Abstract: In the summer of 2017, a simple photograph shared on Facebook, in Portugal, was enough for an Iraqi soldier to identify a former member of the Islamic State living in Lisbon as a refugee. This led to an investigation that lasted four years but was ultimately driven by the intense and unprecedented sharing of information with the Portuguese authorities by the Iraqi judiciary, UNITAD – the Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/ISIL, and Operation Gallant Phoenix. The result was a historic conviction of two members of the Islamic State with heavy prison sentences for joining a terrorist organization and for war crimes committed in Iraq. Based on a review of more than 8,000 pages of court documents, this article shows how the preservation of evidence, cooperation, and information sharing will be key to bringing the escaped members of the terrorist group to justice and bringing peace to their victims.

On January 18, 2024, Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen, two Iraqi brothers living in Portugal as refugees, were sentenced by the Lisbon Judicial Court to 16 and 10 years in prison, respectively, for joining an international terrorist organization—the Islamic State—and committing war crimes in Iraq.1 It was a historic ruling. Not only was it the first time that Portuguese justice had convicted an individual for war crimes, in this case committed in a third country, but the outcome was also made possible due to extensive and unprecedented international cooperation involving the Iraqi authorities; UNITAD – the Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/ISIL, established through United Nations Security Council Resolution 2389 (2017); and Operation Gallant Phoenix, a U.S.-led multinational intelligence platform established in Jordan in 2013.2

The work of UNITAD investigators allowed the Portuguese State Prosecutor to obtain original documents from the Islamic State and files from a judicial case that was being conducted in the Court of Investigation in Terrorism Matters of Nineveh, in Mosul, Iraq, as well as the testimony (via video conference) of victims and eyewitnesses of the atrocities.3 In their testimonies, some of these witnesses also reported details on how the population sought ways to resist the Islamic State during the group’s occupation of Mosul.4 Through Operation Gallant Phoenix, it was possible to obtain reliable digital evidence collected during a period of a conflict, which strengthened the prosecution’s case.5

This article, based on more than 8,000 pages of judicial documents, shows how two former members of the Islamic State living in Europe as refugees were discovered almost by accident and how international cooperation and UNITAD’s work in collecting and preserving evidence and testimonies were crucial for the investigation and imposition of significant prison sentences. The case is an important one to highlight as it shows how international judicial cooperation and battlefield intelligence can be leveraged to support successful prosecutorial outcomes in cases that involve both terrorism and war crimes suspects.

From Refugees to Suspects

“Ahmed”a arrived in Portugal in December 2015. Born and raised in Mosul, he had fled the city in the summer of that year after being whipped by the Islamic State’s morality police, Al Hisbah, for wearing jeans and being caught with a pack of cigarettes. “My father asked me to leave [the country]. He had already lost two sons and told me he didn’t want to lose a third,” he later told the Portuguese authorities.6

In Portugal, he settled in a small city on the countryside. In the spring of 2017, a friend told him there were two Iraqis from Mosul in Lisbon and he should meet them. Ahmed agreed. He had not seen anyone from his hometown in a long time. They arranged to meet at the hotel where his friend worked as a cook, on the outskirts of Lisbon. The two introduced themselves as Ammarb and “Adam.”c “We talked about Mosul. When they told me which neighborhood they were from, I recognized it immediately,” he said.7 When Ahmed suggested taking a photo for social media, Ammar refused. “He said he was wanted by the Islamic State because he was a journalist,” Ahmed recalled.8

The three met a few times at immigrant gatherings in Portugal in the summer of 2017. On one of these occasions, Ahmed said, “a friend made a live video in which Ammar appeared singing. He [Ammar] confronted him and told him he had to delete it.”9 At another meeting, Ahmed actually took a photo with the friend he knew as “Adam.” He shared it on Facebook, writing in the caption: “Me and Adam.”10

Shortly afterward, he was surprised to discover that “Adam” had blocked him on social media. He was even more incredulous when an Iraqi soldier, identified as Salwan Al Hamdani, contacted him on Facebook and told him that Adam’s real name was Yasir and that he used to be a member of the Islamic State. The soldier also mentioned that he knew Yasir and his brothers, Fouad and Ammar, well. “He told me that they had taken possession of the goods in his house as spoils,” Ahmed recalled.11

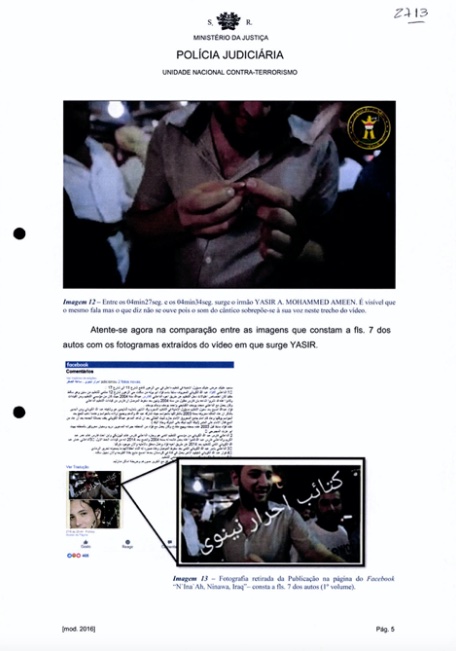

Around the same time, Ahmed found the Facebook page N’Ina’Ah, Ninawa, Iraq, created by the organization Ahrar Naynawa – Saat al-sifr (The Freeman From Nineveh Brigade – Zero Hour) to disclose the identities of alleged members of the terrorist group that had subjugated the civilian population in that Iraqi province.12 In one post, published on July 27, 2017, the organization disclosed information about Fouad Abdullah Al-Kuyani, former head of Islamic State security in the area between 11th and 17th streets in the Al-Zuhur neighborhood of Mosul. The same publication indicated that Fouad had recruited two of his brothers, Yasir Ameen and Ammar Ameen, to the terrorist group, identifying them by name and with photographs.13 When Ahmed saw the images, he was astonished. “It was a shock. How was it possible that I had known them here and they were ISIS members,” he told the Portuguese authorities.14

