Abstract: The complex war in Yemen and the ensuing collapse of a unified Yemeni government has provided al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) with opportunities to develop and test new strategies and tactics. While AQAP has been weakened by Emirati-led efforts in southern Yemen and recent U.S. strikes, it remains a formidable foe whose more subtle approach to insurgent warfare will pay dividends if there is a failure to restore predictable levels of security, sound governance, and lawful policing in the country.

Three years of war in Yemen have laid waste to the country’s infrastructure, killed at least 10,000 people, impoverished millions, and empowered insurgent groups like al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).1 The war, or more accurately wars, in Yemen are layered and complex with a growing number of factions, all with their attendant militias. Before the launch of “Operation Decisive Storm” by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and their allies in March 2015, Yemen was already a country riven with divisions.2 The internationally recognized government—in exile in Saudi Arabia since March 2015—of President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi exercised little control over Yemen. This was made clear when Yemen’s Zaidi Shi`a Houthi rebels seized the capital of Sana’a in September 2014 with the acquiescence of parts of the Yemeni Army.3 In the south, separatist movements calling for the recreation of an independent south Yemen have gained influence and power.4 The increase in factionalism and the hollowing out of an already weak national government has provided AQAP with an abundance of new opportunities to grow its organization and its influence. Opportunities that it has, over the last three years, exploited with notable success.

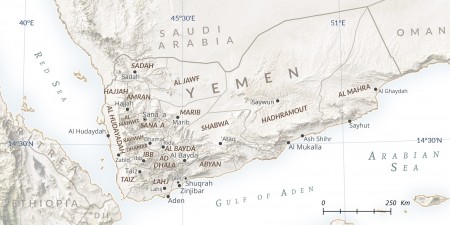

In April 2016, Yemeni troops—nominally allied with the Hadi government—backed by Emirati units retook the port city of Mukalla, which AQAP had held and governed for the previous year. Despite initial claims by the Saudi and Emirati coalition, the retaking of Mukalla was largely bloodless.5 AQAP chose a strategic retreat rather than to fight a superior force. As it has done in the past, AQAP sought and found shelter in Yemen’s vast hinterlands.6 Since retaking Mukalla, Emirati-backed forces such as the Hadrami Elite Force and its Security Belt Forces have used Mukalla as a central base for operations aimed at degrading AQAP.7 This ground war is being aided by the United States, namely through the use of UAVs that have successfully targeted a number of AQAP’s leaders.8 While there is some evidence that AQAP has been weakened by the ground campaign and the targeting of its operatives by UAVs, as it has demonstrated in the past, it is resilient, adaptive, and—most critically—expert at exploiting local and even national grievances.

AQAP is not the organization it was three or even two years ago. Just like most of Yemen’s political, social, and insurgent groups, it has been changed by the country’s multifaceted conflict. AQAP’s focus has shifted from the “far enemy”—though, this is not to say it does not continue to pose a threat to the West—to an array of “near enemies.”9 Its concerns, both political and martial, are local and national rather than international. Its de-prioritization of ideology reflects this shift. In many respects, AQAP has adopted and is guided by a more subtle and indigenized strategy with two primary aims: organizational survival and long-term growth. To achieve these aims, it remains intent on building alliances where it can by leveraging its fighting capabilities and by exploiting local and national grievances.10

Emirati-led efforts to combat AQAP in southern Yemen—largely limited to the governorates of the Hadramawt and Shabwa—could succeed where others have failed, or they could result in an abundance of new opportunities for AQAP to exploit. The Emirati-led effort to combat AQAP is another test for counterinsurgency warfare. While the Emiratis and the security forces that they are backing are making gains against AQAP in some parts of southern Yemen, these could be compromised by missteps that allow AQAP to apply the lessons that it has learned over the last three years.

Overcoming the Friction of Factions

The idea of friction in war was first introduced by Carl von Clausewitz in his book, On War. Clausewitz describes friction as a force that arises from the many unpredictable variables that materialize during war that can lay waste to the best-planned campaigns and the most efficient military forces.11 It is friction that distinguishes real war from war on paper.12 There are few theaters of war that are as capable of generating as much friction as a war in Yemen. As is evidenced by Yemen’s history, the country, its people, and its terrain are not kind to outside powers.

