Abstract: The Islamic State’s recruitment of children is a challenge with no easy solutions. Islamic State foreign fighter records show that foreign children fighters tend to be, as expected, less well-educated, less likely to have good employment, more likely to be students, and less likely to be married than adult foreign fighters. Interestingly, they were slightly less likely to express a preference to be suicide bombers or fighters, arrived later, had a similar amount of self-declared jihadi experience, and came from countries in different proportions than did their older counterparts. Continued research on this important subject, as well the focus of policymakers on the challenges of child returnees, will remain an important part of future counterterrorism efforts.

The group known as the Islamic State rose to international infamy on the back of a number of factors: the attraction of thousands (if not tens of thousands) of foreigners to its ranks, a campaign of grotesque violence perpetrated against a diverse array of individuals, military victories against western-trained security forces, and a wide-ranging media effort both on the ground and online. One strategy employed by the group that garnered a significant amount of media attention was its exploitation of children.

This study is certainly not the first to focus on the Islamic State’s use of children. Indeed, scholars and practitioners have conducted a number of studies on how the Islamic State recruits and uses children for a variety of organizational purposes.1 These works build on a still larger literature that discusses the role of children in warfare around the world.2 And even within the Iraq and Syria landscape, the Islamic State is not the only entity that draws in and employs children.3 The contribution of this article is to add a data-driven picture of a subset of children within the Islamic State organization: those who traveled to the conflict zone either alone, with friends, or with family, to join the Islamic State as fighters. This contribution is enabled by an examination of Islamic State personnel documents for individuals entering the caliphate from 2013-2014.

Exploring the Data: Age

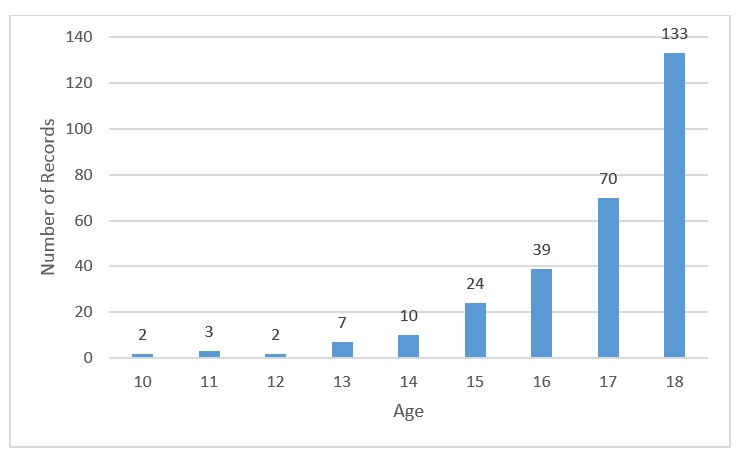

This article examines data from the CTC’s previous work on the personnel records of Islamic State foreign fighters, which contained just over 4,100 records, but specifically focuses on the smaller subset of children.4 It is important to recognize that this data only includes male children, as no females were recorded in this batch of Islamic State personnel documents, whether children or adults.a For purposes of this analysis, children are defined as those 18 years of age and under.b To identify the children in the dataset used for this article, two key fields were leveraged: the year of birth of the fighter and the year in which they entered Islamic State territory, with the former subtracted from the latter to arrive at an estimated age for each individual in the dataset. Out of the total dataset of 4,100 fighters, just 267 were 18 years of age or under. Some individuals in the CTC’s dataset did not have a year of entry on their personnel record. In these cases, the estimate of 2013 was used, adding an additional 23 individuals to the dataset, for a total of 290 children in the main dataset used for the subsequent analyses.

The age breakdown for these 290 child fighters is shown in Figure 1. While most of the individuals in this dataset are estimated to be right at age 18, there are still a large number of records for those under 18, and even some as young as 10. The diminishing number of entrants as the age group becomes younger and younger is to be expected, as these records are for those registered as fighters. There were children of all ages entering Islamic State territory to live, but since these records reflect fighters, they naturally trend toward the older age ranges. It is also important to remember that this dataset generally represents only foreign enrollees into the Islamic State’s records and is unlikely to be representative the population of local child fighters. In other words, the data presented here provide interesting insight, but are not intended to be a comprehensive overview of children in the Islamic State.