After chatting with Salwan Al Hamdani on Facebook, Ahmed contacted his brother, who was still living in Mosul and had friends in the police. His brother reached out to Colonel Mohammed S., who confirmed that the two brothers were wanted as members of the Islamic State, along with a third brother, Fouad Ameen.15 Ahmed decided to alert the authorities and went to the regional office of Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras (SEF)d in Leiria to file a report.16 The following month, the SEF shared the information with the country’s Anti-Terrorist Coordination Unit, and on September 26, 2017, an investigation into the brothers was officially opened at the Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal (DCIAP).17 e

The investigators began by preserving the information available on the Facebook page N’Ina’Ah, Ninawa, Iraq and collecting all data on Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen since their arrival in Portugal. Their administrative files showed that both had landed in Lisbon on March 29, 2017, coming from Athens, Greece, under the European refugee relocation program.18 f They gave different versions of their escape: While Yasir Ameen claimed to have left Iraq hidden in a coffin to Adana, Turkey, and then traveled by bus to Istanbul,19 Ammar Ameen said that the entire trip was made by car.20 In Istanbul, they took a boat to the island of Lesbos, where they stayed until they were transferred to Portugal.

Living in state-provided accommodation and receiving state support, Yasir and Ammar were placed under telephone surveillance and subjected to constant monitoring as soon as the investigation started. Judicial Police inspectors followed them through the streets of Lisbon, to meetings with friends, photographed them alone and accompanied. They listened to their conversations and investigated their contacts. They did this for four years, without finding any links between the two and the Islamic State.21

During this period, Yasir Ameen strove to integrate into Portuguese society. He learned the language, maintained a social life, including a boyfriend, and found a job in a restaurant managed by refugees that was frequently touted as an example of integration and, for that reason, visited by senior Portuguese politicians. While the investigation was secretly ongoing, he was photographed at his workplace with the Portuguese president, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, and then Prime Minister António Costa.22 g Unaware of the existence of the judicial inquiry, in September 2019, the administrative authorities granted him a residence permit for a period of three years.23

Ammar Ameen’s situation proved to be more complicated. Right at the start of the investigation, on November 17, 2017, the Iraqi bought a one-way bus ticket to Stuttgart, Germany. According to what the German authorities reported to the Portuguese Judicial Police, he settled in a refugee center in Ellwangen, in the state of Baden-Wurttemberg, and expressed his desire to seek asylum there. He was then transferred to the city of Trier in Germany. However, he was eventually sent back to Portugal by the German authorities, without the reason for his trip to Germany being fully clarified.24

In Lisbon, Ammar caused several conflicts with employees of the Portuguese Center for Refugees, which was hosting him, and during a telephone conversation he even threatened to blow up the premises.25 During a visit to the SEF facilities, faced with delays in obtaining a residence permit, he threatened the inspectors who were assisting him: “I’ve reached my limit, I’ll kill myself. But I won’t die alone. I’m serious.” He reinforced his threat: “I’ll kill myself here. The journalists will have something to film. I’m not joking. I’ve reached my limit.”26 His request for international protection was eventually denied by the Portuguese authorities and his expulsion from the country ordered in May 2019; appeals filed by his lawyers prevented it.27

Enter UNITAD

In October 2020, with the investigation at a standstill and fears that the brothers were part of a sleeper cell of the Islamic State, the Portuguese Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Judicial Police turned to international cooperation mechanisms to try to substantiate their suspicions.28 After contacting INTERPOL and EUROPOL without much success, investigators connected with officials from the United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD). An independent investigative team created in September 2017 at the request of the Iraqi authorities and unanimously approved by the United Nations Security Council, UNITAD’s mandate was to collect, preserve, and store evidence in Iraq related to terrorism, war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity committed by the Islamic State in Iraq in accordance with the highest standards of quality so that it could be used in fair and independent trials.h One of UNITAD’s priorities was precisely to investigate the crimes committed by the Islamic State in Mosul.29

UNITAD’s Mosul Investigation team leader since 2019 was Paulo Irani, an investigator who had spent the previous 10 years working with the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court investigating genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.30 When he received the request from the Portuguese Judicial Police to assist its investigation in late 2020, he started analyzing UNITAD’s database and gathering information from Ninewa’s Investigation Court Specialized in Terrorism Cases, police, and the Iraqi government about Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen. He quickly realized that the Iraqi intelligence services’ databases contained evidence indicating that the suspects’ older brother, Fouad Ameen, was a commander of Al Amniyat in Mosul, for whom an arrest warrant had been issued.31 In cooperation with the First Judge at the Court Specialized in Terrorism Cases, Judge Raed Hamid al-Musleh, Irani began a field investigation to ascertain whether the two brothers had indeed been Islamic State members.32

The Investigation in Iraq

Irani started by contacting the creators of the Facebook page N’Ina’Ah, Ninawa, Iraq to find out why the photos of the two suspects had been published.33 The ensuing investigation, which lasted a year (between October 2020 and October 2021), eventually put him in touch with a resistance network against the Islamic State occupation, led by Mosul Police Colonel Mohammed S. According to Irani, the officer was part of a group of “police, and military personnel who, after their defeat in battle [in July 2014], fled and created the Free People of Nineveh Facebook page to publish photos of Daesh members.”34 The goal was to “make the young people of Mosul afraid to join the organization.” Information about the terrorists’ identities was obtained by undercover agents who remained in the city after the occupation. These agents also identified the location of minefields and Islamic State leaders, which Mohammed S. then forwarded to the international coalition fighting the terrorist group.35

In a lengthy statement later made via videoconference to the Portuguese authorities, Mohammad S.36 noted how, when the Islamic State took Mosul in the summer of 2014, he and many others fled to Erbil, where he joined the Iraqi resistance against the terrorist group. “When Mosul fell, we had a meeting with the then National Security Advisor, Farih Al Fayyadh,i and with the judicial authorities. We then formed an intelligence and sources network, called the Free Men of Nineveh, for which I was given responsibility. The initial goal was to expose those who had joined the Islamic State by publishing their photos, to dissuade anyone who was thinking of joining and to protect citizens,” he said.37

The Free Men of Nineveh brigades were organized by geographical area. “Each one was named after its leader and consisted of groups of five to seven people. Their duties were divided between gathering intelligence about targets, the terrorist organization, and to find information about individuals and confirm whether or not they had joined the Islamic State,” Mohammed S. said.38 Members of these brigades also carried out subversive actions such as raising the Iraqi flag in the city, writing slogans on walls, distributing leaflets, setting fire to places used by the terrorist group, and photographing certain areas.39