In 25 BC, a Roman expeditionary force led by Aelius Gallus was forced to retreat from what is now the governorate of Marib. The Ottoman Turks tried to subdue Yemen twice and failed both times despite expending vast sums of blood and treasure on the effort. Most recently, from 1962 to 1967, Egypt, under President Nasser, intervened in what was then north Yemen on the side of Republican forces who were fighting the Royalist supporters of Imam Muhammad al-Badr. Despite deploying more than 70,000 soldiers who enjoyed extensive air support, the Egyptian campaign in north Yemen failed.13 The Egyptians lost at least 10,000 soldiers.14 Their rivals, the Royalists, were armed with light weapons and had no air support. However, they leveraged Yemen’s rugged terrain, superior human intelligence, and, most critically, the factionalism that predominated in much of Yemen. Egyptian officers often complained about their “allies” who fought with them during the day and against them at night. These shifting alliances were reflective of the pragmatic and often quite democratic nature of the plurality of tribal relationships, structures, and allegiances that predominate in much of Yemen.

A counterinsurgent war in Yemen—which is what the Egyptians were fighting from 1962 to 1967—is replete with challenges for counterinsurgent forces and abounds with opportunities for the insurgent. This was the case before the collapse of the central Yemeni state and fragmentation of the Yemeni Army in 2014. Now that the country has largely been divided into a multiplicity of fiefdoms governed to varying degrees by numerous factions and militias, the challenges for conducting counterinsurgent warfare are even more pronounced.

Chief among these challenges is the factionalism that predominates across almost all of Yemen. In the south, where Emirati-backed forces are primarily conducting their campaign, there are multiple insurgencies underway. Various southern separatist groups are fighting to recreate an independent south Yemen, salafi militias are fighting to advance their own conservative religious agendas, displaced elites are fighting to retain and/or recover their power and influence, and both AQAP and, to a far lesser degree, the Islamic State are active across southern Yemen.15 These factions and their competing agendas produce high levels of Clausewitzian friction for the Emiratis and the security forces that they are supporting.

To combat factionalism, the Emiratis have tried to forge three security forces: the Security Belt Forces (also referred to as al-Hizam Brigades) largely deployed in southwest Yemen; the Hadrami Elite Forces deployed in the governorate of the Hadramawt; and the Shabwani Elite Forces deployed to southern Shabwa.16 a The three forces are primarily composed of Yemeni soldiers drawn from the southern governorates. These soldiers often have Emirati and foreign advisors. In the case of the Hadrami Elite Forces, the men are almost all from the Hadramawt, the rationale being that this incorporation of men drawn from the areas they will be deployed to will enhance the forces’ HUMINT capability while at the same time ensure some local support.17 The leadership of the three forces is largely drawn from tribal elites, some of whom formerly served as officers in the Yemeni Army, and ranking members of al-Hirak (the Southern Movement).18

The mission of the Emirati-backed forces—at least in theory—is twofold: first, restore a measure of security in those cities under their control, namely Aden and Mukalla, and the areas around them. Second, plan and launch security sweeps and clearing operations aimed at combating AQAP and what is left of the Islamic State. By using Mukalla in particular as a key staging point, the sweeps and clearing operations are designed to gradually widen the area controlled by the Emirati-backed forces.19 Following the ink spot theory, Mukalla and Aden will be held and secured as the security forces move into and clear the surrounding areas—many of which have been dominated by AQAP for the last three years.20 Due to the topography north of Mukalla—which is riven with deep wadis, box canyons, caves, and mountains—the ink spot looks more like an ink blot as security forces struggle to clear and hold broken terrain that is ideal for ambushes and raids. Hadrami Elite Forces have repeatedly been targeted in the southern reaches of the Hadramawt.21 There, the roads are few and almost always overlooked by high ground. AQAP has engaged in numerous hit-and-run attacks on the elite forces.22

Despite the treacherous terrain, the Hadrami Elite Forces have made some progress in clearing AQAP from the southern half of Wadi Huwayrah, Wadi Hajr, and the areas surrounding Ash Shihr.23 However, these gains are frequently reversed due to poor coordination between individual units within the security forces, which—as has often been the case with the Yemeni Army—do not adhere to chains of command. This lack of coordination is especially pronounced between the largely independent Security Belt Forces, Shabwani Elite Forces, and the Hadrami Elite Forces. The three forces do not have a unified chain of command and their commanders are often at cross-purposes.24