Figure 1: Age Breakdown of Children in Islamic State Personnel Records

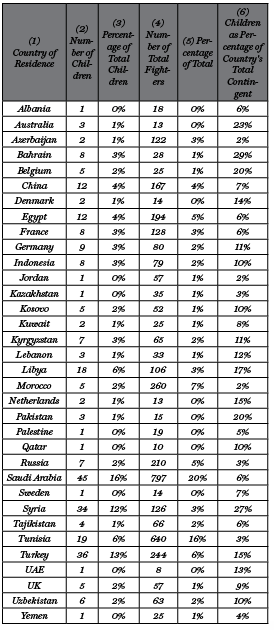

Exploring the Data: Country of Residence

The next descriptive marker of interest is the countries of residence for the children in the dataset.c A total of 278 records contained information on the country of residence, which is shown in Table 1. Beyond simply the number of records pertaining to each country, which is shown in the second column, a number of other columns offer additional context and insight into the dataset. To obtain the percentage of children coming from a particular country, the third column takes the number of children from a country and divides it by the total number of children in the dataset (278). The fourth and fifth columns show the total number of fighters in the data (adults and children) and the percentage of the total representing each country. Finally, the fifth column computes the percentage that children make up of each country’s foreign fighter contingent in the dataset.

Table 1:Descriptive Statistics for Islamic State Children Fighters, by Country of Residence

A few results are worth highlighting. First, children are present from 34 different countries. While the fact that children from such a wide range of countries are present in the dataset is concerning, it is also important to remember that the overall dataset contains entries of individuals from 69 total countries. In other words, only 49 percent of the countries in the larger dataset contained a personnel record for a child. While the appeal of this group to children is concerning, it is obviously not as widespread as the appeal of the group overall.

One category of likely interest is the number of children coming from Western countries.d There are eight Western countries in the dataset, which is 23 percent of the countries present. However, these eight Western countries account for only 12 percent of the children in the dataset. This suggests that although the West does have a problem with children seeking to join and fight on behalf of the Islamic State, it appears to be less significant of an issue than it is for non-Western countries.

The second insight from Table 1 can be observed by comparing the third and fifth columns to see from which countries a disproportionate amount of children are coming when compared to the overall number of foreign fighters in the dataset. For example, consider Turkey. There are 36 children, about 13 percent of the total number of children in the dataset, who list Turkey as their country of residence. In the overall dataset, there were 244 Turkish foreign fighters, which is approximately six percent of the overall number of fighters in the dataset. If the expectation were that the percentage of children from any one country in the data should match the percentage of overall fighters from that same country, the result with Turkey would stand out. About twice as many children appear in the dataset than expected given the overall presence of Turkish foreign fighters in the broader dataset.

Other countries that stand out as having more children than expected are Libya (six percent of the children/three percent overall) and Syria (12 percent children/three percent overall).e In the case of Syria and Turkey, it is likely that the proximity of the battlefield played a major role in facilitating the entry of children into the Islamic State’s hands. An explanation for the inequity between children and adults in the Libyan contingent is harder to explain. Clearly, the chaotic environment in Libya would allow for easier exit of the country by individuals of all ages, but other countries where domestic stability is lacking (Pakistan, Yemen) do not display a similar pattern.

There are also some countries where the number of children is less than expected: Morocco (two percent children/seven percent overall), Russia (two percent children/five percent overall), Saudi Arabia (16 percent children/20 percent overall), and Tunisia (six percent children/16 percent overall). The pattern here is not as clear, although each of these countries has relatively effective security services, which may make it difficult for children to travel to a warzone, even in the company of a parent or adult.

Finally, the sixth column shows what percentage of a country’s overall contingent of foreign fighters is made up of children. The average percentage across all countries that have at least one child in the dataset is 10 percent. When it comes to individual countries, one caveat that is important to keep in mind is that the numbers in column (6) for some countries are more dramatic because of the very small number of fighters overall. That said, there are several countries that seem to stand out. In the case of Syria, 27 percent of the contingent is 18 or under. Other countries with comparatively large contingents of children include Bahrain, Belgium, Australia, Libya, and Turkey. The diversity of countries in this list is a reminder of the broad challenge facing the world, not simply when it comes to preventing foreign fighter travel, but also toward reducing and dealing with the exploitation of children by terrorist groups like the Islamic State. It is not just children from the Middle East who are facing this problem.