This information was passed on to the international coalition fighting the Islamic State. “I had weekly meetings with the representative of the Norwegian forces. I also met with the representative of the French forces. As for the Americans, our meetings were fortnightly … I would give them targets and they would ask for locations to observe or GPS coordinates. Thanks to this intelligence, several military sites belonging to Islamic State were hit, as well as leaders of the organization in Mosul,” Mohammed S. testified.40

In addition to the information gathered by police officers who remained in Mosul, Mohammed S. also stated that during the occupation, he maintained contact with “13 people who had infiltrated the organization, one of whom was a leader, the seventh or eighth member in the hierarchy. After liberation, they received a special pardon from the prime minister for collaborating with us.”41

When he received information that someone belonged to the Islamic State, Mohammed S. would ask one of his agents to confirm the details. This is what he did when a neighbor of Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen reported them. Their older brother, Fouad Ameen, was an old acquaintance of Mohammed S. “I knew him as one of Al Qaeda’s executioners,” Mohammed S. stated.42 “I sent Ammar R. to the Al Zuhur neighborhood to confirm it with his own eyes.”43

Ammar R.44 is a police officer who led of one of the Free Men of Nineveh brigades scattered throughout the city. When Mosul fell, he was unable to leave in time. To survive, he began using his younger brother’s identity.45 In order to go unnoticed and gather the information he was asked for, he wore simple clothes and even slept on the streets. Known by the kunya Al Qa’Qa, he told the Portuguese authorities via videoconference what happened at the time: “In 2014, I was asked by the colonel to investigate three people: Yasir, Ammar, and Fouad. I went to the Al Zuhur neighborhood and learned from my sources that Fouad had belonged to Al Qaeda and that when the Islamic State entered Mosul, he joined ISIS [intelligence services] Al Amniyat. Ammar worked at Al Hisbah [the morality police]. As for Yasir, I saw him wearing the kandahari costume. He swore allegiance to the Islamic State, entered the combat training course, but was expelled.46

To gather information, Ammar R. said he spoke to “seven or eight people” over the course of a week. Their statements matched. He then saw the brothers in person at “the Sayyidat Al Jamila roundabout, in the Al Zuhur neighborhood, where they carried out their duties”47 and sent a report to Mohammed S. “Yasir was not armed. I saw Fouad and Ammar armed with pistols and machine guns. I also saw Ammar checking the length of people’s pants and beards,” he added.48 Mohammed S. then published the information about Fouad, Yasir, and Ammar on the Free Men of Nineveh Facebook page, emphasizing that their remaining eight brothers had not joined the Islamic State. “I took Yasir’s photo from a video in which he appeared handling a gold coin,” Mohammed S. said.49 The propaganda video in question was published by Amaq Agency and showed the alleged joy of Iraqis with the arrival of the gold dinar, the Islamic State’s new currency. In the video, Yasir Ameen appeared in civilian clothes, happily smiling and holding a coin for a few brief seconds before passing it along to other enthusiastic Islamic State supporters.50 “There was another [Islamic State] publication where he appeared congratulating himself on the conquest of Al Ramadi,” Mohammed S. added.51

With the information provided by the Iraqi police colonel, UNITAD investigator Paulo Irani went to the Al Zuhur neighborhood to find out what the neighbors knew about Yasir and Ammar Ameen and their family.52 He traveled there alone and was later joined by Nashwan A.,j the Mukhtar of Al Zuhur, who was appointed to this task by the judge from the Nineveh Investigation Court Competent in Terrorism Cases. During these visits, several people confirmed that Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen belonged to the Islamic State. One of them said he had been robbed, kidnapped, and tortured by the brothers. These witnesses told Judge Raed Hamid al-Musleh what they knew, and it was on the basis of these statements that an arrest warrant was issued on February 8, 2021, against Yasir and Ammar Ameen by the Federal Appeals Court of Nineveh.53

A Concerted International Effort

In February 2021, Paulo Irani shared his findings with the Portuguese Judicial Police.54 It was then that DCIAP State Prosecutor, Cláudia Porto, formally requested the cooperation of the Iraqi authorities by issuing a Mutual Legal Assistance Request addressed to the head of UNITAD, Special Adviser Karim Asad Ahmad Khan.k In this letter, Porto requested the “cross-checking search against UNITAD evidentiary holdings in relation to” Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen; the “identification of witnesses” and the “potential collection of testimonial evidence;” the “provision of material held by UNITAD relating to” Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen; and, lastly, to “transmit the original of the criminal case (with all the evidence and arrest warrants issued) in progress at court in Mosul-Iraq against” the brothers.55 The request was essential for the data collected to be used as evidence in Portuguese court.

UNITAD’s supportive response, dated July 29, 2021, represented a definitive breakthrough in the case after nearly four years of investigation. In that letter, UNITAD’s officer in charge, Sareta Ashraf, wrote that the organization had “identified eleven documents” responsive to the request that would be sent “by secure electronic means” along with translations from Arabic into English.56 l The documents consisted mainly of certified copies of witness statements, arrest warrants issued by Judge Raed Hamid Al Musleh, and personal data on Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen. “In addition, one document provides information concerning a now-closed Facebook page that may have relevant information.”57 UNITAD also asked to be informed in advance if any of the information was to be used in legal proceedings so that consultations could be held to ensure it would be: “handled in a manner consistent with the UNITAD’s Terms of Reference and the privileges and immunities enjoyed by the United Nations. Redaction of some information prior to its submission in criminal proceedings may be requested to ensure, inter alia, that the identity of specific witnesses or individuals is not made publicly available, or to enhance witness protection.”58 Finally, UNITAD stated that it had “received oral confirmation” that the witnesses authorized the “transmission of their statements to the Portuguese authorities, and that this consent will be re-confirmed by UNITAD in due course.”59