While the Emirati effort in southern Yemen is currently benefiting from the surge in southern nationalism, this nationalism is itself factional and subject to intense internal fighting. In the Hadramawt, groups calling for the independence of the governorate—which has a history of self-governance—have been active for years.25 Many who serve within the Hadrami Elite Forces are more dedicated to an independent Hadramawt than to other iterations of an independent south Yemen. Those who serve in the Security Belt Forces differ from those serving—especially at the command level—in the Hadrami Elite Forces in that most either support or are fighting for a wholly independent and unified south Yemen along the lines of the former People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY). In addition to groups that are either advocating or fighting for different visions of an independent south Yemen, there are elites who have been displaced by those who have been more successful at cultivating their relationship with the United Arab Emirates. They, too, will fight to recover what they feel they have lost in terms of influence, wealth, and power.26

There is a lot at stake in south Yemen. It is home to most of the country’s natural resources, and its most important oil handling facilities are located there. The creation of a new country or, at a minimum, new autonomous regions such as the Hadramawt is possible. Such high stakes all militate against the formation of cohesive security forces capable of engaging in the kind of sustained operations that counterinsurgency warfare demands. Adding to what is a long list of circumstances that will produce high-levels of friction is AQAP’s subtle approach to achieving its aims.

A More Subtle Foe

AQAP is intently focused on fighting what it views as a long war for the hearts and minds of the people it seeks to govern. As with any organization, there are those who believe the rhetoric produced by the leadership and those who—usually the leadership itself—recognize the rhetoric as an expedient reference point—possibly another political tool—rather than as a binding ideology. While AQAP’s leadership and media wing continue to produce (though media releases have decreased) the kind of extremist religious propaganda that jihadi groups have become known for, this is not necessarily reflective of the strategy and tactics employed by AQAP on the ground. This has been the case for much of the last three years.

AQAP’s April 2015 takeover of Mukalla was a watershed moment for the group. The takeover, which was largely bloodless, allowed them to seize large amounts of cash, weapons, and materiel, but most importantly, it provided the leadership with an opportunity to try out new strategies and tactics.27 The last time AQAP held and attempted to govern a significant swath of territory was in 2011-2012 when it took over a large part of the governorate of Abyan in the wake of the uprising against Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh.28 AQAP learned a great deal from its failures in 2011-2012. Namely, it learned that its radical interpretation of sharia is not acceptable to a majority of Yemenis. It also learned that the utilization of a punishment strategy is not suitable for a country where many people identify with various tribes that are often well-armed. In 2011-2012, AQAP attempted and failed to impose its will on those it wanted to govern by force.29 It did not make this mistake in Mukalla in 2015.

Rather than relying on a punishment strategy when it took over Mukalla in April 2015, AQAP adopted a far more subtle and pragmatic strategy that combined ruling covertly through proxies with a continued focus on guerrilla and hybrid operations against its rivals outside the city. During its yearlong occupation of Mukalla, AQAP largely refrained from imposing its interpretation of sharia. Instead, it allied itself with select local elites and focused much of its effort, with some success, on improving living conditions in the city and providing predictable levels of security.30 AQAP’s efforts to improve living conditions, operate charities, and provide security during its occupation of Mukalla are now being contrasted with current Emirati-led efforts to govern the city. The result, according to some, is that AQAP did a better job.31 While this is to a large degree subjective, it is reflective of a widespread sentiment.32 And it is a view that will be used by AQAP’s leadership to critique the new government in Mukalla.

AQAP’s strategic retreat from Mukalla in April 2016 also reflects the fact that the leadership learned many lessons in 2011-2012. The leadership had clearly planned and prepared for the retreat. They had no intention of taking on a superior force aided by air support.33 This was a mistake they made in trying to defend and hold parts of Abyan in 2012. AQAP’s leadership recognized that preserving what they viewed as good relations with the people of Mukalla and the alliances they made with some members of the Hadrami elite was critical to their ability to continue fighting.

