In the immediate aftermath of the multi-pronged terrorist assault in Paris, policymakers, practitioners, and the press began to focus on the possibility that returnees from Iraq and Syria had participated in carrying out the tragic attacks. This possibility of a connection was further strengthened by the discovery of a Syrian passport on one of the suicide bombers and a number of witnesses to the attacks who claimed that the attackers referenced Iraq and Syria, with one account claiming that one of the terrorists shouted, “This is for Syria.”[1]

While the exact role that foreign fighters may have played in these attacks will likely remain unclear for the near future, the threat posed by returning fighters has been a central focus of counterterrorism efforts for some time. By utilizing a unique source of open-source data on foreign fighters that the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) at West Point has been collecting over the past year, which has resulted in the collection of 182 detailed records of French foreign fighters (as part of a much larger set of Western foreign fighters), this CTC Perspectives endeavors to offer a bit of context regarding the French foreign fighter threat.

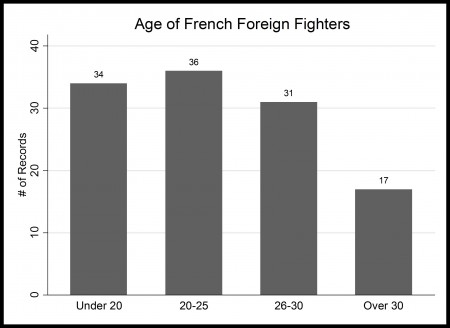

One of the claims made by a number of witnesses of the Paris attacks was the relatively youthful appearance of some of the attackers. Indeed, early indications about one of the individuals is that he was a 29-year-old French national.[2] This seems consistent with what we see among French fighters in the CTC dataset, in which the average age was approximately 25. In other words, young individuals seem to form a large portion of the French foreign fighter contingent. The appeal of organizations like the Islamic State among youth is not particularly surprising given their slick propaganda campaign and social media outreach, but the involvement of younger fighters in the Paris attack, if proven to be the case, may raise additional questions about the implications of such a youthful appeal.

Another way in which foreign fighters could contribute to an attack similar to what occurred in Paris is if they carried knowledge of the streets and terrain above and beyond that which would be attained through weeks or months of pre-operation surveillance. The 29-year-old individual mentioned earlier is said to be from Courcouronnes, a location 20 miles south of Paris. In our data of French foreign fighters, we were able to ascertain the hometown of 145 of the fighters. Approximately 25 percent of the French fighters in our dataset came from the Paris-metro area. As would be expected given the large population of the city and its suburbs, this number represents one of the largest concentrations of foreign fighters. It is worth noting that the southern region of France accounts for 42 percent of fighters in our dataset, although they are spread throughout a number of smaller towns and locations across the southern part of the country.

One of the most difficult things for security services to assess is what kinds of skills and training foreign fighters receive while in Iraq and Syria. The fact that they could have acquired sufficient training to plan and execute the Paris attacks seems self-evident after the fact, but is also evident from examining the limited data we were able to collect in this project. We were only able to assess the operational role filled by foreign fighters for 84 of our French foreign fighters. Of that limited number, however, we found evidence that at least 50 of them served as foot soldiers, gaining valuable front-line experience in carrying out operations under pressure. Of course, as shown in the still shots from the Islamic State propaganda videos below, the Islamic State operates a number of training camps in Iraq and Syria where incoming fighters receive training tactics and weapons that could be applied in a number of settings, whether on the battlefield or when they return to their home countries.

It also emerged that at least 7 of the 8 Paris attackers died by detonating suicide devices, bringing for the first time in France’s history the phenomenon of suicide bombing to its homeland.[3] Despite the newness of this tactic in the French homeland, our data also show that a number of French foreign fighters that traveled to Iraq and Syria set the precedent of dying for the cause. Indeed, at least 14 of the French fighters in our data either died in suicide bombings in Iraq and Syria or expressed a willingness to do so. Beyond suicide bombings alone, we were able to confirm that 23 percent of the French foreign fighters in our dataset died in Iraq and Syria. In other words, the expectation of being willing to die for the cause has been set for French fighters to emulate.

To be clear, the fact that such an expectation is perpetuated among fighters in Syria is not a supposition, but something that they themselves have confirmed in interviews. In the words of Abu Mariam, a 24-year old foreign fighter for France:

Martyrdom is probably the shortest way to paradise, which is not something I was told. I did witness my martyred friends, noticing contentment on their faces and the smell of musk coming out of their corpses, unlike those of the dead disbelievers, the enemies of Allah, whose faces only exhibit ugliness, and whose corpses smell worse than pigs.[4]

Although our data focuses mainly on Western foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq, we also collected a number of records, 32 to be precise, of French individuals deemed to be facilitators of foreign fighter travel. While those who carry out violence tend to garner the most attention, it important to remember that the same networks that facilitate travel may very well also be used by the organization to help returnees carry out attacks, or to do so on their own. It is too soon to say whether such a facilitation network played a role in the Paris attacks, but the sheer size, scale, and complexity of the attacks would suggest the participation of a network larger than just a couple of returned foreign fighters. The possibility of a broader facilitation network reaches beyond France. Reports of arrests related to the Paris attacks have emerged from Germany and Belgium.

Within the next month, the CTC will be publishing the first of a series of reports related to the broader issue of foreign fighters that examines the question of foreign fighter radicalization. It is our hope that this collection and analysis effort will contribute to understanding the enduring threat posed by foreign fighters.

Daniel Milton is an Assistant Professor at the Combating Terrorism Center at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The views presented are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Army, or any of its subordinate commands.

[1] Rose Troup Buchanan, “Paris terror attacks: Syrian passport found on body of suicide bomber at Stade de France,” Independent, 14 November 2015; Andrew C. McCarthy, “This is for Syria…Allahu Akbar,” National Review, November 13, 2015.

[2] Adam Nossiter, Aurelien Breeden, and Katrin Bennhold, “Three Teams of Coordinated Attackers Carried Out Assault on Paris, Officials Say; Hollande Blames ISIS,” New York Times, November 14, 2015.

[3] Of course, the French people have dealt with this type of terrorism before, having been targeted alongside American military personnel on October 23, 1983 in a twin truck bombing in Beirut, Lebanon.

[4] Loubna Mrie, Vera Mironova, and Sam Whitt, “I am only looking up to paradise,” Foreign Policy, October 2, 2014.

Skip to content

Skip to content