The response came at a crucial moment, as Portuguese investigators were running out of time. After exhausting all avenues of appeal against the rejection of his application for international protection, Ammar Ameen could be deported from the country at any moment, which would make it impossible to continue the investigation. In addition, a reference to the criminal investigation in the administrative proceedings alerted Ammar Ameen to the fact that he was being investigated on suspicion of terrorism.60 It was on the basis of data gathered from open sources and official documents transmitted by Iraq through UNITAD that the Public Prosecutor’s Office decided to proceed with the arrest of the two brothers and request the hearing of Iraqi witnesses for future reference, which was approved by a criminal investigating judge on August 20, 2021.61

Arrests and Testimonies

Both men were arrested on September 1, 2021, in Portugal. But when they appeared before the criminal judge overseeing the case, the brothers took different stances. While Ammar Ameen chose not to make a statement and exercised his right to remain silent,62 Yasir Ameen decided to answer the magistrate’s questions in an interrogation that took place between 8:37 p.m. and 10:04 p.m. on September 1, 2021.63 During that interrogation, Yasir denied any connection to the Islamic State and claimed that he only appeared in the video with the gold dinar coin because he was working in a restaurant when the terrorist group’s film crew showed up. “I couldn’t say no, or they would have taken me away to kill me,” he said.64 But his main argument of defense surprised the court. “I left Iraq to escape the war. I am homosexual. […] They throw homosexuals off buildings, but they didn’t know I was one. I was afraid of them, they are monsters. They kill children, old people, everyone,” he added, saying he had been whipped for smoking. He stated that he was not religious and that he was happy in Portugal: “I have a boyfriend, a cat. I was thinking of getting married. I got my driver’s license and was thinking of buying a car.” However, he became entangled in confusing explanations about his life in Mosul during the Islamic State occupation and how he managed to escape the city with his brother (Ammar) via Al Raqqa, a route controlled by the terrorist group. The judge also did not believe Yasir when he stated that he did not know whether his brothers joined the Islamic State or not. At the end of the evening, the two brothers were both placed in preventive detention, in line with the State Prosecutor’s request.65

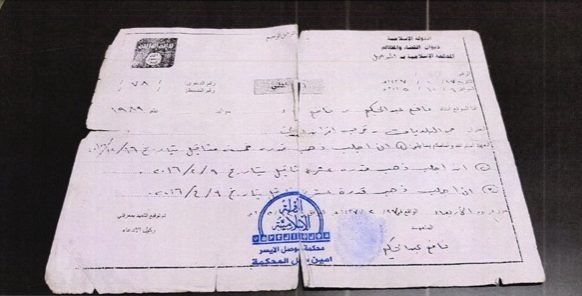

A month later in October 2021, the Public Prosecutor’s Office had another breakthrough. On October 15, UNITAD reported that it could share seven additional documents related to the case.66 These were original Islamic State documents issued by the so-called Department of Justice and Complaints of the Mosul Religious Court, which served to corroborate the testimony of a witness who said he had been kidnapped by the Ameen brothers. This included a marriage contract, receipts for the delivery of gold, and court summons.67

In late November 2021, the witnesses located by Paulo Irani in Mosul traveled to the U.N. offices in Duhok, Iraq, to testify via videoconference in the Portuguese proceedings, so that their testimony could later be used in trial. Despite UNITAD’s request that their identities remain confidential, the Public Prosecutor’s Office requested them to identify themselves before the judge. With the investigation based on witness testimony, this was the only way to obtain a future conviction, as Portuguese law prevents a conviction from being based “exclusively or decisively on the testimony or statements produced by one or more witnesses whose identity had not been revealed.”68 The witnesses agreed to the stipulation.69

The first to testify were Nafee A.70 and his father, Abdul A.71 With the help of a translator, the former recounted that during the Mosul occupation, he married a woman, who lived opposite the family home of Yasir and Ammar Ameen in the Al Zuhur neighborhood, through a religious contract—one of the documents sent by UNITAD. One day in 2015, upon discovering that her husband (Nafee) had photos of another woman on his cell phone, his wife took the device and gave it to her father, Ahmed J. who filed a complaint with Al Hisbah.

However, the case was transferred to Al Amniyat on suspicion that Nafee was spying for Iraqi forces. “The next day, Fouad [Ameen] came to my house. He showed me my cell phone. He told me that [the device] contained my personal information, the names of police officers and army officials with whom I was in contact and to whom I provided information,” Nafee told the Portuguese judge. “Then he [Fouad] asked me to pay. He wanted gold, not money.”72 He also demanded, at gunpoint, that Nafee hand over his identification documents, as well as the property records for the house where he lived with his parents, wife, and siblings, and for a family plot of land. The goal was to prevent Nafee and his family from fleeing. “Without documents, we couldn’t leave Mosul,” Nafee explained.73

The next morning, Abdul A. explained that Fouad, Yasir, and Ammar Ameen returned to look for his son, who was not at home. “On that occasion, I asked Fouad for our documents. He told me that he had given them to his brother Yasir, who worked in the real estate department” at the University of Mosul, Abdul told the Portuguese judge.74 In the afternoon, Fouad Ameen and a group of Al Hisbah members went to the watch shop where Nafee worked, beat him, blindfolded him, and took him by car to an old church that served as a prison, torture chamber, and execution site. Abdul assured the judge that Yasir was part of that group.

Nafee spent 11 days in an Islamic State prison in Mosul. He was questioned about the photos he had on his cell phone. Then he was taken back to the cell. On the walls were televisions showing images of executions. Some of the victims had been detained with him. “I saw Ammar in prison. I didn’t see Yasir,” Nafee said.75 One morning, he was taken to an open field, forced to his knees, and told he was going to be executed. They fired three shots beside him before taking him back to prison.76

During those days, Abdul A. tried everything to free his son. He ended up paying $15,000 to two foreign members of Al Hisbah, a Frenchman and a Chechen, so that Nafee would not be executed.77 When he was brought before the Islamic State judge again, Nafee was sentenced to 120 lashes, which were immediately administered. It took him two months to recover.78

Unhappy with the outcome, Ahmed J. (Nafee’s father-in-law) filed another complaint against Nafee, which led to case no. 78 in the Department of Justice and Complaints of the Islamic State Religious Court. Ahmed J. accused Nafee of passing information to the Iraqi authorities, not being good to his wife, and stealing gold and money. When the families attempted a reconciliation, Ammar and Yasir were present. Following the failure of an agreement, the Islamic State court ordered Nafee to pay seven million Iraqi dinars in gold, divided into three installments. For each delivery, a receipt stamped by the Islamic State was issued—these documents were also sent by UNITAD to Portugal.79