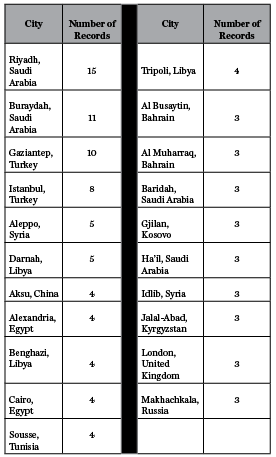

While the fact that children come from particular countries is interesting, looking at the descriptive statistics at the country level of analysis hides some interesting nuance. The data contains information about the city from which an individual comes, allowing for a more detailed look at relatively micro-level geographic pockets where these children registering with the Islamic State originate. As shown in Table 2, several cities seem to face a larger challenge when it comes to children joining the Islamic State. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, is the city with the most youth overall in the dataset, with 15 children coming from Riyadh. Following Riyadh, the next cities with most children in the dataset are Buraydah, Saudi Arabia (11), Gaziantep, Turkey (10), and Istanbul, Turkey (8).

Exploring the Data: Marital Status

When comparing the marital status of the children in the dataset to the broader Islamic State captured records, the expectation is that the proportion of married individuals should be much smaller among children. This is exactly what the data show. For the 260 children in the dataset for whom a marital status is listed, only 14 (5.4 percent) are listed as having been married. This is compared to a rate of about 33 percent in the larger dataset.5 Digging just a bit beneath the surface, the rate of married children among the Islamic State’s fighters may even be lower. One of the children, 10 years of age, is listed as being married on the entry form, which may have been incorrectly entered, especially given that the rest of the 14 married children are all 16 and older, which is more consistent with expectations.

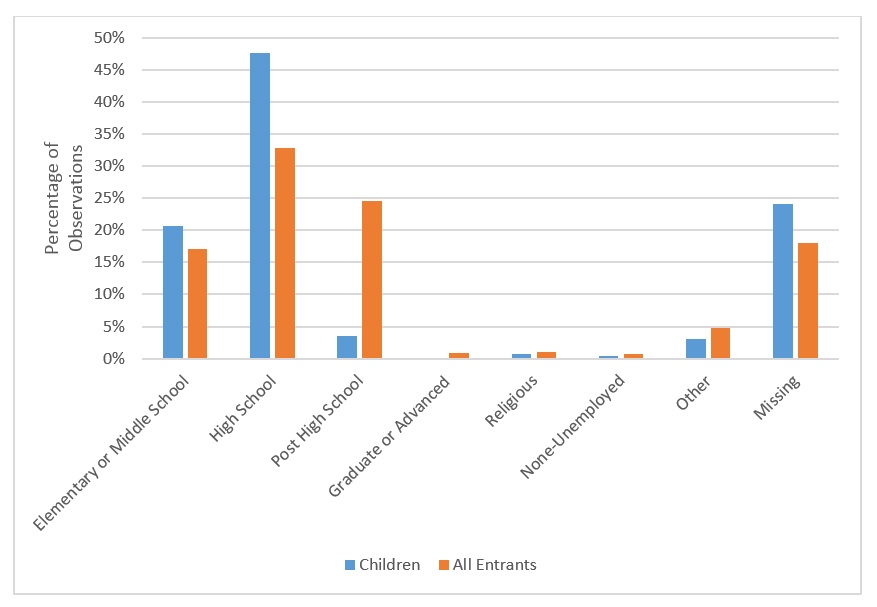

Exploring the Data: Education

When it comes to the education level of the Islamic State children, the expectation would be that, given the younger population, the distribution of educational attainment should be weighted more heavily towards the lower end when compared with the general population of Islamic State fighters. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of educational level for both the children in the Islamic State’s entry records and the general population.