Since its strategic retreat from Mukalla, AQAP has continued to pursue its more subtle strategy and has successfully enmeshed its operatives—both covertly and overtly—within many of the militias, both salafi and tribal, that are fighting the Houthis, their allies, and in some cases Emirati-backed forces.34 AQAP remains one of the best organized and motivated insurgent forces in Yemen, and this has allowed it to build relationships with numerous militias.35 Most of these relationships will not abide and are merely based on the fact that AQAP and the militias share a common enemy, whether that be the Houthis or the Emirati-backed forces.36 For AQAP, the fact that the relationships and alliances are only nominal is of little consequence. What is important is that enmeshment within anti-Houthi forces allows for concealment, a chance to demonstrate their superior fighting abilities, and, in some cases, income for AQAP. In some areas, just as it has in the past, AQAP acts as a mercenary force for elites whose interests happen to align with its own, even if this alignment is only temporary.37

AQAP’s focus on enmeshment, covert governance where possible, and jettisoning of a punishment strategy will make it more difficult to combat. This, combined with the fact that Yemen is mired in multiple wars being fought by multiple insurgent groups, means that discerning who is and who is not a member or ally of AQAP will be all the more difficult. Yet, AQAP’s adoption of a more subtle strategy makes discernment, security, and good governance all the more important.

Challenges and Opportunities

While the Emirati-led effort to combat AQAP is heavily reliant on indigenous fighters, the country’s efforts have led to the perception that the UAE is a colonizing force. The growing influence of the UAE and those elites that it has either chosen to empower or that have sided with it are already fueling debate and rhetoric on all sides of the conflict. While the UAE has been careful to minimize the outward signs of the presence of its forces and advisors in southern Yemen, there is the growing sense among many Yemenis that the Emiratis are in southern Yemen to stay.38 Stories about the UAE’s occupation of the Yemeni island of Socotra and its plans to build a military base there have provoked angry responses from many sectors of Yemeni society.39 AQAP will be quick to take advantage of and foster the perception that the UAE is intent on occupying Yemen for its own purposes. The veracity of the claim matters little. While Muslim and Arab, the Emiratis, which also employ many foreigners as advisers and mercenaries, are foreigners, and few actions empower an insurgency like foreign occupation—perceived or otherwise.40

Concurrent with what could be a growing perception by many of the UAE as an occupying force in Yemen is the problematic tactics used by some of the UAE-backed security forces. These security forces are conducting sweeps that often result in the detention of large numbers of men with no or only a minimal relationship with AQAP.41 AQAP controlled Mukalla and many of the surrounding areas for more than a year. Many residents in these areas were forced to interact with AQAP on some level. At the same time, AQAP recruited many men as foot soldiers. For the most part, these recruits did not share the group’s ideology or aims. Most joined to collect salaries, receive food aid, and, in some cases, protect their families from retribution by AQAP. Still others—a minority—joined to help AQAP fight the Islamic State whose ideology and tactics are viewed by most as far more virulent and alien to Yemen.42 There is also the very real danger that, as happened in Afghanistan in the early years of the U.S. war there, informants label rivals as AQAP for security forces as a way of settling scores, making money, removing rivals, and enhancing their own power.43 Given the prevalence of factions and competing agendas in Yemen as well the informal nature of many of the security units, the danger of this is especially high.

In addition to the possibility that many of those rounded up in the sweeps are not members of AQAP, there are credible allegations of security forces abusing detainees. In June 2017, Human Rights Watch released a report that cited numerous cases of torture, abuse, unlawful detention, and disappearances purportedly carried out by Security Belt and Hadrami Elite forces.44 Additional reports have appeared in the international media about Emirati-run detention centers where Yemenis held for alleged ties to AQAP have been tortured, including reports that some detainees were roasted on a spit.45 Reports of these kinds of actions—regardless of whether or not they are true—will be seized upon by AQAP. It is worth remembering that the first issue of AQAP’s English language publication, Inspire, featured an article written by Usama bin Ladin in which he referenced the abuses committed at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq as evidence of the United States’ malicious intent.46 Similarly, the alleged abuses committed at Emirati-run detention facilities will fuel resentment that AQAP will exploit.

AQAP and other insurgent groups operating in Yemen will seize on any and all missteps by the Emirati-backed forces and the Emiratis themselves. Having largely abandoned the punishment strategy in favor of one that is better adapted to the socio-cultural terrain it operates in, AQAP’s leadership likely understands the benefit of drawing the UAE and its forces into a war where they employ a punishment strategy of their own. Such a strategy, especially when employed by a foreign power, will alienate the populace and in turn drive recruitment for AQAP and other groups.