The third witness was Ali A., a resident of Al Zuhur who had known the Ameen brothers since adolescence. He told the Portuguese court that he saw Ammar Ameen wearing the kandahari outfit worn by members of the Islamic State. “I saw him wearing Al Hisbah clothing, walking around the neighborhood, inspecting people’s clothes and the length of their beards,” he said,80 adding that at one point Ammar wanted to call for prayer at the Mohamed Al Amine Mosque and was prevented from doing so. “Then he got a document from ISIS that forced those who worked at the mosque to let him make the call,” Ali A. stated. As for Yasir Ameen, Ali A. said that he did not see him wearing “Afghan clothing or carrying a weapon,” but said he did not know if he had another role in the organization.81

Ali A. left the U.N. premises after testifying in the early evening of November 26, 2021. He arrived in Mosul at 9:30 p.m. and went to bed. But at 11:15 p.m., he was awakened by his brother because two men were at the door insisting on speaking with him. According to a report82 sent by UNITAD on November 29, the witness went outside the door of his home to meet two brothers of Ammar and Yasir Ameen. “The visitors asked the witness why he had testified against their brothers and told him that their brothers had not done anything wrong. The visitors added that they had borrowed a lot of money to get their brothers to Europe, a debt they continue to repay.” One of them was “polite,” Ali A. testified, but the other had a threatening tone, saying that Ali A. “would be held responsible” if “anything happen to their brothers.”83

The discussion lasted about 10 minutes. Back home and “frightened,” Ali A. sent a message to investigator Paulo Irani. “The witness added that he had not told his family or anyone else about his testimony, before or after it took place,” because his family would disapprove of the risk he was taking. After requesting psychological support, Ali A. appeared “worried and regretted having gotten involved with his testimony.”84

Incriminating Evidence

Despite the intimidation attempt, in early March, UNITAD reported that it had identified six more witnesses willing to testify.85 Some testimonies were indirect, such as that of Mohammed S. The most relevant was that of Othman K., who in 2015 worked in a toy store 30 meters from the Sayydat Al Jamila roundabout in the Al Zuhur neighborhood, where the Islamic State had set up an information point. Like other witnesses, Othman said he had seen the brothers there, where propaganda and execution videos were shown. “Yasir used to be at the information point. But I didn’t see him armed. He monitored for the organization, to see what we were doing,” Othman told the Portuguese judge.86 “He was a secret watchman. I saw him get into an ISIS car.”87

As for Ammar Ameen, in addition to seeing him armed and handing over a CD with a recording that was shown on the television screens (at the Islamic State information point at the Sayydat Al Jamila roundabout in Al Zuhur), Othman recalled how one day, when he had his shop open during sunset prayer to serve a customer, Ammar (then a member of Al Hisbah) and another terrorist named Abu Muslim put him in a van to be punished for the offense. “I was the first to get in. Then they picked up 12 more people in the area. They saw who was smoking, who wasn’t going to the mosque for prayer, and ordered them into the car,” Othman said.88 Ammar drove them to the Al Zuhur mosque. Othman recounted the terror he felt at being taken. “It was the feeling of someone walking straight to death. I didn’t know what was going to happen to me: whether they were going to whip me, whether they were going to arrest me, what my fate would be.”89

Outside the mosque, the 13 men were lined up in a row. “When people came out, they said we were negligent, renegades, that there were smokers among us. Then we were whipped in front of everyone.”90 Othman received 33 lashes on his back. “With each lash, I writhed, feeling a rage that I had to swallow. I wanted to fight back, but I controlled my nerves.”91

Othman was released at the end of the day and was unable to work for a week. When he returned to the shop, he was visited by Nafee, and it was then that he learned that they had been taken by the same person. “A vehicle stopped and Ammar got out. Then [Nafee] told me that it was Ammar who had taken him along with Yasir, and I told him that it was him who had taken me too.”92 Due to the trauma, he sold the store and left Mosul.93

In total, the investigation conducted by UNITAD in Iraq led to the identification of 11 witnesses who provided incriminating evidence of the conduct of Yasir Ameen and Ammar Ameen.94 In addition to Ali A., two other witnesses were intimidated by relatives of the brothers. The first was Nashwan A., a retired police officer, who was contacted by a 60-year-old man and two cousins of the suspects who asked him to withdraw the allegations against Ammar and Yasir—which Nashwan A. refused to do.95 The other was the Mukhtar of Al Zuhur, Nashwan A., who was visited at his house by Ammar and Yasir’s parents and one of their brothers on the eve of his deposition. With them were four defense witnesses who tried to convince him that the suspects were innocent.96

On April 6, 2022, Ammar and Yasir’s parents went to the UNITAD premises, where they asked to speak to “Interpol officials” about their sons’ case. The next day, Judge Raed Hamid al-Musleh summoned Ammar and Yasir’s parents and siblings to court and warned them that “they would be arrested for interfering with the course of justice if they contacted any more witnesses.” According to the UNITAD report, the family showed “remorse and promised to stop.”97

An Exemplary Example of Cooperation

The case’s international judicial cooperation went beyond UNITAD. Through the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Judicial Police learned that Operation Gallant Phoenix (OGP) had found the original propaganda video produced by the Islamic State in which Yasir Ameen appears holding a gold coin.98 Although OGP’s initial focus was to monitor the flow of foreign terrorist fighters to Syria and Iraq—as well as their return to their countries of origin—one of its objectives was also to “collect and make available” to the countries participating in the mission “photographs, documents, files, or computer media” that could constitute evidence for judicial investigations.99 To ensure the chain of custody of evidence, OGP houses representatives from U.S. government agencies, namely the Department of Justice, represented by the FBI.