Figure 2: Education Level, Children vs. All Entrants

The data largely conforms to this expectation, with the population of Islamic State children tending to have less education than the rest of the population. While not surprising, this serves as a reminder of two significant points about the children recruited by the Islamic State. First, although education is not a vaccine against radical ideology as evidenced by the relatively high levels of schooling amongst all Islamic State fighters,6 clearly the children are least well equipped from a radicalization perspective to bring greater knowledge to bear against the narrative being pushed by the Islamic State. Second, when considering the challenge of returning fighters, those children that survive the battlefields of Iraq and Syria and are able to return to their home countries will be at a disadvantage. They will have left home with lower education levels, lost anywhere from months to years in terms of their ability to catch up, and gained skills that are not particularly marketable upon their return. Successful reintegration of these children will likely need to address these economic and educational challenges.

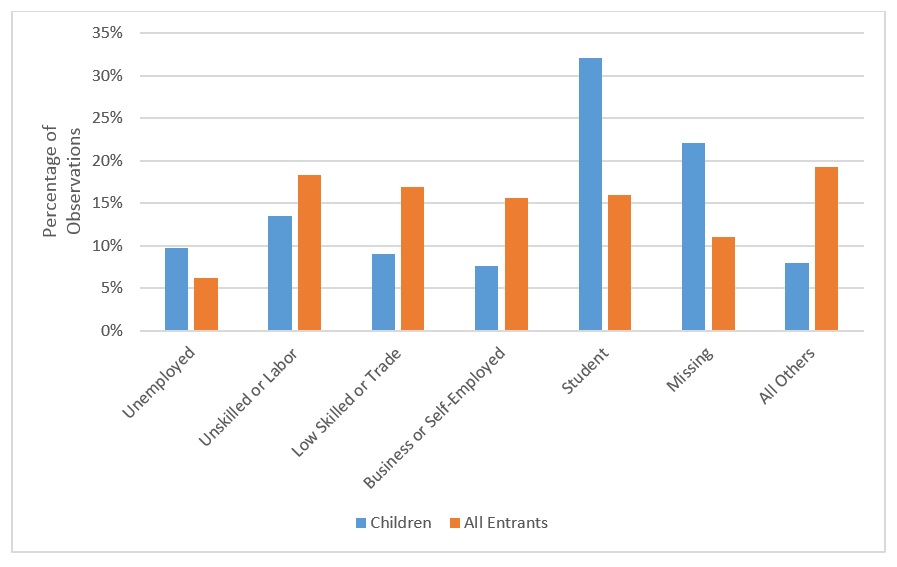

Exploring the Data: Employment

Most of the children, like the general cohort of entering Islamic State fighters, can be grouped into a few categories in terms of employment: unemployed, unskilled, low skilled, business or self-employed, student, missing, and all others. The ‘all others’ category is a catch all and includes individuals who claimed to have a media background, work in computers, or in religious fields.7 The tabulation for this data appears in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Occupation Categories of Children Compared to Incoming Islamic State Population

Generally speaking, the children in the dataset tend to be unemployed, not answer the question (presumably they are without employment, but not seeking employment either because they are living with their parents or are otherwise cared for), or students. This latter category is where the starkest difference existed between the children and the rest of the incoming foreign fighter population. Children are more likely to respond that they are students than anything else. Though the fact that they are in school is not surprising, it does call to attention the fact that many of them are in a state of discovery and learning, which may make them susceptible to the skilled recruitment pitch of an Islamic State recruiter or the propaganda produced by the group.

Exploring the Data: Jihad Experience

One final category to consider is whether or not any of these children claimed to have participated in jihad before. Of the 290 children in the dataset, 10 percent did not respond, 81 percent said no, and just under nine percent said that they had participated in jihad previously. This number is not very different than the 9.6 rate of prior participation in the overall dataset, which is surprising. The breadth of the experience is also impressive given the age of the children: seven in Libya, five for Jabhat al-Nusra, seven for other groups in Syria, two in Waziristan, and one each in the “Levant,” Afghanistan, and Lebanon. And, while most of those who claimed prior jihadi experience were 18, one as young as 13 stated that he had prior experience. While it is impossible to verify these claims, the mere possibility is suggestive of a multi-generational fight, as younger individuals continue to be exposed to jihadism.

