglers will likely become more violent and more creative, from digging tunnels under border fences to deploying drones to transport packages over them. Cooperation between the three countries will continue to be crucial. CTC

Dr. Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler fellow and director of the Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Levitt teaches at the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and has served both as a counterterrorism analyst with the FBI and as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis at the U.S. Treasury Department. He has written for CTC Sentinel since 2008. Twitter: @Levitt_Matt

Lauren von Thaden is a Research Assistant in the Washington Institute’s Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence. Twitter: @l_von_thaden

© 2023 Matthew Levitt, Lauren von Thaden

Substantive Notes

[a] For every smuggling attempt identified, thwarted, or disrupted, an unknown number of others presumably get through without authorities ever learning about them. The authors believe the numbers detected by authorities is likely to be indicative of the true larger total. Israeli, Jordanian, and Egyptian authorities also made this point in interviews with the authors. Significant caveats apply, however. It should be noted that more smuggling attempts being detected/interdicted could also theoretically reflect more concerted counter-smuggling efforts and better intelligence rather than an increase in overall smuggling attempts. It should also be noted that, all other things being equal, more thwarting and disruption of smuggling could be expected to lead to a reduction in smuggling attempts over time. In other words, a higher number of interdictions could theoretically be associated with a decreasing rather than increasing problem set, though this would likely occur over a longer period of time than that studied here. Indeed, while most officials interviewed for this study reported that increased disruption of smuggling attempts was taking place against the background of an increased trend in smuggling activity, one Israeli official expressed the opinion that what has changed at the Jordanian and Egyptian border is not the overall level of smuggling, but rather the number of smuggling attempts that are identified, thwarted, or disrupted. Israeli official’s written answers to questions submitted by the authors, May 2023.

[b] While not the focus of this study, it should be noted that smuggling also occurs along the Blue Line that marks the de facto border between Israel and Lebanon, as well as along the demilitarized zone between the Israeli and Syrian portions of the Golan Heights. However, these cases are much less common than those along the Jordanian and Egyptian borders, and the authors’ dataset does not reflect significant changes in smuggling rates along these borders. Smuggling activity along Israel’s northern borders is likely less common because Israel faces significant threats from both Lebanon and Syria and therefore prioritizes maintaining tight security along these borders.

[c] The IDF differentiates between smuggling cases that were thwarted (meaning authorities on one side of the border or the other arrived on the scene in time to arrest smugglers and prevent any contraband from crossing the border) and those that were disrupted (meaning authorities interrupted a smuggling operation midstream, some contraband crossed the border, and some or all smugglers disperse before they could be detained).

[d] Figure 1 is based on the authors’ dataset and refers to identified, thwarted or disrupted smuggling attempts across the Jordanian, Egyptian, Lebanese, and Syrian borders.

[e] It should be noted with regard to the Egypt-Israel border, smuggling was higher the year before the pandemic (2019) than at any time since. Determining why the rate of detected smuggling goes up or down is complex, is not a result of any one factor, and may elude simple explanation.

[f] Figure 3 is based on the authors’ dataset. It only includes data on assembled guns smuggled across the Jordanian border. It does not include weapons parts or grenades. The IDF compiled higher numbers of weapons seized in the past three years because they include smuggling attempts that were not made public, but they do not differentiate between types of weapons.

[g] In an author interview in May 2023, an Israeli official reported 508 weapons were seized in counter-smuggling operations in 2022. The larger number of 570 weapons seized at or near the border appears to reflect a broader category than just those seized in specifically counter-smuggling operations. Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023.

[h] It is important to note that most of the open-source reporting of drug smuggling along the Israeli-Egyptian border, including government sources and media reports, does not specify the types of drugs smuggled. Sometimes it quantifies the amount of drugs seized by weight, and sometimes by estimated worth in dollars or shekels.

[i] The scheme does not always work, however, in part because Israelis have taken to camping in live firing zones when they are not in use. Shakked Auerbach and Daniel Tchetchik, “All the Fun Things Israelis Do in Army Firing Zones (Gun Training Not Included),” Haaretz, August 17, 2017.

[2] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[4] Lazar Berman and Emanuel Fabian, “Israel Arrests Jordanian MP for Trying to Smuggle 200 Guns in West Bank, Says Amman,” Times of Israel, April 23, 2023; Emanuel Fabian, “Bedouin Israeli Brothers Charged with Supplying Arms to Islamic Jihad in West Bank,” Times of Israel, February 9, 2023.

[5] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022; authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022.

[7] See, for example, Joe Truzman, “Collection of weapons confiscated by the IDF in Jenin …,” Twitter, July 5, 2023, and Israel Defense Forces, “[Current data on the activity of the IDF, the Shin Bet and the Security Forces in …],” Twitter, July 4, 2023.

[8] Ganor.

[9] Some of these interviews were held in person, and others over video teleconference. Some material was shared at these meetings, and more was provided in follow up communication via email, WhatsApp, and Zoom.

[10] This field research on the Israeli-Egyptian border was conducted in March 2023. Field research along the Israeli-Jordanian border was conducted in September 2019.

[11] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[12] Data provided to authors by Israeli security official, November 2022.

[13] This information comes from numbers released to the public and those provided in author interviews.

[14] Emanual (Mannie) Fabian, “IDF and police foiled an attempt to smuggle 10 handguns into Israel from Jordan last weekend, breaking up …,” Twitter, August 28, 2022.

[15] Authors’ dataset.