Conclusion

In his article, “Evolution of a Revolt,” T.E. Lawrence, speaking about the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire in 1916-1918, argued that insurgents would be victorious if they understood and applied certain “algebraical factors.” These factors included mobility, force security, time, and respect for the populace.47 AQAP has adopted and is, to varying degrees, employing Lawrence’s algebra for a successful insurgency. It has retained its mobility. Its enmeshment within anti-Houthi forces is—to some extent—contributing to force security and drawing its enemies into a punishment strategy. AQAP is also patient and committed to the long war and is intent on working within the Yemeni socio-cultural context in a way that allows subjects to remain, at a minimum, neutral. This is not to say that AQAP will be victorious. However, its ability to adapt, learn, and employ strategies that are increasingly well adapted to the areas in which it operates, does mean that it will survive and will, given the opportunity, go on the offensive yet again.

As Colonel Gian Gentile argues in his book Wrong Turn: America’s Deadly Embrace of Counterinsurgency, “hearts-and-minds counterinsurgency carried out by an occupying power in a foreign land doesn’t work, unless it is a multigenerational effort.”48 While the Emiratis do not seem intent on occupation and its counterinsurgency efforts are heavily reliant on Yemenis, it is a foreign-led effort in a country that has, throughout its history, violently and successfully resisted incursions by outside powers. While it is extremely unlikely that AQAP could ever take over southern Yemen, short of the kind of highly problematic, multigenerational effort described by Gentile, it will remain a persistent and potent threat over the long term.

The short-term success of Emirati-led efforts in Yemen are predicated on their ability to compete with AQAP in regard to the levels of security and efficacy of governance that they can provide. This success is also predicated on the Emiratis’ ability to avoid being seen as occupiers acting through militias motivated by their own factional interests. A failure to restore governance, predictable levels of security, and “clean” policing will be exploited by an enemy that—while weakened—remains capable, resilient, and perhaps most importantly, patient. CTC

Michael Horton is a senior analyst for Arabian affairs at The Jamestown Foundation where he specializes in Middle Eastern affairs with a particular focus on Yemen. He is a frequent contributor to Jane’s Intelligence Review and has written for numerous publications including Islamic Affairs Analyst, The Economist, The National Interest, and The Christian Science Monitor. He has completed numerous in-depth, field-based studies in Yemen and Somalia on topics ranging from prison radicalization to insurgent tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Substantive Notes

[a] The UAE is also in the early stages of training and arming a separate force, Mahri Elite Forces, in Yemen’s easternmost governorate, al-Mahrah. Eleonara Ardemagni, “Emiratis, Omanis, Saudis: the rising competition for Yemen’s al-Mahra,” London School of Economic and Political Science, Middle East Centre Blog, December 28, 2017.

Citations

[1] “ECHO Factsheet Yemen,” European Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, January 2018; Noah Browning, “Deep in Yemen war, Saudi fight against Iran falters,” Reuters, November 9, 2017.

[2] Ben Watson, “The War in Yemen and the Making of a Chaos State,” Atlantic, February 3, 2018.

[3] “How Yemen’s capital Sanaa was seized by Houthi Rebels,” BBC, September 27, 2014.

[4] “UAE-backed separatists launch ‘coup’ in southern Yemen,” Al Jazeera, January 28, 2018.

[5] “Yemen conflict: Troops retake Mukalla from al-Qaeda,” BBC, April 25, 2016.

[6] “Al Qaeda in Yemen confirms retreat from port city of Mukalla,” Reuters, April 30, 2016.

[8] Phil Stewart, “Small U.S. military team in Yemen to aid UAE push on al Qaeda,” Reuters, May 6, 2016; “US drone kills five al-Qaeda suspects in war-torn Yemen,” New Arab, October 8, 2017.

[10] Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “Foe Not Friend: Yemeni Tribes and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula,” Project on Middle East Democracy, February 2018; “Yemen’s al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base,” International Crisis Group, February 2, 2017.

[11] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Indexed Edition, Michael Eliot Howard, Peter Paret eds. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989).

[12] Ibid., p. 119.

[13] Jesse Ferris, Nasser’s Gamble: How Intervention in Yemen Caused the Six-Day War and the Decline of Egyptian Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012).

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Yemen’s Salafi warlord-armed by Riyadh branded a terrorist by Riyada,” Middle East Eye, October 27, 2017; Bruce Riedel, “Advancing separatists could restore South Yemen,” Al-Monitor, February 1, 2018.