Exploring the Data: Travel to Iraq and Syria

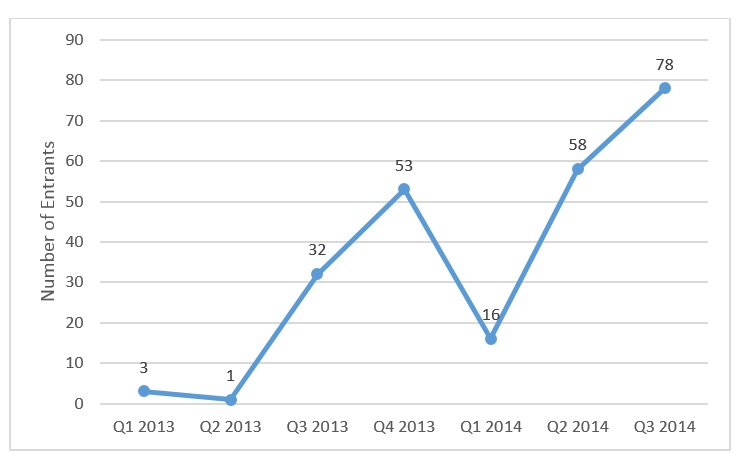

In the broader Islamic State foreign fighter dataset, about 39 percent of the fighters arrived in 2013, while the remaining 61 percent arrived in 2014. This distribution is slightly different when it comes to the children in the dataset. About 30 percent arrived in 2013, while 70 percent arrived in 2014. In other words, while more fighters in the overall dataset arrived in 2014 than in 2013, this dynamic was even more pronounced among the children in the dataset. One possible explanation is that family travel to the conflict zone increased as the Islamic State took over more territory and the vision of the caliphate, though not realized until the end of June 2014, became clearer to all observers. Another possibility that is not mutually exclusive is that the travel routes to Syria were clearer in 2014 than in 2013, making travel for children easier to accomplish.

There is one oddity related to the timing of the travel of children that bears mention. To see this, the data on when the children entered was broken down by quarters, beginning with the first quarter of 2013 and continuing through the third quarter of 2014. That information, presented in Figure 4, shows a mostly consistent increase in the flow of child fighters into the conflict zone, with one exception. The number of entrants declines very steeply in the first quarter of 2014, before rebounding the next quarter. This decline also occurs for all other fighters in the broader dataset, so it does not seem that it is specific to children. It could be the result of conditions on the ground, but may also be due to decreased record-keeping for other reasons.

Figure 4: Entries of Children, By Quarter

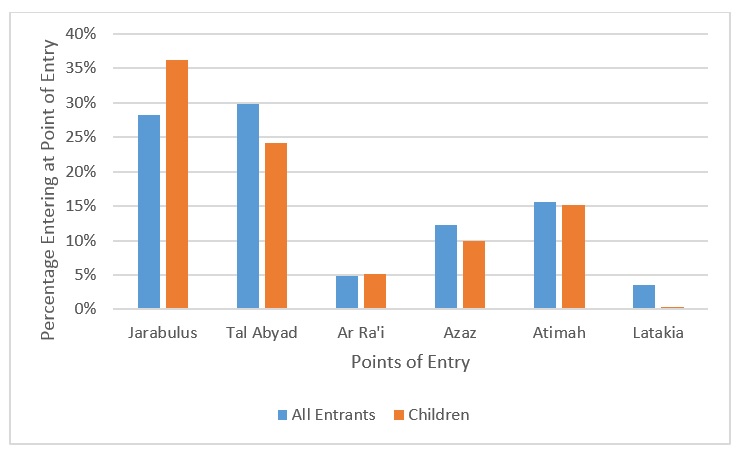

Given that the children tended to arrive slightly later in the range of time covered in the dataset, it would make sense that they would also have arrived in greater proportions at the border points that were more active in general in 2014: Jarabulus and Tal Abyad.8 This expectation is supported in the case of Jarabulus, but not in the case of Tal Abyad.