In January 2022, the FBI sent to Portugal a copy of a device containing the video originally released by the Nineveh Information Agency. “In early 2019, Coalition Forces received media from suspected fighters, ISIS family members, and other non-combatants fleeing the ISIS enclave and other parts of the Middle Euphrates River Valley. Items collected include electronic devices, hard copy documents, and other personal property.”100 Documents obtained by OGP had been used in terrorism cases in Europe. This was the case in the trial that led to the conviction of Hicham El Hanafi101 in France, and in the trial of individuals involved in the Bataclan attack in Paris.102

The video, along with documents obtained by UNITAD, victim statements, and testimonies from those who recognized Ammar Ameen and Yasir Ameen as members of the Islamic State, were fundamental to their indictment and their January 2024 sentencing to 16 and 10 years in prison, respectively, for the crime of joining an international terrorist organization and war crimes committed in Iraq.103

The cooperation with UNITAD was particularly significant. Without it, Portuguese authorities likely would not have been able to obtain the evidence needed to arrest and convict two former members of the Islamic State. The way in which the documents were obtained and the testimonies recorded complied with all the necessary legal requirements to ensure that the validity of the evidence and statements would be unassailable in court. “This ruling is Portugal’s first conviction of a perpetrator on charges of war crimes. It marks a milestone along the path made possible thanks to the unique partnership between UNITAD and Iraq. The Iraqi Judiciary and the [UNITAD] Team have been extending crucial support to accountability processes in third states with competent jurisdictions to prosecute international crimes committed by ISIL in Iraq,” said Special Adviser and Head of UNITAD, Christian Ritscher, in March 2024.104

UNITAD also played an important role during the trial. Judge Raed Al-Mosleh “facilitated for the defense witnesses to testify remotely, during the proceedings, from his courthouse in Mosul, which was the first time for the Iraqi judiciary to arrange remote witness testimonies using video conferencing. In addition, UNITAD’s lead investigator gave key expert testimony during the trial before the Portuguese court.”105

The conviction in Portugal was the latest in a series of cases supported by UNITAD in cooperation with the Iraqi authorities. “The Team supported 17 cases in third state jurisdictions that were under investigation and led to indictments. Fifteen of these cases ended in convictions of ISIL members or affiliates.”106 m

The End of the Mission

Despite successful collaboration with third countries, relations between UNITAD and the Iraqi authorities grew increasingly tense over the years. The country does not have a law that allows convictions for so-called “international crimes”—such as crimes against humanity or genocide—and the parliament has not passed legislation to that effect. Since Iraq uses the death penalty as a form of punishment, which goes against U.N. policy, UNITAD was also reluctant to share the evidence it had obtained during its mandate with Iraqi authorities due to fear that evidence would be used to sentence convicted suspects to death.107

With the relationship at an impasse, on September 5, 2023, Iraq asked the U.N. Security Council to renew UNITAD’s mandate for only one more year and to order the handover of the evidence gathered so far to the Iraqi judicial authorities,108 “including witness testimony and information related to enhanced evidence detection and analysis and to the use of technology.”109 In a letter addressed to the President of the Security Council, Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Fuad Mohammad Hussein, also requested that the Investigative Team abstain from sharing “evidence with third countries” during the transition period and “to disclose to the Government the nature of the evidence” it has “shared with third countries.”

UNITAD’s mandate ended on September 17, 2024, with Special Adviser and Head of UNITAD Ritscher lamenting that he did not have time to complete the mandate given when the organization was created. “Is the work done? Not yet, this is pretty clear,” he said.110 “We will not achieve a completion of all investigative lines,” nor other projects such as creating a central archive for millions of pieces of evidence.111 This ultimately affected “the overall accountability efforts that the Team was created to support.”112 Between 2017 and 2024, the organization investigated 67 mass graves in areas previously controlled by the Islamic State in Iraq, collected testimonies from survivors, and digitized more than 15 million pages of documents. The volume of data reaches 40 terabytes.113

From Iraq’s perspective, UNITAD had not successfully cooperated with Iraqi authorities and was no longer needed. “In our view, the mission has ended and we appreciate the work that has been done and it’s time to move on,” said Farhad Alaaldin, foreign affairs adviser to the prime minister, in March 2024. The official added that the mission “didn’t respond to repeated requests for sharing evidence.”114

Conclusion

In February 2025, the Lisbon Court of Appeal upheld the prison sentences imposed on the two Iraqi brothers.115 n Both sides—the Public Prosecutor’s Office and Yasir and Ammar—appealed to the Supreme Court of Justice, and the case is waiting for a final decision. At the same time, the Portuguese case has been highlighted by international experts as an example of judicial cooperation. Portuguese State Prosecutor Cláudia Porto presented it at the Eurojust/United States/Genocide Network Meeting on Battlefield Evidence held in April 2024;116 at the NATO Battlefield Evidence Working Group in March 2025; and at the Council of Europe Committee on Counterterrorism (CDCT) Secretariat and the International Institute for Justice and the Rule of Law in October 2025,117 which was hosted by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Justice with the support of the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Counterterrorism. As recently as December 2025, the case was discussed at a United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism conference in Istanbul, Turkey,118 as a model form of cooperation.

This case is a clear example of how international judicial cooperation will be crucial in ensuring that victims of crimes committed by members of the Islamic State can find peace in the knowledge that justice has been done. The courage shown by victims and witnesses who, even under threat, agreed to tell their stories to Portuguese authorities and contributed to the administration of justice, is a powerful example for all those who fear exposing what they have been through to society.

The case is also a warning to all members of the terrorist group who managed to escape from Syria and Iraq to Europe and, probably, to other parts of the world where they continued their lives, hiding in plain sight. Organizations such as UNITAD and operations such as OGP have dedicated—and at least in the case of OGP continue to dedicate119—time and resources to collecting and preserving information obtained in conflict zones so it can be used as evidence in court. It may take years before other members of the Islamic State are discovered, making it important to develop—and maintain—an international campaign to identify these individuals. It is also important for countries to continue to deepen judicial cooperation and share knowledge and practical examples.

The case also shows how it will be necessary to engage Iraqi authorities in future cases that involve historical Islamic State activity in the region. With the end of UNITAD’s mission in Iraq and the handover of the huge volume of data collected over the last few years to Iraqi authorities, countries interested in prosecuting former members of the Islamic State will have to obtain cooperation and data through Iraq’s courts.