[16] Eleonara Ardemagni, “UAE-Backed Militias Maximize Yemen’s Fragmentation,” Istituto Affari Internazionali, August 29, 2017; Aziz El Yaakoubi, “UAE builds up Yemen regional army but country fragments,” Reuters, May 3, 2017.

[17] Author interview, Yemen-based analyst, January 2018.

[18] Demolinari, “Commander Brig Gen Munir Abu Al-Yamamah raising the #SouthYemen flag during the military parade at Martyr Iyad bin Suhail camp in Bureiqa #Aden. #Yemen,” Twitter, January 20, 2018; Demolinari, “Brig Gen Munir Abu Al-Yamamah Al-Yafei of Security Belt 1st Support Brigade left #Aden for a visit to Abu Dhabi #UAE. #SouthYemen #Yemen,” Twitter, November 24, 2017.

[19] Author interview, Yemen-based analyst, January 2018.

[20] Andrew F. Krepinevich Jr., “How to Win in Iraq,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2005.

[21] “AQAP Photographs Rocket Strike on Hadrami Elite Forces’ Camp in Hadramawt,” SITE Intelligence Group, December 2, 2017. See Demolinari, “#AQAP claims attack on Hadrami Elite forces camp at Budha in Doan #Hadramout at 5:45am this morning. Six photos published of the attack. #Yemen,” Twitter, January 10, 2018.

[23] Author interview, Yemen-based journalist, January 2018.

[24] Author interview, Yemen-based analyst, January 2018.

[25] Michael Horton, “Yemen’s Hadramawt: A Divided Future?” Jamestown Foundation, May 20, 2011; Michael Horton, “The Growing Separatist Threat in Yemen’s Hadramawt Governorate,” Terrorism Monitor 8:40 (2010).

[28] “Al-Qaeda fighters seize Yemeni City,” Al Jazeera, May 29, 2011.

[29] Horton, “Fighting the Long War.”

[30] Ayisha Amr, “How al-Qaeda Rules in Yemen,” Foreign Affairs, October 28, 2015.

[32] Author interview, Yemen-based journalist/ analyst, January 2018.

[33] “Al Qaeda in Yemen confirms retreat from port city of Mukalla.”

[36] Al-Dawsari.

[37] Horton, “Guns for Hire;” Martin Jerrett and Mohammed al-Haddar, “Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula: From Global Insurgent to State Enforcer,” Hate Speech International Investigating Extremism, March 2017.

[38] Author interviews, Yemen-based journalists, January-February 2018.

[39] Paola Tamma, “Has the USE colonised Yemen’s Socotra island paradise?” New Arab, May 17, 2017.

[40] “The UAE is ‘employing’ Blackwater to run its army,” New Arab, July 8, 2017; Emily B. Hager and Mark Mazzetti, “Emirates Secretly Sends Colombian Mercenaries to Yemen Fight,” New York Times, November 25, 2015; “UAE Deploys Mercenaries in Yemen,” Economist Intelligence Unit, November 30, 2015; Elliott Balch, “Myth Busting: Robert Pape on ISIS, Suicide Terrorism, and US Foreign Policy,” Chicago Policy Review, May 5, 2015.

[41] Author interview, Yemen-based analyst, January 2018; author interview, Yemen-based journalist, December 2017.

[42] Author interview, Yemen-based analyst, December 2017.

[43] David Leigh and James Ball, “Guantánamo Bay files: Caught in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Guardian, April 24, 2011; Heidi Blake, Tim Ross, and Conrad Quilty Harper, “WikiLeaks: children among the innocent captured and sent to Guantanamo,” Telegraph, April 26, 2011; Anand Gopal, No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes (London: Picador, 2015).

[44] “Yemen: UAE Backs Abusive Local Forces,” Human Rights Watch, June 22, 2017.

[45] “Yemen: Urgent investigation needed into UAE torture network and possible US role,” Amnesty International, June 22, 2017; “Amnesty urges probe into report of UAE torture in Yemen,” Al Jazeera, June 22, 2017.

[46] Inspire, Al-Malahem Media, 2010.

[47] Thomas Edward Lawrence, “Evolution of a Revolt,” Army Quarterly 1:1 (1920).

[48] Colonel Gian Gentile, Wrong Turn: America’s Deadly Embrace of Counterinsurgency (New York: The New Press, 2013).

Skip to content

Skip to content