Figure 5: Point of Entry, All Entrants vs. Children

As can be seen in Figure 5, there are two points of entry where the number of entrants is mostly even: Ar Ra’i and Atimah. There are slight imbalances in the number of children entering the caliphate in the rest of the border crossing points. In Jarabulus, a greater proportion of children entered as compared to the proportion of all entrants who came through Jarabulus. However, in Tal Abyad, Azaz, and Latakia, the proportion of children is smaller when compared to all entrants. It is not immediately clear what explains this difference. It is possible that an entry point like Latakia, which experienced back-and-forth conflict during 2013-2014, was avoided by travelers with inexperience in favor of busier and more-well traveled crossing points. Some of the other border crossings did not experience such conflict, but either saw no imbalance between all entrants and child entrants or saw fewer children. Although the differences are small, understanding if and why children traveling into conflict zones choose different routes is an important focus worthy of additional research.

A follow on question to this observation about the more common border entry points for children is whether or not the data can say anything about who the children entered with. Unfortunately, there are few links in the data that specifically articulate whether one traveler knew or came with another. In the notes section of the Islamic State registration form, there are some indications. For example, one form noted that a 17-year-old male was “brought by his father, a former jihadist who was never detected by security services.” Another form simply noted that the child “came with family.” However, it also seems clear that some of the entering children were not with family. The comment section of one form relayed the child “doesn’t want to contact his family.” However, most forms are silent on any relationship between the children and their travel companions.

Information on the day the individual entered the caliphate, however, can offer some insights into the travels of the children in the dataset. Together with the border entry point, this data allows for an examination of the possibility of groups of children arriving on the same day, potentially having traveled in the same group.f

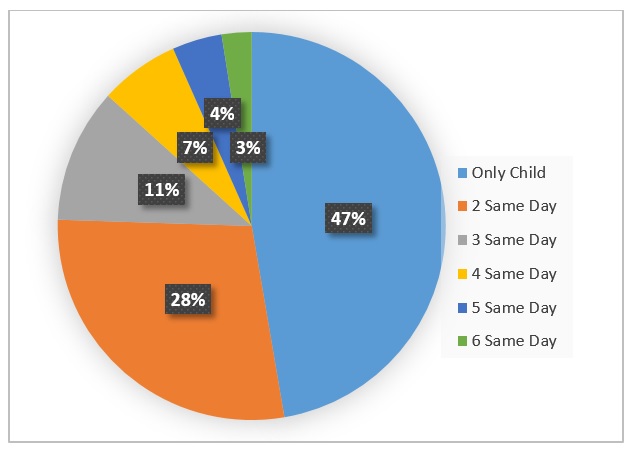

Figure 6: Number of Children Arriving on Same Day and Same Border Entry Point

First, as shown in Figure 6, 47 percent of all children arriving in the caliphate did so on a day when they were the only child crossing the border point. This suggests that the problem of children traveling to and entering the conflict zone during the early part of the Syrian civil war was not just about group travel, at least when it came to groups of children traveling together. A sizable number of children did not travel the final stage from Turkey to Syria with other children.

However, a second point of note is that 53 percent of all children arrived on a day and at a border point where at least one other child entered as well. At initial glance, this raises the possibility of children traveling together from countries of origin to the conflict zone. However, this does not appear to be the case, at least from the perspective of the CTC data on foreign fighters. If children who knew each other in another country traveled together all the way to the border point, then adding the nationality column to our analysis should not greatly alter the breakdown shown in Figure 6. However, when nationality is added to the mix, the percentage of children entering through the same border point on the same day as at least one other child from the same country as them is only 19 percent. This suggests that children arriving from the same country at the same border point on the same day is less common, although it does happen. The leading countries in the dataset that had multiple children show up on the same day are Turkey (4),g Saudi Arabia (3), Syria (3), Bahrain (2), Tunisia (2), and eight other countries with one occurrence each.h

Third, about 25 percent of children arrived on the same day and at the same border point as at least two other children. These relatively large groups raise additional questions that further research could address. Are there specific conflict routes traveled by children? Given that children were coming into the conflict zone, did the Islamic State establish special safe houses and routes for some of them? The data here do not answer these questions, but there are clearly research and policy implications emerging from them.