The type of data and records discussed in this article will be of the utmost value to police and intelligence services from other countries that are dedicated to identifying former or current Islamic State members resident in or with ties to their nations. The evidence gathered by UNITAD—and by OGP—will likely remain crucial resources in ongoing or future Islamic State investigations. Those same records will also be relevant to historians and researchers seeking to reconstruct the dark years of contemporary history when a terrorist group exercised effective control over a large swath of territory between Syria and Iraq. CTC

Nuno Tiago Pinto is an author and former journalist. He authored the books Rui Pinto, o hacker que abalou o mundo do futebol (Rui Pinto, the hacker who shook the world of soccer); Heróis Contra o Terror: Mário Nunes, o português que foi combater o Estado Islâmico (Heroes Against Terror: Mário Nunes, the Portuguese that went to fight the Islamic State); Os combatentes portugueses do Estado Islâmico (The Portuguese fighters of the Islamic State); and Dias de Coragem e Amizade – Angola, Guiné e Moçambique: 50 Histórias da Guerra Colonial (Days of Courage and Friendship – Angola, Guinea and Mozambique: 50 Stories from Portuguese Colonial War). X: @ntpinto23

© 2026 Nuno Pinto

Substantive Notes

[a] Ahmed is the pseudonym chosen by the author to identify a protected witness in the judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB. He is identified in court documents as “Witness L.”

[b] Ammar A. Mohammed Ameen, born July 24, 1987, Mosul, Iraq; also known as Ammar Abdullah Al-Kuyani.

[c] Real name Yasir A. Mohammed Ameen, born July 2, 1989, Mosul, Iraq; also known as Yasser Abdullah Al-Kuyani.

[d] At the time, Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras was the Portuguese Border Police and Administrative Authority for immigration matters. It has since been dissolved and its powers distributed among different entities.

[e] The Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal (Central Department of Investigation and Penal Action) is the Portuguese Public Prosecutor’s Office responsible for coordinating and directing the investigation and prevention of violent crime, highly organized economic and financial crime, and crime of particular complexity.

[f] Between January 1, 2016, and September 30, 2017, 1,507 refugees were relocated to Portugal through the European Union Relocation Program: 315 were relocated from Italy and 1,192 from Greece. Two out of five of those refugees left the country without permission to other E.U. states. “Portugal já recebeu este ano 1507 refugiados recolocados da Grécia e Itália,” Lusa, November 15, 2017; “Dois em cada cinco refugiados recolocados em Portugal abandonam o país,” Lusa, May 9, 2017.

[g] Following his resignation, Costa was elected President of the European Council in June 2024.

[h] UNITAD’s mandate ended on September 17, 2024.

[i] Born in Baghdad, on March 27, 1956, Farih Al Fayyadh was the Iraqi Prime Minister National Security Adviser until July 2020 and chairman of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), an Iranian-backed paramilitary umbrella group. In January 2021, he was sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control as PMF leader for his connection to serious human rights abuse during the October 2019 protests in Iraq. He is the chairman and founder of the political party Ataa Movement.

[j] In his testimony, Nashwan A. told Portuguese authorities that he was elected Mukhtar of the Al Zuhur neighborhood on April 16, 2018. His primary function was to take care of administrative issues regarding marriages, divorces, ID cards, house and business rentings as well as security-related issues. “The security authorities ask me to investigate certain individuals and I present them the informations I collect,” he said. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, p.192-206

[k] In June 2021, Karim Khan took office as chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. Three months later, he dropped the investigation about U.S. use of secret prisons in Poland, Romania, and Lithuania. In early 2023, he applied for an arrest warrant against Vladimir Putin forwar crimes committed in Ukraine. In May 2024, he issued arrest warrants against Hamas leaders Yahya Sinwar, Mohammed Al-Masry, and Ismail Haniyeh, as well as against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Israeli Minister of Defense Yoav Gallant. On February 13, 2025, Karim Khan was sanctioned by the U.S. government due to ICC investigations of Israel. Marlise Simons, “Who is Karim Khan, the I.C.C. Prosecutor,” New York Times, May 20, 2024; Stéphanie Maupas, “Le procureur de la CPI suspend l’enquête sur les tortures dans les prisons secrètes de la CIA,” Monde, September 28, 2021; “Statement of ICC Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan KC: Applications for arrest warrants in the situation in the State of Palestine,” International Criminal Court, May 20, 2024; Jennifer Peltz and Fatima Hussein, “US hits international court’s top prosecutor with sanctions after Trump’s order,” Associated Press, February 13, 2025.

[l] The letter also stated that “the foregoing materials are provided solely for the Public prosecution Service ongoing investigation as referenced in the request for judicial cooperation of 24 March 2021 cited above, and any criminal proceedings that may arise therefrom. UNITAD’s written approval is required for any other use of these materials, and nothing in or relating to this exchange of correspondence may be understood as a waiver, express or implied, of any of the privileges and immunities enjoyed by the United Nations, including UNITAD. This information may not be shared with any authority of any other State.” All the documents and translations were gathered in Appendix D, pp. 1-114.

[m] In 2021, the first conviction of an Islamic State member for committing genocide against the Yazidis was issued by the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt, Germany. Islamic State member, Taha Al-Jumailly was found guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide following a 19-month trial. Other significant convictions, which UNITAD’s support contributed to, include a conviction by the Swedish district court in 2022 of an Islamic State female member for her failure to protect her 12-year-old son from being recruited and used as child soldier by the Islamic State. Also, in June 2023, the German Higher Regional Court of Koblenz convicted an Islamic State female member, Nadine K., a German national who was found guilty of aiding and abetting genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes for the enslavement and abuse of a young Yazidi woman in Iraq. The Yazidi victim, who was enslaved by the Islamic State couple for three years, participated in the case as a co-plaintiff, and thus, witnessed her day in court. “A Triumph for Accountability Efforts: How Iraq and UNITAD supported Portugal’s First Conviction for International Crimes,” United Nations, March 3, 2024.

[n] The whereabouts of the third brother mentioned in this article, Fouad Ameen, were unknown, and he remained the subject of an arrest warrant issued by the Iraqi authorities.

Citations

[1] Diogo Barreto, “Irmãos Iraquianos condenados a 10 e 16 anos de prisão,” SÁBADO, January 18, 2024; Tribunal Criminal de Lisboa, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, January 18, 2024.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, p. 6,211-6,214.

[4] Ibid., Appendix DMF, Vols. 1 and 2.

[5] Ibid., pp. 6,215-6,216.

[6] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF Vol. 2, pp. 255-274.