[16] Fabian, “IDF, Police Bust Gun-Runners on Jordan Border Amid Rise in Smuggling Efforts.”

[18] Data provided to authors by Israeli security official, November 2022.

[19] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023; authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022.

[20] Authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022.

[22] Goldenberg.

[25] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[26] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022; authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022.

[27] “Annual Data Report,” Israel Defense Forces, 2022.

[28] Author (Levitt) WhatsApp exchange, Israeli official, April 2023.

[29] Author (Levitt) interview, Jordanian official, December 2022.

[31] Authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022.

[32] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[33] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[34] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[36] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[37] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[38] Authors’ dataset.

[39] Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[41] Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[42] Ibid.

[43] Authors’ dataset.

[44] Emanuel (Mannie) Fabian, “Footage shows the arms allegedly seized from a Jordanian parliament member at …,” Twitter, April 23, 2023.

[45] Authors’ dataset.

[48] Fabian, “Bedouin Israeli brothers charged with supplying arms to Islamic Jihad in West Bank.”

[49] Ibid.

[50] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023.

[51] Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[52] “Delta Defence Group, Part One: The Pistol,” Silah Report, December 22, 2019.

[53] Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[54] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[55] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023.

[56] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023.

[57] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023.

[58] Peter Beaumont, “Homemade Guns used in Palestinian Attacks on Israelis,” Guardian, March 14, 2016.

[60] Authors’ dataset.

[62] Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[63] Ibid.

[64] Authors’ dataset.

[65] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023.

[66] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023.

[67] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023; Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[68] Osama Al Sharif, “Jordanians Polarized by Effort to Restrict Firearms,” Al-Monitor, July 22, 2019.

[69] “Study: South Syria’s Drug Supply Chains,” Etana Syria, June 2023.

[72] “Army Foils Weapon and Ammunition Smuggling Attempt on the Northern Border,” Jordan Armed Forces, July 22, 2022.

[73] Authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[80] Booth and Taha.

[84] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, May 2023; authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022.

[85] “IRGC Chief: West Bank is being Armed against Israel,” Unews (Lebanon), August 21, 2022.

[86] Frantzman, “Weapons Smuggling is an Increasing Threat to Stability in West Bank – Analysis.”

[88] “Weapons stolen from Israeli military base,” i24 News, November 12, 2022.

[92] Authors’ dataset.

[94] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[95] Figure 4 data is based on author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[96] Melman.

[97] Authors interview, Jordanian Official, November 2022.

[98] Adnan Abu Amer, “Report Outlines How Iran Smuggles Arms to Hamas,” Al-Monitor, April 9, 2021; “Smuggling Weapons from Iran into the Gaza Strip through Sudan and Sinai,” Israel Security Agency, 2020.

[99] Authors’ dataset.

[100] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[101] Author (Levitt) interview with Egyptian official, November 23, 2022; author (Levitt) interview with Israeli official, November 2022.

[104] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[105] Anna Ahronheim, “Israel Completes Heightened Egypt Border Fence,” Jerusalem Post, January 18, 2017.

[107] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[108] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023; author (Levitt) interview, Israeli officials, November 2022.

[110] “Annual Data Report.”

[111] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[112] Authors’ dataset.

[113] Melman.

[114] Authors’ dataset.

[117] Ibid.

[118] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[119] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[120] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[121] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[122] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[123] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[124] IDF poster provided by Israeli official, November 2022.

[125] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[126] Ahmed Shihab el-Dine, “The Eastern and Western Egyptian Borders: ‘All is Allowed! Anything Goes!’” Assafir Al-Arabi, June 12, 2019.

[127] Ahronheim, “Israel Completes Heightened Egypt Border Fence.”

[128] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[129] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[130] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[131] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[132] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[133] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023; author (Levitt) interview, Israeli officials, November 2022.

[134] “International Narcotics Control Strategy Report,” United States Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, March 2012.

[135] “World Drug Report 2022,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

[137] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[138] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[139] Martin Kaste, “Marijuana Farms Take Root in National Parks,” NPR, May 12, 2009.

[140] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, November 2022.

[142] Shihab el-Dine.

[144] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[145] “Israeli Soldiers Shoot Dead Drug Smuggler Near Egypt Border,” Asharq Al-Awsat, December 15, 2022.

[148] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[151] Jordanian Foreign Ministry statement, Twitter, April 23, 2023.

[153] “Egypt and Israel’s Defence Ministers Discuss Border Shooting Incident,” Reuters, June 3, 2023.

[154] Fabian, “Israel hands over Jordanian MP who allegedly smuggled 200 guns into West Bank.”

[155] “Jordan’s Lower House Revokes Immunity of Released Lawmaker Imad Adwan,” Jordan Times, May 7, 2023.

[157] “Egyptian and Israeli Leaders Discuss Border Shooting, Investigation,” Reuters, June 6, 2023.

[158] Authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022; author (Levitt) interview, Egyptian official, November 2022; author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[159] Authors interview, Jordanian official, November 2022; author (Levitt) interview, Egyptian official, November 2022; author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

[160] Fabian, “On Porous Border, Israel Starts to See Success Against Rampant Gun Smuggling.”

[162] Author (Levitt) WhatsApp voice note exchange, Israeli official, November 2022.

[163] “NATO and Jordan Discuss Border Security Cooperation,” NATO News, May 17, 2023.

[164] Author (Levitt) interview, Israeli official, March 2023.

Skip to content

Skip to content