Before moving on, one of the examples cited above indicates that family travel, a child coming with a brother or father, also occurred in the data utilized here. While the data does not indicate if an individual arrived with others, we can at least see if children were the only arrivals on the border on a given day. Once the broader dataset of adult arrivals is taken into account, a child was the only entrant on four of 465 days on which at least one person entered.

Exploring the Data: Operational Preference

There were three categories under which each fighter could register: fighter, suicide fighter, and suicide bomber. Of those individuals 18 years old and under in the dataset who identified an operational preference, 254 indicated a willingness to be fighters, 13 suicide fighters, and 12 suicide bombers. Overall, 91 percent of the children in the Islamic State’s foreign registry files were listed as fighters. This is slightly more than the 89 percent of individuals in the overall dataset who elected to serve as fighters.

While the difference between the children and the rest of the entering population in terms of the proportion of fighters was small (about two percent), the fact that rate of suicide volunteering among children was less than that of adults raises a few interesting possibilities. Was the organization steering children away from suicide roles in order to preserve their long-term value to the organization? Were children more likely to be traveling with parents or others who did not approve of signing up as anything other than a fighter? Or was it simply a fluke? Of course, the organizational preference upon entry does not indicate that an individual would go on to fulfill that role (or not). Preferences may change over time, both on the part of the individual and the organization.

One additional angle explored was to further analyze the data to see if there was an age difference between children who ended up in the different organizational roles. If there were, it might provide some evidence that the group was coercing or enticing children into the most dangerous roles. Any results should be taken with a grain of salt, as there are small numbers of children in the two categories for suicide missions. However, the analysis revealed no statistical difference between the average ages of those who were placed in each operational category.

Conclusion

This article examined the CTC’s data taken directly from the Islamic State’s registration documents with a specific focus on those documents that identified a child. In doing so, it identified several expected ways in which children registering with the Islamic State as fighters from 2013-2014 differed from the rest of the incoming registrants to the Islamic State: they were less likely to be married, had less education, and tended to have an occupation status of “student” or “unemployed.”

This article also highlighted some intriguing findings: the amount of previous jihadi experience was as equally prevalent among the older children as among the rest of the entrants and children entered in greater proportion in 2014 as compared to the proportion of the rest of the traveling population. Additionally, children in this dataset came in disproportionate numbers (compared with the overall number of fighters from a country) from Bahrain, Belgium, Kosovo, Libya, and Turkey.

It has been an unfortunate fact of war that children are often enlisted to fight. Such a phenomenon is not new. In addition to this sad reality is the fact that the children themselves are faced with robbed futures, the terror of participating in brutal conflict, and often a lack of choice in being swept up in the conflict in the first place (or at least of sufficiently developed capacity to make such weighty decisions). In the case of the recruitment of children into terrorist organizations, these tragedies may be magnified even more. The Islamic State has shown a willingness to employ children as suicide bombers, assassins, and propaganda tools. For these children, as well as those who have worked in other capacities with or lived under the group’s control for the past several years, the nightmare is likely far from over. Continued research by scholars and increased attention from policymakers to understand and, to the extent possible, address this challenging issue will be worth the investment. CTC

Dakota Foster recently graduated from Amherst College with a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science and Asian languages/Civilizations. She was also selected as a recipient of a 2018 Marshall Scholarship and will be conducting graduate work at King’s College London and Cambridge University. She previously worked as an intern at the Combating Terrorism Center, the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, and the Washington Institute.

Daniel Milton, Ph.D., is Director of Research at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. He has authored peer-review articles and monographs related to terrorism and counterterrorism using both quantitative and qualitative methods. His published work has appeared a number of venues, including The Journal of Politics, International Interactions, Conflict Management and Peace Science, and Terrorism and Political Violence.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

Substantive Notes

[a] This is despite the fact that there were certainly females aged 18 and under traveling to Iraq and Syria to join the group. The records obtained by the CTC were only for fighters, and women were not recorded in this particular batch of data because they were not going to be assigned a formal fighting role in the organization during this period of time.