[7] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF Vol. 2, pp. 255-274.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 1, pp. 3-6.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF Vol. 2, pp. 255-274.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix C, p. 16; Tribunal Administrativo e Fiscal de Sintra, judicial inquiry 1448/19.2BELSB, p. 16.

[17] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 1, pp. 3-6.

[18] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 1, pp. 3-6.

[19] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix G-1, pp. 40-43.

[20] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix G-2, pp. 45-49.

[21] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 1 to Vol. 8.

[22] Valentina Marcelino, “Costa e Sampaio estiveram com iraquiano quando este já estava a ser investigado por terrorismo,” Diário de Notícias, September 5, 2021; Hugo Franco, “Terrorismo. Iraquiano que tirou selfies com Costa e Marcelo ‘não representava uma ameaça à segurança,’” Expresso, September 7, 2021; António Costa, “Portugal tem sido exemplar no acolhimento a refugiados …,” X, January 30, 2018.

[23] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix G-1, p. 81.

[24] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 1, pp. 146-148.

[25] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix A, pp. 2-31.

[26] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix 1, pp. 12-14; Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, December 30, 2024, p. 222.

[27] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix C, pp. 57-59.

[28] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 21, p. 5,996.

[29] Resolution 2379 (2017), adopted by the Security Council at its 8052nd meeting, on September 21, 2017.

[30] Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, December 30, 2024, p. 250.

[31] Ibid., p. 258.

[32] “UNITAD investigation report, FIU-3 (Mosul Team),” Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 20, pp. 5,754-5,756.

[33] Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, December 30, 2024, p. 258.

[34] Ibid., p. 255.

[35] Ibid., p. 256.

[36] Mohammed S. testified on March 24, 2022. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 16, pp. 4,457-4,458; Appendix DMF, pp. 144-172.

[37] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 16, pp. 4,457-4,458; Appendix DMF, pp. 144-172.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ammar R. testified on March 24, 2022. Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 16, pp. 4,456-4457; Appendix DMF, pp. 124-143.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 16, pp. 4,457-4,458; Appendix DMF, pp. 144-172.

[50] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 10, pp. 2,709-2,716.

[51] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 16, pp. 4,457-4,458; Appendix DMF, pp. 144-172.

[52] Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, December 30, 2024, p. 259.

[53] Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, December 30, 2024, p. 259.

[54] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 8, p. 2,305.

[55] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 9, pp. 2,501-2,502.

[56] Ibid., pp. 2,685-2,686.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 8, p. 2,305.

[61] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 10, pp. 2,908-2,912.

[62] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 12, p. 3,292.

[63] Ibid., p. 3,319.

[64] Audio recording of Yasir Ameen interrogation, September 2, 2021.

[65] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 12, p. 3,326.

[66] Ibid., p. 3,472.

[67] Ibid., pp. 3,524-3,526.

[68] Witness Protection Law, artº19, nº2.

[69] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 13, p. 3,694.

[70] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 2-28.

[71] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 29-68.

[72] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 2-28.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 29-68.

[75] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 2-28.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 29-68.

[78] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 2-28.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ali A. testimony, Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 69-123.

[81] Ibid.

[82] UNITAD Incident Report, Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 13, pp. 3,750-3,752.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 13, p. 4,362.

[86] Othman K. testimony, Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Appendix DMF, pp. 315-333.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Ibid.

[89] Ibid.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Ibid.

[92] Ibid.

[93] Ibid.

[94] UNITAD investigation report, FIU-3 (Mosul Team), Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 20, pp. 5,754-5,756.

[95] Ibid.

[96] Ibid.

[97] Ibid.

[98] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 13, p. 4,338.

[99] Acórdão do Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa, pp. 132, 339. On Operation Gallant Phoenix, see Óscar López-Fonseca, “Spain helping US identify European jihadists in Syria,” País, March 4, 2019; Elise Vincent and Christophe Ayad, “‘Operation Gallant Phoenix’, la guerre secrète des données contre les djihadistes,” Monde, March 25, 2021; David Martin, “German intelligence targeting returning jihadis – report,” DW, March 2, 2018.

[100] Departamento Central de Investigação e Ação Penal, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, Vol. 13, pp. 4,234-4,236.

[101] Acórdão do Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa. For more about the case of Hicham El Hanafi, see Nuno Tiago Pinto, “The Portugal Connection in the Strasbourg-Marseille Islamic State Terrorist Network,” CTC Sentinel 11:10 (2018).

[102] Acórdão do Tribunal da Relação de Lisboa, p. 340.

[103] Barreto; Tribunal Criminal de Lisboa, judicial inquiry 99/17.0JBLSB, January 18, 2024.

[104] “A Triumph for Accountability Efforts: How Iraq and UNITAD supported Portugal’s First Conviction for International Crimes,” United Nations, March 3, 2024.

[105] Ibid.

[106] Ibid.

[107] Timour Azhari, “UN mission probing Islamic State crimes forced to shut in Iraq,” Reuters, March 20, 2024.

[108] “Security Council Extends Mandate of Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/ISIL, Unanimously Adopting 2697 (2023),” United Nations, September 15, 2023.

[109] “Letter dated 5 September 2023 from the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Security Council, September 7, 2025.

[110] Azhari.

[111] Ibid.

[112] “Letter dated 14 March 2024 from the Special Adviser and Head of the United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations, March 14, 2024.

[113] Ibid.

[114] Azhari.

[115] “Tribunal da Relação confirma pena aos irmãos iraquianos acusados de organização terrorista,” Diário de Notícias/Lusa, February 12, 2015.

[116] Eurojust – United States – Genocide Network Meeting on Battlefield Evidence, Outcome Report, 18-19 April 2024.

[117] CoE-IIJ Comparative Practices on the Use of Information Collected in Conflict Zones as Evidence in Criminal Proceeding, 16-17 October 2025.

[118] Claudia Oliveira Porto, “Honored by United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT)’s invitation to present, in Istanbul, Portugal’s experience in criminal cooperation with the Iraqi judicial authorities,” LinkedIn, December 2025.

[119] Hon Judith Collins KC, Hon Mark Mitchell, and Rt Hon Winston Peters, “Operation Gallant Phoenix deployment extended,” New Zealand Government, June 12, 2025.

Skip to content

Skip to content