[b] The Convention on the Rights of the Child, the international convention that entered into force on September 2, 1990, defines children as “a person below the age of 18, unless the laws of a particular country set the legal age for adulthood younger.” The reason this study includes those who are also 18 years of age is because the way in which age is calculated leaves some room for error in the actual age of the entrant. In some cases, someone estimated by the authors’ method to be 18 may actually be 17. Given this lack of precision, the authors opted for the more expansive age range to make sure that the dataset was as inclusive as possible. This inclusiveness may result in a slight overestimation of children’s employment, education and marital status, so readers should be aware of this possibility in interpreting the results.

[c] As noted in the previous CTC reports that rely on the Islamic State personnel records, there are actually two fields that offer some insight into the geographic origins of fighters. The first is the “country of residence” field, which forms the basis of all analyses related an individual’s origin in this article. The second, “citizenship,” is not referred to in this article and was filled out with much less completeness in the overall dataset. See Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler, The Caliphate’s Global Workforce for a more in-depth discussion of this issue.

[d] For purposes of this article, Western countries include Australia, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

[e] It is not immediately clear why the personnel records of Syrians are included among this particular tranche of what appears to be the Islamic State’s foreign fighter files. Perhaps these were Syrians who were displaced when the opportunity to return and join the group arose, or perhaps they had to exit one location in Syrian and re-enter in another.

[f] Because there is no information on the specific time of day that an individual was checked into the specific border crossing point, it is impossible to say if the children traveled as part of one group or whether they were part of different groups that arrived on the same day. Nevertheless, this data offers a possible look at child group travel habits.

[g] The (4) indicates that two or more children from Turkey arrived at the border on four separate occasions.

[h] The eight countries are as follows: China, France, Indonesia, Kosovo, Lebanon, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Citations

[1] Mia Bloom, “Cubs of the Caliphate: the Children of ISIS,” Foreign Affairs, July 21, 2015; Agathe Christien, “The Representation of Youth in the Islamic State’s Propaganda Magazine Dabiq,” Journal of Terrorism Research 7:3 (2016); Mia Bloom, John Horgan, and Charlie Winter, “Depictions of Children and Youth in the Islamic State’s Martyrdom Propaganda, 2015-2016,” CTC Sentinel 9:2 (2016); John G. Horgan, Max Taylor, Mia Bloom, and Charlie Winter, “From Cubs to Lions: A Six Stage Model of Child Socialization into the Islamic State,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40:7 (2017); “The Children in Daesh: ‘Future Flag Bearers’ of the ‘Caliphate,’” The Carter Center, 2017; The Children of ISIS: The Indoctrination of Minors in ISIS-held Territory (The Hague: National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism & General Intelligence and Security Service, 2017); Anthony Faiola and Souad Mekhennet, “What’s Happening to Our Children,” Washington Post, February 11, 2017; Robin Simcox, “The Islamic State’s Western Teenage Plotters,” CTC Sentinel 10:2 (2017); Colleen McCue, Joseph T. Massengill, Dorothy Milbrandt, John Gaughan, and Meghan Cumpston, “The Islamic State Long Game: A Tripartite Analysis of Youth Radicalization and Indoctrination,” CTC Sentinel 10:8 (2017).

[2] There are numerous books, journal articles, and government reports on this broader subject. For a few examples, see David M. Rosen, Armies of the Young: Child Soldiers in War and Terrorism (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005); Michael Wessells, Child Soldiers: From Violence to Protection (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006); and Alcinda Honwana, Child Soldiers in Africa (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

[3] “’Maybe We Live and Maybe We Die:’ Recruitment and Use of Children by Armed Groups in Syria,” Human Rights Watch, 2014; “Iraq: Militias Recruiting Children,” Human Rights Watch, 2016.

[4] Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler, The Caliphate’s Global Workforce: An Inside Look at the Islamic State’s Foreign Fighter Paper Trail (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2016).

[5] Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler, The Caliphate’s Global Workforce.

[6] Ibid.

[7] The entire breakdown of categories and coding choices is more fully described in the CTC’s report that introduced this dataset. See Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler, The Caliphate’s Global Workforce.

[8] Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler, Then and Now: Comparing the Flow of Foreign Fighters to AQI and the Islamic State (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2016).

Skip to content

Skip to content